Abstract

Using longitudinal data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (N = 1,088), we examine changes in maternal perception of closeness and conflict in the mother-child relationship from the child’s preschool to adolescent years, with attention to variation by maternal education. Analyses using individual growth models show that mother-child closeness increases, while mother-child conflict decreases from preschool to first grade. From first grade to age 15, mother-child closeness decreases, while mother-child conflict increases, both gradually. The decrease in mother-child conflict from preschool to first grade and the increases in mother-child conflict from first to fifth grade, sixth grade, and age 15 are less steep for mothers with a college degree than for mothers without a college degree. These findings underscore the importance of examining changes in parent-child relationships using longitudinal data across children’s developmental stages and their variations by parental social and economic status.

Keywords: Early adolescence, longitudinal data, maternal education, middle childhood, mother-child relationship quality, transition to elementary school

Statement of relevance

By tracking the same mother-child dyads from early childhood to adolescence, this research provides new information on how mother-child closeness and conflict change during the child’s transition to elementary school and throughout the elementary school years. By showing the variation in the degree of the increase in mother-child conflict during early adolescence by maternal education, the current study reveals social class inequalities in mother-child relationship quality, which has important implications for other personal relationships.

Researchers agree that parent-child relationship quality—closeness and conflict—changes across children’s developmental stages (Bosmans & Kerns, 2015; Collins & Madsen, 2019; Soenens et al., 2019). However, most empirical studies have focused on adolescence, examining parent-child relationship quality from the child’s perspective (e.g., Branje, 2018; Ebbert et al., 2019; Soenens et al., 2019; Steinberg, 2001). Examining changes in parent-child relationship quality across a wider range of the child’s developmental stages from early childhood to adolescence using the parent’s perspective is important because such knowledge will provide useful insights on how the challenges and stressfulness of parenting—which have implications for the quality of parents’ marital or co-parenting relationships, the quality of parenting, and the well-being of children (Berryhill et al., 2016; Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020; Ponnet et al., 2013; Yoon et al., 2015)—vary according to the child’s developmental stage. Existing studies that have investigated differences in parental perception of the parent-child relationship by child age have used cross-sectional data (Luthar & Ciciolla, 2016; Meier et al., 2018; Nomaguchi, 2012; Roeters & Gracia, 2016). These studies were unable to examine how parent-child closeness and conflict change during the child’s transition to elementary school and throughout middle childhood, the two developmental stages in which changes in parent-child relationship quality remain understudied (Bosmans & Kerns, 2015; Collins & Madsen, 2019; Shanahan et al., 2007).

Using longitudinal data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), collected in 10 locations in 9 states across the United States, this study examines changes in maternal perception of mother-child closeness and conflict across seven waves over the 11 years when the study children were 4 to 15 years of age. Guided by the bodies of research suggesting that parenting style influences parent-child relationship quality (Soenens et al., 2019; Steinberg, 2001) and that parental education is a major factor shaping differences in parenting styles (Hoff, 2006; Kalil et al., 2012; Lareau, 2003), we examined whether the degree of changes in maternal perception of mother-child relationship quality from the child’s preschool to adolescent years varies by maternal education.

Maternal Perception of Mother-Child Relationship Quality from the Child’s Preschool to Adolescent Years

Various perspectives posit that the mother-child relationship quality changes across the child’s developmental stages (Bosmans & Kerns, 2015; Collins & Madsen, 2019; Soenens et al., 2019). Researchers generally concur that mothers perceive their relationship with their child as closest and least conflictual when their child is very young, and perceive the mother-child relationship as least close and most conflictual when their child is in middle school (sixth to eighth grades or 11 to 14 years of age) and in their ninth to tenth grades in high school (i.e., 14 to 16 years of age). After the period of intense attachment behaviors to foster bonds of trust with their parents or primary caregivers during infancy, children’s desire for autonomy and their skills to communicate with their parents begin to expand from the toddler stage to preschool years (Ainsworth, 1989). During the transition to adolescence, which includes the years between the end of middle childhood (10–12 years of age) and early adolescence (12–14 years of age), children increase companionship and emotional involvement in their peer relationships, while continuing to rely on their parents as primary attachment figures (Bosmans & Kerns, 2015). During early adolescence, children tend to desire increased autonomy in daily decision-making and expect parents to be more collaborative than directive, while parents tend to continue to be persistent with the rules and values that they have set (Soenens et al., 2019; Steinberg, 2001). The increasing gap between the child’s desire for autonomy and the mother’s willingness to grant it can result in an increase in mother-child conflict (Branje, 2018; Gao & Cummings, 2019; Steinberg, 2001).

Studies using cross-sectional data with various indicators and measures of maternal perception of mother-child relationship quality have found differences in maternal perception by child age that are consistent with the narratives described above. Using a sample of parents with children under 23 years of age from the 1987 National Survey of Families and Households, a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, Nomaguchi (2012) compared maternal perceptions of the overall quality of their relationship with each of their children across the four groups by their oldest child’s age: 0–4, 5–12, 13–17, and 18–22 years. Mothers whose oldest child was aged 0–4 were most satisfied with their relationship with their children, whereas mothers whose oldest child was aged 13–17 were least satisfied. Using a sample of mothers recruited from 2005 to 2010, the majority of whom were college-educated and residing in the Northeast region of the United States, Luthar and Ciciolla (2016) found that mother-child conflict (e.g., the child is rude) was lowest among mothers with infants and highest among mothers with middle-school-age children; mother-child closeness (e.g., the child is respectful) was highest among those with preschoolers and lowest among those with middle-school-age children. Both Meier and colleagues (2018) as well as Roeters and Gracia (2016) used data from the 2010–2013 American Time Use Survey Well-being Module and found that, compared with mothers with children under age 5, mothers with children aged 13–17 were more likely to report that they felt stressed and unhappy when interacting with their children. Together, these studies suggest that mothers with young children report better mother-child relationship quality, whereas mothers with teenage children report a more conflicting one.

