Abstract

Background

Unmet need for medical care is common among Medicare beneficiaries, but less is known whether unmet need differs between those with high and low levels of need.

Objective

To examine unmet need for medical care among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries by level of care need.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We included 29,123 FFS Medicare beneficiaries from the 2010–2016 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.

Main Measures

Our outcomes included three measures of unmet need for medical care. We also examined the reasons for not obtaining needed medical care. Our primary independent variable was a categorization of groups by levels of care need: those with low need (the relatively healthy and those with simple chronic conditions) and those with high need (those with minor complex chronic conditions, those with major complex chronic conditions, the frail, and the non-elderly disabled).

Results

The rates of reporting unmet need for medical care were highest among the non-elderly disabled (23.5% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] for not seeing a doctor despite medical need, 23.8% [95% CI: 20.0–27.6] for experiencing delayed care, and 12.9% [95% CI: 10.2–15.6] for experiencing trouble in getting needed care). However, the rates of reporting unmet need were relatively low among the other groups (ranging from 3.1 to 9.9% for not seeing a doctor despite medical need, from 3.4 to 5.9% for experiencing delayed care, and from 1.9 to 2.9% for experiencing trouble in getting needed care). The most common reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need was concerns about high costs for the non-elderly disabled (24%), but perception that the issue was not too serious was the most common reason for the other groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Our findings suggest the need for targeted policy interventions to address unmet need for non-elderly disabled FFS Medicare beneficiaries, especially for improving affordability of care.

KEY WORDS: Medicare, unmet need, disability, access to care, affordability

Evidence suggests that unmet need for medical care has not improved over the past two decades in the United States (US).1 This may have significant implications for health as unmet need for medical care has been linked to poor health status.2–5 Unmet need is particularly relevant to Medicare beneficiaries who tend to have high care need based on elderly or disabled status. Research found that 7% of older adults in the US postponed or skipped care, which is higher than 1–4% in other high-income countries.6 Unmet need can arise from various factors including financial and non-financial barriers to health care.7,8

Developing effective policy recommendations to address unmet need for Medicare beneficiaries is challenging due to the current state of limited knowledge. Unmet need tends to be higher among those with high need than those with low need.9 However, a recent report from the National Academy of Medicine indicates that the population with high need comprises a heterogeneous group of individuals with a diverse array of conditions.10 As care need can be heterogeneous based on clinical relevance, this suggests that there may be variations in unmet need for medical care among those with high need. The most common reason for unmet need for medical care is concern among patients about out-of-pocket costs.11 However, there may be variations in the reasons for unmet need for medical care by level of care need. A better understanding of unmet need for medical care across and within levels of care need is critically important from a policy perspective because it allows us to identify more targeted interventions and provide insight into effective and actionable policy and systems recommendations.10,12

In this study, we examined unmet need for medical care among fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries with high and low levels of need. Following prior research, we categorized FFS Medicare beneficiaries based on level of care need and identified groups of those with low need and those with high need.10,12 Then, we conducted the following three analyses. First, we examined unmet need for medical care by group based on level of care need. To understand the underlying mechanism for unmet need, we examined the reasons for not obtaining needed medical care and care-seeking behavior by level of care need. To determine whether unmet need is present, we examined health care use by level of care need. We hypothesized that those with high need would have a greater unmet need for medical care, exhibit poorer care-seeking behavior, and use health care services less frequently than those with low need than those with low need. However, there would be variations even among those with high need.

METHODS

Data and Study Sample

We employed a repeated cross-sectional study design using data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) and Area Health Resource Files (AHRF). The MCBS collects comprehensive information on demographic, socioeconomic, and health characteristics for a nationally representative sample of both institutionalized and non-institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries. Specifically, the data links Medicare claims to survey-reported data, and therefore provides detailed information on access to care and health care use. As the MCBS for 2014 was never released, we used all publicly available data from 2010 to 2016. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board and received a waiver of informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization as the data were deidentified.

We identified and included Medicare beneficiaries with 12 months of continuous enrollment in FFS Medicare. We excluded Medicare beneficiaries without continuous enrollments in Parts A and B benefits, those who died within the year, and those who enrolled in Medicare Advantage at any time in the year.

Outcome Variables

Our primary outcome variables included three binary measures of unmet need for medical care: not seeing a doctor despite medical need, delayed care, and trouble in getting needed care. These variables were constructed based on the survey information. Participants were asked to answer the following questions: “during this year, did you have any health problem or condition about which you think you should have seen a doctor or other medical person, but did not?”, “during the previous year, did you have any delay in care due to cost?”, and “during the previous year, did you have any trouble in getting health care needs met?”.

