Abstract

Background:

As medical and public health professional organizations call on researchers and policy makers to address structural racism in health care, guidance on evidence-based interventions to enhance health care equity is needed. The most promising organizational change interventions to reduce racial health disparities use multilevel approaches and are tailored to specific settings. This study examines the Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity (ACCURE) intervention, which changed systems of care at two U.S. cancer centers and eliminated the Black-White racial disparity in treatment completion among patients with early-stage breast and lung cancer.

Purpose:

We aimed to document key characteristics of ACCURE to facilitate translation of the intervention in other care settings.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with participants who were involved in the design and implementation of ACCURE and analyzed their responses to identify the intervention’s mechanisms of change and key components.

Results:

Study participants (n = 18) described transparency and accountability as mechanisms of change that were operationalized through ACCURE’s key components. Intervention components were designed to enhance either institutional transparency (e.g., a data system that facilitated real-time reporting of quality metrics disaggregated by patient race) or accountability of the care system to community values and patient needs for minimally biased, tailored communication and support (e.g., nurse navigators with training in antiracism and proactive care protocols).

Conclusions:

The antiracism principles transparency and accountability may be effective change mechanisms in equity-focused health services interventions. The model presented in this study can guide future research aiming to adapt ACCURE and evaluate the intervention’s implementation and effectiveness in new settings and patient populations.

Keywords: Cancer care, Quality improvement, Intervention, Planned adaptation, Community-based participatory research, Antiracism

1. Introduction

Since publication of the 2002 Institute of Medicine report titled “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care,” (Nelson et al., 2002) evidence of racial disparities in health outcomes has steadily accumulated and remains relevant in every category of illness. In the case of cancer, one of the leading causes of mortality in the U.S., death rates are higher among Black Americans than any other racial or ethnic group for most cancers (DeSantis et al., 2019). Over the last two decades, public health researchers and advocates have examined the role of racism as a social determinant of health and a driving factor in race-based health disparities (Came & Griffith, 2018; Jones, 2002, pp. 7–22; Largent, 2018). Experts define racism as a hierarchical social system in which the dominant group uses social power to systematically advantage racial in-group members and simultaneously oppress group members defined as inferior (Bailey et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2019). Institutional racism is the manifestation of a race-based system of advantage and disadvantage in the policies and practices of institutions (Bassett & Graves, 2018). Scholars have highlighted ways in which historical policies that exemplify institutional racism, such as hospital segregation, continue to have implications for the unequal treatment of people of color today (Bailey et al., 2017; Largent, 2018). Acknowledging systemic aspects of racism that are embedded in the social environment and institutional cultures, researchers have called for public health strategies that promote organizational change in order to create more equitable care outcomes (Bailey et al., 2021; Bassett & Graves, 2018; Griffith, 2010).

Despite the growing literature on the need for institutional change to address racial disparities in health care, research on interventions aimed at reducing cancer disparities remains primarily focused on changing patient knowledge and behavior, as opposed to examining health care systems where patients receive care (Hardeman, 2020). A recent policy statement from the American Society of Clinical Oncology called on researchers to advance health equity by implementing evidence-based interventions that address structural barriers to accessing quality care (Patel et al., 2020). Health care settings can be observed and modified, and intervening at the organizational level, both within care systems and across systems and institutions, is an underutilized approach to address disparities in outcomes (Bassett & Graves, 2018; Griffith, Yonas, Mason, & Havens, 2010). By targeting systems of care, quality improvement interventions have the potential to address an underlying cause of racial disparities: institutional racism. In doing so, system-focused interventions are likely to be more sustainable and reach more patients than interventions targeting individuals.

The most promising organizational change interventions to reduce racial health disparities use multilevel approaches and are tailored to the specific context (Chin et al., 2012; Hassen et al., 2021). The Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity (ACCURE) intervention, the parent trial for this study, was a multicomponent intervention that successfully eliminated the racial disparity in treatment completion rates between Black and White early-stage breast and lung cancer patients. The intervention took place at two U.S. cancer centers (Cone Health Cancer Center in Greensboro, NC, and Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, PA) and involved several strategies including training for providers on the root causes of health care inequities (Black et al., 2019), a data system (Real-Time Registry) that tracked patient progress in real time disaggregated by patient race (Cykert et al., 2020), and nurse navigators who supported patient engagement through data-informed care (Griesemer et al.). Results from ACCURE showed that prior to implementing the intervention, treatment completion rates in the population cohort at the two cancer centers (n = 8,945) were 79.8% for Black patients vs. 87.3% for White patients (p < 0.001). After ACCURE, the racial disparity among patients in the intervention group (n = 302) was nonsignificant (Black patients 88.4% and White patients 89.5%, p = 0.77). Multivariate analyses confirmed the intervention yielded a significant reduction in this disparity (Black-White OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.46, 2.1). Details of the trial evaluating ACCURE have been reported in a previous publication (Cykert et al., 2020).

Importantly, the ACCURE study used a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach, meaning community members affected by racial disparities in health care were involved in every phase of the project (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). The organization that designed the intervention and guided implementation was the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative (GHDC), a community-academic-medical research partnership founded in 2003 and based in Greensboro, NC. GHDC was established by Greensboro community members who wanted to understand and address racial disparities in health care through applied research. They interviewed and recruited academic researchers from the University of North Carolina to partner with them in applying for research funding from the National Institutes of Health (Yonas et al., 2006). That application led to the Cancer Care and Racial Equity Study (CCARES) (Yonas et al., 2013), which in turn led a larger grant that funded the development and implementation of ACCURE. Both studies were conducted through a CBPR process of organizing stakeholders from the local community and from medical and academics institutions to collaborate on system-change health disparities research and education. GHDC’s application of CBPR, including discussion of important issues such as navigating power dynamics and resource allocation, has been described in detail in prior publications (Black et al., 2021; Eng et al., 2017; Schaal et al., 2016; Yonas et al., 2013; Yonas et al., 2006).

