Abstract

Sexual minority individuals assigned female at birth (SM-AFAB) are at increased risk for problematic alcohol use compared to heterosexual women. Despite evidence that drinking locations and companions play an important role in problematic alcohol use among heterosexuals, few studies have examined these social contexts of alcohol use among SM-AFAB. To address this gap, the current study examined two aspects of social contexts in which SM-AFAB drink (locations and companions). We utilized two waves of data (six-months between waves) from an analytic sample of 392 SM-AFAB ages 17-33 from a larger longitudinal study. The goals were: (1) to identify classes of SM-AFAB based on the contexts in which they drank; (2) to examine the associations between drinking contexts, minority stressors, and problematic alcohol use; and (3) to examine changes in drinking contexts over time. Using latent class analysis, we identified four classes based on drinking locations and companions (private settings, social settings, social and private settings, multiple settings). These classes did not differ in minority stress. Drinking in multiple settings was associated with more problematic alcohol use within the same timepoint and these differences were maintained six months later. However, drinking in multiple settings did not predict subsequent changes in problematic alcohol use when problematic alcohol use at the prior wave was controlled for. Based on these findings, SM-AFAB who drink in multiple settings may be an important subpopulation for interventions to target. Interventions could focus on teaching SM-AFAB strategies to limit alcohol consumption and/or minimize alcohol-related consequences.

Keywords: alcohol use, sexual minorities, minority stress, drinking contexts

Introduction

Sexual minorities (i.e., lesbian/gay, bisexual, other non-heterosexual individuals) experience higher rates of problematic alcohol use than heterosexuals (McCabe et al., 2009). This disparity is particularly pronounced for sexual minorities assigned female at birth1 (SM-AFAB; Kidd et al., 2019; Talley et al., 2014). For example, lesbian and bisexual women are, respectively, 2.2 and 2.1 times more likely to have experienced an alcohol use disorder in the past year compared to heterosexual women, while gay and bisexual men are 1.3 and 1.6 times more like to have experienced an alcohol use disorder in the past year compared to heterosexual men (Kerridge et al., 2017). A number of other studies have demonstrated similar disparities in binge drinking and alcohol consequences by sexual orientation (e.g., Fish, 2019; Fish & Baams, 2018; Kerr et al., 2015).

A sizeable number of studies have linked minority stress (i.e., the unique stressors experienced by sexual minorities as a result of the stigmatization of non-heterosexuality) with problematic alcohol use among SM-AFAB (Goldbach et al., 2014; Kidd et al., 2018; Meyer, 2003), and a small body of research has also implicated social factors, such as drinking norms (Condit et al., 2011; Litt et al., 2015). With few exceptions (Dworkin et al., 2018; Fairlie et al., 2018), research has neglected social contexts in which SM-AFAB drink (e.g., drinking locations and companions). As drinking context is a strong predictor of alcohol problems in heterosexual samples (e.g., Connor et al., 2014; Keough et al., 2015), research on contexts in which SM-AFAB drink is necessary to advance our understanding of problematic alcohol use in this population. The current study aimed to: (1) identify classes of SM-AFAB based on drinking context; (2) examine associations between drinking contexts, minority stressors, and problematic alcohol use; and (3) examine changes in drinking contexts over time.

Social Learning and Problematic Alcohol Use among SM-AFAB

In addition to minority stress theory, social learning theory has been proposed to help explain SM-AFAB’s increased risk for problematic alcohol use. Social learning theory posits that drinking contexts, including locations and companions, influence drinking behavior through modeling and peer norms (Condit et al., 2011; Litt et al., 2015). Alcohol-centric contexts (e.g., bars) have historically been used by sexual minorities to safely socialize with each other and to seek romantic partners (Green & Feinstein, 2012; Hughes & Eliason, 2002). This has been theorized to contribute to more normative perceptions of heavy alcohol consumption among sexual minorities (Green & Feinstein, 2012). For example, studies indicate that sexual minority women tend to spend more time at bars and parties (Trocki et al., 2005) and they drink more often at their own home, someone else’s home, and bars compared to heterosexual women (Hequembourg et al., 2020). Furthermore, bisexual women tend to consume more alcohol at bars and parties compared to heterosexual women (Trocki et al., 2005). However, among college students, Coulter and colleagues (2016) found that sexual minority women were less likely to drink at fraternity or sorority houses, off-campus parties, and bars/restaurants than heterosexual women, and there were no differences in the likelihood of drinking in residence halls, on-campus events, or in outdoor settings by sexual orientation. Therefore, although sexual minority women drank more frequently than heterosexual women, they were less likely to drink in several specific locations and they did not differ in likelihood of drinking in other locations (Coulter et al., 2016). Hequembourg and colleagues (2020) also found sexual orientation differences in drinking companions, with sexual minority women drinking with friends more frequently than heterosexual women; lesbian women drinking more frequently with romantic partners than bisexual or heterosexual women; and bisexual women drinking less frequently with family members and more frequently alone compared to lesbian and heterosexual women. While these studies provide somewhat mixed evidence regarding where sexual minority women tend to drink, they have rarely examined associations between social context of drinking and problematic alcohol use.

However, research on heterosexual samples has frequently examined associations between drinking locations and companions and problematic alcohol use and found that they are strongly associated. For instance, drinking with friends has been linked to greater alcohol consumption and consequences than drinking with family members (Clapp & Shillington, 2001; Connor et al., 2014). Drinking alone has consistently been linked to alcohol-related consequences (Gonzalez & Skewes, 2013; Keough et al., 2018). Additionally, people tend to consume more alcohol in public (e.g., bars, parties) than in private or intimate locations (e.g., at home or friend’s home; Kairouz et al., 2002; Kuntsche et al., 2005).

While researchers have typically examined drinking locations and companions as separate predictors of alcohol consumption, these variable-based approaches may obscure more complex associations between social contexts and drinking behavior (Fairlie et al., 2018). Using a person-centered approach (latent class analysis), Fairlie and colleagues (2018) identified five drinking context patterns among SM-AFAB based on drinking locations and companions: infrequent or non-drinkers; private contexts (drinking at a home with partners or friends); social contexts (drinking at parties and bars/restaurants with partners or friends); alone and social contexts (drinking alone and in social contexts); and multiple contexts (drinking in all contexts with all types of companions). SM-AFAB who drank in multiple contexts reported greater alcohol consumption and consequences (Fairlie et al., 2018). These results are consistent with studies of college students (Trim et al., 2011) and sexual minority men (Jones-Webb et al., 2013), which have also found that individuals who drink in multiple settings report drinking more heavily. Examining drinking locations together with companions allows us to classify and understand the complex social contexts in which people drink. Fairlie and colleagues’ (2018) findings highlight the utility of this approach by demonstrating that combinations of drinking locations and companions were associated with alcohol consumption, rather than locations or companions alone. Given that previous research has been predominately cross-sectional, an important next step is to examine the level of variability in drinking context over time and associations between changes in contexts and changes in problematic alcohol use. Such research may help to further our understanding of the directionality of these associations among SM-AFAB and thus to inform the development of future interventions for this high risk population.

