Abstract

Half of hospice family caregivers report having unmet information needs, which can contribute to poor pain and symptom management, emergency department use, and hospice disenrollment for care-recipients and to caregiver strain and stress. Effective communication between hospice teams and family caregivers is critical yet communication inadequacies persist. Despite the growing prevalence of distance caregiving, including in hospice care, and the relationship between caregiver proximity and communication effectiveness, little is known about how caregiver proximity is associated with caregiver perceptions of hospice communication. In this secondary analysis of quantitative data from two multisite randomized clinical trials (NCT03712410 and NCT02929108) for hospice family caregivers (N=525), multivariate linear models with demographic and contextual controls were used to analyze caregivers’ perceptions of caregiver-centered communication with hospice providers based on caregiver proximity to the hospice care-recipient. In multivariate models, “local” hospice family caregivers who lived within 1 hour of the hospice care-recipient reported less effective communication with the hospice team than co-residing caregivers; and older caregivers rated communication more favorably than younger caregivers. To improve communication and collaboration between hospice teams and caregivers, regardless of proximity, distance communication training for hospice teams and interventions such as telehealth communication and virtual tools that enable triadic collaboration are recommended. Research is needed to understand why local caregivers, specifically, perceive communication quality less favorably and how hospice teams can better meet local and distance caregiver communication needs.

Introduction

For over 1.2 million hospice family caregivers in the United States (Weber-Raley & Haggerty, 2020; Wolff et al., 2020), effective communication with hospice clinicians and staff is critical to patients receiving high quality end-of-life care and to family caregivers experiencing high quality supportive care during caregiving and through bereavement (Cagle & Kovacs, 2011; Ragan, 2016; Washington et al., 2019). In hospice, care is provided to both patients and caregivers, with communication being triadic between a patient, a clinical team, and the patient’s caregivers (Reblin et al., 2017; Washington et al., 2019), the majority of whom are family members (Starr et al., 2021; Starr et al., 2022). Timely, clear, emotionally- and culturally-sensitive communication about illness progression, patient care, medication and symptom management, crisis situations, and coping is needed to prepare and equip caregivers for end-of-life caregiving (Hughes et al., 2019; Hwang et al., 2014; Luth et al., 2021; Waldrop et al., 2012). Good communication also supports caregiver quality of life (Tamayo et al., 2010) and satisfaction with hospice care (York et al., 2012).

Improved communication about hospice is needed (Candrian et al., 2018; Chi & Demiris, 2017; Chi et al., 2018 Apr-Sep; Quigley & McCleskey, 2021; Scholz et al., 2020). Because 60% of patients and family members have little to no knowledge of hospice when they are referred to hospice (Casarett et al., 2005), many patients and family caregivers begin hospice care without a good understanding of its scope of services, benefits, and limitations or what is expected of family caregivers (Cagle et al., 2016; Candrian et al., 2018; Lee & Cagle, 2017). In addition, caregivers have varying levels of health literacy (Fields et al., 2018; Wittenberg et al., 2019), the ability to understand and use health information to inform health-related decisions. Low health literacy challenges caregivers’ ability to communicate with hospice clinicians and navigate services and supports (Fields et al., 2018). As such, misperceptions and misinformed expectations about hospice care are common (Shalev et al., 2018).

About half of hospice family caregivers report having unmet information needs (Shalev et al., 2019). Inadequate understanding can contribute to poor pain and symptom management (Chi & Demiris, 2017; Chi et al, 2018; Oliver et al., 2013), emergency room use and disenrollment from hospice (Phongtankuel et al., 2017; Phongtankuel et al., 2016), and distress or strain for caregivers (Luth et al., 2021; Wittenberg et al., 2021). Feeling overwhelmed and unprepared for caregiving, hospice family caregivers cite communication within the health system as a challenge (Oliver et al., 2017). Qualitative research shows hospice family caregivers value hospice clinicians who educate and share information in engaging ways that build trust and invite caregivers into the process of care, recognizing the primary role and expertise of family caregivers (Cloyes et al., 2014).

Communication, however, depends on both clinicians and caregivers. A recent study found, for example, that caregivers who avoided discussing caregiving topics reported higher anxiety and lower quality of life (Wittenberg et al., 2021) while caregivers who avoid discussing death or experience poor communication while caregiving are more likely to experience pre-loss grief symptoms (Nielsen et al., 2017; Wittenberg et al., 2017). Caregivers with higher communication self-efficacy have reported higher quality of life, lower burden, and better mental health status (Tatsumi et al., 2016; Wittenberg et al., 2021), suggesting caregivers with lower communication self-efficacy require proactive communication by care teams. In addition, a caregiver’s own mental and physical health may affect and be affected by healthcare communication experiences (Chen et al., 2018; Okunrintemi et al., 2017). Positive perceptions of healthcare communication, for example, are associated with positive physical health outcomes (Okunrintemi et al., 2017), whereas poor communication is associated with worse mental and physical health (Chen et al., 2018).

Distance caregiving.

The distance a hospice family caregiver lives from a care-recipient (and the effort involved in overcoming distance) can also affect communication about a person’s illness and care needs, and caregiver support and satisfaction (Bevan & Sparks, 2011; Cagle & Munn, 2012; Falzarano et al., 2020; Fischer & Jobst, 2020; Mazanec et al., 2011). Distance caregiving occurs when family or friends provide unpaid care from a proximity that restricts communication opportunities due to geographic parameters (Bevan & Sparks, 2011). Studies show 41% to 60% of hospice family caregivers do not live in the same residence as the hospice patient for whom they’re caring (Oliver, Demiris, et al., 2017; Oliver, Washington, et al., 2017; Starr et al., 2021; Starr et al., 2022). Distance caregiving is a growing phenomenon, with an estimated 4.6 million U.S. adults providing informal, unpaid care to an older adult who lives an hour or more away (Weber-Raley & Haggerty, 2020). Geographic distance does not reduce family members’ concern for each other nor does it necessarily correspond with the level of care a person provides (Bevan & Sparks, 2011; Cagle & Munn, 2012), but distance often impedes information flow and reduces interaction frequency and face-to-face communication with clinical teams (Bevan & Sparks, 2011; Franke et al., 2019; Stafford, 2005; Zentgraf et al., 2019). In part due to an inability to attend clinician visits in person, caregivers who live away from care-recipients report difficulty accessing up to date, reliable information about patient and care needs, limiting a caregiver’s ability to react to needs in crisis situations (Cagle & Munn, 2012; Franke et al., 2019; Zentgraf et al., 2019). The communication and care limitations contribute to caregiver feelings of anxiety, guilt, and being excluded from care decision-making (Bevan & Sparks, 2011; Douglas et al., 2016; National Alliance for Caregiving, 2004). In one study, for example, over half of caregivers who lived more than 50 miles away reported feelings of helplessness and anxiety and 80% reported strain caused by living away from the patient (Schoonover et al., 1988).

