Abstract

Apple cultivation is one of the most significant means of subsistence in the Kashmir region of the northwestern Himalayas. It is considered as the backbone of the region's economy. Apple cultivation in the region is dominated by a late maturing cultivar “Red Delicious” which usually on maturity causes glut in the market. In order to bring new cultivars in the cultivation, and to expand the maturity season, it is necessary to evaluate the new cultivars on fruit physico-chemical attributes which ultimately decide the market rates before recommending to farmers for cultivars adoption. Therefore, the current study was carried out to evaluate thirteen apple cultivars on physico-chemical attributes over two years, 2017 and 2018 under agro-climatic conditions of Kashmir region The results revealed that cultivars differed significantly in terms of physico-chemical properties. Cultivars with the highest and lowest values for initial fruit set, fruit drop, final fruit retention, and fruit firmness in 2017 did not follow the same trend in 2018. During 2017 and 2018, cultivar Mollie's Delicious possessed the highest fruit length (72.39 mm and 81.45 mm), fruit diameter (81.18 mm and 84.14 mm), and fruit weight (205.85 g and 247.16 g), whereas cultivar Baleman's Cider had the lowest values (50.76 mm and 52.83 mm, 60.10 mm and 62.08 mm, and 71.46 g and 86.94 g), respectively. The harvesting dates were quite spread out during both years of study. Cultivar Mollie's Delicious was harvested the earliest in both years, on August 5th, 2017 and August 8th, 2018. Cultivar Fuji Zehn Aztec was the last cultivar harvested in 2017 on October 2 and in 2018 on October 5. The maximum number of seeds per fruit was noticed in the cultivar Mollie's Delicious (8.34 and 8.71) during both 2017 and 2018, respectively. Cultivar Starkrimson had the fewest seeds per fruit in 2017 (7.11) and 2018 (7.42). Cultivar Baleman's Cider had the highest acidity in 2017 (0.63%) and 2018 (0.52%). In both 2017 (0.25%) and 2018 (0.23%), the Adam's Pearmain cultivar was the least acidic. Cultivar Allington Pippin (16.13 °Brix) and Red Gold (16.73 °Brix) had the highest TSS in 2017 and 2018, respectively, whereas Vance Delicious (12.30 °Brix) and Top Red (10.78 °Brix) had the lowest TSS in 2017 and 2018, respectively. The cultivars Mollie's Delicious and Red Gold had the highest total sugars (11.33 and 11.40%) in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Cultivar Baleman's Cider had the lowest total sugars (9.82%) in 2017 while Top Red (9.78%) in 2018. The cultivar Vance Delicious had the highest ratio of leaves to fruits in 2017 (55.44) and for Shalimar Apple-2 in 2018 (49.65). In 2017, cultivars Fuji Zehn Aztec (29.26) and Silver Spur (24.51), had the fewest leaves per fruit. The highest leaf chlorophyll content was recorded in cultivar Shireen (3.50 and 3.57 mg g−1 fresh weight) during the years 2017 and 2018, respectively. Cultivar Baleman's Cider had the lowest leaf chlorophyll content (2.15 mg g−1 fresh weight) during 2017, while cultivar Allington Pippin (2.09 mg g−1 fresh weight) had the lowest leaf chlorophyll content in 2018. The cultivars Fuji Zehn Aztec, with a yield efficiency of 0.78 kg/cm2 and Silver Spur with a yield efficiency of 1.14 kg/cm2 were the most yield efficient during the years 2017 and 2018, respectively. Cultivar Shalimar Apple-2 was least performing with yield efficiencies of 0.05 and 0.07 kg/cm2 during 2017 and 2018, respectively.The findings suggest that cultivar Mollie's Delicious commercially matures first and has the highest fruit length, diameter, and weight; hence, it can be a good option for cultivation so as to fetch the maximum price in the market when other cultivars are still maturing. Shalimar Apple-2 is precluded for cultivation due to least yield efficiency, whereas cultivars Fuji Zehn Aztec and Silver Spur are recommended to farmers for their higher yield efficiency.

Keywords: Malus × domestica, Kashmir, Length, Weight, Sugars, Colour, Yield

1. Introduction

Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) is a major fruit crop and is traded internationally [1]. Apple is thought to have its roots in Central Asia's Tien Shan Mountains and moved via trade routes to Asia and Europe [2]. It is a temperate region-grown deciduous fruit that is quite lucrative. With 86.44 metric tonnes of output in 2020, apples are the second-most produced fruit tree crop on this planet, after bananas (119.83 metric tonnes) [3]. Apples are a crucial part of the food and are utilized in the food industry to make drinks and other food items. Apples contain vitamins (Vitamin C) [4], organic acids (malic acid), sugars [5,6], macronutrients (Ca, Na, K, Mg, and P), trace elements (zinc, copper, manganese and iron) [7], and fibrous materials [8]. Despite the availability of more than 20 000 cultivars, only a few are currently farmed commercially across the globe [9]. The wide range of qualitative features determines variability among apple cultivars [10]. On first sight, the colour, gloss, and size of the apple are considered to determine its quality. Next, the texture, total soluble solids (TSS) content, and titrable acidity are considered to help customers identify a fruit that is higher in quality [11]. Fruit quality identification is vital since pome fruit varieties are diverse. Fruit quality encompasses a diverse range of internal and exterior characteristics which determines the food's suitability for eating. One of the important components in determining a fruit's appearance is its colour, which is a component of external fruit quality [12]. The product is first evaluated by the consumer based on its look (colour, size, and shape), followed by its eating quality, however the latter may influence the customer's decision to repurchase the item [13]. Fruit colour control has a significant impact on sales, but it is typically done visually, trusting on the correctness of a person's eyes to analyse and decide colour, however, colour is seen differently by each person. Additionally, since each individual will perceive a colour slightly differently, it is quite challenging to adequately express colour in words [14]. Cultivars had disseminated across the globe to regions with unique environments, where their inherit characteristics are not always expressed. Typically, growers choose a cultivar based on commercial rather than scientific information, causing low fruit quality that is frequently unsuitable for international markets [15]. Weather influences crop yield quantity and quality, and is thus a driving force behind farm income volatility [16]. Regardless of the maturity index used for harvest date, both acid concentration and fruit firmness decreased, while soluble-solids content increased in certain cases; all of these changes may have come from earlier flowering and greater temperatures during the maturation period [17]. While yield quantity risks and their factors are typically well documented, yield quality risks are frequently overlooked [18].

The Kashmir region comprises mainly continental temperate climate [19]. In the Kashmir region, apples have the largest acreage and yield among temperate fruits. The majority of the population in Kashmir is dependent on the apple industry for their livelihood. Most apple studies that aimed to compare physico-chemical attributes focused on a small number of apple cultivars, and probably no attempts have been made to demonstrate the major horticultural attributes of thirteen apple cultivars grown under identical orchard conditions and that too with two years of consecutive data in the Kashmir region of the northwestern Himalayas. Hence, scarce information is available on the physico-chemical characteristics of apple cultivars cultivated in Kashmir. Therefore, in 2017 and 2018, a two-year research trial was started in order to evaluate thirteen cultivars on physico-chemical parameters under the ecological conditions of the Kashmir region.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Location and plant material

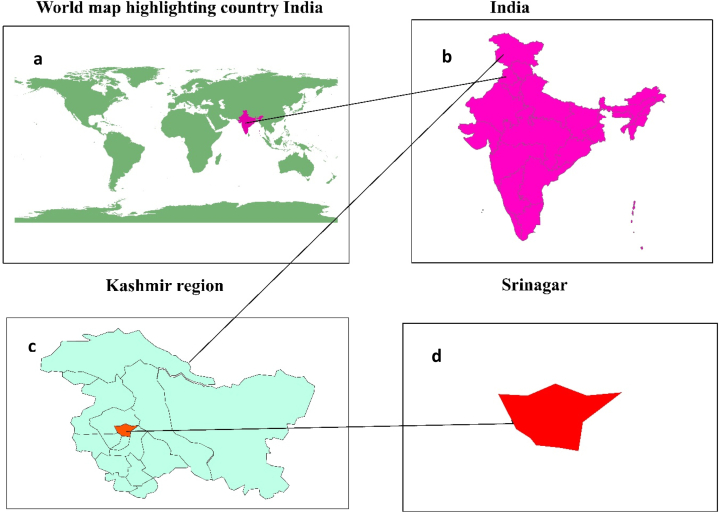

Kashmir region is located between 33° 20′ and 34° 54′ N latitude and 73° 55′ and 75° 35′ E longitude (Fig. 1), with an elevation range of 1300 to 4500 m above mean sea level, and is a biogeographic area of the North-Western Himalaya in India [[20], [21], [22]]. Thirteen apple cultivars (Fig. 2) were studied namely “Adam's Pearmain”, “Allington Pippin”, “Baleman's Cider”, “Fuji Zehn Aztec”, “Mollie's Delicious”, “Red Gold”, “Red Velox”, “Shalimar Apple-2”, “Shireen”, “Silver Spur”, “Starkrimson”, “Top Red” and “Vance Delicious” grafted on MM-106 rootstock located at the University “SKUAST-Kashmir” at the experimental field of Pomology, Srinagar, J&K, India. The trial location is situated at a latitude and longitude of 34.1467° and 74.8791°, respectively, and is 1588 m above mean sea level. The samples were taken from uniform, healthy trees and horticultural practices were performed as per university recommendations. Fruits harvested were quickly brought to the lab for examination.

Fig. 1.

Experimental field location on map (a. world map highlighting country India b. India c. Kashmir region d. Srinagar).

Fig. 2.

