Abstract

New technologies and developments in hearing healthcare are rapidly transforming service models, delivery channels, and available solutions. These advances are reshaping the ways in which care is provided, leading to greater personalization, service efficiencies, and improved access to care, to name a few benefits. Connected hearing care is one model with the potential to embrace this “customized” hearing experience by forging a hybrid of health–technology connections, as well as traditional face-to-face interactions between clients, providers, and persons integral to the care journey. This article will discuss the many components of connected care, encompassing variations of traditional and teleaudiology-focused services, clinic-based and direct-to-consumer channels, in addition to the varying levels of engagement and readiness defining the touch points for clients to access a continuum of connected hearing care. The emerging hearing healthcare system is one that is dynamic and adaptive, allowing for personalized care, but also shifting the focus to the client's needs and preferences. This shift in the care model, largely driven by innovation and the growing opportunities for clients to engage with hearing technology, brings forth new, exciting, and sometimes uncomfortable discussion points for both the provider and client. The modern hearing care landscape benefits clients to better meet their needs and preferences in a more personalized style, and providers to better support and address those needs and preferences.

Keywords: connected hearing care, audiology, teleaudiology, person-centered

This article stems from a unique collaboration including authors from three different continents, with a blend of clinical, research, and hearing industry–related experience, and expertise in the design, implementation, and delivery of connected hearing care across all ages and specific to virtual care and digital health applications. Together the authors share a holistic view on the topic of the modern hearing care landscape and its potential to positively influence the hearing care journey.

In the 1940s, American psychologist Carl Rogers developed person-centered therapy. This was a break from more traditional models where the therapist was in the role of the expert, and instead focused on empowering the client. Carl Rogers is quoted as saying “In my early professional years, I was asking the question: How can I treat, or cure, or change this person? Now I would phrase the question in this way: How can I provide a relationship which this person may use for his own personal growth?” 1 This paradigm shift remains relevant today, in the era of self-directed and remote care. As providers embrace technology-mediated care models in the field of hearing healthcare, they can improve the capacity to empower the client in their care journey via efficient and equitable use of digital health advancements. This change also commands a new view of the role of the hearing care provider (HCP), as clients choose to experience different aspects of their care journey independently, requiring HCP's expertise at different stages and incorporating blended care.

This paradigm shift brings a need to focus in service delivery efforts on relationship-centered care (RCC): a framework for conceptualizing healthcare which recognizes that the nature and quality of relationships influence the process and outcomes of healthcare. 2 RCC allows HCPs to approach in-person, remote, or blended care scenarios in a holistic way, using evidence-based implementation frameworks that model human behavior associated with the chronic condition of hearing loss. 3 The relationship component of the care process will help achieve greater flexibility in the hearing journey as the provider and client weave through the continuum of care. This approach is devoted to the person and their well-being, based on individualized needs and preferences, incorporating, and expanding on person-centered care, beginning with a foundationally holistic view dating back to the 1940s.

This article will discuss the vision for a modern landscape of adult audiological care, with a focus on service-level continuums of care that are shaping the way in which HCPs and clients seek, experience, and embrace technological advancement.

CONNECTED HEARING CARE IN THE MODERN HEARING CARE LANDSCAPE

Connected health has emerged as a health management model that better aligns with the modern needs and preferences of those living in the digital era and has been defined as the following:

Connected Health encompasses terms such as wireless, digital, electronic, mobile, and tele-health and refers to a conceptual model for health management where devices, services or interventions are designed around the patient's needs, and health related data is shared, in such a way that the patient can receive care in the most proactive and efficient manner possible. All stakeholders in the process are 'connected' by means of timely sharing and presentation of accurate and pertinent information regarding patient status through smarter use of data, devices, communication platforms and people. 4