Predictors of Drinking Contexts

Minority stress theory posits that unique stressors experienced by sexual minorities (e.g., discrimination, internalized stigma) contribute to their problematic alcohol use (Meyer, 2003). Numerous studies have provided support for this theory by linked minority stressors with alcohol use problems (e.g., Dyar et al., 2020; Kidd et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2016). Few studies have examined associations between minority stress, outness, and drinking contexts. In an exception, Fairlie and colleagues (2018) did not find significant associations between sexual minority victimization and internalized stigma or drinking contexts. However, they found that greater outness was associated with drinking in private settings. Although Fairlie and colleagues (2018) did not find significant associations between minority stress and class membership, previous studies have demonstrated that minority stress is associated with alcohol use and problems (Wilson et al., 2016). Therefore, we expected sexual minority victimization and internalized stigma to be associated with drinking in contexts that have been linked to greater alcohol use/problems (e.g., drinking in multiple settings or alone). Outness has been linked to greater involvement in the LGBT community (Feinstein et al., 2017), which may increase opportunities for social drinking with other sexual minorities. Therefore, outness may be associated with a higher likelihood of drinking in social settings (i.e., at parties/bars with partners or friends) or in private settings (i.e., at home with friends and partners), as found by Fairlie and colleagues (2018).

Current Study

The current study aims to advance our understanding of the contexts in which SM-AFAB drink and their associations with minority stress and problematic alcohol use. First, we conducted a latent class analysis (LCA) to identify classes of SM-AFAB based on where and with whom they drink. After identifying the latent classes, we examined their concurrent associations with demographics and minority stress and their concurrent and prospective associations with problematic alcohol use. Finally, we examined changes in latent class membership over time and associations between changes in latent class membership and problematic alcohol use in order to examine the directionality of associations between changes in drinking context and changes in problematic alcohol use. In sum, the current analyses extended the limited prior research in this area (Fairlie et al., 2018) by using longitudinal data to test the extent to which drinking contexts (and changes in drinking contexts) were associated with changes in problematic alcohol use over time. Furthermore, we also extended prior research by testing these associations in a diverse sample, with nearly three-quarters people of color and one-third gender minorities.

While LCA is an exploratory approach, we expected that our classes would be similar to those identified in previous studies (Fairlie et al., 2018; Jones-Webb et al., 2013): (1) drinking in multiple settings with multiple companions [multiple contexts]; (2) drinking with close others in private settings [private contexts]; (3) drinking at parties and bars with friends [social contexts]; and (4) drinking alone. Consistent with previous research (Fairlie et al., 2018; Jones-Webb et al., 2013), we hypothesized that drinking alone and in multiple contexts would be associated with more problematic alcohol use than drinking in private settings or in public settings. We hypothesized that experiencing more sexual minority victimization and internalized stigma would be associated with drinking in contexts linked to problematic alcohol use (e.g., alone, in multiple contexts). We expected that being more out would be associated with drinking in private settings or with drinking in public settings. Given the dearth of prior research on changes in drinking contexts, we considered analyses of changes in drinking contexts over time exploratory.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

We used data from an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of SGM-AFAB, referred to as FAB400. To achieve a multiple cohort, accelerated longitudinal design, SGM-AFAB from a prior cohort study of sexual and gender minorities (originally recruited in 2007) and a new cohort of SGM-AFAB were recruited in 2016-17 using venue-based recruitment (i.e., pride events, SGM community organizations, and high school/college groups) social media, and incentivized snowball sampling. At initial enrollment (2007 or 2016-17), participants were 16-20 years old, assigned female at birth, and either identified as a sexual or gender minority or reported same-sex attractions or sexual behavior. Participants completed assessments at six-month intervals and were paid $50 for each. Study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University. See Whitton et al. (2019) for details about study design.

The current study predominately used data from Waves 3 and 4, conducted 12- and 18-months after Wave 1, because drinking context was not assessed prior to Wave 3. One variable from Wave 5 (AUDIT scores) was also included to allow for the examination of some prospective associations. Retention rates for Waves 3 and 4 were 94.9% and 92.8%. Given the focus on drinking contexts, we excluded 96 individuals from the larger study (n = 488) who reported no alcohol use at Waves 3 and 4, resulting in an analytic sample of 392 SM-AFAB who reported drinking during Wave 3 and/or 4. See Table 1 for analytic sample demographics. The sample was predominately comprised of cisgender women (70.9%), with a sizeable subsample of gender minorities (29.1%). All gender minorities in the analytic sample were also sexual minorities. The sample was diverse in sexual identity and race/ethnicity (26.3% non-Latinx White). Participants were ages 17-33 at Wave 3.

Table 1.

Demographics of Analytic Sample (N = 392)

| Demographics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort | ||

| 2016 Cohort | 327 | 83.4% |

| 2007 Cohort | 65 | 16.6% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 103 | 26.3% |

| Black | 126 | 32.1% |

| Latinx | 100 | 25.5% |

| Other | 63 | 16.1% |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Cisgender Women | 278 | 70.9% |

| Transgender or Male | 36 | 9.2% |

| Genderqueer/Non-Binary | 78 | 19.9% |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| Lesbian | 89 | 22.7% |

| Bisexual | 130 | 33.2% |

| Queer | 70 | 17.9% |

| Pansexual | 77 | 19.6% |

| Other Sexual Identity | 26 | 6.6% |

| Alcohol Use by Wave | ||

| W3 and W4 | 326 | 83.2% |

| W3 only | 25 | 6.4% |

| W4 only | 41 | 10.5% |

| Age (M, SD) | 20.98 (3.55) | |

Measures

Drinking Context

Participants who reported consuming alcohol in the past six months were asked about the contexts in which they usually drank during this period. Items were adapted from previous research (Fairlie et al., 2018). Participants were asked, “Where do you usually drink?” and instructed to select all of the applicable response options (at home, at friends’ homes, in bars or clubs, in restaurants, and at parties). Participants were also asked, “Who do you usually drink with?” and instructed to select all of the applicable response options (alone, romantic/sexual partner, friends, parents, brother or sister, and other relatives). Parents, brother or sister, and other relatives were recoded into a single category (family). Responses were then recoded such that each response option was treated as a separate variable, with endorsement of the response option (e.g., “alone”) indicated by a score of 1 and non-endorsement by a score of 0.

