Abstract

Objective

To ascertain whether extra-peritoneal approach is superior to conventional trans-peritoneal approach of cesarean section in terms of fetus delivery time, intra-operative and postoperative outcomes, including return of bowel activity and pain.

Study design

An open-label randomized controlled trial conducted over one year and six months at a tertiary care center in India. As per sample size calculation, 68 women enrolled in the study; 34 underwent extra-peritoneal, and another 34 underwent trans-peritoneal cesarean section after randomization. Statistical analysis was done with independent sample 't' test, chi-squared test, and fisher's exact test.

Results

Baseline characteristics were comparable in both groups. Fetus delivery time was significantly higher in extra-peritoneal than trans-peritoneal cesarean section (14.26 ± 1.26 vs. 9.38 ± 1.83 min; p = <0.001). Total operation time was also higher in extra-peritoneal than trans-peritoneal approach (63.24 ± 12.74 vs. 57.41 ± 8.62 min; p = 0.027). Whereas average blood loss was comparable in both groups (733.82 ± 219.06 vs. 694.12 ± 351.57 ml; p = 0.063). Postoperatively, return of bowel activity was significantly earlier in extra-peritoneal than trans-peritoneal approach (4.59 ± 0.56 vs. 8.65 ± 1.23 h; p = <0.001). Mean time taken for passage of flatus was also significantly less in extra-peritoneal cesarean section (8.56 ± 0.99 vs. 12.76 ± 2.05 h; p = <0.001). Pain score at 6, 12, and 18 h was significantly lower in extra-peritoneal approach. No patient in extra-peritoneal approach had nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension. Whereas 11.8 % of patients had nausea, 5.9 % had constipation, and 14.7 % had abdominal distension in trans-peritoneal cesarean section. Requirement of injectable antibiotics and analgesics, and hospital stay was less with extra-peritoneal approach.

Conclusion

Extra-peritoneal cesarean section is associated with better postoperative outcomes with respect to return of bowel functions, pain, and requirement of injectable analgesics and antibiotics than the routine trans-peritoneal cesarean section. However, the significantly higher fetus delivery time questions its feasibility in patients with acute fetal distress. Additionally, it is technically difficult and has a longer learning curve.

Keywords: Extra-peritoneal, Trans-peritoneal, Cesarean section, Fetus delivery time, Bowel activity

Introduction

Cesarean section (CS) is the most common obstetric operation. It comprises of delivery of a fetus through an abdominal and uterine incision. The mortality of CS has been reduced to a significant extent. Still, it’s morbidity in terms of infection, pain, and intra-peritoneal adhesions is yet to be conquered, which is mainly due to contamination of peritoneal cavity. In conventional trans-peritoneal cesarean section (TPCS), peritoneal cavity is opened deliberately which allows entry of organisms, bowel handling, and physical trauma of desiccation. Additionally, amniotic fluid contents might cause chemical and immunological trauma to peritoneum.

To reduce the severe morbidity of TPCS in pre-antibiotic era, extra-peritoneal approach of CS was devised. The technique of extra-peritoneal cesarean section (EPCS) was proposed in 1824 by Philip Physick by separating the peritoneum from the bladder's dome to expose lower uterine segment (LUS) [1]. Fritz Frank performed first successful EPCS in 1907 [1]. However, this approach was declined after 1950 s once the antibiotic era started. Studies proved that if antibiotics are used, there is no benefit of EPCS on infectious morbidity [2], [3], [4]. Moreover, it has never been popular among obstetricians because of delay in delivery of fetus, safety, feasibility of surgery, and high likelihood of unintentional perforation of peritoneum [1], [5].

However, some studies suggest that extra-peritoneal approach is better than conventional trans-peritoneal approach regarding intra-operative pain, operation time, postoperative surgical site pain, shoulder pain, analgesic requirement, time until flatus passage and oral tolerability as peritoneal cavity is not opened, no bowel handling and minimal chance of entry of organisms; hence intra-peritoneal infections are avoided [6]. Additionally, there is no chance of losing a surgical mop in the peritoneal cavity, and long-term sequelae of intra-peritoneal adhesion is negligible.

We aim to ascertain whether extra-peritoneal approach is superior to conventional trans-peritoneal approach of CS in terms of intra-operative and postoperative outcomes in the current antibiotic era.

Materials and methods

An open-label randomized controlled trial was conducted over one year and six months (March 2021 - September 2022) at a tertiary care center in India after obtaining institutional ethical clearance (AIIMS/IEC/21/108).

