Abstract

Parental factors, including parenting behavior, parent mental health, and parent stress, are associated with child stress. More recently, studies have shown that these parental factors may also be associated with children’s hair cortisol concentration (HCC). HCC is a novel biomarker for chronic stress. HCC indexes cumulative cortisol exposure thereby reflecting longer-term stress reactivity. Although HCC is associated with a range of problems in adults such as depression, anxiety, appraisal of stressful events, and diabetes, studies investigating HCC in children have been inconsistent, with particularly little information about parental factors and HCC. As chronic stress may have long-term physiological and emotional effects on children, and parent-based interventions can reduce these effects, it is important to identify parental factors that relate to children’s HCC. The aim of this study was to examine associations between preschool-aged children’s physiological stress measured via HCC and mother- and father-reported parenting behavior, psychopathology, and stress. Participants included N = 140 children ages 3–5-years-old and their mothers (n = 140) and fathers (n = 98). Mothers and fathers completed questionnaire measures on their parenting behavior, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and perceived stress. Children’s HCC was assessed by processing small hair samples. HCC levels were higher in boys compared to girls, and higher in children of color compared to white children. There was a significant association between children’s HCC and fathers’ authoritarian parenting. Children’s HCC was positively associated with physical coercion, a specific facet of fathers’ authoritarian parenting, even after accounting for sex of the child, race/ethnicity of the child, stressful life events, fathers’ depression, fathers’ anxiety, and fathers’ perceived stress. In addition, there was a significant interaction between higher levels of both mothers’ and fathers’ authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC. Children’s HCC was not significantly related to mothers’ and fathers’ anxiety and depression or mothers’ and fathers’ perceived stress. These findings contribute to the large literature that links harsh and physical parenting practices with problematic outcomes in children.

Keywords: Hair cortisol, preschool age, parenting behavior, parental psychopathology, stress

1. Introduction

Parental factors such as parenting behavior, parent mental health, and parent stress are associated with child stress measured via salivary cortisol and questionnaires (Dougherty, Smith, et al., 2013; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Pendry & Adam, 2007). More recently, researchers have started to investigate some parental factors that may be associated with children’s stress measured via hair cortisol concentration (HCC) (Liu et al., 2020; Ouellette et al., 2015; Simmons et al., 2019; Windhorst et al., 2017). HCC is a novel biomarker for chronic stress (Raul et al., 2004; Sauvé et al., 2007). Unlike salivary and urinary cortisol which reflect acute stress responses, HCC indexes cumulative cortisol exposure, thereby reflecting longer-term/chronic stress reactivity (Stalder & Kirschbaum, 2012; Vanaelst et al., 2012). HCC is less invasive than other physiological stress measures (Bates et al., 2017) and is typically correlated with salivary and urinary cortisol (Alen et al., 2020; Kao et al., 2018). Although HCC is associated with adult difficulties such as depression, anxiety, appraisal of stressful events, and diabetes (Caparros-Gonzalez et al., 2017; Gidlow et al., 2016; Steudte et al., 2011), studies investigating children’s HCC have been inconsistent, with particularly little information about parental factors and HCC. The allostatic load framework (McEwen, 1998) posits that chronic stressors (e.g., parents’ stress and psychopathology), can dysregulate children’s stress-response and self-regulation systems, resulting in negative health outcomes. As chronic stress may have long-term physiological and emotional effects on children, and parent-based interventions can reduce these effects, it is important to identify parental factors that relate to children’s HCC (McMahon, 2006; Schilling et al., 2007; Shonkoff et al., 2012). However, little work has investigated links between parental factors and young children’s HCC, and very little research has included fathers. The goal of this study is to identify whether preschool-aged children’s chronic physiological stress indexed via HCC is associated with mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behavior, psychopathology, and stress.

Several studies have examined mothers’ parenting behavior and children’s HCC. In a sample of 60 mothers and their school-aged daughters, Ouellette et al. (2015) found that negative parenting (hostility, intrusiveness, physical coercion) was associated with children’s HCC only at higher levels of maternal HCC. In 1,776 six-year-old children, maternal harsh parenting and children’s HCC were linked only when mild perinatal adversities occurred (Windhorst et al., 2017). Finally, Simmons et al. (2019) found maternal nurturing was associated with lower HCC in 60 preschool-aged children. These studies suggest that more problematic parenting behavior may be associated with higher HCC levels in children.

Parental psychopathology is another factor that may be related to children’s HCC. Liu et al. (2020) found that elevated caregiver depressive symptoms were associated with increased child HCC in a sample of 154 preschool-aged children. Ferro and Gonzalez (2020) found that children’s HCC mediated the association between parent psychopathology and child psychopathology among 8–17-year-old boys who met criteria for generalized anxiety and oppositional defiant disorders; fathers comprised only 15% of the sample. Parental (primarily maternal) psychopathology has generally been associated with higher levels of children’s HCC, but more data are needed.

Findings with parental perceived stress and HCC are mixed with little work in preschool-aged children. Ling et al. (2020) did not find an overall association between mothers’ perceived stress and preschool-aged children’s HCC. However, mothers’ perceived stress was positively associated with preschoolers’ HCC only when mothers’ HCC was less than 4.1 pg/mg (there was no association when mothers’ HCC was higher). Other studies have not identified associations between mothers’ perceived stress and infants’ HCC (Koenig et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2016; Romero-Gonzalez et al., 2018). No studies, to our knowledge, have assessed fathers’ perceived stress in relation to preschool-aged children’s HCC. It remains unclear whether parents’ perceived stress is related to HCC in preschool-aged children. Given links between stress and HCC, and the potential for parental stress to be a target of prevention/intervention, this construct needs further attention.

Finally, the results of studies assessing children’s HCC and demographic characteristics (e.g., children’s age, race/ethnicity, parental education) have been inconsistent (Anand et al., 2020; Dettenborn et al., 2012; Gunnar et al., 2022; Karlén et al., 2013; Noppe et al., 2014; Rippe et al., 2016; Vaghri et al., 2013; Vliegenthart et al., 2016). Sex differences have also been inconsistent; of 17 studies, five reported higher HCC in boys than girls, one reported higher HCC in younger but not older boys, and 11 found no sex differences (Gray et al., 2018). Given the heterogeneous findings, further research is needed to evaluate potential associations between children’s HCC and demographic characteristics, and how these links may be related to associations with parent constructs.

