Abstract

Healthcare systems are traditionally a clinician-led and reactive structure that does not promote clients managing their health issues or concerns from an early stage. However, when clients are proactive in starting their healthcare earlier than later, they can achieve better outcomes and quality of life. Hearing healthcare and the rehabilitation journey currently fit into this reactive and traditional model of care. With the development of service delivery models evolving to offer services to the consumer online and where they are predominately getting their healthcare information from the internet and the advancement of digital applications and hearing devices beyond traditional hearing aid structures, we are seeing a change in how consumers engage in hearing care. Similarly, as the range of hearing devices evolves with increasingly blended and standard levels of technology across consumer earbuds/headphones and medical grade hearing aids, we are seeing a convergence of consumers engaging earlier and becoming increasingly aware of hearing health needs. This article will discuss how the channels, service, and technology are coming together to reform traditionally clinician-led healthcare models to an earlier consumer-led model and the benefits and limitations associated with it. Additionally, we look to explore advances in hearing technologies and services, and if these will or can contribute to a behavioral change in the hearing healthcare journey of consumers.

Keywords: hearing aids, hearable, online, service models, behavior, data

Hearing loss is not easy to evaluate or understand. Sure, we have the 100-year-old audiogram that categorizes hearing loss, but when clinicians describe loss in terms of severity utilizing this tool, does this really equate to the consumers experience? If consumers truly held value in the audiogram and thus hearing loss, then would not anyone who was diagnosed with a loss immediately do something about it?

The research shows that the audiogram is good for many things; however, it is evident that it is severely lacking in areas of translation, connection, and understanding to the consumer. Not to mention, the predominate models of hearing healthcare reinforce a medical model of behavior seeking, meaning the consumer must attend an appointment and consult with a professional before learning more about a remedy for their loss. On top of stigma, cost, and time, the aforementioned features contribute to consumers delaying the management of hearing loss and care, resulting in a reported average hearing aid adoption at the age of 74 years. 1 2 Evidence shows the average delay in years is 8 to 9 years after learning about hearing aid candidacy. 3 Yet, evidence has also shown for a long time that clients who are actively involved and engaged in their healthcare management demonstrate better long-term outcomes and higher quality of life. 4 5 6

Furthermore, the systemic legacy of traditional hearing healthcare models has been reinforced by the insurers and government-funded agencies. For example, programs such as Hearing Services Programs reinforce audiometric criteria that is not client-centered or in line with the impact of hearing loss regardless of severity. The current approach is in effect, based on limitations from the audiogram. Consumers who report hearing difficulties may not meet audiometric minimums; however, their functional hearing and quality of life may be significantly impacted. This is not unique to Australia, with funding from the National Health Scheme in the United Kingdom demonstrating unique rationale for fitting hearing aids, but not necessarily aural counseling/rehabilitation. Insurers compound this issue when the policies and rebates that are derived from measures, such as the quality-adjusted life-years to measure if and whether to fund various rehabilitative programs, 7 do not match the individual needs or the impact of chronic conditions on the community that economies face.

Vast improvements in hearing technology have occurred over the last couple of decades, along with various efforts to improve standards of audiological care to be more considerate to the client's needs and experience, aiming to improve adoption and adherence to hearing care. However, despite these efforts, we have not witnessed a significant change in the hearing aid uptake age, nor a significant change in the way audiological services are delivered despite the availability of new innovations and technology appearing in the last decade. 1 2 8 Not to mention recommendations by the World Health Organization (2021) and research showing subclinical or no audiometrically defined hearing loss being linked to further health impacts such as mild cognitive impairment. 9 10 11

Adult rehabilitation stems deeper than device adoption, 3 and consumers must continuously use the device and re-train their auditory pathways to maximize their chances of improving quality of connectedness. An important goal of audiological care is therefore to achieve a sustained use of hearing care products, which requires positive positioning in attitude, engagement, and ultimately behavior change in the consumer.

It is evident that the traditional models of care and the traditionally fitted hearing aids are being challenged by emerging technologies and markets that go beyond the traditional medico-clinician-led models of care. 12 The question is, will these new emergent devices and segments solve the issue of delayed or unsuccessful hearing aid adoption and rehabilitation care and access to hearing health professionals.

Technology

Previously, hearing aids and consumer audio, such as ear buds, were two distinct types of devices with different audiological capabilities and service support features. Hearing aids were designed as medical devices for mild to profound hearing loss, and were fitted for individual needs by a clinician in a clinic. In contrast, ear buds were designed as accessories for people with normal hearing, and were adjusted for individual preferences by their user in real-world listening situations.

Over the last two decades, these two types of devices have acquired some of each other's characteristics and become less distinct, yet consumer behavior is considered to be quite different between the two. For example, hearables have emerged as a new class of consumer audio device that can compensate for mild to moderate hearing loss. Nowadays, some hearing aids can be self-fitted for individual needs by their user away from an audiology clinic. Both types of devices have adopted new features, such as Bluetooth wireless connectivity and control via smart phone software applications. Therefore, device type (e.g., hearing aid or hearable) is no longer strictly a category of hearing technology products—it can now be viewed as another characteristic of hearing technology products, alongside audiological capability and service support . Table 1 shows these three characteristics, which are described in more detail in the following sections. Ideally, people who need a certain level of audiological capability should be able to choose the device type and service support that they need.

Table 1. Characteristics of hearing technology products.

| Characteristic | Examples |

|---|---|

| Device type | Hearing aid (medical device) or hearable (consumer device) |

| Audiological capability | Sound processing features (e.g., amplification, noise reduction, feedback management, wireless audio streaming) |

| Service support | Clinical fitting software or self-fitting phone app, wireless remote control, first fit from online hearing test |

Device Type

Hearing aids and hearables remain distinct in their external appearance, and differ in their internal mechanical design and electronic circuits. These physical differences are due to differences in their target markets and technical requirements.

