Abstract

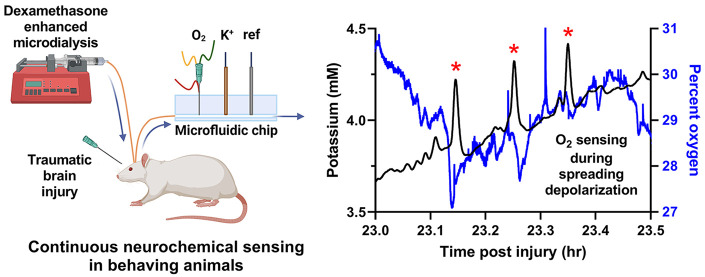

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major public health crisis in many regions of the world. Severe TBI may cause a primary brain lesion with a surrounding penumbra of tissue that is vulnerable to secondary injury. Secondary injury presents as progressive expansion of the lesion, possibly leading to severe disability, a persistent vegetive state, or death. Real time neuromonitoring to detect and monitor secondary injury is urgently needed. Dexamethasone-enhanced continuous online microdialysis (Dex-enhanced coMD) is an emerging paradigm for chronic neuromonitoring after brain injury. The present study employed Dex-enhanced coMD to monitor brain K+ and O2 during manually induced spreading depolarization in the cortex of anesthetized rats and after controlled cortical impact, a widely used rodent model of TBI, in behaving rats. Consistent with prior reports on glucose, O2 exhibited a variety of responses to spreading depolarization and a prolonged, essentially permanent decline in the days after controlled cortical impact. These findings confirm that Dex-enhanced coMD delivers valuable information regarding the impact of spreading depolarization and controlled cortical impact on O2 levels in the rat cortex.

Keywords: Microdialysis, dexamethasone, oxygen, spreading depolarization, traumatic brain injury, controlled cortical impact

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) due to vehicle and industrial accidents, sports injuries, military action, etc. is a major public health crisis.1,2 TBI may produce a primary brain lesion surrounded by a penumbra of tissue vulnerable to secondary injury.3−5 This creates an urgent need for technology to detect and monitor secondary injury. Prior studies affirm that neuromonitoring by intracranial microdialysis,2−7 which is approved for clinical use in several countries, is a foundation for such technology.

Several mechanisms have been implicated in secondary brain injury, including ischemia, elevated intracranial pressure, seizure, etc.8−12 Recently, however, spreading depolarization (SD) has become a central focus because SD is detected in approximately 60% of monitored TBI patients and because a correlation has been established between SD and patient outcome.13,14 SD is a pathological disturbance of homeostasis that spreads as a wave across the cortex (a “brain tsunami”15): the disruption of transmembrane ion gradients results in mass cellular depolarization.16,17 Following SD, the tissue consumes vast amounts of energy during the restoration of homeostasis: if the energy demand exceeds the supply, metabolic crisis leading to tissue death ensues.18 Thus, a goal of neuromonitoring is to detect metabolic crisis in real-time.

Microdialysis is a well-established tool for intracranial neurochemical monitoring.19−21 Dexamethasone-enhanced22−26 continuous online microdialysis27−31 (Dex-enhanced coMD) is an emerging paradigm for long-term neuromonitoring after brain injury.26,32,33 Retrodialysis with dexamethasone mitigates the foreign body response to probe insertion that otherwise degrades the functionality of microdialysis over time. The adoption of continuously operating sensors for analysis of the dialysate stream delivers the high temporal resolution necessary to monitor the chemical dynamics associated with SD.

The focus of the present study is the real-time monitoring of interstitial oxygen in the rat cortex with Dex-enhanced coMD. The availability of O2, alongside glucose, is critical to meeting the energy requirements for the restoration of homeostasis following SD. In acute experiments, we manually induced SD by a pin-prick to the cortical surface of anesthetized rats. In chronic experiments (defined here as 7 days following probe insertion), we monitored SD after controlled cortical impact (CCI), a widely used rodent model of TBI.34−36 The O2 results reported herein show similarities to the glucose data reported recently by Robbins et al.,32 in that SD induces a variety of O2 responses. Moreover, dialysate O2 levels exhibit a prolonged, essentially permanent, decline to very low concentrations in the days after CCI. Collectively, our findings support the idea that 7-day Dex-enhanced coMD offers valuable information regarding the impact of SD and CCI on O2 levels in injured brain tissue.

Results and Disucssion

Experimental Design

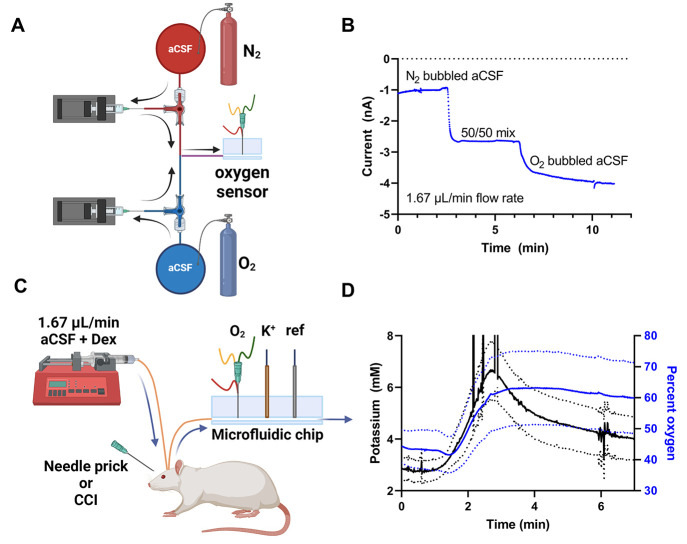

Figure 1 is a schematic of the Dex-enhanced coMD system for monitoring O2. The O2 sensors, 50 μm diameter Pt disk electrodes, were mounted in a 3D-printed electrochemical detector and calibrated prior to being connected to the microdialysis probes. We calibrated the O2 electrodes by connecting the electrochemical detector with fused silica tubing to a pair of pumps fitted with gastight syringes that delivered varying combinations of aCSF equilibrated with N2 or O2 gas (Figure 1A). Fused silica capillary tubing was selected for this application because it is impermeable to O2 and preserves the O2 concentration in the sample stream. Figure 1B shows an O2 calibration: we report O2 data as “percent O2”, defining aCSF equilibrated with N2 as 0% and aCSF equilibrated with O2 as 100%. The same pumps were used to calibrate the K+ μISE. Microdialysis probes were inserted into the rat cortex and perfused at 1.67 μL/min with air-equilibrated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing Dex (Figure 1C, see Methods for the details of Dex retrodialysis). The outlet of the microdialysis probe was connected via fused silica capillary tubing to a 3D printed electrochemical detector equipped for the amperometric detection of O2 and the potentiometric detection of K+. We induced SD either by means of a manual pin-prick to the brain surface (acute experiments) or by CCI (7-day chronic experiments).

Figure 1.

Schematics of the Dex-enhanced coMD system for O2. (A) Setup for O2 calibration. (B) Representative O2 calibration. (C) Setup for monitoring O2 and K+ in the rat cortex. (D) K+ (black, left axis) and O2 (blue, right axis) responses to probe insertion (solid lines are the mean, dotted lines show ±SEM).

