Abstract

Stock markets are generally perceived as a barometer of the economy and respond to international monetary policies even before economic activities. Many central banks have turned to unconventional policy measures in response to various financial crises such as the global financial crisis of 2007–2009 or the recent crisis caused by COVID-19. To examine the cross-correlation of overall international monetary policies with stock markets, we employ the daily shadow short rate (SSR), which has the advantage of allowing comparison across unconventional and conventional regimes. The analysis is made through a multifractal context using multifractal detrended cross correlation analysis (MF-DXA), considering daily data from 1st January 2000 to 31st March 2022 and country specific SSR and the stock markets of eight developed economies. The main empirical findings are the following: (i) all the country specific pairs of SSR with stock markets have significant multifractal characteristics (ii) the pairs of NZ-SSR/NZX50, US-SSR/DJIA, and CN-SSR/S&P TSX have the highest multifractal patterns while EU-SSR/Euro-area Index has the lowest multifractal patterns (iii) Australian and New Zealand stock markets exhibit anti-persistent cross-correlation with SSR while the remainder have persistent cross-correlation in their multifractality. Lastly, the findings of this study have several important implications for central banks and stock market participants.

Keywords: Monetary policy, Shadow short rates, SSR, Stock markets, MF-DXA, Cross correlation

Highlights

-

•

We analyze cross-correlation between shadow short rate (SSR) and stock markets.

-

•

We use multifractal detrended cross correlation analysis (MF-DXA), with daily data.

-

•

We find evidence of multifractal characteristics in the variables under analysis.

-

•

Persistent cross-correlation is found between shadow short rate (SSR) and stock markets.

1. Introduction

Financial markets were greatly affected by the 2007–2009 global financial crisis (GFC), which began with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers and led to the worst economic crisis since the great depression of the 1930s [1,2]. Bound between the choice of growth and inflation under Taylor Rule [3], central banks had to react. In response, many central bank authorities employed conventional as well as unconventional monetary policy (UMP) measures with the intention of reducing the impact on the real economy and achieving financial stability. Conventional monetary policy (CMP) measures usually involved open market operations to manipulate short-term interest rates. However, CMP measures have a zero lower bound (ZLB) limitation for these short-term interest rates. As a result, several monetary and fiscal policymakers worldwide pushed their policy rates to the ZLB, but were still unable to accelerate the economy into meaningful recovery [4]. In these situations, where CMP measures cannot be applied because of the liquidity trap, central banks attempt to apply UMP measures, which initially were of two types.

The central banks first launched Forward Guidance (FG), which tries to advise market players about the future course of policy rates [5]. This is separated into two categories: state-based guidance and calendar-based guidance. According to state-based guidance, central banks do not raise policy rates until a set of economic criteria is met. For instance, the Bank of England (BoE) stated in August 2013 that rates would remain low until the unemployment rate reached 7%, while the Bank of Japan (BoJ) stated in October 2010 that it would keep rates low until “price stability is in sight” [6]. Similarly, with calendar-based guidance, authorities do not increase rates until a specific date. However, FG was not a particularly novel approach, because various central banks offered guidance before GFC, such as the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), frequently since 1997, or the Federal Reserve System of US (Fed), more infrequently, from 2003 to 2005 [1]. What was novel was that, with policy rates frozen at historically low levels, central banks made considerable use of information about their plans for future monetary policy, giving the private sector clear knowledge of how borrowing costs would probably change over time.

Quantitative Easing (QE), was the second UMP tool used by central banks. It featured large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) made by buying long-term government bonds. These unprecedentedly massive asset purchases, however, resulted in very significant balance sheet expansions for central banks. For instance, before the beginning of the GFC, the Fed held less than $1 trillion in bonds. Then, with three different rounds of purchases, its balance sheet reached over $4 trillion [7]. According to the study by Potter and Smets [8], seven central banks reported using LSAPs between 2008 and 2017: BoE, BoJ, Fed, Bank of Mexico (BoM), the European Central Bank (ECB), Sveriges Riksbank (SR) and the Swiss National Bank (SNB). Interestingly, these LSAPs were also not brand new in GFC, since BoJ used QE and LSAPs in the early 2000s as a result of the collapse of the housing and stock market bubbles as well as the Japanese banking sector crisis [1]. Both QE and FG are operative to ease the financial condition when policy rates hit the lower bounds, even when financial markets function normally. Moreover, these tools will be more effective in the future and should remain a part of central banks’ tool kit. However, if neutral rates become lower, overcoming the lower bounds may need additional measures such as a reasonable increase in the inflation target or reliance on fiscal policy to stabilize the economy [9]. Additionally, to amplify liquidity for financial institutions, central banks expanded and added new lending facilities: decreased interest below zero (e.g., Danmarks Nationalbank – DN – ECB, SR, SNB and BoJ), expanded the range of accepted collateral (e.g., ECB), and extended the liquidity operation’s maturity – from weeks to years (e.g., BoJ), among others [1,8,10]. These actions assisted overburdened financial intermediaries in extending credit to the real economy and removing bottlenecks in the transmission of policy.

Similarly, the recent COVID-19 outbreak also changed the global outlook, causing the global median GDP to decline by 3.9% from 2019 to 2020 [11], which prompted many central banks to use UMP measures, including supplying liquidity to financial markets of equity and bonds (US and China), buying bonds and securities whose values were rapidly falling (EU, Australia, and Canada), lowering interest rates (US, Canada, South Korea, Nigeria, UK, Japan, New Zealand, and Turkey), and providing banks, SMEs, the public health sector, individuals and essential businesses with a steady flow of credit (US, UK, Nigeria, and Australia), among others [12].

According to Cecioni, Ferrero [13], the implementation of monetary policies especially during crisis and turmoil, is a considerably complex issue, since disturbances in financial markets can seriously harm the transmission mechanism. Firstly, the central bank's ability to regulate short-term interest rates may suffer due to the rise in reserve demand volatility and the constrained redistribution of liquidity among depository institutions. Secondly, the transmission of monetary impulses across the entire range of financial markets could be hampered by disruptions in other financial market segments. Finally, the ZLB on interest rates may turn into a legally binding constraint for monetary policy decisions if the crisis’ impact on the real economy is significant. Hence, to restore control of the economy under these circumstances, central banks may be forced to use UMP tools. Although the primary goal of the UMP measures was to stabilize the financial markets, additional policy measures were subsequently put in place to stimulate the real economy [14]. Hence, some of the immediate risks to financial markets and the global economy have been reduced because of these UMP tools [15]. Thus far, however, there is little evidence of the impact of UMP on financial markets.

Financial markets could be impacted by UMP through four different channels. Firstly, the central bank buys treasury securities through channels that affect portfolio balance, which changes the relative valuation of other replacement assets and boosts demand for them [16]. Secondly, since UMP measures are thought to act as a signaling channel, future lower policy rates are anticipated. Thirdly, in terms of confidence, as the markets may believe that the UMP measures' release will indicate that the economic and financial outlook is worse than what is already priced in Ref. [17]. Fourthly, by eliminating risky assets from private portfolios and lowering risk premia, UMP actions boost market liquidity [18].

In terms of the stock markets, an abrupt decrease (increase) in the policy rate corresponds to an increase (decrease) in stock prices [19]. The sources driving these market reactions are, however, less well understood. The dividend discount model suggests that monetary policies affect stock markets in two ways: (i) investors' expectations of future cash flows are affected by monetary policy measures, (ii) the real interest rate, which is used to discount future cash flows, or the risk premium related to holding stocks, is also affected by monetary policy actions [[20], [21], [22]]. Galí and Gambetti [23] claimed that GFC has shaken up the conventional belief regarding the relationship between monetary policies and stock prices. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused more harm to people and the economy than the GFC did [24,25]. Hence, it is crucial for monetary policy decision-makers, central bankers, financial market participants, investors and scholars to examine the relationship between financial markets and monetary policy initiatives. Financial market participants, for instance, need this information for effective investment decisions, whereas monetary policy makers must understand the real impact of their policy actions on stock markets to maintain price stability.