SGM Victimization

Ten items assessed victimization (Mustanski et al., 2016). Participants were asked, “In the past six months, how many times [item] because you are or were thought to be gay, bisexual, or transgender?” Examples: “have you had an object thrown at you” and “have you been threatened with physical violence.” Items were rated from 0 (never) to 3 (three times or more) and averaged (α = .79). Higher scores indicate more frequent experiences of victimization.

Internalized Stigma

The 8-item “desire to be heterosexual” subscale of Puckett et al.’s (2017) validated measure of internalized stigma was used. Participants were asked to indicate how much they agreed with statements such as “Sometimes I think that if I were straight, I would probably be happier” and “Sometimes I feel ashamed of my sexual orientation.” Items were rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) and averaged (α = .86). Higher scores indicate higher internalized stigma.

Outness

Participants were asked, “How out are you to the people around you?” Response options included: not out to anyone (0), only out to a few select people (1), out to most people (2), and out to everyone (3). Instructions indicated that this question referred to their sexual orientation. Prior research has demonstrated that a single-item measure of outness has comparable construct and predictive validity relative to a multiple-item measure that asked about outness to specific groups of individuals (Wilkerson et al., 2016). Higher scores indicate higher outness.

Problematic Alcohol Use

The AUDIT (Saunders et al., 1993) assessed alcohol use and problems in the past six months. The AUDIT includes 10 items rated on different scales. For example, the item “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?” was rated from 0 (never) to 4 (4 or more times a week). Items also assess problems arising from alcohol use (e.g., “How often during the past 6 months have you found that you failed to do what was normally expected of your because of drinking?”). Responses were summed (α = .79-.80). Total scores ranged from 0 to 40 (α = .79-.80), with scores of 8-15 indicating moderate alcohol problems and 16+ indicating severe alcohol problems.

Analytic Plan

A total of 18 observations (2.3%) were missing from Waves 3 (5 missing observations) and 4 (13 missing observations). 374 participants completed assessments at both Waves 3 and 4 (95.4% of the analytic sample). Within completed assessments, less than 0.1% of data were missing. These missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood. Additionally, 25 participants reported alcohol use at Wave 3 but not Wave 4 and 41 reported alcohol use at Wave 4 but not Wave 3. These participants were included in analyses that utilized data from waves in which they reported drinking. In latent transition analyses, which use data from both waves, all participants who reported alcohol use at Wave 3 and/or 4 were included. To allow for their inclusion, we added a non-drinking class and participants who did not drink at one wave were assigned to this class for the wave during which they did not drink.

First, a latent class analysis (LCA) was performed in Mplus version 8 using Wave 3 data to identify classes of individuals who drank in similar contexts. Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), sample size-adjusted BIC, Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) likelihood ratio tests, parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio tests (BLRT), entropy, smallest class size, and class interpretability were used to select the appropriate number of classes (Dziak et al., 2014; Lo et al., 2001; Nylund et al., 2007; Tofighi & Enders, 2008). Lower BIC values indicate the preferred model, and a significant LMR or BLRT indicated a preference for the current model. We also considered size of the smallest class because small classes (n < 25) are less likely to replicate and indicate extraction of too many classes (Hipp & Bauer, 2006). Higher entropy values indicate greater distinguishability of latent classes and precision with which individuals are categorized into classes (Ramaswamy et al., 1993).

After number of classes was determined, associations between Wave 3 classes and demographics at Wave 3 (age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual identity), minority stress at Wave 3 (internalized stigma, victimization, outness), and problematic alcohol use at Waves 3 and 4 were examined using the modified Bolock-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) approach for continuous variables (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016) and the DCAT (distal categorical variable) approach for categorical variables (Lanza et al., 2013). These approaches are currently considered to be the preferred approaches for estimating associations between latent classes and continuous and categorical covariates in Mplus (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2019). For prospective associations, we examined Wave 3 class predicting Wave 4 problematic alcohol use in analyses in which Wave 3 problematic alcohol use was not controlled for (to test whether differences in problematic alcohol use at Wave 3 were maintained at Wave 4) and in which Wave 3 problematic alcohol use was controlled for (to examined social context predicting changes in problematic use from Waves 3 to 4).

Next, a latent transition analysis (LTA) was conducted using data from Waves 3 and 4 to examine stability and change in drinking contexts over time. We followed procedures established by Asparouhov and Muthen (2014). Prior to conducting the LTA, we needed to determine whether the classes were invariant over time (i.e., whether the same classes were present at Waves 3 and 4). To determine this, an unconstrained latent class model was independently estimated for Wave 4, with the same number of classes identified for Wave 3. Then, a constrained model was estimated, with probabilities of drinking in each context for each class held constant across Wave 3 and 4. BIC for the unconstrained and constrained LCA models were compared to determine whether classes were invariant across time. Next, the three step LTA estimation process was conducted. An additional class was manually added to each wave for the LTA. This class included individuals who did not drink during that wave (and thus had values of 0 for each context variable) so that participants who drank at one wave, but not the other, were included in the LTA. This was done by manually adding an extra class at each wave in the LTA for which the likelihood of drinking in each context was set at 0.

In order to test for prospective associations between drinking contexts and problematic alcohol use, we examined associations between changes in drinking contexts (from Wave 3 to 4) and subsequent changes in problematic alcohol use (at Wave 5). While we were not powered to examine associations between each specific transition (e.g., drinking in public setting to drinking in private settings) and problematic alcohol use, we conducted preliminary analyses by categorizing those specific transitions into a smaller number of transition groups based on their most likely class memberships at Waves 3 and 4: remaining the same class at both waves (4 classes), transitioning to a class with more drinking contexts (1 class), and transitioning to a class with fewer drinking contexts (1 class). Associations between transition group membership and problematic alcohol use at Wave 5 were then examined (first without controlling for problematic alcohol use at Wave 3 and then controlling for it).

Results

The sample reported a wide range of drinking behaviors at Wave 3, with 39.2% of the sample reporting drinking monthly or less, 39.8% drinking 2-4 times a month, 17.2% drinking 2-3 times a week, and 3.8% reporting drinking 4 or more times a week. Participants also varied in the typical quantity of alcohol they consumed: 46.6% reported drinking 1-2 drinks on a typical occasion, 35.6% reported 3-4 drinks, and 16.6% reported 5 or more drinks. The sample had an average AUDIT score of 4.97 (SD = 4.22). Participants endorsed drinking in a variety of locations and with various companions (Table 2). Participants most frequently endorsed drinking at friends’ homes (75.0% at Wave 3; 79.8% at Wave 4), followed by their own home (71.5%; 73.6%), parties (65.4%; 63.9%), bars/clubs (33.1%; 36.9%), and restaurants (24.1%; 27.0%). They most frequently endorsed drinking with friends, followed by romantic/sexual partners, family, and alone.

