Abstract

Objectives.

States that are legalizing cannabis for adult use are increasingly focused on equity, with the goal of repairing some of the harm caused by the War on Drugs. This study explains and describes the emphasis states are placing on equity and assesses whether public education can be used to increase public support for equity-focused cannabis policies.

Methods.

We conducted an online survey of 893 New Jersey adults in August and September of 2021, just as state’s Cannabis Regulatory Commission was publishing the first set of regulations for the legal sale and use of cannabis for adults age 21 and older. The study included an experimental design, in which half of respondents viewed an educational message about equity-focused cannabis policies before answering survey questions, and the other half did not.

Results.

Few participants (24.9%) were familiar with the concept of equity in cannabis policy, and a substantial proportion—from about 20% to 35%—provided a “neutral” or “don’t know” response when asked about support for specific policies. Exposure to an educational message was associated with greater perceived importance of equity in cannabis policy (p < 0.05) and greater support for equity-focused policies. Specifically, participants who saw an educational message had greater agreement that New Jersey should provide priority licensing (p < 0.01) and grants (p < 0.001) to people who have been arrested for cannabis, and who now want to participate in the legal cannabis industry.

Conclusions.

Cannabis regulators, public health professionals, and people working to advance racial justice may be able to advance state equity goals and remedy some of the harm from the War on Drugs by expanding public education campaigns to include equity messages.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, equity, systemic racism, war on drugs, media, public education

States that are legalizing cannabis for adult use are increasingly focused on equity, with the goal of repairing some of the harm caused by the War on Drugs (Title, 2021). This study (1) explains why states are emphasizing equity in cannabis policy; (2) shows how states are acknowledging the harm of the War on Drugs by calling for social equity programs, community reinvestment, and expungement of cannabis records within cannabis legislation; and (3) examines whether public education can be used to increase public support for equity-focused cannabis policies.

Why States Are Emphasizing Equity in Cannabis Policy

The War on Drugs is an example of systemic racism (Alexander, 2012). Systematically, over decades, Black and Latine people in the United States have been arrested for cannabis possession at higher rates than white people, although white people are more likely than Black people to report using cannabis at least once in their lives (American Civil Liberties Union, 2013; Edwards et al., 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014, 2020a). Today, Black people are arrested for cannabis possession at nearly four times the rate of white people (Edwards et al., 2020). Racial inequities in cannabis law enforcement are not limited to arrests. In New York City from 1980 to 2003, Black and Latine people were not only more likely than white people to be arrested for using cannabis in public view, they were also more likely to be detained prior to arraignment, convicted, and sentenced to jail (Golub et al., 2007). These cannabis-related interactions with the criminal legal system contribute to the mass incarceration of Black and Latine people in the United States.

Numerous studies document the harm of incarceration, not only to individuals who are incarcerated, but to their families and communities. People who are incarcerated have increased exposure to violence, including sexual assault (Acker et al., 2019); higher rates of communicable disease, such as COVID-19 (Natoli et al., 2021); higher rates of chronic health conditions (Massoglia & Remster, 2019); and are likelier to have access to only nutritionally inadequate food, and live in dehumanizing conditions (Acker et al., 2019). Children of incarcerated parents experience the loss of a parent’s care; loss of stability; increased likelihood of poverty and homelessness; increased likelihood of entering foster care; and increased risk of physical and mental health conditions such as asthma and depression (Acker et al., 2019). At the community level, incarceration manifests as the erasure of young Black men. A 2016 study found that so many young Black men are incarcerated in the United States that national surveillance systems—which exclude institutionalized populations—underestimate health outcomes for Black men aged 18 to 25 (Kennedy et al., 2016). Because these systems are used to identify needs and allocate funding for programs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018), reduced representation may lead to reduced federal funding for public health issues facing Black communities. At the individual, family, and societal level, the effects of incarceration reverberate long after imprisonment has ended, contributing to unstable housing, reduced job opportunities, lower-paying jobs, and worse long-term physical and mental health outcomes (Acker et al., 2019; Massoglia & Remster, 2019). In the words of a Boston leader whose mother was incarcerated during his childhood: “Removing my mother from my home didn’t make me safe. Didn’t make my siblings safe; didn’t make my community safe. It made us less safe. It destabilized us. It created trauma.” (Martinez, 2022).

Legal scholar Michelle Alexander concludes that any involvement with the criminal legal system, including fines, stops, detainments, probations, and arrests, can produce outcomes similar to incarceration (and can lead to incarceration itself) (Alexander, 2012). For example, because of the long history of criminalizing poverty in the United States, the inability to pay small legal fines and fees can lead to arrest and incarceration (Jahangeer, 2019). Encounters with the police—ranging from “stop and frisk” to police brutality—cause psychological and physical harm even when they don’t result in arrest (Alang et al., 2017; Cooper, 2015). Black and Latine men—especially those who identify as members of the LGBTQIA+ community—are at greater risk than white, straight, cisgender men of being stopped and frisked in New York City, regardless of their cannabis use (Khan et al., 2021). Even programs intended to reduce the harm of incarceration can be counterproductive. An evaluation of a cannabis criminal justice diversion program in Harris County, TX, found that Black men are overrepresented in the program, and that Black and Latine men are less likely than white men to finish the program—an outcome that is associated with increased subsequent involvement in the legal system (Sanchez et al., 2020).

