Abstract

Hearing care is expanding accessibility to consumers through new service delivery channels and methods of technology distribution (see Brice et al, this issue). This diversification has the potential to overcome longstanding consumer disparities (e.g., health, socioeconomic, psychological, environmental) in receiving care and provider constraints (e.g., accessibility, geography, direct access) to delivering care that adversely impacts quality of life (e.g., social isolation, depression, anxiety, self-esteem). In this article, the reader is provided with an overview of health outcomes factors (i.e., determinants of health)—in the context of an economic framework (i.e., supply, demand)—and their effect on consumer behavior and provider preferences toward hearing healthcare services. This overview also affords readers with strategic business insights to assess and integrate future hearing care services and technology to consumers in their local markets.

Keywords: audiology, determinants of health, healthcare consumerism, quality of life

The primary role of audiology is to assess hearing status, diagnose auditory and balance system disorders, and treat hearing loss. For the treatment of hearing loss, the objective of hearing care is to provide professional services—augmented by advancements in technology offerings—that are accessible and meet the demands of consumers in improving their quality of life (QoL). 1 Over the past two decades, much of the advancement in hearing care has stemmed from developments in hearing aid technology. 2 Consider, for example, the availability of sophisticated signal processing features, such as directional microphones, adaptive compression, feedback cancellation, and noise reduction known primarily to restore the audibility of sounds that result in improved speech perception. 3 Secondary benefits from these signal processing features include reduced cognitive load, decreased auditory fatigue, and improved social engagement. 4 5 Recently, the advent of streaming sound and wireless connectivity between hearing aids and consumer electronic products to smartphones has provided the user with greater control over their listening preferences. 2 6

Developments in technology have enhanced innovative business model opportunities and new hearing care market segments that extend beyond the traditional brick-and-mortar setting (see Brice and colleagues, this issue 7 ). From a healthcare standpoint, these new opportunities and segments underscore the full potential of hearing care in improving the overall well-being (i.e., physical, psychological, functional, social) and QoL for people experiencing sensory loss and perceptual difficulties. 8 9 10 While these new developments imply modernization, healthcare, in general, is challenged by economization. Consider that clinical care accounts for ≤ 20% of the modifiable contributors to healthy outcomes, 11 yet is often one of government's largest expenditures. In 2020, national health expenditures for the United States, for instance, accounted for 18.8% of the gross domestic product (GDP), or an average of nearly 6.5% above what a comparable developed country spent on healthcare relative to its GDP. 12

The remaining ≥ 80% of modifiable contributors to healthy outcomes are broadly termed determinants of health (DoH) and are defined by the relationship between health status and QoL factors. QoL factors include health behaviors (e.g., diet, exercise, tobacco use, alcohol, and drug use), social and economic factors (e.g., employment status, income, education, family and social support), and physical environment (e.g., housing status, transportation, air and water quality). Given the high percentage contribution of modifiable DoH factors to healthy outcomes, there is an increasing governance of economic reasoning toward evaluating and accessing services and interventions through self-efficacy, self-responsibility, and financial incentives. This governance has induced healthcare consumerism , with the primary goal of improving service delivery through increased patient-centeredness, reliability, and accessibility. 13 Clearly, today's consumers are shouldering greater responsibility for their own healthcare and are being asked to make increased decisions regarding their well-being needs than in the past. As a result, the consumer is no longer a passive recipient when it comes to health-related well-being.

Prior to the COVID-19 global pandemic, consumers were eager for autonomy and convenience toward their health care needs. Since the global pandemic, consumer behavior has expanded such that there is an increased receptiveness to adopting in-home alternatives, and a shift toward online and omnichannel engagement. 14 This newfound consumer behavior has public health and economic implications for the hearing care space. That is, providers must be responsive to DoH factors that allow for innovative service delivery opportunities to promote value to consumers in at least two ways: (1) a reduction in barriers to the current, archaic, and encumbered consumer hearing care journey and (2) an improvement in efficient, accessible, and affordable services that yield positive treatment outcomes. Those providers that fail to acknowledge and address the changing healthcare landscape face the potential risk of a reduction in demand not only for their services but also the potential for a reduction in demand toward service provision offered by the profession of audiology. Stated differently, the reduction in demand will result in lost revenue at the level of the provider and, further, has the potential to increase subjugation on scope of practice by competing healthcare professions and automations in technology.

In this issue of Seminars in Hearing , Brice and colleagues 7 provide readers with a framework that identified eight archetypes of solutions within hearing care based on the three core domains of (1) Service, (2) Technology/Device, and (3) Channel. These authors further note that consumers have distinct options in treating and managing their hearing-related needs with respect to (1) who will supply their services, (2) the type and level of technology/device they will adopt and use, and (3) the channel that they will obtain services and technology. The present article provides the reader with an overview—using an economic framework—of the contributing DoH factors and how these factors effect consumer behavior and preferences toward the pursuit of hearing healthcare services.

METHODS

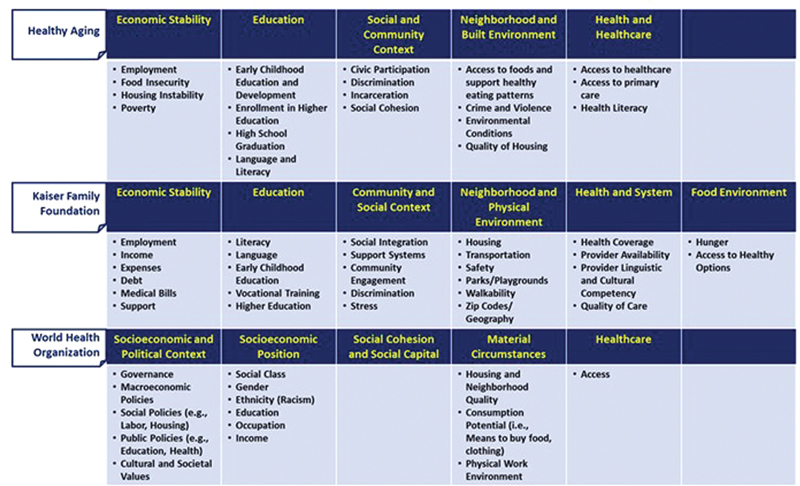

In this article, hearing health service delivery is expressed as the interaction between the characteristics of providers and the characteristics and expectations of the consumer. To define this relationship, the author identified mediating a factors by referencing existing DoH frameworks. These frameworks included (1) Health People 2030, 15 16 (2) the Kaiser Family Foundation Social Determinants of Health factors, 17 and (3) the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 18 Fig. 1 displays the respective domains and determinants (i.e., factors) for each of the three referenced frameworks.

Figure 1.

Reporting of determinants of health among three existing frameworks: the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health People 2030, the Kaiser Family Foundation Social Determinants of Health, and the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health.

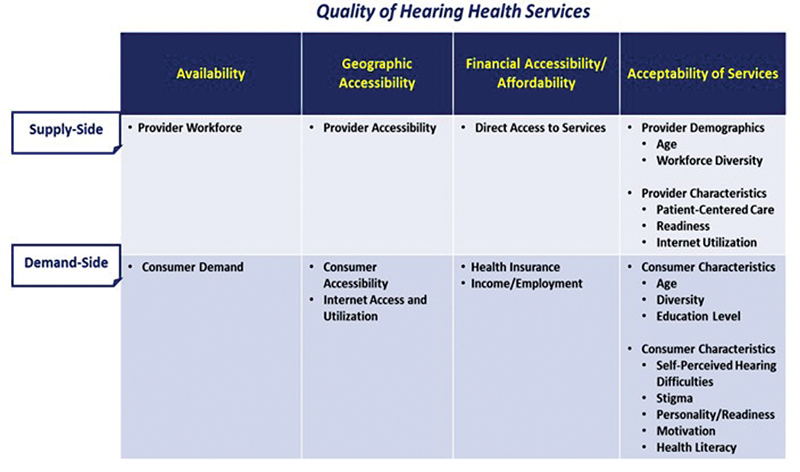

Next, the hearing healthcare utility (i.e., access) of these mediating factors was categorized as a function of supply and demand. 19 Supply-side determinants to the health system serve as a conduit to service and product uptake by an individual, household, or community, while demand-side determinants are factors that influence the ability of the individual, household, or community to acquire the available services and product.

