Abstract

Background:

Community-based needs assessments are instrumental to address gaps in data collection and reporting, as well as to guide research, policy, and practice decisions to address health disparities in under-resourced communities.

Objectives:

The NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health collaboratively developed and administered a large-scale health needs assessment in diverse, low-income Asian American and Pacific Islander communities in New York City and three US regional areas using an in-person or web-based, community-engaged approach.

Methods:

Community-engaged processes were modified over the course of three survey rounds, and findings were shared back to communities of interest using community preferred channels and modalities.

Lessons Learned:

Sustaining multi-year, on-the-ground engagement to drive community research efforts requires active bi-directional communication and delivery of tangible support to maintain trust between partners.

Conclusions:

Findings to facilitate community health programming and initiatives were built from lessons learned and informed by new and existing community-based partners.

Introduction

Local, regional, and national datasets are often used to guide research and inform health policy in order to steer resource allocations. However, these datasets often oversample higher income, English proficient communities, and present limited or aggregate data on racial/ethnic subgroups, potentially masking and perpetuating existing inequities in resource access (1). Asian Americans (AAs), Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders (NH/PIs) are a heterogeneous population with diverse cultures, languages, socio-demographics, and immigration histories, and research has shown a wide variation of health disparities and lived experiences among disaggregated AA and NH/PI subgroups, including among low-income, limited English proficient (LEP) immigrant AA and NH/PI populations (2). For example, studies have found that diabetes prevalence is higher among many AA and NH/PI subgroups as compared to non-Hispanic Whites (3–5). Across the US, the NH/PI alone population grew by 35.4% between 2000 and 2010 (6). A total of 14.1% of the population in New York City (NYC) are AA alone (7), and between 1990 and 2019, the AA population in NYC nearly doubled (8).

Community-level surveying and disaggregation by detailed race/ethnicity during data collection, analysis, and reporting can complement existing local and regional datasets and add nuance to guide research, policy, and practice decisions to better address health disparities. The Community Health Resource and Needs Assessment (CHRNA) was administered in community-based settings to reach immigrant, limited-English proficient (LEP) AAs, Arab Americans and NH/PIs using an in-person, in-language, community-engaged, and community venue-based approach. This paper’s objectives are to: 1) describe our community-engaged participatory process to develop, implement, and disseminate the CHRNA survey; 2) present our process and strategies for sustained community partnership throughout the research process; and 3) highlight our lessons learned and effective community-based participatory research (CBPR) practices.

Methods

Study Design

The overall objectives of CHRNA are to: 1) gather cross-sectional data to better understand existing community needs and health priority areas of underrepresented AA, Arab American, and NH/PI communities in NYC and three regional areas with understudied AA or NH/PI populations in Georgia, Arizona, and Utah; 2) identify resources available to AAs (Rounds 1–3), Arab Americans (Round 2), and NH/PIs (Round 3); and 3) identify best approaches to meet the needs of these communities.

NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH)’s research efforts are guided by an integrative population health equity framework and agenda that employs a participatory approach to health disparities research, and uses implementation and systems science approaches to address diverse AA and NH/PI community health needs (9), as well as highly engaged, collaborative partnerships with multisectoral stakeholders and organizations embedded within AA and NH/PI community settings both in metropolitan NYC and across the US. Our working relationships have honed CSAAH’s familiarity and knowledge of diverse AA and NH/PI communities, verified existing patterns in health disparity issues faced by the AA and NH/PI communities our partners serve, and underscored historic and ongoing systemic challenges partners encounter when working to improve communities’ access to care. CSAAH contributes our expertise to bolster the research, training, and resource needs of our partners, such as through adapting implementation of evidence-based strategies for AA subgroup communities, sharing best practices, providing grant writing technical assistance to community organizational staff, and facilitating connections to local clinical or academic partners to support health engagement efforts. Community partners familiar with CSAAH’s research expertise in survey design and implementation noted community surveying as a potential area of opportunity for collaboration; pursuit of this effort led to the initial development and implementation of the CHRNA (10).

The CHRNAs were led by community-based organizations (CBOs) using a tool co-developed with CSAAH. Applying a CBPR approach to plan, develop, and implement the CHRNA ensured meaningful reach into underserved communities across community settings, the development of culturally- and linguistically-tailored survey instruments, and the fostering of long-term community-academic partnerships between CSAAH and community stakeholders (11). We undertook a community-engaged research process and worked collaboratively with community partners to build trusting, bi-directional relationships to achieve a common goal (12, 13). Partners were involved in all aspects of the research, from conception to dissemination. CHRNA utilized a social determinants of health framework (14), which aligns with CSAAH’s overall research aim to promote health access for underserved racial/ethnic communities (15).

Prior to the Round 1, CSAAH invited CBO established partners to bring other community stakeholders to share ideas at in-person, open-forum meetings. We repeated this approach prior to Round 2 to hear needs and gather community-informed topic areas of interest with both NYC-based partners who had participated in Round 1 and community groups who had expressed interest but who had not participated in Round 1. Community partners verbalized their need for resources or data to better serve their communities of interest. Specifically, partners noted a lack of city, state, or federal-level health data detailing the demographics of the AA or NH/PI subgroup community members and clients they served. CBO partners understood that disaggregated health data could be used to justify need for expansion of services, to support community needs, and to tailor evidence-based programs and resources to support health care access and use of services. Partners also posited that robust data on health determinant topics used to supplement anecdotal stories from community members about the health experiences and key challenges would strengthen resource allocation requests.

