Abstract

Although there are challenges in treating traumatic central nervous system diseases, mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) have recently proven to be a promising non-cellular therapy. We comprehensively evaluated the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in traumatic central nervous system diseases in this meta-analysis based on preclinical studies. Our meta-analysis was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42022327904, May 24, 2022). To fully retrieve the most relevant articles, the following databases were thoroughly searched: PubMed, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, and Ovid-Embase (up to April 1, 2022). The included studies were preclinical studies of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for traumatic central nervous system diseases. The Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE)’s risk of bias tool was used to examine the risk of publication bias in animal studies. After screening 2347 studies, 60 studies were included in this study. A meta-analysis was conducted for spinal cord injury (n = 52) and traumatic brain injury (n = 8). The results indicated that mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles treatment prominently promoted motor function recovery in spinal cord injury animals, including rat Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan locomotor rating scale scores (standardized mean difference [SMD]: 2.36, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.96–2.76, P < 0.01, I2 = 71%) and mouse Basso Mouse Scale scores (SMD = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.57–3.04, P = 0.01, I2 = 60%) compared with controls. Further, mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles treatment significantly promoted neurological recovery in traumatic brain injury animals, including the modified Neurological Severity Score (SMD = –4.48, 95% CI: –6.12 to –2.84, P < 0.01, I2 = 79%) and Foot Fault Test (SMD = –3.26, 95% CI: –4.09 to –2.42, P = 0.28, I2 = 21%) compared with controls. Subgroup analyses showed that characteristics may be related to the therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. For Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan locomotor rating scale scores, the efficacy of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles was higher than that of xenogeneic mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (allogeneic: SMD = 2.54, 95% CI: 2.05–3.02, P = 0.0116, I2 = 65.5%; xenogeneic: SMD: 1.78, 95%CI: 1.1–2.45, P = 0.0116, I2 = 74.6%). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles separated by ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with density gradient ultracentrifugation (SMD = 3.58, 95% CI: 2.62–4.53, P < 0.0001, I2 = 31%) may be more effective than other EV isolation methods. For mouse Basso Mouse Scale scores, placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles worked better than bone mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (placenta: SMD = 5.25, 95% CI: 2.45–8.06, P = 0.0421, I2 = 0%; bone marrow: SMD = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.23–2.41, P = 0.0421, I2 = 0%). For modified Neurological Severity Score, bone marrow-derived MSC-EVs worked better than adipose-derived MSC-EVs (bone marrow: SMD = –4.86, 95% CI: –6.66 to –3.06, P = 0.0306, I2 = 81%; adipose: SMD = –2.37, 95% CI: –3.73 to –1.01, P = 0.0306, I2 = 0%). Intravenous administration (SMD = –5.47, 95% CI: –6.98 to –3.97, P = 0.0002, I2 = 53.3%) and dose of administration equal to 100 μg (SMD = –5.47, 95% CI: –6.98 to –3.97, P < 0.0001, I2 = 53.3%) showed better results than other administration routes and doses. The heterogeneity of studies was small, and sensitivity analysis also indicated stable results. Last, the methodological quality of all trials was mostly satisfactory. In conclusion, in the treatment of traumatic central nervous system diseases, mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles may play a crucial role in promoting motor function recovery.

Key Words: animals, central nervous system diseases, extracellular vesicles, mesenchymal stromal cell, meta-analysis, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

The central nervous system includes the spinal cord and brain, and traumatic central nervous system diseases mainly refer to spinal cord injury (SCI) and traumatic brain injury (TBI), which are increasingly recognized as global health priorities (Maas et al., 2008; Ahuja et al., 2017a). TBI is often characterized by mental decline, hearing and vision loss, hemiplegia, and even coma and other related symptoms (Andriessen et al., 2011). SCI can cause paraplegia below the innervated plane (Ahuja et al., 2017b). These injuries not only lead to reduced quality of life for the affected individuals and their families but also become a burden to society due to productivity losses and high health care costs (Young et al., 2019). Current treatments for SCI include early surgical decompression (Ramakonar and Fehlings, 2021), glucocorticoid pulse therapy (Bracken et al., 1997), and neurotrophic drug therapy (Hurlbert et al., 2013). For TBI, the treatments include rehabilitation training and pharmacological support (Nelson et al., 2019). However, none of these treatments can improve the patient’s neurological recovery to a great extent (Maas et al., 1999). Therefore, new therapeutic approaches are urgently needed to prevent or slow down the progression of secondary injury in traumatic central nervous system diseases.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been widely studied as a therapeutic option for traumatic central nervous system diseases (Tetzlaff et al., 2011; Harrop et al., 2012; Hachem et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). However, when cell transplantation is applied in clinical studies, tumorigenicity and immune rejection become obstacles to its clinical application (Liu et al., 2021b). It has been shown that the significant efficacy of MSCs is attributable to the extracellular vesicles (EVs) they secrete (Pinho et al., 2020; Yari et al., 2022). Extracellular vesicles are intercellular communication tools, which are divided into several subtypes: apoptotic bodies, ectosomes or shedding microvesicles, and exosomes (Colombo et al., 2014; Kalra et al., 2016). Exosomes are small EVs originating from the endosomes and measuring 40–150 nm. Ectosomes or shedding microvesicles are large EVs with a diameter between 100 and 1000 nm, and are secreted by the plasma membrane. Apoptotic cells release heterogeneous EVs, called apoptotic bodies, with a diameter of 50–5000 nm. These vesicles partially overlap in size. Therefore, there are great challenges in the separation of pure EV subtypes (Lotvall et al., 2014). A number of comprehensive reviews regarding the different sources, contents, and functions of these types of vesicles are available (Théry et al., 2018; van Niel et al., 2018; Jeppesen et al., 2019). EVs contain various RNAs and proteins that play an anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and neuroprotective roles in traumatic central nervous system disease therapy (Li et al., 2020b; Yang et al., 2022). They can not only replace the damaged cells but also compensate for the disadvantages of cell therapy, such as low immunogenicity and the role of crossing the blood-brain barrier (Théry et al., 2002).

Although EVs have received much attention, there are still a number of issues that need to be addressed regarding this cell-free therapy. A conference on EVs has presented existing relevant questions and solutions (Théry et al., 2018). However, there is no consensus on the method of EV isolation, the source of cells, EV subtypes, and the maximum benefit from the dosing regimen. An omnidirectional and systematic grasp of these experimental approaches and the efficacy of MSC-EVs for traumatic central nervous system diseases are needed for the preclinical studies to clinical translation. Hence, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent animal model studies that used MSC-EVs for traumatic central nervous system diseases. We also performed subgroup analyses based on MSC origin, EV isolation methods, subtypes, and dosage regimen. Last, we performed a bias risk assessment and a sensitivity analysis to assess the stability of the results.

Methods

The protocol for this study was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (registeration No. CRD42022327904) on May 24, 2022.

Search strategy

To fully retrieve most of the articles, the following databases were retrieved: PubMed, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, and Ovid-Embase (up to April 1, 2022). References were also reviewed for relevance and manual studies of included articles. Only the articles were limited to English-language publications were considered. Comprehensive information on the search strategy is provided in Additional file 1 (89.8KB, pdf) .

Data extraction

The types of literature were screened by two investigators (the first and second authors ZY and ZY) following the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any differences were settled through consultation; otherwise a third party (the corresponding author CC) was consulted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The eligibility criteria were strictly formulated in accordance with Population Intervention Comparison Outcome Study design (PICOS) principles.

Study subjects: We included all animal studies of traumatic central nervous system diseases and excluded other invertebrates and in vitro studies.

Interventions: We included all studies of MSC-EVs for traumatic central nervous system diseases and excluded those of other cell-derived EVs.

Comparisons: All comparison groups were considered, including those treated with phosphate buffer saline, untreated groups, and negative controls.

Outcomes: The outcome measures were the Foot Fault Test and the modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS), which could be used to evaluate neurological function in animals with TBI. Further, the Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan (BBB) locomotor rating scale and Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) scores were used to assess hindlimb motor function in rats and mice with SCI, respectively.

Studies: We included controlled intervention studies (randomized or non-randomized), whereas reviews, comments, letters, and unpublished studies were excluded.

Data collection and bias risk evaluation

The data were independently collected and cross-checked by two professional researchers (the authors ZY and ZL) from the screened studies. Any disagreement was resolved through consultation with the third party (the corresponding author CC). The data extracted: (a) study characteristics: author, year, country, the sample size of each group, animal, sex, weight, TBI and SCI models, MSC source, immunocompatibility, EV isolation and size/morphology analysis, EV positive markers, EV negative markers, dosage regimen (time, dosage, number of doses, and route); and (b) outcomes: mNSS, Foot Fault Test, BBB, and BMS. The quality of the studies included by the two researchers was analyzed using the SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool (https://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/14/43) (Hooijmans et al., 2014) for animal studies, including attrition bias, performance bias, reporting bias, selection bias, detection bias, and other considerations from a list of 10 entries.

Outcome measurements

Neurological assessment in animals with TBI included the mNSS and the Foot Fault Test. BBB and BMS were used as outcome measures to determine hindlimb motor function in rats and mice with SCI, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Each outcome was analyzed with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes using the standardized mean difference (SMD). The I2 test was used to evaluate statistical heterogeneity. This test exhibits remarkable heterogeneity when I2 values exceed 50%, and in these cases, a random-effects model was used; otherwise, a fixed effects model was used. The results were summarized graphically using forest plots. We assessed the stability of the results by performing sensitivity analysis using the exclusion method. Meta-analysis was performed with the R software (version 4.1.3; Boston, MA, USA). A P-value of 0.05 was set to determine statistical significance. The funnel plots and Egger’s regression test were used to evaluate publication bias. Planned subgroup analyses included animal-based characteristics (e.g., sex and model); intervention characteristics (e.g., tissue source of MSCs, EV subtype, EV isolation methods, and immunocompatibility); and dosing regimen (time, dose, and route).

