Abstract

During the screening for Rhodobacter capsulatus mutants defective in xanthine degradation, one Tn5 mutant which was able to grow with xanthine as a sole nitrogen source only in the presence of high molybdate concentrations (1 mM), a phenotype resembling Escherichia coli mogA mutants, was identified. Unexpectedly, the corresponding Tn5 insertion was located within the moeA gene. Partial DNA sequence analysis and interposon mutagenesis of regions flanking R. capsulatus moeA revealed that no further genes essential for molybdopterin biosynthesis are located in the vicinity of moeA and revealed that moeA forms a monocistronic transcriptional unit in R. capsulatus. Amino acid sequence alignments of R. capsulatus MoeA (414 amino acids [aa]) with E. coli MogA (195 aa) showed that MoeA contains an internal domain homologous to MogA, suggesting similar functions of these proteins in the biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactor. Interposon mutants defective in moeA did not exhibit dimethyl sulfoxide reductase or nitrate reductase activity, which both require the molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide (MGD) cofactor, even after addition of 1 mM molybdate to the medium. In contrast, the activity of xanthine dehydrogenase, which binds the molybdopterin (MPT) cofactor, was restored to wild-type levels after the addition of 1 mM molybdate to the growth medium. Analysis of fluorescent derivatives of the molybdenum cofactor of purified xanthine dehydrogenase isolated from moeA and modA mutant strains, respectively, revealed that MPT is inserted into the enzyme only after molybdenum chelation, and both metal chelation and Mo-MPT insertion can occur only under high molybdate concentrations in the absence of MoeA. These data support a model for the biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactor in which the biosynthesis of MPT and MGD are split at a stage when the molybdenum atom is added to MPT.

Molybdoenzymes are ubiquitous and essential for almost all organisms, from bacteria to plants and animals. All molybdoenzymes (with the exception of nitrogenase) contain the molybdenum cofactor (Moco), which consists of a unique molybdopterin (MPT) complexing one Mo atom via a dithiolene group and which has the same principle structure in eubacteria, archaebacteria, and eukaryotes (29). The biosynthesis of this unique cofactor is complex and requires the multistep synthesis of the MPT moiety and the subsequent incorporation of Mo into MPT. Biosynthesis of Moco is best studied in Escherichia coli, and it was shown that the gene products of five distinct gene loci, moa, mob, mod, moe, and mog, are required (30). Two gene products of the moa locus, MoaA and MoaC, are suggested to be involved in the first steps of Moco biosynthesis, leading to a precursor molecule (precursor Z) of Moco. MPT synthase, encoded by moaD and moaE, catalyzes the conversion of precursor Z to MPT by introducing the sulfur which is finally needed to coordinate Mo. MoeB, one gene product of the moe operon, is required for activation of MPT synthase by sulfurylation (27). The physiological role of the second gene product of the moe operon, MoeA, is not yet established, although MoeA is suggested to be involved in activation of molybdenum by sulfurylation (8). Molybdenum is transported into the cell via a high-affinity molybdate transport system, encoded by the mod gene products (6). Molybdoenzyme activities in mogA mutants can be partially restored to 10 to 13% of the wild-type level by growing these mutants at high molybdate concentrations (43). Therefore, the mogA gene product, characterized as a molybdochelatase, is suspected to be involved in the last step of Moco formation, namely in the insertion of Mo into MPT (15). In E. coli, molybdopterin is further modified by covalent attachment of a GMP moiety to the terminal phosphate group of molybdopterin via a pyrophosphate link, to form the molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide (MGD) cofactor (13).

The phototrophic purple bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus contains two well-characterized molybdoenzymes containing Moco, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) reductase and xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) (20, 37). In contrast to E. coli molybdoenzymes, all of which contain MGD, it was shown that R. capsulatus harbors molybdoenzymes coordinating different variants of Moco. The crystal structure of DMSO reductase from R. capsulatus revealed that the molybdenum atom is coordinated by two MGD cofactors (37); in contrast, XDH contains the MPT cofactor, the form of the cofactor present in all eukaryotic molybdoenzymes (20). Although the cofactor of these molybdenum enzymes is characterized in detail, some gene products involved in Moco biosynthesis in R. capsulatus remain to be identified. Nevertheless, Moco biosynthesis for R. capsulatus XDH and DMSO reductase is expected to proceed by a pathway similar to the Moco biosynthesis pathway in E. coli.

During the screening for R. capsulatus mutants unable to degrade xanthine, we obtained one mutant in which XDH activity could be restored to wild-type levels by high concentrations of molybdate (20), whereas DMSO reductase and nitrate reductase activities could not be restored under these conditions. The corresponding mutation was mapped within the moeA gene of R. capsulatus. In this report, we describe a detailed analysis of R. capsulatus MoeA and demonstrate that the pathways of MPT and MGD biosynthesis split at a step when molybdenum is added to the cofactor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. R. capsulatus strains were grown in RCV medium as described by Klipp et al. (17). Methods for conjugational plasmid transfer between E. coli and R. capsulatus and the selection of mutants, anaerobic growth conditions, and antibiotic concentrations were as previously described (17, 18).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| S17-1 | RP4-2 (Tc::Mu) (Km::Tn7) integrated into the chromosome | 39 |

| JM83 | Host for pUC plasmids | 45 |

| R. capsulatus | ||

| B10S | Spontaneous Smr mutant of R. capsulatus B10 | 17 |

| KS36 | ΔnifHDK::Spc | 46 |

| R438I | modA::Gm, insertion mutant of KS36 | 46 |

| Xan-17 | moeA::Tn5 | 20 |

| R487 | ΔntrY::Gm, deletion mutant of KS36 | This work |

| R488 | ClaI::Gm, insertion mutant of KS36 | This work |

| R507 | ΔmoeA/ntrY::Gm, deletion mutant of KS36 | This work |

| R509I/II | moeA::Km, insertion mutant of KS36 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNF3 | nifH promoter plasmid | 28 |

| pPHU231 | Broad-host-range vector | 31 |

| pPHU235 | Broad-host-range lacZ fusion vector | 10 |

| pFR400 | pPHU231 carrying nap genes of R. sphaeroides | 31 |

| pSL157 | pPHU231 carrying xdhABC expressed from nifH promoter derived from pNF3 | This work |

| pWKR500 | 7.3-kb EcoRI fragment carrying moeA cloned into pUC8 | This work |

| pWKR513 | moeA-lacZ fusion vector; EcoRI-PstI fragment carrying the 5′ end of moeA cloned into pPHU235 | This work |

DNA biochemistry.

DNA isolation, restriction enzyme analysis, agarose gel electrophoresis, and cloning procedures were performed by use of standard methods (35). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Pharmacia or MBI Fermentas and used as recommended by the suppliers.