Thirteen Apple cultivars pictures with their names (a: Adam's Pearmain b: Allington Pippin c: Baleman's Cider d: Fuji Zehn Aztec e: Mollie's Delicious f: Red Gold g: Red Velox h: Shalimar Apple-2 i: Shireen j: Silver Spur k: Starkrimson l: Top Red m: Vance Delicious. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

2.2. Characteristics studied

2.2.1. Initial fruit set (%)

It was calculated on marked branches measuring 1 m in length with three replications (plants) for each cultivar:

| Initial fruit set (%) = [Number (No.) of fruitlets at pea stage/Number of flowers] × 100 |

2.2.2. Final fruit retention (%)

The fruits retained on earlier marked branches of 1 m length in all the cultivars (three replications each) were recorded at the time of harvesting.

| Final fruit retention (%) = [No. of fruits at harvest/No. of fruitlets at pea stage] × 100 |

2.2.3. Fruit drop (%)

By dividing the total number of fruits dropped by the total number of fruits set at the beginning, the fruit drop percentage was calculated on three replications of each cultivar.

| Fruit drop = [No. of fruitlets at pea stage - No. of fruits at harvest/No. of fruitlets at pea stage] × 100 |

2.2.4. Fruits per cluster

Fruits per cluster number of each cultivar replication was calculated at the time of harvesting on whole tree basis.

| Fruits per cluster (No.) = No. of fruits in clusters/No. of clusters |

2.2.5. Commercial maturity date

The commercial maturity date of each cultivar was determined on three replications by assessing multiple indicators like fruit size, weight, colour, seed colour turning into a dark colour and ease of separation of fruit from plant.

2.2.6. Fruit colour (h°)

The colour of fruit samples was determined using Hunter colour lab (A60-1014 593) equipment using fruits of fruit weight samples.

2.2.7. Fruit length (mm)

On each of the tree's four sides, ten fruits were collected. With the aid of a vernier calliper, the length of ten randomly chosen fruits from each replication of the cultivar was measured and expressed in millimetres (mm).

2.2.8. Fruit diameter (mm)

From each of the tree's four sides, ten fruits were collected and combined. With the aid of a vernier calliper, the diameter of ten randomly chosen fruits from each replication of the cultivar was measured and expressed in millimetres (mm).

2.2.9. Fruit weight (g)

Ten fruits each were collected from the four sides of the tree at random and mixed together. A sensitive monopan balance was used to weight each of the ten randomly chosen fruits from each replication of the cultivar and the weight was recorded in gram.

2.2.10. Fruit shape

Shape of the fruit cultivars was determined by following apple descriptor [23].

2.2.11. Fruit firmness (kg/cm2)

Ten fruits each were collected from the four sides of the tree at random and mixed together. From these randomly ten selected fruits from each replication of cultivar was used to determine fruit firmness with the use of Effegi Penetrometer (Model-Ft-3-27). At two different fruit surface, each fruit was punched after removing peel of about one square inch and firmness was recorded as kg cm−2 as an average.

2.2.12. Seeds per fruit (no.)

Ten fruits each were collected from the four sides of the tree at random and mixed together. From these ten randomly selected fruits from each replicate were cut and seeds were removed from the core. Chaffy and shriveled seeds were discarded. The number of seeds in each case were recorded and averaged per replication.

2.2.13. Leaf: fruit ratio

The total number of fruits and leaves of each cultivar replication at harvest were counted and averaged; ratio was obtained by dividing total number of leaves at harvest to the total number of fruits retained at harvest.

2.2.14. Leaf area (cm2)

Leaf samples comprising of twenty leaves per replication was collected on July 17, 2017 and 2018 at random from diverse directions of each cultivar replication and measured with the help of a leaf area meter (221 systronics) and expressed in square centimetres.

2.2.15. Leaf chlorophyll content (mg/g fresh weight)

To prevent deterioration of chlorophyll pigment, 10 representative leaf samples were taken in the morning on May 28, 2017 and 2018 [24] and immediately placed in an ice box and stored at 0 °C. Under dim lighting, leaves were washed and finely chopped, and 100 mg of chopped leaf samples were inserted in vials containing 7 ml of Dimethyl Sulphoxide (DMSO). The contents of the vials were incubated at 65 °C for 30 min, after which the extracts were transferred to graduated test tubes and the final volume was adjusted to 10 ml with DMSO as per [25]. Estimation: The aforementioned extract's optical density (OD) was measured on a Spectronic-21 at 645 nm and 663 nm against a DMSO blank, and the total chlorophyll content was computed using the following formula:

| Total chlorophyll (mg/g) = [20.2 A645 + 8.02 A663/a x 1000 × w] × V |

where,

V = Volume of the extract made

a = Length of the light path in cell (usually 1 cm)

w = Sample (g) weight

A645 = 645 nm wave length absorbance

A663 = 663 nm wave length absorbance

The values so calculated were expressed as mg/g fresh weight of leaves.

2.2.16. Yield efficiency (kg/cm2)

Yield efficiency of the tree was calculated as per [26].

| Yield efficiency = Yield (kg)/Cross sectional area (cm2) of tree trunk |

For calculating tree trunk cross sectional area (TCSA), trees girth of each cultivar replication was measured fifteen cm above graft union as per following formula.

| TCSA = (Girth)2/4π |

2.2.17. TSS (°Brix)

The total soluble solids concentration of ten fruits collected from the four sides of the tree of each tree were determined with an Erma Hand Refractometer (0–32°Brix) by putting few drops of juice (obtained by squeezing apple pulp) on the prism and then recording the reading. Calibration of refractometer with distilled water was done for precision.

2.2.18. Acidity (%)

Fruit samples (10 g) were crushed, weighed, and then added to 100 ml of distilled water before being filtered through Whatman's No. 1 filter paper to test acidity. The phenolphthalein indicator was used and 10 ml of aliquot was titrated against N/10 NaOH, and the end point was established when the solution turned pink. On the basis of 1 ml of 0.1 N NaOH solution, which is equivalent to 0.0067 of malic acid, the total titrable acidity was computed in terms of malic acid and reported in terms of percent acidity [27]. The following formula was used to compute acidity as malic acid:

| Acidity (%) = [Normality of alkali × titre value × volume made × 67/Volume of aliquot taken × weight of sample × 1000] × 100 |

2.2.19. Total sugars (%)

A 25-g sample of fruit was crushed, mixed with 250 mL of distilled water, then neutralised with 1 N sodium hydroxide to calculate the total sugar content. Two millilitres of lead acetate (at a concentration of 45%) were added to the initial volume of 250 mL. Extra lead acetate was precipitated after 5–10 min after adding 2 ml of 42% potassium oxalate, which was then filtered. Fifty millilitres of filtrate were hydrolyzed by adding 10 mL of hydrochloric acid (1:1) and letting the mixture sit at room temperature overnight. The following day, a saturated solution of NaOH was used to neutralise the excess hydrochloric acid. An aliquot of the hydrolyzed sample was transferred to a burette, and titration with a boiling solution of 5 ml of Fehling A and B, with methylene blue as an indicator, was performed [27]. Cutoff point was denoted by the development of a brick red colour.

| Total sugar (%) = [Fehling's factor × volume made up/Titre value × sample weight] × 100 |

2.2.20. Reducing sugars (%)

5 ml of Fehling's solution A and B reagent in a flask which is in boiling condition were titrated against the remaining unhydrolysed deleaded and clarified pulp solution/extract in a burette using methylene blue as an indicator to brick red end point [27].

Reducing sugar (%) = [0.05 × Stock solution/Weight of sample × solution used] × 100

2.2.21. Non-reducing sugars (%)

Non-reducing sugars were computed by removing reducing sugars from total sugars, multiplying by 0.95, and expressing as a percentage of non-reducing sugars [27].

2.2.22. Statistical analysis

Single factor analysis was performed in this experiment, which included thirteen cultivars (thirteen treatments) with three replications each (three plants) involving randomized completely block design. Utilizing statistical analysis software (R Software), data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Tukey honest multiple comparison test was used to identify differences between cultivars that were significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

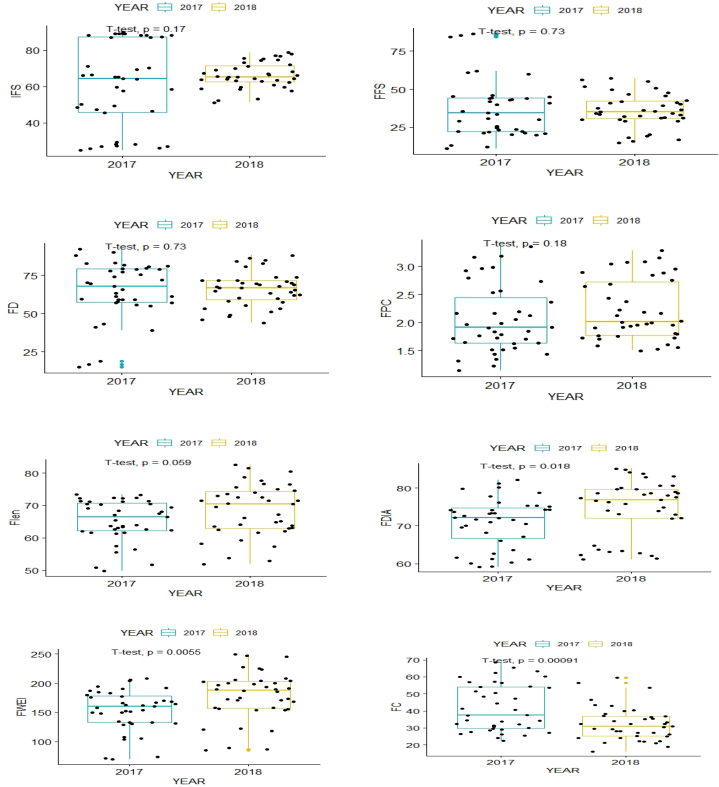

3.1. Initial fruit set

The initial fruit set varied from year to year. Significant difference in initial fruit set of cultivars during both the years was noted as is evident from Table-1 and Fig. 4. It reveals that the highest initial fruit set was in cultivar Mollie's Delicious (89.12%) during 2017, while in 2018 highest initial fruit set was in Red Gold (77.93%). Cultivar Silver Spur recorded lowest initial fruit set (25.92%) during 2017, and in 2018 Shalimar Apple-2 had lowest initial fruit set of 52.29%. The cultivars mean showed fruit set in 2017 was 60.78%, whereas in 2018 it was 66.24%.

