Abstract

Introduction and importance

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors are common neoplasm with different biological features ranging from benign to malignant. The majority of these tumors are smaller than 5 cm, whereas those larger are termed giant schwannomas. When localized in the lower legs, the maximum length of the schwannoma is less than 10 cm. We report a case of giant schwannoma of the leg and its management.

Case presentation

A 11-year-old boy presented with a 13 cm × 5 cm firm, smooth, well-defined margin mass in the posterior-medial aspect of right leg. The tumor was fusiform, well capsulated, multi-lobulated soft tissue with 13 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm in size at the biggest region. On MRI the tumor was low signal, isointense with adjacent tissue on T1S, hyper-intense on T2-FS sequences and surrounded by a thin fat-like intense rim. Biopsy findings were considered most consistent with Schwannoma (Antoni A). Tumor resection was performed. The mass appeared capsulated, white, and glistening with 132 mm × 45 mm × 34 mm in size. Postoperative course was uneventful without neurological deficit.

Clinical discussion and conclusion

Schwannomas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors that derived almost entirely from Schwann cells. Schwannomas usually affect the head and neck region, localization in the lower extremity is rare. When located in lower extremity, the maximum diameter of 5 cm is described in most studies. Clinical presentation of schwannomas is unclear and unspecific. Diagnosis is based on ultrasound, MRI, and histology. The recommended treatment for schwannoma is surgical enucleation or resection without damaging the involved nerve.

Keywords: Giant schwannoma, Enucleation

1. Introduction

Schwannomas are common in the sacral plexus, the brachial plexus, and the sciatic nerve. Their presence in the lower limbs is reported in only 1 % of the cases. These are benign tumor arising from peripheral nerve sheaths and are encapsulated by the epineurium. The tumor could be asymptomatic due to slow growth and adaptation of the nerve fiber to the space occupied by the tumor within nerve sheath. Total resection of tumor after careful dissection of nerve fibers can result in good outcomes since the recurrence and malignant transformation rates are low. The case report is reported in line with SCARE criteria [1].

2. Presentation of case

A 11-year-old boy presented to our clinic with complaints of a solitary swelling over the medial-posterior aspect of his right leg. His grandparent claimed that the swelling has been gradually increasing in size in the past two year. In the few months prior to presenting to the clinic, the patient had experienced minor pain over the mass but he could still walk normally. His past medical history was unremarkable and there was no family history suggestive of malignancy.

Local examination revealed a 13 cm × 5 cm firm, smooth, well-defined margin mass in the posterior-medial aspect of right leg. The mass was not attached to the underlying tissue. There was no local increase of temperature or erythema. The patient had full ankle and knee active range of motion, normal strength compared to the left side. Neurovascular status of the right foot was intact.

MRI revealed a fusiform, well capsulated, multi-lobulated soft tissue mass located between superficial and deep posterior compartment of the right leg. The tumor was 13 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm in size at the biggest region (Fig. 1). The tumor was low signal, isointense with adjacent tissue on T1S, hyper-intense on T2-FS sequences and surrounded by a thin fat-like intense rim. The tumor was heterogeneously enhanced with contrast. There was no bone involvement in the tumor in the right leg. Coincidentally, MRI showed a bone eroding lesion in the lower left tibia which was low intensity on T1-S, heterogeneously intermediate signal with a low signal peripheral rim on T2. X-ray showed a multilobulated lucent lesion eccentrically located in the lateral border of lower shinbone.

Fig. 1.

Schwannoma in lower leg on MRI with largest size 13.7 × 4 × 5.5 cm.

Open biopsy was performed on both lesions. Histology of right soft tissue tumor demonstrated tissue with narrowed, elongated, and wavy cells with tapered ends interspersed with collagen fibers. Tumor cells had less cytoplasm, dense chromatin. These features were considered most consistent with schwannoma (Antoni A). Histology of the left tibia bone showed spindle shaped fibroblasts arranged in storiform pattern, interspersed with multinucleated giant cells and phagocytes consistent with a non-ossifying fibroma.