A great deal of empirical research examines how UMP measures affect financial markets. The initial research was concentrated on analyzing UMP’s effects in Japan because the BoJ was the first central bank to employ these tools. Kampl [26] divides the overall literature examining the impact of UMP measures in two streams: long-term and short-term effects. The first stream of literature examines the long-term impacts of UMP measures on individual countries’ inflation rate and GDP growth, especially in the eurozone, through two types of econometric approaches i.e., equilibrium-based models and vector autoregressive (VAR) based models. For example, Zabala and Prats [27] used a structural vector autoregressive model to analyze the performance of UMP measures on economic growth and inflation. The second stream of literature, on the other hand, uses event-based models and VAR based models, to examine the short-term impact of UMP measures on several financial markets. For instance, Fausch and Sigonius [19] use event study based methodology to determine how German stock markets are impacted by CMP as well as UMP measures employed by ECB. According to their findings, the general volatility in German stock markets primarily indicates the revisions to dividend expectations, and the stock market's reaction to monetary policy shocks depends on the current interest rate regime. Ferreira and Serra [28] use the same methodology and examine how the prices of European securities markets respond to policy announcement dates between 2008 and 2018. Their results show little evidence of international spillovers. However, the impact on European government bonds is mixed, while it is favorable and large for stock markets. Using event methodology, Kubota and Shintani [29] investigate the monetary policy surprise announcement by the Bank of Japan (BOJ) on asset prices. According to their results, monetary tightening surprise shows a negative effect on stock returns and a positive effect on government bond yields. Moreover, longer term yields respond more than short-term yields. Similarly, to understand the impact of policies on financial markets during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, Wei and Han [25] used event methodology and found weak transmission of policies to financial markets during COVID-19. However, the UMP measures were found to be effective for stock and forex markets. Recently, it is reported that interest rate channels work similarly in recession and expansion CMP but the effect diminishes in ZLB. However, credit channels work well in recession during CMP and operated equally during both recession and expansion at the ZLB [30].

VAR models, on the other hand, are found to be more efficient than event study based methodologies, since they take into consideration the problem of endogeneity of monetary policies [26]. Cepni, Gupta [31] investigate how the shocks of CMP and UMP measures impact the eight developed equity markets of US, UK, Spain, Italy, Germany, France and Canada by employing panel-based VAR with monthly data. Abdullah and Hassanien [32] used a structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) model to investigate the spillover effect of US UMP on Egypt as an emerging market case study. According to their findings, US UMP significantly affects Egyptian monetary policy, but the effect on other macroeconomic variables is weak. The findings confirmed that emerging countries such as Egypt are greatly affected by federal funds rates. Other studies used structural factor-augmented VAR [33], Qual VAR [34] time-varying coefficients VAR [23], smooth transition vector autoregressive (STVAR) [16], Time-Varying Parameter VAR (TVP-VAR) [35] or actor-augmented VAR (FAVAR) [36], among others.

The underlying dynamics of unconventional policies as well as most financial markets such as stock markets are significantly complex [13,37]. Considering the Euro area, Petrakis [38] confirmed that both CMP and UMP have a positive lagged impact on euro equity market returns. The findings showed that market indices are mainly affected by a cut in interest rates. In addition, core Eurozone countries which were less affected by the crisis showed a strong effect of non-conventional measures. Their results also confirmed the negative relationship between inflation rates and market returns. However, it is still unclear how the complexity of these policies affects complex financial markets. General mathematical models or Gaussian distribution-based models are unable to identify complex, non-linear and non-stationary relationships between time series. Mostly, these conventional statistical techniques only look at times series over a single scale and ignore aspects over multiple time scales. For instance, the earliest researchers used the assumption that dependence was similar to correlation. However, in the 1980s, this perspective was questioned because of high order temporal dependence detection. In the same context [39], claimed that using linear equations means other types of dependence are not revealed. As a result, there could be some misconceptions about monetary policy measures’ connection with stock markets, which would explain the contradictory results of earlier research. Unconventional methods, on the other hand, examine the statistical properties at all scales, which makes them useful for studying the behavior of non-linear systems like UMPs and financial markets. For instance, the use of fractal-based techniques focuses on the division of a time series into components that are self-similar and investigation of the power-law behavior that depicts the scaling properties of the time series under study. Hence, we aim to address this gap by examining the cross-correlation of unconventional monetary policies with stock markets in a multifractal context.

Over the past twenty years, various multifractal methods have been developed and applied to many complex systems, such as physics, chemistry, biology, music, ecology and geology, as well as many financial markets. Rescaled range analysis (R/S), also referred to as the weighting pole method, was the first robust nonparametric technique proposed by Hurst [40], to differentiate fractal time series from random time series. Later, Lo [41] presented a modified version of the R/S method since the conventional R/S method could not distinguish between long and short-term correlations, and was sensitive to sample length. Later, Peng, Buldyrev [42] introduced the detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) to address this flaw by utilizing long-range power-law correlation and relaxed the tight criterion of a short-range correlation. Kantelhardt, Zschiegner [43] went on to develop the multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis (MF-DFA), a multifractal version of DFA. Kantelhardt, Zschiegner [43] explained two possible reasons behind these multifractal characteristics: (i) long-range correlations of both small and large fluctuations, (ii) the broad probability density function for the series’ values. Since then, DFA and MF-DFA methods have frequently been used to investigate the long-range memory, persistent behavior, and herding behavior of many financial markets, such as stock markets [44], energy markets [45], commodity markets [46], cryptocurrency markets [47], and others.

In many cases, multiple variables are measured at the same time, and these measurements exhibit multifractal behavior or long-range dependence. In light of this, Podobnik and Stanley [48] extended DFA to measure power cross-correlations between two non-stationary time series and proposed detrended cross-correlation analysis (DXA or DCCA). Numerous scientific disciplines, including finance, physics and earth sciences, have used their methodology [44,[49], [50], [51]]. This concept was then expanded upon by Zhou [52], who combined DXA with MF-DFA and proposed a new method named multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis (MF-DXA or MF-DCCA), which attracted significant attention in the literature. Aslam, Bibi [53], for example, used MF-DXA to investigate the cross-correlation of economic policy uncertainty with industrial and precious metals. Maghyereh, Abdoh [54] used the same method to investigate how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the cross-correlations between US stock markets and gold.

Based on the above, this article examines the cross-correlation of unconventional monetary policies with stock markets in a multifractal context and contributes to the existing literature in three ways. Firstly, unlike other studies, we used the daily shadow short rate (SSR) by Krippner [55] and Krippner [56], since many studies highlight the importance of its high frequency for the validity of results. SSR is the nominal interest rate that would prevail in the absence of its effective lower bound. These shadow rates correspond to policy rates in normal times and are free to go into the negative zone when policy rates hit their lower bounds. Here, Claus, Claus [57] and Francis, Jackson [58] suggested that shadow rate captures the effect of monetary policy in critical times in the same way that policy rate does in normal times. Hence, this synthetic indicator provides a common metric for the monetary policy stance, so it also has the advantage of allowing comparison across conventional and unconventional regimes. This provides a guideline to the policy-maker that if a strong relationship is identified between SSR and stock market in times of distress or unconventional regimes, the SSR can be an indicator of their effect on the economy in evaluating the trade-off under the Taylor rule [3]. Hence zero bound rates do not become a hurdle in evaluating the trade-off. Secondly, using the framework of the fractal market hypothesis (FMH), we present the first study on the cross-correlation of unconventional policies i.e., SSR with stock markets. In addition, we use the large daily dataset of over 21 years for country specific SSR and the stock markets of eight developed economies: US, Euro Area, Japan, Switzerland, New Zealand, Canada, Australia and UK to conduct a more comprehensive analysis. Note that the choice of these equity markets is primarily motivated by their importance in the global economy. Hence, global spillover could have been witnessed because of any potential change in their growth, monetary and fiscal policies or uncertainty in their financial and economic policies [59,60]. Thirdly, we employ the multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis (MF-DXA) of Zhou [52] (using R language) to understand better the cross-correlations’ inner dynamics from a multifractal perspective while taking into account the dynamic, non-linear, chaotic and fractal nature of stock market returns and SSR.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the data and methodology we used. Section 3 presents the detailed empirical results, and finally, Section 4 contains our conclusion and discussion.

