ABSTRACT

Anther development from stamen primordium to pollen dispersal is complex and essential to sexual reproduction. How this highly dynamic and complex developmental process is controlled genetically is not well understood, especially for genes involved in specific key developmental phases. Here we generated RNA sequencing libraries spanning 10 key stages across the entirety of anther development in maize (Zea mays). Global transcriptome analyses revealed distinct phases of cell division and expansion, meiosis, pollen maturation, and mature pollen, for which we detected 50, 245, 42, and 414 phase‐specific marker genes, respectively. Phase‐specific transcription factor genes were significantly enriched in the phase of meiosis. The phase‐specific expression of these marker genes was highly conserved among the maize lines Chang7‐2 and W23, indicating they might have important roles in anther development. We explored a desiccation‐related protein gene, ZmDRP1, which was exclusively expressed in the tapetum from the tetrad to the uninucleate microspore stage, by generating knockout mutants. Notably, mutants in ZmDRP1 were completely male‐sterile, with abnormal Ubisch bodies and defective pollen exine. Our work provides a glimpse into the gene expression dynamics and a valuable resource for exploring the roles of key phase‐specific genes that regulate anther development.

Keywords: anther development, maize, male‐sterile, phase‐specific genes, transcriptome, ZmDRP1

Next‐generation sequencing of the four key maize anther development phases based on anther length identified phase‐specific marker genes, providing a valuable resource for exploring key phase‐specific genes that play essential roles during anther development.

INTRODUCTION

Male reproductive organs are vital for seed reproduction in all plants including crop plants (Ma, 2005). Maize (Zea mays) plants carry spatially separated male and female florets, making this species a good model system to study anther development. Maize anther development is initiated in the stamen primordium with the outer layer (L1) forming the epidermis and the inner layer (L2) differentiating into the primary parietal cells (PPCs) and archesporial cells (ARs) (Kelliher and Walbot, 2014; Kelliher et al., 2014; Walbot and Egger, 2016). PPCs then divide periclinally to establish endothecium cells and secondary parietal cells (SPCs) adjacent to the ARs (Kelliher and Walbot, 2012). Subsequently, SPCs generate the middle layer and tapetum by periclinal division. After the architecture of the four somatic cell layers is established in each anther lobe, there is a period of rapid mitotic proliferation, after which the ARs mature into pollen mother cells (PMCs) (Walbot and Egger, 2016). The PMCs switch to meiosis when anthers reach ~1.2 mm in length in the maize W23 inbred line (Nelms and Walbot, 2019), proceeding through one round of DNA replication followed by two successive nuclear and cellular divisions (meiosis I and meiosis II), and reaching completion with tetrad formation. Microspores are then released from tetrads and undergo two cycles of mitosis to produce the final trinucleate pollen grains (Ma, 2005). During gametophyte development, first the middle layer and then the tapetum degenerates (Kelliher and Walbot, 2011). The entire process of maize anther development spans nearly 30 d from stamen primordium initiation to final pollen dispersal (Ma et al., 2008).

Investigating gene expression profiles throughout the entire span of anther development, and in particular identifying genes with phase‐specific expression, is vital to exploring the mechanisms by which anther development is regulated and discovering key genes potentially useful for hybrid breeding. Initial studies have utilized low‐density microarray hybridization to assess patterns of gene expression in three to seven anther developmental stages in Arabidopsis thaliana (Alves‐Ferreira et al., 2007), maize (Ma et al., 2006, 2008), and rice (Oryza sativa) (Deveshwar et al., 2011). Transcriptome profiling of five pre‐meiotic anther stages highlighted the complexity of maize anther transcriptomes across stages and cell types by using an updated microarray (Zhang et al., 2014). Microarrays also elucidated the initial specification of maize somatic cells and their loss of pluripotency in comparison to ARs (Kelliher and Walbot, 2014). To understand the process and the molecular basis of this mitosis–meiosis transition, microarray data was generated for germinal cells at three sequential stages, which revealed that the enlarging PMC stage is crucial during this transition at a time when genes related to protein biosynthesis and degradation are highly expressed (Yuan et al., 2018). More recently, transcriptome deep sequencing (RNA‐seq) has allowed for greater confidence in the identification of expressed genes in crop plants: maize (10 developmental stages plus pollen) (Zhai et al., 2015), wheat (Triticum aestivum, four stages) (Feng et al., 2017), barley (Hordeum vulgare, four stages) (Barakate et al., 2021), and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, three stages) (Dhaka et al., 2020). The maize study compared the inbred line W23 to four developmental mutants, with a focus on understanding the requirements for phased small interfering RNA biogenesis; although the stages included initial early anther steps (0.2‐ and 0.4‐mm anthers), the data were not evaluated for stage‐specific factors (Zhai et al., 2015). Single‐cell RNA‐seq was used to trace the trajectory of AR differentiation over an 8‐d period through the leptotene–zygotene transition in prophase I of meiosis (Nelms and Walbot, 2019). Very recently, to explore stage‐specific TFs, RNA‐seq was applied to maize anthers from 11 developmental stages (Jiang et al., 2021) in three inbred lines (B73, Zheng58 and M6007), although the initial stages of anther ontogeny were not included. While maize anther development is very well correlated with anther length, recent studies have employed microscopy to validate staging (Nelms and Walbot, 2019; Jiang et al., 2021).

To date, although hundreds to thousands of stage‐specific genes have been identified, only a few have been demonstrated as useful markers for any particular stage or phase. Among the handful of male‐sterile genes cloned, only eight have been experimentally validated as being phase‐specific, including five genes (ABNORMAL POLLEN VACUOLATION1 (ZmAPV1), IRREGULAR POLLEN EXINE1 (ZmIPE1), ZmIPE2, Male sterile 45 (ZmMs45), and ZmMs6021) exclusively expressed from the tetrad to the uninucleate microspore stage after meiosis (Cigan et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2017; Somaratne et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2017; Huo et al., 2020). The remaining three genes (ZmC5, Zm58 and Zm13) were specifically expressed in mature pollen (Hanson et al., 1989; Turcich et al., 1993; Wakeley et al., 1998).

Here we report a comprehensive investigation of maize transcriptomes from 10 stages primarily corresponding to specific anther lengths in the elite Chinese inbred line Chang7‐2, which has large tassels with abundant anthers and is widely used for breeding, primarily as the paternal line. A major goal was to elucidate genes with expression restricted to a specific phase of anther development and to include analysis of the earliest steps in anther ontogeny. We categorized these transcriptomes into four distinct groups corresponding to the phases of cell division and expansion, meiosis, pollen maturation, and mature pollen. Furthermore, we demonstrated that a desiccation‐related gene, ZmDRP1, is essential to maintain male fertility in maize.

RESULTS

Generation and analysis of transcriptome data for 10 developmental stages of maize anthers based on anther size

To investigate the dynamics of gene expression across the entirety of anther development, we first assessed the developmental status of anthers of different sizes from Chang7‐2, a versatile parental line for many commercial varieties in China (Lai et al., 2010) which produces abundant anthers even in greenhouse conditions. Using light microscopy of semi‐thin transverse sections, we determined that 0.2‐mm anthers had undergone specification of ARs and initial somatic cells and the L2 had developed into SPCs and endothecium (Figure 1A). During the 0.7‐mm stage, SPCs had undergone division and partitioned into the middle layer and tapetal cells (Figure 1B). The specification of cell types was complete in 1.0‐mm anthers, when the ARs were undergoing mitosis (Kelliher and Walbot, 2014) (Figure 1C). The post‐mitotic ARs then enlarged and prepared to enter meiosis at the 1.3‐mm stage (Figure 1D, K). The meiocytes were at zygotene in 1.5‐mm anthers and had reached pachytene in 2.0‐mm anthers (Figure 1E, F, L, M). After the second meiotic division, the tetrads appeared at approximately the 2.5‐mm stage (Figure 1G, N). After meiosis, tetrads separated and the uninucleate microspores formed around the 3.0‐mm stage (Figure 1H, O). During the 4.0‐mm stage, microspores underwent the first mitotic division, and tapetal cells almost completely degenerated into cellular debris (Figure 1I). Finally, the mature pollen grains formed (Figure 1J). The timing and anther length‐based stages of inbred line Chang7‐2 were developmentally similar to those of the inbred line W23 (Kelliher and Walbot, 2014; Zhai et al., 2015), providing us a great opportunity to systematically compare gene expression between inbred lines.

Figure 1.

Transcriptome relationships among 10 stages of maize anther development

(A–J) Transverse sections of maize anthers from the 0.2‐ to 4.0‐mm stages, and scanning electron microscopy of pollen. SPC, secondary parietal cell (yellow); PPC, primary parietal cell (light green); T, tapetum (blue); ML, middle layer (deep red); En, endothecium (aquamarine); E, epidermis (orange); AR‐Msp, germinal cells from archesporial cells to microspores (purple). Bars = 30 µm. (K–O) 4ʹ,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole staining of germinal cells from the 1.3‐ to 3.0‐mm stages of maize anther development. Bars = 5 µm. (P) Cluster dendrogram of gene expression profiles for 10 stages of maize anther development, corresponding to four developmental phases: cell division and expansion (I: blue), meiosis (II‐a: pink; II‐b: deep pink), pollen maturation (III: light green), and mature pollen (IV: orange). Genes expressed in at least one stage (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM) ≥ 1) were used for hierarchical clustering by utilizing a Log2 (FPKM + 0.01) normalization step. Each correlation coefficient (Y axis) represents the distance between any two stages. (Q) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the transcriptomes of anther samples for nine development stages. Log2 (FPKM + 0.01) values for genes expressed in at least one sample (FPKM ≥ 1) were used for PCA.