The movement to legalize cannabis for adult use is in part a response to the racist policies of and harm caused by the War on Drugs. Although ballot language in the first states to legalize — Colorado, Washington, Alaska, Oregon—did not explicitly reference the War on Drugs, news reports suggest it was a theme of public discussion (Martin & Seattle Times, 2012). Within several years of the first states legalizing cannabis, however, it became clear that legalization had not eliminated racial inequities in cannabis arrest rates. Although the total number of cannabis arrests declined in states that legalized cannabis, racial inequities worsened (Edwards et al., 2020; Firth et al., 2019; Gunadi & Shi, 2022; Sheehan et al., 2021). Of the eight states that legalized cannabis before 2018, racial inequities in arrest rates increased in two states and remained unchanged in one (Edwards et al., 2020). Although racial inequities in arrest rates declined slightly in Massachusetts after its 2016 cannabis legalization—which had an emphasis on equity—they were still higher than the national average in 2018 (Edwards et al., 2020). Despite cannabis being decriminalized statewide in New York in 2019 leading to substantial declines in the total number of cannabis arrests in New York City, a 2020 study concluded that people from Black and Latine communities represented 95% of all cannabis arrests and 96% of all criminal court summons for cannabis in New York City (The Legal Aid Society, 2021).

Developing Cannabis Policy to Reduce Some of the Harm of the War on Drugs

Having seen that greater support is needed for equity to become a reality, states that legalized cannabis more recently — Massachusetts, Illinois, New Jersey, New York—explicitly named the harms of the War on Drugs and proposed social equity provisions in their legislative texts (Sinha, 2021). The following excerpts from state acts legalizing cannabis for adult use illustrate the acknowledgment of harm caused by past enforcement of cannabis laws.

The General Assembly … finds and declares that individuals who have been arrested or incarcerated due to drug laws suffer long-lasting negative consequences, including impacts to employment, business ownership, housing, health, and long-term financial well-being. The General Assembly also finds and declares that family members, especially children, and communities of those who have been arrested or incarcerated due to drug laws, suffer from emotional, psychological, and financial harms as a result of such arrests or incarcerations.

–Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act, Illinois (The State of Illinois, 2019)

Existing laws have been ineffective in reducing or curbing marihuana [sic] use and have instead resulted in devastating collateral consequences including mass incarceration and other complex generational trauma.

–The Marihuana [sic] Regulation and Taxation Act, New York (The State of New York, 2021)

Black New Jerseyans are nearly three times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than white New Jerseyans, despite similar usage rates. A marijuana arrest in New Jersey can have a debilitating impact on a person’s future, including consequences for one’s job prospects, housing access, financial health, familial integrity, immigration status, and educational opportunities. … New Jersey cannot afford to sacrifice public safety and individuals’ civil rights by continuing its ineffective and wasteful past marijuana enforcement policies.

–An Act Concerning the Regulation and Use of Cannabis, New Jersey (The State of New Jersey, 2021)

The following excerpts illustrate approaches states are taking to create opportunities for those who have been harmed by the War on Drugs to participate in the new legal industry.

The regulations shall include…. procedures and policies to promote and encourage full participation in the regulated marijuana industry by people from communities that have previously been disproportionately harmed by marijuana prohibition and enforcement and to positively impact those communities.

–The Regulation and Taxation of Marijuana Act, Commonwealth of Massachusetts (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2016)

[I]n the interest of remedying the harms resulting from the disproportionate enforcement of cannabis-related laws, the General Assembly finds and declares that a social equity program should offer, among other things, financial assistance and license application benefits to individuals most directly and adversely impacted by the enforcement of cannabis-related laws.

–Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act, Illinois (The State of Illinois, 2019)

“A goal shall be established to award fifty percent of adult-use cannabis licenses to social and economic equity applicants and ensure inclusion of: (a) individuals from communities disproportionately impacted by the enforcement of cannabis prohibition…”

–The Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, New York (The State of New York, 2021)

Using Public Education to Increase Support for Equity in Cannabis Policy

With equity now an explicit cannabis policy goal for some states, cannabis regulators, public health professionals, and people working to advance racial justice may be reflecting on how they can support the development and successful implementation of equity-focused cannabis policies. We consider public education a promising approach for two reasons. First, public education is a powerful tool that has been used successfully in public health for decades, including to increase support for policy (Allen et al., 2015; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007; Niederdeppe et al., 2008; Tobacco Free NYS, 2018). Second, states that are legalizing cannabis for adult use are already using public education campaigns to inform people about the new law, prevent accidental ingestion and overconsumption of edibles, discourage driving under the influence, and discourage use among people who are pregnant, breastfeeding, or under 21 years of age (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), 2019; Doonan SM. et al., 2020). Expanding public education campaigns to include equity messaging could promote public support for specific equity-focused cannabis policies and help states achieve their equity goals. At least one state is already taking this approach. In June 2022, the New York State Office of Cannabis Management released the first broadcast TV ad in the United States to address the issue of equity in cannabis as part of its Cannabis Conversations campaign. The ad highlights “how decades of cannabis overpolicing harmed Black and Latino New Yorkers, and the work [the New York State Office of Cannabis Management is] doing to address these devastating wrongs,” (New York State Office of Cannabis Management, 2022).

