Abstract

Children that experience neglect are at risk for maladaptive outcomes. One potential resource for these children is early childhood education (ECE), but there is currently limited evidence which is compounded by data limitations. This study used data from the National Study of Child and Adolescent Well-being II (N = 1,385) to compare children’s cognitive and social-emotional outcomes among children involved in child protective services that experienced either no care, informal care, or formal care, as well as moderation by type of neglect. Results suggest that ECE was related to increased cognitive and social skills and decreased behavior problems, depending on whether the child attended informal or formal care, with some associations being stronger for children that experienced neglect. These findings have implications for practitioners and policymakers in the intersection of ECE and child protective services.

Keywords: child protective services, early childhood education, neglect

Background

Approximately 3.1 million children were the subject of an investigation by child protective services (CPS) in 2020 in the U.S. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2022). Children involved in CPS experience worse academic outcomes and physical and social-emotional health compared with the general population (Casanueva et al., 2011). After a CPS investigation, cases are considered “substantiated” if there was sufficient evidence to indicate maltreatment and “unsubstantiated” if there was insufficient evidence. Despite experiencing maltreatment, 80% of children with substantiated cases remain in their homes (see exceptions in USDHHS, 2022). The most common type of maltreatment is neglect (i.e., a caregiver failing to provide adequate clothing, food, medical care, or supervision to a child; Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2019), which accounts for over 76% of substantiated reports of maltreatment (Sedlak et al., 2010; USDHHS, 2022). Children may have experienced multiple types of maltreatment and the next most common types are physical abuse (16.5%), sexual abuse (9.4%), other (6%; such as threatened abuse), and sex trafficking (0.2%; USDHHS, 2022).

Given that early childhood is an important time for skill development, these high rates of neglect are particularly troubling (Cunha et al., 2006). Prior research has illustrated that neglect is related to immediate and long-term maladaptive outcomes, such as lower academic achievement, higher risk of violence, and higher risk of mental health issues (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, personality disorders, suicidal ideation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety; Vanderminden et al., 2019; Widom, 2014). Child neglect victims are generally understudied (Proctor & Dubowitz, 2014) and there is little research on protective factors that promote well-being among young children who have experienced neglect. Therefore, it is important to understand resources that might promote child well-being among children who remain in home following neglectful parenting. According to ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1994), children are situated within different ecological contexts, and families and schools constitute the two most influential environments during early childhood. Among families involved in CPS, early childhood education (ECE) programs provide an alternate environment that can positively shape their development. The current study sought to understand whether a school-like environment could compensate for a home environment that warranted investigation by CPS. Given that substantiation does not differentiate children’s outcomes (Hussey et al., 2005), children whose parents were suspected of neglect may be as at risk as children whose parents were confirmed to have neglected them. Thus, this study considers children involved in both substantiated and unsubstantiated cases of maltreatment and it examined whether early childhood education (ECE) can promote positive developmental outcomes among young children who remain in-home after any type of CPS investigation and if ECE is particularly beneficial after experiencing neglect.

Neglect and Child Outcomes

Currently, there is some discrepancy in the definition of neglect and the number of subtypes of neglect (Jonson-Reid et al., 2012). Barnett and colleagues (1993) created the Maltreatment Classification Scheme based on CPS records and this measure details the frequency, chronicity, and type of maltreatment. This scheme was then modified by the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect to distinguish subtypes of neglect (English et al., 2005). Physical neglect, which is based on failure to provide (English et al., 2005), encompasses when the caregiver cannot or will not provide sufficient basic necessities, such as food, clothing, or shelter (Font & Berger, 2015; Proctor & Dubowitz, 2014). Supervisory neglect, based on lack of supervision (English et al., 2005), is when the caregiver does not ensure the child is adequately supervised at all times or when the environment is unsafe (similar to Font & Berger, 2015). Supervisory neglect includes instances of domestic violence, substance abuse, and criminality because each of these represent the child being exposed to an unsafe environment. Although both are classified as neglect, physical and supervisory subtypes differ in their etiology (Yang & Maguire-Jack, 2016), are only moderately correlated (Dubowitz et al., 2005), and fall into different latent profiles when using a person-centered approach (Kang et al., 2015). Given the relevance of both to children in CPS, the current study focused on both children who experienced either physical or supervisory neglect.

Children who have experienced neglect tend to have worse cognitive and social-emotional outcomes compared with non-maltreated children (Hilyard & Wolfe, 2002; Widom, 2014). Yet, there is little research on whether the two main types of neglect are differentially associated with children’s development. Because it is linked with a lack of material resources and with deprived environments, physical neglect may manifest in more cognitive deficits, as parents are not able to provide a nutritionally rich or stimulating environment. However, physical neglect may also be a marker of overall maladaptive family functioning, either by not meeting physical/mental health needs or poor sanitation, which then undermines social development (Dubowitz et al., 2005). Other researchers draw on attachment theory to explain the link between physical neglect and social-emotional outcomes, such that physical neglect represents a caregiver’s inability to fulfill children’s most foundational needs (i.e., food, clothing, shelter) and therefore results in children having an internal working model of not being able to effectively elicit care (Crittenden, 1992). Prior research has demonstrated that physical neglect seems to be more consistently associated with cognitive development (Font & Berger, 2015; Manly et al., 2013), but it has also been associated with worse social-emotional outcomes for children (English et al., 2005; Font & Berger, 2015; Hilyard & Wolfe, 2002; Vanderminden et al., 2019).

In contrast, supervisory neglect typically refers to situations in which the caregiver is not physically or emotionally available. This emotional and physical unavailability has been linked to insecure and disorganized attachments in infants because children are not able to reliably depend on their caregiver in situations of distress (Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002). Insecure and disorganized attachment styles have been linked to poor social-emotional outcomes, such as poor emotion regulation or more behavior problems (Sroufe, 2005). Prior research has found supervisory neglect to be associated with aggressive, anxious, depressed, and withdrawn behaviors, and unrelated to cognitive development compared with non-maltreated children (Font & Berger, 2015). Given this information, the current study also examined the associations between type of neglect and children’s outcomes.