DNA sequencing.

DNA sequence analysis was carried out with an Auto Read sequencing kit (Pharmacia) according to the protocol devised by Zimmermann et al. (47). Sequence data were obtained and processed by using the A.L.F. DNA sequencer (Pharmacia LKB) as instructed by the manufacturer by using standard fluorescence-labelled primers and appropriate subclones of the 7.3-kb EcoRI fragment (pWKR500). The Staden programs were used for editing and translating DNA sequences (41). For homology searches in sequence databases, the BLAST algorithms (basic local alignment search tool [1]) were used. Sequence alignments were performed with the CLUSTAL W program (44).

Construction of R. capsulatus moeA mutant strains.

For the construction of R. capsulatus moeA interposon mutants, various wild-type fragments were cloned by standard methods (35) into mobilizable narrow-host-range vector plasmids. Suitable restriction sites were subsequently used to insert a gentamicin (9) or a kanamycin resistance gene (2). The resulting hybrid plasmids were mobilized from E. coli S17-1 into R. capsulatus by filter mating (23). Mutants were selected for the interposon-encoded resistance, and marker rescue was identified by loss of the vector-encoded resistance.

Construction of a moeA-lacZ fusion plasmid.

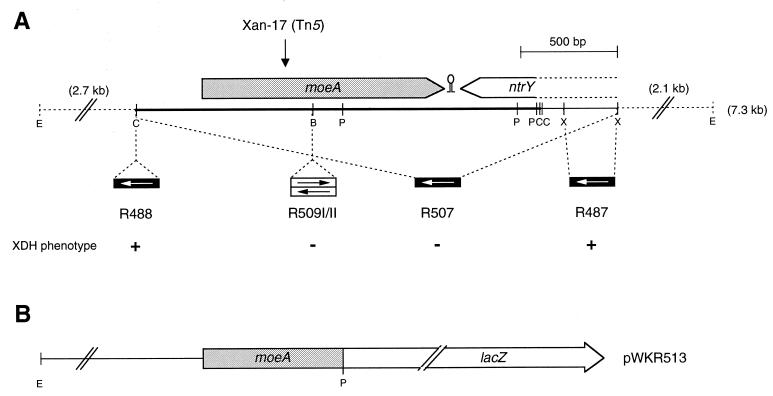

To create a translational moeA-lacZ fusion, an EcoRI-PstI fragment (Fig. 1B) carrying the 5′ part of R. capsulatus moeA was cloned into the polylinker of the broad-host-range lacZ fusion vector pPHU235 (10). The resulting replicative reporter plasmid was designated pWKR513.

FIG. 1.

Physical and genetic maps of the R. capsulatus moeA gene region. (A) The localizations of ORFs are given by arrows carrying their respective gene designations. The vertical arrow indicates the location of the Tn5 insertion in R. capsulatus mutant strain Xan-17. The 2,005-bp ClaI fragment sequenced in this study is marked by a heavy line, and a stem-loop structure located between moeA and ntrY is indicated. Below the map, the locations of interposon insertions are shown. The direction of transcription of interposon resistance genes are symbolized by arrows in boxes (gentamicin resistance gene, white arrow; kanamycin resistance gene, black arrow), indicating polar and nonpolar insertions. The ability of the corresponding R. capsulatus mutant strains to grow with xanthine as the sole nitrogen source is indicated by a plus or minus. (B) Construction of a translational moeA-lacZ fusion. In plasmid pWKR513, an EcoRI-PstI fragment was fused to the reporter gene lacZ located on the broad-host-range vector plasmid pPHU235. Abbreviations: B, BamHI; C, ClaI; E, EcoRI; P, PstI; X, XhoI.

β-Galactosidase assays.

To determine β-galactosidase activities of R. capsulatus strains carrying the translational moeA-lacZ reporter plasmid pWKR513, the corresponding strains were grown in RCV medium supplemented with tetracycline (0.25 μg/ml). Ammonium (final concentration, 10 mM), serine (10 mM), hypoxanthine (1 mM), and molybdate (0 to 1 mM) were added to the growth medium as described in the text. Following growth in the respective media to late exponential phase, β-galactosidase activities of R. capsulatus strains were determined by the sodium dodecyl sulfate-chloroform method (10, 25).

Enzyme assays.

XDH activity was assayed as described by Leimkühler et al. (20), with NAD as the electron acceptor. Nitrate reductase activity was analyzed by the method described by Garrett and Nason (5), and DMSO reductase activity was measured as described by McEwan et al. (24), with dithionite-reduced methyl viologen as the electron donor.

Enzyme purification.

To purify XDH from R. capsulatus KS36 and R507, a plasmid overexpressing the xdhABC genes was constructed. To uncouple xdh expression from its native promoter, the nifH promoter region derived from pNF3 (28) was cloned in front of xdhABC. In order to link the ATG start codons of nifH and xdhA, an NdeI restriction site was introduced into the ATG codon of xdhA by PCR mutagenesis. Subsequently, a SacI-HindIII fragment carrying the structural genes of XDH (xdhABC) expressed from the nifH promoter was cloned into the polylinker of the broad-host-range plasmid pPHU231 (31). The resulting hybrid plasmid was designated pSL157. This plasmid was introduced into the R. capsulatus moeA mutant strain R507 and into the corresponding parental strain KS36. Ten liters of the strains was grown under anaerobic, phototrophic conditions in 2-liter bottles containing RCV medium with 10 mM serine as the nitrogen source to induce the nifH promoter. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at late log phase after 40 h of growth, when the A660 reached 0.8. Cells were washed with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 2.5 mM dithiothreitol (buffer 1). Unless otherwise stated, all purification steps were carried out at 4°C and in buffer 1. Cell lysis was achieved by repeated passages through a French pressure cell (9,000 lb/in2); the suspension was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant was used as crude extract for enzyme purification. The crude extract was centrifuged at 100,000 × g in an ultracentrifuge for 1 h. The resulting supernatant was brought to 45% ammonium sulfate saturation at 4°C, and the suspension was centrifuged (16,000 × g, 30 min). The pellet was dissolved in the minimal volume of buffer 1 and dialyzed against the same buffer to remove ammonium sulfate. After dialysis, the ammonium sulfate fraction was electrophoresed by means of the model 491 Prep Cell system from Bio-Rad in a gel column (diameter, 28 mm) consisting of 4 ml of stacking gel (4% acrylamide) and 10 ml of separating gel (4% acrylamide). Electrophoresis was carried out at 12 W of constant power at 4°C. Fractions were collected in buffer 1, and those containing XDH were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration under vacuum. With this method, inactive XDH from R. capsulatus moeA mutants as well as active XDH from the parental strain KS36 or moeA mutants grown in the presence of 1 mM molybdate could be purified with a yield of approximately 700 μg. Protein concentrations were determined as described by Smith et al. (40).