1.1. Theoretical frameworks

1.1.1. Undoing Racism®

To design the ACCURE intervention, GHDC drew from principles described in Undoing Racism®, a resource developed by a collective of antiracist organizers and educators (The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, 2018). Upon joining GHDC, members are required to participate in the Racial Equity Institute’s Phase 1 workshop, a two-day antiracism training based on Undoing Racism®. The purpose of the workshop is to foster a shared analysis of the systems and structures that maintain oppression. Building a shared analysis of systemic racism is a common antiracism organizing strategy (Came & Griffith, 2018) and is foundational to GHDC’s approach to conducting antiracist research in health care systems. CCARES, GHDC’s research study prior to ACCURE, was informed by the Undoing Racism® principle of analyzing power (Table 1). The researchers studied institutional power in Cone Health by examining data sources and the flow of information regarding patient outcomes. GHDC identified a lack of data transparency in care outcomes, which in turn obscured racial inequities in treatment engagement and completion. CCARES also involved qualitative interviews with patients from Cone Health to examine barriers to quality care and racial differences in how patients experienced care (Yonas et al., 2013). Building on the foundation of this prior research, GHDC designed the components of ACCURE to: (1) enhance data transparency, and (2) apply the Undoing Racism® principle of maintaining accountability to communities to a racial equity-focused intervention in cancer care (Table 1).

Table 1.

Undoing Racism® principles applied in the development of ACCURE.

| Principle | Description (from PISABa) | Application |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Analyzing power | As a society, we often believe that individuals and/or their communities are solely responsible for their conditions. Through the analysis of institutional power, we can identify and unpack the systems external to the community that create the internal realities many people experience daily. | Formative research in the intervention development stage of ACCURE examined institutional power in the cancer care system. This work led GHDC to identify transparency as a key principle to guide the design of the ACCURE intervention.b |

| Maintaining accountability | Organizing with integrity requires that we be accountable to the communities struggling with racist oppression. | GHDC designed ACCURE to increase cancer center accountability to Black patients.b |

The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond.

See section 3.2 for an in-depth examination of how ACCURE applied the principles of transparency and accountability.

To our knowledge, ACCURE is the first health services intervention to use Undoing Racism® to guide intervention design. The principles of transparency and accountability are well documented in ACCURE (Black et al., 2019; Cykert et al., 2020; Eng et al., 2017; Schaal et al., 2016), but there is a lack of literature linking these principles to existing public health models. As public health leaders call on the field to dismantle structural racism built into systems of care (Choo, 2021; Crear-Perry et al., 2020; Hardeman et al., 2016), new models for intervention development that incorporate antiracism principles could advance research on effective strategies for enhancing racial equity in the delivery of health care.

1.1.2. Planned Adaptation Model

The present study was guided by the Planned Adaptation Model (Lee et al., 2008), which specifies a four-step process for adapting evidence-based interventions (Table 2). This model, along with research by Kirk and colleagues that offers methodological guidelines for applying the Planned Adaptation Model (2021)1, provides a systematic approach for documenting and adapting existing interventions so they can maintain effectiveness in new environments. The objective of the present study was to complete step one in the model: examine the original intervention’s theory of change by identifying mechanisms and key activities. We used first-hand narratives from those closest to the intervention to document how ACCURE changed systems of care.

Table 2.

Planned adaptation model.

| Step 1 | Examine intervention’s theory of change |

| Step 2 | Identify differences between old and new setting |

| Step 3 | Adapt intervention to new setting |

| Step 4 | Evaluate adapted intervention |

1.1.3. Social Ecological Model

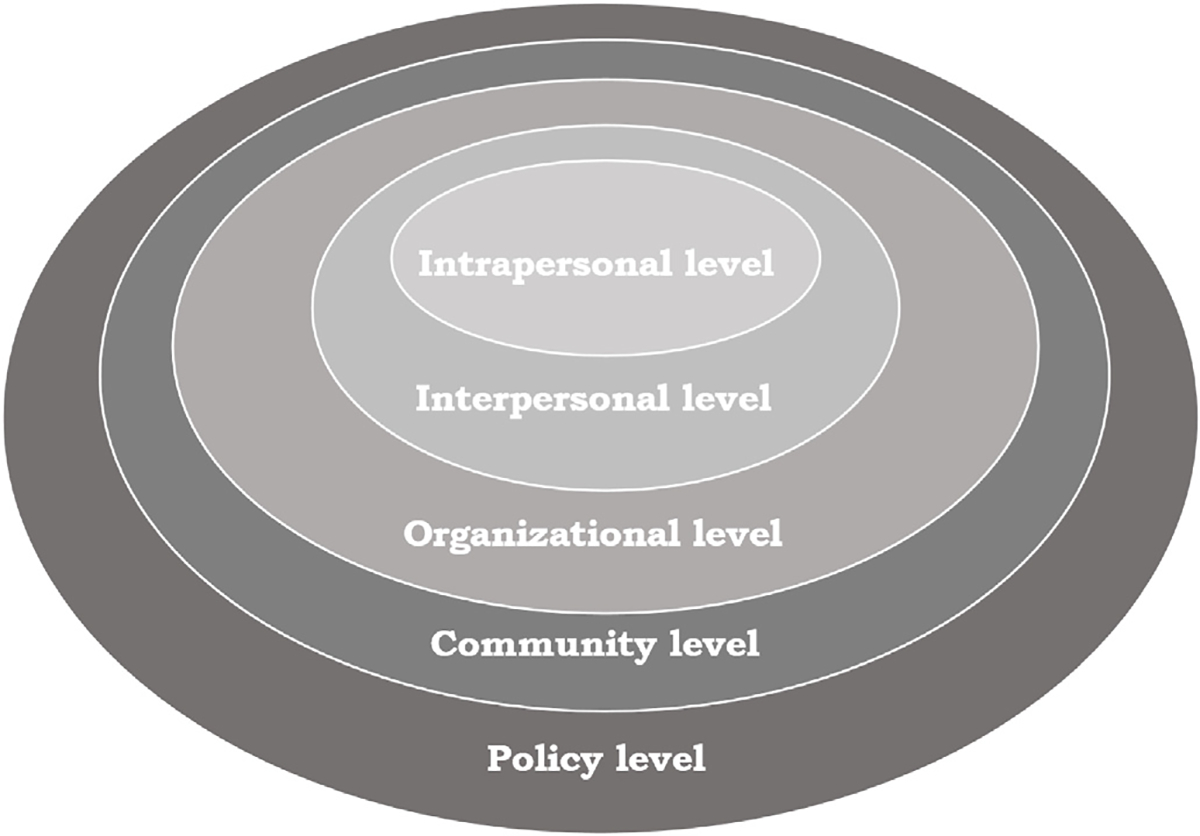

In the analysis stage of this study, we applied the Social Ecological Model (SEM), a widely used model in health promotion programs (Ma et al., 2017; McCormack et al., 2017), to synthesize our results (see section 3.2). The SEM describes levels at which it’s possible to intervene to address public health issues (McLeroy et al., 1988). The model is often depicted as concentric circles (Fig. 1), with the outer circles representing greater spheres of potential influence (e.g., policy, community, and organizational levels), and the inner circles representing interventions targeting individuals (interpersonal and intrapersonal levels). Interventions are more likely to be effective when targeting multiple levels of the SEM, compared to interventions focusing only on the inter or intrapersonal level (Hassen et al., 2021; Kellou et al., 2014). The SEM informed the interpretation of findings and contributed to our overarching aim: to document key characteristics of ACCURE to facilitate translation of the intervention in new settings.