Patients planned for CS (both emergency and elective) were included in the study with no restrictions on previous abdominal surgery, fetal weight, and gestational age. Hemodynamically unstable mother, acute fetal distress, history of >2 CS, abnormal placentation, abruptio placenta, cord prolapse, coagulation defect, mass in LUS, or requiring general anesthesia were excluded from study. Written informed consent was taken from each patient after explaining study protocol. Thereafter, patients were taken up for assigned approach of CS based on computer-generated random numbers. Randomization was done by one of the data entry operators from department who was not involved in the study.

The primary outcome was fetus delivery time, measured from skin incision to delivery of fetus in minutes using a chronometer in operating room. Secondary outcome measures were total operation time (time of skin incision to skin closure), blood loss (by using calibrated suction cannister and weighing blood-soaked mops), postoperative pain at 6, 12, and 18-hours post-surgery (using visual analogue scale), return of bowel function including time of appearance of bowel sounds on auscultation which was done every hourly starting from 4 h post-surgery, and time of passage of flatus for which the patient was asked to note time, requirement of injectable antibiotics and analgesics, APGAR score at 1 and 5 min, hemoglobin (Hb) difference (calculated by subtracting postoperative Hb value from preoperative Hb value), any intra-operative or postoperative complication.

Two obstetricians (KK and RM) performed all surgeries under spinal anesthesia. Antibiotic prophylaxis with Inj ceftriaxone 1 gm was administered intravenously 30 min prior in both approaches.

Extra-peritoneal cesarean section technique

For EPCS, a paravesical approach was followed as described by Cacciarelli [7]. Pfannenstiel incision was made over skin under asepsis. Subcutaneous tissue followed by rectus sheath was divided by sharp dissection. The rectus muscles were approached laterally from the right side and transversalis fascia was separated until the right inferior epigastric vessels are visualized. Inferior epigastric vessels were an important landmark and ligated prophylactically in some cases (Fig. 1a). Transversalis fascia was then pierced bluntly and opened widely medial to inferior epigastric vessels, to expose the LUS covered with urinary bladder. The median umbilical ligament, which denotes lateral border of the bladder, was identified by sweeping aside the peritoneum (Fig. 1b). This avascular space was further dissected bluntly (Fig. 1c), followed by bladder was pushed downwards and medially to expose cervico-vesical fascia, and LUS was assessed. At this point, the tongue of the peritoneum of vesico-uterine fold becomes visible superiorly. The bladder was further pushed medially (to the left) and inferiorly until the space was large enough to deliver the fetus. Incision was made over LUS, and the fetus was delivered. Fig. 1d shows the uterine incision site with intact peritoneum. Uterus was then closed in two layers leaving the decidua using vicryl 1–0. Abdomen was closed in layers after ensuring adequate hemostasis.

Fig. 1.

a: Inferior epigastric artery indicated by an arrow; 1b: Right median umbilical ligament marked as 1; 1c: Area ‘A′ showing the avascular space where dissection was carried out; 1d: Uterine incision after fetus delivery (black arrow), bladder retracted medially (blue arrow), intact peritoneum (black dotted line) i.e., peritoneal cavity not breached.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation was based on a study by Yapca et al. [8] using G*POWER software version 3.1.9.7. To achieve a power of 80 % with an alpha error of 5 %, an estimated sample size of 34 per group was established. Data were coded in an MS Excel spreadsheet. Data analysis was performed with SPSS v21 (IBM Corp) [9]. When comparing two groups, independent sample 't' test was used for continuously distributed data, and chi-squared test was employed for categorical data. Fisher's exact test was utilized since it was discovered that predicted frequency in contingency tables was 25 % of cells. Statistical significance was maintained at p < 0.05.