Microdialysis Probe Insertion

We monitored the dialysate of n = 11 anesthetized rats during the insertion of microdialysis probes into the cortex (Figure 1D). Figure 1D shows the average (±SEM) of the dialysate K+ and O2 responses to probe insertion on a time axis corrected to account for the transit time of dialysate through the probe outlet line (determined for each probe individually). As reported before,26 insertion of a microdialysis probe induces a transient rise in K+ from the initial concentration of 2.7 mM in the aCSF present in the probe prior to insertion. Upon insertion, dialysate O2 levels rose from near 40%, corresponding to aCSF equilibrated with ambient air, to a maximum level in brain tissue near 60% and then slowly declined. However, dialysate O2 levels did not exhibit a transient response to the insertion.

Acute Measurements: Manually Evoked SD

Acute SD recordings were performed in n = 11 anesthetized rats. Starting 2 h after the completion of probe insertion, the brain surface was manually pricked with a hypodermic needle via a burr hole through the skull. Each rat was pricked 3 times with a 30 min interval between each prick. Of the 33 pricks administered, 19 evoked a K+ transient to indicate that SD occurred (Figure 2). Consistent with our prior report,26 some needle pricks failed to elicit a K+ transient (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information provides representative raw data from individual rats that responded to 3, 2, or 1 pin-prick): we assume that the prick did not evoke SD or that the evoked SD did not spread to the vicinity of the microdialysis probe.

Figure 2.

Mean of the K+ transients (black) evoked by needle pricks to the cortical surface and the corresponding mean of the O2 response (blue), grouped according to the classification of the O2 response: (A) O2 transient increases; (B) O2 transient decreases; (C) O2 null responses (t = 0 corresponds to the peak of the K+ transient.( D) The percent O2 changes between classifications are significantly different (* = p < 0.05, **** = p < 0.00005, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test).

During SD, dialysate O2 levels transiently increased, transiently decreased, or did not change (Figure 2). To objectively classify the O2 responses, we determined an O2 threshold of 3 times the standard deviation of the signal over the 2 min period just prior to the onset of the K+ transient. If the change in O2 at the peak time of the K+ transient exceeded this threshold, then the O2 response was classified as a transient; otherwise, it was classified as a null response. Accordingly, the 19 evoked SDs produced 7 O2 transient increases (Figure 2A), 7 O2 transient decreases (Figure 2B), and 5 O2 null responses (Figure 2C). The percent changes in O2 between response classifications were significantly different (Figure 2D).

The finding in Figure 2 that manually evoked SD produces a variety of O2 responses, including transient increases, transient decreases, and null responses, stands in slight contrast to the results of Varner et al.,26 who reported that manually evoked SDs produce transient decreases in dialysate glucose with only a few (15%) null responses: manually evoked SD did not cause transient increases in glucose. However, the outcome is different in the case CCI-evoked SD, as discussed further below.

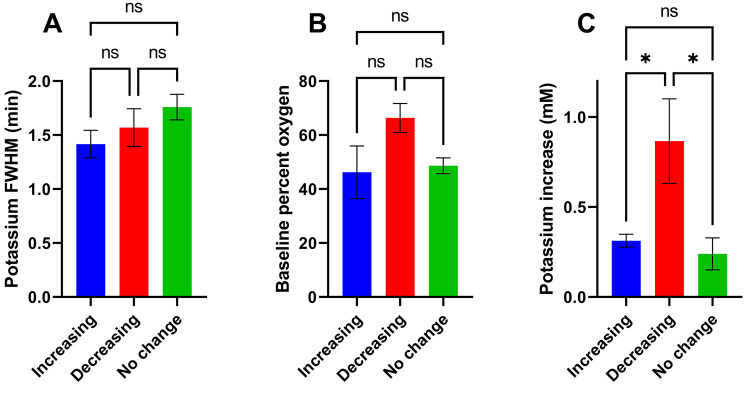

We quantitatively evaluated the responses in each classification (Figure 3). There are no significant differences between the durations of the K+ transients, quantified by their full width at half-maximum (Figure 3A). There are no significant differences between the baseline O2 levels prior to the onset of the K+ transient (Figure 3B), although baseline O2 trended higher prior to O2 transient decreases. There are, however, significant differences between the amplitudes of the K+ transients between classifications: the amplitudes of the K+ transients were significantly larger when accompanied by transient decreases in O2 (Figure 2B and Figure 3C). It is well established that tissue repolarization after SD demands large amounts of energy: we have previously reported that this energy demand drives a decrease in dialysate glucose26,28,30−33 and extend that finding here by documenting a concomitant transient decrease in dialysate O2. However, only the larger amplitude K+ transients are accompanied by transient decreases in dialysate O2.

Figure 3.

Mean ± SEM of three descriptive parameters of the manually evoked SD responses, according to the classification of the O2 response. (A) The full width at half-maximum of the K+ transient is not significantly different between classes. (B) The pre-SD O2 level is not significantly different between classes, although a trend toward increased pre-SD O2 is present in the case of the O2 transient decreases. (C) The amplitude of the K+ transient is significantly increased in the case of the O2 transient decreases (*p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test).

Together, Figures 2 and 3 suggest that SDs might produce a range of metabolic consequences in brain tissue. SDs with low-amplitude K+ responses are accompanied by no O2 response or an increase in O2 that is possibly due to the known hyperemic response to SD. On the other hand, when the K+ amplitude is large, the SD is accompanied by a transient decrease in O2, suggesting that such SDs create a metabolic crisis because the O2 demand exceeds the vascular supply. During this work, however, the largest K+ amplitudes were observed during the probe insertion response (>3 mM, Figure 2), but these responses were not accompanied by any apparent decrease in O2; thus, it appears that the metabolic consequences of probe insertion and a pin-prick are different.

The literature most often describes SD as an “all or nothing” mass depolarization event,16 wherein brain tissue either depolarizes or does not. The finding of variations in the amplitude of SD responses (Figures 2 and 3) is not in strict agreement with this “all or nothing” model. As discussed in the Supporting Information, variations in the amplitude of SD responses have also been observed in prior microdialysis studies from the Boutelle group (Figure S2).37 On the other hand, Marinesco and colleagues, who monitored brain glucose with parenchymal microbiosensors, observed a consistent, and deeper, decrease in glucose during SD, more consistent with the “all or nothing” model.38−40 We speculate that the size and geometry of the recording devices play a role in these contrasts. The microbiosensors, which have tips 100 μm in length and 40 μm in diameter, perform spatially localized measurements. This increases the chances that the entire tip senses the SD response. Microdialysis probes are considerably larger (herein, 4 mm in length and 280 μm in diameter) and perform spatially averaged measurements. This increases the chances that only a portion of the probe monitors the SD response, leading to variations in the response amplitude due to averaging.

Overall, the performance differences between microdialysis probes and implanted microsensors are well-known. Microsensors deliver high spatial and temporal resolution; however, they are less suitable for chronic measurements and are not approved for clinical use. Microdialysis probes deliver less spatial and temporal resolution but rather perform a spatially averaged measurement. On the other hand, they monitor over a larger region of tissue, which might increase the chances of detecting more SD events. Microdialysis is suitable for chronic measurements lasting several days and is approved for clinical use.