Neglect and Early Care and Education

Given the negative links between neglect and children’s development, it would seem important to consider factors that may buffer vulnerable children from the harmful effects of neglect, including enrollment in ECE. As brief background, ECE encompasses any arrangement in which the child is supervised by a non-parental caregiver, which includes formal care, such as Head Start or other center-based care, and informal care, such as caregiving from a relative. There are an ample number of studies that have documented the positive effects of high quality ECE for children’s academic learning in the general population (e.g., Ansari & Winsler, 2013; Ansari & Winsler, 2014; Li et al., 2013; Vandell et al., 2010) and among higher risk populations (Magnuson et al., 2004; Votruba-Drzal et al., 2013; Watamura et al., 2011). In contrast, the evidence regarding the impacts of ECE for children’s socioemotional development is less clear (e.g., Phillips et al., 2017).

Although it is likely that the benefits of ECE would extend to children who experience maltreatment, there is very little research on the topic. This could be due to families who are involved in CPS might be less likely to engage in research, or because families involved in CPS have low participation rates in ECE with less than a third of children under 5 years old attending ECE (compared to approximately 50% of children not involved in CPS; Klein et al., 2016). Of the existing research on ECE among children involved in CPS, the focus has been on maltreatment generally and few studies have considered differences by neglect. One study found that enrollment in Head Start resulted in improvements in pre-academic skills and marginal improvements in behavior problems for children in non-parental care (Lipscomb et al., 2013). Another study on children from low-income households in Florida demonstrated that both CPS- and non-CPS-involved children who attended accredited ECE centers had higher language, cognitive, and fine motor skills than children in non-accredited ECE centers (Dinehart et al., 2012). A study on children involved in CPS in Minnesota found that children enrolled in a high quality ECE center showed improvements in language and social competence, but enrollment did not reduce disparities on academic or social-emotional outcomes between CPS and non-CPS involved children (Kovan et al., 2014). In a nationally representative sample of children involved in CPS, children enrolled in ECE had more optimal language development than children not enrolled in ECE and ECE was particularly beneficial among children who experienced supervisory neglect (Merrit & Klein, 2015). Although this prior work is important for understanding the potential benefits of ECE for children involved in CPS, many relied on samples from only one state, indirect assessments of out-of-home care, or only considered one developmental outcome. Overall, there is a growing literature on the benefits of ECE for children involved in CPS, but there remains a limited understanding of how ECE may influence multiple development outcomes and for children with a history of neglect.

One key feature of ECE is the type of care. Among the general population of children, center-based care, or formal care, is typically associated with better cognitive development than home-based care, or informal care (Ansari & Winsler, 2013; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network & Duncan, 2003). Importantly, this literature has found that ECE has a compensatory effect among children who experience lower quality home-environments (Miller et al., 2014; Watamura et al., 2011). But for children who experience neglect, it might be that any ECE, rather than the specific type of care, is related to more positive development because children are exposed to an environment that is likely more cognitively stimulating and that likely provides enriched supervision. Indeed, prior work has found that among children involved in CPS for both abuse and neglect, any involvement in ECE has been linked with improved language development (Merrit & Klein, 2015). Therefore, the current study focused on how enrollment in informal or formal (center-based) care was related to children’s cognitive and social-emotional outcomes compared with children not in care, but who were involved in CPS.

Finally, there has been some debate on the persistence of benefits from ECE. Prior literature has consistently documented short-term benefits of ECE, but there are mixed findings as to whether these benefits persist throughout elementary school or even into middle or high school (for review see Ansari, 2018). The persistence of benefits from ECE could be attributed to a “skill begets skill” argument, in which skills children learn in ECE provide a strong foundation for school entry and that allow them to build additional cognitive or social-emotional abilities (Cunha et al., 2006). On the other hand, Ansari (2018) argues that the lack of persistent benefits could be due to a convergence of skills through either “catchup”, in which children who did not experience ECE have faster learning during formal schooling, or “fadeout”, where children who did experience ECE do not demonstrate as many gains in formal schooling. Lastly, differences in the effects of ECE could be due to sleeper effects, which occurs when the benefits of ECE are not present immediately but rather appear later on (Ansari, 2018). Given the inconsistent literature on the persistence in the benefits of ECE for children’s development, the current study evaluated how participation in ECE baseline was related to children’s outcomes at two follow-up assessments, which occurred 18 months and 36 months later.

The Current Study

The negative effects of neglect on children’s development have been documented, and there is evidence that early childhood is a particularly vulnerable period for children’s later development. Thus, it is important to explore resources that might compensate for the effects of experiencing a neglectful household at a young age. One potential resource for children who experience maltreatment is ECE, but there is a lack of evidence of the protective benefits among children who are involved in CPS and children who may have experienced neglect. ECE could potentially be compensatory as it places children in stimulating environments with other young children and with caregivers experienced in caring for young children. Yet, the associations between ECE and children’s social-emotional and cognitive development might differ based whether the child experiences physical or supervisory neglect given the prior evidence that each affects outcomes differently. To date, there has not been a study that has investigated the effects of child care among children involved in CPS who remain in home, even though this makes up the majority of children that come into contact with CPS.

To address these gaps in the literature, the current study investigated two research questions: 1) How do different types of care (e.g., informal or formal) relate to cognitive and social-emotional well-being among children involved in CPS who remain in home?; and 2) How do these associations vary based on the type of neglect (e.g., physical neglect or supervisory neglect)? The first hypothesis was that children who experience formal care would demonstrate significant increases in cognitive and social skills and decreases in behavior problems compared to children not in care, whereas children who are in informal care would not be significantly different from children not in care. The second hypothesis that there would be a significant interaction between ECE and physical neglect when predicting cognitive outcomes, such that the participation in ECE would result in more gains in cognitive skills if children experience physical neglect compared to no participation in ECE. Also, it is expected that there would be a significant interaction between ECE and supervisory neglect, namely that children would experience a greater increase in social skills and a greater decrease in behavior problems when enrolled in care if they experience supervisory neglect compared to children who do not experience ECE.

