Abstract

The North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is a tropical fruit that is known to be the largest edible fruit native to the United States. The fruit has remained uncommercialized because of the rapid changes in quality that occur after the fruit is harvested. However, only a few studies have evaluated the quality of the fruit during postharvest storage. This study aimed to assess the effect of different concentrations of chitosan and sodium alginate coatings, and freshness paper treatments on the quality characteristics of pawpaw fruits during storage and use TOPSIS-Shannon entropy analyses to determine which treatment best maintains the quality of the fruits from three cultivars. The results show that the chitosan coatings were more effective in slowing moisture loss in Sunflower fruits than in Susquehanna and 10–35 fruits over time. Similarly, the freshness paper treatment controlled moisture loss more effectively than sodium alginate coatings. The 10–35 fruits with 1% chitosan coating had very little change in skin color and physical appearance compared to all the other treatments. The TOPSIS-Shannon entropy analyses showed that the 10–35 fruits with 1% chitosan had the most stable quality over time, followed by the Susquehanna and Sunflower fruits with 2% chitosan coatings. The experimental data from different cultivars, treatments, and storage conditions, proved the shelf-life of pawpaw fruit could be extended from 5 days to 15–20 days depending on the cultivar. These findings will enable the creation of markets for pawpaw fruits and allow countries that grow them to generate revenue from this underutilized specialty crop.

Keywords: Asimina, Pawpaw fruit, Shelf life, Chitosan, Sodium alginate, TOPSIS analyses

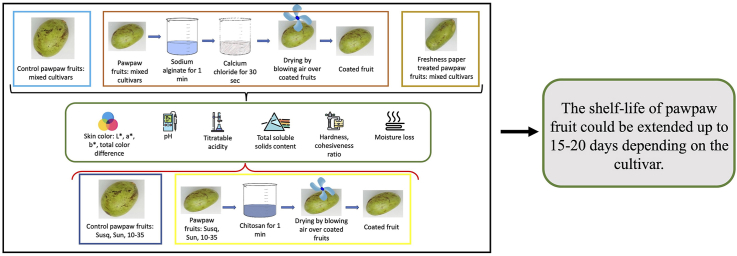

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The North American pawpaw fruit has a shelf life of 3–5 days.

-

•

The fruit has remained uncommercialized and underutilized for hundreds of years.

-

•

Rapid changes in color and texture within 5 days, and short shelf life are the bottlenecks that hinder pawpaw usage.

-

•

Findings from this study show that edible coatings can extend the shelf life of the fruit from 5 days to 15–20 days.

Credit authors statement

Bezalel Adainoo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing, – Entire Manuscript, Writing – review & editing; Andrew L. Thomas: Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing; Kiruba Krishnaswamy: Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

1. Introduction

The North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is the largest edible fruit native to the United States; however, the fruit has remained underutilized due to the rapid change in quality during storage. It grows in over 30 states in the United States, Canada, and other parts of the world. The fruit belongs in the Annonaceae family with many commercially produced tropical fruits like soursop, cherimoya, sugar apple, and others. Pawpaw is a low acid fruit that has a very short shelf life characterized by rapid discoloration of the skin and pulp, and loss in fruit firmness within 5 days (Adainoo et al., 2022; Galli et al., 2008). Some studies have attempted to extend the shelf life of the fruit with the application of cold storage technologies. However, these have had limited success in retaining the quality characteristics of the whole fruit during the storage period. To date, no studies have been conducted to test the effect of edible coatings and freshness paper treatments on the quality characteristics of the North American pawpaw fruit during storage, making this the first research attempt at extending the shelf life of the whole pawpaw fruit using edible coatings and freshness paper treatments. Studying the effect of technologies that could extend the shelf life of the fruit would directly promote the creation of a market niche for shelf-stable pawpaw fruits thereby driving the economic growth of the fruit in countries that cultivate it. Studies on other fruits in the Annonaceae family like cherimoya and soursop have shown that edible coatings help to maintain postharvest quality and extend the shelf life (de Los Santos-Santos et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2016).

Edible coatings are environmentally friendly systems that when applied to horticultural products control moisture loss and gas transfer during the respiration of fruits and vegetables after postharvest, thereby controlling their quality characteristics and extending the shelf life of the products (Dhall, 2013; Souza et al., 2010). Although some fruits and vegetables respire more than others, generally, they all continue to respire after they have been harvested. Hence, these edible coating systems provide storage conditions similar to modified atmosphere storage systems that help to preserve the fruits and vegetables by controlling the internal gas composition of the fruit or vegetable (Park, 1999). Edible coatings have been successfully used to extend the shelf lives of whole fruits and vegetables including apples, oranges, peaches, lemons, avocados, and tomatoes. The coatings have also been successfully applied to fresh-cut fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, cheese, and other food products (Chiumarelli et al., 2011; Zambrano-Zaragoza et al., 2018). There are several advantages of edible coatings. They are economical, readily available, offer barrier properties and some mechanical strength, and help to prevent contamination of the fruit skin, which reduces the chances of fruit deterioration by preventing microbial contamination, browning, development of off-flavors, solute migration, and texture breakdown (Dhall, 2013; Zambrano-Zaragoza et al., 2018).

Edible coatings can be made of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, or a blend of these components. Examples of materials that have been used in edible coatings include sodium alginate, methylcellulose, chitosan, pectin, aloe vera gel, whey proteins, soy proteins, and lactic acid (Yousuf et al., 2018). Chitosan coatings have been known to possess antimicrobial properties in addition to the barrier properties they offer. Further, edible coating formulations can be modified with the addition of other preservation agents like essential oils, organic acids, polypeptides, nanoemulsions, nanotubes, nanoparticles, and other nanosystems to improve the efficiency of the coating system (Dhall, 2013; Franssen and Krochta, 2003; Zambrano-Zaragoza et al., 2018).

Various studies have explored the potential of loaded paper technologies (paper loaded with essential oil or antimicrobial compounds) for extending the shelf life of foods. These technologies provide the opportunity for creating an active packaging that continually releases preserving agents like essential oils to prevent superficial microbial growth, extend shelf life and in some cases enhance the sensory appeal of foods (Ataei et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2021). In this study, the freshness paper used is a commercially available fenugreek-loaded paper for preserving perishable products (Shukla, 2002).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of different concentrations of chitosan and sodium alginate coatings, and freshness paper treatments on the quality characteristics of three cultivars of North American pawpaw fruits and use TOPSIS-Shannon entropy analyses to compare the treatments to identify which one best maintains the quality of the fruits from three cultivars during storage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fruit samples

Ripe pawpaw fruits harvested from the lower orchard at the Southwest Research, Extension, and Education Center of the University of Missouri (lat. 37.08582, long. −93.86713) were used for this study. The orchard had a fertile alluvial soil that was deep and well-drained. Seventy-three (73) ripe pawpaw fruits of different cultivars (Susquehanna, Sunflower, Shenandoah, Atwood, 10–35, Wells, Wilson, Prolific, NC-1) were harvested at peak ripeness in September 2021, placed in zippered plastic bags and transported to the laboratory on ice. The fruits were harvested at peak ripeness, which was determined by the pitting on the skin when the fruit is gently pressed with a finger. These fruits were mixed and treated with freshness papers and sodium alginate coatings and studied over a 25-day storage period.

Ripe pawpaw fruits of the Susquehanna (71 fruits), Sunflower (101 fruits) and 10–35 cultivars (99 fruits) were harvested from the same orchard at peak ripeness in August/September 2022, placed in open totes and transported to the laboratory. These fruits were treated separately by cultivar with chitosan coatings and studied over a 25-day storage period.

2.2. Treatments

From the mixed fruit group, fruits of similar color and size were selected and randomly divided into four groups for the treatments: control, freshness paper treatment, coating with 1 g sodium alginate in 1 L distilled water (0.001% alginate) and coating with 5 g sodium alginate in 1 L distilled water (0.005% alginate). Control fruits received no treatment. The control fruits were placed in an open Styrofoam box. Fruits given freshness paper treatment were placed in an open Styrofoam box, and freshness papers (Freshpaper, The Freshglow Co., Maryland, USA) cut into 5×4 cm pieces were placed on top of each fruit in the box as described by the manufacturer. The sodium alginate treated fruits were also placed in separate open Styrofoam boxes. All the boxes with the fruits were kept in a refrigerator at 4 °C (75% RH) and 3–5 fruits randomly selected from each treatment were analyzed at 5-day intervals for pH, titratable acidity, total soluble solids, moisture loss, skin color, hardness, and cohesiveness ratio.

The fruits for the each of the cultivars (Susquehanna, Sunflower and 10–35) were each randomly grouped into three subsets for treatments: control, 1% chitosan coating and 2% chitosan coating. The fruits for each cultivar and treatment were placed in separate open totes and stored in a cold room with an average temperature of 6 °C (80% RH), and 3–5 fruits randomly selected from each cultivar-treatment combination were analyzed at 5-day intervals for pH, titratable acidity, total soluble solids, moisture loss, skin color, hardness, and cohesiveness ratio.

2.2.1. Preparation of sodium alginate coating solutions and coating of pawpaw fruits

Two different concentrations of sodium alginate were used in this study. 0.001% (w/v) and 0.005% (w/v) sodium alginate solution were prepared by dissolving sodium alginate (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) in distilled water while stirring. A 2% (w/v) solution of calcium chloride (Fisher Scientific, NJ, USA) was prepared to be used in the coating to induce crosslinking of the sodium alginate for the formation of the coating film on the skin of the fruits.

The fruits were washed with tap water at room temperature to remove debris on the skin. The fruits were coated following the method outlined by Maftoonazad et al. (2008). Pawpaw fruits for the two treatments: 0.001% sodium alginate coating and 0.005% sodium alginate coating, were dipped in the respective sodium alginate coating solutions for 60 s at 20 °C and the excess coating solution was allowed to drip off. The fruits were then immersed in the calcium chloride solution for 30 s. The films formed on the fruits were dried by blowing air on the surface of the fruits with a tabletop fan.

2.2.2. Preparation of chitosan coating solutions and coating of pawpaw fruits

The chitosan coating solutions were prepared according to the procedure described by Arnon et al. (2015). 1% (w/v) and 2% (w/v) chitosan coating solutions were prepared and used in this study. Chitosan solution was prepared by dissolving low molecular weight (50,000–190,000 Da) chitosan powder (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in distilled water containing 0.07% (v/v) glacial acetic acid (Fisher Chemicals, Fair Lawn, NJ). The chitosan solutions were stirred at room temperature with a magnetic stirrer overnight. The pH of the chitosan solutions was adjusted with 0.1N sodium hydroxide to a pH of 5.01.

The fruits were washed with tap water at room temperature to remove debris on the skin and sanitized by wiping the skin with paper tissue containing 70% ethanol. The fruits were then coated by dipping them in the chitosan solution for 60 s. They were then removed from the chitosan solution and placed on a rack to allow the excess coating solutions to drip off and dried by blowing air on the surface of the fruits with a tabletop fan.

