Key Words: autophagy, behavior, ferroptosis, MPTP, Parkinson’s disease, PC12 cell, rapamycin, tyrosine hydroxylase

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder, and ferroptosis plays a significant role in the pathological mechanism underlying Parkinson’s disease. Rapamycin, an autophagy inducer, has been shown to have neuroprotective effects in Parkinson’s disease. However, the link between rapamycin and ferroptosis in Parkinson’s disease is not entirely clear. In this study, rapamycin was administered to a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinson’s disease mouse model and a 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced Parkinson’s disease PC12 cell model. The results showed that rapamycin improved the behavioral symptoms of Parkinson’s disease model mice, reduced the loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, and reduced the expression of ferroptosis-related indicators (glutathione peroxidase 4, recombinant solute carrier family 7, member 11, glutathione, malondialdehyde, and reactive oxygen species). In the Parkinson’s disease cell model, rapamycin improved cell viability and reduced ferroptosis. The neuroprotective effect of rapamycin was attenuated by a ferroptosis inducer (methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate) and an autophagy inhibitor (3-methyladenine). Inhibiting ferroptosis by activating autophagy may be an important mechanism by which rapamycin exerts its neuroprotective effects. Therefore, the regulation of ferroptosis and autophagy may provide a therapeutic target for drug treatments in Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common degenerative disease of the central nervous system, and its main manifestation is disordered movement (Tysnes and Storstein, 2017; Reich and Savitt, 2019). The main pathological changes in PD are neuronal degeneration and loss (Tysnes and Storstein, 2017), which leads to a decrease in dopamine levels in the striatum, and the appearance of the characteristic ubiquitinated Lewy bodies in the residual dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) (Lotankar et al., 2017). α-Synuclein, which is the main component of Lewy bodies, is a primary hallmark of PD (Burré et al., 2018). However, the pathogenesis of PD is relatively complex. In recent years, researchers have found that the pathogenesis of PD involves many processes, including mitochondrial dysfunction (Malpartida et al., 2021), oxidative stress (Trist et al., 2019), autonomic dysfunction (Chen et al., 2020), and inflammation (Pajares et al., 2020). At present, it is believed that the massive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and the appearance of α-synuclein in the SN are the two basic pathological features of PD (Raza et al., 2019).

Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death involving iron ions that is caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced lipid peroxidation (Hirschhorn and Stockwell, 2019; Zhou et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2021). Oxidative stress of vital organelles (mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum and lysosomes) is the main cause of ferroptosis (Mou et al., 2019). Recent studies have shown that ferroptosis is a key contributor in PD pathogenesis (Mahoney-Sánchez et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Ferroptosis causes a metabolic imbalance in the organelles of dopaminergic neurons by interfering with intracellular iron metabolism, thus leading to oxidative stress in various organelles. High ROS levels induce dopaminergic neuron apoptosis, which accelerates the development of PD (Zhang et al., 2020). The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), ROS, glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and recombinant solute carrier family 7, member 11 (SLC7A11) can be measured as indicators of the degree of ferroptosis, according to a previous study (Li et al., 2020).

Autophagy is a process of self-digestion that is connected with the regulation of cell growth, aging and death in eukaryotic cells (Glick et al., 2010; Rickman et al., 2022). Previous studies have reported that ferroptosis requires the participation of autophagy, and that some factors involved in regulating autophagy (e.g., p53, STAT3, and Nrf2) and selective autophagy (e.g., ferritinophagy, lipophagocytosis, circadian autophagy and chaperone mediated autophagy) play roles in the process of ferroptosis (Wu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). These findings suggest that the link between autophagy and ferroptosis should be investigated as a potential therapeutic target. Some studies reported that autophagy activation was related to the occurrence of ferroptosis (Wu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021), but the exact mechanism is still unclear. The ratio of light chain 3 (LC3)-II/LC3I and P62 protein expression has been used as an indicator to evaluate the degree of autophagy (Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011). How to influence neuronal ferroptosis by modulating autophagic activity may have great significance for the treatment of neurological diseases. An in-depth study of the role of autophagy and its effects in ferroptosis will provide new perspectives for the treatment of neurological diseases.

To date, the interaction between autophagy and ferroptosis has not been studied in PD. In this study, we investigated the role of Rapa and its effects in autophagy and ferroptosis in in vivo and in vitro PD models.