Table 1.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on the initial fruit set, final fruit retention and fruit drop characteristics.

| C.No. | Cultivars (C) | Initial fruit set (%) |

Final fruit retention (%) |

Fruit drop (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Adam's Pearmain | 28.29 ± 0.47g | 59.83 ± 1.95i | 42.87 ± 1.06e | 30.17 ± 1.79j | 59.15 ± 1.18i | 71.85 ± 1.28c |

| 2 | Allington Pippin | 58.55 ± 0.58d | 58.62 ± 2.24i | 40.75 ± 0.56f | 33.15 ± 2.81h | 61.27 ± 1.17h | 68.87 ± 2.13e |

| 3 | Baleman's Cider | 46.48 ± 0.57f | 66.36 ± 2.63f | 60.99 ± 0.34b | 50.86 ± 1.87b | 41.03 ± 1.15l | 51.16 ± 1.76k |

| 4 | Fuji Zehn Aztec | 88.20 ± 0.58a | 75.72 ± 3.16b | 29.88 ± 0.12h | 46.72 ± 1.30c | 72.14 ± 2.87f | 55.3 ± 2.34j |

| 5 | Mollie's Delicious | 89.12 ± 1.13a | 71.03 ± 1.65d | 24.65 ± 0.09i | 15.80 ± 1.06l | 77.37 ± 1.15e | 86.22 ± 1.47a |

| 6 | Red Gold | 65.40 ± 1.41c | 77.93 ± 1.97a | 34.32 ± 1.31g | 40.07 ± 1.26e | 67.7 ± 1.91g | 61.95 ± 1.35h |

| 7 | Red Velox | 88.08 ± 1.53a | 68.09 ± 0.58e | 22.17 ± 1.18j | 36.6 ± 0.61f | 79.85 ± 1.22d | 65.42 ± 1.15g |

| 8 | Shalimar Apple-2 | 65.17 ± 1.19c | 52.29 ± 0.56j | 44.36 ± 2.87d | 35.16 ± 0.63g | 57.66 ± 1.50j | 66.86 ± 1.20f |

| 9 | Shireen | 70.29 ± 0.29b | 65.2 ± 0.57fg | 21.15 ± 1.56k | 41.75 ± 0.66d | 80.87 ± 1.60c | 60.27 ± 1.23i |

| 10 | Silver Spur | 25.92 ± 1.98h | 74.34 ± 1.24c | 85.13 ± 1.70a | 19.19 ± 0.58k | 16.89 ± 1.44m | 82.83 ± 1.24b |

| 11 | Starkrimson | 88.15 ± 1.73a | 63.9 ± 1.86gh | 44.92 ± 1.73c | 56.14 ± 2.13a | 57.1 ± 1.70k | 45.88 ± 1.28l |

| 12 | Top Red | 49.37 ± 1.25e | 64.54 ± 1.69gh | 11.97 ± 1.78l | 32.26 ± 1.15i | 90.05 ± 1.80a | 69.76 ± 1.78d |

| 13 | Vance Delicious | 27.16 ± 1.49gh | 63.25 ± 1.45h | 20.94 ± 1.21k | 30.17 ± 1.66j | 81.08 ± 1.38b | 71.85 ± 1.26c |

| Mean | 60.78 | 66.24 | 37.24 ± 1.19 | 36.00 | 64.78 | 66.02 | |

| SE(m) | ±0.07 | ±0.19 | ±0.08 | ±0.18 | ±0.01 | ±0.02 | |

Means in columns followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 based on Tukey's multiple range test.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on initial fruit set (IFS), final fruit retention (FFS), fruit drop (FD), fruits per cluster (FPC), fruit length (FLen), fruit diameter (FDIA), fruit weight (FWEI) and Fruit colour (FC). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.2. Final fruit retention

The highest final fruit retention was observed in cultivar Silver Spur and Starkrimson (85.13% and 56.14%) during the years 2017 and 2018, respectively. Cultivar Top Red (11.97%) recorded lowest final fruit retention during 2017 while Mollie's Delicious (15.80%) registered least final fruit retention in 2018 (Table-1 and Fig. 4). The overall final fruit retention mean in 2017 was 37.24%, while in 2018 it was 36.00%.

3.3. Fruit drop

Maximum fruit drop (90.05%) was noticed in cultivar Top Red during 2017, while in 2018 Mollie's Delicious (86.22%) recorded highest fruit drop. Minimum fruit drop was found in cultivar Silver Spur and Starkrimson (16.89% and 45.88%) during the years 2017 and 2018, respectively (Table-1 and Fig. 4). In 2017, the cultivars fruit drop percent was 64.78, while it was 66.02 in 2018.

3.4. Fruits per cluster

Cultivar Baleman's Cider (3.16) recorded highest number of fruits per cluster in 2017 while Fuji Zehn Aztec (3.08) had highest number of fruits per cluster in 2018. The lowest number of fruits per cluster was found in cultivar Shalimar Apple-2 (1.34 and 1.70) during both the years (Table-2 and Fig. 4). The mean number of fruits per cluster in 2017 was 2.05, whereas in 2018, 2.21 was recorded.

Table-2.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on the fruits per cluster, commercial maturity date and fruit colour characteristics.

| C.No. | Cultivars (C) | Fruits per cluster (No.) |

Commercial maturity date |

Fruit colour (h°) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Adam's Pearmain | 1.63 ± 0.15gh | 1.72 ± 0.11f | 28-Sep | 29-Sep | 65.40 ± 4.28a | 56.53 ± 1.35a |

| 2 | Allington Pippin | 2.36 ± 0.12d | 1.81 ± 0.12ef | 16-Aug | 19-Aug | 53.52 ± 5.74d | 25.08 ± 1.45i |

| 3 | Baleman's Cider | 3.16 ± 0.13a | 2.84 ± 0.27b | 30-Aug | 26-Aug | 51.39 ± 6.60e | 35.28 ± 1.95d |

| 4 | Fuji Zehn Aztec | 2.73 ± 0.14c | 3.08 ± 0.15a | 02-Oct | 05-Oct | 34.26 ± 1.76h | 24.02 ± 1.07j |

| 5 | Mollie's Delicious | 1.99 ± 0.16e | 1.93 ± 0.11de | 05-Aug | 08-Aug | 29.06 ± 1.75ij | 39.92 ± 1.22c |

| 6 | Red Gold | 2.99 ± 0.25b | 2.95 ± 0.41b | 12-Aug | 17-Aug | 30.63 ± 4.19i | 33.33 ± 3.24f |

| 7 | Red Velox | 1.71 ± 0.22g | 1.79 ± 0.12f | 10-Sep | 15-Sep | 25.47 ± 3.76k | 18.94 ± 2.56k |

| 8 | Shalimar Apple-2 | 1.34 ± 0.29j | 1.70 ± 0.13f | 19-Aug | 16-Aug | 44.28 ± 3.93f | 43.41 ± 1.56b |

| 9 | Shireen | 1.85 ± 0.30f | 2.23 ± 0.14c | 11-Sep | 15-Sep | 37.54 ± 3.34g | 33.95 ± 3.17e |

| 10 | Silver Spur | 1.96 ± 0.25ef | 2.18 ± 0.18c | 03-Sep | 03-Sep | 56.99 ± 4.09c | 25.15 ± 2.54i |

| 11 | Starkrimson | 1.92 ± 0.36ef | 2.89 ± 0.57b | 26-Aug | 27-Aug | 27.06 ± 3.67jk | 24.14 ± 2.05j |

| 12 | Top Red | 1.51 ± 0.40hi | 1.96 ± 0.43d | 07-Sep | 08-Sep | 29.40 ± 1.73i | 32.44 ± 1.73g |

| 13 | Vance Delicious | 1.43 ± 0.49ij | 1.75 ± 0.11f | 19-Sep | 11-Sep | 60.21 ± 1.74b | 29.27 ± 1.75h |

| Mean | 2.05 | 2.21 | 41.94 | 32.42 | |||

| SE(m) | ±0.02 | ±0.05 | ±0.02 | ±0.04 | |||

Means in columns followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 based on Tukey's multiple range test.

3.5. Commercial maturity date

The commercial maturity date was quite spread during both the years of study. In both the years, cultivar Mollie's Delicious was earliest harvested on August 5, 2017, while in 2018 on 8th August. Fuji Zehn Aztec was the last cultivar harvested in 2017 on 2nd October and in 2018 on 5th October (Table-2 and Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Commercial maturity time of thirteen apple cultivars.

3.6. Fruit colour

Fruit colour of cultivars under investigation differed significantly. Perusal of the Table-2 and Fig. 4 shows that the maximum hue angle was observed in cultivar Adam's Pearmain during both the years; 2017 (65.40 h°), 2018 (56.53 h°). Cultivar Red Velox recorded least hue angle (25.47 h°) during 2017 and in 2018 (18.94 h°). The mean hue angle (h°) of cultivars in 2017 was recorded 41.94 while in 2018 it was 32.42.

3.7. Fruit length

The largest fruit length (Table-3 and Fig. 4) was observed in cultivar Mollie's Delicious during 2017 (72.39 mm) and 2018 (81.45 mm). Cultivar Baleman's Cider had smallest fruit length during both the years i.e. 2017 (50.76 mm) and 2018 (52.83 mm). In the years 2017 and 2018, mean fruit length was noted 65.30 mm and 68.45 mm, respectively.

Table-3.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on the fruit length, fruit diameter and fruit weight characteristics.

| C.No. | Cultivars (C) | Fruit length (mm) |

Fruit diameter (mm) |

Fruit weight (g) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Adam's Pearmain | 56.49 ± 1.64i | 58.26 ± 1.06l | 60.29 ± 0.89k | 62.36 ± 0.48k | 105.50 ± 1.59l | 120.59 ± 1.17l |

| 2 | Allington Pippin | 62.35 ± 0.58h | 63.10 ± 2.46j | 75.12 ± 0.53c | 78.99 ± 2.06d | 130.93 ± 1.98k | 173.20 ± 1.24h |

| 3 | Baleman's Cider | 50.76 ± 1.37j | 52.83 ± 1.89m | 60.10 ± 0.98l | 62.08 ± 1.99l | 71.46 ± 1.67m | 86.94 ± 1.35m |

| 4 | Fuji Zehn Aztec | 68.08 ± 1.40d | 66.18 ± 1.34h | 78.77 ± 0.57b | 75.86 ± 0.49g | 192.39 ± 1.54b | 187.58 ± 1.18g |

| 5 | Mollie's Delicious | 72.39 ± 1.42a | 81.45 ± 2.48a | 81.18 ± 0.58a | 84.14 ± 1.66a | 205.85 ± 2.01a | 247.16 ± 1.56a |

| 6 | Red Gold | 62.62 ± 1.14g | 63.86 ± 1.77i | 71.02 ± 1.87g | 72.94 ± 1.72i | 149.87 ± 1.45i | 155.79 ± 1.62k |

