Abstract

cGAS-STING signaling is a central component in the therapeutic action of most existing cancer therapies. The accumulated knowledge of tumor immunoregulatory network in recent years has spurred the development of cGAS-STING agonists for tumor treatment as an effective immunotherapeutic strategy. However, the clinical translation of these agonists is thus far unsatisfactory because of the low immunostimulatory efficacy and unrestricted side effects under clinically relevant conditions. Interestingly, the rational integration of biomaterial technology offers a promising approach to overcome these limitations for more effective and safer cGAS-STING-mediated tumor therapy. Herein, we first outline the cGAS-STING signaling axis and generally discuss its association with tumors. We then symmetrically summarize the recent progress in those biomaterial-based cGAS-STING agonism strategies to generate robust antitumor immunity, categorized by the chemical nature of those cGAS-STING stimulants and carrier substrates. Finally, a perspective is provided to discuss the existing challenges and potential opportunities in cGAS-STING modulation for tumor therapy.

Keywords: cGAS-STING pathway, anti-tumor immunity, cancer therapy, STING agonists, nanointegrated drug delivery

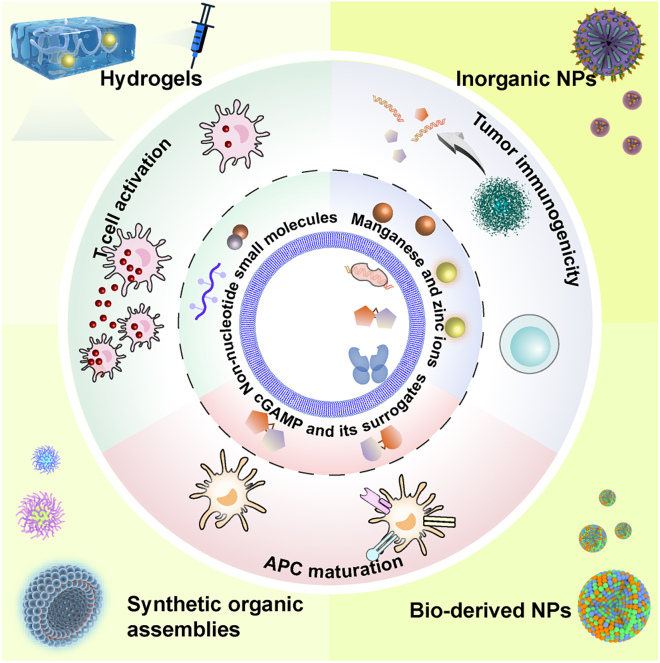

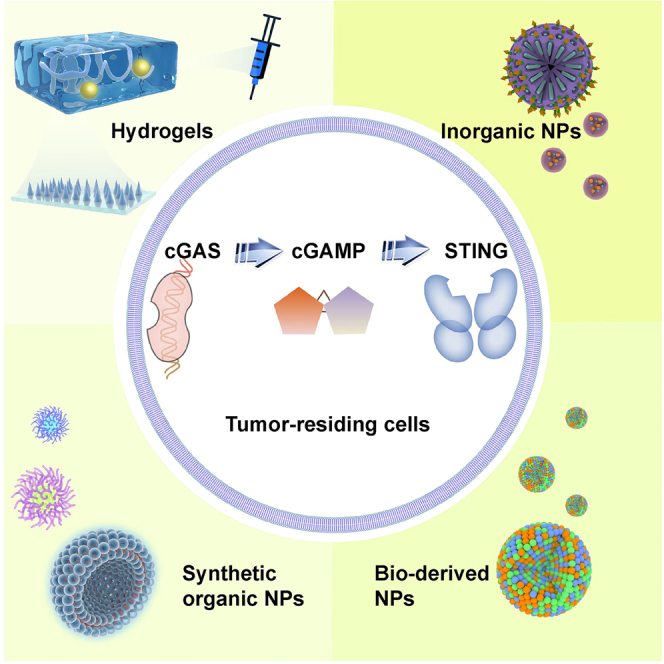

Graphical abstract

Luo et al. comprehensively discussed the multifaceted roles of cGAS-STING activity in shaping antitumor immunity in this review, highlighting those nanointegrated delivery approaches of cGAS-STING agonists for more effective and safer immunotherapy, which may facilitate the development of more advanced immunotherapeutic concepts.

Introduction

DNA is the primary genetic material for almost all living organisms and carries hereditary information, which is usually confined within cell nuclei or mitochondria. However, under certain circumstances, such as radiation and genotoxic stress, self- and non-self-DNAs would aberrantly appear in cytosol to drive various pathological processes.1,2 Detection of cytosolic DNA is thus one of the integrated functions of the immune system, which plays major roles in host defense against infections and tumors.3,4 cGMP–AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway is an evolutionarily conserved cytosolic DNA sensing mechanism in mammalian cells, which is critically involved in both the innate and adaptive immune responses.5 From a mechanistic perspective, cytoplasmic cGAS could bind with mis-located double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and form a dimer to produce the second messenger- 2′3′ cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) using adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and guanosine triphosphate (GTP). The generated 2′3′-cGAMP would subsequently bind with STING and promote its translocation from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to Golgi apparatus to activate tank binding kinase (TBK1).6 Alternatively, some bacterium-derived cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs) could also act as natural second messengers and directly bind with STING to trigger the downstream signaling activities.7 The phosphorylated TBK1 subsequently induces the dimerization of transcription factors, namely, interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which would relocate to the cell nucleus to mediate the production of type I interferons (IFN-I) and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-α/β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and so on,8 eventually promoting the activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) as well as the cross-priming of effector T cells.

Considering that the cGAS-STING pathway is a major component bridging the innate and adaptive immune systems, it has become a promising target for the development of immunoregulatory treatments against a variety of diseases. For instance, cGAS-STING-NF-κB-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokines have been reported to be the major driver of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in response to the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) accumulation induced by mitochondrial invasion of the ALS mutate TAR DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43, the DNA and RNA binding protein). Pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion of cGAS-STING could prevent development of ALS in TDP-43 mutant mice, which suggests the cGAS-STING as the potential target for treating ALS.9 Interestingly, the critical roles of cGAS-STING signaling in DNA damage responses have attracted tremendous interest for the therapeutic intervention against various tumor indications, either in combination with other DNA-damaging antitumor modality such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy or as stand-alone immunotherapy.10,11 Indeed, several cGAS-STING agonists have been reported and under active clinical trial in the last few years.12 However, the clinical translation of these emerging cGAS-STING targeted agents was not satisfactory as they failed to demonstrate significant antitumor benefits or were prone to inducing severe systemic adverse immune reactions.13 The reason underlying these limitations of current cGAS-STING agonist designs is manifold. On the one hand, cGAS-STING agonism is a non-specific immune activation process, which would indiscriminately stimulate the immune cells in off-target sites and disrupt the immune homeostasis.14 In contrast, it is well understood that the solid tumor microenvironment (TME) is a highly complex niche with distinct immunosuppressive traits such as physical drug delivery barriers, insufficient immune cell infiltration, reduced availability of tumor-derived dsDNAs, impaired immune cell functions, and so on, which would severely impede the uptake of cGAS-STING agonists by their designated cellular targets in TME and undermine their immunostimulatory efficacy.15

The incorporation of nanotechnology offers novel opportunities to overcome the limitations in existing cGAS-STING agonist designs. Taking advantage of the nanoscale size effect and programmable nano-biointeraction patterns, nanoparticles may thus improve the drug uptake by selected cell populations in TME in a highly accurate manner, of which the associated benefits have already been excellently reviewed.16,17,18,19 Consequently, it is anticipated that the functional integration of cGAS-STING activation strategies and nanoparticle-dependent drug delivery technology may yield unprecedented promise for stimulating antitumor immunity in a safe and effective manner. In the review, we first outline the immunoregulatory mechanisms of cGAS-STING pathway and discuss their impact on major components of the tumor immune microenvironment including tumor cells and immune cells, followed by a comprehensive analysis on the therapeutic contributions of cGAS-STING signaling activity in typical antitumor therapies. Special emphasis is placed on the design and implementation of nanotechnology-enabled cGAS-STING agonism strategies, which are categorized by the chemical nature of the cGAS-STING agonists and carrier substrates (Figure 1). A perspective is finally included discussing the challenges and potential opportunities in cGAS-STING-targeted immunotherapies.

Figure 1.

Overview of typical cGAS-STING agonism strategies and nanotechnology-integrated

Therapeutic approaches in the context of tumor treatment.

Mechanisms of cGAS-STING activation

The essential prerequisites of cGAS activation include the cytosolic accumulation of abundant dsDNA and cGAS aggregation status. For cells under resting states, cGAS molecules are mostly tightly tethered on chromatin and shielded by barrier-to-autointegration factor 1 to remain inactive. Several reports based on cryo-electron microscopy analysis of cGAS-nucleosome complexes indicated that cGAS binds to the histone 2A-histone 2B dimer from the acidic patch of the nucleosome to prevent accidental cGAS dimerization and activation.20,21,22,23 However, there are many scenarios in which the mis-location of abundant dsDNA in cytosol may occur. For instance, the invasion of pathogenic micro-organisms may introduce foreign DNA. Alternatively, cellular stress or damage could trigger the leakage of nucleus dsDNA or mtDNA from their confining subcellular organelles into the cytosol by formation of micronuclei, micro-vehicles, or exosomes. Self- and non-self-cytosolic dsDNAs would then cause cGAS to form aggregates in the cytoplasm and trigger cGAS-STING signaling activities, including sterile inflammation or anti-infection cascades24,25,26,27,28,29,30 (Figure 2). To cope with the excessive self-DNA accumulation-induced survival stress, cells may develop adaptive responses such as the digestion of exonuclease three prime repair exonuclease 1 (TREX1) or endonuclease deoxyribonuclease II.31 It is of interest to note that only cytosolic cGAS seems to demonstrate DNA sensing capabilities as reports reveal that membrane-localized cGAS failed to recognize self-DNA in response to genotoxic stress. Meanwhile, the translocation of cGAS from membrane to cytoplasm is often observed during viral infection to ensure efficient cGAS activation.32

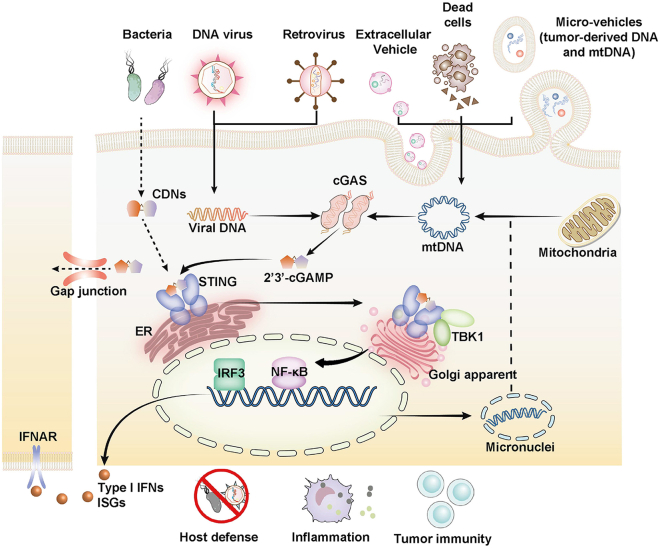

Figure 2.