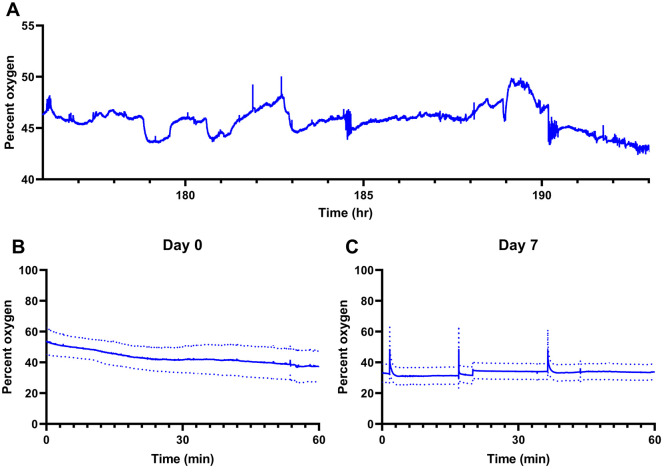

Chronic 7-Day Measurements: SD after CCI

A group of rats (n = 6) was anesthetized, received a CCI, and had a microdialysis probe inserted 3 mm anterior to the injury site. Five of these animals underwent 7 days of Dex-enhanced coMD with the apparatus depicted in Figure 1C. One animal died on the day following the CCI and probe insertion without exhibiting SD. One other rat exhibited no post-CCI SDs. The other 4 injured rats exhibited a total of 63 SDs, ranging from 3 to 26 per rat. After CCI, all 6 rats exhibited a long-term decline in dialysate O2 to near-zero levels. A group of control rats (n = 4) received a microdialysis probe but neither a CCI nor a sham craniotomy. These noninjured control rats exbited neither SD nor long-term changes in O2 or K+ over the 7 days following probe insertion. Figure 4A shows a representative O2 trace from a control animal on day 7 postinsertion. Dialyate O2 levels hover around 45% with fluctuations around 5% of unknown origin. Figure 4B and Figure 4C show mean O2 measured in 60 min time windows in the control rats on days 0 (the day of insertion) and 7, respectively, following probe insertion. The mean O2 levels were 38.0 ± 10.0 on day 0 and 33.8 ± 5.1 on day 7; these values are not significantly different.

Figure 4.

Dex-enhanced coMD monitoring of O2 in the cortex of control rats (no CCI injury) on days 0 and 7 following probe insertion. (A) Trace of O2 in dialysate from an individual rat on day 7. (B, C) Mean O2 from n = 4 rats on days 0 (B) and 7 (C) after probe insertion (mean ± SEM).

Figure 4 shows baseline O2 level near 40%, where 100% corresponds to aCSF equilibrated with O2 and 0% corresponds to aCSF equilibrated with nitrogen (see Figure 1). Thus, 40% O2 corresponds to ∼300 mmHg, which is about 10-fold higher than the usual value of PbtO2, 20–30 mmHg.14,41 Our study was not designed to investigate this discrepancy, but our use of Dex-retrodialysis to mitigate gliosis and vascular disruption at microdialysis probe tracks is a possible contributor. It is also the case that the microdialysis perfusion fluids used during this work were equilibrated with the ambient lab air; i.e., they contained a source of O2 that is not present when PbtO2 is measured with conventional electrochemical devices.

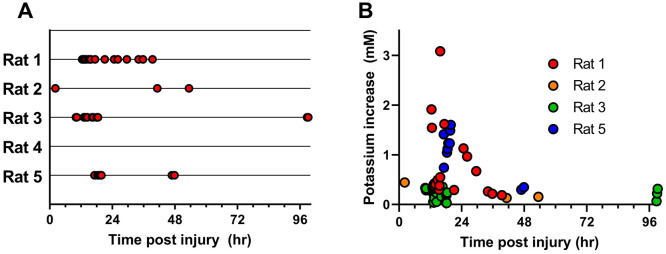

Figure 5A shows the temporal distribution of SD events in 5 injured rats. All SD events occurred within 5 days of CCI, with the majority (59 of 63) occurring within the first 48 h but only one during the first 8 h. Thus, 8–48 h after CCI appears to be a critical SD window. This SD window is in good agreement with existing literature. In juvenile rats, for example, oxidative metabolism of glucose begins to fail around 6 h following injury,42 possibly indicating that poor energy availability to the Na+/K+ pumps that maintain cell membrane ion gradients could potentially be the inciting event that triggers SD activity. Caspase-3 immunoreactivity reaches a maximum in cortex at 48 h after CCI,43 possibly indicating that apoptosis is beginning to clear the most distressed cells responsible for SD initiation and propagation.

Figure 5.

(A) Distribution of post-CCI SDs across the 5 rats monitored for 7 days. All SDs occurred within the first 5 days, with the majority occurring within the first 48 h. (B) Amplitude of the K+ transients observed over time. Numerous transients with amplitudes below 1 mM occurred during the first 5 days. Several transients with amplitudes between 1 and 3 mM occurred between 12 and 30 h post-CCI.

As with manually evoked SD (Figure 3), SD post-CCI exhibited K+ transients with a range of amplitudes. K+ transients with amplitudes below 1 mM occurred over the entire 5-day interval after CCI (Figure 5B). However, K+ transients with notably larger amplitudes of 1–3 mM occurred 12–30 h after CCI (Figure 5B). The data points in Figure 5B are color-coded to show points from individual rats. Some rats showed more variation in K+ amplitude than others, although the exact reason for this is unclear. As mentioned above, given the usual depiction of SD as an “all or nothing” event, the variation in K+ transient amplitudes noticed here may be reflective of the volume of tissue impacted by the SD rather than the local SD intensity. This, however, is potentially valuable information, indicating that larger volumes of brain tissue are more susceptible to SD within certain time windows after injury: it remains to be seen how these data from the CCI model would translate to the case of TBI in patients.

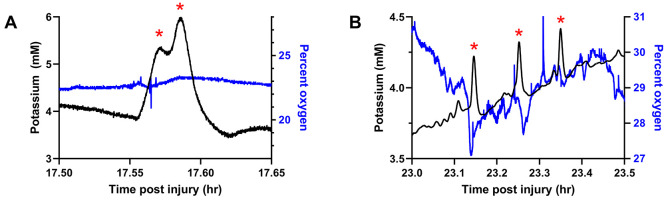

SD after CCI produced a range of O2 responses. However, due to the fact that many SDs appeared in quick succession (so-called SD clusters44,45) and because dialysate O2 sometimes exhibited baseline changes (discussed further in the next section), objectively classifying these O2 responses was not practical. Figure 6 shows some representative responses. Figure 6A shows an example of two SDs occurring in quick succession, with the second K+ transient beginning before the first one finished: such SD clusters have been previously associated with progressive declines in glucose.32 However, in this example, no O2 response was evident (null response). Figure 6B shows three K+ transients occurring about 6 min apart: the first two produced transient O2 decreases but the third did not. Unlike the case of manually evoked SD (Figure 3), SDs after CCI were accompanied by null O2 responses (Figure 6A) and transient O2 decreases (Figure 6B) but not transient O2 increases.