For the purification of XDH from R. capsulatus modA mutant strain R438I, the xdhABC-overexpressing plasmid pSL157 was introduced into this strain. A 10-liter volume of the corresponding strain was grown under anaerobic, phototrophic conditions in 2-liter bottles containing molybdenum-free minimal medium (AK-NL) (36) with 10 mM serine as the nitrogen source. XDH was purified by ion-exchange chromatography and preparative gel electrophoresis as described by Leimkühler and Klipp (21). By this method, inactive XDH from the modA mutant of R. capsulatus was purified, with a yield of approximately 3 mg.

Gel electrophoresis.

Analytical polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried out in a discontinuous gel system (19). For nondenaturating polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, 4% acrylamide stacking gels and 6% acrylamide separating gels were used.

Moco analysis.

To analyze Moco present in XDH, the purified protein was subjected to a procedure which converts the Moco to its oxidized fluorescent degradation product (form A) after boiling the enzyme at pH 2.5 in the presence of iodine, as originally described by Johnson et al. (12). After treatment with alkaline phosphatase, dephospho-form A was further purified and desalted on 0.5-ml QAE-Sephadex columns. The column was washed with 10 ml of water. Dephospho-form A was subsequently eluted with 10 mM acetic acid and immediately analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). To obtain form A-GMP from R. capsulatus crude extracts, iodine treatment was carried out at room temperature and form A-GMP was eluted from the QAE-Sephadex column with 50 mM HCl by the method described by Joshi and Rajagopalan (14). HPLC was performed at room temperature with a Perkin-Elmer C18 reverse-phase column as described by Schwarz et al. (38). Comparable amounts of proteins were used for these analyses. The presence of form A in the respective fractions was verified by its absorption spectrum with a maximum in absorbance at 380 nm.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of a 2,005-bp ClaI DNA fragment encompassing the moeA coding region has been submitted to the EMBL nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AJ238348.

RESULTS

Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of a Tn5-containing EcoRI fragment from the R. capsulatus mutant strain Xan-17.

To identify R. capsulatus genes required for xanthine degradation, a random Tn5 mutagenesis was performed (20). Among 70,000 Tn5-induced R. capsulatus mutants, which were screened for the loss of ability to grow with xanthine as the sole nitrogen source, one mutant strain was observed (Xan-17) in which the xanthine-negative phenotype could be suppressed by high concentrations of molybdate (1 mM) in the medium (20). The phenotype of this mutant strain resembled the phenotype described for E. coli mutants defective in mogA, coding for a molybdochelatase (15). In E. coli mogA mutants, molybdoenzyme activities can be partially restored by growing these mutants at high molybdate concentrations. However, growth of these mutants at nearly toxic levels of molybdate (10 mM) resulted in only modest increases in nitrate reductase (43) and biotin sulfoxide reductase levels (3). In contrast, the ability of the R. capsulatus Tn5 mutant strain Xan-17 to grow with xanthine as the sole nitrogen source was restored to wild-type levels in medium supplemented with 1 mM molybdate (20). To identify the gene inactivated by the Tn5 insertion in R. capsulatus mutant Xan-17, a 7.3-kb Tn5-containing EcoRI fragment was cloned from chromosomal R. capsulatus DNA into pUC8. Figure 1A gives the physical and genetic map of the corresponding R. capsulatus gene region and the location of the Tn5 insertion. DNA sequence analysis of a 2,005-bp ClaI fragment (indicated in Fig. 1A) revealed the presence of one complete open reading frame (ORF) preceded by a typical ribosome binding site. This ORF encoded a putative protein of 414 amino acid residues with a deduced molecular mass of 42,589 Da. Surprisingly, the predicted amino acid sequence of this ORF showed a high degree of identity (35%) to the sequence of E. coli MoeA, a protein which is also involved in Moco biosynthesis. Downstream of R. capsulatus moeA, the 5′ end of another ORF transcribed in the opposite direction was identified. This ORF showed a high degree of identity in its predicted 122 C-terminal amino acids to Azorhizobium caulinodans NtrY, a histidine kinase of a two-component regulatory system involved in nitrogen level control (26).

Mutational analysis of the R. capsulatus moeA gene region.

To confirm that the molybdate-reparable phenotype of Tn5 mutant strain Xan-17 was indeed linked to the Tn5 insertion and not to secondary mutations, appropriate mutant strains carrying kanamycin interposon insertions (R509I and R509II) were constructed (Fig. 1A). The Xan− phenotype of these interposon mutant strains was suppressible by the addition of 1 mM molybdate to the medium, confirming that the Tn5 insertion was indeed responsible for this phenotype (data not shown).

To determine whether adjacent DNA fragments were also involved in Moco biosynthesis for R. capsulatus XDH, defined insertion mutations were constructed. For this purpose, an interposon encoding gentamicin resistance was inserted into different restriction sites (Fig. 1A). The corresponding R. capsulatus mutant strains (R487 and R488) were tested for their ability to use xanthine as the sole nitrogen source, revealing that neither the region upstream of moeA nor ntrY is required for xanthine degradation (Fig. 1A). As expected, the deletion mutant R507, in which a ClaI-XhoI fragment carrying moeA and the 5′ end of ntrY was exchanged for a gentamicin interposon, was unable to grow with xanthine as the sole nitrogen source. The results from the interposon mutagenesis revealed that moeA is the only gene in this region involved in Moco biosynthesis for R. capsulatus XDH. Thus, in contrast to E. coli moeA, R. capsulatus moeA is not located in a transcriptional unit together with moeB.

In order to study the regulation of moeA expression, a moeA-lacZ fusion was constructed. As shown in Fig. 1B, the moeA coding region was fused at the PstI site to lacZ, resulting in hybrid plasmid pWKR513 (Materials and Methods). To analyze moeA expression in different genetic backgrounds, pWKR513 was introduced into R. capsulatus wild-type, into several mutant strains carrying lesions in moeA, ntrY, modB, mobA, or xdHA, and into a mopA mopB double mutant. The corresponding strains were grown in media containing different amounts of molybdate (either none, 1 μM, or 1 mM) and different nitrogen sources (either ammonium, xanthine, or serine). However, under all conditions tested and in all mutant backgrounds, the moeA-lacZ fusion exhibited comparable β-galactosidase values, demonstrating a constitutive and very low expression of moeA (data not shown). These results indicate that expression of moeA is controlled neither in an autoregulatory circuit by MoeA itself nor by the putative histidine kinase NtrY. In addition, the molybdenum status of the cell has no influence on moeA expression, as demonstrated in mutant strains carrying lesions in the high-affinity molybdate uptake system (modB) (46) and in the molybdate-dependent repressor proteins MopA and MopB (18, 46). Furthermore, strains unable to synthesize MGD cofactors due to the lack of the MGD synthase MobA (22) or strains devoid of the MPT-containing xanthine dehydrogenase (xdhA) (20) were not affected in moeA expression.