Methods

Experimental animals

Fifty-two 4- to 6-week-old specific-pathogen-free-grade C57BL/6J male mice (weighing 200–250 g) were obtained from the Animal Experiment Center of Hubei University of Medicine (experimental animal production license No. SCXK (E) 2019-0008; experimental animal use license No. SYXK (E) 2019-0031). The animal study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hubei University of Medicine on October 20, 2021 (approval No. 2021-059), and conducted in strict accordance with international laws and National Institutes of Health policies, including the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed, National Research Council, 2011). The mice were kept five per cage and fed under conditions of a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 22 ± 1°C room temperature and humidity of 50–70%. This study was reported in accordance with the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) (Percie du Sert et al., 2020).

Experimental grouping

In total, 52 mice were divided into four groups: Control group, model (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine [MPTP]; Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) group, Rapa (Sigma) group (Rapa + MPTP), and ferroptosis inhibitor (methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate [RSL3]; Sigma) group (Rapa + MPTP + RSL3). There were 10 mice in each group. The Control group was intraperitoneally injected with normal saline (25 mL/kg). The PD model was intraperitoneally injected with MPTP (25 mg/kg) once a day for 7 days. The Rapa + MPTP group was intraperitoneally injected with 5 mg/kg Rapa 1 hour before MPTP administration. For the Rapa + MPTP + RSL3 group, Rapa followed by RSL3 (25 mg/kg) 30 minutes later were intraperitoneally injected once a day 1 hour before MPTP administration. The animals from each group were treated with the same number of injections (25 mL/kg saline; 25 mg/kg MPTP; 5 mg/kg Rapa + 25 mg/kg MPTP; 5 mg/kg Rapa + 25 mg/kg MPTP + 25 mg/kg RSL3) every day. The mice were weighed before injection every day, and the body weights of the mice were sorted every day for comparison.

Climbing pole test

This test was used to measure the motor function of the mice (Matsuura et al., 1997). Each mouse was positioned on the top of a homemade climbing rod dome (60 cm in height and 0.8 cm in diameter), and the time that the mouse took to get down from the rod dome was recorded by a second chronograph.

Traction test

This test was used to measure the muscle strength of the mice (Kuribara et al., 1977). The mouse forepaws were suspended on a horizontal wire (5 mm in diameter), and the time from the beginning of suspension to when the mouse fell was recorded by a second chronograph.

Tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemical staining

After anesthetization by pentobarbital (1%, 50 mg/kg; Sigma), the mice were transcardially perfused with saline for 5 minutes. After perfusion, the mice were decapitated, and then the brains were harvested and placed in 10% formalin-phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (0.1 M, pH 7.4; Sigma) solution to be fixed for 2 days, and then embedded in paraffin. Coronal sections (35 μm) were cut by a cryostat (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) through the entire midbrain. Immunohistochemical staining was performed as follows: (1) the sections were deparaffinized with xylene twice for 5 minutes, and then dehydrated in an ethanol gradient (75%, 90%, and 100%). (2) The sections were washed three times with PBS for 5 minutes each. (3) The sections were incubated with 3% methanol-hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) solution for 15 minutes at 37°C. (4) After three PBS washes, heat-induced antigen retrieval was conducted by incubation with sodium citrate (Sigma) buffer at 110°C for 5 minutes. (5) After three PBS washes, normal goat serum blocking solution (Sigma) was added dropwise and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. (6) The anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) recombinant rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# OPA1-04050, RRID: AB_325653) was added dropwise and incubated at 4°C overnight. (7) After three PBS washes, a horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# MA5-27548, RRID: AB_2735288) was added dropwise (1:200) and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. (8) After three PBS washes, diaminobenzidine (Sigma) color development was performed for 5 minutes. (9) After three PBS washes, the sections were subjected to hematoxylin counterstaining.

TH-immunoreactive cells were observed and counted by a blinded observer with a DM4DF7000T fluorescence microscope (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Retention of dopaminergic neurons on the lesion side was expressed as the ratio of the number of TH-positive neurons on the lesion side to that of the contralateral side. Two sections were selected for each mouse, and four high-power (100×) fields were randomly selected for each section. The numbers of TH-positive cells in each field were counted by two observers who were blinded to the grouping of the sections before observing them.