Figure 6.

Dialysate O2 (blue) and K+ levels (black) were monitored for 7 days post-CCI. (A) An example of two SDs in quick succession with a null O2 response. (B) An example of three SDs occurring at ∼6 min intervals: the first two SDs are accompanied by transient decreases in O2, but the third is not. Red asterisks mark SDs.

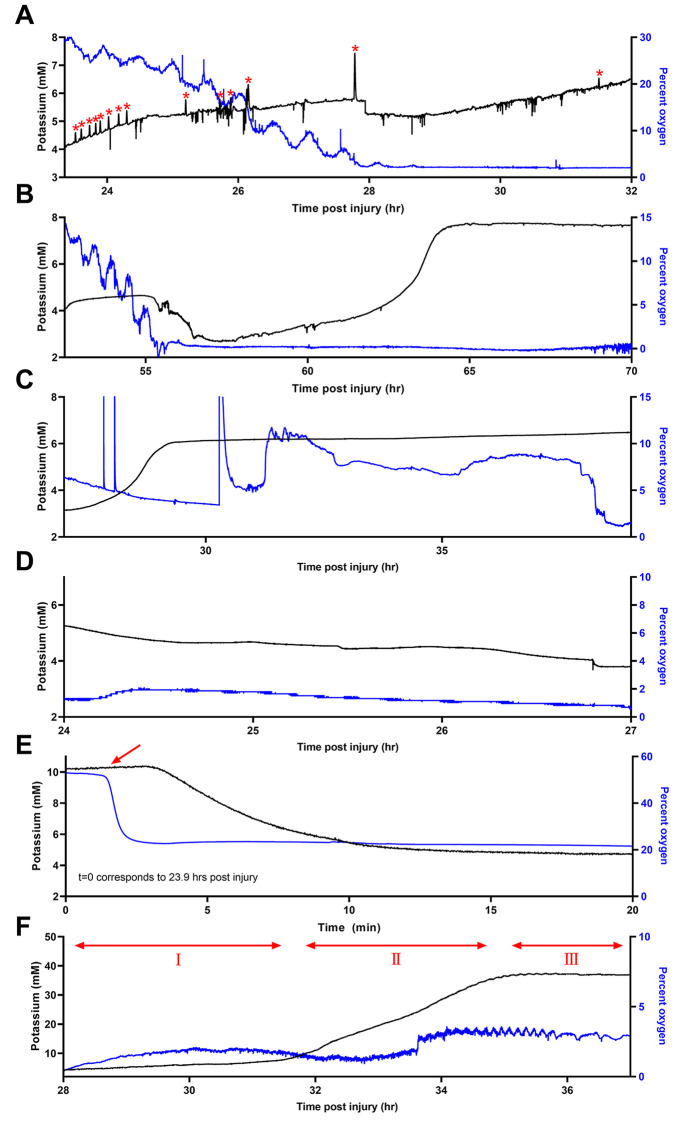

Chronic 7-Day Measurements: Long-Term Events after CCI

In all 6 rats monitored after CCI, baseline dialysate O2 fell to levels too low to measure. In 5 of these rats, baseline O2 levels began at near-normal levels and, at some point, progressively declined to near-zero (Figure 7A–E). Once this decline occurred, O2 did not recover. These experiments were terminated 7 days after CCI because by that time all injured rats had exhibited the decline. We emphasize that the decline in O2 was not due to any electrode failure: the electrochemical O2 signal remained too low to measure even with freshly refurbished and recalibrated electrodes. In some cases, as in Figure 7A–C, as O2 declined, K+ steadily increased and K+ transients indicating SD were observed in rat 1 after the O2 decline (Figure 7A); such observations confirm that the membrane of the microdialysis probe is continuing to exchange substances with the extracellular space. Furthermore, dialysate O2 levels fell below the O2 level from the air-equilibrated aCSF delivered to the probe inlet. The data in Figure 7E were recorded during and immediately following a calibration of the K+ electrode. As the last of the air-equilibrated calibration solution was replaced by brain dialysate in the first several minutes of Figure 7E, O2 dropped from above 50% to approximately 20%, indicating that O2 was being lost from the perfusion fluid to the surrounding tissue, i.e., that the surrounding tissue was extracting O2 from the probe, confirming that the microdialysis membrane retains its permeability to O2. Whether the O2 is consumed by nearby cells or is carried away by the circulatory system46 is unknown at this time. These observations confirm that the decline of dialysate O2 is not attributable to a loss in the permeability (i.e., blockage) of the dialysis membrane.

Figure 7.

All 6 rats that received a CCI exhibited near-zero dialysate O2 levels postinjury. Multiple post-CCI SDs (red asterisks) and associated O2 fluctuations were detected in 4 of these rats. Additionally, long-term declines in O2 and increases in K+ occurred post-CCI in (A) rat 1, (B) rat 2, and (C) rat 3. In two animals, monitoring did not capture the decline itself, but we observed the low O2 and elevated K+ levels in (D) rat 4 and (E) rat 5. In the first few minutes of (E), a calibration solution was replaced with brain dialysate (red arrow): the O2 level dropped, showing that the brain tissue surrounding the probe extracts O2 from the perfusion fluid. (F) In rat 6, which died on the day after CCI, recordings of O2 were persistently low, while K+ was near normal initially, rose slowly in region I, rose rapidly in region II, and then plateaued near 40 mM in region III and remained elevated until death occurred.

As mentioned above, one rat died on the day after CCI. Dialysate O2 in this individual was persistently low throughout the monitoring period (Figure 7F). Starting at 28 h post-CCI (region 1 of the plot), K+ levels began a persistent rise. In region II, K+ rose more rapidly. In region III, K+ levels plateaued near 40 mM, far higher than we have observed in any other case, and remained at that high level until death occurred.

The long-term declines in dialysate O2 reported here show a similarity to the long-term declines in glucose reported in our previous work.32 In several cases, we also observed in similar instances that dialysate K+ levels increased as dialysate glucose levels declined. Like the O2 declines reported here, the glucose declines were also essentially permanent: once glucose declined, it did not recover. As with the O2 declines reported here, there was no evidence that the glucose declines were associated with any loss in permeability of the microdialysis membrane.33

Conclusion

Our findings show that Dex-enhanced coMD offers the technical ability to monitor dialysate O2 levels both acutely and over the longer term (7 days) with a singly implanted microdialysis probe. Dex-enhanced coMD provided new information on how O2 levels respond to acute, manually evoked SD as well as SD after CCI. Dex-enhanced coMD also documents long-term changes in tissue O2, specifically a long-term and apparently permanent decline after CCI. We conclude that the decline is a marker of metabolic abnormality arising after CCI injury.

Microdialysis has been used to monitor brain potassium, sodium, glucose, lactate, glutamate, and more after TBI.27,30,47−50 Thus, microdialysis has the potentially significant ability to monitor both the ionic disruptions that indicate SD and additional small molecules that serve as markers for the metabolic impact of SD. However, a glial barrier forms at the probe track over a few days after implantation.22,24,25 This barrier interferes with long-term monitoring by degrading the performance of microdialysis.51 Dex retrodialysis resolves this issue by preventing gliosis, preserving blood flow, and preserving glia and neurons in the vicinity of the probe tracks for at least 10 days after probe implantation.26,33,52 This study is the first attempt to deploy Dex-enhanced brain microdialysis for O2 monitoring.

