Key Words: axon regeneration, central nervous system, gene therapy, mRNA translation, neurodegeneration, neuroprotection, optic nerve crush, Ras homolog enriched in the brain, retina, translation initiation

Abstract

Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb) is a small GTPase that activates mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). Previous studies have shown that constitutively active Rheb can enhance the regeneration of sensory axons after spinal cord injury by activating downstream effectors of mTOR. S6K1 and 4E-BP1 are important downstream effectors of mTORC1. In this study, we investigated the role of Rheb/mTOR and its downstream effectors S6K1 and 4E-BP1 in the protection of retinal ganglion cells. We transfected an optic nerve crush mouse model with adeno-associated viral 2-mediated constitutively active Rheb and observed the effects on retinal ganglion cell survival and axon regeneration. We found that overexpression of constitutively active Rheb promoted survival of retinal ganglion cells in the acute (14 days) and chronic (21 and 42 days) stages of injury. We also found that either co-expression of the dominant-negative S6K1 mutant or the constitutively active 4E-BP1 mutant together with constitutively active Rheb markedly inhibited axon regeneration of retinal ganglion cells. This suggests that mTORC1-mediated S6K1 activation and 4E-BP1 inhibition were necessary components for constitutively active Rheb-induced axon regeneration. However, only S6K1 activation, but not 4E-BP1 knockdown, induced axon regeneration when applied alone. Furthermore, S6K1 activation promoted the survival of retinal ganglion cells at 14 days post-injury, whereas 4E-BP1 knockdown unexpectedly slightly decreased the survival of retinal ganglion cells at 14 days post-injury. Overexpression of constitutively active 4E-BP1 increased the survival of retinal ganglion cells at 14 days post-injury. Likewise, co-expressing constitutively active Rheb and constitutively active 4E-BP1 markedly increased the survival of retinal ganglion cells compared with overexpression of constitutively active Rheb alone at 14 days post-injury. These findings indicate that functional 4E-BP1 and S6K1 are neuroprotective and that 4E-BP1 may exert protective effects through a pathway at least partially independent of Rheb/mTOR. Together, our results show that constitutively active Rheb promotes the survival of retinal ganglion cells and axon regeneration through modulating S6K1 and 4E-BP1 activity. Phosphorylated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 promote axon regeneration but play an antagonistic role in the survival of retinal ganglion cells.

Introduction

Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are susceptible to a wide range of pathological conditions such as elevated intraocular pressure, trauma, ischemia and inflammation that can lead to irreversible vision loss (Levin and Gordon, 2002; Lang et al., 2021; Ibad et al., 2022). The optic nerve has been widely used to investigate the response of the central nervous system (CNS) to injury because of its accessibility, anatomy, and functional importance (Li et al., 2017). The optic nerve in adult mammals has a very limited ability to regenerate because of the low intrinsic regenerative capacity of RGCs, as well as the inhibitory environment in CNS (Schwab and Bartholdi, 1996; Goldberg et al., 2002). Accordingly, the identification of strategies aimed at protecting RGCs after injury to preserve visual function is currently the subject of substantial research attention.

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a critical regulator of mRNA translation in response to nutrient supply, growth factors, and other signals (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004; Inoki et al., 2005). The induction of mTOR by activated PI3K is mediated by Rheb, a small GTPase localized to endo-membrane compartments (Zhang et al., 2003; Sancak et al., 2008; Ferguson, 2015; Ben-Sahra and Manning, 2017; Angarola and Ferguson, 2019), which is required to stimulate the activity of mTOR (Groenewoud and Zwartkruis, 2013; Demetriades et al., 2014). mTORC1 phosphorylates two effectors, 4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), which participate in cap-dependent mRNA translation and regulation of protein synthesis (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004). S6K1 phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 4B and enhances the RNA helicase activity of eIF4A in the translation pre-initiation complex (Raught et al., 2004; Holz et al., 2005). Unphosphorylated 4E-BP1 interacts with the translation initiation factor eIF4E and prevents the initiation of cap-dependent translation by sequestering eIF4E. Phosphorylated 4E-BP1 releases from the 4E-BP1-eIF4E complex and therefore enables the recruitment of eIF4G and eIF4A to the 5′ end of mRNA, allowing translation initiation (Gingras et al., 1999). While studies have shown that PI3K-mTOR pathway plays a part in CNS axon regeneration (Park et al., 2008; Miao et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019a), the specific role of mTOR downstream effectors and mechanisms have not been fully demonstrated.

Growing evidence suggests that Rheb has a role in neural and synaptic plasticity (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009), dendritic morphogenesis (Kumar et al., 2005; Tavazoie et al., 2005), neural activity (Yang et al., 2021), neural polarity and axon guidance (Li et al., 2008; Nie et al., 2010), and neural apoptosis (Shu et al., 2014). Constitutively active Rheb (caRheb) protects dopaminergic neurons, such as hippocampal neurons and nigrostriatal neurons, against neurotoxicity by increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor levels through activation of the mTORC1-Creb signaling pathway (Kim et al., 2011, 2012; Jeon et al., 2015, 2020; Jeong et al., 2015; Nam et al., 2015). Moreover, in vivo studies showed that caRheb expression potentiated the regrowth of intrinsic sensory axons across the dorsal root entry zone after spinal cord injury by activating proteins downstream of mTOR (Wu et al., 2015).

Here, we sought to determine the roles of Rheb/mTOR and the downstream effectors S6K1 and 4E-BP1 in RGC protection after injury. To this end, we used caRheb containing a point mutation that results in persistent binding to GTP (Yan et al., 2006) in conjunction with an optic nerve crush (ONC) mouse model and evaluated the neuroprotective effect of Rheb through the assessment of RGC survival and the extent of axon regeneration.

Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were conducted following the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement on the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research (Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, 2021) and the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011). All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Xiangya Medical School of Central South University (approval No. 2022750) on October 1, 2020. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice (male, 6–8 weeks old, weighing 20–25 g) were obtained from the animal facility of the Second Xiangya Hospital (license No. SYXK 2017-0002) and maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions. The mice were randomly divided into sham operation and axotomy groups. In the axotomy group, mice were further divided into control and treatment groups.

Adeno-associated viral vector production

Previous studies have demonstrated that adeno-associated viral (AAV)2 has a specific tropism for RGCs. All the viral vectors used in this study were of the AAV2 serotype (Pang et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2021). Plasmids carrying 4E-BP1 (NM_007918.3) and S6K1 (NM_001114334.2) complementary DNA sequences were purchased from BrainVTA (Wuhan, China). Mutants (4E-BP1-4A: T36A, T45A, S64A, T69A; DN-S6K: T252A; caS6K1: S434D, S441D, S447D, T444E, T412E) were generated using the Phusion Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) in the pGEM-T vector (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA) and then cloned into an AAV2 packaging construct containing the CAG promoter. A FLAG, HA, or GFP tag was inserted into the N terminus of target genes. The 4E-BP1 (Gene ID: 13685) short hairpin RNA sequence was cloned into the pAAV-U6-CAG-ZsGreen vector. The target sequence was 5′-AGG CGG TGA AGA GTC ACA ATT-3′. Plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

AAV was prepared using triple plasmid transfection in HEK293 cells (DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany, Cat# ACC-305, RRID: CVCL_0045). The main pAAV plasmid contained AAV2 ITRs. After HEK293 cell lysis, viral particles were purified by CsCl gradient ultracentrifugation. Recombinant AAV titers were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. AAV2-EGFP was subcloned into the same viral backbone. The AAV2 titers used in this study were in the range of 2.5–3.0 × 1012 genome copies/µL.

Intravitreal injection and ONC

Intravitreal injection and ONC were performed as previously described (Huang et al., 2019b). Briefly, after anesthesia by intraperitoneal injection of 1% sodium pentobarbital (8 mL/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), the left eye was first dilated with compound tropicamide eye drops (Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and then 1 µL of AAV (approximately 2.5–3.0 × 1012 genome copies) was injected into the vitreous chamber using a 30G Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Co., Bonaduz, Switzerland).

Two weeks after injection, the left optic nerve was exposed intraorbitally under a surgical microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and crushed for 3 seconds with cross-action forceps 1 mm behind the eyeball to avoid disrupting the blood supply to the optic nerve. For the sham operation, the optic nerve was exposed but not crushed. For the selection of the crushing time, we referred to previous literature (Watkins et al., 2013; Miao et al., 2016; Tran et al., 2019). After surgery, the mouse was placed on a heating pad and monitored until it had fully recovered from anesthesia.