2.3. pH and titratable acidity

The pH of the pulp was measured using a digital pH meter (SevenCompact S220, Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) at room temperature (25 °C). The measurements were taken in triplicates. Titratable acidity was determined according to the AOAC Official Method 942.15 (AOAC, 2000). Five grams of the fruit pulp was mixed with 25 ml of distilled water, blended in a kitchen blender for 2 min to obtain a homogeneous mixture and titrated against 0.1N NaOH using phenolphthalein as indicator. The analyses were performed in triplicates and the titratable acidity was reported as milligrams of acetic acid per 100 ml of sample (Nam et al., 2018).

| Acetic acid eq. weight = 60.052 g |

2.4. Total soluble solids

Total soluble solids (TSS) content was measured according to the AOAC Official Method 932.14C (AOAC, 2000) using a digital refractometer (HI96800, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) at room temperature (25 °C). A sample of the pulp was placed in the sample well of the refractometer. The total soluble solids measurements were taken in triplicates and recorded as Brix.

2.5. Percentage moisture loss

Moisture loss was determined by weighing the fruits at 5-day intervals (final weight) using a digital balance and reporting the difference in weight compared to their weight on day 0 (initial weight) as percentage moisture loss.

2.6. Skin color

Color of fruit skin was measured using the Hunter LAB color meter (Chroma Meter CR-410, Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). Four readings for each fruit were read at four different points on the skin of the fruit. The recordings were used to calculate the total color difference (ΔE or Delta E), and chroma using the equations below where, L* is degree of lightness to darkness, a* is degree of redness to greenness, b* is degree of yellowness to blueness; the subscripts f and i denote final (day 5–25 fruits) and initial (day 0 fruits) values and presented as means and standard deviations. Chroma represents the saturation of the skin color and ΔE is a measure of total color difference between a reference color (skin color at day 0) and the skin color at a particular time point (skin color at days 5–25).

2.7. Texture analyses

Textural properties of the fruits were determined following the method described by Adainoo et al. (2023). Samples were analyzed for their hardness and cohesiveness using a Texture Analyzer (TA.HDPlus C, Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, UK) equipped with a 100 kg load cell and connected to the Exponent Connect Software (Stable Micro Systems). A P/75 (7.5 cm diameter) compression plate was used for the analyses. The texture analyzer was programmed to carry out a texture profile analysis with the following test conditions: pretest speed of 1 mm/s, test speed of 1 mm/s, posttest speed of 1 mm/s, trigger force of 5 g, compression distance of 10 mm and a time of 5sec between compressions. Hardness was recorded as kilograms of force (kg) and cohesiveness ratio was recorded as percentages (%). Hardness values were the maximum force of the first compression in a Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) while cohesiveness is a measure of the strength of the internal bonds that keep a food sample intact (Kamal-Eldin et al., 2020; Kasapis and Bannikova, 2017). Cohesiveness, in a TPA, is ratio of the area of second compression to the area of first compression as expressed in the equation below. Three to five fruits for each treatment-time combination were tested and the results were averaged.

2.8. TOPSIS-Shannon entropy analyses

In this study, TOPSIS-Shannon entropy analyses were used to decide which treatment and cultivar performed best in extending the shelf life of the pawpaw fruits based on the physical and physicochemical properties analyzed. The Shannon entropy method was used to determine the weight vectors for the criteria (the parameters analyzed) which was then used in the TOPSIS (technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution) analyses. TOPSIS was carried out with the data obtained to evaluate the effect of the different treatments on the fruits from the different cultivars. From this, the distance of alternatives (the different treatments on the cultivars) from the positive and negative ideal solutions were determined and the treatments were ranked. The analyses were carried out as described by Ansarifar et al. (2015) and Khodaei et al. (2021). The method is summarized as follows.

-

1.

Construction of a decision-making matrix with a list of alternatives (treatments) as row labels and the factors to be considered (physical and physicochemical properties analyzed) as column headings using the mean for each of the factors over the storage period

-

2.

Normalization of the decision-making matrix

i = 1, 2 … …m, j = 1, 2 … …n; m = number of alternatives, n = number of factors considered.

-

3.

Calculation of the weights for the criterion and develop the normalized weight matrix

The weight of each criterion was determined using the Shannon entropy method using the following steps.

-

a.

Design the decision-making matrix

-

b.

Design the normalized decision-making matrix

-

c.

Calculation of the entropy for each criterion

-

d.

Calculation of the distance of each criterion from the entropy (degree of diversification)

-

e.

Calculation of the weights of each criterion from the entropy

-

4.

Determination of the ideal solution: the ideal best solution is made of the optimal value of every factor from the weighted decision-making matrix, and the ideal worst solution is made of the worst value of every factor from the weighted decision-making matrix.

where the ideal value and negative ideal value are determined by how the maximum and minimum values of the factors affect the quality of the fruit. For example, high L* values suggest more fresh ripe fruits compared to ripe fruits with low L* values. Hence, a high weighted performance value will be the ideal best for L* and a low weighted performance value will be the ideal worst for L*.

-

5.

Determination of the distance of the normalized weighted matrix from ideal best and ideal worst (Euclidean distances)

-

6.

Calculation of the performance scores

-

7.

Ranking the treatments

2.9. Statistical analyses

All experimental data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The data for the treatments at the time intervals (Day 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25) were analyzed by analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) and Tukey's test (p < 0.05) for significant differences using Mintab version 18 software (Minitab Inc., PA, USA). The one-way ANOVA was conducted within the treatment groups, comparing within individual treatment groups for respective cultivars (eg. compared cultivar Susquehanna control, day 0, 5, 10, 15; Susquehanna 1% Chitosan, day 0, 5, 10, 15; Susquehanna 2% chitosan, day 0, 5, 10, 15) and denoted by lowercase superscript (a), and between the treatment groups comparing between all treatment groups for respective cultivars (eg. compared cultivar Susquehanna control, day 0 compared to all 16 treatment levels). This is denoted by uppercase superscript (A). The overall variability (in terms of the parameters analyzed) among treatments during storage was analyzed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA was performed using OriginPro 2021 version 9.8.0 software (Origin Lab Inc., Northampton, Massachusetts, USA). Microsoft Excel version 16.69 was used to run the TOPSIS analyses.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. pH and titratable acidity

Fruit acidity is a key indicator of quality because organic acids present in fruits contribute significantly to their flavor and aroma volatiles (Batista-Silva et al., 2018). In fruits like strawberries and mangoes, it has been found that during storage, pH increases while titratable acidity decreases possibly due to the oxidation of the acids during storage (Alharaty and Ramaswamy, 2020; Cosme Silva et al., 2017; Islam et al., 2013). Other studies have reported that for fruits in the Annonaceae family like atemoya and soursop, and others like banana, pH decreases and titratable acidity increases during storage (Pareek et al., 2011; Rahman et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2009). This is likely due to the production of more organic acids from the fermentation of the sugars in the fruits.

The data obtained in this study show that Susquehanna fruits in the control group and the chitosan treatment groups had no significant change (p > 0.05) in their pH and titratable acidity during the storage period at 4 °C (Table 1). However, there was a higher difference in the pH of the control fruits between day 0 (6.23 ± 0.49) and day 15 (5.65 ± 0.54) compared to the difference in pH for the 2% chitosan coated fruits between day 0 (6.36 ± 0.47) and day 15 (6.00 ± 0.81). The pH difference between day 0 and day 15 for both control and 1% chitosan coated fruits was similar. Further, it took up to day 20 for the pH of the 2% chitosan coated fruits to reach a pH less than 5.98, which is the minimum pH for good quality Susquehanna pawpaw pulp according to Adainoo et al. (2022), whereas the 1% chitosan coated fruits recorded an average pH less than 5.98 by day 10. This suggests that the 2% chitosan coating was more effective in controlling the change in pH of the Susquehanna fruits during storage. For all the Susquehanna fruit treatments, there were no clear patterns in the change of the titratable acidity of the fruits during the storage period. This may have been due to the change in the type of acid and concentration of the different acids during the storage since studies have shown that organic acid composition and concentrations in pawpaw fruits change as they continue to mature (Park et al., 2022). The pulp of unripe fruits has a high concentration of citric acid (229.98 ± 2.19 mg/100 g fresh weight) and no acetic acid detected, but as they ripen and mature, the concentration of citric acid reduces to an average of 8.65–16.20 mg/100 g fresh weight and acetic acid becomes the predominant acid with a concentration of 61.59 ± 0.92 mg/100 g fresh weight (Pande and Akoh, 2010; Park et al., 2022). Further, the titratable acidity of the Susquehanna fruits used in this study were significantly higher than the values (45.00 ± 15.97 mg of acetic acid/100 g) reported by Adainoo et al. (2022).

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties, skin color, and textural properties of chitosan-coated North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) fruits of the Susquehanna cultivar during a 25-day storage at 6 °C.

| Treatment | Day | pH | Titratable Acidity (mg of acetic acid/100 ml) | Total soluble solids (Brix) | Moisture loss (%) | L* | a* | b* | Chroma | ΔE | Hardness (kg) | Cohesiveness ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

0 | 6.23 ± 0.49 aA | 101.42 ± 16.67 aA | 24.09 ± 2.82 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00bF | 45.75 ± 1.43 aA | −9.56 ± 0.44 cA | 19.86 ± 1.06 aA | 22.07 ± 0.79 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 dB | 5.4 ± 0.7 aA | 29.76 ± 2.96 bD |

| 5 | 5.84 ± 0.61 aA | 168.15 ± 40.03 aA | 24.94 ± 5.77 aA | 7.20 ± 0.52aAB | 41.69 ± 1.52 bA | −5.71 ± 1.07 bA | 17.43 ± 2.27 aA | 18.41 ± 2.11 bA | 7.03 ± 1.42 cAB | 3.8 ± 0.8 abAB | 31.98 ± 2.16 bCD | |

| 10 | 5.79 ± 0.78 aA | 130.78 ± 30.31 aA | 24.73 ± 2.98 aA | 7.20 ± 0.52 aAB | 35.99 ± 1.47 cA | −1.15 ± 2.00 aA | 10.99 ± 0.40 bA | 11.23 ± 0.48 cA | 15.73 ± 3.06 bAB | 2.5 ± 1.4 bB | 44.31 ± 3.66 aABCD | |

| 15 |

5.65 ± 0.54 aA |

136.12 ± 42.37 aA |

18.94 ± 7.21 aA |

7.62 ± 0.25 aA |

32.42 ± 0.73 dA |

1.34 ± 1.08 aA |

6.22 ± 1.18 cA |

6.56 ± 1.23 dA |

22.10 ± 1.19 aAB |

2.4 ± 0.6 bB |

44.56 ± 6.04 aABC |

|

| 1% Chitosan |

0 | 6.20 ± 0.69 aA | 106.76 ± 12.23 aA | 23.64 ± 1.16 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 dF | 50.92 ± 3.94 aA | −8.00 ± 5.35 aA | 24.90 ± 4.02 aA | 26.55 ± 5.10 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 aB | 4.5 ± 1.3 aAB | 34.56 ± 7.72 bCD |