Mechanism of cGAS-STING activation

cGAS senses the aberrantly located dsDNAs and is activated to form the homogeneous dimers. The activated cGAS dimers catalyze cGAMP production from ATP and GTP. cGAMP binds to STING to facilitate its translocation from the ER to the Golgi apparatus to recruit TBK1 for autophosphorylation. The phosphorylated TBK1 subsequently induces phosphorylation and dimerization of IRF3, and NF-κB activation, which results in their nuclear trafficking. Nucleic IRF3 and NF-κB trigger the production of IFN-I. The secreted IFN-I binds to the cognate receptor IFNAR to induce the production of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). Released cGAMP can be transported through the intercell gap junction and internalized by bystander cells for STING activation, which is important to maintain anti-tumor and anti-viral immunity. Certain bacteria may secret CDNs that resemble the structure of cGAMP to induce activation of STING-TBK1-IRF3/NF-κB axis.

Current insights collectively demonstrate that cGAS is activated by binding to dsDNA through sequence-independent interaction, which induces the formation of the cGAS-DNA-GTP-ATP complex.33 Through the complex formation, cGAS dimerizes to expose its reactive sites and subsequently synthesizes cGAMP using ATP and GTP as substrates.34 It is further noted that the length of the DNA sequence is positively correlated with the catalytic efficiency of cGAS.35,36 Importantly, the cGAS-dsDNA complex would undergo a liquid-liquid phase separation process and condensate into a droplet structure, which may significantly enhance the sensitivity of cGAS to dsDNAs and ensure efficient surveillance of mis-located dsDNAs with a low signaling threshold. The cGAS-dsDNA droplets could be further stabilized by Zn2+ ions, thus promoting the cGAS-mediated production rate of cGAMP.37 The formation of the cGAS-dsDNA-containing droplet is often accompanied by the suppression of cytosolic exonuclease TREX1 activity to facilitate the activation of cGAS immune signaling,38 although the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated (Figure 2).

The role of cGAS-STING in anti-tumor immunity

Considering the major roles of cGAS-STING signaling in vital physiological and immunological events including cell stress, senescence, DNA damage response, and so on, it has been strongly implicated in the emergence and progression of various cancer indications.39 cGAS-STING is a confirmed regulator of tumor cell immunogenicity and the function of tumor-associated immune cells, which plays essential roles in shaping the tumor immune microenvironments and further impact the therapeutic responses.40

As a typical hallmark of tumorigenesis, the chromosomal instability (CIN) provides the major source of dsDNA, which offers the potential opportunity to improve the efficacy of cGAS-STING targeted cancer immunotherapy in the clinics.41 Radio- and chemotherapy may also induce DNA damage responses that are intrinsically linked to cGAS-STING activation,42,43 which can be exploited to enhance their treatment outcome or create novel combinational antitumor therapeutics. Moreover, the cGAS-STING activity in tumor-residing immune cells have been confirmed as a key determinant for regulating their antitumor functions. Therefore, a variety of STING agonists are being developed for antitumor applications. In the section below, we provide a concise yet comprehensive summary on the functions of cGAS-STING signaling in cancer cells and immune cells in the context of malignancies.

Cancer cell-intrinsic cGAS-STING signaling activities

Recent insights reveals that tumor-intrinsic cGAS-STING signaling activity is critical for mediating IFN-I production, which has an indispensable role in priming the tumor-associated T cells through enhancing the cross-presentation of dendritic cells (DCs).44 For example, treatment of DNA-damaging agents including histone H3 associated protein serine/threonine kinase, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, mitotic kinase monopolar spindle 1, and DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors can induce the accumulation of cytosolic DNA in tumor cells to trigger the activation of cGAS-STING-IFN-I cascades, which potently activates the anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses.45,46,47,48

cGAS activation in tumor cells largely dictates its cGAMP production potential, which is critically needed for activating the anti-tumor function of tumor-infiltrating immune cells according to recent studies.49,50 The loss of cGAS activity in tumor cells would impair the cGAMP-mediated activation of DCs and negatively affect the downstream immune cascades, eventually reducing infiltration of IFN-γ producing-CD8+ T cell into solid tumors.49 Meanwhile, the tumor-derived cGAMP could also induce the spontaneous production of IFN-I in non-malignant cells (e.g., endothelial cells) to initiate effector T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity.51 Interestingly, Carozza et al.52 reported that cancer cells constantly secreted cGAMP at low rates to the TME, which were subsequently degraded by ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP1) therein. Ionizing radiation (IR) stimulates cGAMP production and exportation from cancer cells, which could potently increase the infiltration of tumor associated immune cells and inhibit tumor growth in combination with ENPP1 blockade.52 Alternatively, Li et al.53 reported that ENPP1 was significantly elevated during the development and metastasis of chromosomally unstable tumors. The high expression of ENPP1 in cGAShigh triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) reduced infiltration of tumor-residing immune cell and resistance to the immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) treatment. Furthermore, ENPP1 was negatively correlated with the prognosis of the TNBC patients. Mechanically speaking, ENPP1 degrades cGAMP into AMP and GMP; afterward, AMP is further hydrolyzed into the adenosine, which suppresses immune cell activation and promotes the tumor metastasis.53 ENPP1 offers the potential target in enhancing ICB responses via motivating the cGAS-cGAMP-STING signaling. Recently, several cGAMP exporters have been identified, including a passive exporter leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 8 volume-regulated anion channel, and an active ATP-dependent exporter ABCC1.54,55,56 For example, ABCC1 could maintain the concentration of cGAMP in normal cells at a low level to avoid the hypoactivation of cell-intrinsic STING signaling by exporting cGAMP for EPNN1 degradation, suggesting that ABCC1 overexpression in certain types of tumor cells might contribute to the secretion of cGAMP into TME for triggering the anti-tumor immunity.54

However, cGAS-STING activity is frequently impaired in many tumor indications to establish a “cold” TME. The mutation of p53 and tumor suppressor neurofibromin 2 protein have been reported to compromise the cGAS-STING signaling through destabilizing TBK1-STING-IRF3 complex as well as recruiting protein phosphatase 2A to inactivate the phosphorylated TBK1.57,58 STING is also epigenetically quiescent in certain types of tumors due to DNA methyltransferase-mediated hypermethylation and activation of proto-oncogene such as receptor tyrosine kinase (MET) amplification-phosphorylated RNA helicase and ATPase (USP1), thus driving tumorigenesis.59,60,61 Wu et al.62 demonstrated that the receptor tyrosine kinase human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2)-Akt1 axis inactivates cGAS-STING signaling through inhibiting the assembly of the STING signalosome. HER2 induction in melanoma cells suppresses STING-mediated antitumor responses by reducing infiltration of tumor-associated immune cells.62 Therefore, these negative regulators of cGAS-STING signaling in tumor cells offer a plethora of exploitable targets for enhancing cGAS-STING-dependent immunotherapies.

The evidence collectively demonstrates that cancer cell-intrinsic cGAS acts as an important regulator of its immunogenicity, for which its immunoregulatory functions are relayed by cGAMP and type I IFN. The activity of the cancer-autonomous cGAS-STING pathway has been increasingly recognized as an important contributing factor to the efficacy of chemo-, radio- and immunotherapy,42,63,64 offering a novel target for the augmentation of these antitumor modalities.

cGAS-STING in tumor-infiltrated APCs

The cGAS-STING signaling activity in tumor-residing APCs including macrophages and DCs is responsible for detecting the tumor-derived DNA and promoting their maturation to cross-prime anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses, which is intricately regulated to restrict the survival and expansion of tumor cells.39,65 A recent report showed that phagocytic receptor Mer proto-oncogene, tyrosine kinase (MerTK) on tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) surfaces impeded the uptake of cGAMPs and ATP from dying tumor cells with compromised membranes, which inhibited the IFN-I production through the STING-sensing mechanism and impaired the antitumor capacity of effector T cells. In contrast, inhibiting MerTK in TAMs pronouncedly enhanced the uptake of tumor-derived cGAMPs and ATP to stimulate the downstream antitumor immunity.66 Moore et al. reported that activation of cGAS-STING signaling in bone marrow macrophages (BMM) could enhance the phagocytosis capacity for suppressing the growth of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), during which the LC3-associated phagocytosis-dependent processing of dead tumor cells would release abundant mtDNA to trigger STING signaling in BMMs.67 TAMs are a major immune cell population in TME and a primary contributing factor to the immunosuppression therein, which are mainly M2-polarized macrophages and capable of recruiting other immunosuppressive cells while inhibiting immune effector cells. STING agonism in breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA)1-deficient breast tumors substantially promoted the polarization of TAMs from M2-like into M1-like phenotype to inflame the TME.68

cGAS-STING signaling is also essentially required for DC maturation, antigen cross-presentation, and effector function of T cells to enhance robust immune responses. Diamond et al.69 found that radiation-treated cancer cells could release dsDNA-containing exosomes, which were phagocytosed by DCs to stimulate cGAS-STING signaling for promoting DC maturation and subsequent CD8 T cell activation. An inhibitory receptor, T cell immunoglobulin-3 (TIM-3), was recently revealed to regulate the extracellular DNA uptake by classical DCs (cDC1s). TIM-3 blockade enhances internalization of high-mobility group box 1-bound DNA for activation of the cytoplasmic cGAS-STING pathway in cDC1s, which results in improved efficacy of immunotherapy.70 In addition to its function in restricting development of the solid tumor, DC-specific cGAS-STING activation promoted the priming and expansion of leukemia-specific T cells to fight against AML.71 Oxidative stress is a typical feature of TME.72 Hu et al. reported that reactive oxygen species (ROS)-driven SUMO-specific protease 3 activity is required for STING-induced DC anti-tumor responses.73

cGAS-STING in T cells

cGAS-STING signaling in adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells is largely responsible for maintaining their stemness and promoting their differentiation into transcription factor 1high subsets, which is realized mainly through limiting Akt activity by autocrine of IFN-I. Formation of stem-like central memory CD8+ T cells could be further enhanced after administration of STING agonists in the context of clinical cancer treatment, as Li et al. reported that cGAS-STING agonism could reinforce the antitumor effects of chimeric antigen receptor T cell immunotherapy (CAR-T) cell therapy on a xenograft model.74 Xu et al. generated CAR-T cells with enhanced persistence from T helper 17 and CD8+ T 17 cells pretreated with STING agonist-DMXAA or cGAMP. These CAR-T cells acquired the potentiated ability to restrict the tumor growth. DMXAA treatment in breast cancers also promoted CAR-T trafficking into solid tumor tissues through creating the pro-inflammatory milieu.75