Immunostaining of retinal sections

Mice were euthanized by CO2 narcosis by continuously increasing the concentration of CO2 until respiratory and cardiac arrest. The CO2 replacement rate was 30–70%, which ensured that the mice had lost consciousness without causing pain. The intervention time for CO2 was 35 minutes. Mice were perfused with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA); the eyeballs were dissected out and fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight. The eyeballs were then dehydrated overnight with increasing concentrations of sucrose solution (10%, 20%, and 30%) and then embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound on dry ice. Serial cross-sections (14 µm) were obtained using a Leica cryostat (CM1950, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and directly collected onto microscope slides. The retinal sections were blocked in blocking buffer (10% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: β-III tubulin (mouse, 1:400, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab78078, RRID: AB_2256751), β-III tubulin (rabbit, 1:400, Abcam, Cat# ab52623, RRID: AB_869991), hemagglutinin (HA; rabbit, 1:150, Abcam, Cat# ab236632; RRID: AB_2864361), phospho-AKT-T308 (rabbit, 1:200, Abcam, Cat# ab38449; RRID: AB_722678), phospho-S6 (p-S6)-Ser240/244 (rabbit, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA, Cat# 5364S, RRID: AB_10694233), and 4E-BP1 (rabbit, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 9644S, RRID: AB_2097841). After washing three times with PBS, 15 minutes each wash, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies (Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488), 1:300, Cat# ab150113, RRID: AB_2576208; Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488), 1:300, Cat# ab150077, RRID: AB_2630356; Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 555), 1:300, Cat# ab150118, RRID: AB_2714033; Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 555), 1:300, Cat# ab150078, RRID: AB_2722519; Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 647), 1:300, Cat# ab150115, RRID: AB_2687948; Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 647), 1:300, Cat# ab150083, RRID: AB_2714032; all from Abcam) for 1.5 hours at 25°C, followed by counterstaining with 4′,6-diamidino-2′-phenylindole and washing with PBS (3 × 15 minutes). The sections were observed and imaged at 200× magnification using a fluorescence microscope (Axio Imager M2, Carl Zeiss). Images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop software (Version 12.0; San Jose, CA, USA).

Cholera toxin B subunit tracing and quantitation of axon regeneration

To label regenerating axons in the optic nerve, 2 µL of cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 (2 µg/mL, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was injected into the vitreous chamber 2 days before euthanasia with CO2. Animals were euthanized and fixed by perfusion with 4% PFA in cold PBS. The optic nerve was gently dissected out as previously described (Cameron et al., 2020) and postfixed in PFA for another 2 hours at room temperature. Tissues were dehydrated through increasing concentrations of sucrose (15–30%), embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura, Osaka, Japan), snap-frozen in dry ice, and sliced into serial longitudinal cross-sections (14 µm) for imaging (200×) under a fluorescence microscope (Axio Imager M2). CTB-labeled axons were quantified at 250, 500, 750, 1000, 1500, and 2000 µm distal to the crush site. The width of the nerve (R) was measured at the point (d) where the counts were made and, together with the thickness of the section (t = 14 µm), was used to calculate the number of axons per μm2 area of the nerve using the following equation: ∑ad = πr2 × axon number/(R × t). The total number of axons per section was then averaged over three sections per animal. The quantification of regenerated axons was performed by a single person blinded to the experimental conditions.

Immunohistochemistry of flat-mount retina and quantitative evaluation of RGC survival

Mice were anesthetized and transcardially perfused first with 0.9% ice-cold saline and then with 4% PFA. The eyeballs were dissected out and post-fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight. The retinas were carefully dissected out from the fixed eyeballs, washed extensively in PBS, blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 1.5 hours, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: β-III tubulin (mouse/rabbit, 1:400), neurofilament H (SMI-32) (mouse, 1:200, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA, Cat# 801701, RRID: AB_2564642), and p-S6-Ser240/244 (rabbit, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 5364S; RRID: AB_10694233). After washing three times with PBS, 15 minutes each wash, the retinas were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:300, the same antibodies used for immunostaining) for 1.5 hours at room temperature, and washed again three times with PBS for 30 minutes each wash.

For RGC quantification, whole-mount retinas were immunostained with the Tuj1 antibody in 6–8 fields randomly sampled from peripheral regions of each retina. For RGC size quantification, whole-mount retinas were immunostained with the Tuj1 antibody in four fields randomly sampled from the peripheral regions of each retina. We used ZEN 2.3 software (blue edition; Carl Zeiss) to analyze the RGC size. The boundaries of RGC somas were manually marked and the area of each RGC soma was recorded.

Rapamycin administration

Rapamycin (Sigma) was dissolved in ethanol to yield a 20 mg/mL stock solution. Before administration, rapamycin was diluted in PBS containing 5% Tween 80 and 5% polyethylene glycol 400 (1 mg/mL) in PBS. Rapamycin (6 mg/kg) or vehicle (6 mL/kg) was injected intraperitoneally once every 2 days after AAV injection (Guo et al., 2016).

Flash visual evoked potentials recording

For the recording of flash visual evoked potentials (FVEPs), we implanted an active electrode (silver needle electrode, diameter: 0.35 mm) in the mouse skull at 2.3 mm horizontal to lambda (overlying the primary visual cortex). Electrodes with an alligator clip were used to connect the silver needle electrodes in the skull. The reference electrode was buried under the skin between the eyes and the ground electrode was embedded at the base of the tail. FVEPs were recorded 2 days after embedding. After anesthesia, mice were placed on a heating pad and kept warm during the procedure. After 30 minutes of dark adaptation, the pupils were dilated and the animals were anesthetized. A flash of white light (3 cd·s/m2) was delivered 64 times at a frequency of 1 Hz. Electrical signals were amplified 1000 times and band-pass filtered (1–100 Hz). AAV injection and ONC treatment were performed on one eye for each mouse; the contralateral eye was blocked from light. FVEPs were recorded using a Multifocal Visual Electrophysiological System (RetiMINER System; AiErXi Medical Equipment Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) and P1 responses were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.01 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). To identify significant differences between two treatment means, data were analyzed using unpaired t-test. One-way or two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. All tests were two-sided. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. All data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

Overexpression of caRheb leads to the upregulation of the mTOR pathway in RGCs and promotes RGC survival in ONC mice

ONC in animals has been used as a model for acute RGC degeneration (Kalesnykas et al., 2012), with nearly 80% of RGCs lost by 2 weeks after injury (Guo et al., 2021). We performed ONC in mice; the number of RGCs started to decline on day 7 post-crush, and only ~25% of RGCs survived 14 days post-crush (dpc) (Additional Figure 1A (475.2KB, tif) and B (475.2KB, tif) ). The phosphorylation and activation of S6K1 by mTORC1 and the subsequent phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (Jefferies et al., 1997) at (Ser240/244) are widely used as a readout of mTOR activity (Ikenoue et al., 2009). We found that the mTOR pathway was downregulated in RGCs following ONC, as evidenced by the reduction in p-S6 immunofluorescence staining in flat-mounted retinas (Additional Figure 1A (475.2KB, tif) ). The level of p-S6 in RGCs began to decline on day 5, while the number of RGCs started to decrease on day 7, indicating that downregulation of the mTOR pathway preceded the loss of RGCs (Additional Figure 1A (475.2KB, tif) and C (475.2KB, tif) ).

Next, an AAV2 viral vector carrying Rheb(S16H) (AAV-caRheb), a constitutively active form of Rheb (Kim et al., 2011, 2012; Jeon et al., 2015), was injected into the vitreous cavity of mice 14 days before axotomy, and the mice were euthanized on 14, 21, and 42 dpc (Figure 1A). Both AAV-caRheb and AAV-EGFP displayed high transfection efficiency in RGCs (Additional Figure 2 (672.6KB, tif) ), and AAV-EGFP or AAV-caRheb itself did not lead to loss of RGCs (Additional Figure 3A (405.6KB, tif) and B (405.6KB, tif) ). Following the transfection of AAV-caRheb, the percentage of p-S6+ RGCs markedly increased from ~30% to ~70% and remained at a high level even after axotomy (Figure 1B–D), indicative of the constitutive activation of the mTOR pathway mediated by caRheb. Overexpression of caRheb also led to a marked increase in the size of RGCs and exerted neural protective effects after axotomy. RGC cell counts were similar in sham operation groups at all time points (Figure 1E and F). During the post-acute phase of ONC (day 14 post-crush), AAV-caRheb treated mice had higher numbers of RGCs (75.9 ± 6.5/0.1 mm2) compared with AAV-EGFP-treated mice (51.2 ± 4.4/0.1 mm2) (P = 0.0003; Figure 1E and F). There was still a significant protective effect in chronic stages (days 21 and 42 post-crush), in which the caRheb group had significantly more RGCs (21 dpc: 71.2 ± 2.9/0.1 mm2, P = 0.0074; 42 dpc: 58.2 ± 6.7/0.1 mm2, P = 0.0008) than the EGFP group (21 dpc: (47.6 ± 1.9)/0.1 mm2; 42 dpc: 33.6 ± 4.1/0.1 mm2; Figure 1E and F). Moreover, RGC size was significantly larger after caRheb overexpression (Figure 1G).

Figure 1.

AAV-mediated transduction of caRheb increases p-S6 levels in RGCs and protects RGCs following ONC by increasing the survival of non-αRGCs.