MDA, GSH and ROS levels

The mice in each group were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbitone. The brain from each mouse was quickly harvested on ice, the right midbrain and striatum were excised, and the tissue was stored at –80°C for further use. The tissue was weighed, and then normal saline was added in proportion (1:5). The samples were homogenized and then centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were collected, and the protein concentrations were determined by the Coomassie brilliant blue method (Lott et al., 1983).

The levels of MDA, GSH and ROS (fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry, which reflected the ROS level) in the right midbrain and striatum homogenates and intracellular MDA, GSH and ROS were determined using the MDA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), ROS assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the glutathione assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), respectively, according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Cell culture

The PC12 cells (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China, Cat# SCSP-517) exhibit some features of mature dopaminergic neurons and are commonly used in neuroscience research (Duan et al., 2015), including in studies on neurotoxicity, neuroprotection, neurosecretion, neuroinflammation, and synaptogenesis (Wiatrak et al., 2020). The PC12 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. The RPMI-1640 was replaced every 2 days. When the cells had grown to 80% confluence, they were passaged with trypsinization.

Cell treatment

The PC12 cells were taken for experiments in logarithmic growth phase. The experiments included two parts, each of which had four groups: (1) control group, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) group, MPP+ + Rapa group, and MPP+ + Rapa + RSL3 group; and (2) control group, MPP+ group, MPP+ + Rapa group, MPP+ + Rapa + 3-methyladenine (3-MA; an autophagy inhibitor) group. Rapa, MPP+, RSL3, and 3-MA were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After treatment with 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, or 40 μM Rapa or 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mM MPP+ (Sigma) for 24 hours, cell viability was assessed. After pretreatment of PC12 cells with 0, 2.5, 5 or 10 μM Rapa for 1 hour and a further 24-hour treatment with 1 mM of MPP+, cell viability was assessed. PC12 cells (5 × 105 cells/mL) were cultured in 96-well culture plates with five duplicated wells for each group. The control group was treated with DMSO (< 0.1%, which was considered to have no interference with the cell experiments). The cells in the MPP+ + Rapa group were treated with 5 μM Rapa 1 hour before MPP+ treatment. For the MPP+ + Rapa + RSL3 group and the MPP+ + Rapa + 3-MA group, Rapa (5 μM) + RSL3 (5 μM) and Rapa (5 μM) + 3-MA (5 mM), respectively, were administered before MPTP treatment.

Cell viability assay

The PC12 cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay kit (Sigma). Cells were treated with 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent and 100 μL of RPMI-1640, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation at 37°C for 2 hours, the optical density value was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 450 nm.

Western blotting assay

The right midbrain and striatum tissue from the brains of mice were lysed on ice for 30 minutes using lysis buffer. The harvested lysates and PC12 cells were collected at 10,000 × g (4°C) for 20 minutes by centrifugation, and then lysed in RIPA buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Protein concentrations were evaluated using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The protein samples were separated by 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Beyotime), and then were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (MerckMillipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 hour at room temperature, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: rat anti-GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; monoclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, USA, Cat# 2118, RRID: AB_561053), rabbit anti-TH (polyclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 2792, RRID: AB_2303165), rabbit anti-α-synuclein (monoclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 23706, RRID: AB_2798868), rabbit anti-SLC7A11 (polyclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 98051, RRID: AB_2800296), rabbit anti-GPX4 (polyclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 52455, RRID: AB_2924984), rabbit anti-p62 (monoclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 8025, RRID: AB_10859911), and rabbit anti-LC3 B (monoclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 3868, RRID: AB_2137707). After that, the membranes were washed in TBS-T (Thermo Fisher Scientific) four times for 10 minutes each, and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:5000; goat, polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 7074, RRID: AB_2099233 or Cat# 7077, RRID: AB_10694715) for 2 hours at room temperature. The membranes were visualized with the ChemiDocTM XRS system (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative protein expression was normalized to GAPDH.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. All statistical data were analyzed with SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) or GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to evaluate statistical comparisons between means. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Rapa pretreatment reverses motor deficits and the weight loss induced by MPTP

We initially investigated the potential neuroprotective effects of Rapa in an MPTP-induced PD mouse model (Figure 1A). The body weight of the MPTP group was greatly decreased compared with that of the control mice (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 1B). Pretreatment with 5 mg/kg Rapa reversed the MPTP-induced weight loss (P < 0.05 for each comparison). Next, the effect of Rapa on the motor abilities of the MPTP-induced model mice was assessed using the pole test and traction test. MPTP significantly inhibited the pole-climbing capacity of mice in the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison), and the pole-climbing ability of the Rapa group was improved compared with that in the MPTP group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 1C). In the traction test, the grip time of the MPTP group was significantly decreased compared with that of the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison), whereas the grip time of the Rapa group was significantly increased compared with that of the MPTP group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Rapa inhibits body weight loss and improves MPTP-induced behavioral deficits in mice.