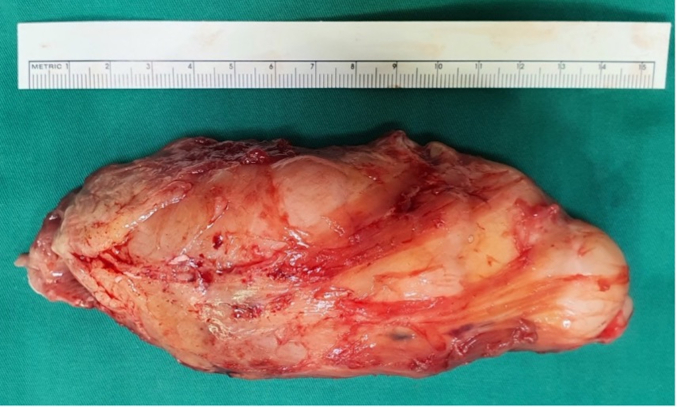

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia by experienced surgeons in soft tissue tumors with the patient placed in a supine position and a pneumatic tourniquet inflated at 100 mmHg higher than the systolic pressure that was measured at the arm of the patient. A complete surgical excision was performed through a medial longitudinal incision along the postero-medial region of the lower leg. The dissection went through the soleus and gastrocnemius muscle. The mass appeared capsulated, white, and glistening with 132 mm × 45 mm × 34 mm in size (Fig. 2). A final histopathologic examination of the completely excised mass was performed and the diagnosed of schwannoma Antoni A was established. The postoperative course was uneventful without neurological deficit. Ethical approval was permitted by the procedure of surgery and consent form of our institute, University Medical Center, Ho Chi Minh city.

Fig. 2.

Schwannoma tumor after resection.

3. Discussion

3.1. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs)

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors are common neoplasm with different biological features ranging from benign to malignant. Current classification includes: benign tumors (neurofibromas, schwannomas, perineuriomas, and hybrid tumors); malignant tumors (classical malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, epithelioid cell malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and perineural malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors); and a recently added category of tumors with uncertain malignant potential (atypical neurofibromatous neoplasm with uncertain biologic potential in NF1 patients) [2].

3.2. Schwannoma

Schwannomas, also known as neurilemmomas, are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors that derived almost entirely from Schwann cells. Of all nerve sheath tumors, schwannomas occur in about 89 % of cases with the most common site in vestibular accounting for 60 % of cases. About 32,6 % of schwannomas take place in the extremities [3,4]. Schwannomas are solitary, isolated, well-capsulated and sporadic in 90 % of all cases with 10 % of schwannomas occur at multiple sites. These cases are considered systemic due to genetic abnormalities in conditions such as neurofibromatosis type 2, Schwannomatosis, and Carney complex [5]. Schwannomas usually range from 2 cm to 20 cm in size with the majority of them smaller than 5 cm. Those larger than 5 cm are referred to as giant schwannomas [6]. When localized in the lower legs, the maximum length is typically less than 10 cm [7].

The capsule of schwannomas is comprised of three layers: the epineurium, the perineurium from the nerve bundle of origin, and the pericapsular tissue that may contain nerve fibers. The tumor capsule is often covered by tortuous blood vessels. Axons are not usually present within the tumor, which allows schwannomas to be removed without damages to the underlying nerve fascicles [8].

Clinical presentation of schwannomas is unclear and unspecific. Symptomatic schwannomas in the lower extremity are very rare. A schwannoma is suspected when an isolated, palpable, low-growing and positive-Tinel mass in the extremity is present. Neurologic symptoms such as altered sensation or motor weakness occur when the mass compresses the adjacent nerve. Pain in schwannoma is typically results from compression of the adjacent nerve as the schwannoma mass limits surrounding venous flow and antegrade and retrograde nerve transfer leading to Wallerian degeneration [9].

Beside clinical features, diagnosis of schwannoma relies on MRI findings. Tumors often demonstrate an eccentric mass near the affected nerve in a well-defined capsule with homogenous isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted images and high intensity on T2-weighted images. Intramuscular mass may be surrounded by fat that can create the “split fat sign” on T1-weighted images on the long axis of the affected limb. The “target signs” is noticed in 50 % of cases which has central low-intensity signal and peripheral high-intensity signal due to zonal effect from centrally localized fibrous tissue and peripherally localized myxoid material [10].

From nerve origin, schwannomas are classified into three types. The first type originates in the major nerve located intermuscularly which can be symptomatic. The second is from the minor superficial sensory branch located subcutaneously. The third originates from bundles of the intramuscular motor nerve. The latter two types are usually asymptomatic. This classification system is useful for preoperative diagnoses and could inform the choice of operative procedures as surgical excision of the major nerve type may cause neurological deficit [11,12].