Lastly, a model of access to care was incorporated from Peters and colleagues. 20 This model is based on the quality of health services provided and how these provisions are utilized by providers and consumers in four dimensions:

Availability—Supply of services—such as provider competency, hours of operation, and models of care—that meet the needs of consumer demand.

Geographic accessibility—The physical distance or transportation time between the point of service delivery and the consumer.

Financial accessibility—The relationship between the price of services, as determined by their costs, and the willingness and ability of consumers to pay for those services while being protected from the economic consequences of health costs.

Acceptability of services—The match between how responsive healthcare providers and consumers are to the social and cultural expectations of one another.

Together, these exercises provided guidance in convening a construct of domains and factors (i.e., DoH)—with respect to access to care—that have the potential to influence consumer behavior toward hearing care professional services and products from a supply and demand perspective, as shown in Fig. 2 . At the conclusion of the respective supply- and demand-side perspective, the reader is provided a summary of findings for the domains and factors, followed by a discussion on the application of these findings to the framework proposed by Brice and colleagues. 7

Figure 2.

Construct of determinants of health domains and factors that influence consumer behavior in hearing healthcare, dichotomized by supply and demand.

DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Supply-Side Factors

Availability

Professional Workforce

The global supply of audiologists to provide hearing care services is understaffed. 21 In the United States, Bray and Amlani, 22 using the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) database, revealed an estimated workforce of 12,950 audiologists in 1999. In 2019, the supply of audiologists reported by BLS yielded a workforce only of 13,590. During this 20-year period, the audiology workforce grew by a mere 5%. Over this same period, 19 comparable health professions reported an average workforce growth rate of 46%, while the professions of speech-language pathology, optometry, and physical therapy increased their respective workforce by nearly 80%.

The growth rate in audiology does not appear to be improving as survey data of audiology enrollment and today's graduation rates remain comparable to pre-doctoral level historical rates (i.e., roughly 700 graduates annually), signifying a continued future supply shortage in workforce to meet the growing rate of individuals experiencing hearing loss. 23 24 Reasons for the limited growth in audiology workforce are attributed to a combination of retirements, deaths, and abandonment of the profession. 22 23

Geographic Accessibility

Geographic accessibility, in healthcare, is primarily a supply-side issue that effects the ability of consumers to utilize in-person services relative to distance, transportation, and other physical challenges. Consumer access to in-person professional services is inversely related to distance or travel time to the healthcare facility and serves as a deterrent to improving QoL. 25

Metropolitan and Urban Areas

With respect to hearing care, Planey 26 reports that U.S. audiologists are located mostly in metropolitan counties having higher median household incomes and younger populations, coupled with a lower proportion of older adults reporting hearing difficulties. In addition, these audiologists were also less likely to be located in states that have legislation requiring insurance coverage of audiology services.

Rural Areas

Rural residents—many of whom are older adults and have an increased preponderance toward hearing difficulties—must travel a farther distance or experience longer travel times to access in-person hearing care compared with their peers residing in metropolitan counties. 27 28 Outcomes of the geographical disparity is that rural residents have their hearing assessed less regularly and that hearing aid provision is lower than their urban counterparts. 28 29 30 Research further indicates that a large share of rural counties, where audiology services are considerably absent, are also states whose Medicaid b programs cover audiology services for adult beneficiaries. 26

In addition, older adults with hearing loss residing in rural areas face limited direct access to primary and specialty care physicians. The National Rural Health Association (NRHA) 31 reports that in the United States, PCPs constitute 15% of the physician workforce and provide 42% of the care in rural areas. The NRHA also found that the ratio of consumer to PCPs in urban areas is 53.3 per 100,000, decreasing to 39.8 per 100,000 in rural areas. 32 In addition, nearly two-thirds of U.S. practicing physicians offer specialty services and cluster in urban areas where demand for services is higher based on population growth. These issues of geographical disparity are a principal factor in the context of direct access on both the supply and demand sides.

Internet Utilization

Telehealth affords providers an opportunity to interact with consumers online using a computer, tablet, or smartphone. Options for telehealth utilization include (1) consulting with a provider via video chat or phone, (2) sending and receiving messages, (3) remote testing and monitoring of health outcomes, and (4) ability to adjust and troubleshot treatment technology remotely. The utilization of telehealth, overall, is not widespread. In the United States, Trilliant Health 33 reported that telehealth was delivered by 59% of healthcare providers at the onset of the pandemic (i.e., April 2020). By November 2021, telehealth utilization by providers had declined to ∼36% as in-person consultations increased. Part of the reason for the shift to in-person visits resulted from providers receiving higher reimbursement rates compared with rates obtained during a telehealth visit for the same procedure. 33

In hearing care, Eikelboom and Swanepoel 34 found that one in four audiologists, internationally, reported utilizing telehealth services as part of clinical service delivery prior to the global pandemic. More recently, Perez Velez, 35 using the Connected Audiology REadiness (CARE) framework, surveyed audiologists' readiness to utilize remote care as a service delivery option in improving consumer accessibility. Results showed that only 44% of audiologists routinely employed telehealth services and 23% reported using remote care for hearing aid fittings. Survey results further revealed that provider utilization is constrained because >80% of respondents indicated that they lacked professional development in key areas (e.g., knowledge, skills, utilization, insurance requirements, reimbursement for services) required to implement this clinical service as part of a standard of care. To that end, Perez Velez et al noted the need for the development of guidelines to aid hearing care providers in the delivery of remote care.

Financial Accessibility/Affordability

Direct Access to Services

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, designates audiologists as “nonphysician practitioners.” 36 The “nonphysician” designation c stipulates that audiology services are not covered by government-subsidized programs (i.e., Medicare d and Medicaid) unless the services are deemed “medically necessary” and coded as “other diagnostic tests” in support (1) of a physician's diagnostic evaluation or (2) to evaluate the appropriate medical or surgical intervention for a disorder of the auditory system. 37 In addition, there is no provision in Medicare to reimburse audiology treatment services (e.g., cerumen removal, auditory rehabilitation, hearing aids, auditory implants). Under Medicaid, certain U.S. states provide minors with periodic hearing screening and medical referrals through the CMS Early and Periodic Screening Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT). 38 For older adults, who are at greater risk for hearing loss, Medicaid offers no comparable hearing loss screening and referral program.

U.S. beneficiaries of government-subsidized insurance plans are dependent, in part, on the accessibility and availability of primary care physicians (PCP). 39 That is, for a beneficiary to receive audiological services, a PCP must establish medical necessity before the provider can request payment for services rendered. In addition, audiology scope of practice varies by state, each differing in (1) how they classify hearing and balance testing under the “other diagnostic tests” category and (2) the type of healthcare provider (e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners) that can perform these tests. 40

These restrictions have a negative influence on the U.S. scope of practice in audiology; they directly limit reimbursement revenue from government-subsidized insurance plans. This limitation impacts the provider's decision of (1) where they locate—typically, urban areas with higher household incomes; and (2) the type of consumer they service—namely, those that pay out-of-pocket for services beyond diagnostics (e.g., cerumen removal, auditory rehabilitation, hearing aids, real-ear testing). Stated differently, the fact that audiologists tend to establish their practice locations primarily in metropolitan and urban areas puts U.S. beneficiaries—those ≥65 years of age and those residing in rural areas—at a hardship in accessing clinical services.

Acceptability of Services

Provider Age

According to demographic and member data reported by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), 41 nearly 71% of U.S. audiologists are younger than 54 years, who serve an older consumer base. Research suggests that older consumers (i.e., ≥ 65 years) desire a personal relationship with their practitioner and prefer that their provider be of similar age. 42 These authors add that differences in age result from younger providers' lack of understanding toward an older consumer's emotional state of aging and their need for increased medical care. Furthermore, younger providers tend to be less flexible with appointment scheduling, instead of operating with a specific care plan occurring within an allotted time. Kuiper et al 43 found that older adults require flexibility during the appointment, as they attempt to first build a relationship with the provider centered on trust.