(A) Timeline of the experimental procedure. Mice were randomly divided into four groups and administered MPTP (25 mg/kg/day), Rapa (5 mg/kg/day) or RSL3 (25 mg/kg/day). (B) Effect of MPTP, Rapa, or RSL3 on body weight of mice. Pole-climbing (C) and traction (D) tests were used to assess motor function of mice. The data presented are from all animals and the samples were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 8–10 per group). *P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). MPTP: 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; Rapa: rapamycin; RSL3: methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate.

Rapa inhibits the MPTP-induced deterioration of DA neurons.

Western blotting analysis showed that the α-synuclein level was significantly higher in the SN of the MPTP group than in that of the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 2A). Pretreatment with Rapa decreased α-synuclein expression compared with the MPTP group (P < 0.01 for each comparison).

Figure 2.

Rapa protects against dopaminergic neuron loss in the SN of MPTP-treated mice.

(A) Western blotting analysis of TH and α-synuclein protein levels. (B) TH-positive cells were stained by immunocytochemistry and observed through a fluorescence microscope. Black arrows indicate TH-positive cells. Scale bars: 500 μm (upper) and 100 μm (lower). Lower panels are enlarged images of the boxes in the upper panels. (C) Number of TH-positive cells. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6–8 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MPTP: 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; Rapa: rapamycin; RSL3: methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate; SN: substantia nigra; TH: tyrosine hydroxylase.

Immunohistochemical staining was used to assess the TH level and DA neuron survival in the SN. The number of TH-positive neurons in the MPTP group was significantly lower than that in the SN of control mice (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 2B and C). Pretreatment with Rapa inhibited the MPTP-induced decrease in TH-positive neuron number (P < 0.05 for each comparison). Moreover, we investigated TH expression in the different groups. TH expression in the MPTP group was significantly decreased compared with that in the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 2A). Pretreatment with Rapa significantly inhibited the decrease in TH expression in the SN compared with MPTP treatment alone (P < 0.05 for each comparison).

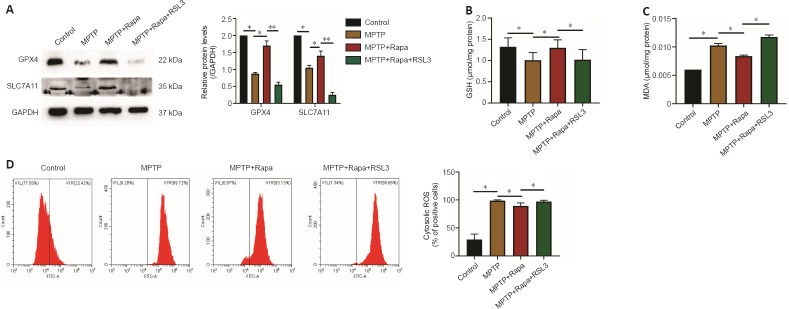

Rapa exerts neuroprotective effects against MPTP by inhibiting ferroptosis

To determine whether Rapa regulates ferroptosis, we investigated the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4. SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression were markedly decreased in the MPTP group compared with the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 3A). Pretreatment with Rapa reversed the MPTP-induced decrease in SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression (P < 0.05 for each comparison). Furthermore, pretreatment with the ferroptosis inducer RSL3 decreased SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression compared with the Rapa group (P < 0.01 for each comparison; Figure 3A). MPTP and Rapa affected the levels of MDA, GSH and ROS (Figure 3B–D). Moreover, pretreatment with RSL3 reversed the Rapa-induced changes in MDA, GSH and ROS levels compared with Rapa pretreatment (Figure 3B–D). Additionally, RSL3 pretreatment decreased the weight and extended the pole-climbing time and traction time compared with Rapa pretreatment (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 1B–D). The number of TH-positive neurons in mice pretreated with RSL3 was markedly reduced compared with that in the Rapa group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Rapa inhibits ferroptosis in MPTP-treated mice.