We performed RNA‐seq for 21 samples of anthers at different stages (0.2–4.0 mm, plus mature pollen) isolated from Chang7‐2. There were two biological replicates for each stage (or three replicates for pollen). We generated a total of ~640 million high‐quality paired‐end 150‐bp reads, of which ~90.9% mapped uniquely to the maize B73 reference genome V4 (Jiao et al., 2017). We only used uniquely mapped reads to calculate normalized gene expression in terms of fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM) (Tables S1, S2). FPKM values correlated well between the biological replicates (average Pearson's correlation coefficient r = 0.97) (Figure S1). Hence, we represented the expression level for any given gene as the average FPKM value for the two or three replicates; we considered a gene to be expressed only if the mean FPKM value was ≥1 (Table S2). We thus obtained 26,409 genes, including 1,650 encoding transcription factors (TFs), expressed in at least one sample (Table S3). The number of expressed genes among the 10 stages varied from 7,141 (mature pollen) to 22,108 (1.5‐mm anther) (Figure S2). The less complex pollen transcriptome observed here was consistent with previous studies and is a conserved feature among diverse species (Honys and Twell, 2004; Gómez et al., 2015).

We validated the RNA‐seq expression profiles by analyzing the expression of eight genes that are involved in anther development. Two of these genes, ZmOCL4 (OUTER CELL LAYER4) and ZmLG2 (LIGULELESS2), are involved in anther somatic cell differentiation (Walsh and Freeling, 1999; Vernoud et al., 2009) and exhibited a peak in expression at the 0.2‐mm anther stage in our dataset (Figure S3A). ZmAFD1 (ABSENCE OF FIRST DIVISION1), encoding a maize REC8‐like protein involved in sister chromatid cohesion (Golubovskaya et al., 2006), and ZmMis12‐1 (minichromosome instability 12‐1), encoding a kinetochore protein participating in sister kinetochore association (Li and Dawe, 2009), were highly expressed at the 1.5‐ to 2.0‐mm stages (Figure S3A). ZmMs7 is an ortholog of Arabidopsis AtMS1 (Ito et al., 2007) and rice OsPTC1 (PERSISTENT TAPETAL CELL1) (Li et al., 2011), encoding a plant homeodomain finger TF and is required for tapetal cell death and late pollen development (Zhang et al., 2018a). ZmIPE1 encodes a putative glucose‐methanol‐choline oxidoreductase that participates in anther cuticle and pollen exine development (Chen et al., 2017). We observed that ZmMs7 and ZmIPE1 were preferentially expressed at the 3.0‐mm uninucleate microspore stage (Figure S3A), which was consistent with previous results (Wan et al., 2019). In addition, ZmC5 encodes a pectin methylesterase (PME), and Zm13 encodes a pollen allergen, and both were specifically expressed in pollen (Hanson et al., 1989; Wakeley et al., 1998). Notably, these eight genes exhibited similar expression patterns across anther development in both inbred lines Chang7‐2 (Figure S3A) and W23 (Figure S3B). In summary, the expression dynamics of these genes is consistent with previous studies, indicating the high quality and reliability of our data and providing an opportunity to compare gene expression patterns among different inbred lines.

Comparison of global transcriptomes for 10 stages grouped into four distinct anther developmental phases

To gain insight into the transcriptome dynamics of maize anther development, we performed hierarchical clustering (Figure 1P) and principal component analysis (PCA; Figures 1Q, S4) using data acquired for the 10 stages of anther development. Consistent with the correspondence between anther length and anther development in a previous report (Kelliher and Walbot, 2014), our transcriptome dataset generally formed four distinct groups of genes associated with cell division and expansion, meiosis, pollen maturation, and mature pollen (Figure 1P), which was similar to data for inbred line W23 (Figure S5).

Samples from the cell division and expansion stages (i.e., the 0.2‐mm to 1.3‐mm stages) formed the first cluster, designated Phase I. During this phase, ARs complete their mitotic divisions and gradually mature into PMCs, and somatic cells have differentiated into stereotypical shapes and volumes when the length of anthers reaches 1.3 mm (Walbot and Egger, 2016; Nelms and Walbot, 2019). Samples from stages 1.5 mm, 2.0 mm, 2.5 mm, and 3.0 mm comprised the second cluster and represented meiosis and tetrad dissolution in Phase II. We further divided Phase II into Phase II‐a (1.5–2.0 mm), when meiotic crossover and recombination occurred, and Phase II‐b (2.5–3 mm), corresponding to the developmental stage from late meiosis to uninucleate microspore formation. The 4.0‐mm anther stage defined the third cluster and represented the pollen maturation stage (binucleate microspore; Phase III). During this phase, the microspores undergo mitosis to produce generative and vegetative cells, and the pollen wall continues to mature (Jiang et al., 2013). The mature pollen stage consisted of Phase IV, which was distinct from the other clusters (Figure 1P), as also noted with the results of the PCA (Figure S4).

Gene expression profiles during different stages of anther development

Results of the hierarchical clustering and PCA elucidated relationships among the various developmental stages of maize anthers. To further explore the detailed functional transitions during the course of anther development, we clustered all 26,409 expressed genes, including 1,650 (6.2%) encoding TFs (Tables S3, S4), into 18 co‐expression modules using the K‐means clustering algorithm (Figure 2A). We also evaluated the expression profile of these 26,409 expressed genes in the inbred line W23 (Zhai et al., 2015). The expression profiles for most of these genes were similar between Chang7‐2 and W23 (Figure S6).

Figure 2.

Gene expression patterns and functional enrichment analysis during anther development

(A) Heatmap representation of expression patterns for genes in 18 co‐expression modules within five clusters. The genes with expression levels greater than 1 (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM) ≥ 1) during at least one stage were used for K‐means clustering, and 18 co‐expression modules were detected across the 10 stages of anther development. The co‐expression modules were further grouped into five clusters (I, II, III, IV, and a cluster shared by I–IV). For example, Cluster I consists of four co‐expression modules (A, B, C, and D). The genes included in Clusters I–IV were mainly expressed in one of the four phases described in Figure 1, while the genes in the cluster shared by I–IV were expressed in several phases. The number of genes and encoded TFs in each cluster are given to the left. The FPKM values for all genes were normalized by the maximum value for all FPKM values for all genes over the 10 development stages. (B) Functional categories enriched in four co‐expression clusters. GoSlim was used for functional enrichment analysis, with all genes as background. A hypergeometric test was carried out, and all significant categories (false discovery rate <0.05) are displayed.

Genes belonging to the first 11 co‐expression modules were preferentially expressed during only one of the four developmental phases, whereas genes belonging to the last seven modules were expressed across the time course of anther development (Figure 2A). The top 11 and bottom seven modules contained similar numbers of genes. We annotated the genes in the first 11 modules to assign them to functional Gene Ontology (GO) categories based on the four developmental phases (Figure 2B). The Phase I was best represented by 5,109 expressed genes, including 488 TF genes, in modules I‐A to I‐D (Figure 2A; Tables S3, S4). The most prominent of these highly expressed genes for this phase included ZmOCL4 (Vernoud et al., 2009), ZmAGO104 (ARGONAUTE104) (Singh et al., 2011), ZmAM1 (AMEIOTIC1) (Pawlowski et al., 2009), ZmPHS1 (POOR HOMOLOGOUS SYNAPSIS1) (Ronceret et al., 2009), and ZmRAD51C (Radiation sensitive 51c) (Jing et al., 2019) (Table S5). Genes highly expressed during Phase I were primarily assigned to the biological processes “flower development,” “endogenous stimulus response,” “abiotic stimulus response,” and “post‐embryonic development” (Figure 2B). ZmEREB162 and ZmEREB126 in module I‐A and ZmABI33 in module I‐C, encoding plant‐specific TFs containing the APETALA2 (AP2) and B3 domains, are the respective homologs of Arabidopsis RELATED TO ABI3/VP1 (AtRAV)1 and AtRAV2. Arabidopsis RAV2, also named TEMPRANILLO2 (TEM2), is an important modulator of flowering time by binding to GIGANTEA to repress the expression of the florigen component FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) (Sawa and Kay, 2011). THICK TASSEL DWARF1 (ZmTD1) in module I‐B encodes a critical regulator of inflorescence development for both the male and female parts (Bommert et al., 2005). Tassels of the td1 mutant have greater spikelet density, and male florets have greater number of stamens (Bommert et al., 2005). We also noticed Zm00001d031119 in module I‐A, which is a homolog of Arabidopsis SWITCH1 (SWI1), required for sister chromatid cohesion, recombination and axial element formation (Mercier et al., 2003). This observation was consistent with the fact that meiosis‐specific transcripts accumulate during the premeiosis stage (Kelliher and Walbot, 2014; Yuan et al., 2018).

