Abstract

Tourism is a current and global industry that has a multidimensional impact on destinations. As an emerging industry, it has an immense contribution to make to the development of the local community if all stakeholders participate in a responsible manner. The social impact of tourism is, among other things, one that needs the attention of scholars. The social impact of tourism is immense and diverse, and it is embedded with other tourism impacts. So, studying it is very essential to managing tourism in a responsible way. To address the stated objective, mixed research approaches were used. The result of the study indicated that tourism has both positive as and negative impacts on tourist destinations. The positive social impact of tourism was expressed in moderate terms and stated in terms of the expansion of hotels, road transportation, air transportation, electricity, internet, banking, and other infrastructures. The negative social impact was expressed in small terms and conveyed in terms of the unequal access to the aforementioned social services, the expansion of prostitution, the persistence of theft and illicit trade in heritage, and the random adoption of the lifestyles and manners of tourists by residents.

Keywords: Tourism, Social, Positive, Negative, Impact, Destination communities

1. Introduction

Tourism is a flourishing industry in terms of growth and economic importance in almost all nations of the world. It generated $8.8 trillion for the global economy in 2018, which is equivalent to 10.4% of global GDP. The industry grew by 3.9% in 2018, more rapidly than the international economy's growth of 3.2%. It overtook total economic growth of the world for eight consecutive years. The tourism sector was the second fastest-growing sector in 2018, following manufacturing, which grew by four percent [1]. It accounts 10.0% of all employment opportunities. The sector has created one in five of all net new jobs created across the globe over the past five years. Different studies' estimates indicate that there will be 100 million new jobs created across the world over the next ten years in this sector [2].

Tourism is a social, cultural, economic, and environmental phenomenon that affects every aspect of human life [3]. Jaafar, Ismail and Rasoolimanesh (3–40) illustrated the social and cultural impacts of tourism as the mechanism by which tourism effects modifications “in the value systems, individual behaviors, family relationships, collective lifestyles, moral conduct, creative expressions, traditional ceremonies, and community organizations of destination communities” [4].

The significance of studying residents' perceptions of the impact of tourism is considerable when it comes to the fruitful development of tourism, in addition to the enhancement of local support for tourism development and the fulfilment of host communities. Several authors agree that tourism as an emerging industry has an impact on the host communities' economies, social cultures, and environment. Tourism tends to be advantageous through enhancing the economy, creating more natural and cultural attractions, and helping protect these attractions [5,6]. It was also recommended that the residents’ overall well-being and quality of life be considered for an in-depth understanding of their perceived social impacts of tourism, thus allowing for the development of appropriate management strategies to promote behaviors in support of tourism development [7].

Ethiopia has a long history in the tourism industry. Ethiopia is known as the “Origin of Humanity” and is Africa's only uncolonized country. So far, it has 12 UNESCO-recognized world heritage sites. Regardless of its potential, the country's performance in the tourism sector has not developed as expected. In terms of travel and tourism competitiveness in all aspects, Ethiopia ranked 118th out of 141 countries in 2015 [8].

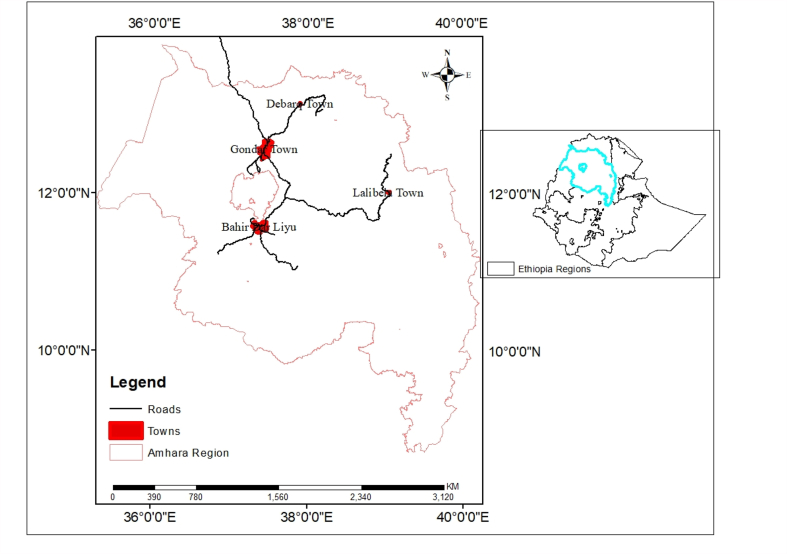

Research in relation to communities' perceptions of the social impact of tourism and its contribution to sustainability in tourism development in Ethiopia in general and in the Amhara region in particular is scarce. There are few and fragmented research studies about tourism that focuses on the historical development of tourism [[9], [10], [11]]. There are research outputs on the ecotourism potential of the Lake Tana Region that do not address its multidimensional issues [12,13]. There are research findings on the Semien National Park that give focus to the impact and challenges of tourism development in and around the park [14,15]. Thus, these studies did not address the social impact of tourism in a comprehensive manner. As such, as far as the knowledge of this researcher is concerned, there is a lacuna of knowledge regarding public perception regarding the social impact of tourism in Amhara Regional State. This research is intended to address the local communities’ perceptions of the social impact of tourism. Thus, the study is guided by the following research questions.

-

•

To what degree are the local communities' perceptions influenced by the positive social impact of tourism?

-

•

To what extent are the local communities' perceptions affected by the negative impacts of tourism and its implications?

-

•

To what extent does tourism create social harmony by creating conducive social services at tourists' destinations?

1.1. The social impacts of tourism and its contribution to promote

1.1.1. Sustainable development

Sustainable development and sustainable tourism are related ideas. The World Commission on Environment and Development defined sustainable development as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. At the moment, this concept has become inclusive and given focus to ‘poverty eradication, changing consumption and production patterns, and managing the natural base for economic and social development rather than purely ecological matters [16].

To make tourism more sustainable and to avoid mass tourism, the concept of alternative tourism has emerged. The concepts of eco-tourism, community based tourism, pro-poor tourism, mountain tourism, agro-tourism, etc. Have emerged to make the tourism industry more sustainable. All of these types of tourism have both strengths and limitations. To combat other types of terms, a confluence of ‘alternative’ terms has been coined. “New moral tourism” is described as, among other things, ethical tourism [17]. To represent the issue of ethics, Lea (1993) [18] coined the phrase “responsible tourism.” responsibility required solid understanding of the process of how a responsible destination actually perceived a sustainability agenda-“Awareness, Agenda and Action” [19]. Goodwin and Francis (2003) combine the terms “responsible” and “ethical”. The two terms may well be identical, but the term “responsible” is more inclusive than ethical. Responsible tourism has a direct connotation with sustainable tourism and has three comprehensive areas of apprehension: the impact of tourism on the environment, the just distribution of economic benefits to all sections of the population, and minimising negative socio-cultural impacts. As cited in Bob (2016:3) [16], Husbands and Harrison (1996) gave one of the prior definitions, stating that responsible tourism is “a way of doing tourism planning, policy, and development to ensure that benefits are optimally distributed among impacted populations, governments, tourists, and investors."

Concerning the social features of responsible tourism, local involvement in tourism planning, development, and decision-making processes is very important to develop confidence in the tourism industry. Moreover, monitoring social impacts during the process of tourism scheme is essential to reduce negative impacts and enhance positive aspects. Tourism has to be easily accessible to all communities; in particular, exposed and underprivileged communities must be participants as responsible tourism objects to create an “inclusive social experience” (Issac, 2014:90) [20]. Furthermore, misuse of anything must be contested, and tourism must be done wisely to preserve and inspire social and cultural diversity. Lastly, it must be warranted that tourism creates positive support for the health and education of local communities, strengthening the fact that responsible tourism makes linkages to other sectors beyond tourism since it has political, environmental, economic, and social dimensions [21,22].