Hearing aids are designed to provide high amounts of amplification and perform sophisticated sound processing to compensate for mild to profound hearing loss. This requires hardware with excellent acoustic, electromagnetic, and vibrational isolation between microphone and receiver circuits. However, this must be achieved with the conflicting requirements of small size and long battery life. This stringent set of requirements has encouraged the refinement and miniaturization of traditional form factors; so, while hearing aids have become smaller and more cosmetically appealing, to the eye they are still obviously hearing aids. The need for specialized, miniature, low-power circuits has delayed the adoption of some consumer audio technologies, such as Bluetooth wireless connectivity. However, hearing aids have led the introduction of some sound processing features to compensate for hearing impairment, such as frequency compression.

In comparison, hearables tend to appeal to people who do not want to be seen using hearing aids. Therefore, the physical shapes of familiar consumer devices, such as ear buds, have been used, which can also harness the power of brand influence. However, without a custom fit in the ear canal, the close proximity of the microphones to the receiver limits the maximum amount of amplification that can be achieved without feedback, which is generally suitable for up to moderate hearing loss. On the other hand, the more relaxed size and battery life requirements have allowed the use of consumer electronics, which can reduce manufacturing costs and provide earlier access to new technologies, such as Bluetooth wireless connections. Nowadays, hearables can perform sophisticated sound processing to compensate for hearing impairment, and how this compares with hearing aids can depend on differences in physical design (e.g., number of microphones and their locations) and electronic circuits (e.g., computational power of digital signal processors).

Another distinction is that hearing aids are registered as medical devices with the regulatory authorities, while hearables are considered as unregistered consumer devices. Therefore, additional stipulations apply to the design, manufacture, and performance claims of hearing aids. However, this should not detract from the use of hearables, since a full understanding of their functionality shows that they are very capable for their intended use, such as for people with early hearing loss who are not ready to visit a clinic.

Audiological Capability

When comparing devices with similar physical form factors (such as an in-the-ear hearing aid with an ear bud hearable) and similar electronic circuit capabilities, their ability to compensate for sensorineural hearing loss is largely determined by their digital sound processing algorithms.

Nonlinear amplification is commonly used to compensate for elevated hearing threshold levels, while preferably making speech comfortably loud and avoiding loudness discomfort. Both types of devices use similar amplification strategies, such as wide dynamic range compression, and fitting prescriptions, such as NAL-NL2, 13 within their hardware gain limits.

When the amount of amplification approaches or exceeds the amount of ear-canal occlusion provided by the device, the cancellation and suppression of acoustic feedback is needed to avoid a metallic sound quality, spontaneous acoustic chirps, and sustained whistling. Since in-ear hearing aids and hearable ear buds have similar microphone and receiver locations, similar feedback management algorithms are applicable to both device types. The required strength of these algorithms would depend on differences in gain, occlusion, and mechanical design between device types.

Sensorineural hearing loss is associated with reduced speech understanding in noise and reduced acceptable noise levels. Directional microphone algorithms improve speech understanding in noise, by combining the outputs of two microphones at one ear to cancel noise from specific directions, and are commonly implemented in hearing aids and hearables. Binaural directional beam formers, which wirelessly combine microphones at both ears to achieve greater directionality, have recently appeared in hearing aids to provide even greater client benefit in very noisy listening situations.

Environmental noise suppression reduces the gain at frequencies where the speech-to-noise ratio is low (preferably where speech is not intelligible) to improve listening comfort and ease of speech understanding. 14 This is another type of algorithm that is commonly implemented in both device types.

Impulsive noise suppression improves loudness comfort by reducing the amplification of transient sounds, such as cutlery hitting a plate, which are typically broadband and appear too quickly to be adequately controlled by nonlinear amplification. Whether this type of algorithm can respond quickly enough to control the impulse depends on the device's signal processing architecture; so, neither type of device has an inherent advantage.

Wind noise suppression reduces the amplification of noise that is caused when turbulent air flows across microphone inlet ports. The severity of the wind noise depends on the physical shape of hearing aids and their microphone locations. 15 16 17 Therefore, physical differences between hearing aids and hearables could result in different amounts of wind noise being generated. Both types of devices can implement processing to reduce the gain at frequencies dominated by wind noise, which should improve listening comfort since wind noise can saturate microphone circuits. 17 Some hearing aids use a wireless link to implement more sophisticated binaural wind noise reduction, which streams audio from the less-affected ear to the more-affected ear.

While several types of sound processing algorithm are commonly found in both types of devices, some are found only in one or the other type of device. For example, it is more common for hearing aids to feature frequency compression, which compensates for the reduced aidable bandwidth of sloping hearing loss and impulsive sound suppression, which ensures that impact sounds are not over-amplified for the hearing loss. In comparison, hearables were the first to feature active noise cancellation (ANC), which increases the speech-to-noise ratio to improve listening comfort and speech understanding in noise, and Bluetooth wireless technology, which enables audio streaming and remote control of sound processing settings. These differences in sound processing algorithms determine each device's ideal application. Hearables are most suitable for early or mild hearing loss, where little (if any) amplification is needed, and listening difficulties occur only in some situations, such as holding conversations in noise. Even with high-frequency hearing loss, the provision of directional microphones without amplification can improve speech understanding in noise. 18 In comparison, hearing aids are most suitable for greater hearing loss, when listening difficulties occur in all situations, and where more clinical intervention is required. However, there is a range of no-to-moderate hearing loss where either type of device could be used. In the future, the differences in feature sets between hearing aids and hearables should continue to diminish as they continue to acquire each other's features.

Service Support

Traditionally, hearing loss is diagnosed via pure-tone audiometry performed in a clinic. In the last two decades, there has been a move toward assessment of hearing abilities via telephone 19 20 21 and now more commonly online via the internet. Adapting screening tools to be more accessible to the consumer is hoped to be more convenable to their use, supporting or encouraging engagement and access for the consumer wherever possible. Examples of internet accessible test methods include tests of pure-tone hearing thresholds, 22 speech understanding in quiet, 23 24 and speech understanding in noise. 20 25 Some of these tests can predict the user's pure-tone audiogram or comfortable loudness levels with sufficient accuracy to generate a first fit in hearing aids. 24 26 Over the last decade, this has allowed devices to be purchased online and shipped to the user already set up for the client's hearing loss. 27 28 Alternatively, some hearing aids and hearables can generate sounds to measure their user's hearing loss directly, and then generate a first fit based on these in situ measurements. This is achieved via a remote session, where a clinician controls the devices via an internet connection, or independently of a clinician where device users test their own hearing via a smartphone software application. In the future, these different types of remote tests should be used together to paint a more complete picture of someone's hearing, rather than just predict their audiogram, and especially since speech understanding in quiet and in noise is important to device users and are not well predicted from the audiogram alone. 29 30

After a first fit is generated, it is important that the sound processing algorithms in both types of devices are appropriately fine-tuned for the individual needs and preferences of the device user. Otherwise, the device may not provide its maximum benefit to its user, who may reject it and return it to the manufacturer. One of the ultimate costs of an ill-fitted hearing device is for the consumer to lose engagement in their hearing care or for their attitude to shift in a negative direction. The capacity to adjust, or fine-tune, a hearing device is therefore of key importance in successful hearing care. How this is achieved has changed as technology has evolved.