(A) AAV-caRheb was administrated intravitreally to mice 2 weeks before ONC, and eyes were harvested on days 14, 21, and 42 after ONC. (B, C) caRheb increased the expression of p-S6. Immunofluorescence of retinal sections before and after injury in eyes transfected with AAV-caRheb or AAV-EGFP; staining was performed using p-S6 (red) or Tuj1 (green) antibodies. (D) Quantification of p-S6+ RGCs in EGFP and caRheb groups with and without ONC. Data are presented as the mean ratios of p-S6+ Tuj1+ cells among total Tuj1+ cells of each retina. Cell counts were performed in at least three nonconsecutive sections (mean ± SD, n = 3–4 per group). ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t-test. (E) Expression of caRheb increased the survival of RGCs. Immunofluorescence of flat-mount retinas from sham operation, AAV-EGFP, and AAV-caRheb groups on 14, 21, and 42 days after ONC showing surviving Tuj1+ RGCs (green). (F) Quantification of surviving Tuj1+ RGCs (mean ± SD, n = 6–8). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (G) Quantification of the size of surviving RGCs from AAV-EGFP and AAV-caRheb groups (mean ± SD, n = 6–8). ****P < 0.0001, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (H) Rheb-mediated increase of RGC survival was not through increasing the survival of α-RGCs. Immunofluorescence of flat-mount retinas for Tuj1 (red) (pan-RGCs) and SMI-32 (green) (α-RGCs) showed the surviving pan-RGCs and α-RGCs in AAV-EGFP and AAV-caRheb groups on day 14 after ONC. Scale bars: 40 µm (B, C, H), 60 µm (E). (I) Quantification of surviving non-α-RGCs. Data are presented as mean numbers of SMI-32– Tuj1+ cells of each retina, n = 4 for each group, ***P < 0.001, unpaired t-test. (J) Quantification of surviving α-RGCs. Data are presented as mean numbers of SMI-32+ Tuj1+ cells of each retina (mean ± SD, n = 4 for each group, unpaired t-test). AAV: Adeno-associated virus; caRheb: constitutively active Ras homolog enriched in brain; dpc: days post crush; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2′-phenylindole; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; ONC: optic nerve crush; p-S6: phospho-S6 ribosomal protein; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; Tuj1: β3-tubulin; SMI-32: neurofilament H.

There are over 30 subtypes of RGCs, and these subtypes can be distinguished by size, morphology, and function. The subtypes differ widely in their susceptibility to damage (Völgyi et al., 2009; Sanes and Masland, 2015; Daniel et al., 2018). Alpha-RGCs (α-RGCs), which have the largest somas, selectively exhibit high levels of mTOR activity (Duan et al., 2015; Kole et al., 2020) and have been reported as a type of RGC resistant to axotomy (Duan et al., 2015). We used Tuj1 to label pan-RGCs and SMI-32 for α-RGCs (Figure 1H); non-α-RGCs were determined as SMI-32– Tuj1+ cells. The number of non-α-RGCs was increased in the caRheb group compared with the EGFP group (54.6 ± 4.0/0.1 mm2 and 26.3 ± 5.0/0.1 mm2, respectively; P = 0.0001; Figure 1I); however, no significant difference was observed in α-RGCs (Figure 1J). These results indicated that stimulating mTOR activity prefers to rescue those RGC subtypes with low levels of endogenous mTOR activity.

Overexpressing caRheb promotes robust optic nerve regeneration

Next, we determined whether caRheb could induce axon regeneration. Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated CTB was intravitreally injected to label regenerating axons through the lesion site. Regenerating axons were quantified at different distances from the lesion site in longitudinal optic nerve sections. During the post-acute and chronic phases following axotomy, caRheb overexpression induced robust axon regeneration of RGCs on days 14, 21, and 42 after ONC (Figure 2A and C). Almost no regenerating axons were observed in the control group (Figure 2B and C).

Figure 2.

Expression of caRheb markedly promotes axon regeneration in ONC mice.

(A, B) Rheb induced robust axon regeneration. Images of optic nerve sections from AAV-caRheb and AAV-EGFP groups showing regenerating axons labeled by anterograde transport of CTB on days 14, 21, and 42 after ONC. Red asterisk indicates the crush site. Scale bars: 100 µm. (C) Quantification of regenerating axons 14 days post-crush from mice intravitreally injected with AAV-EGFP or AAV-caRheb at different distances distal to the lesion site (mean ± SD, n = 6–9). *P < 0.05, vs. AAV-EGFP group (two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test). AAV: Adeno-associated virus; caRheb: constitutively active Ras homolog enriched in brain; CTB: cholera toxin B subunit; dpc: days post crush; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; ONC: optic nerve crush; RGC: retinal ganglion cell.

To ascertain the role of mTORC1 in axonal regeneration induced by caRheb, we examined the effects of rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTORC1 (Zhou et al., 2009), on regenerating axons. Rapamycin or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally after AAV-caRheb injection (Figure 3A). We found that rapamycin treatment markedly decreased the basal level of p-S6 and attenuated the caRheb transfection-mediated increase in p-S6 (Figure 3B and C). Next, we performed ONC in rapamycin-treated mice 14 days after AAV-caRheb injection. We found that caRheb-mediated axon regeneration was abolished in rapamycin-treated animals (Figure 3D and E), indicating that activation of mTORC1 is necessary for caRheb-induced axon regeneration. Administration of rapamycin in caRheb-overexpressing mice significantly decreased RGC survival (caRheb: 75.9 ± 6.5/0.1 mm2; caRheb + Rapamycin: 66.4 ± 8.1/0.1 mm2, P = 0.0499), but not to levels of the vehicle-only group (Vehicle only: 50.7 ± 2.7/0.1 mm2, P = 0.0019; Additional Figure 4A (221.6KB, tif) and B (221.6KB, tif) ).

Figure 3.

Administration of rapamycin decreases p-S6 levels in RGCs and blocks axon regeneration induced by caRheb.

(A) Mice were intraperitoneally injected with rapamycin (6 mg/kg) every 2 days after AAV-caRheb injection until sacrifice. (B) Rapamycin significantly decreased p-S6 expression. Immunofluorescence analysis showing p-S6 (red) or Tuj1 (green) of the retinal sections in vehicle, rapamycin, AAV-caRheb + vehicle, and AAV-caRheb + rapamycin groups. (C) Quantification of p-S6+ RGCs in vehicle, rapamycin, AAV-caRheb + vehicle, and AAV-caRheb + rapamycin groups. Data are presented as mean ratios of p-S6+ Tuj1+ cells among total Tuj1+ cells of each retina. Cell counts were performed on at least three nonconsecutive sections (means ± SD, n = 4 per group). ***P < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (D) Rapamycin abolished the regeneration of axons induced by caRheb. Images of optic nerve sections of AAV-caRheb, AAV-caRheb + rapamycin, or vehicle groups showing regenerating axons on day 14 after ONC. Red asterisk indicates crush site. Scale bars: 40 µm (B), 100 µm (D). (E) Quantification of regenerating axons 14 days post-crush from AAV-caRheb, AAV-caRheb + rapamycin, or vehicle groups at different distances from the crushing site (mean ± SD, n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. AAV: Adeno-associated virus; caRheb: constitutively active Ras homolog enriched in brain; CTB: cholera toxin B subunit; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2′-phenylindole; dpc: days post-crush; ONC: optic nerve crush; p-S6: phospho-S6 ribosomal protein; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

Rheb activation improves ONC-induced visual dysfunction induced by ONC

Visual information leaves the eyes through the axons of RGCs, passes through several relay centers (lateral geniculate nucleus and superior colliculus), and finally reaches the primary visual cortex (Guo et al., 2021). We next tested whether AAV-caRheb treatment could help maintain RGC function. We recorded FVEP signals in primary visual cortices of animals from the sham, EGFP + ONC 21 dpc, and caRheb + ONC 21 dpc groups. Active electrodes and reference electrodes were implanted in the skull of mice (Figure 4A). Flashed visual stimulation induced a prominent P1 wave (92.5 ± 17.3 µV) in the sham group (Figure 4B), which was significantly reduced by ONC (15.1 ± 3.3 µV; P < 0.0001) (Figure 4C). caRheb treatment caused a significantly decreased decline in the amplitude of the P1 wave (34.4 ± 8.2 µV; P = 0.0057) compared with AAV-EGFP treated mice (15.1 ± 3.3 µV) following ONC (Figure 4D and E). The latency was significantly prolonged from 80.2 ± 8.5 ms to 130.7 ± 20.8 ms 21 days after ONC (P < 0.0001). In contrast to the significant improvement in amplitude seen with caRheb treatment, no shortening of the latency of the P1 wave was observed following caRheb administration (118.2 ± 14.5 ms, P = 0.3335; Figure 4F). This suggests overexpression of caRheb improved visual dysfunction by improving the P1 wave amplitude.

Figure 4.

caRheb improves visual dysfunction following ONC.