Workforce Diversity

The current U.S. audiology workforce is not representative of population diversity. According to the 2020 U.S. census, racial minorities represent 27.6% of the population, with 18.7% identifying as Hispanic or Latino, 12.4% identifying as Black or African American, and 6.0% identifying as Asian. 44 The U.S. audiology workforce constitutes only 8% racial minorities, with 3.3% identifying as Hispanic or Latino, 2.5% identifying as Black or African American, and 3.7% identifying as Asian. 41 In addition, only 6% of audiologists meet the definition of a bilingual service provider. 41

What is the importance of having a workforce that reflects the population diversity? A study conducted by the U.S. Government Accountability Office 45 found that diversity in healthcare workforce is important because (1) minority groups disproportionately live in areas with provider shortages; (2) consumers are more apt to receive care from members of their own racial and ethnic backgrounds, and (3) members of racial and ethnic minority groups are increasingly likely to practice in shortage areas. To lessen this gap, the Allied Health Workforce Diversity Act of 2021 bill has been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives (HR 3320) 46 and U.S. Senate (S 1679) 47 that would allow the government (i.e., DHHS) to provide grants to accredited education programs—including audiology—to increase opportunities for students from racial and ethnic minorities to enter the profession.

Patient-Centered Care

Patient-centered care (PCC) is defined as the provision of care that is respectful of, and responsive to, an individual's preference, needs, and values, and ensures that consumer values guide clinical decisions. 48 Professions—such as medicine 49 and nursing 50 —have developed PCC framework guidelines and metrics to assess the degree to which a provider is employing the process. In audiology, a recommended PCC framework guideline is yet to be developed formally.

The literature indicates that most audiology providers have not fully embraced PCC in their daily clinical interactions, as evidenced by (1) an absence of relationship-building with their patients, 51 (2) a lack of empathy when patients present psychosocial concerns expressed with a negative emotional stance, 51 52 (3) failing to include family member's input as part of the treatment and management process of patient healthcare, 53 (4) failing to acknowledge consumer's emotional responses during the decision-making process with respect to hearing aid cost options, 54 and (5) not promoting an equal opportunity for consumers to participate actively in their own treatment and management of their hearing impairment. 51

Readiness

Readiness is the extent to which supply-side stakeholders provide services and products that meet consumers' needs. 55 With respect to PCC and consumer readiness, Amlani 56 found that first-time consumer pre-appointment, service delivery expectations for an in-person hearing evaluation, and possible rehabilitative treatment intervention were unmet post-appointment on several dimensions (e.g., trust, empathy, shared decision-making, communication). In addition, the author found that pre-appointment expectations were influenced by professional setting, with provider's pre-appointment expectations being markedly higher in the rehabilitative and medical settings compared with a perceived consumer electronics setting. Additionally, in a retrospective study of nearly 25,000 audiology appointments, Singh and Launer 57 found that hearing adoption rates were lower at noon and at 4 pm compared with earlier morning and afternoon appointment time slots. These authors hypothesized that this trend might be associated with provider's behavior stemming from fatigue of previous appointments or related to provider's motivation toward food consumption to manage changes in metabolic levels.

Another supply-side consideration that influences patient readiness is the stereotype that Baby Boomers' hearing sensitivity is more severe than those individuals from the Silent generation because of recreational noise exposure. Research, in fact, indicates the reverse, where Baby Boomers hearing difficulties are less severe than anticipated because of improvements in occupational standards and nutrition compared with individuals from the Silent generation. 58 59 In addition, patient readiness is hindered, in part, by clinical nomenclature such as mild and hearing loss , which negatively impacts consumer behavior toward hearing healthcare services. 60 Clearly, provider's knowledge toward various service delivery offerings and their interactions with consumers markedly influence delivery and acceptance of hearing care services and products.

Summary—Supply Side

Factors that Influence Professional Workforce Availability and Accessibility

Globally, there is and will continue to be a work force shortage of audiologists to provide hearing care services to consumers with hearing loss and hearing difficulty.

-

For the U.S. market, the current audiology workforce is not representative of the population it serves with respect to age and diversity.

-

a. Most individuals with hearing loss are older adults, ≥ aged 65 years, who are served by a predominately younger practitioner pool.

i. These age differences impact the relationship between provider and consumer given that the younger professionals lack the ability to empathize with their aging consumer's emotional needs and build a relationship based on trust.

-

b. Only 8% of the audiology workforce identifies as belonging to a racial minority, which is markedly less than the nearly 28% of the U.S. population that identify as belonging to a racial minority.

i. This lack of racial diversity among the audiology workforce has implications toward the adoption of hearing care services by minority groups. Consumers from minority backgrounds are more likely to receive care when the provider is a member of their own racial and ethnic background.

-

Factors that Influence Direct Access

-

The supply-side is challenged by the geographic consumer's availability of audiologists and PCPs. The data indicate that consumers most affected:

a. Reside in rural areas, where distance and travel time are barriers to in-person care.

b. Are beneficiaries of government-subsidized insurance plans, who require a physician evaluation to determine medical necessity as mandated by U.S. health policy.

For audiologists, accessibility to U.S. beneficiaries of government-subsidized insurance plans is dependent on a referral from a PCP, who has established “medical necessity” before reimbursement can be requested for hearing care services rendered.

-

To lessen the impact of geography, providers are inclined to

a. Locate in metropolitan counties having higher median incomes.

This allows for audiologists to target consumers who pay out-of-pocket services, for hearing aids and associated services.

-

For consumers who reside in rural areas, this means that

a. Provider accessibility is constrained as consumers must travel a farther distance or experience longer travel times.

b. There is a lower probability that an audiologist is practicing in a state or rural county that offers insurance coverage for audiology services to adult beneficiaries.

c. Lower preponderance of accessing a PCP for adult beneficiaries who must establish medical necessity prior to receiving audiological services.

Factors that Influence Patient-Centered Care and Readiness

Providers act as barriers to the service delivery model for consumers willing to engage in their hearing care journey. The literature indicates that:

-

Many audiologists need professional development in the areas of:

a. Counseling strategies that enhance PCC and patient readiness.

b. Patient readiness is constrained by clinical nomenclature, such as mild and hearing loss .

-

Consumer pre-appointment expectations are not being met by providers

a. These expectations differ as a function of in-person, professional setting. It is unknown whether telehealth and remote care would alter consumer's predisposed expectations.

-

Providers must be careful to limit bias in their clinical judgment toward consumers because of their generational categorization (e.g., Silent, Baby Boomers).

a. Research suggests that Baby Boomers' hearing sensitivity is better than that of the Silent generation because of improvements in occupational standards and nutrition.

Factors that Influence Internet Utilization

-

A lack of application and implementation of telehealth and remote care into clinical practice. Areas that have precluded provider utilization include:

a. In the United States, there is a decline in the provider's provision of telehealth.

b. One reason for this decline is that in-person visits result in higher reimbursement rates than telehealth visits.

c. Deficiency in hearing care provider. Knowledge, skills, and utilization technology in service provision.

d. Knowledge of insurance, reimbursement, and licensure regulations toward telehealth and remote care in clinical practice.

Application to Framework

To overcome the supply-side challenges, the profession and industry must accept that consumers with hearing loss will be the drivers in determining how they access hearing care. These access points include:

Alternative channels, namely, direct-to-consumer (DTC; i.e., no clinic) and over-the-counter (OTC; i.e., no prescription).

Alternative services (i.e., telehealth, self-fit).

Accessibility to consumer-technology products (i.e., self-fit hearing aids, hearables).

To determine the appropriate access points to meet consumer demand for a given local market, it is essential that providers perform a business assessment of current versus future offerings in the market prior to engaging in new models of service delivery. Demand for services can be garnered through (1) consumer surveys and focus group interviews of current consumers and (2) the application of strategy mapping (e.g., gap analysis, balance score card, competitor analysis). The feasibility to integrate and apply future offerings—based on the outcome derived from the demand for services—includes (1) evaluating and identifying the resources required (e.g., equipment, personnel, interprofessional partnerships), (2) perform financial projections to forecast and compare expenses and revenues, and (3) ensuring that professional development needs are met prior to the new service offerings. The success of the new models of service delivery should be quantified and evaluated periodically (e.g., 3-, 6-, and 12-month intervals) and adjusted based on consumer demands and resource feasibility.