| 5 | 6.06 ± 0.13 aA | 112.10 ± 13.87 aA | 22.96 ± 1.52 aA | 3.78 ± 0.70 cE | 44.16 ± 10.04 aA | −4.68 ± 7.87 aA | 19.68 ± 10.04aA | 21.19 ± 10.65aA | 11.12 ± 8.46 aAB | 4.2 ± 0.4 aAB | 35.86 ± 4.01 bBCD | |

| 10 | 5.61 ± 0.30 aA | 117.44 ± 20.15 aA | 24.09 ± 3.82 aA | 4.45 ± 0.30 bcCDE | 37.60 ± 10.47 aA | −1.84 ± 7.11 aA | 13.60 ± 11.39aA | 15.05 ± 11.41aA | 19.48 ± 11.30 aAB | 3.1 ± 1.2 aAB | 37.37 ± 5.48 bABCD | |

| 15 | 5.56 ± 0.32 aA | 114.77 ± 12.23 aA | 22.29 ± 3.00 aA | 5.61 ± 0.51abBCD | 36.83 ± 9.56 aA | −0.38 ± 7.00 aA | 11.68 ± 10.02aA | 13.20 ± 10.05aA | 21.88 ± 10.53 aAB | 2.7 ± 1.0 aB | 44.06 ± 5.27 abABCD | |

| 20 | 5.75 ± 0.74 aA | 98.75 ± 32.36 aA | 22.04 ± 0.69 aA | 5.76 ± 0.26 abBCD | 35.08 ± 9.93 aA | 0.00 ± 6.22 aA | 8.28 ± 10.12 aA | 10.11 ± 9.94 aA | 24.59 ± 13.53 aA | 2.4 ± 0.9 aB | 51.80 ± 0.65 aA | |

| 25 |

5.57 ± 0.61 aA |

114.77 ± 25.74 aA |

22.88 ± 1.81 aA |

6.94 ± 0.86 aAB |

35.30 ± 10.03 aA |

−0.19 ± 6.24 aA |

8.31 ± 10.89 aA |

10.17 ± 10.68aA |

25.00 ± 13.21 aA |

2.0 ± 0.2 aB |

51.74 ± 0.89 aA |

|

| 2% Chitosan | 0 | 6.36 ± 0.47 aA | 122.77 ± 25.74 aA | 26.29 ± 2.72 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 cF | 50.89 ± 5.15 aA | −9.95 ± 5.19 aA | 23.34 ± 3.55 aA | 26.16 ± 4.33 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 bB | 4.2 ± 0.3 aAB | 32.62 ± 4.73 bCD |

| 5 | 6.26 ± 0.60 aA | 104.09 ± 0.00 aA | 18.17 ± 2.89 bA | 4.12 ± 1.09 bDE | 51.20 ± 2.89 aA | −11.70 ± 1.95 aA | 24.33 ± 2.17 aA | 27.02 ± 2.79 aA | 5.54 ± 2.90 abAB | 4.1 ± 0.8 aAB | 34.61 ± 3.43 bCD | |

| 10 | 6.28 ± 0.67 aA | 109.43 ± 23.11 aA | 23.44 ± 0.52 abA | 4.27 ± 0.13 bCDE | 48.29 ± 5.50 aA | −9.56 ± 3.39 aA | 20.93 ± 4.65 aA | 23.07 ± 5.60 aA | 9.18 ± 2.26 abAB | 3.6 ± 1.5 abAB | 34.44 ± 10.33 bCD | |

| 15 | 6.00 ± 0.81 aA | 101.42 ± 64.72 aA | 23.08 ± 2.24 abA | 5.61 ± 0.94 abBCD | 47.15 ± 6.66 aA | −7.88 ± 4.00 aA | 19.70 ± 5.62 aA | 21.30 ± 6.69 aA | 9.06 ± 3.22 abAB | 2.7 ± 0.1 abB | 43.60 ± 3.96 abABCD | |

| 20 | 5.72 ± 0.46 aA | 88.08 ± 36.69 aA | 24.84 ± 3.93 abA | 6.01 ± 0.63 abABC | 42.10 ± 9.83 aA | −4.42 ± 6.55 aA | 14.07 ± 9.11 aA | 15.09 ± 10.62 aA | 15.58 ± 8.52 aAB | 1.9 ± 0.2 abB | 50.22 ± 4.10 abAB | |

| 25 | 5.34 ± 0.11 aA | 165.48 ± 28.12 aA | 24.21 ± 2.03 abA | 6.86 ± 0.79 aAB | 39.99 ± 9.69 aA | −2.93 ± 7.02 aA | 11.86 ± 10.37 aA | 13.01 ± 11.42 aA | 18.85 ± 9.64 aAB | 2.6 ± 0.6 bB | 42.42 ± 1.68 aABCD |

Control fruits showed the presence of mold growth on the fruit skin after day 15, hence, they were not analyzed after day 15.

Means for the parameters in each treatment that do not share a superscript are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Lowercase superscripts represent statistical differences within treatment groups for the respective treatments and uppercase superscripts represent statistical differences between all treatment groups at p ≤ 0.05.

The Sunflower control fruits had no statistically different pH from day 0 to day 10, but at day 15 the pH of the fruits was significantly different from the pH at the previous time points (Table 2). The pH of the Sunflower fruits with the 1% chitosan coating on the other hand had no significant difference during the storage period until day 25, whereas the Sunflower fruits with the 2% chitosan coating had no significant difference in pH throughout the 25-day storage period. This shows that both chitosan coatings were effective in controlling the change in pH of the Sunflower fruits during storage. The titratable acidity of the control fruits increased with time suggesting the fermentation of the sugars in the fruits, however, in the chitosan coated fruits, the titratable acidity remained statistically similar throughout the storage period and close to the values reported for Sunflower fruits by Adainoo et al. (2022). This shows the chitosan coatings were effective in controlling the formation of acids in the Sunflower fruits during storage.

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties, skin color, and textural properties of chitosan-coated North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) fruits of the Sunflower cultivar during a 25-day storage at 6 °C.

| Treatment | Day | pH | Titratable Acidity (mg of acetic acid/100 ml) | Total soluble solids (Brix) | Moisture loss (%) | L* | a* | b* | Chroma | ΔE | Hardness (kg) | Cohesiveness ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

0 | 6.53 ± 0.22 aABC | 85.41 ± 4.62 bABCD | 18.49 ± 1.05 Aa | 0.00 ± 0.00 cF | 45.65 ± 0.98 aABCDE | −7.26 ± 1.55 bAB | 24.09 ± 0.59 aABCD | 25.36 ± 0.90 aABCDE | 0.00 ± 0.00 cC | 4.2 ± 0.4 abABC | 24.90 ± 2.02 aEF |

| 5 | 6.43 ± 0.04 aABC | 106.76 ± 16.67 abAB | 19.40 ± 0.46 aA | 5.04 ± 0.74 bBC | 35.28 ± 3.74 bDEF | 0.76 ± 1.37 aAB | 12.11 ± 5.43 bDEF | 12.59 ± 4.92 bDEF | 18.08 ± 5.79 bABC | 4.6 ± 0.4 aA | 21.99 ± 1.87 aF | |

| 10 | 6.28 ± 0.04 aABCD | 93.41 ± 16.67 abABC | 19.07 ± 1.11 aA | 6.01 ± 0.88 abAb | 31.13 ± 1.23 bcEF | 2.91 ± 0.46 aA | 5.65 ± 0.12 bcEF | 6.89 ± 0.06 bcEF | 25.79 ± 0.81 abAB | 3.5 ± 0.3 bcABCDEF | 27.83 ± 3.13 aDEF | |

| 15 |

5.67 ± 0.20 bD |

122.77 ± 4.62 aA |

19.48 ± 1.17 aA |

7.39 ± 1.35 aA |

27.42 ± 0.61 cF |

2.99 ± 0.25 aA |

0.91 ± 0.93 cF |

3.48 ± 0.64 cF |

31.36 ± 2.00 aA |

2.8 ± 0.4 cDEFG |

27.68 ± 3.26 aDEF |

|

| 1% Chitosan |

0 | 6.71 ± 0.05 aAB | 80.07 ± 24.02 aBCDE | 20.09 ± 0.47 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 dF | 60.04 ± 0.53 aA | −8.65 ± 1.25 Aab | 37.77 ± 3.42 aA | 39.52 ± 2.67 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 bC | 4.3 ± 0.3 aAB | 32.22 ± 4.39 bABCDEF |

| 5 | 6.64 ± 0.09 aAB | 61.39 ± 20.15 aCDEF | 19.52 ± 3.73 aA | 1.64 ± 0.41 cEF | 54.63 ± 2.80 aABC | −7.26 ± 6.24 aAB | 34.27 ± 2.37 aAB | 35.47 ± 2.51 aAB | 11.42 ± 0.71 abABC | 3.8 ± 0.9 abABCD | 31.32 ± 5.01 bBCDEF | |

| 10 | 6.49 ± 0.13 aABC | 48.04 ± 8.01 aDEF | 18.63 ± 0.50 aA | 1.64 ± 0.41 cEF | 50.73 ± 5.55 aABCD | −5.14 ± 7.85 aAB | 29.80 ± 4.05 aABCD | 30.91 ± 5.26 aABCD | 16.36 ± 3.53 abABC | 3.3 ± 0.4 abcBCDEF | 31.97 ± 2.24 bABCDEF | |

| 15 | 6.70 ± 0.19 aAB | 40.03 ± 13.87 aF | 20.18 ± 1.87 aA | 2.58 ± 0.45 bDE | 47.93 ± 8.91 aABCDE | −3.79 ± 8.25 aAB | 25.06 ± 7.89 aABCD | 26.20 ± 9.11 aABCD | 22.19 ± 8.30 abABC | 3.0 ± 0.5 abcCDEF | 40.10 ± 4.47 abAB | |

| 20 | 6.54 ± 0.35 aABC | 58.72 ± 12.23 aCDEF | 18.40 ± 1.61 aA | 2.81 ± 0.17 bDE | 41.93 ± 13.39 aBCDEF | −1.13 ± 9.21 aAB | 19.14 ± 13.57 aBCDEF | 20.54 ± 14.11 aBCDEF | 30.25 ± 16.62 abAB | 2.4 ± 0.5 bcEFG | 42.34 ± 1.11 abA | |

