Abstract

Plasmid-free strains of Enterococcus faecalis secrete a peptide sex pheromone, cAD1, which specifically induces a mating response by donors carrying the hemolysin plasmid pAD1 or related elements. A determinant on the E. faecalis OG1X chromosome has been found to encode a 46.5-kDa protein that plays an important role in the production of the extracellular cAD1. Wild-type E. faecalis OG1X cells harboring a plasmid chimera carrying the determinant exhibited an eightfold enhanced production of cAD1, and plasmid-free cells carrying a mutated chromosomal determinant secreted undetectable or very low amounts of the pheromone. The production of other pheromones such as cPD1, cOB1, and cCF10 was also influenced, although there was no effect on the pheromone cAM373. The determinant, designated eep (for enhanced expression of pheromone), did not include the sequence of the pheromone. Its deduced product (Eep) contains apparent membrane-spanning sequences; conceivably it is involved in processing a pheromone precursor structure or in some way regulates expression or secretion.

Enterococcus faecalis is an opportunistic human pathogen commonly harboring mobile genetic elements conferring resistant to multiple antibiotics including vancomycin (8). A significant percentage of clinical isolates are hemolytic, a trait commonly encoded on plasmids resembling the hemolysin/bacteriocin (cytolysin)-encoding element pAD1 (28, 31). The pAD1 hemolysin has been shown to contribute to virulence in animal models (7, 30, 33) and has been found to be a lantibiotic consisting of two components (27).

pAD1 (14) is highly conjugative and encodes a response to the octapeptide sex pheromone cAD1 (37) secreted by plasmid-free recipients. The pheromone-induced mating response results in synthesis of a plasmid-encoded surface protein (25, 26) designated aggregation substance (Asa1). The asa1-encoded protein plays an important role in initiating contact with potential recipients upon random collision. Plasmid-free strains of E. faecalis actually secrete multiple sex pheromones, each specific for a particular group of conjugative plasmids (17, 18), and production of only the related sex pheromone gets shut down upon plasmid entry. For recent reviews of sex of enterococcal sex pheromone, see references 9 to 11, 20, and 49.

When a given plasmid is acquired by the recipient, the corresponding pheromone becomes shut down and/or masked by the production of a plasmid-encoded peptide that is secreted and competitively inhibits any tendency of the cells to be induced by endogenously secreted pheromone (29). In the case of pAD1, the inhibitor is called iAD1 and represents the last eight residues (carboxyl terminal) of a plasmid-encoded 22-amino-acid precursor resembling a lone signal sequence (11, 13, 36). Reduction of cAD1 involves the plasmid-encoded TraB, an apparent membrane protein (1a). Interestingly, the degree of shutdown can differ significantly depending on the bacterial host. For example, in strain OG1X/pAD1, pheromone (cAD1) is expressed at 2% of that produced by plasmid free OG1X, whereas in the nonisogenic FA2-2/pAD1, expression of cAD1 is reduced by only 50% (38). In both cases, the production of iAD1 masks all cAD1 activity present in culture supernatants. It is noteworthy that expression of cAD1 is significantly (about eightfold) greater in the case of plasmid-free OG1X compared to FA2-2 (48). In both hosts, the production of cAD1 is increased about 8- to 16-fold under anaerobic conditions, a behavior that does not occur in the case of other pheromones tested (e.g., cPD1, cCF10, and cAM373) (reference 48 and unpublished observations).

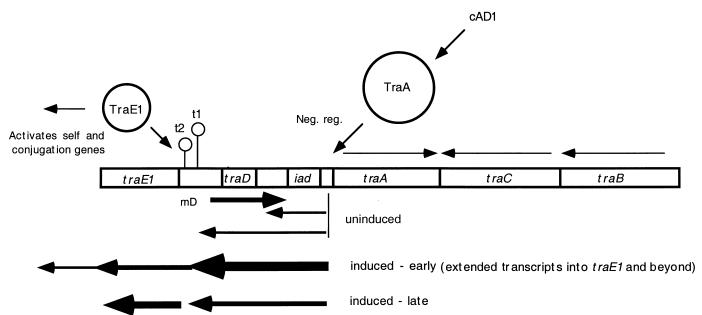

As illustrated in Fig. 1, regulation of the pAD1 mating response involves the binding of imported cAD1 to the plasmid-encoded, negatively regulating TraA protein, causing the latter to release its binding to pAD1 DNA and facilitating expression of the positive regulator TraE1 (23, 24, 40, 44, 47). The mechanism by which TraA regulates TraE1 expression involves the control of readthrough of a pair of transcription terminators, t1 and t2, just upstream of traE1 (24, 41, 44); a small RNA transcript, mD, encoded upstream of t1 also negatively regulates transcriptional readthrough (3, 4).

FIG. 1.