In total, Phase II was represented by 1,615 genes (103 encoding TFs), with 931 (65 encoding TFs) belonging to module II‐a‐A and 684 (38 encoding TFs) to module II‐a‐B. The previously reported maize anther development‐related genes ZmAFD1 (Golubovskaya et al., 2006), ZmMis12‐1 (Li and Dawe, 2009), and ZmDCL5 (Dicer‐like 5) (Teng et al., 2020) were included in module II‐a‐A, with preferential expression at the 1.5‐mm stage (Table S5). Maize ZmMs8 (Wang et al., 2013) and ZmMs9 (Albertsen et al., 2014) were part of module II‐a‐B and were highly expressed at approximately the 2.0‐mm stage (Table S5). Genes from sub‐cluster II‐a were highly enriched in the “reproduction” category of GO biological processes. We identified certain genes encoding cyclins and cyclin‐dependent kinases in the “reproduction” category; for example, Zm00001d048026, one of two homologs of the regulator of meiotic prophase I SOLO DANCERS (SDS) in Arabidopsis, was upregulated at entry into meiosis, which was in line with its previously reported expression pattern (Nelms and Walbot, 2019). ATAXIA‐TELANGIECTASIA MUTATED1 (ZmATM1), which clustered in module II‐a‐B, encodes a protein kinase that phosphorylates proteins involved in DNA repair, cell cycle control, and apoptosis (Kastan and Lim, 2000). The expression of its Arabidopsis homolog ATM is induced by DNA double‐strand breaks and is essential for meiosis; atm mutants are partially sterile (Garcia et al., 2003).

The phase encompassing late meiosis to microspore formation (Phase II‐b) was best represented by 1,408 expressed genes (107 encoding TFs), including 818 (59 encoding TFs) in module II‐b‐A and 590 (48 encoding TFs) in module II‐b‐B (Figure 2A; Tables S3, S4). The cloned male sterility genes ZmMs30 (An et al., 2019) and ZmMs44 (Fox et al., 2017) clustered within module II‐b‐A, whereas ZmMs7 (Zhang et al., 2018a), ZmMs26 (Djukanovic et al., 2013), ZmMs45 (Cigan et al., 2001), ZmIG1 (INDETERMINATE GAMETOPHYTE1) (Evans, 2007), ZmIPE1 (Chen et al., 2017), ZmIPE2 (Huo et al., 2020), ZmAPV1 (Somaratne et al., 2017), and ZmMs6021 (Tian et al., 2017) grouped in module II‐b‐B (Table S5). The genes in module II‐b‐A were highly expressed in the 2.5‐mm stage, while genes in module II‐b‐B were highly expressed at the 3.0‐mm stage (uninucleate microspore) (Figure 2A). After meiosis, the callose surrounding microspores is degraded, and the young microspores form primexine, which subsequently accumulates precursors for sporopollenin and tryphine biosynthesis (Ariizumi and Toriyama, 2011; Shi et al., 2015). Consistent with anther development during this phase, genes in sub‐cluster II‐b were overrepresented for GO terms related to “secondary metabolic process” (Figure 2B). For example, ZmCYP18 in module II‐b‐A encodes a cytochrome P450 (CYP). Its Arabidopsis homolog CYP78A5 is a maternal regulator of seed size, via KLUH/CYP78A5‐dependent growth signaling (Adamski et al., 2009). ZmALDH2 in module II‐b‐B encodes an aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) that catalyzes the oxidation of aldehydes to carboxylic acids. Its paralog OsRF2A in rice encodes a nuclear restorer of male fertility that can overcome URF13‐mediated cytoplasm male sterility (Skibbe et al., 2002).

Phase III was best represented by 3,045 expressed genes, including 226 genes encoding TFs, in modules III‐A (1,582 genes, 112 encoding TFs) and III‐B (1,463 genes, 114 encoding TFs) (Figure 2A; Tables S3, S4). Genes in cluster III were highly enriched in GO terms related to “photosynthesis.” Most subepidermal and endothelial cells of maize anthers contain chloroplasts, which correspond well with the observation that most photosynthesis‐associated genes expressed in leaves are also expressed in maize anthers (Murphy et al., 2015). Expression of the genes encoding the photosynthesis light reaction components ZmLHCB10 (LIGHT HARVESTING CHLOROPHYLL A/B BINDING PROTEIN10), ZmPSAH1 (PHOTOSYSTEM I H SUBUNIT1), the chlorophyll biosynthesis factor ZmPCR1 (PROTOCHLOROPHYLLIDE REDUCTASE1), the Calvin‐Benson‐Bassham cycle enzymes ZmSSU1 (RIBULOSE BISPHOSPHATE CARBOXYLASE SMALL SUBUNIT1), and ZmGPA1 (GLYCERALDEHYDE‐3‐PHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE1) gradually increased throughout anther development and peaked during the 4.0‐mm stage. This result was consistent with the rise in sunlight received by anthers for photosynthesis as the tassel becomes exposed. In addition, genes in cluster III were related to lipid biosynthesis, like ZmCER8 (ECERIFERUM8) and ZmGPAT1 (GLYCEROL‐3‐PHOSPHATE ACYLTRANSFERASE1); sugar transport, like ZmSWEET11 (SUGARS WILL EVENTUALLY BE EXPORTED TRANSPORTER11); and response to abiotic stimulus, like ZmC2 (CHALCONE SYNTHASE C2).

Cluster IV comprised 1,557 genes, including 51 encoding TFs (Figure 2A; Tables S3, S4). Genes in cluster IV were preferentially expressed in pollen. In line with this observation, we identified several genes predominantly or specifically expressed in maize pollen in module IV, such as ZmC5 (Wakeley et al., 1998), Zm58 (Turcich et al., 1993), Zm13 (Hanson et al., 1989), ZmPRO1 (PROFILIN1), ZmPRO2, and ZmPRO3 (Kovar et al., 2000) (Table S5). Module IV was represented by genes showing enrichment for the GO terms “pollination” and “cell growth” (Figure 2B). For example, ZmPME5 encodes a pectin methylesterase (PME) involved in pollen germination and was highly expressed in mature pollen. ZmMLO6 is a member of the transmembrane mildew resistance locus O (MLO) family, and its Arabidopsis ortholog MLO5 is required for pollen tube responses to ovular signals (Meng et al., 2020).

We identified 13,675 genes, including 675 encoding TFs, as being expressed in more than one of the four phases of anther development (Figure 2A; Tables S3, S4). These genes were enriched in many common biological processes, including “protein metabolic process,” “catabolic process,” “nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process,” “cellular component organization,” “carbohydrate metabolic process,” “generation of precursor metabolites and energy,” and “biosynthetic process.” For example, genes related to catabolism were continuously expressed throughout anther development, including those encoding the glycolytic enzymes hexokinase and pyruvate kinase. Glycolytic metabolites play crucial roles during anther development (Tang et al., 2018).

Anther‐specific genes during anther development

Combining our data with 10 non‐anther transcriptome datasets (Wang et al., 2009; Davidson et al., 2011; Bolduc et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014), we identified 2,754 genes, including 140 genes encoding TFs, with specific expression in maize anthers or pollen (Figure S7; Table S6). The anther‐specific genes included several previously reported male sterility genes: ZmMs23, ZmMAC1 (MULTIPLE ARCHESPORIAL CELLS 1), ZmMs7, ZmMs6021, ZmMs30, ZmMs44, ZmIPE1, ZmIPE2 and ZmAPV1 (Wang et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2017; Fox et al., 2017; Nan et al., 2017; Somaratne et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018a; An et al., 2019; Huo et al., 2020). Furthermore, we noticed many genes worthy of future exploration to reveal their exact roles during anther development. For example, ZmLTPc2, also known as MZm3‐3 (Lauga et al., 2000), was the most highly expressed anther‐specific gene, with a FPKM value of 42,387. ZmLTPc2 encodes a lipid transfer protein that accumulates to high levels mainly in the tapetum during male gametogenesis and is putatively involved in pollen exine formation (Lauga et al., 2000; Wei and Zhong, 2014). OsYY1, the rice homolog of ZmLTPc2, is specifically expressed in anthers and is downregulated during microspore development in rice exposed to elevated temperature (Hihara et al., 1996; Endo et al., 2009).

Genes specifically expressed at different phases

The anther‐specific genes previously identified usually showed enrichment for biological functions during certain phases of anther development (Figure S7) and were thus useful for inferring gene function and understanding the genetic control of developmental transitions. To date, only eight maize genes are reported to be exclusively expressed during a certain phase of anther development. Here we obtained 50 high‐confidence genes specifically expressed during the cell division and expansion phase of anther development, 245 expressed during meiosis phase, 42 expressed during pollen maturation phase, and 414 expressed in pollen (Figure 3A–D; Table S7). To assess the confidence of the phase alignments, we randomly selected 12 genes (three from each of the four phases) for analysis by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR); we validated that all 12 genes were exclusively expressed during their respective phases (Figure S8).

Figure 3.

Expression patterns of phase‐specific expressed genes

(A–D) Heatmap representations of expression patterns for genes specifically expressed in the following developmental phases: cell division and expansion (A), meiosis (B), pollen maturation (C), and mature pollen (D). The number of phase‐specific expressed genes and genes encoding transcription factors (TFs), respectively, are shown in parentheses. (E–H) Expression patterns for two candidate Phase II‐a‐specific (E, F) and two Phase II‐b‐specific (G, H) genes across the 10 developmental stages. (I–L) Representative RNA in situ hybridization images for the following periods: premeiosis (I1–L1), meiosis (I2–L2), tetrad (I3–L3), uninucleate (I4–L4), and binucleate (I5–L5). Sense probes were used as negative controls for each gene at their peak expression stage (I6–L6). T, tapetum; PMC, pollen mother cell; Tds, tetrads; Msp, microspore. Bars = 100 mm.