To overcome the challenges of in-person availability and accessibility will require hearing care professionals to evaluate other service opportunities, such as telehealth. For instance, the hearing care framework presented by Brice and colleagues 7 provides context to overcome the shortage and demographic disparities in the U.S. professional workforce. Hearing care providers who practice in metropolitan areas have opportunities to expand services to consumers who reside in rural areas that lack comparable hearing care services. Service provision in rural areas is feasible by combining a service mix of diagnostic and treatment offerings including (1) in-person diagnostic care accompanied by follow-up care via telehealth and remote care (i.e., services provided for treatment offerings, such as counseling and hearing aid adjustments) and (2) telehealth care (i.e., primarily diagnostic testing) and follow-up care via telehealth and remote care. The service model utilized by a provider must (1) adhere to state licensure and federal regulations and (2) be accessible by consumers (e.g., broadband Internet access in rural areas, which is discussed in the section on supply-side factors).

There are also opportunities to increase diagnostic and treatment services to underserved populations, such as Blacks and Hispanics. The provision of telehealth and remote care allow for an increase in minority providers reaching consumers from similar racial and ethnic backgrounds. For telehealth and remote care to expand its reach successfully, the profession must ensure that providers are trained, able, and adept at applying and integrating this model of service delivery within their respective state and federal guidelines.

Accessibility to hearing care for beneficiaries of U.S. government-subsidized insurance is mandated by the provision to obtain medical necessity by a PCP. This provision can be obtained by the consumer either locally through an in-person visit or remotely via telehealth. Hearing care providers should embrace this arrangement to include whole-person-centered care through advanced service offerings (e.g., tinnitus, balance) and associated health conditions (i.e., comorbidities) that are known to affect hearing sensitivity negatively.

Lastly, these new service models can also contribute to increasing PCC and patient readiness toward hearing care. Telehealth, for example, allows for the clinic to begin building the patient–provider relationship through interactions with clinic staff. 61 In addition, consumer relationship building can be increased using different counseling strategies. One example is the application of motivational interviewing (MI). MI is a shared decision-making technique that assesses the motivation of consumer to adhere to the treatment plan and guides a change in consumer behaviors toward better health. This technique, once mastered, can be applied and integrated using the telephone, telehealth, and remote care. 62 In addition, an alternative counseling technique to using clinical nomenclature such as mild and hearing loss is the application of the speech intelligibility index and count-the-dot audiogram. Here, results are presented as a function of audibility. 63

DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Demand-Side Factors

Availability

Consumer Demand

In the United States, hearing loss affects an estimated 38.3 million Americans aged ≥12 years. 64 When hearing loss estimates are isolated by degree of loss, 25.4 million individuals are categorized as mild (i.e., thresholds between 26- and 40-dB HL), 10.7 million characterized as moderate (i.e., thresholds between 41- and 60-dB HL), 1.8 million classified as severe (i.e., thresholds between 61- and 80-dB HL), and 0.4 million categorized as profound (i.e., thresholds ≥81 dB HL). Findings further indicate with age that there is an increased prevalence of hearing loss, along with an increase in the severity of hearing loss. Further, the occurrence of hearing loss is highest among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites than among non-Hispanic Blacks. Lastly, hearing loss is more prevalent in men than in women.

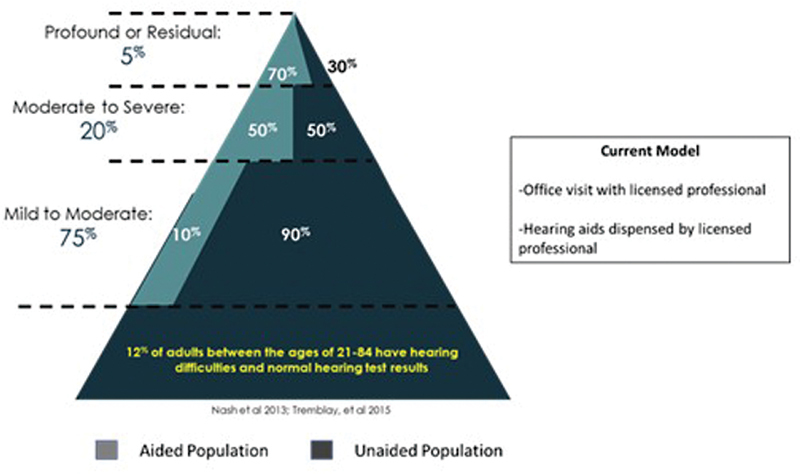

Fig. 3 displays the U.S. demand for traditional hearing aids (i.e., accessible only by a visit to a licensed professional [i.e., physician, audiologist, hearing instrument specialist]) segmented by degree of hearing loss. Here, consumers must obtain a “recent” e hearing evaluation prior to pursuing a hearing aid. Demand for hearing aids is depicted using a pyramid, a model adopted from Granholm-Leth. 65 The base of the pyramid represents individuals with normal hearing and hearing difficulties, followed by individuals with lesser severities of hearing loss. Those with more severe hearing losses are represented at the peak of the pyramid. Near the base, the figure shows that 75% of individuals demonstrate a mild-to-moderate degree of hearing loss, yet only 10% of individuals in this category adopt hearing aids (i.e., denoted by the light gray shading). When the prevalence estimates described earlier are applied to this model, estimates suggest that only 2.54 million Americans (i.e., 10%) have adopted hearing aid technology as a treatment intervention out of a total subpopulation of 25.4 million individuals. This estimate further indicates an untreated subpopulation of 22.9 million individuals (i.e., 90%). In contrast, individuals with severe degrees of hearing loss are increasingly likely to pursue hearing care services and adopt amplification technology. This is evidenced in the profound category (i.e., total subpopulation of 0.4 million Americans), where 70% of this population (i.e., an estimated 0.28 million individuals) has obtained hearing aid technology and 30% (i.e., an estimated 0.12 million individuals) remain classified as untreated.

Figure 3.

Demand for traditional hearing aids segmented by degree of hearing loss. See text for details.

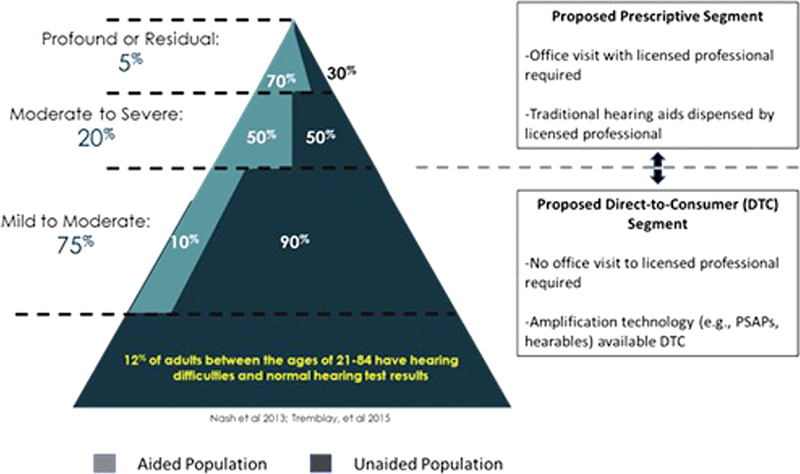

Fig. 4 reveals the proposed Food and Drug Administration (FDA) legislation to increase demand by expanding consumer access and availability of nontraditional amplification technology (i.e., PSAPs, hearables) for consumers with mild-to-moderate losses. 69 This increase in demand is predicated on reducing supply-side barriers (e.g., workforce shortage, direct access limitations), while increasing demand-side accessibility and affordability. The proposed legislation will allow consumers with mild-to-moderate hearing losses access to (1) self-fit DTC devices that offers neither professional diagnostic services nor treatment support (e.g., Bose), (2) self-fit DTC devices that offers no professional diagnostic services but does provide treatment support (e.g., Nuheara, Lexie), (3) purchase DTCs and have access to professional support via telehealth (e.g., Blamey Saunders hears), or (4) purchase traditional devices online with access to a provider via telehealth (e.g., Lively). The proposed model does not advocate DTC and PSAP devices for individuals with moderately severe to profound losses; instead, this population will continue to be required to first seek an evaluation by a licensed provider prior to pursuing traditional devices.

