Huntington’s disease (HD) (OMIM 143100) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by a monogenic mutation in the huntingtin gene (HTT), which induces typical midlife onset and age-dependent progression with major symptoms including choreic movements, psychiatric disorders, and cognitive impairment (Gusella et al., 2021). After the 1993 discovery of a pathogenic expansion of the CAG trinucleotide repeat beyond 35 in HTT exon 1 as a causative factor for HD, many animal, mammalian cell and yeast models expressing mutant HTT (mHtt) with abnormal CAG repeats have been created to study CAG repeat-induced toxicity (Naphade et al., 2019; Gusella et al., 2021). With these models and studies on human subjects, some important insights into disease initiation and progression mechanisms have been elucidated, but the underlying mHtt-induced toxicity mechanisms are still not yet fully understood with no disease-modifying treatment in sight (Caron et al., 2018; Veldman and Yang, 2018; Gusella et al., 2021).

Previous studies have revealed that the toxicity of mHtt is CAG length-dependent, and the longer CAG repeats are associated with the earlier onset and more aggressive progression of the disease (Gusella et al., 2021). At the molecular level, the CAG repeat codes for a polyglutamine (polyQ) tract. In the normal population, HTT proteins contain 6Q to 35Q repeats acting as a scaffold for various molecular interactions and are essential for normal brain development before birth, while the mHtt proteins (≥ 36Q repeats) cause protein aggregation and numerous pathophysiological changes (Veldman and Yang, 2018; Naphade et al., 2019). The formation of insoluble protein aggregates is a pathological hallmark of HD even though no clear results indicate whether these aggregates are a cause or result of pathogenesis (Naphade et al., 2019; Gusella et al., 2021). Neuropathological analysis of post-mortem brains from HD patients and brains from HD animals revealed that dramatic degeneration of neurons is initiated in the striatum and the deeper layers of the cerebral cortex, followed by the other regions of the brain (Rangel-Barajas and Rebec, 2016; Veldman and Yang, 2018). The pathophysiological mechanisms of HD are complex involving the dysregulation of various cellular processes, such as gene transcription, proteostasis, mitochondrial function, and chromatin modification, resulting in progressive neuronal loss (Veldman and Yang, 2018; Naphade et al., 2019; Gusella et al., 2021). Although HD is an inherited disease and mutant gene carriers could be identified before symptom onset, disease-modifying treatments targeting suppression of mRNA transcript or the protein are still unavailable (Caron et al., 2018; Gusella et al., 2021). A scarcity of studies aimed at understanding early affected cellular pathways by mHtt protein may be a reason for the lack of effective treatments for the disease (Hung et al., 2022). Therefore, it is essential to explore novel model systems to investigate early affected cellular pathways, which might facilitate our understanding of disease initiation and progression processes, and aid us to develop early prevention strategies.