(A) Western blotting analysis of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and recombinant solute carrier family 7, member 11 (SLC7A11). The concentrations of glutathione (GSH; B), malondialdehyde (MDA; C) and reactive oxygen species (ROS; D) in the supernatant of the brain after treatment. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6–8 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MPTP: 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; Rapa: rapamycin; RSL3: methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate.

Rapa antagonizes the MPP+-induced decrease in PC12 cell viability

After cells were treated with MPP+ at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mM for 24 hours, CCK-8 assay showed that MPP+ reduced PC12 cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 4A). At an MPP+ concentration of 1 mM, PC12 cell viability was decreased by approximately 50% (P < 0.05 for each comparison). Therefore, we used 1 mM of MPP+ to treat PC12 cells in subsequent experiments. Then, 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μM Rapa were used to treat PC12 cells for 24 hours. At the Rapa concentration of 10 μM, cell viability was significantly decreased (Figure 4B); therefore, we used 5 μM Rapa to investigate its underlying mechanisms in PC12 cells. After pretreatment with 5 μM Rapa for 1 hour and 1 mM MPP+ treatment for 24 hours in PC12 cells, CCK-8 assay showed that Rapa reversed the decrease in cell viability caused by MPP+ treatment (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Rapa inhibits MPP+-induced decrease in PC12 cell viability.

(A) Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was used to evaluate the changes of PC12 cell viability 24 hours after MPP+ (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mM) treatment. (B) CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate the changes of PC12 cell viability 24 hours after Rapa (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, or 40 μM) treatment. (C) After pretreatment of PC12 cells with 0, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM Rapa for 1 hour and a further 24-hour treatment with 1 mM MPP+, a CCK-8 assay was used to detect the change of cell viability. The data presented are from three different passages of cells used to seed separate 96-well plates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 9–12 per group).*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. MPP+ (−) and Rapa (−); #P < 0.05, vs. Rapa (−) (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test;). The experiments were performed in triplicate. MPP+: 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; Rapa: rapamycin; RSL3: methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate.

Rapa alleviates MPP+-induced PC12 cell ferroptosis

After 1 hour of 5 μM Rapa or 5 μM RSL3 pretreatment, PC12 cells were treated with 1 mM MPP+ and incubated for 24 hours. We assessed GSH, MDA and ROS levels in the cells. MDA and ROS levels in the MPP+ group were markedly increased, and the GSH level was significantly decreased in the MPP+ group compared with those in the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 5A–C). Then, we assessed the levels of ferroptosis protein markers SLC7A11 and GPX4. SLC7A11 and GPX4 levels in the MPP+ group were significantly decreased compared with those in the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Rapa inhibits MPP+-induced ferroptosis in PC12 cells.

PC12 cells were divided into four groups: control group treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), MPP+ group treated with MPP+ (1 mM), MPP+ + Rapa group treated with Rapa (5 μM) 1 hour before MPP+ treatment, MPP+ + Rapa+ RSL3 group treated with Rapa (5 μM) and RSL3 (5 μM) 1 hour before MPP+ treatment. Kits were used to determine the concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA; A), glutathione (GSH; B) and reactive oxygen species (ROS; C) in the supernatant. (D) Recombinant solute carrier family 7, member 11 (SLC7A11) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) levels were determined using western blotting analysis. PC12 cells in logarithmic growth phase were taken for experiments. The data presented are from three different passages of cells. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 8–10 per group). *P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). The experiments were performed in triplicate. MPP+: 1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; Rapa: rapamycin; RSL3: methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate.

Then, we assessed the levels of GSH, MDA and ROS in 1 mM MPP+-treated PC12 cells that were also treated with Rapa to investigate whether Rapa suppresses MPP+-induced ferroptosis. MDA and ROS levels were decreased and the GSH level was significantly increased in the Rapa group compared with the MPP+ group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 5A–C). Western blotting results indicated that Rapa significantly reduced GPX4 and SLC7A11 levels (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 5D). RSL3 reversed the effects of Rapa on PC12 cells (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 5A–D).