Figure 4.

Comparing the demand for traditional hearings segmented by hearing loss to the proposed Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rule that includes direct-to-consumer access of nontraditional amplification technology (i.e., PSAPs, hearables) for individuals with mild-to-moderate losses and requiring prescriptive (i.e., provider-based) access of traditional devices for individuals with moderately severe to profound losses.

Geographic Accessibility

Consumer Demographics

The Pew Research Center compared geographic trends for data reported in the 2000 U.S. Census and for data available in the 2012–2016 American Community Survey. 70 These trends are reported as a function of urban (i.e., population ≥50,000), suburban (i.e., population ≥2,500 and near urban area), and rural (i.e., population < 2,500 and not considered an extension of an urban setting) communities. The data reported, while not specific to individuals with hearing loss, portray trends in population changes that impact potential healthcare accessibility. Three trends emerged: (1) growing racial and ethnic diversity, (2) increased immigration (i.e., people who are foreign born), and (3) marked growth of older adults.

When comparing U.S. population data trends between 2000 and 2012–2016 ( Table 1 ), there is no change in urban population living, a 2% increase in suburban living, and a 2% decrease in rural living. In addition, the U.S. population majority is White. Current trends, however, indicate a decrease in the percentage of White Americans in all three communities, with the largest decreases—7 and 8%—seen in urban and suburban communities, respectively. All three communities are also seeing a slight increase—between 2 and 3%—in the population of foreign-born residents and an increased percentage of individuals aged ≥ 65 years. Lastly, for residents residing in rural communities, trends reveal a lower per capita income and a higher prevalence of adults who describe their health status as fair/poor compared with urban and suburban areas. 31

Table 1. Pew Research Center comparative analysis between 2000 U.S. Census and 2012–2016 American Community Survey data for U.S. population, ethnic/racial diversity, immigration, and older adults as a function of urban, suburban, and rural communities.

| Communities | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Suburban | Rural | ||||

| 2000 | 2012–2016 | 2000 | 2012–2016 | 2000 | 2012–2016 | |

| U.S. population | 31% | 31% | 53% | 55% | 16% | 14% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 51% | 44% | 76% | 68% | 82% | 79% |

| Immigrants | 20% | 22% | 12% | 15% | 15% | 18% |

| Older adults | 11% | 13% | 12% | 15% | 15% | 18% |

Internet Access and Utilization

Reliable, broadband Internet access is a requisite for remote delivery of hearing care programs (i.e., telehealth) that rely on video conferencing. In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines broadband connectivity as having a minimum of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) for downloads and 3 Mbps for uploads. 71 Globally, the United States ranks third with the highest number of broadband Internet users at 307 million, behind China (1 billion users) and India (658 million users). 72 The 307 million U.S. broadband Internet users represent an adoption rate of 90.8%, including 276.8 million mobile Internet users. In this subsection, access and utilization trends are reported as a function of (1) home-based, high-speed connection (i.e., broadband) and (2) mobile and smartphone applications.

Broadband Internet

In the United States, disparities exist in broadband Internet utilization as a function of (1) age, (2) among household income, (3) between races (i.e., White, Black, Hispanic), and (4) between community areas (i.e., urban, rural). With respect to age, the Pew Research Center reports that > 95% of adults 18 to 64 years utilize broadband Internet, compared with a utilization rate of roughly 75% for adults aged ≥65 years. 73 For households having high incomes (i.e., ≥ $50,000), Internet utilization is nearly 100%. For middle (i.e., between $30,000 and $49,999) and lower income (i.e., < $30,000) households, consumption is 91% and 86%, respectively. A post hoc analysis further revealed that household income is correlated with education level; that is, the greater the education, the higher the income opportunity. With respect to utilization, broadband Internet use is nearly 86% for those individuals with ≤high school education, increasing to nearly 98% for those Americans with > high school education.

With respect to race, 80% of White adults reported access to broadband Internet, compared with 71 and 65% of Black and Hispanic adults, respectively. Between communities, evidence suggests that rural areas have less access to broadband Internet connectivity than urban areas. In fact, some rural areas have no Internet access—an inequity that affects roughly 53% of rural Americans (i.e., 22 million) and 63% of Americans living in areas of Tribal lands (i.e., 2.6 million). 74 Research further shows that in rural areas where broadband Internet is available, roughly 90% of consumers access the Internet.

Mobile and Smartphone Internet

In the case of mobile and smartphone users, demographics indicate adoption and utilization differences by (1) age, (2) education, (3) income, and (4) community. 73 Across all age groups, > 90% of Americans own some form of mobile technology (i.e., technology having only calling and texting features). Ownership and utilization of smartphone technology (i.e., mobile device that offers many of the options of a computer, such as a touchscreen, Internet access, and an operating system capable of running downloaded applications) is dependent on age, education level, income, and community.

For Americans ≤ 49 years of age, there is ≥ 95% smartphone ownership. Ownership decreases to 83% in the age group 50 to 64 years and 61% for those ≥ 65 years of age. When considering education level, ≥ 89% of those Americans with at least some college education are more likely to own a smartphone compared with 75% of those with a maximum of a high school education. Lastly, income reveals a disparity among categories, where smartphone ownership was identified in 96% of those earning a high annual household income (i.e., ≥ $75,000). For consumers classified as earning middle- (i.e., between $30,000 and $74,999) and low- (i.e., ≤ $30,000) annual household incomes, smartphone ownership decreased to 83 and 76%, respectively. With respect to community, 89% Americans residing in an urban area owned a smartphone, followed by 84 and 80% who resided in a suburban and rural areas, respectively.

Financial Accessibility/Affordability

Health Insurance

For Americans who are beneficiaries of government-subsidized insurance coverage, the healthcare journey requires that they first see their PCP before accessing audiological intervention. It should be noted that CMS does not classify hearing aids as “durable medical devices,” meaning that they are not covered by Medicare unless the beneficiary has enrolled in a supplementary insurance program (i.e., Medicare Advantage Plan). These supplementary insurance programs are managed by government-approved private companies, who are required to follow rules set by Medicare. 75 While Medicare Advantage plans may offer hearing aid coverage, many of these plans still require beneficiaries to pay ≥70% of the total toward their hearing care. 76

Thus, the costs associated with hearing healthcare are prohibitive to many older Americans, particularly individuals relying on retirement income. Medicare beneficiaries with low incomes might be eligible for Medicaid, a government program administered at the state level. The extent of treatment services and products for older adults varies among states and is based on criteria such as eligibility, benefits levels, and “optional” benefits.

Income and Employment

Access to audiology services in the U.S. model, then, is best suited for those with the ability to self-fund the costs of their hearing care needs. 77 Current demographics—taken from an industry survey—indicate that first-time hearing aid adoption is most prevalent among older adults (i.e., > 65 years of age) who are retired or nearing retirement having a median income of $55,500. 78 In addition, the average retail cost of binaural hearing aids in the United States is $4744, 79 or 8.6% of the average individual's median income for this population segment.

For those individuals with hearing loss who remain employed in the workforce (i.e., mainly those < 65 years of age), research indicates that they experience lower incomes than their normal-hearing counterparts. 80 U.S. income estimates have been shown to be between 45 and 75% less for those with hearing loss compared with individuals without hearing loss. 80 81 Kim and colleagues 82 found a disproportional income gap between individuals without and individuals with hearing loss. Specifically, income levels were assessed over a 5-year period in Korea. While income levels increased for all individuals during this period, the cumulative income level earned by those with hearing loss was substantially less than the cumulative income level earned by those without hearing loss. In the United States, where trends indicate that income is associated with race, Black and Hispanic individuals with hearing loss showed > 2 times higher odds of being low income (i.e., ≤ $20,000 in annual family income) than their White counterparts. 83 This trend, in part, explains the higher rate of hearing aid use among older adults who are White, ranging between 28.6 and 35.5%, compared with minorities, ranging between 10 and 17.1%. 84 85 86

Working adults with hearing loss further experience biases that affect income and employment. Two studies report a U.S. employment rate of roughly 75% for people without communication difficulties, compared with an employment rate of ∼50% for people with communication difficulties, including those who experience hearing loss. 81 87 In the United Kingdom, a recent survey revealed a 65% employment rate for people who reported difficulty hearing as their primary health issue compared with a 79% employment rate for people who reported no long-term health disability. 88 Moreover, 70% of UK employees reported that their hearing loss negatively impacted their abilities from fulfilling their potential at work, 74% conveyed perceptions of being isolated from peer interactions at work, and 41% of employees admitted retiring from the workplace prematurely.

