Abstract

Background

Volunteering among nursing students has become a valuable resource during an outbreak to help alleviate the strain in nursing staff shortages. However, evidence of willingness to volunteer is scarce, particularly in Asian countries.

Objective

To study Bruneian university nursing students’ willingness to volunteer during a pandemic in Brunei.

Methods

An online cross-sectional study was conducted at Universiti Brunei Darussalam from January to February 2021. A self-administered questionnaire was used to measure willingness factors, including motivational factors, barriers, enablers, and level of agreement to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sub-group inferential analysis was applied.

Results

72 participants were included in this study. 75.0% of whom were willing to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors that influenced the willingness of nursing students to volunteer were marital status (p <0.001), year of study (p <0.001), altruism (p <0.001), personal safety (p <0.001), and knowledge level (p <0.001).

Conclusion

Nursing students are an invaluable resource, and they are highly willing to be part of disaster management. Training and planning should prepare the nursing students for disaster or pandemic readiness and integrated them into the undergraduate nursing curriculum. Align with this, safety aspects of nursing students during volunteering should also be considered, including the provision of childcare assistance, sufficient personal protective equipment, vaccination, and prophylaxis to the volunteers.

Keywords: COVID-19, willingness, nursing, students, volunteerism, online survey, nursing, Brunei Darussalam

During COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) pandemic, nursing students were given the option to volunteer by undertaking extended placements in hospitals to overcome the reduction in manpower and overwhelming patient demand (Hayter & Jackson, 2020; Swift et al., 2020). COVID-19 is a highly infectious respiratory disease that originated in Wuhan, China, on 31 December 2019 (Cervera-Gasch et al., 2020). Due to the contagious nature of the virus, COVID-19 has quickly become a global pandemic, with 129,215,179 confirmed cases worldwide, as stated by the World Health Organization (2021).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, diverse workforces have to temporarily halt their jobs to contain the virus; however, this did not apply to healthcare professionals as they were required to continue their jobs in fighting and prevent the spread of the virus (Pogoy & Cutamora, 2021). This was also applied to nurses as they form the largest sector in a healthcare system; thus, it was impertinent that their availability in the healthcare settings during the pandemic was ensured (Natan et al., 2015). Although registered nurses are important healthcare providers, given their ability to offer direct care and support services, there is usually a nursing shortage (Blackwood, 2017). Disasters such as disease pandemics make nursing shortages more critical as such disasters increase patient demand, often exceeding the operational capacity of healthcare facilities (Blackwood, 2017; McNeill et al., 2020).

Volunteering among nursing students has become a valuable resource during an outbreak. COVID-19 is a highly infectious disease that has quickly become a global pandemic. This pandemic has caused a strain in existing nursing staff shortages due to overwhelming patient demand. Evidence of willingness to volunteer is scarce, particularly in Asian countries. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the willingness of university nursing students to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Factors influencing willingness of nursing students to volunteer: Literature review

Willingness to volunteer - From a Spanish study done on 102 Spanish medical and nursing students from 11 universities, 74.2% were willing to volunteer during a crisis (Cervera-Gasch et al., 2020). Furthermore, a survey in Ireland in the year 2019 also found that 59% of their survey participants were willing to volunteer during an infectious disease outbreak (O’Byrne et al., 2020). This statement is further supported by a cross-sectional study by Yu et al. (2020), in which 85.6% of their nursing and medical student participants would gladly volunteer during the COVID-19 outbreak. Similarly, all 40 Spanish nursing students from the Martin-Delgado et al. (2021) study stated that they were willing to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic. These claims are further evidenced by a study on 711 Denmark medical students, which within two weeks of COVD-19, all master students and 70% of their bachelor students volunteered to work in nine pandemic emergency departments as temporary residents, ventilator therapy assistants, or nursing assistants (Rasmussen et al., 2020). Moreover, Astorp et al. (2020) also found that 81.6% of their sample of Danish medical students wanted to be a part of the healthcare workforce during the pandemic.

Sociodemographic - According to Yu et al. (2020), gender and year of study play a role in influencing willingness to volunteer during a pandemic among nursing students. In a study done in China, it was found that female nursing students were more likely to volunteer during a crisis as compared to male nursing students, and junior nursing students were more willing to volunteer compared to seniors (Yu et al., 2020).