Results

Literature retrieval

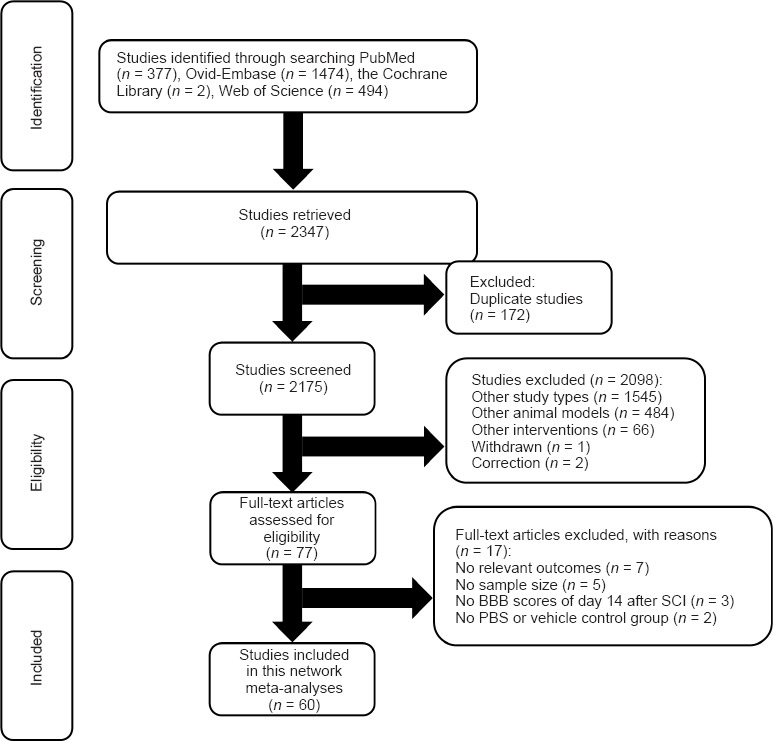

A total of 2347 studies were initially identified after a systematic search of PubMed, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, and Ovid-Embase databases. Subsequently, 172 replicate studies were excluded. A total of 2098 studies were deleted after screening the title and abstract, and the reasons for exclusion are presented in Figure 1. Then, we carefully searched the full text of the remaining 77 studies for evaluation. Subsequently, 17 studies were excluded for various reasons (Figure 1). Finally, 60 studies were included in this study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of article selection process.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 60 included studies (Zhang et al., 2015, 2017, 2020a, b, 2021a, b, c; Huang et al., 2017, 2020a, b, 2021a, b, 2022; Kim et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018, 2019, 2020a, 2021; Ruppert et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018, 2021a, b; Guo et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019, 2020, 2021a; Lu et al., 2019; Ni et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019, 2021, 2022; Chen et al., 2020, 2021; Gu et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021a, b, c; Jiang and Zhang, 2021; Luo et al., 2021; Mu et al., 2021; Nakazaki et al., 2021; Nie and Jiang, 2021; Romanelli et al., 2021; Sheng et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2021; Xin et al., 2021; Zhai et al., 2021; Han et al., 2022; Kang and Guo, 2022; Liang et al., 2022) are summarized in Additional Table 1. The majority of the studies were performed in China (n = 52), with five studies in the United States, two studies in Korea, and one study in Australia. The sample size in each group ranged from 5 to 24. Most studies used rat models (n = 50), with only 10 studies using mouse models. The majority were male animals (n = 36), with 20 studies using female animals. However, four studies did not describe the sex of the animals. Rats weighed 80–300 g, and mice weighed 17–35 g; the age range was between 2 and 14 weeks. All TBI (n = 8) used the CCI compression models, and SCI (n = 52) models include contusion, compression, hemisection, and transection. The majority of the studies used MSCs derived from the bone marrow (n = 42), a portion from the placenta (n = 10), and a small portion from fat (n = 5) and umbilical cord (n = 3). The origin of these stromal cells was both allogeneic (n = 34) and xenogeneic (n = 23). However, some studies did not provide this information (n = 3). EVs were isolated by ultracentrifugation (n = 32), isolation kit (n = 13), density gradient ultracentrifugation (n = 2) continuous extrusion, density gradient ultracentrifugation and magnetic sorting (n = 1), continuous filtration (n = 1), ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with ultracentrifugation (n = 4), ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with density gradient ultracentrifugation (n = 4), tangential flow filtration and ultracentrifugation (n = 1), ultracentrifugation, ultrafiltration and molecular exclusion chromatography (n = 1), polyethylene glycol and ultracentrifugation (n = 1). Fortunately, most studies (n = 56) took two or three approaches to EV identification according to the mid-September 2018 guidelines (Théry et al., 2018). However, there were four studies that took only one approach. Importantly, negative markers were not used to demonstrate specific isolation of EVs in many studies (n = 38), and only some studies (n = 22) reported negative markers. MSC-EVs were administered intravenously (n = 49), intrathecally (n = 10), intracerebroventricularly (n = 1), retroorbitally (n = 1), and intranasally (n = 1). Most studies (n = 41) delayed dosing after injury, and some studies (n = 18) dosed immediately after the injury. However, one study did not describe the time of dosing. Most studies (n = 23) used doses of MSC-EVs ≥ 100 μg protein, with 19 studies administering doses equal to 100 μg and 11 studies administering doses ≤ 100 μg. However, three studies did not use protein quantification, but EV particle number quantification, and four studies did not describe the dose. There were 41 studies with single dosing and 16 studies with multiple dosing. Three studies did not describe the number of doses.

Additional Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Studies | Country | The sample size of each group | Animal | Sex | Weight | TBI and SCI model | MSC source | Immunocompatibilit y | EV isolation and size/morphology analysis | EV positive markers | EV negative markers | Dosage regimen (time, dosage, the number of doses, and route) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al., 2015 | USA | 1.TBI + exosomes (n=8) 2.TBI + PBS (n=8) 3.sham (n=8) |

Adult Wistar rats | Male | 325 ± 11g (2-3 months old) | CCI: a 6-mm-diameter tip at a rate of 4 m/s and 2.5 mm of compression |

Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | ExoQuick exosome isolation kit; 40-120 nm (TEM); 116 ± 49 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | Alix | Not described | 24 h after TBI; 100ug; 1 dose; Intravenous | mNSS, Foot Fault Test |

| Zhang et al., 2017 | USA | 1.TBI+ exosomes from hMSCs in 3D culture (Exo-3D) (n=8) 2.TBI + exosomes from hMSCs in 2D culture (Exo-2D) (n=8) 3.TBI + liposomes (Lipo) (n=8) 4.Sham (n=8) |

Adult Wistar rats | Male | 317 ± 10 g (2-3 months old) | CCI: a 6-mm-diameter tip at a rate of 4 m/s and 2.5 mm of compression |

Human bone marrow | Xenogeneic | ExoQuick exosome isolation kit; Not described | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 24 h after TBI; 100ug; 1 dose; Intravenous | mNSS, Foot Fault Test |

| Ni et al., 2019 | China | 1.TBI + Exosomes (n=7) 2.TBI + PBS (n=7) 3.Sham (n=7) |

C57BL/6J mice | Male | 12-14 weeks old | CCI: a velocity of 4 m/s and a dwell time of 150 ms and a deformation depth of 1.0 mm using a 3-mm-diameter impactor tip | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-100 nm (TEM); 110.4 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD63 and TSG101 | Cytochrome c | 15 min after TBI; 30ug; 1 dose; Retro-orbital injection | mNSS |

| Yang et al., 2019 | China | 1.TBI + MiR-124 Enriched Exosomes (n=6) 2.TBI (n=6) 3.Sham + MiR-124 Enriched Exosomes (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

SD rats | Male | 250–300 g (8– 10 weeks old) | CCI: a velocity of 3 m/s and a dwell time of 100 ms and a deformation depth of 1.5 mm using a 3-mm-diameter impactor tip | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | ExoQuick exosome isolation kit; 40-100 nm (TEM); 77.1 ± 19.5 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 24 h after TBI; 100ug; 1 dose; Intravenous | mNSS |

| Chen et al., 2020 | China | 1.TBI + hADSC (n=8) 2.TBI + exosomes (n=8) 3.TBI + PBS (n=8) 4.Sham (n=8) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 300 ± 11 g (6-8 weeks) | CCI: a 25-g weight fall from a height of 20 cm | Human adipose tissue | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 40-100 nm (TEM) (small EVs) | CD63 and HSP70 | Not described | 24 h after TBI; 20ug; 1 dose; Contralateral intracerebroventricular | mNSS, Foot Fault Test |

| Xu et al., 2020 | China | 1.TBI + BDNF-induced MSCs-Exo (n=6) 2.TBI + MSCs-Exo (n=6) 3.TBI + PBS (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 220–250 g | CCI: a velocity of 4.0 m/s and a dwell time of 200 ms and a deformation depth of 2.5 mm |

Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-150 nm (TEM); 110 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | Not described | 24 h after TBI; 100ug; 1 dose; Intravenous | mNSS |

| Zhang et al., 2020b | China | 1.TBI + 200 μg exosomes (n=8) 2.TBI + 100 μg exosomes (n=8) 3.TBI + 50 μg exosomes (n=8) 4.TBI + PBS (n=8) 5.Sham (n=8) |

Adult Wistar rats | Male | 339.2 ± 13.6 g (3 months) | CCI: a 6-mm-diameter tip at a rate of 4 m/s and 2.5 mm of compression |