Method

Data and Sample

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being II (NSCAW II) is a longitudinal and nationally representative sample of 5,872 children aged 0 to 17.5 years, who had CPS investigations closed between February 2008 and April 2009. NSCAW II oversampled infants and children in out-of-home care and under-sampled cases not receiving services to allow for further analysis of subgroups. Three waves of interviews are available, with the second and third waves of data collection occurring at 18 and 36 months after wave 1, respectively. This duration between assessments is similar to the first cohort of NSCAW that also had 18 months between each wave of complete data collection. NSCAW II collected information from children, parents, non-biological caregivers, and caseworkers.

The sample for the present study was limited to children who had a longitudinal sample weight, which was necessary to account for attrition and ensure that analyses were nationally representative (N = 4,232). The sample was also limited to children who were 4 years or younger at wave 1 to capture children who were of age to attend ECE (N = 2,491). The sample was further limited to children who remained home regardless of substantiation status (N = 1,405) because the aim of the current study was to explore the benefits of ECE among children involved in child protective services, not in addition to experiencing foster care. Based on the study design only families who were deemed “permanent” caregivers were asked questions about ECE, and thus, the final sample was 1,385 children. The sample was not further limited to substantiated cases (approximately 27% of the sample) because children who have been the subject of a CPS case are at risk for less optimal development regardless of substantiation status (Hussey et al., 2005). Table 1 includes weighted descriptive characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Weighted Sample Statistics

| Sample (n=1,385) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|

| ||||

| White | .38 | 0 | 1 | |

| Black | .25 | 0 | 1 | |

| Other race | .37 | 0 | 1 | |

| Child age (months) | 30.61 | 16.60 | 2 | 59 |

| Child male | .55 | 0 | 1 | |

| Sexual abuse | .04 | 0 | 1 | |

| Physical abuse | .19 | 0 | 1 | |

| Physical neglect | .42 | 0 | 1 | |

| Supervisory neglect | .80 | 0 | 1 | |

| Caregiver age (years) | 34.78 | 2.14 | 34 | 55 |

| Caregiver mental health | 2.53 | 1.21 | 1 | 6 |

| Caregiver married | .22 | 0 | 1 | |

| Number of kids | 2.33 | 1.27 | 1 | 5 |

| Caregiver in poverty | .92 | 0 | 1 | |

| Caregiver education | 1.96 | .70 | 1 | 3 |

| Caregiver employed | .40 | 0 | 1 | |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Measures

Type of care.

Type of ECE was reported on by caregivers at wave 1. Caregivers were asked, “In the last 12 months, have you received child care on a regular basis?” If caregivers responded affirmatively, they then reported on the type of care, such as Head Start or care provided by a relative. As part of these responses, caregivers could select multiple types of care. Based on the extant literature (e.g., Magnuson et al., 2004), these responses were coded as a mutually-exclusive, categorical variable to capture enrollment in: No care, informal care, and any exposure to formal care. Informal care included care provided by a relative, friend, or family. Formal care included any exposure to Head Start or center-based care.

Cognitive development.

Cognitive development was assessed at waves 1, 2, and 3 using several age-specific measures that were administered by research staff to children (see Table 2). For children under 4 years of age at wave 1 (n = 1,244), the Battelle Developmental Inventory 2nd edition was used to assess cognitive development (BDI; Newborg, 2005). In NSCAW, three cognitive domains were assessed, namely attention and memory, perception and concepts, and reasoning and academic skills. The total cognitive scale score for cognitive development was used for children under 4. The Preschool Language Scales-3 (PLS-3, Zimmerman et al., 1992) was another measure of cognitive outcomes, but this was asked of all children under 6 years old. The PLS-3 assesses language development and is composed of an auditory comprehension subscale and expressive communication subscale. The combined total Language score was used to measure children’s language skills. The PLS-3 had good internal consistency (α = .87) and high test-retest reliabilities (.91–.94).

Table 2.

Number of Child-Waves Included for Key Measures by Child Age at Baseline (Wave 1) Interview

| Indicator | Measures | Years of Age at Baseline Interview (N) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| <1Y (615) | 1Y (350) | 2Y (139) | 3Y (140) | 4Y (141) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Social-Emotional Health | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Social skills | Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliot, 1990; 3 years or older) | - | - | - | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 |

|

| ||||||

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (Sparrow, Carter, & Cicchetti, 1993) | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Behavior problems | Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorta, 2000; 18 months or older) | - | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 |

|

| ||||||

| Academic development | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cognitive Development | Battelle Developmental Inventory (BDI; Newborg, 2005; under 4 years old ) | 1,2 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | - |

|

| ||||||

| Language Development | Preschool Language Scales-3 (Zimmerman, Steiner, & Pond, 1992; 6 years and younger) | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 | 1, 2, 3 |

Social skills.

Social skills were assessed at waves 1, 2, and 3 (see Table 2). For children 3 years or older at wave 1 (n = 281), social skills were assessed with the Social Skills Rating System (α = .73–95; SSRS; Gresham & Elliot, 1990), which measures cooperation, assertion, responsibility, and self-control. In the SSRS, caregivers reported on how often children engaged in certain behaviors (e.g., follow instructions). The SSRS has high internal consistency in the NSCAW (α = .87-.90). In addition, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale screener was used to assess social skills for all ages based on caregiver-report (Sparrow et al., 1993). The Vineland Screener measures daily living skills and included 45-items which created two scales: Daily Living Skills and Socialization. The socialization scale included items on play, coping skills, and interpersonal relationships (α = .96).

Behavior problems.

Behavior problems were assessed at waves 1, 2, and 3 (see Table 2). The Child Behavior Checklist (α = .80–96; CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) was used to assess overall behavior problems for children 1.5 years and older at wave 1 (n = 500). As part of the CBCL, caregivers reported on whether children engaged in certain behaviors using a 3-point Likert scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). For children 1.5 to 5 years of age, there were 100 items, and for children 6 to 18 years, there are 113 items. The total behavior problems scale was used for both age groups.