(A) Schematic diagram of the position of silver electrodes in mouse FVEP. (B–D) caRheb attenuated the impairment of visual function by ONC. Representative FVEP tracings of sham, EGFP, and caRheb groups 21 days post-crush (dpc). (E, F) Quantitative amplitude and latency of the P1 wave 21 days post-crush (mean ± SD, n = 8–9 per group). **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. AAV: Adeno-associated virus; caRheb: constitutively active Ras homolog enriched in brain; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; FVEP: flash visual evoked potential; Sham: sham operation; ONC: optic nerve crush.

Both S6K1 and 4E-BP1 participate in caRheb-induced axon regeneration

Activation of mTORC1 contributes to the axon outgrowth induced by caRheb. S6K1 and 4E-BP1, the two well-characterized downstream effectors of mTORC1, are potential therapeutic targets in promoting axon regeneration (Ma and Blenis, 2009).

We next investigated the role of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 in caRheb-induced RGC axon regeneration. S6K1 shows a dual potential in axon regeneration (Yaniv et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014; Al-Ali et al., 2017; Na et al., 2017); we thus constructed an AAV2 vector carrying a dominant-negative mutant of S6K1 (DN-S6K1) and AAV carrying a constitutively active mutant of S6K1 (caS6K1). We also generated an AAV2 viral vector carrying 4E-BP1-4A (a non-phosphorylatable 4E-BP1 mutant (Woodcock et al., 2019)) to overexpress a constitutively active form of 4E-BP1 in RGCs. This mutant is mTORC1-insensitive and constitutively binds to eIF4E to inhibit translation (Thoreen et al., 2012). Approximately 90% of RGCs in retina were infected after AAV2 virus intravitreal injection as determined by Tuj1/HA double labeling (Additional Figure 5 (880.1KB, tif) ). As expected, AAV2-mediated expression of caS6K1 led to a marked increase in p-S6 levels in RGCs, whereas DN-S6K elicited the opposite effect (Figure 5A). Overexpression of 4E-BP1-4A significantly increased 4E-BP1 levels in RGCs (Figure 5B). Equal titers (approximately 2.0 × 1012 genome copies) of AAV-caRheb and AAV-DN-S6K1, AAV-caS6K1, or AAV-4E-BP1-4A were premixed and intravitreally injected 2 weeks before ONC, and CTB was injected to anterogradely label the regenerating axons 2 days before euthanasia (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

S6K1 activation and inhibition of 4E-BP1 are necessary for caRheb-induced axon regeneration following ONC.

(A) DN-S6K1 decreased p-S6 expression while caS6K1 increased p-S6 expression. Immunofluorescence of retinal sections using p-S6 (red) or Tuj1 (green) antibodies from mice transfected with AAV-DN-S6K1 or AAV-caS6K1. (B) Delivery of 4E-BP1-4A increased 4E-BP1 expression while sh4E-BP1 decreased 4E-BP1 expression. Immunofluorescence analysis for 4E-BP1 levels in RGCs transfected with AAV-4E-BP1-4A or AAV-sh4E-BP1. Cells were stained with antibodies for 4E-BP1 (red) or Tuj1 (green). (C) Mixed injection of AAV was administrated intravitreally to mice 2 weeks before ONC. CTB was intravitreally injected 12 days after ONC and eyes were harvested on days 14 after ONC. (D) DN-S6K1 and 4E-BP1-4A decreased the regenerating axons induced by caRheb. Images of optic nerve sections showing regenerating axons labeled by anterograde transport of CTB on days 14 after ONC from eyes injected with AAV-caRheb, AAV-caRheb + DN-S6K1, AAV-caRheb + caS6K1, AAV-caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A, or AAV-EGFP. Red asterisk indicates crush site. Scale bars: 40 µm (A, B), 100 µm (D). (E) Quantification of regenerating axons 14 days post-crush from eyes injected with AAV-caRheb, AAV-caRheb + DN-S6K1, AAV-caRheb + caS6K1, or AAV-caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A at different distances distal to the lesion site. (F) Quantification of regenerating axons on day 14 post-crush from eyes injected with AAV-EGFP, AAV-caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A, or AAV-caRheb + DN-S6K1 at different distances distal to the lesion site. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8–10). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test). 4E-BP1-4A: Non-phosphorylatable 4E-BP1 mutant; AAV: adeno-associated virus; caRheb: constitutively active Ras homolog enriched in brain; caS6K1: constitutively active S6K1; CTB: cholera toxin B subunit; DN-S6K1: dominate negative S6K1; dpc: days post crush; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONC: optic nerve crush; ONL: outer nuclear layer; p-S6: phospho-S6 ribosomal protein; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; S6K1: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 downstream effector; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

Compared with the caRheb alone group, the caRheb + DN-S6K1 group showed significantly decreased numbers of regenerating axons (Figure 5D and E). Considerably more regenerating axons were seen in the caRheb + DN-S6K1 group than in the EGFP (control) group (Figure 5F). These results suggested that phosphorylated S6K1 is a necessary downstream effector of caRheb-induced regeneration. In addition, we found a slight increase in the number of regenerating axons in the caRheb + caS6K1 group compared with the caRheb alone group (Figure 5D). This observation suggested that S6K1 had a positive effect on regeneration in this context.

4E-BP1 is another potential downstream effector of mTORC1 involved in axon elongation (Li et al., 2008; Morita and Sobue, 2009). Compared with the caRheb alone group, the caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A group showed a striking reduction in the numbers of regenerating axons with completely abrogated axon outgrowth (Figure 5D–F). These results suggested that phosphorylation (and inhibition) of 4E-BP1 is necessary for caRheb-induced axon regeneration.

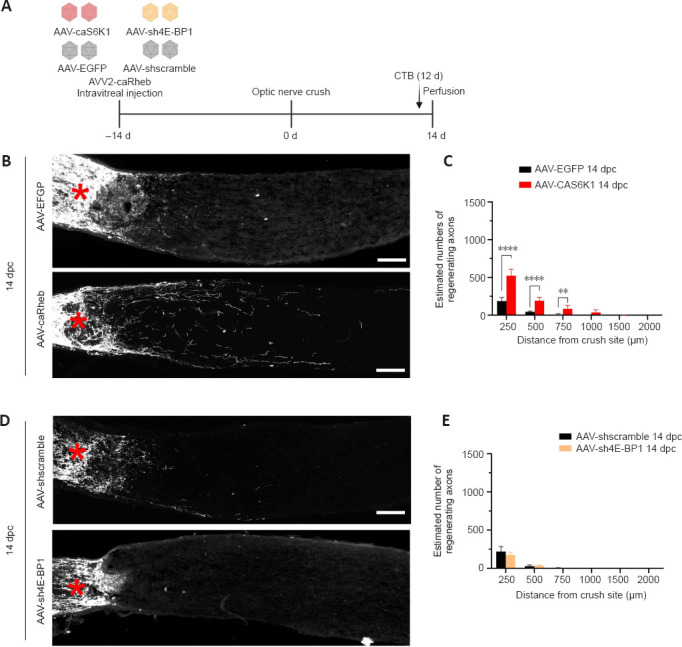

S6K1 activation, but not the knockdown of 4E-BP1, is sufficient to promote axon regeneration

Our results showed that DN-S6K1 and 4E-BP1-4A impaired caRheb-mediated axon regeneration. We then asked whether S6K1 activation alone or shRNA-mediated 4E-BP1 knockdown alone was sufficient to promote axon regeneration. Immunostaining confirmed the high transfection efficiency of AAV-sh4E-BP1 in RGCs (Additional Figure 5 (880.1KB, tif) ), with a significant reduction in basal 4E-BP1 levels (Figure 5B). ONC was performed 14 days after the intravitreal injection of AAV-caS6K1, AAV-EGFP, AAV-sh4E-BP1, and AAV-shscramble, and CTB was used to label the regenerating axons (Figure 6A). Expression of caS6K1 resulted in significant axon regeneration (Figure 6B and C). However, caS6K1 induced far less regenerating axons than caRheb, suggesting that factors in addition to S6K1 are involved in caRheb-induced axon regeneration. In contrast, no enhancement of axon outgrowth was detected by 4E-BP1 knockdown (Figure 6D and E). These results indicated that S6K1 activation alone, but not 4E-BP1 knockdown alone, is sufficient for inducing axon regrowth.

Figure 6.

S6K1 activation, but not the knockdown of 4E-BP1, is sufficient to promote axon regeneration.