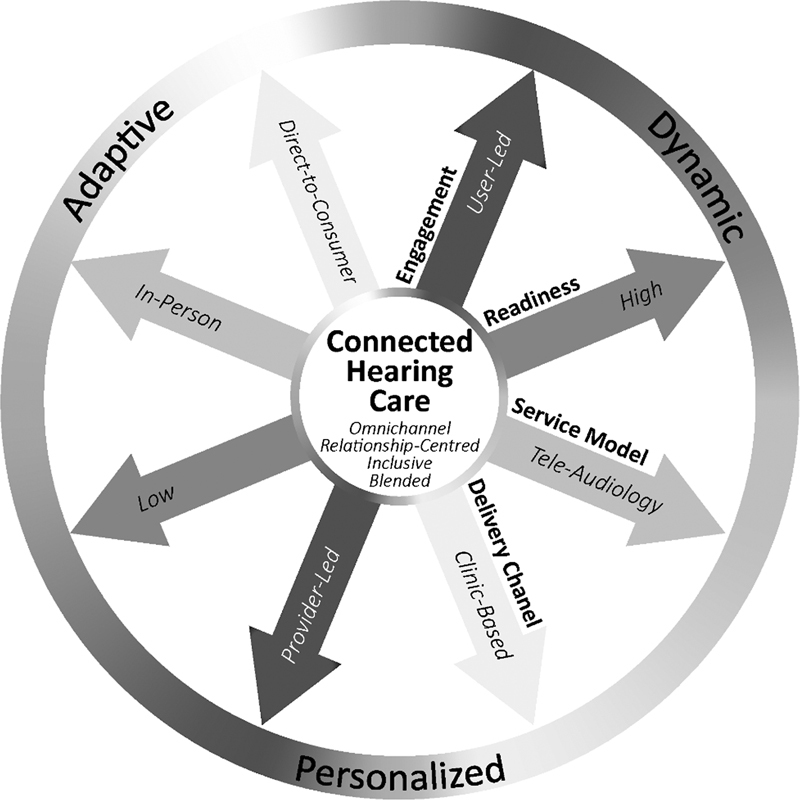

Hearing services delivered within a connected model can better embrace rapid technological advancement and facilitate integrated approaches to hearing care, with the potential to benefit hearing outcomes and service efficiencies, while maintaining a central focus on innovation as the future of hearing healthcare. 5 The provision of hearing services outside of the traditional care model often requires a certain readiness state that can vary across individuals based on their experiences, opportunities, motivations, and capabilities. Fig. 1 illustrates connected hearing care in a holistic way, including multidimensional continuums related to the personalized, dynamic, and adaptive hearing care process. This model presents multiple touch points at which the provider and/or the client can enter and fluidly travel through the care journey. Each journey is unique to accessibility considerations, needs, and preferences surrounding technology, services, and delivery channels. It is important to recognize that while functionality in technology platforms does not change readily after the point of purchase, domains that involve psychometric factors (such as readiness and engagement) can and will continue to change beyond the fitting of a device. In other words, a hearing aid fitted via a traditional channel, with clinic-based services, may still benefit from remote and/or blended hearing care. Therefore, decisions around the touch point and engagement level for the client or HCP will be influenced by access, needs, and preferences related to technology and infrastructure, across the time points of care. As such, the domains are experienced as continuums, rather than static or fixed points in the care process, with movement along the continuums relating to personalization.

Figure 1.

The multidimensional components of connected hearing care journey, illustrated as continuums leading to adaptive, dynamic, and personalized care.

Key care components can be defined as follows:

Engagement : Acknowledges varying levels of engagement in the connected hearing care process that span from provider-led to client-led, with the optimal touch point of relationship-centered care allowing for fluid engagement levels between the provider, the client, and all others important to the care process.

Readiness : Illustrates the dynamic and variable nature of readiness to engage in care within a connected hearing model. Readiness considers the state in which individuals are prepared to engage in the care process and acknowledges the interconnectedness of levels of readiness across providers, clients, and within the broader healthcare context.

Service model : Describes the location in which care is provided and the modality used to span traditional in-person to fully remote (teleaudiology) models of care, with blended services achieving optimal efficiency within the connected care model.

Delivery channel : Focuses on the selection, purchase, and delivery channel options around the provision of technology, such as a hearing aid, with a range of clinic-based and direct-to-consumer options.

The four care dimensions will ultimately be experienced differently along each unique care journey. The optimal experience will stem from the personalization of the hearing solutions, care relationships, and the overall care journey. The integration of different service models and delivery channels will ultimately promote an omnichannel client experience. Omnichannel, also recognized by the terms such as blended or hybrid, is defined as the “synergetic management of the numerous available channels and customer touch points, to optimize the customer experience.” 6 When applied to healthcare, the omnichannel experience can be seen as an empowering tool to support the client in making decisions that best meet their healthcare needs. A key opportunity that accompanies this concept is the client's ability to make decisions with, supported by, or without direct involvement from the HCP. This notion of self-directed care, driven by capacity, motivation, and client opportunity, will rely on HCP guidance and support to be successful. In a recent study by Bennett and colleagues, the likelihood of experiencing unresolved issues is reported to be higher for clients who do not seek assistance from their HCP, reminding us that the HCP will always remain a vital part of the client journey. 7 Clients with lower capacity to navigate the care journey could benefit from greater HCP direction and at different touch points, emphasizing the fluidity of omnichannel service provision.