| 25 |

5.94 ± 0.07 bCD |

50.71 ± 4.62 aDEF |

19.78 ± 0.53 aA |

3.97 ± 0.23 aCD |

39.84 ± 12.35 aCDEF |

0.64 ± 6.55 aAB |

14.94 ± 13.23 aCDEF |

16.13 ± 12.99 aCDEF |

33.75 ± 17.11 aA |

2.3 ± 0.1 cFG |

38.27 ± 2.60 aABC |

|

| 2% Chitosan | 0 | 6.78 ± 0.21 abA | 53.38 ± 12.23 aDEF | 19.40 ± 1.21 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 cF | 58.24 ± 1.84 aAB | −12.16 ± 1.36 bB | 35.37 ± 3.20 aAB | 37.50 ± 2.63 aAB | 0.00 ± 0.00 cC | 4.1 ± 0.2 aABC | 28.83 ± 1.65 bCDEF |

| 5 | 6.66 ± 0.43 abAB | 42.70 ± 12.23 aEF | 19.81 ± 1.34 aA | 1.43 ± 0.37 bEF | 55.66 ± 1.50 aABC | −10.15 ± 3.43 abAB | 34.41 ± 3.42 aAB | 36.11 ± 2.57 aAB | 6.81 ± 1.76 bcBC | 3.7 ± 0.5 abABCDE | 27.05 ± 1.95 bDEF | |

| 10 | 6.56 ± 0.23 abABC | 42.70 ± 9.25 aEF | 18.66 ± 1.06 aA | 1.43 ± 0.37 bEF | 54.05 ± 0.46 abABC | −6.31 ± 4.01 abAB | 32.68 ± 1.53 abABC | 34.04 ± 0.74 aABC | 9.92 ± 4.71 bcABC | 2.6 ± 0.2 bcDEFG | 34.92 ± 0.66 abABCDE | |

| 15 | 6.89 ± 0.22 aA | 32.03 ± 13.87 aF | 18.91 ± 2.97 aA | 2.57 ± 0.42 abDE | 50.49 ± 2.78 abABCD | −6.09 ± 4.97 abAB | 28.91 ± 1.61 abABCD | 29.92 ± 2.40 abABCD | 13.21 ± 7.43 abcABC | 2.8 ± 0.6 cdDEFG | 40.95 ± 6.12 aAB | |

| 20 | 6.40 ± 0.39 abABC | 37.37 ± 4.62 aF | 18.71 ± 0.82 aA | 3.70 ± 0.62 aCD | 45.21 ± 6.06 bcABCDE | −2.85 ± 4.85 abAB | 21.99 ± 7.42 bcABCDE | 22.70 ± 7.74 bcABCDE | 21.35 ± 12.77 abABC | 2.2 ± 0.1 cdFG | 35.47 ± 5.72 abABCD | |

| 25 | 6.08 ± 0.06 bBCD | 48.04 ± 0.20 aDEF | 18.74 ± 0.91 aA | 3.70 ± 0.62 aCD | 39.51 ± 4.76 cCDEF | 0.08 ± 3.69 aAB | 13.77 ± 5.17 cDEF | 14.80 ± 4.64 cDEF | 31.25 ± 10.27 aA | 1.7 ± 0.1 dG | 36.33 ± 2.79 abABCD |

Control fruits showed the presence of mold growth on the fruit skin after day 15, hence, they were not analyzed after day 15.

Means for the parameters in each treatment that do not share a superscript are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Lowercase superscripts represent statistical differences within treatment groups for the respective treatments and uppercase superscripts represent statistical differences between all treatment groups at p ≤ 0.05.

All the fruits of the 10–35 cultivar had no visible mold growth on their skin throughout the study, hence were analyzed for the full duration. During this period, there were slight changes in the pH of the fruit pulp of the 10–35 control and 1% chitosan coated fruits, but the pH of the 2% chitosan coated fruits remained statistically similar (Table 3). Nonetheless, the titratable acidity remained statistically similar for all the 10–35 treatment groups. The reason for this is in the control fruits unclear, however, this may be attributed to the changes in the composition and concentrations of the organic acids in the fruits of this cultivar over time as identified by Park et al. (2022) in pawpaw fruits as they ripen and mature. Also, it is possible that slight differences in the maturity of the fruits analyzed in this study during the storage period could have accounted for the similar titratable acidity of the control fruits. From this, it is evident that the chitosan coatings effectively controlled the change in the acid content of the 10–35 fruits over time.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties, skin color, and textural properties of chitosan-coated North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) fruits of the 10–35 cultivar during a 25-day storage at 6 °C.

| Treatment | Day | pH | Titratable Acidity (mg of acetic acid/100 ml) | Total soluble solids (Brix) | Moisture loss (%) | L* | a* | b* | Chroma | ΔE | Hardness (kg) | Cohesiveness ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

0 | 6.71 ± 0.12 aA | 88.08 ± 13.87 aA | 22.38 ± 1.00 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 dG | 48.07 ± 2.34 aAB | −7.16 ± 0.85 dDEFGH | 26.74 ± 3.17 aAB | 27.76 ± 2.88 aAB | 0.00 ± 0.00 cH | 3.7 ± 0.5 aA | 26.69 ± 1.40 bC |

| 5 | 6.28 ± 0.39 abA | 74.73 ± 48.92 aA | 21.24 ± 3.82 aA | 2.82 ± 0.60 cCDE | 45.20 ± 1.26 aABC | −4.92 ± 1.25 cdCDEFG | 25.31 ± 2.15 abAB | 25.88 ± 1.97 abABC | 6.84 ± 3.37 cEFGH | 3.8 ± 1.4 Aa | 30.60 ± 2.06 abBC | |

| 10 | 6.06 ± 0.47 abA | 66.72 ± 24.46 aA | 19.51 ± 0.70 aA | 3.46 ± 0.14 cCD | 42.67 ± 3.51 abABCD | −2.51 ± 2.62 bcABCDEF | 22.78 ± 5.02 abABC | 23.08 ± 5.03 abABCD | 10.37 ± 5.00 bcCDEFGH | 3.2 ± 1.2 aA | 36.27 ± 7.78 abABC | |

| 15 | 6.02 ± 0.48 abA | 61.39 ± 30.31 aA | 20.48 ± 2.46 aA | 3.82 ± 1.08 bCD | 36.80 ± 3.90 bcBCDE | 0.97 ± 1.87 abABC | 14.36 ± 6.13 bcBCDE | 14.73 ± 5.74 bcBCDE | 19.08 ± 7.19 abABCDE | 3.3 ± 0.9 aA | 41.19 ± 6.22 aABC | |

| 20 | 5.41 ± 0.18 bA | 74.73 ± 4.62 aA | 21.18 ± 3.30 aA | 5.26 ± 0.45 abAB | 33.35 ± 3.32 cdDE | 3.52 ± 1.49 aAB | 8.66 ± 4.81 cdDE | 9.74 ± 4.56 cDE | 25.85 ± 4.62 aAB | 2.4 ± 0.6 aA | 32.35 ± 2.29 abABC | |

| 25 |

5.93 ± 0.60 abA |

66.72 ± 16.67 aA |

20.50 ± 3.60 aA |

6.62 ± 0.74 aA |

28.79 ± 1.79 dE |

3.81 ± 1.47 aA |

2.59 ± 2.86 dE |

4.82 ± 2.86 cE |

29.47 ± 0.72 aA |

1.9 ± 0.4 aA |

31.78 ± 6.86 abBC |

|

| 1% Chitosan |

0 | 6.61 ± 0.33 abA | 58.72 ± 4.62 aA | 18.66 ± 1.90 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 eG | 50.96 ± 1.52 aA | −13.35 ± 1.51 bH | 28.09 ± 1.15 aA | 31.15 ± 1.50 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 bH | 3.8 ± 1.4 aA | 32.28 ± 7.62 aABC |

| 5 | 6.67 ± 0.29 aA | 69.39 ± 16.67 aA | 19.80 ± 1.88 aA | 1.59 ± 0.50 dEF | 49.81 ± 2.32 aA | −13.00 ± 1.44 bH | 27.20 ± 1.23 aAB | 30.17 ± 1.52 aA | 2.94 ± 1.16 bGH | 3.3 ± 0.5 aA | 31.22 ± 4.36 aBC | |

| 10 | 6.45 ± 0.28 abcA | 74.73 ± 4.62 aA | 17.97 ± 1.87 aA | 2.53 ± 0.26 cdDE | 48.43 ± 2.53 aA | −11.64 ± 1.65 abGH | 25.52 ± 1.63 aAB | 28.08 ± 2.15 aAB | 6.65 ± 1.82 abEFGH | 3.6 ± 0.1 aA | 34.94 ± 2.19 aABC | |

| 15 | 6.29 ± 0.55 abcA | 66.72 ± 25.74 aA | 18.70 ± 2.17 aA | 3.12 ± 0.31 bcCD | 46.99 ± 3.97 aABC | −11.06 ± 2.36 abGH | 25.58 ± 2.94 aAB | 27.91 ± 3.62 aAB | 7.96 ± 2.29 abDEFGH | 3.4 ± 0.9 aA | 36.09 ± 9.88 aABC | |

| 20 | 5.72 ± 0.19 bcA | 120.10 ± 48.70 aA | 21.09 ± 0.45 aA | 4.07 ± 0.15 bBC | 45.09 ± 4.43 aABC | −9.17 ± 2.83 abEFGH | 24.74 ± 3.65 aABC | 26.46 ± 4.38 aAB | 9.10 ± 2.69 abDEFGH | 3.3 ± 0.1 aA | 37.45 ± 1.84 aABC | |

| 25 |

5.66 ± 0.32 cA |

93.41 ± 18.49 aA |

20.71 ± 1.55 aA |

5.82 ± 0.69 aA |

42.15 ± 8.21 aABCD |

−4.44 ± 5.79 aBCDEFG |

18.57 ± 8.33 aABCD |

19.80 ± 9.17 aABCD |

17.25 ± 8.58 aABCDEF |

2.2 ± 0.2 aA |

44.62 ± 0.49 aAB |

|

| 2% Chitosan | 0 | 6.56 ± 0.49 aA | 58.72 ± 16.67 aA | 19.12 ± 2.79 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 eG | 49.64 ± 0.45 aA | −11.86 ± 1.48 bGH | 27.08 ± 0.90 aAB | 29.59 ± 1.39 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 cH | 3.1 ± 0.5 aA | 32.16 ± 2.10 bABC |

| 5 | 6.43 ± 0.65 aA | 66.72 ± 18.49 aA | 19.49 ± 0.96 aA | 0.93 ± 0.23 dFG | 46.85 ± 0.90 abABC | −10.01 ± 1.98 bFGH | 25.85 ± 1.21 aAB | 27.76 ± 1.85 abAB | 5.01 ± 1.06 bcFGH | 3.7 ± 1.8 aA | 30.48 ± 7.15 bBC | |