Results

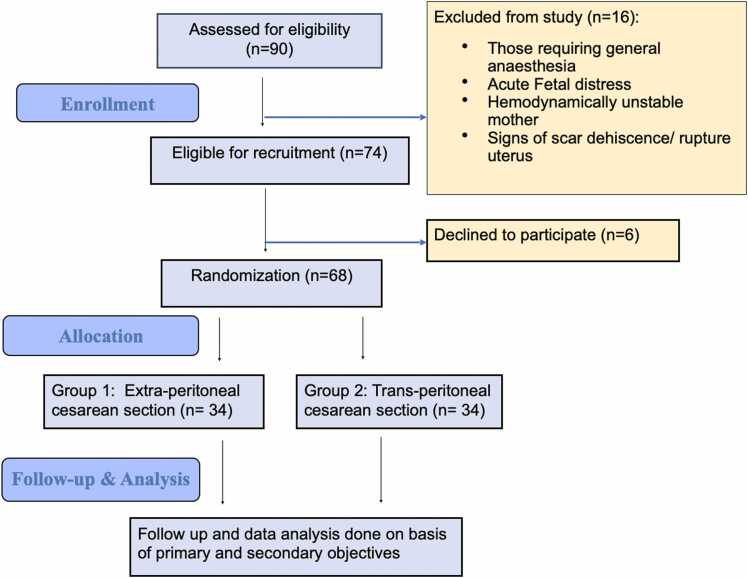

During study period, a total of 90 women were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 16 women did not meet the eligibility criteria, six women declined to participate, and 68 women were enrolled in the study and randomized to EPCS group (n = 34) who underwent extra-peritoneal cesarean section, and TPCS group (n = 34) who underwent trans-peritoneal cesarean section (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the study.

The baseline characteristics such as age, socioeconomic status, parity, gestational age, previous history of CS, and pregnancy-associated high-risk factors (pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes) were similar in both groups (Table 1) except a significantly high body mass index in EPCS group which could be a matter of chance as the groups were randomized.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of both the groups.

| Parameters | EPCS group (n = 34) | TPCS group (n = 34) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 26.03 ± 3.65 | 27.71 ± 3.69 | 0.0561 |

| Socioeconomic Status | 1.0003 | ||

| Middle | 8 (23.5 %) | 9 (26.5 %) | |

| Upper Middle | 4 (11.8 %) | 3 (8.8 %) | |

| Lower Middle | 8 (23.5 %) | 7 (20.6 %) | |

| Lower | 14 (41.2 %) | 15 (44.1 %) | |

| BMI (Kg/m²) *** | 22.85 ± 1.83 | 21.29 ± 2.29 | < 0.0011 |

| < 18.5 Kg/m2 | 0 (0.0 %) | 2 (5.9 %) | |

| 18.5–22.9 Kg/m2 | 16 (47.1 %) | 27 (79.4 %) | |

| 23.0–24.9 Kg/m2 | 14 (41.2 %) | 4 (11.8 %) | |

| 25.0–29.9 Kg/m2 | 4 (11.8 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | |

| 30.0–34.9 Kg/m2 | 0 (0.0 %) | 1 (2.9 %) | |

| Parity | 0.4512 | ||

| Primigravida | 11 (32.4 %) | 14 (41.2 %) | |

| Multigravida | 23 (67.6 %) | 20 (58.8 %) | |

| POG (weeks) | 36.35 ± 2.78 | 37.58 ± 1.80 | 0.1151 |

| Previous LSCS | 15 (44.1 %) | 16 (47.1 %) | 0.8082 |

| Pregnancy associated high risk factors | 15 (44.1 %) | 14 (41.2 %) | 0.8062 |

***Significant at p < 0.05, 1: Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U Test, 2: Chi-Squared Test, 3: Fisher's Exact Test, EPCS = Extra peritoneal cesarean section, BMI = Body mass index, LSCS = Lower segment cesarean section, POG = Period of gestation, TPCS = Trans peritoneal cesarean section.

Intra-operative outcomes

Table 2 describes intra-operative measures including baby details of both groups. The mean fetus delivery time was significantly higher in EPCS than TPCS (p = <0.001). The challenging learning curve of extra-peritoneal approach might be the reason behind more fetus delivery time in first few cesareans, which decreased subsequently. This attributed to higher total operation time in EPCS (range 49–120 min) than TPCS (range 45–90 min) (p = 0.027). However, the closure was faster in extra-peitoneal approach as peritoneal cavity was not opened, additional steps such as suctioning of cul-de-sac or cleaning of paracolic gutters was not needed. The blood loss was comparable in both approaches (p = 0.063).

Table 2.

