Abstract

Introduction

This study reports an unusual experience of a mother who may have developed birth-related osteoporosis after each of the births of her two children.

Presentation of case

A 31-year-old woman presented with lumbar back pain. She had given birth to her first child through vaginal delivery 4 months prior and was breastfeeding. Magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple fresh vertebral fractures, but continued breastfeeding resulted in further loss of bone density. The bone mineral density recovered after weaning. The patient gave birth to a second child three years after the first child's birth. She opted to discontinue breastfeeding after the detection of repeated instances of significant bone loss. No new vertebral fractures have occurred in the 9 years since the patient's initial visit to our clinic.

Discussion

We describe a case where a mother experienced multiple episodes of rapid bone loss following childbirth. Bone health evaluation at an early stage following childbirth may be effective for preventing future bone fractures.

Conclusion

It is desirable to develop a team and guidelines for treating osteoporosis associated with pregnancy and lactation and for the next pregnancy and delivery.

Keywords: Childbirth-related osteoporosis, Osteoporosis, Weaning, Compression fractures, Pregnancy- and lactation-associated osteoporosis

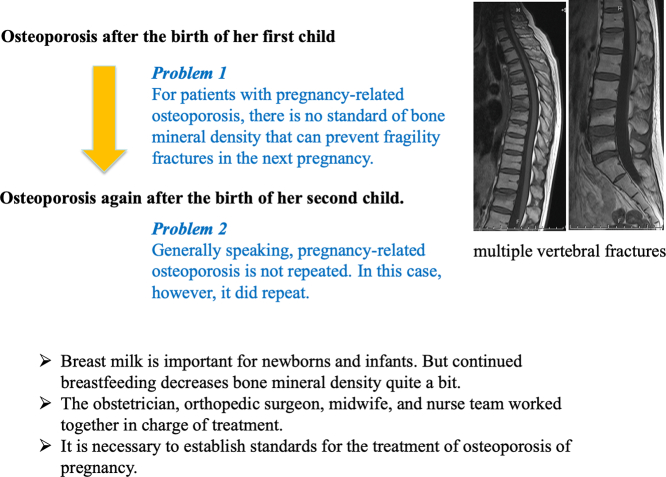

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We report a case of PLO with the first and second children consecutively.

-

•

Breastfeeding needed to be stopped to reduce the loss of bone mineral density.

-

•

PLO needs obstetricians and orthopedic surgeons for treatment and mental follow-up.

-

•

In PLO, treatment methods and criteria to permit the next pregnancy are needed.

1. Introduction

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 Criteria [1]. Normal pregnancy and lactation may cause temporary loss of bone density. Loss of maternal calcium during late pregnancy and lactation can lead to birth-related osteoporosis [2]. In pregnant women, calcium is absorbed from the intestinal tract and transported to the fetus [3]. During lactation, calcium absorption in the maternal intestinal tract is normal. However, maternal bone density is reduced through osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and osteocytic osteolysis, which supply the bulk of the calcium in breast milk [4].

As bone mineral density recovers spontaneously, pregnancy-related osteoporosis is rare [5,6]. In Japan, the frequency of childbirth-related osteoporosis is approximately between 0.3 and 0.03% [7]. Repeat pregnancy-related osteoporosis is even less common [8]. In patients with multiple pregnancies, pregnancy- and lactation-associated osteoporosis (PLO) may be present in one pregnancy but absent in others [9,10]. We report the case of a mother with pregnancy-related osteoporosis after the birth of both the first and second children.

2. Presentation of case

A 31-year-old Japanese woman presented with lumbar back pain. She had worked in the airline industry as a flight attendant for 8 years. No abnormalities were detected in the company's physical examination.

2.1. Past history

There were no fragility fractures.

2.2. Family history

The family history was unremarkable.

2.3. Current medical history

The patient gave birth to their first child 4 months prior through vaginal delivery. Three months after giving birth, the patient experienced severe back pain with a throbbing sensation. The patient visited a local orthopedic surgeon. A simple X-ray revealed compression fractures of the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae. As this was a case of a compression fracture in a young patient, a referral was made to our clinic at 4 months postpartum, at which point the patient was still breastfeeding.

2.4. Physical findings

The patient's height, weight, and body mass index were 160.9 cm, 49.4 kg, and 19.1 kg/m2, respectively. No blue sclera was observed on the ocular conjunctiva suggesting osteogenesis imperfecta. The patient's upper and lower extremity musculature was normal, and no pathological reflexes were observed.