Neglect subtypes.

The maltreatment allegations and risk assessment from the caseworker report and the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales (α = .66-.95; Straus et al., 1998) from the parent report were used to assess different types of child neglect at wave 1. Physical neglect included if the maltreatment allegation was physical neglect or educational neglect, if the family had trouble paying for basic necessities, and if the child was unable to get food or medical attention. Supervisory neglect included if the maltreatment allegation was lack of supervision, if the primary or secondary caregiver engaged in substance abuse, if the primary caregiver had serious mental health issues, if the primary caregiver had a recent history of arrests in the past year, and if the primary caregiver reported any instances of domestic violence in the home (either at the risk assessment or parent-report as the victim; see Font & Berger, 2015 for a similar operationalization). Two, separate dichotomous variables were created, one for physical neglect (0 = no, 1 = yes) and one for supervisory neglect (0 = no, 1 = yes). About 42% of the sample experienced physical neglect and about 80% experienced supervisory neglect. Approximately 33% of the sample experienced both physical and supervisory neglect. An appendix is available from the author for the precise items included in the scales.

Analytic Approach

All analyses were modeled within a regression framework in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén, & Muthén, 2015). To address missing data, full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used, and all analyses were weighted using the longitudinal sample weights provided in the data. The analyses include linear regression models with developmental outcomes regressed on types of care (informal or formal care, with no care being the reference group) at wave 1. All models controlled for the prior wave of the outcome of interest and each developmental outcome was estimated separately. Outcomes modeled at wave 2 control for assessments at wave 1 and outcomes modeled at wave 3 control for wave 2 assessments. Then, to assess whether the associations between type of care and children’s outcomes varied based on type of neglect, models with interaction terms between type of care and type of neglect were estimated. If an interaction term was significant, simple slopes analyses were conducted using the Model Constraint command in Mplus. Finally, because children were not randomly assigned to attend ECE, several covariates were included as covariates in the aforementioned models to reduce the possibility of spurious associations. Child-level covariates included child race/ethnicity (White, Black, Other race), age in months, sex (0 = female, 1 = male), and other types of abuse (dichotomous indicators of sexual abuse and physical abuse). Family level covariates included caregiver’s age, caregiver’s mental health (Short-Form Health Survey Mental Health Scale; Ware et al., 1996), caregiver’s marital status (0 = not married, 1 = married), number of children in household, caregiver’s employment status (0 = not employed, 1 = employed) and family poverty status (0 = not in poverty, 1 = in poverty). All covariates were derived from wave 1.

Results

ECE and Children’s Outcomes

The first set of analyses estimated the links between informal and formal care and the developmental outcomes among all children who remained in home following a CPS investigation regardless of maltreatment type (see Tables 3 and 4). For cognitive development among children 4 years or younger at wave 1, participation in informal care at wave 1 was associated with higher cognitive scores on the BDI at wave 2 compared with children who did not participate in any ECE (β = .16, p < .05). In contrast, participation in formal care did not predict children’s cognitive scores at wave 2. In terms of language development among the full sample, participation in any type of care (informal or formal) did not predict children’s language skills at wave 2 or 3.

Table 3.

Standardized Coefficients of Cognitive Outcomes Regressed on Type of Care at Wave 1

| Battelle Developmental Inventory (n = 1,244; Under 4 years old at wave 1) | Preschool Language Scales (n = 1,385; full sample) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 2 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | |

|

| |||||||||

| Type of care (referent = no care) | |||||||||

| Formal care | .05 | 1.46 | 2.06 | .05 | 2.57 | 2.16 | .02 | 1.19 | 3.71 |

| Informal care | .16 | 5.47 | 2.28 * | .04 | 2.76 | 4.07 | −.03 | −2.38 | 3.99 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Note. All models controlled for the outcome at the prior wave of assessment. All models controlled for child race, child age, child sex, sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, supervisory neglect, caregiver age, caregiver mental health, caregiver marital status, number of children in the home, caregiver poverty status, caregiver education level, and caregiver employment status.

Table 4.

Standardized Coefficients of Social Skills and Behavior Outcomes Regressed on Type of Care at Wave 1

| Social Skills (n = 281; 3 years or older at wave 1) | Social Skills (n = 1,385; full sample) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Type of care (referent = no care) | ||||||||||||

| Formal care | 0.06 | 2.15 | 2.65 | 0.13 | 4.38 | 2.21 * | 0.15 | 7.40 | 3.24 * | 0.02 | 0.82 | 2.41 |

| Informal care | 0.08 | 4.76 | 4.46 | 0.05 | 2.90 | 2.84 | 0.08 | 5.47 | 3.35 | −0.04 | −2.78 | 3.08 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Behavior Problems (n = 500; 18 months or older at wave 1) | ||||||||||||

| Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| β | B | SE | β | B | SE | |||||||

| Type of care (referent = no care) | ||||||||||||

| Formal care | −0.14 | −0.37 | 1.26 ** | −0.03 | −0.77 | 1.43 | ||||||

| Informal care | −0.10 | −4.01 | 1.69 * | −0.02 | −0.68 | 2.13 | ||||||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Note. All models controlled for the outcome at the prior wave of assessment. All outcomes were modeled separately. All models controlled for child race, child age, child sex, sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, supervisory neglect, caregiver age, caregiver mental health, caregiver marital status, number of kids, caregiver poverty status, caregiver education level, and caregiver employment status. First social skills assessment based on Social Skills Rating Scale, second assessment from Vineland Adaptive Socialization Scale. Behavior problems from CBCL.

In turning to children’s social skills among children 3 years or older at wave 1, participation in formal or informal care did not predict children’s social skills at wave 2 as measured by the SSRS. In contrast, children who were in formal care at wave 1 had significantly higher social skills at wave 3 than children who were not in care (β = .13, p < .05). Participation in formal care at wave 1 was also associated with higher social skills at wave 2 (but not wave 3) among the full sample based on the Vineland Adaptive Socialization Scale (β = .15, p < .05). These differences could be in part due to the sample size captured by the measures, in which the SSRS is for older children and the Vineland assessed the full sample. For behavior problems among children 18 months or older at wave 1, participation in informal (β = −.10, p < .05) and formal (β = −.14, p < .01) care at wave 1 was related to significantly lower behavior problems at wave 2, but not at wave 3, compared to no care.