The fine-tuning of hearing aids is traditionally done in a clinic by an audiologist, who adjusts the aid settings based on verbal feedback from the aid user. Weaknesses of this approach are that it relies on (1) the ability of the aid user to describe the problem to the clinician; (2) the ability of the clinician to translate the description of the problem into an adjustment of one of more sound processing features; and (3) the lack of real-time assessment of the efficacy of these adjustments in the problematic listening situations. The strength of this approach is that a trained clinician should know what features to adjust to solve a given problem, while the untrained hearing-aid user would be daunted by clinical fitting software that typically exposes the settings for each sound processing feature.

In contrast, consider a hearable that is purchased online, and is self-fitted and fine-tuned by its user in real-world listening situations via an app. Strengths of this approach include (1) the potential use of a scientifically validated fitting method away from a clinic; (2) fine-tuning is done by the user in listening situations where adjustments are needed; and (3) the efficacy of fine-tuning adjustments is immediately assessed, which has the potential to lead to better settings more quickly. However, the success of this approach can heavily depend on the design of the app. The device user cannot be expected to know what technical features to adjust; so, the app needs to provide a user interface that relates to hearing in plain language. Otherwise, the device user may not achieve a good fitting and will require support to achieve the desired outcome. There is therefore a careful balance to be found between supporting the consumer experience of using the device and assuring the consumer achieves satisfactory outcomes with it.

However, over the last decade, an increasing number of hearing aids have been purchased online and then self-fitted and adjusted via an app, in a similar manner to hearables described earlier. The processes vary widely across manufacturers, with different hearing tests, fitting methods, and fine-tuning user interfaces used. These technologies existed before the COVID-19 pandemic, and were brought into the foreground of traditional clinical practice during the pandemic. This is an active area of research and development by manufacturers; so, in the future it should be more common for hearing aids to be purchased online, self-fitted, and fine-tuned for individual needs by the device user. The established practice of self-fit hearing aids (e.g., Blamey Saunders hears) and direct-to-consumer (DTC) service models (e.g., Lively) show that outcomes need not be compromised compared with traditional clinic-based services. 27 31 Instead, these models serve as a reminder that we must proactively keep learning to ensure that all online models, for hearing aids and hearables alike, can maintain the highest quality of care and support to ensure that outcomes and needs are met.

Choice of Technology and Services

Behaviors

At the crux of the hearing health journey is a change in consumer and clinician behaviors. If one of the goals of hearing health is to support consumers to start managing hearing issues earlier, rather than waiting for relationship breakdowns and physical changes or the reported 8.9-year wait for hearing aid adoption, 3 we need to understand what motivates our consumers to initiate change, and how to harness this in a feedback loop to support their psychosocial states.

Currently, we understand that audiometric measurements alone are not enough for the consumer to adopt hearing rehabilitation 32 and the World Health Organization published the World Report on Hearing stating the “… PTA assessment should not be the sole determinant for rehabilitation, mainly because audiometric shifts do not provide information on how sounds are processed by the central auditory system, and therefore offer only limited insight into “real-world” functioning.” 11

Additionally, we know that hearing health requires an up skill period for consumers to understand their hearing issues, loss or needs, and process the emotional cycles that may come prior to acceptance of their loss. Not only do clinicians need to consider the emotional response of the consumer, for example, motivation, attitude, change behaviors, and/or grief, but they also need to account for their physical changes, which can include changes in dexterity, cognition, and/or vision. How to manage the device, how to care for the device, and how to use an application interface to get the most out of the device and the consumer are all changing facets that hearing health care professionals need to navigate. If consumers are going to manage hearing loss in a successful, long-term manner, clinicians must support them to do so in a continued and long-term manner. This may mean a shift in how we currently practice hearing rehabilitation, to one that incorporates more continuous data input and on the spot feedback from consumers, with expectations that match how the consumer expects the healthcare professional to delivery services. 33 Specifically, consumers will not be limited to traditional appointment structures or a 9-to-5 schedule to obtain updates or feedback on their devices or situations they are in, rather the data clinicians will receive will allow dynamic, personalized feedback to the consumer, and perhaps in a real-time manner (synchronous). These changes speak to the recognition and drive to support person-centered standards of care that are fundamental to improving outcomes in chronic health management like hearing care. 5 6 34 35 The consumer does not experience their hearing loss or interaction with their hearing device in a compartmentalized way that health and other appointments are typically experienced. Instead, the hearing loss experience is an integral part of day-to-day life. Adapting hearing care to acknowledge this reality for consumers is a step that can hopefully improve consumer engagement, attitude, and action toward and into hearing care. A one-size-fits-all model of care has served only a certain population and the time has come to undergo changes to meet the new demands of healthcare.

Further, when considering health behavior theories and models in clients, we understand that the healthcare journey is a dynamic one where clients with the same audiometric thresholds will display varying degrees of psychological differences and levels of readiness. 36 37 The predominant one size fits all of service delivery offering and fitting appointment does not account for the varying degrees of psychological differences nor readiness of clients. For hearing healthcare to be successful for all parties involved, the following should be considered; the language of the clinic must reflect the purpose of the appointment, and the value that is imparted must be understood and implemented by the client and their support networks. As the technology components evolve, the style in which feedback is received/imparted from both parties should take on dynamic and real-time approach. This means that instead of the client waiting to see the clinician in a few days or weeks, the client gets feedback either instantaneously or within 24 hours. This model of dynamic care allows timely resolution of issues or clarification, and it keeps clients engaged. Online models of hearing care and device provision have adopted flexibility in their support provision to their own success. 27 28 Hearables are not typically offered with service models that are comprehensive as hearing aid support service models. It can be argued, however, that hearables tend to have a greater focus on preemptively addressing support needs compared with hearing aid provision that historically adopts a reactive approach to support needs for the consumer. Both approaches will certainly have advantages and disadvantages in attaining and maintaining consumer engagement in hearing care. Learning from both could be our smartest move yet.