Moral obligation - One of the most common factors that positively influence volunteering among healthcare students is a moral obligation. A study done in the United Kingdom by O’Byrne et al. (2020) reported that 81% of their participants agreed that healthcare professionals have a moral obligation to report for duty during a pandemic, and similarly, health students should be encouraged to volunteer as well. This finding is supported by Yu et al. (2020), which 348 out of 552 Chinese medical students agree that volunteering during a pandemic should be based on professional obligations. Another study that supports these findings is a cross-sectional study done by Huapaya et al. (2015) conducted in Peru, where 77% agree to such statements on moral obligations. Similarly, final-year Spanish nursing students also expressed their feelings of commitment and moral responsibility to society in combatting the COVID-19 pandemic (Gómez-Ibáñez et al., 2020). From these results, it can be said that moral obligations among healthcare students know no nationality, and moral obligation can be seen among these future healthcare professionals worldwide.

Safety - Another important factor influencing nursing students’ decision to volunteer is the provision of necessary personal protective equipment (Martin-Delgado et al., 2021). A Canadian study reported that 77.4% of their participants would volunteer if provided protective garments (Yonge et al., 2010). In addition, the majority of the nursing students in Yonge et al. (2010) agreed that volunteers should be given first access to vaccines and scarce health resources to ensure their safety (Yonge et al., 2010). The strong need that the volunteers expressed for the protective tools are due to the fear of contracting the virus, risking their safety and the safety of their families, and may potentially even lead to death (Astorp et al., 2020). This is supported by a study by Patel et al. (2020), in which British medical students expressed their concern for their safety, especially with the constant media reports of health workers dying due to the virus.

Tasks - In the act of volunteering during a pandemic, it was found that Chinese medical were more willing to volunteer if the tasks given to them were low hazard tasks such as feeding patients, doing administrative work, providing refreshments to staff, working in the community staffing phone lines, or doing volunteering services such as checking on neighbours or buying groceries for elderlies or those who are ill (Yu et al., 2020). In contrast, 83% of 848 medical students in Spain asserted that the roles given to them while volunteering during a pandemic should still be hospital-related (Huapaya et al., 2015).

Preparedness - One factor that negatively influences willingness to volunteer during a pandemic is the lack of preparedness. 65.3% of the sample from Cervera-Gasch et al. (2020) study felt like they were unprepared to attend to patients during an outbreak. Similarly, Spanish nursing students also raised doubts about their preparedness to care for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic (Martin-Delgado et al., 2021). Furthermore, a study on medical students in the United States showed that before completing their disaster preparedness elective, 70% of their students felt unprepared to participate in an emergency such as that of an outbreak, as compared to 11% after the elective was completed (O’Byrne et al., 2020).

As COVID-19 is still considered a new phenomenon, the number of studies conducted regarding the topic is quite scarce. From the studies available, however, it can be seen that the majority of the studies are done in western countries. To address this gap in the literature, this research aimed to study Bruneian university nursing students’ willingness to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional online survey conducted at the Institute of Health Sciences (IHS), Universiti of Brunei Darussalam, from January to February 2021.

Sample/ Participants

Considering the small number of nursing students (approximately 100 students), all the nursing students were recruited. The criteria for participants to be eligible in the study included: 1) students undertaking the nursing degree program, 2) students studying in IHS, UBD, 3) enrolled in IHS during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students enrolled outside of UBD such as PB and IBTE and are taking other health sciences programs such as Midwifery, Medicine, Dentistry, Biomedical Sciences, and Pharmacy were not included as part of the sample.

Instrument

The English-language online questionnaire was adapted from Blackwood (2017), a 26-item instrument that measures the willingness of volunteering during disasters or public health emergencies. The tool is validated by the original developer and is available in the public domain via its published article (Blackwood, 2017). Relevant demographic information such as gender, age, marital status, and year of study was collected, along with motivational factors to enrol in nursing, barriers, enablers, and level of agreement of nursing students to be encouraged to volunteer during a disaster.