Map of the pAD1 regulatory region with features relating to control of the pheromone response. Regulation is geared to controlling transcriptional readthrough of the two transcription terminator sites t1 and t2 from the iad promoter. The pheromone (cAD1) is imported into the cell via a host-encoded uptake system, a process aided by the plasmid-encoded surface protein TraC. The negatively regulating (neg. reg.) TraA binds directly to cAD1, which results in an upregulation of transcription from the iad promoter, some of which passes through the terminators to ultimately generate TraE1. The transcript mD is present at high levels in the uninduced state and plays a significant role in preventing transcriptional readthrough of t1; it becomes greatly reduced upon induction. The traB product is involved in shutdown of endogenous cAD1 in plasmid-containing cells. traC encodes a surface protein that binds to exogenous pheromone (43). Arrows below the map indicate relative degrees of transcription in various regions; horizontal arrows above the map represent orientations of the indicated determinants.

Previous attempts to clone and identify the chromosome-borne pheromone determinants have been unsuccessful due to extensive probe degeneracy and the absence of a good screening assays. Using a new approach originally designed to identify the cAD1 determinant or determinants important to pheromone biosynthesis, we have found a gene necessary for the production of the pheromone in strain OG1X. While the determinant does not correspond to cAD1 per se, it appears to be critical for the synthesis of normal levels of the pheromone. Here we describe the characterization of this determinant and show that it can influence the production of not only cAD1 but other pheromones as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, reagents, and assays.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani broth (35) was used for the growth of Escherichia coli. E. faecalis strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) or brain heart infusion (Difco). Solid media used was Todd-Hewitt broth with 1.5% agar. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; erythromycin, 20 μg/ml for E. faecalis and 200 μg/ml for E. coli; streptomycin, 1 mg/ml; rifampin, 25 μg/ml; and fusidic acid, 25 μg/ml. X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (GIBCO BRL, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) was used at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. Synthetic cAD1 was prepared at the University of Michigan peptide synthesis core facility. Pheromone response (clumping) assays including preparation of culture filtrates were as previously described (18). Restriction enzymes were purchased from GIBCO BRL, and reactions were carried out under the conditions recommended.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. faecalis | ||

| OG1X | str gel | 29 |

| JH2-2 | rif fus | 32 |

| FA2-2 | rif fus | 14 |

| DS16 | Clinical isolate; carries pAD1 and pAD2 | 14 |

| 39-5 | Clinical isolate; carries pPD1 and 5 other plasmids | 51 |

| FA373 | FA2-2 carrying pAM373; Tn918(tet) on chromosome | 12 |

| FA3328 | OG1X eep mutant (OG1X containing integrated pAM3328) | This study |

| FA3328R | Revertant of FA3328 that had lost erm | This study |

| FA3329 | OG1X eep mutant (OG1X containing integrated pAM3329) | This study |

| FA3329R | Revertant of FA3329 that had lost erm | This study |

| E. coli DH5α | F− φ80 lacZΔM15 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 ΔgyrA96 (ΔlacZYA-argF)U169 | Promega Research Labs |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAD1 | 60 kb; encodes hemolysin/bacteriocin (cytolysin); responds to cAD1; originally found in DS16 | 14 |

| pAM2011 | pAD1::Tn917lac with insert 4 bp downstream from t2 | 41 |

| pAM2011E | Miniplasmid derivative representing large EcoRI fragment of pAM2011 | 46 |

| pPD1 | Encodes bacteriocin; responds to cPD1 pheromone | 51 |

| pOB1 | Encodes hemolysin/bacteriocin; responds to cOB1 pheromone | 39 |

| pCF10 | Carries Tn925 (tet); responds to cCF10 pheromone | 19 |

| pAM373 | Encodes response to cAM373 pheromone | 12 |

| pAM401 | E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle; cat tet | 50 |

| pBluescript SK+ II | E. coli plasmid vector; amp | Stratagene |

| pVA891 | E. coli plasmid vector; erm cat | 34 |

| pAM3325 | pAM401 derivative with 3,045-bp cloned from E. faecalis OG1X | This study |

| pAM3326 | pBluescript derivative with 3,045-bp fragment subcloned from pAM3325 | This study |

| pAM3327 | pAM401 derivative with PCR product representing ORF1 (eep) | This study |

| pAM3328 | pVA891 derivative with PCR fragment representing internal segment of eep | This study |

| pAM3329 | pVA891 derivative with PCR fragment representing internal segment of eep (fragment in opposite orientation compared to pAM3328) | This study |

General DNA and RNA techniques.

Routine screening of plasmid DNA was carried out by using a small-scale alkaline lysis procedure described previously (45). Plasmid DNA from E. coli was prepared with a Plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) as recommended by the manufacturer. Plasmid isolated from E. faecalis made use of equilibrium centrifugation in CsCl-ethidium bromide buoyant density gradients as described elsewhere (16). Plasmid DNA was analyzed by digestion with restriction enzymes and electrophoretic separation of fragments in 0.7% agarose gels; for Southern analyses, 1.5% agarose was used. Standard recombinant DNA techniques were used in the construction of plasmid chimeras (2). Introduction of plasmid DNA into cells was by electrotransformation as previously described (22).