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) expressing transcription factor forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3) are potent immune suppressors in TME, which block the function of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, mainly through the expression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4).76 Recently, Field et al. proposed that the impaired function of fatty acid binding protein 5 caused by a lipid deficiency would destabilize mitochondria to release mtDNA in the cytosols, which activates cGAS-STING signaling in Tregs to produce IL-10 and promote their suppressive activity.77 These studies suggest that the delivery of STING agonists in the TME might indiscriminately boost the activity of effector T cells as well as the Tregs, warranting the inclusion of Treg inhibition treatment to ensure the efficacy of cGAS-STING targeted immunotherapies under certain circumstances.

cGAS-STING in other non-cancerous cells

Meanwhile, the STING activity in non-cancerous cells, including host cells and B cells, is confirmed as a crucial factor dictating the function of tumor-infiltrating natural killer (NK) cells. Extracellular cGAMPs imported into these non-cancerous cells could stimulate the STING-mediated IFN-I production therein and thus trigger the tumor-specific cytotoxic responses of NK cells.50 In contrast, cGAMP administration directly induces the proliferation of human and mouse regulatory B cells in an STING-IRF3-IL-35-dependent manner, which restricts NK-mediated anti-tumor responses in pancreatic cancer. As expected, IL-35 blockade in B cells suppresses tumor growth, which offers a potential target in enhancing tumor responses to STING monotherapy.78 NK cell activity can be directly modulated by regulating the NK-intrinsic cGAS-STING signaling as well. STING agonism in NK cells triggers IFN-I production, which promotes activation and cytotoxicity of NK cells for exerting efficient antitumor effects.79

Interestingly, the immunoinhibitory function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a major immunosuppressive cell population in TME, could be alleviated by stimulating their cGAS-STING signaling activities.80 On animal models bearing Epstein-Barr virus-induced nasopharyngeal carcinoma, STING agonism could reshape the immunosuppressive TME by inhibiting MDSC expansion. Mechanistically, the activated STING suppressed signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-mediated granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and IL-6 production, thus preventing MDSC induction.81 There are also reports that STING-stimulation in myeloid cells would transform them into PKR-like ER kinase-deficient MDSCs and trigger the anti-tumor IFN-I production.82

cGAS-STING signaling as a key event in common antitumor modalities

The discussions regarding the contributions of cGAS-STING signaling to antitumor immune responses readily suggest that cGAS-STING activity is indispensable for regulating tumor emergence and development. Concrete evidence collectively demonstrates that the therapeutic activity of major antitumor modalities, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy, all involve the activation of cGAS-STING signaling at certain stages.10,83,84 Indeed, cGAS-STING stimulatory treatment has already demonstrated considerable potential for promoting the efficacy of various antitumor modalities.68,70,85 Typically, chemotherapeutic drugs and radiation may directly activate cGAS-STING signaling activity in tumor-infiltrating immune cells by damaging tumor DNA and releasing the tumor-derived dsDNA into the TME.86,87 There are several reports showing that treating tumor cells with teniposide (a DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor), paclitaxel (Taxol) (an anti-mitotic agent) or cisplatin would increase tumor immunogenicity and promote anti-tumor immunity partially through activating cGAS-STING-IFN responses.47,88,89 Radiotherapy may induce the accumulation of dsDNA fragments in the cytoplasm of cancer cells from their damaged nucleus or mitochondria for the subsequent recognition by cGAS. IFN-I and cGAMP production from cancer cell-intrinsic cGAS-STING signaling activates the cGAS-STING activities in DCs to enable their maturation and the subsequent cross-priming of anti-tumor T cells83,90,91,92,93 (Figure 3). Recently, it has been reported that mtDNA potentiates the dsDNA-induced IFN-I response94 and is identified as a potential therapeutic driver for radiotherapy of breast cancer,92 suggesting that stimulating cGAS-STING-dependent DNA-sensing machinery in tumor-residing immune cells could be a promising strategy for boosting the efficacy of radiotherapy.

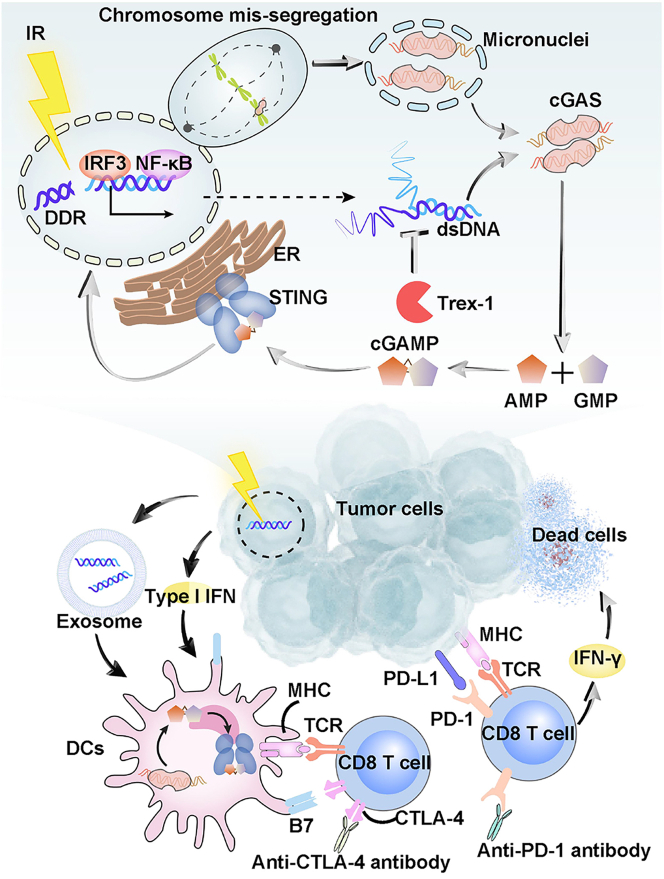

Figure 3.

DNA damage-induced cGAS-STING activation augments type I IFN signaling-mediated anti-tumor immune responses post chemo-, radio- and immune-therapies

Genome aberration triggers cytosolic DNA accumulation such as micronucleus formation. cGAS binds to DNA in micronuclei and synthesizes cGAMP for subsequent activation of ER-resident STING. STING-TBK1-IRF3/NF-κB signaling is activated for IFN-I transcription. Type I IFN signaling and DNA-containing exosomes activate DCs via facilitating tumor antigen/neoantigen presentation on their MHC. MHC-antigen peptide complexes bind to T cell receptor (TCR) and activate CD8+ T cells, but this process may be restricted by the B7:CTLA-4 inhibitory signals. Activated T cells infiltrate tumors and release IFN-γ to mediate the cytotoxic effects against tumor cells, where interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 antagonizes their anti-tumor activities of the immune effectors. Blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 promote the CD8+ T cell anti-tumor responses.

Immunotherapy is considered one of the monumental cancer therapeutic treatments in recent years. There are two major categories of immunotherapy that are ICB and adoptive T cell therapy, which have both demonstrated impressive efficiency to eradicate a variety of tumor indications via boosting the host innate and adaptive immune responses,95 exemplified by the clinical success of programmed death (PD)-1/PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) or CTLA-4 antibodies as well as CAR-T cell therapy.96 Interestingly, cGAS-STING agonism offers an optimal approach to boost the efficiency of these typical immunotherapies as the triggered production of IFN-I and other inflammatory cytokines are indispensable for activating and supporting the anti-tumor responses of immune cells within TME (Figure 3). For instance, Wang et al.97 reported that the anti-tumor effects of PD-L1 blockade in B16 melanoma-mouse model depends on cGAS-STING axis in tumor-infiltrating DC cells. Furthermore, Della Corte et al.63 discovered that the activation of cGAS-STING pathway may contribute to superior immunotherapeutic responses in lung adenocarcinoma. Several recent reports collectively indicate that cGAS-STING activation promotes the efficiency of CAR-T therapy against solid tumors, as both endogenous and exogenous STING agonists could enhance the tumor infiltration of CAR-T cells.75,98,99

Targeting DNA damage-mediated cGAS-STING activation for boosting antitumor immunity

CIN and microsatellite instability (MSI) are hallmarks of cancer progression.41,100,101 DNA damage is the key driver of CIN or MSI-mediated tumor initiation when the DNA damage response and repair (DDR) or mismatch repair (MMR) is impaired.102,103,104 Endogenous threats such as oncogenes or cellular metabolite-mediated DNA replicative stress, or exogenous damage such as chemical agents or irradiation-mediated genotoxic stress, both can lead to DNA double-strand breaks or mitotic damage, further impacting tumor development and therapy response10,11 (Figure 3).