Data Collection

Considering the small population of IHS with only approximately 100 students, all eligible nursing students in IHS were recruited for the study using the participant selection method. As this study involved human samples, approval from IHSREC was needed before data collection was commenced. After the approval was obtained, the list of students’ email addresses was requested from the University Liaison Office/IHS administration office. The questionnaire was then sent to the students via their webmail. The questionnaire was done through an online platform due to the ongoing COVID-19 situation in which face-to-face contact should be reduced to a minimum.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) was computed to describe the demographic and outcome variables. Sub-group analysis (Fisher’s exact test) was applied to determine the association of outcome variable (willingness to volunteer) towards motivational factors, barriers, enablers, and level of agreement, and demographic factors. All analysis was performed using RStudio 1.1.383.

Ethical Consideration

The research procedure was assessed by the ethics committee of Universiti Brunei Darussalam (UBD/PAPRSB IHSREC/2020/63). Digital consent was obtained prior to joining the study.

Results

Sociodemographic Data

A total of 72 nursing students from Universiti Brunei Darussalam were included, representing a response rate of 65.5%. Out of the 72 participants, 54 (75.0%) showed that they were willing to volunteer in the event of a pandemic. The majority of the participants are first-year students (40.3%), followed by second-year (20.8%), third-year (19.4%), and fourth-year (18.1%). Most (77.8%) of the participants are female, 65.0% around the age range of 18-22 years old, and 88.9% are single (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic factors in association with willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 among nursing students (n = 72)

| Willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 |

p-value a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Total n (%) | ||

| Overall | 54 (75.0) | 18 (25.0) | 72 (100.0) | |

| Age | 0.307 | |||

| 18 – 22 | 33 (70.3) | 13 (27.7) | 47 (65.3) | |

| >22 | 13 (52.0) | 11 (44.0) | 25 (34.7) | |

| Gender | 0.077 | |||

| Female | 39 (69.6) | 15 (30.4) | 56 (77.8) | |

| Male | 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.2) | 16(22.2) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Single | 40 (62.5) | 23 (37.5) | 64 (88.9) | |

| Married | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 7 (11.1) | |

| Year | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 21 (72.4) | 8 (27.6) | 29 (40.8) | |

| 2 | 8 (53.3) | 6 (46.7) | 15 (21.1) | |

| 3 | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) | 14 (19.7) | |

| 4 | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 13 (18.3) | |

Fisher’s exact test n = frequency % = percentage

In terms of willingness to volunteer, there was a significant association between years of study and marital status. The participants who were married (85.7%) were more willing to volunteer (p <0.001), and participants in their first year of study (72.4%) were more willing to volunteer compared to those who were in their second year (53.3%) (p <0.001) and also was more willing than third and fourth-year students. There were no significant differences in age and gender concerning nursing students volunteering during the pandemic (Table 1).

Motivational factor in enrolling in nursing

There was a significant association between motivational factors and willingness to volunteer (p <0.001). We observed that the highest motivational factor for the participants to enrol in nursing, related to willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 was because of job security (75.0%), followed by helping others to cope with illness (74.1%), earning a good salary (73.0%), giving their life a sense of meaning (72.4%), they have a calling (71.4%), wanting to work in a caring occupation, (71.4%), job flexibility (71.4%), wanting to help people (69.2%), feel that they can advance in the field of healthcare (68.0%), interested in science (66.0%), and lastly because the flexible educational requirements permit them to finish schooling quickly (52.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Motivational factors to enrol in nursing associated with willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 among nursing students (n=72)

| Motivational factors (I want to become a nurse because…) | Willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Total n (%) | ||

| The occupation offers job security | 33 (75.0) | 11 (25.0) | 44 (61.1) | <0.001 |

| I want to help others cope with illness | 43 (74.1) | 15 (25.9) | 58 (80.6) | <0.001 |

| I can earn a good salary | 27 (73.0) | 10 (27.0) | 37 (51.4) | <0.001 |

| Nursing gives my life a sense of meaning | 34 (72.3) | 13 (27.7) | 47 (65.3) | <0.001 |

| I have a calling | 20 (71.4) | 8 (28.6) | 28 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| I want to work in a caring occupation. | 40 (71.4) | 16 (28.6) | 56 (77.8) | <0.001 |

| The occupation offers job flexibility | 25 (71.4) | 10 (28.6) | 35 (48.6) | <0.001 |

