Abstract

LuxR is a ς70 RNA polymerase (RNAP)-dependent transcriptional activator that controls expression of the Vibrio fischeri lux operon in response to an acylhomoserine lactone-cell density signal. We have investigated whether the α-subunit C-terminal domain (αCTD) of RNAP is required for LuxR activity. A purified signal-independent, LuxR C-terminal domain-containing polypeptide (LuxRΔN) was used to study the activation of transcription from the luxI promoter in vitro. Initiation of lux operon transcription was observed in the presence of LuxRΔN and wild-type RNAP but not in the presence of LuxRΔN and RNAPs with truncated αCTDs. We also studied the in vivo role of the RNAP αCTD in activation of lux transcription in Escherichia coli. This enabled a comparison of results obtained with full-length LuxR to those obtained with LuxRΔN. These in vivo studies indicated that both LuxR and LuxRΔN require the RNAP αCTD for activity. The results of DNase I protection studies showed that LuxRΔN-RNAP complexes can bind and protect the luxI promoter, but with less efficacy when the αCTD is truncated in comparison to the wild type. Thus, both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that LuxR-dependent transcriptional activation of the lux operon involves the RNAP αCTD and suggest that αCTD-LuxR interactions may play a role in recruitment of RNAP to the luxI promoter.

Acylhomoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing is common to a number of different gram-negative bacteria (for recent reviews, see references 11, 13, and 24). A well-studied model for this type of genetic regulatory mechanism is control of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence (lux) operon. Two quorum-sensing genes are required for activation of the luminescence operon, i.e., luxI, which encodes an acylhomoserine lactone synthase, and luxR, which encodes an activator of the luminescence genes. The function of the LuxR protein is dependent upon sufficient concentrations of a diffusible acylhomoserine lactone signal. The luxR and luxI genes are adjacent and divergently transcribed, and luxI is the first of the seven genes in the lux operon (10, 20). LuxR represents a family of transcription factors, the LuxR family, which control a variety of genes in many different bacteria (11, 13, 24).

A model for LuxR activation of the lux operon has been developed based primarily on genetic evidence. The 250-amino-acid LuxR sequence appears to be a two-domain polypeptide. Escherichia coli cells expressing the LuxR N-terminal domain bind the signal N-(3-oxohexanoyl) homoserine lactone. The C-terminal domain is required for activation of the lux operon, and its activity is modulated by the N-terminal domain in response to the absence or presence of the signal (3, 4, 21).

Unfortunately, to date it has not been possible to purify and study full-length LuxR in vitro but the interactions of a purified polypeptide containing the LuxR C-terminal domain (LuxRΔN) with lux regulatory DNA and RNA polymerase (RNAP) have been described (22, 23). In E. coli, this C-terminal domain of LuxR activates transcription of the lux operon in an acylhomoserine lactone signal-independent manner (3). A 20-bp region of dyad symmetry, called the lux box, centered at position −42.5 from the luxI transcriptional start site is essential for LuxR activation of the lux operon (6, 7, 9, 12). The minimum upstream region necessary for activation of the luxI promoter includes only the lux box through the start of transcription (7, 23). Based primarily on the location of the lux box, LuxR has been classified as an ambidextrous or class II-type activator of the lux operon (9, 11). By definition, ambidextrous activators are capable of interacting with more than one surface of RNAP. For example, the bacteriophage Mu Mor protein requires the C-terminal regions of both the α and ς70 subunits of E. coli RNAP (1). When the cyclic AMP receptor protein is functioning as an ambidextrous activator, interactions with the distal face of the activator involve the RNAP α-subunit C-terminal domain (αCTD) (2, 17, 18). We have investigated whether the RNAP αCTD is involved in activation of the lux operon by a signal-independent truncated protein, LuxRΔN in vivo and in vitro and LuxR in vivo.