It is less clear how the mother-child relationship quality changes during middle childhood (i.e., 5–12 years of age). Although researchers have emphasized stability in mother-child relationship quality during middle childhood, recent views on child development emphasize continuous increases in children’s independence from parents during middle childhood, suggesting that mother-child relationship quality may gradually change during this developmental stage (Shanahan et al., 2007). Children in middle childhood develop better cognitive and mental skills, such as self-regulation and reasoning, spend more time with non-family members, and pay more attention to friendships than in early childhood (Bosmans & Kerns, 2015; Collins & Madsen, 2019). Elementary school-age children increase their abilities to understand social norms and the nature of interpersonal relationships and assert more autonomy in their relationships with their parents, especially during late elementary school years (Bosmans & Kerns, 2015; Collins & Madsen, 2019). Thus, mothers may perceive that mother-child closeness gradually decreases and mother-child conflict gradually increases throughout their children’s elementary school years.

Only a handful of studies have examined changes in maternal perception of mother-child relationship quality during middle childhood using longitudinal data. Using data from the NICHD SECCYD, Marceau et al. (2015) examined changes in maternal perception of mother-child conflict from when their children were in third grade (i.e., 8–9 years of age) to when their children were 15 years of age, and found that mother-child conflict gradually increased throughout that period. Granic et al. (2003) examined a small sample of parents who had sons in the fourth grade (i.e., 9–10 years of age) and who were attending schools in areas with high crime rates in a medium-sized metropolitan region of the Pacific Northwest, and found that mother-son conflict began to increase when the boys were 11–12 years of age and peaked when the boys were 13–14 years of age. Trentacosta et al. (2011) used longitudinal data from a sample of mothers and their sons from low-income families living in an urban city to identify different trajectory patterns of mother-son closeness and conflict, respectively, between ages 5 and 15. Across the three trajectory patterns for mother-son closeness and the four trajectory patterns for mother-son conflict that the study identified, mother-son closeness and conflict were both highest when the sons were 5 years of age and gradually declined until when the sons were 15 years of age. The inconsistent findings across these studies may be due to differences in the sample characteristics described above.

Using data from the NICHD SECCYD, the current analysis extends the study by Marceau et al. (2015) by examining maternal perception of mother-child closeness and conflict across a wider range of children’s ages (from 4 to 15 years of age). To our knowledge, the NICHD SECCYD is the only study that has collected information about mother-child closeness and conflict from preschool to adolescent years using the same set of questions asked to a sample of mothers with diverse background characteristics living in various locations in the United States. On the basis of the foregoing discussions, we expect that mothers perceive a gradual decrease in mother-child closeness and a graduate increase in mother-child conflict from the child’s first grade to adolescent years, with steeper changes between fifth grade (10–11 years of age) and age 15 (Hypothesis 1).

The SECCYD provides a unique opportunity to shed light on changes in mother-child relationship quality during children’s transition to school, a major developmental milestone that has rarely been studied in this research field. NICHD ECCRN (2004) examined mother-child closeness and conflict as predictors of children’s adjustments during the transition to school, but did not examine patterns of change in mother-child closeness and conflict. The transition to elementary school, or from early childhood to middle childhood, is a period when children’s social and interpersonal worlds expand rapidly (Collins & Madsen, 2019; Entwisle et al., 2003). When children start attending elementary school, mothers generally spend less time directly interacting with them than when the children were younger; instead, they spend more time monitoring their children’s academic progress and relationships with peers and teachers (Kalil et al., 2012). Mothers who reduce their paid work activities when their children are younger tend to increase their work hours when the children start attending school (Killewald & Zhuo, 2019). The expansion of children’s social interactions, the decrease in mother-child shared time, and changes in parenting priority result in the children gaining independence from their mothers during this developmental stage, even though they rely heavily on their mothers to manage their daily lives. Guided by the aforementioned idea that mother-child conflict stems from the gap between children’s desire for autonomy and the actual level of autonomy that children are granted (Gao & Cummings, 2019; Steinberg, 2001), we expect that mothers perceive decreased conflict and increased closeness in the mother-child relationship in the period from preschool to first grade (Hypothesis 2).

Variation by maternal education

Researchers have recognized the need to understand variation in developmental changes in mother-child relationship quality by family and social context (Shanahan et al., 2007; Soenens et al., 2019). This study examined variation by maternal level of education because many studies have documented that maternal parenting style differs by level of education, particularly whether they have a bachelor’s degree (hereafter a college degree) or not, and that parenting style is a key factor influencing parent-child relationship quality. Specifically, parents with a college degree are more likely than those with less education to be responsive to their children’s developmental needs in an age-appropriate manner (Kalil et al., 2012; NICHD ECCRN, 2004). Regarding discipline strategies, parents with a college degree are more likely than those without a college degree to use reasoning than directive or punitive methods (Carr & Pike, 2012; Hoff, 2006; Lareau, 2003). In other words, compared with parents with less education, parents with a college degree are more likely to use the authoritative parenting style, which focuses on mutuality, cooperation, and being nurturing, than the authoritarian parenting style, which emphasizes the importance of children’s obedience to parental authority (Kalil & Ryan, 2020). Several explanations are offered for the educational differences in parenting styles. Higher levels of education are related to more economic resources and financial stability, allowing parents to maintain warm and responsive interactions with their children (Cooper & Pugh, 2020). Education is related to better verbal skills in expressing emotional responses, providing reasons for inappropriate behaviors, and allowing children to negotiate (Hoff, 2006; Lareau, 2003). College is an influential socializing agent that shapes individuals’ value orientation in various aspects of life, including parenting (Weininger et al., 2015). Liberal arts education, a core feature of most four-year colleges and universities, emphasizes critical thinking and encourages students to think for themselves (Tsui, 2008).