| 7 | Red Velox | 62.61 ± 1.47g | 70.48 ± 0.58g | 67.12 ± 0.58i | 77.58 ± 0.61e | 132.65 ± 1.39j | 191.44 ± 1.47f |

| 8 | Shalimar Apple-2 | 63.00 ± 1.42f | 62.53 ± 0.59k | 62.63 ± 0.59j | 63.75 ± 0.65j | 152.14 ± 1.40h | 156.20 ± 1.38j |

| 9 | Shireen | 71.39 ± 1.68b | 72.48 ± 0.60e | 70.55 ± 0.62h | 73.06 ± 0.76h | 160.25 ± 1.20g | 170.79 ± 1.23i |

| 10 | Silver Spur | 71.24 ± 0.59b | 77.65 ± 1.78b | 72.64 ± 0.66f | 83.80 ± 0.73b | 184.82 ± 1.39c | 225.33 ± 1.67b |

| 11 | Starkrimson | 69.36 ± 1.05c | 71.53 ± 1.92f | 74.32 ± 0.71d | 77.32 ± 0.78f | 164.76 ± 1.37f | 202.55 ± 1.73d |

| 12 | Top Red | 72.18 ± 1.31a | 74.00 ± 3.76d | 73.16 ± 0.78e | 79.63 ± 0.77c | 177.49 ± 1.43d | 198.47 ± 1.52e |

| 13 | Vance Delicious | 66.48±1e | 75.54 ± 0.51c | 74.29 ± 1.59d | 79.66 ± 0.81c | 168.37 ± 1.28e | 206.14 ± 1.31c |

| Mean | 65.30 | 68.45 | 70.86 | 74.71 | 153.58 | 178.63 | |

| SE(m) | ±0.04 | ±0.09 | ±0.01 | ±0.02 | ±0.01 | ±0.02 | |

Means in columns followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 based on Tukey's multiple range test.

3.8. Fruit diameter

Cultivar Mollie's Delicious (Table-3 and Fig. 4) presented maximum fruit diameter (81.18 and 84.14 mm) during both the years of study (2017 and 2018). Smallest fruit diameter was observed in cultivar Baleman's Cider in the year 2017 (60.10 mm) and 2018 (62.08 mm). The mean fruit diameter was 70.86 mm in 2017, while in 2018, it was 74.71 mm.

3.9. Fruit weight

The maximum fruit weight recorded was for cultivar Mollie's Delicious (205.85 g and 247.16 g) during the two years of study (2017 and 2018). The minimum fruit weight was recorded in cultivar Baleman's Cider (71.46 g and 86.94 g) during both the years (2017 and 2018), respectively (Table-3 and Fig. 4). The mean fruit weight was lower in 2017 (153.58g) as compared to 2018 (178.63g).

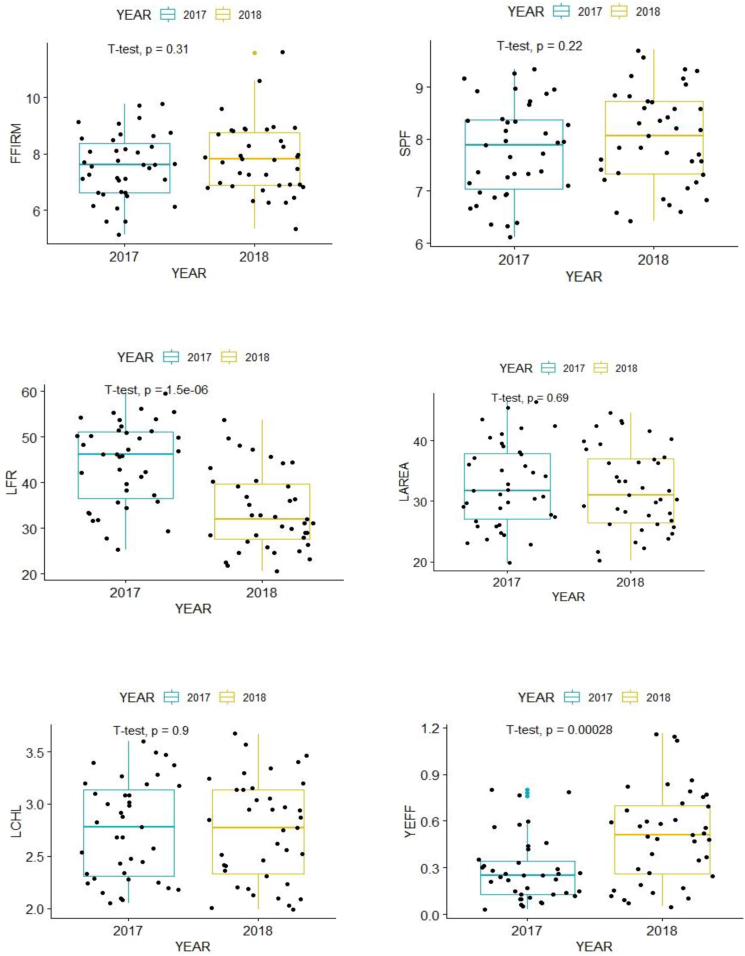

3.10. Fruit firmness

Cultivar Vance Delicious recorded highest fruit firmness (8.76 kg/cm2) during 2017, whereas Top Red (10.59 kg/cm2) registered maximum fruit firmness in 2018. The lowest fruit firmness was noticed in cultivar Allington Pippin (6.12 kg/cm2) during 2017, while Mollie's Delicious had least fruit firmness (6.33 kg/cm2) during 2018 (Table-4 and Fig. 6). The mean fruit firmness in 2017 was 7.55 kg/cm2, while in 2018 it was 7.82 kg/cm2.

Table-4.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on the fruit firmness, fruit seeds and fruit shape characteristics.

| C.No. | Cultivars (C) | Fruit firmness (kg/cm2) |

Seeds per fruit (No.) |

Fruit shape |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017/2018 | ||

| 1 | Adam's Pearmain | 8.06 ± 0.63b | 7.87 ± 0.47b | 7.33 ± 0.50e | 7.60 ± 0.51h | Conic |

| 2 | Allington Pippin | 6.12 ± 0.55f | 7.90 ± 0.51b | 8.27 ± 0.48ab | 8.58 ± 0.49b | Globose |

| 3 | Baleman's Cider | 6.60 ± 0.47e | 7.79 ± 0.63b | 7.88 ± 0.49c | 8.21 ± 0.52de | Globose |

| 4 | Fuji Zehn Aztec | 7.07 ± 0.48d | 7.26 ± 0.47d | 7.93 ± 0.47c | 8.06 ± 0.47f | Globose |

| 5 | Mollie's Delicious | 6.61 ± 0.54e | 6.33 ± 0.67e | 8.34 ± 0.55a | 8.71 ± 0.57a | Conic |

| 6 | Red Gold | 7.15 ± 0.65d | 7.45 ± 0.48cd | 7.97 ± 0.49c | 8.17 ± 0.49ef | Obloid |

| 7 | Red Velox | 7.49 ± 0.52c | 7.96 ± 0.47b | 7.39 ± 0.52e | 7.58 ± 0.53h | Globose |

| 8 | Shalimar Apple-2 | 8.70 ± 0.58a | 7.70 ± 0.49bc | 7.66 ± 0.54d | 7.84 ± 0.55g | Conic |

| 9 | Shireen | 8.26 ± 0.50b | 7.82 ± 0.51b | 7.72 ± 0.50d | 7.83 ± 0.58g | Conic |

| 10 | Silver Spur | 7.55 ± 0.51c | 7.27 ± 0.81d | 7.36 ± 0.56e | 7.73 ± 0.49g | Globose |

| 11 | Starkrimson | 7.64 ± 0.55c | 7.86 ± 0.47b | 7.11 ± 0.47f | 7.42 ± 0.59i | Cylindrical waisted |

| 12 | Top Red | 8.11 ± 0.53b | 10.59 ± 0.58a | 8.16 ± 0.48b | 8.35 ± 0.56c | Conic |

| 13 | Vance Delicious | 8.76 ± 0.58a | 7.92 ± 0.61b | 7.95 ± 0.51c | 8.31 ± 0.54cd | Cylindrical waisted |

| Mean | 7.55 | 7.82 | 7.77 | 8.03 | ||

| SE(m) | ±0.01 | ±0.01 | ±0.04 | ±0.09 | ||

Means in columns followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 based on Tukey's multiple range test.

Fig. 6.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on fruit firmness (FFIRM), seeds per fruit (SPF), leaf: fruit ratio, leaf area, leaf chlorophyll and yield efficiency.

3.11. Seeds per fruit

The maximum number of seeds per fruit (Table-4 and Fig. 6) was noticed in cultivar Mollie's Delicious (8.34 and 8.71) during both the years 2017 and 2018. Cultivar Starkrimson recorded minimum number of seeds per fruit during 2017 (7.11) and 2018 (7.42). The mean number of seeds per fruit in 2017 was 7.77, whereas it was 8.03 in 2018.

3.12. Fruit shape

The information in Table-4 pertaining to fruit shape reveals that cultivars differed and displayed various shapes as provided in descriptor UPOV, 2005. Adam's Pearmain, Mollie's Delicious, Shalimar Apple-2, Shireen and Top Red displayed conic shape while Allington Pippin, Baleman's Cider, Fuji Zehn Aztec, Red Velox and Silver Spur presented Globose shape. Starkrimson and Vance Delicious had cylindrical waisted shape. Red Gold presented obloid shape (Table-4).

3.13. Leaf: fruit ratio

The highest leaf: fruit ratio value was present in cultivar Vance Delicious during 2017 (55.44) while in 2018 was cultivar Red Velox (49.65). Least leaf: fruit ratio was noticed in cultivars Fuji Zehn Aztec (29.26) during 2017 and Silver Spur (24.51) in 2018 (Table-5 and Fig. 6). In 2017, cultivars had a leaf: fruit ratio of 44.16%, while in 2018, the leaf: fruit ratio was 33.76.