| 10 | 6.38 ± 0.64 aA | 56.05 ± 21.18 aA | 19.70 ± 1.93 aA | 2.64 ± 0.41 cDE | 44.00 ± 3.31 abcABCD | −4.42 ± 0.59 abBCDEFG | 22.02 ± 3.79 abABC | 23.11 ± 4.59 abcABCD | 11.84 ± 1.21 abcCDEFGH | 3.2 ± 0.4 aA | 40.24 ± 5.60 abABC | |

| 15 | 6.03 ± 0.66 aA | 85.41 ± 40.30 aA | 20.76 ± 1.14 aA | 2.82 ± 0.19 cCDE | 40.57 ± 3.63 abcABCD | −4.17 ± 3.84 abABCDEFG | 18.34 ± 4.96 abABCD | 19.00 ± 5.67 abcABCD | 14.98 ± 6.00 abBCDEFG | 3.2 ± 0.1 aA | 39.49 ± 2.28 abABC | |

| 20 | 5.93 ± 0.49 aA | 80.07 ± 27.74 aA | 18.86 ± 1.58 aA | 4.14 ± 0.36 bBC | 36.56 ± 4.92 bcCDE | −1.43 ± 4.02 aABCDE | 14.95 ± 5.73 abABCDE | 15.40 ± 6.08 bcBCDE | 20.80 ± 7.44 aABCD | 2.3 ± 0.4 aA | 44.31 ± 3.56 aAB | |

| 25 | 5.77 ± 0.18 aA | 72.06 ± 13.87 aA | 17.91 ± 1.84 aA | 5.64 ± 0.38 aA | 36.13 ± 6.14 cCDE | 0.28 ± 3.89 aABCD | 11.80 ± 7.56 bCDE | 12.37 ± 7.48 cCDE | 24.19 ± 8.66 aABC | 2.8 ± 0.7 aA | 47.38 ± 2.78 aA |

Means for the parameters in each treatment that do not share a superscript are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Lowercase superscripts represent statistical differences within treatment groups for the respective treatments and uppercase superscripts represent statistical differences between all treatment groups at p ≤ 0.05.

In this study, fruits of different cultivars namely: Susquehanna, Sunflower, Shenandoah, Atwood, 10–35, Wells, Wilson, Prolific, NC-1, were mixed and given different treatments. The pH of the Mixed control and freshness paper treated fruits remained statistically similar throughout the storage period until day 15 after which there were visible mold growths on the skin of the fruits and were not analyzed further (Table 4). The 0.001% alginate coated fruits had no significant change in pH until day 15. The pH of the fruits at days 20 and 25 were significantly different from the pH of the fruits at day 0 but not significantly different from the fruits on day 5 and day 15. Similarly, the fruits coated with the 0.005% alginate solution had no significant change in pH until day 15. The pH of the 0.005% alginate coated fruits at days 20 and 25 were significantly different from the pH of the fruits at day 0 but not significantly different from the fruits on day 5 and day 15. Despite the slight changes in pH over the storage period, the titratable acidity of all the treatments for the Mixed fruits remained statistically the same.

Table 4.

Physicochemical properties, skin color, and textural properties of freshness paper treated and sodium alginate-coated mixed North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) fruits of various cultivars during a 25-day storage at 4 °C.

| Treatment | Day | pH | Titratable Acidity (mg of acetic acid/100 ml) | Total soluble solids (Brix) | Moisture loss (%) | L* | a* | b* | Chroma | ΔE | Hardness (kg) | Cohesiveness ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

0 | 6.52 ± 0.21 aABC | 58.72 ± 16.67 aA | 23.48 ± 2.09 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 cH | 46.83 ± 4.62 aA | −3.65 ± 1.57 aA | 25.07 ± 2.57 aA | 25.44 ± 2.65 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 cC | 4.8 ± 1.2 aAB | 42.36 ± 16.20 aA |

| 5 | 6.07 ± 0.30 aABCD | 82.74 ± 12.23 aA | 23.49 ± 4.55 aA | 1.35 ± 1.05 cGH | 41.19 ± 2.59 aA | −1.15 ± 0.77 aA | 16.69 ± 9.67 aA | 17.32 ± 9.12 aA | 9.99 ± 0.77 bABC | 3.9 ± 0.9 aABC | 35.70 ± 9.41 aA | |

| 10 | 6.01 ± 0.41 aABCD | 77.40 ± 37.84 aA | 25.81 ± 3.62 aA | 6.55 ± 0.61 bBCDE | 39.24 ± 6.82 aA | −0.44 ± 3.87 aA | 15.71 ± 6.14 aA | 16.28 ± 5.19 aA | 11.61 ± 2.14 bABC | 3.1 ± 1.0 aABC | 52.69 ± 0.84 aA | |

| 15 |

5.90 ± 0.60 aABCD |

82.74 ± 33.34 aA |

18.57 ± 7.12 aA |

9.99 ± 0.90 aB |

38.31 ± 4.41 aA |

1.63 ± 1.96 aA |

15.70 ± 5.46 aA |

16.09 ± 6.35 aA |

18.85 ± 2.80 aAB |

2.8 ± 0.2 aABC |

46.05 ± 6.78 aA |

|

| Freshness paper |

0 | 6.44 ± 0.11 aABCD | 64.06 ± 8.01 aA | 23.14 ± 2.60 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 bH | 42.50 ± 2.28 aA | 1.39 ± 0.86 aA | 19.76 ± 2.69 aA | 20.02 ± 2.69 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 bC | 2.9 ± 0.1 aABC | 43.47 ± 6.65 aA |

| 5 | 6.20 ± 0.14 aABCD | 58.72 ± 16.67 aA | 20.27 ± 1.33 aA | 1.55 ± 0.42 bFGH | 42.48 ± 5.49 aA | −1.49 ± 3.86 aA | 14.62 ± 8.71 aA | 19.50 ± 7.96 aA | 9.88 ± 2.90 abABC | 2.7 ± 0.1 aABC | 46.90 ± 1.99 aA | |

| 10 | 6.09 ± 0.51 aABCD | 66.72 ± 36.11 aA | 23.97 ± 0.96 aA | 4.73 ± 0.97 aDEFG | 42.15 ± 6.65 aA | −0.94 ± 4.29 aA | 18.92 ± 7.98 aA | 15.23 ± 9.25 aA | 13.96 ± 7.83 aAB | 2.8 ± 1.3 aABC | 41.73 ± 0.52 aA | |

| 15 |

5.76 ± 0.14 aBCD |

77.40 ± 9.25 aA |

23.13 ± 2.70 aA |

6.01 ± 1.61 aBCDEF |

36.98 ± 5.53 aA |

1.84 ± 1.94 aA |

13.19 ± 6.96 aA |

14.02 ± 6.87 aA |

16.93 ± 3.27 a |

2.5 ± 0.9 aABC |

47.34 ± 6.71 aA |

|

| 0.001% Alginate |

0 | 6.53 ± 0.06 aABC | 56.05 ± 16.01 aA | 22.77 ± 3.42 abA | 0.00 ± 0.00 dH | 46.44 ± 4.90 aA | −4.50 ± 6.01 aA | 23.49 ± 5.23 aA | 24.48 ± 6.03 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 cC | 4.1 ± 1.3 aABC | 39.47 ± 8.10 aA |

| 5 | 6.32 ± 0.33 abABCD | 64.06 ± 0.20 aA | 20.62 ± 0.73 bA | 2.27 ± 0.92 cdEFGH | 45.05 ± 5.02 aA | −3.66 ± 5.09 aA | 23.50 ± 4.61 aA | 24.20 ± 5.39 abA | 8.27 ± 1.79 bcBC | 2.3 ± 0.3 aBC | 50.92 ± 8.08 aA | |

| 10 | 6.25 ± 0.39 abABCD | 58.72 ± 23.11 aA | 24.30 ± 1.80 abA | 5.88 ± 1.24 bcBCDEFG | 42.29 ± 6.32 aA | 1.58 ± 2.60 aA | 13.17 ± 9.13 abA | 19.01 ± 8.26 abA | 15.92 ± 1.76 abAB | 2.6 ± 0.2 aABC | 45.72 ± 5.42 aA | |

| 15 | 5.79 ± 0.19 aBCD | 93.41 ± 32.36 aA | 21.86 ± 1.62 abA | 7.68 ± 2.74 bcBCD | 38.19 ± 6.60 aA | −0.94 ± 2.13 aA | 18.71 ± 8.15 abA | 13.86 ± 8.46 abA | 16.32 ± 7.90 abAB | 2.0 ± 0.4 aC | 53.02 ± 4.92 aA | |

| 20 | 5.68 ± 0.33 bCD | 101.42 ± 32.36 aA | 26.70 ± 2.24 aA | 10.42 ± 2.48 bB | 36.21 ± 6.37 aA | 2.98 ± 1.38 aA | 12.99 ± 6.13 abA | 13.85 ± 5.43 abA | 18.86 ± 4.56 abAB | 2.3 ± 0.3 aC | 47.80 ± 12.90 aA | |

| 25 |

5.56 ± 0.35 bD |

104.09 ± 8.01 aA |

22.97 ± 0.28 abA |

17.34 ± 2.89 aA |

32.58 ± 1.48 aA |

3.64 ± 1.95 aA |

5.38 ± 1.98 bA |

7.08 ± 1.33 bA |

22.39 ± 3.87 aA |

2.5 ± 1.3 aABC |

55.80 ± 2.73 aA |

|

| 0.005% Alginate | 0 | 6.75 ± 0.10 aA | 50.71 ± 4.62 aA | 20.69 ± 1.95 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 eH | 43.79 ± 4.58 aA | −1.96 ± 2.63 aA | 18.96 ± 5.31 aA | 19.32 ± 5.55 aA | 0.00 ± 0.00 bC | 3.9 ± 0.7 abABC | 36.57 ± 2.35 aA |

| 5 | 6.63 ± 0.32 abAB | 64.06 ± 8.01 aA | 22.62 ± 1.00 aA | 2.63 ± 1.19 deEFGH | 45.05 ± 3.58 aA | −1.61 ± 2.24 aA | 20.48 ± 4.15 aA | 21.06 ± 3.88 aA | 8.79 ± 3.13 abBC | 5.1 ± 0.1 aA | 44.44 ± 5.52 aA | |

| 10 | 6.20 ± 0.23 abcABCD | 88.08 ± 16.01 aA | 23.37 ± 1.80 aA | 5.44 ± 1.22 cdCDEFG | 40.39 ± 8.23 aA | −1.74 ± 6.44 aA | 17.32 ± 9.28 aA | 18.18 ± 9.76 aA | 9.33 ± 3.08 abBC | 3.8 ± 0.9 abcABC | 36.12 ± 18.19 aA | |

| 15 | 6.10 ± 0.26 bcABCD | 58.72 ± 25.74 aA | 24.58 ± 3.00 aA | 9.31 ± 0.46 bcBC | 37.63 ± 6.63 aA | 1.01 ± 3.12 aA | 12.39 ± 7.44 aA | 13.17 ± 6.97 aA | 15.71 ± 9.30 aAB | 2.7 ± 1.4 bcABC | 53.76 ± 2.08 aA | |

| 20 | 6.00 ± 0.15 cABCD | 77.40 ± 16.67 aA | 23.20 ± 0.06 aA | 9.97 ± 1.06 bBC | 36.24 ± 4.46 aA | 1.60 ± 2.10 aA | 9.59 ± 4.54 aA | 10.52 ± 4.33 aA | 15.77 ± 3.96 aAB | 2.5 ± 0.8 bcBC | 58.52 ± 8.33 aA | |

| 25 | 5.80 ± 0.19 cBCD | 106.76 ± 40.30 aA | 25.20 ± 0.96 aA | 15.17 ± 2.90 aA | 33.94 ± 3.60 aA | 2.91 ± 0.62 aA | 7.81 ± 5.63 aA | 8.87 ± 5.34 aA | 19.25 ± 5.67 aAB | 1.7 ± 0.1 cC | 49.15 ± 7.47 aA |

Control and freshness paper fruits showed the presence of mold growth on the fruit skin after day 15, hence, they were not analyzed after day 15.