From 2004–2006, NYU CSAAH co-developed and implemented Round 1 of the CHRNA in AA communities in NYC to capture and report on the unique sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviors, and outcomes of one of the fastest-growing racial/ethnic populations in NYC (16). In order to identify priority areas of interest for health survey question topics, CSAAH study team members first met internally, drawing lessons from our work with local AA community partners about ongoing health concerns and our knowledge of existing large-scale health survey questionnaires and instruments. CSAAH then arranged meetings with community partners to elicit input on topic areas of interest and to determine survey domains that would assess health factors and indicators. Community and study team partners chose a cross-sectional community needs and assets assessment survey to collect a comprehensive sample to reflect the immediate needs and local assets of NYC AA subgroups of interest. Eligibility included: self-reported Asian ancestry; 18 to 85 years of age; residing in the NYC metropolitan region; and the ability to speak and/or read English or a language spoken by subgroup of focus. Subgroups include: Cambodians (97), Chinese (205), Koreans (102), Japanese (112), South Asians (398), Thai (189), and Vietnamese (101). The largest South Asian ethnic subgroups included Pakistanis (89), Asian Indians (122), and Bangladeshis (158) (Table 1). A total of 1,201 participants completed the CHRNA. Findings underscored distinct experiences across subgroups (11).

Table 1:

Community Health Resources and Needs Assessment (CHRNA) Methodology and Survey Variables across Three Rounds

| Module / Topic Area | Round 1 (2003–2006) | Round 2 (2013–2016) | Round 3 (2020–2021) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | NYC | NYC | Phoenix, AZ, Atlanta, GA, and Salt Lake City, UT | |

| Primary subgroups represented/surveyed | Cambodian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, South Asian, Thai, Vietnamese | Arab, Bangladeshi, Burmese, Cambodian, Chinese, Filipino, Himalayan, Asian Indian, Indo-Caribbean, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Thai, Vietnamese | Arizona: Pacific Islander, Vietnamese Georgia: Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, Vietnamese Utah: Tongan, Samoan |

|

| Total sample size | 1,201 | 1,802 | AZ: 200 GA: 505 UT: 405 |

|

| Demographics | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | |

| Health | Health Status | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS |

| Health Care Access | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | |

| Complementary Alternative Medicine | Not asked | CSAAH-developed | CSAAH-developed | |

| Behaviors | Physical Activity | Not asked | BRFSS | BRFSS |

| Mental Health | PHQ-2 | PHQ-2 | PHQ-2, BRFSS | |

| Sleep | Not asked | BRFSS | BRFSS | |

| Food Security | Not asked | Household Food Security Scale; BRFSS | Household Food Security Scale; BRFSS | |

| Neighborhood | Not asked | Neighborhood Collective Efficacy | Neighborhood Collective Efficacy | |

| Religiosity | Not asked | Pew Research Center | Pew Research Center | |

| Communication | Not asked | HINTS | HINTS | |

| Discrimination | Not asked | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Everyday Discrimination Scale | |

| Tobacco | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | |

| Alcohol | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | BRFSS, NYC CHS | |

| Income | BRFSS | BRFSS | BRFSS | |

| COVID-19 and Testing | Not asked | Not asked | UAS, HRS | |

| Acculturation | Not asked | Not asked | Marin Acculturation Scale | |

BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CSAAH, Center for the Stud of Asian American Health; NYC CHS, New York City Community Health Survey; PHQ-2, Patient Health Questionnaire-2; HINTS, Health Information National Trends Survey; HRS, Health and Retirement Study; UAS, Understanding America Study

From 2013–2016, CSAAH implemented Round 2 of the CHRNA, which was informed by Round 1 and updated to reflect emerging community health concerns as well as growing subgroups, including Arab Americans, Burmese, Himalayans, Indonesians, Indo-Caribbeans, and Sri Lankans. Round 2 assessed population health improvements and health topics noted by community based organizations (CBOs), such as discrimination, neighborhood social cohesion, and sleep. A total 1,802 individuals completed the CHRNA. Targeted groups included: Arabs (118), Asian Indians (111), Bangladeshis (159), Burmese (48), Cambodians (100), Chinese (213), Filipinos (107), Himalayans (156), Indo-Caribbeans (105), Indonesians (73), Koreans (161), Japanese (103), Pakistanis (110), Sri Lankans (96), Thai (39), and Vietnamese (103). (Table 1). Distinct subgroup differences have been reported on (11).