In clinical presentation, schwannoma may be confused with other tumors like lipoma, neurofibroma, ganglion and xanthoma and other PNSTs because of the soft, swelling, palpable and well-capsulated mass in which Tinel sign is not clear. Histologic evidence is the gold standard in confirming schwanomma and differentiating from other tumors, especially other peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Immunohistochemical staining of S100 protein can help to confirming the diagnosis of schwannoma and excluding neurofibroma and malignant tumors of the peripheral nerve sheath [2]. Unfortunately, S100 protein staining was not performed in our case.

The size of tumor ranges from 2 cm to a 20 cm. The largest schwannomas are usually located in the mediastinum and retro-peritoneum. When located in the extremities, a maximum diameter of 10 cm is described in most studies. Hagiwware et al. reported a case with a tumor of 20 cm × 15 cm × 12 cm in diameter in 52 a year old female [13]. Maleux el al reported a case of a schwannoma tumor with the largest diameter of 25 cm in lower leg [7]. Here, we report a case in which the size of tumor was 13.2 cm × 4 cm × 3.4 cm.

3.3. Treatment options

Resection of schwannomas is symptom-dependent. Small schwannomas are resected with routine tumor resection procedure. If the diagnosis is not clear, a biopsy is performed through extra-capsular technique or simple excision. Tumor resection of larger schwannomas, especially ones involving major nerve, must be careful performed due to the risk of postoperative neurological deficit. Therefore, if the diagnosis is confirmed by MRI and the patient is asymptomatic, a conservative treatment is recommended.

3.4. Surgery and outcome

There are two main approaches in resecting schwannomas: extra-capsular and intra-capsular enucleation. However, recent studies reported neurological deficit in nearly 70 % of cases [15]. Some researchers have suggested a modified microsurgical technique with palliative, intra-capsular enucleation, which is safer for nerve fascicles and minimizes complications [16]. Intra-capsular excision has been reported to reduce the neurological complication compared to extra-capsular excision with major deficit observed in only 3 % of cases. To date, controversies remain for whether a tumor location and size, and duration and severity of symptoms are indicators for neurological deficit after surgery [15]. Benign nerve tumors include neurofibromas and schwannomas. Complete excision of the neurofibroma may lead to damages to the original nerve because nerve fibers are embedded in the tumor. Schwannomas, which arise from the neural sheath, are well encapsulated allowing for surgical enucleation with little or no damages to the underlying nerve fibers. Nevertheless, Oberle et al. reported immediate postoperative sensory deficits in six of 12 patients [17]. Donner and colleagues reported that 13 % schwannomas in their series developed muscle weakness postoperatively [18]. The size of the tumor is one of the factors that can predict neurological deficit with patients with larger tumors more likely to develop neurological deficit.

3.5. Postoperative follow-up

Fortunately, our patient underwent uneventful postoperative course. He feels comfortable without the swelling mass, and he did not suffer any more pain. His neurologic function in lower leg is normal. In fact, due to the large size of tumor, some complication may occur including: hematoma, neurologic deficit and malignant transformation. Because of eccentric location, noninfiltrating growth, excising schwannomas will cause no or little damage to neurologic structure unless it is related to major nerve or aggressive tumor removal surgery [8].

The recurrence rate after tumor excision is rare, even in cases of partial resection [19]. Malignant transformation is rare and has yet been reported in the current literature [20]. In our case, because of extracapsular total removal of the tumor, the change of recurrence and malignant transformation can be very low.

4. Conclusion

Schwannomas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors that derived almost entirely from Schwann cells. The size of schwannomas ranges from 2 to 20 cm. The largest schwannomas are usually located in the mediastinum and retro-peritoneum. When located in the extremities, a maximum diameter of 5 cm is described in most studies. Ultrasound and MRI are valuable for initial diagnosis but only a histo-pathological analysis can provide a definitive diagnosis. The recommended treatment of schwannoma is surgical enucleation or resection without damaging the involved nerve.

Ethical approval

This study in our institution was in normal procedure with surgery consent form. The patient's guardian provided appropriate consent before the surgery.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the work, authorship, and/or publication of this report.

Guarantor

Vinh Pham Quang MD, PhD.

Research registration number

-

1.