Human bone marrow | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 200 nm (TEM); 122 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | Alix and Hsp70 | β-actin | 1,4, or 7 days after TBI; 50,100, or 200 ug; 3 doses; Intravenous | mNSS, Foot Fault Test |

| Zhang et al., 2021c | China | 1.TBI + MiR-17-92 enriched exosomes (n=8) 2.TBI + exosomes (n=8) 3.TBI + PBS (n=8) 4.Sham (n=8) |

Young Wistar rats | Male | 2–3 months | CCI: a 6-mm-diameter tip at a rate of 4 m/s and 2.5 mm of compression |

Human bone marrow | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 200 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | Alix and Hsp70 | β-actin | 24 h after TBI; 100ug; 1 dose; Intravenous | mNSS, Foot Fault Test |

| Huang et al., 2017 | China | 1.SCI + MSC-exosomes (n=5) 2.SCI + PBS (n=5) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 180–220 g | T10, moderate contusion injury: a modified Allen’s weight drop apparatus (8 g weight at a vertical height of 40 mm, 8 g×40 mm) | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 20-130 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 1.5 h after SCI; 100 μg (1 × 10^10 particles); 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Kim et al., 2018 | Korea | 1.SCI + iron oxide nanoparticle (IONP)– incorporated exosome in the presence of a magnet (n=10) 2.SCI + iron oxide nanoparticle (IONP)– incorporated exosome in the absence of a magnet (n=10) 3.SCI + exosome (n=10) 4.SCI + PBS (n=10) 5.Sham (n=10) |

C57BL/6 mice | Not described | 20-25 g (8 weeks) | T10-T11, compression injury: a 20 G metal impounder was then gently placed on T10-T11 dura for 1 min | Human bone marrow | Xenogeneic | Serial extrusion, density-gradient ultracentrifugation, and magnetic sorting; TEM,NTA; 151.4 ± 32.5 nm (NV) and 158.7 ± 40.7 nm (NV-IONP) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | Not described | 1 h after SCI; 40 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BMS |

| Li et al., 2018 | China | 1.SCI + miR-133b exosomes (n=6) 2.SCI + miR-con exosomes (n=6) 3.SCI + PBS (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 250-300 g | T10, compression injury: an aneurysm clip of 35 g closing force for 60 s | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | ExoQuick exosome isolation kit; Not described | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 24 h after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Ruppert et al., 2018 | United States | 1.SCI + MSC-EVs (n=16) 2.SCI + vehicle (n=6) 3.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 225-250 g | T10, moderate contusion injury: Infinite Horizon Impactor (150 kdynes of force with 1 s dwell) | Human bone marrow | Xenogeneic | Sequential filtration; 75-165 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, CD81, HSP70, and LAMP-1 | Not described | 3 h after SCI; 1 × 10^9 particles; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Sun et al., 2018 | China | 1.SCI + 200μg exosomes (n=8) 2.SCI + 20μg exosomes (n=8) 3.SCI + PBS (n=8) |

C57BL/6 mice 4 Sham (n=8) |

Female | 17–22 g (7-8 weeks) | T11, contusion injury: a 10 g rod dropped at a height of 6.25 mm | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with ultracentrifugation; 70 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | β-tubulin and LaminA | 30 min after SCI; 20 μg or 200 μ g respectively; 1 dose; Intravenous | BMS |

| Wang et al., 2018 | China | 1.SCI + MSC-exosomes (n=10) 2.SCI + MSC (n=10) 3.SCI + PBS (n=10) 4 Sham (n=10) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 200-250 g | T10, contusion injury: Infinite Horizon Impactor (200 kilodyne) | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 30 min after SCI; 40 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Guo et al., 2019 | United States | 1.SCI + ExoPTEN (IN) (n=7) 2.SCI + Exosome (IN) (n=10) 3.SCI + ExoPTEN (IL) (n=4) 4.SCI + PTEN-siRNA (IL) (n=3) 5.SCI + PBS (n=15) IL: intralesional; IN: intranasal. |

Adult SD rats | Female | 200-250 g | T10, complete transection injury: microscissor | Human bone marrow | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 111±64 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD81 | Calnexin | Intranasal treatment: 40 μl(40.43 ×10^8 particles/ml); 2-3 h after SCI, and every 24 h, for 5 days; 5 doses Intralesional treatment: 40 μ l(40.43×10^8 particles/ml); immediately after SCI; 1 dose | BBB |

| Kang et al., 2019 | China | 1.SCI + exosomes isolated from MSCs transfected with PTEN siRNA (n=3) 2.SCI + exosomes isolated from MSCs transfected with miR-21 (n=3) 3.SCI + exosomes isolated from MSCs transfected with a scramble control (n=3) 4.Sham (n=3) |

Adult SD rats | Not described | 200 ± 20 g | T9/10, contusion injury: a 2-mm impactor (with a 10 g weight) was quickly dropped from a 25 mm height | Rat bone marrow | Ultracentrifugation; 40-110 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | Yes | CD9 and CD81 | Not described | immediately after SCI; not described; intravenous injection; Allogeneic | BBB |

| Li et al., 2019 | China | 1.SCI + BMSCs-Exos (n=10) 2.SCI + PBS (n=10) 3.Sham (n=10) |

Adult Wistar rats | Male | 150-200 g | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g metal weight was dropped from a height of 5 cm | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; TEM | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 200 μ g/dose, 1 dose every 3 days until the 27th day after SCI; Intravenous | BBB |

| Liu et al., 2019 | China | 1.SCI + Exosomes (n=10) 2.SCI + PBS (n=10) |

SD rats | Female | 170-220 g | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod (2.5 mm in diameter) dropped from a height of 12.5 mm. | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Density-gradient ultracentrifugation; 20-150 nm (TEM,DLS) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Lu et al., 2019 | China | 1.SCI + BMSC-EV (n=10) 2.SCI + EV-free CM (n=10) 3.SCI + PBS (n=10) 4.Sham (n=10) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 200-250 g | T10, contusion injury: Infinite Horizon Impactor (200 kilodyne) | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; TEM (EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 30 min after SCI; 40 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Yu et al., 2019 | China | 1.SCI + miRNA-29b exosomes (n=20) 2.SCI + miR NC BMSCs (n=20) 3.SCI + miRNA-29b BMSCs |

Adult SD rats | Female | 230-250 g | T10, contusion injury: a striking force of 2 N | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | ExoQuick exosome isolation kit; Not described | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 1 h after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| (n=20) | |||||||||||||

| 4.SCI + exosomes (n=20) | |||||||||||||

| 5.SCI (n=20) | |||||||||||||

| Zhao et al., 2019 | China | 1.SCI + BMSCs-Exo (n=5) 2.SCI + PBS (n=5) 3.Sham (n=5) |

Adult Wistar rats | Male | 200-250 g | T10, hemisection injury: an iris knife | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | QEV kit; 20-130 nm (TEM) (small EVs) | CD9 and TSG101 | Calnexin | 1 h after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Zhou et al., 2019 | China | 1.SCI + MSCs-EVs which were transfected with the miR-21-5p inhibitor (n=6) 2.SCI + MSCs-EVs which were transfected with the miR-21-5p inhibitor-NC (n=6) 3.SCI + MSCs-EVs (n=6) 4.SCI + PBS (n=6) 5.Sham (n=6) |

Adult Wistar rats | Male | 200-250 g | T10, hemisection injury: an iris knife | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | EVs isolation kit; 40-160 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and TSG101 | Calnexin | 1 h after SCI; 100 μg(1 × 10^10 particles); 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Gu et al., 2020 | China | 1.SCI + BMSCs-Exo (n=8) 2.SCI + PBS (n=8) 3.Sham (n=8) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 220-260 g | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod (2.5 mm in diameter) dropped from a height of 12.5 mm | Bone marrow | Not described | Ultrafiltration-centrifugation combined with ultracentrifugation; 30-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Calnexin | 1 h after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Huang et al., 2020b | China | 1.SCI + EVs (n=8) 2.SCI + Saline (n=8) 3.SCI (n=8) 4.Sham (n=8) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 180-220 g | T10, moderate contusion injury: a modified Allen’s weight drop apparatus (8 g weight at a vertical height of 40 mm, 8 g×40 mm) | Human epidural fat | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 60-130 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Huang et al., 2020a | China | 1.SCI + miR-126 Ex (n=10) 2.SCI + miR-con Ex (n=10) 3.SCI + PBS (n=10) 4.Sham (n=10) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 180-220 g | T10, moderate contusion injury: a modified Allen’s weight drop apparatus (8 g weight at a vertical height of 40 mm, 8 g×40 mm) | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-120 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | 30 min after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Lee et al., 2020 | Korea | 1.SCI + MF-NV (n=8) 2.SCI + N-NV (n=8) 3.SCI + PBS (n=8) 4.Sham (n=8) |

C57BL/6 mice | Female | 20–25 g (6-8 weeks) | T10, compression injury: a stainless steel impounder (weight: 20 g) was loaded to the T10 spinal cord for 30 sec | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Serial extrusion; N-NVs: 238.3±82.2 nm, MF-NVs: 233.5±70.3 nm (TEM,NTA) (small and large EVs) | CD9 | Not described | 1 h and 7 days after SCI; 25 μ g/dose; 2 doses; Intravenous | BMS |

| Li et al., 2020a | China | 1.SCI + Exo-pGel (n=8) 2.SCI + Exo-IV (n=8) 3.SCI + pGel (n=8) 4.SCI + PBS (n=8) 5.Sham (n=8) |

Adult SD rats | Female | 220-250 g | T10, transection injury: a long-span lesion of 4.0 ± 0.5 mm | Human placenta | Xenogeneic | Size-exclusion chromatography and ultracentrifugation; 40-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Liu et al., 2020 | China | 1.SCI + HExo (n=8) 2.SCI + Exos (n=8) 3.SCI + PBS (n=8) |