Fig. 1.

Social Ecological Model.

2. Methods

This study was a post-hoc examination of the original ACCURE intervention, which took place from 2012 to 2018. The present study was conducted in 2019–2021 and involved three phases. We first reviewed materials documenting the ACCURE intervention, including publications describing the intervention development process and outcomes (Black et al., 20211; Cykert et al., 2020; Eng et al., 2017; Schaal et al., 2016) and procedure manuals. Next, we developed a semi-structured interview guide informed by the Planned Adaptation Model and previous research on documenting key characteristics of an evidence-based intervention (Kirk et al., 2021). We then recruited interview participants, conducted interviews, and analyzed the data to identify themes.

The research process was enhanced by a Community Advisory Board (CAB) made up of five members of GHDC. While the original ACCURE study was a CBPR process conducted in full partnership with GHDC, the present study was designed by the first author, a GHDC member, with advising from GDHC and her academic mentors. She formed a CAB to ensure that study design and analysis remained aligned with and accountable to the interests and values of the larger GHDC. The CAB met three times over the course of the study and members were compensated $25 per meeting. In the first meeting, which took place during study development, the CAB provided input on the interview guide. After data collection was complete, the CAB met again to review the initial findings. In the final meeting, we discussed the overall interpretation of the findings and the framing of the results. In addition, the CAB served as a bridge between the activities of present study and the larger GHDC by bringing the CAB members’ perspectives on the history of GHDC and ACCURE into discussions about the present study, and by bringing updates about the present study back to GHDC at monthly meetings. CAB members were invited to contribute to dissemination products from the study including this manuscript.

2.1. Participants and recruitment

We used purposive sampling to recruit participants who were actively involved in the design and implementation of ACCURE for in-depth interviews (Table 3). We aimed to recruit participants with a range of perspectives, including longstanding GHDC members with knowledge of prior research informing ACCURE and the rationale for the intervention, community-based research assistants directly involved with data collection, academic research staff who contributed to grant writing and project management, information technology specialists who designed the intervention’s data system, and cancer center administrators and providers who worked with researchers on study implementation, patient recruitment, and intervention delivery. Patient interviews were not conducted because the present study aimed to document ACCURE from the perspective of those who designed and delivered the intervention. CAB members were ineligible to participate in interviews. The first author consulted with ACCURE investigators to identify 20 potential participants with first-hand knowledge of the intervention. This pool represented the full group of individuals who had sufficient familiarity with ACCURE to provide insight into this study’s research questions. Participants were contacted by the first author via email and invited to participate in an interview about their involvement with ACCURE. If they agreed to an interview, the first author scheduled a time to meet. Potential participants who did not respond to the first email were sent a maximum of two follow-up emails.

Table 3.

Participant roles in ACCURE (n = 18).

| GHDCa member | Non-GHDC member | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Community research partners | ||

| GHDC Executive Board member | 1 | |

| Survey data coordinator | 1 | |

| Budget coordinator | 1 | |

| Research assistant | 2 | |

| Academic research partners | ||

| Principal Investigator | 2 | |

| Postdoctoral fellow | 1 | |

| Project manager | 1 | |

| Information technology specialist | 1 | |

| Medical research partners | ||

| Administrative leadership | 1 | 2 |

| Physician | 1 | 2 |

| Nurse navigator | 1 | |

| Information technology specialist | 1 | |

Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative.

2.2. Data collection

The first author conducted interviews (n = 18) between December 2019 and June 2020. Each interview lasted approximately one hour. The first nine interviews were conducted in-person at private locations convenient for participants. The remaining interviews were conducted via video conference due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The interviewer obtained verbal consent to participate in the research study from participants prior to each interview. Participants were compensated $20 per interview; seven participants waived compensation. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. All study procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institutional Review Board.

2.3. Analysis

The interviewer wrote memos after each interview, noting key topics and ideas that could be explored further. Deidentified transcripts were uploaded into Atlas.ti software. Guided by the Framework Method for qualitative health research (Gale et al., 2013), the first author developed a codebook of relevant categories in the interview data. Topical codes were deductive and based on previous research applications of the Planned Adaptation Model (Kirk et al., 2021). Additional codes were developed inductively during analysis to capture recurring themes. To assess reliability in coding, 20% of transcripts were randomly selected to be coded separately by a research assistant (R.J.). The analysts met twice to discuss discrepancies in coding and refine code definitions. The first author then updated the discussed transcripts and coded the remaining transcripts. Next, she used code reports and matrices to organize the data and identify themes across the interviews (Raskind et al., 2019). She then developed a model to visually represent key findings. CAB members provided feedback on the model and results. The first author also presented study findings in a GHDC meeting and invited input on whether the visual depiction of ACCURE accurately represented GHDC’s understanding of the intervention.

3. Results

The sample included 18 participants representing a range of roles in ACCURE and community, academic, and medical affiliations (see Table 3). The sample reflected the racial diversity of the ACCURE study team (participants identified as Black, White, and Asian) and included men and women. The results from the in-depth interviews are presented in two sections: (1) the motivation for ACCURE, and (2) an organizing model of ACCURE linking each intervention component to an underlying mechanism of change.

3.1. Motivation for ACCURE

Participants described two primary motivations for ACCURE: gaps in data reporting that obscured racial disparities in treatment outcomes, and commitment to a system-change intervention approach. These themes are discussed below with supporting quotations from interview participants.