Table-5.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on the Leaf: fruit ratio, leaf area, leaf chlorophyll content and yield efficiency characteristics.

| C.No. | Cultivars (C) | Leaf: fruit ratio |

Leaf area (cm2) |

Leaf chlorophyll content (mg/g fresh weight) |

Yield efficiency (kg/cm2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Adam's Pearmain | 49.66 ± 4.71d | 43.25 ± 2.06c | 38.13 ± 4.21d | 39.93 ± 2.39bc | 2.78 ± 0.10ef | 2.85 ± 0.21d | 0.08 ± 0.01gh | 0.12 ± 0.11ij |

| 2 | Allington Pippin | 46.87 ± 1.92e | 28.90 ± 2.23h | 42.47 ± 2.34b | 40.20 ± 3.02b | 2.18 ± 0.05i | 2.09 ± 0.28f | 0.15 ± 0.04fg | 0.37 ± 0.06g |

| 3 | Baleman's Cider | 31.79 ± 4.47j | 44.18 ± 4.01b | 43.44 ± 3.68a | 41.52 ± 4.49a | 2.15 ± 0.36i | 2.10 ± 0.23f | 0.24 ± 0.01e | 0.17 ± 0.17i |

| 4 | Fuji Zehn Aztec | 29.26 ± 4.19k | 40.37 ± 4.45d | 34.13 ± 3.34e | 33.26 ± 3.78d | 2.19 ± 0.24i | 2.13 ± 0.12f | 0.78 ± 0.15a | 0.49 ± 0.06f |

| 5 | Mollie's Delicious | 38.34 ± 4.23g | 32.93 ± 5.18f | 32.83 ± 2.80f | 30.95 ± 2.88e | 3.09 ± 0.05cd | 3.04 ± 0.19cd | 0.44 ± 0.06c | 0.58 ± 0.15de |

| 6 | Red Gold | 35.63 ± 2.31i | 31.94 ± 2.10g | 28.84 ± 2.19g | 26.77 ± 2.84g | 2.92 ± 0.18de | 2.87 ± 0.21d | 0.58 ± 0.08b | 0.77 ± 0.14bc |

| 7 | Red Velox | 51.32 ± 2.34c | 26.42 ± 1.96j | 22.79 ± 1.53j | 24.58 ± 2.35h | 2.58 ± 0.20fg | 2.52 ± 0.16e | 0.13 ± 0.01gh | 0.69 ± 0.13c |

| 8 | Shalimar Apple-2 | 52.24 ± 2.37b | 49.65 ± 4.78a | 39.03 ± 1.73c | 39.44 ± 1.43c | 2.34 ± 0.06hi | 2.41 ± 0.24e | 0.05 ± 0.02h | 0.07 ± 0.15j |

| 9 | Shireen | 37.29 ± 2.48h | 35.15 ± 3.28e | 34.67 ± 1.75e | 33.26 ± 3.29d | 3.50 ± 0.07a | 3.57 ± 0.32a | 0.23 ± 0.03ef | 0.27 ± 0.16h |

| 10 | Silver Spur | 50.20 ± 4.15d | 24.51 ± 2.03k | 26.66 ± 1.77i | 25.19 ± 3.24h | 3.10 ± 0.21cd | 3.05 ± 0.09cd | 0.28 ± 0.04de | 1.14 ± 0.18a |

| 11 | Starkrimson | 49.84 ± 3.54d | 28.54 ± 2.31h | 27.44 ± 1.61h | 29.14 ± 1.75f | 3.180.15bc | 3.24 ± 0.11bc | 0.27 ± 0.05de | 0.59 ± 0.01d |

| 12 | Top Red | 46.22 ± 2.52f | 25.86 ± 2.34j | 26.07 ± 3.71i | 23.16 ± 1.73i | 2.43 ± 0.19gh | 2.46 ± 0.21e | 0.33 ± 0.02d | 0.84 ± 0.02b |

| 13 | Vance Delicious | 55.44 ± 4.15a | 27.12 ± 1.02i | 27.79 ± 4.15h | 28.75 ± 1.81f | 3.37 ± 0.23ab | 3.30 ± 0.13b | 0.12 ± 0.03gh | 0.50 ± 0.03ef |

| Mean | 44.16 | 33.76 | 32.64 | 32.01 | 2.75 | 2.74 | 0.28 | 0.51 | |

| SE(m) | ±0.02 | ±0.05 | ±0.02 | ±0.04 | ±0.02 | ±0.05 | ±0.01 | ±0.01 | |

3.14. Leaf area

It is evident from the data that the maximum leaf area was recorded in cultivar Baleman's Cider 43.44 cm2 and 41.52 cm2 during 2017 and 2018, respectively. Smallest leaf area was found in cultivar Red Velox (22.79 cm2) during 2017 and Top Red (23.16 cm2) in 2018 (Table-5 and Fig. 6). The mean leaf area (cm2) of cultivars in 2017 was recorded 32.64 while in 2018 it was 32.01.

3.15. Leaf chlorophyll content

The highest leaf chlorophyll content was recorded in cultivar Shireen (3.50 and 3.57 mg g-1 fresh weight) during the years 2017 and 2018, respectively. Cultivar Baleman's Cider had least leaf chlorophyll content (2.15 mg g−1 fresh weight) during 2017 while cultivar Allington Pippin (2.09 mg g−1 fresh weight) had lowest leaf chlorophyll content in 2018 (Table-5 and Fig. 6). The overall final leaf chlorophyll content (mg g−1 fresh weight mean) in 2017 was 2.75, while in 2018 it was 2.74.

3.16. Yield efficiency

The cultivars Fuji Zehn Aztec with yield efficiency of 0.78 kg/cm2 and Silver Spur with yield efficiency of 1.14 kg/cm2 were most yield efficient during the years 2017 and 2018, respectively. Cultivar Shalimar Apple-2 had least yield efficiency of 0.05 and 0.07 kg/cm2 during 2017 and 2018, respectively (Table-5 and Fig. 6). In 2017, cultivars had a mean yield efficiency (kg cm-2) of 0.28, while in 2018, yield efficiency was 0.51.

3.17. TSS

The highest TSS was observed in cultivar Allington Pippin (16.13 °Brix) in 2017 and Red Gold (16.73 °Brix) during 2018, whereas least TSS was noticed in cultivar Vance Delicious (12.30 °Brix) during 2017 and Top Red (10.78 °Brix) in 2018 (Table-6 and Fig. 7). During 2017 and 2018, the mean TSS (°Brix) was recorded 13.69 and 13.37, respectively.

Table-6.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on the TSS, acidity and total sugars characteristics.

| C.No. | Cultivars (C) | TSS (°Brix) |

Acidity (%) |

Total sugars (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Adam's Pearmain | 12.32 ± 0.58h | 12.78 ± 0.47g | 0.25 ± 0.06e | 0.23 ± 0.04d | 10.25 ± 0.61e | 9.93 ± 0.48f |

| 2 | Allington Pippin | 16.13 ± 0.61a | 13.85 ± 0.53c | 0.36 ± 0.08bcde | 0.40 ± 0.03ab | 9.85 ± 0.68f | 10.23 ± 0.68e |

| 3 | Baleman's Cider | 14.16 ± 0.57c | 13.98 ± 0.56b | 0.63 ± 0.09a | 0.52 ± 0.04a | 9.82 ± 0.71f | 10.33 ± 0.65e |

| 4 | Fuji Zehn Aztec | 13.18 ± 0.62e | 12.42 ± 0.60h | 0.29 ± 0.02cde | 0.27 ± 0.02cd | 10.4 ± 0.75e | 9.87 ± 0.75f |

| 5 | Mollie's Delicious | 12.93 ± 0.58f | 13.76 ± 0.47c | 0.35 ± 0.03bcde | 0.33 ± 0.03bcd | 11.33 ± 0.65a | 11.06 ± 0.71cd |

| 6 | Red Gold | 13.42 ± 0.59d | 16.73 ± 0.48a | 0.27 ± 0.01cde | 0.29 ± 0.04bcd | 11.05 ± 0.58b | 11.4 ± 0.60a |

| 7 | Red Velox | 15.95 ± 0.61b | 13.86 ± 0.47bc | 0.39 ± 0.02bc | 0.36 ± 0.03bc | 10.71 ± 0.56d | 11.17 ± 0.53c |

| 8 | Shalimar Apple-2 | 13.19 ± 0.63e | 12.34 ± 0.48h | 0.38 ± 0.03bcd | 0.40 ± 0.02ab | 10.73 ± 0.69cd | 10.91 ± 0.66d |

| 9 | Shireen | 14.23 ± 0.64c | 13.83 ± 0.60c | 0.26 ± 0.02de | 0.28 ± 0.05bcd | 11.32 ± 0.54a | 11.09 ± 0.89c |

| 10 | Silver Spur | 12.57 ± 0.82g | 13.11 ± 0.47e | 0.28 ± 0.04cde | 0.31 ± 0.04bcd | 10.97 ± 0.56b | 11.23 ± 0.79abc |

| 11 | Starkrimson | 14.15 ± 0.58c | 12.97 ± 0.58f | 0.42 ± 0.02b | 0.38 ± 0.03bc | 10.9b ± 0.72c | 11.19 ± 0.71bc |

| 12 | Top Red | 13.43 ± 0.82d | 10.78 ± 0.61i | 0.32 ± 0.03bcde | 0.35 ± 0.04bcd | 11.02 ± 0.67b | 9.78 ± 0.65f |

| 13 | Vance Delicious | 12.30 ± 0.58h | 13.36 ± 0.65d | 0.29 ± 0.02cde | 0.28 ± 0.03bcd | 11.3 ± 0.64a | 11.35 ± 0.63ab |

| Mean | 13.69 | 13.37 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 10.74 | 10.73 | |

| SE(m) | ±0.01 | ±0.02 | ±0.01 | ±0.01 | ±0.04 | ±0.09 | |

Means in columns followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 based on Tukey's multiple range test.

Fig. 7.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on TSS (TSS), acidity (ACID), total sugars (TSUG), reducing sugars and non-reducing sugars.

3.18. Acidity

The maximum acidity was recorded in cultivar Baleman's Cider (0.63 and 0.52%) during both the years (2017 and 2018), respectively. Minimum acidity was noticed in cultivar Adam's Pearmain (0.25%) during 2017 and (0.23%) in 2018 (Table-6 and Fig. 7). In 2017, cultivars had a mean acidity of 0.35%, while in 2018, the acidity was 0.34%.

3.19. Total sugars

Maximum total sugars was recorded in cultivar Mollie's Delicious and Red Gold (11.33 and 11.40%) during both the years (2017 and 2018), respectively. Least total sugars during 2017 (9.82%) was recorded in Baleman's Cider and in Top Red (9.78%) in 2018 (Table-6 and Fig. 7). The mean total sugars was 10.74% in 2017, while in 2018, it was 10.73%.