Acceptability of Services

In this subsection, acceptability of services is presented as a function of demand-side patient readiness.

Consumer Demographics

Age

The prevalence of hearing loss increases with age. In the United States, for instance, ∼6.5% of people in their 40s have some degree of hearing loss, with prevalence estimates increasing to 26.8% for individuals in their 60s, and 81.5% for individuals ≥ 80 years of age. 75 Perhaps, an important consideration is the extent to which older adults perceive the aging process and how this perception affects the manner in which they use healthcare resources. 89 According to Levy, 90 the self-perception of aging (SPA) stems from exposure to stereotypes across the life span, and the internalization of these stereotypes influences health. Research suggests that older adults with a negative SPA experience increased functional limitations 91 and were less likely to recover from disability 92 compared with peers with a more positive SPA.

Diversity

Research shows that most U.S. hearing aid users are White, earning, at a minimum, middle-class (i.e., between $30,000 and $74,999) annual household incomes. As such, the market reflects a stratification with respect to hearing aid adoption based on income and insured status. 86 93 94 95 For instance, Arnold et al 94 evaluated the prevalence and factors associated with hearing aid use among U.S. adults of Hispanic/Latino backgrounds using a cross-sectional dataset adopted from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. This dataset represents a cohort of 16,415 Hispanics/Latinos from four cities (Bronx, NY; Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; and San Diego, CA) between 2008 and 2011. From this dataset, 1898 adults—aged 45 to 76 years—were identified as having hearing loss with only 87 individuals indicating that they used hearing aids. The primary factor related to hearing aid use was health insurance.

Recently, Reed and colleagues 95 analyzed hearing aid ownership in the United States. Data were extracted from the 2011, 2015, and 2018 cycles of the National Health Aging and Trends Study, which is a longitudinal study of Medicare beneficiaries. The authors found that while hearing aid adoption increased by 23.3% between 2011 and 2018, the growth is masked by the fact that hearing aid ownership is prohibitive to Americans who (1) experience lower income, (2) were racially classified as Black, and (3) female.

Education Level

Only a handful of studies have evaluated the educational level of consumers and their hearing health needs. Gussekloo et al 96 undertook a prospective population-based analysis of elderly individuals with hearing loss and their willingness to adopt hearing aids in the Netherlands. Results revealed that differences in educational level—defined as low (i.e., no schooling/only primary school) or high (i.e., ≥ secondary school)—were not correlated with the adoption or non-adoption of hearing aids. A similar outcome was reported by Humes and colleagues, 97 who evaluated differences in groups of hearing aid candidates (i.e., accepted hearing aids, rejected hearing aids) matched for demographic factors, including education level. Results revealed no differences among groups based on educational level. Helvik et al, 98 on the other hand, found that higher educational level (i.e., ≥13 years) increased the odds of rejecting a hearing aid.

Consumer Characteristics

Self-Perceived Hearing Difficulties

Research shows that self-perceived hearing difficulties are a key indicator toward readiness to pursue treatment. 99 100 101 102 103 104 In comparison, audiometric threshold results are neither predictive of consumer self-perceived hearing handicap nor their readiness in obtaining amplification. 105 106 107 Angara and colleagues assessed the role between self-perceived hearing status and hearing treatment using a cross-sectional analysis of data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) ranging between 2005 and 2012. 108 Of the 5,230 responses analyzed, results revealed 26.1% of respondents demonstrated measurable hearing loss, of which only 16% correctly identified hearing status, and only 17.7% adopted hearing aids. Furthermore, industry survey results revealed that only 14% of individuals with self-reported mild hearing loss adopted traditional hearing aids, while adoption rates increased to 37 and 58% for moderate and severe hearing losses, respectively. 109 Palmer and colleagues 110 found that asking the question, “How would you rate your overall hearing ability?” was a better predictor of assessing patient readiness toward amplification than hearing status.

Recently, Edwards 2 portrayed a market segmentation model—shown in Fig. 5 —that categorizes the hearing care consumer into five distinct groups, based on (1) self-perceived hearing difficulty (i.e., hearing difficulty [HD], no hearing difficulty [NHD]) and (2) hearing loss (i.e., hearing loss [HL], no hearing loss [NHL]). The five segments, and their corresponding treatment offerings, include:

Figure 5.

Market segmentation of consumer demand as a function (1) self-perceived hearing difficulty (i.e., hearing difficulty [HD], no hearing difficulty [NHD]) and (2) hearing loss (i.e., hearing loss [HL], no hearing loss [NHL]). See text for additional details.

NHD-NHL, in panel A, represents consumers who experience some form of auditory dysfunction and test within the normal range on an audiogram, yet do not perceive themselves as having hearing difficulty. Consumers in this segment will not be considered candidates for treatment intervention by providers.

NHD-HL, in panel B, characterizes consumers who present clinically with a hearing loss, but do not self-identify as experiencing hearing difficulty. Consumers in this segment are not likely to seek the services of a provider, despite potential benefits from a hearing aid.

HD-NHL, in panel C, designates consumers who self-identify as having hearing difficulty but have hearing sensitivity within normal clinic limits. Consumers in this segment are potential candidates for alternative treatment interventions—such as PSAPs and hearables—that improve hearing ability.

HD-HL owner, in panel D, represents consumers who present clinically with a hearing loss and self-identify as having hearing difficulty. Consumers in this group consist of traditional hearing aid users.

HD-HL non-owner, in panel E, embodies consumers who present clinically with a hearing loss and self-identify as having hearing difficulty, yet do not purse a treatment intervention. Consumers in this group are often most affected by DoHs—namely accessibility and affordability—and alternative treatment interventions (e.g., self-fit, OTCs, PSAPs) could be an attractive hearing care solution.

Lastly, the literature indicates several factors that adversely influence self-perceived handicap and the pursuit of treatment interventions. Demographic variables include age (i.e., younger listeners ≤50 years), sex (i.e., females), ethnicity (i.e., minorities), and education level (i.e., high school level or below). 101 111 112 113 114 115 Auditory risk factors include auditory processing disorders, 116 hidden hearing loss, 117 118 deficits in auditory temporal processing, 119 and neural synchrony. 120 Non-auditory factors include cognition, 121 122 comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, thyroid disease), 123 124 and environmental (e.g., chemical exposure to solvents and heavy metals). 125 From a social perspective, stigma 126 127 and personality traits have been associated with biases in self-reported hearing loss. 128 129 These social factors are discussed in greater detail in the following subsections.

Stigma

Stigma is often associated with aging, particularly as it relates to communication and social interaction. 126 According to Heatherton et al, 127 stigma is defined as having two fundamental characteristics: (1) the recognition of difference based on a distinguishing characteristic and (2) a devaluation of the person. This negative self-perception is further compounded by ageism, or the stereotype of and discrimination against a person because they are old. 130 In hearing care, stigma and ageism are associated with wearing a hearing aid, and not necessarily the hearing loss itself. This perception, called the hearing aid effect, was first coined by Blood and colleagues. 131 With the increased use of consumer electronic products, such as Bluetooth receivers, ear buds, and earphones, one would presume a decline in the hearing aid effect. Rauterkus and Palmer 132 evaluated the influence of various types of devices worn by young men and found no significant stigma associated with hearing aid use as perceived by non-hearing-aid-wearing young adults. However, there is little evidence, to date, on the diminished perception of the hearing aid effect toward consumer electronic products by neither those with self-perceived hearing loss seeking amplification strategies nor current users of hearing aid technology.

Personality

Personality is the characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are unique to each individual. The literature indicates that personality influences consumer readiness. Gatehouse, 128 for example, found that factors such as personality and intelligence did not predict performance with hearing aids, but did predict self-perceived hearing difficulties.