Table 2.

Drinking Settings and Partners

| Wave 3 Endorsement | Wave 4 Endorsement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Drinking Location | ||||

| Home | 246 | 71.5% | 259 | 73.6% |

| Friend's home | 258 | 75.0% | 281 | 79.8% |

| Bar/club | 114 | 33.1% | 130 | 36.9% |

| Restaurant | 83 | 24.1% | 95 | 27.0% |

| Party | 225 | 65.4% | 225 | 63.9% |

| Drinking Companions | ||||

| Alone | 99 | 28.8% | 104 | 29.5% |

| Romantic/sexual partner(s) | 185 | 53.8% | 187 | 53.1% |

| Friend(s) | 321 | 93.3% | 329 | 93.5% |

| Family | 149 | 43.3% | 155 | 44.0% |

Latent Class Analysis

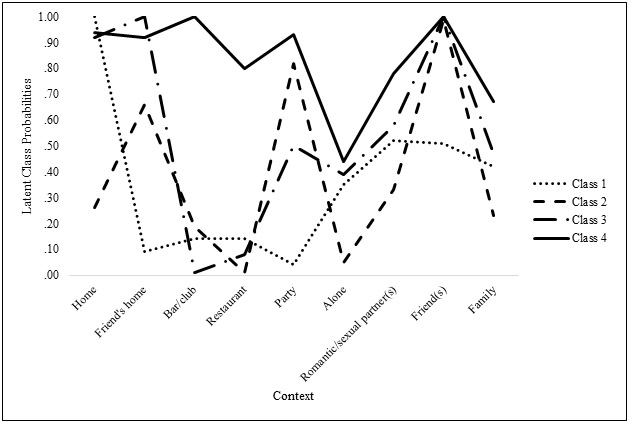

First, we conducted an LCA to identify classes based on drinking locations and companions at Wave 3. Fit indices suggested a five class model (Table 3). Adjusted BIC, BIC, and BLRT preferred five classes, while LMR preferred four classes. The fifth class extracted was very small (n = 13) and characterized by drinking alone (probability = 1.00) at home (probability = .83). Given the small size of this class, the four class solution was selected. Table 4 contains the probability of participants in each class drinking in each context and Figure 1 is a visual representation of those probabilities. Class 1 (drinking in private settings) contained 44 individuals (12.8% of drinkers) and was characterized by high probability of drinking at home, low probability of drinking in any other location, and moderate probabilities of drinking alone and with romantic/sexual partners, friends, or family. Class 2 (drinking in social settings) contained 115 individuals (33.4% of drinkers) and was characterized by high probabilities of drinking with friends, at friends’ homes, and at parties and low probabilities of drinking in other locations or with other companions. Class 3 (drinking in social and private settings) contained 100 individuals (29.1% of drinkers) and was characterized by high probabilities of drinking at home, at friends’ home, or with friends, moderate probabilities of drinking at parties, alone, with romantic/sexual partners, or with family members, and low probabilities of drinking in commercial drinking contexts (i.e., bars/clubs or restaurants). Class 4 (drinking in multiple settings) contained 85 individuals (24.7% of drinkers) and was characterized by a high probability of drinking in all locations and with all drinking companions and a moderate probability of drinking alone.

Table 3.

Latent Class Analysis Wave 3: Drinking Settings and Partners

| LMR-LRT | BLRT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classes | BIC | Adjusted BIC |

estimate | p | estimate | p | entropy |

| 1 | 3714.53 | 3685.98 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 3515.90 | 3455.62 | 252.96 | < .001 | 257.27 | < .001 | .81 |

| 3 | 3481.27 | 3389.27 | 91.70 | < .001 | 93.26 | < .001 | .79 |

| 4 | 3497.43 | 3373.71 | 41.76 | < .001 | 42.47 | < .001 | .79 |

| 5 | 3526.86 | 3371.42 | 28.72 | .05 | 29.21 | < .001 | .82 |

| 6 | 3564.95 | 3377.78 | 20.20 | .19 | 20.54 | .22 | .88 |

Lower BIC and adjusted BIC values indicate a better fitting model. Significant LMR and BLRT indicate a preference for the current model over the model with one less class. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; BLRT = bootstrapped likelihood ratio test.

Table 4.

Latent Class Probabilities: Wave 3

| Class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Location | ||||

| Home | 1.00 | .26 | .92 | .94 |

| Friend's home | .09 | .66 | 1.00 | .92 |

| Bar/club | .14 | .19 | .01 | 1.00 |

| Restaurant | .14 | .01 | .08 | .80 |

| Party | .04 | .82 | .50 | .93 |

| Drinking Companions | ||||

| Alone | .35 | .05 | .39 | .44 |

| Romantic/sexual partner(s) | .52 | .33 | .58 | .78 |

| Friend(s) | .51 | .99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family | .42 | .23 | .47 | .67 |

Probably of drinking context by latent class at Wave 3. Proportions greater than .50 are bolded. Class 1 (drinking in private settings) contained 44 individuals (12.8% of drinkers at wave 3); class 2 (drinking in social settings) contained 115 individuals (33.4% of drinkers at wave 3); class 3 (drinking in social and private settings) contained 100 individuals (29.1% of drinkers at wave 3); and class 4 (multiple contexts) contained 85 individuals (24.7% of drinkers at wave 3).

Figure 1.

Probability of drinking in each context by latent class at Wave 3. See Table 4 for the exact probabilities. Class 1 (drinking in private settings) contained 44 individuals (12.8% of drinkers at wave 3); class 2 (drinking in social settings) contained 115 individuals (33.4% of drinkers at wave 3); class 3 (drinking in social and private settings) contained 100 individuals (29.1% of drinkers at wave 3); and class 4 (multiple contexts) contained 85 individuals (24.7% of drinkers at wave 3).