Although the literature on HCC in children has expanded, many gaps remain. First, studies with preschool-aged children have yielded inconsistent findings across a range of constructs. Second, little work has investigated whether parenting behaviors, parental psychopathology, and parents’ stress are associated with preschool-aged children’s HCC. Further, the few studies that have investigated parental psychopathology focused only on parental depression and not parental anxiety, both of which can be common among parents of young children (Olino et al., 2010). Finally, very few studies investigating children’s HCC have included fathers. To our knowledge, no work has specifically investigated fathers’ parenting behaviors, fathers’ perceived stress, and preschoolers’ HCC.

The aim of this study was to examine associations between preschool-aged children’s physiological stress measured via HCC and mother- and father-reported parenting behavior, psychopathology, and stress. Based on the allostatic load framework (McEwen, 1998), we hypothesized that children’s HCC would be positively associated with more problematic (authoritarian/harsh and permissive/lax) parenting behavior, parent psychopathology (depression and anxiety), and parent stress, as well as interactions between corresponding parent variables. Given potential sex differences in HCC (Gray et al., 2018), we also hypothesized higher levels of HCC for boys than girls. Increasing knowledge of correlates and patterns of HCC in early childhood can advance understanding of risk for psychopathology and other stress-related conditions. Further, identifying parental factors that are associated with children’s HCC can identify targets of prevention and intervention to reduce the likelihood of the impact of stress on children.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

Data were collected as part of a larger study which assessed behaviors relevant to anxiety and mood in young children (Bufferd et al., 2023) . Participants included N = 140 children ages 3–5-years-old (M = 4.24, SD = .75) and their mothers (n = 140) and fathers (n = 98). Participants were recruited from a 20-mile radius around California State University San Marcos through flyers that were sent to local pediatricians, preschools/daycares and community institutions and posted online on parenting group pages on social media. Eligibility criteria included nightly internet access (which was relevant to the larger study), ability to read/speak English, and the parent as the primary caregiver with at least 50% custody of the child. Children were eligible if they did not have any serious medical or developmental disabilities, such as cerebral palsy and autism spectrum disorder. No parents reported endocrine or neurological disorders that could impact cortisol. Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study sample

| Child mean age: years (SD; range) | 4.24 years (.75; 3.19–5.86) |

| Age 3 n (%) | 63 (45.0%) |

| Age 4 n (%) | 51 (36.4%) |

| Age 5 n (%) | 26 (18.6%) |

| Child sex: female n (%) Child race/ethnicity: n (%) |

61 (43.6%) |

| Asian | 7 (5.0%) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 27 (19.3%) |

| Multiracial/Multiethnic/Other | 26 (18.6%) |

| White Childcare/schoola: |

80 (57.1%) |

| Mean number of hours of preschool, daycare, and/or other childcare settings per week (SD; range) Parents’ marital status: n (%) |

17.46 hours (15.16; 0–51) |

| Married or living together Family income: n (%) |

127 (90.7%) |

| <$40,000 | 18 (12.9%) |

| $40,000 - $70,000 | 28 (20.1%) |

| $70,001 - $100,000 | 28 (19.4%) |

| >$100,000 | 66 (47.5%) |

| Mothers’ mean age: years (SD; range) | 34.58 years (5.71; 21–56) |

| Fathers’ mean age: years (SD; range) | 35.86 years (6.05; 22–57) |

| Mothers’ education: n graduated college (%) | 95 (67.9%) |

| Fathers’ education: n graduated college (%) | 54 (55.1%) |

Note: N = 140 mothers and N = 98 fathers; Sex: male = 0, female = 1

0.7% of the sample (n = 1) did not report mean hours of child care; Parents’ not married/living together = 0, Parents’ married/living together = 1.

Mother- and father-reported questionnaires about the child and family were completed electronically at home and during a laboratory visit. During the same laboratory visit, hair samples were taken from children to assess cortisol levels. Informed consent was obtained from parents prior to participation; parents were each financially compensated and children received small toys for their participation. The Institutional Review Board at California State University San Marcos approved the study.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parenting Behavior

Mothers (n = 140) and fathers (n = 92) completed the 37-item Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) (Robinson et al., 2001). This measure shows good psychometric properties with mothers and fathers of preschool-aged children (Olivari et al., 2013). Parents rated the frequency of specific parenting practices they have employed in the previous month on a 5-point Likert scale which ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The PSDQ measures authoritative (high control, high warmth; includes the connection, regulation, and autonomy granting subscales), authoritarian (high control, low warmth; includes the physical coercion, verbal hostility, and non-reasoning/punitive subscales), and permissive (low control, high warmth; includes the indulgence subscale) parenting. See Table 2 for descriptives and alphas.

Table 2.

Zero−order correlations and descriptive statistics for study variables.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Children s HCC | − | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Stressful Life Events | −.05 | − | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Mothers’ Authoritative Parenting | −.01 | .01 | − | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Mothers’ Authoritarian Parenting | .07 | .03 | −.23** | − | |||||||||||||

| 5. Mothers’ Permissive Parenting | .15 | .15 | −.15 | .38** | − | ||||||||||||

| 6. Fathers’ Authoritative Parenting | −.04 | .01 | .36** | −.15 | −.14 | − | |||||||||||

| 7. Fathers’ Authoritarian Parenting | .23* | −.11 | .06 | .30** | .19 | −.35** | − | ||||||||||

| 8. Fathers’ Permissive Parenting | .07 | −.07 | .09 | −.13 | .33** | −.24* | .18 | − | |||||||||

| 9. Mothers’ Anxiety | .07 | .08 | −.17* | .33** | .02 | −.04 | .10 | −.12 | − | ||||||||

| 10. Mothers’ Depression | .05 | .06 | −.22* | .40** | .07 | .03 | .08 | .00 | .69** | − | |||||||

| 11. Fathers’ Anxiety | .01 | .01 | −.09 | .05 | .02 | −.08 | .23* | .13 | .21* | .11 | − | ||||||

| 12. Fathers’ Depression | .00 | .13 | −.11 | .05 | .05 | −.15 | .27** | .17 | .15 | .09 | .73*** | − | |||||

| 13. Mothers’ Perceived Stress | −.09 | .22** | −.15 | .34** | .14 | −.09 | −.06 | −.07 | .53** | .57** | .13 | .19 | − | ||||

| 14. Fathers’ Perceived Stress | −.03 | −.02 | .01 | .11 | .13 | −.13 | .31** | .07 | .12 | .11 | .70 *** | .61*** | .14 | − | |||

| 15. Fathers’ Physical Coercion | .26* | −.10 | .00 | .34** | .11 | −.19 | .69** | −.05 | .23* | .15 | .11 | .13 | .08 | .11 | − | ||

| 16. Fathers’ Verbal Hostility | .16 | −.16 | .13 | .21* | .08 | −.29** | .87** | .19 | .09 | .05 | .29** | .35** | −.10 | .35** | .39** | − | |