PROVIDER AND CLIENT ENGAGEMENT WITH TECHNOLOGY

In the context of this article, hearing healthcare is discussed according to the engagement level of the HCP and/or the client, often shaped by technology accessibility. For example, in traditional hearing aid care, the HCP uses proprietary hearing aid fitting software in a clinic-based setting. In the modern care landscape, programming adjustments can be made outside of the clinic, directed by the client via a mobile app, with varying degrees of programming access according to the device type and manufacturer. Technology type alone does not dictate the engagement level for the client or provider; this is controlled by factors such as technology accessibility and client choice around service models and delivery channels. 8 In fact, an HCP could choose to provide any type of hearing device technology with any level of support, but not all types of technology will align with all provision models. Table 1 describes provider versus client engagement in the hearing aid fitting process (i.e., initialization or “first-fit” programming) and how this can be personalized along the care journey continuum. Hearing aid programming, facilitated through manufacturer-specific software, has traditionally been a task completed solely by the HCP. Recent innovation in hearing solutions now allows for greater access to programming, extending to user-led applications in some service scenarios. Remote programming of hearing aids can now be performed during initial and follow-up fitting appointments. This diversity of application is at the core of versatile, dynamic hearing care with hearing aids.

Table 1. Provider versus client engagement across hearing aid fitting service models.

| Engagement level | Technology accessibility | Stage of hearing aid care | Device selection/purchase/delivery channel | Service models | Level of personalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider-led (currently the predominant mode of hearing aid care) | Provider controlled/delivered in clinic or remotely via HCP-accessible fitting software | Initial fitting and follow-up | Clinic-based devices | Clinic-based/remote/blended | Low (based on in-person client feedback) |

| No access for client | NA | ||||

| Semi-client led (increasingly available though still a minority among major hearing aid brands) | Provider controlled/delivered in clinic or remotely via HCP-accessible fitting software | Initial fitting and follow-up | Clinic-based/DTC-provided devices | Clinic-based/remote/blended | Moderate (minimal or tokenistic client-controlled remote programming that may include a client–HCP feedback loop) |

| Client-controlled remote adjustment applications | Follow-up | Clinic-based/DTC-provided devices | Remote/blended | ||

| Client-led (most commonly found in self-fitting hearing aids and hearables via DTC channels but are compatible with clinic based and supported provision) | Provider accessible (variable control) clinic based/remote HCP-accessible fitting software |

Initial fitting/follow-up | Clinic-based/DTC-provided devices | Clinic-based/remote/blended | High (HCP programming and adjustment expertise and skills requested based on client needs and preferences along the care journey) |

| Client-controlled remote fitting/adjustment applications (self-fitting hearing aids and hearables) | Initial fitting/follow-up | Client-controlled | Remote/blended |

Abbreviations: DTC, direct-to-consumer; HCP, hearing care provider.

Considering all access channels, an HCP may choose to offer a suitable range of services and/or devices to better meet individual needs and preferences. For example, clients can be offered the option of purchasing self-fitting hearing aids from the clinic, with some clients choosing to have mostly provider-led programming. Alternatively, another client with the same product may choose programming independence with some use of teleaudiology, as demonstrated in the model used by Blamey Saunders hears. 9 In today's technological landscape, hearing aid capability will vary along with service options, as new technology enters the market. For example, access to teleaudiology may be limited or may exist in the absence of evidence to support practice. This research-to-practice gap poses a challenge in a monetary-focused hearing healthcare industry and calls for quality evidence to support practice. Pressures to serve those in need, such as that created by the pandemic, may result in practice before research, especially when the alternative is no care. However, there is an equal responsibility to build and share practice-based evidence to strive toward continuation of qualified theory-based practice. 10 It should be noted that some clinical tasks along the hearing care journey, such as real-ear measurement and speech-mapping, need further research and development efforts to be fully integrated into the processes for remote hearing aid fittings.

PROVISION AND SERVICE OPTIONS TO SUPPORT ENGAGEMENT

Hearing care services tailored to the client will better meet needs and preferences; this is true for all aspects of hearing care including those specific to hearing aid fitting. Unresolved hearing aid problems have been found to relate to lower levels of client-reported satisfaction and/or benefit, and commonly lead to loss of engagement as a result of negative experience. 11 Recent survey results from Bennett and colleagues indicate that 98% of hearing aid users report at least one hearing aid problem and as many as 54% of problems remain unresolved, as they were not reported to an HCP. 11 This speaks to the need for greater HCP/client engagement to guide technology benefit, and to ensure adequate help-seeking behaviors around follow-up care. Clinician bias in information sharing and decision making may be a factor in these results and is a factor that has been discussed within the allied health professions. 12 The current shift of the HCP's role to a supportive, partnership-based relationship has the potential to improve the balance between bias and benefit for all stakeholders. 13 The HCP's skills extend beyond device mastery such as customization of hearing aid performance (real-ear and prescriptive based), but importantly also can help build clients' self-management skills, help manage expectations around device use, and encourage active participation in goal setting and ongoing treatment planning. 3 14 It is also important for the HCP to consider that these activities will likely be iterative and dynamic, as communication needs and goals change over time. 15 Client engagement in the care process will therefore be strengthened through a dynamic relationship with their HCP, through improved education around technology and service-level options, aiming to personalize the care process.