When we look at research around successful weight loss using a digital therapeutic that is developed around psychological and behavioral sciences, we see a higher success rate with better commitment to a program in the long term, compared with those who did not utilize this model of care. 38 39 Like hearing health outcomes, there is a large degree of variability in weight loss outcomes, and service offerings and models of care need to reflect or provide these options for consumers.

The predominate models of hearing healthcare fail to meet a lot of consumer needs. Hearing models of care need to complement and support one another, that is, our models of care need to provide optionality for where, when, and how consumers want to interact with their healthcare professional and services. The traditional model of care does work for some consumers; however, there is a large portion of the population this does not support.

Combined with the convergence of medical and consumer grade devices, availability of services and client's desire to collect healthcare data through wearable accessories and applications has seen a shift in how healthcare is accessed and understood.

At the convergence of these realms for hearing healthcare, we are yet to see the full fruition of how hearing health can be managed by the consumer or clinician to address varying degrees of change that need to take place. For example, clinicians want to see clients use their hearing aids all day. We know that 1 to 2 hours is not enough to gain the full benefits of all day hearing aid use. Furthermore, research shows that when clients use their hearing aids, the benefits they receive and perceive improve their quality of life.

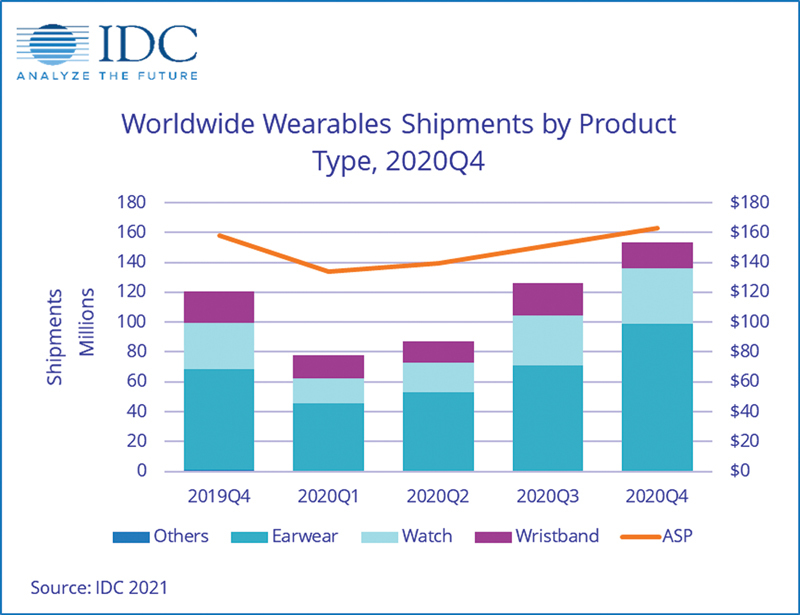

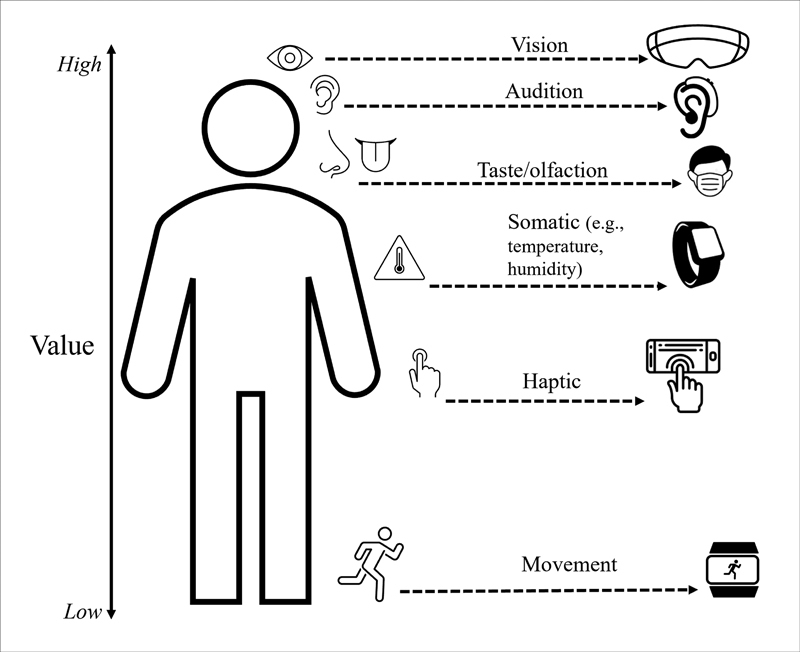

Whether we professionally agree with these changes across the technology landscape and the changes we hope to see in behaviors, we can see that the trend in consumers purchasing wearables devices is increasing as shown in Fig. 1 . Wearable devices have expanded in application to now cater for all sensory areas (see Fig. 2 ). The growing applications and popularity of wearables for sensory support are encouraging; how we can learn from the successes of wearables to address challenges seen in hearing care thus far provides an exciting opportunity as we continue to innovate and adapt what hearing care can offer.

Figure 1.

Trends wearable product type 2019–2020. 40

Figure 2.