PCR was performed with a Perkin-Elmer Cetus apparatus under conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Specific primers were synthesized at the Biomedical Research DNA Core Facility of the University of Michigan. In some cases, specific restriction sites were incorporated at the 5′ ends of the primers so that the PCR products could be subsequently cloned into the appropriate plasmid vector. PCR-generated fragments were purified by using QIAquick-spin columns (Qiagen), cleaved with the appropriate restriction enzyme(s), and ligated to the vector plasmid. For the generation of the PCR fragment representing an internal segment of eep, the primers used were 5′-ggaattCCACTTATACGATTCGC-3′ (891-TOP; contains incorporated EcoRI site) and 5′-ggaattCCTTCTGCACAATGGTTGTA-3′ (891-BOT; contains incorporated EcoRI site) (underlined in Fig. 2). The PCR product was ligated to pVA891 by using the EcoRI site and introduced into E. coli DH5α. The primers used to generate the product corresponding to an intact eep were 5′-cgggatccCGTGACAACGGCTACTTTA-3′ (EEP-TOP; contains incorporated BamHI site) and 5′-cgcggatccCGTTAACGTTGGAATTAACA-3′ (EEP-BOT; contains incorporated BamHI site). The PCR product was ligated to the shuttle vector pAM401 by using BamHI followed by introduction into DH5α; this resulted in pAM3327.

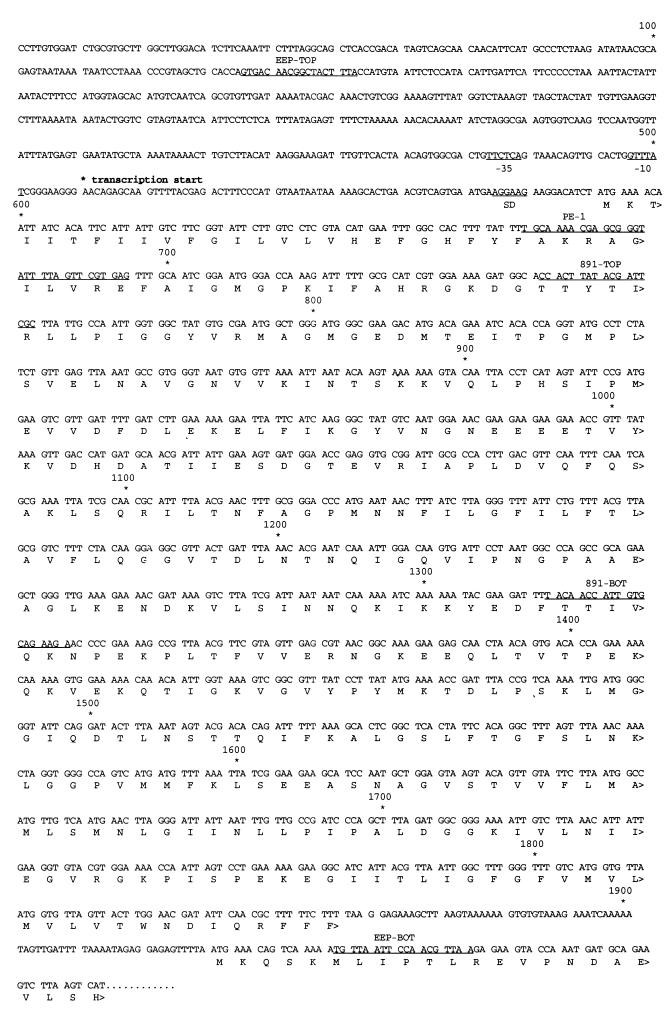

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and protein sequences of eep. Segments corresponding to specific primers used for generating PCR products as well as for the primer extension study are underlined, as are regions corresponding to possible Shine-Dalgarno (SD), −10, and −35 sequences. The beginning of a downstream open reading frame corresponding to what is likely for a prolyl-tRNA synthetase is also shown.

DNA sequencing was performed as previously described (6), and sequences were analyzed with a MacVector software package from Eastman Kodak. Southern blot analyses were as described elsewhere (2) and made use of a digoxigenin DNA labeling kit (Genius 2; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals).

Primer extension was conducted as described elsewhere (4). The primer used corresponded to 5′-CTCACGAACTAAAATACCCGCTCGTTTTGCA-3′ (PE-1).

Cloning of eep.

Cloning involved the use of the E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle vector pAM401 (50). Chromosomal DNA was extracted from a 100-ml culture of plasmid-free E. faecalis OG1X cells grown in brain heart infusion medium: ∼100 μg in 100 μl was partially digested with Sau3A and fractionated by centrifugation essentially as described elsewhere (2), using a sucrose-density step gradient consisting of 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40% concentrations of sucrose in 1 M NaCl–5.0 mM EDTA–20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5). Centrifugation utilized an SW41 rotor run at 25,000 rpm for 24 h. The 12-ml gradient was fractionated into 750-μl portions; 10-μl samples from each fraction were examined by gel electrophoresis. A fraction corresponding to a size of 3 to 8 kb was used for ligation with pAM401 that had been digested with BamHI and dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (GIBCO BRL). Ligated DNA was used to transform E. coli DH5α by electroporation, with selection for chloramphenicol resistance. Transformant colonies were pooled; the plasmid DNA mixture was extracted and used to transform E. faecalis OG1X/pAM2011E by electroporation and selection on X-Gal plates containing chloramphenicol and erythromycin. pAM2011E is a miniplasmid derivative of pAD1 containing the pheromone response regulatory region with a Tn917lac insertion just upstream of traE1 (46); the lacZ determinant is readily induced upon exposure of cells to pheromone. Plasmid DNA was isolated from cells deriving from blue colonies and introduced into E. coli DH5α, selecting for resistance to chloramphenicol.