Types of personalized hearing care services can include items such as offering the client a smartphone app connected to their hearing aids, a remote hearing aid fitting, or embracing the client's choice to purchase outside of traditional models, such as a direct-to-consumer (DTC) channel. Gomez et al (2022) found that smartphone-connected hearing aids empowered clients, by allowing them to take ownership and autonomously managing their hearing loss. 16 However, it should be recognized that clients may still need support to implement these tools successfully and overcome barriers to implementation. Mounting evidence, over the past two decades, supports the use of HCP-directed teleaudiology to improve physical fit and/or to facilitate frequency-gain, feature/setting, and program adjustments for a client in a remote location. 17 18 19 20 21 Client-led hearing care therefore still has much to gain from the involvement of the HCP, regardless of the technology accessibility, delivery channel, or service model chosen.

In a semi-client-led model, app-based remote services have exciting potential to engage clients and in a way that reflects their personal listening needs 22 23 ; ensuring the use of comprehensive and inclusive apps will facilitate better communication of needs back to the HCP. 24 As these modern technologies and service models are realized and embraced, progress is also made in closing the gap between client hearing aid challenges and those that are reported and successfully resolved by the HCP. Aligning with a client-led model, DTC hearing aid provision has been available for over a decade with various degrees of accessibility to the client and HCP. 22 23 25 Emerging research, comparing DTC and clinic-based sales channels, demonstrates that a DTC channel for the same product can have a positive impact on rates of adoption and adherence, as well as satisfaction, when compared with clinic-based fittings. 26 27 Whether DTC channels of care can meet individual client's needs will be influenced by a multitude of factors; there remains a need to keep investigating the factors driving hearing aid success that extend beyond the device capabilities, including technology engagement/adoption and service/delivery model options. The fact that we still see low rates of hearing aid adoption and adherence to traditional clinic-based services reminds us that there is much to learn for the benefit of all hearing care provision models. 28 29 Combining dynamic service models and channels with the strengths of RCC offers potential to improve the capabilities of the HCP and to better engage clients in a personalized way. Future research is needed to determine what factors influence client engagement along the connected care continuums, and how best to integrate these service/delivery models into clinical practice.

PERSONALIZING CARE WITH ACOUSTIC ECOLOGY

Outside of standard hearing aid service and delivery channels, we can envision a fitting process that accounts for the complexities of living with hearing aids, as experienced in real-life and according to one's ability to participate in daily activities. In real-life, listeners often report vastly different experiences and/or hearing aid expectation, warranting the need for a more comprehensive understanding of unique auditory lifestyles. 30 This sought after and rich relationship between the acoustical environments experienced in everyday life and the perceptual demands of individual listeners in these environments has been termed “auditory ecology.” 31 32 Auditory ecology is integral to achieving personalized and objective hearing care planning.

A better understanding of the client's auditory ecology can be incorporated along many stages of the audiological care journey, spanning from assessment to follow-up. Considering the sophistication of today's hearing aids, the quest for ecological validity in hearing aid fitting is becoming increasingly obtainable, as is the quest for device personalization. Digital hearing aids now have many advanced capabilities including the ability to log, analyze, and classify acoustic inputs to automatically adapt signal processing performance. 33 Paired with advancements in wireless connectivity capabilities, hearing aids can now connect to apps on smartphones and mobile technologies, making it possible to connect the hearing aid user to the hearing aid fitting process in new and exciting ways. For example, hearing aid logging (also known as data logging) has been reported in the literature as a way of informing hearing aid usage patterns for counseling, fine-tuning, and troubleshooting purposes and is starting to emerge as a way of informing hearing care needs. 34 35 36

Remote data collection methods focused on probing listeners' auditory ecology have emerged as viable research methods and clinical tools, alike. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods are currently implemented as e-surveys in mobile apps to collect subjective assessment of listener behaviors and experiences in real time, when immersed in real-life environments. A holistic picture of acoustic ecology can then be achieved by pairing this information with environmental acoustic data logging, although this capability is not yet clinically available. In recent research literature, EMA methods have proved useful as a way of comparing real-world hearing aid programming options, relating results to data collected around the participants' auditory reality. 37 38 Studies aimed at quantifying real-world aided benefit via EMA now include both adult and child participants, demonstrating that it is feasible to obtain real-world information for a wide age range of aided listeners and as part of daily-life research. 34 39 40 These methods have also been noted to have a fundamental advantage over the psychometric factors that negatively impact post-event recall that clinic-based care is traditionally founded on. 41 As the field of audiology starts to embrace new and exciting interactive technologies, we start to see a shift to person-centered audiological care. This shift brings the potential to connect the hearing aid user to their care journey as an active and engaged participant. We can start to fully recognize the potential of digital health as we embrace a blended service model that allows care to flow freely outside of the clinic, and into the daily lives of the persons with hearing difficulties; this shift will ultimately help hearing care focus on the everyday factors important to individual listeners' hearing- and communication-related function, activity, and participation.