Associations Between Latent Class and Covariates

Next, we examined whether there were differences between classes on demographics or minority stress. Classes did not differ on gender identity, outness, or minority stressors. Classes did differ by sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and age. Compared to individuals in the “drinking in multiple contexts” class (Table 5), those in the “drinking in social settings” and “drinking in social and private settings” classes were more likely to be under 21 years old. Compared to lesbian/gay participants, participants who identified with labels other than bisexual, pansexual, or queer were less likely be in the “drinking in private settings” or “drinking in social settings” classes compared to the “drinking in multiple settings” class. Compared to non-Latinx White participants, participants of color were more likely to be in the “drinking in private settings” class than the “drinking in multiple settings” class and Latinx participants were more likely to be in the “drinking in social settings” class than the “drinking in multiple settings” class.2

Table 5.

Associations with Drinking Location and Relationship to Drinking Companions Class Membership

| Private Settings |

Social Settings | Social and Private Settings |

Multiple Settings |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p |

| Age | ||||||||

| Under 21 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 21+ | .37 | .06 | .04 | < .001 | .04 | < .001 | ref | ref |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Black | 1.70 | < .001 | 1.02 | .98 | .43 | .63 | ref | ref |

| Latinx | 1.54 | < .001 | 2.67 | < .001 | .81 | .84 | ref | ref |

| Another Race/Ethnicity | 1.42 | .01 | 1.18 | .74 | .74 | .79 | ref | ref |

| Gender Identity | ||||||||

| Cisgender Woman | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Gender Minority | .76 | .58 | .84 | .67 | 1.65 | .17 | ref | ref |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||||

| Lesbian/Gay | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Bisexual | .47 | .60 | .92 | .93 | 1.06 | .94 | ref | ref |

| Pansexual | .77 | .62 | 2.55 | .09 | 3.19 | .11 | ref | ref |

| Queer | .26 | .47 | .46 | .61 | .69 | .73 | ref | ref |

| Another Identity | 1.66 | .04 | 1.27 | < .001 | .63 | .29 | ref | ref |

| Minority Stress | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | ||||

| Internalized Stigma | 1.58 (.08) | 1.67 (.07) | 1.56 (.06) | 1.67 (.06) | ||||

| Victimization | .18 (.07) | .12 (.03) | .17 (.03) | .12 (.02) | ||||

| Outness | 2.28 (.11) | 2.05 (.08) | 2.18 (.08) | 2.24 (.09) | ||||

| Distal Outcomes: M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | ||||

| Problematic Alcohol Use Wave 3 | 3.48 (.61)a | 4.51 (.37)a | 4.92 (.43)a,b | 6.42 (.60)b | ||||

| Problematic Alcohol Use Wave 4 | 3.35 (.67)a | 4.64 (.47)a,b | 4.96 (.46)a,b | 5.63 (.48)b | ||||

| Marginal Mean Prob Alc Use W4 | 3.62 (.65) | 4.59 (.34) | 4.62 (.31) | 5.63 (.48) | ||||

Note. Marginal mean problematic alcohol use at Wave 4 was calculated holding problematic alcohol use at Wave 3 at the sample mean. Superscript letters represent the results follow-up mean comparisons with corrections for multiple comparisons. Means with superscript letters that differ from one another indicate that the means differed significantly from one another. Variables included in this table were assessed at Wave 3 unless otherwise noted.

We then examined concurrent and prospective associations between class membership and problematic alcohol use (Table 5). Concurrently, participants in the “drinking in multiple settings” class reported more problematic alcohol use compared to those in the “drinking in private settings” and “drinking in social settings” classes. Prospectively, classes at Wave 3 also differed in their problematic alcohol use at Wave 4, with those in the “drinking in multiple settings” group continuing to report more problematic alcohol use than those in the “drinking in private settings” group. However, when Wave 3 problematic alcohol use was included as a covariate, there were no longer differences in problematic alcohol use at Wave 4 based on Wave 3 social context class. This indicates that differences in problematic alcohol use between the highest and lowest risk classes were maintained from Wave 3 to 4, but that class membership did not predict a change in problematic alcohol use from Wave 3 to 4.

Latent Transition Analysis

Next, we conducted an LTA to examine changes in class membership over time. Prior to the LTA, an LCA was conducted with Wave 4 data to determine if the same classes were present in Waves 3 and 4. A similar set of four classes was extracted, so we proceeded to test for measurement invariance. We compared BIC values for unconstrained (BIC = 7334.12) and constrained models (BIC = 7151.43). BIC values indicated measurement invariance across waves (i.e., classes represented the same drinking contexts at each wave). To allow the 66 individuals who reported alcohol use at one wave but not another to be included in these analyses, a non-drinking class was added to the four previously discussed classes at this stage. Participants who reported not drinking at one of the two waves were placed in this non-drinking class for the wave during which they reported no alcohol use. The transition probability matrix is presented in Table 6. Results indicate moderate stability, with 47-74% of individuals in each class at Wave 3 remaining in the same class at Wave 4. The “drinking in private settings” and “drinking in social settings” classes demonstrated more variability across waves than the “drinking in social and private settings” and “drinking in multiple settings” classes. Of those who drank at both waves, 25.7% moved to a class in which they drank in more contexts (e.g., from “drinking in social settings” to “drinking in multiple settings”) compared to 17.4% moving to classes in which they drank in fewer contexts. Additionally, participants in the “drinking in private settings” and “drinking in social settings” classes at Wave 3 were more likely to report no alcohol use at Wave 4 compared to those in the “drinking in multiple settings” class, and participants who reported not drinking at Wave 3 were less likely to transition to the “drinking in multiple settings” class than to any other classes.

Table 6.

Latent Transition Analysis: Patterns of Change in Drinking Contexts

| Wave 4 Class | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | Social | Social and Private |