(A) AAV-caS6K1 and AAV-sh4E-BP1 were administrated intravitreally to mice 2 weeks before ONC. CTB was intravitreally injected 12 days after ONC and optic nerves were harvested on day 14 after ONC. (B) Expression of caS6K1 induced axon regeneration. Images of optic nerve sections show regenerating axons labeled by anterograde transport of CTB on day 14 after optic nerve crush from AAV-EGFP- and AAV-caS6K1-injected eyes. (C) Quantification of regenerating axons 14 days post-crush from AAV-EGFP- and AAV-caS6K1-injected eyes at different distances distal from the crushing site (mean ± SD, n = 6–9). (D) Knockdown of 4E-BP1 did not induce axon regeneration. Images of optic nerve sections show regenerating axons labeled by anterograde transport of CTB on day 14 after ONC from AAV-shscramble and AAV-sh4E-BP1-injected eyes. Red asterisk indicates crush site. Scale bars: 100 µm (B, D). (E) Quantification of regenerating axons 14 days post-crush from AAV-shscramble- and AAV-sh4E-BP1-injected eyes at different distances from the crushing site (means ± SD, n = 6). **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 (two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test). 4E-BP1: Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 downstream effector; AAV: adeno-associated virus; caS6K1: constitutively active S6K1; CTB: cholera toxin B subunit; dpc: days post crush; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; ONC: optic nerve crush; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; S6K1: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 downstream effector.

Opposing effects of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation in promoting RGC survival

To investigate the role of S6K1 in RGC survival, we performed ONC in mice transfected with the S6K1 mutants and harvested the eyes 14 days post-crush (Figure 7A and B). caS6K1 expression resulted in a signifcantly increased size of RGCs (caS6K1: 243.7 ± 10.1 μm2; EGFP: 96.8 ± 6.7 μm2; P < 0.0001) while DN-S6K1 led to a slight reduction in the size of the cells (DN-S6K1: 77.8 ± 3.1 μm2; P = 0.0139) (Figure 7B and C). Quantification of the remaining RGCs by Tuj1 immunostaining in whole-mount retinas showed that the number of surviving RGCs was higher in the AAV-caS6K1 group (67.2 ± 2.6/0.1 mm2) than in the EGFP group (52.0 ± 5.4/0.1 mm2; P = 0.0001). No difference was observed in the number of surviving RGCs between the DN-S6K1 group (49.1 ± 3.6/0.1 mm2) and the EGFP group after ONC (P = 0.9166; Figure 7B and D).

Figure 7.

The survival of RGCs after ONC requires the activity of S6K1 and 4E-BP1.

(A) AAV-EGFP, AAV-caS6K1, and AAV-DN-S6K1 were administrated intravitreally to mice 2 weeks before ONC. Eyes were harvested on day 14 after ONC. (B) Overexpression of caS6K1 but not DN-S6K1 increased RGC survival. Fluorescent photomicrographs of retinal whole-mounts showing surviving Tuj1+ RGCs 14 dpc from eyes injected with AAV-EGFP, AAV-caS6K1, and AAV-DN-S6K1. (C) Quantification of sizes of surviving RGCs from AAV-EGFP, AAV-caS6K1, and AAV-DN-S6K1 groups (mean ± SD, n = 4). (D) Quantification of surviving Tuj1+ RGCs from eyes injected with AAV-EGFP, AAV-caS6K1, and AAV-DN-S6K1 (mean ± SD, n = 6–8). € AAV-EGFP, AAV-sh4E-BP1, and AAV-4E-BP1-4A were administrated intravitreally to mice 2 weeks before ONC. Eyes were harvested on day 14 after ONC. (F) Overexpression of 4E-BP1-4A increased RGC survival while knockdown of 4E-BP1 decreased RGC survival. Immunofluorescence of retinal whole-mounts showing surviving RGCs 14 dpc from AAV-EGFP, AAV-sh4E-BP1, and AAV-4E-BP1-4A groups. Scale bars: 60 µm (B, F). (G) Quantification of surviving RGCs from eyes injected with AAV-EGFP, sh4E-BP1, and 4E-BP1-4A (mean ± SD, n = 6–8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test). AAV: Adeno-associated virus; caS6K1: constitutively active S6K1; DN-S6K1: dominate negative S6K1; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; ONC: optic nerve crush; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; S6K1: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 downstream effector; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

As we found that 4E-BP1 phosphorylation plays a critical role in axon regeneration, we expected a similar effect of 4E-BP1 on RGC survival. To clarify the critical role of 4E-BP1 incapacitation in RGC survival, we performed AAV-mediated 4E-BP1 knockdown in RGCs (Figure 7E) and found a decreased number of surviving RGCs in the AAV-sh4E-BP1 group (36.3 ± 4.4/0.1 mm2) compared with the AAV-EGFP group (52.7 ± 2.8/0.1 mm2; P = 0.0017). Additionally, 4E-BP1-4A overexpression in ONC retina further increased surviving RGCs number compared with RGCs in the EGFP group (87.2 ± 8.6/0.1 mm2 vs. 52.7 ± 2.8/0.1 mm2, P < 0.0001) (Figure 7F and G). These results suggest that mTORC1-mediated 4E-BP1 incapacitation plays a deleterious role in the survival of RGCs.

Given these findings, we considered that 4E-BP1 overexpression may exert a protective effect through a different pathway independent of Rheb/mTOR. We therefore co-injected AAV-caRheb and AAV-4E-BP1-4A and tested whether co-expressed caRheb and 4E-BP1-4A had a greater effect on RGC survival than caRheb alone (Figure 8A). The results indeed showed that the co-expression of caRheb and 4E-BP1-4A exerted a more robust protective effect on RGC survival compared with administration of caRheb alone (Figure 8B). The number of surviving RGCs was significantly higher in the caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A group (121.7 ± 8.4/0.1 mm2) than in the EGFP (52.3 ± 3.4/0.1 mm2) and caRheb (75.9 ± 6.5/0.1 mm2) groups (Figure 8C). Co-injection of AAV-DN-S6K1 and AAV-caRheb significantly decreased the number of surviving RGCs compared with AAV-caRheb administration alone (50.2 ± 2.5/0.1 mm2 vs. 75.9 ± 6.5/0.1 mm2, P < 0.0001) (Figure 8B and C), which further confirmed that S6K1 is one of the necessary effectors in caRheb-mediated induction of RGC survival.

Figure 8.

Complementary modulation of Rheb and 4E-BP1 strikingly boosts RGC survival.

(A) AAV-EGFP, AAV-caRheb, AAV-caRheb + DN-S6K1, and AAV-caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A were administrated intravitreally to mice 2 weeks before ONC. Eyes were harvested on day 14 after ONC. (B) CaRheb + 4E-BP1-4A significantly increased the survival of RGCs while caRheb + DN-S6K1 significantly decreased RGC survival compared with caRheb alone. Fluorescent photomicrographs of retinal whole-mounts showed surviving Tuj1+ RGCs 14 dpc from eyes injected with AAV-EGFP, AAV-caRheb, AAV-caRheb + DN-S6K1, and AAV-caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A. Scale bars: 60 µm. (C) Quantification of surviving Tuj1+ RGCs from eyes injected with AAV-EGFP, AAV-caRheb, AAV-caRheb + DN-S6K1, and AAV-caRheb + 4E-BP1-4A. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6–8). ****P < 0.0001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test). AAV: Adeno-associated virus; caS6K1: constitutively active S6K1; DN-S6K1: dominate negative S6K1; dpc: days post crush; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; ONC: optic nerve crush; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; S6K1: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 downstream effector; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the neuroprotective role of Rheb in promoting axon regeneration and increasing RGC survival after ONC. Overexpression of caRheb in RGCs activated the mTORC1 pathway, leading to phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1 promotes protein synthesis and is necessary for axon regeneration. S6K1 phosphorylation also increases neural size and promotes RGC survival. However, we found that 4E-BP1, but not phosphorylated 4E-BP1, significantly increased RGC survival. Moreover, other undefined factors are also involved in caRheb-induced axon regeneration (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the role of the Rheb/mTORC1/S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathway in RGC survival and axon regeneration.

(A) S16H mutation in Rheb results in a constitutively GTP-bound Rheb as an activated form. Constitutively active Rheb stimulates mTORC1, which subsequently phosphorylates both S6K1 and 4E-BP1 and results in the promotion of protein synthesis. S6K1 is activated by phosphorylation, whereas 4E-BP1 is inhibited by phosphorylation. Both S6K1 activation and 4E-BP1 inhibition contribute to axon regeneration. Activated S6K1 also contributes to RGC survival and enlarged neural size. In contrast, 4E-BP1 inhibits axon regeneration but increases surviving RGCs. We speculate that unknown downstream effectors of mTORC1 also contribute to axon regeneration. (B) Constitutively active Rheb activates mTORC1, which in turn phosphorylates the two downstream effectors S6K1 and 4E-BP1. Phosphorylation of S6K1 supports RGC survival, whereas phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 plays a contrary role. However, S6K1 activation seems to be dominating in this context, and the impact of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is masked and compensated by the positive effect of active S6K1. (C) Overexpression of non-phosphorylatable 4E-BP1 (4E-BP1-4A) protects RGCs independent of mTORC1 activity. Thus, inactivation of endogenous 4E-BP1 upon caRheb becomes irrelevant, and 4E-BP1-4A compensates for the low level of endogenous 4E-BP1 activity and further promotes RGC survival under these conditions. 4E-BP1: mTORC1 downstream effector; caRheb: constitutively active Rheb; GTP: guanosine triphosphate; mTORC1: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; Rheb: Ras homolog enriched in brain; S6K1: mTORC1 downstream effector; WT: wild type.