3.20. Reducing sugars

Mollies's Delicious was significantly higher in reducing sugars during 2017 (8.05%) and in 2018 was cultivar Shireen (8.01%). Least reducing sugars were found in cultivar Allington Pippin (5.32 and 5.16%) during both the years (Table-7 and Fig. 7). During 2017 and 2018, the mean reducing sugars (%) was recorded 6.79% and 6.74%, respectively (see Table 8).

Table-7.

Effect of the growing season and cultivars on the reducing sugars and non-reducing sugars characteristics.

| C.No. | Cultivars (C) | Reducing sugars (%) |

Non-reducing sugars (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Adam's Pearmain | 6.67 ± 0.27e | 6.90 ± 0.48d | 3.40 ± 0.41gh | 2.88 ± 0.37h |

| 2 | Allington Pippin | 5.32 ± 0.32h | 5.16 ± 0.91h | 4.28 ± 0.35c | 4.82 ± 0.39c |

| 3 | Baleman's Cider | 5.72 ± 0.51g | 5.63 ± 0.49f | 3.92 ± 0.33d | 4.47 ± 0.41d |

| 4 | Fuji Zehn Aztec | 6.87 ± 0.49d | 7.15 ± 0.70c | 3.35 ± 0.32hi | 2.58 ± 0.51i |

| 5 | Mollie's Delicious | 8.05 ± 0.34a | 7.91 ± 0.58a | 3.12 ± 0.38j | 2.99 ± 0.53h |

| 6 | Red Gold | 6.31 ± 0.38f | 6.07 ± 0.73e | 4.50 ± 0.31b | 5.06 ± 0.28b |

| 7 | Red Velox | 5.58 ± 0.65g | 5.38 ± 0.65g | 4.87 ± 0.28a | 5.50 ± 0.42a |

| 8 | Shalimar Apple-2 | 6.89 ± 0.43d | 6.76 ± 0.47d | 3.65 ± 0.41ef | 3.94 ± 0.46f |

| 9 | Shireen | 7.93 ± 0.33a | 8.01 ± 0.49a | 3.22 ± 0.29ij | 2.93 ± 0.47h |

| 10 | Silver Spur | 7.03 ± 0.34d | 6.92 ± 0.50d | 3.74 ± 0.37e | 4.09 ± 0.34ef |

| 11 | Starkrimson | 6.88 ± 0.38d | 6.75 ± 0.54d | 3.82 ± 0.40de | 4.22 ± 0.38e |

| 12 | Top Red | 7.28 ± 0.40c | 7.49 ± 0.58b | 3.55 ± 0.43fg | 2.18 ± 0.46j |

| 13 | Vance Delicious | 7.69 ± 0.81b | 7.43 ± 0.60b | 3.43 ± 0.51gh | 3.72 ± 0.39g |

| Mean | 6.79 | 6.74 | 3.76 | 3.80 | |

| SE(m) | ±0.01 | ±0.02 | ±0.02 | ±0.05 | |

Means in columns followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 based on Tukey's multiple range test.

Table-8.

Climatic data of two years (2017 and 2018) at the experimental site.

| Month | Year |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 |

2018 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

| Temperature (oC) | ||||

| Maximum | Minimum | |||

| January | 3.94 | 10.73 | −2.44 | −4.87 |

| February | 10.61 | 12.3 | 0.10 | −0.91 |

| March | 14.82 | 18.45 | 3.12 | 3.32 |

| April | 19.90 | 21.41 | 6.54 | 6.82 |

| May | 25.35 | 24.65 | 10.16 | 9.00 |

| June | 26.82 | 28.33 | 13.19 | 13.45 |

| July | 30.24 | 28.84 | 17.54 | 17.16 |

| August | 30.05 | 30.74 | 15.85 | 16.58 |

| September | 28.60 | 27.98 | 10.97 | 11.93 |

| October | 25.35 | 21.74 | 3.55 | 2.89 |

| November | 16.08 | 12.07 | −0.78 | 0.22 |

| December | 10.18 | 9.37 | −2.68 | −4.56 |

3.21. Non-reducing sugars

Maximum non-reducing sugars were found in cultivar Red Velox (4.87 and 5.50%) during both the years of study i.e. 2017 and 2018, respectively. Minimum non-reducing sugars were noticed in cultivars Mollie's Delicious (3.12%) during 2017 and Top Red (2.18%) in 2018 (Table 7 and Fig. 7). The mean non-reducing sugars (%) in 2017 was 3.76, whereas it was 3.80 in 2018.