Our findings reveal that SD induces a variety of O2 responses, which is similar to our previous observations on glucose.26,32 However, SDs induced with pin-pricks did not induce transient increases in glucose. Only those SDs exhibiting large-amplitude K+ transients were accompanied by transient O2 decreases. The longer-term measurements after CCI revealed a slow decline in O2, sometimes coincident with a slow increase in K+. These observations bear a striking resemblance to those of glucose.32 Chronically elevated K+ may contribute to lesion expansion in secondary injury53 or may be indicative of blood– brain barrier disruption.54,55

Several prior studies suggest that cerebral glucose utilization shifts from oxidative phosphorylation to less efficient anaerobic pathways after brain injury.56,57 This less efficient glucose utilization is a potential explanation for the CCI glucose decline after CCI. The data in Figure 7 raise the possibility that an insufficiency in O2 availability might drive this shift.

While SDs are clinically monitored by electrocorticography,58,59 SDs cause many chemical changes that are valuable to measure, including the changes in O2 levels reported here.60,61 Reduced brain tissue oxygenation in TBI patients is associated with negative outcomes,13,62 and there is evidence that care directed by brain oxygenation may be associated with improved outcome when compared to conventional ICP or cerebral perfusion pressure-managed care.14 Brain O2 monitoring can be accomplished in many ways, including with fast scan cyclic voltammetry61,63 and clinically with implanted polyethylene-coated platinum electrodes.64,65 Oxygen measurements using microdialysis in human patients is currently not presently possible because the commercial probes approved for clinical use have polyurethane connecting lines, which are highly O2-permeable. However, our data emphasize the potential importance of coupling chemical sensing to SD monitoring in the injured brain.

Methods

Reagents and Solutions

Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) contained 142.0 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 2.0 mM NaH2PO4 (reagents from Sigma-Aldrich) and was adjusted to a pH of 7.4. 10 μM and 2 μM solutions of dexamethasone sodium phosphate (APP Fresenius Kabi USA LLC, Lake Zurich, IL) were prepared in aCSF. Microdialysis perfusion fluids were filtered with sterile Nalgene filters (PES, 0.2 μm pore size; Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) and equilibrated with ambient air before use. Solutions were prepared with ultrapure water (Nanopure; Barnstead, Dubuque, IA).

Microdialysis

Microdialysis probes were constructed in-house using 280 μm OD regenerated cellulose hollow fiber membranes cut to a length of 4 mm (18 kDa molecular weight cutoff; SpectraPor RC, Spectrum, Rancho Domingues, CA). Inlet and outlet lines were made from fused silica capillaries (75 μm ID, 150 μm OD; Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ). Probes were flushed with and soaked in 70% ethanol, then flushed with 10 μM dexamethasone (Dex) in aCSF prior to insertion into the rat brain. Probes were inserted into the brain using a carrier arm of a Kopf stereotaxic frame: the manual insertion procedure lasted approximately 4 min. The probes were perfused with air-equilibrated fluid by means of gastight syringes driven by a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) at a flow rate of 1.67 μL/min. The probes were perfused with 10 μM Dex for the first 24 h, then with 2 μM DEX for 4 days, and then without Dex for the remainder of the experiment.

Acute Surgical Procedures

Animal procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g; Charles River, Raleigh, NC) were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 2.5% maintenance by volume O2) and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Rats in the acute group (n = 11) remained under anesthesia for the entire experiment. The microdialysis probe was inserted into the cortex at the following coordinates: 4.2 mm posterior to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to midline, and 4 mm below dura at a 51° angle to the vertical plane; all measurements were made using flat skull. With this insertion procedure, the entire 4 mm active portion of the probe was placed in the cortex. A second hole was drilled through the skull 4.5 mm anterior to the probe on the ipsilateral side. After 2 h, an 18 G hypodermic needle was used to manually prick the surface of the cortex through the second hole. Three pin pricks were performed per animal, with a 30 min waiting period in between.

Chronic Surgical Procedures

For animals monitored for 7 days, a Leica Impact One (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) was used to create a model of mild to moderate TBI. A craniotomy was performed on n = 6 rats posterior to bregma on the right hemisphere, and the exposed dura was struck at a velocity to 4.00 m/s, with a 100 ms dwell time to a depth of 2.2 mm. The probe was then inserted 3.0 mm anterior to the craniotomy, again at a 51° angle to ensure the entire probe was placed in the cortex. The probe was secured with bone screws and acrylic cement, and the incision was closed with sterile sutures. Probes were also inserted into the cortex of control rats (n = 4); control rats did not receive a CCI injury. These rats were housed in a Raturn microdialysis bowl (MD-1404, BASI, West Lafayette, IN) for the 7 days of microdialysis.

Oxygen and Potassium Monitoring

The outlet of the probe was connected to a 3D printed microfluidic chip; the design is described in detail elsewhere.30 Electrodes for detecting O2 and K+ were inserted into the flow stream of the chip (200 μm diameter) using 3D printed holders that screw into place without tools. The O2 sensor was a needle-style electrode fabricated by threading 50 μm diameter platinum and silver wires (Goodfellow, Huntingdon, U.K.) through a 27 G needle and sealing them in place with Spurr low-viscosity epoxy (Sigma-Aldrich). The stainless-steel needle body was used as the counter electrode. K+ μISEs were constructed by casting a potassium-selective membrane (2 mg of potassium ionophore, 0.2 mg of potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate, 150.0 mg of bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate, and 66 mg of poly(vinyl chloride) dissolved in 1 mL of tetrahydrofuran; reagents from Sigma-Aldrich) into a fused silica capillary (Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ). The electrode was backfilled with aCSF, and an Ag/AgCl internal reference electrode was inserted (50 μm diameter; Goodfellow). An additional needle-style Ag/AgCl external reference for the potassium electrode was also inserted into the microfluidic chip. All data were time corrected to account for the transit time between the electrodes in the microfluidic chip.

Data Acquisition, Electrode Calibration, and Analysis

In the acute needle prick experiments, K+ data were collected using homemade printed circuit boards courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh Electronics Shop connected to a PowerLab 2/26 data acquisition system using LabChart 8 software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO). O2 data were acquired using a CHI 1205C potentiostat (CHInstruments, Austin, TX) by holding the Pt working electrode at −0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl. During chronic experiments, an additional custom potentiostat was constructed by the University of Pittsburgh Electronics Shop connected to a second channel of the PowerLab 2/26. Oxygen was reduced at the Pt working electrode by holding the potential at −0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl. Calibration was performed using a set of LabSmith SPS-01 syringe pumps fitted with gastight syringes and 3-port selector valves (LabSmith, Inc., Livermore, CA). All connections were made with fused silica tubing and gastight connectors. Data analysis was conducted using MATLAB (Mathworks Inc.), and statistical analysis was done in GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01NS102725 and R21NS109875).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- CCI

controlled cortical impact

- SD

spreading depolarization

- Dex

dexamethasone

- coMD

continuous online microdialysis

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- μISE

microion-selective electrode

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00703.