This study describes public support for equity-focused cannabis policies among New Jersey adults and assesses whether public education can be used to increase awareness of and support for equity-focused cannabis policies. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the use of public education to increase support for equity in cannabis policy.

METHODS

Study Design and Implementation

We conducted an online survey with an embedded experimental design to (1) assess public support for equity-focused cannabis policy among New Jersey adults and (2) determine whether a simple, educational message can increase support for equity-focused cannabis policy. From August 23 through September 15, 2021, we recruited 893 New Jersey adults aged 21 and older through advertisements on Twitter and Facebook (hereafter referred to as “social media”). The people depicted in the social media advertisements were racially diverse. The study protocol, social media advertisements, consenting documents, survey, and educational messages were approved by RTI’s IRB. The 15-minute survey was optimized for use on mobile devices.

People who clicked on the social media advertisements were asked to provide informed consent before taking the study screener. The screener included multiple checks to verify that respondents were residents of New Jersey aged 21 or older. Specifically, we began the screener by asking people “How old are you?” and “What state do you live in?” Later in the screener, we asked people their date of birth and 5-digit zip code. We screened people out of the survey if their age and location data did not align. We asked about race and cannabis use in the screener to intentionally create a nonprobability sample that was racially diverse and had good variation across cannabis use status, with a specific goal to oversample Black and Latine people. We consider it a priority to emphasize the perspectives of Black and Latine people in research about possible reparative actions relating to the War on Drugs, because Black and Latine people have been, and still are, disproportionately harmed by the War on Drugs. Another goal was to ensure that we developed a sample with a range of cannabis use experiences. Because people who use cannabis continue to be stigmatized and criminalized as a result of cannabis policy, we believe it is important to emphasize their perspectives in research that may shape future policy. Although data are weighted to the population of New Jersey, oversampling specific populations leads to greater precision of estimates for these populations. We monitored screener data daily during data collection and closed the survey to specific populations as they became sufficiently represented in the sample for the purposes of our study.

To protect cannabis consumers, who were reporting on cannabis use and purchasing behaviors that were legal in New Jersey at the time of the survey but illegal at the federal level, we advised respondents to take care to protect their survey responses. We also programmed the survey so that one question appeared on each screen, and it was not possible to move backward within the survey. This practice protects respondent privacy by locking each survey response immediately upon entry.

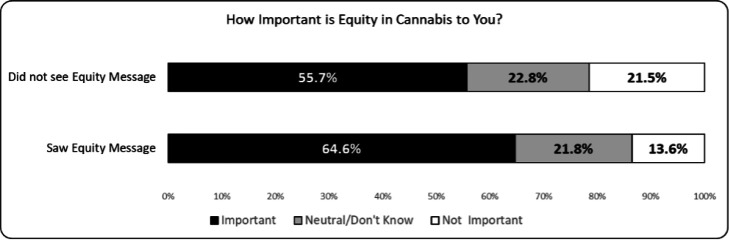

We asked eligible respondents to provide informed consent a second time to take the main survey. After providing consent, respondents were randomly assigned to a control or experimental condition. We asked all respondents whether they had ever heard of the concept of equity in relation to cannabis legalization. After measuring unaided awareness of equity, all participants swiped through three screens that defined equity (Figure 1). Participants in the control condition then went on to the rest of the survey. Participants in the experimental condition had to swipe or click through seven screens with equity-focused messaging (Figure 1) before proceeding to the remainder of the survey. All questions in the main survey were skippable.

Figure 1.

Messages Viewed by Study Participants

We implemented fraud prevention and detection measures developed by our organization’s social media data collection team to ensure that respondents were humans (not bots), were located in New Jersey, were age 21 or older, and each took the survey only once. We screened out respondents who failed either of two mid-survey attention checks. We sent all respondents who completed the survey a $15 digital gift card.