1.2. Local communities’ perception

The social aspects of tourism development are influenced both favorably and unfavorably. Travis (1984) listed a number of social factors, including social change within the local community, cultural diversification, modernization of the local culture, enhancement of public services and social amenities, image development of the host community, and conservation. Social impact is recognized as a helpful tool that nevertheless aids in the growth of local tourism and is a fundamental requirement for the creation of a sustainable tourism industry [21,[23], [24], [25]].

Studying the local residents' attitudes, thoughts, and feelings, is one way for researchers to obtain information about tourism's impacts. As the most instantaneous and directly affected group, residents are more sensitive to tourism's impacts. They could make a comparatively appropriate valuation of the present tourism development. Enduring and prosperous tourism development is dependent on the local communities' perceptions of tourism and tourists, and as a result, it should be developed with the host community's needs and desires in mind. It is because the community's attitude is essential for visitor retention, satisfaction, and recurrence inspections, as well as for the future endeavour of tourism development in general [26].

Several studies are currently being undertaken to evaluate and analyze the importance of tourism development and community participation [[27], [28], [29]]. Nevertheless, there have been inadequate studies on residents' perceptions concerning responsible tourism in unindustrialized regions in general and in Ethiopia in particular. Previous research on local community perceptions of tourism development has primarily focused on first-world countries, with only few studies focusing on developing countries [4,30,31]. Even if tourism has received substantial courtesy from policymakers worldwide, the local people's perception has gone unnoticed. The host community will respond positively to tourism development if tourism produces promising upshots [32]. Nunkoo and Gursoy [33] and Halim et al. [27] indicated that if tourism development advances the living status in the area, the natives will respond positively, and vice versa. In general, this study attempts to shed some light on the view of the host community's perception towards future responsible tourism development in Amhara Regional State, one of the emerging tourism destinations in Ethiopia.

1.2.1. Theories on the impact of tourism

Various scholars have tried to identify theories and models concerning the study of how the impact of tourism influences the perceptions of local communities and vice versa. For this purpose, Butler's [34,35] tourism area life cycle model, Doxey's [36] index of irritation model, Smith's [37] host and guest model, and the social exchange theory have been identified. Each model has its own strengths and shortcomings, even if presenting them is beyond the scope of this article. For the sake of this research, social exchange theory is used as a lens.

Social exchange theory has been considered an appropriate framework for developing an understanding of residents' perceptions of tourism impacts [[38], [39], [40], [41]]. Social exchange theory suggests that individuals will engage in exchanges if (1) the resulting rewards are valued; (2) the exchange is likely to produce valued rewards; and (3) perceived costs do not exceed perceived rewards [42,43]. These principles suggest that residents will be willing to enter into an exchange with tourists if they can reap some benefit without incurring unacceptable costs. Theoretically, residents who view the results of tourism as personally valuable and believe that the costs do not exceed the benefits will favour the exchange and support tourism development [44]. The benefit of using social exchange theory is that it can accommodate explanations for both positive and negative perceptions and examine relationships at the individual or collective level. The assessment of residents' perceptions of tourism's impact, which is the main cause of support for tourism, is dependent on what residents' value [45,46].

1.3. Research methodology

1.3.1. Justification for the site selection

For the quantitative method of data collection, two tourist attraction sites were selected (Bahir Dar and Debark Town). The Bahir Dar tourism corridor, which is bounded by Lake Tana, the largest lake in Ethiopia and the second largest in Africa, was added to the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves in June 2015 and is among the attractions for biodiversity and significant cultural heritage with different monasteries and Tis Abay Fall. Debark was selected due to its position under the famous natural attraction of Semien National Park, which is attributed to its unique flora and fauna.

1.3.2. Research design

In terms of philosophical stance and research schemes, this study used mixed methods. Various researchers acknowledge the investigation of a specific social phenomenon through the use of mixed methods, acknowledging the improvements in knowledge of a topic typically from a qualitative or quantitative perspective [[47], [48], [49]]. It also enabled a shift in thinking so that qualitative and quantitative orientations became complementary rather than competing perspectives.

1.3.3. Sources of data and participants of the study

The study used a community approach that involved residents, tourism entrepreneurs, tourism authorities, owners or managers of accommodation establishments (AEs), travel agencies, car rentals, restaurants, bars, and tourist shops who are assumed to have major influences on the Amhara region's state tourism development. Residents of Sefeneselam from Bahir Dar city and residents of Kebele 03 from Debark town have been in one way or another dependent on tourism for employment and/or income, thus being selected for this study.

1.3.4. Sampling and quantitative data collection

A self-administered questionnaire survey was distributed to the respondents’ on face to face basis with a proposed sample of about household heads of Sefeneselam kebele from Bahir Dar town and household heads of kebele 03 from Debark town. One method of identifying a suitable size of sample for the purpose of surveying is that set out by Ryan (1995) which is based on convinced suppositions. The simple random sampling method looks suitable when the lists of the units studied are accessible [50]. The simple random sampling method looks suitable when the lists of the units studied are accessible. This technique is worth it in the sample survey conducted with households supposed to be homogeneous in information. It is possible to access the lists of the residents from each study kebeles. Thus, in this study, a simple random sampling technique was employed. According to Ryan (1995), in the case of a finite population where the population size is known, the sample size determination formula was performed as in Eq. 1

| Eq. (1) |

Where n is the sample size, N is the population size, s-standard deviation or estimate, B = allowable error, and z = Z score based on desired confidence.

The total population of the study was acquired from the Amhara National Regional State Bureau of Finance and Economic Development (ANRS BOFED). The bureau estimates or calculates the households of the region based on the household forecast rate of the country. Based on this estimation, the household of Sefeneselam is 1726, while Kebele 03 of Debark is 1858. Table 1 presents data sources from the ANRS BOFED estimate, which is based on the household forecast rate of the country. Based on this estimation, the household of Sefeneselam is 1726, while Kebele 03 of Debark is 1858. As referred to by Ryan (1995), the standard deviation is estimated at 1.25 (or the range divided by 4), and taking a confidence level of 95% gives a z-value of 1.96, which is customary. Setting the allowable error for the measurement item at a 4% tolerance level (B = 0.2) gives the above sample outcomes [50].

Table: 1.

Sample size for the household survey per respective sites (Residents sample).

| Study site | Region | Zone | Name of District | Sample Kebele | HHHs at kebele | Sample size | Added sample | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahir Dar | ANRS | Bahir dar | Bahir dar | Sefeneselam | 1726 | 141 | 10 | 151 |

| Debark | ANRS | North Gondar | Dabark | Kebele 03 | 1858 | 139 | 10 | 149 |

| Total sample for residents is equal 300. NB: The researcher took additional 10 samples for each study population to minimize sample error. | 280 | 20 | 300 | |||||

Data Source: The Amhara National Regional State Bureau of Finance and Economic Development (ANRS BOFED) [51].