Generation of eep mutants.

A PCR product corresponding to an internal segment of eep (see above) was generated as described above to obtain pAM3328 and pAM3329 by using the E. coli vector pVA891, which carries an erm determinant that expresses in both E. coli and E. faecalis. The inserts corresponding to the two clones were in opposite orientation in the vector, based on the position of a ClaI site. The plasmids were introduced by electrotransformation into E. faecalis OG1X, where integrants occurring via homologous recombination were selected by using erythromycin. Colonies arose at a frequency of about 10−8. The strains were designated FA3328 and FA3329. Revertants generated by growth for several (more than six) subcultures in the absence of erythromycin were obtained by screening for sensitivity to the drug. Depending on the original mutant, representative revertant strains were designated FA3328R and FA3329R.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession no. for the sequence shown in Fig. 2 is AF152237.

RESULTS

Our strategy for cloning E. faecalis determinants relating to pheromone production was to make use of the E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle plasmid pAM401 to shotgun clone fragments of E. faecalis OG1X chromosomal DNA first in E. coli, where transformation efficiencies are high, followed by introduction of plasmid DNA from pooled transformants into E. faecalis OG1X/pAM2011E. (pAM2011E is a miniplasmid derivative of pAD1 with a Tn917lac insertion on the traE1-proximal side of t2; it includes the region shown in the map of Fig. 1 in addition to replication determinants located further to the right.) The enterococci are much less efficiently transformed, especially by nonsupercoiled plasmid DNA; thus, the supercoiled configuration of chimeric DNA coming out of E. coli was believed to facilitate uptake by the enterococci. It was anticipated that E. faecalis OG1X/pAM2011E cells acquiring a multicopy plasmid chimera with a gene(s) that increased pheromone production may result in blue colonies on selective (chloramphenicol and erythromycin) X-Gal plates. The rationale was that additional pheromone would exceed the shutdown capacity of pAM2011E, which contains an intact traB and encodes normal synthesis of iAD1. Using this approach, detailed in the Materials and Methods, we were able to identify four clones which resulted in light blue colonies. Plasmid DNA from each of these derivatives was extracted and introduced back into E. coli DH5α, where it was then reisolated, digested with XbaI and SalI (sites for these enzymes flanked the original BamHI site used for cloning), and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. This revealed that in one case the cloned DNA was of a size of 3.0 kb (not shown), whereas the other three were 5 kb or larger. Electing to focus our subsequent studies on the smaller fragment, the corresponding chimera, designated pAM3325, was introduced into plasmid-free E. faecalis OG1X, selecting for chloramphenicol resistance. This gave rise to transformants with an increased production of cAD1 by a factor of 8; culture filtrates exhibited a cAD1 titer of 512, compared to 64 in the case of cells carrying an empty vector (Table 2). It is important to note that neither pAM3325 nor the three larger chimeras gave rise to detectable cAD1 expression in E. coli.

TABLE 2.

Sex pheromone detected in culture filtrates of E. faecalis strains

| Strain | Titer

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cAD1 | cPD1 | cCF10 | cOB1 | cAM373 | |

| OG1X | 64 | 64 | 16 | 2 | 16 |

| OG1X/pAM401 | 64 | 64 | 16 | 2 | 16 |

| OG1X/pAM3325 | 512 | 128 | 32 | 4 | 16 |

| OG1X/pAM3327 | 512 | 128 | 32 | 4 | 16 |

| FA3328 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | 16 |

| FA3328R | 64 | 64 | 16 | 2 | 16 |

| FA3329 | 2 | 2 | <2 | <2 | 16 |

| FA3329R | 64 | 64 | 16 | 2 | 16 |

Analysis of cloned DNA.

The cloned DNA present in pAM3325 was subcloned to pBluescript II SK, generating pAM3326; sequence analysis was then conducted (see Materials and Methods). The sequence exhibited two open reading frames, designated ORF1 and ORF2; neither contained the cAD1 sequence. Both were accompanied by appropriately positioned ribosome binding sites. ORF1 corresponded to 422 amino acids and is shown in Fig. 2; ORF2 corresponded to 372+ amino acids (the absence of a translational stop site implied that it continued beyond the end of the cloned DNA segment; only the first 23 amino acids are shown in Fig. 2). ORF2 is probably part of a prolyl-tRNA synthetase (ProS), as it had very strong similarity to a number of such proteins in the database. If it is assumed that its actual size is close to the average size of these proteins (about 564 amino acids), then the cloned portion (ORF2) would correspond to a protein missing about 34% from its carboxyl terminus.