Intra-operative outcome measures in both groups.

| Parameters | EPCS group (n = 34) | TPCS group (n = 34) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetus delivery time (minutes)*** | 14.26 ± 1.26 | 9.38 ± 1.83 | < 0.0011 |

| Total operation time (minutes)*** | 63.24 ± 12.74 | 57.41 ± 8.62 | 0.0271 |

| Blood loss (ml) | 694.12 ± 351.57 | 733.82 ± 219.06 | 0.0631 |

| Intraoperative complications | 2 (5.9 %) | 1 (2.9 %) | 1.0003 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 1 (2.9 %) | 2 (5.9 %) | 1.0003 |

| Baby details | |||

| Birth weight (gm)*** | 2416.06 ± 495.95 | 2751.74 ± 665.19 | 0.0051 |

| < 1500 gm | 2 (5.9 %) | 2 (5.9 %) | |

| 1500–2500 gm | 14 (41.2 %) | 8 (23.5 %) | |

| > 2500 gm | 18 (52.9 %) | 24 (70.6 %) | |

| APGAR score (1 min) | 7.65 ± 0.77 | 7.38 ± 1.52 | 0.6041 |

| APGAR score (5 min) | 8.88 ± 0.33 | 8.76 ± 0.65 | 0.6391 |

| NICU Admission | 8 (23.5 %) | 7 (20.6 %) | 0.7702 |

***Significant at p < 0.05, 1: Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U Test, 2: Chi-Squared Test, 3: Fisher's Exact Test.

In both groups, one patient was incidentally diagnosed to have adherent placenta after delivery of fetus. Both of them were managed by cesarean hysterectomy and spinal anesthesia was converted to general anesthesia. The peritoneum was deliberately opened in women undergoing EPCS. Two women (5.9 %) in EPCS and one (2.9 %) in TPCS group had bladder injury while pushing bladder to expose LUS (p = 1.000). All were diagnosed and managed intraoperatively. All three injuries were seen in patients who had dense bladder adhesions.

Postoperative outcome measures

Table 3 shows the postoperative outcomes in both groups. The return of bowel functions in terms of appearance of bowel sounds and passage of flatus was significantly earlier in EPCS than TPCS group (p = <0.001). No patient in EPCS group had nausea, vomiting, or abdominal distension. Such decreased postoperative morbidity in EPCS is because of no peritoneal opening and no bowel handling. The mean Hb difference was significantly higher in TPCS than EPCS group (p = 0.001) might be because of more blood loss in TPCS. Requirement for blood transfusion was also higher in TPCS group (p = 0.476). Women in EPCS group received injectable antibiotics for significantly less duration (p = <0.001). Pain scores were significantly less in EPCS than TPCS at 6, 12, & 18 h (p = <0.001, 0.004, & 0.027 respectively). Hence, requirement for injectable analgesics was significantly less in EPCS group (p = <0.001).

Table 3.

Postoperative outcomes in both groups.

| Parameters | EPCS group (n = 34) | TPCS group (n = 34) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time taken for appearance of bowel sounds (h)*** | 4.59 ± 0.56 | 8.65 ± 1.23 | < 0.0011 |

| Time taken for passage of flatus (h)*** | 8.56 ± 0.99 | 12.76 ± 2.05 | < 0.0011 |

| Change in Hemoglobin (g/dl) *** | 1.04 ± 0.51 | 1.40 ± 0.40 | 0.0011 |

| Blood Transfusion | 3 (8.8 %) | 6 (17.6 %) | 0.4763 |

| VAS score (6 h) *** | 6.18 ± 0.67 | 7.03 ± 0.83 | < 0.0011 |

| VAS score (12 h) *** | 4.18 ± 0.83 | 4.76 ± 0.89 | 0.0041 |

| VAS score (18 h) *** | 2.38 ± 0.95 | 3.00 ± 1.07 | 0.0271 |

| Duration of inj analgesics (h)*** | 16.24 ± 6.69 | 21.00 ± 5.17 | < 0.0011 |

| Duration of inj antibiotics (h)*** | 33.53 ± 19.04 | 47.65 ± 18.33 | < 0.0011 |

| Post-operative complications - | |||

| Nausea/Vomiting |

0 (0.0 %) |

4 (11.8 %) |

0.1143 |

| Constipation |

0 (0.0 %) |

2 (5.9 %) |

0.4933 |

| Distension |

0 (0.0 %) |

5 (14.7 %) |

0.0533 |

| Fever | 1 (2.9 %) | 1 (2.9 %) | 1.0003 |

| Catheterization beyond 24 h | 2 (5.9 %) | 1 (2.9 %) | 1.0003 |

| Duration Of hospital stay (days)*** | 4.15 ± 0.89 | 4.82 ± 1.34 | 0.0271 |

***Significant at p < 0.05, 1: Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U Test, 2: Chi-Squared Test, 3: Fisher's Exact Test, VAS = Visual analogue scale.