These differences in parenting styles have implications for parent-child relationship quality. The authoritative parenting style, which is more likely to be used by parents with a college degree than those without one, is negatively related to parent-child conflict during early childhood (NICHD ECCRN, 2004) and adolescence (Sorkhabi & Middaugh, 2014). In contrast, the authoritarian parenting style, which is more likely to be used by mothers without a college degree than those with a college degree, is more positively related to mother-child conflict than the authoritative parenting style among mothers with children during early to middle adolescence (Dixon et al., 2008; Rodriguez, 2010; Sorkhabi & Middaugh, 2014). In the authoritative parenting style, parents encourage their children to develop psychological autonomy and to have their own opinions and beliefs (Soenens et al., 2019). Parents’ provisions of such an emotional context, meaningful reasons, and verbal negotiation opportunities make children more agreeable with their parents’ rules and values (Soenens et al., 2019; Steinberg, 2001). Sorkhabi and Middaugh (2014) argue that adolescents are less likely to disclose their emotional and personal issues—an indicator of mother-child closeness—to their authoritarian mothers than to their authoritative mothers, because they may think that their authoritarian mothers would not understand their point of view.

Together, we expect that, across children’s developmental stages, mothers with a college degree are more likely than mothers without a college degree to have closer and less conflictual relationships with their children (Hypothesis 3). We expect that mothers with a college degree are more likely than mothers without a college degree to experience less steep increases in mother-child conflict and less steep decreases in mother-child closeness from middle childhood to early adolescence (Hypothesis 4), because parental provisions of psychological autonomy appear to be especially important for children during this developmental period when children increase their reasoning capacities and assert more autonomy than before (Soenens et al., 2019).

Methods

Data

Data were drawn from the NICHD SECCYD. The SECCYD is a longitudinal study of 1,364 children and their families, which began in 1991 when families of newborns were recruited from hospitals in 10 cities in 9 states in the United States. The datasets and documentation (including institutional review board approval information) are available from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/series/00233). Although it is a sample of children with diverse backgrounds from various regions in the United States, it is not a nationally representative sample of children and their mothers. Because most vulnerable groups were not included in the study, such as mothers under 18 years of age, those not fluent in English, those with substance abuse problems, and families who lived in dangerous neighborhoods, families in the SECCYD were, on average, more economically and socially advantaged, as reflected in a higher maternal level of education, higher family income level, and fewer Hispanic immigrants than their counterparts in the general population. Still, the SECCYD provides a unique opportunity for the current analysis that no other existing dataset does to examine changes in maternal perception of mother-child relationship quality from preschool to adolescence, tracking the same mother-child dyads.

This study used seven waves, including when the study children were four years of age, kindergarten, first, third, fifth, sixth grades and 15 years of age, in 1995–96, 1996–97, 1998–99, 2000–01, 2002–03, 2003–04, and 2006–07, respectively. In each wave, the SECCYD asked the same set of questions regarding the mothers’ relationship with their children. Of the 1,364 mothers who participated in the baseline study, 1,078 mothers at age 4, 1,046 mothers at kindergarten (K), 1,010 mothers at first grade (G1), 1,009 mothers at third grade (G3), 988 at fifth grade (G5), 988 at sixth grade (G6), and 932 at age 15 were re-interviewed. We selected mother-child dyads in which mothers participated in three or more waves of the 7 waves (N = 1,088), as required for performing individual growth models (Singer & Willett, 2003). Heckman’s (1979) test of attrition bias indicated that maternal background characteristics in the baseline interview did not predict whether the mothers were in the analytical sample. The seven waves (age 4, K, G1, G3, G5, G6, age 15) of the dataset were pooled, resulting in N = 7,616 observations. The means and standard deviations for the inter-survey intervals were M = 1.40 (SD = 0.55) for the six waves from 4 years to G6 and M = 1.67 (SD = 0.82) for the seven waves from the ages of 4 to 15 years. Some variables had missing cases (less than 5% for most variables; the largest was 16%), and to incorporate observations with missing cases, we conducted multiple imputations using PROC MI in SAS for the pooled sample with 25 iterations, following Allison’s (2001) suggestion.

Measures

Two aspects of maternal perception of mother-child relationship quality were measured using items from the Adult-Child Relationship Scale. Mothers’ perception of mother-child closeness was the average of seven items (α = .66, .73, .73, .65, .74, .76, .81 for age 4, K, G1, G3, G5, G6, and age 15, respectively), including: (a) “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with my child”; (b) “If upset, my child will seek comfort from me”; (c) “My child values his/her relationship with me”; (d) “When I praise my child, he/she beams with pride”; (e) “My child spontaneously shares information about himself/herself”; (f) “It is easy to be in tune with what my child is feeling”; and (g) “My child openly shares his/her feelings and experiences with me” (1 = definitely does not apply, 2 = does not really apply, 3 = neutral, 4 = applies somewhat, 5 = definitely applies). Mothers’ perception of mother-child conflict was the average of seven items (α = .78, .82, .84, .84, .83, .85, .87 for 4 years, K, G1, G3, G5, G6, and 15 years, respectively), including: (a) “My child and I always seem to be struggling with each other”; (b) “My child easily becomes angry at me”; (c) “My child remains angry or is resistant after being disciplined”; (d) “Dealing with my child drains my energy”; (e) “When my child is in a bad mood, I know we’re in for a long and difficult day”; (f) “My child’s feelings toward me can be unpredictable or can change suddenly”; and (g) “My child is sneaky or manipulative with me” (1 = definitely does not apply, 2 = does not really apply, 3 = neutral, 4 = applies somewhat, 5 = definitely applies). These scales have been used in previous research on children of various ages, including children between 9 months and 3 years (Malmberg & Flouri, 2011), 4 and 8 years (NICHD ECCRN, 2004), 10 and 11 years (Conger et al., 2002), 8 and 15 years (Marceau et al., 2015), and 5 and 15 years (Trentacosta et al., 2011). Whether these measures assess the same qualities of parent-child relationships across children’s developmental stages is beyond the scope of this analysis (Trentacosta et al., 2011).