Means for the parameters in each treatment that do not share a superscript are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Lowercase superscripts represent statistical differences within treatment groups for the respective treatments and uppercase superscripts represent statistical differences between all treatment groups at p ≤ 0.05.

Comparing all the data obtained between the treatment groups (e.g., control day 0, 1% chitosan day 5, 2% chitosan day 10, etc) for the respective cultivars, it is evident that the pH and titratable acidity values obtained for the Susquehanna and 10–35 fruits were not statistically different as can be seen from the ANOVA analyses shown by the uppercase superscripts in Table 1, Table 3 respectively. However, the Sunflower fruits showed some statistical differences in the pH and titratable acidity (Table 2) while the Mixed fruits showed some statistical differences in only the pH values across the treatment-day combination (Table 4), although these most of the pH and titratable acidity values obtained were statistically similar.

3.2. Total soluble solids

Total soluble solids content is an important parameter in assessing fruit quality. It is a measure of the quantity of dissolved sugars and other water-soluble molecules that are present in fruit pulp. Generally, as fruits are stored over time, their total soluble solids contents increase because complex carbohydrates like pectin, cellulose, and hemicellulose from cell walls in the fruit cells breakdown into simple sugars (Islam et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2021). Also, the change in total soluble solids content of fruits during storage could be caused by a reduction in respiration rate and an enhancement in dry matter due to moisture loss (Khorram et al., 2017).

The results from this study show that overall, there were no significant differences in the total soluble solids of the pawpaw fruits from all the cultivars and the different treatments (including control groups) during the storage period (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4). This is also shown in the ANOVA analyses comparing all the treatment-day combinations for all the cultivars shown by the uppercase superscripts. This is different from the observation Archbold et al. (2003) made that during storage there is about a 20% increase in the total soluble solids content of pawpaw fruits. From the results, it is unclear whether the treatments had any significant effect on the total soluble solids content of the fruits during storage. The total soluble solids content of the fruits in all the Susquehanna treatments in this study was similar to the value (28.0 °Brix) reported by Brannan (2016) for the cultivar. That of the Sunflower fruits in all the treatments were also within the range of total soluble solids content in Sunflower fruits (16.0–20.0 °Brix) studied by Brannan (2016) and Lolletti et al. (2021), and the values obtained for the fruits of the 10–35 cultivar throughout the storage period were higher compared to the total soluble solids content (14.64 ± 2.32 °Brix) reported for the cultivar by Adainoo et al. (2022).

In all the Susquehanna treatments, Sunflower chitosan treatments, 10–35 control and 10–35 2% chitosan and Mixed fruit control treatments, it was noted that the total soluble solids contents on the last day were slightly lower than the total soluble solids content on day 0. This may have been caused by the formation of alcohol during fermentation of the sugars in the pulp. However, studies have shown that the mean activity of alcohol dehydrogenase (an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of sugars into alcohols during fruit ripening and aroma volatile formation) in pawpaw fruit does not change after harvest or during cold storage (Galli et al., 2008). Hence, it is unlikely that there was a significant alcohol production in the fruit even though the fruit it known to continue to ripen to the point of fermentation during storage after harvest. It is still crucial for future studies to analyze the fruit pulp for alcohol formation during storage to test this hypothesis. There is also the possibility that the slight reduction in total soluble solids could be due to the complexing of simple sugars to form stringy vascular tissue that make the pulp of some of the fruits stringy during storage as was observed during the experiments on the last day for some of the fruits. This phenomenon is a physiological disorder which is accompanied by a decrease in total soluble solids that has been observed in avocadoes when they are stored for 4–6 weeks; it can be reduced by treating fruits with 1-methylcyclopropene, a plant growth regulator that inhibits ethylene action in plant cells (Choque-Quispe et al., 2022; Woolf et al., 2005). These findings provide the opportunity for further studies into the simple sugar and polysaccharide profile of the pawpaw fruit pulp during storage as this will help to optimize the storage conditions for the best pawpaw fruit quality when they are stored over a period.

3.3. Moisture loss

Fruits continue to respire after harvesting, taking in oxygen from the surrounding atmosphere, and releasing carbon dioxide and water in the process. This exchange of gases during fruit respiration results in loss of moisture from the fruits over time leading to a decrease in fruit weight and changes in the physical appearance and textural properties of the fruit as more moisture is lost. Studies have shown that relative humidity has a greater influence on moisture loss than storage temperature with fruits losing more moisture when they are stored at higher relative humidity (Lufu et al., 2019). Further, larger fruits are typically expected to lose less moisture over time compared to smaller fruits because the smaller fruits have a higher surface area to volume ratio. Because of this, smaller apples and eggplants lose weight faster than larger ones, and the neck area of a pear loses weight faster than the bottom part of the fruit (Lufu et al., 2020). Many other factors also affect the rate of moisture loss in fruits during postharvest storage including cultivar, orchard practices, fruit peel thickness, weather conditions, harvesting techniques and mechanical injuries, airflow during storage, and packaging (Lufu et al., 2020).

The data obtained show that for the Susquehanna fruits, the chitosan coatings successfully controlled the loss of moisture in the fruits compared to the control fruits as shown by the ANOVA analyses within the treatment groups and between the treatment groups. By day 5, the control fruits had already lost 7.20 ± 0.52% moisture meanwhile the 1% chitosan (6.94 ± 0.86%) and 2% chitosan (6.86 ± 0.79%) fruits lost similar amounts by day 25 (Table 1). Similarly, the chitosan coatings were effective in controlling moisture loss in Sunflower fruits as can be seen from the ANOVA analyses within the treatment groups and between the treatment groups in Table 2. The control Sunflower fruits had lost 7.39 ± 1.35% moisture by day 15, but by day 25, the 1% chitosan coated fruits had lost only 3.97 ± 0.23% and the 2% chitosan coated fruits had lost 3.70 ± 0.62% (Table 2). This further indicates that for the Sunflower fruits, the 2% chitosan coating better controlled moisture loss than the 1% chitosan coating. For the 10–35 fruits, although the control fruits had averagely lost more moisture by day 25 the variation in moisture loss of the control fruits makes the moisture loss in the control fruits similar to the moisture loss in the chitosan coated fruits, meaning the chitosan coatings did not significantly affect moisture loss in 10–35 fruits compared to the control fruits as can be seen from the ANOVA analyses within the treatment groups and between the treatment groups (Table 3).

The fruits in the mixed fruit group lost more moisture during the storage period compared to the moisture lost by the fruits in the respective cultivar groups. Nonetheless, the data show that mixed fruits with the freshness paper treatment (6.01 ± 1.61%) lost less moisture within the 15-day period of storage than the control fruits (9.99 ± 0.90%) before both groups had visible mold growths on the skin of the fruits (Table 4). From the one-way ANOVA within the treatment groups (the lowercase superscripts by the values in the tables), it is evident that for the freshness paper treatment, there were relatively fewer changes in the moisture loss over time compared to the sodium alginate coated fruits. This suggests that the sodium alginate coatings were not very effective in controlling the loss of moisture from the fruits during storage. This may have been due to the hydrophilicity of alginate and the fact that the water vapor permeability of alginate films (390 g⋅m−1⋅s−1Pa−1) is higher than that of chitosan films (360 g⋅m−1⋅s−1Pa−1) (ALSamman & Sánchez, 2022; Vargas et al., 2008). Further, the low concentration of alginate used in the experiments than what has been used in other literature could account for the higher moisture loss. However, in the pre-experiment trials, 1% alginate and 2% alginate coatings were tested but these coatings did not adhere to the fruit well after drying, which is why lower concentrations (0.001% and 0.005%) which adhered to the fruits were used in this study.

The fruits in the mixed fruit group lost more moisture during the storage period compared to the moisture lost by the fruits in the respective cultivar groups. Nonetheless, the data show that mixed fruits with the freshness paper treatment (6.01 ± 1.61%) lost less moisture within the 15-day period of storage than the control fruits (9.99 ± 0.90%) before both groups had visible mold growths on the skin of the fruits (Table 4). From the one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test (the superscripts by the values in the tables), it is evident that freshness paper treatment there was relatively fewer changes in the moisture loss over time compared to the sodium alginate coated fruits. This suggests that the sodium alginate coatings were not very effective in controlling the loss of moisture from the fruits during storage. Studies have shown that although polysaccharide-based (e.g. alginate) edible coatings offer good barrier properties, they are hydrophilic with a high-water vapor permeability (Vargas et al., 2008). This may have accounted for the high moisture loss in the alginate coated fruits. Also, the hydrophilicity of alginate and the fact that the water vapor permeability of alginate films (390 g⋅m−1⋅s−1Pa−1) is higher than that of chitosan films (360 g⋅m−1⋅s−1⋅Pa−1) could explain why the alginate coated fruits lost more moisture over time than the chitosan coated fruits (ALSamman & Sánchez, 2022; Vargas et al., 2008). Further, the low concentration of alginate used in the experiments compared with levels used in other literature could account for the higher moisture loss. However, in the pre-experiment trials, 0.5% alginate, 1% alginate and 2% alginate coatings were tested but these coatings did not adhere to the fruit well after drying, which is why lower concentrations (0.001% and 0.005%) which adhered to the fruits were used in this study.

Moisture loss in fruits occurs by the loss of moisture from the peel which is continuously replenished by migration of moisture from the pulp (Singh and Reddy, 2006). Based on this, it is expected that fruits with thicker peels lose less moisture compared to those with thinner peels since moisture can migrate across thinner peels easily and more rapidly. Also, with the added edible coating, it is expected that the edible coating will increase the barrier moisture has to travel across to leave the fruit, thereby slowing moisture loss. Previous studies have found that Susquehanna fruit have a peel thickness of 0.51 ± 0.18 mm, Sunflower fruits have a peel thickness of 0.34 ± 14 mm and 10–35 fruits have a peel thickness of 0.38 ± 0.18 mm (Adainoo et al., 2022). However, these peel thickness values do not correspond to the percent moisture loss for these cultivars. Other factors such as airflow during storage may have had a more significant effect on the percent moisture loss from the Susquehanna, Sunflower and 10–35 fruits than their respective peel thickness.