We also included five secondary outcomes. To understand the underlying mechanism for unmet need, we examined the main reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need as well as care-seeking behavior.11 Specifically, we included the following mutually exclusive eight reasons for not seeing a doctor despite medical need: thought it would cost too much, did not think the problem was serious, trouble finding or getting to a doctor, time/schedule or personal conflicts, thought a doctor could not do much about health problem, was afraid of finding out what was wrong, a doctor would not accept insurance, or other. Also, we included two binary measures of care-seeking behaviors: trying to keep sickness to self when sick and doing almost anything to avoid going to a doctor. To understand the consequences of unmet need, we included two binary measures of health care use: having a primary care visit and having a specialist visit. Following prior research,13 we identified evaluation and management visits from beneficiaries’ physician claims based on the Current Procedural Terminology codes and measured contact with primary care providers and specialists for face-to-face evaluation and management visits. The first three variables were constructed based on the survey information, and the last two variables were constructed based on claims data.

Independent Variables

Our key independent variable was a categorization of groups by levels of care need. We followed prior research to identify care need for each beneficiary based on demographic and health status (International Classification of Diseases diagnosis and/or procedure codes) from claims data.10,12 Specifically, we categorized FFS Medicare beneficiaries into six mutually exclusive groups and defined the relatively healthy and those with simple chronic conditions as those with low need and those with minor complex chronic conditions, those with major complex chronic conditions, the frail, and the non-elderly disabled as those with high need (Table 1). First, we defined the relatively healthy as those without any chronic condition and limited activities of daily living (ADL). Next, we identified those with chronic illness using a set of clusters of 29 disease categories used in prior research.12 Then, we defined those with simple chronic conditions as those with one to five non-complex chronic conditions, those with minor complex chronic conditions as those with one to two complex chronic conditions and less than six non-complex chronic conditions, and those with major complex chronic conditions as those with three or more complex conditions or at least six non-complex conditions. We defined the frail as those who were older than 65 years of age and had at least two claims-based frailty diagnoses proposed by prior research.14 Finally, we defined the non-elderly disabled as those who were younger than 65 years of age and eligible for Medicare based on the presence of disability or ESRD as determined by the Social Security Administration.

Table 1.

Definition of Population Segmentation Based on Level of Care Need

| Criteria | Relatively healthy | Simple chronic | Minor complex chronic | Major complex chronic | Frail | Non-elderly disabled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care need | Low | Low | High | High | High | High |

| Age | Age ≥ 65 | Age ≥ 65 | Age ≥ 65 | Age ≥ 65 | Age ≥ 65 | Age < 65 |

| Health conditions | Without any chronic conditions (including non-complex and complex chronic conditions) and no limited activities of daily living | With 1–5 non-complex chronic conditions, but without any complex chronic conditions | With 1–2 complex chronic conditions and less than 6 non-complex chronic conditions | With 3 or more complex chronic conditions or at least 6 non-complex chronic conditions | With 2 or more conditions based on a modified list of the following 12 specific claims-based diagnoses potentially indicative of frailty (gait abnormality, malnutrition, failure to thrive, cachexia, debility, difficulty walking, history of fall, muscle wasting, muscle weakness, decubitus ulcer, senility, or durable medical equipment use) | Disabled or end-stage renal disease determined by the Social Security Administration |

To adjust for differences in individual-level characteristics, we included the following individual-level variables from the survey: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance status, limited English proficiency, marital status, metropolitan area residence, census region of residence, general health status compared with same-age people, overall health status compared to 1 year ago, limited social activities, and number of ADL limitations. To adjust for differences in area-level characteristics, we included the following county-level variables: population size, percentage of those older than 65 years old, percentage of Medicare and Medicaid dual-eligible beneficiaries, average FFS Medicare spending, average Hierarchical Condition Categories risk score, Medicare Advantage penetration rates, unemployment rates, median household income, percentage of residents with incomes below poverty, number of hospital beds, number of medical doctors, number of primary care physicians, and specialist physicians per 1000 residents.

Statistical Analysis

We first summarized sample characteristics by group based on levels of care need. We then estimated adjusted outcomes using linear probability regression models. To examine variations in outcome among FFS Medicare beneficiaries by levels of care need, we conducted a linear probability model while adjusting for individual-level and county-level characteristics and the six groups by levels of care need. Then, we estimated the adjusted rates of the outcome by group based on levels of care need, which allowed for comparison of the outcome variable by groups that are similar across the set of independent variables. We conducted the analysis for each measure of unmet need for medical care, care-seeking behaviors, and health care use.