McCrae and Costa 133 state that an individual's basic personality comprises five fundamental traits (i.e., five-factor model of personality) and that these traits remain stable across the lifespan after the age of 30 years. The five traits are:

Neuroticism—A trait disposition toward negative effects, including anger, self-consciousness, irritability, emotional instability, and depression. Individuals with this trait often experience low-self-confidence and are likely to blame others for their problems.

Extraversion—Individuals with high extroversion are outgoing, enthusiastic, optimistic, and self-confident, and enjoy large social gatherings. Personality traits include energetic, talkative, and assertive.

Openness—A trait in which an individual is willing to learn new things enjoy new experiences. Personality traits include being insightful, imaginative, and having a broad variety of interests.

Agreeableness—These individuals are friendly, cooperative, and compassionate. Personality traits include being kind, affectionate, and sympathetic.

Conscientiousness—The trait of being proactive through planning and organization. Personality traits include reliable, thorough, and prompt.

Hearing loss—independent of severity—is known to influence psychological and social issues, with emotional and societal consequences. 129 A study conducted in Sweden evaluated several variables in a sample of 400 individuals aged 80 to 98 years over a 6-year period. Of the variables tested—which included physical, mental, social, cognitive, and personality measures—individuals with hearing loss were found to have reduced extraversion leading to increased social isolation. 134 The authors found that the lack of social interaction led to a change in personality through increased neuroticism, with little or no changes in emotional stability.

With respect to hearing aid adoption, Cox and colleagues 129 evaluated the personalities (i.e., five-factor model of personality) of individuals pursuing hearing aids to determine whether hearing aid pursuers' personalities varied from the general population. Self-reported data were obtained from 230 older adults using a cross-sectional survey. Study respondents were deemed to be representative of either the Veterans Administration (VA) or the private sector. Findings revealed:

Individuals who scored high on neuroticism were labeled to be susceptible to shame and embarrassment and unlikely to seek hearing aids. This outcome was mostly associated with individuals in the private sector and is consistent with a perception of devaluation (i.e., stigma).

Individuals who scored high on openness tended not to seek hearing aids. Instead, individuals with this personality characteristic are more inclined to rely on ecological variables to overcome their hearing difficulties. This outcome was similar for respondents from both the VA and the private sector.

Individuals who scored low on agreeableness were labeled as skeptical and suspicious. This outcome was associated with individuals in the private sector category and is consistent with the non–help-seeking behavior. For this personality, it is important that providers apply best practices that enhance their value proposition in improving hearing health outcomes.

Franklin and colleagues 135 examined the relationship between the dimensions of personality (i.e., five-factor model of personality) and acceptable noise levels (ANLs f ). 136 The authors found that openness and conscientious personality dimensions were associated with ANLs. Specifically, individuals with low ANLs and categorized with an openness personality trait were hypothesized to be more accepting of higher levels of background. As such, this characteristic was expected to use their hearing aids on a full-time basis. On the other hand, individuals with high ANLs and categorized with a conscientious personality trait were assumed to be less accepting of higher levels of background. These characteristics were believed to correlate with part-time or non-use of hearing aids.

Motivation

Motivation is often cited as a factor to a consumer adopting amplification technology—either through self-motivation or motivation by others (e.g., family member, friend)—or as a source that influences technology use and satisfaction. Knudsen and colleagues, 100 who provide an excellent literature review between 1980 and 2009 on factors lending to hearing aid adoption, report that motivation has a positive influence on patient readiness, but motivation does not influence use.

Volition, on the other hand, is a term used to explain the degree to which an individual performs an activity, based on his/her unique assessment of personal causation, values, and interests. 137 138 Personal causation is the awareness of one's actions, a sense of personal capacity stemming from physical, cognitive, and social abilities and self-efficacy. Values are developed from one's culture and subjective experiences. Lastly, interests are related to the satisfaction obtained from interactions and participation.

Only one study has evaluated consumer motivation (i.e., intent to change behavior) and volition (i.e., action planning [when to perform the behavior] and coping [overcoming barriers]) toward hearing healthcare. 139 Sixty-seven participants completed a questionnaire regarding hearing aid use. With respect to motivation, participants identified with strong intentions to use hearing aids reported high self-efficacy scores. These same participants reported lower levels of action planning and coping planning, suggesting decreased hearing aid use, satisfaction, or both.

Health Literacy

Health literacy is commonly defined as the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand health information and services to make appropriate health decisions. 140 As part of its Health People 2030 initiative, the U.S. government recently revised the definition of health literacy to capture both individual (i.e., personal) and organizational aspects. 141 Personal health literacy is defined as the degree to which an individual can find, understand, and use information and services to make informed health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others. Personal health literacy is often associated in consumers having lower incomes, lower educational level (< college), in older adults, and in minorities. 142 Low health literacy can pose a barrier to quality-of-care in an individual and has been linked to poor health outcomes. As an example, Schillinger and colleagues assessed the relationship between health literacy—categorized as inadequate, marginal, and adequate as determined by a standardized reading comprehension performance—and health outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes. 143 Results revealed that individuals in the inadequate category were most affected in their ability to (1) navigate the healthcare system, including locating providers and services; (2) share personal and health information with providers; (3) engage in self-care and chronic disease management; (4) adopt health-promoting behaviors; and (5) adopt preventative measures. As such, these individuals were less likely to experience healthy outcomes from the treatment intervention.

Organizational health literacy is a new category created by the U.S. government. 141 The rationale for this new category was to ensure that the responsibility toward healthy outcomes did not rely solely on the individual. In addition, this new category makes organizations and providers accountable in ensuring that health information eliminates disparities and achieves health equity. To that end, organizational health literacy is defined as the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information to make informed decisions and take actions for themselves and others. McCaffery and colleagues indicate that an individual can be literate and have low health literacy, which is impacted by content and context, presented both written and oral. 144 For example, an engineer may be prescribed an oral medication for a thyroid disorder with the instructions to take the medication once daily on an empty stomach. However, because the engineer does not understand how this class of medications impacts his health condition, he/she might be more prone to take the medication only as needed or on a full stomach, offsetting the intended therapeutic benefit from this treatment. Research shows that during a healthcare appointment, 40 to 80% of information is forgotten immediately, and roughly 50% of retained information is incorrect. 145 146

There are examples of health literacy in hearing care. Wells and colleagues 147 explored the characteristics associated with health literacy (i.e., limited vs. adequate), medical costs, and medical gaps in a sample of 19,223 adults aged ≥ 65 years who completed a health survey. Health literacy, hearing loss, and hearing aid use were assessed through self-reports. Results revealed that limited health literacy was associated with older age, male gender, lower income, poorer health conditions, and those with hearing loss who did not use hearing aids. Similarly, Tran et al 148 assessed the association between health literacy, degree of hearing loss, and hearing aid adoption in a sample of 1,376 consumers against demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, employment status, race, language) and insurance coverage. Findings revealed that consumers with low health literacy had an increased likelihood of presenting with higher degrees of hearing loss. Interestingly, those with lower health literacy were no less likely to obtain hearing aids compared with consumers with adequate health literacy.

Recent research has also assessed the consumer's ability to manage a self-fit hearing aid through written instructions. Convery and colleagues 149 tasked participants and their partners—recruited from culturally diverse and linguistic backgrounds—to assemble a pair of self-fit hearing aids using culturally and literacy appropriate written instructions and illustrations. Results revealed that study participants could manage the self-fitting hearing-aid assembly successfully. In another study, Convery et al 150 evaluated the ability of a group of adult participants—without and with hearing aid experience—to set up a pair of self-fitting hearings for their own use. Participants were provided the product's accompanying written and illustrated instructions to complete the task, with optional assistance from a lay partner. Results revealed that just over 50% of participants—independent of their experience with hearing aids—were able to perform the self-fitting procedure successfully. These authors conclude that participants' performance, in part, could have been influenced by the instruction set and physical design of the self-fit hearing aid, both of which would benefit from refinement.

Summary - Demand Side

Factors that Influence Availability

Demographics

-

In the United States, hearing loss affects roughly 28.3 million Americans, or 10% of the total population.

a. Of this estimate, 94% of Americans are categorized as exhibiting either mild (i.e., 25.4 million) or moderate (i.e., 10.7 million).

-

b. Prevalence data indicate that hearing loss:

i. Increases as a function of age.

ii. Is highest among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites.

iii. Affects more men than women.