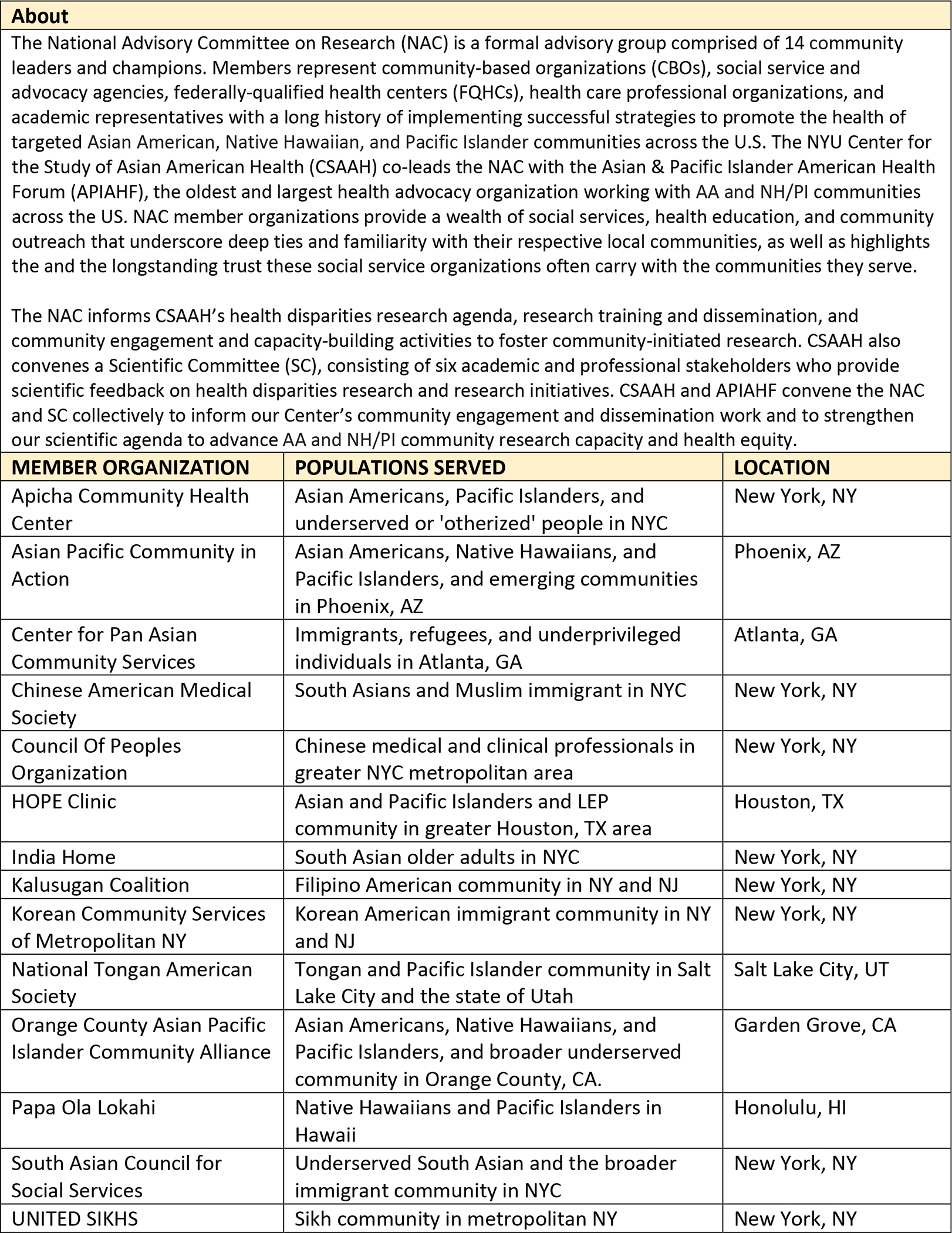

After Round 2 CHRNA, CSAAH convened our National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC), to further understand priority research topics, staff training needs, and preferred communication channels of AA and NH/PI communities across U.S. regions. The NAC is a formal advisory group comprised of 14 AA and NH/PI community leaders and champions representing CBOs, social service and advocacy agencies, federally-qualified health centers (FQHCs), health care professional organizations, and academic representatives with a long history of implementing successful strategies to promote the health and well-being of diverse AA and NH/PI communities (Figure 1). NAC CBO leaders noted significant disease burden or health disparity concerns within particular AA and NH/PI subgroup communities and described the need for meaningful data that could be used to enhance the health experience and health status of the AA and NH/PI groups they serve. Round 3 aimed to support community partners in gathering meaningful, disaggregated community health data on their own subgroups to support community programs, tailored community outreach, and CBOs’ health advocacy and policy endeavors, similar to Rounds 1 and 2 in NYC. Following an in-person feedback-gathering session and discussion with the NAC, CSAAH approached and invited three NAC CBO partner organizations, who noted a significant lack of available local or state data about their regional AA and NH/PI communities, had an established presence in these communities, and had high interest in participating in a methological community-engaged survey effort, to participate in leading local administration of CHRNA. CBO partners included: Center for Pan Asian Community Services (CPACS) in Atlanta, Georgia, Asian Pacific Community in Action (APCA) in Phoenix, Arizona, and National Tongan American Society (NTAS) in Salt Lake City, Utah (All community partners are detailed in Table 3).

Figure 1:

National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC) for CHRNA

Table 3:

CHRNA Community Partner Organizations, All Rounds

| Community-based organization | Primary AA, Arab American, or NH/PI community served and surveyed during CHRNA |

|---|---|

| Round 1 (all partners based in NYC metropolitan area) | |

| CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities | Asian immigrant and refugee (including Cambodian) |

| Chinese American Healthy Heart Coalition, Inc. | Chinese |

| Chinese American Medical Society (CAMS) | Chinese |

| Charles B. Wang Community Health Center | Chinese |

| Kalusugan Coalition | Filipino |

| Filipino American Human Services, Inc. | Filipino |

| Philippine American Friendship Committee-Community Development Center | Filipino |

| Damayan Migrant Workers Association | Filipino |

| Filipino Seniors Group of Elmhurst, NY | Filipino |

| LFP Productions, Inc. | Filipino |

| Coalition for Asian American Children and Families (CACF) | Filipino |

| NYU International Filipino Association | Filipino |

| Philippine Consulate General of New York | Filipino |

| Korean American Voters’ Council | Korean |

| Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (KCS) | Korean |

| Andolan | South Asian |

| Asian American Hepatitis B Program | South Asian |

| Jackson Heights Merchants Association | South Asian |

| Makki Masjid | South Asian |

| Morris Heights Health Center | South Asian |

| New York Taxi Workers Alliance | South Asian |

| Restaurant Opportunities Center of New York | South Asian |

| South Asian Council for Social Services (SACSS) | South Asian, Indo-Caribbean |