MODERN HEARING CARE AS ADAPTIVE AND DYNAMIC CARE

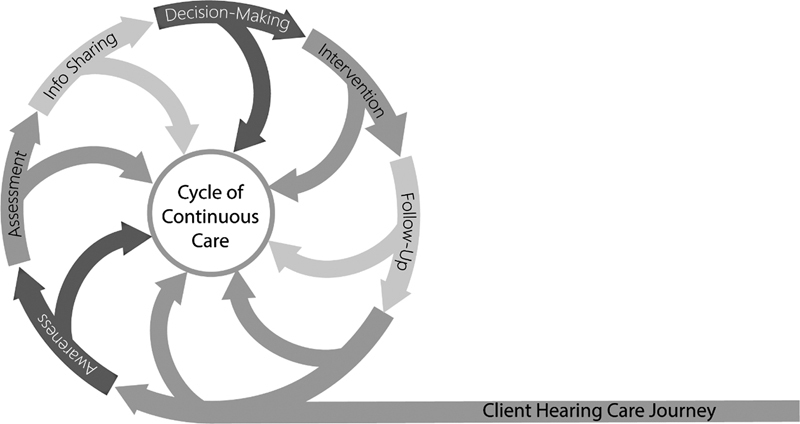

Hearing loss is a long-term condition, and the care journey can extend far beyond the fitting of hearing aids. High rates of hearing aid noncompliance serve as a warning that we are not yet successfully and thoroughly understanding what matters most in the client's hearing journey to be sustainable care. 28 29 The hearing loss does not cease to exist for the client once a client receives hearing aids, and there exists a need to return to various stages of the cycle of care as the needs and preferences of the client change over time. Fig. 2 depicts six stages that can exist along the client hearing journey, as a continuous and often iterative cycle of care. In this view of the client journey, incorporating RCC, the figure resembles a “rolling circle” of stages that are continuously contributing to the care journey, and not necessarily experienced in the same sequence across clients. Within the modern hearing care landscape, the contents of the stages can vary, depending on the client's level of engagement across the components of connected hearing care. When imagining the hearing aid care journey via teleaudiology, one can now understand how the entire process can take place virtually: beginning with a hearing test, review of assessment/evaluation results, goal setting and hearing aid selection, fitting and orientation, and follow-up and/or troubleshooting care. 22 23 This patient journey could also include varying levels of client engagement, embracing client-directed and/or semi-direct care, as depicted by Swanepoel and Hall in the “no-touch” patient journey. 42 The modern hearing care landscape can be visualized in many ways, depending on the services and delivery channels used, as well as the engagement and readiness levels experienced, and presenting varying opportunities for the provider to collaborate with the client around information sharing, decision making, and at many other stages. It can also be repeated, entirely, or partially, considering changes to the client's needs and/or preferences, such as is the case of a new hearing aid fitting. Despite repetition, each occurrence of these stages is a different “experience” for the client. Once a person has their first hearing test confirming a hearing loss, and first fitting with a hearing aid, no future test or fitting will fulfill the same purpose but will instead serve new needs and opportunities.

Figure 2.

Stages of the client hearing care journey, depicted as a continuous cycle.

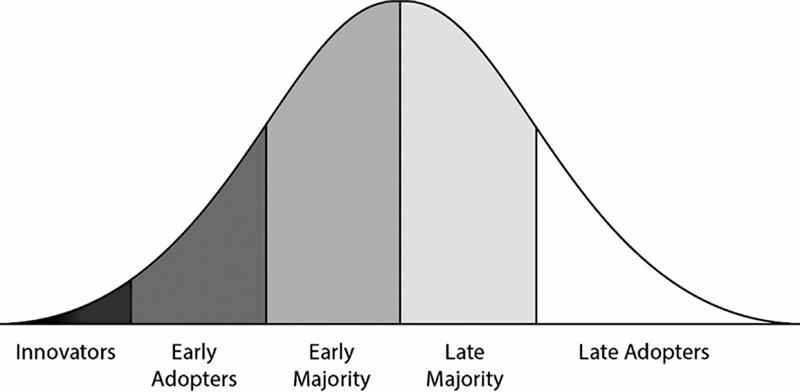

Adoption of the Modern Hearing Care Landscape

With the digital era comes rapid technological advancement and a changing hearing healthcare landscape for clients and providers. Clients have greater opportunities to actively participate and engage in many aspects of the care journey, while HCPs have new tools to provide comprehensive and holistic care with, and as empathetic and expert professionals. It is fair to say the landscape described in this article is not yet mainstream, but the service delivery options and technology are also not totally unknown to providers. Adoption of technologies, services, and other aspects of innovation within a connected care model will happen at different rates across individuals. This is best explained by Everett Rogers, through the well-known adoption curve, highlighting trends according to typical segments ( Fig. 3 ). 43

Figure 3.