1.3.5. Procedures and techniques of data collection

1.3.5.1. Qualitative data collection procedure

There is no definite, clear-cut division between the various stages of fieldwork for qualitative methods. The initial stage of fieldwork involves getting to know the informants and becoming acquainted with the varied local lifestyles be in homes, fields, and social gatherings. In order to better understand how individuals live, think, speak, and act, as well as how they characterize and explain their worldviews. On top of that, the researcher approached as active member and used to take part in a variety of socio-cultural activities and events. The researcher had several opportunities to take part in events, including religious and cultural festivals, campaigns to promote travelling, and other social gatherings, while conducting the research fieldwork. Consequently, the researcher had the chance to close the gap between community members and the researchers.

In this study, observations, focus group discussions, casual chats, and one-to-one interviews with a semi-structured questionnaire were considered to collect the data as indicated by Tesfaye (2015), with possible amendments [52].

NB. From the indicated Table 2 informants, the number of female informants’ is only six. Women only participate in tourism authorities and as owners of tourist hotels. The other tourism-related activities (hotel manager, tour guide, tour operator, and car rental) are predominantly occupied by men.

Table 2.

Informants profile and their number for semi-structured interview.

| Category of informants | Tour guides | Tour operators | Tourism authority and expert | Tourism experts and hotel managers | Other stakeholders | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of informants pre category | 6 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 32 |

Open-ended questions were used in the interview guide so that the researcher would have room to make more inquiries in response to the discussion. As a result, the semi-structured interviews' guiding questions were continuously adjusted to reflect any new themes that emerged from earlier interviews or observations. By following the participants' own sense of what is noteworthy and important about them, the researcher was able to clarify their grasp of the ideologies and views conveyed, as the case is supported by literature [53,54].

The majority of the interviews were conducted over prolonged periods of time and in circumstances where taking notes was assumed insufficient. With each informant's previous informed agreement, the researcher recorded using tape. After that, the audio recordings of the interviews were arranged, translated, and transcribed. The researcher then conducted focus groups (each group consisting of 8–12 participants) with senior citizens, tour operators, tour guides, women, tourism experts, tourism authorities, and other stakeholders.

1.3.6. Data analysis techniques

1.3.6.1. Qualitative data analysis techniques

Thematic analysis: is the most common analytic instrument for data gathered through qualitative instruments. According to Creswell [55], it is a technique of applying themes to cluster and organize similar responses or data into a single theme. It provides an effective tool of analysis to manage the bulk of qualitative data within a reasonable theme. Thematic analysis is an effective strategy used to organize, identify, analyze, and report patterns (themes) within the data.

Content analysis is a qualitative analysis technique that helps the researcher analyze text data drawn from verbal, printed, or electronic sources. It is flexible, as it can range from impressionistic interpretations to highly systematic analyses of text-based data [55]. Besides, it incorporates different analytic approaches like impressionistic, intuitive, and interpretive analyses as well as systematic, strict textual analyses.

1.3.6.2. Quantitative data analysis

The initial step in analyzing the data will be putting together descriptive statistics. Thus, the mean (or average value) and standard deviation will be reported. The Chi-square test of association is an essential tool for looking at the prevailing associations among the interactional variables [56,57]. Cross-tabulation results will help to discern the general patterns seen among the associated variables. Hoyles et al. [56] expounded on the measures of association as a form of descriptive statistics instrumental in summarizing the relationship between variables. The results discussed the prevailing relationships among the variables compared through column percentages. The Likert-scale was used in the analysis to assess the community's perception. In the Likert-scale, 4 represent a higher amount, 3 represents a medium amount, 2 represents a small amount, and 1 represents not at all [58].

1.3.6.3. Triangulation Analysis

The analysis applies a mixed-convergent design. Convergent Mixed Methods Design: One-phase design where both quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analyzed and then the analyses of the quantitative and qualitative data were compared to see if the data confirmed or contradicted each other. According to Creswell and Clark (2011: 77) [59], this design was optimal as it allowed the researcher to “triangulate … compare and contrast quantitative statistical results with qualitative findings for justification and validation purposes” [60]. Thus, a convergent design that mixed the data from qualitative and quantitative sources was used for the overall analysis.

1.3.7. Ethical considerations

1.3.7.1. Research ethics

Research ethics need to be observed during the study to protect participants from harm and ensure their confidentiality of information. Research ethical issues to consider include.

-

•

Obtain consent from respondents

-

•

Maintain confidentiality of issues obtained from respondents

-

•

Make sure respondents are not harmed in any way

-

•

Do not manipulate answers

-

•

Respect respondents' right, e.g., when they refuse to answer certain questions

-

•

Adhere to standards set in the research area where the study is taking place

-

•

Avoid using technical jargon when possible;

-

•

keep language simple

-

•

Respect the right of the respondents to withdraw their participation from the study at any time

-

•

Gender awareness: assign as many female enumerators as possible and provision of awareness creation on how to collect data in gender norm conservative community.

1.3.7.2. Consenting

The research adheres to international best practises in research ethics. The study will use verbal consent from the informants and written consent from the Bahir Dar University of Social Sciences Ethical Clearance Evaluation Committee (Ref. No.: PGRCS 698/2022) at the approval date of December 10, 2022. The full names of the ethical committee are Professor Arega Bazizew, Dr. Mulunesh Abebe, and Getahun Kumie. The researchers got informant consent from each participant by addressing their rights as participants in the study, giving them time to ask questions, and then giving verbal consent if they agreed to participate in the household survey, focus group discussion, and key informant interview. To use the tape recorder and photo, the permission of the informants and their consent were obtained.

1.3.7.3. Confidentiality

It is important that the researcher protect the confidentiality of study information. As part of research, the work may involve collecting confidential information. The researchers must not show any materials collected to anyone who is not a member of the study team. The presentation of photos in the study is only done based on the ethical clearance we got from the Bahir Dar University of Social Sciences Ethical Clearance Evaluation Committee and the consent of the informants in the field and from archival sources.

The researchers must always use discretion when expressing personal opinions or debating points during discussions. This is important because an expression of disapproval can cause people to change or conceal their behaviour, which means that the researcher cannot observe the behaviour that he or she has been trained to record.

If the informants ask about the purpose of the study, the researcher should tell them that the assessment is financed by Haramaya University and that the confidentiality of all respondents will be protected. For that reason, no names will appear in any research results except with the full consent of the informants, as the issue cannot be found to be sensitive or harmful.

1.4. Data presentation and analysis

1.4.1. The local communities’ perceptions regarding the social impact of tourism

1.4.1.1. Assessing tourism's social impacts by using the inter-item reliability of the items

The social impact of tourism was assessed using 8 items with four-point scales (4 = a great amount, 3 = a moderate amount, 2 = a little amount, and 1 = no effect at all). Some items of survey questions were negatively worded to see the consistency of responses. The inter-item reliability of the items was very good (α = 0.69), indicating that the items have good inter-item reliability.

The sum of valid responses was obtained and divided by the number of responses to obtain a summary measure of respondents' perceptions of the impact of tourism on the social context of residents. As mean value is susceptible to being affected by extreme values, median value was used to group respondents’ opinions of the impact of tourism on their cultural context. The mean value was considered to see the opinions of the impact of tourism on the cultural context of residents. As indicated in Table 3, 56.1% of the respondents perceived that tourism has a social impact.

Table 3.

Communities’ perceptions concerning general social impact of tourism.

| Frequency | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | has no impact | 130 | 43.9 | 43.9 |

| has impact | 166 | 56.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | ||

1.4.1.2. Local communities’ perception regarding the positive social impact of tourism

As indicated in the above paragraph, the communities’ perception regarding the positive impact of tourism is presented with seven items and at four-point scale which is also supplement with qualitative data.