ORF1 corresponded to a protein with a size of 46.5 kDa and pI of 6.28. A search in the database revealed strong similarity with proteins of unknown function in Bacillus subtilis and Haemophilus influenzae (see below). A PCR product containing only the ORF1 gene was generated and cloned in pAM401 in E. coli (see Materials and Methods), after which it was introduced into E. faecalis OG1X. This derivative, designated pAM3327 gave rise to an increase in cAD1 titer similar to that of pAM3325 (Table 2), consistent with the view that ORF1 and not ORF2 was the determinant relating to enhancement of pheromone production.

Generation of ORF1 mutation.

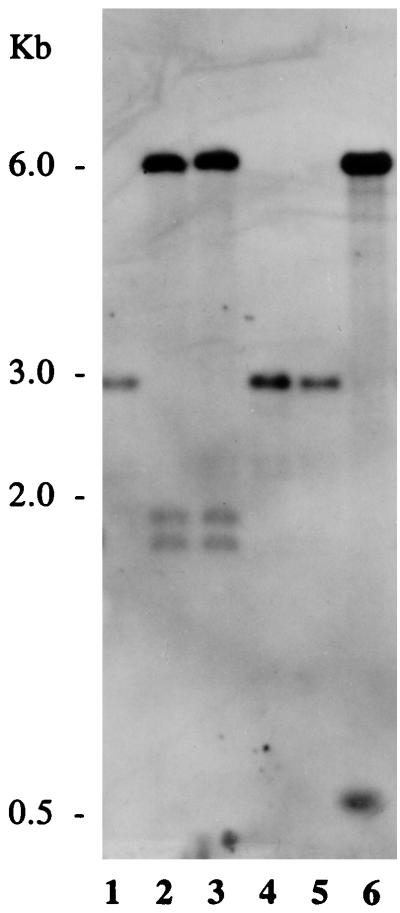

A PCR product representing an internal segment of DNA (Fig. 2) was ligated to the EcoRI site of the plasmid vector pVA891 and introduced into E. coli as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting chimera was then isolated and introduced into E. faecalis OG1X, selecting for transformants resistant to erythromycin. Since the vector was incapable of replicating in E. faecalis, transformants were expected to result from integration into the chromosome via recombination of homologous DNA. This would give rise to a mutation in the related determinant as long as the cells were maintained in the presence of erythromycin. With pAM3329 as a probe, it can be seen in the Southern blot of Fig. 3 that representative transformants resulting from each of two clones, FA3328 and FA3329, contained the integrated plasmid. Lane 1 shows the wild-type OG1X to have a single 2.9-kb EcoRI band representing the clone-related segment, whereas this band is missing in the two transformants (lanes 2 and 3) and is replaced by a much larger band (6.1 kb) corresponding to the integrated plasmid (pVA891) and two bands of 1.8 and 1.9 kb presumed to represent the two adjacent clone-containing segments. (The sum of the sizes of the two clone-containing bands of lanes 2 and 3 corresponds to the size of the original band of lane 1 plus the size of the introduced 586 bp segment [lower band in lane 6].)

FIG. 3.

Southern blot hybridization of E. faecalis chromosomal DNA digested with EcoRI. The probe corresponded to pAM3329 carrying an internal segment of eep. Lane 1, OG1X; lane 2, FA3328 (eep mutant); lane 3, FA3329 (eep mutant); lane 4, FA3328R; lane 5, FA3329R; lane 6, pAM3329.

Table 2 shows that when the strains carrying the integrated plasmid were examined for pheromone production, cAD1 activity was found to be reduced to a titer of less than 2 (i.e., undetectable) in the case of FA3328 and only 2 in the case of FA3329. It was also found that strains from which the plasmid had excised and segregated (FA3328R and FA3329R), secreted pheromone at the wild-type level (Table 2). The Southern blot shown in Fig. 3 confirmed that the integrated plasmid had segregated. Because of the connection between pheromone production and ORF1, we will subsequently refer to the determinant as eep (for enhanced expression of pheromone).

Effect on the production of different pheromones.

The additional presence of the plasmid-encoded eep determinant in E. faecalis OG1X cells also resulted in a slight (no more than twofold) increase in production of the pheromones cPD1, cOB1, and cCF10 (Table 2). There was no detectable increase, however, in the case of pheromone cAM373. A more significant effect on cPD1, cOB1, and cCF10 was noted in the case of eep-defective mutants, where these pheromones were not detectable (Table 2); cAM373 production remained normal.

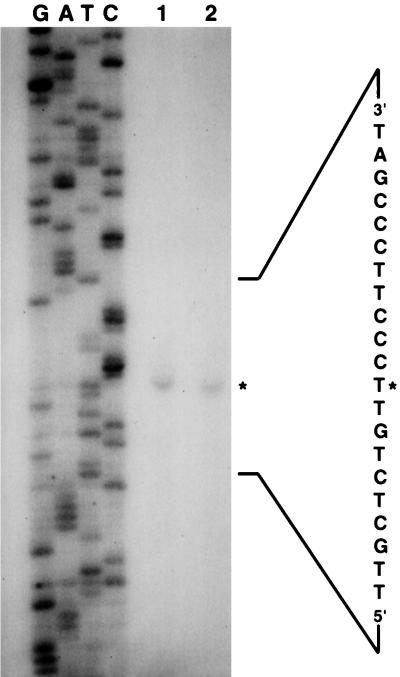

Transcriptional start site for eep.