Moderation by Physical or Supervisory Neglect

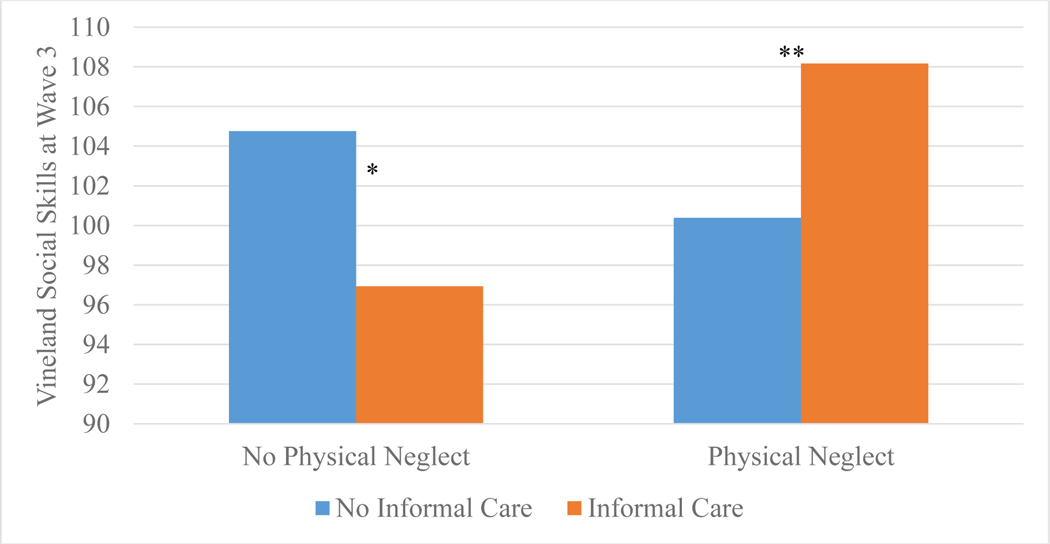

For all reported interactions, it should be noted that the comparison group is still other children involved in CPS. For example, when a comparison is made between children who experience physical neglect and children who do not experience physical neglect, the latter group still likely experienced some type of maltreatment even if their case was not substantiated (for discussion see Font & Maguire-Jack, 2019; Hussey et al., 2005; Kohl et al., 2009), just not physical neglect specifically. Among 10 tested interactions, 5 of them were significant. For physical neglect, there were several significant interactions when predicting children’s developmental outcomes. For children’s cognitive outcomes among children 4 years or younger at wave 1, there was a significant and positive interaction between formal care and physical neglect when predicting children’s cognitive score on the BDI at wave 2 (β = .38, p < .001). Among children who did not experience physical neglect, participation in formal care was related to lower cognitive scores at wave 2 compared with children not in formal care (see Figure 1). For children who did experience physical neglect, participation in formal care was related to higher cognitive scores at wave 2 compared to children who did not participate in formal care. For language development among the full sample, there was a significant and positive interaction between ECE and physical neglect when predicting language skills at wave 2 (β = .21, p < .01). Based on simple slopes analysis this effect was only significant for children who experienced physical neglect. Figure 2 illustrates that children who participated in formal care had higher language skills at wave 2 than children who did not participate in formal care among children who experienced physical neglect. Turning to the Vineland Adaptive Socialization Scale which included the full sample, there was a significant interaction between informal care at wave 1 and physical neglect when estimating social skills at wave 3 (β = .13, p < .01). Among children who did not experience physical neglect, participation in informal care was associated with lower social skills at wave 3 compared to children who were not in care (see Figure 3). For children who experienced physical neglect, participation in informal care was related to higher social skills at wave 3 compared to children who were not in care.

Figure 1.

Plotted Interaction Between Type of Care at wave 1 and Physical Neglect Predicting Battelle Developmental Total Cognitive Score at Wave 2

Figure 2.

Plotted interaction between type of care at wave 1 and physical neglect predicting language skills at wave 2

Figure 3.

Plotted interaction between type of care at wave 1 and physical neglect predicting Vineland social skills at wave 3