Applications and wearable devices used for “Quantified-Self.” 41

The Consumer

Consumers of hearing healthcare have traditionally been limited in how they seek and access services and products to support their hearing health rehabilitation. Until the last decade, it has not been uncommon for consumers to only have access to bricks and mortar or retail outlets to support their hearing health needs. As a result of this structure of hearing health service and product offerings, it can be deduced, with many other factors contributing toward this, that consumers are more likely to postpone hearing health interventions and cope or suffer with their hearing loss. 42

Further to this postponement, social stigma, reduced self-efficacy, the lack of convenience and distance to accessing a clinic, lack of value placed on hearing issues and loss, lack of perceived communication issues correctly identified, the cost of hearing devices, and consumers reporting a disconnect in their experience of clinical encounters as a series of isolated events rather than a cohesive, holistic approach to achieving their goal(s) 43 44 are well documented and all contribute to delays in hearing health management. 45

While we understand some of the barriers to adoption and use of hearing device and hearing health management, we do not understand the nuances of the postponement when it comes to continued hearing health management. Further to this, we can identify factors such as those discussed earlier and in this article, DTC and over the counter (OTC) options will potentially be adding as an opportunity to gain more data and understand consumers and their healthcare drivers. The potential for such learning is particularly true for those consumers in the hearables or personal sound amplification product (PSAP) categories and those who by-pass any professional interaction. 12 43 45

With the introduction of hearables/PSAP by consumer electronics companies to the hearing health industry, we can expect to see a shift in the perception of wearing hearing devices on and around the ears for prolonged periods of time 46 ; however, what we do not yet know is if:

Hearables are enough to motivate consumers toward managing their hearing health status in the longer term or when their hearing gets worse. Given the DTC pathway of these devices, is this enough for consumers to begin their hearing health journey earlier, and stick with it? The most recent MarkeTrak survey of U.S. citizens showed the number of years to seek professional help/advice when noticing hearing difficulties had decreased from an initial estimate of 6 years to 4 years 46 ; however, device acquisition still showed a lag time.

Consumer devices or applications are a gateway product to professional hearing health services and fitting of hearing aids?

The consumer understands the importance of hearing health interventions and support.

The professionals understand the importance of offering varying degrees of solutions (apps, hearables, or assisted listening devices) in lieu of hearing aids, to support hearing loss.

From a professional perspective, the desired outcome is to ensure consumers are getting the most out of their hearing health rehabilitation and understanding the implications of not managing hearing loss or hearing issues. While we act to uphold high-quality services in hearing healthcare, this is not always the case nor is it one the consumer may be ready to act upon. The hearables/PSAP landscape is changing and challenging the language and how consumers may choose to interact with hearing healthcare. 12 46

However, much like real ear measurements and optimizing application interfaces to ensure the consumer has the best, optimal benefit or satisfactory outcomes are not always achieved. Considering a solution that addresses some of a consumer's hearing loss needs but does so successfully, while nurturing a positive relationship between the consumer and their hearing care, may be better than delaying the optimal solution. Managing hearing loss as soon as possible to combat any long-term issues associated with cognition and use of hearing device uptake and quality of life may provide the consumer with a better hearing health outcome than what is traditionally available. MarkeTrak 2022 showed that American consumers were addressing hearing difficulties earlier, some with PSAP devices; however, this survey also showed a difference in satisfaction rates between a PSAP and hearing aid. 47 PSAPs were shown to have a lower satisfaction rate when compared with those who had hearing aids, 66 and 83%, respectively, 46 which lends the discussion to the following questions:

Essentially, we want to know if the trade-off between “some device use,” like a hearable/PSAP, is a better trade off then no device use? The risks and benefits, most importantly for the long-term outcomes, of the consumer must be investigated.

Can these devices be an entry level solution provided by a hearing professional to allow the consumer to learn and understand the benefits of a professional consult? While relationship between the consumer and the clinician is evolving to be consumer led, the relationship, and engagement, between the consumer and their hearing device is and should remain the focus of what we want to learn about and better support.

The Service

As hearing aids and hearables start to converge between features and between each other, for both product and attainability, we also need to understand how the provision of services can evolve to meet the needs of consumers. Until the pandemic began to significantly impact our lives in early 2020, a shift in the point of hearing healthcare has been stagnant and despite evidence mounting in the provision of teleaudiology services and telehealth across healthcare fields, the uptake to delivering these services by healthcare professionals remains low. 48 A similar argument can also be used for the consumer; however, healthcare professionals have a duty of care and responsibility to the consumer to ensure they advocate and offer the most accessible services and products. There is always a level of up skilling or education in any behavioral change component, and as professionals, the duty of care does reside with us. Consider the following:

The product alone has not served to meet the needs of those with hearing loss across the spectrum of hearing difficulties, with research showing us that counseling and coaching of the client contributes to the success of hearing aid uptake and continued use. 12 49

The types of assessments conducted are limited in helping consumers achieve real-world outcomes. For example, we assess hearing thresholds in quiet to gain the quietest thresholds a consumer can functionally hear; however, we do not assess their hearing ability against their largest complaint or issue, listening in background noise or competing noises. Word or sentence recognition in competing sounds is an evidenced-based starting point, but what about real-world feedback where the consumer can accurately, and in a timely manner, input their complaints and gain real-world feedback, through an Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) tool or other, to allow hearing healthcare professionals to quickly remediate against real-time data/complaints. 50 51 As healthcare professionals, we should also aim to assess functional (or real-world) hearing, for example, how individuals hear in background noise in real-world environments, not just the limited clinical hearing standards.

Client goals or the feedback loop of accomplishment is seldom explained to clients or the significant communication partners in detail or closed. For example, we set client goals using a Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) or the Hearing Handicap Inventory Elderly/Adults (HHIE/A), but continued tracking of measuring goals outside of funding requirements may not be treated with the intention of continued, supported, and engaged levels of hearing rehabilitation. The systems we work within are a reactive approach to hearing health.

Transparency and clearly communicated and itemized invoices for what the consumer is paying for. The argument here is not only applicable to hearing healthcare but also a common issue across healthcare professionals, especially when there are numerous services being delivered. What makes it unique in hearing health is the bundling of services to a product without a clearly visible delineation between either.

These concepts are not new, with a few change makers paving the way for the above to happen, Blamey Saunders Hears (launched in 2008) is an example of services and products addressing the above. 28 What is changing is the level of information the consumer has access to, the age of the consumer, and the increase in personalized data across healthcare.

It might not be that a momentous change comes from within the hearing health sector, but a fresh look at solving the hearing aid acquisition age and access to modern, inclusive, and dynamic audiological services forces change and disrupts the siloed entities or predominant models.