To understand the underlying mechanism for unmet needs for medical care among FFS Medicare beneficiaries by levels of care need, we reported unadjusted proportions for each of the eight reasons for not seeing a doctor despite medical need by levels of care need.

For all analyses, we included year-fixed effects. We employed complex sample design with cross-sectional sampling weights provided by the MCBS to produce nationally representative estimates.

RESULTS

Our final sample included a total of 29,123 FFS Medicare beneficiaries. The care need groups were 13.0% for the relatively healthy, 25.1% with simple chronic conditions, 25.4% with minor complex chronic conditions, 11.6% with major complex chronic conditions, 5.4% frail, and 19.4% non-elderly disabled (Table 2). There were two notable findings for sample characteristics. First, we found differential patterns of socioeconomic status between those with high need and those with low need. Those with higher need were more likely to have lower education level, have lower income level, have limited English proficiency, have limited social activities, and have more ADL limitations than those with lower need. Second, the non-elderly disabled had substantially different characteristics than the other three groups with high need. The non-elderly disabled were more likely to be racial/ethnic minority groups, have less education, report lower income level, be eligible for Medicaid, have limited English proficiency, report poor general health status compared with people at comparable ages, have limited social activities, and have more ADL limitations, and are less likely to have Medigap than the other three groups with high need.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries by Level of Care Need

| Characteristics | Relatively healthy (N = 3794) | Simple chronic (N = 7317) | Multiple chronic (N = 7389) | Major complex chronic (N = 3379) | Frail ( N = 1580) | Non-elderly disabled (N = 5664) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level characteristics, N (%) | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| < 65 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5664 (100.0) | < .001 |

| 65–69 | 903 (23.7) | 1286 (17.5) | 1172 (15.8) | 478 (14.2) | 140 (8.9) | 0 (0.0) | < .001 |

| 70–74 | 1128 (29.7) | 1810 (24.7) | 1574 (21.3) | 632 (18.7) | 188 (11.9) | 0 (0.0) | < .001 |

| 75–79 | 788 (20.8) | 1490 (20.4) | 1552 (21.0) | 705 (20.9) | 284 (18.0) | 0 (0.0) | < .001 |

| ≥ 80 | 975 (25.7) | 2731 (37.3) | 3091 (41.8) | 1564 (46.3) | 968 (61.3) | 0 (0.0) | < .001 |

| Female | 1946 (51.3) | 4509 (61.6) | 4124 (55.8) | 1618 (47.9) | 1055 (66.8) | 2572 (45.4) | < .001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3253 (85.7) | 6324 (86.4) | 6118 (82.8) | 2784 (82.4) | 1307 (82.7) | 3783 (66.8) | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 245 (6.5) | 459 (6.3) | 650 (8.8) | 307 (9.1) | 140 (8.9) | 1192 (21.0) | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 62 (1.6) | 104 (1.4) | 102 (1.4) | 37 (1.1) | 30 (1.9) | 74 (1.3) | 0.221 |

| Hispanic | 196 (5.2) | 361 (4.9) | 396 (5.4) | 201 (5.9) | 82 (5.2) | 522 (9.2) | < .001 |

| Others | 90 (2.4) | 189 (2.6) | 242 (3.3) | 125 (3.7) | 38 (2.4) | 290 (5.1) | < .001 |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 453 (11.9) | 1238 (16.9) | 1685 (22.8) | 958 (28.4) | 415 (26.3) | 1454 (25.7) | < .001 |

| High school completion | 1229 (32.4) | 2562 (35.0) | 2625 (35.5) | 1210 (35.8) | 543 (34.4) | 2533 (44.7) | < .001 |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 874 (23.0) | 1506 (20.6) | 1498 (20.3) | 605 (17.9) | 307 (19.4) | 1279 (22.6) | < .001 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 643 (16.9) | 1048 (14.3) | 881 (11.9) | 334 (9.9) | 170 (10.8) | 267 (4.7) | < .001 |

| Advanced degree | 588 (15.5) | 944 (12.9) | 675 (9.1) | 259 (7.7) | 134 (8.5) | 97 (1.7) | < .001 |

| Income | |||||||

| Less than $25,000 | 1006 (26.5) | 2317 (31.7) | 2900 (39.2) | 1420 (42.0) | 751 (47.5) | 4378 (77.3) | < .001 |

| $25,000–$40,000 | 1783 (47.0) | 4118 (56.3) | 3359 (45.5) | 1590 (47.1) | 636 (40.3) | 904 (16.0) | < .001 |

| More than $40,000 | 929 (24.5) | 595 (8.1) | 862 (11.7) | 220 (6.5) | 103 (6.5) | 175 (3.1) | < .001 |