2.5. Blood biochemistry

Blood laboratory parameters were as follows: albumin level, 4.7 g/dL; calcium level, 9.3 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase level, 333 IU/L; tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase isoform 5b level, 728 mU/dL (normal range: 120–420); bone alkaline phosphatase level, 27.9 u/L (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bone mineral density and bone metabolic markers.

| Progress since initial visit | −4 M | 0 M | 5th M | 6th | 10th M | 29th M | 42th M | 48th M | 49th | 56th M | 72th M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Birth of the first child | Initial medical examination | Weaning off | Birth of the second child | Weaning off | ||||||

| L-Spine BMD (g/cm2) | 0.498 | 0.444 | 0.481 | 0.602 | 0.630 | 0.555 | 0.646 | 0.657 | |||

| L-Spine YAM (%) | 49 | 44 | 48 | 60 | 62 | 55 | 64 | 65 | |||

| Hip BMD (g/cm2) | 0.496 | 0.451 | 0.470 | 0.489 | 0.561 | 0.496 | 0.529 | 0.553 | |||

| Hip YAM (%) | 63 | 57 | 60 | 62 | 71 | 63 | 67 | 70 | |||

| NTX (nMBCE/mMcr) | 148.1 | 102.3 | 59.4 | 33.6 | 45.5 | 77.8 | 31.0 | 27.7 | |||

| TRACP-5b (mU/dL) | 728 | 284 | 164 | 158 | 225 | 342 | 116 | 132 | |||

| BAP (μg/L) | 27.9 | 26.7 | 18.7 | 10.5 | 7.7 | 21.4 | 8.8 | 7.9 | |||

| ucOC (ng/mL) | 6.23 | 6.55 | 7.42 | 4.78 | 2.08 | 9.47 | 2.94 | 4.25 |

M, month; L-Spine, lumbar spine L2–4; YAM, young adult mean; BMD, bone mineral density; NTX, urinary cross-linked N-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen; TRACP-5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase isoform 5b; BAP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; ucOC, undercarboxylated osteocalcin. 14th month; getting back to work.