Discussion

Theoretically, extra-peritnoeal approach seems to be superior than trans-peritoneal approach. Still, it has lost popularity among obstetricians once the antibiotic era started. The literature is mainly confined to pre-antibiotic period [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [10]. Nevertheless, a few comparative studies have been reported in the last decade [8], [11], [12], [13], [14].

We noted higher mean fetus delivery time in EPCS (14.26 ± 1.26 min) than TPCS (9.38 ± 1.83 min) (p = <0.001) and higher total operation time in EPCS (63.24 ± 12.74 min) than TPCS (57.41 ± 8.62 min) (p = 0.027). Similarly, Bebincy et al. [11] documented more fetus delivery time in EPCS than TPCS (average 4:57 vs 2:05 min). Tappauf et al. [12] also reported more fetus delivery time in EPCS than TPCS [4 (3.25–6.00) vs. 3 (3.00–4.50) minutes; p = 0.053]. On the contrary, Yapca et al. [8] noted similar fetus delivery time in EPCS and TPCS (2.1–7.3 & 1.9–8.2 min) (p = 0.065), but significantly higher operation time in TPCS than EPCS (19.9–75.8 vs. 17.2–41.3 min; p = 0.001). Chao et al. [13] also documented significantly higher operation time with TPCS than EPCS (p = < 0.05) in a retrospective study. Likewise, Tappauf et al. [12] reported significantly higher operative time in TPCS than EPCS (34.7+10.5 vs. 28.9+3.9 min; p = 0.012).

In our study, the average blood loss was higher in TPCS than EPCS (733.82 ± 219.06 vs. 694.12 ± 351.57 ml; p = 0.063). Vaswani BP et al. [14] also noted more blood loss in TPCS group (490 ml) than EPCS group (476 ml). Intraoperative complications were comparable in both groups in present study. Similarly, Yapca, Bebincy, and Tappauf et al. did not report any major complication in either group [8], [11], [12]. The complication rate is much lower than in studies published in 19th century [2], [10]. In accordance with our research, the APGAR score at 1 and 5 min was comparable in both groups in previous comparative studies [8], [11], [12].

The return of bowel activity was significantly earlier in EPCS than TPCS (4.59 ± 0.56 vs. 8.65 ± 1.23 h; p = <0.001). Similarly, Vaswani et al. [14] noted earlier return of bowel sounds in EPCS than TPCS (5.46 vs. 11.33 h). In present study, the mean time taken for passage of flatus was significantly less in EPCS than TPCS (8.56 ± 0.99 vs. 12.76 ± 2.05 h; p = <0.001). Likewise, Bebincy et al. [11] reported less time for passage of flatus in EPCS than TPCS group (4.687 vs. 16.487 h). Yapca et al. [8] also documented significantly less time for passage of flatus in EPCS than TPCS group (8 ± 4 vs. 13 ± 4 h; p = 0.001).

Pain score at 6, 12, and 18 h was significantly lower in EPCS than TPCS group in our study. Likewise, Tappauf et al. [12] reported lower median peak pain scores on postoperative day 1 for EPCS than TPCS (4.00 vs. 5.00; p = 0.031). Analgesic requirements, intraoperative nausea, and postoperative shoulder pain were significantly less after EPCS. Bebincy et al. [11] also noted less postoperative pain scores in EPCS than TPCS (4.28 vs. 7.06). Similarly, Vaswani et al. [14] documented less postoperative pain in EPCS than TPCS (4.13 vs. 6.86).

In our study, none had nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension in EPCS group. Whereas 11.8 % of patients had nausea, 5.9 % had constipation, and 14.7 % had abdominal distension in TPCS group postoperatively. Tappauf et al. [12] showed similar results to our study; only 3/27 patients had nausea in TPCS group (p = <0.001). In a study by Yapca et al. [8], 5/105 patients in EPCS had nausea, while 8/105 had nausea and 2/105 had vomiting in TPCS group. Sharma et al. [15] documented abdominal distension in 3.44 % with EPCS. Women who underwent TPCS required more days in hospital than EPCS in our study and studies by Yapca and Tappauf et al. [8], [12].

The above data shows that although EPCS is technically challenging and has a longer learning curve but, it has better postoperative outcomes with regards to early return of bowel function, postoperative pain, less requirement of injectable antibiotics and analgesics, and shorter duration of hospital stay.

There are certain advantages and disadvantages of EPCS, as described below.

Advantages of EPCS over TPCS

-

•

No bowel handling, hence early return of bowel function.

-

•

Reduces risk of postoperative ileus.

-

•

Minimal chance of entry of organisms, so no intra-peritoneal infections.