2. Data and methodology

2.1. Data

We used the daily data of shadow short rates (SSR) and stock market indices of eight economies from 03-Jan-2000 to 31-Mar-2022. The list of SSR and stock market indices are shown in Table 1, Table 2, respectively (see Appendix A for the list of acronyms used in the paper). The SSR accurately characterizes monetary policy attitudes in times of "near-zero" or "zero" policy rates because they are synthetic indicators of not only CMP but also UMP measures [55,61,62]. Compared to three-factor shadow/lower-bound term structure model SLMs, two-factor SLMs are more reliable for estimating SSR globally [56]. We obtain the daily closing stock market prices from DataStream, while the data for SSR series are collected from the website of Dr. Leo Krippner and LJK Limited (https://www.ljkmfa.com/). For computational purposes, we calculate the daily returns as the first differences of the logs of two consecutive values of SSR and stock market indices.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of shadow short rates (SSR).

| US | Euro-area | Japan | UK | Switzerland | Canada | Australia | New Zealand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.8441 | 0.4457 | −1.9881 | 1.2649 | −0.3384 | 1.6045 | 3.2190 | 3.3265 |

| Minimum | −4.1694 | −4.4688 | −6.0578 | −5.1589 | −4.7162 | −1.6046 | −3.2810 | −4.0337 |

| Maximum | 6.8722 | 5.0452 | 0.6743 | 6.1215 | 3.6357 | 6.2693 | 7.3564 | 8.3264 |

| Standard Deviation | 2.5672 | 2.4472 | 1.4473 | 2.8234 | 1.9933 | 1.7446 | 2.3888 | 2.6323 |

| Skewness | 0.3126 | 0.1594 | −0.2235 | 0.0299 | 0.1672 | 0.6676 | −0.6068 | −0.2190 |

| Kurtosis | −0.4447 | −1.2729 | −0.3041 | −1.0116 | −0.9399 | −0.1673 | −0.0936 | −0.1799 |

| Count | 5595 | 5632 | 5228 | 5363 | 5603 | 5587 | 5673 | 5358 |

Table 2.

Summary statistics of stock market returns.

| DJIA | Euro-area Index | Nikkei 225 | FTSE 100 | SMI | S&P TSX | S&P ASX 200 | NZX 50 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 |

| Minimum | −0.1293 | −0.1130 | −0.1141 | −0.1087 | −0.0964 | −0.1234 | −0.0970 | −0.0764 |

| Maximum | 0.1137 | 0.1205 | 0.1415 | 0.0984 | 0.1139 | 0.1196 | 0.0700 | 0.0718 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.0119 | 0.0151 | 0.0147 | 0.0118 | 0.0115 | 0.0111 | 0.0101 | 0.0073 |

| Skewness | −0.1130 | −0.0064 | −0.1737 | −0.1669 | −0.1258 | −0.6457 | −0.5768 | −0.4808 |

| Kurtosis | 12.8038 | 5.8882 | 6.3217 | 8.1295 | 7.8953 | 16.2249 | 7.8850 | 8.6839 |

| Count | 5594 | 5631 | 5227 | 5362 | 5602 | 5586 | 5672 | 5357 |

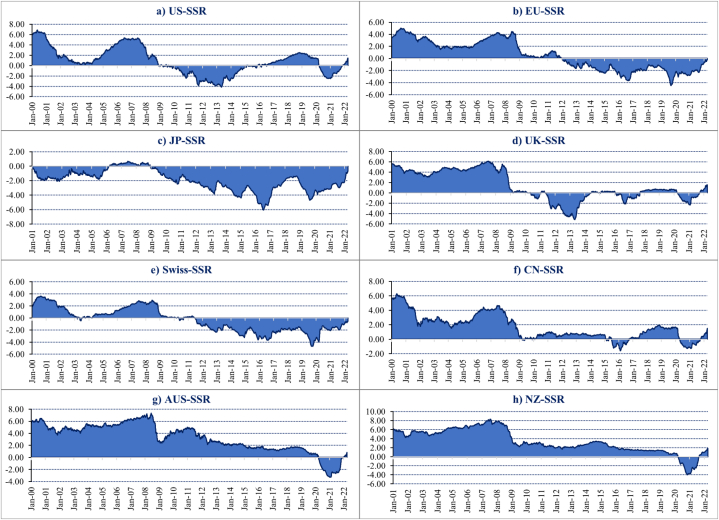

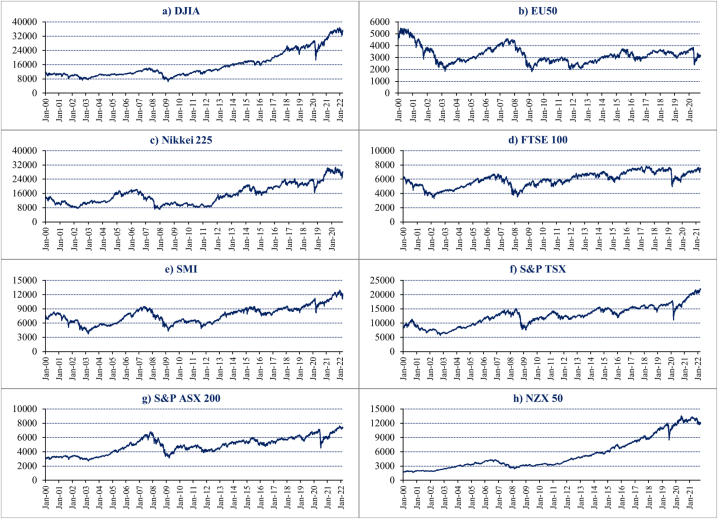

The descriptive statistics for shadow short rates are summarized in Table 1. As can be seen, six of the eight economies have positive average shadow short rates while the average shadow short rate in Japan and Switzerland remained negative in the last 20 years. The highest fluctuation is seen in the shadow rates of UK followed by New Zealand while the shadow rates of Japan remained more stable . The daily fluctuations in SSR as well as all the stock markets from Jan-2000 to Mar-2022 are illustrated in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, while Table 2 provides a summary of statistics for daily stock market returns. Overall, with slight variations, all stock markets provide a small daily positive return. However, these markets’ risk behavior makes them different from each other. The highest fluctuation of market returns can be observed in the Eurozone and Nikkei 225 while the stock markets of New Zealand and Australia remain more stable. Additionally, all the selected stock markets have negative and non-zero skewness values, with kurtosis values indicating the presence of fat tails.

Fig. 1.

Fluctuation in SSR From Jan-2000 to Mar-2022, for the different markets: US (panel a), Eurozone (panel b), Japan (panel c), UK (panel d), Switzerland (panel e), Canada (panel f), Australia (panel g) and New Zealand (panel h).

Fig. 2.