Rheb displays a neuroprotective effect through activating mTORC1. α-RGCs are a subtype of RGCs with high endogenous mTOR activity and display a high survival rate after injury (Duan et al., 2015). Thus, we speculate that gene delivery of caRheb significantly increases pS6 levels in RGCs and preferentially saves non-α-RGCs with low endogenous mTOR activity, and the constitutive activation of the mTOR pathway by caRheb increases the resistance of susceptible RGC subtypes to damage. Rheb/mTORC1 activation also promoted robust axon regeneration during the post-acute and chronic phases following axotomy and improved visual dysfunction. The downstream effectors of mTORC1, S6K1 and 4E-BP1 were identified as key factors involved in axon regeneration as DN-S6K1 and 4E-BP1-4A significantly compromised the axon regeneration.

While both inhibition of S6K1 and constitutively active 4E-BP1 antagonized caRheb-induced axonal regeneration, constitutively active S6K1, but not 4E-BP1 knockdown, induced axon regeneration. We speculate that the difference may be from the impact of S6K1 on cytoskeleton assembly and therefore growth cone machinery. Polymerization of microtubules is important for growth cone response to guidance cues and improves axon growth in the CNS (Sengottuvel and Fischer, 2011). Regulating cytoskeletal protein assembly is critical for promoting long-distance axon regeneration (Xi et al., 2019). PI3K-mTOR-S6K signals increase the local translation of collapsing response mediator protein 2 (CRMP2) in CNS neurons (Morita and Sobue, 2009; Huang et al., 2016; Na et al., 2017). CRMP2, a partner of the tubulin heterodimer, regulates axonal growth through binding to tubulin heterodimers and promotes microtubule assembly (Fukata et al., 2002). Activation of CRMP2 by GSK knockout or overexpression of CRMP2T/A promoted RGC axon regeneration following ONC in vivo and neurite outgrowth in primary RGCs in vitro (Leibinger et al., 2017). S6K also increases the axonal translation of Tau, which plays a role in regulating microtubule dynamics and induces polarity in cultured hippocampal neurons (Morita and Sobue, 2009). However, 4E-BP1 inhibition affects axonal regeneration primarily by initiating cap-dependent translation, which may not support long-distance axonal regeneration because of the deficits of neural polarity and the inhibitory environment of the mammalian CNS (Williams et al., 2020).

Here, we found that caS6K1 promotes axon regeneration and acted additively with caRheb to promote axon regeneration. Previous studies showed a dual effect of S6K1 on axon regeneration. The transgene-mediated expression of a constitutively active S6K fully recovered the developmental regrowth defect of Drosophila mushroom body γ-neurons within TORLL04239 MARCM clones (Yaniv et al., 2012). PI3K-mTOR-S6K signaling enhanced neuronal viability against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity and promoted neuronal growth in cultured hippocampal HT-22 cells (Na et al., 2017). Constitutively active S6K(T389E) induced axon elongation and neuronal polarization even in the presence of rapamycin in cultured rat hippocampal neurons (Morita and Sobue, 2009). However, an opposite role of S6K1 in axon regeneration was also reported, as the selective S6K1 inhibitor PF-4708671 stimulated corticospinal tract regeneration across a dorsal spinal hemisection by relieving the negative feedback-mediated inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway (Magnuson et al., 2012; Al-Ali et al., 2017). We hypothesized that the constitutively active S6K1-induced axon regeneration of RGCs is the combined effect of weakened PI3K-Akt-dependent axon regeneration and enhanced S6K1-dependent regeneration, with the latter playing a dominant role in this context.

In this study, we found that activation of Rheb together with S6K1 inactivation still resulted in considerable numbers of regenerating axons, while no axon regeneration was found after 4E-BP1 inhibition. This result suggested that in addition to S6K1 and 4E-BP1, other undefined factors may also contribute to caRheb-induced axon regeneration (Figure 9A). These factors and how they affect axon regeneration remain unknown. Upon activation, phosphorylated 4E-BP1 releases from eIF4E and enables translation initiation (Gingras et al., 1999). In this study, overexpression of the constitutively active 4E-BP1 (4E-BP1-4A) completely abolished the axon regeneration mediated by caRheb, indicating the necessity of 4E-BP1 inhibition for axon regeneration, most likely through its downstream translational targets or unknown mechanisms.

Our findings indicate that S6K1 and 4E-BP1 play different roles in RGC survival. Phosphorylated S6K1 is involved in promoting RGC survival, whereas phosphorylated 4E-BP1 plays a contrary role. S6K1 may promote cell survival through modulation of Bcl-2 associated death promoter (BAD), a “BH3 domain-only” proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family (Saito et al., 2012; Song et al., 2014). Overexpressing constitutively active 4E-BP1 is beneficial for neural survival after injury, which is supported by our data as well as a variety of studies. For example, a Drosophila ortholog of mammalian 4E-BP1 robustly suppressed the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and attenuated motor phenotypes in Drosophila Parkinson’s disease models (Tain et al., 2009). Primary hippocampal neurons overexpressing 4E-BP1 were neuroprotective against Parkinson’s disease-linked toxins through activating mitochondrial unfolded protein responses and reducing α-synuclein aggregation (Dastidar et al., 2020). Additionally, 4E-BP1 acts downstream of LRRK2, and the G2019S mutation in LRRK2 leads to a significant increase in 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, which is associated with Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis (Imai et al., 2008). However, 4E-BPs knockout resulted in a slight but significant neuroprotective effect in RGCs (Yang et al., 2014), which seems to contradict our results. We hypothesize that this difference is from the non-RGC-specific knockout of 4E-BPs, which may affect the survival of RGCs from the effects on other retinal cells. In this study, we used AAV-mediated gene transfer to specifically modulate 4E-BP1 levels in RGCs, which excluded any interference from non-RGCs.

mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 promotes RGC survival, whereas the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 plays a contrary role. We thus suggest that caRheb improves RGC survival through the combined effect of the opposing actions of the two downstream effectors, with S6K1 activation appearing to be dominant in this context (Figure 9B). Inactivation of endogenous 4E-BP1 upon caRheb expression can be compensated by exogenous 4E-BP1-4A overexpression and further promote RGC survival. Through modulation of the antagonistic effectors by co-expressing caRheb and 4E-BP1-4A, we observed an enhanced neuroprotection effect, suggesting that S6K1 and 4E-BP1 may promote RGC survival through different pathways (Figure 9C). Notably, 4E-BP1 compromises caRheb-induced regeneration but enhances RGC survival, indicating that the mechanisms regulating neural regeneration and survival are not the same.

Our results also showed that rapamycin significantly decreased but did not fully abolish the neuroprotective role of caRheb (Additional Figure 4B (221.6KB, tif) ), suggesting that Rheb-mediated mTOR-independent pathways may also be involved in the neuroprotective effects of caRheb. Previous research also showed that activation of mTOR also promotes neuron survival through indirect mechanisms. Gene delivery of Rheb(S16H) to adult hippocampus neurons increased the expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor through the interaction between neurons and astrocytes (Jeon et al., 2020; Moon et al., 2020; Yun et al., 2020). The siRNA-mediated knockdown of the mTOR inhibitor RTP801 promoted RGC survival and neurite outgrowth in retinal cultures partially through potentiated production of growth factors in astrocytes such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor, and neurotrophin-3 (Morgan-Warren et al., 2016). A recent study also showed that Rheb(C180S), a mutant form of Rheb that is unable to activate mTORC1, also promoted axonal elongation in primary hippocampal neurons and embryonic neurons (Choi et al., 2019), suggesting that Rheb-mediated mTOR-independent pathways also assist in promoting axon regeneration but may not be sufficient to induce axon regeneration alone in vivo.

This study has several limitations. First, AAV-mediated gene therapy is limited in improving acute injury when applied after injury because the AAV-mediated transfection usually takes at least 2 weeks and RGC loss occurs at the early stage of injury, which limits its clinical application. Second, we used only one model of RGC damage and optic nerve injury. Further study is required to verify the effectiveness of Rheb gene therapy on other models. Third, we used only male mice, which may create a potential bias.

In summary, our results provide evidence that Rheb has robust neuroprotective effects, including the promotion of RGC survival and axon regeneration in ONC, through manipulating the activity of S6K1 and 4E-BP1. Phosphorylated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 participated in axon regeneration, whereas they exerted different effects on RGC survival. Our study provides a novel strategy for neuroprotection through targeting Rheb and its downstream effectors.

Additional files:

Additional Figure 1 (475.2KB, tif) : The p-S6 levels in RGCs decrease earlier than the RGCs numbers following ONC.

The p-S6 levels in RGCs decrease earlier than the RGCs numbers following ONC.