Figure S1 showing data from study of SDs and Figure S2 showing reanalysis of data (PDF)

Author Contributions

E.M.R. is the sole first author. E.M.R. and A.S.J.-G. collected data. All authors participated in the design of the study, evaluation and interpretation of the results, and preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of the ACS Chemical Neuroscience special issue “Monitoring Molecules in Neuroscience 2023”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Schuchat A.; Director A.; Griffin P. M.; Rasmussen S. A.; Leahy M. A.; Martinroe J. C.; Spriggs S. R.; Yang T.; Doan Q. M.; King P. H.; Starr T. M.; Yang M.; Jones T. F.; Boulton M. L.; Caine V. A.; Daniel K. L.; Fielding J. E.; Fleming D. W.; Halperin W. E.; Holmes K. K.; Ikeda R.; Khabbaz R. F.; Meadows P.; Mullen J.; Niederdeppe J.; Quinlisk P.; Remington P. L.; Roig C.; Roper W. L.; Schaffner W. Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths-United States, 2007 and 2013. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6609a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U.; Rostami E. Microdialysis in Neurointensive Care. Curr. Pharm. Des 2004, 10 (18), 2145–2152. 10.2174/1381612043384105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmy A.; Carpenter K. L. H.; Menon D. K.; Pickard J. D.; Hutchinson P. J. A. The Cytokine Response to Human Traumatic Brain Injury: Temporal Profiles and Evidence for Cerebral Parenchymal Production. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2011, 31 (2), 658–670. 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Barcena J.; Ibáñez J.; Brell M.; Crespí C.; Frontera G.; Llompart-Pou J. A.; Homar J.; Abadal J. M. Lack of Correlation among Intracerebral Cytokines, Intracranial Pressure, and Brain Tissue Oxygenation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Diffuse Lesions. Crit Care Med. 2011, 39 (3), 533–540. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318205c7a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelin E. P.; Carpenter K. L. H.; Hutchinson P. J.; Helmy A. Microdialysis Monitoring in Clinical Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Role in Neuroprotective Drug Development. AAPS J. 2017, 19 (2), 367–376. 10.1208/s12248-016-0027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P. M.; McArthur D.; O’Phelan K.; Glenn T.; Etchepare M.; Kelly D.; Bergsneider M.; Martin N. A.; Hovda D. A. Persistently Low Extracellular Glucose Correlates with Poor Outcome 6 Months after Human Traumatic Brain Injury despite a Lack of Increased Lactate: A Microdialysis Study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2003, 23 (7), 865–877. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000076701.45782.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinzman J. M.; Wilson J. A.; Mazzeo A. T.; Bullock M. R.; Hartings J. A. Excitotoxicity and Metabolic Crisis Are Associated with Spreading Depolarizations in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Patients. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33 (19), 1775–1783. 10.1089/neu.2015.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock T.; Morganti-Kossmann M. C. The Role of Markers of Inflammation in Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 18. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz J.; Sullivan P. G.; Hovda D. A.; Wieloch T.; McIntosh T. K. Mitochondrial Damage and Dysfunction in Traumatic Brain Injury. Mitochondrion 2004, 4, 705–713. 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posti J. P.; Dickens A. M.; Orešič M.; Hyötyläinen T.; Tenovuo O. Metabolomics Profiling As a Diagnostic Tool in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 1–8. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer D. R.; Fujii T.; Ohiorhenuan I.; Liu C. Y. Cortical Spreading Depolarization: Pathophysiology, Implications, and Future Directions. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2016, 24 (2016), 22–27. 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer D. R.; Fujii T.; Ohiorhenuan I.; Liu C. Y. Interplay between Cortical Spreading Depolarization and Seizures. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2017, 95 (1), 1–5. 10.1159/000452841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn T. C.; Kelly D. F.; Boscardin W. J.; McArthur D. L.; Vespa P.; Oertel M.; Hovda D. A.; Bergsneider M.; Hillered L.; Martin N. A. Energy Dysfunction as a Predictor of Outcome after Moderate or Severe Head Injury: Indices of Oxygen, Glucose, and Lactate Metabolism. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2003, 23 (10), 1239–1250. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000089833.23606.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo D. O.; Shutter L. A.; Moore C.; Temkin N. R.; Puccio A. M.; Madden C. J.; Andaluz N.; Chesnut R. M.; Bullock M. R.; Grant G. A.; McGregor J.; Weaver M.; Jallo J.; LeRoux P. D.; Moberg D.; Barber J.; Lazaridis C.; Diaz-Arrastia R. R. Brain Oxygen Optimization in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Phase-II: A Phase II Randomized Trial. Crit Care Med. 2017, 45 (11), 1907–1914. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tageldeen M. K.; Gowers S. A. N.; Leong C. L.; Boutelle M. G.; Drakakis E. M. Traumatic Brain Injury Neuroelectrochemical Monitoring: Behind-the-Ear Micro-Instrument and Cloud Application. J. Neuroeng Rehabil 2020, 17 (1), 114. 10.1186/s12984-020-00742-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier J. P. The Role of Spreading Depression, Spreading Depolarization and Spreading Ischemia in Neurological Disease. Nat. Med. 2011, 17 (4), 439–447. 10.1038/nm.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayata C.; Lauritzen M. Spreading Depression, Spreading Depolarizations, and the Cerebral Vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2015, 95 (3), 953–993. 10.1152/physrev.00027.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carre E.; Ogier M.; Boret H.; Montcriol A.; Bourdon L.; Risso J. J. Metabolic Crisis in Severely Head-Injured Patients: Is Ischemia Just the Tip of the Iceberg. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 1–6. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasicek T. W.; Jackson M. R.; Poseno T. M.; Stenken J. A. In Vivo Microdialysis Sampling of Cytokines from Rat Hippocampus: Comparison of Cannula Implantation Procedures. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4 (5), 737–746. 10.1021/cn400025m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H.; Varner E. L.; Groskreutz S. R.; Michael A. C.; Weber S. G. In Vivo Monitoring of Dopamine by Microdialysis with 1 min Temporal Resolution Using Online Capillary Liquid Chromatography with Electrochemical Detection. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 6088–6094. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund N.; Clausen F.; Lewander T.; Hillered L. Monitoring of Reactive Oxygen Species Production after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats with Microdialysis and the 4-Hydroxybenzoic Acid Trapping Method. J. Neurotrauma 2001, 18 (11), 1217–1227. 10.1089/089771501317095250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt K. M.; Jaquins-Gerstl A.; Skoda E. M.; Wipf P.; Michael A. C. Pharmacological Mitigation of Tissue Damage during Brain Microdialysis. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85 (17), 8173–8179. 