| South Asian Health Initiative | South Asian |

| IndoChina Sino-American Community Center | East and Southeast Asian (including Vietnamese) |

| Saint Nicholas of Tolentine Church (Bronx, NY) | Vietnamese |

| Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Astoria, NY) | Vietnamese |

| Our Lady of Perpetual Help (Brooklyn, NY) | Vietnamese |

| Tu Quynh Pharmacy | Vietnamese |

| New York Vietnamese American Community Association | Vietnamese |

| Nguoi Dep Magazine | Vietnamese |

| Vietnamese Community Health Initiative | Vietnamese |

| Round 2 (all partners based in NYC metropolitan area) | |

| Arab American Family Support Center | Arab, Bangladeshi, Asian Indian, Pakistani |

| Muslim American Society | Arab, South Asian (including Bangladeshi and Pakistani) |

| Islamic Center of North America | Arab, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Asian Indian |

| Muslims for Peace | Bangladeshi, Asian Indian, Pakistani, Arab |

| Bangladeshi-American Community Development and Youth Services | Bangladeshi, Asian Indian |

| Khan’s Tutorial | Bangladeshi |

| Chhaya CDC | Bangladeshi, Asian Indian |

| Jamaica Muslim Center | Bangladeshi |

| Chittagong Association of North America | Bangladeshi |

| Adhunika Foundation | Bangladeshi |

| Mekong NYC | Southeast Asian (including Cambodian, Vietnamese) |

| Chinese-American Planning Council (CPC) | Chinese |

| Chinese Christian Herald Crusades | Chinese |

| Chinatown YMCA | Chinese |

| Philippine Consulate General of New York | Filipino |

| UniPro—Pilipino American Unity for Progress, Inc. | Filipino |

| Kalusugan Coalition | Filipino |

| Adhikaar | Nepali-speaking community |

| Tibetan Dege Society of North American, Inc. | Himalayan |

| Mustang Kyidug, USA | Himalayan |

| United Sherpa Association, Inc (USA) | Himalayan |

| India Home | South Asian and Indo-Caribbean |

| Satya Narayan Mandir | Asian Indian, Pakistani |

| IDP USA | Asian Indian |

| South Asian Council for Social Services (SACSS) | Chinese, South Asian (including Asian Indian, Bangladeshi, and Pakistani), Indo-Caribbean |

| South Asians for Empowerment | South Asian |

| United Sikhs | Asian Indian |

| Indo-Caribbean Alliance, Inc. | Indo-Caribbean |

| Richmond Hill Economic Development Council (RHEDC) | Indo-Caribbean |

| Japanese American Social Services, Inc. (JASSI) | Japanese |

| JAANY (The Japanese American Association of New York) | Japanese |

| Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (KCS) | Korean |

| Council of People’s Organization (COPO) | South Asian and Muslim (including Pakistani) |

| Round 3 | |

| National Tongan American Society (NTAS) Salt Lake City, UT | Tongan, Samoan, Micronesian, Hawaiian |

| Asian Pacific Community in Action (APCA) Phoenix, AZ | Filipino, Vietnamese, Marshallese, Micronesian |

| Center for Pan Asian Community Services (CPACS) Atlanta, GA | Vietnamese, Chinese, Taiwanese, and Korean |

Drawing from our experience with previous Rounds, CSAAH offered each community partner one-on-one survey administration training, survey implementation and data analyses support, and overall technical and administrative oversight throughout the research process; this included sharing best practices to administer web-based surveys, as Round 3 was conducted primarily using REDcap, a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies (17, 18). CSAAH provided monetary support to regional partner organizations to further bolster survey administration and implementation in their metropolitan areas, given that it would not be feasible for CSAAH staff to provide on-the-ground tangible support outside of NYC. Each CBO developed a budget estimate, and funds were allocated to each partner based on their proposed estimates. Community partners were not given parameters on how to apply funds; however, CSAAH made suggestions for use, including purchase of survey participant incentives, funds to support community health worker (CHW) or staff time for recruitment or translated survey review, and funds for dissemination development. Community partners were excited to co-lead the needs assessment effort, which established a determined, cooperative dynamic between our teams. Follow-up phone or virtual conversations with partners established mutually determined project goals, identification of AA or NH/PI subgroup communities with whom to focus outreach, shared project timeline, and clarity on co-ownership and sharing of data.

Beginning in 2021, CSAAH began to support these CBOs in the administration of Round 3 of the CHRNA. Questions were added to assess COVID-19, transportation, food behaviors, and acculturation, while using up-to-date validated scales. As of December 31, 2021, 505 surveys were completed in Atlanta, GA (largely Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean), 200 surveys were completed in Phoenix, AZ (largely PI subgroups, Chinese, and Vietnamese), and 405 surveys were completed in Salt Lake City, UT (largely PI subgroups). Data analyses is ongoing.