| I want to help people | 45 (69.2) | 20 (30.8) | 65 (90.3) | <0.001 |

| I feel that I can advance in the field of healthcare | 34 (68.0) | 16 (32.0) | 50 (69.4) | <0.001 |

| I am interested in science | 35 (66.0) | 18 (34.0) | 53 (73.6) | <0.001 |

| The flexible educational requirements permit me to finish my schooling quickly | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | 19 (26.4) | <0.001 |

a Fisher’s exact test n = frequency % = percentage

Barriers

When examining the factors that prevent the participants from volunteering during a pandemic, the highest barrier found was having responsibility for dependent children (53.6%). Fear for personal safety and well-being (57.5%), type of disaster (60.0%), fear for the safety and well-being of family members (65%), lack of disaster training and education (65.6%), and being a student nurse (67.7%) have also been found to have a significance in acting as barriers for the nursing students from volunteering during COVID-19 (p <0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Barriers associated with willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 among nursing students (n=72)

| Willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Total n (%) | |

| Being a nursing student | 21 (67.7) | 10 (32.3) | 31 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| Lack of disaster training and education | 40 (65.6) | 21 (34.4) | 61 (84.7) | <0.001 |

| Fear for the safety and well-being of my family members | 39 (65.0) | 21 (35.0) | 60 (83.3) | <0.001 |

| Type of disaster | 24 (60.0) | 16 (40.0) | 40 (55.6) | <0.001 |

| Fear for my personal safety and well-being | 23 (57.5) | 17 (42.5) | 40 (55.6) | <0.001 |

| Responsibility for dependent children | 15 (53.6) | 13 (46.4) | 28 (38.9) | <0.001 |

a Fisher’s exact test n = frequency % = percentage

Enablers

The results shown in Table 4 indicate that having access to safe reliable childcare (76.3%), the availability of vaccines and prophylaxis to the volunteers (71.7%), and their family members (71.2%), the provision of appropriate personal protective equipment (70.5%), having more knowledge about disaster response (70.5%), knowing their families would be safe (69.8%), and knowing they would be safe from illness or harm (67.2%) are positively correlated to the willingness of the participants to volunteer.

Table 4.

Situational factors associated with willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 among nursing students (n=72)

| Factors that increase willingness | Willingness to volunteer during COVID-19 |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Total n (%) | ||

| If I had access to safe reliable childcare | 29 (76.3) | 9 (23.7) | 38 (52.8) | <0.001 |

| If vaccines and prophylaxis were available to me | 43 (71.7) | 17 (28.3) | 60 (83.3) | <0.001 |

| If vaccines and prophylaxis were provided to my family members | 42 (71.2) | 17 (28.8) | 59 (81.9) | <0.001 |

| If I were provided with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) | 43 (70.5) | 18 (29.5) | 61 (84.7) | <0.001 |

| If I had more knowledge about disaster response | 43 (70.5) | 18 (29.5) | 61 (84.7) | <0.001 |

| If I knew my family would be safe | 44 (69.8) | 19 (30.2) | 63 (87.5) | <0.001 |

| If I knew I would be safe from illness or harm | 39 (67.2) | 19 (32.8) | 58 (80.6) | <0.001 |

a Fisher’s exact test n = frequency % = percentage

Encourage nursing students to volunteer

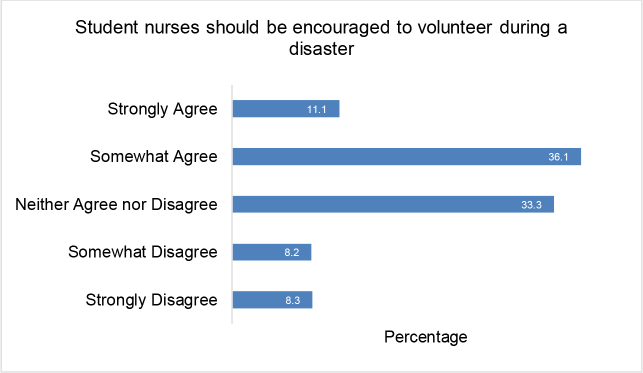

The research findings show that 47.2% of respondents agreed (strongly agree 11.1%; somewhat agree 36.1%) that nurses should be encouraged to volunteer during a disaster. Conversely, few participants (16.5%) disagreed (strongly disagree 8.3%; somewhat disagree 8.2%) that nursing students should be encouraged to volunteer during a disaster, and 33.3% neither agree nor disagree (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of responses for the level of agreement on encouraged to volunteer during a disaster (n=72)