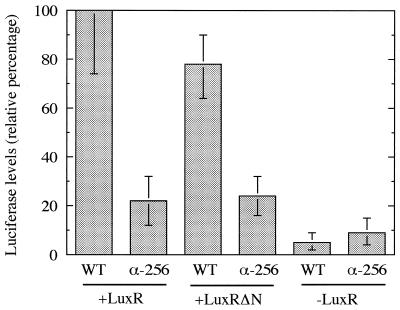

Purified reconstituted mutant RNAPs were used for in vitro studies, and plasmids that directed the overexpression of RNAP αCTDs were used for in vivo studies. The mutant forms of RNAP we have used in this study have αCTD deletions of the C-terminal 73 (α-256) or 94 (α-235) amino acid residues (15, 16). An in vitro system with purified LuxRΔN and RNAP was used to examine luxI transcription initiation as described previously (23). We observed a strong signal corresponding to the luxI transcript in the presence of LuxRΔN and wild-type RNAP, and there was no detectable transcription when reconstituted mutant RNAPs were substituted for the wild type (Fig. 1). In the in vitro transcription analysis, RNA-1 transcription served as an αCTD-independent control. As expected, levels of the RNA-1 transcript were similar with the wild-type or mutant RNAPs (Fig. 1). This indicates that there are regions within the RNAP αCTD that are required for transcription initiation of the lux operon by LuxRΔN. Because similar results were obtained with both the α-235 and α-256 mutant RNAPs, further analysis was performed only with the α-256 mutant RNAP with the smaller 73-amino-acid C-terminal deletion.

FIG. 1.

In vitro transcription from the luxI promoter by LuxRΔN and wild-type RNAP or RNAP with αCTD deletions. Lanes: 1, LuxRΔN and wild-type (WT) RNAP (20 nM); 2, LuxRΔN and α-256 RNAP (40 nM); 3, LuxRΔN and α-235 RNAP (40 nM). The arrow points to the lux mRNA product, and the star marks the RNA-1 mRNA, which served as an internal control for LuxRΔN-independent RNAP activity. Reactions were performed as described previously (23). The template DNA was HindIII-linearized pAMS1300 (1.3 nM), and each reaction mixture contained 10 μM LuxRΔN. RNAPs were purified as described elsewhere (15).

Does this αCTD involvement in LuxRΔN activity reflect the situation with full-length LuxR? Because we could not study full-length, signal-dependent LuxR in vitro, we chose to study the effects of overexpressed mutant αCTDs on LuxR-dependent transcription of the lux operon in recombinant E. coli JM109. A three-plasmid system was employed to carry out these studies, and all of the plasmids and bacterial strains used are described in Table 1. One of the plasmids, pAMS129, a low-copy RSF1010-based vector, coded for an intact copy of the lux operon, including the upstream promoter and regulatory sequences. The second plasmid was (i) one that encoded either ptac-controlled full-length LuxR (pAMS121) or ptac-controlled LuxRΔN (pAMS122) on pSUP102 or (ii) the parent plasmid pSUP102, which served as a no-LuxR control. The third plasmid contained either a lac promoter-controlled wild-type αCTD gene (pLAX185) or a gene coding for α-256, the 73-amino-acid deletion (pLAD256). Thus, in experiments with plasmids coding for the mutant RNAP α subunit, the E. coli strain also contained a chromosomal copy of the α-subunit gene, rpoA, that coded for wild-type RNAP α subunits. Cultures were grown at 30°C in Luria-Bertani broth containing the appropriate antibiotics for plasmid maintenance and 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for induction of the lac and tac promoters, and in experiments with E. coli containing pAMS121, 200 nM N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-dl-homoserine lactone was added. To assess transcription of the lux operon, luciferase activity was measured by previously described procedures (8). Like β-galactosidase, luciferase is a stable enzyme and its activity levels are a reflection of transcriptional activity.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 14 |