Measures

Key study measures were (1) awareness of the concept of equity in cannabis policy; (2) perceived importance of equity in cannabis policy; and (3) agreement with specific equity-focused cannabis policies. We measured awareness of the concept of equity by asking, “Have you heard the term ‘equity’ used in the context of marijuana legalization before?” Response options were “yes,” “no,” “I don’t know,” and “prefer not to answer.” We measured perceived importance of equity by asking, “Overall, how important is equity in cannabis to you?” Response options took the form of a 5-point scale ranging from “very important” to “not at all important,” including a neutral response. We measured agreement with specific equity-focused policies by stating, “New Jersey should provide the following types of support to people who have been arrested for marijuana, and who now want to participate in the legal cannabis industry…(1) Priority in licensing (have your cannabis business license application reviewed before other people); (2) License application assistance (help getting together everything needed to apply for a cannabis business license); (3) Technical assistance (help getting together everything needed to start a cannabis business); (4) Low-interest loans (loans that don’t cost much to pay back); (5) Grants (funding that doesn’t need to be paid back).” Response options took the form of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” including a neutral response and the response “I don’t know.” Measures in this section were randomized to preclude order effects.

Analysis

We used weighted data to produce estimates for unaided awareness of equity, importance of equity, and support for specific equity-focused policies, because we wanted these estimates to reflect the population of New Jersey. Sampling weights were created to remove bias, making the data more representative of the New Jersey population of adults 21 years of age and older. The steps for calculating weights were to (1) calculate the base weight; (2) calibrate to known population totals; and (3) evaluate the unequal weight effect (UWE). We adjusted the weights to sum to the population totals for demographic categories that are correlated with study outcomes to reduce bias stemming from oversampling of cannabis consumers, coverage error, differential nonresponse, and different selection probabilities. The five distributions used in the calibration adjustment were gender, age category, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and age category by marijuana use. Data were weighted using the U.S. Census National Characteristics Vintage 2021 file, the 2020 American Community Survey (ASC) 5-Year Summary File, and the 2018–2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. A hot deck imputation procedure was used to replace 18 missing values for variables used in the calibration weighting.

To simplify our reporting of unaided awareness of equity, importance of equity, and support for specific equity-focused policies, we combined “strongly agree” and “agree” response options and “strongly disagree” and “disagree” response options. We also combined “neutral” and “I don’t know” responses on the principle that both types of responses represent an opportunity for public education.

We used unweighted data to test whether outcomes were statistically significantly different by study condition. It is not necessary to weight experimental data in which participants are randomly assigned to a condition; weighting can reduce the precision of estimates (Miratrix et al., 2018). Given that the purpose of significance testing was to compare differences across study conditions rather than to describe a population, we opted to use unweighted data for this component of the study. To increase the variation for each outcome variable, we used means (rather than proportions) for these analyses. We calculated mean perceived importance and mean agreement for each outcome based on a 5-point scale, using unweighted data and t-tests. We conducted a sensitivity analysis using Welch’s t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to confirm that results were stable and consistent across these tests and their assumptions. In the results section of this paper, we report results from the t-tests. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Approximately half of the study participants (n = 429) were assigned to the control condition and the other half (n = 434) to the experimental condition. The study sample’s racial makeup was 44% white, 23% Asian, 18% Black, 12% multiracial or another race, and 2% American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander. Census data for New Jersey indicate that in 2020 the state was 71% white, 15% Black, 10% Asian, 2% multiracial, and 1% American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (United States Census Bureau, 2021). In terms of ethnicity, the study sample was 25% Latine, compared to 19% in the state of New Jersey (United States Census Bureau, 2021). The study sample consisted of current (past 30-day) cannabis consumers (33%), people who have used cannabis but not in the past 30 days (32%), and people who have never used cannabis (35%). Monitoring the Future survey data from 2020 indicate that, among young adults aged 19 to 30, 27% were past 30-day cannabis consumers, 37% have used cannabis, but not in the past 30 days, and 36% have never used cannabis (Schulenberg et al., 2021). However, these national estimates are likely greater than the prevalence of cannabis use in New Jersey, because we know that young adults use cannabis at higher rates than older people and the mean age of our study participants is 39 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020b). Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that just under 10% of New Jerseyans 18 and older report being a past 30 day cannabis consumer (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021). Thus, our study sample has greater representation of Black and Latine individuals and includes a greater proportion of cannabis consumers than the population of New Jersey. Detailed, unweighted sample characteristics overall and by study condition are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Unweighted Study Sample, Overall and by Condition

| Overall | Experimental | Control | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.8 | 39.4 | 38.3 | 0.28 |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Female | 56.1% | 54.8% | 57.3% | 0.46 |

| Male | 41.8% | 43.3% | 40.3% | 0.37 |

| Genderqueer/Other | 2.1% | 1.8% | 2.3% | 0.62 |

| Are you Hispanic or Latino? (Yes) | 24.9% | 25.1% | 24.7% | 0.89 |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.6% | 1.8% | 1.4% | 0.61 |

| Asian | 23.4% | 22.8% | 24.0% | 0.68 |

| Black | 18.3% | 18.7% | 17.9% | 0.79 |

| Native Hawaiian | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.41 |

| White | 43.7% | 44.0% | 43.4% | 0.85 |

| Other/Multiracial | 12.3% | 12.2% | 12.4% | 0.95 |

| Have you ever used MJ in any form? (Yes) | 65.1% | 65.2% | 65.0% | 0.96 |

| Have you used MJ in the past 30 days? (Yes) | 33.3% | 32.3 % | 34.3% | 0.53 |

| Highest grade or level of school completed? | ||||

| High school, GED, or less* | 21.3% | 24.2% | 18.4% | 0.04* |

| Some college or bachelor’s degree | 59.4% | 56.5% | 62.5% | 0.07 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 19.2% | 19.4% | 19.1% | 0.93 |