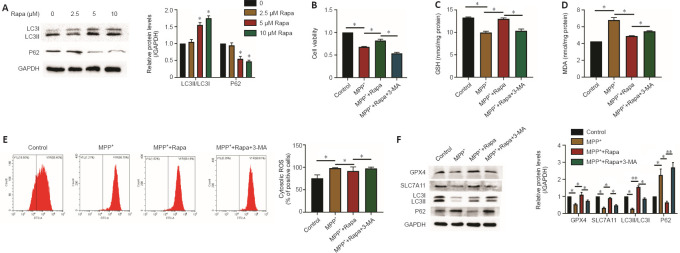

Rapa reduces MPP+-induced PC12 cell ferroptosis via autophagy

Studies have demonstrated that autophagy enhances ferroptosis via ferritin and transferrin receptor regulation (Park and Chung, 2019; Wu et al., 2021). However, whether the ferroptosis reduced by Rapa in PD involves autophagy is unclear. Therefore, we investigated whether autophagy was influenced by Rapa in PC12 cells. After Rapa treatment (0, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM), the levels of LC3II/LC3I were increased, and the levels of P62 were significantly decreased compared with those in the control group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Rapa reduces MPP+-induced PC12 cell ferroptosis via autophagy.

(A) PC12 cells were treated with 0, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM Rapa for 24 hours, and the expression of LC3II and P62 was determined by western blot assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. 0 (B) Cell viability was measured after treatment with 1 mM MPP+ and/or 5 μM Rapa and/or 5 mM 3-MA for 24 hours by CCK-8 assay. The effect of 5 mM 3-MA on the concentrations of glutathione (GSH; C), malondialdehyde (MDA; D) and reactive oxygen species (ROS; E) in PC12 cells treated with 5 μM Rapa. (F) The effect of 5 mM 3-MA on the protein levels of P62, LC3, recombinant solute carrier family 7, member 11 (SLC7A11), and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) in 5 μM Rapa-treated PC12 cells. PC12 cells in logarithmic growth phase were taken for experiments. The data presented are from three different passages of cells. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6–10 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). LC3: Light chain 3; MPP+: 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; Rapa: rapamycin; RSL3: methyl (1S,3R)-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-1,3,4,9-tetrahyyridoindole-3-carboxylate.

Next, we decreased PC12 cell autophagy using 3-MA. Cell viability was significantly decreased after 5 mM 3-MA pretreatment (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 6B). Moreover, the expression of LC3II/LC3I and P62 showed the Rapa-induced increase in autophagy was antagonized by 3-MA (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 6F). Western blotting showed that the upregulated expression of GPX4 and SLC7A11 was reversed by 3-MA in the Rapa group (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 6F). Furthermore, after pretreatment with 3-MA, the changes in the MDA, ROS and GSH levels caused by Rapa were reversed (P < 0.05 for each comparison; Figure 6C–E).

Discussion

Rapa has been shown to exert neuroprotective effects in different animal models (Saliba et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019), and was shown to have protective effects in PD via its anti-inflammation and antioxidation activities (Ramalingam et al., 2019). Rapa was shown to induce iron ion outflow and decrease iron deposition in the SN, thus ameliorating brain injury in a PD mouse model (Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, Rapa was shown to weaken PC12 cell neurotoxicity by diminishing ROS levels and promoting cell viability (Wang et al., 2016). In the present study, Rapa pretreatment reduced motor deficits and reversed weight loss in the MPTP-induced PD mouse model. Our results also showed that Rapa protected DA neurons against MPTP neurotoxicity, and inhibited the reduction of cell viability induced by MPP+.

Multiple studies have shown that ferroptosis activation is involved in the progression of PD (Wu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Ferroptosis, which is a regulated form of cell death, is characterized by lipid ROS overproduction, iron accumulation, GPX4 redox defense disruption and GSH depletion (Qiu et al., 2020). Our study showed that GSH levels were decreased, whereas MDA and ROS levels were increased with MPTP and MPP+ treatment in mice and cells, respectively. Moreover, the MPTP-treated mice and MPP+-treated PC12 cells had decreased GPX4 and SLC7A11 expression, indicating ferroptosis after MPTP/MPP+ treatment. These findings indicate that MPTP and MPP+ induced ferroptosis in mouse and cell PD models, respectively. Furthermore, our results showed that Rapa treatment markedly decreased MPTP- and MPP+-induced ferroptosis in the mouse and cell PD models, respectively.