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thiΔ(lac-proAB) F′ (traD36 proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15) | 25 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSC300 | luxR in pKK223-3, Apr | 4 |

| pSC156 | luxR with deletion of sequences encoding N-terminal amino acids 2–156 of LuxR in pKK223-3, Apr | 3 |

| pSUP102 | pACYC184, RP4, Cmr Tcr Mob+ | 19 |

| pAMS121 | 1-kb BamHI fragment with ptac-luxR from pSC300 in BamHI site of pSUP102, Cmr Tcs Mob+ | This study |

| pAMS122 | 0.6-kb BamHI fragment with ptac-ΔluxR from pSC156 in BamHI site of pSUP102, Cmr Tcs Mob+ | This study |

| pJE202 | 9-kb SalI fragment of V. fischeri DNA (luxR luxICDABEG) in pBR322, Apr | 10 |

| pJRD215 | Broad-host-range RSF1010-based cosmid vector, Knr Smr Mob+ | 5 |

| pAMS129 | 8-kb XbaI-SalI fragment with luxR′ luxICDABEG from pJE202 in XbaI-SalI sites of pJRD215, Knr Smr Mob+ | This study |

| pLAX185 | rpoA in pINIIIA1, Apr | 15 |

| pLAD256 | rpoA with deletion of sequences encoding C-terminal 73 amino acids of RpoA in pINIIIA1, Apr | 15 |

| pAMS103 | lux intergenic region in pUC19, Apr | 23 |

| pAMS1300 | luxI promoter in pMP7, Apr | 23 |

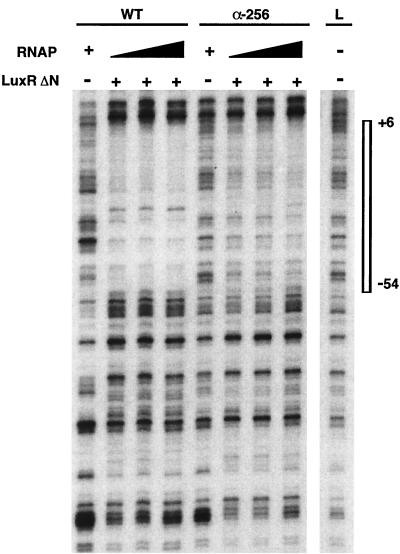

In E. coli expressing either LuxR or LuxRΔN and overexpressing the α subunit with a C-terminal deletion of 73 amino acids, luciferase levels were about 20% of the level observed when the wild-type α subunit was overexpressed (Fig. 2). The growth rates of all four cultures were indistinguishable, and the basal levels of luciferase in cells overexpressing the wild-type α subunit or the mutant α subunit in the absence of LuxR or LuxRΔN were similar. Our results indicate that activation of the lux operon by either LuxR or LuxRΔN involves the RNAP αCTD.

FIG. 2.

Influence of overexpressed α-256 on LuxR and LuxRΔN activities in E. coli. Each value represents the average of two independent experiments, each done in triplicate. The marker bars indicate the range. Cultures containing plasmids expressing the lux operon, either wild-type (WT) RpoA or α-256 RpoA, and either LuxR, LuxRΔN, or no LuxR, as indicated, were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5, and luciferase activity was measured. The luciferase activity in cells containing the wild-type RpoA expression plasmid and the LuxR expression plasmid is given as 100%.