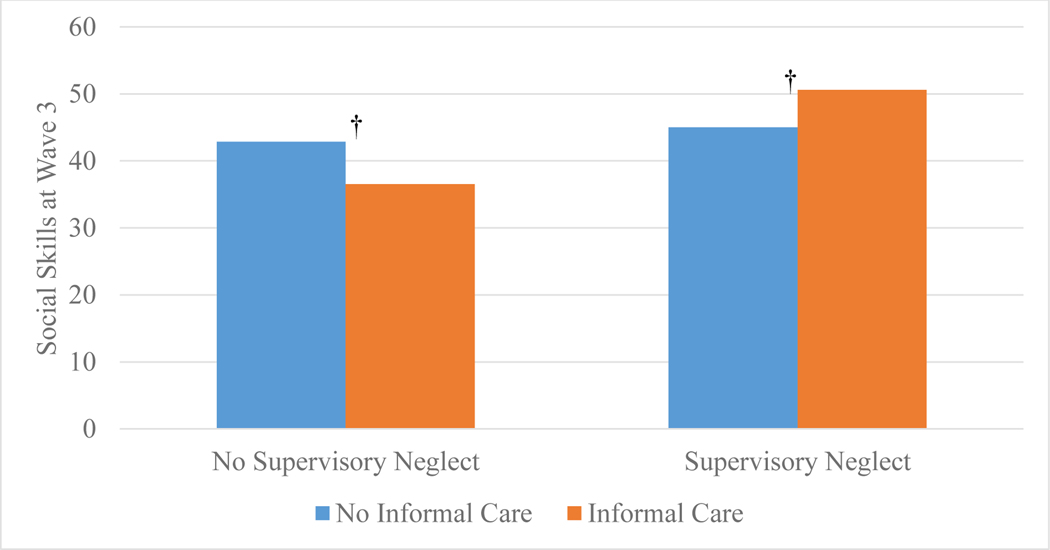

When estimating supervisory neglect, formal care interacted significantly with supervisory neglect when predicting children’s language skills at wave 3 (β = −.31, p < .01). Simple slopes analyses revealed that this effect was only significant for children who did not experience supervisory neglect (see Figure 4). Children enrolled in formal care demonstrated higher language skills at wave 3 than children who were not in care among children who did not experience supervisory neglect. Second, the interaction between informal care and supervisory neglect was significant and positive when predicting children’s social skills at wave 3 based on the SSRS (β = .19, p < .01). Among children who did not experience supervisory neglect, participation in informal care was associated with lower social skills compared to not participating in informal care. In contrast, participation in informal care was related to higher social skills among children who did experience supervisory neglect compared to children who were not in informal care. Yet, simple slopes analyses revealed these associations were only marginally significant (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Plotted interaction between type of care at wave 1 and supervisory neglect predicting language skills at wave 3

Figure 5.

Plotted interaction between type of care at wave 1 and supervisory neglect predicting SSRS social skills at wave 3

Discussion

This study examined the association between ECE participation and developmental outcomes among children who remained home after a CPS investigation. Currently, there is only limited evidence regarding the benefits of ECE for the academic and social-emotional development of children who are involved in CPS. This study extended prior work in several important ways. First, this study used a large sample of children involved in CPS who remain in-home, which constitutes the majority of cases for both substantiated and unsubstantiated reports of maltreatment. Further, this study modeled multiple domains of development and investigated variability in benefits of ECE by type of neglect.

Results demonstrated that participation in ECE was related to increases in cognitive outcomes and social skills as well as decreases in behavior problems, depending on the type of care and the timing of the outcome. These findings are partially supported by prior research that has linked ECE to gains in academic skills and social competence and marginal decreases in behavior problems among different samples of children who have had contact with CPS (Dinehart et al., 2012; Lipscomb et al., 2013). Interestingly, there were differences in the benefits in ECE depending on whether children were enrolled in informal or formal care, such that formal care seemed to be related to more optimal social-emotional outcomes (e.g., lower behavior problems and higher social skills) whereas informal care was tied to improvements in cognitive outcomes. This pattern of findings is in contrast to the broader literature on ECE, which has found cognitive gains and, in certain cases, less optimal social-emotional outcomes (e.g., more behavior problems) among participants in formal ECE (Ansari & Winsler, 2013; Li et al., 2013; Vandell et al., 2010). One potential explanation for this deviation is this study focused on children who are involved in CPS, which represents a much higher risk population than is included in most studies on ECE. For example, parents with substantiated investigations of maltreatment are much more likely to report clinical levels of dysfunctional parent-child interactions and higher levels of child difficulty compared to parents with children from low-income families enrolled in Head Start or in community child care centers (Curenton et al., 2009). Therefore, much of the previous work on the effects of ECE on child developmental outcomes might not generalize to children involved in CPS.

Turning to the current study’s results which demonstrated social-emotional benefits of formal care; providers in formal care settings have likely had training related to promoting positive social-emotional development among vulnerable families and might have more access to trauma-informed care trainings (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Lipscomb et al., 2019). Participation in formal care might also encourage developmentally-appropriate parenting practices through parent engagement and role modeling, which could support positive parent-child relationships at home (Klein et al., 2018). With regard to the link between informal care and cognitive outcomes, informal child care settings may provide more cognitively stimulating materials than are available at home among families involved in CPS (Klein et al., 2018). The lack of a significant association between formal care and cognitive outcomes is contrary to prior work in the general population and among children involved in CPS. One potential explanation is formal care arrangements are more likely to have larger class sizes (Sanders & Howes, 2012) and this higher child-to-teacher ratio might undermine cognitive benefits typically associated with formal care among children involved in CPS. Additional research is needed to understand the characteristics of different child care environments that are particularly beneficial among children involved in CPS. These results provide information for practitioners and policymakers, such that providing vouchers for formal care or support to find child care will likely promote positive outcomes for children among families who come into contact with CPS.

Another take-away from the current study is that the effect of ECE varied based on children’s experience of neglect. Among children who experienced physical neglect, participation in formal care was related to higher cognitive and language skills, whereas participation in informal care was associated with higher social skills compared to children not in care. Thus, ECE provides some compensatory effect for children who experience physical neglect even when compared to other children involved in CPS. This compensatory effect might be unique to the circumstances of physical neglect, which reflect deprivation in basic needs (e.g., food, clothing, shelter). In drawing connections to the broader ECE literature, these results are somewhat aligned with previous research on the compensatory benefits of ECE among socioeconomically disadvantaged families (Magnuson et al., 2004; Votruba-Drzal et al., 2013; Watamura et al., 2011). It might that formal care settings have more cognitively stimulating materials and activities that help compensate for low resource environments in cases of physical neglect (Magnuson et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2014; Watamura et al., 2011). If physical neglect is a proxy for overall household dysfunction (Dubowitz et al., 2005), then informal care (i.e., care from a relative, family, or friend) might provide children with an alternative sensitive and supportive environment to promote social-emotional development (Roditti, 2005). For children who experienced supervisory neglect, participation in informal or formal ECE did not provide compensatory effects. It may be that supervisory neglect is characterized by such a heterogenous set of behaviors (e.g., lack of supervision or caregiver substance abuse or exposure to domestic violence) that the benefits of child care are only apparent for certain situations. One other study explored the effect of ECE based on maltreatment type and found that ECE was particularly beneficial for language skills among children that experienced supervisory neglect (Merrit & Klein, 2015). Thus, the current study expanded upon this literature by illustrating that ECE supports multiple domains of development following experiences of physical neglect.