We then investigated the potential mechanism. The lipid peroxidation-mediated ferroptosis depend on autophagy (Zhou et al., 2020), and the autophagy pathway connects cellular sensitivity with ferroptosis (Dai et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). The occurrence of ferroptosis requires the participation of autophagy and autophagy plays important roles in the process of ferroptosis (Wu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). There is increasing evidence that excessive autophagy promotes ferroptosis (Ma et al., 2016; Kang and Tang, 2017; Park and Chung, 2019). Nevertheless,in this study of PD models, our results are in contrast to those in previous studies. It showed a new relationship of ferroptosis and autophagy. We showed that activation of autophagy pathway inhibited ferroptosis in PD models. We found that MPP+-treated PC12 cells that were treated with Rapa expressed higher LC3II/LC3I and P62 proteins levels than those not treated with Rapa, which suggests that Rapa activated autophagy. In addition, we showed that blocking autophagy decreased the protective effects of Rapa on the MPP+-induced decrease in PC12 cell viability and ferroptosis. Together, the results indicate that Rapa activated autophagy, inhibited the MPP+-induced decrease in cell viability, and decreased ferroptosis in PC12 cells.

This study has some limitations that should be noted. The specific pathogenesis of PD is not still fully understood. Hence, injecting MPTP into the mouse brain cannot completely reproduce the neuropathological characteristics of patients with PD. Additionally, this study focused only on male mice. For more clinical application, the use of female mice should be considered in future studies. It is essential to take these limitations into account and explore the mechanism in future research. This study focused only on male mice. For more clinical application, the use of female mice should be considered in future studies.

Taken together, our results suggest that Rapa exerts a protective effect through inhibiting ferroptosis by activating autophagy in MPTP/MPP+-induced PD models. These results provide an initial theoretical and experimental basis for the potential use of Rapa as a therapeutic strategy in PD, though much research is still needed to understand its clinical significance. The potential mechanism underlying ferroptosis and autophagy in PD needs more study. In the future, we will focus on researching the potential mechanism underlying the role of Rapa in PD.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement: All relevant data are within the paper.

Editor’s evaluation: This paper reports on potential mechanism by which rapamycin can reverse MPTP/MPP+-induced cell damage in both animal and cell culture models of Parkinson’s disease. The demonstration that the toxin-mediated damage appears to involve ferroptosis and that autophagy may play a role is preventing this damage is particularly valuable, as it points to potential new avenues for treatment approaches.