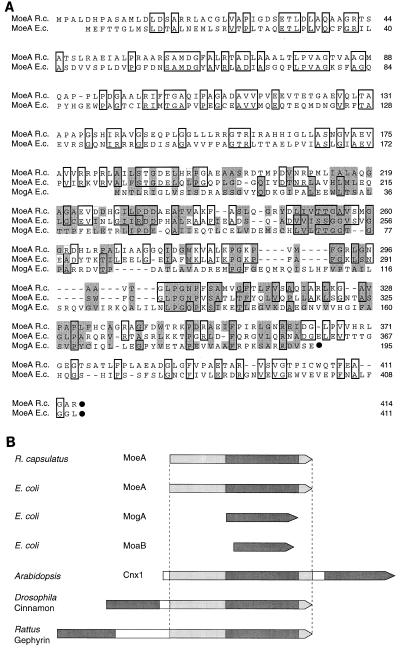

R. capsulatus MoeA is homologous to the E. coli Moco biosynthesis proteins MoeA and MogA and to the eukaryotic proteins Cnx1, Cinnamon, and Gephyrin.

The amino acid sequence alignment of R. capsulatus MoeA with E. coli MoeA is shown in Fig. 2A. The two proteins are similar in length (414 and 411 amino acids, respectively) and display 35% identity and 69% similarity over the entire length of the proteins. In addition, weak similarities of both MoeA proteins to E. coli MogA were identified (15% identity, 46% similarity). This alignment demonstrates that MoeA contains an internal MogA-like domain, which corresponds to amino acids 184 to 362 in R. capsulatus MoeA and amino acids 181 to 357 in E. coli MoeA. Another E. coli protein homologous to MogA and MoeA is encoded by moaB. The moaB gene in E. coli is located downstream of moaA, but the specific function of MoaB for Moco biosynthesis is unknown, and no mutants defective in moaB have been described yet (32). Furthermore, a moaB-like gene is absent in other organisms.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of R. capsulatus MoeA with E. coli MoeA and MogA. (A) Amino acid sequences were aligned for maximum matching by use of the CLUSTAL W program (44). The C-terminal ends of polypeptides are marked by black dots. Identical amino acids are boxed, and in addition, the similarity of amino acids between E. coli MogA, R. capsulatus MoeA, and E. coli MoeA is emphasized by shading. (B) Schematic overview of different bacterial and eukaryotic proteins showing similarities to E. coli MoeA and MogA. The E. coli MogA protein and MogA-like domains found in other proteins are indicated by dark gray shading. Protein domains showing similarities to E. coli MoeA are indicated by light gray shading.

Three eukaryotic proteins exhibiting homologies to MoeA and MogA are known: Cnx1 from Arabidopsis thaliana (42), Cinnamon from Drosophila melanogaster (16), and Gephyrin from Rattus norwegicus (4). As shown schematically in Fig. 2B, the amino-terminal domain (E-domain) of A. thaliana Cnx1 is homologous to MoeA and the carboxy-terminal domain (G-domain) is homologous to E. coli MogA (42). In D. melanogaster Cinnamon and R. norwegicus Gephyrin, the arrangement of the two domains is reversed in comparison to that of Cnx1. As found for MoeA of R. capsulatus and E. coli, an internal MogA-like domain was also identified in the E-domains (MoeA) of the eukaryotic proteins Cnx1, Cinnamon, and Gephyrin.

Molybdoenzyme activities in R. capsulatus moeA mutant strains.

As described previously (20), the inability of R. capsulatus moeA mutants to grow with xanthine as the sole nitrogen source was restored by the addition of 1 mM molybdate to the medium. This phenotype resembles the phenotype of E. coli mogA mutants. In contrast, even in the presence of high molybdate concentrations, no molybdoenzyme activity was observed in E. coli moeA mutants (11). This significant difference in the phenotype of moeA mutants from E. coli and R. capsulatus might be explained by the fact that E. coli harbors only MGD-containing molybdoenzymes whereas XDH from R. capsulatus was shown to contain the MPT cofactor (20). To study the role of R. capsulatus MoeA in biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor, the activity of DMSO reductase and nitrate reductase, both enzymes binding the MGD cofactor, was tested in R. capsulatus moeA mutants. To test nitrate reductase activity, plasmid pFR400 carrying the genes encoding the periplasmic nitrate reductase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides (31) was introduced into R. capsulatus. As shown in Table 2, the activities of XDH, DMSO reductase, and nitrate reductase were analyzed in the R. capsulatus moeA mutant strain R507 and compared to those of the corresponding parental strain KS36 (carrying a nifHDK deletion). Enzyme activities were determined as described in Material and Methods after 2 days of growth in medium containing either 1 μM or 1 mM molybdate. The parental strain KS36 contained active XDH regardless of the molybdate concentration, whereas the moeA mutant strain R507 required high molybdate concentrations in the growth medium to produce active XDH. In contrast, the MGD cofactor-containing enzymes nitrate reductase and DMSO reductase remained inactive in the R. capsulatus moeA mutant independent of the molybdenum concentration in the medium. In the parental strain KS36, DMSO reductase activity was 2.5-fold higher when cells were grown with 1 mM instead of 1 μM molybdate. A similar dependence of DMSO reductase activity on the molybdenum concentration of the medium has been observed by Bonnet and McEwan (2a). In conclusion, like E. coli MoeA, R. capsulatus MoeA is absolutely required for the biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor, whereas in contrast, the biosynthesis of the MPT cofactor of XDH was restored by the addition of 1 mM molybdate to the medium in a moeA mutant.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of enzyme activities of different molybdoenzymes in R. capsulatus moeA mutant strain R507 and the parental strain KS36

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Enzyme activity (U/mg)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthine dehydrogenaseb

|

Nitrate reductasec

|

DMSO reductased

|

|||||

| 1 μM Mo | 1 mM Mo | 1 μM Mo | 1 mM Mo | 1 μM Mo | 1 mM Mo | ||

| KS36 | ΔnifHDK | 0.0067 | 0.0071 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.085 | 0.22 |

| R507 | ΔnifHDK moeA | —e | 0.0059 | — | — | — | — |

Enzyme activities were analyzed in crude extracts after photoheterotrophic growth on RCV medium containing 10 mM ammonium (xanthine dehydrogenase), 10 mM ammonium plus 0.1% nitrate (nitrate reductase) or 10 mM ammonium plus 30 mM DMSO (DMSO reductase). Mean values were calculated from at least six independent measurements.

Xanthine dehydrogenase activity is expressed as micromoles of NAD reduced per minute per milligram of protein.