The System: Patient-Centered Care versus Consumerism

It can be argued that radical change needs to occur outside a system for the system to catch up. When we reflect upon changes in government, it is evident that voters will largely vote for the improvement of economic and societal changes. If we observe what happens in technologies, an idea that may seem outrageous seems to win out in the long run. A long-standing example is the idea of a minicomputer in your hands (smartphone) or the idea that you can listen to music via mp4 files.

When it comes to healthcare, professionals typically believe that the behaviors of clients are driven by a patriarchal or traditional approach, where the client must come to us, a professional, to seek care. However, consumerism and technological changes occur to challenge the predominate status quo, and aims to liberate or allow optionality, the locus of control and convenience to be placed back into the hands of the consumer. 52 Essentially, if the technologies and user experience are created well what we witness is a shift from a reactive system of healthcare to a more proactive, early intervention-based model of care. It must be cautioned that while this theory is yet to be researched and proved in the hearables space, there could also be a trap that clients are under-fitted and remain in this below optimum pathway.

Platform and Tools

As the digital revolution expands and the global pandemic of corona virus ushers the acceptance of and uptake of telehealth services to clients and clinicians, subsequently, digital healthcare products and services become more understood, trusted, and utilized by the population. This means that consumers are wearing and using more accessories to capture healthcare data over a longer set of time, with the possibility of service opportunities becoming infinite for healthcare professionals and consumers.

Similarly, systemic changes in Australia are occurring: notably the introduction of government-funded telehealth appointments. 53 54 Initially, these rebates were introduced in a temporary capacity; however, the uptake and feedback of these item numbers have proven to be safe, effective, and an accessible form of healthcare delivery, becoming permanent fixtures on the schedule in Australia. 53

This may not be indicative of other countries that offer government-funded healthcare services. For example, telehealth has been available in the United Kingdom to citizens prior to the pandemic, with costs covered by the NHS. 55

Not only do factors of convenience and cost influence the accessibility of services, reliability of internet connections and use of smart devices also contribute to the rapid acceptance of accessing healthcare services online. Given that most people own a smart device capable of accepting calls, text, or video calls, the offering of an alternative with a traditional model of care can be straightforward to implement for all parties involved.

As systems change and attitudes toward these types of services change, the available tools that clinicians and consumers can access will also improve and drive the change in healthcare delivery to be more consumer centric, with consumers choosing how and when they are accessing hearing health services. At the same time, the method in which hearing healthcare professionals can deliver services and program hearing products will also improve. Many of these factors have already converged, with hearing aid manufacturers offering remote programming to products via software platforms. Holder et al thoroughly discuss the various remote technologies currently available for audiological care, demonstrating just how prepared our industry is, regardless of whether we are choosing to use the tools therein. 56

Data-Driven Hearing Healthcare

With the new age of healthcare including more digital tools, biometrics and personal information being captured by devices, this should lead to an evolution of our professional services, in turn leading to a behavioral change for consumers. We cannot dismiss the value of the data being collected and how this can impact shaping our behaviors as clinicians or our consumers' behavior when it comes to healthcare change.

Understanding what data these devices are capturing, who owns this data and the intent of the data captured, is a crucial point of consideration. Data management and compliance for the systems that manage and utilize any consumer collected has also grown in responsibility and stringency as the device capabilities have adapted to online accessibility. Further to this, in the last decade, the type of data being collected has evolved; for example, with hearing aids, numerous forms of data are now commonly logged, adding more complexity to how these data are collected, consented to, and used (e.g., data logging, scenarios client spends time in, use of settings, and some even log biometrics). As this area continues to grow with data being pushed to the cloud and accessed via remote functionality, professionals need to understand the implications of this and how it can impact their clients' behaviors. For example, how and what settings the client use their hearing devices, fluctuations in biometric statistics and exposure to loud noises over periods of time, will allow clinicians to gain more meaningful insights into the landscapes and lifestyles of consumers. Thus, leading to a change in professional service delivery, for example, synchronous (real-time feedback) or asynchronous (delayed feedback) with longitudinal, personalized data that can inform the clinician/client of changes that can be made immediately or in a delayed sense. The potential of the data at hand leads to greater opportunity to maintain supportive and engaged hearing care provision in line with individual consumer needs.

Data mining is not necessarily an evil adage if collected for the intent of improving services and experiences; however, it does become a cause for concern when being mined for reasons that are not transparent, or ethical, for example, exclusionary insurances. Insurance companies or the like should not be utilizing personalized or mined data for cherry picking consumers. Simply put, it is unethical and, in some countries, illegal, to exclude consumers from services based on data mined. 57 To be clear, data mining is not a new concept. It has been used in industries such as marketing and finance for years to change the behaviors of consumers. The question clinicians should consider is, what is my duty of care when it comes to accessing personalized data for consumers.

With the increase in device use, it is important as a healthcare professional to know how our role fits into this realm. If we are not planning to leverage all the tools and resources available to improve our client's quality of hearing and life, then are we saying that the status quo is good enough?

As data capture and automation of clinical practices improves, the new role of the hearing health professional may focus on counseling with the data available to them, less time reaching targets with hearing aid fittings, and more time spent educating and building confidence in client's skills to manage hearing devices and communication strategies. This should not come as a surprise given the increasing evidence to support a professional level of involvement for a client with either a consumer or medical grade device. 58

Summary

A perfect storm is brewing with the possibilities of:

Truly personalized client-centered care, with consumers engaging and leading their hearing health journey through improved device accessibility and data collection.

Rather than being clinician-led, hearing health professionals embellish a coaching role in solving client issues, guiding clients, and adapting their professional behaviors to support the client in a timely manner or as the client chooses.

Increased and improved use of hearing health data and how this is imparted to consumers.

With the convergence of consumer and medical grade devices rapidly occurring, consumer attitudes and knowledge toward healthcare is also changing, placing demand on a more consumer-led, personalized, and accessible level of care that goes beyond traditional healthcare models. Ideally, these will all lead to favorable outcomes for those involved in the hearing health journey and, if not, there is a solution to support change in an improved manner.