Time trend of daily stock market indices from Jan-2000 to Mar-2022, for the different stock indices: DJIA (panel a), Euro-area Index (panel b), Nikkei 225 (panel c), FTSE 100 (panel d), SMI (panel e), S&P TSX (panel f), S&P ASX (panel g) and NZX 50 (panel h).

2.2. Multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis (MF-DXA)

Zhou [52] combined the MF-DFA and DXA to develop the MF-DXA, which has been widely used in recent literature to address the multifractal characteristics in the cross-correlation of two time series [[63], [64], [65]]. For instance, to examine the relationship between US economic policy uncertainty and US dollar exchange rate return, Zhao and Cui [66] employed MF-DXA and found significant evidence of long-range persistent cross-correlation as well as the existence of multifractal characteristics in the relationship between those variables.

MF-DXA is employed according to the following steps, in two equal length time series given by , and with dimension :

Step 1

Build the profiles, according to equations [1,2].

(1)

(2) where , with and as the mean values of the original samples.

Step 2

Divide and into non overlapping segments with the same lengths , with . Aiming not to disregard information from the end of the profile, a similar process is made starting from end of the profile, implying a total of .

Step 3: Local trends and are calculated, through ordinary least-squares (OLS), for every segment, for , from which the variance is determined as described in equations [3,4]:

(3) for , and

(4)

Step 4

Based on equation (4), it is calculated the average of all the segments from the second step, aiming to have the order fluctuation functions as described in equations [5,6]:

(5) if , while in the case of , we have

(6) In equation (5), is the difference between small and large fluctuation segments: if q is negative, it means a small change, which if it is positive, it refers to a large change. The standard DXA exponent comes from , in a function which increases with .

Step 5: Performing a regression between and , for every q, allow to obtain the scaling behavior. When the original series and are cross-correlated, rises with according to a power-law given by:

(7) The scaling exponent from equation [7] denotes a power law cross-correlation even in the case of two non-stationary time series, with an increase in meaning local fluctuation growth related with the increase of the time scale (s). If both original series are equal, MF-DXA gives the same result from MFDFA. If behaves consistently according to the different values of q means the existent cross-correlation between both series has mono-fractal properties. On the contrary, in the case of multifractality, it is possible to estimate the relationship between and , with positive(negative) values of showing, respectively, the scaling behavior of higher(lower) fluctuations from the segments.

If the estimated exponents is , the given time series show long-range persistent, while in the case of , series are anti-persistent long-range cross-correlated. In the case of , the original time series has no long-range cross-correlation between pattern.

It is also possible to estimate the time-varying multifractality power as given by equation [8]:

(8) Higher values of mean stronger multifractality levels. Through the Legendre transformation, we could obtain , as described in equation [9]:

(9) which allows us to write the singularity spectrum as equation [10]:

(10) Finally, it is also possible to obtain the multifractal spectrum width, used to examine the level of multifractality, as presented in equation [11]:

(11) In fact, higher changes in are related with higher multifractality levels, with the multifractality being estimated as , with decreasing while q rises [67]. Larger values of imply hivher multifractality levels in the relationship between the original time series. In this paper, we used the R package “MFDFA” [ [68,69]],1 in order to apply MF-DXA technique.

3. Empirical findings

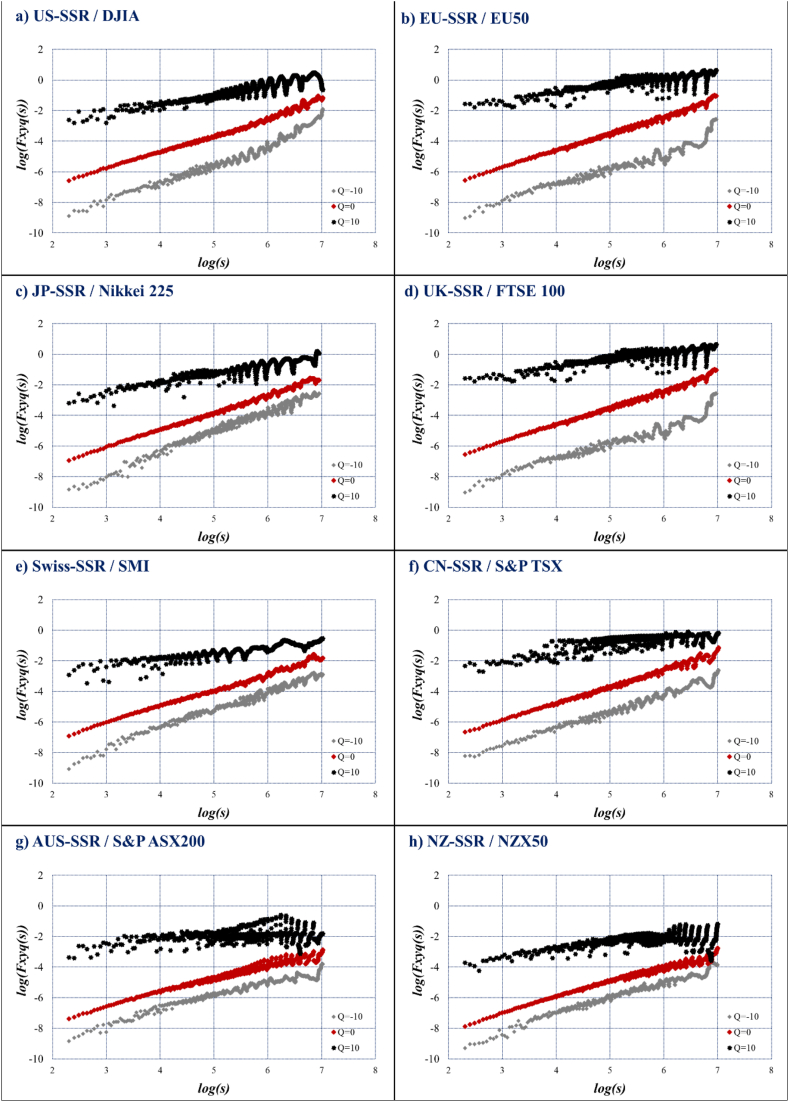

The cross-correlations between SSR and stock market indices of all the economies considered are examined in this section using the MF-DXA. This technique can examine the fractal properties of time series at various time scales and efficiently eliminate the impact of local trends on the scale of time series. The fluctuation function is estimated with one step increasing scale order , where the range of is fixed at , as suggested by similar studies [70,71]. The plots of vs. time scale for , between SSR and stock market returns, are shown in Fig. 3(a–h). As can be observed, the curves exhibit a generally linear relationship with time-varying values of , suggesting that all pairs of SSR and stock markets exhibit cross-correlations or power-law correlations.

Fig. 3.

Log-Log plot of Fluctuation functions Fxyq (S) versus s for q = [-10,0,+10], for the different markets: US (panel a), Eurozone (panel b), Japan (panel c), UK (panel d), Switzerland (panel e), Canada (panel f), Australia (panel g) and New Zealand (panel h).