| Insurance | |||||||

| Medicaid | 184 (4.8) | 615 (8.4) | 967 (13.1) | 591 (17.5) | 296 (18.7) | 3464 (61.2) | < .001 |

| Medigap | 1357 (35.8) | 2543 (34.8) | 2642 (35.8) | 1116 (33.0) | 563 (35.6) | 301 (5.3) | < .001 |

| Prescription drug coverage | 1931 (50.9) | 3748 (51.2) | 4533 (61.3) | 2019 (59.8) | 999 (63.2) | 4594 (81.1) | < .001 |

| Limited English proficiency | 86 (2.3) | 383 (5.2) | 466 (6.3) | 327 (9.7) | 226 (14.3) | 863 (15.2) | < .001 |

| Married | 2210 (58.2) | 4042 (55.2) | 3903 (52.8) | 1764 (52.2) | 618 (39.1) | 1443 (25.5) | < .001 |

| Metro area | 2803 (73.9) | 5151 (70.4) | 4772 (64.6) | 2120 (62.7) | 1130 (71.5) | 3750 (66.2) | < .001 |

| Census region of residence | |||||||

| New England | 144 (3.8) | 264 (3.6) | 263 (3.6) | 115 (3.4) | 57 (3.6) | 172 (3.0) | 0.233 |

| Middle Atlantic | 505 (13.3) | 838 (11.5) | 888 (12.0) | 396 (11.7) | 185 (11.7) | 748 (13.2) | < .001 |

| East North Atlantic | 561 (14.8) | 1230 (16.8) | 1476 (20.0) | 757 (22.4) | 283 (17.9) | 1035 (18.3) | < .001 |

| West North Atlantic | 260 (6.9) | 573 (7.8) | 609 (8.2) | 260 (7.7) | 114 (7.2) | 403 (7.1) | 0.028 |

| South Atlantic | 854 (22.5) | 1614 (22.1) | 1592 (21.5) | 693 (20.5) | 390 (24.7) | 1388 (24.5) | < .001 |

| East South Central | 311 (8.2) | 697 (9.5) | 741 (10.0) | 373 (11.0) | 175 (11.1) | 570 (10.1) | < .001 |

| West South Central | 401 (10.6) | 784 (10.7) | 723 (9.8) | 365 (10.8) | 195 (12.3) | 549 (9.7) | 0.19 |

| Mountain | 360 (9.5) | 572 (7.8) | 509 (6.9) | 177 (5.2) | 83 (5.3) | 348 (6.1) | < .001 |

| Pacific | 398 (10.5) | 745 (10.2) | 588 (8.0) | 243 (7.2) | 98 (6.2) | 451 (8.0) | < .001 |

| Poor general health status compared with same-age people | 9 (0.2) | 132 (1.8) | 301 (4.1) | 351 (10.4) | 191 (12.1) | 1078 (19.0) | < .001 |

| Good overall health status compared to 1 year ago | 3587 (94.5) | 6069 (82.9) | 5780 (78.2) | 2237 (66.2) | 875 (55.4) | 4151 (73.3) | < .001 |

| Limited social activities | 235 (6.2) | 1651 (22.6) | 2394 (32.4) | 1619 (47.9) | 1022 (64.7) | 3263 (57.6) | < .001 |

| Number of ADL limitations | |||||||

| 0 | 3794 (100.0) | 4012 (54.8) | 3367 (45.6) | 1029 (30.5) | 207 (13.1) | 1582 (27.9) | < .001 |

| 1–2 | 0 (0.0) | 1329 (18.2) | 1555 (21.0) | 689 (20.4) | 274 (17.3) | 1379 (24.3) | < .001 |

| 3 + | 0 (0.0) | 1976 (27.0) | 2467 (33.4) | 1661 (49.2) | 1099 (69.6) | 2703 (47.7) | < .001 |

| County-level characteristics, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Population | 838,435.7 (1,476,622.6) | 771,273.9 (1,446,021.5) | 660,267.2 (1,301,522.1) | 727,782.8 (1,525,500.2) | 824,035.6 (1,427,449.0) | 710,629.0 (143,4501.1) | < .001 |

| % of 65 year and older | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | < .001 |

| % of dual-eligible Medicare beneficiaries | 20.0 (8.4) | 20.7 (8.3) | 21.2 (8.5) | 22.1 (8.8) | 21.5 (8.9) | 23.2 (8.9) | < .001 |

| Average fee-for-service Medicare spending | 10,637.4 (1649.9) | 10,888.8 (1750.4) | 10,777.8 (1741.5) | 11,043.7 (1784.4) | 11,205.4 (1782.2) | 10,940.2 (1706.6) | < .001 |