| 17. Fathers’ Non-reasoning/Punitive | .08 | −.25* | −.04 | .16 | .27** | −.32** | .70** | .28** | −.07 | .02 | .08 | .09 | −.08 | .19 | .17 | .48** | − |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Descriptives | |||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| M | 2.31 | 1.28 | 63.59 | 19.43 | 10.60 | 59.99 | 20.10 | 11.20 | 35.67 | 13.09 | 37.09 | 12.87 | 14.71 | 14.37 | 6.12 | 7.49 | 6.57 |

| SD | .93 | 1.36 | 6.14 | 4.56 | 2.98 | 7.93 | 5.04 | 3.20 | 12.78 | 5.05 | 12.12 | 5.28 | 5.61 | 6.84 | 2.19 | 2.69 | 1.87 |

| Min - Max | .18–5.76 | 0–7 | 47–75 | 12–32 | 6–18 | 36–75 | 12–39 | 6–21 | 21–84 | 8–32 | 21–70 | 8–26 | 3–31 | 0–33 | 4–14 | 4–16 | 4–12 |

| Alpha | - | - | .85 | .77 | .70 | .88 | .79 | .72 | .94 | .92 | .93 | .93 | .86 | .91 | .67 | .76 | .46 |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001; HCC = hair cortisol concentration; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; Min = minimum; Max = maximum.

2.2.2. Parental Psychopathology

Mothers (n = 140) and fathers (n = 92) completed the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression short form and the PROMIS Anxiety form. For each measure, respondents rated the frequency of their symptoms in the past week on a 5-point Likert scale which ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Responses were summed, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms. See Table 2 for descriptives and alphas.

2.2.3. Parents’ Perceived Stress

Mothers (n = 140) and fathers (n = 90) completed the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983). This is a 10-item self-report questionnaire that measures respondents’ perception of chronic stress and the degree to which they view their lives as unpredictable and uncontrollable. Mothers and fathers rated how often they felt or thought a certain way in the past month on a 5-point Likert scale which ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). See Table 2 for descriptives and alphas.

2.2.4. Stressful Life Events

The stressful life events items from the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) (Egger et al., 1999) were used. The PAPA is a valid and reliable measure of stressful life events and psychopathology in preschool-aged children (Dougherty, Tolep, et al., 2013; Egger et al., 1999). Mothers (n = 139) rated the frequency of 31 stressful events their child and family experienced in the past 6 months. We summed the total number of stressful life events endorsed and included this variable as a covariate to identify specific associations between parent variables and children’s HCC beyond any effects of family stressors. See Table 2 for descriptives and alphas.

2.2.5. Children’s Hair Cortisol

Parents were asked to not cut or dye children’s hair before the sample collection and to not apply gels or hairspray on the day of the sample collection. During the laboratory visit, a research staff member cut 80–100 strands of the children’s hair from the posterior vertex region of their scalp using haircutting scissors or thinning shears. We aimed to collect 3cm samples to assess cortisol activity over the previous 3 months. For hair samples that were less than 3cm (n = 14; 10.0%), we calculated the amount of cortisol per millimeter of hair and used this value to estimate the amount of cortisol that would be in 3cm of the participant’s hair.

Hair samples were wrapped in foil for storage. Hair was washed twice in isopropanol and dried for 7 days. Hair was then snap frozen with liquid nitrogen and ground to a powder using a Retsch ball mill for 10 minutes at 25 Hz. The powdered hair (~20–50 mg) was weighed and extracted in HPLC-grade methanol at room temperature for 24 hours with slow rotation. Following extraction, the solution was transferred to a 2ml microcentrifuge tube and spun for 120s in a microcentrifuge at approximately 20,000g. The supernatant was removed, placed into a new microcentrifuge tube, and dried in a fume hood for 4 days. Extracts were reconstituted with assay buffer based on the amount of supernatant recovered, and cortisol levels determined using a commercial high sensitivity enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit according to manufacturer’s directions (Salimetrics, LLC). An internal control consisting of a large pool of previously ground mixed hair was extracted and run on each plate for determination of inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) (D’Anna-Hernandez et al., 2011). Inter-assay CV was 5.77% and intra-assay CV was less than 3%. Although 144 children provided hair samples, 4 fell below the lower assay limit (0.019ug/dl) and were not included in the analyses. See Table 2 for descriptives.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 27. Data were screened for outliers and normality was assessed. Hair cortisol concentrations were converted to pg/mg and were log10 transformed to obtain a normal distribution. The log-transformed HCC scores were used in all analyses. Zero-order correlations were computed among all study and demographic variables to determine significant relations and potential covariates. Any significant associations between categorical demographic variables and HCC were examined with t-tests. If significant associations between children’s HCC and demographic variables were identified, demographic variables were included as covariates. The significant association identified between children’s HCC and fathers’ authoritarian parenting (see below) was explored further by examining correlations between facets of authoritarian parenting (physical coercion, verbal hostility, and non-reasoning/punitive subscales) and children’s HCC.

To examine unique associations between parent variables and children’s HCC, parent predictors that were significant in bivariate analyses were entered into the same multivariate linear regression model with covariates, including significant demographic variables, stressful life events, and other parent variables. In addition, to examine potential interactions between corresponding parent/co-parent variables in relation to children’s HCC, moderation analyses were performed using PROCESS version 4 (Hayes, 2017) for SPSS. Finally, moderation analyses were run to examine whether sex moderated the relationships between HCC and parent variables. Statistical significance was set at p < .05. Although multiple analyses were conducted, we did not correct for multiple tests to attempt to identify possible links that have not yet been tested in this research area. Findings need to be replicated in other samples.

3. Results

Table 1 includes the demographic characteristics of the sample and Table 2 includes descriptives for all study variables. Children’s HCC was not correlated with child age (r = −.14, p = .105), weekly childcare/school hours (r = .074, p = .390), mothers’ education (r = −.03, p = .747), fathers’ education (r = .05, p = .598) or family income (r = −.05, p = .600). Children’s HCC levels were significantly correlated with sex (r = −.17, p = .047) and race/ethnicity (r = −.17, p = .044). HCC levels were higher in boys compared to girls (boys’ HCC M = 2.45, SD = .89; girls’ HCC M = 2.13, SD = .96; t (138) = 2.00, p = .047). HCC levels were higher in children of color (Asian, Hispanic/Latinx, Multiracial/Multiethnic) compared to white children (children of colors’ HCC M = 2.49, SD = .74; white children’s HCC M = 2.17, SD = 1.03; t (138) = 2.03, p = .044). Given that studies have shown associations between sex and children’s HCC, and race/ethnicity and children’s HCC, and these findings are significant in our study, sex and race/ethnicity were included as covariates in regression analyses.