Tumors with CIN exhibit typical numerical or structural chromosomal abnormalities such as formation of micronuclei or heterogeneous aneuploidy and karyotypes.105 Increasing studies reported that the micronuclei-induced immune responses also shape the anti-tumor immunity. Cancer cells with inactivated BRCA1 or BRCA2 exhibit elevated accumulation of micronuclei in the context of DNA repair defects. cGAS localizes within the ruptured micronuclei to initiate the intrinsic IFN responses, which offers potential synergy between cGAS-STING agonists with DDR inhibitors to enhance the anti-tumor immunity.10,106,107

MSI are short nucleotide repeats scattered through the genome. DNA replication errors can occur at sites of DNA polymerase slippage and MSIs are thus more prone to mutation than those non-repetitive regions.100 The MMR system is involved in the surveillance and repair of the errors during DNA replication and recombination.108 MSI-high or MMR-deficient cancer phenotypes, especially endometrial and colorectal carcinoma, usually exhibit high tumor mutational burden (TMB). The TMB-generated neoantigens present high relevance to immunotherapies.108,109,110,111 However, some MSI-high patients are not responsive to the ICB therapy by anti-PD-L1 or anti-CTLA4 antibody, despite the fact their neoantigens are similar to the responding group.111,112,113 A recent report reveals that MSI-high tumor model originated from the essential MMR gene Mlh1 deficiency (dMLH1) exhibits the constant activation of cGAS-STING axis with elevated IFN immune signaling activity as the result of cytosolic DNA accumulation. The dMLH1-positive tumors could stimulate intratumor CD8+ T responses and promote the efficiency of ICB treatment. The study further screened the cGAS expression in 30 kinds of human dMLH1-positive cancer cell lines and found that their cGAS expression is mostly impaired, which partially explains the ICB therapy resistance of some dMMR tumors.114

Clinical exploitations of cGAS-STING agonists for tumor therapy

Agonists of cGAS-STING pathway have been extensively studied as either a stand-alone or axillary therapeutics for immunotherapy. Current designs of cGAS-STING agonists can be divided into two major categories: CDNs and non-nucleotide factors.12 CDNs are usually cGAMP and cGAMP surrogates, while those non-nucleotide factors including synthetic molecules, metal ions and gut microbiota.37,115,116 The mechanisms and therapeutic applications of typical cGAS-STING agonists are detailed in the sections below.

cGAMP and its derivatives

Common forms of CDNs under preclinical investigations include 2′3′-cGAMP, 3′3′-cGAMP, cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP), and c-di-AMP (CDA), among which the 2′3′-cGAMP has been identified as major STING agonists in invertebrates.117 The anti-tumor potential of these CDNs has been tested and validated in several reports (Tables S1 and S2). In the metastatic breast cancer model, c-di-GMP administration almost eliminated metastasis in combination with the cancer vaccine treatment. The STING agonist significantly improved antigen-specific DC-mediated cross-presentation and T cell responses.118 In an improved CAR-T therapy targeting the heterogeneous solid tumors, the in situ delivery of c-di-GMP could potently promote the CAR-T cell response by converting the immunosuppressive TME into immune-inflamed ones, resulting in effective tumor eradication.98 Administration of 2′3′-cGAMP has been demonstrated to induce potent DC maturation, presentation, and CD8+ T cell response in combination with PD-L1 blockade or tumor vaccination in several pre-clinical mouse models.119,120 Stazzoni et al.121 recently developed two cGAMP-derivatives including dideoxy-2′,3′-cGAMP and dideoxy-2′,3′-cAAMP. Dideoxy-2′,3′-cAAMP showed potent anti-tumor ability with strong induction of host innate immune responses. Among the cGAMP analogues, dithio-(Rp, Rp)-2′,5′–3′,5′-c-diAMP sodium salt (RR-CDA, also known as ADU-S100 and MIW815) showed sound effects in several pre-clinical and clinical trials in treating solid tumors by inducing systemic anti-tumor immunity to efficiently eliminate tumor cells122,123,124 (Tables S1 and S3). However, the poor stability and permeabilization of natural or the synthetic cGAMP and analogues limit their application in the clinics.

Non-nucleotide factors

Currently, the most common non-nucleotide CDNs include flavonoid 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) and several other synthetic small molecules. The treatment of DMXAA, a repurposed anti-angiogenic agent, has achieved efficient tumoricidal effects in several pre-clinical tests.125,126 However, this STING agonist did not improve the outcome on carboplatin and paclitaxel-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in a phase III trial127 (Table S3). DMXAA could specifically bind to and stimulate mouse STING but not the human STING,128,129 which might cause its failure in these clinical trials. The antiviral agents 10-carboxymethyl-9-acridanone, C11, G10, BNBC, and CF501 could be used as direct or indirect STING agonists.130,131,132,133,134 Additionally, some synthetic non-nucleotide CDNs could also elicit effective STING agonism. For example, SR-717, a carboxylic acid-containing analog of cGAMP, efficiently activates STING-dependent anti-tumor activity in a murine B16 tumor model.135 MSA-2 is another potent agonist that could be orally administered to efficiently eliminate tumors by inducing anti-tumor responses.136 Ramanjulu et al. identified a small-molecule-amidobenzimidazole (ABZI) through high-throughput screening and created linked ABZI dimers (diABZIs) via molecular engineering, which displayed enhanced binding affinity to STING and thus possessed greater immunostimulatory potential137 (Table S1).

Interestingly, transition metal ions such as manganese ions (Mn2+) and zinc ions (Zn2+) are found to be potent STING agonists, which may significantly facilitate antigen presentation, CD4+ CD8+ T cell activation and adaptive immune responses.37,115,138 Jiang’s group first discovered that Mn2+ could substantially promote cGAS activation even when the dsDNA abundance was at a low level (Wang et al., 2018). Protein crystallography studies further revealed that Mn2+ directly bound to cGAS and induce a series of conformational changes in cGAS to expose its active sites.33 Du et al.37 found that Zn2+ could enhance the enzymic activity of cGAS to produce cGAMP, even when the dsDNA concentration was below the usual sensing threshold through facilitating the formation of cGAS-DNA liquid droplets. Mn2+ shows pronounced capability to overcome the resistance to transforming growth factor β/PD-L1-targeting YM101 antibody in several immune desert tumor-bearing mouse models, which efficiently converted the immune desert TME into the immune-inflamed ones and augmented the response effects of YM101 treatment in eradicating the tumors.139 In a recent clinical trial, intranasal administration or inhalation of MnCl2 in 23 patients with advanced metastatic solid tumors evidently improved their therapeutic response to PD-1 blockade and relieved the resistance to chemotherapy or radiotherapy via augmenting the production of anti-tumor cytokines, including IFN-I, IL-6, and TNF-α115 (Table S2).

The gut microbiota is another potential target to trigger cGAS-STING-IFN signaling activity through the release of DNA-containing membrane vesicles.140 These phenomena have been applied for cancer immunotherapy in the murine models of colorectal cancer and melanoma via oral administration of live lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in combination with anti-PD-1 antibody.141

Nanotechnology-enabled cGAS-STING stimulation for immunotherapy

Using systematically administered cGAS-STING agonists to boost cancer immunotherapy has achieved considerable benefits in pre-clinical and clinical tests. However, it may also enhance the risk of overwhelming systemic immune responses, which could be life threatening in some extreme cases.142,143 In contrast, natural STING agonists are usually hydrophilic biomolecules with low membrane permeability and blood stability,144 while systemic administration of non-nucleotide agonists may elicit autoimmunity according to recent investigations.135,145 The integration of structurally and functionally tailored nanobiomaterials as carriers for cGAS-STING agonists provides a promising approach to realize precise cGAS-STING signaling-based immunomodulation against pre-determined targets at low systemic toxicity.16 In the section below, we provide a comprehensive summary on the nanotechnology-enabled approaches for cGAS-STING-dependent antitumor treatment based on the designated cellular targets.

Tumor cell-targeted cGAS-STING agonism

DNA-damaging agent-based nanocarrier for cancer cell intrinsic cGAS-STING activation

Ling et al.146 synthesized platinum (II) triphenylamine complexes (Pt1 and Pt2) to activate cGAS-STING in cancer cells. Under light irradiation, Pt1 and Pt2 coordinately damage mitochondria and the nuclear envelope to release dsDNA into cytosol, which stimulated cGAS-STING activation in cancer cells while also inducing pyroptosis. The nanocomplexes triggered substantial antitumor immune responses ex vivo and in vivo.146 Song et al.147 designed M@P@HA nanoparticles (NPs) based on hollow manganese dioxide (H-MnO2) and loaded them with protoporphyrin (PpIX) photosensitizer, and further modified their surface with the CD44 targeting molecule hyaluronic acid (HA). M@P@HA NP could be efficiently taken in by tumor cells via CD44-mediated endocytosis to release PpIX and then generate ROS under light irradiation, which would sequentially damage tumor mitochondria to release mtDNA into the cytosol for triggering the activation of cancer cell intrinsic cGAS-STING-IFN-I signaling, leading to the coordinated release of IFN-I, dsDNA, and Mn2+ into the TME. These immunostimulatory species would then induce the polarization of macrophages into M1-type and activate CD8+ T cell anti-tumor responses, eventually suppressing tumor growth.147 Hafnium oxide NP NBTXR3/Hensify has been clinically approved by the European Medicines Agency as a radio-sensitizer for treating locally advanced soft tissue sarcoma in April of 2019.148 NBTXR3 enhanced the radiation-mediated antitumor immunity, which might be partially dependent on the DNA damage induced-cancer-cell intrinsic cGAS-STING-IFN-I signaling.149 Several clinical trials are currently underway for investigating the treatment of intratumorally injected NBTXR3/Hensify for other solid tumors including advanced squamous cell carcinoma (NCT01946867), prostate cancer (NCT02805894), and lung cancer in combination with immunotherapy (NCT03589339).150

Metal ion-integrated nanocarriers for cancer cell intrinsic cGAS-STING activation

Zn-based nanoagonists

Cen et al.151 reported that ZnS could be integrated into BSAs to obtain biostable NPs. After reaching the acidic TME, ZnS could be released from the BSA carriers in an on-demand manner and trigger ROS-mediated mtDNA leakage into the cytosol, which could cooperate with the Zn2+-dependent cGAS activation and readily produce IFN-I and pro-inflammatory cytokines. These pro-inflammatory cytokines recruited and activated DCs and CD8+ T cells within TME, leading to successful induction of strong antitumor immune responses to inhibit the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. The cGAS-STING stimulatory function of the protein-based Zn-incorporated NPs could also cooperate with PD-L1 antibody to more effectively inhibit tumor growth, metastasis, and relapse.151