3.1.1. Gaps in data reporting that obscured disparities

A key motivation among academic research partners was to improve data reporting and transparency in order to illuminate racial disparities, raise awareness among care system employees about treatment disparities in their organizations, and use the data to improve care quality. Participants referred to CCARES, prior research that pointed to gaps in how treatment data was reported in the Cone Health cancer registry database (Yonas et al., 2013). Patient race and treatment completion data were not consistently reported, and the information translated into the cancer registry often lagged months behind actual treatment time. ACCURE researchers viewed this time lag as a barrier to quality care because providers were unaware of which patients were falling behind on treatment until it was too late to reengage them in care. One participant explained,

“We … tried to look at the cancer registry to see what were the differences between Black and White women who have breast cancer, and there was so much missing data … that was a shocking kind of wake-up call to action among [GHDC] members … if we are going to eliminate a racial disparity, you have to first document that … The medical system partner had that information in medical charts, but it wasn’t in the cancer registry.” (Project manager)

This spurred the researchers to analyze cancer registry and medical records to document disparities in treatment outcomes among Cone Health patients. The process of analyzing data disaggregated by patient race illuminated racial disparities in treatment completion and links to higher mortality rates among Black patients. Another participant described cancer center providers’ reaction to the documented disparities:

“… so we used their cancer registry data and we analyzed it for them by race for the previous years, so that they can see that there were African American women dying from it. The doctors just … They didn’t know. They didn’t know who was not completing the care. They didn’t know who had died from it. They just don’t follow up and so they were very astounded by the data.” (Principal Investigator)

Through conversations with providers and leaders at the cancer center, the researchers learned that data were not often used for quality improvement efforts, and when they were, the usual approach was to examine outcomes across all patients in certain illness categories. One participant stated:

“… the providers and administrators are not always hearing about all these kinds of discrepancies in care between different racial groups because they didn’t have the data to really see it in real time, or at all, if no one was really looking at it. Because oftentimes people are looking at things as the whole group … and not looking between groups and seeing what maybe some of the differences are. So it’s kind of bringing attention to that in a way and having the data … to show that there was a true difference going on.” (Postdoctoral fellow)

This participant explained that due to gaps in data reporting, especially with regard to patient racial identity groups, there was a lack of awareness among cancer center staff about disparities in treatment outcomes. Racial disparities were present in the data, but because the data were not stratified and examined by patient race, the disparities were obscured. These findings helped motivate Cone Health to partner with GHDC in developing a grant proposal to design an intervention aimed at addressing documented disparities.

3.1.2. Commitment to a system-change intervention approach

Participants also emphasized GHDC’s commitment to a system-change approach to enhance racial equity in health care organizations. In explaining this motivation, one participant referred to the qualitative interviews conducted with patients in CCARES, stating, “Well, the motivation was to actually try and intervene in the system. Recognizing, from people’s lived experience and from our data from CCARES, how do we approach a system and influence people’s outcomes within the system?” (Survey data coordinator). This participant highlighted the link between patient experiences documented in prior research (Yonas et al., 2013) and GHDC’s commitment to addressing disparities in care outcomes by implementing changes at the organizational level.

Another participant discussed the antiracism training that informs GHDC’s work as an inspiration for the system-change approach. She said:

“… part of the [ACCURE] interventions were inspired by … the racial equity training, which suggested ways to undo the historical impacts of racism … focusing on changing the health care system. Not trying to change the people, but trying to change the health care system … too much blame is put on communities and the people themselves, when they’re not always the decision makers for what’s happening [to] them [and] for the pressure that they experience … and so we need to change institutions.” (Project manager)

This sentiment was expressed across the interviews, with many participants stating that the motivation for the intervention was to implement strategies focused on changing the health care system, as opposed to changing individuals. Another participant emphasized the importance of addressing racism from a systems perspective, stating:

“When you see disparities, how do you correct those? How do you correct it from a system versus for somebody’s implicit bias or how they view a person of color? How do you change a system where, regardless of your implicit bias or your ideology or your beliefs, it won’t affect the amount of treatment? Because … everybody should get the same. How do you make the system do that versus the individual do that?” (GHDC Executive Board member)

The questions raised by this participant illuminate the research team’s commitment to implementing changes that were integrated into the operations of the care system. GHDC members viewed system-change as the foundation of their approach. Intervening to address biases and beliefs held by individual providers was a complementary strategy, but, in this participant’s view, would not be sufficient to enact lasting change if implemented alone.

3.2. An organizing model of ACCURE: Transparency, accountability, and the Social Ecological Model

Participants’ theory of change for how ACCURE worked to eliminate the racial disparity in treatment completion was grounded in the antiracism principles of transparency and accountability, which had informed the design of the original ACCURE intervention. While the present study was not designed specifically to examine these principles, the influence they had on ACCURE was evident in the data. Throughout the interviews, participants emphasized transparency and accountability as mechanisms that were essential to intervention success. These principles were operationalized in each intervention component, described below.

Data from the interviews also indicated that participants understood ACCURE as a multilevel intervention: “a layered approach” (Survey data coordinator). We applied the Social Ecological Model (Fig. 1) to our analysis to examine the multilevel nature of participants’ descriptions of the principles of transparency and accountability. Three levels of the SEM were represented in ACCURE: the community, organizational, and interpersonal levels. Participants discussed transparency and accountability as operating across these three levels, linking the principles to themes of community involvement, organizational change, and interpersonal support for patients across the dataset. To illustrate this, we developed a model that overlays transparency and accountability with the three levels of the SEM that were key to ACCURE (Fig. 2). We then mapped the intervention components onto the levels. The components listed on the left side of the model worked to enhance transparency, while the components listed on the right worked to enhance accountability. The sections below describe how ACCURE worked at each level, using supporting data from the interviews to underscore the rationale for each component in the context of transparency and accountability.

Fig. 2.

An organizing model of ACCUREa.

aIn this model, ACCURE’s intervention components are mapped onto three Social Ecological levels and the antiracism principles of transparency and accountability.

3.3. Community-level components

Community-based partnership.

At the community level, the foundational component of ACCURE was a strong community-based partnership with academic, medical, and community partners (GHDC), which directed the project and maintained accountability to pre-established collective values. Participants emphasized that accountability to a community-led organization was critical to the process of designing an equity-focused intervention. One participant stated,

“Well, the community accountability part … that’s a critical part … health care systems think they can just recreate the actual interventions that we did with ACCURE, and they can, but what makes it stronger is having a community-accountable partner to ask questions along the way. And the … partner needs to be a group of people who in some way represent and identify with … the racial disparity that’s going on, whether they are part of the same racial identity group or they’re part of the disease condition … or they know close loved ones to them.” (Project manager)

Emphasizing the importance of community involvement from the outset and throughout the process, another participant said,

“… having a community-based organization that’s grounded in the equity work. That was a key component. That had an active role in the development of that from beginning … having some community body … that’s engaged in constant conversation about what’s going on. So, you’re reporting to them and then they’re given the space and time to give input.” (Postdoctoral fellow)

This quotation highlights the ongoing nature of GHDC’s involvement with ACCURE, and the importance of providing multiple opportunities for community-based research partners to provide feedback on the intervention development and implementation process.