2.6. Imaging findings

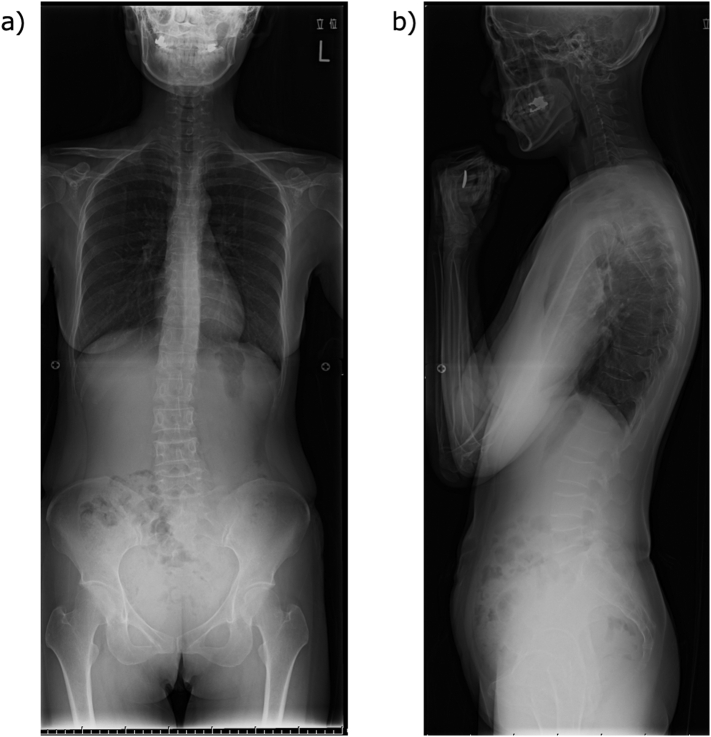

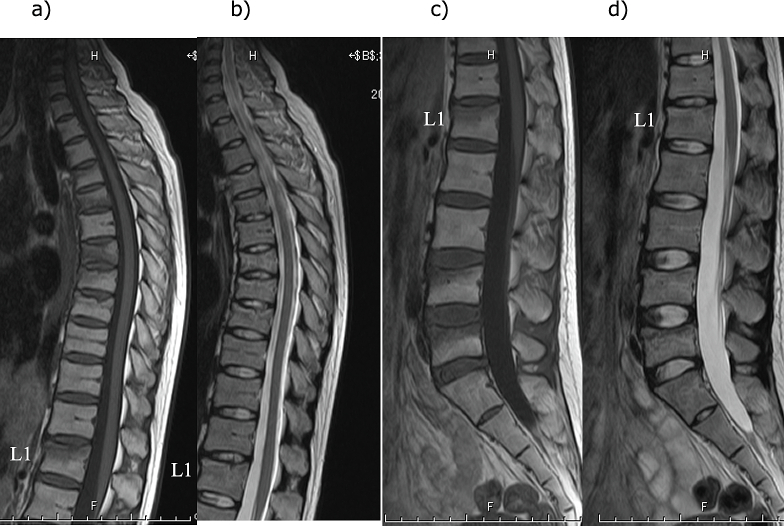

A simple X-ray showed multiple vertebral body deformities (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed T1 low and T2 high signals in the 4th, 5th, 7th, 8th, and 9th thoracic vertebrae and the 1st, 4th, and 5th lumbar vertebrae, indicating fresh multi-vertebral fractures (Fig. 2). Bone mineral density was assessed using dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Discovery DXA System; Hologic Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA). It was 0.498 g/cm2 (49 % young adult mean [YAM]) for the lumbar spine and 0.498 g/cm2 (63 % YAM) for the hip (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Simple X-ray of the whole spine

a) Frontal, b) Lateral

A wedge-shaped deformity is observed in the 5th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th thoracic vertebrae and the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae.

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging findings for the thoracic and lumbar spine

a) Thoracic spine T1-weighted image, b) Thoracic spine T2-weighted image, c) Lumbar spine T1-weighted image, d) T2-weighted image. L1: First lumbar vertebra

A wedge-shaped deformity is observed in the 5th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th thoracic vertebrae and the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae.

2.7. Progress

The patient continued breastfeeding for a month after the initial diagnosis of compression fracture until they were referred to our clinic. The patient and their partner did not agree to aggressive medical therapy because they were concerned about drug exposure to the infant through breast milk. Therefore, the patient was instructed to eat a calcium and vitamin D rich diet, sunbathe, and exercise regularly. The patient desired to continue breastfeeding. After explaining the risk of a new fracture, we respected the patient's decision to continue breastfeeding and monitored their progress. Five months later, DXA revealed a bone mineral density of 0.444 g/cm2 (44 % YAM) for the lumbar spine and 0.451 g/cm2 (57 % YAM) for the hip. The obstetrician/gynecologist was consulted, and the patient was administered cabergoline to stop milk production. The patient resumed work a year after giving birth.

Afterward, the bone density recovered naturally. When the lumbar YAM values recovered to 60 %, the patient was allowed to prepare for the next pregnancy. A second child was born 3 years after the first child's birth. The bone density immediately after delivery was 0.630 g/cm2 for the lumbar spine (62 % YAM) and 0.561 g/cm2 for the hip (71 % YAM). However, 6 months after breastfeeding, the bone density was 0.555 for the lumbar spine (55 % YAM) and 0.496 for the hip (63 % YAM), indicating a significant decrease even after the second delivery (Table 1). Given their experience with the first child, the patient consented to discontinue breastfeeding. Based on the experience of weaning her first child, she proceeded to wean her second child with cabergoline. No new vertebral fractures have occurred in the 9 years since the patient's initial visit to our clinic. As the patient did not wish to have a third child, alendronate and eldecalcitol were administered.

3. Discussion

We report a case of postpartum-related osteoporosis after the birth of the first child and again with a loss of bone mineral density after the second child's birth. Because of her experience with her first child, she was able to begin treatment for osteoporosis early after the birth of her second child.

Ying et al. systematically reviewed 65 studies on PLO [9]. In multiple pregnancies and deliveries, PLO may occur in the first pregnancy, but it may also occur for the first time in the second, third, or fourth pregnancy and delivery. They stated the following characteristics of PLO: over half of the cases occurred over the age of 30 years, the average body mass index (BMI) was 22.2 kg/m2, 94 % were breastfed, and the average vertebral fracture was 4.4 vertebrae [9]. This patient was also in her 30s, breastfed, and had a low BMI. She also had eight vertebral fractures, which was more than the average.