10.1021/ac401201x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Jaquins-Gerstl A.; Nesbitt K. M.; Rutan S. C.; Michael A. C.; Weber S. G. In Vivo Monitoring of Serotonin in the Striatum of Freely Moving Rats with One Minute Temporal Resolution by Online Microdialysis-Capillary High-Performance Liquid Chromatography at Elevated Temperature and Pressure. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85 (20), 9889–9897. 10.1021/ac4023605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt K. M.; Varner E. L.; Jaquins-Gerstl A.; Michael A. C. Microdialysis in the Rat Striatum: Effects of 24 h Dexamethasone Retrodialysis on Evoked Dopamine Release and Penetration Injury. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6 (1), 163–173. 10.1021/cn500257x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varner E. L.; Jaquins-Gerstl A.; Michael A. C. Enhanced Intracranial Microdialysis by Reduction of Traumatic Penetration Injury at the Probe Track. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7 (6), 728–736. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varner E. L.; Leong C. L.; Jaquins-Gerstl A.; Nesbitt K. M.; Boutelle M. G.; Michael A. C. Enhancing Continuous Online Microdialysis Using Dexamethasone: Measurement of Dynamic Neurometabolic Changes during Spreading Depolarization. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8 (8), 1779–1788. 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. L.; Leong C. L.; Gowers S. A. N.; Samper I. C.; Jewell S. L.; Khan A.; McCarthy L.; Pahl C.; Tolias C. M.; Walsh D. C.; Strong A. J.; Boutelle M. G. Simultaneous Monitoring of Potassium, Glucose and Lactate during Spreading Depolarization in the Injured Human Brain - Proof of Principle of a Novel Real-Time Neurochemical Analysis System, Continuous Online Microdialysis. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2017, 37 (5), 1883–1895. 10.1177/0271678X16674486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong C. L.; Wickham A. P.; Samper I. C.; Gowers S. A. N.; Boutelle M. G.; Rogers M. L.; Booth M. A. Chemical Monitoring in Clinical Settings: Recent Developments toward Real-Time Chemical Monitoring of Patients. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90 (1), 2–18. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagkalos I.; Rogers M. L.; Boutelle M. G.; Drakakis E. M. A High-Performance Application Specific Integrated Circuit for Electrical and Neurochemical Traumatic Brain Injury Monitoring. ChemPhysChem 2018, 19 (10), 1215–1225. 10.1002/cphc.201701119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samper I. C.; Gowers S. A. N.; Rogers M. L.; Murray D. S. R. K.; Jewell S. L.; Pahl C.; Strong A. J.; Boutelle M. G. 3D Printed Microfluidic Device for Online Detection of Neurochemical Changes with High Temporal Resolution in Human Brain Microdialysate. Lab Chip 2019, 19 (11), 2038–2048. 10.1039/C9LC00044E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samper I. C.; Gowers S. A.; Booth M. A.; Wang C.; Watts T.; Phairatana T.; Vallant N.; Sandhu B.; Papalois V.; Boutelle M. G. Portable Microfluidic Biosensing System for Real-Time Analysis of Microdialysate in Transplant Kidneys. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 14631–14638. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins E. M.; Jaquins-Gerstl A.; Fine D. F.; Leong C. L.; Dixon C. E.; Wagner A. K.; Boutelle M. G.; Michael A. C. Extended (10-Day) Real-Time Monitoring by Dexamethasone-Enhanced Microdialysis in the Injured Rat Cortex. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 3521–3531. 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford E. K.; Robbins E. M.; Jaquins-Gerstl A.; Rerick M. T.; Nwachuku E. L.; Weber S. G.; Boutelle M. G.; Okonkwo D. O.; Puccio A. M.; Michael A. C. Validation of Dexamethasone-Enhanced Continuous-Online Microdialysis for Monitoring Glucose for 10 Days After Brain Injury. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 3588. 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux A.; Muller L.; Jackson S. N.; Post J.; Baldwin K.; Hoffer B.; Balaban C. D.; Barbacci D.; Schultz J. A.; Gouty S.; Cox B. M.; Woods A. S. Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Rat Brain Lipid Profile Changes over Time Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurosci Methods 2016, 272, 19–32. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant-Pokam P. A.; Vail T. J.; Metcalf C. S.; Maguire J. L.; McKean T. O.; McKean N. O.; Brennan K. C. Preventing Neuronal Edema Increases Network Excitability after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130 (11), 6005–6020. 10.1172/JCI134793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. K.; Sokoloski J. E.; Chen X.; Harun R.; Clossin D. P.; Khan A. S.; Andes-Koback M.; Michael A. C.; Dixon C. E. Controlled Cortical Impact Injury Influences Methylphenidate-Induced Changes in Striatal Dopamine Neurotransmission. J. Neurochem 2009, 110 (3), 801–810. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. L.; Brennan P. A.; Leong C. L.; Gowers S. A. N.; Aldridge T.; Mellor T. K.; Boutelle M. G. Online Rapid Sampling Microdialysis (RsMD) Using Enzyme-Based Electroanalysis for Dynamic Detection of Ischaemia during Free Flap Reconstructive Surgery. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013, 405 (11), 3881–3888. 10.1007/s00216-013-6770-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balança B.; Meiller A.; Bezin L.; Dreier J. P.; Marinesco S.; Lieutaud T. Altered Hypermetabolic Response to Cortical Spreading Depolarizations after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2017, 37 (5), 1670–1686. 10.1177/0271678X16657571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allioux C.; Meiller A.; Balança B.; Marinesco S.. Monitoring Brain Injury with Microelectrode Biosensors. In Compendium of In Vivo Monitoring in Real-Time Molecular Neuroscience; Wilson G. S., Michael A. C., Eds.; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chatard C.; Sabac A.; Moreno-Velasquez L.; Meiller A.; Marinesco S. Minimally Invasive Microelectrode Biosensors Based on Platinized Carbon Fibers for in Vivo Brain Monitoring. ACS Cent Sci. 2018, 4 (12), 1751–1760. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings F. A.; Schuurman P. R.; van den Munckhof P.; Bouma G. J. Brain Tissue Oxygen Pressure Monitoring in Awake Patients during Functional Neurosurgery: The Assessment of Normal Values. J. Neurotrauma 2008, 25 (10), 1173–1177. 10.1089/neu.2007.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafidi S.; O’Brien J.; Hopkins I.; Robertson C.; Fiskum G.; McKenna M. Delayed Cerebral Oxidative Glucose Metabolism after Traumatic Brain Injury in Young Rats. J. Neurochem. 2009, 109 (Suppl. 1), 189–197. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer R.; Franz G.; Srinivasan A.; Hayes R. L.; Pike B. R.; Newcomb J. K.; Zhao X.; Schmutzhard E.; Poewe W.; Kampfl A. Temporal Profile and Cell Subtype Distribution of Activated Caspase-3 Following Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurochem 2000, 75 (3), 1264–1273. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartings J. A.; Gugliotta M.; Gilman C.; Strong A. J.; Tortella F. C.; Bullock M. R. Repetitive Cortical Spreading Depolarizations in a Case of Severe Brain Trauma. Neurol Res. 2008, 30 (8), 876–882. 10.1179/174313208X309739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartings J. A. Spreading Depolarization Monitoring in Neurocritical Care of Acute Brain Injury. Curr. Opin Crit Care 2017, 23 (2), 94–102. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal G.; Hemphill J. C.; Sorani M.; Martin C.; Morabito D.; Obrist W. D.; Manley G. T. Brain Tissue Oxygen Tension Is More Indicative of Oxygen Diffusion than Oxygen Delivery and Metabolism in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care Med. 2008, 36 (6), 1917–1924. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181743d77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood S. E.; Parkin M. C.; Bezzina E. L.; Boutelle M. G.; Strong A. J. Transient Changes in Cortical Glucose and Lactate Levels Associated with Peri-Infarct Depolarisations, Studied with Rapid-Sampling Microdialysis. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2005, 25 (3), 391–401. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi P.; Bhatia R.; Nakamura H.; Dreier J. P.; Graf R.; Strong A. J.; Boutelle M. G. Persisting Depletion of Brain Glucose Following Cortical Spreading Depression, despite Apparent Hyperaemia: Evidence for Risk of an Adverse Effect of Leao’s Spreading Depression. Journal Cerebral Blood Flow Metabolism 2009, 29 (1), 166–175. 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P.; Boonyaputthikul R.; McArthur D. L.; Miller C.; Etchepare M.; Bergsneider M.; Glenn T.; Martin N.; Hovda D. Intensive Insulin Therapy Reduces Microdialysis Glucose Values without Altering Glucose Utilization or Improving the Lactate/Pyruvate Ratio after Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care Med. 2006, 34 (3), 850–856. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201875.12245.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P.; McArthur D. L.; Stein N.; Huang S. C.; Shao W.; Filippou M.; Etchepare M.; Glenn T.; Hovda D. A. Tight Glycemic Control Increases Metabolic Distress in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled within-Subjects Trial. Crit Care Med. 2012, 40 (6), 1923–1929. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e0fcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozai T. D. Y.; Jaquins-Gerstl A. S.; Vazquez A. L.; Michael A. C.; Cui X. T. Brain Tissue Responses to Neural Implants Impact Signal Sensitivity and Intervention Strategies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 48–67. 10.1021/cn500256e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozai T. D. Y.; Jaquins-Gerstl A. S.; Vazquez A. L.; Michael A. C.; Cui X. T. Dexamethasone Retrodialysis Attenuates Microglial Response to Implanted Probes in Vivo. Biomaterials 2016, 87, 157–169. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leis J. A.; Bekar L. K.; Walz W. Potassium Homeostasis in the Ischemic Brain. Glia 2005, 50 (4), 407–416. 10.1002/glia.20145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapilover E. G.; Lippmann K.; Salar S.; Maslarova A.; Dreier J. P.; Heinemann U.; Friedman A. Peri-Infarct Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Facilitates Induction of Spreading Depolarization Associated with Epileptiform Discharges. Neurobiol Dis 2012, 48 (3), 495–506. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler M. K. L.; Chassidim Y.; Lublinsky S.; Revankar G. S.; Major S.; Kang E. J.; Oliveira-Ferreira A. I.; Woitzik J.; Sandow N.; Scheel M.; Friedman A.; Dreier J. P. Impaired Neurovascular Coupling to Ictal Epileptic Activity and Spreading Depolarization in a Patient with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Possible Link to Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction. Epilepsia 2012, 53 (s6), 22–30. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viggiano E.; Monda V.; Messina A.; Moscatelli F.; Valenzano A.; Tafuri D.; Cibelli G.; de Luca B.; Messina G.; Monda M. Cortical Spreading Depression Produces a Neuroprotective Effect Activating Mitochondrial Uncoupling Protein-5. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016, 12, 1705–1710. 10.2147/NDT.S107074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normoyle K. P.; Kim M.; Farahvar A.; Llano D.; Jackson K.; Wang H. The Emerging Neuroprotective Role of Mitochondrial Uncoupling Protein-2 in Traumatic Brain Injury. Transl Neurosci 2015, 6 (1), 179–186. 10.1515/tnsci-2015-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcote T.; Hinzman J. M.; Jewell S. L.; Learney R. M.; Pahl C.; Tolias C.; Walsh D. C.; Hocker S.; Zakrzewska A.; Fabricius M. E.; Strong A. J.; Hartings J. A.; Boutelle M. G. Detection of Spreading Depolarization with Intraparenchymal Electrodes in the Injured Human Brain. Neurocrit Care 2014, 20 (1), 21–31. 10.1007/s12028-013-9938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier J. P.; Fabricius M.; Ayata C.; Sakowitz O. W.; Shuttleworth C. W.; Dohmen C.; Graf R.; Vajkoczy P.; Helbok R.; Suzuki M.; Schiefecker A. J.; Major S.; Winkler M. K. L.; Kang E.-J.; Milakara D.; Oliveira-Ferreira A. I.; Reiffurth C.; Revankar G. S.; Sugimoto K.; Dengler N. F.; Hecht N.; Foreman B.; Feyen B.; Kondziella D.; Friberg C. K.; Piilgaard H.; Rosenthal E. S.; Westover M. B.; Maslarova A.; Santos E.; Hertle D.; Platz J.; Jewell S. L.; Balanc B.; Schoknecht K.; Hinzman J. M.; Lu J.; Drenckhahn C.; Feuerstein D.; Eriksen N.; Horst V.; Rostrup E.; Pakkenberg B.; Heinemann U.; Friedman A.; Brinker G.; Reiner M.; Vatter H.; Chung L. S.; Brennan K. C.; Lieutaud T.; Marinesco S.; Richter F.; Herreras O.; Boutelle M. G.; Strong A. J.; Hartings J. A.; et al. Recording, Analysis, and Interpretation of Spreading Depolarizations in Neurointensive Care: Review and Recommendations of the COSBID Research Group. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37 (5), 1595–1625. 10.1177/0271678X16654496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seule M.; Keller E.; Unterberg A.; Sakowitz O. The Hemodynamic Response of Spreading Depolarization Observed by Near Infrared Spectroscopy After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2015, 23 (1), 108–112. 10.1007/s12028-015-0111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs C. N.; Johnson J. A.; Verber M. D.; Wightman R. M. An Implantable Multimodal Sensor for Oxygen, Neurotransmitters, and Electrophysiology during Spreading Depolarization in the Deep Brain. Analyst 2017, 142 (16), 2912–2920. 10.1039/C7AN00508C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nortje J.; Gupta A. K. The Role of Tissue Oxygen Monitoring in Patients with Acute Brain Injury. Br J. Anaesth 2006, 97 (1), 95–106. 10.1093/bja/ael137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Venton B. J. Comparison of Spontaneous and Mechanically-Stimulated Adenosine Release in Mice. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 124, 46–50. 10.1016/j.neuint.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler M. K. L.; Dengler N.; Hecht N.; Hartings J. A.; Kang E. J.; Major S.; Martus P.; Vajkoczy P.; Woitzik J.; Dreier J. P. Oxygen Availability and Spreading Depolarizations Provide Complementary Prognostic Information in Neuromonitoring of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Patients. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2017, 37 (5), 1841–1856. 10.1177/0271678X16641424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelper B. M.; Alessandri B.; Heimann A.; Behr R.; Kempski O. Brain Oxygen Monitoring: In-Vitro Accuracy, Long-Term Drift and Response-Time of Licox- and Neurotrend Sensors. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005, 147 (7), 767–774. 10.1007/s00701-005-0512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.