Antiracism training.

Participants described antiracism training as foundational to the intervention. The training allowed community, academic, and medical research partners to establish a common understanding of the rationale for the intervention’s system-based approach. One participant stated,

“I would say that having racial equity or antiracism training for essential staff is a baseline. There needs to be a common understanding of systemic inequity. And even in a highly educated people, there’s usually a major gap in their understanding of systemic inequity. And so, I think that has to be foundational.” (Survey data coordinator)

This participant described the training as an important requirement for research partners involved with the intervention, regardless of their educational background. A physician involved with the ACCURE study described the transformational effect that antiracism training had on his understanding of racial disparities:

“… as much as I was aware of racial disparities in health care and the outcomes, I wasn’t really aware of the institutional underpinnings of why we ended up with the system we currently have. It was helpful … I found myself at that time when I became the lung cancer champion not necessarily really accepting that there was institutional racism and it wasn’t until the mandated two-day training session that it really hit home with me that, okay, now I really understand.” (Physician)

The participant recognized that the antiracism training prompted a shift in his understanding of institutional racism, which in turn strengthened his understanding of the rationale for ACCURE’s system-change approach. This was especially important, because as a physician champion for the study, the participant was tasked with galvanizing support for the intervention among cancer center staff. A cancer center administrator described the impact the historical aspect of the antiracism training on how she viewed her work:

“I think knowing the history allows you to see injustice, and then to begin to say with transparency, this was unjust. How do we go back now? You can’t rewrite history and all the patients that have come through, but how do we change it so that history doesn’t repeat itself? … what’s been most helpful is to take these antiracism principles of the transparency of the data and the accountability to change.” (Administrative leadership)

This quotation highlights the participant’s thought process that led them to connect the lessons from the antiracism training to the principles of transparency and accountability that were operationalized in ACCURE.

Ongoing communication.

GHDC met monthly over the course of the ACCURE study. This ongoing communication allowed research partners to continually discuss study design and implementation issues, express concerns, and weigh in on decisions. GHDC members led all stages of the research process, from writing the grant application, to selecting measures and developing the script for patient telephone surveys, to adapting the protocol during the study to address implementation barriers. One participant explained,

“… we all worked through the plan because we were so invested in writing the application, so we knew what the plan was. And so, if there was deviation from it, we knew we would come to [GHDC] and say, ‘Okay, do you agree with this deviation? Do you agree with this budget cut?’ Those kind of things.” (Principal Investigator)

At times, discussions at GHDC meetings led to interpersonal conflict among members with diverse perspectives on the best way to proceed. Participants who were longtime GHDC members viewed these conflicts, and the ability to work through them together without silencing or minimizing anyone’s perspective, as a core strength of the group. One participant said,

“… it’s the consistency of the group to stay together, the consistency of the group to have transparent and real conversations … From those conversations you can … work out some stuff before you even go to Cone [Health Cancer Center]. When you go to Cone, you know what your focus is and what you’re trying to do.” (GHDC Executive Board member)

This quotation lays out the participant’s perspective on how having difficult conversations internally at GHDC meetings allowed the group to strengthen their pitch to medical partners to get them to engage with the research project.

3.4. Organizational-level components

The community-level research partnership was the foundation that allowed the ACCURE research partners to develop an organizational change intervention to address racial disparities in cancer treatment. The key intervention components at the organizational level have been described in previous publications (Cykert et al., 2020; Eng et al., 2017). The data from the present study reinforced the centrality of these components (the data system, training mechanism, and advocacy roles) and pointed to an additional factor at the organizational level: leadership that is open to change and committed to authentic partnership with community members. Here, we use evidence from the present study to underline the rationale for each component.

Organizational leadership.

In describing the relationship-building process among community, academic, and medical research partners that led up to implementation of ACCURE, participants spoke about the process of creating buy-in among leaders in the care system over several years prior to developing the ACCURE intervention. A community-based participant described some of the key questions that GHDC members had about Cone Health’s role in the project and the organization’s readiness to change:

“Will Cone change? Will they want to change? How much of a change would this affect them, based on their processes, based on their finances, or just the fact that our outside community-based or ‘relationship organization’ is going to actually say that you need to change something? How will they respond?” (GHDC Executive Board member)

This participant emphasized the need for openness among the care system’s leadership and an interest in facilitating an equity-focused intervention. Participants also discussed the CBPR approach of the intervention as important to the relationship-building process with Cone Health. Community research partners were actively involved with discussions with cancer center leaders, underscoring the importance of ongoing communication with and accountability to community members affected by care system disparities.

Data system.

Many participants described the crux of the intervention as the data system that was connected to the electronic health records. The system collected data in real-time and alerted medical staff to deviances from standard care. One participant described the data system, which was called the Real-Time Registry, as “the backbone of ACCURE.” He went on to say, “We always knew where the patient was in their care process, and if they didn’t go through the steps that were programmed in the Registry ... a warning would come up” (Principal Investigator). Another participant described the purpose of the Real-Time Registry as making sure patients did not fall through the cracks by tracking their appointment data and flagging missed milestones in their cancer treatment. The Real-Time Registry enhanced transparency so employees in the care system could see when a patient was not receiving their recommended treatment in a timely manner. A participant said, “The Real-Time Registry provided that real-time transparency, and was also the tool of accountability because a warning came up, and somebody had to deal with it” (Principal Investigator). By linking the warning flags produced by the Real-Time Registry to a designated role in the care system (in this case, the ACCURE navigators, described below) the data system leveraged transparency to prompt accountability in the care system to reach out to patients and address barriers to quality care.

Training mechanism.