-

Prevalence of hearing loss increases with age.

a. Americans in their 40s represent 6.5%, while those in their 80s represent 81.5%.

-

Demand for hearing aids indicates that:

-

a. Only 10% of Americans who demonstrate mild-to-moderate hearing loss adopt traditional hearing aids.

i. The proposed FDA model provides accessibility to DTC products, with options for self-fit or provider assistance.

-

b. 70% of individuals with profound hearing loss adopt amplification.

i. The proposed FDA model will require individuals with > moderate hearing loss to be evaluated by a provider prior to pursuing traditional hearing aid devices.

ii. The proposed FDA model does not consider DTC products or self-fit strategies for > moderate hearing losses.

-

c. With respect to diversity, most hearing aid users are:

i. White with ≥ middle income households.

ii. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to adopt hearing aids based on lower income, education level, and lack of health insurance coverage.

-

Geography

-

Geographic trends—compared between 2000 and 2012–2016—indicate

-

a. Most of the U.S. population is White

i. Geographically, there is a shift in where White Americans reside. In urban and suburban communities, respectively, there is 7 and 8% decrease of White Americans.

ii. In the immigrant population, there is an increase of 2 to 3% in all three communities (i.e., urban, suburban, rural).

b. Estimates indicate an increase in the aging population over time for those 65 years and older in all three communities.

c. Overall, residents residing in rural communities have lower per capita income and a higher prevalence of adults who describe their health status as fair/poor compared with urban and suburban areas.

-

Internet Access and Utilization

-

Broadband Internet is a requirement for telehealth

a. In the United States, the federal minimum for broadband connectivity is 25 Mbps for downloads and 3 Mbps for loads

-

b. Broadband Internet utilization

i. Age: Older adults (i.e., ≥ 65 years) utilize broadband connectivity around 75%, compared with 95% for younger adults (i.e., 18–64 years)

ii. Household income: High-income households utilize broadband 100%, compared with 91% for middle-income house, and 86% for low-income households. Income is correlated with education.

iii. Race: Whites access broadband 80%, compared with 71% for Blacks, and 65% for Hispanics.

iv. Community areas: Rural areas have less access to broadband connectivity than urban areas.

-

c. Mobile and smartphone Internet

i. Mobile technology is utilized by 95% of Americans.

-

Smartphone technology ownership is age dependent

a. ≥ 95 ownership for young Americans (≤ 49 years)

b. 83% ownership for middle-aged Americans (50–64 years)

c. 61% ownership for older Americans (≥ 65 years)

-

Education

a. ≥ 89% of Americans with some college experience own a smartphone

b. 75% of Americans with a maximum of a high school education own a smartphone

-

Income

a. 96% of high-income households own a smartphone 96%, compared with 83% for middle-income house, and 76% for low-income households

-

Community

a. 89% of Americans in an urban area own a smartphone, compared with 84% in suburban areas, and 80% in rural areas

Factors that Influence Financial Affordability

Health Insurance

Before accessing audiological diagnostic intervention, beneficiaries of government-subsidized insurance coverage requires that the consumer first see their PCP.

-

Hearing aids are not covered by Medicare as CMS does not classify hearing aids as “durable medical devices.”

-

a. Access to hearing aids is available through a Medicare supplementary insurance program called Medicare Advantage Plan.

i. These supplementary insurance programs are managed by government-approved private companies, and often require beneficiaries to pay most expenses toward the cost of their hearing care.

-

Medicare beneficiaries, who are eligible for Medicaid based on their income level as determined by the state in which they live, might qualify for hearing aid services.

Income and Employment

Given the U.S. model for healthcare, audiology services are best suited for consumers with the ability to self-fund their hearing care needs.

-

Unfortunately, self-funding hearing care is not favorable for

a. People with hearing loss who experience lower incomes and lower workforce participation rates.

b. Black and Hispanic individuals who earn less income than their White counterparts.

Factors that Influence Accessibility of Services (Patient Readiness)

-

Self-perceived hearing loss is a key indicator in assessing readiness to pursue treatment

a. Audiometric threshold data are neither predictive of self-perceived hearing handicap nor readiness for hearing aid adoption

b. The literature highlights several factors—demographic, auditory risk, and non-auditory—that adversely influence perceived handicap

-

Stigma is a factor affecting self-perceived hearing difficulty:

-

a. Adverse effect includes ageism

i. Wearing a hearing (i.e., hearing aid effect)

b. Positive effect includes increased use of consumer products being utilized, such as ear buds and headphones

-

-

Personality appears to play a role in readiness toward treatment

a. Social isolation contributes to reduced extraversion

b. Individuals with high neuroticism are unlikely to seek hearing aids. This outcome was most associated with individuals in the private sector and is consistent with a perception of devaluation (i.e., stigma).

c. Individuals with high openness tended not to seek hearing aids. This outcome was similar for respondents from both the VA and the private sector.

d. Individuals with low agreeableness are most likely not to seek help. This outcome was associated with individuals in the private sector and implies that providers must deliver best practices in support of their value proposition in improving hearing health outcomes.

e. Low ANL scores with an openness personality trait correlated with full-time hearing aid use.

f. High ANL scores with a conscientious personality trait correlated with no or part-time hearing aid use.

Motivation influences patient readiness, not hearing aid use.

-

Health literacy:

-

a. Effects both the individual and organization

-

i. Individual (i.e., personal) health literacy

- Influenced by factors such as lower income, lower education level, and racial/ethnicity status.

- These factors influence the individual from making informed decisions and adopting health-promoting behaviors.

-

ii. Organizational health literacy

- The creation of this category eliminates that the burden of information is solely on the individual.

-

Makes providers and organizations accountable toward ensuring that information eliminates disparities and achieves health equity.

-

Application to Framework

Industry data indicate that only a fraction of Americans benefit from hearing care services, technology, or both. 78 109 This outcome indicates that consumers are seeking hearing care services, but delivery of these services is constrained by accessibility to resources. Data indicate that current U.S. demand stems primarily from (1) older adults (i.e., ≥ 65 years); (2) mostly White, who live in urban areas having ≥ middle annual income; and (3) those exhibiting mild-to-moderate degrees of hearing loss (i.e., 36.1 million Americans, or 94% of the population). To aid in a wider distribution of resources, hearing care is expanding accessibility through new service delivery channels and methods of technology distribution. While expansion of consumer accessibility will increase demand and improve adoption, there are factors that providers must consider when maximizing delivery of services.

An important consideration for providers will be which services to offer. To ensure that consumer demand is being met, providers should engage in an a priori market analysis that includes (1) a query of consumer demand for services obtained through surveys and focus groups, (2) a market analysis of the area where service provision is being delivered, (3) determining the resources required to undertake service provision, and (4) any professional development.

Consumers in rural communities are characterized as having a similar aging profile to the overall population, but tend to have a lower annual income, poorer health status, and less access to PCPs compared with peers in urban areas. The implementation of Internet- and mobile-based service provision (i.e., telehealth) is a viable option, but is dependent on the availability of broadband service and smartphone ownership. For the latter, the preponderance of smartphone ownership is higher for younger adults (i.e., ≥ 95% for those ≤ 49 years) and lower for older adults (i.e., 61% for those ≥ 65 years). Additionally, minorities residing in rural communities have lower incomes, lower access to broadband service, and smartphone ownership. For these consumers who lack resources, providers could seek to implement alternative service options such as (1) at-home audiology (also called concierge audiology or mobile audiology), where providers drive to the consumer's residence and deliver services and (2) the utilization of a computerized automated audiometry system (AAS) operated by trained healthcare assistants. 151

The lack of direct access to a hearing care provider precludes consumer demand for beneficiaries of U.S. government insurance plans. This barrier is being addressed legislatively by way of the Medicare Audiologist Access and Services Act (MAASA). This bi-partisan, legislative proposal will improve outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries by permitting direct access to audiologic diagnostic and treatment services as determined by scope of practice. 152 This legislation also reclassifies audiologists as practitioners, which under Medicare would allow audiology providers to furnish services through telehealth permanently. At present, in the United States, telehealth service provision is permitted only as part of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Federal Public Health Emergency. 153