Discussion

With the presence of a pandemic, staff nurses are stretched thin due to the lack of staff, which is why recruiting volunteers, especially nursing students, is recommended to overcome this problem (Blackwood, 2017; Hayter & Jackson, 2020; Iserson, 2020; McNeill et al., 2020; Swift et al., 2020; Quisao et al., 2021). However, from previous research, it can be observed that obtaining volunteers during an emergency can indeed be a challenge (Blackwood, 2017). Therefore, the key objective of this paper was to assess the factors that may influence the willingness of university nursing students to volunteer during a pandemic.

Prevalence of willingness to volunteer

Overall, the prevalence of university nursing students volunteering in Brunei was 75.4%. The findings were similar to a study by Blackwood (2017) among bachelor nursing students in the United States; however, Blackwood (2017) achieved a higher percentage of willingness (86.5%) as compared to the present study. Additionally, these results were similar to studies conducted on medical students from China, and Peru, where the overall willingness to volunteer during a pandemic was 63% and 77%, respectively (Huapaya et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2020). The difference in prevalence between these countries may be due to the different severity of the situations presented to the nursing students during the survey. For example, Blackwood (2017) had the highest prevalence of willingness to volunteer due to the situation presented to the students, which were general emergencies, admittedly the most varied and least deadly situation from the rest. For Huapaya et al. (2015) study, it was conducted during avian influenza, which is a slightly less deadly viral infection than the coronavirus, reaching only a total death count of 455 from the year 2003-2020 (World Health Organization, 2020). For Yu et al. (2020) and the present study, however, yielded the least prevalence of willingness to volunteer among student nurses due to the deadly nature of the COVID-19 infection. This is evidenced by the high death count of 2,804,120 from December 2019 to March 2021 (World Health Organization, 2021).

Besides the severity of the situation, demographic data is also one of the main predictors of willingness to volunteer. The results of this study demonstrated that marital status plays a role in affecting willingness to volunteer among nursing students; specifically, participants who were married were more likely to volunteer during a pandemic (85.7%). The reason behind this may be because these participants are among those who were taking their nursing degree while in-service, which means that they have more knowledge and experience in volunteering during emergencies.

Furthermore, as seen in Table 1, the willingness to volunteer during a pandemic decreased with seniority. This trend is similar to the results in Yu et al. (2020), in which junior medical students were more willing to volunteer during a pandemic as compared to their seniors.

Among the participants, women had a higher response rate of 77.8% compared to men, which is a common trend found in various studies due to the higher number of women than men entering health-related courses (Dyson et al., 2017). Interestingly, despite the higher response rate of women than men, the results showed that gender has no significance in influencing nursing students to volunteer during a pandemic, as men were as likely willing to volunteer during a pandemic as women (p=0.077). These findings, however, differ from a study conducted by Yu et al. (2020) on Chinese medical students who noted that female students were more likely to volunteer during COVID-19 than their male colleagues.

Factors that promote volunteerism nursing students

From the results of the present study, multiple factors were significant in promoting a sense of volunteerism among student nurses, which have been grouped into altruism, family, and personal reasons.

First of all, altruism is one of the most significant motivating factors for nursing students to volunteer during a pandemic (Blackwood, 2017; Gouda et al., 2020; O’Byrne et al., 2020). This can also be seen in the results of this study, in which almost half of the participants agreed that nursing students should be encouraged to volunteer in the case of an emergency such as a pandemic. Moreover, traits of altruism can be seen in the participants that were willing to volunteer by their intentions to join the nursing workforce due to reasons such as wanting to care for others (71.4%) and helping people (69.2%), especially those who are suffering from illnesses (74.1). These traits of altruism are not only limited to Bruneian nursing students as even American nursing students that were willing to volunteer from Blackwood (2017) study also entered nursing due to their intentions in wanting to help people, help others cope with illness, and working in a caring occupation.