Another intervention component that enhanced transparency at the organizational level was training sessions for cancer center staff, known as Health Equity Education Training (HEET) sessions (Black et al., 2019). The content of the sessions was informed by focus groups with Black and White cancer survivors, conducted in the intervention development stage of ACCURE, to better understand patient experiences and to identify care system-related barriers that affected treatment engagement. Focus group participants were asked to describe interactions with the care system that were “pressure points,” or times when institutional factors created barriers to remaining engaged in treatment. The focus group findings highlighted a lack of accountability of the care system to provide patients, especially those who identified as Black, with sufficient support to navigate their cancer treatment (Black et al., 2021; Eng et al., 2017). These findings, along with site-specific data on care quality metrics, disaggregated by patient race, were presented to cancer center staff during the HEET sessions. Participants said that the training sessions played an important role in raising awareness among cancer center staff about the systemic nature of health disparities and enhancing transparency regarding care inequities at the clinic level. One participant said,

“… the goal was to increase awareness of the staff regarding disparities from a systemic lens to help them understand the disparities. When we talk about disparities, it’s not about individual acts of meanness, it’s about systemic barriers. And then to engage them in thinking about those systemic barriers so that not only are we trying to address the people enrolled in the study, but also helping the staff to evolve their lens about what racial equity means and how it shows up. So that hopefully future problem solving can be done from a more systemic perspective.” (Survey data coordinator)

The HEET sessions increased transparency in the institution-level barriers that contribute to disparities. Another participant described the effect that increased transparency around institutional racism had on providers: “I think that in some ways the staff were awakened and had a better understanding of how patient outcomes may be driven by their skin color or by their race rather than all the treatments we’re offering. I think there was some eye-opening moments for clinicians in the program” (Physician). This quotation demonstrates the roll the HEET sessions played in raising awareness among cancer center staff about how racism can affect patient care.

Advocacy roles.

Accountability at the organizational level included advocacy roles (i.e., physician champions and ACCURE navigators) adapted from existing provider roles. These roles involved additional training and specialized protocols created specifically for the intervention (Black et al., 2019). Physician champions were intended to advocate for study goals from within the cancer center, support providers in adapting to and engaging with structural changes such as the Real-Time Registry and HEET sessions, and help disseminate site-specific data on treatment disparities. One participant described the role physician champions played in bringing other physicians on board with ACCURE recruitment goals: “The physician champion was the local study cheerleader. We really need to enroll these patients … one of their main jobs was to motivate others to be interested in bringing patients into the study” (Principal Investigator). Another participant emphasized the importance of the physician champion as a link from community partners to cancer center leadership:

“There has to be a physician champion. There has to be a clear pathway to the top of the breast cancer center or the head of Moses Cone [Cancer Center]. There has to be this open dialogue … with those in academia, Moses Cone and whoever the community partners are.” (GHDC Executive Board member)

The ACCURE navigators were also a key accountability component at the organizational level. They were integrated into the care team, meaning they attended weekly meetings among surgeons and oncologists to discuss patients’ treatment recommendations, and communicated patients’ needs and concerns with providers. Participants described the rationale for the ACCURE navigator role as the link between data transparency enabled by the Real-Time Registry and the delivery of quality care to patients. One participant explained:

“Well, certainly the Real-Time Registry is important, but … without a follow up plan I don’t think [it] would be helpful … The system takes responsibility for following up with the missed milestones. The nurse navigator model worked really well for us … there has to be a mechanism of accountability to the missed milestones.” (Survey data coordinator)

This participant suggested that other roles in the care system could be adapted to fulfill this aspect of the intervention. Another participant emphasized the need for accountability within the care system to follow up with patients who may need tailored support to remain engaged in treatment:

“Whenever a patient goes through the system, especially when there’s a sequence of treatments, who is responsible for ensuring that both sides of the sequence happen, that the planners of the sequence do their thing, and the patient shows up and does their thing? People can look at each other, and have a bystander. ‘Oh, I thought it was you’ … no one has direct responsibility in a patient-centered fashion, then things are much more likely to fall through the cracks, especially when the person coming through the system is disadvantaged somehow.” (Principal Investigator)

This participant articulated a gap in accountability in the care system that may contribute to treatment disparities. The ACCURE intervention’s solution for this gap was the interpersonal-level support provided to patients through the ACCURE navigators.

3.5. Interpersonal-level components

Patient advocates.

The ACCURE nurse navigators connected the organizational level, system-based aspects of the intervention to patients with cancer through individualized support. They were the patient-facing aspect of the intervention who provided care system accountability to patient needs. Prior to the intervention, the ACCURE navigators at both study sites participated in the antiracism training which reframed the responsibility for identifying and managing treatment obstacles from falling primarily on the person with cancer. Instead, ACCURE navigators shared this responsibility and were trained to proactively reach out to patients who were falling behind on treatment milestones such as scheduling surgery or attending chemotherapy appointments. Participants described the ACCURE navigators as a critical component of the intervention. One participant spoke about specific personality traits that were important for carrying out the navigator role:

“The nurse navigator, she was essential … I think a lot of it also had to do with the personality and the person, and the empathy and the compassion she had. The fact that she wanted everyone to have equal footing in reaching either long term survival, cure, or whatever it may be, for their cancer. She genuinely cared.” (Administrative leadership)

In an interview with the ACCURE navigator at one of the study sites, she described key qualifications for the role: “Good listening skills, good communication skills, organization skills, empathy, compassion.”

Describing the impact the ACCURE navigator had on patient care at the cancer center, one physician said: “… it was a continuity of care throughout their journey of treatment … that human connection with having that patient navigator who is aware of the conversation and the treatment plan and the next steps … that agent is vitally important.” This quotation demonstrates how the ACCURE navigators enhanced two-way communication between patients and the care system, which allowed for greater transparency. For patients, there was more transparency in their treatment plan and what they could expect in terms of their treatment schedule and side effects. For providers, there was also increased transparency around obstacles patients were experiencing that interfered with their ability to remain engaged in treatment. This two-way communication allowed navigators to bridge communication gaps between patients and oncologists, and to support patients by offering resources such as transportation vouchers or referrals to specialists. The direct link between the ACCURE navigators and the Real-Time Registry allowed the navigators to see when a patient was falling behind on their treatment and use that information to reengage patients in care.

4. Discussion

This study documents ACCURE’s motivation, mechanisms of change, and key components from the perspective of community, academic, and medical research partners who designed and implemented the intervention. GHDC’s emphasis on changing systems, and the desire to move beyond documenting disparities to intervention, were driving forces in ACCURE. Findings from the interviews indicate that the antiracism principles transparency and accountability were effective change mechanisms in an equity-focused health services intervention in cancer care. ACCURE embedded these principles into the routine practice of care delivery across community, organizational, and interpersonal levels to address structural factors in the care system that contribute to treatment disparities and, in turn, improve care quality for all patients (Cykert et al., 2020). The key components identified in this study (i.e., the bullet points in Fig. 2) were: a community-based partnership with antiracism training and ongoing communication among research partners, a Real-Time Registry data system, a provider training mechanism, buy-in from organizational leaders, advocates for the intervention itself (physician champions), and patient advocates (navigators).