Survey Adaptation

Prior to each round, the selection and adaptation of survey measures from existing, validated health information instruments was framed during discussions with community. In building survey instruments for Rounds 1 and 2, we strived to complement the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s (NYC DOHMH) Community Health Survey (CHS). Other large-scale health survey instruments reviewed include the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the Commonwealth Fund Health Quality Survey, the National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLASS), the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), and measures from the PhenX Toolkit, a web-based catalog of high-priority measures related to complex diseases and environmental exposures. To ensure community engagement in the survey design and approach, CSAAH presented partners with suggested question domains in follow-up meetings; partners shared feedback on question wording, module order and relevance, and length of questions to mutually agree on the final survey instrument design. Question topic areas by Round are presented in Table 1, and process steps are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Key Process Steps for Developing and Implementing the Community Health Resources and Needs Assessment with Community Partners

| Key Process Step & Summary Actions | Summary Actions from CHRNA Community-Engaged Process | Example Activities from CHRNA Rounds |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Community Priority Identification –Listen and elicit community priority topic areas; learn community capacity needs. | • CSAAH study team members led active listening sessions with CBO partners to identify priority areas and key populations. • CBO partners closely contributed to the development of the survey instrument in order to strengthen and tailor the instrument for community use. • Revisions included edits to question phrasing the inclusion or exclusion of questions based on relevancy to the local community subgroup. |

• The Project RICE coalition and the DREAM Coalition tailored questions to elicit smokeless tobacco use (e.g. paan, bidis) for South Asian and Himalayan communities. • Alcohol use was omitted for the Bangladeshi community due to partners’ feedback on the cultural inappropriateness for a largely Muslim community. • Emerging populations (e.g. Arabs, Indo-Caribbeans, Nepalese, and Himalayans) were prioritized by partners due to an overall lack of existing data. • Questions were updated and additional scales included with community partner feedback in Round 3 (2021-present). |

| Step 2: Design, Refine, and Tailor Community Survey – Collaboratively co-create survey tool; adapt for cultural and linguistic relevancy, including translation | • Once partners reached a consensus on survey instrument design, bilingual CSAAH staff, CBO partners, or community members translated and reviewed surveys for cultural and linguistic accuracy. | |

| Step 3: Build community capacity by providing survey training and supports – Provide community surveyor training, and follow community partners’ direction in identifying appropriate channels, venues, and events for survey implementation. | • CSAAH provided tangible support and technical assistance to community partners, in order to strengthen their capacity to lead survey administration. • Support included survey administration training, follow-up on community-based data collection, and help specific to data analysis and dissemination. |

• During Rounds 1 and 2, CSAAH staff and interns received survey administration training. During Round 3, the CSAAH study team trained community partners to lead survey administration in their local AA or NH/PI regional communities. • During all rounds, surveys were administered at CBO settings (e.g. informational settings), at cultural events (e.g. food, health, and street fairs), and community celebrations and events hosted by faith-based organizations. • During Round 2, CSAAH and community partners co-developed one-page recruitment flyers for each AA subgroup in NYC, summarizing project goals and key findings from Round 1. |

| Step 4: Dissemination of Results – Collaboratively identify how and where (format, venues) to share back findings to the community | • Community partners directed how to provide findings to the community with usable, actionable products; the importance of clear visuals and brief, key points in plain language format were emphasized by CBOs. • Community partners reviewed and translated community briefs to share at CBO offices, community events (e.g. as galas and anniversary celebrations), and for social media channels and the CSAAH website. |

• CSAAH and CBO partner staff presented CHRNA findings at invited seminars as well as regional and national symposia and conferences for Rounds 1 and 2 in order to promote community-engaged survey methods, to spotlight the health priorities of disaggregated AA subgroups, and highlight areas of further expansion. • Findings were disseminated to community audiences, and community briefs were distributed at co-hosted health events with CBO partners. • In Round 2, culturally-tailored “community briefs” with key takeaways and infographics were designed for low health literacy community members in order to emphasize community strengths and areas for growth. |

Convenience sampling methods helped to recruit underserved and hard-to-reach immigrant populations and to yield data for communities who have not been well-represented in local and regional data (19, 20). Community partners identified appropriate community- venue sites for outreach. CSAAH’s study team and community partners developed a thorough approach to engage community members at their place of work, including restaurants, grocery stores, and nail salons, an important strategy given that immigrant communities often work in service-sector jobs with long hours and may not have been reached at community events. Such efforts led to new partnerships and interventions based on identified needs. For example, Round 2 CHRNA data revealed disparities in oral health care-seeking behaviors and determinants of depression risk among AA groups in NYC (21, 22). Through new and existing partnerships with CBOs, CSAAH engaged the Chinese American community in NYC using in-person community-facing training tutorials led by CSAAH staff and CHWs, to promote oral health and hygiene practices.

Results: Lessons Learned

In order to carry out survey project goals, CSAAH’s study team, which includes staff, bilingual CHWs, and research interns, leveraged existing, multi-year relationships withpartners, including our extensive Community Partner Network (CPN) of local, NYC-based AA-serving CBOs, our U54 NAC, and Scientific Committee (SC), and conducted outreach to additional, relevant community groups. As Rounds 1 and 2 focused specifically on AA communities in the NYC metropolitan area, partners were exclusively from AA subgroup communities. Round 3 included a revised focus to include NH/PIs in non-NYC-based regions; CSAAH is working closely with partner organizations directly serving AA and NH/PI communities in those regions. Community groups engaged in varying levels of involvement across the CHRNA survey project period based on organizational and staff capacity; some partners contributed to initial topic area exploration, tool development, or survey administration in their communities, while others participated solely in survey administration. These lessons shine light on the process of conducting community-engaged research with under-represented and often-marginalized AA communities.

1). Asset-Based Approach to Community Engagement across Survey Process

Our asset-based approach to community engagement prioritized identification of existing strengths and opportunities inherent in the community to bolster programming. Community leaders guided survey tool development in order to inform their service work, advance their tailored programs and practice priorities, and meet the needs of the communities they serve. Simultaneously, we aimed to complement data being collected at city, state, or national levels by using similar survey instruments. Community partners used Round 1 and 2 findings to supplement the NYC DOHMH’s CHS data, by characterizing under-resourced and underrepresented groups to substantiate funding requests and advocate for community-focused policies and resource priorities. Additionally, community partners invited CSAAH to present findings to policymakers; for example, encouraging the expansion of mental health resources for the Korean American community (THRIVE Initiative) using Round 1 data (23).