Nitrate reductase activity is expressed as micromoles of nitrate reduced per minute per milligram of protein. Genes for nitrate reductase from R. sphaeroides were introduced into the corresponding R. capsulatus strains on a replicative plasmid (31).

DMSO reductase activity is expressed as micromoles of DMSO reduced per minute per milligram of protein.

—, below the limit of detection.

Purification of XDH from moeA mutant strains.

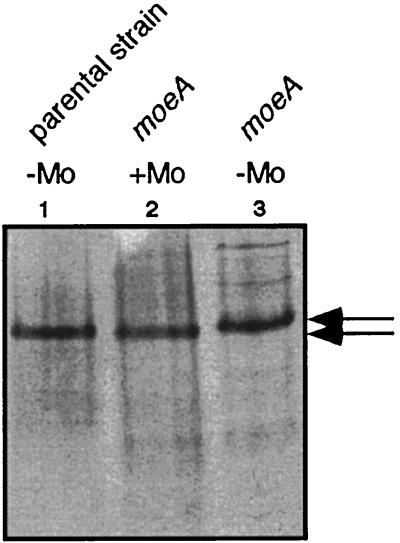

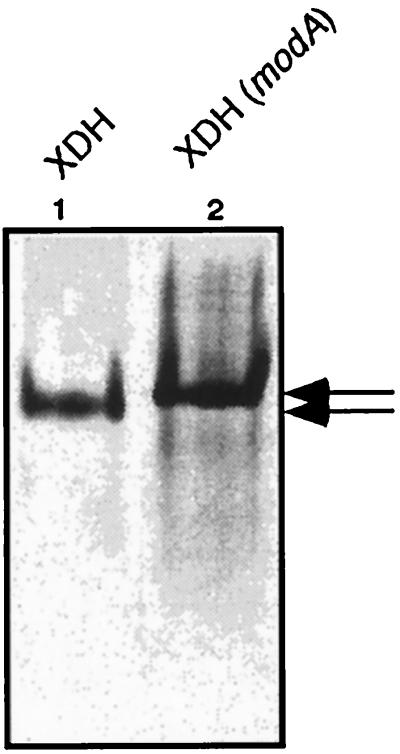

To determine the reason for inactive XDH in moeA mutants grown under low molybdate concentrations, XDH was purified from an R. capsulatus strain defective in moeA. In order to purify inactive XDH, a plasmid overexpressing xdhABC in R. capsulatus was constructed (see Materials and Methods). Plasmid pSL157 carries the structural genes for XDH (xdhAB) and xdhC required for XDH activity (21) under the control of the nifH promoter, which is inducible under nitrogen-limiting conditions. Plasmid pSL157 was introduced into the R. capsulatus moeA mutant strain R507 and into the corresponding parental strain KS36. The resulting strains were cultured under anaerobic, phototrophic conditions in RCV minimal medium containing serine as the nitrogen source to induce expression of plasmid-encoded XDH. Inactive as well as active XDH were enriched from cells grown either without the addition of molybdate or with 1 mM molybdate by preparative gel electrophoresis, as shown in Fig. 3 (Materials and Methods). Inactive XDH purified from R. capsulatus R507 grown without the addition of 1 mM molybdate has a reduced electrophoretic mobility compared to active XDH from R. capsulatus KS36 or R507 grown in the presence of 1 mM molybdate. As already described by Leimkühler and Klipp (21), inactive XDH isolated from an xdhC mutant strain, which was shown to be devoid of the MPT cofactor, also revealed a reduced electrophoretic mobility following polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Therefore, it could be assumed that inactive XDH from moeA mutants might also be devoid of the MPT cofactor (see below).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of active and inactive XDH from R. capsulatus by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Purified XDH was electrophoresed under nondenaturing conditions in 6% polyacrylamide gels and stained for protein with Coomassie brilliant blue. Arrows indicate different electrophoretic mobilities of active (lane 1 and 2) and inactive (lane 3) XDH. Lane 1, 2 μg of active XDH purified from R. capsulatus KS36; lane 2, 2 μg of active XDH purified from R. capsulatus R507 (moeA) grown in the presence of 1 mM molybdate; lane 3, 2 μg of inactive XDH purified from R. capsulatus R507 (moeA) grown without molybdate supplementation.

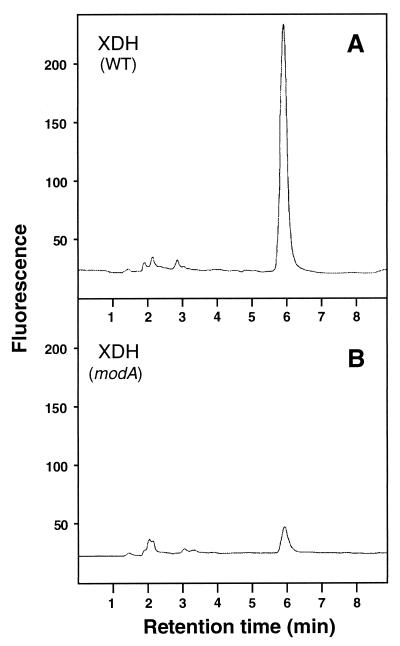

Fluorescence analysis of MPT derivatives isolated from active and inactive XDH purified from moeA mutant strains.