| HCC risk score | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | < .001 |

| Medicare Advantage penetration | 22.7 (14.7) | 19.6 (13.7) | 19.7 (13.7) | 19.4 (13.7) | 20.4 (13.9) | 20.5 (14.4) | < .001 |

| Unemployment rate | 7.1 (2.8) | 8.4 (2.6) | 8.1 (2.8) | 8.7 (2.7) | 8.2 (2.6) | 8.3 (2.8) | < .001 |

| Median household income | 57,175.3 (16,791.6) | 53,140.7 (14,682.8) | 52,471.5 (14,769.5) | 50,055.3 (13,287.8) | 52,362.5 (14,760.3) | 50,373.4 (13,725.0) | < .001 |

| % of residents with incomes below poverty | 14.5 (5.5) | 15.4 (5.5) | 15.6 (5.7) | 16.3 (5.5) | 15.8 (5.6) | 16.7 (5.9) | < .001 |

| Hospital beds per 1000 residents | 2352.2 (4057.5) | 2278.2 (4108.8) | 1983.3 (3821.7) | 2224.7 (4436.9) | 2509.4 (4200.8) | 2192.6 (4146.3) | < .001 |

| Medical doctors per 1000 residents | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.5) | 2.3 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.3 (1.6) | < .001 |

| Primary care physicians per 1000 residents | 3.2 (1.8) | 3.0 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.7) | < .001 |

| Specialists per 1000 residents | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | < .001 |

ESRD end-stage renal disease, ADL activities of daily living, HCC hierarchical condition category

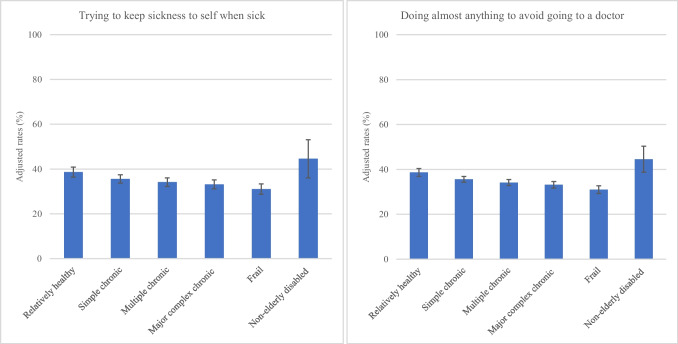

Our adjusted analyses found variations in unmet need for medical care by levels of care need (Fig. 1). Particularly, the adjusted rates of reporting unmet need were highest among the non-elderly disabled (23.5% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] for not seeing a doctor despite medical need, 23.8% [95% CI: 20.0–27.6] for experiencing delayed care, and 12.9% [95% CI: 10.2–15.6] for experiencing trouble in getting needed care). However, the rates of reporting unmet need were relatively low among the other groups (ranging from 3.1% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] to 9.9% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] for not seeing a doctor despite medical need, from 3.4% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] to 5.9% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] for experiencing delayed care, and from 1.9% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] to 2.9% [95% CI: 19.8–27.3] for experiencing trouble in getting needed care).

Figure 1.

Adjusted rates of unmet need for medical care among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries by level of care need. Rates and 95% confidence intervals (represented by the whiskers) were estimated using a linear probability regression model while controlling for individual-level and area-level characteristics and the six groups by level of care need. Using the predictive marginal effects at representative values estimated from the linear probability regression model, we estimated the adjusted rates of the outcome by group based on level of care need.

The most common reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need differed between the non-elderly disabled and the other groups. Specifically, concerns about high costs were the most common reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need among the non-elderly disabled (24.0%). However, the most common reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need was perception that the issue was not too serious among the other groups (46.9%, 38.4%, 40.0%, 38.9%, and 39.7%, for the relatively healthy, those with simple chronic conditions, those with minor complex chronic conditions, those with major complex chronic conditions, and the frail) (Table 3). The other six reasons were relatively minor, and this pattern was consistently observed across all groups.

Table 3.