As indicated in Table 4 above, the communities' perceptions about the effects of tourism on the development and expansion of social services were moderate. The result indicated that 44.9% of the respondents perceived that tourism has a moderate impact on the development and expansion of social services. Whereas 22% of the respondents perceived that tourism has made great a contribution to the development and expansion of social services. On the other hand, 25.3% and 6.8% of the respondents perceived that tourism's contribution to the expansion and development of social services is small and not at all, respectively. As mean value is susceptible to being affected by extreme values, median value was used to group respondents' opinions of the impact of tourism on the development and expansion of social services. As indicated above, the median is 3 (three), which indicates the perception of the communities concerning the contribution of tourism to the enhancement of social services is at a moderate level.

Table 4.

Contributes to the development and expansion of social services.

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | Median | Mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | not at all | 20 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | ||

| A small amount | 75 | 25.3 | 25.3 | 32.1 | 3.00 | 3.00 | |

| A moderate amount | 133 | 44.9 | 44.9 | 77.0 | |||

| A High amount | 67 | 22.6 | 22.6 | 99.7 | |||

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100. | |||

According to the key informant interviews, tourism is a service-demanding industry; it contributes to the expansion of various social services such as hotels, roads, and transportation, internet, water, and electricity services in known tourist destination areas as compared to other locations that do not have such tourist destination opportunities. To fulfill the tourists' demand, stakeholders make every effort at the destination to expand and upgrade the various infrastructures. Tourism contributed to the expansion of Master and Visa cards and banking, road transport, hotel services, electricity, and internet services not only in the cities and towns but also in the rural parts of the country. The tour guide's informant from Gondar ascertained it as such:

The master card and visa card use system and money exchange system are expanded due to the presence of tourism. The expansion of road infrastructure was also initiated by the tourism industry. For instance, Gondar -Debarq road was constructed with good quality due to the presence of tourism. Other social services like electricity, hotel services, and network accessibility are also facilitated by tourism.1

As illustrated, the contribution of tourism to infrastructure development varies from destination to destination, as indicated in the cases mentioned here. It contributed to the development of the asphalt road at the destination of Semein Mountain (Gondar Debark Route). But in the two well-known tourist destinations, which are Lalibela and Tiss Abay (Nile Fall), the road infrastructure is not well addressed. Save the existence of air transportation in Lalibella. The road construction is still at a concert level. The same is true on Lake Tana's Zege Peninsula. On Zege Peninsula, there are around seven churches and monasteries that have been the epicentre of tourist attractions. But still, there is no road construction that connects them. As a result, it becomes a challenge for visitors to move from one site to another. Other infrastructures like water, hotels, and toilets are not well developed to the expected standard. The above analysis is supported by case study presented here:

The distribution of infrastructure in tourism destinations is not fair. For instance, the road to Lalibel and Tiss Abay is still not well done. It is still a concert road. As a result of this, the local communities develop grievances against the government. But still, we do not construct the kind of road that connects them. So it becomes a challenge for the visitor to move from one site to other. Other infrastructures like water, hotels, and toilets are not there.2

According to information gathered from the bureau of tourism and culture, the tour guides and hotel managers, the variation in service expansion at the tourist destinations in the Amhara region is resulting from a lack of well-coordinated and planned tourism development strategies. Even if the tourism policy at the national level is good and the regional governments have also adopted it, there is a huge implementation gap. This argument is supported by previous research findings, as indicated below.

The contemporaneous production and consumption of tourism is essential to its success, [61]. In actuality, the actions of the sector have no quantifiable results if tourists do not travel to a destination. Tourism is seen as a personalized service that only visitors to a destination can take advantage of. As a result, during production, an unfamiliar population will come into contact with the host population. This contact may be advantageous to the host group or detrimental, depending on the degree of cultural disparity and the nature of the engagement. Both the hosts and the guests are impacted by the socio-cultural influence, which typically has a mix of positive and negative outcomes.

Edgell [62] state that a well-researched, well-planned, and well-managed tourism program is one that takes into account the local opportunity to enhance the local economy and the quality of life of the local people. The manner in which tourism contributes to changes in value systems, individual behaviour, family structure, relationships, collective lifestyles, safety levels, moral conduct, creative expression, traditional rites, and community organizations is referred to as the social influence of tourism. This means that the social impact of tourism can be defined as changes in the host population's life as a result of tourism activities and interactions with tourists [63].

1.4.1.3. Contributions for the development of hotels and other social services at destination

As presented in the above Table 5, local communities’ perceptions regarding the contribution of tourism to the development of hotels and other social services were generally expressed in positive terms. 40.2% of respondents believe that tourism has significantly aided the development of hotels and other social services in destinations. 39.9% of the respondents perceive a moderate amount of the contribution of tourism to hotels and other social service enhancements. While 15.2% and 4.7% of respondents believe tourism contributes little or nothing to hotel and other social service development, respectively.

Table 5.

Local communities' perceptions about tourism's contribution to the development of hotels and other social services at a destination.

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | Median | Mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | not at all | 14 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | ||

| A small amount | 45 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 19.9 | 3.00 | 4.00 | |

| A moderate amount | 118 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 59.8 | |||

| A High amount | 119 | 40.2 | 40.2 | 100.0 | |||

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

As key informants and FGDs asserted in this regard, tourism is a very important sector for the introduction of modern types of hotels as well as the preservation of traditional hotels. The most well-known hotels that have been built with a combination of traditional and modern housing technology are called Tukul houses. They are very attractive hotels in terms of design and natural attraction. They have been preserved and updated due to the presence of tourism. For instance, the Tesfa Tukul houses were constructed for the realization of community-based tourism in Ethiopia. They are constructed based on a plan to fulfill the interests of the tourists and the local traditions of the community. It is constructed through the integration of traditional and modern technology by private stakeholders. This finding is also supported by the following case:

Currently, the construction of Tukul houses has become the norm to attract tourists. For instance, Tesfa Tukul is a modern type of hotel that was constructed to implement community-based tourism in Ethiopia. They are constructed based on budget acquired from tourists. Thus, it has both the preservation value of the local housing construction in modern ways and economic values as well.3

As affirmed by key informant interviewees and FGDs, tourism can contribute to the expansion of tourist-standard hotels at different tourist destination sites like Bahir Dar, Lalibella, Gondar, and Deberk, to mention the main tourism destinations in Amhara Regional State. Bahir Dar is the capital city of the Amhara region, and since it is located near and surrounded by Lake Tana Peninsula's tourist attraction sites, the establishment of different types of accommodation services has become imminent. Different types of hotels, lodges, guest houses, and traditional nightclubs have been found in sufficient numbers and of sufficient quality.

According to Sefrin [12], Bahir Dar has been a popular tourist destination since Due to the presence of infrastructure such as the Bahir Dar airport, transportation and medical facilities, banks, and postal services are all easily accessible. Bahir Dar's peaceful, clean, and safe atmospheres, as well as a wide selection of budget to midrange accommodations, hygienic and various cuisine offerings, and comfortable, clean, and safe ambiance, all encourage travellers to stay in town, putting rural tourism economies at risk. Electrification, quick and safe transportation, telecommunication, and safe access to clean drinking water, food, and toilets cannot be guaranteed in areas far from major cities and well-known tourist spots, according to his study. Thus, the existence of the aforementioned social services varies by their location within metropolitan areas.