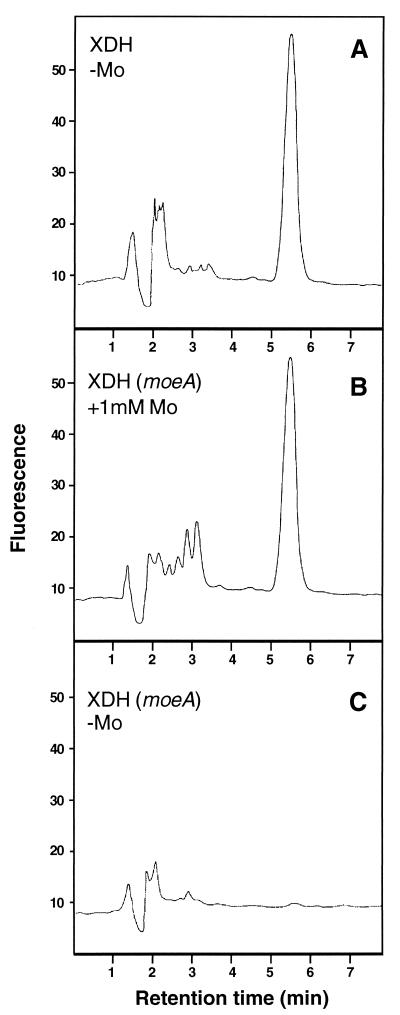

XDH in moeA mutants might be inactive, because (i) XDH lacks the MPT cofactor or (ii) enzyme-bound MPT lacks the molybdenum atom, which both might result in a reduced electrophoretic mobility of XDH. The first possibility indicates that only molybdenum-containing MPT (Mo-MPT) is incorporated into apo-XDH, and the second possibility suggests that apo-XDH would stay in an appropriate “open” conformation until the molybdenum atom is incorporated. To discriminate between these two possibilities, fluorescence derivatives of the MPT cofactor from active and inactive XDH isolated from moeA mutants were analyzed by the method described by Johnson et al. (12). Moco was released from active and inactive XDH by heat treatment followed by a treatment with acidic iodine, which converts MPT to its oxidized fluorescent degradation product, form A. By this method, Mo-MPT as well as MPT lacking molybdenum can be converted into form A. As described in Materials and Methods, dephospho-form A was purified on QAE-Sephadex columns and analyzed by HPLC. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, equal amounts of dephospho-form A were obtained from XDH isolated either from the parental strain KS36 or from the moeA mutant R507 grown in the presence of 1 mM molybdate. This result is consistent with the observation that XDH activity can be restored to approximate wild-type levels in moeA mutants grown in medium containing 1 mM molybdate (Table 2). In contrast, no form A was detected in XDH isolated from the moeA mutant strain R507 grown without molybdate supplementation (Fig. 4C). In accordance with the observed reduced electrophoretic mobility of inactive XDH from this strain, these data indicate that XDH in a moeA mutant does not contain MPT, suggesting that only molybdenum-bound MPT is incorporated into apo-XDH.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of fluorescent derivatives of the MPT cofactor of R. capsulatus XDH. HPLC elution profiles of dephospho-form A isolated from Mocos of XDH from different R. capsulatus strains. (A) R. capsulatus KS36 (parental strains); (B) R. capsulatus R507 (moeA), grown in the presence of 1 mM molybdate; and (C) R. capsulatus R507 (moeA), grown without molybdate supplementation. Mocos were converted into form A by oxidation with iodine at 95°C. Dephospho-form A was eluted from a QAE-Sephadex column with 10 mM acetic acid and analyzed by HPLC. Fluorescence was monitored with excitation at 370 nm and emission at 450 nm. Each protein was used for the analysis at a concentration of 0.8 μM.

Purification and cofactor analysis of XDH from an R. capsulatus modA mutant strain grown in the absence of molybdate.

To corroborate the hypothesis that only molybdenum-containing MPT is incorporated into XDH, a cofactor analysis of inactive XDH isolated from a strain starved for molybdenum was carried out. R. capsulatus strains containing mutations in the high-affinity molybdate transport system grown on molybdate-free medium were shown to contain an inactive XDH because of the lack of molybdenum in the cell and thus were unable to grow with xanthine as the sole nitrogen source (22a). To purify XDH from a strain containing a mutation in the modA gene (R438I), coding for the periplasmic binding protein of the R. capsulatus high-affinity molybdate transport system (46), the xdhABC-overexpressing plasmid pSL157 was introduced into the mutant strain R438I. The resulting strain was cultured under anaerobic, phototrophic conditions on molybdate-free medium (see Material and Methods) containing serine as the nitrogen source to induce the overexpression of xdhABC genes. XDH was purified by ion-exchange chromatography and preparative gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 5, inactive XDH isolated from the modA mutant also showed a reduced electrophoretic mobility in native polyacrylamide gels relative to that of active XDH purified from the R. capsulatus wild type.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of R. capsulatus XDH isolated from the wild type and a modA mutant strain by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Purified XDH was electrophoresed under nondenaturing conditions on 6% polyacrylamide gels and stained for protein with Coomassie brilliant blue. Arrows indicate different electrophoretic mobilities of active (lane 1) and inactive (lane 2) XDH. Lane 1, 3 μg of active XDH purified from R. capsulatus wild type; lane 2, 5 μg of inactive XDH purified from R. capsulatus R438I (modA), grown in the absence of molybdate.

To determine whether inactive XDH isolated from the modA mutant contained MPT lacking the molybdenum atom or, as demonstrated for XDH from moeA mutants, is totally devoid of the MPT cofactor, the enzyme was heat treated and the released Moco was converted to form A. The HPLC elution profiles of dephospho-form A obtained from XDH isolated from the modA mutant strain R438I, in comparison to those of equal amounts of active XDH from the R. capsulatus wild type (Fig. 6), revealed that only background levels of dephospho-form A were obtained from inactive XDH. The absence of MPT in XDH isolated from a strain starved for molybdenum clearly underlines the observation that only molybdenum-containing MPT is incorporated into the apo-enzyme.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of fluorescent derivatives of the MPT cofactor obtained from XDH of the R. capsulatus wild type and a modA mutant strain. HPLC elution profiles of dephospho-form A isolated from the MPT cofactor of XDH from the R. capsulatus wild type (A) (20) and R. capsulatus R438I (modA), grown in the absence of molybdate (B). The MPT cofactor was converted into form A and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Equal amounts of enzyme (0.25 μM) were used for each assay.

DISCUSSION

DNA sequence and mutational analyses indicated that the R. capsulatus moeA gene forms a monocistronic operon, and moeA is cotranscribed with neither moeB, as shown for E. coli, nor with any other gene involved in Moco biosynthesis. The R. capsulatus moeA gene product shows high similarities to MoeA of E. coli and other organisms. An internal domain was identified within MoeA, exhibiting similarities to E. coli MogA. This observation indicates a similar function of MoeA and MogA for the biosynthesis of the Moco. In addition, the corresponding proteins in eukaryotes were found to form a fusion protein consisting of a C- or N-terminal MogA domain and a C- or N-terminal MoeA domain (Fig. 2B). The separated MogA domain as well as the separated MoeA domain from the Cnx1 protein of A. thaliana were shown to bind MPT in vitro; however, the MogA domain binds MPT with a higher affinity than the MoeA domain does (38). This observation indicates that the internal MogA-like domain in MoeA might be responsible for MPT binding.

R. capsulatus MoeA seems to fulfill a similar role for the biosynthesis of the MPT cofactor as does MogA for the biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor in E. coli. The phenotype of corresponding mutants can be suppressed by high concentrations of molybdate. However, XDH activity in R. capsulatus moeA mutants was restored to almost wild-type levels by the addition of 1 mM molybdate. In contrast, molybdoenzyme activities in E. coli mogA mutants were only partially restored (10 to 13% of wild-type levels), even at molybdate concentrations of 10 mM (43). R. capsulatus MoeA as well as E. coli MoeA seems to be essential for the biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor, since MGD-containing enzymes were shown to be completely inactive in moeA mutants from both organisms. These data indicate that MoeA is involved in the synthesis of both MPT and MGD, but the pathways might branch at the step of molybdenum insertion. Since a mogA mutant is not yet available in R. capsulatus, it could only be speculated that R. capsulatus MogA might fulfill a role similar to that of E. coli MogA, and thus only the biosynthesis of MGD-containing enzymes might be influenced in an R. capsulatus mogA mutant whereas MPT-containing XDH might not be hurt.