The results of a primer extension study are shown in Fig. 4. The data imply that the initial ribonucleotide is an A which is located 80 nucleotides upstream from the translational start site (Fig. 2). Likely −35 and −10 hexanucleotides can be seen in an appropriate location upstream.

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis. Lanes 1 and 2 represent two different extractions of RNA from E. faecalis OG1X cells. The sequence data relate to use of the same primer, using as a template pAM3327. The asterisks marks the thymine corresponding to the 3′ end of the extended fragment; its complementary adenosine represents the 5′ transcriptional start site that is noted in Fig. 2.

Some apparent properties of Eep.

A hydrophilicity plot of Eep (not shown) revealed an apparent signal sequence as well as at least three additional membrane-spanning regions, one of which is located close to the carboxyl terminus. This suggests that Eep is a membrane protein. Using the GenBank BLASTP program, we found that Eep exhibited the strongest similarity with a hypothetical protein in B. subtilis (accession no. Z99112); regions over the entire 422 amino acids ranged from 33 to 62% identity and 48 to 75% similarity. Similarities with proteins of unknown function in H. influenzae (U60831) and Helicobacter pylori (AF016039) were also evident. The highest similarity with proteins having a known function were to metalloproteases from Treponema denticola (AE001235) and Chlamydia pneumoniae (AE001618).

DISCUSSION

Using a screening protocol devised to detect production of an increased amount of pheromone that might exceed the shutdown capacity of pAD1, we were successful in cloning a chromosomal determinant (eep) whose product indeed led to increased cAD1 secretion by the E. faecalis OG1X host. Eep itself does not contain the pheromone sequence but was necessary for pheromone expression. A knockout of the determinant resulted in a decrease in cAD1 titer from a titer of 64 to 2 or <2 (undetectable). Production of the pheromones cPD1, cOB1, and cCF10 was also reduced in the mutant; however, cAM373 was not affected. Deduced hydrophilicity properties suggested that Eep is a membrane protein, and comparisons of Eep to the GenBank database suggested some similarities to certain known bacterial proteases. Thus, it is conceivable that Eep corresponds to a membrane protein that may be involved in processing and/or secretion of the pheromone. The fact that when additional Eep was provided on a multicopy plasmid in trans an enhancement of pheromone expression was observed in wild-type cells suggests that there may be more cAD1 precursor than is normally processed or that Eep is able to enhance expression of the pheromone determinant.

Although the cAD1 pheromone determinant was not identified by using the approach described here, it is noteworthy that pheromone determinants are now beginning to reveal themselves via their appearance in the databases of complete genome sequencing projects. For example The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) has recently posted on their public domain web site (31a) a major portion of the genome sequence of E. faecalis V583 (42). Within this database are the pheromone sequences of cPD1 and cOB1, both of which appear to represent the final eight amino acid residues of the signal sequence of apparent lipoprotein precursors, and a sequence corresponding to cCF10 is present within two different determinants, one of which exhibits a possible relationship to the signal sequence of a lipoprotein precursor. The cAD1 determinant has not yet been identified in the TIGR database, which is still incomplete; however, very recently it has been identified in the database of another E. faecalis strain (2a). Preliminary PCR studies in our laboratory using primers based on the related sequence kindly provided by P. Barth have now revealed a similar determinant is present in E. faecalis OG1X as well as in the TIGR strain V893 (1). The cAD1 determinant (cad) corresponds to the final 8 residues in the signal sequence of an apparent lipoprotein precursor with a size corresponding to 143 amino acids and without any known homologues in the GenBank database. Thus pheromone secretion may be coupled to the processing and/or export of lipoprotein precursor structures. It would not be surprising if Eep is involved in such events; indeed, since at least some other pheromones (e.g., cPD1 and cCF10) were reduced in the eep mutant, perhaps their related precursors also make use of the protein for processing. The fact that cAM373 was not affected implies that production of at least some pheromones do not require Eep.

Firth et al. (21) have made the interesting observation that the traH gene encoded by the staphylococcal plasmid pSK41 encodes a lipoprotein precursor bearing a signal sequence containing seven of eight contiguous amino acids identical to those of cAD1 (a threonine is substituted for a serine). Indeed, staphylococcal strains carrying this plasmid actually secreted a detectable cAD1 activity. When intact traH was cloned in E. coli, clumping inducing activity was also detectable but not from a host deficient in SPase II (lipoprotein signal peptidase) (5). The pSK41 plasmid also encodes a protein TraJ which shares amino acid similarity with SPase II but which was not able to substitute for SPase II in E. coli. Although Eep could conceivably function in a similar way, it does not exhibit homology with SPase II or the pSK41 TraJ.