As affirmed by the key informants, the establishment of Debark town is generally related to the presence of the tourist attraction site at Semien National Park. The presence of hotel services, banking, electricity, and other social services has been attributed to the presence of the tourism industry. Tourist expenditures on lodging, transportation, food, guides, and souvenirs at Semien National Park as a result of infrastructure investments are an important source of income for local communities, providing supplemental income to rural farmers, women, and young people and resulting in increased economic efficiency [64,65].

The scope and calibre of the infrastructure offered in a particular area are crucial factors in tourism. The development of the tourism industry depends heavily on the sector's infrastructure. The governments of some nations have collaborated with the industry by creating infrastructure specifically for the tourism sector in recognition of the significance of infrastructure in the sector [66,67].

The development of a successful tourism location is dependent on infrastructure. The tourism business encourages investments in new infrastructure, the majority of which benefits both local residents and visitors. Airports, asphalt road construction, hospitals, banks, internet services, hotels, and lodges are all examples of tourism development initiatives. The planning and construction of modern infrastructure facilities have been exceedingly difficult. There are seven steps that can be taken to guarantee adequate tourist and related infrastructure, such as ensuring accessibility to and within the destination; improving communal infrastructure; developing new housing capacities; enhancing the quality of services offered; developing necessary infrastructure; upgrading existing housing capacities; and concentrating on destination safety and cleanliness [68].

1.4.1.4. Contributes for the development of transportation system

As indicated in Table 6 above, the contribution of tourism to the development of the transportation system at the destination is attributed to a moderate amount, as indicated in the above table, which accounts for 46% of the respondents' perception rate. 24.3% of the respondents' perceptions were that tourism contributes to the development of transport systems at a high rate. 21.6% and 7.8% of the respondents perceive the contribution of tourism to the development of transportation as a small amount and not at all, respectively. Thus, the perception of the local communities about tourism's contribution to the development of transport services is expressed in moderate terms, which will have positive prospects in the future.

Table 6.

Local communities’ perceptions regarding the contribution of tourism to the development of transportation at their destination.

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | Median | Mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | not at all | 23 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| A small amount | 64 | 21.6 | 21.6 | 29.4 | |||

| A moderate amount | 137 | 46.3 | 46.3 | 75.7 | |||

| A High amount | 72 | 24.3 | 24.3 | 100.0 | |||

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

As ascertained by KII interviews, personal observations, and FGD, the tourism industry has contributed to the expansion of the transportation system. They attested that the presence of airline transportation to Bahir Dar, Gondar, and Lilebella is mainly due to the presence of tourists. Because of the presence of tourism, a suspension bridge was built across the Abay River, which has since become a tourist attraction. Asphalt roads have been constructed in the presence of the Dallol depression in Afar and the presence of diverse and live cultural groups in the southern Ethiopian region, which initiated the construction and expansion of asphalt roads in the region. Due to the presence of tourism, air ports at Axum, Lalibella, and Jinka have been constructed. Thus, the indicated evidence clearly shows that there is a positive correlation between the presence of various tourist attractions and the construction of standardized roads, with some exceptions. The above explanation about tourism's contribution to transport expansion is ascertained by the key informant interviewee as follows:

The Gondar-Debarq road is constructed with good quality. Abay Suspension Bridge at Abay River is constructed due to the presence of tourism. Other roads in southern Ethiopia have been constructed due to the presence of tourism. Health facilities at different destinations are presented to provide health services for tourists, which has benefited the locals as well. So it also serves the local community. In Afar, the Dallor area gets services like asphalt and electricity due to the presence of tourism. For instance, airports at Axum, Lalibella, and Jinka had been constructed due to the presence of tourism.4

According to Sahlemariam [69] Ethiopia's poor land transport conditions and the comparatively long distance between the country and the world's tourist-generating countries make the use of air transportation extremely necessary. As a result, the transportation industry plays an important role in the country's expansion of domestic and international tourism. The Ethiopian Tourism Organization stated that the air service infrastructure is the most important mode of transport used by tourists within and to Ethiopia. Ethiopia Airlines is one of the most prominent companies that contribute significantly to the development of Ethiopia's tourism industry. Ethiopian Airlines appears to be second only to the Ethiopian Tourism Organization (ETO) in terms of importance for tourism growth in Ethiopia.

As the qualitative data source indicates, the presence of air transport services in Lalibella town is mainly attributed to the presence of tourism, as tourism is the main source of livelihood the local community. The expansion of boat transport on Lake Tana is attributed to the presence of tourism. In the previous years, the local people, in general, and the explorers, in particular, had used Tanqwa5 as the only means of transport to visit the different monasteries on the lake. However, international and local tourists, as well as the residents of Bahir Dar and Zege Peninsula, are now using Jelba6 and boats as modes of transportation on Lake Tana. The introduction of these modern transportation systems is due to the tourism industry.

However, the impact of tourism on the expansion of the infrastructure is not up to the expected standards. The tourism industry can generate a huge amount of money for churches and monasteries, the government, and other stakeholders. However, investment in social services and related infrastructure is not commensurate with their economic and social significance. For instance, the roads to Tiss Abay (Nile Falls) and the Rock Hewn Church of Lalibela are not conducive. Still, it is not covered by an asphalt road. Not only the road, but also other social services are not fulfilled, particularly at Tiss Abay. More effort is needed to facilitate tourism investment and finalize the various tourism facilities. Social services in other tourist destinations are not up to the expected standard. The road to Lalibela is the one manifestation that has not been fulfilled to the expected level when we assess its significance as the epicentre for national and international tourist destinations. Lalibella, as a tourist destination, provides air transportation for wealthy national and international visitors. Even if it is too late at this time, the road is under construction to meet asphalt standards.

Secondary sources support the above finding as presented here. All-weather and asphalt roads spreading from Addis Ababa connect all of the country's key tourist attraction locations, such as the historic route, in the eastern, southern, and sestern sections of the country. However, transportation remains a major issue in remote sections of the country's southern and western regions, as well as at several historical sites in the north. Tourists can travel to attractions where there is a decent road network in luxury automobiles provided by national tour operators (NTOs), as well as cars provided by select private tour operators and car rentals. There are also good bus routes to practically all of the country's administrative areas, which travellers can use on their journey [[70], [71], [72]].

In the Lake Tana area, international travellers encountered a variety of difficulties in gaining access to tourist attractions in various portions of the lake. Aside from poor transit, the Lake Tana transportation facilities and boats were all owned by the government and private PLCs, so tourists had no choice except to hire private boats. The expense of renting a transportation boat with all of its attendants was prohibitively exorbitant. Most of the time, getting organized and hiring a service in a group was impossible, and large groups of tourists with the same interest in visiting one destination at a time were uncommon [73]. However, at the moment, this assertion cannot be observed. As I cross-checked it with the Lake Tana Boat Association, boat owners, the Bureau of Tourism and Culture, and as I experienced it as a customer, getting the service of the boats as an individual or in a group trip is possible. At the same time, the cost they incur is not so costly for the local visitors, let alone for international tourists, who have great potential to pay.

1.4.1.5. 1.4. tourism improves the living condition of the community

Local communities' perception of the role of tourism in improving their living conditions was measured by using the Likert scale as a high amount, a moderate amount, a small amount, and not at all rating scales. Their responses are rated as 18.3%, 40.3%, 35.6%, and 5.7%, respectively. As indicated in the scale, the local communities' perception is mainly attributed to a moderate amount and a small amount. This indicates that the impact of tourism is not well pronounced on the local population, which is at a development stage according to Butler's [35,74] stages of tourism development. That means its negative impact is not well pronounced at the local community level, and rather the positive impacts of tourism prevail, as indicated in Table 7 above.