3.4. Skin color and physical appearance

One of the main challenges that has made commercializing the North American pawpaw difficult has been the rapid color change that occurs in the skin of the fruit during postharvest storage. It is therefore critical that technologies aimed at extending the shelf life of the fruits also control the change of the skin color over time, since the skin color is an important indicator of pawpaw fruit quality. One of the key color parameters for monitoring the changes in skin color is the ΔE value. According to Bhookya et al. (2020), ΔE values greater or equal to 2 can be detected by the human eye, but ΔE values less than 0.3 cannot be detected by the human eye.

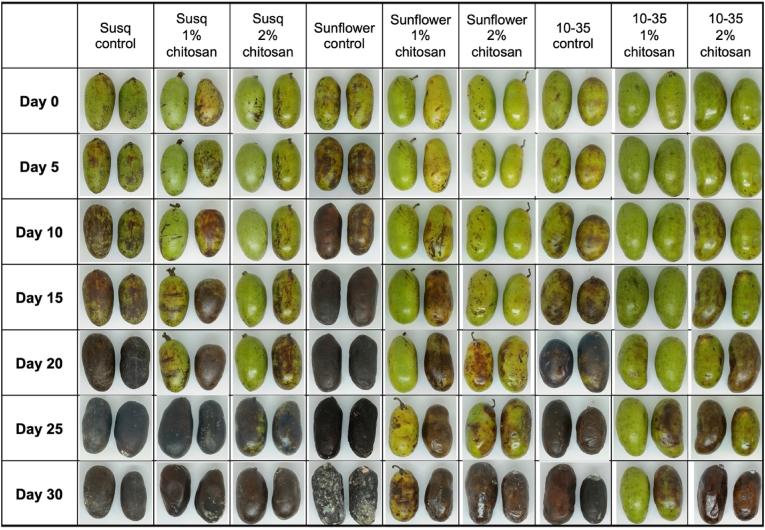

Data obtained from the experiments show that for the Susquehanna control fruits, there were significant differences in the color parameters (L*, a*, b*, chroma and ΔE) (p < 0.05), however, the 1% chitosan and 2% chitosan coatings were effective in controlling the change of the skin color with no statistically significant variation in L*, a*, b*, chroma and ΔE values during the 25-day storage period (Table 1). Although from Fig. 1, it can be seen that the Susquehanna 1% and 2% chitosan fruits were darker in skin color on day 25 compared to their skin color on day 0. Further, there was a similar observation in the Sunflower fruits. The Sunflower control fruits showed statistically significant (p < 0.0001) changes in skin color parameters, but the chitosan coated fruits showed no statistically significant (p > 0.05) changes in skin color parameters over the storage duration (Table 2) except for the ΔE values of the Sunflower 1% chitosan fruits that had some statistically significant (p = 0.018) changes during the storage. Like the other cultivars, the 10–35 control fruits had statistically significant (p < 0.0001) changes in color parameters during the storage. The 10–35 1% chitosan fruits had no statistically significant (p > 0.05) changes in color parameters over time except for the a* values and ΔE values which changed significantly (p < 0.05) (Table 3). The 10–35 2% chitosan fruits had statistically significant changes in color parameters throughout the storage (p < 0.05). The Mixed control and freshness paper fruits had no statistically significant changes in all the color parameters except the ΔE values, which changed significantly (p < 0.01) during storage (Table 4). The 0.001% alginate was effective in controlling changes in only the b*, chroma, and ΔE values but the 0.005% alginate coating effectively controlled the changes in all the color parameters (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Images showing the physical appearance of pawpaw fruit samples for the Susquehanna, Sunflower and 10–35 cultivars and their chitosan treatments during storage. (Susq = Susquehanna).

Both 1% chitosan and 2% chitosan coatings were able to delay the molding of the fruits, which occurred after day 15 for the control Susquehanna, control Sunflower, control mixed, and freshness paper-treated fruits. This may be attributed to chitosan's natural antifungal and antimicrobial properties, which are also dependent on factors such as molecular weight, the influence of the fruit on which it is applied, and the components of the chitosan coating solution (Devlieghere et al., 2004; Zheng and Zhu, 2003). In lettuce, the antimicrobial effect of chitosan disappears after 4 days of storage, meanwhile, in strawberries, it takes 12 days for the antimicrobial effect of chitosan to disappear (Devlieghere et al., 2004). In this study, while microbiological tests were not performed on the coatings, there were physical observations of mold growth on the skin of the chitosan-coated fruits after day 25 as can be seen in Fig. 1. From this, it could be said that the antimicrobial effect of chitosan disappeared after day 25. Future studies could further explore how interactions with the pawpaw fruit affect chitosan's antimicrobial activity. Despite these findings, the 10–35 control fruits had no physical observations of mold growth throughout the storage period, which may be due to a genetic trait of the cultivar that enables it to resist mold growth for a period.

3.5. Textural properties

The North American pawpaw fruit is known to be a climacteric fruit which continues to ripen postharvest to the point where it is too soft to handle, suggesting that its cohesiveness ratio (the strength of the internal bonds of the fruit) reduces as it ripens. This is one of the reasons why it has remained challenging for the fruit to be marketed since these changes in textural properties all happen within 5 days after harvest (Archbold et al., 2003; Galli et al., 2008). In addition, pawpaw ripeness is typically determined by the hardness (or firmness) of the fruit. These make the textural properties; hardness and cohesiveness ratio, crucial for determining fruit quality. According to Archbold et al. (2003), pawpaw fruits can be stored at 4 °C for 1 month with little change in firmness, however, in cherimoya fruits (another fruit in the Annonaceae family), it was found that storage at temperatures below 7 °C resulted in chilling injury, which affects textural properties.

Among the Susquehanna fruit treatments, the 1% chitosan coating better controlled the change in hardness of the fruits than the 2% chitosan coating, although in both chitosan treatments there was a reduction in hardness with time (Table 1). For all the Susquehanna fruits, it was found that the cohesiveness ratio increased with time (Table 1). For the Sunflower fruits, there were statistically significant changes in the hardness and cohesiveness ratio of fruits in both 1% and 2% chitosan coating treatments (Table 2). The 10–35 fruits, like the Susquehanna fruits, had no statistically significant change in hardness throughout the storage period, even though there was a decrease in hardness (Table 3). Among the 10–35 fruit treatments, 1% chitosan coating was more effective in controlling the change in cohesiveness ratio during storage than the 2% chitosan coating. The mixed fruits showed no statistically significant change in both hardness and cohesiveness ratio throughout the storage period, except for the 0.005% alginate coated fruits which showed some variations in hardness during storage (Table 4).

Overall, the hardness of the fruits reduced, and the cohesiveness ratio increased with time. The increase in may have resulted from the loss of moisture which increased the strength of the internal bonds within the fruits.

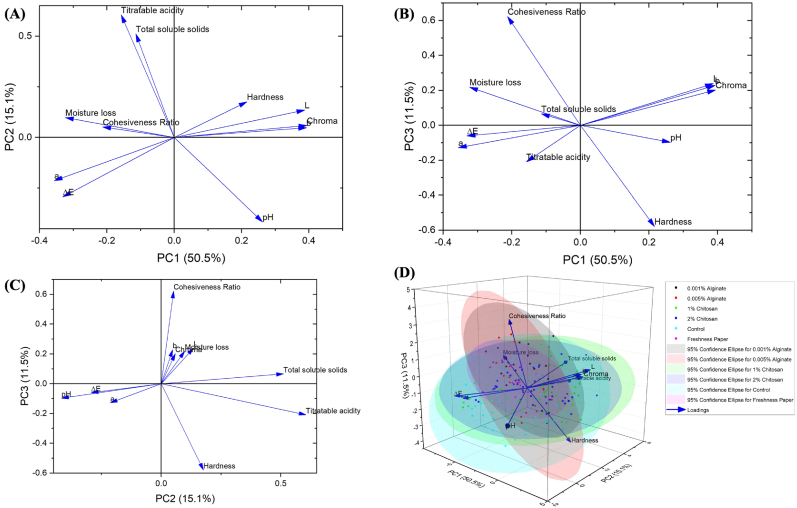

3.6. Principal component analysis of variability

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a multivariate analysis technique that helps to reduce the dimensionality of the data matrix, provide insights into the relationship between the quality characteristics studied, highlight the differences between the quality characteristics of pawpaw fruits, and enable the visualization of the multidimensional data. In this study, PCA was also performed to identify clusters among the different treatments studied based on their similarities. According to Boateng et al. (2021), a total variance of 70–90% is desirable to explain the variability in a principal component analysis. The results show that the rate of variance contribution of the first, second and third PCs were 50.5%, 15.1% and 11.5% respectively. The total rate of variance contribution of the first three PCs was 77.1%. Hence, the first three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) are enough to explain most of the total variance of the pH, titratable acidity, total soluble solids, moisture loss, color parameters (L*, a*, b*, chroma and ΔE), and textural properties (hardness and cohesiveness ratio) can be explained by the first three PCs.

Based on the extracted eigenvectors, PC1 was contributed to by a* values (−0.356), ΔE (−0.331), moisture loss (−0.323), L* values (0.388), b* values (0.393) and chroma (0.394); PC2 was contributed to by pH (−0.417), total soluble solids (0.511), and titratable acidity (0.605); and PC3 was contributed to by hardness (−0.579), and cohesiveness (0.623). From the PCA loading plots (Fig. 2A–C), it is evident that based on the data obtained in this study, there are some correlations between some of the quality parameters analyzed. Fig. 2A shows that there are significant correlations between moisture and cohesiveness ratio, and titratable acidity and total soluble solids, although these correlations are weak as can be seen from the Pearson's correlation coefficients in Table 5. Further, there are significant correlations between b* value and chroma, and a* and ΔE values as can be seen Fig. 2A and B. The biplot (Fig. 2D) shows that comparing all the controls and the treatments, there were similarities in the effect of the treatments studied. This is shown in the overlap of the 95% confidence ellipses for the treatments. Pooling all the data together, beyond the correlations, PCA shows that there is no clear separation in the effect of the chitosan, alginate, and freshness paper treatments from the control groups based on the quality characteristics studied.

Fig. 2.