Segments of the E.M. Roger's adoption curve. 43

In the earlier segments of the adoption curve, there is greater tolerance and more willingness to take on a bit more uncertainty. In practice, this translates to potentially working with new, often immature products, technology, or services. The late majority and late adopters may wait until it is “safer” to adopt such items, with less hassle factor and lower uncertainty. Factors such as technical feasibility will be established much earlier in the adoption curve, and by innovators or early adopters.

Let us take the example of electric cars. An individual may choose to be early in the adoption cycle and purchase an electric car. With this new technology, there are pain points in the beginning of the adoption curve, such as where to find a charging station on a road trip when the battery gets low. But as the adoption increases, the late adopters will enter when these uncertainties have been resolved by aspects such as infrastructure, technology, or price, for example. In hearing healthcare, we can look to the adoption of teleaudiology services for an analogy. The innovators who adopt remote hearing aid services, as part of a blended or purely online service model, are challenged to learn new methods with little evidence to follow. 22 44 45 However, this can pave the way for the research and praxis- led thorough validation of teleaudiology methods that we see today. 46 47 Currently, online providers of hearing care utilize teleaudiology and continue to expand their service capabilities as technology continues to develop, progressively overcoming infrastructure limitations. 22 48 Traditional clinical hearing care provision, however, still dominates the global proportion of hearing care.

Today's landscape is working well in many ways, but the literature also shows there is room to improve current audiological practices. 11 A client journey that reflects the continuums of connected hearing care (see Fig. 1 ), and the flexibility to lie at any point along each continuum, will help the HCP capture the optimal care journey for each client. When adaptive, dynamic, and personalized care is present, the journey into the modern hearing care landscape has begun.

SO NOW WHAT?

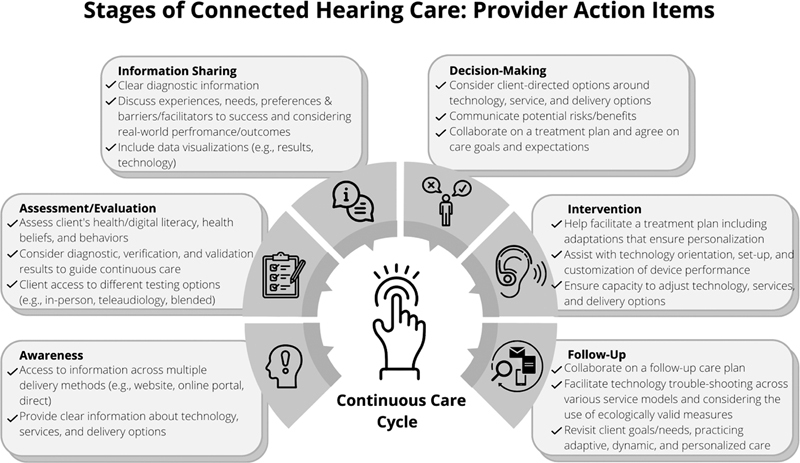

The four dimensions of care, engagement, readiness, service model, and delivery channel, presented in Fig. 1 present options in how the care journey can be experienced by both the HCP and the client. These four continuums are the variable options of both the HCP and the client to personalize the many steps of the client's journey. They represent multiple touch points at which the HCP or client can enter and fluidly travel along each individual's unique hearing care journey. The ability to view the key stages as interchangeable parts in the journey makes it fitting to present tangible considerations for clinical tasks to facilitate clinically meaningful change across the journey. Fig. 4 proposes considerations and action points to align the key elements of continuous care described in this article.

Figure 4.

Action items to consider in revising clinical hearing care practice toward adaptive, dynamic, and connected hearing care.

Providing clients with the opportunities to engage throughout the hearing journey requires collaboration, and this should be considered in each stage of connected hearing care. From awareness through to follow-up care, service and delivery options should reflect modern technologies and digital health applications available, offering flexibility in how each client can choose to engage. When presented as a care continuum, the stages are less sequential, and instead exist in order to be personalized to the needs and preferences of the client.