Zero-order correlations for all study variables are provided in Table 2. Children’s HCC was not significantly related to mothers’ and fathers’ anxiety and depression (Table 2) or mothers’ and fathers’ perceived stress (Table 2). In addition, children’s HCC was not associated with mothers’ authoritative, authoritarian, or permissive parenting. Children’s HCC was not associated with fathers’ authoritative or permissive parenting. However, there was a significant association between children’s HCC and fathers’ authoritarian parenting (r = .23, p = .028).

To further explore this significant relationship between children’s HCC and fathers’ authoritarian parenting, we examined facets of authoritarian parenting, including physical coercion (M = 6.12, SD = 2.19, Min = 4.00, Max = 14.00), verbal hostility (M = 7.49, SD = 2.69, Min = 4.00, Max = 16.00), and non-reasoning/punitive parenting (M = 6.57, SD = 1.87, Min = 4.00, Max = 12.00) and children’s HCC. Children’s HCC was not associated with fathers’ verbal hostility (r = .16, p = .136) or fathers’ non-reasoning/punitive behaviors (r = .08, p = .428). However, children’s HCC was positively associated with fathers’ physical coercion (r = .26, p = .013).1 Regression analyses (Table 3) showed that fathers’ authoritarian parenting and physical coercion continued to be associated with children’s HCC when race/ethnicity, sex and stressful life events were included as covariates. Further, fathers’ physical coercion remained significantly associated with children’s HCC after adding the parent variables (fathers’ depression, fathers’ anxiety, and fathers’ perceived stress) to the regression model along with race/ethnicity, sex and stressful life events; this finding demonstrates the unique relation between fathers’ physical coercion and children’s HCC even when accounting for related constructs (fathers’ psychopathology and stress).

Table 3.

Regression analyses with fathers’ authoritarian parenting and physical coercion and children’s HCC.

| Model | Model Predictors & Covariates | B | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1 | Fathers’ Authoritarian Parenting | .04 | .02 | .23 | 2.25 | .027 |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.39 | .20 | −.20 | −1.91 | .059 | |

| Sex | −.36 | .20 | −.19 | −1.81 | .074 | |

| Stressful Life Events | −.04 | .08 | −.05 | −.51 | .615 | |

|

| ||||||

| 2 | Fathers’ Physical Coercion | .10 | .04 | .24 | 2.36 | .020 |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.28 | .20 | −.15 | −1.37 | .174 | |

| Sex | −.40 | .20 | −.21 | −2.03 | .046 | |

| Stressful Life Events | −.03 | .08 | −.04 | −.37 | .710 | |

|

| ||||||

| 3 | Fathers’ Physical Coercion | .13 | .05 | .27 | 2.57 | .012 |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.30 | .21 | −.16 | −1.45 | .150 | |

| Sex | −.43 | .21 | −.22 | −2.02 | .047 | |

| Stressful Life Events | −.04 | .08 | −.05 | −.46 | .649 | |

| Fathers’ Perceived Stress | −.02 | .02 | −.14 | −.94 | .348 | |

| Fathers’ Anxiety | .01 | .01 | .13 | .75 | .456 | |

| Fathers’ Depression | −.003 | .03 | −.02 | −.13 | .900 | |

Note: HCC = hair cortisol concentration; Sex: male = 0, female = 1; Race/ethnicity: children of color = 0, white children = 1; B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error; β = standardized coefficient.

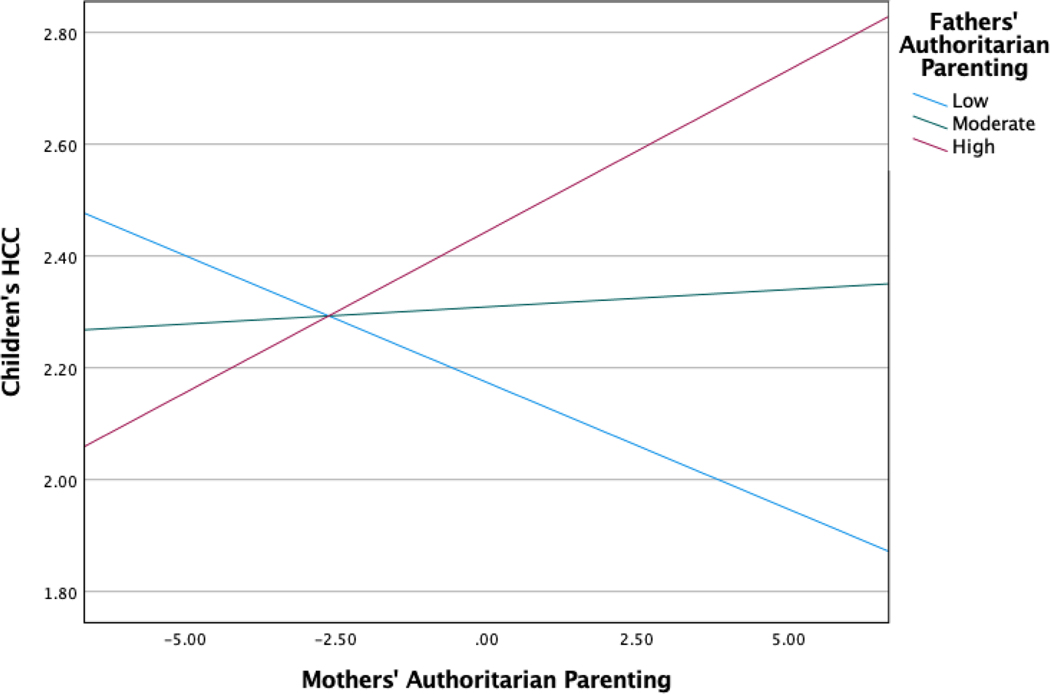

To examine potential interactions between corresponding parent/co-parent variables in relation to children’s HCC, moderation analyses were run with race/ethnicity, sex and stress included as covariates. There was a significant interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC (B = .010, SE = .004, t = 2.64, p = .009, 95% CI = .003-.018) (Figure 1). Specifically, the relation with children’s HCC and authoritarian parenting was significant only when both mothers and fathers reported higher levels of authoritarian parenting (B = .058, SE = .026, t = 2.21, p = .030, 95% CI = .006-.110); there was no significant relation with children’s HCC when both mothers and fathers reported lower levels of authoritarian parenting (B = −.045, SE = .033, t = −1.39, p = .168, 95% CI = −.110-.020). No other interactions between corresponding parenting (authoritative and permissive), parental psychopathology (anxiety and depression), or perceived stress variables were significant (see Table 4).