Child’s age/grade (hereafter, child age) was measured as seven waves of the SECCYD, including age 4, K, G1, G3, G5, G6, and age 15. Goodness-of-fit statistics indicated that the waves of the survey would work better than the average age of children for each wave (Singer & Willett, 2003). Furthermore, we treated child age (i.e., wave of the survey) as a discrete variable, rather than a continuous variable, because doing so produced better goodness-of-fit statistics for the models. This may be because the inter-survey intervals differed across the seven waves.

Maternal education was the highest level of schooling mothers had at the birth of the study child and was measured as a dichotomous variable where mothers who had a bachelor’s degree (thereafter a college degree) or an advanced degree were coded 1, and mothers who did not have a college degree were coded 0. In the supplemental analysis, we examined the same analysis using the five dummy variables of maternal education, including less than high school, a high school diploma, some education beyond high school, a college degree, or an advanced degree, and found similar patterns of differences in changes in mother-child closeness and conflict between mothers without a college degree and mothers with a college degree. The three groups of mothers without a college degree showed similar patterns of change in mother-child closeness and conflict, with mothers with less than a high school diploma showing a somewhat unique pattern compared to mothers with a high school diploma and with some college education. Mothers with an advanced degree showed similar patterns of change in mother-child closeness and conflict to those found for mothers with a college degree.

Control variables.

Six control variables were time invariant. Maternal age at the time of birth of the study child was measured in years. Maternal race/ethnicity was a dummy variable based on self-reports, including White (reference), Black, Hispanic, and other race/ethnicities. Maternal authoritarian parenting values were measured as the sum of 22 items asked in the baseline interview (α = .90) (e.g., “The most important thing to teach children is absolute obedience to parents”; 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). This is a subset of the Parental Modernity Scale of Childrearing and Education Beliefs (Schaefer & Edgarton, 1985). The scale’s scores range from 22 to 110. Child’s gender was a dichotomous variable (1 = girls, 0 = boys). Child’s temperament was measured at 6 months as the average of 55 items (α = .81) (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always), a subset of the Early Infancy Temperament Questionnaire (Medoff-Cooper et al., 1993). A higher score indicated a more difficult temperament. Child’s birth order was measured as a dichotomous variable by assigning a value of 1 if the study child was the first child. Three additional variables were time-varying and measured for each of the seven waves. Maternal marital status was measured as a categorical variable that included married (reference), cohabiting, and single. Maternal weekly hours of paid work were measured as a continuous variable indicating the number of hours mothers usually worked at the time of the interview, ranging from 0 to 90. Family income was a composed variable created by NICHD ECCRN, indicating the total gross annual earnings of family members in the previous year, and the logarithm of family income was used in the analysis.

Table 1 presents the means or proportions of the variables in the analysis of the pooled sample across the seven waves. The average age of the mothers at the birth of the study child was 28.6 years with a range from 18 to 46 years. The racial/ethnic composition of the mothers was 81% White, 11% Black, 5% Hispanic, and 3% other racial/ethnic background. Approximately 40% (39%) of the mothers had a college degree or higher at the time of birth. Supplemental analysis showed that 8% had less than a high school diploma, 20% had a high school diploma, 33% had some education beyond high school, 23% had a college degree, and 16% had an advanced degree. Across the seven waves, three-fourths (76%) of the mothers were married, 6% were cohabiting, and 18% were single. The average hours worked in the previous week was 26.58 hours across the seveon waves. Supplemental analysis indicated that 23.6% did not work, 48.1% worked full-time, and 28.3% worked part-time. The average family income across the seven waves was $76,410 and its logarithm was 10.8.

Table 1.

Means (SD) or Proportions for Variables (N = 1,088, 7,616 Observations)

| Mother-child closeness [Range: 1–5] | |

| 4 years | 4.66 (0.33) |

| Kindergarten (K) | 4.75 (0.33) |

| First Grade (G1) | 4.76 (0.32) |

| Third Grade (G3) | 4.66 (0.36) |

| Fifth Grade (G5) | 4.58 (0.41) |

| Sixth Grade (G6) | 4.55 (0.44) |

| 15 years | 4.29 (0.55) |

| Mother-child conflict [Range: 1–5] | |

| 4 years | 2.36 (0.74) |

| K | 2.34 (0.84) |

| G1 | 2.17 (0.84) |

| G3 | 2.31 (0.87) |

| G5 | 2.34 (0.86) |

| G6 | 2.40 (0.89) |

| 15 years | 2.52 (0.92) |

| Maternal education at childbirth | |

| College degree or higher | 0.39 |

| Control variables—time invariant | |

| Maternal age at childbirth [18–46] | 28.59 (5.52) |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | |

| White | 0.81 |

| Black | 0.11 |

| Hispanic | 0.05 |

| Other race | 0.03 |

| Girl | 0.50 |

| Child temperament at 6 months [Range: 1–5] | 3.17 (0.41) |

| First child | 0.45 |

| Maternal authoritarian parenting values at childbirth [Range: 22–110] | 59.08 (15.04) |

| Control variables—time varying | |

| Maternal marital status | |

| Married | 0.76 |

| Cohabiting | 0.06 |

| Single | 0.18 |

| Maternal weekly paid work hours [Range: 0–90] | 26.58 (19.14) |

| Family income (logged) | 10.79 (1.44) |

Analytical Plan

We examined individual growth models, also known as mixed-effects models for repeated measures, using PROC MIXED in SAS, which produces restricted maximum likelihood estimations (Johnson, 2002; Singer & Willett, 2003). The “repeated” command is used to specify the within-person error covariance matrix. An unstructured matrix was used because the goodness-of-fit statistics indicated that it fit better than compound symmetry or autoregressive covariance. Two models were examined for mother-child closeness and conflict. Model 1 examined the main effects of child age and maternal education on maternal perception of mother-child closeness and conflict, respectively, to assess Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. Model 2 examined variation by maternal education in the association between child age and maternal perception of mother-child closeness and conflict, respectively, using the interaction between maternal education and child age to test Hypothesis 4. To examine whether differences in mother-child closeness and conflict across the child’s ages were significant, and whether differences across maternal education groups were significant, we employed the same individual growth models alternating the reference groups for child age and the interaction between child age and maternal education. The models using G1 and the interaction between G1 and a college degree as the reference groups are presented in this study.