Most of the 50 Phase I‐specific genes were expressed at low levels (average FPKM: 6.39) (Figure 3A; Table S7), and we randomly selected three genes as examples: ZmAGO5c, ZmMYB102, and ZmDOF7. ZmAGO5c encodes a member of the Argonaute family, which contributes to viral defense and reproduction (Zhang et al., 2015). ZmMYB102 belongs to a large family of plant TF genes involved in diverse biological processes including cell‐type and organ differentiation, metabolism, and responses to environmental stimuli (Ambawat et al., 2013). ZmDOF7 encodes a C2C2‐Dof‐transcription factor 7 that is critical for plant growth, seed germination, flowering time and stress responses (Khan et al., 2021). Its rice homolog OsDof4 plays an important role in the regulation of flowering time, overexpression of which accelerates flowering under long days (Wu et al., 2017). We validated by RT‐qPCR that all three genes are expressed prior to the 1.3‐mm stage (Figure S8A).

Among the 245 Phase II‐specific genes expressed in 1.5‐ to 3.0‐mm anthers (Figure 3B; Table S7), we randomly selected the three genes ZmNAS8, ZmLCB2a, and ZmDFR1 for RT‐qPCR analysis. ZmNAS8 encodes nicotianamine synthase, which is critical for the biosynthesis of phytosiderophores and response to iron deficiency in graminaceous plants (Hihara et al., 1996; Inoue et al., 2003; Mizuno et al., 2003). TaNAS7‐A2, the wheat ortholog of ZmNAS8, is specifically expressed in anthers (Bonneau et al., 2016). ZmLCB2a encodes a subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase, which catalyzes the first step of sphingolipid biosynthesis. A double mutant of the Arabidopsis orthologs LCB2a (LONG‐CHAIN BASE2a) and LCB2b is male‐sterile, indicating that sphingolipids contribute to the regulation of anther development (Dietrich et al., 2008; Teng et al., 2008). ZmDFR1 encodes a dihydroflavonoid reductase the orthologs of which in Arabidopsis (DIHYDROFLAVONOL 4‐REDUCTASE‐LIKE1, DRL1) and rice (OsDFR2) are preferentially expressed in tapetal cells during microspore development and involved in the biosynthesis of sporopollenin monomers (Tang et al., 2009; Grienenberger et al., 2010). These results suggested that ZmDFR1 might play a similar role in pollen wall formation in maize. We validated the Phase II‐specific expression profile of these genes by RT‐qPCR (Figure S8B). We also randomly selected four genes, ZmNup96c, ZmGLK2, ZmBURP7, and Zm00001d005859 (two each from Phase II‐a and ‐b), for further analysis by RNA in situ hybridization (Figure 3E–H). ZmNup96c encodes a subunit of the nuclear pore complex (Nup), which facilitates macromolecular exchange between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Knockenhauer and Schwartz, 2016). ZmGLK2 encodes a Golden2‐like TF that contributes to chloroplast development and disease resistance; certain GLK2 genes are induced by low temperature or drought (Liu et al., 2016). ZmNup96c and ZmGLK2 were Phase II‐specific and were preferentially expressed in both tapetal cells and PMCs (Figure 3I, J). ZmBURP7 is a member of the plant‐specific BURP domain‐containing family. Among the three orthologs of ZmBURP7 in Arabidopsis (PGL1, PGL2 and PGL3), PGL3 is highly expressed in flowers and stems (Park et al., 2015). Zm00001d005859, as the homologs of Arabidopsis ATYPICAL ASPARTIC PROTEASE IN ROOTS 1 (ASPR1), encodes an aspartic protease that is widely present in different plant species and is involved in protein processing or degradation in different stages of plant development, suggesting some degree of functional specialization (Simões and Faro, 2004). ZmBURP7 and Zm00001d005859 were Phase II‐specific, with peak expression at the 3.0‐mm stage and with preferential expression in tapetal cells at the uninucleate stage (Figure 3K, L).

For Phase III, 42 genes were specifically expressed during the 4.0‐mm stage (Figure 3C; Table S7), from which we randomly selected the three genes ZmSUT6, ZmCP510, and ZmSTP1 and validated their phase‐specific expression pattern by RT‐qPCR (Figure S8C). ZmSUT6 encodes a sucrose transporter involved in the transmembrane transport of sucrose. Its Arabidopsis ortholog SUT2 is expressed in numerous sink cells and tissues, such as germinating pollen (Meyer et al., 2004). Moreover, ectopic expression of apple (Malus domestica) MdSUT2 in Arabidopsis promotes early flowering and tolerance to abiotic stresses (Ma et al., 2016). ZmCCP15 was another validated Phase III‐specific gene. Its closest homolog in Arabidopsis, CP51, belongs to a large proteolytic enzyme gene family that encodes cysteine proteases; CP51 is highly expressed in flowers and participates in pollen exine formation (Richau et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014). ZmSTP9 is a sugar transport protein (STP), and its paralog ZmMST2 (MONOSACCHARIDE TRANSPORTER2) was specifically expressed in pollen. By contrast, the ZmSTP1 orthologs in Arabidopsis, STP1, STP4, STP9, STP10, STP11 and STP12, play diverse roles in shoot branching, stomatal opening, and pollen development, underscoring the diversity of sugar transporter genes (Schneidereit et al., 2003, 2005; Otori et al., 2019; Flütsch et al., 2020).

A total of 414 genes were specifically expressed in mature pollen (Figure 3D; Table S7). Among these Phase IV‐specific genes, we randomly selected Zm00001d038640, ZmPME43, and Zm00001d040838 and validated their expression profiles by RT‐qPCR (Figure S8D). Zm00001d038640 encodes a pollen allergen that contains an expansin domain. ZmPME43 was one of the 10 PME genes identified among the pollen‐specific genes and was highly expressed (Figure S8D; Table S6). The pollen‐expressed PME gene ZmGa1P confers the male function in the maize unilateral cross‐incompatibility system by interacting with the other pollen‐specific PME ZmPME10‐1 (Zhang et al., 2018b). Zm00001d040838 encodes a protein containing a membrane‐targeting C2 domain, and the Zm00001d040838 ortholog SRC2 (SOYBEAN GENE REGULATED BY COLD‐2) of Arabidopsis is upregulated during pollen germination and pollen tube growth (Wang et al., 2008).

Transcription factor genes specifically expressed at different phases

The anther‐specific genes identified here accounted for 10.4% (2,754) of all expressed genes detected. By contrast, among 1,650 TF genes expressed in our data, only 8.1% (133) showed an anther‐specific expression profile (Table S8). Among the 50, 245, 42, and 414 genes specifically expressed at cell division and expansion, meiosis, pollen maturation, and mature pollen, respectively, we only identified two (4.0%), 19 (7.8%), two (4.8%), and four (1.0%) phase‐specific TF genes, respectively (Table S8). The number of genes specifically expressed in mature pollen was much larger than the number specifically expressed at any other phase, but we identified few TF genes that appear to be specifically expressed in mature pollen. Further, we observed that the TF genes specifically expressed during the meiosis phase account for the largest proportion of phase‐specific TF genes, corresponding to about 70.4% (Table 1). Among 27 specific TF genes, 19 were specifically expressed at the meiosis stage, including nine and 10 Phase II‐a‐ and ‐b‐specific TFs, respectively. Among nine Phase II‐a‐specific TF genes, five belonged to the MADS family (three M‐type MADS and two MIKC_MADS); among 10 Phase II‐b‐specific TFs, three MYBs and two AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORs were included (Table 1). This result suggests these TFs may play crucial roles at specific developmental phases.

Table 1.

List of phase‐specific TF genes identified during maize anther development

|

*The expression pattern of phase‐specific genes encoding TFs. The FPKM values for all genes were normalized by the maximum value for all FPKM values for all genes over the 10 development stages. FPKM, fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads; TF, transcription factor.

Gene families expressed specifically during different phases

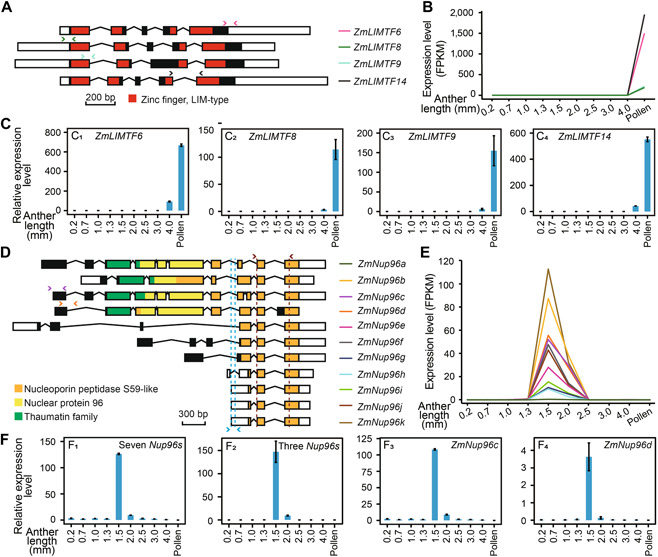

We discovered that genes encoding members of the LIM domain‐containing protein subfamily PLIM and the nuclear pore complex protein Nup96 all display phase‐specific expression. Our RNA‐seq data revealed that four maize PLIM orthologs, ZmLIMTF6, ZmLIMTF8, ZmLIMTF9, and ZmLIMTF14 (Figure 4A), were all exclusively expressed to high levels in pollen, with mean FPKM values ranging from 186.7 to 1,954.7 (Figure 4B). RT‐qPCR analysis validated the exclusive expression of these four genes in mature pollen (Figure 4C). Because these PLIM genes had similar expression patterns during anther development in Arabidopsis and maize, we speculated that they may have conserved functions during pollen development in monocots and dicots and that their functions might be redundant. In agreement with this hypothesis, the Arabidopsis genes PLIM2a and PLIM2b are partially redundant with respect to regulating pollen tube growth (Ye et al., 2013). However, further experiments are needed to delineate the exact functions of LIM proteins in maize.