Name of the registry: None

-

2.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: None

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration: None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Vinh Pham Quang: conceptualising the plan for surgery, performing the surgery, reviewing the manuscript

Huy Hoang Quoc: Assisting in planning and in the surgery, writing the literature review for case report,

Bach Nguyen: Assisting the surgery, writing the draft for case report

Chuong Ngo Quang: taking note and data visualisation perioperatively

Hieu Nguyen Chi: Assisting the surgery, prepare the neccessary equipments

Ngoc Nguyen: Analyzing the radiology and MRI.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no financial or personal relationship with other entities that could inappropriately influence this study.

Contributor Information

Vinh Pham Quang, Email: vinhpham03@ump.edu.vn.

Huy Hoang Quoc, Email: huy.hq2@umc.edu.vn.

Bach Nguyen, Email: bach.n@umc.edu.vn.

Chuong Ngo Quang, Email: chuong.nq@umc.edu.vn.

Hieu Nguyen Chi, Email: hieu.nc2@umc.edu.vn.

Ngoc Nguyen, Email: nngoc.nt18@ump.edu.vn.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Kerwan A., Thoma A., Beamish A.J., Noureldin A., Rao A., Vasudevan B., Challacombe B. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Dec 1 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magro G., Broggi G., Angelico G., Puzzo L., Vecchio G.M., Virzì V., Salvatorelli L., Ruggieri M. Practical approach to histological diagnosis of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: an update. Diagnostics (Basel) Jun 14 2022;12(6) doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12061463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou H., Jiang S., Ma F., Lu H. Peripheral nerve tumors of the hand: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. World J. Clin. Cases. 2020;8:5086–5098. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Propp J.M., McCarthy B.J., Davis F.G., Preston-Martin S. Descriptive epidemiology of vestibular schwannomas. Neuro-Oncology. Jan 2006;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1215/S1522851704001097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito S., Suzuki Y. Schwannomatosis affecting all three major nerves in the same upper extremity. J. Hand Surg. Eur. 2010;35:592–594. doi: 10.1177/1753193410369284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritt M.J., Bos K.E. A very large neurilemmoma of the anterior interosseous nerve. J. Hand Surg. (Br.) 1991;16:98–100. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(91)90141-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maleux G., Brys P., Samson I., Sciot R., Baert A.L. Giant schwannoma of the lower leg. Eur. Radiol. 1997;7(7):1031–1034. doi: 10.1007/s003300050247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D.H., Murovic J.A., Tiel R.L., et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J. Neurosurg. 2005;102:246–255. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siqueira M.G., Socolovsky M., Martins R.S., et al. Surgical treatment of typical peripheral schwannomas: the risk of new postoperative deficits. Acta Neurochir. 2013;155:1745–1749. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woertler K. Tumors and tumor-like lesions of peripheral nerves. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. Nov 2010;14(5):547–558. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1268073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimose S., Sugita T., Kubo T., et al. Major-nerve schwannomas versus intramuscular schwannomas. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:672–677. doi: 10.1080/02841850701326925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ujigo S., Shimose S., Kubo T., et al. Therapeutic effect and risk factors for complications of excision in 76 patients with schwannoma. J. Orthop. Sci. 2014;19:150–155. doi: 10.1007/s00776-013-0477-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagiwara K., Higa T., Miyazato H., Nonaka S. A case of a giant schwannoma on the extremities. J. Dermatol. Nov 1993;20(11):700–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1993.tb01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park M.J., Seo K.N., Kang H.J. Neurological deficit after surgical enucleation of schwannomas of the upper limb. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Br.) 2009;91:1482–1486. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B11.22519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Date R., Muramatsu K., Ihara K., et al. Advantages of intra-capsular micro-enucleation of schwannoma arising from extremities. Acta Neurochir. 2012;154:173–178. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberle J., Kahamba J., Richter H.P. Peripheral nerve schwannomas–an analysis of 16 patients. Acta Neurochir. 1997;139:949–953. doi: 10.1007/BF01411304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donner T.R., Voorhies R.M., Kline D.G. Neural sheath tumors of major nerves. J. Neurosurg. 1994;81:362–373. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.3.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senapati S.B., Mishra S.S., Dhir M.K., et al. Recurrence of spinal schwannoma: is it preventable? Asian J. Neurosurg. 2016;11:451. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.145060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakkouri W.E., Kania R.E., Guichard J.P., et al. Conservative management of 386 cases of unilateral vestibular schwannoma: tumor growth and consequences for treatment. J. Neurosurg. 2009;110:662–669. doi: 10.3171/2007.5.16836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]