Another finding of note was that the majority of benefits from participation in ECE at wave 1 were found at outcomes at the second wave of assessment (which is 18 months on average after initial assessment) compared to outcomes at the third wave (which is 36 months on average after initial assessment). This is in line with prior research that has found a “fadeout” effect of ECE on children’s developmental outcomes, in which ECE interventions result in an immediate positive effect on children’s outcomes but this effect fades over time (Ansari, 2018; Bailey et al., 2016). It might be that there needs to be sustained engagement with high-quality care or schooling environments in order to maintain any cognitive or social-emotional gains similar to the general populations (Ansari, 2018); this may be especially important for children involved in child protective services. There was also one example of sleeper effects, in which exposure to formal care when children were 3–4 years old was related to higher social skills 36 months later. Sleeper effects are not well understood in relation to ECE, but it could be that exposure to ECE at 3–4 years compared to 1–2 years provides a greater focus on social skills that are beneficial later on in childhood. The current study is one of the first to examine the effect of ECE on developmental outcomes over time among children who remain home after a CPS investigation. Future research should continue to explore the mechanisms underlying the benefits of ECE among children involved in CPS and could examine how the benefits of ECE vary based on in-home or out-of-home placement.

Several limitations need to be taken into consideration when evaluating these findings. First, this study evaluated the type of care children received, but this might not be representative of the quality of care and again this is due to a limitation in the data. It is generally accepted that formal or center-based care is often higher quality than informal care arrangements, but there could be variation within each of these settings which could potentially contribute to the lack of large persisting benefits of ECE. Yet, it is important to consider the significant lack of data that takes into account both experiences of ECE and contact with CPS. NSCAW is one of the only data sources that provides this information with a large enough sample for analyses. To address this limitation, future data collection efforts need to include detailed information on both children’s experiences in ECE, as well as contact with CPS. Second, social-emotional outcomes were based on caregiver-reports and may be subject to bias especially if these caregivers are engaging in physical or supervisory neglect. This is a limitation of the dataset and future research should consider assessing child outcomes from multiple reporters. Third, this study was limited to children who remained in home following a CPS investigation and had to be limited to “permanent” homes because only permanent caregivers were asked about child care. Although the majority of children remain in home following a CPS investigation, the effects of ECE might be different for children placed in kinship or foster care. The current study was focused on in-home families because the aim was to understand if ECE could compensate in any way for a likely experience of maltreatment generally and subtypes of neglect, rather than if ECE could compensate for the experience of removal. The sample limitation to permanent homes was necessary due to the nature of the data, and few cases were lost after limiting to in-home placements. Ideally, future research would be able to explore the effects of ECE among a nationally representative sample of children who remained in-home following a CPS investigation and among children that experienced removal. Fourth, although analyses were longitudinal and controlled for a wide range of covariates, this study cannot make claims of causality. Future research could consider either an intervention approach or causal modeling techniques to try to assess the effect of ECE on developmental outcomes among children involved in CPS. Fifth, moderation analyses made comparisons between children who experienced different types of neglect to those who did not, however this sample was exclusively children who were involved in CPS. In other words, the comparison group that did not experience neglect may still experience another type of maltreatment, even if their case was not substantiated. These results cannot speak to the benefits of ECE when comparing children who experienced neglect to children who had no involvement in CPS. Currently, there does not exist a large, longitudinal dataset that includes a sample of children not involved in CPS and children involved in CPS that also collects information on ECE experiences. Future studies should include samples of children involved in CPS and children not involved in CPS in order to explore the benefits of ECE among these two populations.

Many children come into contact with CPS each year and remain in-home regardless of whether the reports were substantiated. These children are at risk for poor developmental outcomes and deserve attention aimed at promoting positive development. This study provides evidence that both informal and formal care may foster benefits for children’s cognitive and social-emotional development when they remain home following a CPS investigation. Further, ECE seems particularly beneficial after exposure to neglectful environments. These results should encourage practitioners to provide ECE vouchers or provide support in obtaining ECE to families who come into contact with CPS. This could include educating families, social workers, and foster agencies on the benefits of ECE for children involved in CPS and on how to access ECE (Klein, 2016). Additionally, these findings should motivate policymakers to generate policies to provide affordable and high-quality ECE to vulnerable families for the aim of promoting positive child outcomes. Finally, interagency collaboration between CPS and Early Childhood Systems can promote ECE engagement among families involved in CPS.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support of grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32 HD007081-35, PI: R. Kelly Raley; T32 HD049302, PI: Deborah Ehrenthal).