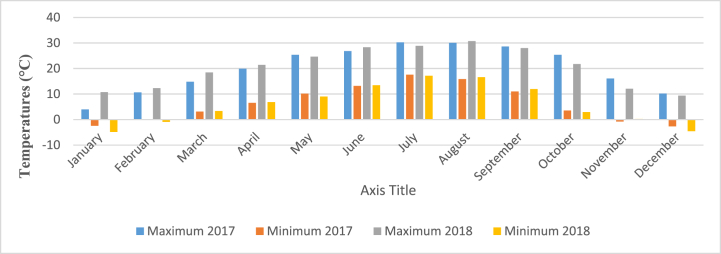

4. Discussion

The present investigation reflects significant differences for initial fruit set, fruit drop and final fruit retention. The variations in initial fruit set and final fruit retention amid dissimilar cultivars may be because of their genomic differences and year to year variation might be due to environmental effect. Further, partial or lack of bloom synchronisation with compatible cultivar may be another reason for variation in initial fruit set among cultivars. The initial fruit set under open pollination is also influenced by the closeness from the compatible pollen source. In temperate fruits, fruit set depends on the prevailing weather during blooming and the environment after fruit set. According to Ref. [28] pollination is essential for fruit formation. Pollen germination is very temperature sensitive. Cross-pollination is the most common method of apple pollination; however, certain varieties have been observed to be self-pollinating [29]. claimed that the impact of the previous temperature has a substantial influence in the June apple drop. High temperature during fruit growth period results in more transpiration (water loss) from leaves and fruits, and consequently such fruits are unable to withstand the moisture stress and are then shed easily. According to Ref. [30] when fruit set was plentiful, apple fruit with fewer than 3 seeds were shed first. Fruit species (apple, pear, and quince) that produce fruits preferentially drop fruits with fewer seeds. Such fruits are really more vulnerable to environmental challenges, such as water stress, nutritional inadequacy, and so on, and are thus more likely to fruit drop [31]. Therefore, the larger seed content of the fruit is the most crucial need for it to remain on the tree. Fruit drop on fruit trees at key growth phases is a problem for growers. According to Ref. [32] fruit drop severity is specific to cultivar. Apple production is challenged by pre-harvest fruit drop, which occurs when fruit falls off the tree before it reaches horticultural maturity. By the start of harvest, yield losses of up to thirty percent are typical, and they get worse with any harvest delay, depending on the growing season and cultivar. Developmental and environmental cues have an impact on this apple fruit's abscission. Cellulase and polygalacturonase enzymes are involved in degradation of cell wall when metabolic changes are detected. While other plant hormones may also play a role in abscission promotion, however ethylene has proven to be affecting this phenomenon. Fruit drop varies between orchards under varying meteorological and agrological circumstances throughout the same year, and it also varies between years within orchard [33,34]. Temperature, wind, nutrition, sunshine, water and disease pressure are all variables that differ across years and locales. When resources are limited, growth and development of the plant changes so as to adapt to prevailing conditions [35]. As a result, these variables may cause early abscission in reaction to stress [36,37]. The variation in fruits per cluster among cultivars may be an inherent character and also effected by environmental factors. The exact mechanism causing the year-to-year variance is yet unclear. The number of fruits per cluster at harvest were 1.06–1.49 despite applying flower removing techniques in Apple cultivar Golden Delicious [38]. Cultivar characteristic may be the reason for the variation of commercial maturity dates among cultivars. The fruit maturity time is specific to cultivar in particular agro-climatic conditions with a minor shift depending on climatic conditions. These findings are corroborated by Ref. [39] conclusions that harvest timing is affected by location, cultivar, rootstock, year and ecological factors. The variation in commercial maturity dates may also be due to difference in bloom dates, prevailing temperature (Fig. 3), sunshine durations, overcast days and rainfall conditions during fruit growth period. Apple maturity also gets delayed if cooler temperature prevails during summer. Variation in maturity enables the grower to select plant cultivars for increasing the varietal spectrum, spreading harvest time to avoid glut in the market in order to fetch remunerative price of the produce. Fruit weight showed huge variation among cultivars. The heaviest fruits were observed in cultivar Mollie's Delicious while lightest fruits in Baleman's Cider. Larger fruit weight in case of Mollie's Delicious can be explained from the related fact that the fruits of this cultivar were significantly longer and had significantly larger diameter than other cultivars, as such had heavier fruits. In case of Baleman's Cider with lowest fruit weight, the data shows that the fruit diameter in this case was significantly smaller than all other cultivars and fruit length lower than the mean fruit length of cultivars. Thus it can be said that fruit length and diameter influence the fruit weight. The differential behavior of cultivars to fruit length, diameter and weight can be attributed to the fact that fruit size is typical to each cultivar and is a varietal characteristic. Variations in fruit size may also be induced by environmental factors, crop load, vigour of the tree and difference in both number and size of cells. Our findings are in consonance with [40] who stated that the genotypes of apple showed a range of fruit length 38.29–81.42 (mm), 46.00–94.99 (mm) for fruit diameter and 43.04–310.99g for fruit weight. Similar studies reported that fruit diameters varied significantly among apple genotypes [[41], [42], [43], [44], [45]]. Fruit firmness affects the quality of fruit and storability of a cultivar. Fruit firmness (textural property) is mostly employed at the marketable level to identify the ideal harvesting period; it is a damaging measurement and used in combination with other metrics to define the stage of ripeness [46,47]. The variation in fruit firmness among cultivars is an inherent feature as reported by Ref. [48]. Our results are in agreement with [40] who reported fruit firmness among apple genotypes ranged from 3.99 to 14.05 kg/cm2. Further our findings are also supported by the results of [49] who observed that fruit firmness varied among cultivars and reported that in Well Spur, Silver Spur, Oregon Spur and Vance Delicious it ranged from 7.5 to 9.6 kg/cm2. Further, supported by Ref. [50] who studied fifteen cultivars and found firmness ranging from 5.53 to 10.30 kg/cm2. Colour is one of the most important characters in organoleptic rating of a fruit. It is the visible colour of the fruit that attracts or repels a consumer in the first instance, though colour preference may differ among consumers. The apple skin colour plays a profound role in determining maturity and identification as well as consumer demand because customers tend to prefer mostly red coloured apples while some people are having a liking for green apples. Fruit skin colour is determined by carotenoids, chlorophyll and anthocyanin present in the skin [51]. Cultivar Adam's Pearmain recorded poor fruit colour due to highest hue angle whereas best fruit colour was noted in cultivar Red Velox due to lowest hue angle during both years. Lower the value of hue angle corresponds to better red colour and vice versa. The variation in fruit colour of cultivars is mainly a varietal characteristic and also influenced by weather conditions, leaf to fruit ratio, altitude and management practices to some extent. Thus, there can be some variation in fruit colour in a cultivar from year to year and place to place. Our findings are in agreement with [52] who reported fruit colour variation among apple cultivars: Gala Red Lum, Super Chief Sandidge, and Golden Clone B at maturity and found their fruit colour (hue angle) of 34.86 h°, 29.16 h° and 79.46 h°, respectively. Consumers may often identify specific fruit cultivars by their shape [10]. Fruit shape showed wide variation with highest frequency for conic (38.46%) and globose (38.46%) followed by cylindrical waisted (15.38%) and obloid (7.69%). The variances in fruit shape among cultivars may be due to their genetic makeup. Round, conical, and oblate fruit shapes were prevalent in twenty two genotypes of apple [53]. Among fifteen apple varieties, apple fruit form ranged from conical to globose to oblate to cylindrical waisted [50]. Apple form and weight are influenced by the quantity and dispersion of seeds inside the fruit [54]. Variation in seed number per fruit among cultivars may be both due to genetic differences and pollination factors. The effect of seeds on fruit growth is obvious in fruits with a very uneven shape associated with the presence of seeds in locules on one side of the fruit [55]. Our results are supported by Ref. [56] who stated that the seeds number per fruit varied from 6.50 in Galaxy Gala to 9.3 in Granny Smith. Auxin, cytokinine, and gibberellic acid are abundantly generated in the seed and consequently has a good impact on fruit growth by boosting cell quantity and expansion. Additionally, these hormones are reported to facilitate the transfer of plant nutrients into fruit [10]. The cultivars under trial exhibited significant variations for leaf: fruit ratio, leaf area, leaf chlorophyll content and yield efficiency traits. Leaf: fruit ratio is the average number of leaves per fruit in a plant. According to Ref. [57] most apple cultivars require 30 to 40 leaves per fruit for the formation of a high quality fruit. Variation obtained among cultivars for leaf: fruit ratio may be due to factors such as genetic, environmental adaptability, alternate bearing tendency etc. and their interaction with each other. Differences noticed in leaf area among cultivars may be due to genetic makeup of cultivars, environmental effect, biotic and abiotic factors around cultivars. Chlorophyll is the pigment that gives leaves their characteristic green colour, and the amount of chlorophyll per unit area is a measure of a plant's photosynthetic ability [58]. The variations in the chlorophyll concentration of the cultivars are in agreement with the findings of [59], who discovered that cultivar Starkspur Golden Delicious had higher leaf chlorophyll contents all season long than conventional Golden Delicious cultivar. The variation obtained among cultivars in leaf chlorophyll content may be due to their genetic character as well as biotic and abiotic factors influencing this trait. The yield efficiency of a tree is an essential indicator of its production [60]. Higher the yield efficiency of a cultivar better will be its production, productivity and profit. The variation obtained among cultivars in yield efficiency may be due to factors such as genetic, bearing habit, spur density, pollination, alternate bearing, hormonal fluctuations, environmental adaptability etc. and their interaction with each other. Fruit biochemical characteristics varied significantly among cultivars. The components of total soluble solids (TSS) are organic acids, sugars, and inorganic salts [46,61]. According to Ref. [47] a sensory panel's perception of sweetness was best predicted by the amount of total soluble solids present. For a fruit to be accepted by consumers, internal qualities like sweetness are crucial. Since evaluating sweetness through the senses is not always easy, the total sugar content can be measured to evaluate it [47,62]. Apples contain soluble sugars, and organic acids, both of which affect apples tastes. Sucrose, glucose and fructose were the main soluble sugars and main sugar alcohol was sorbitol in the mature Starkrimson apples [63]. Reducing sugars are those that have free aldehyde or ketone groups. e.g. glucose, fructose, lactose etc. Reducing sugars consists monosaccharides. The sugar is non-reducing when two or more monosaccharides are joined by their aldehyde or ketone groups, preventing these reducing groups from being free. An example of this is sucrose [64]. The cultivars under study exhibited significant differences in fruit chemical characteristics. Our outcomes are in concurrence with results of [65] who stated that TSS content in apple germplasm varied from 12.55 to 19.24 °Brix. Our findings for total sugars are in range with findings of [66] who reported that total sugars among cultivars varied from 9.76% in Braeburn to 14.50% in Gala Must. Our results for reducing sugars are in tune to findings of [67] who reported variation in reducing sugars among cultivars which varied between 6.28% in Starkrimson to 8.81% in Early Red One. Our results for non-reducing sugars are in close range with [68] who stated that non-reducing sugars ranged from 2.74% in Granny Smith to 3.71% in Gibson Golden among cultivars studied. According to Ref. [69], apple cultivars sugar content can vary from orchard to orchard, year by year and between harvesting dates. As a result, a minimal to maximal range values can be a guide, but there is no single value that can be used to distinguish each cultivar. The sensory strength of the total organic acid content (tartaric acid, malic acid and citric acid) is the fundamental fruit quality characteristic known as acidity (or sourness) [70]. Organic acids give apples their distinctively sour flavour, influencing how sweet things are perceived as well as the intensity of the flavor [46,71]. Cultivar Starkrimson; main organic acid was malic acid and other organic acids were oxalic acid, succinic acid, acetic acid and citric acid were in minor amounts [62]. Our outcomes are in accordance with [64] who reported titratable acidity in apple germplasm to range between 0.10% and 0.82%. Apple taste is primarily related to the amount of sugar and acid in the fruit tissues and the balance between these. There is no single desirable level of sugar, acid, or sugar/acid ratio that applies to all cultivars [55]. Fruit requires sugars to make it edible, but it also needs acids to improve the flavour and keep the sugars from tasting sickly or insipid [72]. Further, balance of TSS and acid has important role in consumer acceptance and contributes towards giving many fruits their characteristic taste. The genetic variations across apple cultivars may account for the noticeable variations in TSS, total sugars, acidity, reducing and non-reducing sugars. These genetic variations then influence the synthesis of photosynthates and their subsequent breakdown into simple metabolites. Our findings of fruit chemical characteristics are within the range. These chemical parameters may vary from region to region, year to year due to climate, weather, soil and management factors.

Fig. 3.

Surface air maximum and minimum temperatures (°C) during 2017 and 2018 at trial.

5. Conclusion

This investigation was the first effort to explore the physico-chemical attributes of thirteen apple cultivars during two consecutive years in the Kashmir region of Indian Himalaya. The results in this study demonstrate the significant effect that cultivars and year can have on the physico-chemical attributes on apples. Microclimates as well as management practices have a profound effect on fruit physico-chemical qualities. The research data generated can be applicable to any part of world having similar agro-climatic conditions. The knowledge produced here would serve an important document for scientists, farmers and all stakeholders. The apple cultivars inspected in this study have a wide fruit characteristics diversity and, therefore can be used in breeding purpose for developing new cultivars. Further, farmers gets wide choice of selection of cultivars for apple fruit production.

Funding

This research was funded by King Saud University Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R19), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors also extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R24), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Contributor Information

Mohammed Tauseef Ali, Email: tauseefwani500@gmail.com.

Zahoor Ahmad Shah, Email: zahoor37@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Wiehle M., Nawaz M.A., Dahlem R., Alam I., Khan A.A., Gailing O., Mueller M., Buerkert A. Pheno-genetic studies of apple varieties in northern Pakistan: a hidden pool of diversity. Sci. Hortic. 2021;281 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornille A., Feurtey A., G′elin U., Ropars J., Misvanderbrugge K., Gladieux P., Giraud T. Anthropogenic and natural drivers of gene flow in a temperate wild fruit tree: a basis for conservation and breeding programs in apples. Evol. Appl. 2014;8(4):373–384. doi: 10.1111/eva.12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FAO Food and Agriculture data. http://www.fao.org/faostat

- 4.Ferretti G., Turco I., Bacchetti T. Apple as a source of dietary phytonutrients: Bioavailability and evidence of protective effects against human cardiovascular disease. Food Nutr. Sci. 2014;5:1234–1246. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berni R., Cantini C., Guarnieri M., Nepi M., Hausman J.F., Guerriero G., Romi M., Cai G. Nutraceutical characteristics of ancient Malus domestica Borkh. fruits recovered across Siena in Tuscany. Medicines. 2019;6:27. doi: 10.3390/medicines6010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oszmianski J., Lachowicz S., Gamsjäger H. Phytochemical analysis by liquid chromatography of ten old apple varieties grown in Austria and their antioxidative activity. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019;246:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nour V., Trandafir I., Ionica M.E. Compositional characteristics of fruits of several apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) cultivars. Not. Bot. Hort. Agrobot. 2010;38:228–233. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morresi C., Cianfruglia L., Armeni T., Mancini F., Tenore G.C., D'Urso E., Micheletti A., Ferretti G., Bacchetti T. Polyphenolic compounds and nutraceutical properties of old and new apple cultivars. J. Food Biochem. 2018;42 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juniper B.E., Mabberley D.J. Timber Press; Portland, OR: London: 2006. The Story of the Apple. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musacchi S., Serra S. Apple fruit quality: Overview on pre-harvest factors. Sci. Hortic. 2018;234:409–430. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drogoudi P.D., Michailidis Z., Pantelidis G. Peel and flesh antioxidant content and harvest quality characteristics of seven apple cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2008;115:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2007.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oluwole O.O., Olajide I.F. Effect of pre-storage hot air and hot water treatments on post-harvest quality of mango (Mangifera indica Linn.) fruit. Not. Sci. Biol. 2020;12:634. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanoli M., Buccheri M. Overview of the methods for assessing harvest maturity. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2012;8:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobrzañski B., Rybczyñski R. Colour change of apple as a result of storage, shelf- life, and bruising. Int. Agrophysics. 2002;16:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuri J.A., Moggia C., Sepulveda A., Poblete-Echeverría C., Valdés-Gómez H., Torres C.A. Effect of cultivar, rootstock, and growing conditions on fruit maturity and postharvest quality as part of a six-year apple trial in Chile. Sci. Hortic. 2019;253:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesk C., Rowhani P., Ramankutty N. Infuence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature. 2016;529(7584):84. doi: 10.1038/nature16467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiura T., Ogawa H., Fukuda N., Moriguchi T. Changes in the taste and textural attributes of apples in response to climate change. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2418. doi: 10.1038/srep02418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalhaus T., Schlenker W., Blanke M.M., Bravin E., Finger R. The effects of extreme Weather on apple quality. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:7919. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64806-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dad J.M., Muslim M., Rashid I., Reshi Z.A. Time series analysis of climate variability and trends in Kashmir Himalaya. Ecol. Ind. 2021;126 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodgers W.A., Panwar H.S. Wildlife Institute of India; Dehradun: 1988. Biogeographical Classification of India; pp. 120–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik M.I. Spatio-temporal analysis of urban dynamics in Kashmir valley (1901- 2011) using geographical information system. J. Int. Multidiscip. Res. 2012;2(8):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulzar R., Khuroo A.A., Rather Z.A., Ahmad R., Rashid I. Symphyotrichumsubulatum (Michx.) GL Nesom (Asteraceae): a new distribution record of an alien plant species in Kashmir Himalaya. India. Check List. 2021;17:569. [Google Scholar]