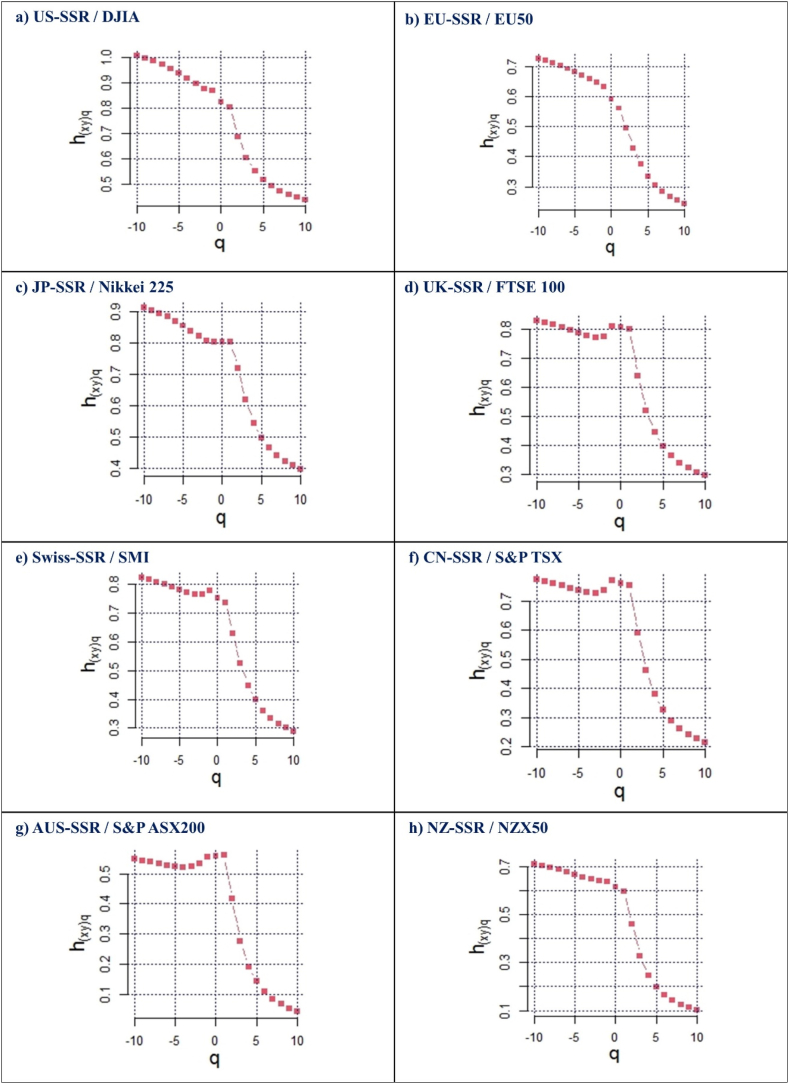

Fig. 4(a–h) shows the generalized Hurst Exponent values between SSR and the stock market returns, ranging from , in a decreasing trend between that exponent and the scale order. For instance, the highest value of for JP-SSR/Nikkei 225, in the fourth column of Table 3, is for , falling to at and declining to its minimum level of at . Similarly, the highest value of for UK-SSR/FTSE 100 at is , falling to at and with the lowest value of for . A similar declining pattern is noticed in the remaining six SSR/stock market returns. This declining trend confirms the presence of multifractality patterns in the time fluctuations of the shadow short rates and stock market pairs. The findings show that the values between SSR and stock markets behave with a downward pattern, as long as the time scale increases. We found that values for are all larger than the values of , demonstrating that small fluctuations have more persistent cross-correlation behavior than larger fluctuations. Furthermore, for larger and smaller fluctuations decreases as the scaling order increases, meaning that large fluctuations have less cross-correlation than small fluctuations.

Fig. 4.

Generalized Hurst exponent Hxy dependence on q for q = −10, q = 0, q = 10, for the different markets: US (panel a), Eurozone (panel b), Japan (panel c), UK (panel d), Switzerland (panel e), Canada (panel f), Australia (panel g) and New Zealand (panel h).

Table 3.

Hurst Exponent ranging from q = −10 to q = 10.

| Q | US-SSR/DJIA | EU-SSR/Euro-area Index | JP-SSR/Nikkei 225 | UK-SSR/FTSE 100 | Swiss-SSR/SMI | CN-SSR/S&P TSX | AUS-SSR/S&P ASX200 | NZ-SSR/NZX50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q = −10 | 1.0073 | 0.7273 | 0.9137 | 0.8297 | 0.8235 | 0.7754 | 0.5495 | 0.7104 |

| q = −9 | 0.9975 | 0.7203 | 0.9054 | 0.8232 | 0.8164 | 0.7687 | 0.5441 | 0.7037 |

| q = −8 | 0.9860 | 0.7124 | 0.8956 | 0.8158 | 0.8085 | 0.7613 | 0.5383 | 0.6961 |

| q = −7 | 0.9725 | 0.7034 | 0.8842 | 0.8074 | 0.7996 | 0.7532 | 0.5325 | 0.6874 |

| q = −6 | 0.9566 | 0.6933 | 0.8709 | 0.7980 | 0.7900 | 0.7447 | 0.5270 | 0.6776 |

| q = −5 | 0.9381 | 0.6822 | 0.8556 | 0.7878 | 0.7801 | 0.7364 | 0.5226 | 0.6670 |

| q = −4 | 0.9174 | 0.6707 | 0.8388 | 0.7778 | 0.7711 | 0.7296 | 0.5209 | 0.6560 |

| q = −3 | 0.8959 | 0.6592 | 0.8217 | 0.7710 | 0.7652 | 0.7278 | 0.5235 | 0.6458 |

| q = −2 | 0.8776 | 0.6476 | 0.8078 | 0.7758 | 0.7664 | 0.7381 | 0.5334 | 0.6384 |

| q = −1 | 0.8693 | 0.6327 | 0.8032 | 0.8107 | 0.7775 | 0.7726 | 0.5543 | 0.6362 |

| q = 0 | 0.8241 | 0.5919 | 0.8034 | 0.8056 | 0.7519 | 0.7604 | 0.5595 | 0.6134 |

| q = 1 | 0.8021 | 0.5612 | 0.8032 | 0.8012 | 0.7368 | 0.7538 | 0.5619 | 0.5960 |

| q = 2 | 0.6879 | 0.4963 | 0.7198 | 0.6395 | 0.6287 | 0.5900 | 0.4155 | 0.4609 |

| q = 3 | 0.6038 | 0.4288 | 0.6185 | 0.5182 | 0.5235 | 0.4605 | 0.2743 | 0.3263 |

| q = 4 | 0.5514 | 0.3743 | 0.5463 | 0.4438 | 0.4484 | 0.3786 | 0.1914 | 0.2455 |

| q = 5 | 0.5166 | 0.3344 | 0.4985 | 0.3959 | 0.3971 | 0.3251 | 0.1413 | 0.1968 |

| q = 6 | 0.4920 | 0.3054 | 0.4654 | 0.3631 | 0.3612 | 0.2882 | 0.1080 | 0.1648 |

| q = 7 | 0.4735 | 0.2836 | 0.4414 | 0.3393 | 0.3352 | 0.2614 | 0.0843 | 0.1421 |

| q = 8 | 0.4591 | 0.2668 | 0.4233 | 0.3213 | 0.3155 | 0.2412 | 0.0665 | 0.1252 |

| q = 9 | 0.4476 | 0.2534 | 0.4091 | 0.3073 | 0.3003 | 0.2255 | 0.0527 | 0.1121 |

| q = 10 | 0.4382 | 0.2425 | 0.3977 | 0.2960 | 0.2882 | 0.2130 | 0.0417 | 0.1016 |