C57BL/6 mice | Male | 6–8 weeks old | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod dropped from a height of 6.5 cm | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultrafiltration-centrifugation combined with density-gradient ultracentrifugation; 50-150 nm (TEM), normoxic: 121.6 nm, hypoxic: 125.3 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, CD81, and TSG101 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BMS |

| Zhang et al., 2020a | China | 1.SCI + hPMSCs-Exos (n=6) 2.SCI + PBS (n=6) |

C57BL/6 mice | Male | 8 weeks old | T10, contusion injury: a modified Allen’s weight drop apparatus (8 g weight at a vertical height of 40 mm) | Human placenta | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-200 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intrathecheal | BMS |

| Chang et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + B-Exo (n=12) 2.SCI + PBS (n=12) 3.Sham (n=12) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 220-260 g | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod (2.5 mm in diameter) dropped from a height of 125mm | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultrafiltration-centrifugation combined with density-gradient ultracentrifugation; 30-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | TSG101 and CD63 | Calnexin | 1 h after SCI; 4 μg; 1 dose; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Chen et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + miR-26a exosomes (n=6) 2.SCI + exosomes (n=6) 3.SCI + PBS (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 6–8 weeks old | T10, compression injury: an aneurysm clip of 75 g closing force for 30 s | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 50-100 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and Flotillin-1 | Calnexin | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Cheng et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + GelMA-Exos (n=5) 2.SCI + Exos (n=5) 3.SCI + PBS (n=5) 4.Sham (n=5) |

Adult SD rats | Not described | Not described | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod dropped from a height of 25 mm | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | Not described; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Fan et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + BMSCs-Exo (n=6) 2.SCI + PBS (n=6) 3.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 200-250 g | T10, contusion injury: NYU Impactor (10g×25mm) | Bone marrow | Not described | Exosome extraction kit; Not described | CD9, CD63, CD81, Alix, and TSG101 | Not described | 7 consecutive days after SCI; 200 μL/dose; 7 doses; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Huang et al., 2021b | China | 1.SCI + Exo-miR-494 (n=6) 2.SCI + Exo-miR-con (n=6) 3.SCI + PBS (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

SD rats | Male | 80-100 g (2 weeks) | T10, contusion injury: spinal cord injury percussion apparatus (The weight of the metal rod reached 25 g, and the height was 50 mm) | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Exosome isolation kit; 30-200 nm (TEM), 150 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | Not described | per 24 h for 7 consecutive days after SCI; 100 μg/dose; 7 doses; Intravenous | BBB |

| Huang et al., 2021a | China | 1.SCI + Exo-siRNA (n=6) 2.SCI + Exo (n=6) 3.SCI + siRNA (n=6) 4.SCI + PBS (n=6) 5 Sham (n=6) |

SD rats | Female | 200–250 g (10 weeks old) | T10, contusion injury: metal rod weight of 30 g and height of 50 mm | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultrafiltration-centrifugation combined with ultracentrifugation; 30-200 nm (TEM), 150 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | Calnexin | per 24 h for 5 consecutive days after SCI; 100 μg/dose; 5 doses; Intravenous | BBB |

| Jia et al., 2021a | China | 1.SCI + MSC-EVs-miR-381 mimic+oe-WNT5A (n=8) 2.SCI + MSC-EVs-miR-381 mimic+oe-BRD4 (n=8) 3.SCI + MSC-EVs-miR-381 mimic+oe NC (n=8) 4.SCI + MSC-EVs-NC mimic+oe-NC (n=8) |

SD rats | Male | 180-205 g (6 -8 weeks) | T9, compression injury: a mosquito clamp for one minute | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-120 nm (TEM,DLS) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | GM130 | 3 days after SCI; Not described; intravenous injection; Allogeneic | BBB |

| Jia et al., 2021b | China | 1.SCI + Shh-Exo (n=5) 2.SCI + Exo (n=5) 3.SCI + PBS (n=5) 4.Sham (n=5) |

SD rats | Male | 230–250 g | T10, contusion injury: a striking device was then used to apply a 2 N striking | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Exo Quick-TC kit; TEM (Not described) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | 1 h after SCI, one dose every other day; 40 μg/dose; 3 doses; Intravenous | BBB |

| Jia et al., 2021c | China | 1.SCI + Exo/sh-Shh (n=5) 2.SCI + Exo/sh-NC (n=5) 3.SCI + Exo (n=5) 4.SCI + PBS (n=5) 5.Sham (n=5) |

SD rats | Male | 230–250 g | T10, contusion injury: a striking device was then used to apply a 2 N striking | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Exo Quick-TC kit; TEM (Not described) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | 1 h after SCI, one dose every other day; 40 μg/dose; 3 doses; Intravenous | BBB |

| Jiang and Zhang, 2021 | China | 1.SCI + EX-miR-145-5p (n=3) 2.SCI + EX-miR-NC (n=3) 3.SCI + PBS (n=3) 4.SCI (n=3) 5.Sham (n=3) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 200 ± 20 g (7 weeks old) | T9/10, contusion injury: NYU | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; TEM,NTA (Not described) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | 30 min after SCI; 100 μg(1 × 10^10 particles); 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Li et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + EEM (n=5) 2.SCI + MQ (n=5) 3.SCI + PBS (n=5) 4.Sham (n=5) |

C57BL/6 mice | Female | 8 weeks old | T10, contusion injury: Infinite Horizon Impactor (50 kilodyne) | Mouse bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Actin | Immediately after SCI; Not described; Intrathecheal | BMS |

| Liu et al., 2021a | China | 1.SCI + shUSP29-MEVs (n=8) 2.SCI + shNC-MEVs (n=8) 3.SCI + MEVs (n=8) 4.SCI + EVs (n=8) 5.SCI + PBS (n=8) |

C57BL/6 mice | Not described | 6-8 weeks | T8, contusion injury: a spinal cord impactor (a 5 g rod dropped from a height of 6.5 cm) | Mouse bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 100 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, Alix, and TSG101 | Calnexin | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BMS |

| Luo et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + GIT1-BMSCs-Exos (n=10) 2.SCI + BMSCs-Exos (n=10) 3.SCI + PBS (n=10) |

SD rats | Female | 170-220 g (12 weeks) | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod (2.5 mm in diameter) dropped from a height of 12.5 mm | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultrafiltration-centrifugation combined with density-gradient ultracentrifugation; 50-150 nm (TEM,DLS) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Mu et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + FG-Exo (n=6) 2.SCI + FG (n=6) 3.SCI + PBS (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

SD rats | Female | 230 g | T10, transection injury: leaving a lesion gap of 4– 5 mm | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Ultrafiltration-centrifugation combined with ultracentrifugation; 100-200 nm (TEM), 150 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Nakazaki et al., 2021 | United States | 1.SCI + MSC-derived sEVs delivered in three fractionated doses over 3 days (n=14) 2.SCI + MSC-derived sEVs delivered in a single dose (n=14) 3.SCI + MSCs (n=14) 4.SCI + Vehicle (n=17) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 185-215 g | T9, contusion injury: a delivery of 22.5 Newton impact (equal to 225 kilodynes) with a 2.5 mm tip using the Infinite Horizon (IH) impactor |

Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-100 nm (TEM); 83.0 ± 14.1 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD63, CD9, and Alix | Not described | 7 days after SCI; 4.6 ± 0.5 μg (2.5 × 10^9 particles)/dose; one-dose or fractioned dose (On 7, 8 and 9 days after SCI); Intravenous | BBB |

| Nie and Jiang, 2021 | China | 1.SCI + EVs (n=24) 2.SCI + GW (n=24) 3.SCI + PBS (n=24) 4.Sham (n=24) |

SD rats | Male | 180–220 g | T10, transection injury: microsurgical scissors | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 50-150 nm (TEM,qNano) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Calnexin | 24 h after SCI; 100 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Romanelli et al., 2021 | Austria | 1.SCI + EVs(Intravenous) (n=5) 2.SCI + Evs(Intrathecheal) (n=5) 3.SCI + Vehicle(Intrathecheal) (n=5) 4.Sham (n=5) |

F344-rats | Female | 140–190 g (10 –12 weeks) | T8, contusion injury: Infinite Horizon Impactor (200 kilodyne, 1,000 μm of displacements) | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Tangential flow filtration (TFF) and ultracentrifugation; 125 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD81, and TSG101 | GM130 | Intrathecheal treatment: immediately after SCI; 2μl (2 × 10^9 particles); 1 dose Intravenous treatment: immediately after SCI; 100μl (2 × 10^9 particles); 1 dose | BBB |

| Sheng et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + Exos (n=5) 2.SCI + PBS (n=5) 3.Sham (n=5) |

C57BL/6 mice | Female | 8–10 weeks old | T10, contusion injury: an NYU impactor with a 5-g rod dropped from a height of 6 mm | Mouse bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 50-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intrathecheal | BMS |

| Wang et al., 2021a | China | 1.SCI + FE-EVs (n=8) 2.SCI + EVs (n=8) 3.SCI + FE (n=8) 4.SCI + PBS (n=8) 5.Sham (n=8) |

Rats | Female | 230 g | T10, transection injury: a microscissor | Human adipose tissue | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 50-200 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD63, CD81, Alix, and TSG101 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 1 μg; 1 dose; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Wang et al., 2021b | China | 1.SCI + Exo-K (n=10) 2.SCI + Exo (n=10) 3.SCI + PBS (n=10) 4.Sham (n=10) |

Adult SD rats | Female | 6–7 weeks old | T10, compression injury: an artery clamp (35 g 3 mm depth for 30s) | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Exosome extraction kit; 30-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | β-actin | 30 min and 24 h after SCI; 200 μ g/dose; 2 doses; Intravenous | BBB |

| Xiao et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + EVs (n=6) 2.SCI + GW (n=6) 3.SCI + PBS (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 150-200 g | T10, compression injury: an aneurysm clip for 60 s | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 30-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Grp94 | 24 h after SCI; 100 mg (2 × 10^9 particles/mL); 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Xin et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + siTIMP2-Exos (n=5) 2.SCI + Exos (n=5) 3.SCI + PBS (n=5) 4.Sham (n=5) |