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A. (2018). The persistence of preschool effects from early childhood through adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110, 952–973. 10.1037/edu0000255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A, & Winsler A. (2013). Stability and sequence of center-based and family childcare: Links with low-income children’s school readiness. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 358–366. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.11.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A, & Winsler A. (2014). Montessori Public School Pre-K Programs and the School Readiness of Low-Income Black and Latino Children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 1066–1079. 10.1037/a0036799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D, Duncan GJ, Odgers CL, & Yu W. (2017). Persistence and fadeout in the impacts of child and adolescent interventions. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10, 7–39. 10.1080/19345747.2016.1232459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, & Cicchetti D. (1993). Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In Cicchetti D. & Toth SL (Eds.), Child Abuse, Child Development, and Social Policy (pp. 7–74). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Bromer J, & Korfmacher J. (2017). Providing high-quality support services to home-based child care: A conceptual model and literature review. Early Education and Development, 28(6), 745–772. 10.1080/10409289.2016.1256720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. Readings on the Development of Children, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Casanueva C, Ringeisen H, Wilson E, Smith K, & Dolan M. (2011). NSCAW II baseline report: Child well-being. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/resource/nscaw-ii-baseline-report-child-well-being-final-report [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). Definitions of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM (1992). Children’s strategies for coping with adverse home environments: An interpretation using attachment theory. Child Abuse & Neglect, 16(3), 329–343. 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90043-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha F, Heckman JJ, Lochner L, & Masterov DV (2006). Interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 697–812. 10.1016/S1574-0692(06)01012-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinehart LH, Manfra L, Katz LF, & Hartman SC (2012). Associations between center-based care accreditation status and the early educational outcomes of children in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 1072–1080. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Pitts SC, Litrownik AJ, Cox CE, Runyan D, & Black MM (2005). Defining child neglect based on child protective services data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 493–511. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Bangdiwala SI, & Runyan DK (2005). The dimensions of maltreatment: Introduction. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 441–460. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font SA, & Berger LM (2015). Child maltreatment and children’s developmental trajectories in early to middle childhood. Child Development, 86, 536–556. 10.1111/cdev.12322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font S, & Maguire-Jack K. (2019). The organizational context of substantiation in child protective services cases. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–22. 10.1177/0886260519834996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, & Elliott SN (1990). Social skills rating system: Manual. American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Hildyard KL, & Wolfe DA (2002). Child neglect: Developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26, 679–695. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00341-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, & Kotch JB (2005). Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 479–492. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, & Zhou P. (2013). Neglect subtypes, race, and poverty: Individual, family, and service characteristics. Child Maltreatment, 18, 30–41. 10.1177/1077559512462452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Bae HO, & Fuller T. (2015). Rereporting to child protective services among initial neglect subtypes. Families in Society, 96(3), 185–194. 10.1606/1044-3894.2015.96.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S. (2016). Benefits of Early Care and Education for Children in the Child Welfare System. A Research-to-Practice Brief. OPRE Report 2016–68. US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Merritt DH, & Snyder SM (2016). Child welfare supervised children’s participation in center-based early care and education. Children and Youth Services Review, 68, 80–91. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.06.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Mihalec-Adkins B, Benson S, & Lee SY (2018). The benefits of early care and education for child welfare-involved children: Perspectives from the field. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 454–464. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B. (2009). Time to leave substantiation behind: Findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreatment, 14, 17–26. 10.1177/1077559508326030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovan N, Mishra S, Susman-Stillman A, Piescher KN, & LaLiberte T. (2014). Differences in the early care and education needs of young children involved in child protection. Children and Youth Services Review, 46, 139–145. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.07.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Farkas G, Duncan GJ, Burchinal MR, & Vandell DL (2013). Timing of high-quality child care and cognitive, language, and preacademic development. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1440–1451. 10.1037/a0030613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Pratt ME, Schmitt SA, Pears KC, & Kim HK (2013). School readiness in children living in non-parental care: Impacts of Head Start. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34, 28–37. 10.1016/j.appdev.2012.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Hatfield B, Lewis H, Goka-Dubose E, & Fisher PA (2019). Strengthening children’s roots of resilience: Trauma-responsive early learning. Children and Youth Services Review, 107, 104510. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Oshri A, Lynch M, Herzog M, & Wortel S. (2013). Child neglect and the development of externalizing behavior problems: Associations with maternal drug dependence and neighborhood crime. Child Maltreatment, 18, 17–29. 10.1177/1077559512464119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EB, Farkas G, Vandell DL, & Duncan GJ (2014). Do the effects of head start vary by parental preacademic stimulation?. Child Development, 85, 1385–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt DH, & Klein S. (2015). Do early care and education services improve language development for maltreated children? Evidence from a national child welfare sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 185–196. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén B. (2015). Mplus. The Comprehensive Modelling Program for Applied Researchers: User’s Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Newborg J. (2005). Battelle developmental inventory (2nd ed.). Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2002). Early child care and children’s development prior to school entry: Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. American Educational Research Journal, 39, 133–164. 10.3102/00028312039001133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, & Duncan GJ (2003). Modeling the impacts of child care quality on children’s preschool cognitive development. Child Development, 74, 1454–1475. 10.1111/1467-8624.00617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D, Lipsey MW, Dodge KA, Haskins R, Bassok D, Burchinal MR, Duncan GJ, Dynarski M, Magnuson KA, & Weiland C. (2017). Puzzling it out: The current state of scientific knowledge on pre-kindergarten effects; a consensus statement. In Dodge KA (Ed.), Issues in pre-kindergarten programs and policy (pp. 19–30). The Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor LJ, & Dubowitz H. (2014). Child neglect: Challenges and controversies. In Korbin JE & Krugman RD (Eds.), Handbook of child maltreatment (pp. 27–61). Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders K, & Howes C. (2012). Child care for young children. In Saracho ON, & Spodek B. (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of young children (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, and Li S. (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Carter AS, & Cicchetti DV (1993). Vineland Screener: Overview, Reliability, Validity, Administration and Scoring. Yale University Child Study Center; New Haven, CT, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7, 349–367. 10.1080/14616730500365928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D. (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 249–270. 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health US & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2022). Child Maltreatment 2022.https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/cm2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL, Belsky J, Burchinal M, Steinberg L, & Vandergrift N. (2010). Do effects of early child care extend to age 15 years? Results from the NICHD study of early child care and youth development. Child Development, 81, 737–756. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01431.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderminden J, Hamby S, David-Ferdon C, Kacha-Ochana A, Merrick M, Simon TR, Finkelhor D. & Turner H. (2019). Rates of neglect in a national sample: Child and family characteristics and psychological impact. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 256–265. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votruba-Drzal E, Coley RL, Koury AS, & Miller P. (2013). Center-based child care and cognitive skills development: Importance of timing and household resources. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 821. 10.1037/a0032951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, & Keller SD (1996). A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watamura SE, Phillips DA, Morrissey TW, McCartney K, & Bub K. (2011). Double jeopardy: Poorer social-emotional outcomes for children in the NICHD SECCYD experiencing home and child-care environments that confer risk. Child Development, 82, 48–65. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (2014). Long-term Consequences of Child Maltreatment. In Korbin JE, & Krugman RD (Eds.), Handbook of child maltreatment (pp. 225–247). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Yang MY, & Maguire-Jack K. (2016). Predictors of basic needs and supervisory neglect: Evidence from the Illinois Families Study. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 20–26. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman IL, Steiner VG, & Pond RE (1992). Preschool language scale, third edition (PLS-3). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]