SUMMARY

The future of hearing care can be envisioned as a connected space in which the client and HCP are able to respond and adapt to each other. Ensuring provider and client engagement will require careful consideration of new service, technology, and delivery options available in the modern hearing care landscape. Clients now have more options around hearing aid access (delivery channel), capabilities (technology), and support structure (services); together these options can lead to a more individualized care journey and one that suits the changing needs/preferences of the client, at any point along their hearing loss journey. During this journey, the tools which are most appropriate for the client may change between provider-led, semi-user led, user-led, and a hybrid solution. When considering the plethora of digital health platforms (e.g., offline, Internet, mobile) and services available, more research is needed to unpack the barriers to clinical uptake and efficacy of teleaudiology in clinical practice, especially in terms of technology developments, technical and clinical validation, and optimization of strategies for service delivery. 40 Manageable adaptions can be achieved to bridge the care we currently offer and the care we hope to offer. The modern hearing care landscape is here to be realized, integrated, and adapted, as we embrace digital health advancements within hearing healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Robin O'Hagan for her assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Rogers C. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1961. On Becoming a Person: A Therapists View of Psychotherapy. Sentry edition (8) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soklaridis S, Ravitz P, Nevo G A, Lieff S. Relationship-centred care in health: a 20-year scoping review. Patient Exp J. 2016;3(01):130–145. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor B. Plural publishing; 2021. Relationship-Centered Consultation Skills for Audiologists: Remote and in Person Care. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caulfield B M, Donnelly S C. What is connected health and why will it change your practice? QJM. 2013;106(08):703–707. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glista D, Ferguson M, Muñoz K, Davies-Venn E. Connected hearing healthcare: shifting from theory to practice. Int J Audiol. 2021;60 01:S1–S3. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1896794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhoef P C, Kannan P K, Inman J J. From multi-channel retailing to omni-channel retailing. J Retailing. 2015;91(02):174–181. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett R J, Kosovich E, Cohen S. Hearing aid review appointments: attendance and effectiveness. Am J Audiol. 2021;30(04):1058–1066. doi: 10.1044/2021_AJA-21-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brice S, Saunders E, Edwards B. Scoping review for a global hearing care framework: matching theory with practice. Semin Hear. 2023;44(03):213–231. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1769610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders E, Brice S, Alimoradian R. IGI Global; 2019. Goldstein and Stephens revisited and extended to a telehealth model of hearing aid optimization; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brice S, Almond H. Is teleaudiology achieving person-centered care: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):7436. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett R J, Kosovich E M, Stegeman I, Ebrahimi-Madiseh A, Tegg-Quinn S, Eikelboom R H. Investigating the prevalence and impact of device-related problems associated with hearing aid use. Int J Audiol. 2020;59(08):615–623. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1731615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Featherston R, Downie L E, Vogel A P, Galvin K L. Decision making biases in the allied health professions: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0240716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ida Institute Future hearing journeys report Ida Institute; Naerum, Denmark. P31. Accessed June 2022:https://idainstitute.com/fileadmin/user_upload/Future_Hearing_Journeys/Future_Hearing_Journeys_Ida_Institute_2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Convery E, Keidser G, Hickson L, Meyer C. The relationship between hearing loss self-management and hearing aid benefit and satisfaction. Am J Audiol. 2019;28(02):274–284. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brice S, Timmer B, Barr C. Centering on people: how hearing healthcare professionals can adapt to consumers' need and outcomes. Semin Hear. 2023;44(03):274–286. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1769624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez R, Habib A, Maidment D W, Ferguson M A. Smartphone-connected hearing aids enable and empower self-management of hearing loss: a qualitative interview study underpinned by the behavior change wheel. Ear Hear. 2022;43(03):921–932. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angley G P, Schnittker J A, Tharpe A M. Remote hearing aid support: the next frontier. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017;28(10):893–900. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos P D, Ferrari D V. Teleaudiology: evaluation of teleconsultation efficacy for hearing aid fitting. J Soc Bras Fonoaudiol. 2012;24(04):301–308. doi: 10.1590/s2179-64912012000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao K FM, Moreira T C, Jayakody D MP. Teleaudiology hearing aid fitting follow-up consultations for adults: single blinded crossover randomised control trial and cohort studies. Int J Audiol. 2021;60 01:S49–S60. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1805804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penteado S P, Ramos SdeL, Battistella L R, Marone S A, Bento R F. Remote hearing aid fitting: tele-audiology in the context of Brazilian public policy. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;16(03):371–381. doi: 10.7162/S1809-97772012000300012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, Groth J. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(06):798–804. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrams H B, Singh J. Preserving the role of the audiologist in a clinical technology, consumer channel, clinical service model of hearing healthcare. Semin Hear. 2023;44(03):302–318. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1769627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckett R C, Blamey P J, Saunders S. IGI Global; 2016. Optimizing Hearing Aid Utilisation Using Telemedicine Tools. Encyclopedia of E-Health and Telemedicine; pp. 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiFabio D L, O'Hagan R, Glista D. A scoping review of technology and infrastructure needs in the delivery of virtual hearing aid services. Am J Audiol. 2022;31(02):411–426. doi: 10.1044/2022_AJA-21-00247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kochkin S.A comparison of consumer satisfaction, subjective benefit, and quality of life changes associated with traditional and direct-mail hearing aid useHearing Review2014210116–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humes L E, Rogers S E, Quigley T M, Main A K, Kinney D L, Herring C. The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Audiol. 2017;26(01):53–79. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr G. Using telehealth to engage teenagers. ENT Audiol News. 2017;25(06):2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillon H, Day J, Bant S, Munro K J. Adoption, use and non-use of hearing aids: a robust estimate based on Welsh national survey statistics. Int J Audiol. 2020;59(08):567–573. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1773550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCormack A, Fortnum H. Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them? Int J Audiol. 2013;52(05):360–368. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.769066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lelic D, Nielsen J, Parker D, Marchman Rønne F. Critical hearing experiences manifest differently across individuals: insights from hearing aid data captured in real-life moments. Int J Audiol. 2022;61(05):428–436. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1933621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gatehouse S, Naylor G, Elberling C. Benefits from hearing aids in relation to the interaction between the user and the environment. Int J Audiol. 2003;42 01:S77–S85. doi: 10.3109/14992020309074627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schafer R M. Simon and Schuster; 1993. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glista D, O'Hagan R, Cornelisse R.Combining passive and interactive techniques in tracking auditory ecology in hearing aid useHearing Review2020