Multiple Settings |

No drinking |

||

| Wave 3 Class | Private Settings | .49 | .08 | .15 | .14 | .13 |

| Social Settings | .03 | .63 | .13 | .11 | .09 | |

| Social and Private | .09 | .00 | .63 | .22 | .05 | |

| Multiple Settings | .06 | .04 | .12 | .74 | .04 | |

| No drinking | .23 | .56 | .18 | .02 | .00 | |

While we were not adequately powered to examine differences in problematic alcohol use based on specific transitions (e.g., transitioning from “drinking in private settings” to “drinking in social settings”), we were able to conduct preliminary analyses of differences across certain types of transitions. We created the following six classes based on class membership at Waves 3 and 4: in the “drinking in private settings” class at both waves, in the “drinking in social settings” class at both waves, in the “drinking in social and private settings” class at both waves, in the “drinking in multiple settings” at both waves, increasing contexts (i.e., moving from a class in which they drank in fewer contexts to one in which they drank in more contexts), and decreasing contexts (i.e., moving from a class in which they drank in more contexts to one in which they drank in fewer contexts).3 These six transition groups were compared on problematic alcohol use at Wave 5 when problematic alcohol use at Wave 3 was not controlled for and when it was included as a covariate. Results indicated that those who were in the “drinking in multiple settings” class at Waves 3 and 4 (M = 6.82, SE = .60) and those who moved to a class in which they drank in more contexts (M = 6.11, SE = .50) had higher problematic alcohol use at Wave 5 than those who were in the “drinking in private settings” class at both waves (M = 3.08, SE = 1.81). Problematic alcohol use did not differ significantly between any other groups. However, when problematic alcohol use at Wave 3 was controlled for, none of the groups differed significantly on Wave 5 problematic use. In sum, these findings suggest that individuals who were in the “drinking in multiple settings” class at both waves maintained higher problematic alcohol use over time compared to those in the “drinking in private settings” class at both waves. Additionally, increasing the number of contexts in which one drank was associated with higher problematic drinking than remaining in the class that tended to drink in the fewest contexts. However, trajectories of stability and change in social contexts of drinking did not predict subsequent changes in problematic alcohol use.

Discussion

The current study adds to a small but growing literature examining social contexts in which SM-AFAB drink and their associations with minority stress and problematic alcohol use. Further, as one of the first longitudinal studies of drinking contexts among SM-AFAB, we were able to examine changes in drinking contexts over time and prospective associations between drinking contexts and problematic alcohol use. Results indicate that concurrent problematic alcohol use differed among subgroups based on drinking locations and companions. However, drinking context did not prospectively predict changes in problematic alcohol use. Contrary to expectations, minority stress was not associated with drinking context. This indicates that risk factors derived from social learning theory (e.g., drinking contexts) may function independently from minority stressors. Future research should examine potential mechanisms through which drinking context may impact problematic alcohol use, including perceived peer norms and drinking motives, to further our understanding of the role of social learning in contributing to disparities in problematic alcohol use affecting SM-AFAB.

We identified four subgroups of SM-AFAB based on drinking contexts. These subgroups were similar to those from a previous study of SM-AFAB (Fairlie et al., 2018). Our first group tended to drink at home with various companions, which is similar to Fairlie’s private settings class. Our second group drank with friends at friends’ homes and parties. This is similar to Fairlie’s social drinking class with two exceptions: in their study, social drinkers were also likely to drink in bars/restaurants and with partners. Our third class drank in private and social settings (at home, friends’ homes, and parties with partners, friends, and family). This is similar to Fairlie’s alone/social class with some exceptions: Fairlie’s alone/social drinkers were also likely to drink at bars/restaurants and were more likely to drink alone. Our fourth class drank in all contexts with various companions, which is very similar to Fairlie’s multiple drinking contexts class. The similarity between Fairlie’s classes and those identified in this study indicates that these classes reflect meaningful subgroups of emerging and early adult SM-AFAB that are likely to be broadly generalizable across this portion of the sexual minority population.

When there were differences between our classes and Fairlie’s classes, the differences involved drinking in bars/restaurants and alone. Only individuals in the “drinking in multiple settings” group were likely to drink in bars/restaurants in our sample, whereas individuals in the social, alone/social, and multiple contexts classes were likely to drink in bars/restaurants in Fairlie’s study. Given that our sample had a wider age range, it also likely included a larger proportion of minors who could not legally drink in highly regulated contexts (e.g., bars/restaurants). In fact, in our study, participants who were 21 or older were more likely to be in the “drinking in multiple settings” group (which had a high probability of drinking in bars/restaurants) than the “drinking in social settings” or “drinking in social and private settings” groups (which had low probabilities of drinking in bars/restaurants). Moderate proportions (.35-.44) of individuals in three of our four groups endorsed drinking alone, suggesting that drinking alone was not a distinguishing factor. When we extracted one additional class, the fifth class was too small to examine (n=13) but individuals in this class were highly likely to drink alone. Given that drinking alone is a risk factor for problematic alcohol use (Gonzalez & Skewes, 2013; Keough et al., 2018), it will be important for future research with larger samples to examine drinking alone among SM-AFAB and determine whether this group grows in later adulthood.

We found that problematic alcohol use differed by drinking context. Specifically, those who drank in all contexts reported more concurrent problematic alcohol use than those in the “drinking in private settings” and “drinking in social settings” classes. This is consistent with evidence that drinking in more contexts is cross-sectionally associated with more hazardous drinking and alcohol problems (Bähler et al., 2014; Fairlie et al., 2018). This suggests that SM-AFAB who drink in multiple contexts may be an important subpopulation for interventions to target.

We extended previous research by examining prospective associations between drinking context and changes in problematic alcohol use. While drinking context did not predict changes in problematic alcohol use over the subsequent six months, differences in problematic alcohol use at Wave 3 were maintained at Wave 4. In other words, participants who drank in all contexts at Wave 3 continued to report more problematic alcohol use at Wave 4 (relative to those in the “drinking in private settings” class), despite the fact that 26% of those participants no longer drank in all contexts at Wave 4. This suggests that any potential effects of drinking context on problematic alcohol use may persist over time (in this case, six months) even if people no longer drink in the same contexts. However, being in the “drinking in multiple settings” class was not predictive of a pattern of increasingly problematic use but rather of stable levels of problematic use. This is somewhat surprising given the overall number of individuals who changed classes during this period and the diversity of the direction of those changes, with 25.7% of participants transitioning to a class where they drank in more contexts and 17.4% transitioning to a class in which they drank in fewer contexts.

A similar pattern of findings resulted from our preliminary analyses of changes in drinking contexts, with consistently drinking in multiple settings over a one-year period and increasing the number of contexts in which one drank being associated with more problematic alcohol use than consistently being in the “drinking in private settings” class. Notably, neither being in the “drinking in multiple settings” class nor increasing the number of contexts in which one drank was predictive of increases in problematic use across a one-year period, and as a result, our findings do not shed light on the directionality of the association between drinking contexts and problematic alcohol use. It is important to note that that we were not able to examine the associations between specific transitions (e.g., from “drinking in private settings” to “drinking in social settings”) and problematic alcohol use. Instead, we had to collapse participants who changed classes into two groups (increasing vs. decreasing contexts) in order to have adequate transition groups sizes for examination. Future research with larger samples should explore the associations between changes in social contexts of alcohol use and problematic use.