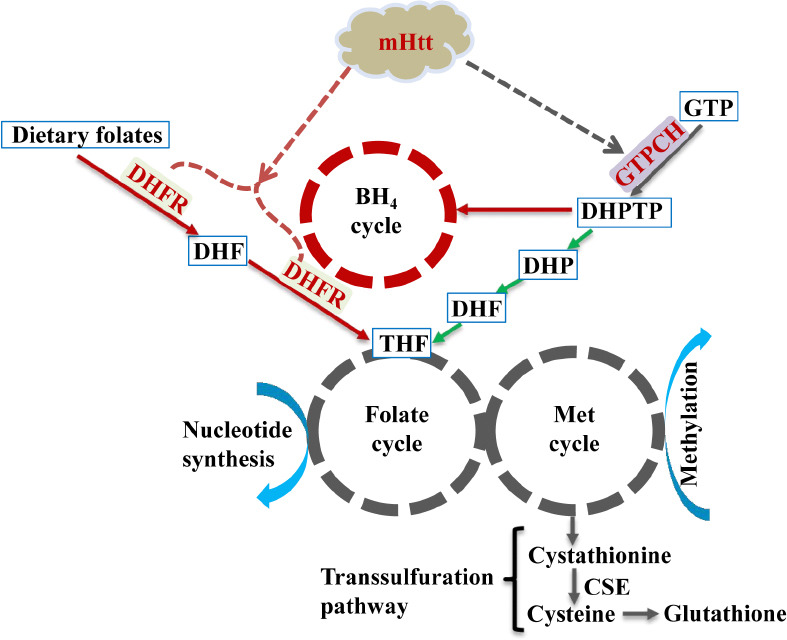

Recent studies suggest that folate-mediated one-carbon (C1) metabolism may play an important role in neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), including HD (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017; Zsindely et al., 2021; Lionaki et al., 2022). The C1 metabolism comprises the folate cycle, the methionine cycle, and the transsulfuration pathway (Figure 1) and plays important roles in many physiological processes across organisms (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017; Gorelova et al., 2017; Lionaki et al., 2022). The folate and methionine cycles enable cells to generate C1 units. The latter are used for the synthesis of purine and thymidine, and for the methylation of DNA, RNA, and histone proteins, which are known to have effects on regulating gene expression levels transcriptionally and/or translationally and maintaining genome stability. The transsulfuration pathway involves the transfer of sulfur from homocysteine to cysteine, leading to the generation of several sulfur metabolites, including antioxidant glutathione and gaseous signaling molecule hydrogen sulfide. Stringent control of this pathway via regulation of key enzymes cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) is essential for the maintenance of optimal cellular function. Depletion of CSE, an enzyme catalyzing the synthesis of cysteine from cystathionine (Figure 1) has been observed in HD, and its loss is thought to be responsible for neurotoxicity and oxidative stress (Paul et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

The relationship between mHtt and C1 and BH4 metabolism.

Expression of mutant huntingtin exon-1 (mHttex1) affects both murine and plant C1 metabolism. See text for details. Red arrows stand for mammal-specific metabolism, green arrows stand for plant-specific while gray arrows stand for both. Solid lines represent known pathways while dashed lines are postulated from the study of Hung et al. (2022).

The generic term “folate” includes tetrahydrofolate (THF) and its derivatives, which are a group of tripartite molecules carrying C1 units at varying oxidation states. Plants are autotrophs and can synthesize folate de novo, while mammals depend on dietary folates. Diet-derived folic acid (vitamin B9) is first reduced to dihydrofolate and then converted to the metabolically active form THF by two successive NADPH-dependent reductions catalyzed by the same dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) enzyme (Figure 1) before it enters the folate cycle. Because of the involvement of C1 metabolism in multiple important physiological processes, it is tightly regulated by intracellular levels of metabolites and cofactors. Any disturbance in either the folate or methionine cycle could lead to altered transcriptional and translational activities genome-wide, ultimately affecting cell survival and proliferation (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017; Gorelova et al., 2017).

Although research directly implicating C1 metabolism in HD is scarce, some studies have shown that mHtt modulates DNA methylation, and protein methylation and acetylation thereby affecting transcriptional activity (Caron et al., 2018; Zsindely et al., 2021; Ratovitski et al., 2022), and inducing the instability of CAG repeats through meiotic transmission (Gusella et al., 2021). These studies imply that C1 metabolism likely plays a role in HD. Moreover, folate deficiency has been reported to increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, and cause neural tube defects (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017; Zsindely et al., 2021; Lionaki et al., 2022). S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), vitamin B6, B9, and B12 supplements have been shown to exert beneficial effects on NDDs and reduce the risk of dementia (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017; Gorelova et al., 2017). Moreover, supplementation of cysteine or increasing the production of cysteine by a Golgi stressor could provide protection benefits in HD (Paul et al., 2014; Sbodio et al., 2018). Polymorphisms of C1 metabolism-related genes are also found to be associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and HD (Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017; Zsindely et al., 2021). All these studies suggest a strong link between the C1 metabolism and HD along with other NDDs; however, the molecular connection between them remains elusive.

Recently, we developed a plant-based mHtt model system by stably expressing mHttex1 (HTT exon 1 with abnormal CAG repeats) in tobacco plants for the investigation of the mHtt-mediated dysregulation of cellular pathways (Hung et al., 2022). After the confirmation that mHttex1 was stably integrated into the tobacco genome as well as properly transcribed and translated, we observed that mHttex1 caused protein aggregation and that the toxic effects of expanded polyQ on protein aggregation and plant growth, especially root and root hair development, were polyQ length-dependent similar to those reported in animal HD models. We believe that all the toxic effects observed in transgenic plants resulted from the gain-of-function of mHttex1 since plants lack an HTT ortholog. This helps avoid any associated effects from endogenous HTT. A quantitative proteomic study of Httex1Q63 (abnormal) and Httex1Q21 (normal control line) young roots revealed that polyQ63 triggered widespread proteomic remodeling including many proteins that are known to be affected in other HD models. Most importantly, the autotrophic feature of plants with the ability to synthesize folates de novo allowed us to discover hitherto unreported mHtt-mediated impairment of folate biosynthesis and C1 metabolism. These novel findings are supported by proteomic results showing polyQ63 reducing the abundance of GTP cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH) by 6-fold and significantly affecting 38 out of 42 SAM-dependent methyltransferases (SAM-MTases) as well as many C1 metabolism-associated proteins (≥ 1.5-fold reduction, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). In plants, GTPCH is a rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the first step in folate biosynthesis, while SAM-MTases play critical roles in the transfer of methyl groups to various biomolecules (Gorelova et al., 2017). The 6-fold decrease in GTPCH abundance likely affects folate biosynthesis and impairs C1 metabolism.