Caregiver-centered communication.

Despite the prominent role hospice family caregivers play in managing care and communicating with hospice staff (Ellington, Clayton, et al., 2018), limited attention has been given to assessing communication between family members and healthcare teams (Epstein & Street, 2007). Research suggests family caregivers need healthcare communication that is person-centered: genuine, attentive, sensitive to unmet information needs, focused on care-recipient and caregiver experiences, and responsive to different communication preferences of care-recipients and caregivers (Washington et al., 2019). Informed by evidence that person-centered communication benefits patients (Kwame & Petrucka, 2021; McCormack et al., 2011), there is a growing movement to promote caregiver-centered communication, defined as communication that addresses caregivers’ needs, beliefs, preferences, and perspectives; involves caregivers in decision-making; and helps caregivers navigate healthcare systems (Demiris et al., 2020). Addressing the myriad communication challenges family caregivers face is essential in hospice care (Washington et al., 2022; Wittenberg et al., 2017).

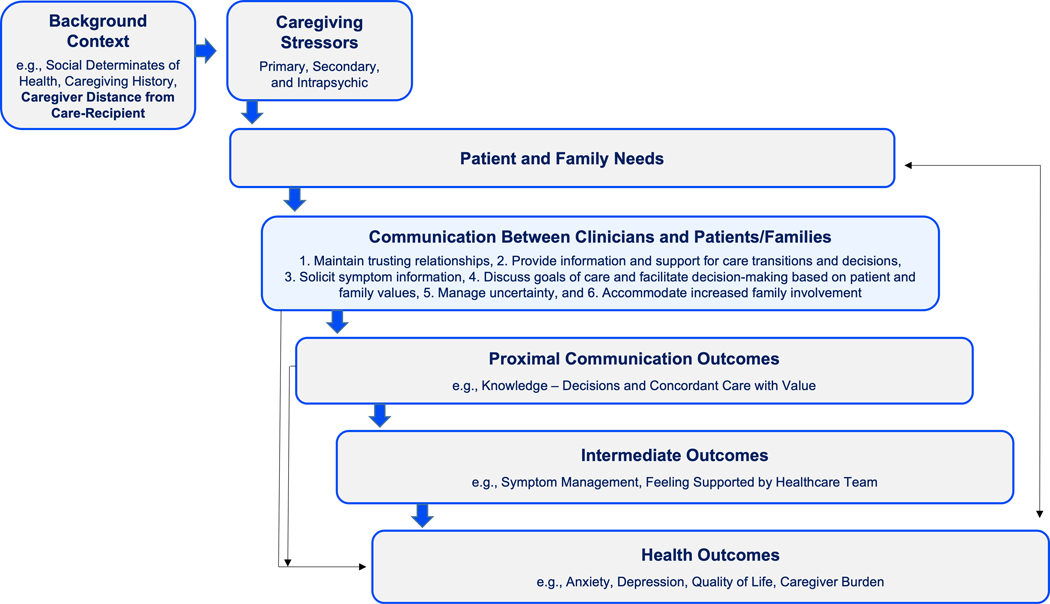

The Caregiver-Centered Communication model (Figure 1) illustrates the concept of caregiver-centered communication. Integrating processes, interactions, and outcomes from Epstein and Street’s National Cancer Institute patient-centered communication monograph and the role of proliferating caregiving stressors in Pearlin and colleagues’ Stress Process Model (Demiris et al., 2009; Epstein & Street, 2007; Pearlin et al., 1990; Washington et al., 2019), our model recognizes that caregiving and illness trajectories are inherently linked and that unique communication needs emerge across trajectories, especially at end-of-life. Consistent with Pearlin and colleagues’ model, background and contextual factors (e.g., social determinants of health, caregiving history, distance a caregiver lives from a care-recipient) affect primary, secondary, and intrapsychic stressors of the caregiver experience (Demiris et al., 2009). These stressors (e.g., caregiver difficulty attending hospice visits in-person) result in care-recipient and caregiver needs that likely impact communication with clinicians. Building on Epstein and Street’s six functions of patient-centered communication (Epstein & Street, 2007), our model features six functions adapted to caregiver-centered communication at end-of-life: 1) building and maintaining trusting relationships, 2) providing information and support for care transitions and decisions, 3) soliciting symptom information, 4) discussing goals-of-care and facilitating decision-making based on patient and family values, 5) managing uncertainty, and 6) accommodating increased family involvement (Oliver et al., 2022). These functions influence proximal outcomes (e.g., knowledge of symptom management) and intermediate outcomes (e.g., symptom management, feeling supported by the healthcare team), which influence primary health outcomes of the family caregiving experience (e.g., anxiety, depression, caregiver burden, quality-of-life) (Washington et al., 2022; Wittenberg et al., 2021).

Figure 1:

Conceptual Model

Study purpose.

Given unmet communication needs in hospice and the stressor of distance caregiving, it is important to understand how geographic distance affects hospice communication from caregivers’ perspectives. The purpose of this study was to understand how the distance a hospice family caregiver lives from a hospice care-recipient is associated with caregiver ratings of caregiver-centered hospice communication. Our hypothesis was that distance would be inversely related to perceptions of communication quality, with caregivers who co-reside reporting higher hospice communication scores than local caregivers (caregivers who live less than one hour from the care-recipient) and distance caregivers (caregivers who live more than one hour from the care-recipient).

Materials and Methods

In this secondary analysis of data collected from two randomized clinical trials of telehealth-delivered behavioral interventions for hospice family caregivers (R01CA203999, R01NR012213, N=842), participants were English-speaking, unpaid, adult family caregivers of adult patients receiving hospice care from U.S. hospice agencies certified by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Family caregivers were eligible for the one trial (R01CA203999) if their care-recipient had a cancer diagnosis, whereas caregivers were eligible for the other trial (R01NR012213) regardless of care-recipient diagnosis. For both studies, the outcome of interest, caregiver perceptions of hospice communication, was taken at follow-up, while geographic proximity was collected as part of baseline demographics. For this study, participants were further eligible if they completed the Caregiver Centered Communication Questionnaire (CCCQ), described below (Demiris et al., 2020; Demiris et al., 2022). After removing cases for attrition, the effective sample size was 525.

Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the University of Pennsylvania (#828990, February 22, 2018) and Washington University in St. Louis (#326257, July 7, 2021) approved this study through a reliance agreement with University of Missouri. All participants provided verbal (R01CA203999) or written/electronic (R01NR012213) informed consent prior to study enrollment, per each trial’s IRB-approved protocol. Participant data were de-identified and securely stored on protected servers to maintain strict privacy standards.

Measures

The independent variable was the distance a caregiver lives from the care-recipient, which included three categorical groups based on a three-item survey response: co-residing (living with the care-recipient), living less than 1 hour away from the care-recipient (“local caregiver”), and living more than 1 hour away from the care-recipient (“distance caregiver”).