2D loading plots (A-C) and 3D biplot (D) from the principal component analysis of the quality characteristics of the pawpaw fruits during storage.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix of Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) for the quality characteristics of the pawpaw fruits.

| pH | Titratable acidity | Total soluble solids | Moisture loss | L* | a* | b* | Chroma | ΔE | Hardness | Cohesiveness Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 1.00 | −0.64 | −0.29 | −0.50 | 0.41 | −0.30 | 0.48 | 0.46 | −0.36 | 0.31 | −0.34 |

| Titratable acidity | −0.64 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.32 | −0.26 | 0.07 | −0.33 | −0.32 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Total soluble solids | −0.29 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.25 | −0.13 | 0.17 | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.25 |

| Moisture loss | −0.50 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 1.00 | −0.59 | 0.51 | −0.60 | −0.62 | 0.53 | −0.45 | 0.48 |

| L | 0.41 | −0.26 | −0.13 | −0.59 | 1.00 | −0.85 | 0.94 | 0.93 | −0.73 | 0.33 | −0.28 |

| a | −0.30 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.51 | −0.85 | 1.00 | −0.80 | −0.80 | 0.72 | −0.32 | 0.37 |

| b | 0.48 | −0.33 | −0.21 | −0.60 | 0.94 | −0.80 | 1.00 | 0.95 | −0.70 | 0.32 | −0.31 |

| Chroma | 0.46 | −0.32 | −0.21 | −0.62 | 0.93 | −0.80 | 0.95 | 1.00 | −0.70 | 0.34 | −0.33 |

| ΔE | −0.36 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.53 | −0.73 | 0.72 | −0.70 | −0.70 | 1.00 | −0.46 | 0.24 |

| Hardness | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.45 | 0.33 | −0.32 | 0.32 | 0.34 | −0.46 | 1.00 | −0.50 |

| Cohesiveness Ratio | −0.34 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.48 | −0.28 | 0.37 | −0.31 | −0.33 | 0.24 | −0.50 | 1.00 |

3.7. Ranking the treatments using the TOPSIS-Shannon entropy method

In order to further test which treatment performed best for the respective cultivar groups, TOPSIS-Shannon entropy method was employed. TOPSIS (technique for ordered preference by similarity to ideal solution) is a multicriteria decision making analysis that ranks the alternatives based on their distance from the ideal solution (Khodaei et al., 2021).

In this study, the mean of each of the quality parameters analyzed were selected as important criteria in assessing the quality of the fruits during the storage period. Total soluble solids, pH, L* values, b* values, chroma, hardness and cohesiveness ratio were considered as the positive criteria since higher values are preferred for these quality characteristics while titratable acidity, moisture loss, a* values and ΔE values were considered as the negative criteria since lower values are preferred for these quality characteristics. The data were normalized and the weight for each of these criteria were determined by the Shannon entropy method (Table 6). The a* values had the highest influence (0.6533) on the quality of the pawpaw fruits during storage while pH had the least influence (0.0009) on the quality of the pawpaw fruits during storage.

Table 6.

Criteria and suggested weights for each response by Shannon entropy method.

| Criteria | Weight |

|---|---|

| a* | 0.6533 |

| Moisture loss | 0.1073 |

| Titratable Acidity | 0.0615 |

| b* | 0.0528 |

| Chroma | 0.0499 |

| ΔE | 0.0386 |

| Cohesiveness ratio | 0.0165 |

| L* | 0.0078 |

| Hardness | 0.0069 |

| Total soluble solids | 0.0046 |

| pH | 0.0009 |

The performance of the treatments for the respective cultivar groups were determined using their distances from the ideal (Si+) and negative points (Si−) as shown in Table 7. From this, the treatments were ranked based on their performance scores, and it was found that for 10–35 fruits, 1% chitosan coating performed better than the 2% chitosan coating, which performed better for Susquehanna and Sunflower fruits. The effect of the 1% chitosan coating on the 10–35 fruits can even be seen in the physical appearance of the fruits as shown in Fig. 1. Apparently, the 10–35 1% chitosan coated fruits had a more controlled physical appearance than the fruits in the other treatment groups. This was followed by the Sunflower 2% chitosan and Susquehanna 2% chitosan fruits. These findings further indicate that chitosan coatings are effective for controlling changes in quality of pawpaw fruits possibly because of how chitosan strongly alters carbon metabolism in the fruits thereby positively influencing the quality characteristics of during storage (Cosme Silva et al., 2017). As expected, the control fruits performed worse than the chitosan coated fruits except for the Susquehanna 1% chitosan coated fruits. Also, comparing the freshness paper treated fruits to the other treatments, it is evident that overall the freshness paper treatment did not perform well in maintaining the quality and its performance was worse than the Mixed control fruits but slightly better than the Sunflower control fruits. In addition, the alginate coated fruits performed the worst compared to all the treatments, which may be due to the low concentration of alginate used in the coating solutions. Also, the complex effect of the differences in the metabolic processes of the fruits from different cultivars used for the alginate coating experiments could have had an impact on the effectiveness of the alginate coatings. In the future, improved alginate coating formulations could be tested on fruits from specific pawpaw cultivars to confirm their effect on the quality characteristics of pawpaw fruits during storage.

Table 7.

Final rankings of the treatments on improving the shelf-life of North American pawpaw fruits obtained by TOPSIS analyses.

| Cultivar | Treatment | Si+ | Si− | Si+ + Si− | Pi | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–35 | 1% Chitosan | 0.010 | 0.437 | 0.447 | 0.978 | 1 |

| Susquehanna | 2% Chitosan | 0.172 | 0.267 | 0.439 | 0.609 | 2 |

| Sunflower | 2% Chitosan | 0.172 | 0.267 | 0.439 | 0.609 | 2 |

| 10–35 | 2% Chitosan | 0.212 | 0.226 | 0.438 | 0.517 | 4 |

| Sunflower | 1% Chitosan | 0.255 | 0.186 | 0.440 | 0.422 | 5 |

| Susquehanna | Control | 0.275 | 0.163 | 0.438 | 0.372 | 6 |

| Susquehanna | 1% Chitosan | 0.325 | 0.113 | 0.438 | 0.258 | 7 |

| 10–35 | Control | 0.385 | 0.058 | 0.443 | 0.132 | 8 |

| Mixed | Control | 0.391 | 0.051 | 0.442 | 0.116 | 9 |

| Mixed | Freshness Paper | 0.435 | 0.033 | 0.469 | 0.071 | 10 |

| Sunflower | Control | 0.422 | 0.024 | 0.446 | 0.054 | 11 |

| Mixed | 0.001% Alginate | 0.423 | 0.020 | 0.442 | 0.044 | 12 |

| Mixed | 0.005% Alginate | 0.430 | 0.016 | 0.446 | 0.036 | 13 |

4. Conclusion

The findings from this study show that edible coatings have effects on the quality characteristics of pawpaw fruits during storage. However, the effect of the edible coatings varied for different quality characteristics during the storage period. Freshness paper treatment also had some effect on the quality of pawpaw fruits during storage. The chitosan coatings were more effective in slowing moisture loss in Sunflower than in Susquehanna and 10–35 fruits, and the freshness paper treatment better controlled moisture loss than the alginate coatings. Although the treatments generally controlled the change in pH, acidity, and total soluble solids, there were variations in some color parameters as well as textural properties over time. Further, the chitosan and alginate coatings delayed mold growth on the skin of the pawpaw fruits during the storage period. The TOPSIS analyses revealed that 1% chitosan coatings are effective in maintaining the quality of 10–35 pawpaw fruits while 2% chitosan is better for Sunflower and Susquehanna pawpaw fruits. To our knowledge, this is the first scientific study conducted to investigate the effects of edible coating on extending the shelf-life of pawpaw fruit. The experimental data from different cultivars, treatments, and storage conditions, proved the shelf-life of pawpaw fruit could be extended from 5 days to 15–20 days depending on the cultivar. These findings have a greater significance from a food processing standpoint and can help in the selection and use of whole pawpaw or pawpaw as a food ingredient for different food applications. Also this will pave the way for whole pawpaw fruits with longer shelf lives to be commercialized, creating new markets for this underutilized specialty crop.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry and the USDA/ARS Dale Bumpers Small Farm Research Center, Agreement number 58-6020-0-007 from the USDA Agricultural Research Service. This work is supported by the Food Engineering and Sustainable Technologies (FEAST) lab through USDA Hatch Funds (MO-HAFE0003).

Handling editor: Dr. Xing Chen

Contributor Information

Bezalel Adainoo, Email: adainoo@gmail.com.

Andrew L. Thomas, Email: thomasal@missouri.edu.

Kiruba Krishnaswamy, Email: krishnaswamyk@missouri.edu.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Adainoo B., Crowell B., Thomas A.L., Lin C.-H., Cai Z., Byers P., Gold M., Krishnaswamy K. Physical characterization of frozen fruits from eight cultivars of the North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) Front. Nutr. 2022;9:2393. doi: 10.3389/FNUT.2022.936192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adainoo B., Thomas A.L., Krishnaswamy K. Correlations between color, textural properties and ripening of the North American pawpaw (Asimina triloba) fruit. Sustainable Food Technology. 2023;1(2):263–274. doi: 10.1039/D2FB00008C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alharaty G., Ramaswamy H.S. The effect of sodium alginate-calcium chloride coating on the quality parameters and shelf life of strawberry cut fruits. Journal of Composites Science. 2020;4(3):123. doi: 10.3390/JCS4030123. 2020. Page 123, 4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alsamman M.M., Sánchez J. Chitosan- and alginate-based hydrogels for the adsorption of anionic and cationic dyes from water. Polymers. 2022;14(8):1498. doi: 10.3390/POLYM14081498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansarifar E., Shahidi F., Mohebbi M., Razavi S.M., Ansarifar J. A new technique to evaluate the effect of chitosan on properties of deep-fried Kurdish cheese nuggets by TOPSIS. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. (Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft -Technol.) 2015;62(2):1211–1219. doi: 10.1016/J.LWT.2015.01.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . seventeenth ed. AOAC International; 2000. Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists International. [Google Scholar]

- Archbold D.D., Koslanund R., Pomper K.W. Ripening and postharvest storage of pawpaw. HortTechnology. 2003;13(3):439–441. doi: 10.21273/HORTTECH.13.3.0439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon H., Granit R., Porat R., Poverenov E. Development of polysaccharides-based edible coatings for citrus fruits: a layer-by-layer approach. Food Chem. 2015;166:465–472. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2014.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataei S., Azari P., Hassan A., Pingguan-Murphy B., Yahya R., Muhamad F. Essential oils-loaded Electrospun Biopolymers: a future Perspective for active food packaging. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2020;2020:1–21. doi: 10.1155/2020/9040535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Silva W., Nascimento V.L., Medeiros D.B., Nunes-Nesi A., Ribeiro D.M., Zsögön A., Araújo W.L. Modifications in organic acid profiles during fruit development and ripening: correlation or causation? Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9(1689) doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2018.01689/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhookya N.N., Malmathanraj R., Palanisamy P. Yield estimation of chili crop using image processing techniques. 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS) 2020:200–204. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=9074257 [Google Scholar]