(A) Optic nerve crush decreases survival RGCs and p-S6 expression. Fluorescent photomicrographs of retinal whole-mounts labeling for p-S6 (red, Alexa Fluor 555) or Tuj1 (green, Alexa Fluor 647) from naïve, 5, 7, 14, and 21dpc eyes. Scale bar: 60 µm. (B) Quantification of surviving Tuj1+ RGCs from naïve, 5, 7, 14, and 21 dpc eyes. (C) Percentage p-S6+ RGCs in from naïve, 5, 7, 14, and 21 dpc eyes. Data are presented as mean percentages of p-S6+ Tuj1+ cells among total Tuj1+ cells of each retina. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 4-5 per group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's post hoc test). dpc: Days post crush; ONC: optic nerve crush; p-S6: phospho-S6 ribosomal protein; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

Additional Figure 2 (672.6KB, tif) : Injection of AAV-transgene-FLAG/GFP achieves high transgenic efficiency in vivo.

Injection of AAV-transgene-FLAG/GFP achieves high transgenic efficiency in vivo.

Both AAV-EGFP and AAV-caRheb show high transfected efficiency in RGCs. Transduction of RGCs with AAV-GFP and AAV-caRheb-FLAG in C57BL/6J mice without ONC. Immunofluorescence labeling for DAPI (blue), GFP/FLAG (green, Alexa Fluor 555), and RBPMS (violet, Alexa Fluor 647) shows that transgene expression is identifiable within RGCs. Scale bars: 40 µm. AAV: Adeno-associated virus; DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2'-phenylindole; GFP: green fluorescent protein; RBPMS: RNA binding protein with multiple splicing; RGC: retinal ganglion cell.

Additional Figure 3 (405.6KB, tif) : Transfection of AAV-EGFP and AAV-caRheb do not affect the RGC survival.

Transfection of AAV-EGFP and AAV-caRheb do not affect the RGC survival.

(A) Transfection of caRheb increases p-S6 expression and does not affect the RGC numbers. Fluorescent photomicrographs of retinal whole-mounts labeling for Tuj1 (green, Alexa Fluor 647), and p-S6 (red, Alexa Fluor 555) from Naïve, AAV-EGFP, and AAV-caRheb groups 14 days post transfection. Scale bars: 60 µm. (B) Quantification of Tuj1+ RGCs from naïve, AAV-EGFP, and AAV-caRheb groups 14 days post transfection. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 4), and were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's post hoc test). AAV: adeno-associated virus; caRheb: constitutively active Ras homolog enriched in brain; EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein; p-S6: phospho-S6 ribosomal protein; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

Additional Figure 4 (221.6KB, tif) : Rapamycin attenuates caRheb-mediated neuroprotection.

Rapamycin attenuates caRheb-mediated neuroprotection.

(A) Rapamycin decreases the RGC numbers. Fluorescent photomicrographs of retinal whole-mounts labeling for Tuj1 (green, Alexa Fluor 647) from AAV-caRheb 14 dpc, AAV-caRheb + rapamycin 14 dpc, and vehicle only 14 dpc groups. Scale bar: 60 µm. (B) Quantification of Tuj1+ RGCs from AAV-caRheb 14 dpc, AAV-caRheb + rapamycin 14 dpc, and vehicle only 14 dpc groups. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 5-7). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's post hoc test). AAV: adeno-associated virus; caRheb: constitutively active Ras homolog enriched in brain; dpc: days post crush; ONC: optic nerve crush; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

Additional Figure 5 (880.1KB, tif) : Injection of AAV-transgene-HA achieves high transgenic efficiency in vivo.

Injection of AAV-transgene-HA achieves high transgenic efficiency in vivo.

AAV-transgene-HA achieves high transgenic efficiency in RGCs. Transduction of RGCs with AAV-caS6K1-HA, AAV-DN-S6K1-HA, AAV-sh4E-BP1-HA, and AAV-4E-BP1-4A-HA in C57BL/6J mice without ONC. Immunofluorescence labeling for HA (red, Alexa Fluor 555), and Tuj1 (green, Alexa Fluor 647) shows that transgene expression is identifiable within RGCs. Scale bars: 40 µm. 4E-BP1: mTORC1 downstream effector; AAV: adeno-associated virus; caS6K1: constitutively active S6K1; DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2'-phenylindole; DN-S6K1: dominate negative S6K1; HA: hemagglutinin; RGC: retinal ganglion cell; S6K1: mTORC1 downstream effector; Tuj1: β3-tubulin.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 82070967, 81770930, and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, No. 2020jj4788 (all to BJ).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article and uploaded as Additional files.

Editor’s evaluation: This is a well-conducted study to evaluate the neuroprotective and neuroregenerative effects of AAV-2-mediated Rheb overexpression after optic nerve crush in C57BL/6J mice. The authors used different recombinant AAV-2 vectors encoding different gene constructs, including constitutively active Rheb and its downstream target genes, namely constitutively active S6K1, dominant negative S6K1 and dominant negative 4E-BP1, to convincingly demonstrate the ability of Rheb to promote regeneration of optic nerve axons and neuroprotection of RGCs.