Results

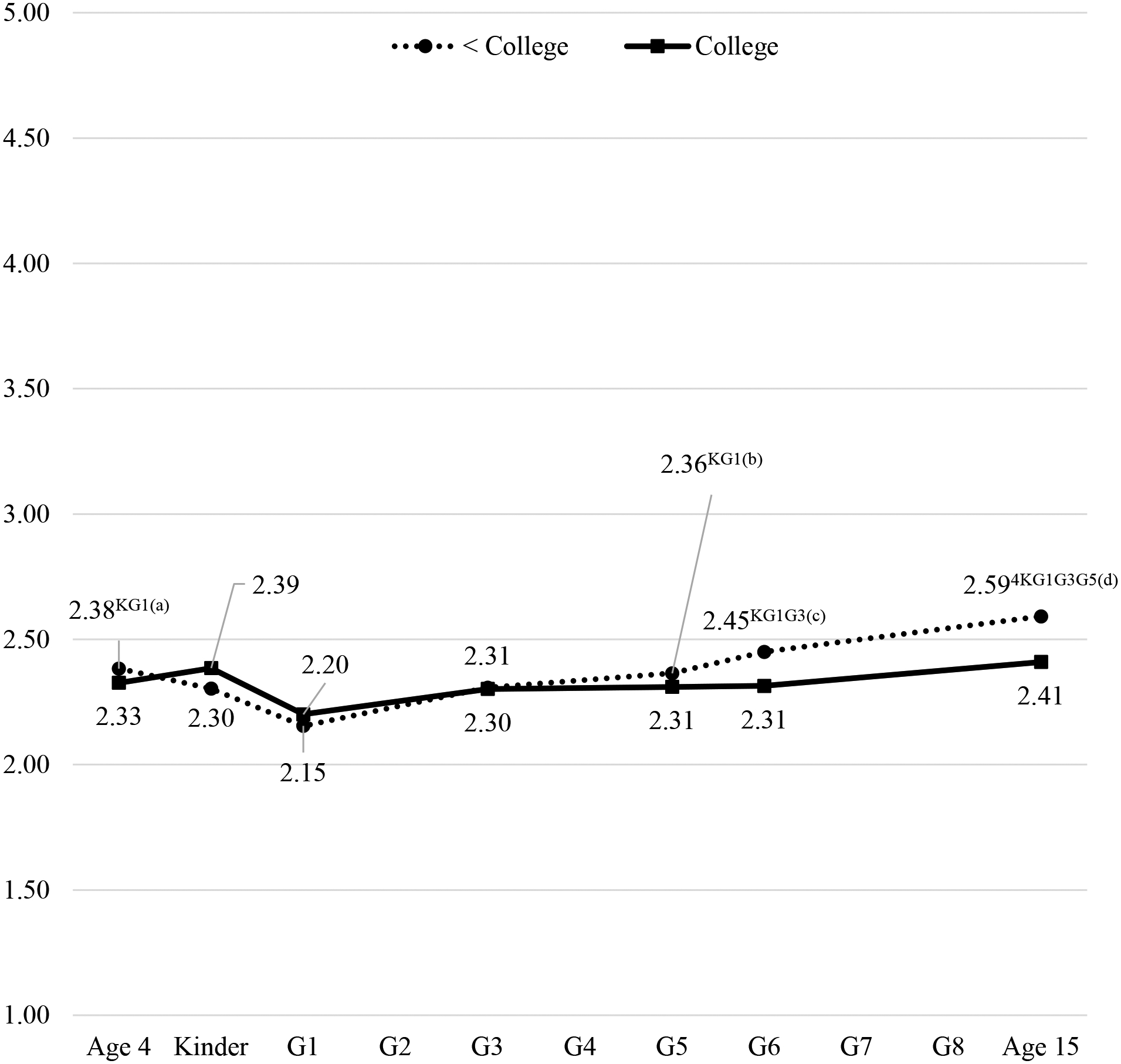

Table 2 presents results from the individual growth models that examined differences in mother-child closeness and conflict from 4 to 15 years of age (Model 1) and their variation by maternal education (Model 2). We first examined the main effects of child age on mother-child closeness and conflict (Model 1). Figure 1 presents the predicted means for mother-child closeness and mother-child conflict scores at each of the seven waves of interviews, calculated using the coefficients from Model 1 and the means for the variables in the analysis shown in Table 1. Maternal perception of mother-child closeness increased from age 4 to kindergarten, remained at about the same level from kindergarten to G1, then declined steadily from G1 to age 15, with a slightly steeper decline from G5 to age 15 than from G1 to G5 (i.e., −0.29 vs. −0.18 or 6.3% vs. 3.8% declines). At age 15, the level of closeness was lower than it was at age 4. In terms of mother-child conflict, the predicted means remained at about the same level between age 4 and kindergarten, declined from kindergarten to G1, when the score was lowest across the seven waves, and then increased gradually from G1 to age 15. Contrary to the prediction, the degrees of increase in mother-child conflict from G1 to G5 and from G5 to age 15 were almost the same (i.e., +0.18 vs +0.17 or 7.8% vs. 7.9% increases). In sum, mothers perceived closest and least conflictual mother-child relationships around G1 and perceived a gradual decline in closeness and a gradual increase in conflict from G1 to 15 years, with slightly steeper changes from G5 to age 15 years for closeness but not for conflict. Hypothesis 1 was supported for mother-child closeness and partially supported for mother-child conflict in that the increase in mother-child conflict occurs at similar rates from G1 to age 15 without a steeper change from G5 to age 15. Hypothesis 2 was supported for both closeness and conflict.