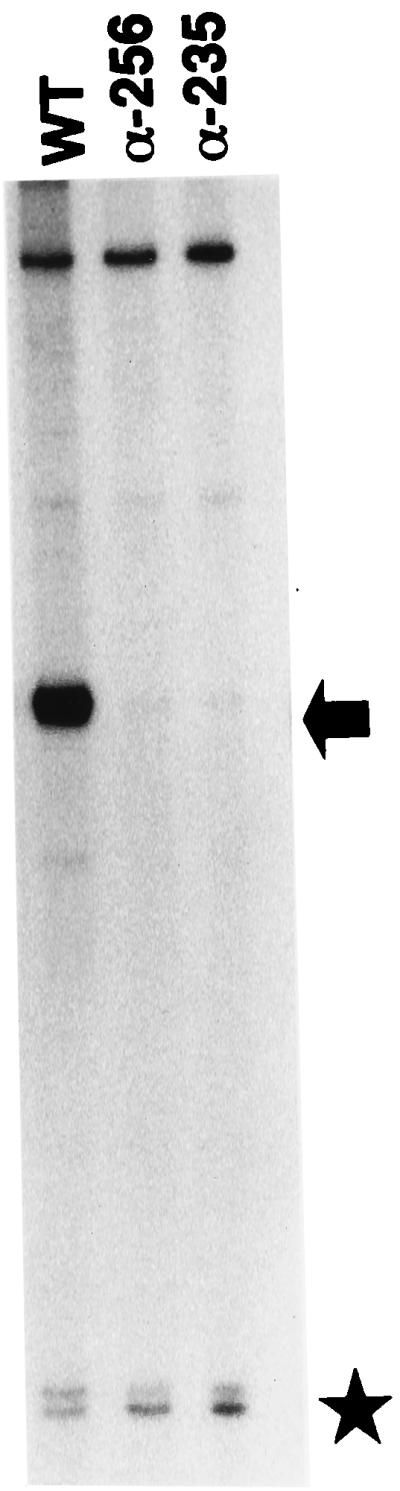

Is the RNAP αCTD involved in LuxR-RNAP binding to the luxI promoter, in transcription initiation by a promoter-bound LuxR-RNAP complex, or in both processes? We have learned from previous investigations that LuxRΔN by itself does not bind to the lux box. DNase I protection experiments show that both LuxRΔN and RNAP are required together for binding to the lux box and the luxI promoter (22, 23). It is not known whether this synergistic binding occurs with full-length LuxR. We performed DNase I protection assays with the wild-type and α-256 mutant RNAPs. A footprint with LuxRΔN and the α-256 RNAP was observed (Fig. 3); however, the binding affinity of these complexes appeared to be lower than the binding affinity of complexes of LuxRΔN with wild-type RNAP. The weak protection was lost over a fourfold range of mutant RNAP concentrations, whereas it was retained with the wild-type RNAP. Although these results do not directly establish whether the observed difference in occupancy of the promoter was due to protein-protein interactions, protein-DNA interactions, or a combination of the two, they do suggest that the α-CTD plays a role in binding of the initiation complex to the promoter.

FIG. 3.

DNase I protection analysis of the luxI promoter (luxI coding strand) by RNAP with α-subunit C-terminal deletions. All lanes contained the γ-32P-labeled 325-bp EcoRI-PstI fragment of the regulatory DNA from pAMS103. The various RNAPs used are designated at the top as follows: WT, wild-type RNAP; α-256, mutant RNAP. DNase I cleavage patterns in the presence of RNAP only, as indicated by plus signs, are shown for both wild-type (20 nM) and α-256 (40 nM) RNAPs. Assays were also done with a range of RNAP concentrations, as indicated by the filled triangles (WT, 10, 20, and 40 nM; α-256, 20, 40, and 80 nM), in the presence of LuxRΔN. Addition of LuxRΔN (5 μM) is indicated by plus signs. The DNase I cleavage pattern for the DNA template is shown in lane L, with the lux box and the luxI −10 promoter region protected by the proteins (positions +6 to −54 in relation to the transcriptional start site) highlighted by the box to the right. Reactions were performed as previously described (23), with two minor modifications; i.e., the reaction volume was reduced from 60 to 30 μl, and the acetylated bovine serum albumin concentration was reduced from 2 to 0.1 mg/ml.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that LuxR activation of the lux operon involves the RNAP αCTD. It is possible that the α-CTD is needed for contact with the activator, LuxR. These protein-protein interactions could facilitate DNA binding by the complex, transcriptional initiation by the bound complex, or both processes. The α-CTD might also interact with the promoter sequences directly, thereby affecting the rate of initiation. The α-256 RNAP strongly reduced transcription in E. coli, even in the presence of wild-type RNAP (Fig. 2). The mutant RNAPs support little or no LuxR-dependent transcription in vitro (Fig. 1), and the αCTD appears to play a part in the RNAP-LuxRΔN interactions required for binding of the two proteins to the lux box-luxI promoter region in vitro (Fig. 3). Taken together, these results support a model in which αCTD-LuxR interactions play a role in recruitment of RNAP to the luxI promoter. Our results are also consistent with the hypothesis that LuxR functions as an ambidextrous activator at the luxI promoter. An ambidextrous activator requires specific interactions with the RNAP αCTD and with other regions of RNAP (1, 18). Further work is necessary to demonstrate whether or what contacts, other than those with the αCTD, LuxR might make with RNAP and to definitively establish the specific role(s) of the α-CTD in the process of transcription initiation from LuxR-dependent promoters during quorum sensing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Parsek, George Stauffer, and Mark Urbanowski for the reagents they provided.