Finally, there is a point worth noting regarding the absence of any effect by Eep on expression of the cAM373 pheromone. This pheromone induces a response encoded by the conjugative plasmid pAM373 (12), which is smaller (size of 36 kb) than the other known pheromone plasmids, most of which are significantly larger (10, 49). In addition pAM373 differs from the others in that it does not have a homologous determinant for aggregation substance; recent sequencing data, however, have indicated that homologues of traA and traC of pAD1 are present (16a). A particularly interesting characteristic of pAM373 is the fact that peptides with activity similar to cAM373 are also produced by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus gordonii (12, 15).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM33956.

We thank H. Tomita and S. Fujimoto for helpful discussions and P. Barth, B. Dougherty, and K. Ketchum for help in gaining information about E. faecalis pheromone sequences in their databases.

REFERENCES

- 1.An, F. Unpublished data.

- 1a.An F Y, Clewell D B. Characterization of the determinant (traB) encoding sex pheromone shutdown by the hemolysin/bacteriocin plasmid pAD1 in Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 1994;31:215–221. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Barth, P. (Zeneca Pharmaceuticals). Personal communication.

- 3.Bastos M C F, Tanimoto K, Clewell D B. Regulation of transfer of the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responding plasmid pAD1: temperature-sensitive transfer mutants and identification of a new regulatory determinant, traD. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3250–3259. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3250-3259.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastos M C F, Tomita H, Tanimoto K, Clewell D B. Regulation of the Enterococcus faecalis pAD1-related sex pheromone response: analyses of traD expression and its role in controlling conjugation functions. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:381–392. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg T, Firth N, Skurray R A. Enterococcal pheromone-like activity derived from a lipoprotein signal peptide encoded by a Staphylococcus aureus plasmid. In: Horaud T, Sicard M, Bouve A, de Montelos H, editors. Streptococci and the host. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 1041–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen E Y, Seeburg P H. Supercoiled sequencing: a fast and simple method for sequencing plasmid DNA. DNA. 1985;4:165–170. doi: 10.1089/dna.1985.4.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow J W, Thal L A, Perri M B, Vazquez J A, Donabedian S M, Clewell D B, Zervos M J. Plasmid-associated hemolysin and aggregation substance production contributes to virulence in experimental enterococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2474–2477. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clewell D B. Movable genetic elements and antibiotic resistance in enterococci. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:90–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01963632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clewell D B. Bacterial sex pheromone-induced plasmid transfer. Cell. 1993;73:9–12. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90153-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clewell D B. Sex pheromones and the plasmid-encoded mating response in Enterococcus faecalis. In: Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 349–367. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clewell D B. Sex pheromone systems in enterococci. In: Dunny G M, Winans S C, editors. Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clewell D B, An F Y, White B A, Gawron-Burke C. Streptococcus faecalis sex pheromone (cAM373) also produced by Staphylococcus aureus and identification of a conjugative transposon (Tn918) J Bacteriol. 1985;162:1212–1220. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.1212-1220.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clewell D B, Pontius L T, An F Y, Ike Y, Suzuki A, Nakayama J. Nucleotide sequence of the sex pheromone inhibitor (iAD1) determinant of Enterococcus faecalis conjugative plasmid pAD1. Plasmid. 1990;24:156–161. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(90)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clewell D B, Tomich P K, Gawron-Burke M C, Franke A E, Yagi Y, An F Y. Mapping of Streptococcus faecalis plasmids pAD1 and pAD2 and studies relating to transposition of Tn917. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:1220–1230. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.3.1220-1230.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clewell D B, White B A, Ike Y, An F Y. Sex pheromones and plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis. In: Losick R, Shapiro L, editors. Microbial development. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. pp. 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clewell D B, Yagi Y, Dunny G M, Schultz S K. Characterization of three plasmid deoxyribonucleic acid molecules in a strain of Streptococcus faecalis: identification of a plasmid determining erythromycin resistance. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:283–289. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.1.283-289.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.De Boever, E. Personal communication.