Table 2.

Individual Growth Models for Mother-Child Relationship from 4 to 15 Years (N = 1,088, 7,616 observations)

| Mother-Child Closeness | Mother-Child conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Child age (survey wave) | ||||||||

| 4 years (yrs) | −.096 | .011***BDEF | −.111 | .014*** | .188 | .023***CF | .229 | .029*** |

| K | −.004 | .010ACDEF | −.013 | .012 | .163 | .021***EF | .149 | .027*** |

| G3 | −.101 | .011***BDEF | −.109 | .024*** | .133 | .023***AEF | .153 | .029*** |

| G5 | −.176 | .012**ABCEF | −.185 | .016*** | .171 | .024***EF | .211 | .030**** |

| G6 | −.211 | .013***ABCDF | −.233 | .017*** | .224 | .025***BCDF | .295 | .032*** |

| 15 yrs | −.473 | .017***ABCDE | −.477 | .023*** | .348 | .030***ABCDE | .437 | .038*** |

| Maternal education | ||||||||

| College | −.004 | .019 | −.026 | .023 | −.066 | .049 | .047 | .059 |

| Child age x maternal education | ||||||||

| 4 yrs x college | .040 | .022 | −.103 | .045*e | ||||

| K x college | .024 | .019 | .035 | .042b | ||||

| G3 x college | .019 | .022 | −.052 | .046 | ||||

| G5 x college | .023 | .024 | −.101 | .048*d | ||||

| G6 x college | .056 | .027* | −.182 | .051***fh | ||||

| 15 yrs x college | .011 | .037 | −.228 | .060***afhj | ||||

| Controls | ||||||||

| Age at child’s birth | .002 | .002 | .000 | .002 | .000 | .004 | .000 | .004 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black | −.082 | .027** | −.082 | .027** | −.236 | .069*** | −.236 | .068** |

| Hispanic | .012 | .038 | .013 | .038 | .107 | .095 | .107 | .095 |

| Other race | .009 | .046 | .009 | .046 | −.060 | .116 | −.061 | .116 |

| Girl | .037 | .015* | .037 | .015* | .064 | .039 | .064 | .039 |

| Child temp. 6 mo. | −.047 | .020* | −.047 | .020* | .285 | .050*** | .285 | .050*** |

| First child | −.025 | .016 | −.025 | .016 | .110 | .041** | .110 | .041** |

| Authoritarian style | −.001 | .001* | −.001 | .001* | .003 | .002* | .003 | .002* |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Cohabiting | −.061 | .021** | −.060 | .022** | .075 | .044 | .073 | .044 |

| Single | −.032 | .015* | −.032 | .015* | .096 | .032** | .100 | .032** |

| Weekly work hours | .001 | .000* | .001 | .000* | −.001 | .001* | −.001 | .001* |

| Family income (log) | .005 | .006 | .005 | .005 | .003 | .009 | .004 | .009 |

| Intercept | 4.892 | .115*** | 4.900 | .115*** | 1.028 | .269*** | .978 | .269*** |

| −2 Log Likelihood | 4,416.60*** | 4,440.5*** | 14,652.00*** | 14,648.4*** | ||||

Note. Omitted reference groups are: G1, G1 x college, White, and married. Marital status, work hours, and family incomes are time-varying variables; other variables are time-invariant. Differences from the reference group are significant at

p < .05;

p < .01,

p < .001.

Differences from 4 yrs x college are significant at

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .001.

Differences from K x college are significant at

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .001.

Differences from G3 x college education are significant at

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .001.

Differences from G5 x college are significant at

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .001.

Differences from G6 x college are significant at

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .001.

Differences from 15 yrs x college are significant at

p < .05;

p < .01; and

p < .001.

Differences are significant from

4 years,

K,

G3,

G5,

G6,

15 years.

Figure 1.

Predicted Means for Maternal Perception of Mother-Child Closeness and Mother-Child Conflict from 4 to 15 Years

Note. Differences are significant from 44years, kkindergarten, G1first grade, G3third grade, G5fifth grade, G6sixth grade, and 1515years.

Looking at the association between maternal education and maternal perception of mother-child closeness and conflict in the pooled sample (Model 1, Table 2), we can see that there were no significant differences in mother-child closeness or conflict between mothers with and without a college degree; thus, Hypothesis 3 is not supported. Consistent with prior findings (Dixon et al., 2008; NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Rodriguez, 2010; Sorkhabi & Middaugh, 2014), authoritarian parenting styles are negatively related to mother-child closeness and positively related to mother-child conflict. Our prediction that mother-child relationship quality would differ by level of education was drawn from prior research findings that indicated that parenting styles differ between mothers with and without a college degree. In the supplemental analysis, we examined Model 1, excluding the authoritarian parenting value variable for mother-child closeness and conflict. When the parenting value variable was not controlled for, maternal education was negatively related to mother-child conflict, as expected, although it was not related to mother-child closeness.

Analysis of the variation by maternal education in the change in mother-child closeness from preschool to adolescence (Model 2, Table 2) indicated that the interaction between G6 and college was significant. To better understand this interaction, we plotted the predicted means for mother-child closeness score for each of the seven waves for the two maternal education groups in Figure 2. The degree of decline in mother-child closeness from the G1 to G6 period of the child was slightly less steep for mothers with a college degree than for mothers without a college degree, but the difference was negligible. Overall, the findings did not clearly support Hypothesis 4 for mother-child closeness.

Figure 2.

Predicted Means for Maternal Perception of Mother-Child Closeness from the Ages of 4 to 15 years by Maternal Education.

Note. (a)Mother-child closeness was significantly lower ag G5 than G1 for mothers without a college degree compared with mothers with a college degree.