Figure 4.

ZmPLIMandZmNup96families are expressed specifically in the mature pollen and meiosis phases, respectively

(A, B) Gene structures (A) and expression patterns (B) of the four ZmPLIM gene family members in maize during anther development. Gene structures were based on the B73_AGPv4 annotation. White rectangles, 5' or 3' untranslated regions (UTRs); black or red rectangles, exons. The region encoding the LIM‐type zinc‐finger domain is displayed in red. (B) Relative expression patterns of ZmLIMTF6 (C1), ZmLIMTF8 (C2), ZmLIMTF9 (C3), and ZmLIMTF14 (C4) were determined by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR) utilizing primers marked with pink, green, light green and black double‐headed arrows in (A). (D, E) Gene structures (D) and expression patterns (E) of all 11 ZmNup96 gene family members in maize during anther development. White rectangles, 5' and 3' UTRs; black, yellow, orange or green rectangles, exons. Orange, yellow, and green rectangles indicate the region encoding the nucleoporin peptidase S59‐like, nuclear protein 96, and thaumatin family domains, respectively. (F) Relative transcript levels of ZmNup96 genes, as determined by RT‐qPCR. The expression levels of seven expressed Nup96s (ZmNup96b, ZmNup96c, ZmNup96d, ZmNup96e, ZmNup96f, ZmNup96g, ZmNup96h) (F1) and three other expressed Nup96s (ZmNup96i, ZmNup96j, ZmNup96k) (F2) were assessed using the primers indicated as red and blue double‐headed arrows in (D), respectively, while ZmNup96c (F3) and ZmNup96d (F4) were validated with the primers indicated as purple and orange double‐headed arrows in (D), respectively. Data are the means of three replicates, and error bars represent SD.

Nup96 is a subunit of the Y complex (also known as Nup107‐160 or outer ring complex), a core structural subcomplex of the nuclear pore complex (Hattersley et al., 2016; Meier et al., 2017). The maize genome encodes 11 Nup96 proteins according to the current annotation of the B73_AGPv4 reference genome (Figure 4D). Ten Nup96 genes were exclusively expressed during 1.5‐mm and 2.0‐mm stages based on our RNA‐seq data and were included among our Phase II‐specific genes (Figure 3B; Table S7), whereas the remaining gene (ZmNup96a) was not expressed in anthers or any other tissue (Figure 4E). To validate the expression patterns of these 10 Nup96 genes, we designed two pairs of common primers (one pair for seven expressed Nup96 genes, and another pair for the other three Nup96 genes) along with two pairs of gene‐specific primers for ZmNup96c and ZmNup96d (Figure 4F). These two genes were expressed exclusively at the 1.5‐mm and 2.0‐mm stages, as determined by RT‐qPCR (Figure 4F3, F4). Moreover, RNA in situ hybridization analysis of ZmNup96c during the premeiosis, meiosis, tetrad, uninucleate, and binucleate stages revealed high expression in tapetum cells during meiosis and low‐level expression at the tetrad stage (Figure 3I). Another maize gene, Zm00001d048308 (orthologous to Arabidopsis Nup96), was also predominantly expressed during Phase II, although it was expressed constitutively in non‐reproductive tissue. These data indicate that the various Nup96 proteins may be essential for meiosis during anther development, but their exact functions during this process need to be determined.

Clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR‐associated protein 9 (Cas9)‐mediated mutants of the Phase II‐specific gene ZmDRP1 confer male sterility in maize

Meiosis is a key process that helps sustain anther development but is also extremely sensitive to environmental stress (De Storme and Geelen, 2014). Genes predominantly expressed during this phase were highly enriched in the GO categories “reproduction,” “secondary metabolic process,” “post‐embryonic development,” and “response to abiotic stimulus” (Figure 2B). A desiccation‐related gene, ZmDRP1, was included among Phase II‐specific genes (Figure 3B; Table S7). ZmDRP1 encodes a pcC13‐62 protein, which belongs to a desiccation‐related protein family that was first identified in the resurrection plant and is thought to participate in promoting desiccation tolerance (Piatkowski et al., 1990; Giarola et al., 2018). An analysis of the ZmDRP1 expression pattern revealed its exclusive expression during the 3.0‐mm stage, as determined by RT‐qPCR (Figure S9). RNA in situ hybridization also detected ZmDRP1 expression during other anther development stages, predominantly in the tapetum at the tetrad stage and the uninucleate stage, while we observed no obvious expression at the premeiosis stage, early meiosis stage, or binucleate microspore stage (Figure S10). These results suggest that ZmDRP1 probably functions in microspore formation.

To explore how ZmDRP1 contributes to anther development, we utilized CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated genome editing and generated three zmdrp1 mutant lines, with a 1‐bp insertion between nucleotides 220 and 221 of the single exon (total length is 999 bp). This 1‐bp insertion caused a frameshift in the open reading frame from the 74th codon and finally led to an in‐frame stop codon at the 326th codon. We therefore hypothesize that these all represent null alleles, as the mutant protein is truncated and bears only the first 73 amino acids of the wild‐type ZmDRP1 protein. Compared to their fertile segregating siblings, zmdrp1 plants displayed no obvious phenotype in terms of plant architecture (Figure S13). However, homozygous mutant lines exhibited complete male sterility (Figures 5, S11, S12) and had shorter anthers that did not exert from spikelets and contained shrunken pollen (Figures 5B–G, S11B–G). We turned to scanning electron microscopy to further investigate the structural differences of anthers and mature pollen from zmdrp1 mutants and fertile plants (Figures 5H–O, S11H–O). We observed that granular Ubisch bodies in the mutants were plumper and larger than those in fertile plants (Figures 5H–K, S11H–K). Mature zmdrp1 pollen grains were shriveled and had a cracked surface (Figures 5M, O, S11L–O), whereas the anthers of their fertile siblings had an abundance of normal, round‐shaped pollen grains (Figure 5L, N). The mechanism by which ZmDRP1 causes male sterility is unclear and should be explored in the future.

Figure 5.

Loss of ZmDRP1 function confers male sterility in maize

(A) Schematic diagram the of ZmDRP1 locus and sequences of the clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR‐associated protein 9 (Cas9)‐generated zmdrp1‐1 mutant allele. Black rectangle, exon. Red arrowhead, position of the mutation. The 20‐bp CRISPR/Cas9 target sequence adjacent to the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) is indicated in red. A single‐base insertion (T, in blue) causes a frameshift that results in the introduction of a premature stop codon. (B–G) Comparison of tassels (B, C), anthers (D, E), and pollen grains (F, G) stained with iodine potassium iodide between siblings that are either heterozygous or fertile for zmdrp1‐1 (B, D, F) or homozygous for the zmdrp1‐1 mutation (C, E, G). The phenotypes in (B–G) were observed from at least three plants. Scale bars = 1 cm (B, C), 1 mm (D, E) and 0.1 mm (F, G). (H–O) Scanning electron micrographs of the inner surfaces of anthers (H, I) and corresponding enlargement images (J, K) as well as mature pollen grains (L, M) and the outer surface of pollen grains (N, O) from fertile ZmDRP1/zmdrp1‐1 (H, J, L, N) and homozygous zmdrp1‐1 (I, K, M, O) plants. Scale bars = 10 µm (H, I, L, M), 2 µm (J, K) and 1 µm (N, O).

DISCUSSION

Compared to previous studies that have investigated the limited number of genes exhibiting dynamic expression during a few stages of anther development, primarily based on microarrays (Ma et al., 2008; Kelliher and Walbot, 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2018), our study provided a detailed transcriptome profile of 10 size‐selected anther groups varying from very early stage (0.2‐mm length) anthers to mature pollen in the Chinese elite maize line Chang7‐2 by RNA‐seq. We identified 26,409 genes, including 1,650 encoding TFs, which are expressed during the various stages of anther development. Among these genes, half (13,675 genes, 675 TF genes) were constantly expressed across the entire process of anther development, while the other half (12,734 genes, 975 TF genes) showed predominant expression in one phase (Figure 2A). These observations are consistent with a previous study that reported about 1,100 TF genes were differentially expressed among different developmental stages in three other maize lines (Jiang et al., 2021).

We compared our dataset to other publicly available RNA‐seq data collected for anthers of the same size in the W23 inbred line (Zhai et al., 2015), which revealed that the two transcriptomes related to same‐size anthers are similar across all developmental stages. These results suggest that the relationship between anther developmental stage and anther length is conserved between different maize inbred lines, which provides a convenient means for gene expression profiling during anther development.