Adult SD rats | Female | 220-250 g | T9, moderate contusion injury: an Infnite Horizon Impact Device(150 kdyn force with no dwell time) | Human bone marrow | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 50-150 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | Not described | Once a day for 1 week after SCI; 100 μg/dose; 7 doses; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Zhai et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + CD73+huc MSC-EVs (n=20) 2.SCI + hucMSC-EVs (n=20) 3.SCI + CD73 (n=20) 4.SCI + PBS (n=20) 5.Sham (n=20) |

ICR mice | Male | 30-35 g (6 weeks old) | T8-T9, contusion injury: a 10 g rod dropped at a height of 6.25 mm | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation, ultrafiltration, and size exclusion chromatography; hucMSC-EVs: 103.41±42.03 nm, CD73+hucMCS-EVs: 106.51±53.99 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, and ALIX | Calnexin | Once a day and for 10 days after SCI; 20 μg/dose; 10 doses; Intrathecheal | BMS |

| Zhang et al., 2021a | China | 1.SCI + LBMP (n=10) 2.SCI + LMP (n=10) 3.SCI + LM (n=10) 4.SCI + LP (n=10) 5.SCI (n=10) |

Adult SD rats | Female | 180-200 g | T10, transection injury: scissors (4 mm in length) | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 130.3 ± 3.3 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) |

CD81, TSG101, CD63, and TfR | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 100 μ g/dose; 1 dose; Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Zhang et al., 2021b | China | 1.SCI + Exo(181C)+PTEN (n=6) 2.SCI + Exo(181C) (n=6) 3.SCI + Exo (n=6) 4.SCI + PBS (n=6) 5.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 200–280 g (8 weeks) | T10, moderate contusion injury: a NYU-III weight drop apparatus (10 g weight at a vertical height of 12.5 mm, 10 g×12.5 mm) | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 99.02 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9 and CD63 | β-actin | 30 min after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Zhou et al., 2021 | China | 1.SCI + Exo (n=6) 2.SCI + PBS (n=6) |

SD rats | Female | 200–220 g (7-8 weeks) | T11, transection injury | Human placenta | Xenogeneic | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and ultracentrifugation; 100-200 nm (TEM) (small EVs) | TSG101 and CD63 | Not described | 1 h and 2 weeks after SCI; 25 μ g/dose; 2 doses; Intravenous | BBB |

| Han et al., 2022 | China | 1.SCI + BMSC EVs+ SB431542 day3-treated (n=10) 2.SCI + BMSC-EVs+ SB431542 day0-treated (n=10) 3.SCI + BMSC-EVs (n=10) 4.SCI + DMEM/F12 (n=10) |

Adult Wistar rats | Female | 200–250 g (6– 8 weeks old) | T10, contusion injury: Infinite Horizon Impactor | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; TEM,DLS (Not described) | CD9, CD63, and TSG101 | CD90 | Immediately after SCI; 72 μL (The medium in the pump was released at a rate of 1 μL/h, 3 consecutive days after SCI); Intrathecheal | BBB |

| Huang et al., 2022 | China | 1.SCI + Hyp-Evs-miR-511-3p mimic (n=10) 2.SCI + Hyp-EVs (n=10) 3.SCI + PBS (n=10) 4.Sham (n=10) |

SD rats | Not described | 200–220 g (8 weeks) | T10, contusion injury: a 5 g rod dropped at a height of 6.5 cm | Adipose tissue | Not described | Ultrafiltration-centrifugation combined with density-gradient ultracentrifugation; 80-120 nm (TEM) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, CD81, and TSG101 | Not described | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Kang and Guo, 2022 | China | 1.SCI + Exo (n=10) 2.SCI + PBS (n=10) 3.Sham (n=10) |

SD rats | Female | 170-220 g (8 weeks) | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod (2.5 mm in diameter) dropped from a height of 12.5 mm | Human umbilical cord | Xenogeneic | Exosome extraction kit; 50-100 nm (TEM),80-100 nm (NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | GAPDH | Immediately after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Liang et al., 2022 | China | 1.SCI + Hypo-exo (n=6) 2.SCI + Norm-exo (n=6) 3.SCI + PBS (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Female | 180-220 g | T10, contusion injury: a 10 g rod (2 mm in diameter) dropped from a height of 50 mm | Rat adipose tissue | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; normoxia: 127.2 nm, hypoxia: 123.5 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, CD81, and TSG101 | Not described | 24 h after SCI; 200 μg; 1 dose; Intravenous | BBB |

| Zhou et al., 2022 | China | 1.SCI + Exo (n=6) 2.SCI + PBS (n=6) 3.Exo (n=6) 4.Sham (n=6) |

Adult SD rats | Male | 200–250 g (3 months) | T10, contusion injury: Infinite Horizon Impactor (2N, equal to 200 kilodyne) | Rat bone marrow | Allogeneic | Ultracentrifugation; 100 nm (TEM,NTA) (small EVs) | CD9, CD63, and CD81 | Not described | 30 min and 24 h after SCI; 20 μ g/dose; 2 doses; Intravenous | BBB |

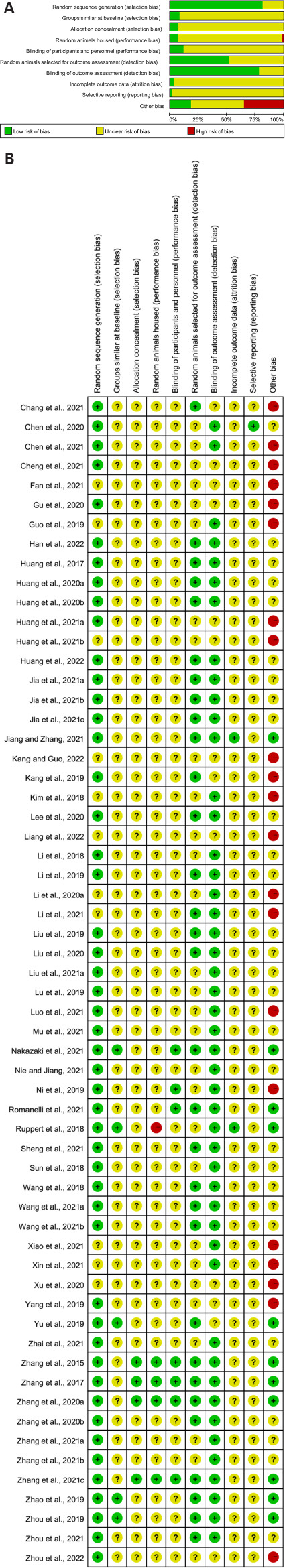

Methodological quality and risk of bias

The methodological quality assessment charts and summaries of all studies included in this meta-analysis are shown in Figure 2. For the overall risk of bias assessment, of all studies included, 21 (35%) were high risk, 10 (17%) were low risk, and 29 (48%) showed unclear risk. In addition, half of the randomly selected outcome assessments for detection bias of the included studies were low risk and half were ambiguous. Sequence generation risk of selection bias and detection bias blinding were low for most included studies. However, most of the included studies showed unclear risks in many items such as baseline characteristics of selection bias, selection bias allocation concealment, performance bias, incomplete outcome data for attrition bias, and selective outcomes for reporting bias. In conclusion, the methodological quality of all trials was mostly satisfactory.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias with the Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) tool.

(A) Risk of bias graph. (B) Risk of bias summary.

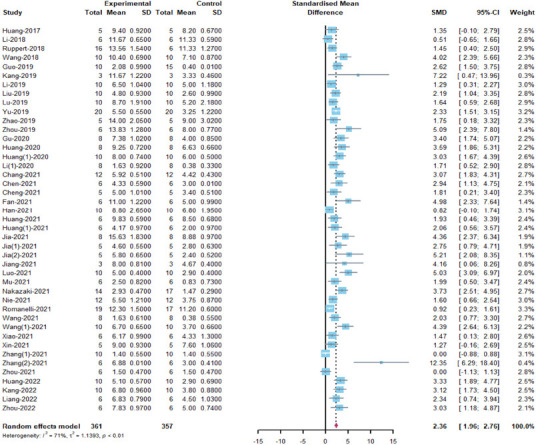

Effect of MSC-EVs on motor function recovery after SCI

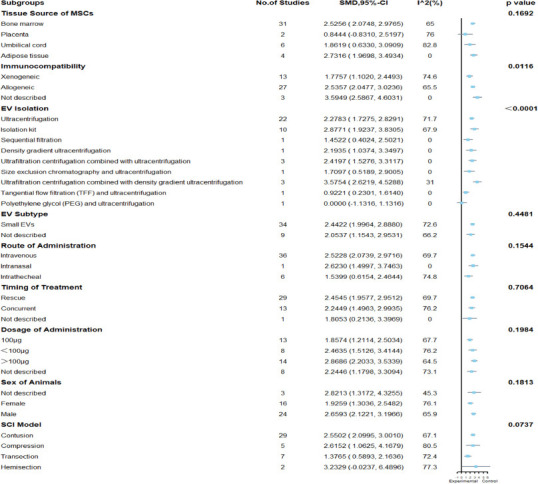

The BBB score of the rats: a total of 43 included articles (Huang et al., 2017, 2020a, b, 2021a, b, , 2022; Li et al., 2018, 2019, 2020a; Ruppert et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018, 2021a, b; Guo et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019, 2021, 2022; Gu et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021a, b, c; Jiang and Zhang, 2021; Luo et al., 2021; Mu et al., 2021; Nakazaki et al., 2021; Nie and Jiang, 2021; Romanelli et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2021; Xin et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021a, b; Han et al., 2022; Kang and Guo, 2022; Liang et al., 2022) were analyzed. The results indicated that MSC-EVs treatment significantly promoted motor function recovery in rats (SMD = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.96–2.76, P < 0.01, I2 = 71%; Figure 3). The results of subgroup analyses demonstrated that allogeneic MSC-EVs were more beneficial to motor function recovery than xenogeneic administration (allogeneic: SMD = 2.54, 95% CI: 2.05–3.02, I2 = 65.5%; xenogeneic: SMD = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.1–2.45, I2 = 74.6%, P = 0.0116). The EV isolation method (SMD = 3.58, 95% CI: 2.62–4.53, P < 0.0001, I2 = 31%) may be related to higher EV efficacy, as ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with density gradient ultrafiltration showed better results than other EV isolation methods (Figure 4). However, there were no differences in efficacy between the tissue source of MSC, EV subtype, route of administration, time administered, dose administered, animal’s sex, and SCI model (Figure 4). Although the study showed heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis indicated that the results were stable (Figure 1 and Additional Figure 1 (1.3MB, tif) ).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan locomotor rating scale scores.