| How would you describe your overall political philosophy? | ||||

| Very or somewhat conservative | 20.5% | 22.4% | 18.6% | 0.18 |

| Moderate | 36.2% | 36.4% | 35.9% | 0.88 |

| Very or somewhat liberal | 37.7% | 36.6% | 38.7% | 0.53 |

| None of the above | 5.7% | 4.6% | 6.8% | 0.17 |

Note. MJ = marijuana; * = p < .05; ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001

Unaided Awareness of the Concept of Equity in Cannabis Policy

More than half of participants (58.7%) had not heard of equity in the context of cannabis policy, and another 16.5% said they did not know or preferred not to answer. Thus, only about one-quarter of participants (24.9%) had heard of equity in regard to cannabis policy. We asked this question before participants were routed to a study condition, and there was not a statistically significant difference in responses by condition (24.9% experimental condition; 24.8% control condition).

Importance of Equity in Cannabis Policy

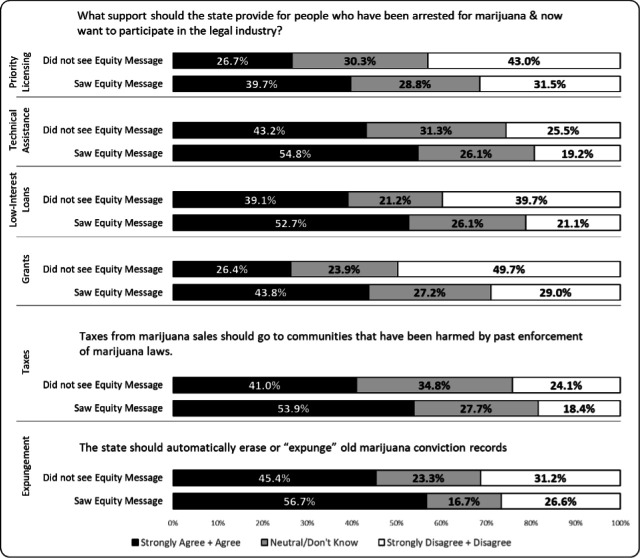

Among participants in the experimental condition (indicated as “Saw message” in the figure) 64.6% perceived equity in cannabis to be important, compared with 55.7% of those in the control condition (“Did not see message”) (Figure 2). More than 20% of participants in both conditions endorsed a “neutral” or “don’t know” response. To express the data in a way that better facilitates significance testing, mean perceived importance was 4.06 in the experimental condition and 3.87 in the control condition (t = 2.41, p < 0.05) (data not shown in figure). Means are based on a 5-point scale.

Figure 2.

Importance of Equity in Cannabis

Support for Specific Equity-Focused Policies

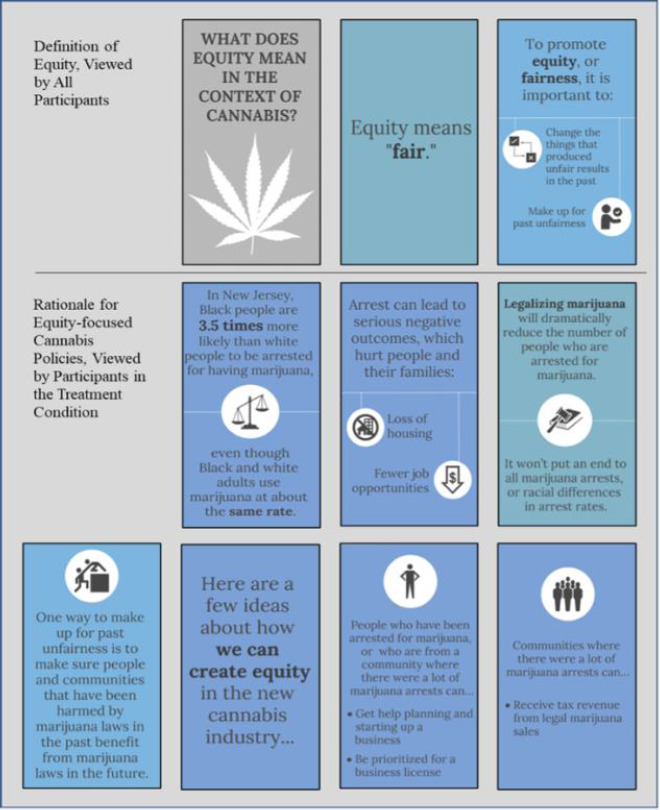

For each of the six equity-focused policies we studied, a greater proportion of participants in the experimental condition agreed with the policy relative to those in the control condition. Across the six policies, agreement in the experimental condition (“Saw message”) ranged from 39.7% to 56.7%, compared to a range of 26.4% to 45.4% in the control condition (“Did not see message”) (Figure 3). Approximately 20% to 35% of participants in both conditions endorsed a “neutral” or “don’t know” response.