Consistent with Fairlie and colleagues (2018), minority stressors were not significantly associated with drinking contexts. Although minority stress is a risk factor for problematic alcohol use (e.g., Kidd et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2016), the lack of associations between minority stress and drinking contexts suggests that minority stress is unlikely to influence problematic alcohol use by impacting where and with whom SM-AFAB drink. Instead, as found elsewhere (Feinstein & Newcomb, 2016), minority stress likely influences alcohol use by contributing to coping motives for drinking. We also did not find a significant association between outness and drinking context. This is in contrast to Fairlie and colleagues (2018), who found higher outness was associated with higher likelihood of drinking in private/intimate contexts (i.e., at home with partners and friends) compared to drinking infrequently. However, all of our classes involved high probabilities of drinking in some contexts (in contrast to their drinking infrequently class). As such, outness may differentiate SGM who drink in private/intimate contexts from those who drink infrequently, but it may not differentiate SGM who drink in one context versus another.

Limitations

Findings should be considered in light of limitations. First, we were unable to examine associations with transitioning from one class to another due to the small numbers of individuals who made any specific transition. Future research with larger samples should examine predictors of changing contexts as this may inform future interventions for SM-AFAB. Second, we did not examine the genders and sexual orientations of participants’ drinking companions or perceived drinking norms, and as a result, did not test related hypotheses based on social learning theory. This is an important area for future research. Third, our sample was a convenience sample of SM-AFAB recruited predominately from SGM community events in Chicago and SGM-relevant social media and, thus, it remains unclear if our findings generalize to all sexual minorities. Specifically, the use of venue and social media based recruitment may have resulted in a sample that was more strongly connected to the SGM community and, as a result, may not be representative of the broader SGM population. Fourth, our data did not allow for the examination of event-level social contexts of use, which have the potential to provide more nuanced information about the effects of minority stressors on social contexts of alcohol use than long-term longitudinal studies. We look forward to future research using daily diary and ecological momentary assessment to examine event-level associations among these variables. Fifth, our drinking context variables were based on endorsing where and with whom they tended to drink and therefore did not take into account the frequency with which participants drank in those contexts or the quantity they consumed in each context. Future studies using more fine-grained drinking context variables may therefore identify more nuanced classes. Finally, we examined changes in drinking contexts and problematic alcohol use over a relatively brief period of time (6 months); future research should examine more long-term changes in these factors (Wilkerson et al., 2016).

Conclusions

The current study broadens our understanding of social contexts in which SM-AFAB drink. By largely replicating the four categories of drinking contexts and companions identified by Fairlie and colleagues’ (2018), our findings suggest that these categories may be meaningful and generalizable among young SM-AFAB. Importantly, the number of contexts in which SM-AFAB drink appears to be concurrently associated with problematic alcohol use and these differences are maintained over time despite changes in drinking context. Based on these findings, SM-AFAB who drink in multiple settings may be a particularly important subpopulation for interventions to target. Prior research has demonstrated that greater use of protective behavioral strategies, or strategies to limit alcohol consumption and/or to minimize alcohol-related consequences, is associated with less alcohol consumption and fewer alcohol-related consequences among SM-AFAB (Litt et al., 2013). Consistent with a harm reduction approach (Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2002), interventions could focus on teaching SM-AFAB about protective behavioral strategies, encouraging their use, and helping to problem-solve barriers to using them. For example, SM-AFAB who drink in multiple settings could be encouraged to limit the number of settings in which they drink or to limit how much they drink in each setting using a variety of protective behavioral strategies (e.g., drinking slowly, alternating alcoholic and nonalcoholic drinks, stopping drinking at a predetermined time). However, additional research is needed to understand why drinking in multiple settings is associated with more problematic alcohol use in order to better inform interventions to reduce problematic alcohol use among SM-AFAB. Research with sexual minority women has linked higher coping, social, and enhancement drinking motives (Dworkin et al., 2018) and perceived peer drinking norms with heavier alcohol use (Lee et al., 2016). If future research indicates that SM-AFAB who drink in multiple contexts are at higher risk for problematic drinking as a result of elevated drinking motives or perceptions of heavy drinking as normative among SM-AFAB, then interventions that also address these risk factors will be necessary.

Public Health Significance Statement.

Results indicate that four subgroups of sexual minority individuals assigned female at birth (including cisgender women, transgender men, and non-binary individuals) can be identified based on where and with whom they tend to drink: (1) drinking in private settings (i.e., at home alone and with friends, partners, and family); (2) drinking in social settings (i.e., with friends at their homes and parties); (3) drinking in social and private settings (i.e., at houses and parties alone and with friends, partners, and family); and (4) drinking in multiple contexts (i.e., at houses, parties, and bars/restaurants alone and with friends, partners, and family). Individuals who drank in more locations tended to experience more problematic alcohol use at the same time point and six months later. However, drinking context did not predict subsequent changes in problematic alcohol use. A critical next step will be to examine mechanisms underlying associations between drinking contexts and problematic use to inform future interventions to reduce problematic alcohol use among sexual minority individuals assigned female at birth.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank project staff and collaborators for their assistance with study design and data collection. We also thank FAB400 participants for their invaluable contributions to understanding the health of sexual and gender minority individuals.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD086170, PI: Sarah W. Whitton) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01DA046716, PI: Christina Dyar; K08DA045575, PI: Brian Feinstein). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

SM-AFAB includes cisgender women, transgender men, and non-binary individuals AFAB who are sexual minorities.

The cohort originally recruited in 2007 and that recruited in 2016-2017 differed on some demographics. Participants in the 2007 cohort were older at Wave 1 of the current study, more likely to be Black, more likely to identify as lesbian/gay, and less likely to identify as bisexual or queer than those in the 2016-2017 cohort, but they did not differ on gender identity. Participants in the 2007 cohort reported lower internalized stigma and higher outness than those in the 2016-17 cohort, but there were no significant differences in victimization, or problematic alcohol use. The majority of variables on which the two cohorts differed from one another were not associated with drinking contexts (i.e., sexual identity, outness, internalized stigma) and the groups did not differ on problematic alcohol use. Therefore, it was preferable to retain the 2007 cohort (and thus a larger sample size and wider age range for the analytic sample) than to exclude the 2007 cohort due these minor differences with the 2016-17 cohort.

Participants who reported no drinking at Wave 3 or 4 were excluded from these analyses as transitions from drinking in some contexts to drinking in other contexts were of central interest rather than beginning or ceasing alcohol use.