References Wang 2021 and Wang (1) 2021 correspond to Wang et al., 2021a and Wang et al., 2021b in the reference list, respectively. References Zhang (1) 2021 and Zhang (2) 2021 correspond to Zhang et al., 2021a and Zhang et al., 2021b in the reference list.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan locomotor rating scale scores.

EV: Extracellular vesicle.

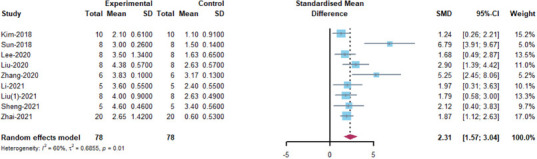

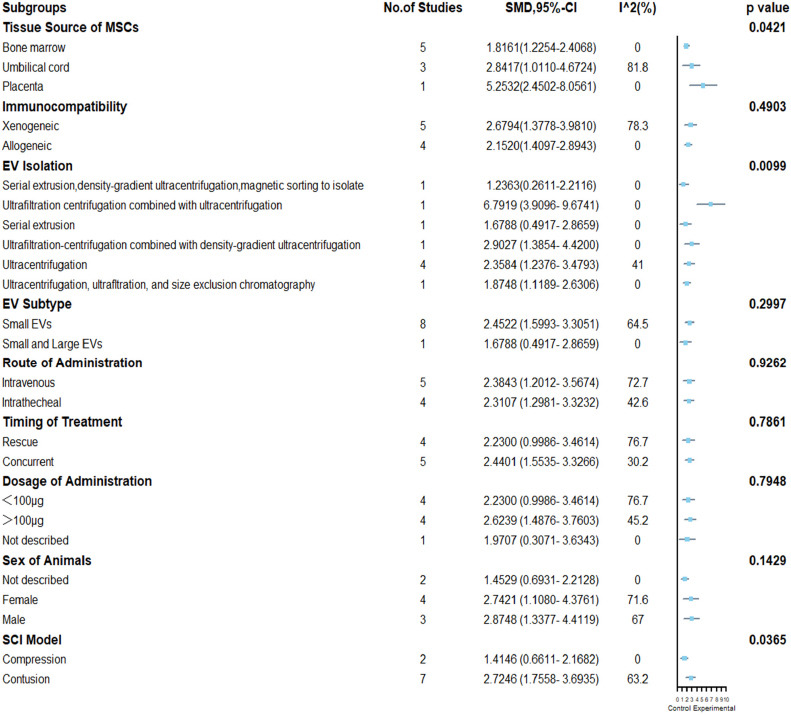

BMS score of the mice: nine included articles (Kim et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020, 2021a; Zhang et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2021; Sheng et al., 2021; Zhai et al., 2021) were analyzed. The results indicated that MSC-EVs treatment significantly promoted motor function recovery in mice (SMD = 2.31, 95%CI: 1.57–3.04, I2 = 60%, P = 0.01) (Figure 5). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that placenta-derived MSCs had stronger motor function recovery than bone marrow-derived MSC (placenta: SMD = 5.25, 95% CI: 2.45–8.06, I2 = 0%; bone marrow: SMD = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.23–2.41, I2 = 0%; P = 0.0421), but only one study involved placenta-derived MSCs. The EV isolation method (SMD = 6.79, 95% CI: 3.97–9.67, I2 = 0%, P = 0.0099) may be related to higher EV efficacy, as ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with ultrafiltration showed better results than other EV isolation methods (Figure 6). Finally, the efficacy of MSC-EVs in the spinal cord contusion model was better than the compression model (compression: SMD = 1.41, 95% CI: 0.66–2.17, I2 = 0%; contusion: SMD = 2.72, 95% CI: 1.76–3.69, I2 = 63.2%; P=0.0365). However, there were no differences in efficacy between the immunocompatibility of MSCs, EV subtype, route of administration, treatment time, dose administered, and animal’s sex (Figure 6). Despite heterogeneity between studies, sensitivity analysis indicated that the results were stable (Figure 2 and Additional Figure 2 (508.9KB, tif) ).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of the Basso Mouse Scale scores.

The reference Liu (1) 2021 correspond to Liu et al., 2021a in the reference list.

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis of Basso Mouse Scale scores.

EV: Extracellular vesicle; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

Effect of MSC-EVs on neurological recovery after TBI

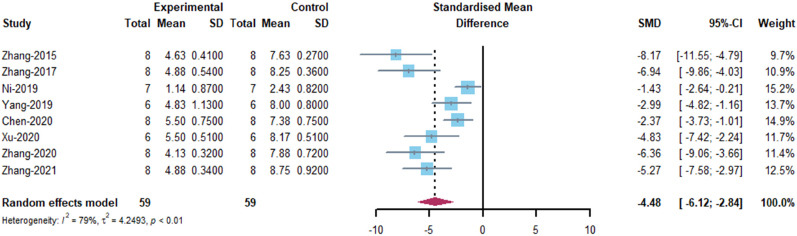

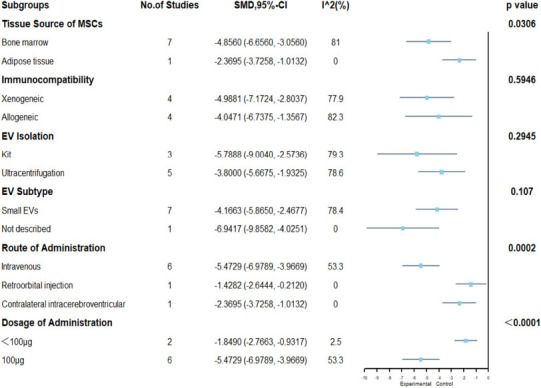

mNSS: eight included articles (Zhang et al., 2015, 2017, 2020a, 2021c; Ni et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020) were analyzed. The results indicated that MSC-EVs treatment significantly promoted neurological recovery in rats (SMD = –4.48, 95% CI: –6.12 to –2.84, I2 = 79%, P < 0.01; Figure 7). The results of subgroup analyses showed that bone marrow-derived MSCs showed a stronger recovery of neurological function than adipose-derived MSCs (bone marrow: SMD = –4.86, 95% CI: –6.66 to –3.06, I2 = 81%; adipose: SMD = –2.37, 95% CI: –3.73 to –1.01, I2 = 0%; P = 0.0306). Administration route (SMD = –5.47, 95% CI: –6.98 to –3.97, I2 = 53.3%, P = 0.0002) and dose (SMD = –5.47, 95% CI: –6.98 to –3.97, I2 = 53.3%, P < 0.0001) may be related to higher EV efficacy, as intravenous administration and dose of administration equal to 100 μg showed better results than other administration routes and doses (Figure 8). However, there were no differences in efficacy among the immunocompatibility of MSCs, EV isolation methods, and EV subtypes (Figure 8). Despite heterogeneity between studies, sensitivity analysis indicated that the results were stable (Figure 3 and).

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis of modified Neurological Severity Scores.

The references Zhang-2020 and Zhang-2021 correspond to Zhang et al., 2020a and Zhang et al., 2021c in the reference list, respectively.

Figure 8.

Subgroup analysis of modified Neurological Severity Scores.

EV: Extracellular vesicle; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

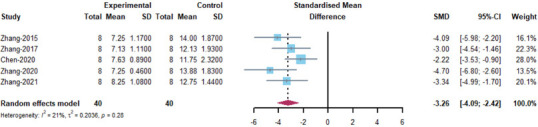

Foot Fault Test: five included articles (Zhang et al., 2015, 2017, 2020b, c; Chen et al., 2020) were analyzed. The results showed that MSC-EVs treatment significantly promoted neurological recovery in rats (SMD = –3.26, 95% CI: –4.09 to –2.42, I2 = 21%, P = 0.28; Figure 9). The results of subgroup analyses demonstrated that no efficacy differences were observed between the tissue origin, immunocompatibility, EV isolation method, EV subtype, route of administration, and dose of administration of MSCs (Figure 10). The heterogeneity of the studies was small, and sensitivity analysis also indicated stable results (Figure 4 and Additional Figure 4 (349.6KB, tif) ).

Figure 9.

Meta-analysis of Foot Fault Test results.

The references Zhang-2020 and Zhang-2021 correspond to Zhang et al., 2020a and Zhang et al., 2021c in the reference list, respectively.

Figure 10.

Subgroup analysis of Foot Fault Test results.