| Δh | 0.5691 | 0.4848 | 0.5160 | 0.5337 | 0.5353 | 0.5624 | 0.5078 | 0.6088 |

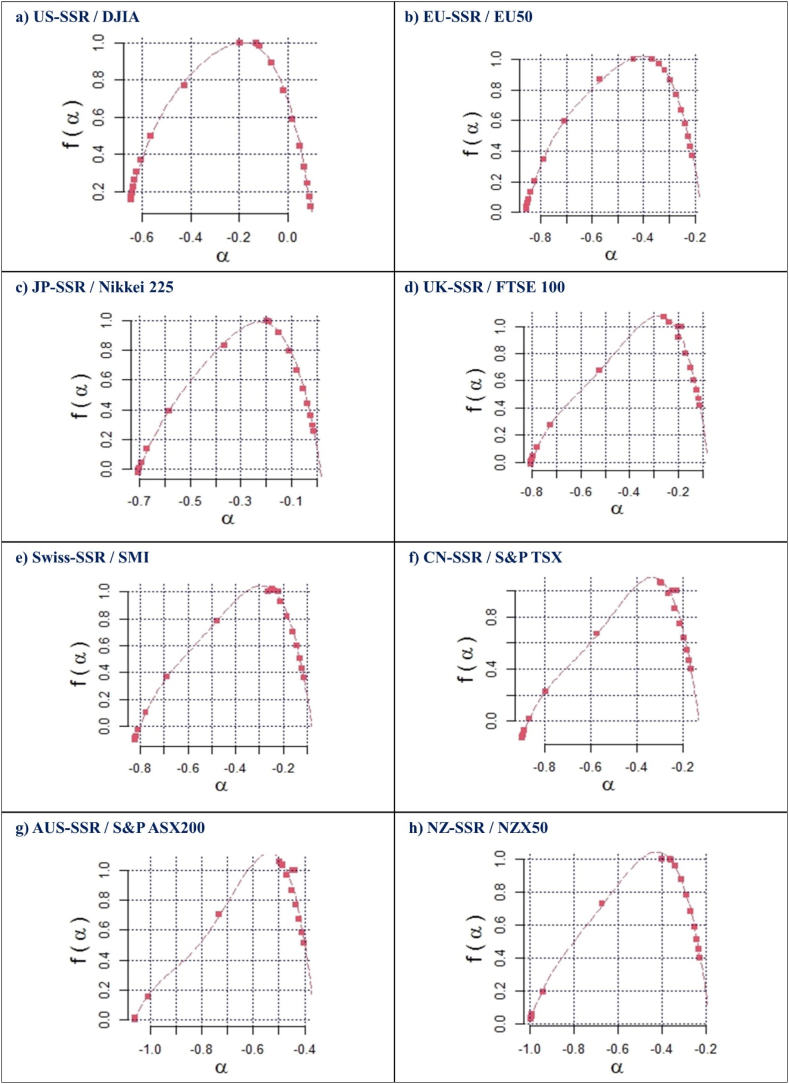

The multifractal strength or the degree of multifractality denoted by , is reported in the last row of Table 3, which is significantly greater than zero, indicating that the cross-correlations between SSR and stock markets exhibit robust multifractal patterns. However, the results reveal a varying degree of multifractal strength among these pairs. For instance, the highest multifractality is found in NZ-SSR/NZX50 , followed by US-SSR/DJIA and CN-SSR/S&P TSX . On the other hand, the pairs of EU-SSR/Euro-area Index and AUS. SSR/S&P ASX200 show, respectively, values of equal to and , while other pairs have values between those ones. These results can be further verified by calculating the width of multifractal spectrums , as shown in Fig. 5(a–h). This greater width shows higher variations in the distribution of smaller and bigger fluctuations, implying non-homogeneous and irregular distribution, which is quite expected because of the higher occasional features of stock market returns. Significant non-zero widths of multifractal spectra of the cross-correlations confirm clear departures from the random walk process. The presence of multifractality in the cross-correlation structure adheres to the principles of the adaptive market hypothesis (AMH) [72], which was also corroborated by previous studies (for example, [[73], [74], [75]].

Fig. 5.

The Multiple Spectra of vs. α, for the different markets: US (panel a), Eurozone (panel b), Japan (panel c), UK (panel d), Switzerland (panel e), Canada (panel f), Australia (panel g) and New Zealand (panel h).

Lastly, we present the values at in Table 3, which demonstrates the persistent or anti-persistent behavior in the cross-correlations of SSR and respective stock market returns. Five economies, namely USA, Japan, UK, Switzerland, and Canada, have greater than , indicating that the SSR and stock markets of these economies exhibit persistent cross-correlations, while in the case of Australia and New Zealand the value is lower than 0.5, meaning an anti-persistent cross-correlation.

The literature gives three possible interpretations of these results. According to Kristoufek [76], represents a cross-persistent series and a positive (negative) value of means a higher probability of another positive (negative) value of . However [48,77], argue that long-range cross correlation means that each series has a long memory of its own previous values plus a long memory of previous values of the second series. Additionally, Podobnik and Stanley [48] conclude that those power-law cross-correlations indicate that an increase (decrease) in one variable is more likely to be followed by an increase (decrease) in the other variable. Only the value of for the eurozone is very close to zero, indicating weak evidence of cross-correlation in their multifractality.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study is to quantify the multifractal cross-correlations between the stock market indices and shadow short rates (SSR) of eight developed economies i.e., US, Eurozone, Japan, UK, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Based on daily data from 01-Jan-2000 to 30-Mar-2022, we applied the multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis (MF-DXA) proposed by Zhou [52] to examine the relationship between SSR and stock market returns.

Overall, the findings suggest that the pairs of country specific SSR and stock markets exhibit multifractal cross-correlations. The existence of multifractal cross-correlations of asset returns is documented by several studies including stock markets [78,79], forex [66], cryptocurrency [64,80] commodities [[81], [82], [83]] and energy [84]. The dividend discount model explains this relationship with investors' expectations of future cash flows and the real interest rate, which is used to discount rate or the risk premium related to holding stocks, which is also affected by monetary policy actions [[20], [21], [22]]. Specifically, the results reveal the highest multifractality for New Zealand, USA and Canada and the lowest in the Eurozone pair. The stock markets of Australia and New Zealand show anti-persistent cross-correlation with SSR, while the rest show persistent cross-correlation. Furthermore, the cross-correlation behavior of small fluctuations remained more persistent when compared to large fluctuations. The fact that Australian stock markets show anti-persistent behavior with unconventional monetary policies could be explained by different reasons. Firstly, Australia was less impacted by the GFC of 2007–2008 than other advanced economies i.e., US, Euro-area. To address the crisis, it used the policy rate as its main instrument and provided enough liquidity to the financial sector, or in other words, it practiced conventional monetary policy measures.2 Secondly, according to Lowe [10], negative interest rates in Australia are extraordinarily unlikely. The reason for this is that Australia's central bank, or reserve bank, feels that negative interest rates put a strain on certain aspects of the financial system and may limit some banks' ability to extend credit. Pension funds that have long-term responsibilities to pay for are likewise affected negatively by negative interest rates. Additionally, it has been shown that they can motivate families to save more money and spend less, particularly when people are worried about having less money in retirement. Therefore, a shift to negative interest rates may undermine confidence in the prospects for the economy as a whole and make people more cautious. Thirdly, there are no plans to launch an outright QE program that involves buying private sector assets, because there is no indication of a problem in Australian capital markets that would require intervention by the reserve bank. However, the recent COVID-19 pandemic became a global economic event of unprecedented magnitude. In response, the Australian reserve bank introduced unconventional monetary policy measures in March 2020 for the first time and announced further unconventional policy measures in November 2020 to support job creation and the recovery of the Australian economy from COVID-19.