CSAAH’s study team met with partners following survey collection to review findings. Initial data cleaning and analyses was led by CSAAH, and community partners’ feedback was gathered. Collaborative, community-engaged data analysis strengthened community partners’ trust in both CSAAH’s research data expertise and transparency in data sharing, while also providing a regular meeting space to cooperativelyy digest and parse interpretations of findings. This joint approach capitalized on community partners’ inherent familiarity and deep local knowledge of AA and NH/PI communities to craft recommendations or generate action items from the data; community-preferred dissemination products were shaped to report findings back to community members in meaningful, comprehensible formats (e.g., short formal reports, community presentations with visual formats to support those with low literacy levels, led by CSAAH or co-led with CBO partner staff). Regular meetings and occasional check-ins between meetings provided time to share ideas, socialize, and further build trust between community partners and our study team.

1.1). Tailoring Community Engagement Methods to the Local Community Context

Reciprocal, bidirectional community engagement was critical to sustaining strong community partnership and trust. We utilized an approach whereby CSAAH staff provided survey administration training and assistance in the field to CBO staff, and CBO staff and trusted community contacts administered the majority of surveys. Through this iterative process, the CSAAH study team gained many insights, implementing partner feedback to tailor and refine survey administration trainings and outreach methods in subsequent CHRNA rounds, as well as to other projects centered by partners’ preferences and local community context. For example, surveys were anonymous and confidential, and participation was voluntary. Participants received a small gift, such as an umbrella or water bottle, as a token of appreciation for completing the survey, based on guidance and decision-making from community partners. Community partners’ deep social and cultural ties and connections to understudied, “hard-to-reach” AA and NH/PI populations of interest facilitated access via trusted community venues, events, and communication channels, ensuring that underserved immigrant populations were reached. In Round 3, technical support was adapted, given that the COVID-19 pandemic had drastically reduced opportunities for in-person survey recruitment at cultural gatherings or community events. CSAAH staff inputted community-translated and reviewed survey text into REDCap using a multilingual survey feature to allow the survey to appear in a number of translated languages (24), and futher monitored survey data collection. CSAAH engaged in regular, bi-weekly calls with CBO partner leads to deliver updates on survey response progress, plan recruitment approaches, and overcome challenges while administering the CHRNA as a virtual survey; frequent interactions were extremely helpful in building rapport and further motivating and engaging CBO partners as co-researchers throughout the process.

1.2). Data Ownership/ Data Use Agreement

Early and ongoing discussions on data use were key to building trust with partners. CSAAH had open conversations with CBO partners regarding data ownership and how survey results could be used and shared back to communities of interest. During Rounds 1 and 2, preliminary discussions articulating co-ownership of data and format of findings (e.g., data file formats, dissemination reports) with community partners produced actionable and digestible products for use in surveyed communities. Drawing on lessons learned, this process was further developed in Round 3 using memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with community partners at the start of the collaboration which were jointly drafted, reviewed, and signed. MOUs outlined CSAAH and CBO responsibilities, detailed shared data ownership and access, and specified the synergistic process to develop dissemination products to meet preferred community communication needs and health topic interests. To promote transparency, MOUs are reviewed and revised regularly by community and research partners. For example, after reviewing the initial draft of the MOU, one CBO partner suggested the inclusion of a sentence to plainly state that they would have direct access to the shared REDCap database throughout data collection in order to monitor and download raw data, as well a cleaned dataset prepared by the CSAAH team after completion of survey collection. We subsequently included this statement in MOUs with all Round 3 CBO partners to ensure partners understood that they had the option to lead their own separate data review with local partners or research teams in addition to CSAAH’s direct data analysis support, based on their timeline or preference. Based on this, our team offered one-on-one REDCap training support to any CBO partner interested in exploring the database tool.

2). Supporting Community Partners’ Capacity-Building

During Rounds 1 and 2, CSAAH tailored support to community partners who expressed interest in survey implementation methods, data analyses, and dissemination in order to strengthen their organizational research capacity. Through leveraging of CSAAH trainings as well as tangible support, partners developed greater autonomy in carrying out community data collection, co-owning survey data, and co-developing summary reports to hone their programmatic and advocacy work and community research capacity, a direct strength of our engagement approach with our CBO partners. Between Round 1 and 2, CSAAH supported primary data collection efforts led by NYC Arab American community partners, as well as a tailored health and needs assessment for older South Asian community members led by India Home, a small partner organization serving older South Asians. Actively listening to community voices allows researchers to connect to emerging communities and create partnerships to build resources among community partners. CSAAH staff provided tailored survey administration trainings for CBO staff and CHWs to support survey recruitment, often at the behest of partners asking for trainings to hone specific skillsets that would strengthen their research capacity. For example, in Round 2, community partners asked for guidance to address in-person community survey administration barriers; CSAAH provided useful tips during an in-person training with CHWs, interns, and CBO staff on how to engage community members when asking sensitive questions, steps to cultivate trust, and strategies to aid motivational interviewing techniques. Similarly, partners interested in creating impactful health communications for community members with low health literacy were invited to attend dissemination trainings. In Round 3, CSAAH drew from past experiences to preemptively offer relevant trainings to AA and NH/PI community partner organizations and staff.