Figure 1.

Interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC

Table 4.

Interaction models with parenting behavior, parental psychopathology, perceived stress and children’s HCC.

| Children’s HCC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent variables and covariates | B | SE | t | p | 95% LLCI, 95% ULCI |

| Authoritarian Parenting | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | −.437 | .199 | −2.197 | .031 | −.833, −.042 |

| Sex | −.469 | .195 | −2.402 | .018 | −.858, −.081 |

| Stressful Life Events | −.028 | .077 | −.363 | .717 | −.181, .125 |

| Mothers’ Authoritarian Parenting | .006 | .022 | .277 | .783 | −.038, .051 |

| Fathers’ Authoritarian Parenting | .026 | .019 | 1.376 | .172 | −.012, .064 |

| Mothers’ Authoritarian Parenting x Fathers’ Authoritarian Parenting | .010 | .004 | 2.652 | .009 | .003, .018 |

| Authoritative Parenting | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | −.372 | .208 | −1.790 | .077 | −.784, .041 |

| Sex | −.440 | .200 | −2.193 | .031 | −.838, −.041 |

| Stressful Life Events | −.072 | .080 | −.896 | .373 | −.231, .087 |

| Mothers’ Authoritative Parenting | .005 | .017 | .291 | .772 | −.029, .039 |

| Fathers’ Authoritative Parenting | −.004 | .013 | −.290 | .773 | −.030, .022 |

| Mothers’ Authoritative Parenting x Fathers’ Authoritative Parenting | −.002 | .002 | −.753 | .453 | −.006, .003 |

| Permissive Parenting | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | −.384 | .213 | −1.804 | −1.804 | −.806, .039 |

| Sex | −.411 | .201 | −2.042 | .044 | −.811, −.011 |

| Stressful Life Events | −.071 | .081 | −.884 | .379 | −.232, .089 |

| Mothers’ Permissive Parenting | .037 | .036 | 1.032 | .305 | −.034, .109 |

| Fathers’ Permissive Parenting | .015 | .033 | .450 | .654 | −.050, .079 |

| Mothers’ Permissive Parenting x Fathers’ Permissive Parenting |

.002 | .011 | .159 | .874 | −.021, .024 |

| Psychopathology | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | −.422 | .207 | −2.038 | .045 | −.833, −.011 |

| Sex | −.523 | .205 | −2.545 | .013 | −.930, −.115 |

| Stressful Life Events | −.070 | .079 | −.879 | .382 | −.227, .088 |

| Mothers’ Anxiety | −.001 | .010 | −.119 | .906 | −.020, .018 |

| Fathers’ Anxiety | .004 | .008 | .420 | .675 | −.013, .020 |

| Mothers’ Anxiety x Fathers’ Anxiety |

.001 | .001 | 1.464 | .147 | .000, .002 |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.374 | .208 | −1.793 | .076 | −.787, .040 |

| Sex | −.447 | .201 | −2.228 | .028 | −.845, −.049 |

| Stressful Life Events | −.070 | .083 | −.839 | .404 | −.234, .095 |

| Mothers’ Depression | .013 | .020 | .656 | .514 | −.026, .052 |

| Fathers’ Depression | .007 | .019 | .348 | .729 | −.031, .045 |

| Mothers’ Depression x Fathers’ Depression |

−.001 | .004 | −.194 | .846 | −.009, .007 |

| Stress | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | −.368 | .208 | −1.772 | .080 | −.780, .045 |

| Sex | −.424 | .212 | −1.995 | .049 | −.846, −.002 |

| Stressful Life Events | −.077 | .084 | −.913 | .364 | −.243, .090 |

| Mothers’ Perceived Stress | −.016 | .021 | −.784 | .435 | −.057, .025 |

| Fathers’ Perceived Stress | −.001 | .015 | −.042 | .967 | −.030, .029 |

| Mothers’ Perceived Stress x Fathers’ Perceived Stress |

.004 | .003 | 1.365 | .176 | −.002, .010 |

Note: HCC = hair cortisol concentration; Sex: male = 0, female = 1; Race/ethnicity: children of color = 0, white children = 1; B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error; LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; ULCI = upper limit confidence interval.

Moderation analyses showed that the relationships between HCC and the parent variables were not moderated by sex (p > .05) (the results of these interactions are available upon request).

4. Discussion

The current study sought to examine associations between preschool-aged children’s physiological stress measured via hair cortisol concentration (HCC), and maternal and paternal parenting behavior, psychopathology, and stress. We also sought to evaluate sex differences in HCC during preschool age, and whether sex moderates the relationship between children’s HCC and the parenting variables. Our findings indicated that children’s HCC was positively associated with fathers’ authoritarian parenting, and, more specifically, fathers’ report of physical coercion. This association remained significant even after accounting for race/ethnicity, sex, stressful life events, fathers’ psychopathology, and fathers’ perceived stress. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show a relation between fathers’ physical parenting practices and physiological child stress via HCC during preschool age. Our results also showed an interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC, and significant sex and race/ethnicity differences, with higher HCC levels in boys than girls and in children of color than white children, respectively.

As hypothesized, children’s HCC was positively associated with fathers’ authoritarian parenting, which suggests that children have higher cortisol levels when their fathers engage in harsher parenting behaviors. After identifying this relation between children’s HCC and fathers’ authoritarian parenting, we were interested in the specific facets of fathers’ authoritarian parenting that might be associated with children’s HCC. Only fathers’ report of physical coercion (i.e., physical punishment, spanking, grabbing, slapping) was associated with higher levels of children’s HCC. This finding was robust as it remained significant after accounting for child race/ethnicity, sex, stressful life events, fathers’ anxiety, fathers’ depression, and fathers’ perceived stress. Our finding that fathers’ physical coercion was associated with children’s HCC is consistent with the large literature that links parental physical coercion, spanking, and corporal punishment to a range of detrimental outcomes in children, such as aggression, antisocial behavior, externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, low self-esteem, decreased cognitive performance, and negative parent-child relationships (Ferguson, 2013; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Pinquart, 2017). Pinquart (2017) conducted a meta-analysis on parenting behavior and child externalizing problems in 1,435 studies across 1,053,288 youth (Mage = 10.70 years, SD = 4.61 years). Harsh control and psychological control, facets of authoritarian parenting, showed the strongest associations with youth’s externalizing behavior problems compared to other parenting dimensions. To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate and identify this relation between fathers’ physical coercion and a physiological marker of stress as indexed by HCC in preschool-aged children. This finding should be replicated. Children’s HCC could mediate the link between parental physical coercion in early childhood and problematic outcomes later in childhood and beyond, which would be consistent with the allostatic load framework (McEwen, 1998).