- 17.Dunny G M, Brown B L, Clewell D B. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3479–3483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunny G M, Craig R A, Carron R L, Clewell D B. Plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis: production of multiple sex pheromones by recipients. Plasmid. 1979;2:454–465. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(79)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunny G M, Funk C, Adsit J. Direct stimulation of the transfer of antibiotic resistance by sex pheromones in Streptococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 1981;6:270–278. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(81)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunny G M, Leonard B A B. Cell-cell communication in gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:527–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Firth N P D, Fink, Johnson L, Skurray R A. A lipoprotein signal peptide encoded by the staphylococcal conjugative plasmid pSK41 exhibits an activity resembling that of Enterococcus faecalis pheromone cAD1. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5871–5873. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5871-5873.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flannagan S E, Clewell D B. Conjugative transfer of Tn916 in Enterococcus faecalis: trans activation of homologous transposons. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7136–7141. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7136-7141.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujimoto S, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1 sex pheromone response of Enterococcus faecalis by direct interaction between the cAD1 peptide mating signal and the negatively regulating, DNA-binding TraA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6430–6435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galli D, Friesenegger A, Wirth R. Transcriptional control of sex-pheromone-inducible genes on plasmid pAD1 of Enterococcus faecalis and sequence analysis of a third structural gene for (pPD1-encoded) aggregation substance. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1297–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galli D, Lottspeich F, Wirth R. Sequence analysis of Enterococcus faecalis aggregation substance encoded by the sex pheromone plasmid pAD1. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:895–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galli D, Wirth R, Wanner G. Identification of aggregation substances of Enterococcus faecalis after induction by sex pheromones. Arch Microbiol. 1989;151:486–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00454863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore M S, Segarra R A, Booth M C, Bogie C P, Hall L R, Clewell D B. Genetic structure of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1-encoded cytolytic toxin system and its relationship to lantibiotic determinants. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7335–7344. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7335-7344.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ike Y, Clewell D B. Evidence that the hemolysin/bacteriocin phenotype of Enterococcus faecalis subsp. zymogenes can be determined by plasmids in different incompatibility groups as well as by the chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8172–8177. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8172-8177.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ike Y, Craig R C, White B A, Yagi Y, Clewell D B. Modification of Streptococcus faecalis sex pheromones after acquisition of plasmid DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5369–5373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.17.5369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ike Y, Hashimoto H, Clewell D B. Hemolysin of Streptococcus faecalis subspecies zymogenes contributes to virulence in mice. Infect Immun. 1984;45:528–530. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.2.528-530.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ike Y, Hashimoto H, Clewell D B. High incidence of hemolysin production by Enterococcus (Streptococcus) faecalis strains associated with human parenteral infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1524–1528. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.8.1524-1528.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31a.Institute for Genomic Research. [Online.] http://www.tigr.org/mdb/mdb/html. The Institute for Genomic Research, Rockville, Md. [15 August 1999, last date accessed.]

- 32.Jacob A E, Hobbs S J. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:360–372. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.360-372.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jett B D, Jensen H G, Nordquist R E, Gilmore M S. Contribution of the pAD1-encoded cytolysin to the severity of experimental Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2445–2452. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2445-2452.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macrina F L, Evans R P, Tobian J A, Hartley D L, Clewell D B, Jones K R. Novel shuttle plasmid vehicles for Escherichia-Streptococcus transgeneric cloning. Gene. 1983;25:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mori M, Isogai A, Sakagami Y, Fujino M, Kitada C, Clewell D B, Suzuki A. Isolation and structure of Streptococcus faecalis sex pheromone inhibitor, iAD1, that is excreted by donor strains harboring plasmid pAD1. Agric Biol Chem. 1986;50:539–541. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori M, Sakagami Y, Narita M, Isogai A, Fujino M, Kitada C, Craig R, Clewell D, Suzuki A. Isolation and structure of the bacterial sex pheromone, cAD1, that induces plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis. FEBS Lett. 1984;178:97–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakayama J, Dunny G M, Clewell D B, Suzuki A. Quantitative analysis for pheromone inhibitor and pheromone shutdown in Enterococcus faecalis. Dev Biol Stand. 1995;85:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliver D R, Brown B L, Clewell D B. Characterization of plasmids determining hemolysin and bacteriocin production in Streptococcus faecalis 5952. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:948–950. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.2.948-950.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pontius L T, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1-encoded pheromone response in Enterococcus faecalis: nucleotide sequence analysis of traA. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1821–1827. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1821-1827.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pontius L T, Clewell D B. Conjugative transfer of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1: nucleotide sequence and transcriptional fusion analysis of a region involved in positive regulation. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3152–3160. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3152-3160.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahm D F, Kissinger J, Gilmore M S, Murray P, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanimoto K, An F Y, Clewell D B. Characterization of the traC determinant of the Enterococcus faecalis hemolysin/bacteriocin plasmid pAD1: binding of sex pheromone. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5260–5264. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5260-5264.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanimoto K, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1-encoded sex pheromone response in Enterococcus faecalis: expression of the positive regulator TraE1. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1008–1018. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1008-1018.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weaver K E, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1 sex pheromone response in Enterococcus faecalis: construction and characterization of lacZ transcriptional fusions in a key control region of the plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4343–4352. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4343-4352.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weaver K E, Clewell D B. Construction of Enterococcus faecalis pAD1 miniplasmids: identification of a minimal pheromone response regulatory region and evaluation of a novel pheromone-dependent growth inhibition. Plasmid. 1989;22:106–119. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(89)90020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weaver K E, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1 sex pheromone response in Enterococcus faecalis: effects of host strain and traA, traB, and C region mutants on expression of an E region pheromone-inducible lacZ fusion. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2633–2641. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2633-2641.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver K E, Clewell D B. Control of Enterococcus faecalis sex pheromone cAD1 elaboration: effects of culture aeration and pAD1 plasmid-encoded determinants. Plasmid. 1991;25:177–189. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(91)90011-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wirth R. The sex pheromone system of Enterococcus faecalis. More than just a plasmid-collection mechanism? Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:235–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wirth R, An F Y, Clewell D B. Highly efficient protoplast transformation system for Streptococcus faecalis and an Escherichia coli-S. faecalis shuttle vector. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:831–836. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.831-836.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yagi Y, Kessler R, Shaw J, Lopatin D, An F, Clewell D. Plasmid content of Streptococcus faecalis strain 39-5 and identification of a pheromone (cPD1)-induced surface antigen. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:1207–1215. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-4-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]