The main outcome was hospice family caregiver total scores on the validated 30-item Caregiver-Centered Communication Questionnaire (CCCQ) (Demiris et al., 2020; Demiris et al., 2022). The CCCQ measures the extent to which family caregivers feel their perspectives and needs are appropriately acknowledged and addressed by the health care team. It includes five subscales: exchange of information, fostering healthy relationships with healthcare team/provider, recognizing and responding to emotions, managing care, and decision-making. Response options are adapted to a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 meaning “strongly disagree” and 5 meaning “strongly agree.” Total scores range from 30 to 150; higher total scores indicate better caregiver perceptions of hospice communication. Measures were taken closest to baseline to minimize potential effect(s) of the interventions tested in the parent trials (Washington et al., 2022). The CCCQ demonstrates excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.98) (Demiris et al., 2020; Demiris, 2022).

In analysis, covariate controls included demographic (age, race, gender, education, employment, marital status, relationship to patient, self-reported physical health), and hospice-related contextual variables. Hospice related variables included the care-recipient’s current living situation (private residence or nursing home) and number of days in hospice (calculated based on the date of hospice enrollment and the date of baseline survey).

Data Analysis

Before estimating linear models to test our hypothesis, we examined descriptive statistics for all model variables. We used distributions for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. We also examined differences between caregiver distance categories on the covariates using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. We used a block-wise approach in estimating our linear models to test our hypothesis regarding caregiver distance and perception of caregiver-centered communication. The first model was a bivariate linear model with only the outcome and explanatory variable. In the second model, demographic controls were added. In the third model, hospice-related controls were added. We examined both the estimate and significance of the individual variables as well as the quality of the overall model in terms of fit. We considered p values of <.05 as evidence of a relationship between our input variables and outcome. We used these values to determine the results of our hypothesis testing as well as any other practically significant findings. We checked assumptions and diagnostics using a scatterplot for residuals and fitted values, a normal q-q plot, and a scale-location plot. Missing data were handled using case-wise deletion.

Results

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for the sample. Over half (56%) of caregivers lived with the care-recipient, 38% lived less than one hour away, and 5% lived more than one hour away. Caregivers were predominantly White race (76%), female (78%), partnered or married (66%), and an average age of 58 years old. Almost half (47%) had completed undergraduate college or higher education whereas 21% had a high school education or less; 55% were currently employed. Most caregivers (81%) cared for persons living in private residences. On average, care-recipients had been in hospice 22 days. Caregivers’ average physical quality-of-life score was 6.6, indicating moderate wellbeing. The average CCCQ score was 119 (23.3 standard deviation, SD).

Table 1.

Summary of Hospice Family Caregiver Demographics and Hospice Context

| Hospice Family Caregivers N=525 | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Distance Caregiver Lives From Hospice Care-Recipient | |

| Co-reside | 291 (56%) |

| Less than 1 hour away | 199 (38%) |

| More than 1 hour away | 28 (5%) |

| Caregiver Sex | |

| Female | 355 (78%) |

| Male | 98 (22%) |

| Caregiver Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 57.9 (12.1) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 59.0 [22.0, 94.0] |

| Caregiver Race | |

| White | 339 (76%) |

| Black or African American | 90 (20%) |

| Other | 18 (4%) |

| Caregiver Marital Status | |

| Married or Partnered | 343 (66%) |

| Single, Never Partnered | 83 (16%) |

| Divorced or Separated | 50 (10%) |

| Widowed | 43 (8%) |

| Other | 3 (1%) |

| Caregiver Education | |

| High school or less | 112 (21%) |

| Some college | 165 (32%) |

| College undergraduate degree or higher | 245 (47%) |

| Other | 1 (0%) |

| Caregiver Employment Status | |

| Not working | 233 (45%) |

| Working | 286 (55%) |

| Caregiver Self-Reported Physical Health | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.63 (2.20) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 7.00 [0, 10.0] |

| Care-recipient Days on Hospice | |

| Mean (SD) | 21.6 (12.0) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 18.0 [0, 79.0] |

| Care-recipient Residence | |

| Private residence | 426 (81%) |

| Nursing home | 68 (13%) |

| Other | 30 (6%) |

| Caregiver Score on Caregiver-Centered Communication Questionnaire (CCCQ) | |

| Mean (SD) | 119 (23.3) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 119 [30.0, 150] |

When considering proximity (Table 2), caregivers differed by age (P<0.001) and employment status (P<0.001), with co-residing caregivers being on average older (59.9 years old) and less likely to be employed (46% employed) than local caregivers (56.2 years old, 66% employed) and distance caregivers (53.9 years old, 68% employed). Care-recipient residence also differed by caregiver proximity (P<0.001). Co-residing caregivers predominantly lived with care-recipients in private residences (97%), while 28–29% of non-co-residing caregivers cared for persons living in nursing homes. Finally, caregiver self-reported physical health differed (P=0.01), with distance caregivers rating their health higher (7.9 mean) than co-residing (6.6 mean) and local (6.5 mean) caregivers. Overall, caregivers reported being in moderately good health. In bivariate analysis, caregiver perceptions of hospice communication significantly differed by proximity (P=0.002). CCCQ scores were highest among co-residing caregivers [mean 122 out of 130; SD 22.9] and similar among local caregivers (116 mean, 23.9 SD) and distance caregivers (117 mean, 20.1 SD).

Table 2.

Bivariate tests for differences between hospice family caregivers based on caregiver distance from hospice care-recipient.

| Co-residing Hospice Family Caregivers (N=291) | Local Hospice Family Caregivers Less than 1 hour away from hospice care-recipient (N=199) |

Distance Hospice Family Caregivers More than 1 hour away from hospice care-recipient (N=28) |

P-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Caregiver Sex | ||||

| Female | 193 (79%) | 140 (79%) | 18 (75%) | 0.896 |

| Male | 51 (21%) | 38 (21%) | 6 (25%) | |

| Caregiver Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 59.9 (12.1) | 56.2 (11.2) | 53.9 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 61.0 [24.0, 85.0] | 58.0 [26.0, 94.0] | 54.5 [22.0, 78.0] | |

| Caregiver Race | ||||

| White | 186 (78%) | 127 (72%) | 22 (92%) | 0.27 |

| Black or African American | 45 (19%) | 40 (23%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Other | 9 (4%) | 9 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Caregiver Marital Status | ||||

| Married or Partnered | 199 (69%) | 119 (60%) | 20 (71%) | 0.21 |

| Single, never partnered | 42 (14%) | 34 (17%) | 5 (18%) | |

| Divorced or Separated | 21 (7%) | 28 (14%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Widowed | 27 (9%) | 14 (7%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Other | 1 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Caregiver Education | ||||

| High school or less | 69 (24%) | 36 (18%) | 4 (14%) | 0.109 |

| Some college | 99 (34%) | 58 (29%) | 6 (21%) | |

| College undergraduate degree or higher | 122 (42%) | 104 (52%) | 18 (64%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Caregiver Employment Status | ||||