We found a significant interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC: when both mothers and fathers reported engaging in higher levels of authoritarian parenting behaviors, children’s HCC levels were elevated. This finding highlights that maternal authoritarian parenting is only associated with children’s HCC in the context of paternal authoritarian parenting; when fathers do not report higher levels of authoritarian parenting, there is no link between maternal authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC. Although other studies have not investigated this specific interaction between parenting and children’s HCC to our knowledge, work in other areas has identified overlap between maternal and paternal harsh parenting and children’s externalizing behaviors. Mendez et al. (2016) found that mothers’ harsh parenting moderated the relationship between fathers’ corporal punishment and toddlers’ externalizing behaviors. There were no interactions between other corresponding parent variables that were not associated with children’s HCC (i.e., authoritative and permissive parenting, parental psychopathology, and perceived stress).

Unlike the findings with fathers and findings in other studies, mothers’ authoritarian parenting alone was not associated with children’s HCC. To our knowledge, only Simmons et al. (2019) and Ouellette et al. (2015) examined the relationship between children’s HCC and parenting behavior. However, both studies included only mothers’ (and not fathers’) parenting behavior and only Simmons et al. (2019) included preschool-aged children. Additionally, while we examined the three PSDQ dimensions separately, Ouellette et al. (2015) used an aggregate measure that included PSDQ permissive and authoritarian parenting dimensions, along parent-child interaction tasks, and Simmons et al. (2015) used different parent questionnaires. Simmons et al. (2019) and Ouellette et al. (2015) found that less positive and more negative parenting were associated with children’s HCC. Numerous studies have documented that children may be differentially affected by mothers and fathers, possibly due to differences in the quantity and quality of parent-child interactions. For some families, mothers may spend more time with children, whereas fathers may be more involved in disciplining children. Bronte-Tinkew et al. (2006) reported that fathers’ authoritarian behavior contributed to adolescents’ delinquency, but mothers’ authoritarian behavior did not. Parisette-Sparks et al. (2017) reported that fathers’ permissive parenting predicted shame and guilt in preschool-aged children, but mothers’ permissive parenting did not. Furthermore, Hoeve et al. (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of 161 articles and concluded that children aged 1–18 years old who were poorly supported by their fathers (i.e., low warmth and responsiveness, rejection) had higher levels of delinquency than children who were poorly supported by their mothers. In our study, children’s HCC was not associated with other problematic parenting behaviors (high maternal and paternal permissive parenting; low maternal and paternal authoritative parenting) reported by fathers or mothers.

We expected mothers’ and fathers’ psychopathology to be positively associated with children’s HCC, but we did not find an association between parents’ anxiety and children’s HCC (which to our knowledge has not been previously investigated in preschool-aged children), and unlike Liu et al. (2020), we did not find an association between parents’ depression and preschool-aged children’s HCC. However, Liu and colleagues used a measure of postpartum depression, whereas we assessed more general depressive symptoms. Furthermore, Liu et al. (2020) included a high-risk, low-income sample, whereas we included a community sample. Persistent stressors in higher-risk samples, in this case low-income, may increase the impact of parents’ psychopathology on preschool-aged children.

We also expected mothers’ and fathers’ perceived stress to be associated with children’s HCC, but the data did not support this hypothesis. This null finding is consistent with other studies (Koenig et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2016; Romero-Gonzalez et al., 2018). Koenig et al. (2018), Liu et al. (2016) and Romero-Gonzalez et al. (2018) did not find an association between mothers’ responses on the PSS postpartum and infants’ HCC. Ling et al. (2020) only found an association under specific conditions when mothers’ HCC was low. Overall, our findings add to the growing literature that has not identified a general link between parents’ perceived stress and HCC in preschool-aged children. However, it remains unclear why this expected association has not been identified across most studies. It may be that this relation is more nuanced and varies based on many factors such as parents’ HCC, perceived distress, and perceived coping.

Given that fathers’ authoritarian parenting was positively associated with fathers’ anxiety, depression, and perceived stress, it may be that fathers with more anxiety and depression, and higher stress levels engaged in harsher parenting practices than other fathers; nevertheless, only parenting practices associated with children’s HCC. It is possible that parenting practices reflect a more proximal risk factor impacting stress processes in children compared to parents’ symptoms of anxiety and depression. Longitudinal work should investigate potential mediational processes among these variables. Conversely, mothers’ anxiety and depression were positively associated with mothers’ authoritative and authoritarian parenting, but were not associated with mothers’ permissive parenting. Therefore, based on the self-report measures in the present study, fathers’ parenting behaviors may have a more direct association with children’s HCC than the other parent constructs we assessed.

Consistent with other studies (Gerber et al., 2017; Gray et al., 2018; Rippe et al., 2016), we identified higher levels of HCC in boys versus girls. Sex differences in the regulation of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis stress responses may reflect differences in circulating gonadal steroids, corticosteroid binding globulin, and/or in the structure of the limbic region of the brain (which is involved in the processing of psychological stress) in biological males and females (Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005), which may explain sex differences in some diseases (Kajantie & Phillips, 2006; Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005); diseases associated with higher HCC (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes) tend to be more prevalent in males whereas diseases associated with lower HCC (e.g., autoimmune diseases) tend to be more prevalent in females (Whitacre, 2001). Our findings also showed that children from racially and ethnically minoritized groups had higher HCC levels than children from the racial/ethnic majority group. Other studies have identified similar racial and ethnic differences in HCC in preschool-aged children (Anand et al., 2020; Gunnar et al., 2022; Kao et al., 2019; Ling et al., 2019). This difference may be explained by the higher level of systemic stress exposure by children in minoritized populations (Anand et al., 2020).

Our study had many strengths, including the use of a community sample and a sample size that was consistent with (Gidlow et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2020) or exceeded similar studies (Ferro & Gonzalez, 2020; Ling et al., 2020; Ouellette et al., 2015). Additionally, our effect size was comparable to those of other studies. Across studies with preschool-aged children that investigated HCC and parenting variables (parenting behavior, psychopathology, stress) and reported effect sizes, values ranged from .07 to .23 (Mean = .16, Median = .17) (Ling et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Simmons et al., 2019). Our effect sizes with HCC and parenting variables ranged from .01 to .26. Furthermore, to our knowledge this is the first study to include fathers in the examination of a range of parental factors and preschool-aged children’s HCC.