Table 7.

Communities' perceptions of tourism's impact on improving societal living conditions in tourism destinations.

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | Median | Mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | not at all | 17 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.8 | ||

| A small amount | 105 | 35.5 | 35.6 | 41.4 | 3.00 | 3.00 | |

| A moderate amount | 119 | 40.2 | 40.3 | 81.7 | |||

| A High amount | 54 | 18.2 | 18.3 | 100.0 | |||

| Total | 295 | 99.7 | 100.0 | ||||

| Missing | System | 1 | .3 | ||||

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | |||||

The evidence obtained from the KIIS and FGDs supported the above assertion. Tourism creates job opportunities for various levels of society. Most of the beneficiaries' tourism are tour operators, hotel owners, tour guides, and the government in general. They have been getting the lion's share of tourism revenues. The lives of local populations in Debark and Lalibella have been improved due to the presence of tourism. The construction of standardized hotels, restaurants, markets, and supermarkets in Lalibella is attributed to the presence of tourism. In general, the lives of the community of Lalibella are mainly dependent on tourism. If tourism had not been there, Lalibela town could not have been found at its present stage. In the same vein, the establishment and consolidation of Debark Town have been associated with tourism. It creates job opportunities for the community of Debark in different ways. Tourism creates direct and indirect job opportunities. Directly, the community has been engaged as a guide, a scout, or a guard. The main tasks of the scouts are to safeguard the tourists and the parks as well. To get this service, tourists have to pay the appropriate amount of money for it. This is one way of getting money for the community while creating indirect jobs. This assertion is supported by key the informant interviewee from the Bureau of Culture and Tourism of Amhara Region State as such:

Travel operators, national agents, local agents, hotels, and car and horse or mule service providers are the beneficiaries, even if the income they get varies accordingly. The government acquires money from the entrance fee and tax. So in one way or another, the community is a beneficiary since we are part of it. The presence of the hotel creates job opportunities, but the income the employees get is insignificant compared with that of the hotel's owners.7

There is a tour guide association in Debark. The association is responsible for any tourism activities. The members of the association range between 70 and 80. The tour of trekking at Semien Mountain can take 2–10 days, depending on the interest of the tourists. So the involvement of tour guides, scouts, and food service providers is determined by the number of tourists and the duration of their visits. In order to stay for a long time, the tourists have to have sleeping bags, utensils for food preparation, food items, water, bags, and other essentials. Since carrying all these items by human labour becomes difficult, the tourists have to use a mule or horse. The local community has mules and horses for this purpose. So they rent it to tourists. As the guides and keepers of their mules, the owners have been employed. The local youth also provide different services to the tourists at the destination, like food items, clothes, the renting of sleeping bags, the sending of utensils, etc. So they are getting benefits in this way. The above-mentioned issues are the direct benefits of tourism to the local community.

More importantly, hotel tourism is very important for the community. So many standardized hotels are constructed due to the presence of the tourism industry. But tourism has other diverse advantages for Debark Town. Semein mountain tourism activities are a springboard for Debark town. Tourists spend their time in the town according to their interests. So that they can use hotel services, spend their time in traditional nightclubs, and can buy traditional or indigenous clothes, in general, they can use any social service. Tourism creates a diverse set of benefits for the town. It benefits society, starting from the lower levels of social service, which is an indirect benefit (like shoe shining), to the higher levels of social service (hotel owners and transport providers), which is attributed as the indirect benefit of tourism. Remote tourist attractions in the Amhara Region are not up to snuff in terms of technology, except for sites like Debark and the town of Lalibela. As a result, it makes it difficult for tourists to stay longer in rural regions, and it prevents the development of high-quality tourism products that generate more cash for local people. On the one hand, the research sites benefit from their proximity to Bahir Dar.

Airports, public transportation, medical facilities, banking, and postal services are all available in the towns of Bahir Dar, Gondar, and Lalibella. By enabling quick access in an emergency, these services can tempt tourists to stay in rural locations. Bahir Dar's quiet, safe, and clean environment, vast choice of affordable to moderately priced lodging options, hygienic and varied cuisine options, and comfortable, safe, and clean ambiance all attract visitors to stay in town, threatening rural and remote tourism enterprises. Electricity, quick and secure transportation, communication, and unhindered access to sanitary facilities, food, and clean water cannot be guaranteed in any given place [75]. Planners of tourism must take into account these structural factors since structural development is expensive, and it is unclear whether it will be a government priority in distant locations in the next few years.

The tourists were blown away by the incredible hospitality shown by the locals. This could be advantageous for new tourism activities such as collaborative food production or farming. However, the line between international sharing and learning and pure commercialization is always blurry. As a result, social sustainability will only be accomplished if residents accept the sharing and learning component of visitors rather than seeing them as ‘cash cows.’ Visitors must also have a sense of awareness and a desire to participate in local activities and communicate with the locals. Through the physical separation of both groups through resorts or other types of tourist enclaves, this could be a strategy to dissolve the essentially artificial and fabricated social division between the servers and the served, contributing to the equal standing of facing cultures [76].

According to Brunt [77] and Rasoolimanesh et al. [4], the social repercussions of tourism refer to the impact tourists have on the quality of life in host communities. Sherwood (2007), who established a quality-of -life-based assessment of the social impacts of tourism, agrees [78]. The term “quality of life” refers to a person's overall well-being. Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers (1976) [79] define quality of life as the degree of happiness, satisfaction, and standard of living. Tourism contributes to the economic well-being of local communities by creating jobs. Tourism benefits host communities by creating jobs and generating revenue, thereby improving the quality of life of local residents. Tourists' economic benefits provide the financial means to access modern facilities in the form of goods and services, thereby improving the quality of life of local residents [80,81]. In addition, tourism offers several opportunities to upgrade infrastructure, such as outdoor recreation facilities, parks, and motorways. Tourism has resulted in a rise in the availability of recreation and entertainment facilities in Australia [80].

1.4.2. Local communities’ perception about the negative social impact of tourism

The negative impact of tourism is assessed by using five interrelated items on a four-point Likert scale. The quantitative data is also supplemented by qualitative data and secondary sources to increase the reliability of the findings.

1.4.2.1. Contribute for the dissemination of prostitution in the community

As indicated in the above Table 8, the respondents' perceptions regarding the negative impact of tourism on disseminating prostitution in society did not, as such, indicate much difference. Their perception of the negative impacts of tourism accounts for 19.9% as not at all, 27% as a small amount, 31.4% as a moderate amount and 21.3% as a great amount. Thus, the communities have developed a slight negative perception of the impact of tourism on their perception rate. The median is set at number 2 (a small amount), which indicates the level of perception is in its developing stage or at a small amount.

Table 8.

Local communities' perceptions regarding tourism's contribution to the dissemination of prostitution at the destination.