Systemic changes will need to evolve to ensure data collection and use is safe and used in a way that all parties understand and agree to. Not to mention funding models will need to adapt policies and models appropriately to support client-driven outcomes over numerically led measures. Like behavioral and systemic changes, funding and legislative changes can fail to keep up with technological advances. Overtime, these systems in which we practice will be subject to further scrutiny and updates.

As hearing devices and professional hearing health services continue to face changes, it is important to remember that we have the tools available to improve all aspects of our professional delivery today. As a healthcare professional, the key driver to engaging a consumer is the relationship and trust that is established. For example, clinics could be utilizing an e-commerce strategy to supply several consumer grade devices; hearables, hearing protection and attenuators and applications, evidence-based content, while also providing a clear service strategy that allows the client to select a product and/or service that works for them, can easily be set up. Relationships are built in numerous ways in the digital world and translate into clinical ones quite smoothly. Client expectations can be set prior to a client coming to an appointment and this has large psychological benefits.

Simply relying on the adage of hoping things will change and not enacting them will not change the status quo. If the status quo of servicing a select population with certain types of hearing issues/losses is the goal, then the predominate model of hearing health care does suffice. The real question is, is it good enough and will it survive.

Understanding how to engage with the hearing health consumer and keep this engagement is a key driver to the behavior change we are seeking to impart for long-term success, and with the sections highlighting the changes in the technology, the consumer and the hearing health landscape, it is evident that a perfect storm of change is going to occur.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the editors for their very helpful suggestions for improving our manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST J.A.Z. is employed by Sonova Audiological Care Australia.

K.A.P is employed by Nuheara.

References

- 1.McCormack A, Fortnum H. Why do people fitted with hearing aids not wear them? Int J Audiol. 2013;52(05):360–368. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.769066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis A, Ferguson M, Stephens D, Gianopoulos I.Acceptability, Benefit and Costs of Early Screening for Hearing Disability: A Study of Potential Screening Tests and ModelsNIHR 2007 contract no. 42 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Simpson A N, Matthews L J, Cassarly C, Dubno J R. Time from hearing aid candidacy to hearing aid adoption: a longitudinal cohort study. Ear Hear. 2019;40(03):468–476. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krist A H, Tong S T, Aycock R A, Longo D R. Engaging patients in decision-making and behavior change to promote prevention. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;240:284–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark N M, Becker M H, Janz N K, Lorig K, Rakowski W, Anderson L. Self-management of chronic disease by older adults: a review and questions for research. J Aging Health. 1991;3(01):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner E H, Austin B T, Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Manag Care Q. 1996;4(02):12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NICE Glossary NICE [webpage]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). no date [updated 2022; cited August 4, 2022]. Accessed May 15, 2023 at:https://www.nice.org.uk/glossary?letter=q

- 8.Dillon H, Day J, Bant S, Munro K J. Adoption, use and non-use of hearing aids: a robust estimate based on Welsh national survey statistics. Int J Audiol. 2020;59(08):567–573. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1773550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irace A L, Armstrong N M, Deal J A. Longitudinal associations of subclinical hearing loss with cognitive decline. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77(03):623–631. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glab263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golub J, Brickman A, Schupf C A, Luchsinger J. Association of subclinical hearing loss with cognitive performance. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;146(01):57–67. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO World Report on HearingGeneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization March 2021

- 12.Edwards B. Emerging technologies, market segments, and MarkeTrak 10 insights in hearing health technology. Semin Hear. 2020;41(01):37–54. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1701244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keidser G, Dillon H, Flax M, Ching T, Brewer S. The NAL-NL2 prescription procedure. Audiology Res. 2011;1(01):e24. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2011.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zakis J A, Hau J, Blamey P J. Environmental noise reduction configuration: Effects on preferences, satisfaction, and speech understanding. Int J Audiol. 2009;48(12):853–867. doi: 10.3109/14992020903131117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung K, McKibben N, Mongeau L. Wind noise in hearing aids with directional and omnidirectional microphones: polar characteristics of custom-made hearing aids. J Acoust Soc Am. 2010;127(04):2529–2542. doi: 10.1121/1.3277222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zakis J A, Hawkins D J. Wind noise within and across behind-the-ear and miniature behind-the-ear hearing aids. J Acoust Soc Am. 2015;138(04):2291–2300. doi: 10.1121/1.4931442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zakis J A. Wind noise at microphones within and across hearing aids at wind speeds below and above microphone saturation. J Acoust Soc Am. 2011;129(06):3897–3907. doi: 10.1121/1.3578453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humes L E, Rogers S E, Quigley T M, Main A K, Kinney D L, Herring C. The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Audiol. 2017;26(01):53–79. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smits C, Kapteyn T S, Houtgast T. Development and validation of an automatic speech-in-noise screening test by telephone. Int J Audiol. 2004;43(01):15–28. doi: 10.1080/14992020400050004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillon H, Beach E F, Seymour J, Carter L, Golding M. Development of Telscreen: a telephone-based speech-in-noise hearing screening test with a novel masking noise and scoring procedure. Int J Audiol. 2016;55(08):463–471. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2016.1172268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson C S, Kidd G R, Miller J D, Smits C, Humes L E. Telephone screening tests for functionally impaired hearing: current use in seven countries and development of a US version. J Am Acad Audiol. 2012;23(10):757–767. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.10.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honeth L, Bexelius C, Eriksson M. An internet-based hearing test for simple audiometry in nonclinical settings: preliminary validation and proof of principle. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(05):708–714. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181de467a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blamey P. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2019. The expected benefit of hearing aids in quiet as a function of hearing thresholds; pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blamey P, Saunders E. Predicting speech perception from the audiogram and vice versa. Canadian Audiologist. 2015;2(01):x. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smits C, Merkus P, Houtgast T. How we do it: the Dutch functional hearing-screening tests by telephone and internet. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31(05):436–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blamey P J, Blamey J K, Saunders E. Effectiveness of a teleaudiology approach to hearing aid fitting. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(08):474–478. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15611568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrams H B, Singh J. Preserving the role of the audiologist in a clinical technology, consumer channel, clinical service model of hearing healthcare. Semin Hear. 2023;44(03):302–318. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1769627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckett R, Blamey B, Saunders S. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2016. Optimizing hearing aid utilisation using telemedicine tools. Encyclopedia of e-Health and Telemedicine; pp. 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shub D E, Makashay M J, Brungart D S. Predicting speech-in-noise deficits from the audiogram. 2020;41(01):39–54. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humes L E. The contributions of audibility and cognitive factors to the benefit provided by amplified speech to older adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18(07):590–603. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.18.7.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders E, Brice S, Alimoradian R. IGI Global; 2019. Goldstein and Stephens revisited and extended to a telehealth model of hearing aid optimization; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angara P, Tsang D C, Hoffer M E, Snapp H A. Self-perceived hearing status creates an unrealized barrier to hearing healthcare utilization. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(01):E289–E295. doi: 10.1002/lary.28604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glista D, Schnittker J, Brice S. The modern hearing care landscape: towards the provision of personalized, dynamic, and adaptive care. Semin Hear. 2023;44(03):261–273. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1769621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Audiology Australia . Melbourne, Australia: Audiology Australia Ltd; 2022. National Competency Standards for Audiologists; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Convery E, Hickson L, Keidser G, Meyer C. The Chronic Care Model and chronic condition self-management: an introduction for audiologists. Semin Hear. 2019;40(01):7–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders G H, Frederick M T, Silverman S C, Nielsen C, Laplante-Lévesque A. Health behavior theories as predictors of hearing-aid uptake and outcomes. Int J Audiol. 2016;55 03:S59–S68. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2016.1144240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards B, Ferguson M. Understanding hearing aid rejection and opportunities for OTC using the COM-B model. The Hearing Review. 2020;27(06):12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell E S, Yang Q, Behr H. Psychosocial characteristics by weight loss and engagement in a digital intervention supporting self-management of weight. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(04):1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carey A, Yang Q, DeLuca L, Toro-Ramos T, Kim Y, Michaelides A. The relationship between weight loss outcomes and engagement in a mobile behavioral change intervention: retrospective analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(11):e30622. doi: 10.2196/30622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Needham M.Consumer Enthusiasm for Wearable Devices Drives the Market to 28.4% Growth in 2020, According to IDC; 2022 [updated 15 March 2021Accessed May 15, 2023 at::https://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=prUS47534521