Since there is a large evolutionary distance between plants and animals, we further validated these major findings from mHttex1 transgenic plants in young (4-week-old) R6/2 HD mice (Hung et al., 2022). In both plants and mammals, GTPCH catalyzes the same reaction to convert guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to dihydroneopterin triphosphate (DHPTP) (Figure 1). However, the produced DHPTP is converted into dihydrofolate (DHF) in plants to enter the folate cycle, while in animals it is transformed into tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) through a series of reactions. In animals, GTPCH is a key enzyme that regulates the biosynthesis of BH4, an essential cofactor for aromatic amino acid hydroxylases to produce monoamine neurotransmitters, while DHFR is a critical enzyme for folate utilization as well as an alternate enzyme for the reduction of dihydrobiopterin (BH2) back to BH4 (Figure 1). We discovered that mHttex1 significantly impaired the expression of both GTPCH and DHFR in total brain tissues isolated from 4-week-old HD mice. We also found that glycine was increased by 26.5% in brain tissues, while serine was increased by 17.9% in plasma. These two amino acids are the major sources of C1 units. Thus, animal results showed that mHttex1 not only impaired GTPCH and DHFR expression but also affected the C1-related metabolism at the juvenile stage.

Our findings from both young plant and mouse HD models imply that the disturbance of C1 metabolism could be an early event in the pathogenesis of mHtt and that the enzymes GTPCH and DHFR might be the “missing molecular links” connecting C1 metabolism to HD. The mHtt-mediated early impairment of DHFR expression and C1 metabolism can help explain some previously observed common HD pathogenesis, such as the dysfunction of gene regulation, genome maintenance, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, and imprinting (Zsindely et al., 2021), as well as the instability of CAG repeat inheritance (Gusella et al., 2021). These epigenetic changes in HD could be linked to mHtt-induced alterations of DNA and protein methylation (Caron et al., 2018; Zsindely et al., 2021; Ratovitski et al., 2022). Additionally, both HTT locus and HTT arginines were also found to be differentially methylated in HD patients (Zsindely et al., 2021; Ratovitski et al., 2022). All these affected processes could be the results of altered DNA and/or protein methylation. Concerning DNA methylation, it is established by the transfer of a methyl group to the C5 position of cytosine residue from SAM resulting in 5-methylcytosine by the DNA methyltransferases. Available evidences show that folate deficiency and dysfunction of C1 metabolism cause a reduction in SAM levels, and an increase in homocysteine levels, followed by accumulation of a potent DNA methyltransferase inhibitor S-adenosylhomocysteine that suppresses DNA methylation (Gorelova et al., 2017). Concerning arginine methylation, methyl groups from SAM are transferred to the terminal nitrogen atom of arginine residues by protein arginine methyltransferases (Ratovitski et al., 2022). Arginine methylation functions as an epigenetic regulator of transcription. Thus, the mHtt-induced suppression of DHFR would affect folate utilization and C1 metabolism, which in turn can disturb the SAM and methyl group production, and subsequently impair DNA and protein methylation.

In addition, DHFR plays dual roles in the folate cycle as well as in the conversion of BH2 back to BH4, which interconnects the folate and BH4 cycles (Xu et al., 2014). Genetic defects in DHFR were found to cause insufficient cerebral BH4 levels (Xu et al., 2014), while GTPCH-deficient mice exhibited the reduction of BH4 and dopamine, the accumulation of phenylalanine, and the infancy-onset motor impairments (Jiang et al., 2019). In R6/2 HD mice, our study revealed that not only GTPCH- and DHFR-associated C1 metabolism but also both BH4 metabolism and neurotransmitter biosynthesis were disturbed by mHtt at a very early stage (Hung et al., 2022). Interestingly, unlike DHFR which was uniformly suppressed in 4-week-old R6/2 mice, the expression of GTPCH was found to be reduced in the cortex but induced in the striatum when compared to the same age wild-type control (Hung et al., 2022). This inverse expression of GTPCH in the cortex and striatum in young R6/2 mice may well help explain the mHtt-induced neuronal loss differentially in these two regions. It has been reported that the striatum is affected by mHtt much earlier with more severe neuronal loss than the cortex, and the aberrant communication between the striatum and cortex has been considered to play a critical role in striatal neuronal loss (Rangel-Barajas and Rebec, 2016; Veldman and Yang, 2018). Under healthy conditions, the cortico-striatal system is tightly regulated by dopamine (Veldman and Yang, 2018). Since GTPCH is a key enzyme for BH4 biosynthesis with the latter being essential for dopamine biosynthesis, mHtt-mediated perturbation of GTPCH expression may cause an imbalance in the cortico-striatal system through dysregulation of dopamine synthesis and thus contribute to the selective vulnerability of striatal neurons to toxic polyQ repeats (Rangel-Barajas and Rebec, 2016). Further studies are, however, warranted to understand when the inverse expression of GTPCH starts, how the GTPCH expression ratio between the cortex and the striatum changes during disease onset and progression, and what are the relationships among DHFR, GTPCH, folate, and C1 metabolism, and monoamine neurotransmitter biosynthesis.