Mn-based nanoagonists

Lin et al.152 developed an Mn-incorporated tumor-specific cGAS-STING nanoactivator by integrating DOX into phospholipid (PL)-coated amorphous porous manganese phosphate (PL/APMP-DOX NPs). After uptake by tumor cells, the NPs were disintegrated by phospholipase and acidic pH to release DOX and Mn2+, which synergistically enhance anti-tumor CD8+ T cell-mediated immune responses.152 Sun et al.153 constructed MnO-based NPs and modified their surface with tumor-homing iRGD peptides. The NPs could release Mn2+ after entering tumor cells in response to the lysosomal acidic stimulus. Under magnetic resonance imaging guidance, Mn2+ not only mediated the Fenton-like reaction for ROS induction, but also activated tumor-intrinsic cGAS-STING signaling to reduce their immune evasion capacity, which excellently promoted the efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapy for tumor regression through enhancing cytotoxic T lymphocyte infiltration.153 Alternatively, Mn-containing alginate nanocarriers and titanium carbide Mxene modified with Mn2+-containing ovalbumin (OVA) were prepared for post-radiotherapy (RT) immune stimulation. The RT-mediated DNA damage and Mn2+ supplementation cooperatively induced potent post RT anti-tumor immunity through activating cGAS-STING pathway.154,155 Li et al.156 designed polymer micelles (PPIR780-ZMS) by integrating IR780 dye and manganese zinc sulfide NPs (ZMS) into a micellar nanostructure. The release of ZMS from the NPs could be controlled by external NIR trigger. Mn2+ boosted the ROS generation under NIR stimulation in cancer cells and subsequently augmented danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) release, which reshaped the immunosuppressive TME into a pro-inflammatory milieu to eradicate tumors and prevent pulmonary metastases through Mn2+-mediated cGAS-STING activation.156

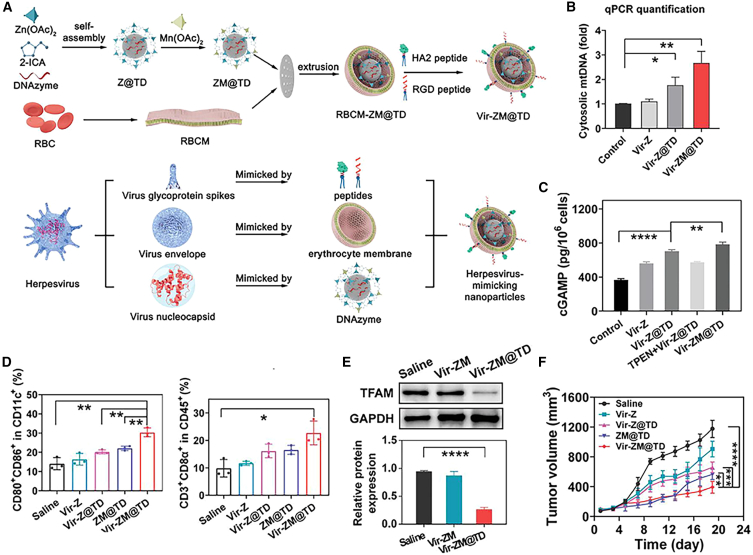

By mimicking the virus-mediated immune regulation mechanism, Xiu Zhao et al. developed a herpesvirus-like NP (Vir-ZM@TD) for virus-based immunotherapy. The nanoplatform was prepared by complexing zeolitic imidazolate framework-90 with Mn2+ and molecularly engineered DNAzymes to specifically degrade the mRNA of transcription factor A, mitochondrial (TFAM), afterward its surface was modified with erythrocyte membrane, RGD and HA2 peptides. The Vir-ZM@TD is structurally resemblant to herpesvirus and could enter tumor cells similar to the viral infection process, subsequently causing TFAM deficiency to elicit mtDNA stress. Meanwhile, the concurrently released Mn2+ would efficiently stimulate the cGAS-STING mediated anti-tumor immune response157 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Vir-ZM@TD mediates antitumor immune responses by Mn-dependent cGAS activation and mtDNA release

(A) Preparation procedures of Vir-ZM@TD. (B) Cytosolic mtDNA levels after different treatment as an indicator for Vir-ZM@TD-mediated neoantigen release. (C) cGAMP production in 4T1 cells after different treatment. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of DC maturation (CD80+/CD86+) and proliferation of CD8+ T cells in 4T1 tumors after various treatments. (E) Immunoblotting analysis of TFAM expression in 4T1 tumors after indicated treatments. (F) Tumor growth curves for assessing the antitumor efficacy of various treatments. Reproduced under the terms of the CC BY license.157

Immune cell-targeted delivery of nanointegrated cGAS-STING agonists

CDNs such as cGAMP, bacterium-derived c-di-GMP, and CDA could bind with mammal STING and induce its polymerization for activating the downstream immune cascade.158 The clinical translational potential of endogenous CDNs is very limited. For example, 2′3′ cGAMP has poor stability in vivo as it is rapidly hydrolyzed by ENPP1. Therefore, a variety of phosphorothioate and diphosphorothioated analogs of 2′,3′-cGAMP such as 2′-5′, 3′–5′phosphodiester ligated 2′,3′-cGSASMP, and Rp, Rp-2′,3′-c-diAMPSS (ADU-S100) with enhanced hydrolysis resistance have been developed for prolonged STING activation.159 However, it is still very difficult for these chemically engineered CDNs to accumulate in tumors and enter designated cellular targets, especially for the tumor-residing APCs as they are relatively small populations in the TME. However, elevating the dose of these CDNs might cause serious side effects. Interestingly, the application of drug delivery nanotechnology may help to address these critical challenges.

Biomolecular STING agonist-incorporated nanostructures for APC-targeted delivery

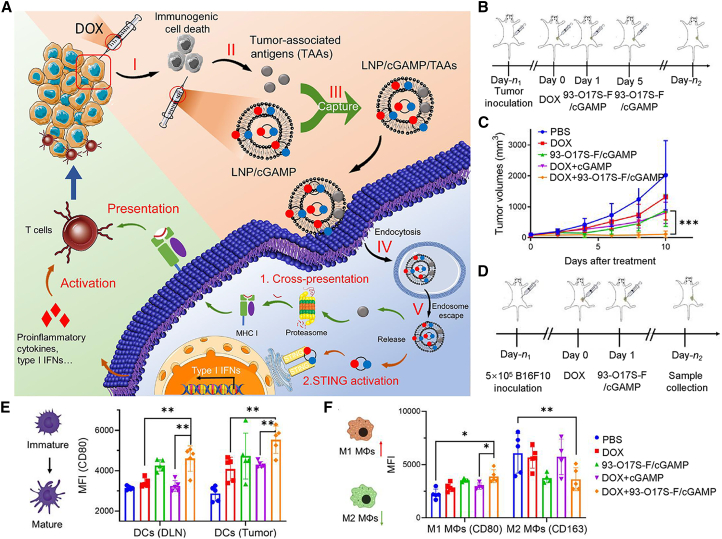

Self-assembled nanostructures based on naturally occurring or synthetic substances are some of the most extensively studied nanocarriers for the delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs, small interfering RNA mRNA vaccines or immune checkpoint inhibitors,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167 which are marked with good biocompatibility, long circulation stability, low toxicity, and versatile surface modification chemistry, presenting substantial potential as cGAMP carriers for cancer immunotherapies.168,169,170,171 For example, Chen et al.172 developed cGAMP-loaded lipid NPs (LNPs/cGAMP) and injected them into doxorubicin (DOX)-pretreated tumors for enhanced immunotherapy. DOX could induce the immunogenic cell death (ICD) of tumor cells and release abundant tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), which were captured by LNPs/cGAMP and subsequently efficiently taken in by APCs. Here the TAAs were degraded for major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I)-mediated presentation to the naive T cells, while cGAMP induced STING-dependent type I IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, leading to cooperatively enhance effector T cell activity172 (Figure 5). Recently, Shae et al.173 designed cGAMP incorporating endosomolytic polymersomes for the targeted delivery of cGAMP to cytosol of immune cells. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-[(2-diethylaminoethyl methacrylate)-co-(butyl methacrylate)-co-(pyridyl disulfide ethyl methacrylate)] (DBP) copolymers was synthesized through the sequential transfer polymerization of fragmentation chain, and integration of pH-sensitive 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate groups and butyl methacrylate (BMA) moieties to enable endosomal escape. The STING-activating NPs (STING-NPs) was eventually formulated via a modified direct hydration method. STING-NP administration potently augmented the STING signaling in TME and tumor-draining lymph nodes via enhancing cytosolic delivery of cGAMP to APCs, which inflamed the poorly immunogenic TME to improve the antitumor immune response.173 Similarly, several LNPs based on PEGylated lipids have been synthesized to incorporate 2′,3′-cGSASMP, cdGMP or the modified phosphorothioate analogs of 2′,3′-cGAMP (CDN), which displayed good tumoral penetration with the predominant uptake by CD11c+ monocytes/macrophages/DCs to reprogram immune cells in the immunosuppressive TME into pro-inflammatory phenotype, which resulted in potent cytotoxic effects of CD8+ T and NK cells.165,166,167 By exploring the intrinsic DC-binding affinity of liposomes, Aatman S. Doshi et al. developed a liposomal ADU-S100 (SA) formulation modified with CLEC9A-targeting peptide for DC-specific STING stimulation, which could induce robust anti-tumor efficacy while reducing the off-target toxicities either when administered alone or in combination with PD-L1 blockade.174

Figure 5.