For mother-child conflict, the interactions between age 4, G5, G6, or age 15 and college were significant. Figure 3 presents the predicted mean score for mother-child conflict in each of the seven waves for the two groups of mothers by level of education. The differences in mother-child conflict between ages 4 and G1 were greater for mothers without a college degree than for mothers with a college degree, largely because mothers without a college degree had a higher level of mother-child conflict than mothers with a college degree when the child was at age 4. Furthermore, mothers without a college degree showed a steeper increase in mother-child conflict from G1 to age 15, including increases from G1 to G5, G3 to G6, and G5 to age 15. In sum, mothers with a college degree perceive less steep increases in mother-child conflict from G1 to age 15 than do mothers without a college degree. Hypothesis 4 was supported for mother-child conflict.

Figure 3.

Predicted Means for Maternal Perception of Mother-Child Conflict from the Ages of 4 to 15 years by Maternal Education

Note. (a)Mother-child conflict was significantly higher at age 4 than K or G1 for mothers without a college degree compared with mothers with a college degree. (b)Mother-child conflict was significantly higher at G5 than K or G1 for mothers without a college degree compared with mothers with a college degree. (c)Mother-child conflict was significantly higher at G6 than K, G1, or G3 for mothers without a college degree compared with mothers with a college degree. (d)Mother-child conflict was significantly higher at 15 years than K, G1, G3, or G5 for mothers without a college degree compared with mothers without a college degree.

Discussion

This study adds an important extension to existing research on variation in maternal perception of the quality of the mother-child relationship by child age, using data from a rare study that tracks the same mother-child dyads and the same constructs of mother-child closeness and conflict across seven waves from when children were four years of age to when children were 15 years of age. We also investigated variations in these changes according to maternal level of education, a key maternal characteristic that influences parenting style.

The current analysis provides a new finding that, within children’s developmental stages from ages 4 to 15, mothers perceive the mother-child relationship as the closest and least conflictual when children are in the first grade (i.e., ages 6–7). This finding is novel in that prior results, using cross-sectional data, generally concluded that mothers perceive their relationships with their children as the closest and least conflictual before children begin attending school (Luthar & Ciciolla, 2016; Meier et al., 2018; Nomaguchi, 2012). The transition to elementary school is a major developmental milestone when a child’s social world expands (Entwisle et al., 2003); however, little research has examined the effects of this major milestone on the mother-child relationship. Several studies have examined the challenges that children of at-risk families may face in the transition to kindergarten (e.g., NICHD ECCRN, 2004); however, research examining the effects of children’s transition to elementary school on parents is scarce. The current analysis highlights the merits of further investigating changes in parent-child relationship quality during the child’s transition to elementary school and the implications of such changes for the well-being of parents and children.

Another key finding is that mothers experience long-term gradual changes in mother-child closeness and conflict over the course of their children’s middle childhood and adolescence. These findings are consistent with the contemporary theoretical understanding of developmental changes during middle childhood, which emphasizes continuous expansions in children’s cognitive abilities and social world, and thus gradual increase in their desire for independence during this developmental stage (Bosmans & Kerns, 2015; Collins & Madsen, 2019). Little research has examined changes in parent-child relationships during elementary school years. As we reviewed earlier, limited research using longitudinal data suggested long-term gradual changes in mother-child relationships. Marceau et al. (2015), who examined maternal perception of mother-child conflict from the year when children were in third grade to the year when children were 15 years of age using the SECCYD, showed a gradual increase in mother-child conflict. Trentacosta et al. (2011), who examined maternal perception of mother-son relationships using a local sample of mother-son dyads from disadvantaged families, showed a gradual decrease in both mother-child closeness and conflict from the year their sons were 5 years of age to the year their sons were 15 years of age. The findings of the current analysis underscore the importance of examining the developmental changes of parent-child relationships longitudinally with a wide age range using a sample of families with diverse background characteristics (Shanahan et al., 2007).

Furthermore, we found that the increase in mother-child conflict from when the child is in fifth grade to when the child is aged 15 is less pronounced for mothers with a college degree than for those without a college degree. Mother-child conflict is a major stressor for mothers and adolescents that affect their mental health poorly (Missotten et al., 2017; Nomaguchi, 2012). The less pronounced increase in mother-child conflict during the child’s transition to adolescence may mean fewer stressors that are beneficial for the well-being of mothers and adolescents. We theorized that educational differences in the mother-child relationship across children’s developmental stages may be due to differences in parenting styles. Some studies suggest that educational differences in parenting values, when measured as responses to hypothetical vignette settings, may not exist in a recent cohort (Ishizuka, 2019). Future research is needed to determine whether the education divide in maternal perception of mother-child conflict during children’s transition to adolescence will be found among mothers in a more recent cohort. In contrast to mother-child conflict, we did not find a clear pattern of educational differences in the decline of mother-child closeness during the transition to adolescence. Overall, the findings mark the importance of understanding developmental changes in mother-child relationship quality in the social (or ecological) contexts surrounding mother-child dyads (Soenens et al., 2019).

This study has some limitations. The SECYYD was not a representative sample of children and their parents in the United States; it included fewer Hispanic immigrants and mothers with lower than high school degrees. Another question for future investigations may be whether changes in the mother-child relationship from children’s preschool to kindergarten and first grade years differ depending on whether children went to preschool full-time. We focused only on mothers due to data limitations on fathers, which asked residential mothers and their spouses/partners about their relationship quality with the study child. For a substantial minority of children, residential fathers changed across the seven waves because of divorce and re-partnering. Because the quality of the parent-child relationship matters for fathers’ well-being as much as it does for mothers’ well-being (Nomaguchi, 2012), we emphasize the importance of examining paternal perception of the quality of the father-child relationship.