Secondly, from the results of this study and Blackwood (2017), another motivating factor for nursing students to volunteer is the reassurance for the safety of their families, including the availability of safe childcare and the provision of vaccines for their families. Furthermore, the majority (92%) of the Spanish medical and nursing students from Cervera-Gasch et al. (2020) study also expressed their concerns regarding the safety of their families in the event of a pandemic. The reason behind this may be because while volunteering, the nursing students would be putting their lives on the line and may not be able to return home to care for their families and children. If the volunteers were allowed to go home to rest, there is also the risk of infecting their families, which is why providing the family members of the volunteers with vaccine and prophylaxis may be required to ease the worries of the volunteers, hence increasing their willingness to volunteer (Cervera-Gasch et al., 2020).

Finally, guaranteeing the safety of the volunteers by providing personal protective equipment and giving access to volunteers have been found to promote volunteerism among student nurses. From the present study, 67.2% of the sample population expressed their concerns regarding their safety if they were to volunteer due to the contagious and deadly nature of the virus. To overcome this, providing access to vaccines and prophylaxis to the volunteers has been found to increase the willingness of student nurses to volunteer, as evidenced by Blackwood (2017). In addition to the provision of vaccines as a means of personal defence against the pandemic, providing the volunteers with Personal Protective Equipment has also been found to increase the willingness of nursing students to volunteer as it decreases the risk of the volunteers contracting the disease (Blackwood, 2017). With the provision of these limited health resources given to the volunteers as a priority, it increases the willingness of nursing students to volunteer during a disaster as they are given the tools to protect themselves from the deadly infection

Factors that inhibit volunteerism in nursing students

Similar to the presence of enabling factors, multiple factors inhibited volunteerism among student nurses, which have been grouped into family factors, personal safety, and knowledge.

From the results of this study, it was found that family was the biggest barrier for nursing students from volunteering during the COVID-19 pandemic, which included having the responsibility of dependent children (53.6%). Blackwood (2017) had similar findings, where willingness to volunteer and have dependent children were negatively correlated, indicating that having dependent children decreased the willingness of the participants from volunteering during a pandemic. This may be the reason behind safe reliable childcare being the highest enabler for nursing students to volunteer. Furthermore, fear for the safety of their families also inhibited volunteerism among nursing students, as evidenced in the results of this study (65.0%). The results align with Cervera-Gasch et al. (2020), where 92% of their Spanish medicine and nursing students admitted that they were afraid of infecting their families. Moreover, Blackwood (2017) also had similar findings where 73.6% of their participants were less likely to volunteer due to the fear for the safety of their families.

Another barrier identified for willing to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic is fear of personal safety (Blackwood, 2017; Cervera-Gasch et al., 2020). Out of the 72 participants in this study, only 57.5% of them were willing to volunteer during a pandemic due to fear of their safety. Similarly, only 50.9% of participants from Blackwood (2017) were willing to volunteer during an emergency due to the same reasons. Additionally, participants (38.9%) from Cervera-Gasch et al. (2020) also admitted that they were afraid of being infected by the deadly virus of COVID-19. The reason behind the concerns may be due to the high number of infected cases among the healthcare team, such as that in Spain, where 14% of the confirmed cases were health workers (Iserson, 2020).

Finally, the lack of disaster education has also been identified as an inhibiting factor for volunteerism among nursing students. This may be the reason behind the participants claiming that being a student also acts as a barrier, as they may feel that they are not confident enough and are unprepared to volunteer during such a critical situation. This is supported by AlSaif et al. (2020) where they found a positive correlation between willingness and mean total perceived-competence score. Cervera-Gasch et al. (2020) also found that 63% of their respondents admitted that they were not ready to attend patients during a pandemic as they did not feel confident to do so due to lack of required knowledge, which may even potentially risk the safety of the patients and the students, as reported by Mortelmans et al. (2015). Similarly, O’Byrne et al. (2020) also stated that 70% of their participants, consisting of American medical students, felt unprepared to participate during a pandemic before they commenced their disaster management elective; however, the number was reduced to 11% after their elective was completed.

Strategies and recommendations

Therefore, to increase the willingness of nursing students to volunteer during an outbreak, institutions may need to introduce disaster management in their nursing curriculum to provide the students with the knowledge and prepare their students for future outbreaks.