C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editors: Yu J, Li CH; L-Editors: Yu J, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Al-Ali H, Ding Y, Slepak T, Wu W, Sun Y, Martinez Y, Xu XM, Lemmon VP, Bixby JL. The mTOR substrate S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) is a negative regulator of axon regeneration and a potential drug target for central nervous system injury. J Neurosci. 2017;37:7079–7095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0931-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angarola B, Ferguson SM. Weak membrane interactions allow Rheb to activate mTORC1 signaling without major lysosome enrichment. Mol Biol Cell. 2019;30:2750–2760. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E19-03-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Sahra I, Manning BD. mTORC1 signaling and the metabolic control of cell growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;45:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron EG, Xia X, Galvao J, Ashouri M, Kapiloff MS, Goldberg JL. Optic nerve crush in mice to study retinal ganglion cell survival and regeneration. Bio Protoc. 2020;10:e3559. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi S, Sadra A, Kang J, Ryu JR, Kim JH, Sun W, Huh SO. Farnesylation-defective Rheb increases axonal length independently of mTORC1 activity in embryonic primary neurons. Exp Neurobiol. 2019;28:172–182. doi: 10.5607/en.2019.28.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2009;61:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniel S, Clark AF, McDowell CM. Subtype-specific response of retinal ganglion cells to optic nerve crush. Cell Death Discov. 2018;4:7. doi: 10.1038/s41420-018-0069-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dastidar SG, Pham MT, Mitchell MB, Yeom SG, Jordan S, Chang A, Sopher BL, La Spada AR. 4E-BP1 protects neurons from misfolded protein stress and Parkinson's disease toxicity by inducing the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. J Neurosci. 2020;40:8734–8745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0940-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demetriades C, Doumpas N, Teleman AA. Regulation of TORC1 in response to amino acid starvation via lysosomal recruitment of TSC2. Cell. 2014;156:786–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan X, Qiao M, Bei F, Kim IJ, He Z, Sanes JR. Subtype-specific regeneration of retinal ganglion cells following axotomy:effects of osteopontin and mTOR signaling. Neuron. 2015;85:1244–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson SM. Beyond indigestion:emerging roles for lysosome-based signaling in human disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;35:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukata Y, Itoh TJ, Kimura T, Ménager C, Nishimura T, Shiromizu T, Watanabe H, Inagaki N, Iwamatsu A, Hotani H, Kaibuchi K. CRMP-2 binds to tubulin heterodimers to promote microtubule assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:583–591. doi: 10.1038/ncb825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors:effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg JL, Klassen MP, Hua Y, Barres BA. Amacrine-signaled loss of intrinsic axon growth ability by retinal ganglion cells. Science. 2002;296:1860–1864. doi: 10.1126/science.1068428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groenewoud MJ, Zwartkruis FJ. Rheb and Rags come together at the lysosome to activate mTORC1. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:951–955. doi: 10.1042/BST20130037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo X, Snider WD, Chen B. GSK3βregulates AKT-induced central nervous system axon regeneration via an eIF2Bε-dependent, mTORC1-independent pathway. Elife. 2016;5:e11903. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo X, Zhou J, Starr C, Mohns EJ, Li Y, Chen EP, Yoon Y, Kellner CP, Tanaka K, Wang H, Liu W, Pasquale LR, Demb JB, Crair MC, Chen B. Preservation of vision after CaMKII-mediated protection of retinal ganglion cells. Cell. 2021;184:4299–4314.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell. 2005;123:569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Y, Park KK, Yang L, Wei X, Yang Q, Cho KS, Thielen P, Lee AH, Cartoni R, Glimcher LH, Chen DF, He Z. Differential effects of unfolded protein response pathways on axon injury-induced death of retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2012;73:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang H, Miao L, Yang L, Liang F, Wang Q, Zhuang P, Sun Y, Hu Y. AKT-dependent and -independent pathways mediate PTEN deletion-induced CNS axon regeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2019a;10:203. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1289-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang W, Wang C, Xie L, Wang X, Zhang L, Chen C, Jiang B. Traditional two-dimensional mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are better than spheroid MSCs on promoting retinal ganglion cells survival and axon regeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2019b;185:107699. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang WC, Chen Y, Page DT. Hyperconnectivity of prefrontal cortex to amygdala projections in a mouse model of macrocephaly/autism syndrome. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13421. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibad RT, Quenech'du N, Prochiantz A, Moya KL. OTX2 stimulates adult retinal ganglion cell regeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17:690–696. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.320989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikenoue T, Hong S, Inoki K. Monitoring mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:165–180. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai Y, Gehrke S, Wang HQ, Takahashi R, Hasegawa K, Oota E, Lu B. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP by LRRK2 affects the maintenance of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2008;27:2432–2443. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005;37:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jefferies HB, Fumagalli S, Dennis PB, Reinhard C, Pearson RB, Thomas G. Rapamycin suppresses 5'TOP mRNA translation through inhibition of p70s6k. EMBO J. 1997;16:3693–3704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeon MT, Nam JH, Shin WH, Leem E, Jeong KH, Jung UJ, Bae YS, Jin YH, Kholodilov N, Burke RE, Lee SG, Jin BK, Kim SR. In vivo AAV1 transduction with hRheb(S16H) protects hippocampal neurons by BDNF production. Mol Ther. 2015;23:445–455. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeon MT, Moon GJ, Kim S, Choi M, Oh YS, Kim DW, Kim HJ, Lee KJ, Choe Y, Ha CM, Jang IS, Nakamura M, McLean C, Chung WS, Shin WH, Lee SG, Kim SR. Neurotrophic interactions between neurons and astrocytes following AAV1-Rheb(S16H) transduction in the hippocampus in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:668–686. doi: 10.1111/bph.14882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong KH, Nam JH, Jin BK, Kim SR. Activation of CNTF/CNTFRαsignaling pathway by hRheb(S16H) transduction of dopaminergic neurons in vivo. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalesnykas G, Oglesby EN, Zack DJ, Cone FE, Steinhart MR, Tian J, Pease ME, Quigley HA. Retinal ganglion cell morphology after optic nerve crush and experimental glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3847–3857. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SR, Kareva T, Yarygina O, Kholodilov N, Burke RE. AAV transduction of dopamine neurons with constitutively active Rheb protects from neurodegeneration and mediates axon regrowth. Mol Ther. 2012;20:275–286. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SR, Chen X, Oo TF, Kareva T, Yarygina O, Wang C, During M, Kholodilov N, Burke RE. Dopaminergic pathway reconstruction by Akt/Rheb-induced axon regeneration. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:110–120. doi: 10.1002/ana.22383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kole C, Brommer B, Nakaya N, Sengupta M, Bonet-Ponce L, Zhao T, Wang C, Li W, He Z, Tomarev S. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) Protects retinal ganglion cells and promotes functional preservation after optic nerve crush. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61:31. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.2.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar V, Zhang MX, Swank MW, Kunz J, Wu GY. Regulation of dendritic morphogenesis by Ras-PI3K-Akt-mTOR and Ras-MAPK signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11288–11299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2284-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leibinger M, Andreadaki A, Golla R, Levin E, Hilla AM, Diekmann H, Fischer D. Boosting CNS axon regeneration by harnessing antagonistic effects of GSK3 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E5454–5463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621225114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levin LA, Gordon LK. Retinal ganglion cell disorders:types and treatments. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002;21:465–484. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li HJ, Pan YB, Sun ZL, Sun YY, Yang XT, Feng DF. Inhibition of miR-21 ameliorates excessive astrocyte activation and promotes axon regeneration following optic nerve crush. Neuropharmacology. 2018;137:33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Andereggen L, Yuki K, Omura K, Yin Y, Gilbert HY, Erdogan B, Asdourian MS, Shrock C, de Lima S, Apfel UP, Zhuo Y, Hershfinkel M, Lippard SJ, Rosenberg PA, Benowitz L. Mobile zinc increases rapidly in the retina after optic nerve injury and regulates ganglion cell survival and optic nerve regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E209–E218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616811114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YH, Werner H, Püschel AW. Rheb and mTOR regulate neuronal polarity through Rap1B. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33784–33792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802431200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang JJ, Liu YF, Ng TK, Xu CY, Zhang M, Pang CP, Cen LP. Peritoneal macrophages attenuate retinal ganglion cell survival and neurite outgrowth. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:1121–1126. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.300462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magnuson B, Ekim B, Fingar DC. Regulation and function of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) within mTOR signalling networks. Biochem J. 2012;441:1–21. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002;10:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miao L, Yang L, Huang H, Liang F, Ling C, Hu Y. mTORC1 is necessary but mTORC2 and GSK3βare inhibitory for AKT3-induced axon regeneration in the central nervous system. Elife. 2016;5:e14908. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moon GJ, Shin M, Kim SR. Upregulation of neuronal Rheb(S16H) for hippocampal protection in the adult brain. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2023. doi: 10.3390/ijms21062023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgan-Warren PJ, O'Neill J, de Cogan F, Spivak I, Ashush H, Kalinski H, Ahmed Z, Berry M, Feinstein E, Scott RA, Logan A. siRNA-mediated knockdown of the mTOR inhibitor RTP801 promotes retinal ganglion cell survival and axon elongation by direct and indirect mechanisms. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:429–443. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morita T, Sobue K. Specification of neuronal polarity regulated by local translation of CRMP2 and Tau via the mTOR-p70S6K pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27734–27745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Na EJ, Nam HY, Park J, Chung MA, Woo HA, Kim HJ. PI3K-mTOR-S6K signaling mediates neuronal viability via collapsin response mediator protein-2 expression. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:288. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nam JH, Leem E, Jeon MT, Jeong KH, Park JW, Jung UJ, Kholodilov N, Burke RE, Jin BK, Kim SR. Induction of GDNF and BDNF by hRheb(S16H) transduction of SNpc neurons:neuroprotective mechanisms of hRheb(S16H) in a model of Parkinson's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51:487–499. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8729-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nie D, Di Nardo A, Han JM, Baharanyi H, Kramvis I, Huynh T, Dabora S, Codeluppi S, Pandolfi PP, Pasquale EB, Sahin M. Tsc2-Rheb signaling regulates EphA-mediated axon guidance. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:163–172. doi: 10.1038/nn.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pang JJ, Lauramore A, Deng WT, Li Q, Doyle TJ, Chiodo V, Li J, Hauswirth WW. Comparative analysis of in vivo and in vitro AAV vector transduction in the neonatal mouse retina:effects of serotype and site of administration. Vision Res. 2008;48:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park KK, Liu K, Hu Y, Smith PD, Wang C, Cai B, Xu B, Connolly L, Kramvis I, Sahin M, He Z. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the PTEN/mTOR pathway. Science. 2008;322:963–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1161566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:658–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raught B, Peiretti F, Gingras AC, Livingstone M, Shahbazian D, Mayeur GL, Polakiewicz RD, Sonenberg N, Hershey JW. Phosphorylation of eucaryotic translation initiation factor 4B Ser422 is modulated by S6 kinases. EMBO J. 2004;23:1761–1769. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saito Y, Tanaka Y, Aita Y, Ishii KA, Ikeda T, Isobe K, Kawakami Y, Shimano H, Hara H, Takekoshi K. Sunitinib induces apoptosis in pheochromocytoma tumor cells by inhibiting VEGFR2/Akt/mTOR/S6K1 pathways through modulation of Bcl-2 and BAD. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E615–625. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00035.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanes JR, Masland RH. The types of retinal ganglion cells:current status and implications for neuronal classification. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:221–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-034120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwab ME, Bartholdi D. Degeneration and regeneration of axons in the lesioned spinal cord. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:319–370. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sengottuvel V, Fischer D. Facilitating axon regeneration in the injured CNS by microtubules stabilization. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:391–393. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.4.15552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shu Q, Xu Y, Zhuang H, Fan J, Sun Z, Zhang M, Xu G. Ras homolog enriched in the brain is linked to retinal ganglion cell apoptosis after light injury in rats. J Mol Neurosci. 2014;54:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0281-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Song X, Dilly AK, Kim SY, Choudry HA, Lee YJ. Rapamycin-enhanced mitomycin C-induced apoptotic death is mediated through the S6K1-Bad-Bak pathway in peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1281. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tain LS, Mortiboys H, Tao RN, Ziviani E, Bandmann O, Whitworth AJ. Rapamycin activation of 4E-BP prevents parkinsonian dopaminergic neuron loss. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1129–1135. doi: 10.1038/nn.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tavazoie SF, Alvarez VA, Ridenour DA, Kwiatkowski DJ, Sabatini BL. Regulation of neuronal morphology and function by the tumor suppressors Tsc1 and Tsc2. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1727–1734. doi: 10.1038/nn1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thoreen CC, Chantranupong L, Keys HR, Wang T, Gray NS, Sabatini DM. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature. 2012;485:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]