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | Median | Mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | not at all | 59 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| A small amount | 93 | 31.4 | 31.4 | 51.4 | |||

| A moderate amount | 81 | 27.4 | 27.4 | 78.7 | |||

| A High amount | 63 | 21.3 | 21.3 | 100.0 | |||

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

According to the information acquired from FGD and KII, at tourist destinations, prostitution has become an observable phenomenon. As tourism's impact is diverse and it invites different stakeholders (tourists), prostitution becomes the daily activity of some tourists at the destination. Some tourists come to Ethiopia for sexual lust, and they have been engaging in such activities purposefully. While others come for other purposes, they sometimes engage in such acts when they get the opportunity. As key informants attested in Lalibella town, sex tourism is becoming the norm rather than the exception. To get money from the tourists, female children engage in prostitution at an early age. Even if the trend is not well pronounced in other destinations, sex tourism is an ascending tendency in the Ahmara region. Brokers such as informal8 tour guides, hotel owners, hotel managers, and car drivers are the main facilitators of the practice. These stakeholders have been facilitating prostitution at the destinations in lieu of money. The above information was ascertained by one key informant from the Bureau of Culture and Tourism as follows:

There is child abuse in most tourist destinations, even if the extent varies. For instance, foreigners give money to youngsters and they have sex with them. In this case, the brokers are tour guides. Even if they know it is unethical, they have done it for money. I observed it in Lilibela as an eyewitness. The foreign tourists deceive the young girls as they come here take care of them. They promised to be a father and mother. After they approached them in this manner, they abused them for sex and left them without taking care of them as promised. If this practice is continued and expanded to other destinations in such a visible manner, the consequences will be extremely dangerous because it will destroy our norms and values.9

Engaging in prostitution contradicts the existing cultural and religious values of society. Lalibela, for instance, is a sacred place. But as a result of tourism, every social evil, like prostitution, becomes the norm rather than the exception. Those women who have been engaging in prostitution activities come from other parts of the Amhara region or from other parts of the country. Females from different parts of the country in general and from the Amhara and Tigray regions in particular (due to proximity) migrated to Lalibella to engage in prostitution. They come to Lalibella and engage in prostitution because the money they can get from tourists, particularly foreign tourists, is relatively high. The locals do not get involved in prostitution since they are identified by their customers or the community, as it is not a socially acceptable deed. Even if the expansion of sex tourism in the study area is not recognized by the local people as an intentional aspect of tourism, the prevalence of its practice is undeniable, and the trend of how it expanded and implicitly existed as a social force in the sector is ascertained by previous research outputs as indicated underneath.

The term sex tourism refers to travel with the primary intention of engaging in commercial sexual interactions. Prostitution was considered a means of travel in ancient society even if the degree varied, according to Wall and Mathieson (2006) [82]. They contend that it is very challenging to pinpoint the exact degree to which tourism is to blame for an increase in prostitution in popular tourist destinations. However, there are a variety of hypotheses that might aid in understanding and explaining the rise in prostitution in tourist areas. By its very nature, tourism ensures that people are free of the puritanical limitations of daily life, that anonymity is maintained when they are away from home, and that money is available to spend. Tourism has produced settings and situations that attract prostitutes and their clients. In this case, tourism has the potential to foster an environment where prostitution is practiced and thrives.

These circumstances support the continuation and spread of prostitution; nevertheless, because tourism provides jobs for women, it may help them improve their economic situation. This may lead to their liberalization and, finally, their involvement in prostitution in order to sustain or even gain new economic levels. The overt component of the attractiveness of some destinations is the liberalization and promotion of prostitution by the destination, and therefore the development of sex tourism. Tourists are a convenient clientele for poor people with few economic alternatives who are forced into prostitution to survive.

1.4.2.2. Destroys the tradition and history of the society

As indicated in the above Table 9, the question regarding the impacts of tourism on destroying the local communities’ tradition and history is rated as not at all, and a small amount constitutes 33.4% and 34.9%, respectively, whereas the responses for a moderate amount and a high amount, which count as 22% and 9.5% respectively. As indicated in the above presentation, the negative impact of tourism at the destination is not highly pronounced, as expressed by the respondents.

Table 9.

Communities’ perceptions regarding tourism can destroy the tradition and history of the host society.

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | Median | Mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | not at all | 99 | 33.4 | 33.6 | 33.6 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| A small amount | 103 | 34.8 | 34.9 | 68.5 | |||

| A moderate amount | 65 | 22.0 | 22.0 | 90.5 | |||

| A High amount | 28 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 100.0 | |||

| Total | 295 | 99.7 | 100.0 | ||||

| Missing | System | 1 | .3 | ||||

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | |||||

As indicated by the key informant interviewees FGDs, the one negative impact of tourism on the social value of the community is that the local people imitate and want to adapt to the tourists' way of life (dressing, hair style, smoking is taken as a means of modernizing, speaking the language). For foreigners, everything is open regardless of their religious or other criteria (qinona10 or dogma,11 the church or the monastery). For instance, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo church has religious rules and regulations about how followers and other members of society should visit the church for various purposes. They have rules and regulations for anyone who wants to visit a church or a monastery. Non-believers, for example, are not permitted to enter the church. Even non-believers among the local people respect the norms and values of the church, and they do not want to visit the church and the monastery out of due respect for the religious values and norms. A foreigner can visit everything except Bête Mekides. Even the tour guides and administrators of the church allow them to visit since they have the money. This shows how tourism develops the wrong perception of foreigners as superior. Many tourists do not have the religious norms and values that are dictated to them while visiting. They are aliens to it, and they do not sense what is wrong or right. They are simply eager to see and visit everything. Thus, the responsibility rests with the local people to manage the impacts of tourism in a proper manner. The above finding is also substantiated by the key informant, the tour guide, in Debark as follows:

Traditional or unlicensed local guides who do not have the necessary credentials about the norms and values of the community do not know the real meaning of religious values or the meaning that is written in different manuscripts. In the same vein, some priests do not respect the rules and dogmas of the church. Both these guides and priests present everything for the tourist as far as they can get money. Even sometimes, heritage items like books, crosses, and gedlats (Hyman) are presented for sale, knowingly or unknowingly. For instance, in Lalibella Rock Hewn Church on Bete Medhanialem, there is a Holly Cross called Afro-Aygeba12 which has about 7 kilos of weight. The Cross is unique in its religious values, and it also has medical values in treating illness as the community believes. It can be accessible to the public only on Sundays and at the date of Medhanialem (on the 27th of each month). But sometimes priests present it outside of this normal time for the tourists to get money. They do not serve it to the local people during the mentioned days since it is forbidden by religious principle. But for the tourists, this rule has been breached since they have the dollar. This shows that if you have the money, you can get or access everything, regardless of its social and religious values.13

On the other hand, the tourists themselves want to impose their ideology, thinking, and ways of life. They see everything as having only material value, and they want to have it or buy it for their own purposes. There is an erosion of religious and social values. For instance, respect for everyone, eating together, cooperating (communal living), and supporting each other in every aspect of life have been the norms, and they want to have them or buy them for their own purposes. Everything is changed for money. Local communities develop the wrong perception that foreigners are the sources of money. When they get tourists, they rush to ask for money rather than considering them guests and treating them as the local culture dictates. For example, if one tourist comes and wants to take a photo with someone, he or she will ask for money, even for research purposes. The other thing is dependency syndrome. The local people see that the tourists have everything and are undermining themselves for economic gain. For them, tourists are considered to have everything.

Local tour guides create a negative impact on tourism, particularly unlicensed ones. They give the tourists false information. At present, it has become a norm, which does not represent our history, cultural traditions, or norms. As evidenced by the bureau of culture and tourism, training for guides about the code of ethics has been given to alleviate the problem. But the training has not been given in a coordinated and well-planned manner. The federal government and the regional government do not work together in designing policies and strategies. There were some efforts made independently between the two government bodies, but they could not bring successful results.

Secondary sources substantiate the above-mentioned harmful societal impact of tourism. Religion has also suffered as a result of tourism. The commercialization of this institution, which has already lost its traditional ambiance, has been aided by frequent photography, the development of signs, and the disruption of ceremonies. According to studies by the English Tourist Board on tourism and English cathedrals, tourists cause significant problems in terms of traffic, wear and tear, litter, and, most crucially, disruption of religious services. The results of exotic religious ceremonies are comparable. In McKeen's study of Bali, it has been questioned whether temple ceremonies, their observances, music, dances, and offerings have become a sort of floorshow for both foreign tourists and the Balinese [83].