Furthermore, the Ministry of Health could also contribute to increasing the willingness of university nursing students to volunteer during future disasters by providing adequate personal protective equipment, vaccination, and prophylaxis to ease the worries of the volunteers from contracting the virus. Moreover, if personal protective equipment is inadequate, and vaccination and prophylaxis are unavailable yet, the health ministry could provide staff houses for the volunteers to reduce their contacts with their families, reducing the risk of spreading the virus to the families of the volunteers (Astorp et al., 2020; Martin-Delgado et al., 2021).

Moreover, to overcome the concern of the volunteers for their dependent children at home, volunteers who have no background in healthcare could take the task of providing childcare assistance to the volunteers, as suggested by (Lazarus et al., 2020).

Future researchers have the potential to further this study by identifying the difference in volunteerism between university nursing students attending Universiti Brunei Darussalam and diploma nursing students attending Politeknik Brunei. Furthermore, researchers could further study the difference in results between degree nursing students from A-levels, post-diploma students, and in-service students.

Implications of the study

The level of willingness to volunteer among student nurses in Brunei was high; however, the preparedness and readiness planning is still non-existent. Nursing students are a valuable resource that needs to be tapped. Therefore, proper and systematic training as a volunteer during disasters and pandemics should be part of the nursing curriculum and collaboration with nursing practitioners, particularly in their latest preparedness training nationally, regionally, or internationally.

Limitation of the study

This study is subjected to non-response bias; though participants were recruited using the participant selection method, there were still chances that participants might refuse to participate when there was considerable refusal or non-responses in collected data (>10%), the results will be biased. To avoid non-response bias, the participants were given 2 to 3 reminders and informed about how valuable their contribution is and checking if the participants had completed the data during data collection. Moreover, the timing of the research may also act as a limitation due to the questionnaire being distributed when the COVID-19 situation was already stable in Brunei and no longer posed as a direct threat to the country.

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite the lack of experience, knowledge, and dangers of working as a front-liner during the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing students were willing to volunteer to help alleviate the strain in staffing. A few factors were found to influence the willingness of nursing students to volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as marital status, year of study, altruism, family factors, personal safety, and knowledge. To increase the willingness of nursing students to volunteer during a future pandemic, institutions must consider including disaster management as part of their nursing course curriculum to help the students prepare for future disasters. Moreover, the Ministry of Health also has to take into consideration providing safe reliable childcare, sufficient personal protective equipment, vaccination, and prophylaxis provision to the volunteers to help increase the willingness of university nursing students to volunteer in the future.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the nursing students who participated in this study for contributing some of their time to answer the survey questionnaire.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, agreed to submit to the current journal, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Authors’ Biographies

Amal Atiqah Hamizah Hj Abdul Aziz is an undergraduate final year nursing student in PAPRSB Institute of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam.

Khadizah H. Abdul-Mumin, PhD is a Senior Assistant Professor in PAPRSB Institute of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam.

Hanif Abdul Rahman, PhD is a Lecturer in PAPRSB Institute of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon reasonable request to the authors.