References

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2019). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes, 21(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bähler C, Dey M, Dermota P, Foster S, Gmel G, & Mohler-Kuo M (2014). Does drinking location matter? Profiles of risky single-occasion drinking by location and alcohol-related harm among young men. Frontiers in public health, 2, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z, & Vermunt JK (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, & Shillington AM (2001). Environmental predictors of heavy episodic drinking. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 27(2), 301–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit M, Kitaji K, Drabble L, & Trocki K (2011). Sexual Minority Women and Alcohol: Intersections between drinking, relational contexts, stress and coping. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv, 23(3), 351–375. 10.1080/10538720.2011.588930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J, Cousins K, Samaranayaka A, & Kypri K (2014). Situational and contextual factors that increase the risk of harm when students drink: Case–control and case-crossover investigation. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33(4), 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RW, Marzell M, Saltz R, Stall R, & Mair C (2016). Sexual-orientation differences in drinking patterns and use of drinking contexts among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin ER, Cadigan J, Hughes T, Lee C, & Kaysen D (2018). Sexual identity of drinking companions, drinking motives, and drinking behaviors among young sexual minority women: An analysis of daily data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(5), 540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Sarno EL, Newcomb ME, & Whitton SW (2020). Longitudinal associations between minority stress, internalizing symptoms, and substance use among sexual and gender minority individuals assigned female at birth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88, 389–401. 10.1037/ccp0000487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak JJ, Lanza ST, & Tan X (2014). Effect Size, Statistical Power and Sample Size Requirements for the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test in Latent Class Analysis. Struct Equ Modeling, 21(4), 534–552. 10.1080/10705511.2014.919819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie AM, Feinstein BA, Lee CM, & Kaysen D (2018). Subgroups of young sexual minority women based on drinking locations and companions and links with alcohol consequences, drinking motives, and LGBTQ-related constructs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(5), 741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Dyar C, & London B (2017). Are Outness and Community Involvement Risk or Protective Factors for Alcohol and Drug Abuse Among Sexual Minority Women? Archives of Sexual Behavior (46), 1141–1423. 10.1007/s10508-016-0790-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, & Newcomb ME (2016). The role of substance use motives in the associations between minority stressors and substance use problems among young men who have sex with men. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers, 3(3), 357–366. 10.1037/sgd0000185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN (2019). Sexual orientation-related disparities in high-intensity binge drinking: findings from a nationally representative sample. LGBT health, 6(5), 242–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, & Baams L (2018). Trends in alcohol-related disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from 2007 to 2015: Findings from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. LGBT health, 5(6), 359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, & Dunlap S (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, & Skewes MC (2013). Solitary heavy drinking, social relationships, and negative mood regulation in college drinkers. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(4), 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Green KE, & Feinstein BA (2012). Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: an update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(2), 265–278. 10.1037/a0025424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, Blayney JA, Bostwick W, & Van Ryzin M (2020). Concurrent daily alcohol and tobacco use among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Substance Use and Misuse, 55(1), 66–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp JR, & Bauer DJ (2006). Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychological Methods, 11(1), 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, & Eliason M (2002). Substance use and abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. Journal of Primary Prevention, 22(3), 263–298. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Smolenski D, Brady S, Wilkerson M, & Rosser BS (2013). Drinking settings, alcohol consumption, and sexual risk behavior among gay men. Addictive Behaviors, 38(3), 1824–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz S, Gliksman L, Demers A, & Adlaf EM (2002). For all these reasons, I do… drink: a multilevel analysis of contextual reasons for drinking among Canadian undergraduates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(5), 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough MT, O'Connor RM, Sherry SB, & Stewart SH (2015). Context counts: Solitary drinking explains the association between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough MT, O'Connor RM, & Stewart SH (2018). Solitary drinking is associated with specific alcohol problems in emerging adults. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D, Ding K, Burke A, & Ott-Walter K (2015). An alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use comparison of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual undergraduate women. Substance Use and Misuse, 50(3), 340–349. 10.3109/10826084.2014.980954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, & Hasin DS (2017). Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 170, 82–92. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd JD, Jackman KB, Wolff M, Veldhuis CB, & Hughes TL (2018). Risk and Protective Factors for Substance Use Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth: a Scoping Review. Current Addiction Reports, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd JD, Levin FR, Dolezal C, Hughes TL, & Bockting WO (2019). Understanding predictors of improvement in risky drinking in a US multi-site, longitudinal cohort study of transgender individuals: Implications for culturally-tailored prevention and treatment efforts. Addictive Behaviors, 96, 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, & Engels R (2005). Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(7), 841–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Tan X, & Bray BC (2013). Latent class analysis with distal outcomes: A flexible model-based approach. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 20(1), 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Blayney J, Rhew IC, Lewis MA, & Kaysen D (2016). College status, perceived drinking norms, and alcohol use among sexual minority women. Psychology of sexual orientation and gender diversity, 3(1), 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt DM, Lewis MA, Blayney JA, & Kaysen DL (2013). Protective behavioral strategies as a mediator of the generalized anxiety and alcohol use relationship among lesbian and bisexual women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(1), 168–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt DM, Lewis MA, Rhew IC, Hodge KA, & Kaysen DL (2015). Reciprocal relationships over time between descriptive norms and alcohol use in young adult sexual minority women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(4), 885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, & Rubin DB (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Witkiewitz K (2002). Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: Health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 27(6), 867–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, & Boyd CJ (2009). Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction, 104(8), 1333–1345. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Andrews R, & Puckett JA (2016). The effects of cumulative victimization on mental health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 106(3), 527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural equation modeling, 14(4), 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, DeSarbo WS, Reibstein DJ, & Robinson WT (1993). An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science, 12(1), 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, Hughes TL, Aranda F, Birkett M, & Marshal MP (2014). Exploring alcohol-use behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents: intersections with sex, age, and race/ethnicity. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, & Enders CK (2008). Identifying the correct number of classes in growth mixture models. In Hancock GR & Samuelsen KM (Eds.), Advances in latent variable mixture models (pp. 317–341). Information Age Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Trim RS, Clapp JD, Reed MB, Shillington A, & Thombs D (2011). Drinking plans and drinking outcomes: Examining young adults' weekend drinking behavior. Journal of Drug Education, 41(3), 253–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocki KF, Drabble L, & Midanik L (2005). Use of heavier drinking contexts among heterosexuals, homosexuals and bisexuals: results from a National Household Probability Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(1), 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Dyar C, Mustanski B, & Newcomb ME (2019). Intimate partner violence experiences of sexual and gender minority adolescents and young adults assigned female at birth. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(2), 232–249. 10.1177/0361684319838972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson JM, Noor SW, Galos DL, & Rosser BS (2016). Correlates of a single-item indicator versus a multi-item scale of outness about same-sex attraction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(5), 1269–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Gilmore AK, Rhew IC, Hodge KA, & Kaysen DL (2016). Minority stress is longitudinally associated with alcohol-related problems among sexual minority women. Addictive Behaviors, 61, 80–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]