According to a variety of findings, tourism also contributes to the development of tourist-induced forms of change in local communities. These are the results of exposing locals to consumer goods like radios, televisions, and movies, which expose people to a wider range of needs and hasten the social transformation process. As the economy expands as a result of tourism enterprises in nearby villages, there will be an increase in income levels and the percentage of people working in the sector that is monetized. This will change the consumption patterns of the local populace. The extent of the social divide between hosts and visitors will also affect how much the tourism industry impacts society, as claimed by Wall and Mathieson [82]. According to Inskeep, research outputs could be influenced by a variety of factors, including religious convictions, customs, lifestyle choices, and dress rules behavioural tendencies, a sense of time management, and attitudes towards strangers [84].

1.4.2.3. Expansion of theft and illegal money transaction

The perception of the local community concerning the negative impact of tourism in relation to theft and illegal money transactions is increasing, but it does not reach the accounts at a higher level as indicated in Table 10 above. 33.7% and 30.8% of the respondents' perceptions are judged as a small amount and a moderate amount, respectively. The scales of the two extremes, that is, not at all and a high amount, are rated at 17.2% and 18.2%, respectively, which indicates neither side. From the data, these kinds of negative impacts of tourism have prevailed as small and moderate rate.

Table 10.

Local communities' perceptions about tourism's contribution to the expansion of theft and illegal money transactions.

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | Median | Mode | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | not at all | 51 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 17.2 | ||

| A small amount | 100 | 33.8 | 33.8 | 51.0 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| A moderate amount | 91 | 30.7 | 30.7 | 81.8 | |||

| A High amount | 54 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 100.0 | |||

| Total | 296 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||||

As the key and FGD informants ascertained, tourism's negative impact through the expansion of crime is not seen in a very pronounced way. Tourists have been seen participating in illicit trading in cultural heritage only rarely. The extent of their participation is not well known to the community since the issue is handled in an underground manner. Illicit trafficking of cultural properties has a long history in Ethiopia. Starting from ancient times, missionaries, merchants, and various types of tourists have been involved in the taking of cultural properties like religious books, crowns of kings, arts of various nature, archaeological objects, Tabots, ancient money (Maria Teresa), etc. to their home countries. The purpose of being involved in illicit trafficking is varied. It has been for money or knowledge transfer as well as for medical purposes. Data gathered from an elder informant from Bahir Dar town supported the above illustration, as follows:

The negative impact of tourism on addiction and gambling is not well pronounced in the community and is still in its infancy. Illicit trafficking of heritage has been a long –standing practice in Ethiopia. Illicit trafficking of the Ark of the Covenant (tabots), religious crosses, and religious books has been identified in the Amara region as a serious and persistent problem.14

The tour operators in Addis Abeba and abroad have been involved in unlawful money transactions. The money from the tourists has been exchanged in person rather than through legal channels because they have direct contact with them and control every aspect of their tour. Ethiopia forfeits the money it makes from tourism in this situation. The transaction was carried out in a very sophisticated way, making it extremely challenging for the government to manage. The ties between travel operators abroad and in Ethiopia are quite intricate and varied. They may therefore manage the dollar exchange in secret with great ease. Convincing changes in sexual ethics result from tourism. Although it has occasionally been claimed that prostitution thrives in vacation destinations, Mathieson and Wall's study of the literature led them to the conclusion that there was no thorough research to support or refute those claims [82].

1.5. Concluding summary

As the finding of the quantitative data indicates, the positive social impact of tourism in Amhara Regional State is moderate. Whereas the negative social impact of tourism is expressed as a small amount. Since the perceptions of the communities are inclined towards a positive outcome, there is a possibility for the local people to give support for tourism development. In the same vein, the finding of qualitative data indicates that local residents have a favourable response to tourism's importance in expanding and enhancing social services at the destination, even if its contribution varies from destination to destination. As a positive impact, tourism contributed to the expansion and enhancement of hotel, road, air, telecommunication, and internet services at different tourist destinations, with varying degrees and types of services. Thus, to make tourism more sustainable, expansion of these social services at the destination in well-managed and participatory types of social service delivery systems is essential.

At all societal levels, tourism can generate employment opportunities. The majority of tourism's beneficiaries are the government, hotel owners, tour guides, and tour operators. They have been receiving the majority of the tourism-related income. The presence of tourism has enhanced the quality of life for local residents in Debark and Lalibella. The existence of tourism is responsible for the standardization of hotels, restaurants, stores, and supermarkets in Lalibella and Debark Town. Without tourism, these two towns would not have existed in their current form.

While tourism has positive social impacts on destinations, it also has some negative consequences. Most social services, particularly hotels and related social services, do not consider the economic status of the local communities. The investors’ main customers are foreign tourists. The local people do not get the services of most international-standard hotels since they cannot afford them. Even if such a trend is present practically, the response of the local people is not negative. That means the impact is not well pronounced by the local people.

The practice of prostitution is evident in some destinations in the Amhara region. Its practice has been mainly pronounced in Lalibella town. Even if it is not well-pronounced by the host communities, the practice exists covertly at other tourist sites. Some tourists have been participating in illicit trading in cultural heritage. The extent of their participation is not well known to the community since the issue is handled in an underground manner. Illicit trafficking of cultural properties has a long history in Ethiopia. Thus, as tourism has a social impact, minimising the negative social impact and enhancing the positive social impact is an essential responsibility of all stakeholders, which can help communities reap the benefits of the tourism industry in sustainable ways. This argument is supported by secondary literature as such: social sustainability tourism is based on the idea that tourism should contribute to creation of better life for people and better destinations for tourists to visit, needs that the involvement of all stakeholders in responsible ways and contribute to make tourism more sustainable.

Author contribution statement

Gubaye Assaye Alamineh: Conceived and designed the analysis; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Jeylan Wolyie Hussein: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper. Yalew Endawek Mulu: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Bamlaku Tadesse: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed analysis tools or data.

This work was supported by Haramaya University as per the agreement made by the Minister of Science and Higher Education Institutions (MOSHE) and the university with reference number June 2011.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Additional information

Supplementary content related to this article has been published online at [URL].

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

Footnotes

Tour guide key informant interview in Gondar February 2022.

Tourism officer and expert key informant interview in Bahir Dar, January 2022.

A tour operator key informant interviewee, Bahir Dar, in January 2022.

Key informant interview in Gondar in March 2022.

Tankwa is an Amharic word for bark, which is made by the local people in and around the islands of Lake Tana. It is made from a grass like plant, dengel, which is grown on the edges of the lake. Its light weight enables users to pack a heavy load. Fishermen and the islanders use it to transport fish, wood, and other food items.

Jelba is the Amharic name for modern day boats, including motor engines and fore-and-aft sails. Jelba is made of metal and uses a simple motor for movement. They are mainly used for transporting people and have a longer life span of service.

Key informant interview in Bahir Dar Feb. 2022.

Informal tour guides are those who do not have a license from the Bureau of Culture and Tourism but they involve in guiding activities of tourism.

Key informant in January 2022 in Bahir Dar Town.

qnona: the rules and regulation of the church which can be changed based on certain circumstance and varies accordingly. It is given the rights and duties for the priest to amend it based on situation and time.