Similar to Australia, the reserve bank of New Zealand did not implement zero/negative interest rates or any other unconventional monetary measures after the GFC of 2007–2008 [85]. The Official Cash Rate (OCR) is a key tool for monetary policy in New Zealand, which has always been above zero, and even during the GFC of 2007–2008, OCR was reduced from 8.25% to 2.5% [86]. However, the reserve bank of New Zealand recently opted to use unconventional monetary policy by using LSAPs to mitigate the economic effects of COVID-19, and it is currently preparing to buy assets worth NZD 60 billion [85,87]. The evidence of this relationship gives policy-makers an opportunity to explore the possibility of having a monetary policy tool under zero bound interest rates. The trade-off under the Taylor rule becomes a difficult choice in times of crisis and low bound interest rates, as central banks cannot decrease the rates further to stimulate the economy [3]. There is a need to explore the option of using SSR after evaluating its effect on other macroeconomic indicators like bank lending and real economic activity.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

After the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, central banks adapted unconventional policy measures, which has important linkages with asset returns. By using the framework of the fractal market hypothesis (FMH), this is the first study on the cross-correlation of unconventional policies i.e., SSR with stock markets. We employed a multifractal detrended cross correlation analysis (MF-DXA) model by using country specific short shadow rates and stock market indices. For a comprehensive analysis, we use daily data from 1st January 2000 to 31st March 2022 of eight developed economies: US, Euro Area, Japan, Switzerland, New Zealand, Canada, Australia and UK.

We come to the following conclusions considering the above results. Firstly, the fluctuations and changes in the SSR and stock market returns proved to be multifractal and interacting in a nonlinear way. This could mean that stock market participants can increase the movability of trading strategies involving SSR. Secondly, there is significant multifractality in the cross correlation of SSR and stock markets, with the highest multifractality found for New Zealand, USA and Canada and the lowest in the Eurozone pair. Thirdly, the stock markets of Australia and New Zealand show anti-persistent cross-correlation with SSR, while the rest show persistent cross-correlation. Furthermore, the evidence of long-range cross-correlations implies that past changes in SSR values can improve the predictability of stock markets’ future prices. Finally, the cross-correlation behavior of small fluctuations remained more persistent when compared to large fluctuations, suggesting that short-term shocks persist more in the market than large shocks. The implication is that fund managers and investors, in the long run, should be vigilant in using stock markets as a safe haven in uncertain periods.

The findings of this study reveal several important implications for academics, market participants and policymakers. The nonlinear dependence in the cross-correlations shows that any changes in SSR will impact the volatility and return of the stock markets of that country. Additionally, investors can implement portfolio management strategies involving SSR by adjusting the stock holdings with the changes in SSR [88]. Finally, the cross-correlated behavior of large fluctuation (for ) is greater than that of small fluctuation (for ). To deepen our investigation, the consequences of the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) and geopolitical risk indicators should be considered in further studies.

Author contribution statement

Faheem Aslam: Wahbeeah Mohti: Haider Ali: Paulo Jorge Silveira Ferreira: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding

Paulo Ferreira acknowledges the financial support of Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (grant UIDB/05064/2020).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Faheem Aslam, Email: faheem.aslam@comsats.edu.pk.

Wahbeeah Mohti, Email: Wahbeeah.mohti@iqraisb.edu.pk.

Haider Ali, Email: haideralinaqi55@gmail.com.

Paulo Ferreira, Email: pferreira@ipportalegre.pt.

Appendix A. Acronyms and Abbreviations

| EU | Euro-area |

|---|---|

| JP | Japan |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| Swiss | Switzerland |

| CN | Canada |

| AUS | Australia |

| NZ | New Zealand |

| SSR | shadow short rate |

References

- 1.Pfister C., Sahuc J.-G. Unconventional monetary policies: a stock-taking exercise. Rev. Écon. Polit. 2020;130:137–169. doi: 10.3917/redp.302.0137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inoue A., Rossi B. The effects of conventional and unconventional monetary policy on exchange rates. J. Int. Econ. 2019;118:419–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2019.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor J.B. Carnegie-Rochester Conf. Ser. Public Pol. Elsevier; 1993. Discretion versus policy rules in practice. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pažický M. The consequences of unconventional monetary policy in euro area in times of monetary easing. Oeconomia Copernicana. 2018;9:581–615. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell J.R., et al. Macroeconomic effects of federal reserve forward guidance. Brookings Pap. Econ. Activ. 2012:1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dell'Ariccia G., Rabanal P., Sandri D. Unconventional monetary policies in the euro area, Japan, and the United Kingdom. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018;32:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudebusch G. A review of the fed’s unconventional monetary policy. FRBSF Economic Letter. 2018;27:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potter S., Smets F. 2019. Unconventional Monetary Policy Tools: A Cross-Country Analysis Committee on the Global Financial System, Bank for International Settlements. (Committee on the Global Financial System, Bank for International Settlements) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernanke B.S. The new tools of monetary policy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020;110:943–983. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe P. Address to Australian Business Economists Dinner; Sydney: 2019. Unconventional Monetary Policy: Some Lessons from Overseas; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oum S., Kates J., Wexler A. 2022. Economic Impact of COVID-19 on PEPFAR Countries. (KFF) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozili P.K., Arun T. Managing Inflation and Supply Chain Disruptions in the Global Economy. IGI Global; 2023. Spillover of COVID-19: impact on the global economy; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cecioni M., Ferrero G., Secchi A. Innovative Federal Reserve Policies during the Great Financial Crisis. World Scientific; 2019. Unconventional monetary policy in theory and in practice; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fawley B.W., Neely C.J. Four stories of quantitative easing. Fed. Reserv. Bank St. Louis Rev. 2013;95:51–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattori M., Schrimpf A., Sushko V. The response of tail risk perceptions to unconventional monetary policy. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2016;8:111–136. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balcilar M., et al. Fed’s unconventional monetary policy and risk spillover in the US financial markets. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2020;78:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright J.H. What does monetary policy do to long‐term interest rates at the zero lower bound? Econ. J. 2012;122:F447–F466. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagnon J. 2010. Large-Scale Asset Purchases by the Federal Reserve: Do They Work? (DIANE Publishing) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fausch J., Sigonius M. The impact of ECB monetary policy surprises on the German stock market. J. Macroecon. 2018;55:46–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plakandaras V., et al. Evolving United States stock market volatility: the role of conventional and unconventional monetary policies. N. Am. J. Econ. Finance. 2022;60 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernanke B.S. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, Mass.; USA: 1990. The Federal Funds Rate and the Channels of Monetary Transnission. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernanke B.S., Kuttner K.N. What explains the stock market's reaction to Federal Reserve policy? J. Finance. 2005;60:1221–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00760.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galí J., Gambetti L. The effects of monetary policy on stock market bubbles: some evidence. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2015;7:233–257. doi: 10.1257/mac.20140003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harvey C. 2020. The Economic and Financial Implications of COVID-19. 3rd April. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei X., Han L. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on transmission of monetary policy to financial markets. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021;74 doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kampl L.-M. Measuring the short-term effects of the ECB’s unconventional monetary policy on financial markets: a review. Credit Capital Markets–Kredit Und Kapital. 2021;54:37–77. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zabala J.A., Prats M.A. The unconventional monetary policy of the European Central Bank: effectiveness and transmission analysis. World Econ. 2020;43:794–809. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira E., Serra A.P. Price effects of unconventional monetary policy announcements on European securities markets. J. Int. Money Finance. 2022;122 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kubota H., Shintani M. High-frequency identification of monetary policy shocks in Japan. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 2022;73:483–513. doi: 10.1007/s42973-021-00110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DaSilva A., Farka M. Business cycles, stock returns and the transmission channels of conventional and unconventional monetary policy. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cepni O., Gupta R., Ji Q. Sentiment regimes and reaction of stock markets to conventional and unconventional monetary policies: evidence from OECD countries. J. Behav. Finance. 2021:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdullah A.A., Hassanien A.M. Spillovers of US unconventional monetary policy to emerging markets: evidence from Egypt. Int. J. Econ. Finance. 2022;14:1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lutz C. The international impact of US unconventional monetary policy. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2015;22:955–959. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tillmann P. Unconventional monetary policy and the spillovers to emerging markets. J. Int. Money Finance. 2016;66:136–156. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elsayed A.H., Sousa R.M. International monetary policy and cryptocurrency markets: dynamic and spillover effects. Eur. J. Finance. 2022:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabriel S.A., Lutz C. 2017. The Impact of Unconventional Monetary Policy on Real Estate Markets. Available at SSRN 2493873. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattarai S., Neely C. 2016. A Survey of the Empirical Literature on US Unconventional Monetary Policy. (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Research Division) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrakis N., et al. Eurozone stock market reaction to monetary policy interventions and other covariates. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022;15:56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granger C.W., Maasoumi E., Racine J. A dependence metric for possibly nonlinear processes. J. Time Anal. 2004;25:649–669. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurst H.E. Long-term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1951;116:770–799. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo A.W. Long-term memory in stock market prices. Econometrica. J. Econom. Soc. 1991:1279–1313. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng C.-K., et al. Mosaic organization of DNA nucleotides. Phys. Rev. 1994;49:1685. doi: 10.1103/physreve.49.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kantelhardt J.W., et al. Multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis of nonstationary time series. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2002;316:87–114. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aslam F., et al. Herding behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison between Asian and European stock markets based on intraday multifractality. Eurasian Economic Rev. 2021:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali H., Aslam F., Ferreira P. Modeling dynamic multifractal efficiency of US electricity market. Energies. 2021;14:6145. doi: 10.3390/en14196145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stosic T., Nejad S.A., Stosic B. Multifractal analysis of Brazilian agricultural market. Fractals. 2020;28 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao Y.-H., et al. Multifractal behavior of cryptocurrencies before and during COVID-19. Fractals. 2021;29 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Podobnik B., Stanley H.E. Detrended cross-correlation analysis: a new method for analyzing two nonstationary time series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.084102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tzanis C.G., et al. Multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis of global methane and temperature. Rem. Sens. 2020;12:557. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao W., et al. Long-term atmospheric visibility, sunshine duration and precipitation trends in South China. AtmEn. 2015;107:204–216. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen C.-h., Li C.-l., Si Y.-l. A detrended cross-correlation analysis of meteorological and API data in Nanjing, China. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2015;419:417–428. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou W.-X. Multifractal detrended cross-correlation analysis for two nonstationary signals. Phys. Rev. 2008;77 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.066211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aslam F., Bibi R., Ferreira P. Cross-correlations between economic policy uncertainty and precious and industrial metals: a multifractal cross-correlation analysis. Resour. Pol. 2022;75 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maghyereh A., Abdoh H., Wątorek M. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the dynamic correlations between gold and US equities: evidence from multifractal cross-correlation analysis. Qual. Quantity. 2022:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11135-022-01404-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krippner L. Measuring the stance of monetary policy in zero lower bound environments. Econ. Lett. 2013;118:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krippner L. 2015. A Comment on Wu and Xia (2015), and the Case for Two-Factor Shadow Short Rates. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Claus E., Claus I., Krippner L. Asset market responses to conventional and unconventional monetary policy shocks in the United States. J. Bank. Finance. 2018;97:270–282. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Francis N., Jackson L., Owyang M. 2014. How Has Empirical Monetary Policy Analysis Changed after the Financial Crisis? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2014-019A. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kose M.A., et al. 2017. The Global Role of the US Economy: Linkages, Policies and Spillovers. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ouerk S. ECB unconventional monetary policy and volatile bank flows: spillover effects on emerging market economies. Int. Economics. 2023;173:175–211. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Christensen J.H., Rudebusch G.D. Dynamic Factor Models. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2016. Modeling yields at the zero lower bound: are shadow rates the solution? [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu J.C., Xia F.D. Measuring the macroeconomic impact of monetary policy at the zero lower bound. J. Money Credit Bank. 2016;48:253–291. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cao G., He C., Xu W. Effect of weather on agricultural futures markets on the basis of DCCA cross-correlation coefficient analysis. FNL. 2016;15 1650012-1-1650012-21. [Google Scholar]