3). Regular and Ongoing Engagement throughout the Research Process

Meeting regularly and providing ongoing practical and technical support to partners was important to ensuring research aims and instruments continually aligned with community needs and CBO staff capacity. In Rounds 1 and 2, CSAAH had bi-weekly meetings with community partners on recruitment progress, data collection efforts, events for survey administration, practical support (e.g., recruitment flyers, ordering incentives), and technical assistance (e.g., survey training, outreach to newly identified community organizations). CSAAH staff and student interns monitored recruitment and data entry of completed surveys, adhering to IRB-approved survey instrument collection, storage, and data management guidelines. Maintaining direct face time encouraged active, direct dialogue between CSAAH and CBO staff to collaboratively achieve project tasks, such as ensuring CBO staff or volunteers received survey administration training in a digestible format, pivoting in the event of project or community delays, and verifying that logistical details, such as having sufficient incentives ordered for community events, were completed. Additionally, regular meetings allowed for community input and encouraged partners to share candidly when providing feedback on what processes were working well, by creating an open environment to share feedback and work through any disagreements through mutually respectful discussions, face-to-face in person or virtually. Feedback was elicited on how the research team might improve communications or strengthen cooperation throughout the project or beyond – an ideal method for maintaining a participatory and shared exchange of decision making between community and research teams.

3.1). Building New/Maintaining Relationships Beyond the Research Process

By working closely with key community partners well connected to CBO networks or community subgroups of interest, CSAAH directed outreach and guided where community surveys might be administered. Engaging community partners at all stages of the research process provided opportunities to build trust, creating partnerships beyond CHRNA. The Diabetes Research, Education, and Action for Minorities (DREAM) Coalition, a community-academic partnership led by CSAAH and NYC South Asian community groups, provides an example of such a partnership. DREAM was later solidified through formal funding whereby the coalition collectively implemented a community-informed and community-led CHW program among Bangladeshi with diabetes.

In addition to leveraging and strengthening existing relationships to form coalitions, CSAAH has also connected with local CBOs and settings to solidify new partnerships where there have been no existing prior relationships. For example, during Round 2, leaders from understudied NYC-based AA subgroups contacted CSAAH to express interest in collaborating and implementing community health needs assessments in their communities after hearing about our work through word-of-mouth. These introductions allowed us to replicate CHRNA processes in burgeoning Arab, Indonesian, Burmese, and Thai communities, with whom we otherwise would not have been able to engage in survey collection. It continues to be our goal to incorporate and invite community expert knowledge through formation of close partnerships with new groups to meet the needs of emerging and evolving communities.

Engagement with local students and volunteers with requisite language skills, and connections to local community groups or places of worship helped to engender community confidence for survey participation. Showing up to participate in events hosted by community partners and demonstrating reciprocity, such as purchasing tickets to CBOs’ fundraising galas or offering informational presentations or capacity-building trainings to community agencies, encouraged trust and sustained collaboration. Tailoring outreach to subsets of communities through CBOs and faith-based organizations (FBOs) identified survey recruitment opportunities that otherwise would not have existed, ensured that dissemination of survey findings reached the priority populations, and opened avenues to partnership in future interventions.

A few limitations should be noted. Due to staffing changes at partner organizations, we were unable to elicit valuable feedback or invite coauthorship from individuals who participated in Rounds 1 and 2, which limits our ability to fully detail community partner feedback on our process or its long-term impact. However, we actively invited feedback from our CBO partners during Round 3, building from our approach from previous rounds to successfully maintain high levels of engagement and partnership. Second, while many questions included on our survey instrument were taken from large population-based surveys which survey AAs (e.g., NYC CHS and BRFSS), our survey includes translated questions and scales which have not been validated among many of the regional AA and NH/PI subgroups we engaged, which limits the generalizability of our process and findings; we hope to validate these scales in future research. Third, by using convenience-based sampling, we are not able to generalize the data for each subgroup, although the data collected remains valuable, considering the lack of available data in many of our groups.

Conclusion

Community-based needs assessments are a crucial tool to complement existing local, regional, or national data in order to present a more comprehensive look at complex determinants of health in under-resourced and under-researched communities. Health and governmental leaders must expand efforts to connect with and establish trust with community-based leaders, not only to improve national and regional health data collection and reporting for resource allocation, but also to recognize and utilize existing community resources and their cultural capacity to support their communities. In addition, many community organizations have strong interest in partnering on health survey research, highlighting the value of building and sustaining community-led research efforts. Identifying health priorities and assets of underrepresented populations is crucial in achieving health equity.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank our U54 National Advisory Committee on Research (NAC) – Apicha Community Health Center, Asian Pacific Community in Action (APCA), Center for Pan Asian Community Services (CPACS), Chinese American Medical Society (CAMS), Council Of Peoples Organization (COPO), HOPE Clinic, India Home, Kalusugan Coalition, Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (KCS), National Tongan American Society (NTAS), Orange County Asian Pacific Islander Community Alliance (OCAPICA), Papa Ola Lōkahi, South Asian Council for Social Services (SACSS), and UNITED SIKHS – for their input in informing priority concern areas and continued guidance, partnership, and support of our community engagement and health disparities research efforts at the NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH). In particular, we are grateful to our three community-based partner organizations leading Round 3 CHRNA efforts: Layal Rabat at Asian Pacific Community in Action (APCA) in Phoenix, AZ; Jung Ha Kim, Alnory Gutlay, Heather Kawpunna, and Vivian Ching at Center for Pan Asian Community Services (CPACS) in Atlanta, GA; and O. Fahina Tavake-Pasi at the National Tongan American Society (NTAS) in Salt Lake City, UT.