A recent systematic review synthesized commonalities among antiracism interventions in health care settings (Hassen et al., 2021). While the article search for the review was conducted in 2018, prior to publication of the study documenting ACCURE’s success in eliminating a Black-White disparity in treatment completion, the review’s findings mirror many of the strategies employed by ACCURE. Hassen and colleagues lay out a conceptual model that names six foundational elements of a health care-based antiracism intervention, all of which were applied in ACCURE: defining the problem, using shared antiracism language, establishing leadership buy-in, investing resources, partnering with experts, and establishing community partnership. The review also highlights “transparent accountability mechanisms” as a key strategy for antiracism interventions (Hassen et al., 2021, p. 12). The ACCURE intervention predates this review and yet the findings from the present study are congruent with the conceptual model presented by Hassen and colleagues. Our study adds to this body of work by offering a model of an evidence-based intervention that depicts specific strategies for operationalizing transparency and accountability at multiple levels.

A methodological contribution of this study is the visual display of interview findings, an underused approach in qualitative inquiry (Kegler et al., 2019). The model presented in this manuscript (Fig. 2) provides health services researchers and practitioners with a practical resource to understand the components in the ACCURE intervention. The original study evaluated the overall impact of the intervention, and thus was not designed to tease out differential effects of the intervention components. Future research should use this new model to facilitate more complex study designs in adapted versions of ACCURE, so researchers can compare the impact of various components (e.g., cluster-randomized trials). Additionally, the original study did not include organization-level measures. Future research should consider measures at the organizational level to evaluate the degree to which various components contributed to organizational change. This could include the development of new measures to evaluate change in organizational transparency around care metrics and accountability to the population served.

As the purpose of this study was to document ACCURE’s key components, an examination of the original intervention’s implementation barriers and facilitators is beyond the scope of this manuscript. Here, we will briefly highlight one challenge that came to light in the interviews regarding the implementation of the HEET sessions. At Cone Health, a cancer center in a community hospital, the training sessions were held in the evening and attendance was low. This contrasted with Hillman Cancer Center, which is an academic hospital that holds regular Grand Rounds educational sessions for cancer center staff. At Hillman Cancer Center, the HEET sessions were held at Grand Rounds during the workday. One participant pointed to this inconsistency as evidence that the HEET sessions were less essential to the intervention’s success, stating, “The lessons are important, but they didn’t drive the improved care” (Principal Investigator). However, even at Cone Health where attendance at the sessions was low, several participants noted the impact they had on the organization even beyond ACCURE’s active intervention stage. A physician stated, “We’ve brought back some of the HEET session modules … to the cancer center and it’s always eye-opening for the staff to be introduced to a new concept like that … it can be very impactful.” Future adaptations of ACCURE should consider the implementation context, including the question of whether there is an existing infrastructure for staff training.

When considering implementation strategies for the overall intervention, we recommend referring to emerging guidance on applying an antiracist lens to implementation science. A foundational piece is partnering with community stakeholders whose lived experiences represent those most impacted by health care disparities when adapting evidence-based interventions (Shelton et al., 2021). These partnerships will be important in the process of adapting ACCURE to the values and needs of a specific community. For example, we can imagine that while race-specific data tracking was a strategy favored by GHDC in designing the original intervention, other community groups may find this type of data monitoring intrusive or harmful. Community-guided adaptation will allow future versions of ACCURE to be grounded in the expertise and lived experiences of local community members.

4.1. Limitations

The interviews for this study were conducted three years after the ACCURE study concluded, so the data may have been subject to recall bias due to participants not correctly remembering certain details or events related to the intervention. While we were able to recruit nearly all key study personnel to participate in interviews, two were not available, which may have biased the data toward greater representation of the experiences of Cone Health employees as compared to Hillman Cancer Center employees. Additionally, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we transitioned data collection from in-person to video conference halfway through the study. This change did not appear to affect the quality of the data. In interviews that took place during that period, participants were more likely to bring up the pandemic’s impact on the health system.

5. Conclusion

Despite challenges researchers encountered when designing and implementing ACCURE, the intervention worked to improve quality and racial equity in cancer care (Cykert et al., 2020). The antiracism principles of transparency and accountability guided every aspect of the intervention. The vibrant partnership fostered by GHDC and the commitment among members to contribute to impactful racial equity research were foundational to the study’s success. One participant summarized the character of GHDC in saying:

“The basic principle of [GHDC] is an understanding of racial equity principles. And I think what’s most important … is to have an enthusiasm for racial equity work … you have to believe in the importance of it and have a willingness to stretch yourself, because I think part of what makes [GHDC] work is people being deeply enough engaged that they can tolerate the discomfort of being challenged.” (Survey data coordinator)

In developing a research partnership where members are open to having their views challenged and are committed to working collectively towards a common goal, future researchers can use the organizing model of ACCURE to design equity-focused health services interventions that are guided by the principles of transparency and accountability. Evidence from the ACCURE intervention suggests that future interventions are most likely to be successful if they are developed in partnership with community-based researchers, involve systematic changes at the organizational level, and are responsive to the unique characteristics of the health system and patient population.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is dedicated to Claire Morse, in loving memory and faithful commitment to her legacy as an antiracist organizer. We would also like to express gratitude to Fatima Guerrab and Thomas Clodfelter for their contributions to this research.

Funding

This study was funded by a National Research Service Award Pre-Doctoral Traineeship (for I. Griesemer) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, sponsored by The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [grant number T32-HS000032] and a NC Translational and Clinical Studies Institute (TraCS) pilot grant, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS, National Institutes of Health [grant number UL1TR002489]. Writing of this manuscript was also supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Health Services Research, the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research (CHOIR), Boston, MA (for I. Griesemer).

Abbreviations

- ACCURE

Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity

- CBPR

Community-Based Participatory Research

- GHDC

Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative

- CAB

Community Advisory Board

- CCARES

Cancer Care and Racial Equity Study

- SEM

Social Ecological Model

- HEET

Health Equity Education Training

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References dated 2021 were accessed in 2019–2020 prior to formal publication as online or preprint versions with permission from the authors.