- 41.Choe Y, Fesenmaier D R.The Quantified Traveler: Implications for Smart Tourism DevelopmentAnalytics in Smart Tourism Design. Tourism on the Verge;201765–77. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amlani A M. Effect of determinants of health on the hearing care framework: an economic perspective. Semin Hear. 2023;44(03):232–260. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1769611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valente M, Amlani A M. Cost as a barrier for hearing aid adoption. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(07):647–648. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laplante-Lévesque A, Knudsen L V, Preminger J E. Hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation: perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. Int J Audiol. 2012;51(02):93–102. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2011.606284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Debevc M, Zmavc M, Boretzki M.Effectiveness of a self-fitting tool for user-driven fitting of hearing aidsInt J Environmental Research Publich Health 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Powers T A, Carr K. The Hearing Review; 2022. MarkeTrak 2022: Navigating the Changing Landscape of Hearing Healthcare. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powers T, Carr A. MarkeTrak 2022: naviagting the changing landscape of hearing healthcare. Hearing Review. 2022;29(05):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eikelboom R H, Bennett R J, Manchaiah V. International survey of audiologists during the COVID-19 pandemic: use of and attitudes to telehealth. Int J Audiol. 2022;61(04):283–292. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1957160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gotowiec S, Larsson J, Incerti P. Understanding patient empowerment along the hearing health journey. Int J Audiol. 2022;61(02):148–158. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1915509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Timmer B HB, Hickson L, Launer S. The use of ecological momentary assessment in hearing research and future clinical applications. Hear Res. 2018;369:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jenstad L M, Singh G, Boretzki M. Ecological momentary assessment: a field evaluation of subjective ratings of speech in noise. Ear Hear. 2021;42(06):1770–1781. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Latimer T, Roscamp J, Papanikitas A. The Royal Society of Medicine; 2017. Patient-Centredness and Consumerism in Healthcare: An Ideological Mess; pp. 425–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MBS Online. MBS Telehealth Services from January 2022; Factsheets on ongoing MBS Telehealth Arrangements: Australian Government: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2022 [updated April 11, 2022]. Accessed May 15, 2023 at::http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Factsheet-Telehealth-Arrangements-Jan22

- 54.Hearing Services Program Provider Factsheet - Telehealth in the Program Australian Government: Department of Health. No Date [cited 2022]. Accessed May 15, 2023 at: https://hearingservices.gov.au/wps/portal/hso/site/prof/deliveringservices/provider_factsheets/provider%20factsheet%20-%20telehealth%20in%20the%20program/!ut/p/z0/jY7BTsMwEER_xRxyrNZEoeIaIRXR0FYcQMGXyE038baundpLgL_H7YFWAiEuK83b0cyAghqU0yP1msk7bZN-VdOmerqZXj_IvLp9Wc1kWS6fH-ezIpf3BcxB_W1ICbQ9HFQJqvWO8YOhNtGLk3CcyeFtbanNpPF7TBd1INc3Q_AdxnhaETO5QUsjHj8Rw0gtJpYsI20wNJ1uORpEvoDiG4qJYLSYgi0bQU6wQZFsfdD747o8LO4WPahBs5mQ6zzUP9ug_qXtDP_ZNuzU-vO9vPoClFj0bQ!!/.]

- 55.DLA Piper. Telehealth around the world: A global guide, 2020. [cited 2022]. Accessed May 15, 2023 at:https://www.dlapiper.com/~/media/files/insights/publications/2020/12/dla-piper-global-telehealth-guide-december-2020.pdf

- 56.Ferguson M, Sucher C M, Maidment D, Bennett R, Eikelboom R. Remote technologies to enhance service delivery for adults: clinical research perspectives. Semin Hear. 2023;44(03):328–350. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1769742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Saggaf Y. Bioethics and Information Technology; 2015. The Use of Data Mining by Private Health Insurance Companies and Customers' Privacy; pp. 281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Convery E, Keidser G, Hickson L, Meyer C. Factors associated with successful setup of a self-fitting hearing aid and the need for personalized support. Ear Hear. 2019;40(04):794–804. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]