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation to E.P.G. (MCB 9808308) and from the Thomas F. and Kate Miller Jeffress Memorial Trust to A.M.S. A.M.S. was also supported in part by a traineeship from the National Institutes of Health (T32-AI07343).

REFERENCES

- 1.Artsimovitch I, Murakami K, Ishihama A, Howe M M. Transcription activation by the bacteriophage Mu Mor protein requires the C-terminal regions of both α and ς70 subunits of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32343–32348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busby S, Ebright R H. Transcriptional activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2771641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi S H, Greenberg E P. The C-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein contains an inducer-independent lux gene activating domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11115–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi S H, Greenberg E P. Genetic dissection of DNA binding and luminescence gene activation by the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4064–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.4064-4069.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davison J, Heusterspreute M, Chevalier N, Ha-Thi V, Brunel F. Vectors with restriction site banks. V. pJRD215, a wide-host-range cosmid vector with multiple cloning sites. Gene. 1987;51:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devine J H, Countryman C, Baldwin T O. Nucleotide sequence of the luxR and luxI genes and structure of the primary regulatory region of the lux regulon of Vibrio fischeri ATCC 7744. Biochemistry. 1988;27:837–842. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devine J H, Shadel G S, Baldwin T O. Identification of the operator of the lux regulon from the Vibrio fischeri strain ATCC 7744. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5688–5692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunlap P V, Greenberg E P. Control of Vibrio fischeri luminescence gene expression in Escherichia coli by cyclic AMP and cyclic AMP receptor protein. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:45–50. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.45-50.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egland K A, Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: elements of the luxI promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1197–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engebrecht J, Silverman M. Identification of genes and gene products necessary for bacterial bioluminescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4154–4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuqua W C, Winans S C, Greenberg E P. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:727–751. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray K M, Passador L, Iglewski B H, Greenberg E P. Interchangeability and specificity of components from the quorum sensing regulatory systems of Vibrio fischeri and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3076–3080. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.3076-3080.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria. ASM News. 1997;63:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayward R S, Igarashi K, Ishihama A. Functional specialization within the α-subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Igarashi K, Ishihama A. Bipartite functional map of the E. coli RNA polymerase α subunit: involvement of the C-terminal region in transcription activation by cAMP-CRP. Cell. 1991;65:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90553-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu W, Kim Y, Tau G, Heyduk T, Ebright R H. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters: two interactions between CAP and RNA polymerase. Cell. 1996;87:1123–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81806-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhodius V A, Busby S J W. Positive activation of gene expression. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:152–159. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon R, O’Connell M, Labes M, Puhler A. Plasmid vectors for the genetic analysis and manipulation of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1986;118:640–659. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)18106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sitinikov D M, Schineller J B, Baldwin T O. Transcriptional regulation of bioluminescence genes from Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slock J, VanRiet D, Kolibachuk D, Greenberg E P. Critical regions of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein defined by mutational analysis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3974–3979. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3974-3979.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens A M, Dolan K M, Greenberg E P. Synergistic binding of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR transcriptional activator domain and RNA polymerase to the lux promoter region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12619–12623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens A M, Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: essential elements for activation of the luminescence genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:557–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.557-562.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swift S, Throup J P, Williams P, Salmond G P C, Stewart G S A B. Quorum sensing: a population-density component in the determination of bacterial phenotype. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]