| Not working | 156 (54%) | 67 (34%) | 9 (32%) | <0.001 |

| Working | 131 (46%) | 130 (66%) | 19 (68%) | |

| Caregiver Self-reported Physical Health | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.59 (2.24) | 6.51 (2.14) | 7.86 (1.98) | 0.007 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 7.00 [0, 10.0] | 7.00 [0, 10.0] | 9.00 [4.00, 10.0] | |

| Care-recipient Days on Hospice | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 21.4 (11.8) | 22.7 (12.7) | 19.3 (7.47) | 0.263 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 17.0 [0, 79.0] | 20.0 [7.00, 78.0] | 16.5 [12.0, 41.0] | |

| Hospice Care-Recipient Residence | ||||

| Private residence | 282 (97%) | 124 (62%) | 15 (54%) | <0.001 |

| Nursing home | 3 (1%) | 56 (28%) | 8 (29%) | |

| Other | 6 (2%) | 19 (10%) | 5 (18%) | |

| Caregiver Score on Caregiver-Centered Communication Questionnaire (CCCQ) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 122 (22.9) | 116 (23.9) | 117 (20.1) | 0.002 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 123 [30.0, 150] | 115 [30.0, 150] | 116 [85.0, 150] | |

P values were derived from Chi-square tests for all categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for all continuous variables.

The results of the multivariate model (Table 3) indicated that, on average, local caregivers had lower CCCQ scores than co-residing caregivers (b=−7.716, se = 2.855). On average, local caregivers had a CCCQ score of 6 points less than co-residing caregivers, a finding that persisted across all three models. The estimate also suggested that for every 10 years of caregiver age, the CCCQ score increased on average by 2.5 points. Overall, the final model demonstrated a better fit to the data than the null model (F = 2.520, p<.001) and explained roughly 11% of the variation in CCCQ scores (R2 = .112).

Table 3.

Linear regression results for models of caregiver distance from hospice care-recipient

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Distance (ref = Co-reside) | |||

| Less than 1 hour away | −6.298 ** | −8.232 ** | −7.716 ** |

| (2.129) | (2.560) | (2.855) | |

| More than 1 hour away | −4.417 | −6.394 | −5.836 |

| (4.579) | (4.867) | (5.108) | |

| Relationship (ref = Adult Child) | |||

| Spouse/Partner | −3.386 | −3.135 | |

| (3.194) | (3.222) | ||

| Other relative | 6.855 | 6.885 | |

| (3.760) | (3.796) | ||

| Other non-relative | −5.299 | −5.194 | |

| (3.438) | (3.452) | ||

| Age | 0.284 ** | 0.250 * | |

| (0.107) | (0.108) | ||

| Race (ref = White) | |||

| Black/African American | 5.567 * | 4.733 | |

| (2.804) | (2.880) | ||

| Other Race | 4.621 | 3.230 | |

| (5.238) | (5.318) | ||

| Male (ref = female) | −2.421 | −2.794 | |

| (2.580) | (2.585) | ||

| Education (ref = High school or less) | |||

| Some college | 0.577 | 0.808 | |

| (2.979) | (2.986) | ||

| Undergraduate or higher | −3.751 | −3.197 | |

| (2.826) | (2.837) | ||

| Other Education | 11.681 | ||

| (21.607) | |||

| Marital status (ref = Partnered) | |||

| Single, never partnered | −5.834 | −5.965 | |

| (3.407) | (3.388) | ||

| Widowed | −4.574 | −4.636 | |

| (3.930) | (3.900) | ||

| Divorced/separated | −1.261 | −0.226 | |

| (3.679) | (3.828) | ||

| Other Marital | 2.362 | 2.625 | |

| (12.562) | (12.476) | ||

| Physical health | 0.747 | 0.599 | |

| (0.501) | (0.515) | ||

| Patient residence (ref = Private residence) | |||

| Nursing home | 0.199 | ||

| (3.370) | |||

| Other Residence | −0.373 | ||

| (4.674) | |||

| Hospice days | 0.135 | ||

| (0.100) | |||

| N. obs. | 518 | 427 | 419 |

| R squared | 0.017 | 0.120 | 0.112 |

| F statistic | 4.462 | 3.101 | 2.520 |

| P value | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

p < 0.001

p < 0.01

p < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study of 525 hospice family caregivers, we found hospice family caregivers who lived within one hour of the hospice care-recipient reported less effective communication with the hospice team than co-residing caregivers. Although not statistically significant in multivariate models, likely due to small sample size, distance caregivers also reported less effective communication than co-residing caregivers. In bivariate models, the mean CCCQ scores for local caregivers and distance caregivers were nearly identical and both lower than co-residing caregiver scores, suggesting hospice family caregivers who do not co-reside experience less adequate information exchange, relationship development, emotional responsiveness, care management, and decision-making communication in hospice care than co-residing caregivers.

When caregivers co-reside, there are fewer barriers to developing effective hospice communication and rapport between caregivers and hospice staff. Co-residing caregivers are more likely to be present at home visits, easing communication with hospice staff and reducing topic avoidance, and may be more informed by firsthand knowledge about the care-recipient’s condition and needs (Bevan & Sparks, 2011). Local caregivers have reported difficulty obtaining adequate information from hospice due to a lack of overlap between family caregiver and hospice staff visits, creating dissatisfaction (Cagle & Kovacs, 2011), while distance caregivers have reported other challenges (Cagle & Munn, 2012). Most distance caregivers report feeling inadequately informed, disconnected, and frustrated about receiving information second hand (Blackstone et al., 2019; Cagle & Munn, 2012; Mazanec, 2012; Mazanec et al., 2011). As one study found, regular contact between hospice teams and caregivers is essential for hospice staff to learn the nuanced needs of family caregivers and provide information and support tailored to those needs (Hughes et al., 2019). Expert teaching from hospice staff, a caregiver priority that benefits from in-person communication (Ellington, Cloyes, et al., 2018), may also be compromised for caregivers who do not co-reside. Regardless of proximity, caregivers may have the same expectations about hospice communication quality and frequency.

We found older caregivers rated hospice communication more favorably than younger caregivers, which is consistent with previous research suggesting older persons more favorably rate healthcare communication quality (Munoz et al., 2020; Spooner et al., 2016). It is unknown why age predicts hospice communication perceptions. Many clinician and caregiver factors may have contributed to differences (e.g., clinician biases, differences by age in caregiver health or health literacy) (Rutten et al., 2006; Spooner et al., 2016; Wittenberg et al., 2019). Hospice clinicians should be mindful that younger caregivers may have unmet communication needs.