The Main Reasons for Not Seeing a Doctor Despite Medical Need Among Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries by Level of Care Need

| % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasons for not seeing a doctor despite medical need | Relativelyhealthy | Simple chronic | Multiple chronic | Major complex chronic | Frail | Non-elderly disabled |

| Did not think problem was serious | 46.9 | 38.4 | 40.0 | 38.9 | 39.7 | 22.1 |

| Thought it would cost too much | 10.2 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 24.0 |

| Trouble finding or getting to doctor | 4.8 | 8.0 | 5.3 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 6.9 |

| Time/schedule or personal conflicts | 5.4 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 7.3 | 4.0 | 6.8 |

| Thought doctor could not do much about problem | 8.8 | 17.2 | 13.9 | 12.5 | 8.7 | 12.2 |

| Was afraid of finding out what was wrong | 4.1 | 3.8 | 7.2 | 5.9 | 11.1 | 10.3 |

| Doctor would not accept insurance | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 3.9 |

| Other | 17.7 | 13.0 | 14.7 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 13.7 |

ESRD end-stage renal disease

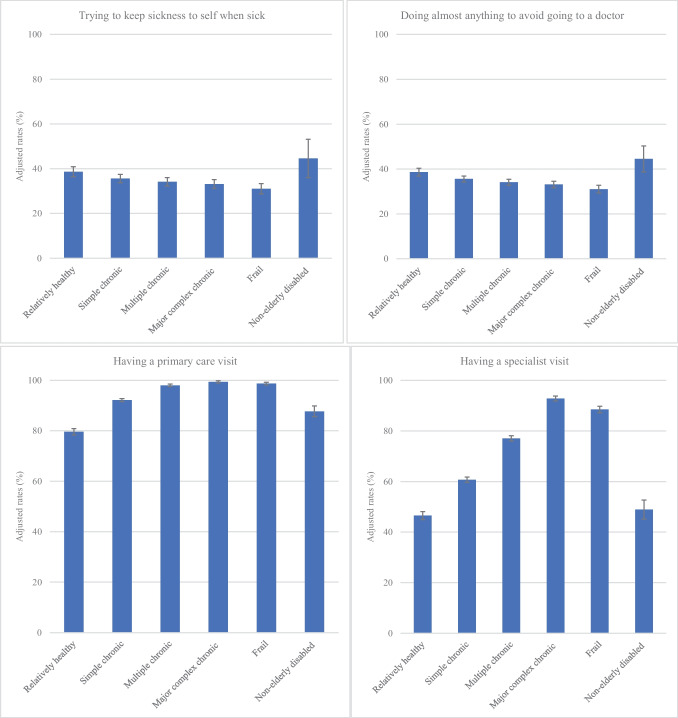

We also found variations in care-seeking behavior and health care use by levels of care need (Fig. 2). A notable finding is suboptimal care-seeking behavior among the non-elderly disabled (44.6% [95% CI: 27.7–61.4] for trying to keep sickness to self when sick, 45.8% [95% CI: 34.5–57.1] for doing almost anything to avoid going to a doctor, 87.7% [95% CI: 83.6–91.9] for having a primary care visit, and 48.9% [95% CI: 41.6–56.3] for having a specialist visit). Except for the non-elderly disabled, we found that those with high need had better care-seeking behavior such as trying to keep sickness to self when sick and doing almost anything to avoid going to a doctor than those with low need. Also, health care use was higher among those in the other groups with high need than those with low need.

Figure 2.

Adjusted rates of care-seeking behavior and health care use among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries by level of care need (continued). Rates and 95% confidence intervals (represented by the whiskers) were estimated using a linear probability regression model while controlling for individual-level and area-level characteristics and the six groups by level of care need. Using the predictive marginal effects at representative values estimated from the linear probability regression model, we estimated the adjusted rates of the outcome by group based on level of care need.

DISCUSSION

We found that the rates of reporting unmet need for medical care was the highest among the non-elderly disabled, but the rates of reporting unmet need were relatively low among the other groups. The most common reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need was concern about high costs for the non-elderly disabled, but perception that the issue was not too serious was the most common reason for the other groups.

Our findings for high unmet need for medical care among the non-elderly disabled suggest the importance of developing targeted interventions to address the unique needs of the non-elderly disabled. Prior research found that this population consumes a significant amount of health care resources.12 Despite their high costs, unmet need for medical care was substantial among the non-elderly disabled, suggesting that higher healthcare spending does not necessarily lead to better care experience. This population not only suffers from medical risk factors but also is likely to suffer from social risk factors, suggesting significant health and social needs. There is evidence that the non-elderly disabled experienced a high number of co-occurring medical, behavioral health, and social complexity.12 As medical care is necessary but not sufficient to improve health, there is increasing recognition that social risk factors play a critical role in improving health.15 Improving economic security is of particular interest due to substantial differences in income. Thus, there is a need to develop targeted interventions to provide coordinated care through integration of medical and non-medical care services to satisfy the unique needs of the non-elderly disabled.