However, this study also had some limitations. First, the key finding in the present study linking fathers’ use of physical coercion and children’s HCC was based on a post-hoc analysis conducted to further explore the association between authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC. We chose to report this finding given that it remained significant even when accounting for a wide range of covariates (sex, stressful life events, and fathers’ anxiety, depression, and perceived stress) and makes an important contribution to the literature on physical punishment and detrimental effects on children. Nevertheless, although this finding was robust in our study, replication is needed. Second, effect sizes at .23 and larger between HCC and parenting variables were detected as significant in our sample. There may be smaller effect sizes that we failed to detect based on our sample size. Third, the HCC assessed represented 3 months of cortisol exposure whereas the PSDQ and the PSS measured parenting behavior and perceived stress, respectively, in the past month, and the PROMIS Depression and Anxiety forms measured psychopathology in the past week. Although this issue is not unique to our study, it is possible that the relation between these measures and HCC would be stronger if they reflected the same time frame. However, as depression and anxiety are often chronic, it is possible that the parental psychopathology measures reflect typical functioning despite assessing symptoms only in the past week. Fourth, all measures of parenting included parental self-report measures; observations of parenting behavior could be a useful addition to compensate for the limitations of self-report. Fifth, we classified children’s race/ethnicity into “children of color” and “white children” to examine differences between racially and ethnically minoritized groups and the racial/ethnic majority group to ensure we had enough children in each group for analysis. However, grouping racially and ethnically minoritized children into one category does not acknowledge the many differences among racial and ethnic subgroups, so future studies should consider using a larger racially and ethnically diverse sample. Additionally, as socioeconomic status (SES) may, in part, better account for differences between racial and ethnic groups, future studies should include SES in analyses. Sixth, we did not collect data on the amount of time that mothers and fathers each spent with their children; these data may help explain the differences in the influence of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behavior and psychopathology on their children’s HCC. Relatedly, although we investigated interactions between maternal and paternal variables, nesting between parents/within families may also account for relationships between HCC and parenting variables. Finally, our sample included families with mothers and fathers; studies should include more diverse family types to examine whether these findings would generalize.

5. Conclusion

The current study shows a relation between a physiological measure of stress (i.e., HCC) in preschool-aged children and physical parenting practices. These findings contribute to the large literature that links physical parenting practices with problematic outcomes in children. Our findings also provide evidence for race/ethnicity and sex differences in HCC in preschool-aged children. Future studies should follow-up with samples to investigate associations between parenting variables, children’s HCC, and other child outcomes over time, collect hair samples from parents, and utilize additional measures of stress (e.g., parenting stress measures).

Highlights.

Higher HCC in boys than girls, and children of color compared to white children

Children’s HCC was positively associated with fathers’ authoritarian parenting

Children’s HCC was positively associated with fathers’ physical coercion

Interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ authoritarian parenting and children’s HCC

Children’s HCC was not linked to parents’ anxiety, depression or perceived stress

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15MH106885 (Bufferd). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations of Competing Interest: None

Children’s HCC was not associated with mothers’ physical coercion (r = .05, p = .530), mothers’ verbal hostility (r = .03, p = .701), or mothers’ non-reasoning/punitive (r = .07, p = .443).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alen NV, Hostinar CE, Mahrer NE, Martin SR, Guardino C, Shalowitz MU, Ramey SL, & Schetter CD (2020). Prenatal maternal stress and child hair cortisol four years later: evidence from a low-income sample. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 117, 104707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand KJ, Rovnaghi CR, Rigdon J, Qin F, Tembulkar S, Murphy LE, Barr DA, Gotlib IH, & Tylavsky FA (2020). Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with hair cortisol concentrations in preschool children. Pediatric Research, 87(6), 1119–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates R, Salsberry P, & Ford J.(2017). Measuring stress in young children using hair cortisol: The state of the science. Biological Research for Nursing, 19(5), 499–510. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6775674/pdf/10.1177_1099800417711583.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Moore KA, & Carrano J.(2006). The father-child relationship, parenting styles, and adolescent risk behaviors in intact families. Journal of Family Issues, 27(6), 850–881. [Google Scholar]