Caregiver-patient relationship can affect caregiver-patient distance (Cagle & Munn, 2012), but in multivariate modelling it was not a significant predictor of communication perceptions. Still, it is important to consider how relationships in the context of distance may influence hospice communication. Many spouses and partners co-reside with hospice care-recipients, while adult children may not co-reside or may do so irregularly or only closer to the parent’s death (Cagle & Munn, 2012). Adult child caregivers often attend to competing priorities including employment, child rearing, and managing a dying parent’s care, often at a distance, contributing to stress and anxiety, which can negatively affect how a person retains or comprehends information (Nelissen et al., 2018; Rai et al., 2015). In one study, for example, adult child caregivers who lived more than 30 minutes away from care-recipients experienced greater depression symptoms than co-residing caregivers; social support was found to reduce depressive symptoms in these caregivers (Li et al., 2019). Research is needed to understand how stress influences the way family caregivers and hospice teams communicate and to test interventions, including provision of social support, that can improve communication by reducing caregiver stress.

Research is needed to better understand why local caregivers, specifically, perceive hospice communication less favorably and whether caregivers’ level of care involvement (e.g., frequency of involvement in symptom assessment and management, activities of daily living tasks), which may relate to caregiver distance, and comfort discussing caregiving are related to perceptions of hospice communication quality. Evidence suggests family caregiver involvement in patient care contributes to better clinical outcomes for both patients and caregivers, with better quality-of-life and lower anxiety for caregivers who do not avoid discussing caregiving topics (Wieczorek et al., 2018; Wittenberg et al., 2021). Qualitative studies that explore local hospice family caregiver communication expectations, experiences, unmet needs, and mediating factors are recommended.

Likewise, research is needed to understand hospice teams’ assumptions, expectations, and practices regarding communication with local caregivers. Proximal caregiving implies greater in-person access to care-recipients and to hospice agency resources than distance caregiving, yet it is possible hospice teams’ assumptions about local caregivers’ informational and support needs are inadequate or misaligned. Health literacy (i.e., understanding a care-recipient’s illness and prognosis) and hospice literacy (i.e., understanding what hospice entails) are likely related to perceptions of hospice communication but were not measured in this study. Research is needed to understand if health literacy and hospice literacy differs by caregiver proximity and how these variables may mediate perceptions of hospice communication.

Evidence suggests telehealth technology may mitigate stressors associated with distance caregiving by improving timeliness and frequency of communication between caregivers and clinicians (Hajjar & Kragen, 2021), increasing access to health services and improving efficiency (Salem et al., 2020), improving caregiver engagement (Ladin et al., 2021), and reducing caregiver anxiety and distress (Douglas et al., 2021). A recent systematic review found telehealth was associated with high levels of patient and caregiver satisfaction across four key dimensions: information sharing, user (patient, caregiver) focus, system experience, and overall satisfaction (Orlando et al., 2019). Although some caregivers express concern that telehealth technology may limit a clinician’s ability to provide comfort or develop relationships (Ladin et al., 2021), evidence suggests telehealth platforms do not hinder empathic communication or a clinician’s ability to develop relational closeness with caregivers (Solli & Hvalvik, 2019).

To improve communication with all caregivers, especially caregivers who do not co-reside, hospice teams and policy makers should support clinician training in distance communication (Barbosa & Silva, 2017), specifically in perception of non-verbal signals (Barbosa & Silva, 2017), and the implementation of telehealth interventions and web-based tools that enable high-quality distance communication between caregivers and hospice teams (Blackstone et al., 2019; Doolittle et al., 2019; Douglas et al., 2021; Oliver et al., 2017; Washington et al., 2020). One such example is ENVISION, a digital tool that quickly and easily enables family caregivers to provide interdisciplinary hospice teams with up-to-date data about ten common hospice patient issues (e.g., pain, anxiety) and four common hospice family caregiver issues (e.g., depression, insomnia), improving communication between hospice teams and family caregivers familiar with a patient’s daily experiences (Washington et al., 2020). Another example of successful deployment of telehealth is a technology-assisted patient care platform called PEACE (Ingram et al., 2020). Developed by the Mayo Clinic, PEACE connects patients and caregivers to high-quality, evidence-based clinical care and symptom control, care coordination, and patient support in hospice (Ingram et al., 2020). Family caregiver engagement with interdisciplinary hospice teams through telehealth technology enables information exchange, teaching, and relationship development between caregivers and hospice staff when caregivers cannot be physically present for hospice visits. Distance caregivers who cannot regularly report on their care-recipient’s daily symptoms may experience barriers to using these technologies but may benefit from such tools if hospice teams provide the data. Further feasibility and acceptability studies of these interventions is recommended.

Distance caregivers value vigilant monitoring and reporting of their family member’s wellbeing and want frequent, regular updates initiated by the care team (Gunn et al., 2021), a preference that shifts the burden of communication onto hospice teams. The implications of increasing hospice team workload through increased communication with distance caregivers should be considered given hospice clinicians’ high risk of burn-out (Parola et al., 2017). Technology has the potential to improve distance communication for both clinicians and family caregivers, but interventions must reduce, not increase, hospice team burden (Gunn et al., 2021).

Hospice teams should also proactively discuss challenges associated with distance communication, set reasonable expectations with families, and create communication plans optimized around caregiver needs, such as communicating with a single clinical contact or communicating outside regular hospice hours (Gunn et al., 2021). Consistent with current practices, hospice teams should continue to discuss changes in a patient’s health and care needs so that when needed distance caregivers can arrange travel and provide care in-person, if possible (Herbst et al., 2022).

As we learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented many caregivers from being physically present with friends and family at the end-of-life, effective remote communication, as perceived by bereaved family caregivers, is associated with significantly better ratings of end-of-life care experiences (Ersek et al., 2021). Innovative communication technologies may also enable more convenient communication for employed caregivers who may need phone access, allowance for time off, and use of employer benefits to maintain care and communication with the hospice care-recipient (Cagle & Munn, 2012). In our study, 66% of local caregivers and 68% of distance caregivers were employed, significantly more than the co-residing group (46%).

This study has limitations. First, although the model identified differences in communication perceptions by caregiver proximity, the model cannot explain why differences occur. Second, the model only explained 11% of the variation in CCCQ scores due to limited variables available in the dataset. Other social, economic, cultural, and clinical variables may better explain differences in communication scores among caregiver proximity groups. For example, racial or cultural congruence between hospice teams and caregivers, caregivers’ familiarity or prior experience with hospice, caregiver communication self-efficacy, and clinician training in communication may help explain differences. Further research is also needed to understand if a caregiver’s relationship to the patient or other variables such as caregiver health literacy moderate perceptions of hospice communication. Third, while the sample size was adequate for this analysis, the distance caregiving group was small. Although our sensitivity analysis showed no difference between the groups when distance caregivers were removed, a larger sample of distance caregivers is recommended for future analysis, as are more precise measures of distance, such as minutes or miles/kilometers between caregivers and care-recipients. Still, this study advances the science of caregiver research by providing novel and actionable evidence about hospice communication needs based on caregiver proximity and further justifies the need for distance communication interventions.