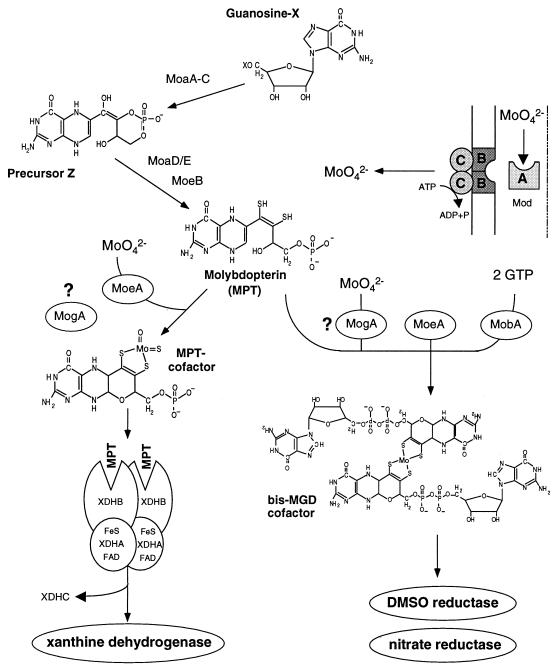

Analysis of fluorescent derivatives of the MPT cofactor in XDH revealed that inactive XDH isolated from moeA mutants is devoid of MPT, although enzyme activity could be restored to wild-type levels when these mutants were grown on high molybdate concentrations. Therefore, the spontaneous insertion of molybdenum into the cofactor, without the help of MoeA, seems to occur prior to cofactor insertion into XDH. Additionally, in XDH purified from a modA mutant grown in the absence of molybdate, only minor amounts of MPT were found. These data support the observation that molybdenum chelation to MPT, with or without the help of MoeA, precedes cofactor insertion into XDH. Taking into account all results available to date, the putative pathways of MPT and MGD cofactor biosynthesis in R. capsulatus are summarized in the model shown in Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

Model for Moco biosynthesis in R. capsulatus. Moco biosynthesis in R. capsulatus is predicted to proceed in a manner similar to that of Moco biosynthesis in E. coli. The molybdopterin molecule, still lacking molybdenum, is synthesized by the gene products of moaABC, moaDE, and moeB (30). For the biosynthesis of the MPT cofactor, MoeA is involved in molybdenum insertion into MPT. The role of MogA for MPT biosynthesis in R. capsulatus is yet unknown. XdhC is required to insert the MPT cofactor into XDH (21). In contrast, the biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor requires additional proteins. MogA is probably involved in molybdenum insertion, whereas MoeA is essential for MGD biosynthesis; the addition of the guanosine dinucleotide to MPT is catalyzed by MobA, the MGD synthase in R. capsulatus (22).

In comparison to Moco biosynthesis in E. coli (reviewed in reference 30), Moco biosynthesis in R. capsulatus probably proceeds in a similar manner, involving a series of reactions catalyzed by the moa, mod, and moe gene products (Fig. 7). At the stage when MPT is still lacking the molybdenum atom, biosynthesis of the MPT cofactor for XDH and the biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor for DMSO reductase and nitrate reductase seem to split in R. capsulatus. For the biosynthesis of the MPT cofactor, molybdenum is incorporated into MPT by the MoeA protein. However, MoeA is not essential for molybdenum insertion, because the phenotype of moeA mutants can be suppressed by high concentrations of molybdate. The role of the MogA protein in the biosynthesis of the MPT cofactor has not been examined in R. capsulatus, because a mogA mutant is not yet available. Only the molybdenum-containing MPT cofactor is incorporated into apo-XDH, which is already assembled as an α2β2 tetramer containing flavin adenine dinucleotide and 2[Fe-2S] clusters (21). Additionally, the XdhC protein is required for the insertion of the MPT cofactor into XDH (Fig. 7) (21).

In contrast to the MPT cofactor biosynthesis, the biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor requires additional proteins. Assuming a situation comparable to E. coli, a putative R. capsulatus MogA protein might be involved in molybdenum insertion into the MGD cofactor. The attachment of the guanosine moiety to MPT requires the MobA protein, an MPT guanine dinucleotide synthase, which has recently been identified in R. capsulatus (22). In contrast to the biosynthesis of the MPT cofactor for XDH, MoeA is absolutely essential for the biosynthesis of the MGD cofactor. Additionally, the analysis of fluorescent derivatives present in crude extracts of R. capsulatus moeA mutants revealed that these mutants are able to synthesize MPT but not MGD (22a). Therefore, it is possible that the nucleotide attachment to MPT occurs only after insertion of molybdenum into the cofactor. This hypothesis is consistent with the data obtained for CO dehydrogenase from Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava, for which the biosynthesis of MPT was independent of molybdenum, but molybdenum was strictly required for the conversion of MPT to molybdopterin cytosine dinucleotide (MCD) (7). Additionally, Hänzelmann and Meyer (7) reported that only in the presence of molybdenum was Mo-MCD inserted into CO dehydrogenase. Comparable data were obtained for MGD insertion into DMSO reductase and nitrate reductase in E. coli for which it was shown that both metal chelation and nucleotide addition preceded cofactor insertion (33, 34). Therefore, it seems to be a general mechanism for all molybdoenzymes that Moco insertion into the target enzyme occurs only after molybdenum chelation to the cofactor.

In conclusion, the current model of MPT and MGD cofactor biosynthesis outlined in Fig. 7 indicates that the pathways of these two kinds of molybdenum cofactors divide in R. capsulatus at the stage of molybdopterin. The insertion of molybdenum and in the case of MGD cofactors the addition of the guanine nucleotide occur later and separately. However, for MPT-containing enzymes as well as for enzymes harboring MGD cofactors, the insertion of the respective cofactor into the appropriate target enzyme seems to proceed only when Moco biosynthesis is completed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. V. Rajagopalan for helpful discussions and B. Masepohl for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was financially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck E, Ludwig G, Auerswald E A, Reiss B, Schaller H. Nucleotide sequence and exact localization of the neomycin phosphotransferase gene from transposon Tn5. Gene. 1982;19:327–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Bonnet, T., and A. McEwan. Personal communication.