In Japan, osteoporosis is diagnosed when the bone mineral density ratio in young adult females is <70% [11]. The T-score represents the standard deviation of bone mineral density from the average bone mineral density of young adults. A T-score of −2.5 standard deviations and a YAM of 70 % are considered almost identical. In the present case, the patient was diagnosed with severe osteoporosis, with a YAM value of 50 %.

Breast milk provides nutrition and immunity to the infant [12] and bonding between mothers and children [13]. Although the doctor explained the risk of further vertebral fractures with continued breastfeeding, the mother's desire to continue breastfeeding after giving birth to the first child was prioritized. In general, women with postpartum osteoporosis should stop breastfeeding after diagnosis. In the present case, it took 14 days from the time the patient was first prescribed a drug to stop breast milk production until she took that drug. The 14 days were due to a mixture of the mother's desire to breastfeed and treat osteoporosis. In the case of pregnancy-related osteoporosis, a support system is needed to attend to the mother's feelings.

Osteoporosis after childbirth often results in spinal compression fractures in multiple locations, making physical movement difficult [14,15]. When husbands are also working, they often hesitate to have another baby because of the associated emotional and financial problems. There are no criteria for a subsequent pregnancy when osteoporosis occurs after a previous childbirth. In the present case, we advised the patient to have a second child after the lumbar spine bone density YAM value exceeded 60 %. Since bone density decreased by 5 % during the first child's lactation, we thought that a YAM value of 55 % would be acceptable, as it was 11 % more than the minimum YAM value of 44 %. Bone density should be increased as much as possible.

Bisphosphonates taken before or in early pregnancy do not cause teratogenesis [16]. Meanwhile, other side effects include a shorter gestational period, lower birth weight, and a higher rate of spontaneous abortion [16]. There are also concerns about bone accumulation and the effects of a subsequent pregnancy [17]; therefore, bisphosphonates were not administered in this patient. Recently, parathyroid hormones, denosumab, and anti-sclerosin antibodies have become available for osteoporosis treatment [5,18]. The body eliminates these antibodies; as immunoglobulin G antibodies have been reported to cross the placenta and to be secreted into milk, their administration should be discontinued before pregnancy [19]. Breastfeeding for the second child was continued for 6 months so the child could get the immune boosting benefits from the mother's milk [12], and then weaning was done.

We cooperated with our gynecology department to manage the patient and discontinue milk production. Osteoporosis is a systemic disease with various causes [20]. Therefore, our hospital usually holds conferences with various departments to improve cooperation and overall patient care.

A limitation in this case was the lack of data on the patient's bone density before delivery. Thus, we could not determine whether the bone density decreased during the first delivery, pregnancy, and lactation or it was originally low. However, the spine MRI showed multiple new vertebral fractures, indicating that the patient had multiple vertebral fractures during the post-pregnancy lactation period and very low bone density values. Regarding YAM values, bone mineral density was reduced by 5 % in the lumbar spine between 5 and 10 months after the first child's birth and by 6 % in the femoral neck. Soloria et al. conducted a systematic review of birth-related osteoporosis; they reported that bone mineral density decreases during the first 6 months of lactation and then gradually improves [21]. We recorded bone mineral density at 4 and 9 months postpartum, which may have decreased until the 6th month and spontaneously recovered in the 7th month. In that case, the YAM value of the lumbar spine at 6 months would have been even lower than 44 %. Karlsson et al. reported a 2.0 ± 1.0 % decrease in femoral neck bone mineral density 5 months postpartum (p < 0.001) and no further decrease between 5 and 12 months postpartum in mothers breastfeeding for 1–6 months [22]. We believe this case with over 6 % decrease in femoral neck bone mineral density at 9 months postpartum is unusual.

Guidelines for treating and managing postpartum osteoporosis are awaited, including establishing criteria regarding the YAM values necessary to prepare patients with osteoporosis associated with prior childbirth for the next birth in relative safety and recommended treatment methods. A medical team should be established to address the concerns of such patients and their families.

4. Conclusion

Bone health evaluation at an early stage after childbirth may be effective for preventing future fractures.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of the Showa University School of Medicine, to which the author belongs, does not require ethics review for case reports of medical procedures performed within the normal scope of care, if written consent is obtained from the individual patient.