Conclusion

To provide quality care to hospice patients and manage their own needs and stressors, hospice family caregivers require effective, caregiver-centered communication with hospice teams. This study found caregiver/care-recipient geographic proximity is associated with differences in perceptions of hospice communication quality. Hospice team training in distance communication best practices and interventions such as telehealth technology and virtual tools are needed to improve communication and collaboration between hospice teams and caregivers who do not co-reside. Such interventions and advancements may enhance support for co-residing caregivers, as well.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (R01NR012213), registered on Clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03712410 (PISCES: A Problem Solving Intervention for Hospice Caregivers, Principal Investigator Dr. GEORGE DEMIRIS) and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA203999), registered on ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT02929108 (ACCESS: Access for Cancer Caregivers for Education and Support for Shared Decision Making, Principal Investigator Dr. DEBRA PARKER OLIVER). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. In addition, Dr. Starr is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award training program in Individualized Care for At Risk Older Adults at the University of Pennsylvania, National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR009356).

NewCourtland Center for Transitions and Health, Department of Biobehavioral Health Sciences,University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, 418 Curie Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Declaration of Interests Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Barbosa IA, & Silva M. (2017, Sep–Oct). Nursing care by telehealth: what is the influence of distance on communication? Rev Bras Enferm, 70(5), 928–934. 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan JL, & Sparks L. (2011, Oct). Communication in the context of long-distance family caregiving: an integrated review and practical applications. Patient Educ Couns, 85(1), 26–30. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone E, Lipson AR, & Douglas SL (2019, Aug). Closer: A videoconference intervention for distance caregivers of cancer patients. Res Nurs Health, 42(4), 256–263. 10.1002/nur.21952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle JG, & Kovacs PJ (2011, Jan). Informal caregivers of cancer patients: perceptions about preparedness and support during hospice care. J Gerontol Soc Work, 54(1), 92–115. 10.1080/01634372.2010.534547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle JG, & Munn JC (2012). Long-distance caregiving: a systematic review of the literature. J Gerontol Soc Work, 55(8), 682–707. 10.1080/01634372.2012.703763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle JG, Van Dussen DJ, Culler KL, Carrion I, Hong S, Guralnik J, & Zimmerman S. (2016, Feb). Knowledge About Hospice: Exploring Misconceptions, Attitudes, and Preferences for Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 33(1), 27–33. 10.1177/1049909114546885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candrian C, Tsantes A, Matlock DD, Tate C, & Kutner JS (2018, Nov). “I just need to know they are going to do what they say they’re going to do with my mom.” Understanding hospice expectations from the patient, caregiver and admission nurse perspective. Patient Educ Couns, 101(11), 2025–2030. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casarett D, Crowley R, Stevenson C, Xie S, & Teno J. (2005, Feb). Making difficult decisions about hospice enrollment: what do patients and families want to know? J Am Geriatr Soc, 53(2), 249–254. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Beal EW, Schneider EB, Okunrintemi V, Zhang XF, & Pawlik TM (2018, Apr). Patient-Provider Communication and Health Outcomes Among Individuals with Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Disease in the USA. J Gastrointest Surg, 22(4), 624–632. 10.1007/s11605-017-3610-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi NC, & Demiris G. (2017, Jun). Family Caregivers’ Pain Management in End-of-Life Care: A Systematic Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 34(5), 470–485. 10.1177/1049909116637359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi NC, Demiris G, Pike KC, Washington K, & Oliver DP (2018, Apr). Pain Management Concerns From the Hospice Family Caregivers’ Perspective. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 35(4), 601–611. 10.1177/1049909117729477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi NC, Demiris G, Pike KC, Washington K, & Oliver DP (2018, Apr-Sep). Exploring the Challenges that Family Caregivers Faced When Caring for Hospice Patients with Heart Failure. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care, 14(2–3), 162–176. 10.1080/15524256.2018.1461168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloyes KG, Carpenter JG, Berry PH, Reblin M, Clayton M, & Ellington L. (2014, Jul). “A True Human Interaction”: Comparison of Family Caregiver and Hospice Nurse Perspectives On Needs of Family Hospice Caregivers. J Hosp Palliat Nurs, 16(5), 282–290. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Ganz FD, Han CJ, Pike K, Oliver DP, & Washington K. (2020, Jul). Design and Preliminary Testing of the Caregiver-Centered Communication Questionnaire (CCCQ). J Palliat Care, 35(3), 154–160. 10.1177/0825859719887239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Oliver DP, & Wittenberg-Lyles E. (2009, Apr-May). Assessing caregivers for team interventions (ACT): a new paradigm for comprehensive hospice quality care. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care, 26(2), 128–134. 10.1177/1049909108328697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Washington KT, Pitzer K, Oliver DP. (2022). Reliability and Validity Testing of the Caregiver Centered Communication Questionnaire. Journal of Nursing Measurement, In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle GC, Nelson EL, Spaulding AO, Lomenick AF, Krebill HM, Adams NJ, Kuhlman SJ, & Barnes JL (2019, Sep). TeleHospice: A Community-Engaged Model for Utilizing Mobile Tablets to Enhance Rural Hospice Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 36(9), 795–800. 10.1177/1049909119829458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas SL, Mazanec P, Lipson A, & Leuchtag M. (2016, Apr 10). Distance caregiving a family member with cancer: A review of the literature on distance caregiving and recommendations for future research. World J Clin Oncol, 7(2), 214–219. 10.5306/wjco.v7.i2.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas SL, Mazanec P, Lipson AR, Day K, Blackstone E, Bajor DL, Saltzman J, & Krishnamurthi S. (2021, Jan). Videoconference Intervention for Distance Caregivers of Patients With Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JCO Oncol Pract, 17(1), e26–e35. 10.1200/OP.20.00576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington L, Clayton MF, Reblin M, Donaldson G, & Latimer S. (2018, Mar). Communication among cancer patients, caregivers, and hospice nurses: Content, process and change over time. Patient Educ Couns, 101(3), 414–421. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington L, Cloyes KG, Xu J, Bellury L, Berry PH, Reblin M, & Clayton MF (2018, Apr). Supporting home hospice family caregivers: Insights from different perspectives. Palliat Support Care, 16(2), 209–219. 10.1017/S1478951517000219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, & Street RL Jr. (2007). Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health Publication; No. 07–6225, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Ersek M, Smith D, Griffin H, Carpenter JG, Feder SL, Shreve ST, Nelson FX, Kinder D, Thorpe JM, & Kutney-Lee A. (2021, Aug). End-Of-Life Care in the Time of COVID-19: Communication Matters More Than Ever. J Pain Symptom Manage, 62(2), 213–222 e212. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzarano F, Cimarolli VR, Minahan J, & Horowitz A. (2020, Jun 26). Long-Distance Caregivers: What are Their Experiences with Formal Care Providers? Clin Gerontol, 1–12. 