Using very strict selection criteria, we identified 751 genes that are specifically expressed in one of four phases in the inbred line Chang7‐2. With the exception of 144 genes that are not expressed in the anther dataset in inbred line W23, 570 genes (or 75.9% of total) also exhibited specific expression at the same phase as in inbred Chang7‐2 during anther development (Table S7). The genes specifically expressed during the phases of cell division and expansion (36 genes), early meiosis (49 genes), late meiosis (101 genes), pollen maturation (29 genes), and mature pollen (355 genes) will be candidates for future functional genomics studies of maize anthers. In addition, these phase‐specific genes also constitute new marker genes to estimate anther developmental stages in future studies, particularly in mutant anthers where anatomy or functional processes are disrupted. Nevertheless, the exact roles of these phase‐specific genes in maize anther development remain to be determined.

Many male sterility genes have been identified and characterized, and most encode either TFs or proteins involved in meiosis or lipid metabolism (Wan et al., 2019, 2020). Our results suggest that environmentally responsive genes may also be involved in anther development, such as ZmDRP1. Desiccation‐related proteins in resurrection plants mainly promote tolerance to desiccation (Piatkowski et al., 1990; Giarola et al., 2018) while the expression of some of their related family members is also induced by stresses such as heat, cold, and the phytohormone abscisic acid (Bartels et al., 1990; Zha et al., 2013; Giarola et al., 2018). Compared to the known male sterility genes required for pollen wall development, such as ZmAPV1, ZmIPE1, ZmMs30, and ZmMs6021, which are also expressed in the tapetum during the tetrad and uninucleate microspore stages (Chen et al., 2017; Somaratne et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2017; An et al., 2019), zmdrp1 mutants have a distinct phenotype. Here we demonstrated that the pollen wall surface of zmdrp1 mutants was cracked (Figures 5M, O, S11L–O) and the Ubisch bodies were abnormal in the inner surface of anthers (Figures 5I, K, S11H–K). By contrast, the mutants of ZmAPV1, ZmIPE1, ZmMs30, and ZmMs6021 either lack mature pollen grains or exhibit pollen walls without surface cracks but with defects in exine (Chen et al., 2017; Somaratne et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2017; An et al., 2019). Ubisch bodies act as carriers that export sporopollenin precursors from tapetal cells to microspores to form pollen exine (Blackmore et al., 2007); it is possible that this transport process is blocked in zmdrp1 mutants, resulting in the failure of pollen exine to form, leading to male sterility. Accordingly, ZmDRP1 probably has specific roles in regulating the development of the pollen wall, even though its spatiotemporal expression pattern during anther development was similar to that of the genes ZmAPV1, ZmIPE1, ZmMs30, and ZmMs6021. The detailed function(s) and molecular mechanisms of ZmDRP1 in regulating anther development and how the expression of its encoding gene responds to different abiotic stresses will require future study. Moreover, zmdrp1 mutants were phenotypically identical to its fertile siblings in terms of growth, aside from the observed male sterility. This absence of yield penalty suggests that ZmDRP1 may be potentially applied for hybrid maize breeding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and RNA‐seq

The maize (Z. mays) inbred line Chang7‐2 was grown in 2018 in Hainan, China. Anther samples spanning a length range of 0.2–4.0 mm and mature pollen were collected. Each sample consisted of a pool of anthers from at least two plants, and only the upper florets around the central region of each tassel were collected. Mature pollen grains were collected when shed. Total RNA from anther and pollen samples was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The sequencing library was constructed using 1 µg total RNA from each sample. Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq RNA Library Preparation kit (Illumina, USA) and sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq platform, and 150‐bp paired‐end reads were generated.

Read mapping and gene expression analysis

From the raw sequencing data, reads were removed if they: (i) contained adaptor; (ii) had >50% low‐quality bases (Q20); or (iii) contained >10% undetermined bases, using Fastp (Chen et al., 2018). Trimmed reads were aligned to the maize reference genome B73_ AGPv4 (Jiao et al., 2017) by Hisat2 (Kim et al., 2015) with default parameters. Only uniquely mapped reads were used to measure gene expression (i.e., FPKM) by Stringtie (Pertea et al., 2015). The Pearson's correlation coefficient between replicates was calculated to evaluate data quality.

Principle component analysis and hierarchical clustering

Hierarchical clustering was carried out using Log2 (FPKM + 0.01) values for genes expressed in at least one sample during the 10 defined stages of anther development. Correlation coefficients represent the distance between any two samples, and data were plotted with hclust (R package). PCA of the transcriptome data for anther development was carried out using Log2 (FPKM + 0.01) of genes expressed during at least one of the 10 defined stages of anther development by prcomp (R package).

Gene co‐expression and functional enrichment analysis

Gene co‐expression models were constructed using the K‐means method (R package), and the cluster number was determined by the figure of merit approach (Yeung et al., 2001). Functional enrichment categories in co‐expression clusters were analyzed using GoSlim with all genes as background. Based on results from a hypergeometric test, GO terms with false discovery rate values <0.05 were considered significantly enriched.

Identification of anther‐, pollen‐, and phase‐specific gene expression

The anther RNA‐seq dataset from this study was combined with previous datasets for 10 non‐anther tissues (Wang et al., 2009; Davidson et al., 2011; Bolduc et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014) to allow the identification of anther‐, pollen‐, and phase‐specific expressed genes. First, expression data for all samples were normalized by Log2 (FPKM + 0.01). Then, for each gene in a given anther or pollen sample, the z‐score was calculated for the normalized expression of that gene compared to the expression of the same gene in the non‐anther samples. Genes with a z‐score >3 were considered anther‐ or pollen‐specific expressed genes. Phase‐specific genes were selected based on a z‐score >3 in only one phase. After manually removing genes with low expression, the remaining gene set was considered as representing phase‐specific genes.

RT‐qPCR and RNA in situ hybridization

Total RNA from anthers at different developmental stages and from mature pollen was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and then reverse transcribed using the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara, Japan). RT‐qPCR was performed with TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara, Japan) using an Applied Biosystems 7500 system. Tubulin4 was used as the internal standard transcript for normalization. Three replicates were used for each sample. The relevant primer sequences are listed in Table S9.

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described. Fresh Chang7‐2 spikelets collected at different developmental stages were fixed immediately in FAA solution (3.7% formaldehyde, 5% glacial acetic acid, 50% ethanol, v/v/v). The sequences of RNA probes are provided in Table S9. Spikelets were dehydrated, embedded, sliced, pretreated, hybridized, washed and detected as previously described (Cui et al., 2010).

ZmDRP1 knockout mutants edited with the CRISPR/Cas9 system

The zmdrp1 mutants were obtained by CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated genome editing targeting the site shown within the single ZmDRP1 exon (Figure 5A) with a CRISPR/Cas9 vector based on the plasmid p3301‐ubi‐Cas9. Maize embryos were transformed with the CRISPR/Cas9 vectors via Agrobacterium (EHA105)‐mediated transformation as previously described (Ishida et al., 2007). Target‐site sequences for all CRISPR/Cas9‐edited transgenic plants were identified by direct sequencing or cloning/sequencing of PCR products to identify homozygous mutants. The phenotypes of the floral organs including tassels, anthers and pollen were documented by inspecting images acquired with a camera, a stereomicroscope and a scanning electron microscope.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.H., M.H., X.M., and G.Y. performed most of the research on the bench. Y.H. drafted the manuscript. X.M. did all the data analysis. M.H. and G.Y. performed RT‐qPCR analysis, and G.Y. also carried out RNA in situ hybridization. C.W. and S.J. helped do some data analysis and modified the graphs. J.L. gave valuable input. M.Z. designed the experiments, supervised the study, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved of its content.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jipb.13276/suppinfo

Figure S1. Correlation analysis of gene expression levels between replicates

Figure S2. The number of genes expressed among different samples

Figure S3. Validation of RNA‐seq data with known genes

Figure S4. Principal component analysis of the transcriptomes of anther and pollen samples

Figure S5. Transcriptome relationships among anther samples from maize W23 inbred line

Figure S6. Expression patterns of genes in W23 corresponding to the module genes in Chang7‐2

Figure S7. Expression patterns of anther‐specific genes in different staged anthers and non‐anther tissues

Figure S8. Expression patterns for genes randomly selected from the following phases: cell division and expansion (A), meiosis (B), pollen maturation (C), and mature pollen (D)

Figure S9. Expression patterns of ZmDRP1 across anther development based on RNA‐seq data (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads) and reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Figure S10. RNA in situ hybridization of ZmDRP1 in maize anthers across different developmental stages

Figure S11. Characterization of zmdrp1‐2 and zmdrp1‐3 mutants

Figure S12. The Sanger sequencing chromatograms of ZmDRP1 gene in wide‐type and three zmdrp1 mutant lines at the target sites

Figure S13. Morphological comparisons between the wild‐type and zmdrp1 mutants

Table S1. Summary of newly generated RNA‐seq data in this study

Table S2. The fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM) and raw read counts of every gene in different anther sample replicates

Table S3. Gene expression values (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads) in different anther samples

Table S4. List of transcription factors expressed in different anther samples

Table S5. Expression patterns of genes in maize related to anther development

Table S6. The list of anther‐specific genes identified in this study

Table S7. The phase‐specific genes identified during maize anther development

Table S8. The number of co‐expressed transcription factors (TFs) and phase‐specific TFs detected in different development phases of maize anther

Table S9. List of primers used in this study

Table S10. Gene names and their corresponding gene IDs

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mrs. Fengqin Dong from the Key Laboratory of Plant Molecular Physiology and Plant Science Facility of the Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for the preparation of transverse sections, and Dr. Wei Huang from China Agricultural University, for the preparation of 4ʹ,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole staining. We thank Professor Virginia Walbot and Dr. Guo‐Ling Nan of Stanford University, Dr. Chong Teng of Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, Professor Nathan M. Springer of the University of Minnesota, and Associate Professor Haiming Zhao of China Agricultural University for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA24010106) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072075). Raw data were submitted to National Center for Biotechnology Information's Short Read Archive under BioProject accession PRJNA750514.