Funding

This work was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant Number 22K12896 and 22K11402. This work was supported by Joint International Research, Grant Number 22KK0265.

Author contribution

T.K.: Osteoporosis treatment consults

K.I.: Osteoporosis treatment consults

K.S.: Osteoporosis treatment consults

N.S.: Obstetrics and gynaecology treatment consults

Y.K.: Orthopaedic surgery treatment consults

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

The guarantors are Team Professor Yoshifumi Kudo and Osteoporosis team Professor Keizo Sakamoto.

Both are responsible as co-authors.

Research registration number

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

None.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Matthew Wurzer for English language editing.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Kerwan A., SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 Guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;(84):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardcastle S.A. Pregnancy and lactation associated osteoporosis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2022;110:531–545. doi: 10.1007/s00223-021-00815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitkin R.M. Calcium metabolism in pregnancy and the perinatal period: a review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1985;151:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacs C.S. In: Endotext [Internet] Feingold K.R., Anawalt B., Blackman M.R., Boyce A., Chrousos G., Corpas E., et al., editors. MDText.com, Inc.; South Dartmouth (MA): 2000. Calcium and phosphate metabolism and related disorders during pregnancy and lactation. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calik-Ksepka A., Stradczuk M., Czarnecka K., Grymowicz M., Smolarczyk R. Lactational amenorrhea: neuroendocrine pathways controlling fertility and bone turnover. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:1633. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magula N., DeVine D., et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess (Full Rep). 2007:1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurabayashi T., Morikawa K. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of post-pregnancy osteoporosis. Clin. Calcium. 2019;29:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith R., Athanasou N.A., Ostlere S.J., Vipond S.E. Pregnancy-associated osteoporosis. QJM. 1995;88:865–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qian Y., Wang L., Yu L., Huang W. Pregnancy- and lactation-associated osteoporosis with vertebral fractures: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021;22:926. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04776-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babbitt A.M. Post-pregnancy osteoporosis (PPO) J. Clin. Densitom. 1998;1:269–273. doi: 10.1385/jcd:1:3:269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orimo H., Nakamura T., Hosoi T., Iki M., Uenishi K., Endo N., et al. Japanese 2011 guidelines for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis–executive summary. Arch. Osteoporos. 2012;7:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s11657-012-0109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmeira P., Carneiro-Sampaio M. Immunology of breast milk. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 2016;(62):584–593. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.62.06.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malcolm R. Milk’s flows: making and transmitting kinship, health, and personhood. Med. Humanit. 2021;47:375–379. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2019-011829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim T.H., Lee H.H., Jeon D.S., Byun D.W. Compression fracture in postpartum osteoporosis. J. Bone Metab. 2013;20:115–118. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2013.20.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuroda T., Nagai T., Ishikawa K., Inagaki K. Pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis−a female who was discovered bone mineral density reduction in adolescence (in Japanese) J. Jpn. Osteoporos. Soc. 2016;2:143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ornoy A., Wajnberg R., Diav-Citrin O. The outcome of pregnancy following pre-pregnancy or early pregnancy alendronate treatment. Reprod. Toxicol. 2006;22:578–579. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yun K.Y., Han S.E., Kim S.C., Joo J.K., Lee K.S. Pregnancy-related osteoporosis and spinal fractures. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2017;60:133–137. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles B., Panchbhavi M., Mackey J.D. Analysis of fracture incidence in 135 patients with pregnancy and lactation osteoporosis (PLO) Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.19011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka N., Nishimura T. Risk-benefit balance evaluation of new monoclonal antibodies for use in pregnant women (in Japanese) Reg. Sci. Med. Prod. 2018;8:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanis J.A., Cooper C., Rizzoli R., Reginster J.Y. Scientific advisory Board of the European Society for clinical and economic aspects of osteoporosis (ESCEO) and the committees of scientific advisors and National Societies of the international osteoporosis foundation (IOF). European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2019;30:3–44. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salari P., Abdollahi M. The influence of pregnancy and lactation on maternal bone health: a systematic review. J Family Reprod Health. 2014;8:135–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson C., Obrant K.J., Karlsson M. Pregnancy and lactation confer reversible bone loss in humans. Osteoporos. Int. 2001;12:828–834. doi: 10.1007/s001980170033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]