Conclusion

Using longitudinal data of mother-child dyads in families with diverse backgrounds, this study observed the novel finding that across the child’s 11 years from preschool to adolescence, mothers perceive that the mother-child relationship is closest and least conflictual around the child’s transition to elementary school, and that mother-child closeness decreases and mother-child conflict gradually increases from middle childhood to adolescence. Mothers with a bachelor’s degree experience a less steep increase in mother-child conflict during their child’s early adolescence than mothers without a college degree, suggesting social class inequalities in mother-child relationships during the children’s developmental stage, when parenting tends to be stressful. Future research on parental experiences of parent-child relationships across children’s developmental stages with attention to variations in social contexts surrounding the parents, children, and their families is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose. This research is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (1R15HD083891-1, PI: Kei Nomaguchi) and is supported by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the NICHD (P2CHD050959).

References

- Ainsworth MDS (1989). Attachment bonds beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44, 709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P (2001). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Berryhill MB, Soloski KL, Durtschi JA, & Adams RR (2016). Family process: Early child emotionality, parenting stress, and couple relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 23(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans G, & Kerns KA (2015). Attachment in middle childhood: Progress and prospects. In Bosmans G & Kerns KA (Eds.), Attachment in middle childhood: Theoretical advances and new directions in an emerging field. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 148, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branje S (2018). Development of parent–adolescent relationships: Conflict interactions as a mechanism of change. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Carr A & Pike A (2012). Maternal scaffolding behavior: Links with parenting style and maternal education. Developmental Psychology, 2, 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & Madsen SD (2019). Parenting during middle childhood. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting, 3rd Edition, Volume 1 (pp. 81–110). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, & Brody GH (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: a replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38(2), 179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, & Pugh AJ (2020). Families across the income spectrum: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 272–299. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SV, Graber JA, & Brooks-Gunn J (2008). The roles of respect for parental authority and parenting practices in parent-child conflict among African American, Latino, and European American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert AM, Infurna FJ, & Luthar SS (2019). Mapping developmental changes in perceived parent–adolescent relationship quality throughout middle school and high school. Development and Psychopathology, 31(4), 1541–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, & Olson LS (2003). The first-grade transition in life course perspective. In Handbook of the life course (pp. 229–250). Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, & Cummings EM (2019). Understanding parent–child relationship as a developmental process: Fluctuations across days and changes over years. Developmental Psychology, 55(5), 1046–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Hollenstein T, Dishion TJ, & Patterson GR (2003). Longitudinal analysis of flexibility and reorganization in early adolescence: A dynamic systems study of family interactions. Developmental Psychology, 39(3), 606–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review, 26(1), 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka P (2019). Social class, gender, and contemporary parenting standards in the United States: Evidence from a national survey experiment. Social Forces, 98(1), 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M (2002). Individual growth analysis using PROC MIXED. SAS User Group International, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, & Ryan R (2020). Parenting practices and socioeconomic gaps in childhood outcomes. The Future of Children, 30(1), 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, Ryan R, & Corey M (2012). Diverging destinies: Maternal education and the developmental gradient in time with children. Demography, 49(4), 1361–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killewald A, & Zhuo X (2019). US mothers’ long-term employment patterns. Demography, 56(1), 285–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, & Ciciolla L (2016). What it feels like to be a mother: Variations by children’s developmental stages. Developmental Psychology, 52(1), 143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg LE, & Flouri E (2011). The comparison and interdependence of maternal and paternal influences on young children’s behavior and resilience. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(3), 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Ram N, & Susman EJ (2015). Development and lability in the parent–child relationship during adolescence: Associations with pubertal timing and tempo. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(3), 474–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medoff-Cooper B, Carey WB, & McDevitt SC (1993). The Early Infancy Temperament Questionnaire. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 14(4), 230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A, Musick K, Fischer J, & Flood S (2018). Mothers’ and fathers’ well‐being in parenting across the arch of child development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(4), 992–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missotten L, Luyckx K, Vanhalst J, Nelemans SA, & Branje S (2017). Adolescents’ and mothers’ conflict management constellations: Links with individual and relational functioning. Personal Relationships, 24(4), 837–857. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network [NICHD ECCRN]. (2004). Fathers’ and mothers’ parenting behavior and beliefs as predictors of children’s social adjustment in the transition to school. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(4), 628–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi KM (2012). Parenthood and psychological well-being: Clarifying the role of child age and parent-child relationship quality. Social Science Research, 41, 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi K, & Milkie MA (2020). Parenthood and well‐being: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 198–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K, Mortelmans D, Wouters E, Van Leeuwen K, Bastaits K, & Pasteels I (2013). Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Personal Relationships, 20(2), 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Roeters A, & Gracia P (2016). Child care time, parents’ well-being, and gender: Evidence from the American time use survey. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(8), 2469–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM (2010). Parent–child aggression: Association with child abuse potential and parenting styles. Violence and Victims, 25(6), 728–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer E, & Edgarton M (1985). Parental and child correlates of parental modernity. In Sigel IE (Ed.), Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children (pp. 287–318). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, McHale SM, Crouter AC, & Osgood DW (2007). Warmth with mothers and fathers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Within-and between-families comparisons. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD & Willett JB (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford university press. [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, & Beyers W (2019). Parenting adolescents. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting, 3rd Edition, Volume 1 (pp. 111–167). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2001). We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Criss MM, Shaw DS, Lacourse E, Hyde LW, & Dishion TJ (2011). Antecedents and outcomes of joint trajectories of mother-son conflict and warmth during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 82, 1676–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui L (2008). Cultivating critical thinking: Insights from an elite liberal arts college. The Journal of General Education, 200–227. [Google Scholar]

- Weininger EB, Lareau A, & Conley D (2015). What money doesn’t buy: Class resources and children’s participation in organized extracurricular activities. Social Forces, 94(2), 479–503. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y, Newkirk K, & Perry‐Jenkins M (2015). Parenting stress, dinnertime rituals, and child well‐being in working‐class families. Family Relations, 64(1), 93–107. [Google Scholar]