- 23.UPOV . International Union for the protection of new varieties of plants; Geneva: 2005. Apple Descriptor. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halfacre R.G., Bradent J.A., Rollens H.A. Effect of alar on morphology, chlorophyll contents and net CO2 assimilation rate of young apple trees. Proc. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1968;98:40–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiscox J.D., Israelstam G.F. A method for the extraction of chlorophyll content from leaf tissue without maceration. Can. J. Bot. 1979;57:1332–1334. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westwood M.N. third ed. Timber Press; Portland Oregon: 1993. Temperate Zone Pomology: Physiology and Culture. [Google Scholar]

- 27.A.O.A.C . fourteenth ed. Association of Official Agriculture Chemists; Washington, D.C, USA: 1990. Methods of Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramírez F., Davenport T.L. Apple pollination: a review. Sci. Hortic. 2013;162:188–203. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racsko J., Leite G.B., Petri J.L., Zhongfu S., Wang Y., Szabo Z., Soltesz M., Nyeki J. Fruit drop: the role of inner agents and environmental factors in the drop of flowers and fruits. International Journal of Horticultural Science. 2007;13(3):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teskey J.E., Shoemaker J.S. The AVI Publishing Company Connecticut Westport; 1972. Tree Fruit Production; pp. 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stosser R. In: Lucas Anleitung Zum Obstbau. Link H., editor. Eugen Ulmer GmbH Co.; Stuttgart: 2002. Von der Blute zur Frucht; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arseneault M.H., Cline J.A. A review of apple pre-harvest fruit drop and practices for horticultural management. Sci. Hortic. 2016;211:40–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basak A., Buczek M. The effectiveness of 3, 5, 6-TPA used against pre-harvest fruit drop in apple. Proc. XIth IS Plant Bioregulators Fruit Prod. Acta Hortic. 2010;884:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson T., Lopez S. Chemical thinning and summer PGRs for consistent return cropping of ‘Honeycrisp’ apples. Proc. XIth IS Plant Bioregulators Fruit Prod. Acta Hortic. 2010;884:635–642. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baena-Gonzalez E., Sheen J. Convergent energy and stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts J.A., Elliott K.A., Gonzalez-Carranza Z.H. Abscission, dehiscence, and other cell separation processes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002;53:131–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.092701.180236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor J.E., Whitelaw C.A. Signals in abscission. New Phytol. 2001;151:323–339. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miranda C., Santesteban L.G., Royo J.B. Removal of the most developed flowers influences fruit set, quality and yield of apple clusters. Hortscience. 2005;40(2):353–356. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karacali I. Ege Univ. Fac. of Agri., Pub. No: 494, Izmir; 2004. Storage and Marketing of Horticultural Crops; p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaya T., Balta F., Sensoy S. Fruit quality parameters and molecular analysis of apple germplasm resources from Van Lake Basin, Turkey. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2015;39:864–875. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bongers A.J., Risse L.A., Bas V.G. Physical and chemical characteristics of apples in European markets. HortTechnology. 1994;4:290–294. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hampson C.R., McNew R., Azarenko A., Berkett L., Barritt B., Belding R., Brown S., Cilements J., Ciline J., Cowgill W. Performance of apple cultivars in the 1995 ne-183 regional project planting: II Fruit quality characteristics. J. Am. Pomol. Soc. 2004;58:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller S., McNew R., Belding R., Berkett L., Brown S., Clements J., Cline J., Cowgill W., Crassweller R., Garcia E., Greene D., Greene G., Hampson C., Merwin I., Moran R., Roper T., Schupp J., Stover E. Performance of apple cultivars in the 1995 NE- 183 regional project planting: II. Fruit quality characteristics. J. Am. Pomol. Soc. 2004;58(2):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozrenk K., Gundogdu M., Kaya T., Kan T. Pomological features of local apple varieties cultivated in the region of Çatak (Van) and Tatvan (Bitlis) Yuzuncu Yil University Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2010;21:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karadeniz T., Akdemir E.T., Yilmaz I., Aydin H. Clonal selection of Piraziz apple. Akademik Ziraat Dergisi. 2013;2:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kingston C.M. Maturity indices for apple and pear. Hortic. Rev. 1992;13(32):407–432. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harker F.R., Marsh K.B., Young H., Murray S.H., Gunson F.A., Walker S.B. Sensory interpretation of instrumental measurements 2: sweet and acid taste of apple fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2002;24(3):241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magness J.R., Diehl H.C., Haller M.H. U.S.D.A. Bulletin; 1926. Picking Maturity of Apple in Relation to Storage; p. 1448. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chauhan J.S., Sharma L.K. Productivity and fruit quality of some spur type apple cultivars under a high density system. Acta Hortic. 2008;772:195–198. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma D.P., Sharma H.R., Sharma N. Evaluation of apple cultivars under sub- temperate mid hill conditions of Himachal Pradesh. Indian J. Hort. 2017;74(2):162–167. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lancaster J.E. Regulation of skin colour in apples. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1992;10:487–502. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kosser R. Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir; Shalimar: 2017. Response of Apple Varieties to Chemical Thinning in High Density Orchards. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gecer M.K., Ozkan G., Sagbas H.I., Ilhan G., Gundogdu M., Ercisli S. Some important horticultural properties of summer apple genotypes from Coruh valley in Turkey. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020;20(53):51406–51416. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keulemans J., Brusselle A., Eyssen R., Vercammen J., Daele G. Fruit weight in apple as influenced by seed number and pollenizer. Acta Hortic. 1996;423:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson J.E. Biology of Apples and Pears (Author J.E. Jackson) Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. Flowers and fruits; pp. 268–325. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bozbuga F., Pirlak L. Determination of phenological and pomological characteristics of some apple cultivars in Nigde-Turkey ecological conditions. The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences. 2012;22(1):183–187. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haffman M.B., Baynton Cultural practices in breeding apple orchards. Cornell Extension Bulletin. 1950;789:11. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palta J.P. Leaf chlorophyll content. Rem. Sens. Rev. 1990;5(1):207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cardini F. Conclusive data on the seasonal content of chlorophyll in the leaves of the apple cultivar Golden Delicious and its mutant Starkspur Golden Delicious. Rivista della Ortofloro frutti coltura Italiana. 1980;64(3):191–212. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kiprijanovski M., Ristevski B., Arsov T., Gjanovski V. Influence of planting distance to the vegetative growth and bearing of apple cultivar ‘Jonagold’ on rootstock MM106. Acta Hortic. 2009;825:453–458. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bartolozzi F., Bertazza G., Bassi D., Cristoferi G. Simultaneous determination of soluble sugars and organic acids as their trimethylsilyl derivatives in apricot fruits by gas- liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography. 1997;758(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)00709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osorio S., Fernie A.R. In: Fruit Ripening: Physiology, Signalling and Genomics. Nath P., Bouzayen M., Mattoo A.K., Pech J.C., editors. CABI; 2014. Fruit ripening: Primary metabolism; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y., Chen N., Ma Z., Che F., Mao J., Chen B. The changes in color, soluble sugars, organic acids, anthocyanins and aroma components in “Starkrimson” during the ripening period in China. Molecules. 2016;21:1–13. doi: 10.3390/molecules21060812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Potter N.N., Hotchkiss J.H. Food Science. Chapman and Hall, Inc.; New York: 2006. Constituents of foods: properties and significance; pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mratinic E., Aksic M.F. Evaluation of phenotypic diversity of apple germplasm through the principle component analysis. Genetika. 2012;43(2):331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pandit B.A. Ph.D thesis submitted to Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir; Shalimar: 2014. Pollen Compatibility Studies of Some Exotic Apple Cultivars. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shah I.S. Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir; Shalimar: 2018. Study on Performance of Exotic Cultivars of Apple (Malus × Domestica Borkh.) on Clonal Rootstock (MM-106) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verma P., Thakur B.S., Chauhan N. Performance of some Apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) cultivars for fruit quality traits under mid hill conditions of Himachal Pradesh, India. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2018;7(1):788–793. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iwanami H. In: Breeding for Fruit Quality M.A. Jenks. Bebeli P.J., editor. John Willey and Sons, Inc.; 2011. Breeding for fruit quality in apple; pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kader A.A. Flavor quality of fruits and vegetables. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008;88(11):1863–1868. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quilot-Turion B., Causse M. In: Fruit Ripening: Physiology, Signalling and Genomics. Nath P., Bouzayen M., Mattoo A.K., Pech J.C., editors. CABI; 2014. Natural diversity and genetic control of fruit sensory quality; pp. 228–246. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Janick J., Cummins J.N., Brown S.K., Hemmat M. In: Fruit Breeding, Volume I: Tree and Tropical Fruits. Janick J., Moore J.N., editors. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1996. Apples; pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]