- Bufferd SJ, Olino TM, & Dougherty LR (2023). Quantifying severity of preschool-aged children’s internalizing behaviors: A daily diary analysis. Assessment, 30(1), 190–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caparros-Gonzalez RA, Romero-Gonzalez B, Strivens-Vilchez H, Gonzalez-Perez R, Martinez-Augustin O, & Peralta-Ramirez MI (2017). Hair cortisol levels, psychological stress and psychopathological symptoms as predictors of postpartum depression. PloS One, 12(8), e0182817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R.(1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna-Hernandez KL, Ross RG, Natvig CL, & Laudenslager ML (2011). Hair cortisol levels as a retrospective marker of hypothalamic–pituitary axis activity throughout pregnancy: comparison to salivary cortisol. Physiology & Behavior, 104(2), 348–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettenborn L, Tietze A, Kirschbaum C, & Stalder T.(2012). The assessment of cortisol in human hair: associations with sociodemographic variables and potential confounders. Stress, 15(6), 578–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Smith VC, Olino TM, Dyson MW, Bufferd SJ, Rose SA, & Klein DN (2013). Maternal psychopathology and early child temperament predict young children’s salivary cortisol 3 years later. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 41(4), 531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Tolep MR, Bufferd SJ, Olino TM, Dyson M, Traditi J, Rose S, Carlson GA, & Klein DN (2013). Preschool anxiety disorders: Comprehensive assessment of clinical, demographic, temperamental, familial, and life stress correlates. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(5), 577–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger H, Ascher BH, & Angold A.(1999). Preschool age psychiatric assessment (PAPA). Durham (North Carolina): Duke University Medical Center. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ (2013). Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro MA, & Gonzalez A.(2020). Hair cortisol concentration mediates the association between parent and child psychopathology. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 114, 104613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber M, Endes K, Brand S, Herrmann C, Colledge F, Donath L, Faude O, Pühse U, Hanssen H, & Zahner L.(2017). In 6-to 8-year-old children, hair cortisol is associated with body mass index and somatic complaints, but not with stress, health-related quality of life, blood pressure, retinal vessel diameters, and cardiorespiratory fitness. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 76, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, & Grogan-Kaylor A.(2016). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(4), 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidlow CJ, Randall J, Gillman J, Silk S, & Jones MV (2016). Hair cortisol and self-reported stress in healthy, working adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 63, 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray N, Dhana A, Van Der Vyver L, Van Wyk J, Khumalo N, & Stein D.(2018). Determinants of hair cortisol concentration in children: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 87, 204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M, & Quevedo K.(2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Haapala J, French SA, Sherwood NE, Seburg EM, Crain AL, & Kunin-Batson AS (2022). Race/ethnicity and age associations with hair cortisol concentrations among children studied longitudinally from early through middle childhood. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 144, 105892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, Van der Laan PH, Smeenk W, & Gerris JR (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 749–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajantie E, & Phillips DI (2006). The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31(2), 151–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao K, Doan SN, St. John AM, Meyer JS, & Tarullo AR (2018). Salivary cortisol reactivity in preschoolers is associated with hair cortisol and behavioral problems. Stress, 21(1), 28–35. 10.1080/10253890.2017.1391210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao K, Tuladhar CT, Meyer JS, & Tarullo AR (2019). Emotion regulation moderates the association between parent and child hair cortisol concentrations. Developmental psychobiology, 61(7), 1064–1078. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7980303/pdf/nihms-1681274.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlén J, Frostell A, Theodorsson E, Faresjö T, & Ludvigsson J.(2013). Maternal influence on child HPA axis: a prospective study of cortisol levels in hair. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1333–e1340. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/132/5/e1333.long [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig AM, Ramo-Fernández L, Boeck C, Umlauft M, Pauly M, Binder EB, Kirschbaum C, Gündel H, Karabatsiakis A, & Kolassa I-T (2018). Intergenerational gene× environment interaction of FKBP5 and childhood maltreatment on hair steroids. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 92, 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, & Kirschbaum C.(2005). Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: a review. Biological psychology, 69(1), 113–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling J, Robbins LB, & Xu D.(2019). Food security status and hair cortisol among low-income mother-child dyads. Western journal of nursing research, 41(12), 1813–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling J, Xu D, Robbins LB, & Meyer JS (2020). Does hair cortisol really reflect perceived stress? Findings from low-income mother-preschooler dyads. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 111, 104478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Fink G, Brentani H, & Brentani A.(2020). Caregiver depression is associated with hair cortisol in a low-income sample of preschool-aged children. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 117, 104675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Snidman N, Leonard A, Meyer J, & Tronick E.(2016). Intra‐individual stability and developmental change in hair cortisol among postpartum mothers and infants: Implications for understanding chronic stress. Developmental psychobiology, 58(4), 509–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York academy of sciences, 840(1), 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ (2006). Parent training interventions for preschool-age children. Encyclopedia on early childhood development, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez M, Durtschi J, Neppl TK, & Stith SM (2016). Corporal punishment and externalizing behaviors in toddlers: The moderating role of positive and harsh parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(8), 887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noppe G, Van Rossum EF, Koper JW, Manenschijn L, Bruining GJ, De Rijke YB, & Van Den Akker EL (2014). Validation and reference ranges of hair cortisol measurement in healthy children. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 82(2), 97–102. https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/362519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Dyson MW, Rose SA, & Durbin CE (2010). Temperamental emotionality in preschool-aged children and depressive disorders in parents: associations in a large community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(3), 468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivari MG, Tagliabue S, & Confalonieri E.(2013). Parenting style and dimensions questionnaire: A review of reliability and validity. Marriage & Family Review, 49(6), 465–490. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette SJ, Russell E, Kryski KR, Sheikh HI, Singh SM, Koren G, & Hayden EP (2015). Hair cortisol concentrations in higher- and lower-stress mother-daughter dyads: A pilot study of associations and moderators. Developmental Psychobiology, 57(5), 519–534. 10.1002/dev.21302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisette-Sparks A, Bufferd SJ, & Klein DN (2017). Parental predictors of children’s shame and guilt at age 6 in a multimethod, longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(5), 721–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendry P, & Adam EK (2007). Associations between parents’ marital functioning, maternal parenting quality, maternal emotion and child cortisol levels. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(3), 218–231. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M.(2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raul J-S, Cirimele V, Ludes B, & Kintz P.(2004). Detection of physiological concentrations of cortisol and cortisone in human hair. Clinical biochemistry, 37(12), 1105–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippe RC, Noppe G, Windhorst DA, Tiemeier H, van Rossum EF, Jaddoe VW, Verhulst FC, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, & van den Akker EL (2016). Splitting hair for cortisol? Associations of socio-economic status, ethnicity, hair color, gender and other child characteristics with hair cortisol and cortisone. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 66, 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, & Hart CH (2001). The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ). Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques, 3, 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Gonzalez B, Caparros-Gonzalez RA, Gonzalez-Perez R, Delgado-Puertas P, & Peralta-Ramirez MI (2018). Newborn infants’ hair cortisol levels reflect chronic maternal stress during pregnancy. PloS One, 13(7), e0200279. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6034834/pdf/pone.0200279.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé B, Koren G, Walsh G, Tokmakejian S, & Van Uum SH (2007). Measurement of cortisol in human hair as a biomarker of systemic exposure. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, E183–E191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, & Gore S.(2007). Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, Pascoe J, Wood DL, Child, C. o. P. A. o., Health, F., Committee on Early Childhood, A., & Care D.(2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JG, Azpitarte F, Roost FD, Dommers E, Allen NB, Havighurst S, & Haslam N.(2019). Correlates of hair cortisol concentrations in disadvantaged young children. Stress and Health, 35(1), 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, & Kirschbaum C.(2012). Analysis of cortisol in hair–state of the art and future directions. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26(7), 1019–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steudte S, Stalder T, Dettenborn L, Klumbies E, Foley P, Beesdo-Baum K, & Kirschbaum C.(2011). Decreased hair cortisol concentrations in generalised anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Research, 186(2–3), 310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghri Z, Guhn M, Weinberg J, Grunau RE, Yu W, & Hertzman C.(2013). Hair cortisol reflects socio-economic factors and hair zinc in preschoolers. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(3), 331–340. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4821190/pdf/nihms772330.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanaelst B, Huybrechts I, Bammann K, Michels N, De Vriendt T, Vyncke K, Sioen I, Iacoviello L, Günther K, & Molnar D.(2012). Intercorrelations between serum, salivary, and hair cortisol and child‐reported estimates of stress in elementary school girls. Psychophysiology, 49(8), 1072–1081. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliegenthart J, Noppe G, Van Rossum E, Koper J, Raat H, & Van den Akker E.(2016). Socioeconomic status in children is associated with hair cortisol levels as a biological measure of chronic stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 65, 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitacre CC (2001). Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nature immunology, 2(9), 777–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windhorst DA, Rippe RC, Mileva‐Seitz VR, Verhulst FC, Jaddoe VW, Noppe G, van Rossum EF, van den Akker EL, Tiemeier H, & van IJzendoorn MH (2017). Mild perinatal adversities moderate the association between maternal harsh parenting and hair cortisol: Evidence for differential susceptibility. Developmental Psychobiology, 59(3), 324–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]