References

- Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, & Bassett MT (2021). How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of US racial health inequities. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(8), 768–773. 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, & Bassett MT (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MT, & Graves JD (2018). Uprooting institutionalized racism as public health practice. American Journal of Public Health, 108(4), 457–458. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black KZ, Baker SL, Robertson LB, Lightfoot AF, Alexander-Bratcher KM, Befus D, … Eng E (2019). Health care: Antiracism organizing for culture and institutional change in cancer care. In Ford CL, Griffith DM, Bruce MA, & Gilbert KL (Eds.), Racism: Science & tools for the public health professional (pp. 283–302). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Black KZ, Lightfoot AF, Schaal JC, Mouw MS, Yongue C, Samuel CA, Faustin YF, Ackert KL, Akins B, Baker SL, Foley K, Hilton AR, Mann-Jackson L, Robertson LB, Shin JY, Yonas MA, & Eng E (2021). It’s like you don’t have a roadmap really: Using an antiracism framework to analyze patients’ encounters in the cancer system. Ethnicity and Health, 26(5), 676–696. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1557114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Came H, & Griffith D (2018). Tackling racism as a “wicked” public health problem: Enabling allies in anti-racism praxis. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 181–188. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, Casey AA, Goddu AP, Keesecker NM, & Cook SC (2012). A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(8), 992–1000. 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo E (2021). Easy in, tough out: The dam of health-care racism. The Lancet, 397(10274), 570. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00299-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crear-Perry J, Maybank A, Keeys M, Mitchell N, & Godbolt D (2020). Moving towards anti-racist praxis in medicine. The Lancet, 396(10249), 451–453. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31543-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cykert S, Eng E, Manning MA, Robertson LB, Heron DE, Jones NS, Schaal JC, Lightfoot A, Zhou H, & Yongue C (2020). A multi-faceted intervention aimed at Black-White disparities in the treatment of early stage cancers: The ACCURE Pragmatic Quality Improvement trial. Journal of the National Medical Association, 112(5), 468–477. 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, & Siegel RL (2019). Cancer statistics for african Americans, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(3), 211–233. 10.3322/caac.21555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Schaal J, Baker S, Black K, Cykert S, Jones N, Lightfoot A, Robertson L, Samuel C, & Smith B (2017). Partnership, transparency, and accountability. In Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M, & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (pp. 107–122). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, & Redwood S (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesemer I, Lightfoot AF, Eng E, Bosire C, Guerrab F, Kotey A, … Robertson LB Examining ACCURE’s nurse navigation through an antiracist lens: Transparency and accountability in cancer care. Health Promotion Practice. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Yonas M, Mason M, & Havens BE (2010). Considering organizational factors in addressing health care disparities: Two case examples. Health Promotion Practice, 11(3), 367–376. 10.1177/1524839908330863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR (2020). Examining racism in health services research: A disciplinary self-critique. Health Services Research, 55(Suppl 2), 777. 10.1111/1475-6773.13558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR, Medina EM, & Kozhimannil KB (2016). Structural racism and supporting Black lives - the role of health professionals. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(22), 2113–2115. 10.1056/NEJMp1609535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassen N, Lofters A, Michael S, Mall A, Pinto AD, & Rackal J (2021). Implementing anti-racism interventions in healthcare settings: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2993. 10.3390/ijerph18062993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP (2002). Confronting Institutionalized Racism. Phylon (1960-), 50(1/2), 7–22. 10.2307/4149999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, Raskind IG, Comeau DL, Griffith DM, Cooper HLF, & Shelton RC (2019). Study design and use of inquiry frameworks in qualitative research published in health education & behavior. Health Education & Behavior, 46(1), 24–31. 10.1177/1090198118795018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellou N, Sandalinas F, Copin N, & Simon C (2014). Prevention of unhealthy weight in children by promoting physical activity using a socio-ecological approach: What can we learn from intervention studies? Diabetes and Metabolism, 40(4), 258–271. 10.1016/j.diabet.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk MA, Haines ER, Rokoske FS, Powell BJ, Weinberger M, Hanson LC, & Birken SA (2021). A case study of a theory-based method for identifying and reporting core functions and forms of evidence-based interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(1), 21–33. 10.1093/tbm/ibz178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largent EA (2018). Public health, racism, and the lasting impact of hospital segregation. Public Health Reports, 133(6), 715–720. 10.1177/0033354918795891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Altschul I, & Mowbray CT (2008). Using planned adaptation to implement evidence-based programs with new populations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 290–303. 10.1007/s10464-008-9160-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma PH, Chan ZC, & Loke AY (2017). The socio-ecological model approach to understanding barriers and facilitators to the accessing of health services by sex workers: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 21(8), 2412–2438. 10.1007/s10461-017-1818-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack L, Thomas V, Lewis MA, & Rudd R (2017). Improving low health literacy and patient engagement: A social ecological approach. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(1), 8–13. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, & Glanz K (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3068205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AR, Stith AY, & Smedley BD (2002). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (full printed version). National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MI, Lopez AM, Blackstock W, Reeder-Hayes K, Moushey EA, Phillips J, & Tap W (2020). Cancer disparities and health equity: A policy statement from the American society of clinical Oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(29), 3439–3448. 10.1200/JCO.20.00642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The People’s Institute for survival and beyond.(2018). PISAB. Retrieved September 26, 2019 from https://www.pisab.org/about-us/. [Google Scholar]

- Raskind IG, Shelton RC, Comeau DL, Cooper HLF, Griffith DM, & Kegler MC (2019). A review of qualitative data analysis practices in health education and health behavior research. Health Education & Behavior, 46(1), 32–39. 10.1177/1090198118795019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal JC, Lightfoot AF, Black KZ, Stein K, White SB, Cothern C, Gilbert K, Hardy CY, Jeon JY, & Mann L (2016). Community-guided focus group analysis to examine cancer disparities. Progress in community health partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 10(1), 159. 10.1353/cpr.2016.0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton RC, Adsul P, Oh A, Moise N, & Griffith DM (2021). Application of an antiracism lens in the field of implementation science (IS): Recommendations for reframing implementation research with a focus on justice and racial equity. Implementation Research and Practice, 2. 10.1177/26334895211049482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, & Duran B (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), 312–323. 10.1177/1524839906289376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, & Davis BA (2019). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 105–125. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonas MA, Aronson R, Schaal J, Eng E, Hardy C, & Jones N (2013). Critical incident technique: An innovative participatory approach to examine and document racial disparities in breast cancer healthcare services. Health Education Research, 28(5), 748–759. 10.1093/her/cyt082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonas MA, Jones N, Eng E, Vines AI, Aronson R, Griffith DM, White B, & DuBose M (2006). The art and science of integrating undoing racism with CBPR: Challenges of pursuing NIH funding to investigate cancer care and racial equity. Journal of Urban Health, 83(6), 1004–1012. 10.1007/s11524-006-9114-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]