LNPs/cGAMP improve anti-tumor efficacy by activating the cGAS-STING signaling in major APC population to promote T cell-mediated immune responses

(A) Schematic illustration of LNP/cGAMP-mediated activation of immune responses in TME. (B and C) Scheme of LNPs/cGAMP administration and treatment-induced volume changes of B16F10 tumors on mouse models. (D–F) Treatment scheme for LNP/cGAMP-mediated immunotherapy (D) and flow cytometry-based evaluation of DC maturation from tumors and draining lymph node (E) and tumor-residing macrophage polarization (CD80+ M1, and CD163+ M2) (F). Reproduced under the terms of the CC BY license.172

Luo et al.175 recently designed and synthesized a series of 2′3′-cGAMP surrogates by coordinating AMP and GMP with lanthanide ions. These NPs showed good binding affinities with human and mouse STING, and potently stimulated IFN-I responses in vitro and in vivo. The authors further constructed cGAMP-NP nanovaccines encapsulated with the OVA antigens. After subcutaneous treatment, the nonvaccines could be efficiently internalized by intratumoral APCs including DCs and macrophages to enhance their ability of MHC-I-dependent antigen cross-presentation and maturation, which induced antitumor humoral and cellular immunity in B16F10-OVA tumor bearing mouse models.175 Gao’s laboratory surprisingly found that a polymeric substance with a cyclic seven-membered ring (PC7A) could trigger STING-dependent immune responses. As a polyvalent STING agonist, PC7A binds to STING to induce its condensation for immune activation without affecting its cGAMP-binding affinity. PC7A also disrupts the endosomal membrane to delay the degradation of STING. PC7A administration in melanoma, colon cancer, and human papilloma virus-E6/E7 tumor-bearing mice caused strong vaccine-like effects, including enhanced production of type I IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as a potent cytotoxic anti-tumor T cell response, which efficiently retarded tumor growth when used as a stand-alone therapy or in combination with cGAMP treatment, PD-1 blockade, or IR treatment.145,176,177 CpG-hybridized PC7A has been recently introduced into bacterial membrane-coated NPs (BNPs) as an adjuvant to specifically stimulate APC uptake, of which the outer membrane was modified with maleimide (Mal) for capturing the cancer neoantigen through electrostatic interaction. The BNP-Mal showed pronounced immunostimulatory effects on mice bearing B78 melanoma or NXS2 neuroblastoma by triggering type I IFN response and inducing NK and T cells. Moreover, the therapeutic effect of BNP-Mal could be further amplified through the conjunctional use of IR treatment.178

Interestingly, Li et al.179 developed an ultrasound-guided cancer immunotherapy platform by incorporating cGAMP and anti-CD11b antibodies into spermine-modified dextran-coated microbubbles (ncMBs). After local injection into the tumors, ncMBs were predominantly captured by tumor-infiltrated CD11b+ APCs. The subsequent ultrasonication of the tumors would further trigger the release of cGAMP into the cytosol of APCs, thus boosting their STING signaling-dependent cross-presentation ability to enhance the infiltration of proliferation of CD8+/CD4+ and CD8+/IFNγ+ T cells within the TIME, resulting the systemic anti-tumor immune responses in combination with PD-1 blockade.179 Notably, Hammond’ s group prepared a cGAMP delivery platform using transmembrane domain-deleted STING protein (STINGΔTMD). cGAMP and STINGΔTMD could self-assemble into biostable NPs that retain the bioactivity of STING protein, which significantly suppressed tumor growth through the induction of robust antigen-mediated CD8+ T cell immune responses in combination with OVA immunization.180 Furthermore, Sun et al.181 constructed the CP-STINGΔTMD genetically fused with cell-penetrating protein (Omomyc) as the nanocarriers for enhanced cGAMP delivery. The intratumoral administration of CP-STINGΔTMD achieved the efficient tumoricidal effects via induction of potent antitumor immunity.181 These STING protein-based vehicles for delivery of STING agonists provide novel immunotherapy strategy for treating STING-silenced tumors. In addition, STING-based antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) platform have displayed the clinical translational potential, in which the STING agonists are conjugated to a monoclonal antibody targeting specific tumor antigens through a suitable linker.182,183 Of note, XMT-2056 is a novel ADC for HER2-positive tumor treatment, which is synthesized through conjugating a non-nucleotide CDN (diABZI) with HER2 mono-antibody and capable of triggering potent antitumor immune responses in tumor-residing immune cells with minimal induction of systemic immunity in preclinical trials.182 The clinical phase I study of XMT-2056 for the treatment of HER2-expressing solid tumors is currently recruiting the patients (NCT05514717). It has also obtained approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of orphan drug designation to treat gastric cancer in 2022.

These therapeutic nanosystems offer important insights for the integration of cGAS-STING-targeted immunotherapy with other antitumor modalities to enhance the treatment outcome of solid tumors. However, compared to the abundant evidence of APC-targeted nanointegrated cGAS-STING stimulation concepts, there are few studies concerning the direct delivery of STING agonists into anti-tumor effector immune cells including T, NK, and B cells. The small proportion of these cells within the TME and the lack of selective targetable surface markers prove a significant hurdle to the direct cGAS-STING stimulation in effector cells.

Hydrogel-mediated localized release of biomolecular STING agonists

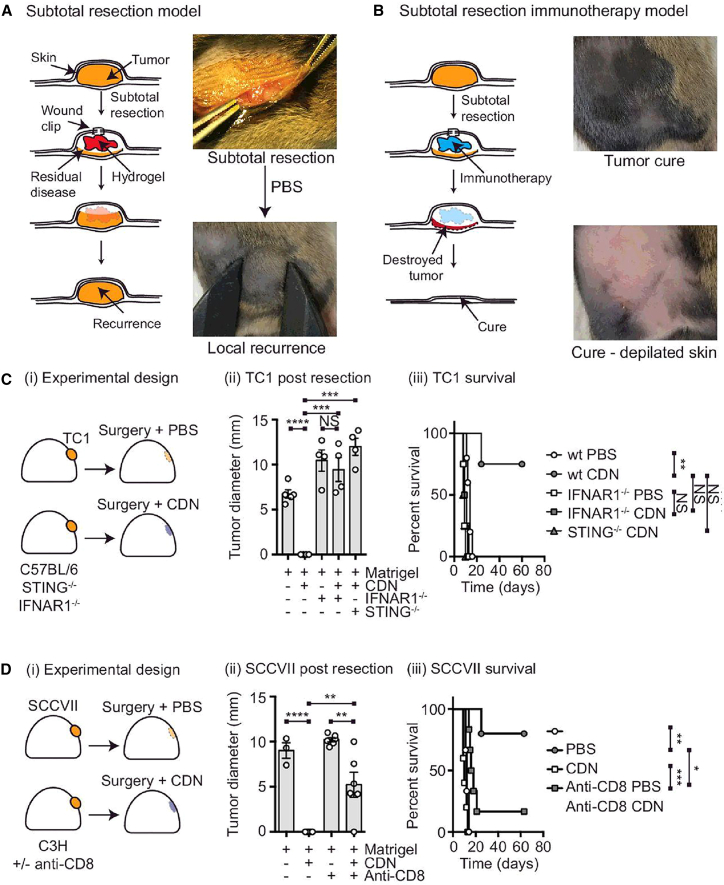

Surgical resection of tumors has dual impact on the tumor immunotherapy. On one hand, the removal of bulk tumors disrupts the immunosuppressive microenvironment to improve the immunotherapy efficacy. In contrast, it also creates a transient immunosuppressive state for wound healing that favors post-resection tumor relapse and metastasis.184 Immunostimulatory hydrogels are a promising platform for the localized treatment of resected tumors,185,186 which allow the facile incorporation of STING agonists for supporting anti-tumor immunity while promoting tissue repair in resected tumors. For instance, Park et al.187 reported a biodegradable hydrogel by cross-linking of HA and covalently conjugated 2′3′-cGAMP onto the biopolymeric backbone. Implanting the cGAMP-incorporated hydrogel onto resected 4T1 tumors evidently prevented tumor recurrence and distal metastasis through STING-dependent activation of CD4+/CD8+ T and NK cells.187 Zhang et al.188 developed a vitamin C (VitC)-based hydrogel system for the tumor-targeted delivery of STING agonist-4 (SA-4, known as diABZi), for which VitC was first modified to self-assemble into injectable hydrogel with wound healing properties and then complexed with SA-4 to form SA@VitC hydrogel. The composite hydrogel could efficiently activate the endogenous immune system to eliminate primary tumors and induce abscopal effect to suppress distal tumors in murine tumor models.188

Multidomain peptides (MDPs) are a class of unique supramolecular biomaterials that could self-assemble into hydrogels, which have demonstrated considerable clinical translational potential for treating resected tumors owing to their high biocompatibility, good bioadhesiveness, pro-healing capacities and pro-hemostatic function.189,190 Leach et al.191 incorporated ADU-S100 into MDP-based hydrogels through nanofiber cross-linking (STINGel), which was then subcutaneously injected into the MOC2-E6E7 tumor mouse models and effectively eradicate the tumors. Similarly, Baird et al.192 exploited the phase transition property of Matrigel (STINGblade), which is liquid like under low temperatures but forms hydrogel-like substances under body temperature, to deliver CDA for the treatment of human papillomavirus+ head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in preclinical mouse models via intratumoral injection (Figure 6). Wang et al.193 conjugated camptothecin (CPT) with iRGD that could self-assemble into supramolecular nanotubes (NTs) in an aqueous solution. Negatively charged CDA would adhere to the surface of positively charged NT through electrostatic interaction to form CDA-NT and become condensed for collection. After tumoral injection, CDA-NT further formed hydrogels and was degraded in response to elevated environmental glutathione (GSH) levels, which released CPT and CDA to induce robust anti-tumor immune response and establish T memory cell-mediated long-term immunity to prevent tumor recurrence.193

Figure 6.

cAGS-STING stimulatory hydrogel enables immunotherapy against resected solid tumors.

