INTRODUCTION

The Veteran’s Choice Program (VCP), established by the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act (VACAA) in 2014, guaranteed veterans temporary access to community care when appointments were not available within 30 days or for veterans living >40 miles from the nearest Veteran’s Health Administration (VA) hospital.1 The VA’s Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act in 2018 relaxed these criteria and instated Community Care (CC) as a permanent fixture to the VA model, known as the VA Community Care Program.2

Referring care to the community is time- and personnel-consuming medical care requiring significant effort and coordination from the VA.3,4 Documentation and test results take time to receive and upload into the VA electronic medical records (EMR). This raises the question if CC truly expedites the process for patients or rather delays overall veteran care.4 In this retrospective cohort study, we examined the timeliness of pulmonary function testing (PFT) and time to test acknowledgement by ordering provider.

METHODS

This study identified PFTs of unique patients referred through the VCP at a single urban veteran’s hospital between 2014 and 2016. Only patients with completed PFTs were included. The process of obtaining CC for PFTs occurs in this order: (1) VA provider places the order, (2) CC office reviews, places a CC consult, and schedules the test, (3) CC PFT is completed, and (4) results and interpretation are uploaded to EMR. We identified the dates of each of these steps. Indication for CC referral (i.e., wait time and distance) was captured. The time intervals (days) for each step and cumulative time were presented as median and interquartile ranges (IQR).

Provider acknowledgement was defined as any mention of the PFT within a clinic note, test results/personal communication, or telephone encounter within 1 year of PFT upload.

RESULTS

There were 270 PFTs processed through CC referral during the specified time. Of those, 252 were completed and included in the analysis.

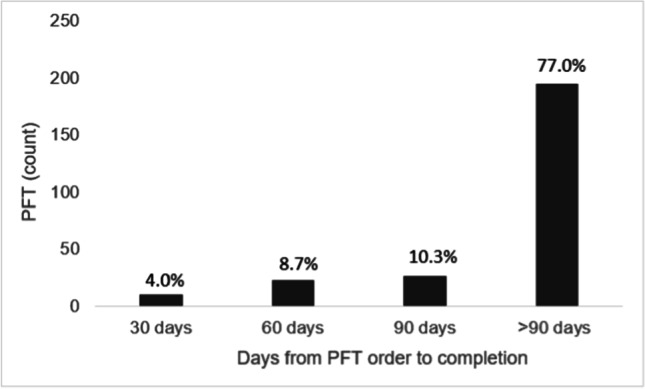

Table 1 shows the interval and cumulative days for each step stratified by indication. Median days to CC consult placed were shorter if the indication was distance versus wait times, 37 versus 50 days respectively. However, the median days for PFT completion were similar for both groups. Figure 1 shows the number of PFTs completed in 30-day intervals after providers placed the order. Only 10 (4.0%) PFTs had a completion time of ≤30 days, and of those, 3 had an indication due to distance. A total of 194 (77.0%) PFTs had a completion time of >90 days. Providers acknowledged 49.2% (124/252) of the PFTs within 1 year after completion (N = 117 (46.4%) in clinic notes, N = 7 (2.8%) in test results/personal communication or telephone encounter). No interpretation or upload was available for 24 (9.5%) PFTs.

Table 1.

Community Care Referral Process and Days for Each Step

| Step | Total referred due to wait time (N = 206) | Total referred due to distance (N = 46) | Total referred (N = 252) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days between the steps, median (IQR) | Cumulative days, median (IQR) | Days between the steps, median (IQR) | Cumulative days, median (IQR) | Days between the steps, median (IQR) | Cumulative days, median (IQR) | |

| 1) Order placed by provider | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2) Community care consult placed | 50 (20–72) | 50 (20–72) | 37 (14–60) | 37 (14–60) | 46 (18–70) | 46 (18–70) |

| 3) PFT completion | 64 (43–82) | 119 (97–137) | 65 (48–76) | 105 (82–121) | 64 (44–80) | 115 (92–135) |

| 4) Result uploaded to VA EMR | 21 (9–40) | 146 (114–169) | 16 (7–55) | 129 (98–179) | 21 (9–41) | 142 (111–171) |

Figure 1.

Number of pulmonary function tests (PFTs) completed within 30-day intervals after order placed by providers.

DISCUSSION

Our findings show that PFTs performed through the VA Community Care Program are associated with delays beyond the 30-day benchmark, with 77% beyond 90 days. The delay in PFTs through CC parallels the delay in colonoscopies as previously reported by Dueker and Khalid.5 In addition, our findings support the qualitative complaints made by VA PCPs reported by Nevedal et al., regarding administrative burdens related to CC, causing delays, care fragmentation, and poor care coordination.3 In our study, 9.5% of PFTs completed in the community did not have the results or interpretation uploaded to be available to the VA provider. Lack of provider acknowledgement may be due to lack of provider awareness of available test results and timing of a clinic visit or clinical relevance of PFT findings.

If the wait times to obtain a PFT within the VA are comparable to 90 days, then waiting for the test completion at the VA would be more efficient as the time to interpretation and upload would be faster. The CC process has more layers that can cause delays, such as multiple coordinated steps required to obtain the service and to upload the test results. A limitation of our study is the generalizability beyond an urban, veteran population. Future VA policies should aim to refine the CC referrals for PFTs and consider the urgency of the test and the benefits of receiving care within the VA if the wait times are equivocal.

Acknowledgements

This work was performed at the Jesse Brown Veterans Health Administration Hospital.

Author MJ is a US government employee and this manuscript was made in that capacity; thus, assignment applies only to the extent allowable by US law.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Trinh T. Pham and Esther Pacheco are co-first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014. H Rept. 113-564. Public Law No: 113–146. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/3230. Accessed Dec 2022.

- 2.Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Kerr EA. Completing the MISSION: a blueprint for helping veterans make the most of new choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1567-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Nevedal AL, et al. A qualitative study of primary care providers’ experiences with the Veterans Choice Program. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):598-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gaglioti A, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1236-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dueker JM, Khalid A. Performance of the Veterans Choice Program for improving access to colonoscopy at a tertiary VA facility. Fed Pract. 2020;37(5):224-228. [PMC free article] [PubMed]