C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editor: Li CH; L-Editors: McCollum L, Li CH, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Burré J, Sharma M, Südhof TC. Cell biology and pathophysiology of α-synuclein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8:a024091. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a024091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Z, Li G, Liu J. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson's disease:Implications for pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;134:104700. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai E, Han L, Liu J, Xie Y, Kroemer G, Klionsky DJ, Zeh HJ, Kang R, Wang J, Tang D. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis drives tumor-associated macrophage polarization via release and uptake of oncogenic KRAS protein. Autophagy. 2020;16:2069–2083. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1714209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan X, Wang W, Dai R, Yan H, Liu L. Current situation of PC12 cell use in neuronal injury study. Int J Biotechnol Wellness Ind. 2015;4:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan BY, Pang YL, Li WX, Zhao CX, Zhang Y, Wang X, Ning GZ, Kong XH, Liu C, Yao X, Feng SQ. Liproxstatin-1 is an effective inhibitor of oligodendrocyte ferroptosis induced by inhibition of glutathione peroxidase 4. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:561–566. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.293157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy:cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirschhorn T, Stockwell BR. The development of the concept of ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang R, Tang D. Autophagy and ferroptosis - What's the connection? Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2017;5:153–159. doi: 10.1007/s40139-017-0139-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuribara H, Higuchi Y, Tadokoro S. Effects of central depressants on rota-rod and traction performances in mice. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1977;27:117–126. doi: 10.1254/jjp.27.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Cao F, Yin H, Huang Z, Lin Z, Mao N, Sun B, Wang GG. Ferroptosis:past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:88. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Liu J, Xu Y, Wu R, Chen X, Song X, Zeh H, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Wang X, Tang D. Tumor heterogeneity in autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Autophagy. 2021;17:3361–3374. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1872241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Du J, Lu Y, Lin X. Neuroprotective effects of rapamycin on spinal cord injury in rats by increasing autophagy and Akt signaling. Neural Regen Res. 2019;14:721–727. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.247476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Kuang F, Kroemer G, Klionsky DJ, Kang R, Tang D. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis:machinery and regulation. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27:420–435. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lotankar S, Prabhavalkar KS, Bhatt LK. Biomarkers for Parkinson's disease:recent advancement. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:585–597. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lott JA, Stephan VA, Pritchard KA. Evaluation of the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 method for urinary protein. Clin Chem. 1983;29:1946–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma S, Henson ES, Chen Y, Gibson SB. Ferroptosis is induced following siramesine and lapatinib treatment of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2307. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahoney SL, Bouchaoui H, Ayton S, Devos D, Duce JA, Devedjian JC. Ferroptosis and its potential role in the physiopathology of Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2021;196:101890. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malpartida AB, Williamson M, Narendra DP, Martins RW, Ryan BJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson's disease:from mechanism to therapy. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46:329–343. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuura K, Kabuto H, Makino H, Ogawa N. Pole test is a useful method for evaluating the mouse movement disorder caused by striatal dopamine depletion. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;73:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(96)02211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy:renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mou Y, Wang J, Wu J, He D, Zhang C, Duan C, Li B. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death:opportunities and challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:34. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park E, Chung SW. ROS-mediated autophagy increases intracellular iron levels and ferroptosis by ferritin and transferrin receptor regulation. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:822. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2064-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pajares M, Rojo AI, Manda G, Boscá L, Cuadrado A. Inflammation in Parkinson's disease:mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cells. 2020;9:1687. doi: 10.3390/cells9071687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, Emerson M, Garner P, Holgate ST, Howells DW, Karp NA, Lazic SE, Lidster K, MacCallum CJ, Macleod M, Pearl EJ, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0:Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu Y, Cao Y, Cao W, Jia Y, Lu N. The application of ferroptosis in diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:104919. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reich SG, Savitt JM. Parkinson's disease. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raza C, Anjum R, Noor Ul, Shakeel A. Parkinson's disease:Mechanisms, translational models and management strategies. Life Sci. 2019;226:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramalingam M, Huh YJ, Lee YI. The Impairments of α-synuclein and mechanistic target of rapamycin in rotenone-induced SH-SY5Y cells and mice model of Parkinson's disease. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1028. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickman AD, Hilyard A, Heckmann BL. Dying by fire:noncanonical functions of autophagy proteins in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17:246–250. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.317958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saliba SW, Vieira EL, Santos RP, Jalil EC, Fiebich BL, Vieira LB, Teixeira AL, Oliveira AC. Neuroprotective effects of intrastriatal injection of rapamycin in a mouse model of excitotoxicity induced by quinolinic acid. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:25. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0793-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tysnes OB, Storstein A. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2017;124:901–905. doi: 10.1007/s00702-017-1686-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trist BG, Hare DJ, Double L. Oxidative stress in the aging substantia nigra and the etiology of Parkinson's disease. Aging Cell. 2019;18:e13031. doi: 10.1111/acel.13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Gao N, Li Z, Yang Z, Zhang T. Autophagy alleviates melamine-induced cell death in PC12 cells via decreasing ros level. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:1718–1729. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z, Yuan L, Li W, Li J. Ferroptosis in Parkinson's disease:glia-neuron crosstalk. Trends Mol Med. 2022;28:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiatrak B, Kubis-Kubiak A, Piwowar A, Barg E. PC12 cell line:cell types, coating of culture vessels, differentiation and other culture conditions. Cell. 2020;9:958. doi: 10.3390/cells9040958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu L, Liu M, Liang J, Li N, Yang D, Cai J, Zhang Y, He Y, Chen Z, Ma T. Ferroptosis as a new mechanism in Parkinson's disease therapy using traditional chinese medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:659584. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.659584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Z, Geng Y, Lu X, Shi Y, Wu G, Zhang M, Shan B, Pan H, Yuan J. Chaperone-mediated autophagy is involved in the execution of ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:2996–3005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819728116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang G, Yin L, Luo Z, Chen X, He Y, Yu X, Wang M, Tian F, Luo H. Effects and potential mechanisms of rapamycin on MPTP-induced acute Parkinson's disease in mice. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:2889–2897. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang P, Chen L, Zhao Q, Du X, Bi M, Li Y, Jiao Q, Jiang H. Ferroptosis was more initial in cell death caused by iron overload and its underlying mechanism in Parkinson's disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;152:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou B, Liu J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Kroemer G, Tang D. Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;66:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]