Figure 3.

Agreement with Specific Equity-Focused Cannabis Policies

We calculated mean agreement with each policy approach (not shown in the figure) to conduct significance testing. For two of the six policies, mean agreement between experimental and control conditions was statistically significant. The policies for which we observed statistically significant differences by condition related to state support for people who have been arrested for cannabis, and now want to participate in the legal cannabis industry. Mean agreement that the state should provide priority licensing to this population was 3.26 in the experimental condition and 3.04 in the control condition (t = 2.73, p < 0.01). Mean agreement that the state should provide grants was 3.42 in the experimental condition and 3.12 in the control condition (t = 3.68, p < 0.001). Means are based on a 5-point scale.

DISCUSSION

This study provides preliminary support that states that are prioritizing equity in cannabis policy may be able to use public education to educate the public about the rationale for an equity focus and increase support for specific equity-focused policies. Two aspects of the data presented here suggest that this topic area is one in which public education could have a substantial impact. First, a very small proportion of New Jersey adults (25%) had heard of the concept of equity in cannabis policy. When a concept is relatively new, it is easier for public messaging to have a large impact on beliefs about and perceptions of that concept (Davis et al., 2016). Second, a substantial proportion of study participants endorsed a “neutral” or “don’t know” response when asked about their support for specific equity-focused policies. We have found that it is easier to shift beliefs and perceptions when they are not strongly held (Davis et al., 2016). These two findings—low unaided awareness of the concept and substantial neutral/don’t know responses—reflect the novelty of the concept of equity in cannabis policy and an opportunity for public education. Cannabis regulators, public health professionals, and people working to advance racial justice may be able to advance state equity goals and remedy some of the harm from the War on Drugs by expanding existing or planned public education campaigns to include equity messages.

One unpublished study provides context for our findings. A 2020 survey of 240 New Jerseyans aged 18 and older found that 60% of respondents agreed that New Jersey should implement a loan or grant fund to support those negatively impacted by the War on Drugs; 78% agreed that New Jersey should prioritize expungement of prior cannabis records (Azad et al., 2020). These estimates are higher than our control condition results, in which 45% supported expungement, 39% supported loans, and 26% supported grants for those harmed by past enforcement of marijuana policy. The difference in results may be explained by different study methodologies.

This study has a number of limitations. First, we used social media recruitment to invite participants to this study. A limitation of this recruitment method is that it produces a nonprobability sample; in this case, a study sample that is not representative of the people of the state of New Jersey. Furthermore, social media recruitment may systematically exclude people living in communities that were formerly redlined due to differential broadband access (Armstrong-Brown et al., 2021). In this way, social media recruitment (and online data collection) can exacerbate systemic racism. However, a benefit of this method is that it makes it easier to include specific populations of interest (Guillory et al., 2016; Guillory et al., 2018). Probability samples often do not produce a sufficient sample of Black and Latine participants, which historically has translated into a lack of evidence about the effects of public health interventions for these populations (Allen et al., 2011). By their nature, state-level probability samples require investigators to spend the majority of their data collection budget collecting data from white people. Thus, we believe it is important to embrace emerging data collection methods like social media recruitment when engaged in research designed to dismantle systemic racism. Second, the study was conducted with New Jersey adults; findings may not be generalizable to other states. Third, we measured message effects immediately following message exposure, and therefore do not know whether effects are enduring. Fourth, we forced message exposure to participants in the experimental condition, achieving a level of exposure that no real-world campaign could replicate (Hornik, 2002). Fifth, because our measure of unaided awareness of the concept of equity did not specify “social equity” it is possible that some participants interpreted our question as relating to stocks or shares in cannabis companies. Sixth, the equity message conveyed to participants in the experimental condition represented multiple ideas, including three equity-focused policy approaches, and required study participants to read quite a bit of text. A public education campaign that focused on a primary message and made use of effective message characteristics may be able to produce stronger effects (Niederdeppe et al., 2008). Seventh, public education campaigns that seek to change knowledge and beliefs in novel topic areas tend to have a greater influence than those that seek to create change in topic areas that are more well-known (Davis et al., 2016). Thus, the effects of equity-focused messaging may be greater in states that implement them first, and effects may diminish as public knowledge about equity in cannabis becomes more widespread.

A great deal more research is needed to understand public perceptions of and support for equity-focused policy, as well as whether equity-focused cannabis policies can mitigate some of the harms caused by the War on Drugs. An important area for future research will be identifying effective message characteristics for this policy area. As equity-focused cannabis policies are implemented, we will be better-positioned to evaluate the effects of those policies on individuals and communities that have been harmed by the War on Drugs.

Funding and Acknowledgements

This paper was funded by RTI International.