Our findings also contribute to improving understanding of the underlying mechanism for unmet need. We found that the most common reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need was perception that the issue was not too serious overall. Patient-driven factors such as avoiding doctor visits, fear of learning a diagnosis, and trying to keep one’s sickness to themselves were associated with low health care use and high unmet need.16,17 Thus, it is important to identify effective interventions aimed at addressing patient-centered factors. System-level interventions that have shown preliminary promise for improving care-seeking behavior are improving health literacy and providing community-based care.18–23 Notably, the reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need due to concerns about high costs was relatively higher among the non-elderly disabled. This finding may be attributable to limited Medicare benefits. Medicare generally does not cover long-term care, dental, vision, or hearing care.24,25 Moreover, Medicare has significant cost-sharing requirements with no limit on out-of-pocket spending that can impact compliance with a care plan.26,27 Thus, gaps in Medicare coverage may lead to concerns about affordable health care, especially for the non-elderly disabled. This population may receive care through Medicaid, but there are substantial variations in state-level Medicaid coverage, possibly leading to variations in access to care and unmet need for medical care at the state level.28,29

Our findings provide policy implications for addressing unmet need for medical care, especially for the non-elderly disabled. First, expanding Medicare coverage could be effective at reducing concerns about affordable health care coverage.24,25 There have been calls to expand Medicare coverage of dental, vision, and hearing services. This coverage expansion could lower out-of-pocket costs for these services,30 possibly leading to lower unmet need for medical care. Second, developing models that integrate the financing and delivery of services covered in Medicare and Medicaid could enable to address social needs both inside and outside of health care settings.31,32 As the non-elderly disabled have significant health and social needs, addressing the lack of coordination between Medicare and Medicaid benefits could improve the quality of care for this population and mitigate unmet need for medical care. Third, Medicare-Medicaid dual-eligibles comprised a significant percentage of the non-elderly disabled group. A recent government report indicated that this population may transition to dual-eligible status by spending down their income to qualify for Medicaid.33 This report also pointed out that dual-eligibles may be more likely to have complex care needs such as severe mental illness and dementia. Therefore, our findings that this group has unmet needs for care, especially motivated by concerns about cost, may signal the need for policy efforts to assist this care need group as they transition to dual-eligible status.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we relied on survey data, and thus, our findings may be subject to self-reporting errors. Second, we employed a cross-sectional survey design, and therefore, our findings should not be interpreted as inferring a causal relationship. Third, we assumed that Medicare beneficiaries experienced unmet need for medical care on the date of interview. However, there may be a difference between when Medicare beneficiaries were interviewed and experienced unmet need for medical care. Fourth, we treated the non-elderly disabled as a homogeneous population, but there may be important variations that could provide a more nuanced interpretation. For example, those in institutionalized settings such as long-term-care facilities may have different experiences of unmet needs for care compared to those receiving home- and community-based services. Fifth, our sample was limited to FFS Medicare beneficiaries, raising some concerns about generalizability. Finally, we controlled for individual- and area-level characteristics, but we could not control for all potential characteristics that might affect unmet need for medical care.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that the rates of reporting unmet need for medical care were the highest among the non-elderly disabled, but the rates of reporting unmet need were relatively low among the other groups. The most common reason for not seeing a doctor despite medical need was concern about high costs for the non-elderly disabled, but perception that the issue was not too serious was the most common reason for the other groups. Our findings suggest the need for targeted policy interventions to address unmet need for the non-elderly disabled FFS Medicare beneficiaries, especially for improving affordability of care.

Funding

This study was supported by a Korea University grant (K2224171).

Data Availability

As we utilized the MCBS limited dataset, which must be securely stored, sharing the data itself is not feasible.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: None

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hawks L, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, Gaffney A, McCormick D. Trends in unmet need for physician and preventive services in the United States, 1998–2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):439–448. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso J, Orfila F, Ruigómez A, Ferrer M, Antó JM. Unmet health care needs and mortality among Spanish elderly. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(3):365–370. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kortrijk HE, Kamperman AM, Mulder CL. Changes in individual needs for care and quality of life in Assertive Community Treatment patients: an observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:306. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lasalvia A, Bonetto C, Malchiodi F, Salvi G, Parabiaghi A, Tansella M, Ruggeri M. Listening to patients’ needs to improve their subjective quality of life. Psychol Med. 2005;35(11):1655–1665. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko H. Unmet healthcare needs and health status: panel evidence from Korea. Health Policy. 2016;120(6):646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson G, Cicchiello A, Shah A, Doty MM, Williams II RD. When costs are a barrier to getting health care: reports from older adults in the United States and other high-income countries. The Commonwealth Fund. Published October 1, 2021. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2021/oct/when-costs-are-barrier-getting-health-care-older-adults-survey.