EV: Extracellular vesicle; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

Publication bias

We used Funnel plots and Egger’s regression test to evaluate publication bias (Figure 11). There was a significant publication bias in the funnel plot for visual inspection of rat BBB scores. Egger regression confirmed this result and also showed evidence of publication bias (Egger’s test: t = 6.27, df = 41, P < 0.0001). The absence of 16 articles on the left (unfilled circles) could have been predicted by pruning and filling analysis. Because the number of articles for the other outcome measures was ≤ 10, no publication bias assessment was performed for the other outcome measures.

Figure 11.

Assessment of publication bias in Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan locomotor rating scale scores.

(A) Funnel plots showed pronounced asymmetry. (B) Trim-and-fill analysis predicted 16 “missing” studies (unfilled circles). The dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Our systematic review comprehensively synthesizes the preclinical study design, methods, therapeutic effect, and preclinical reports of studies of MSC-EVs for traumatic central nervous system diseases. The results showed that MSC-EVs administration obviously promoted outcome measures of traumatic central nervous system diseases, as assessed by the BBB, BMS, mNSS, and Foot Fault tests. These findings show the therapeutic effect of MSC-EVs for traumatic central nervous system diseases by significantly improving motor recovery in animals with SCI and neurological recovery in animals with TBI.

Our meta-analysis systematically evaluated the efficacy of MSC-EVs for traumatic central nervous system diseases from various perspectives of experimental approaches. Given that the development of MSC-EVs therapies involves many variables, we performed a meta-analysis to evaluate relevant factors that may enhance the efficacy of EVs. In the study of SCI in rats, allogeneic administration of MSC-EVs may be more helpful for motor function recovery than xenogeneic administration, which may be because allogeneic administration of MSC-EVs has low immunogenicity and low immune rejection, thereby increasing their survival (van Balkom et al., 2019). In addition, EV obtained using ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with density gradient ultrafiltration may be associated with higher efficacy. Because the higher the purity of EV obtained by separation, the clearer the function, while a single separation method will likely produce many pollutants, which may have a negative impact on the function. A study has shown that the combination of 3D-cultured MSC and tangential flow filtration can obtain higher yield and purity of MSC-EVs (Haraszti et al., 2018). This shows that the combined separation method may be superior to the single separation method (Tieu et al., 2020), which was consistent with minimal information on extracellular vesicle studies (mid-September 2018).

In studies of SCI in mice, while only one study showed stronger motor recovery using placenta-derived MSC-EVs, it is well-known that the placenta is less likely to produce immune rejection. Because it is designated as biohazardous waste, it can be used as a non-invasive and rich source of stem cells (Hua et al., 2013). Therefore, easy availability of the placenta shows its ethical advantages when considering clinical translation. As in studies of SCI in rats, EVs obtained using ultrafiltration centrifugation combined with ultrafiltration may show better results than other EV isolation methods. Finally, MSC-EVs may be more effective in treating the SCI contusion model than the SCI compression model, possibly because contusion is the oldest and most commonly used method for SCI models (Sharif-Alhoseini et al., 2017), and the stability of the model can be controlled using parameterization to make the model more reproducible (Pearse et al., 2005). MSC-EVs have been shown to well inhibit the inflammatory response at the time of the cascade inflammatory response early in SCI, which may be related to its better efficacy in contusion models. The results in studies of TBI have shown that bone marrow-derived MSC-EVs showed stronger neurological recovery than other origins, which may be related to only one study of fat origin. However, it is difficult to obtain bone marrow-derived MSCs when it is used for clinical transformation (Kern et al., 2006). Therefore, it is important to choose the source of MSC-EVs. In addition, intravenous administration and the 100 μg dose showed better results, which shows that intravenous administration is safer, more controllable, and produces fewer side effects than other modalities. It also suggests that 100 μg may be the optimal dose at which EVs work and that a higher dosage is perhaps a burden for animals and is also more likely to produce toxicity or side effects. Some studies have shown that a single dose of EVs administered early can have a significant effect (Williams et al., 2020; Bambakidis et al., 2022). However, other studies have demonstrated that multiple doses of the same EVs are more effective than single doses (Nakazaki et al., 2021). Therefore, the dose and frequency of MSC-EVS administration still need to be further studied. Importantly, this study analyzed the quality of the included studies using the internationally accepted symbol animal study risk of bias tool. The methodological quality of all included studies was also satisfactory.

This meta-analysis has some limitations. First, the body weight of the rat was not considered. Second, in addition to studies of BBB scores in rats, the number of studies and sample size of other outcome indicators are very small, which may cause risk of bias. Third, these functional scores, using BBB, BMS, mNSS, and Foot Fault Tests as indicators for efficacy evaluation, are not comprehensive enough. It is remarkably subjective. Fourth, the funnel plot showed significant publication bias, which may be related to the fact that the included studies were preclinical studies. Last, most of the included studies showed unclear risks in many items. Only 17% of the studies had a low risk of bias, mainly because the studies we included and analyzed were preclinical studies (Begley and Ioannidis, 2015).

Preclinical studies of MSC-EVs are essential for their subsequent clinical application. A considerable number of articles have assessed the consequence of MSC-EVs in traumatic central nervous system diseases. However, no trial has directly compared the efficacy of different tissue- or cell-derived MSC-EVs in traumatic central nervous system diseases. This finding provides directions for future research. In addition, there is also no optimal parameter for the dose, route, and method of administration of MSC-EVs. Therefore, the optimal administration parameters of EVs should be the focus of future research. Most of the included studies demonstrated the effectiveness of EVs for traumatic central nervous system diseases. However, there is only one study on its safety (Huang et al., 2021a), which shows that MSC-EVs do not cause damage to the liver and lungs. Therefore, attention should be paid to the safety aspect of using MSC-EVs.

Conclusion

In the treatment of traumatic central nervous system diseases, MSC-EVs may play a crucial role in promoting motor function recovery. However, through comprehensive analysis of the experimental methods and EV parameters of the included studies, we believe that there is still some heterogeneity among the various studies that affect the results of the current study. Therefore, further standardization of preclinical trials is needed to promote clinical translation.

Additional files:

Additional file 1 (89.8KB, pdf) : Search query for databases.

Search query for databases

Additional Table 1: Characteristics of the included studies.

Additional Figure 1 (1.3MB, tif) : Sensitivity analysis of Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan locomotor rating scale scores.

Sensitivity analysis of Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan (BBB) locomotor rating scale scores.

Additional Figure 2 (508.9KB, tif) : Sensitivity analysis of mouse Basso Mouse Scale scores.

Sensitivity analysis of mouse Basso Mouse Scale scores.

Additional Figure 3 (427.6KB, tif) : Sensitivity analysis of modified Neurological Severity Score.

Sensitivity analysis of modified Neurological Severity Score.

Additional Figure 4 (349.6KB, tif) : Sensitivity analysis of Foot Fault Test results.

Sensitivity analysis of Foot Fault Test results.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None of the authors declare a conflict of interest.

Data availability statement: All relevant data are within the paper and its Additional files.

Editor’s evaluation: Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation has been widely studied as a treatment for central nervous system injury and diseases for decades, and MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs), a cell-free therapy is drawing more attention in fields recently. In this manuscript, the authors screened all the published papers on MSC-EVs for the therapy in traumatic central nervous system diseases. It’s very interesting that 60 studies were included according to the author’s standard. Furthermore, they concluded that MSC-EVs treatment significantly promoted motor function recovery and neurological recovery in spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury. Moreover, the authors concluded that placenta-derived MSC-EVs were more effective than bone marrow-derived MSC-EVs, intravenous administration and dose of administration equal to 100 μg had better effect. Therefore, MSC-EVs may play a significant role in improving motor function recovery in the treatment of traumatic central nervous system diseases. The novelty of the current study, which conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the benefits from the method of EVs isolation, the source of cells, EVs subtypes and dosing regimen, is to provide the foundation for future standardization of preclinical trials and clinical translation.