This study was created and conducted with support from Andrew Freeman, Jessica Speer, Allie Rothschild, Jessica Sobolewski, Kim Hayes, Dr. Matthew Farrelly, Dr. James Nonnemaker, Burton Levine, Anna MacMonegle, Dr. Jennifer Duke, Dr. Barrett Montgomery, and Dr. Gary Zarkin. Thank you to Shaleen Title, Esq., for reviewing our survey instrument; to Tauhid Chappell and Reverend Charles Boyer for talking with us about this idea; and to Shellery Ebron and the Innovation Team at RTI International for support of this project. Thank you to Dr. Stephanie Hawkins and Dr. Megan Comfort of RTI’s Transformative Research Unit for Equity (TRUE) for reviewing this concept and manuscript with an equity lens. Thank you to Teyonna Downing and Virginia Ferguson for helping to prepare this manuscript, and to our editor, Christina Rodriguez. We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers; their thoughtful comments improved this manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- Acker, J., Arkin, E., Leviton, L., Parsons, J., & Hobor, G. (2019). Mass incarceration threatens health equity in America. R. W. J. Foundation. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/01/mass-incarceration-threatens-health-equity-in-america.html [Google Scholar]

- Alang, S., McAlpine, D., McCreedy, E., & Hardeman, R. (2017, May). Police brutality and Black health: Setting the agenda for public health scholars. American Journal of Public Health, 107(5), 662–665. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow. Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J., Vallone, D., & Richardson, A. (2011). Reducing tobacco-related health disparities: Using mass media campaigns to prevent smoking and increase cessation in underserved populations. In Lemelle A., Reed W., & Taylor S. (Eds.), Handbook of African American Health: Social and Behavioral Interventions. Springer Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J. A., Davis, K. C., Kamyab, K., & Farrelly, M. C. (2015, Feb). Exploring the potential for a mass media campaign to influence support for a ban on tobacco promotion at the point of sale. Health Education Research, 30(1), 87–97. 10.1093/her/cyu067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2013). The War on Marijuana in Black and White. https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/1114413-mj-report-rfs-re11.pdf

- Armstrong-Brown, J., Humphrey, J., & Sussman, L. (2021). The long arm of redlining: Health inequities in the digital divide. The Medical Care Blog. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, N. F., Bell, C. A., Bolaji, T. T., Dacosta-Reyes, R. H., Decker, R. S., Dos Santos, P. C., Forst, A. M., Gaffney, K. M., Harvey, L. M., Hussein, N. L., Kunkle, C. L., Langone, S. R., Petzinger, B. C., Tomaselli, A. V., Upchurch, A. S., McNabb, M., Ritter, D. J., Ogen, M., & Scott, S. (2020). The Future of Cannabis in New Jersey: A report prepared by the students of Rider University’s reefer madness course, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2007. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, July 11). Public Health Surveillance: preparing for the future. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/improving-surveillance/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE). (2019). Overview. Retail Marijuana Education Program (RMEP). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1a96G6zjZMRUd2cbHo3iz8LClakWQU-0e/view [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (2016). The Regulation and Taxation of Marijuana Act. Retrieved November 30 from https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2016/Chapter334

- Cooper, H. L. (2015). War on Drugs policing and police brutality. Substance Use and Misuse, 50(8-9), 1188–1194. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1007669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. C., Allen, J., Duke, J., Nonnemaker, J., Bradfield, B., Farrelly, M. C., Shafer, P., & Novak, S. (2016). Correlates of marijuana drugged driving and openness to driving while high: Evidence from Colorado and Washington. PLoS One, 11(1), e0146853. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan, S. M., Sinclair, C., Curley, M. G., & Johnson J. K. (2020). More About Marijuana Public Awareness Campaign Effectiveness. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, E., Greytak, E., Madubuonwu, B., Sanchez, T., Beiers, S., Resing, C., Fernandez, P., & Galai, S. (2020). A Tale of Two Countries. Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform. American Civil Liberties Union. https://www.aclu.org/report/tale-two-countries-racially-targeted-arrests-era-marijuana-reform [Google Scholar]