In addition to HD, at least eight other CAG repeat expansion-mediated NDDs share the common features of pathological protein aggregation and age-dependent progressive neurodegeneration with known genetic causes (Naphade et al., 2019). In these CAG trinucleotide repeat diseases, polyQ-induced cellular damage by the time any disease symptoms appear might already be too advanced for any treatment to be successful. Thus, any strategy preventing the development of disease or impeding the progression of disease early will be promising for improving health and quality of life for mutant gene carriers. The monogenic nature of HD and the simple PCR test for genetic diagnosis of the disease have allowed for reliable identification of mutant gene carriers before symptomatic onset. Theoretically, treatments for HD could be initiated much earlier than the premanifest phase of the disease to prevent or even reverse neuronal dysfunction once the early affected cellular pathways are identified. Given the importance of C1 metabolism and the BH4 cycle in the central nervous system (Xu et al., 2014; Ducker and Rabinowitz, 2017; Jiang et al., 2019), the observed changes in the levels of DHFR, GTPCH, and certain C1/BH4 metabolism-related enzymes and metabolites in young HD mice could be significant contributing factors to HD onset and progression. We believe that our findings will open new avenues to study the roles of DHFR, GTPCH, and C1 and BH4 metabolism in the initiation and progression of HD, and perhaps of other CAG repeat diseases.

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant (SC1GM111178) to JX.

Footnotes

C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Caron NS, Dorsey ER, Hayden MR. Therapeutic approaches to Huntington disease:from the bench to the clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:729–750. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ducker GS, Rabinowitz JD. One-carbon metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2017;25:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorelova V, Ambach L, Rébeillé F, Stove C, Van Der Straeten D. Folates in plants:research advances and progress in crop biofortification. Front Chem. 2017;5:21. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gusella JF, Lee JM, MacDonald ME. Huntington's disease:nearly four decades of human molecular genetics. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30:R254–263. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung CY, Zhu CS, Kittur FS, He MT, Arning E, Zhang JH, Johnson AJ, Jawa GS, Thomas MD, Ding TT, Xie JH. A plant-based mutant huntingtin model-driven discovery of impaired expression of GTPCH and DHFR. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79:553. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04587-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang X, Liu H, Shao Y, Peng M, Zhang W, Li D, Li X, Cai Y, Tan T, Lu X, Xu J, Su X, Lin Y, Liu Z, Huang Y, Zeng C, Tang YP, Liu L. A novel GTPCH deficiency mouse model exhibiting tetrahydrobiopterin-related metabolic disturbance and infancy-onset motor impairments. Metabolism. 2019;94:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lionaki E, Ploumi C, Tavernarakis N. One-carbon metabolism:pulling the strings behind aging and neurodegeneration. Cells. 2022;11:214. doi: 10.3390/cells11020214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naphade S, Tshilenge KT, Ellerby LM. Modeling polyglutamine expansion diseases with induced pluripotent stem cells. Neurotherapeutics. 2019;16:979–998. doi: 10.1007/s13311-019-00810-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul BD, Sbodio JI, Xu R, Vandiver MS, Cha JY, Snowman AM, Snyder SH. Cystathionine γ-lyase deficiency mediates neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease. Nature. 2014;509:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rangel-Barajas C, Rebec GV. Dysregulation of corticostriatal connectivity in Huntington's Disease:a role for dopamine modulation. J Huntingtons Dis. 2016;5:303–331. doi: 10.3233/JHD-160221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratovitski T, Jiang M, O'Meally RN, Rauniyar P, Chighladze E, Faragó A, Kamath SV, Jin J, Shevelkin AV, Cole RN, Ross CA. Interaction of huntingtin with PRMTs and its subsequent arginine methylation affects HTT solubility, phase transition behavior and neuronal toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2022;31:1651–1672. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sbodio JI, Snyder SH, Paul BD. Golgi stress response reprograms cysteine metabolism to confer cytoprotection in Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:780–785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717877115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veldman MB, Yang XW. Molecular insights into cortico-striatal miscommunications in Huntington's disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2018;48:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu F, Sudo Y, Sanechika S, Yamashita J, Shimaguchi S, Honda S, Sumi-Ichinose C, Mori-Kojima M, Nakata R, Furuta T, Sakurai M, Sugimoto M, Soga T, Kondo K, Ichinose H. Disturbed biopterin and folate metabolism in the Qdpr-deficient mouse. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3924–3931. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zsindely N, Siági F, Bodai L. DNA Methylation in Huntington's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:12736. doi: 10.3390/ijms222312736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]