- 3.del Campillo-Campbell A, Campbell A. Molybdenum cofactor requirement for biotin sulfoxide reduction in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:469–478. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.469-478.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng G, Tintrup H, Kirsch J, Nichol M C, Kuhse J, Betz H, Sanes J R. Dual requirement for gephyrin in glycine receptor clustering and molybdoenzyme activity. Science. 1998;282:1321–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrett R H, Nason A. Further purification and properties of Neurospora nitrate reductase. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:2870–2882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grunden A M, Shanmugam K T. Molybdate transport and regulation in bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:345–354. doi: 10.1007/s002030050508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hänzelmann P, Meyer O. Effect of molybdate and tungstate on the biosynthesis of CO dehydrogenase and the molybdopterin cytosine-dinucleotide-type of molybdenum cofactor in Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:755–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasona A, Ray R M, Shanmugam K T. Physiological and genetic analyses leading to identification of a biochemical role for the moeA (molybdate metabolism) gene product in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1466–1472. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1466-1472.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch P R, Beringer J E. A physical map of pPH1JI and pJB4JI. Plasmid. 1984;12:139–141. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hübner P, Willison J C, Vignais P M, Bickle T A. Expression of regulatory nif genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2993–2999. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2993-2999.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson M E, Rajagopalan K V. Involvement of chlA, E, M, and N loci in Escherichia coli molybdopterin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:117–125. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.117-125.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson J L, Hainline B E, Rajagopalan K V, Arison B H. The pterin component of the molybdenum cofactor. Structural characterization of two fluorescent derivatives. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5414–5422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson J L, Indermaur L W, Rajagopalan K V. Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: requirement of the chlB gene product for the formation of molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12140–12145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi M S, Rajagopalan K V. Specific incorporation of molybdopterin in xanthine dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;308:331–334. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi M S, Johnson J L, Rajagopalan K V. Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis in Escherichia coli mod and mog mutants. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4310–4312. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4310-4312.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamdar K P, Shelton M E, Finnerty V. The Drosophila molybdenum cofactor gene cinnamon is homologous to three Escherichia coli cofactor proteins and to the rat protein gephyrin. Genetics. 1994;137:791–801. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klipp W, Masepohl B, Pühler A. Identification and mapping of nitrogen fixation genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus: duplication of a nifA-nifB region. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:693–699. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.693-699.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutsche M, Leimkühler S, Angermüller S, Klipp W. Promoters controlling expression of the alternative nitrogenase and the molybdenum uptake system in Rhodobacter capsulatus are activated by NtrC, independent of ς54, and repressed by molybdenum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2010–2017. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2010-2017.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leimkühler S, Kern M, Solomon P S, McEwan A G, Schwarz G, Mendel R R, Klipp W. Xanthine dehydrogenase from the phototrophic purple bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus is more similar to its eukaryotic counterparts than to prokaryotic molybdenum enzymes. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:853–869. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leimkühler S, Klipp W. Role of XDHC in molybdenum cofactor insertion into xanthine dehydrogenase of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2745–2751. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2745-2751.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leimkühler S, Klipp W. The molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein MobA from Rhodobacter capsulatus is required for the activity of molybdenum enzymes containing MGD, but not for xanthine dehydrogenase harbouring the MPT cofactor. FEMS Lett. 1999;174:239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Leimkühler, S., and W. Klipp. Unpublished results.

- 23.Masepohl B, Klipp W, Pühler A. Genetic characterization and sequence analysis of the duplicated nifA/nifB gene region of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00322441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McEwan A G, Wetzstein H G, Ferguson S J, Jackson J B. Periplasmic location of the terminal reductase in trimethylamine N-oxide and dimethylsulphoxide respiration in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;806:410–417. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawlowski K, Klosse U, de Bruijn F J. Characterization of a novel Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 two-component regulatory system, NtrY/NtrX, involved in nitrogen fixation and metabolism. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;231:124–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00293830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitterle D M, Johnson J L, Rajagopalan K V. In vitro synthesis of molybdopterin from precursor Z using purified converting factor. Role of protein-bound sulfur in formation of the dithiolene. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13506–13509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollock D, Bauer C E, Scolnik P A. Transcription of the Rhodobacter capsulatus nifHDK operon is modulated by the nitrogen source. Construction of plasmid expression vectors based on the nifHDK promoter. Gene. 1988;65:269–275. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajagopalan K V, Johnson J L. The pterin molybdenum cofactors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10199–10202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajagopalan K V. Biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactor. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtis III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 674–679. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reyes F, Roldan M D, Klipp W, Castillo F, Moreno-Vivian C. Isolation of periplasmic nitrate reductase genes from Rhodobacter sphaeroides DSM 158: structural and functional differences among prokaryotic nitrate reductases. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1307–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rivers S L, McNairn E, Blasco F, Giordano G, Boxer D H. Molecular genetic analysis of the moa operon of Escherichia coli K-12 required for molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1071–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothery R A, Simala Grant J L, Johnson J L, Rajagopalan K V, Weiner J H. Association of molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide with Escherichia coli dimethyl sulfoxide reductase: effect of tungstate and a mob mutation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2057–2063. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2057-2063.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothery R A, Magalon A, Giordano G, Guigliarelli B, Blasco F, Weiner J H. The molybdenum cofactor of Escherichia coli nitrate reductase A (NarGHI): effect of a mobAB mutation and interactions with [Fe-S] clusters. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7462–7469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider K, Müller A, Johannes K U, Diemann E, Kottmann J. Selective removal of molybdenum traces from growth media of N2-fixing bacteria. Anal Biochem. 1991;193:292–298. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90024-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider F, Löwe J, Huber R, Schindelin H, Kisker C, Knäblein J. Crystal structure of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus at 1.88 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1996;263:53–69. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarz G, Boxer D H, Mendel R R. Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. The plant protein Cnx1 binds molybdopterin with high affinity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26811–26814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. BioTechnology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith P K, Krohn R I, Hermanson G T, Mallia A K, Gartner F H, Provenzano M D, Fujimoto E K, Goeke N M, Olson B J, Klenk D C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staden R. The current status and portability of our sequence handling software. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:217–232. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stallmeyer B, Nerlich A, Schiemann J, Brinkmann H, Mendel R R. Molybdenum co-factor biosynthesis: the Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA cnx1 encodes a multifunctional two-domain protein homologous to a mammalian neuroprotein, the insect protein Cinnamon and three Escherichia coli proteins. Plant J. 1995;8:751–762. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08050751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart V, MacGregor C H. Nitrate reductase in Escherichia coli K-12: involvement of chlC, chlE, and chlG loci. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:788–799. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.788-799.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang G, Angermüller S, Klipp W. Characterization of Rhodobacter capsulatus genes encoding a molybdenum transport system and putative molybdenum-pterin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3031–3042. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3031-3042.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zimmermann J, Voss H, Schwager C, Stegemann J, Erfle H, Stucky K, Kristensen T, Ansorge W. A simplified protocol for fast plasmid DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]