10.1080/07317115.2020.1783043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields B, Rodakowski J, James AE, & Beach S. (2018, Dec). Caregiver health literacy predicting healthcare communication and system navigation difficulty. Fam Syst Health, 36(4), 482–492. 10.1037/fsh0000368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T, & Jobst M. (2020, Sep 2). Capturing the Spatial Relatedness of Long-Distance Caregiving: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(17). 10.3390/ijerph17176406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke A, Kramer B, Jann PM, van Holten K, Zentgraf A, Otto U, & Bischofberger I. (2019, Oct). [Current findings on distance caregiving : What do we know and what do we not (yet) know?]. Z Gerontol Geriatr, 52(6), 521–528. 10.1007/s00391-019-01596-2 (Aktuelle Befunde zu “distance caregiving” : Was wissen wir und was (noch) nicht?) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn KM, Luker J, Ramanathan R, Skrabal Ross X, Hutchinson A, Huynh E, & Olver I. (2021, Dec 9). Choosing and Managing Aged Care Services from Afar: What Matters to Australian Long-Distance Care Givers. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(24). 10.3390/ijerph182413000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar L, & Kragen B. (2021). Timely Communication Through Telehealth: Added Value for a Caregiver During COVID-19. Front Public Health, 9, 755391. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.755391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst FA, Schneider N, & Stiel S. (2022). Long-distance caregiving at the end of life: a protocol for an exploratory qualitative study in Germany. BMC Palliat Care, 21(69). 10.1186/s12904-022-00967-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes NM, Noyes J, Eckley L, & Pritchard T. (2019, Feb 8). What do patients and family-caregivers value from hospice care? A systematic mixed studies review. BMC Palliat Care, 18(1), 18. 10.1186/s12904-019-0401-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang D, Teno JM, Clark M, Shield R, Williams C, Casarett D, & Spence C. (2014, Dec). Family perceptions of quality of hospice care in the nursing home. J Pain Symptom Manage, 48(6), 1100–1107. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram C, Bruce CJ, Shadbolt EL, Mahnke E, Darkins A, Dodd S, & Streeter LM (2020, Jun). Let There Be PEACE: Improving Continuous Symptom Monitoring in Hospice Patients. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes, 4(3), 287–294. 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwame A, & Petrucka PM (2021, Sep 3). A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs, 20(1), 158. 10.1186/s12912-021-00684-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladin K, Porteny T, Perugini JM, Gonzales KM, Aufort KE, Levine SK, Wong JB, Isakova T, Rifkin D, Gordon EJ, Rossi A, Koch-Weser S, & Weiner DE (2021, Dec 1). Perceptions of Telehealth vs In-Person Visits Among Older Adults With Advanced Kidney Disease, Care Partners, and Clinicians. JAMA Netw Open, 4(12), e2137193. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, & Cagle JG (2017, Jul/Oct). Factors Associated With Opinions About Hospice Among Older Adults: Race, Familiarity With Hospice, and Attitudes Matter. J Palliat Care, 32(3–4), 101–107. 10.1177/0825859717738441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Mao W, Chi I, & Lou VWQ (2019, Feb). Geographical proximity and depressive symptoms among adult child caregivers: social support as a moderator. Aging Ment Health, 23(2), 205–213. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1399349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luth EA, Maciejewski PK, Phongtankuel V, Xu J, & Prigerson HG (2021, May). Associations Between Hospice Care and Scary Family Caregiver Experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage, 61(5), 909–916. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec P. (2012, Nov). Distance caregiving a parent with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs, 28(4), 271–278. 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec P, Daly BJ, Ferrell BR, & Prince-Paul M. (2011, May). Lack of communication and control: experiences of distance caregivers of parents with advanced cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum, 38(3), 307–313. 10.1188/11.ONF.307-313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, Williams-Piehota P, Nadler E, Arora NK, Lawrence W, & Street RL Jr. (2011, Apr). Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med, 72(7), 1085–1095. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz IO, Amo Setien FJ, Diaz Agea JL, Hernandez Ruiperez T, Adanez Martinez MG, & Leal Costa C. (2020, Jun). The communication skills and quality perceived in an emergency department: The patient’s perspective. Int J Nurs Pract, 26(3), e12831. 10.1111/ijn.12831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2004). Miles Away: The Metlife study of long-distance caregiving. In Caregiving.org (pp. 1–16). https://www.caregiving.org/wp-ontent/uploads/2020/05/milesaway.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen E, Prickaerts J, & Blokland A. (2018, Jun 1). Acute stress negatively affects object recognition early memory consolidation and memory retrieval unrelated to state-dependency. Behav Brain Res, 345, 9–12. 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, Vedsted P, Bro F, & Guldin MB (2017, Dec). Preloss grief in family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Psychooncology, 26(12), 2048–2056. 10.1002/pon.4416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okunrintemi V, Spatz ES, Di Capua P, Salami JA, Valero-Elizondo J, Warraich H, Virani SS, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, Butt AA, Borden WB, Dharmarajan K, Ting H, Krumholz HM, & Nasir K. (2017, Apr). Patient-Provider Communication and Health Outcomes Among Individuals With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in the United States: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2010 to 2013. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 10(4). 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DP, Demiris G, Benson J, White P, Wallace A, Pitzer K, Washington KT (2022). Family caregiving experiences with hospice lung cancer patients compared to other cancer types. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DP, Demiris G, Washington KT, Clark C, & Thomas-Jones D. (2017, Aug 1). Challenges and Strategies for Hospice Caregivers: A Qualitative Analysis. Gerontologist, 57(4), 648–656. 10.1093/geront/gnw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DP, Demiris G, Washington KT, Kruse RL, & Petroski G. (2017, Nov). Hospice Family Caregiver Involvement in Care Plan Meetings: A Mixed-Methods Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 34(9), 849–859. 10.1177/1049909116661816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DP, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K, Kruse RL, Albright DL, Baldwin PK, Boxer A, & Demiris G. (2013, Dec). Hospice caregivers’ experiences with pain management: “I’m not a doctor, and I don’t know if I helped her go faster or slower”. J Pain Symptom Manage, 46(6), 846–858. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando JF, Beard M, & Kumar S. (2019). Systematic review of patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients’ health. PLoS One, 14(8), e0221848. 10.1371/journal.pone.0221848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola V, Coelho A, Cardoso D, Sandgren A, & Apostolo J. (2017, Jul). Prevalence of burnout in health professionals working in palliative care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep, 15(7), 1905–1933. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, & Skaff MM (1990, Oct). Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phongtankuel V, Paustian S, Reid MC, Finley A, Martin A, Delfs J, Baughn R, & Adelman RD (2017, Mar). Events Leading to Hospital-Related Disenrollment of Home Hospice Patients: A Study of Primary Caregivers’ Perspectives. J Palliat Med, 20(3), 260–265. 