References

- AlSaif, H. I., AlDhayan, A. Z., Alosaimi, M. M., Alanazi, A. Z., Alamri, M. N., Alshehri, B. A., & Alosaimi, S. M. (2020). Willingness and self-perceived competence of final-year medical students to work as part of the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of General Medicine, 13, 653-661. 10.2147/IJGM.S272316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astorp, M. S., Sørensen, G. V. B., Rasmussen, S., Emmersen, J., Erbs, A. W., & Andersen, S. (2020). Support for mobilising medical students to join the COVID-19 pandemic emergency healthcare workforce: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open, 10(9), e039082. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood, K. (2017). Factors that affect nursing students’ willingness to respond to disasters or public health emergencies. (Dissertation), Bachelor of Arts/Communication Arts Public Relations, University of West Florida, Pensacola, FL. Retrieved from https://shareok.org/bitstream/handle/11244/299566/Blackwood_okstate_0664D_15281.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- Cervera-Gasch, Á., González-Chordá, V. M., & Mena-Tudela, D. (2020). COVID-19: Are Spanish medicine and nursing students prepared? Nurse Education Today, 92, 104473. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, S. E., Liu, L., van den Akker, O., & O’Driscoll, M. (2017). The extent, variability, and attitudes towards volunteering among undergraduate nursing students: Implications for pedagogy in nurse education. Nurse Education in Practice, 23, 15-22. 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Ibáñez, R., Watson, C., Leyva-Moral, J. M., Aguayo-González, M., & Granel, N. (2020). Final-year nursing students called to work: Experiences of a rushed labour insertion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Education in Practice, 49, 102920. 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouda, P., Kirk, A., Sweeney, A.-M., & O’Donovan, D. (2020). Attitudes of medical students toward volunteering in emergency situations. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 14(3), 308-311. 10.1017/dmp.2019.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, M., & Jackson, D. (2020). Pre‐registration undergraduate nurses and the COVID‐19 pandemic: Students or workers? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(17-18), 3115-3116. 10.1111/jocn.15317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huapaya, J. A., Maquera-Afaray, J., García, P. J., Cárcamo, C., & Cieza, J. A. (2015). Knowledge, practices and attitudes toward volunteer work in an influenza pandemic: Cross-sectional study with Peruvian medical students. Medwave, 15(4), e6136-e6136. 10.5867/medwave.2015.04.6136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iserson, K. V. (2020). Augmenting the disaster healthcare workforce. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 21(3), 490-496. 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, G., Mangkuliguna, G., & Findyartini, A. (2020). Medical students in Indonesia: An invaluable living gemstone during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 32(3), 237-241. 10.3946/kjme.2020.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Delgado, L., Goni-Fuste, B., Alfonso-Arias, C., De Juan, M. A., Wennberg, L., Rodríguez, E., … Martin-Ferreres, M. L. (2021). Nursing students on the frontline: Impact and personal and professional gains of joining the health care workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Journal of Professional Nursing, 37(3), 588-597. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, C., Alfred, D., Nash, T., Chilton, J., & Swanson, M. S. (2020). Characterization of nurses’ duty to care and willingness to report. Nursing Ethics, 27(2), 348-359. 10.1177/0969733019846645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortelmans, L. J. M., Bouman, S. J. M., Gaakeer, M. I., Dieltiens, G., Anseeuw, K., & Sabbe, M. B. (2015). Dutch senior medical students and disaster medicine: A national survey. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 8(1), 1-5. 10.1186/s12245-015-0077-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natan, M. B., Zilberstein, S., & Alaev, D. (2015). Willingness of future nursing workforce to report for duty during an avian influenza pandemic. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 29(4), 266-275. 10.1891/1541-6577.29.4.266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Byrne, L., Gavin, B., & McNicholas, F. (2020). Medical students and COVID-19: The need for pandemic preparedness. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(9), 623-626. 10.1136/medethics-2020-106353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J., Robbins, T., Randeva, H., de Boer, R., Sankar, S., Brake, S., & Patel, K. (2020). Rising to the challenge: Qualitative assessment of medical student perceptions responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Medicine, 20(6), e244-e247. 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogoy, J. M., & Cutamora, J. C. (2021). Lived experiences of Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW) nurses working in COVID-19 intensive care units. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(3), 186-194. 10.33546/bnj.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quisao, E. Z. S., Tayaba, R. R. R., & Soriano, G. P. (2021). Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among student nurses in Manila, Philippines: A cross-sectional study. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(3), 203-209. 10.33546/bnj.1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, S., Sperling, P., Poulsen, M. S., Emmersen, J., & Andersen, S. (2020). Medical students for health-care staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 395(10234), e79-e80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30923-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift, A., Banks, L., Baleswaran, A., Cooke, N., Little, C., McGrath, L., … Tomlinson, A. (2020). COVID‐19 and student nurses: A view from England. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 10.1111/jocn.15298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020). Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cumulative-number-of-confirmed-human-cases-for-avian-influenza-a(h5n1)-reported-to-who-2003-2020

- World Health Organization . (2021). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Retrieved from Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/

- Yonge, O., Rosychuk, R. J., Bailey, T. M., Lake, R., & Marrie, T. J. (2010). Willingness of university nursing students to volunteer during a pandemic. Public Health Nursing, 27(2), 174-180. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, N.-Z., Li, Z.-J., Chong, Y.-M., Xu, Y., Fan, J.-P., Yang, Y., … Zhang, M.-Z. (2020). Chinese medical students’ interest in COVID-19 pandemic. World Journal of Virology, 9(3), 38-46. 10.5501/wjv.v9.i3.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon reasonable request to the authors.