(A and B) Schematic illustration of the cGAS-STING stimulatory hydrogel into the post-resection cavity of SCCVII tumor-bearing C3H mice. The hydrogels in panel A and B were incorporated with PBS or CDN, respectively. (C) (i) TC1 tumor-bearing STING−/−, IFNAR1−/−, or wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice implanted with Matrigel containing PBS or CDN in the tumor resection cavity. Tumor size changes and survival percentages were shown in (ii) and (iii). (D) (i) Treatment procedure of Matrigel on SCCVII tumor-inoculated C3H mice. Tumor size changes and overall survival were shown in (ii) and (iii). Copyright Reproduced under the terms of the CC BY license.192

DNA-damaging agent-based nanocarrier for cGAS-STING stimulation of APCs

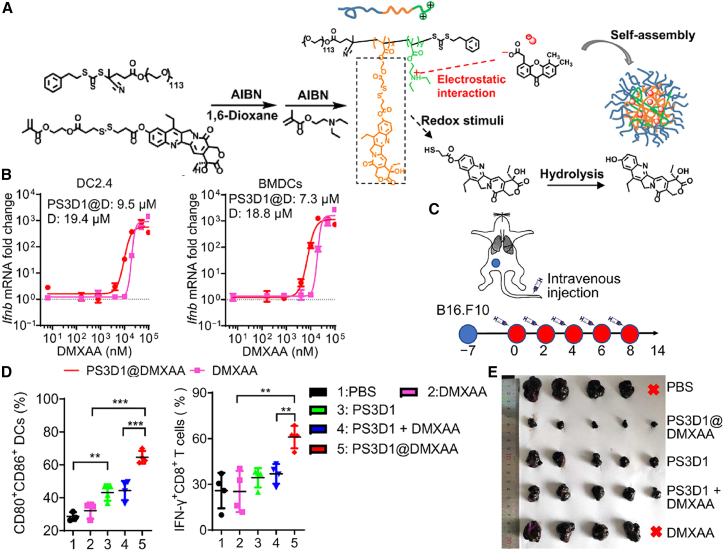

According to recent ex vivo screening results from several DNA damage-inducing chemotherapeutic drugs, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN38) treatment on tumor cells could cause the generation of tumor-derived DNA-containing exosomes, which are discharged into the TME and subsequently taken in by DCs to potently stimulate type I IFN secretion through STING activation. Therefore, SN38 was conjugated onto polymers as building blocks to self-assemble into SN38-NPs. SN38-NPs displayed lower toxicity and greater efficacy compared with free SN38 to induce STING-dependent tumor immunity.194 Similarly, Liang et al.195 developed polymeric NPs using a triblock copolymer substrate for the integration of SN38 and DMXAA via hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions (PS3D1@DMXAA NPs), respectively. PS3D1@DMXAA could be disintegrated in a redox responsive manner in tumor sites, where the released SN38 triggers ICD of tumor cells and subsequently enhances DC uptake of DMXAA for STING-IFN signaling activation. The PS3D1@DMXAA NPs successfully initiated strong antitumor immune responses to inhibit tumor growth in several poorly immunogenic tumor models195 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

PSD31 potently stimulates chemoimmunotherapy responses in murine tumor models

(A) Schematic depiction of PS3D1@DMXAA structure and its synthesis process. (B) Ifnb mRNA expression after treatment with PS3D1@DMXAA NPs and DMXAA in DC2.4 and bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) in the dose-dependent curves. (C) Schematic illustration of the treatment procedures of PS3D1@DMXAA NPs. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of DC maturation (CD80+/CD86+ DCs of CD45+/CD11c+ DCs) in the tumor-draining lymph nodes and IFN-γ producing tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells after 14 days of treatment. (E) Size comparison of B16.F10 tumors after different treatments. Reproduced under the terms of the CC BY license.195

Metal ion-incorporated nanosystems for cGAS-STING stimulation of APCs

Manganese oxide nanomaterials including MnO, MnO2, Mn2O3, Mn3O4, and MnOx are a class of inorganic materials with versatile functions, which have already been applied for both bioimaging and antitumor therapy.196 Typically, Tang et al.197 designed an MnO2-based cGAS-STING agonist by coupling MnO2 NPs with cytotoxic 26-amino-acid peptide-melittin (M-M NPs), which could be readily degraded in the acidic TME to release melittin and MnO2 nanocores. The melittin peptides could directly kill tumor cells through apoptosis induction, while the concomitantly delivered MnO2 could release Mn2+ and oxygen to elevate ROS stress, leading to enhanced cytotoxicity to the tumor cells. Moreover, the released Mn2+ may also stimulate APC maturation through activating cGAS-STING pathway and the subsequent CD8+ T cell anti-tumor immunity in the TME.197 Han’s group developed a pH/GSH dual-responsive H-MnO2 nanostructure for the incorporation of chlorine6 (Ce6)-modified PD-L1 DNAzyme and glycyrrhizic acid (GA). The NPs enabled Mn2+-mediated cGAS-STING signaling in immune cells and PD-L1 inhibition in tumor cells, which could act in a coordinated manner to boost the T cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Furthermore, the concurrently delivered Ce6 could generate abundant ROS under external stimulation to amplify tumor cell apoptosis. Meanwhile, the released GA inhibited Tregs in TME to alleviate immunosuppression therein for further enhancing the immunotherapeutic response.198 Tian et al.199 developed an Mn-phenolic nanoadjuvant for the combinational sonodynamic (SDT)/immune therapy. The nanoadjuvant was prepared through the self-assembly of Mn2+, GSH inhibitor sabutoclax, acidity-responsive phenolic polymer and sonosensitizer components. SDT-mediated ICD effects and Mn2+ release efficiently augmented anti-tumor immunity via promotion of DC maturation as well as sensitizing tumor cells to PD-1 antibody treatment.199

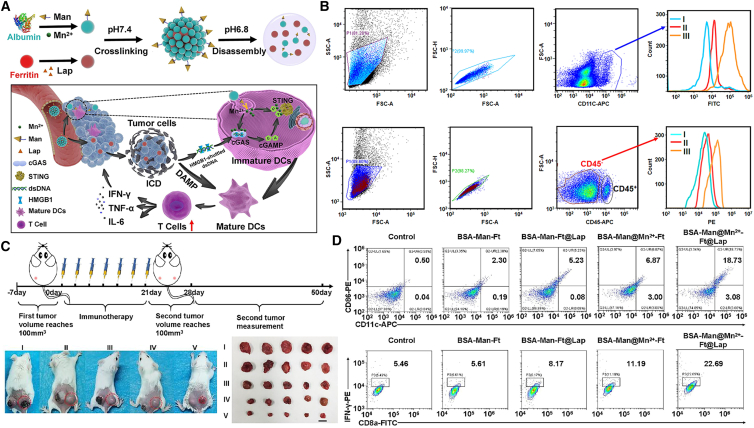

Recently, our group developed protein-based nanoassemblies comprising Mn2+-loaded mannose-modified BSAs (BSA-Man@Mn) and β-Lapachone-loaded ferritin (Ft-LAP) for cooperative stimulation of cGAS-STING signaling in DCs. The BSA-Man@Mn and Ft-LAP units were cross-linked with acid-cleavable Schiff base linkers (BSA-Man@Mn2+-Ft@Lap), which could be disintegrated into singular protein units in the acidic TME. Ft-LAP was taken in by tumor cells through transferrin receptor-mediated endocytosis to induce tumor cell ICD and release dsDNA and other DAMPs into TME, while BSA-Man@Mn was internalized by DCs through mannose receptor-mediated endocytosis to stimulate cGAS-STING activities, thus cooperatively promoting DC maturation and cross-presentation of TAAs for CD8 T cell activation. BSA-Man@Mn2+-Ft-Lap successfully inflamed the poorly immunologic 4T1 tumors for superior anti-tumor immune response200 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

BSA-Man@Mn2+-Ft@Lap mediates potent anti-tumor immunity

(A) Scheme illustration of construction of BSA-Man@Mn2+-Ft@Lap and its activation in the TME to enhance anti-tumor immune response in poorly immunogenic solid tumors. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of the heterogeneous targeting ability of the nanoassembly against APC or tumor cells after its dissociation in TME. (C) BSA-Man@Mn2+-Ft@Lap administration suppressed distal tumors through eliciting systemic antitumor immunity. (D) The nanoassemblies significantly promoted DC maturation and activation of CD8+/IFNγ+ T cells in vivo. Reproduced under the terms of the CC BY license.200

Despite the promising application potential of these nanotechnology-enabled cGAS-STING immunotherapeutics, there are a few safety considerations for the engineered NPs because of their interaction with the host biological systems. For example, the biomolecules in the biological fluids could be attached to the surface of the NPs to form the protein corona, which might drastically change the charge, shape, and size of the NPs to cause toxicity.201 Meanwhile, the NPs can induce protein aggregates or misfolding in plasma to trigger systemic inflammatory reactions or cause host homeostasis disorder.202,203 For instance, gold NPs can induce unfolding of fibrinogen to interact with the Mac-1 (the integrin receptor), which triggers the activation of downstream NF-κB-mediated inflammation.203 Recently, the FDA formally placed a clinical hold on the phase I trial (NCT05514717) of XMT-2056 because of a death report in a patient receiving the initial dose level. This is the grade 5 serious adverse event highlights the potential clinical toxicities of the STING-based immunomodulatory nanotechnologies. In view of the challenges in the clinical trial of XMT-2056, more thorough investigations are warranted regarding the nano-bio interaction, systemic immunogenic reactions, and Fc receptor-mediated tissue toxicities caused by the instability and off-target side effects of the ADC drugs, which should provide critical insights for future development in STING agonist-based tumor therapy. Hence, it is necessary to establish suitable animal model system to thoroughly investigate their nano-biointeraction under clinically relevant conditions. The doses of usage should be considered as well to establish clinical standards of nanomedicine administration to minimize their toxicities.