10.1089/jpm.2015.0550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phongtankuel V, Scherban BA, Reid MC, Finley A, Martin A, Dennis J, & Adelman RD (2016, Jan). Why Do Home Hospice Patients Return to the Hospital? A Study of Hospice Provider Perspectives. J Palliat Med, 19(1), 51–56. 10.1089/jpm.2015.0178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley DD, & McCleskey SG (2021, Jan). Improving Care Experiences for Patients and Caregivers at End of Life: A Systematic Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 38(1), 84–93. 10.1177/1049909120931468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragan SL (2016). Overview of communication. In Wittenberg E, Ferell BR, & Goldsmith J. (Eds.), Textbook of Palliative Communication (pp. 1–9). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rai MK, Loschky LC, & Harris RJ (2015). The effects of stress on reading: A comparison of first-language versus intermediate second-language reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(2), 348–363. 10.1037/a0037591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reblin M, Clayton MF, Xu J, Hulett JM, Latimer S, Donaldson GW, & Ellington L. (2017, Dec). Caregiver, patient, and nurse visit communication patterns in cancer home hospice. Psychooncology, 26(12), 2285–2293. 10.1002/pon.4361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten LJ, Augustson E, & Wanke K. (2006). Factors associated with patients’ perceptions of health care providers’ communication behavior. J Health Commun, 11 Suppl 1, 135–146. 10.1080/10810730600639596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem R, El Zakhem A, Gharamti A, Tfayli A, & Osman H. (2020, Dec). Palliative Care via Telemedicine: A Qualitative Study of Caregiver and Provider Perceptions. J Palliat Med, 23(12), 1594–1598. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz B, Goncharov L, Emmerich N, Lu VN, Chapman M, Clark SJ, Wilson T, Slade D, & Mitchell I. (2020, Oct). Clinicians’ accounts of communication with patients in end-of-life care contexts: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns, 103(10), 1913–1921. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonover CB, Brody EM, Hoffman C, & Kleban MH (1988, Dec). Parent care and geographically distant children. Res Aging, 10(4), 472–492. 10.1177/0164027588104002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Kozlov E, Shen MJ, Adelman RD, & Reid MC (2018, Mar). Awareness and Misperceptions of Hospice and Palliative Care: A Population-Based Survey Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 35(3), 431–439. 10.1177/1049909117715215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Reid MC, Czaja SJ, Dignam R, Baughn R, Newmark M, Prigerson HG, Teresi J, & Adelman RD (2019, Apr). Home Hospice Caregivers’ Perceived Information Needs. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 36(4), 302–307. 10.1177/1049909118805413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solli H, & Hvalvik S. (2019, Nov 27). Nurses striving to provide caregiver with excellent support and care at a distance: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res, 19(1), 893. 10.1186/s12913-019-4740-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, & Zoorob RJ (2016, May). Disparities in perceived patient-provider communication quality in the United States: Trends and correlates. Patient Educ Couns, 99(5), 844–854. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford L. (2005). Maintaining long-distance and cross-residential relationships. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Starr LT, Bullock K, Washington K, Aryal S, Oliver DP, & Demiris G. (2022, Apr). Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, Caregiver Burden, and Perceptions of Caregiver-Centered Communication among Black and White Hospice Family Caregivers. J Palliat Med, 25(4), 596–605. 10.1089/jpm.2021.0302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LT, Washington KT, McPhillips M, Pitzer K, Oliver DP, Demiris G. (2022). Insomnia Symptoms and Associations with Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, and Caregiver Burden Among Hospice Family Caregivers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo GJ, Broxson A, Munsell M, & Cohen MZ (2010, Jan). Caring for the caregiver. Oncol Nurs Forum, 37(1), E50–57. 10.1188/10.ONF.E50-E57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi H, Nakaaki S, Satoh M, Yamamoto M, Chino N, & Hadano K. (2016, Jan). Relationships among Communication Self-Efficacy, Communication Burden, and the Mental Health of the Families of Persons with Aphasia. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 25(1), 197–205. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop DP, Meeker MA, Kerr C, Skretny J, Tangeman J, & Milch R. (2012, Feb). The nature and timing of family-provider communication in late-stage cancer: a qualitative study of caregivers’ experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage, 43(2), 182–194. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington KT, Craig KW, Oliver DP, Ruggeri JS, Brunk SR, Goldstein AK, & Demiris G. (2019, Nov-Dec). Family caregivers’ perspectives on communication with cancer care providers. J Psychosoc Oncol, 37(6), 777–790. 10.1080/07347332.2019.1624674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington KT, Demiris G, Oliver DP, Backonja U, Norfleet M, Han CJ, & Popescu M. (2020, Jul 1). ENVISION: A Tool to Improve Communication in Hospice Interdisciplinary Team Meetings. J Gerontol Nurs, 46(7), 9–14. 10.3928/00989134-20200605-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington KT, Demiris G, Pitzer K, Tunink C, Benson JJ, & Oliver DP (2022). Family members’ perceptions of caregiver-centered communication with hospice interdisciplinary teams: Relationship to caregiver wellbeing. Journal of Palliative Care, Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Raley L, & Haggerty K. (2020). Caregiving in the U.S. 2020: A Focused Look at Family Caregivers of Adults Age 50+. In Caregiving.org (pp. 1–88). Greenwald Research. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/AARP1340_RR_Caregiving50Plus_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek CC, Nowak P, Frampton SB, & Pelikan JM (2018, Aug). Strengthening patient and family engagement in healthcare - The New Haven Recommendations. Patient Educ Couns, 101(8), 1508–1513. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg E, Buller H, Ferrell B, Koczywas M, & Borneman T. (2017, Dec). Understanding Family Caregiver Communication to Provide Family-Centered Cancer Care. Semin Oncol Nurs, 33(5), 507–516. 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg E, Goldsmith JV, & Kerr AM (2019, Nov). Variation in health literacy among family caregiver communication types. Psychooncology, 28(11), 2181–2187. 10.1002/pon.5204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg E, Kerr AM, & Goldsmith J. (2021, Feb). Exploring Family Caregiver Communication Difficulties and Caregiver Quality of Life and Anxiety. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 38(2), 147–153. 10.1177/1049909120935371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Freedman VA, Ornstein KA, Mulcahy JF, & Kasper JD (2020, Apr 1). Evaluation of Hospice Enrollment and Family and Unpaid Caregivers’ Experiences With Health Care Workers in the Care of Older Adults During the Last Month of Life. JAMA Netw Open, 3(4), e203599. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York GS, Churchman R, Woodard B, Wainright C, & Rau-Foster M. (2012, Mar). Free-text comments: understanding the value in family member descriptions of hospice caregiver relationships. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 29(2), 98–105. 10.1177/1049909111409564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentgraf A, Jann PM, Myrczik J, & van Holten K. (2019, Oct). [Distance caregiving? : A qualitative interview study with distance caregivers]. Z Gerontol Geriatr, 52(6), 539–545. 10.1007/s00391-019-01607-2 (Pflegen auf Distanz? : Eine qualitative Interviewstudie mit “distance caregivers”.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]