Biographies

Han, Y. , Hu, M. , Ma, X. , Yan, G. , Wang, C. , Jiang, S. , Lai, J. , and Zhang, M. (2022). Exploring key developmental phases and phase‐specific genes across the entirety of anther development in maize. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 64: 1394–1410.

Edited by: Feng Tian, China Agricultural University, China

REFERENCES

- Adamski, N.M. , Anastasiou, E. , Eriksson, S. , O'Neill, C.M. , and Lenhard, M. (2009). Local maternal control of seed size by KLUH/CYP78A5‐dependent growth signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106: 20115–20120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertsen, M. , Fox, T. , Leonard, A. , Li, B. , Loveland, B. , and Trimnell, M. (2014). Cloning and use of the ms9 gene from maize. US patent US20160024520A1.

- Alves‐Ferreira, M. , Wellmer, F. , Banhara, A. , Kumar, V. , Riechmann, J.L. , and Meyerowitz, E.M. (2007). Global expression profiling applied to the analysis of Arabidopsis stamen development. Plant Physiol. 145: 747–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambawat, S. , Sharma, P. , Yadav, N.R. , and Yadav, R.C. (2013). MYB transcription factor genes as regulators for plant responses: An overview. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 19: 307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An, X. , Dong, Z. , Tian, Y. , Xie, K. , Wu, S. , Zhu, T. , Zhang, D. , Zhou, Y. , Niu, C. , Ma, B. , Hou, Q. , Bao, J. , Zhang, S. , Li, Z. , Wang, Y. , Yan, T. , Sun, X. , Zhang, Y. , Li, J. , and Wan, X. (2019). ZmMs30 encoding a novel GDSL lipase is essential for male fertility and valuable for hybrid breeding in maize. Mol. Plant 12: 343–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi, T. , and Toriyama, K. (2011). Genetic regulation of sporopollenin synthesis and pollen exine development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62: 437–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakate, A. , Orr, J. , Schreiber, M. , Colas, I. , Lewandowska, D. , McCallum, N. , Macaulay, M. , Morris, J. , Arrieta, M. , Hedley, P.E. , Ramsay, L. , and Waugh, R. (2021). Barley anther and meiocyte transcriptome dynamics in meiotic prophase I. Front. Plant Sci. 11: 619404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, D. , Schneider, K. , Terstappen, G. , Piatkowski, D. , and Salamini, F. (1990). Molecular cloning of abscisic acid‐modulated genes which are induced during desiccation of the resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum . Planta 181: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, S. , Wortley, A.H. , Skvarla, J.J. , and Rowley, J.R. (2007). Pollen wall development in flowering plants. New Phytol. 174: 483–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolduc, N. , Yilmaz, A. , Mejia‐Guerra, M.K. , Morohashi, K. , O'Connor, D. , Grotewold, E. , and Hake, S. (2012). Unraveling the KNOTTED1 regulatory network in maize meristems. Genes Dev. 26: 1685–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommert, P. , Lunde, C. , Nardmann, J. , Vollbrecht, E. , Running, M. , Jackson, D. , Hake, S. , and Werr, W. (2005). thick tassel dwarf1 encodes a putative maize ortholog of the Arabidopsis CLAVATA1 leucine‐rich repeat receptor‐like kinase. Development 132: 1235–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau, J. , Baumann, U. , Beasley, J. , Li, Y. , and Johnson, A.A.T. (2016). Identification and molecular characterization of the nicotianamine synthase gene family in bread wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14: 2228–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Zeng, B. , Zhang, M. , Xie, S. , Wang, G. , Hauck, A. , and Lai, J. (2014). Dynamic transcriptome landscape of maize embryo and endosperm development. Plant Physiol. 166: 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. , Zhou, Y. , Chen, Y. , and Gu, J. (2018). fastp: An ultra‐fast all‐in‐one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34: i884–i890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Zhang, H. , Sun, H. , Luo, H. , Zhao, L. , Dong, Z. , Yan, S. , Zhao, C. , Liu, R. , Xu, C. , Li, S. , Chen, H. , and Jin, W. (2017). IRREGULAR POLLEN EXINE1 is a novel factor in anther cuticle and pollen exine formation. Plant Physiol. 173: 307–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigan, A.M. , Unger, E. , Xu, R.J. , Kendall, T. , and Fox, T.W. (2001). Phenotypic complementation of ms45 maize requires tapetal expression of MS45. Sex. Plant Reprod. 14: 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, R. , Han, J. , Zhao, S. , Su, K. , Wu, F. , Du, X. , Xu, Q. , Chong, K. , Theißen, G. , and Meng, Z. (2010). Functional conservation and diversification of class E floral homeotic genes in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant J. 61: 767–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, R.M. , Hansey, C.N. , Gowda, M. , Childs, K.L. , Lin, H. , Vaillancourt, B. , Sekhon, R.S. , de Leon, N. , Kaeppler, S.M. , Jiang, N. , and Buell, C.R. (2011). Utility of RNA sequencing for analysis of maize reproductive transcriptomes. Plant Genome 4: 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- De Storme, N. , and Geelen, D. (2014). The impact of environmental stress on male reproductive development in plants: Biological processes and molecular mechanisms. Plant Cell Environ. 37: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveshwar, P. , Bovill, W.D. , Sharma, R. , Able, J.A. , and Kapoor, S. (2011). Analysis of anther transcriptomes to identify genes contributing to meiosis and male gametophyte development in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 11: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka, N. , Krishnan, K. , Kandpal, M. , Vashisht, I. , Pal, M. , Sharma, M.K. , and Sharma, R. (2020). Transcriptional trajectories of anther development provide candidates for engineering male fertility in sorghum. Sci. Rep. 10: 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, C.R. , Han, G. , Chen, M. , Berg, R.H. , Dunn, T.M. , and Cahoon, E.B. (2008). Loss‐of‐function mutations and inducible RNAi suppression of Arabidopsis LCB2 genes reveal the critical role of sphingolipids in gametophytic and sporophytic cell viability. Plant J. 54: 284–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukanovic, V. , Smith, J. , Lowe, K. , Yang, M. , Gao, H. , Jones, S. , Nicholson, M.G. , West, A. , Lape, J. , Bidney, D. , Falco, S.C. , Jantz, D. , Lyznik, L.A. , et al. (2013). Male‐sterile maize plants produced by targeted mutagenesis of the cytochrome P450‐like gene (MS26) using a re‐designed I‐CreI homing endonuclease. Plant J. 76: 888–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo, M. , Tsuchiya, T. , Hamada, K. , Kawamura, S. , Yano, K. , Ohshima, M. , Higashitani, A. , Watanabe, M. , and Kawagishi‐Kobayashi, M. (2009). High temperatures cause male sterility in rice plants with transcriptional alterations during pollen development. Plant Cell Physiol. 50: 1911–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.M.S. (2007). The indeterminate gametophyte1 gene of maize encodes a LOB domain protein required for embryo sac and leaf development. Plant Cell 19: 46–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, N. , Song, G. , Guan, J. , Chen, K. , Jia, M. , Huang, D. , Wu, J. , Zhang, L. , Kong, X. , Geng, S. , Liu, J. , Li, A. , and Mao, L. (2017). Transcriptome profiling of wheat inflorescence development from spikelet initiation to floral patterning identified stage‐specific regulatory genes. Plant Physiol. 174: 1779–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flütsch, S. , Nigro, A. , Conci, F. , Fajkus, J. , Thalmann, M. , Trtilek, M. , Panzarova, K. , and Santelia, D. (2020). Glucose uptake to guard cells via STP transporters provides carbon sources for stomatal opening and plant growth. EMBO Rep. 21: e49719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, T. , DeBruin, J. , Haug Collet, K. , Trimnell, M. , Clapp, J. , Leonard, A. , Li, B. , Scolaro, E. , Collinson, S. , Glassman, K. , Miller, M. , Schussler, J. , Dolan, D. , Liu, L. , Gho, C. , Albertsen, M. , Loussaert, D. , and Shen, B. (2017). A single point mutation in Ms44 results in dominant male sterility and improves nitrogen use efficiency in maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15: 942–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, V. , Bruchet, H. , Camescasse, D. , Granier, F. , Bouchez, D. , and Tissier, A. (2003). AtATM is essential for meiosis and the somatic response to DNA damage in plants. Plant Cell 15: 119–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarola, V. , Jung, N.U. , Singh, A. , Satpathy, P. , and Bartels, D. (2018). Analysis of pcC13‐62 promoters predicts a link between cis‐element variations and desiccation tolerance in Linderniaceae. J. Exp. Bot. 69: 3773–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubovskaya, I.N. , Hamant, O. , Timofejeva, L. , Wang, C.J.R. , Braun, D. , Meeley, R. , and Cande, W.Z. (2006). Alleles of afd1 dissect REC8 functions during meiotic prophase I. J. Cell Sci. 119: 3306–3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.F. , Talle, B. , and Wilson, Z.A. (2015). Anther and pollen development: A conserved developmental pathway. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57: 876–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger, E. , Kim, S.S. , Lallemand, B. , Geoffroy, P. , Heintz, D. , Azevedo Souza, C. , Heitz, T. , Douglas, C.J. , and Legrand, M. (2010). Analysis of TETRAKETIDE α‐PYRONE REDUCTASE function in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a previously unknown, but conserved, biochemical pathway in sporopollenin monomer biosynthesis. Plant Cell 22: 4067–4083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, D.D. , Hamilton, D.A. , Travis, J.L. , Bashe, D.M. , and Mascarenhas, J.P. (1989). Characterization of a pollen‐specific cDNA clone from Zea mays and its expression. Plant Cell 1: 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley, N. , Cheerambathur, D. , Moyle, M. , Stefanutti, M. , Richardson, A. , Lee, K.Y. , Dumont, J. , Oegema, K. , and Desai, A. (2016). A nucleoporin docks protein phosphatase 1 to direct meiotic chromosome segregation and nuclear assembly. Dev. Cell 38: 463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hihara, Y. , Hara, C. , and Uchimiya, H. (1996). Isolation and characterization of two cDNA clones for mRNAs that are abundantly expressed in immature anthers of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol. Biol. 30: 1181–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honys, D. , and Twell, D. (2004). Transcriptome analysis of haploid male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis . Genome Biol. 5: R85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y. , Pei, Y. , Tian, Y. , Zhang, Z. , Li, K. , Liu, J. , Xiao, S. , Chen, H. , and Liu, J. (2020). IRREGULAR POLLEN EXINE2 encodes a gdsl lipase essential for male fertility in maize. Plant Physiol. 184: 1438–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, H. , Higuchi, K. , Takahashi, M. , Nakanishi, H. , Mori, S. , and Nishizawa, N.K. (2003). Three rice nicotianamine synthase genes, OsNAS1, OsNAS2, and OsNAS3 are expressed in cells involved in long‐distance transport of iron and differentially regulated by iron. Plant J. 36: 366–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Y. , Hiei, Y. , and Komari, T. (2007). Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of maize. Nat. Protoc. 2: 1614–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T. , Nagata, N. , Yoshiba, Y. , Ohme‐Takagi, M. , Ma, H. , and Shinozakif, K. (2007). Arabidopsis MALE STERILITY1 encodes a PHD‐type transcription factor and regulates pollen and tapetum development. Plant Cell 19: 3549–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J. , Zhang, Z. , and Cao, J. (2013). Pollen wall development: The associated enzymes and metabolic pathways. Plant Biol. 15: 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. , An, X. , Li, Z. , Yan, T. , Zhu, T. , Xie, K. , Liu, S. , Hou, Q. , Zhao, L. , Wu, S. , Liu, X. , Zhang, S. , He, W. , Li, F. , Li, J. , and Wan, X. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9‐based discovery of maize transcription factors regulating male sterility and their functional conservation in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19: 1769–1784. 10.1111/pbi.13590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y., Peluso P., Shi J., Liang T., Stitzer M.C., Wang B., Campbell M.S., Stein J.C., Wei X., Chin C.S., Guill K., Regulski M., Kumari S., Olson A., Gent J., Schneider K.L., Wolfgruber T.K., May M.R., Springer N.M., Antoniou E., McCombie W.R., Presting G.G., McMullen M., Ross‐Ibarra J., Dawe R.K., Hastie A., Rank D.R., Ware D. (2017) Improved maize reference genome with single‐molecule technologies. Nature 546: 524–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing, J. , Zhang, T. , Wang, Y. , Cui, Z. , and He, Y. (2019). ZmRAD51C is essential for double‐strand break repair and homologous recombination in maize meiosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20: 5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan, M.B. , and Lim, D.S. (2000). The many substrates and functions of ATM. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, T. , Egger, R.L. , Zhang, H. , and Walbot, V. (2014). Unresolved issues in pre‐meiotic anther development. Front. Plant Sci. 5: 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, T. , and Walbot, V. (2011). Emergence and patterning of the five cell types of the Zea mays anther locule. Dev. Biol. 350: 32–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher T. and Walbot V. (2012). Hypoxia triggers meiotic fate acquisition in maize. Science 337: 345‐348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, T. , and Walbot, V. (2014). Maize germinal cell initials accommodate hypoxia and precociously express meiotic genes. Plant J. 77: 639–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I. , Khan, S. , Zhang, Y. , and Zhou, J. (2021). Genome‑wide analysis and functional characterization of the Dof transcription factor family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Planta 253: 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. , Langmead, B. , and Salzberg, S.L. (2015). HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12: 357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knockenhauer, K.E. , and Schwartz, T.U. (2016). The nuclear pore complex as a flexible and fynamic gate. Cell 164: 1162–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar, D.R. , Drøbak, B.K. , and Staiger, C.J. (2000). Maize profilin isoforms are functionally distinct. Plant Cell 12: 583–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J. , Li, R. , Xu, X. , Jin, W. , Xu, M. , Zhao, H. , Xiang, Z. , Song, W. , Ying, K. , Zhang, M. , Jiao, Y. , Ni, P. , Zhang, J. , Li, D. , Guo, X. , Ye, K. , Jian, M. , Wang, B. , Zheng, H. , Liang, H. , Zhang, X. , Wang, S. , Chen, S. , Li, J. , Fu, Y. , Springer, N.M. , Yang, H. , Wang, J. , Dai, J. , Schnable, P.S. , and Wang, J. (2010). Genome‐wide patterns of genetic variation among elite maize inbred lines. Nat. Genet. 42: 1027–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauga, B. , Charbonnel‐Campaa, L. , and Combes, D. (2000). Characterization of MZm3‐3, a Zea mays tapetum‐specific transcript. Plant Sci. 157: 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Yuan, Z. , Vizcay‐Barrena, G. , Yang, C. , Liang, W. , Zong, J. , Wilson, Z.A. , and Zhang, D. (2011). PERSISTENT TAPETAL CELL1 encodes a PHD‐finger protein that is required for tapetal cell death and pollen development in rice. Plant Physiol. 156: 615–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , and Dawe, R.K. (2009). Fused sister kinetochores initiate the reductional division in meiosis I. Nat. Cell Biol. 11: 1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. , Xu, Y. , Han, G. , Zhou, L. , Ali, A. , Zhu, S. , and Li, X. (2016). Molecular evolution and genetic variation of G2‐Like transcription factor genes in maize. PLoS ONE 11: e0161763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. (2005). Molecular genetic analyses of microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56: 393–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. , Morrow, D.J. , Fernandes, J. , and Walbot, V. (2006). Comparative profiling of the sense and antisense transcriptome of maize lines. Genome Biol. 7: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. , Skibbe, D.S. , Fernandes, J. , and Walbot, V. (2008). Male reproductive development: Gene expression profiling of maize anther and pollen ontogeny. Genome Biol. 9: R181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.J. , Sun, M.H. , Liu, Y.J. , Lu, J. , Hu, D.G. , and Hao, Y.J. (2016). Molecular cloning and functional characterization of the apple sucrose transporter gene MdSUT2 . Plant Physiol. Biochem. 109: 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, I. , Richards, E.J. , and Evans, D.E. (2017). Cell biology of the flant nucleus. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68: 139–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, J.G. , Liang, L. , Jia, P.F. , Wang, Y.C. , Li, H.J. , and Yang, W.C. (2020). Integration of ovular signals and exocytosis of a Ca2+ channel by MLOs in pollen tube guidance. Nat. Plants 6: 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, R. , Armstrong, S.J. , Horlow, C. , Jackson, N.P. , Makaroff, C.A. , Vezon, D. , Pelletier, G. , Jones, G.H. , and Franklin, F.C.H. (2003). The meiotic protein SWI1 is required for axial element formation and recombination initiation in Arabidopsis . Development 130: 3309–3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, S. , Lauterbach, C. , Niedermeier, M. , Barth, I. , Sjolund, R.D. , and Sauer, N. (2004). Wounding enhances expression of AtSUC3, a sucrose transporter from Arabidopsis sieve elements and sink tissues. Plant Physiol. 134: 684–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, D. , Higuchi, K. , Sakamoto, T. , Nakanishi, H. , Mori, S. , and Nishizawa, N.K. (2003). Three nicotianamine synthase genes isolated from maize are differentially regulated by iron nutritional status. Plant Physiol. 132: 1989–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.M. , Egger, R.L. , and Walbot, V. (2015). Chloroplasts in anther endothecium of Zea mays (Poaceae). Am. J. Bot. 102: 1931–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan, G.L. , Zhai, J. , Arikit, S. , Morrow, D. , Fernandes, J. , Mai, L. , Nguyen, N. , Meyers, B.C. , and Walbot, V. (2017). MS23, a master basic helix‐loop‐helix factor, regulates the specification and development of the tapetum in maize. Development 144: 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]