C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editor: Li CH; L-Editors: Li CH, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Ahuja CS, Wilson JR, Nori S, Kotter MRN, Druschel C, Curt A, Fehlings MG. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017a;3:17018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahuja CS, Nori S, Tetreault L, Wilson J, Kwon B, Harrop J, Choi D, Fehlings MG. Traumatic spinal cord injury-repair and regeneration. Neurosurgery. 2017b;80:S9–22. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andriessen TM, Horn J, Franschman G, van der Naalt J, Haitsma I, Jacobs B, Steyerberg EW, Vos PE. Epidemiology, severity classification, and outcome of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury:a prospective multicenter study. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:2019–2031. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bambakidis T, Dekker SE, Williams AM, Biesterveld BE, Bhatti UF, Liu B, Li Y, Pickell Z, Buller B, Alam HB. Early treatment with a single dose of mesenchymal stem cell derived extracellular vesicles modulates the brain transcriptome to create neuroprotective changes in a porcine model of traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2022;57:281–290. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begley CG, Ioannidis JP. Reproducibility in science:improving the standard for basic and preclinical research. Circ Res. 2015;116:116–126. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, Leo-Summers L, Aldrich EF, Fazl M, Fehlings M, Herr DL, Hitchon PW, Marshall LF, Nockels RP, Pascale V, Perot PL, Jr, Piepmeier J, Sonntag VK, Wagner F, Wilberger JE, Winn HR, Young W. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Randomized Controlled Trial. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. JAMA. 1997;277:1597–1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Q, Hao Y, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Zhuo H, Zhao G. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal microRNA-125a promotes M2 macrophage polarization in spinal cord injury by downregulating IRF5. Brain Res Bull. 2021;170:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Tian Z, He L, Liu C, Wang N, Rong L, Liu B. Exosomes derived from miR-26a-modified MSCs promote axonal regeneration via the PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway following spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:224. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Li J, Ma B, Li N, Wang S, Sun Z, Xue C, Han Q, Wei J, Zhao RC. MSC-derived exosomes promote recovery from traumatic brain injury via microglia/macrophages in rat. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:18274–18296. doi: 10.18632/aging.103692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng J, Chen Z, Liu C, Zhong M, Wang S, Sun Y, Wen H, Shu T. Bone mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome-loaded injectable hydrogel for minimally invasive treatment of spinal cord injury. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2021;16:1567–1579. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2021-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan L, Dong J, He X, Zhang C, Zhang T. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes reduce apoptosis and inflammatory response during spinal cord injury by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40:1612–1623. doi: 10.1177/09603271211003311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu J, Jin ZS, Wang CM, Yan XF, Mao YQ, Chen S. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes improves spinal cord function after injury in rats by activating autophagy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:1621–1631. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S237502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo S, Perets N, Betzer O, Ben-Shaul S, Sheinin A, Michaelevski I, Popovtzer R, Offen D, Levenberg S. Intranasal delivery of mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes loaded with phosphatase and tensin homolog siRNA repairs complete spinal cord injury. ACS Nano. 2019;13:10015–10028. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b01892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hachem LD, Ahuja CS, Fehlings MG. Assessment and management of acute spinal cord injury:From point of injury to rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40:665–675. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2017.1329076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han T, Song P, Wu Z, Xiang X, Liu Y, Wang Y, Fang H, Niu Y, Shen C. MSC secreted extracellular vesicles carrying TGF-beta upregulate Smad 6 expression and promote the regrowth of neurons in spinal cord injured rats. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2022;18:1078–1096. doi: 10.1007/s12015-021-10219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haraszti RA, Miller R, Stoppato M, Sere YY, Coles A, Didiot MC, Wollacott R, Sapp E, Dubuke ML, Li X, Shaffer SA, DiFiglia M, Wang Y, Aronin N, Khvorova A. Exosomes produced from 3D cultures of MSCs by tangential flow filtration show higher yield and improved activity. Mol Ther. 2018;26:2838–2847. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrop JS, Hashimoto R, Norvell D, Raich A, Aarabi B, Grossman RG, Guest JD, Tator CH, Chapman J, Fehlings MG. Evaluation of clinical experience using cell-based therapies in patients with spinal cord injury:a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17:230–246. doi: 10.3171/2012.5.AOSPINE12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RB, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hua J, Gong J, Meng H, Xu B, Yao L, Qian M, He Z, Zou S, Zhou B, Song Z. Comparison of different methods for the isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord matrix:proliferation and multilineage differentiation as compared to mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood and bone marrow. Cell Biol Int. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cbin.10188. doi:10.1002/cbin.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang JH, Xu Y, Yin XM, Lin FY. Exosomes derived from miR-126-modified MSCs promote angiogenesis and neurogenesis and attenuate apoptosis after spinal cord injury in rats. Neuroscience. 2020a;424:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang JH, Fu CH, Xu Y, Yin XM, Cao Y, Lin FY. Extracellular vesicles derived from epidural fat-mesenchymal stem cells attenuate NLRP3 inflammasome activation and improve functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neurochem Res. 2020b;45:760–771. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02950-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang JH, Yin XM, Xu Y, Xu CC, Lin X, Ye FB, Cao Y, Lin FY. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells attenuates apoptosis, inflammation, and promotes angiogenesis after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:3388–3396. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang T, Jia Z, Fang L, Cheng Z, Qian J, Xiong F, Tian F, He X. Extracellular vesicle-derived miR-511-3p from hypoxia preconditioned adipose mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates spinal cord injury through the TRAF6/S1P axis. Brain Res Bull. 2022;180:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang W, Qu M, Li L, Liu T, Lin M, Yu X. SiRNA in MSC-derived exosomes silences CTGF gene for locomotor recovery in spinal cord injury rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021a;12:334. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02401-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang W, Lin M, Yang C, Wang F, Zhang M, Gao J, Yu X. Rat bone mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes loaded with miR-494 promoting neurofilament regeneration and behavioral function recovery after spinal cord injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021b;2021:1634917. doi: 10.1155/2021/1634917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurlbert RJ, Hadley MN, Walters BC, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, Rozzelle CJ, Ryken TC, Theodore N. Pharmacological therapy for acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery 72 Suppl. 2013;2:93–105. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827765c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Zimmerman LJ, Liebler DC, Ping J, Liu Q, Evans R, Fissell WH, Patton JG, Rome LH, Burnette DT, Coffey RJ. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell. 2019;177:428–445.e418. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia X, Huang G, Wang S, Long M, Tang X, Feng D, Zhou Q. Extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells containing microRNA-381 protect against spinal cord injury in a rat model via the BRD4/WNT5A axis. Bone Joint Res. 2021a;10:328–339. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.105.BJR-2020-0020.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia Y, Yang J, Lu T, Pu X, Chen Q, Ji L, Luo C. Repair of spinal cord injury in rats via exosomes from bone mesenchymal stem cells requires sonic hedgehog. Regen Ther. 2021b;18:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia Y, Lu T, Chen Q, Pu X, Ji L, Yang J, Luo C. Exosomes secreted from sonic hedgehog-modified bone mesenchymal stem cells facilitate the repair of rat spinal cord injuries. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2021c;163:2297–2306. doi: 10.1007/s00701-021-04829-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Z, Zhang J. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes containing miR-145-5p reduce inflammation in spinal cord injury by regulating the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Cycle. 2021;20:993–1009. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2021.1919825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalra H, Drummen GP, Mathivanan S. Focus on extracellular vesicles:introducing the next small big thing. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:170. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang J, Guo Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes promote neurological function recovery in a rat spinal cord injury model. Neurochem Res. 2022;47:1532–1540. doi: 10.1007/s11064-022-03545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang J, Li Z, Zhi Z, Wang S, Xu G. MiR-21 derived from the exosomes of MSCs regulates the death and differentiation of neurons in patients with spinal cord injury. Gene Ther. 2019;26:491–503. doi: 10.1038/s41434-019-0101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, Klüter H, Bieback K. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1294–1301. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HY, Kumar H, Jo MJ, Kim J, Yoon JK, Lee JR, Kang M, Choo YW, Song SY, Kwon SP, Hyeon T, Han IB, Kim BS. Therapeutic efficacy-potentiated and diseased organ-targeting nanovesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells for spinal cord injury treatment. Nano Lett. 2018;18:4965–4975. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JR, Kyung JW, Kumar H, Kwon SP, Song SY, Han IB, Kim BS. Targeted delivery of mesenchymal stem cell-derived nanovesicles for spinal cord injury treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4185. doi: 10.3390/ijms21114185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C, Jiao G, Wu W, Wang H, Ren S, Zhang L, Zhou H, Liu H, Chen Y. Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit neuronal apoptosis and promote motor function recovery via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:1373–1383. doi: 10.1177/0963689719870999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li C, Qin T, Zhao J, He R, Wen H, Duan C, Lu H, Cao Y, Hu J. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome-educated macrophages promote functional healing after spinal cord injury. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:725573. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.725573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li D, Zhang P, Yao X, Li H, Shen H, Li X, Wu J, Lu X. Exosomes derived from miR-133b-modified mesenchymal stem cells promote recovery after spinal cord injury. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:845. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, Zhang Y, Mu J, Chen J, Zhang C, Cao H, Gao J. Transplantation of human mesenchymal stem-cell-derived exosomes immobilized in an adhesive hydrogel for effective treatment of spinal cord injury. Nano Lett. 2020a;20:4298–4305. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c00929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li R, Zhao K, Ruan Q, Meng C, Yin F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal microRNA-124-3p attenuates neurological damage in spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury by downregulating Ern1 and promoting M2 macrophage polarization. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020b;22:75. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-2146-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang Y, Wu JH, Zhu JH, Yang H. Exosomes secreted by hypoxia-pre-conditioned adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduce neuronal apoptosis in rats with spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2022;39:701–714. doi: 10.1089/neu.2021.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu W, Tang P, Wang J, Ye W, Ge X, Rong Y, Ji C, Wang Z, Bai J, Fan J, Yin G, Cai W. Extracellular vesicles derived from melatonin-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells containing USP29 repair traumatic spinal cord injury by stabilizing NRF2. J Pineal Res. 2021a;71:e12769. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu W, Wang Y, Gong F, Rong Y, Luo Y, Tang P, Zhou Z, Zhou Z, Xu T, Jiang T, Yang S, Yin G, Chen J, Fan J, Cai W. Exosomes derived from bone mesenchymal stem cells repair traumatic spinal cord injury by suppressing the activation of a1 neurotoxic reactive astrocytes. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:469–484. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu W, Rong Y, Wang J, Zhou Z, Ge X, Ji C, Jiang D, Gong F, Li L, Chen J, Zhao S, Kong F, Gu C, Fan J, Cai W. Exosome-shuttled miR-216a-5p from hypoxic preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells repair traumatic spinal cord injury by shifting microglial M1/M2 polarization. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:47. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-1726-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu WZ, Ma ZJ, Li JR, Kang XW. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes:therapeutic opportunities and challenges for spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021b;12:102. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lotvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Buzas EI, Di Vizio D, Gardiner C, Gho YS, Kurochkin IV, Mathivanan S, Quesenberry P, Sahoo S, Tahara H, Wauben MH, Witwer KW, Thery C. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions:a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:26913. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu Y, Zhou Y, Zhang R, Wen L, Wu K, Li Y, Yao Y, Duan R, Jia Y. Bone mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote recovery following spinal cord injury via improvement of the integrity of the blood-spinal cord barrier. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:209. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo Y, Xu T, Liu W, Rong Y, Wang J, Fan J, Yin G, Cai W. Exosomes derived from GIT1-overexpressing bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote traumatic spinal cord injury recovery in a rat model. Int J Neurosci. 2021;131:170–182. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1734598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:728–741. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]