- 7.Eurostat. Methodological guidelines and description of EU-SILC target variables PH010: general health. Published September 12, 2020. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/f8853fb3-58b3-43ce-b4c6-a81fe68f2e50/Methodological%20guidelines%202021%20operation%20v4%2009.12.2020.pdf.

- 8.Allin S, Masseria C. Unmet need as an indicator of health care access. Eurohealth. 2009;15(3):7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan J, Abrams MK, Doty MM, Shah T, Schneider EC. How high-need patients experience health care in the United States. Findings from the 2016 Commonwealth Fund survey of high-need patients. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2016;43:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long P, Abrams M, Milstein A, Anderson G, Lewis Apton K, Lund Dahlberg M, Whicher D, eds. Effective care for high-need patients: opportunities for improving outcomes, value, and health. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine. 2017. https://nam.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2017/06/Effective-Care-for-High-Need-Patients.pdf. [PubMed]

- 11.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Unmet needs for health care: comparing approaches and results from international surveys. Published January 2020. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Unmet-Needs-for-Health-Care-Brief-2020.pdf.

- 12.Joynt KE, Figueroa JF, Beaulieu N, Wild RC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Segmenting high-cost Medicare patients into potentially actionable cohorts. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5(1–2):62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston KJ, Wen H, Joynt Maddox KE. Lack of access to specialists associated with mortality and preventable hospitalizations of rural Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):1993–2002. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DH, Schneeweiss S. Measuring frailty using claims data for pharmacoepidemiologic studies of mortality in older adults: evidence and recommendations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):891–901. doi: 10.1002/pds.3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolf SH, Braveman P. Where health disparities begin: the role of social and economic determinants—and why current policies may make matters worse. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):1852–1859. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindly OJ, Geldhof GJ, Acock AC, Sakuma KK, Zuckerman KE, Thorburn S. Family-centered care measurement and associations with unmet health care need among US children. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(6):656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park S, Stimpson JP. Trends in self-reported forgone medical care among Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(12):e214299. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavingia R, Jones K, Asghar-Ali AA. A systematic review of barriers faced by older adults in seeking and accessing mental health care. J Psychiatr Pract. 2020;26(5):367–382. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S, Langellier BA, Meyers DJ. Association of health insurance literacy with enrollment in traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and plan characteristics within Medicare Advantage. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146792. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40(5):395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacLeod S, Musich S, Gulyas S, et al. The impact of inadequate health literacy on patient satisfaction, healthcare utilization, and expenditures among older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38(4):334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Coninck L, Bekkering GE, Bouckaert L, Declercq A, Graff MJL, Aertgeerts B. Home- and community-based occupational therapy improves functioning in frail older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1863–1869. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SM, Wallace E, O'Dowd T, Fortin M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;1(1):CD006560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willink A, Davis K. Coverage of dental, vision, and hearing services in Medicare: the window of opportunity is open. JAMA. 2021;326(15):1475–1476. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed NS, Lin FR, Willink A. Changes to Medicare policy needed to address hearing loss. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(11):e213582. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cubanski J, Koma W, Damico A, Neuman T. How much do Medicare beneficiaries spend out of pocket on health care? Kaiser Family Foundation; Published November 4, 2019. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-do-medicare-beneficiaries-spend-out-of-pocket-on-health-care/.

- 27.Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Rothman RL, Pinheiro LC, Roberts AW, Shah ND, Walunas TL, Wood WA, Zuckerman AD, Zullig LL, Keating NL. Many Medicare beneficiaries do not fill high-price specialty drug prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(4):487–496. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stimpson JP, Pintor JK, McKenna RM, Park S, Wilson FA. Association of Medicaid expansion with health insurance coverage for disabled persons. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197136. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong X, Gindling TH, Miller NA. Effects of the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage, health care access, and use for people with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(1):101180. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephenson J. As Congress weighs expanded coverage, Medicare patients bear large out-of-pocket costs for dental, hearing care. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(9):e213697. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole MB, Nguyen KH. Unmet social needs among low-income adults in the United States: associations with health care access and quality. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(Suppl 2):873–882. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keohane, LM, Hwang A. Integrating Medicare and Medicaid for dual-eligible beneficiaries through managed care: proposed 2023 Medicare Advantage regulations. Health Affairs Forefront. Published February 24, 2022. Accessed April 14, 2022.

- 33.Feng Z, et al. Analysis of Pathways to Dual Eligible Status. Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. May 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

As we utilized the MCBS limited dataset, which must be securely stored, sharing the data itself is not feasible.