CSAAH also thanks and acknowledges the multi-year support and collaboration from community partners in the New York City metropolitan area who supported Round 1 and 2 CHRNA efforts. Partners include, but were not limited to: Adhunika, the Arab American Association of New York, the Arab American Family Support Center of New York, Asian American Federation of New York, Chinese-American Planning Council (CPC), Chinatown YMCA, Coalition of Asian American Children & Families (CACF), Kalusugan Coalition, Korean Community Services of Metro New York, Inc. (KCS), INC, Mekong NYC, the Moroccan American House Association, New York Taxi Workers Alliance, Project CHARGE partners, South Asian Council for Social Services (SACSS), and UNITED SIKHS.

Funding:

This work was made possible through funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Award Number U54MD000538 and the National Cancer Institute grant number P30CA016087. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCI. All authors accept responsibility for this publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval: The New York University Langone Health Institutional Review Board approved data collection and analysis for this study.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Wong, Department of Population Health Section for Health Equity, NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Laura C. Wyatt, Department of Population Health Section for Health Equity, NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Yousra Yusuf, Department of Population Health Section for Health Equity, NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Layal Rabat, Asian Pacific Community in Action.

O. Fahina Tavake-Pasi, National Tongan American Society.

Heather Kawpunna, Center for Pan Asian Community Services.

Vivian Ching, Center for Pan Asian Community Services.

Chau Trinh-Shevrin, Department of Population Health Section for Health Equity, NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Simona C. Kwon, Department of Population Health Section for Health Equity, NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Islam NS, Khan S, Kwon S, Jang D, Ro M, Trinh-Shevrin C. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in Asian American populations: historical challenges and potential solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010; 21(4):1354–1381. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi SS, Kwon SC, Sacks R, Trinh-Shevrin C. Commentary: Persistence and Health-Related Consequences of the Model Minority Stereotype for Asian Americans. Ethn Dis. 2016; 26(1):133–138. doi: 10.18865/ed.26.1.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta MRG, et al. Prevalence of Diabetes by Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA. 2019; 322(24):2389–2398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islam NS, Wyatt LC, Kapadia SB, Rey MJ, Trinh-Shevrin C, Kwon SC. Diabetes and associated risk factors among Asian American subgroups in New York City. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36(1):e5. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McElfish PA, Purvis RS, Esquivel MK, et al. Diabetes Disparities and Promising Interventions to Address Diabetes in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Populations. Curr Diab Rep. 2019; 19(5):19. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1138-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hixson L, Hepler BB, Kim MO. The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population: 2010: U.S. Census BureauMay; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Census. Quick Facts New York City, New York. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/newyorkcitynewyork. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NYC Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs. A Demographic Snapshot: NYC’s Asian and Pacific Islander (API) Immigrant Population. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/immigrants/downloads/pdf/Fact-Sheet-NYCs-API-Immigrant-Population.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2021.

- 9.Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam NS, Nadkarni S, Park R, Kwon SC. Defining an integrative approach for health promotion and disease prevention: a population health equity framework. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015; 26(2 Suppl):146–163. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NYU Langone Health. Section for Health Equity Partnerships & Coalitions. 2022. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/population-health/divisions-sections-centers/health-behavior/section-health-equity/community-engagement-education/partnerships-coalitions Accessed March 2, 2022.

- 11.NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health. Community Health Reports & Research Briefs. 2021. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/population-health/divisions-sections-centers/health-behavior/section-health-equity/dissemination/community-health-reports-research-briefs Accessed September 15, 2021.

- 12.Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of Community EngagementJune 2011.

- 13.Key KD, Furr-Holden D, Lewis EY, et al. The Continuum of Community Engagement in Research: A Roadmap for Understanding and Assessing Progress. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2019; 13(4):427–434. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2019.0064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmot M Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005; 365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NYU Langone Health. Department of Population Health, Section for Health Equity. 2022. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/population-health/divisions-sections-centers/health-behavior/section-health-equity. Accessed March 2, 2022.

- 16.King L, Deng WD. Health Disparities among Asian New Yorkers: New York City Department of Health and Mental HygieneMarch 2018 Contract No: September 2, 2021.

- 17.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019; 95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stockdale SE, Tang L, Pudilo E, et al. Sampling and Recruiting Community-Based Programs Using Community-Partnered Participation Research. Health Promot Pract. 2016; 17(2):254–264. doi: 10.1177/1524839915605059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valerio MA, Rodriguez N, Winkler P, et al. Comparing two sampling methods to engage hard-to-reach communities in research priority setting. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016; 16(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0242-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misra S, Wyatt LC, Wong JA, et al. Determinants of Depression Risk among Three Asian American Subgroups in New York City. Ethn Dis. 2020; 30(4):553–562. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.4.553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung M, Kwon SC, Edens N, Northridge ME, Trinh-Shevrin C, Yi SS. Oral Health Care Receipt and Self-Rated Oral Health for Diverse Asian American Subgroups in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2017; 107(S1):S94–S96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.City of New York. Mayor de Blasio, First Lady McCray Release ThriveNYC: A Mental Health Roadmap for All. November 23, 2015. https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/873-15/mayor-de-blasio-first-lady-mccray-release-thrivenyc--mental-health-roadmap-all#/0. Accessed September 15, 2021.

- 24.Young A, Espinoza F, Dodds C, Rogers K, Giacoppo R. Adapting an Online Survey Platform to Permit Translanguaging. Field Methods. 2021; 33(4):388–404. doi:Artn 1525822x2199396610.1177/1525822x21993966 [Google Scholar]