-

•

No chance of losing a surgical mop in peritoneal cavity.

-

•

Long-term sequelae of intra-peritoneal adhesions are avoided.

-

•

Less postoperative pain, thereby decreasing injectable analgesic requirement.

-

•

Better oral tolerability and early ambulation.

-

•

Shorter hospital stay.

-

•

Preferred in immuno-compromised patients such as HIV/AIDS patients.

-

•

Low risk of postoperative hernia.

-

•

Economic advantage: limited use of intravenous fluids, analgesics, hospital toiletries, sutures, and beddings.

Disadvantages of EPCS over TPCS

-

•

EPCS is difficult and needs a longer learning curve.

-

•

Fetus delivery time is longer, and shouldn’t be done in acute fetal distress and under general anesthesia as risk of fetal hypoxia will be greater.

-

•

Risk of injury to inferior epigastric vessels during dissection.

-

•

If extended, injury to medial umbilical ligament can cause hemorrhage from anterior division of internal iliac artery.

-

•

Risk of injury to urinary bladder.

-

•

Assessment of uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and abdominal cavity cannot be carried out.

-

•

Simultaneous tubal ligation or resection of myomas cannot be done.

-

•

Possibility of opening peritoneum during delivery is still there, which would negate the goal of procedure.

Single centric study, small sample size, and shorter follow-up period are some limitations of our study. However, the prospective design, statistically determined sample size, and randomization contribute to reproducibility of our findings. Further multi-centric studies with large sample size and longer follow-up period to assess adhesion-related morbidity are required to produce more robust results.

Conclusion

Extra-peritoneal cesarean section is associated with better postoperative outcomes in terms of return of bowel functions, pain, and requirement of injectable analgesics and antibiotics than the routine trans-peritoneal cesarean section. However, the significantly higher fetus delivery time questions its feasibility in patients with acute fetal distress. Additionally, it is technically difficult and has a longer learning curve.

No funding required

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgement

Nil.

Disclosure statement

None.

All authors declared no conflict of interest

The study was approved from Institutional ethical committee (AIIMS/IEC/21/108).

References

- 1.Hibbard L.T. Extraperitoneal cesarean section. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1985;28(4):711–721. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198528040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atherton H.E., Williamson P.J. A clinical comparison of extraperitoneal cesarean section and low cervical cesarean section for the potentially or frankly infected parturient. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;68(4):1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)38404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace R.L., Eglinton G.S., Yonekura M.L., Wallace T.M. Extraperitoneal cesarean section: a surgical form of infection prophylaxis? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(2):172–177. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(84)80171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haesslein H.C., Goodlin R.C. Extraperitoneal cesarean section revisited. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55(2):181–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkins R.P. Role of extraperitoneal cesarean section. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980;23(2):583–599. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198006000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokgokong E.T., Crichton D. Extraperitoneal lower segment caesarean section for infected cases. A reappraisal. S. Afr Med J Suid-Afr Tydskr Vir Geneeskd. 1974;48(18):788–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacciarelli R.A. Extraperitoneal cesarean section; a new paravesical approach. Am J Surg. 1949;78(3):371–373. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(49)90356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yapca O.E., Topdagi Y.E., Al R.A. Fetus delivery time in extraperitoneal versus transperitoneal cesarean section: a randomized trial. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(4) doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1499718. 657-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IBM Corp. Released 2021 IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- 10.Norton J.F. A paravesical extraperitoneal cesarean section technique; with an analysis of 160 paravesical extraperitoneal cesarean sections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;51:519–526. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(15)30167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bebincy D.S., Chitra J. Extraperitoneal versus transperitoneal cesarean section in surgical morbidity in a tertiary care centre. Int J Reprod Contracept. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6(8):3397–3399. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tappauf C., Schest E., Reif P., Lang U., Tamussino K., Schoell W. Extraperitoneal versus transperitoneal cesarean section: a prospective randomized comparison of surgical morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4) doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.057. 338.e1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao Ji, Meng C., Eichen Q. Extraperitoneal versus transperitoneal cesarean section: a retrospective study. Post Med. 2023;135(1):38–42. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2022.2124774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaswani B.P., Trivedi A., Gopal S. Extraperitoneal versus transperitoneal cesarean section: a retrospective analysis. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2020;9:567–569. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma P.P., Gond S., Ansari M.D.K., Madhuri N., Bera S.N. Extraperitoneal cesarean section: a retrospective analysis. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2020;9(3):1089. [Google Scholar]