Concluding Remarks

The cGAS-STING pathway is a vital defense system against microbial infection and autoimmune diseases. Extensively studies reported that cGAS-STING pathway could function as a mechanism of adjuvanticity to stimulate immunotherapies. However, the regulatory roles of cGAS-STING pathway in anti-tumor responses have not been fully elucidated, as its immunological impacts may vary significantly in the context of different tumor indications and stages of progression. Under certain circumstances, cGAS-STING could even promote tumor development and metastasis because of the non-canonical activation of its downstream molecules-NF-κB in tumor cells or immune cells in response to endogenous and exogenous genotoxic stressors.204,205,206 Meanwhile, there are also reports that DNA damage-mediated cGAS-STING activation would induce the production of pro-tumor cytokines and potentially compromise the immunotherapeutic efficacy. It is, therefore, important to figure out the genotype background and the immune infiltration state within the TME for deciding the applicability of cGAS-STING stimulating treatment. Therefore, these issues impede the clinical translation of cGAS-STING-targeted immunotherapeutic nanomedicine, while the experiences from successfully translated chemo- and radiotherapy NPs (including liposome, micelle, polymeric, protein-based nanoassemblies, and inorganic NPs) could be helpful for overcoming these challenges.150

cGAS-STING agonists provide an alternative for enhancing tumoral DC maturation and cytotoxic T cell or NK cell activation. However, these agents would cause severe side effects caused by the uncontrolled systemic immune stimulation. Meanwhile, the overactivation of cGAS-STING pathway might dampen the antitumor function of T cells through inducing apoptosis.207,208,209 Gulen et al.208 have reported that the high expression of STING intensified signaling strength, which induced the expression of IRF3- and p53-dependent proapoptotic genes. This work uncovered an STING hyperactivation-based strategy for treatment of T cell-derived malignancies through induction of cell death, while it also raised concerns for the administration of high concentrations of STING agonists in solid tumors, which might attenuate the antitumor abilities of tumor-infiltrating T cells.208 Interestingly, Sivick et al.209 also mentioned that the intra-tumoral injection of a low-dose of STING agonist (ADU-S100) elicited potent antitumor responses of tumor-residing T cells and activation of local immunity, while high-dose administration induced the activation of systemic immunity to eradicate the injected solid tumors without inducing CD8+ T cell expansion, which might be due to the STING-mediated T cell apoptosis.209 The dosage of STING agonist during antitumor immunotherapy should be considered for the optimal activation of effector T cells. Moreover, most of the molecules are nonpermeable to cell membrane and present short biological half-life in vivo. Drug delivery nanotechnology provides an effective approach to control the dosage, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety risks of cGAS-STING agonists under clinically relevant conditions. In addition, the multifunctionality of nanobiomaterials offers new opportunities to develop combinational therapies integrating cGAS-STING stimulatory treatment and other common antitumor modalities. From a clinical perspective, there are several major issues that must be considered when developing cGAS-STING-stimulating immunotherapeutics.

As already discussed above, the TME is a complex ecosystem comprising many cell populations with distinct biological properties and functions. Consequently, it is important to ensure that the cGAS-STING agonists are properly delivered to the selected cellular targets. Current insights show that the uptake efficiency of nanobiomaterials by target cells is largely determined by their size, shape, stiffness, and surface chemistry, warranting rational tailoring of the physical and chemical properties of the nanocarrier systems. Most of the currently studies focus on the stimulation of cGAS-STING activities in APCs such as DCs and macrophages to enhance their maturation and antigen cross-presentation capacity. However, it should also be considered that the initiation and maintenance of antitumor immunity is a highly complex process involved many cell populations and biological events. For instance, solid tumors are usually in an immunosuppressed state with insufficient infiltration of immune cells and compromised immune functions. Consequently, it is therapeutically plausible to combine cGAS-STING agonists with other supportive treatment to ameliorate the immunosuppression in TME, such as normalization of the dense and rigid extracellular matrices to facilitate the homing of immune cells and immune checkpoint blockade therapy to prevent T cell exhaustion.

Recent studies abundantly demonstrate the promotional effect of cGAS-STING agonism on the antitumor function of endogenous CD8 T and NK cells. However, reports that investigate the potential positive impact on CAR-T or CAR-NK therapy in the clinics are still scarce. Indeed, there are already several preliminary studies showing that STING agonism potently augments anti-tumor activity of CAR-T and CAR-NK cells in vitro and in vivo.74,75,210,211 For instance, Smith et al.98 recently developed an implantable device manufactured by collagen-targeting peptide-modified polymerized alginate, which was then used to encapsulate CAR-T cells and microparticles with anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and anti-CD137 antibodies on the surface and cdGMP in the cores. After direct implantation onto the surface of pancreatic cancer and melanoma on mice, biopolymer scaffolds were degraded to release CAR T cell and cdGMP into the TME to efficiently eliminate tumors and induce potent anti-tumor immunity.98 It would be of clinical interest to combine CAR-T or CAR-NK therapy and STING agonists for tumor treatment.

In addition, the multifunctionality of nanobiomaterials offers new opportunities to develop combinational therapies integrating cGAS-STING stimulatory treatment and other common antitumor modalities. The rational combination of STING agonists and tumor vaccines, topoisomerase inhibitors or anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies has demonstrated evident advantages over pristine cGAS-STING agonists to improve the eventual immunotherapeutic outcome. It is highly anticipated that the concurrent stimulation of cGAS-STING and other immune signaling pathways such as toll-like receptors, retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors, absent in melanoma 2, and so on, may overcome impaired immune functions in the TME and yield greater antitumor efficacy, although the design and safety evaluation of these combinational immunostimulatory strategies still need to be thoroughly investigated under clinically relevant conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32102683, 32122048, 11832008, 92059107, and 51825302), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2021CDJLXB001, 2021CDJZYJH-002, and 2022CDJXY-004), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M710525), Chongqing Outstanding Young Talent Supporting Program (cstc2021ycjh-bgzxm0124), Returning Overseas Scholar Innovation Program (CX2021098), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Municipal Government (cstc2021jcyj-jqX0022, and cstb2022nscq-msx1252).

Author contributions

Z.L., M.H.L., and Y.Q.L conceptualized this review. Y.Q.L and M.H.L wrote the paper. F.Y. and Y.Q.L drew the pictures. All authors helped with the revision of the draft.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.03.026.

Contributor Information

Menghuan Li, Email: menghuanli@cqu.edu.cn.

Zhong Luo, Email: luozhong918@cqu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Harapas C.R., Idiiatullina E., Al-Azab M., Hrovat-Schaale K., Reygaerts T., Steiner A., Laohamonthonkul P., Davidson S., Yu C.H., Booty L., Masters S.L. Organellar homeostasis and innate immune sensing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022;22:535–549. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00682-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decout A., Katz J.D., Venkatraman S., Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21:548–569. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanpouille-Box C., Demaria S., Formenti S.C., Galluzzi L. Cytosolic DNA sensing in organismal tumor control. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:361–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Justice J.L., Cristea I.M. Nuclear antiviral innate responses at the intersection of DNA sensing and DNA repair. Trends Microbiol. 2022;30:1056–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2022.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ablasser A., Chen Z.J. cGAS in action: Expanding roles in immunity and inflammation. Science. 2019;363 doi: 10.1126/science.aat8657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopfner K.P., Hornung V. Molecular mechanisms and cellular functions of cGAS-STING signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:501–521. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFarland A.P., Luo S., Ahmed-Qadri F., Zuck M., Thayer E.F., Goo Y.A., Hybiske K., Tong L., Woodward J.J. Sensing of bacterial cyclic dinucleotides by the oxidoreductase RECON promotes NF-kappaB activation and shapes a proinflammatory antibacterial state. Immunity. 2017;46:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X., Bai X.C., Chen Z.J. Structures and mechanisms in the cGAS-STING innate immunity pathway. Immunity. 2020;53:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu C.H., Davidson S., Harapas C.R., Hilton J.B., Mlodzianoski M.J., Laohamonthonkul P., Louis C., Low R.R.J., Moecking J., De Nardo D., et al. TDP-43 triggers mitochondrial DNA release via mPTP to activate cGAS/STING in ALS. Cell. 2020;183:636–649.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisländer T., Groelly F.J., Tarsounas M. DNA damage and cancer immunotherapy: a STING in the tale. Mol. Cell. 2020;80:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouw K.W., Goldberg M.S., Konstantinopoulos P.A., D'Andrea A.D. DNA damage and repair biomarkers of immunotherapy response. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:675–693. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-17-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flood B.A., Higgs E.F., Li S., Luke J.J., Gajewski T.F. STING pathway agonism as a cancer therapeutic. Immunol. Rev. 2019;290:24–38. doi: 10.1111/imr.12765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanpouille-Box C., Hoffmann J.A., Galluzzi L. Pharmacological modulation of nucleic acid sensors - therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:845–867. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger G., Marloye M., Lawler S.E. Pharmacological modulation of the STING pathway for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2019;25:412–427. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo J., Huang L. Nanodelivery of cGAS-STING activators for tumor immunotherapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022;43:957–972. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2022.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent M.P., Navidzadeh J.O., Bobbala S., Scott E.A. Leveraging self-assembled nanobiomaterials for improved cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:255–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ju Y., Liao H., Richardson J.J., Guo J., Caruso F. Nanostructured particles assembled from natural building blocks for advanced therapies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022;51:4287–4336. doi: 10.1039/d1cs00343g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma X., Li S.J., Liu Y., Zhang T., Xue P., Kang Y., Sun Z.J., Xu Z. Bioengineered nanogels for cancer immunotherapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022;51:5136–5174. doi: 10.1039/d2cs00247g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cong V.T., Houng J.L., Kavallaris M., Chen X., Tilley R.D., Gooding J.J. How can we use the endocytosis pathways to design nanoparticle drug-delivery vehicles to target cancer cells over healthy cells? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022;51:7531–7559. doi: 10.1039/d1cs00707f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalski S., de Oliveira Mann C.C., Stafford C.A., Witte G., Bartho J., Lammens K., Hornung V., Hopfner K.P. Structural basis for sequestration and autoinhibition of cGAS by chromatin. Nature. 2020;587:678–682. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2748-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kujirai T., Zierhut C., Takizawa Y., Kim R., Negishi L., Uruma N., Hirai S., Funabiki H., Kurumizaka H. Structural basis for the inhibition of cGAS by nucleosomes. Science. 2020;370:455–458. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyer J.A., Spangler C.J., Strauss J.D., Cesmat A.P., Liu P., McGinty R.K., Zhang Q. Structural basis of nucleosome-dependent cGAS inhibition. Science. 2020;370:450–454. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pathare G.R., Decout A., Glück S., Cavadini S., Makasheva K., Hovius R., Kempf G., Weiss J., Kozicka Z., Guey B., et al. Structural mechanism of cGAS inhibition by the nucleosome. Nature. 2020;587:668–672. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Z., Ni G., Damania B. Innate sensing of DNA virus genomes. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018;5:341–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-092917-043244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan X., Sun L., Chen J., Chen Z.J. Detection of microbial infections through innate immune sensing of nucleic acids. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;72:447–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriyama M., Koshiba T., Ichinohe T. Influenza A virus M2 protein triggers mitochondrial DNA-mediated antiviral immune responses. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4624. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12632-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aguirre S., Luthra P., Sanchez-Aparicio M.T., Maestre A.M., Patel J., Lamothe F., Fredericks A.C., Tripathi S., Zhu T., Pintado-Silva J., et al. Dengue virus NS2B protein targets cGAS for degradation and prevents mitochondrial DNA sensing during infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]