- Firth, C. L., Maher, J. E., Dilley, J. A., Darnell, A., & Lovrich, N. P. (2019). Did marijuana legalization in Washington State reduce racial disparities in adult marijuana arrests? Substance Use and Misuse, 54(9), 1582–1587. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1593007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub, A., Johnson, B. D., & Dunlap, E. (2007). The Race/Ethnicity Disparity in Misdemeanor Marijuana Arrests in New York City. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(1), 131–164. 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00426.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillory, J., Kim, A., Murphy, J., Bradfield, B., Nonnemaker, J., & Hsieh, Y. (2016). Comparing Twitter and online panels for survey recruitment of e-cigarette users and smokers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(11), e288. 10.2196/jmir.6326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillory, J., Wiant, K. F., Farrelly, M., Fiacco, L., Alam, I., Hoffman, L., Crankshaw, E., Delahanty, J., & Alexander, T. N. (2018). Recruiting hard-to-reach populations for survey research: Using Facebook and Instagram advertisements and in-person intercept in LGBT bars and nightclubs to recruit LGBT young adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(6), e197. 10.2196/jmir.9461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunadi, C., & Shi, Y. (2022, Jan). Cannabis decriminalization and racial disparity in arrests for cannabis possession. Social Science & Medicine, 293, 114672. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, R. (2002). Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change (H.R, Ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Jahangeer, K. (2019). Fees and Fines: The Criminalization of Poverty. Public Lawyer Articles. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, S. M., Sharapova, S. R., Beasley, D. D., & Hsia, J. (2016). Cigarette smoking among inmates by race/ethnicity: impact of excluding African American young adult men from national prevalence estimates. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(suppl_1), S73–S78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. R., Kapadia, F., Geller, A., Mazumdar, M., Scheidell, J. D., Krause, K. D., Martino, R. J., Cleland, C. M., Dyer, T. V., Ompad, D. C., & Halkitis, P. N. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in "stop-and-frisk" experience among young sexual minority men in New York City. PLoS One, 16(8), e0256201. 10.1371/journal.pone.0256201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J., & Seattle Times. (2012). Voters approve I-502 legalizing marijuana. The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/voters-approve-i-502-legalizing-marijuana/

- Martinez, M. (2022). On Java with Jimmy by James Hills. #mentalhealthMondays/MLK Day/Monday, January 17, 2022 with Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5BIGiyINoA

- Massoglia, M., & Remster, B. (2019). Linkages Between Incarceration and Health. Public Health Reports, 134(1_suppl), 8S-14S. 10.1177/0033354919826563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miratrix, L., Sekhon, J., Theodoridis, A., & Campos, L. (2018). Worth weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments. Political Analysis, 26, 275–291. 10.1017/pan.2018.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Natoli, L. J., Vu, K. L., Sukhija-Cohen, A. C., Engeran-Cordova, W., Maldonado, G., Galvin, S., Arroyo, W., & Davis, C. (2021). Incarceration and COVID-19: Recommendations to curb COVID-19 disease transmission in prison facilities and surrounding communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18). 10.3390/ijerph18189790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York State Office of Cannabis Management. (2022). OCM and Social Equity. New York State Office of Cannabis Management. Retrieved July 11 from https://cannabis.ny.gov/cannabis-conversations [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe, J., Bu, Q. L., Borah, P., Kindig, D. A., & Robert, S. A. (2008). Message design strategies to raise public awareness of social determinants of health and population health disparities. Milbank Quarterly, 86(3), 481–513. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00530.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, H. F., Orr, M. F., Wang, A., Cano, M. A., Vaughan, E. L., Harvey, L. M., Essa, S., Torbati, A., Clark, U. S., Fagundes, C. P., & de Dios, M. A. (2020, Nov 1). Racial and gender inequities in the implementation of a cannabis criminal justice diversion program in a large and diverse metropolitan county of the USA. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 216, 108316. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg, J. E., Patrick, M. E., Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Miech, R. A. (2021). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2020. Volume II, College Students & Adults Ages 19-60. Institute for Social Research. https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/mtf-vo12_2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, B. E., Grucza, R. A., & Plunk, A. D. (2021). Association of racial disparity of cannabis possession arrests among adults and youths with statewide cannabis decriminalization and legalization. JAMA Health Forum, 2(10), e213435. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, A. (2021). Finally, marijuana is legal! Now, let’s build an equitable and inclusive market. Opinion. NJ.Com. https://www.nj.com/opinion/2021/02/finally-marijuana-is-legal-now-lets-build-an-equitable-and-inclusive-market-opinion.html

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020a). 2019 NSDUH Detailed Tables, Table 1.25B. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-detailed-tables

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020b). 2019 NSDUH Detailed Tables, Table 1.27B. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). 2019-2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Model-Based Prevalence Estimates (50 States and the District of Columbia). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-2020-nsduh-state-prevalence-estimates

- The Legal Aid Society. (2021). NYPD Data: People of Color Subject to More Than 94% of Marijuana Arrests. [Google Scholar]

- Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act, Illinois, (2019). https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs5.asp?ActID=3992&ChapterID=35

- New Jersey Cannabis Regulatory, Enforcement Assistance, and Marketplace Modernization Act., (2021). https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/Bills/2020/PL21/16_.PDF?_gl=1*1ezps1q*_ga*NDgzODQ0NzM4LjE2NDE1OTY5OTA.*_ga_MK89HXF6NQ*MTY0NDMzNjk0MC4zLjAuMTY0NDMzNjk0MC4w

- The Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act (“MRTA”). S.854 (Krueger)/A.1248 (Peoples-Stokes), (2021). https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2021/s854a

- Title, S. (2021). Fair and Square: How to Effectively Incorporate Social Equity Into Cannabis Laws and Regulations. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/so13/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3978766

- Tobacco Free NYS. (2018). Our Kids Have Seen Enough Tobacco [Advertisement]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JW0sB8kiero.

- United States Census Bureau. (2021). QuickFacts New Jersey Retrieved December 1 from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NJ