- 64.El Alaoui M., Bouri E., Roubaud D. Bitcoin price–volume: a multifractal cross-correlation approach. Finance Res. Lett. 2019;31 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2018.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wątorek M., et al. Multifractal cross-correlations between the world oil and other financial markets in 2012–2017. Energy Econ. 2019;81:874–885. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2019.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao R., Cui Y. Dynamic cross-correlations analysis on economic policy uncertainty and US dollar exchange rate: AMF-DCCA perspective. Discrete Dynam Nat. Soc. 2021:2021. doi: 10.1155/2021/6668912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zunino L., et al. A multifractal approach for stock market inefficiency. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2008;387:6558–6566. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2008.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laib M., et al. Multifractal analysis of the time series of daily means of wind speed in complex regions. Chaos, Solit. Fractals. 2018;109:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2018.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laib M., Telesca L., Kanevski M. Long-range fluctuations and multifractality in connectivity density time series of a wind speed monitoring network. Chaos: Interdiscipl. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2018;28 doi: 10.1063/1.5022737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aslam F., et al. On the inner dynamics between Fossil fuels and the carbon market: a combination of seasonal-trend decomposition and multifractal cross-correlation analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2022:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-23924-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aslam F., et al. Application of multifractal analysis in estimating the reaction of energy markets to geopolitical acts and threats. Sustainability. 2022;14:5828. doi: 10.3390/su14105828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kristoufek L., Vosvrda M. Measuring capital market efficiency: global and local correlations structure. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2013;392:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2012.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ferreira P. Assessing the relationship between dependence and volume in stock markets: a dynamic analysis. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019;516:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2018.09.187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hasan R., Salim M.M. Power law cross-correlations between price change and volume change of Indian stocks. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2017;473:620–631. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2017.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ruan Q., Jiang W., Ma G. Cross-correlations between price and volume in Chinese gold markets. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2016;451:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2015.12.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kristoufek L. Multifractal height cross-correlation analysis: a new method for analyzing long-range cross-correlations. EPL. 2011;95 doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/95/68001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan Y., Zhuang X.-t., Liu Z.-y. Price–volume multifractal analysis and its application in Chinese stock markets. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2012;391:3484–3495. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2012.01.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aslam F., et al. Islamic vs. Conventional equity markets: a multifractal cross-correlation analysis with economic policy uncertainty. Economies. 2023;11:16. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang W., Li J., Sun G. Economic policy uncertainty and stock markets: a multifractal cross-correlations analysis. FNL. 2021;20 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gajardo G., Kristjanpoller W.D., Minutolo M. Does Bitcoin exhibit the same asymmetric multifractal cross-correlations with crude oil, gold and DJIA as the Euro, Great British Pound and Yen? Chaos. Solitons & Fractals. 2018;109:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aslam F., et al. Cross-correlations between economic policy uncertainty and precious and industrial metals: a multifractal cross-correlation analysis. Resour. Pol. 2021;75:102473. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu L. Cross-correlations between crude oil and agricultural commodity markets. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2014;395:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Q., Hu Y. Cross-correlation between interest rates and commodity prices. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2015;428:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2015.02.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.F. Aslam, et al., On the inner dynamics between Fossil fuels and carbon market: A combination of Seasonal-Trend Decomposition and Multifractal Cross-Correlation Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., Forthcoming. 10.1007/s11356-022-23924-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Kumar V., Acharya S., Ho L.T. Does monetary policy influence the profitability of banks in New Zealand? Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020;8:35. doi: 10.3390/ijfs8020035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Drought S., Perry R., Richardson A. Aspects of implementing unconventional monetary policy in New Zealand. Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin. 2018;81:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Croy D., Zollner S. 2020. RBNZ Announces Quantitative Easing. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Attig N., et al. Dividends and economic policy uncertainty: international evidence. J. Corp. Finance. 2021;66 doi: 10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.