- 34.Glista D, O'Hagan R, Van Eeckhoutte M, Lai Y, Scollie S. The use of ecological momentary assessment to evaluate real-world aided outcomes with children. Int J Audiol. 2021;60 01:S68–S78. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1881629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humes L E, Rogers S E, Main A K, Kinney D L. The acoustic environments in which older adults wear their hearing aids: insights from datalogging sound environment classification. Am J Audiol. 2018;27(04):594–603. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muñoz K, Rusk S EP, Nelson L. Pediatric hearing aid management: parent-reported needs for learning support. Ear Hear. 2016;37(06):703–709. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen N S, Hau O, Lelic D, Herrlin P, Wolters F, Smeds K.Evaluation of auditory reality and hearing aids using an ecological momentary assessment (EMA) approachPaper presented at the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics; September 9–13, 2019; Acachen, Germany

- 38.Wu Y H, Stangl E, Chipara O, Hasan S S, DeVries S, Oleson J. Efficacy and effectiveness of advanced hearing aid directional and noise reduction technologies for older adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2019;40(04):805–822. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timmer B HB, Hickson L, Launer S. The use of ecological momentary assessment in hearing research and future clinical applications. Hear Res. 2018;369:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Gablenz P, Kowalk U, Bitzer J, Meis M, Holube I. Individual hearing aid benefit in real life evaluated using ecological momentary assessment. Trends Hear. 2021;25:2.331216521990288E15. doi: 10.1177/2331216521990288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mofsen A M, Rodebaugh T L, Nicol G E, Depp C A, Miller J P, Lenze E J. When all else fails, listen to the patient: a viewpoint on the use of ecological momentary assessment in clinical trials. JMIR Ment Health. 2019;6(05):e11845. doi: 10.2196/11845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swanepoel D W, Hall J W. Making audiology work during COVID-19 and beyond. Hear J. 2020;73(06):20–22. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers E M. Categorizing the adopters of agricultural practices. J Rural Sociology. 1958;23(04):346–354. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saunders E.From the bionic ear to the audiologist in your pocket 2015. Accessed June 1, 2023 at:https://www.scienceinpublic.com.au/media-releases/incus-launch [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hearing Collective ServicesAccessed May 20, 2020 at: https://www.hearingcollective.com/services. (See also Penno, Kat. “Wow Woman in Wearabletech: Kathryn 'Kat' Penno, Founder and Audiologist at Hearing Collective.” edited by Marija Butkovic. Women of Wearables, 2020. Accessed May 20, 2020 at:https://www.womenofwearables.com/new-blog/wow-woman-in-wearable-tech-kathryn-penno-hearing-collective

- 46.Blamey P J, Blamey J K, Saunders E. Effectiveness of a teleaudiology approach to hearing aid fitting. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(08):474–478. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15611568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eikelboom R H, Bennett R J, Brennan M. Ear Science Institute Australia; 2021. Tele-audiology: An Opportunity for Expansion of Hearing Healthcare Services in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders E. IGI Global; 2019. Tele-Audiology and the Optimization of Hearing Healthcare Delivery. [Google Scholar]