Abstract

SLP1int is a 17.2-kb genetic element that normally is integrated site specifically into the chromosome of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). The imp operon within SLP1int represses replication of both chromosomally integrated and extrachromosomal SLP1. During mating with S. lividans, SLP1int can excise, delete part of imp, and form a family of autonomously replicating conjugative plasmids. Earlier work has shown that impA and impC gene products act in concert to control plasmid maintenance and regulate their own transcription. Here we report that these imp genes act also on a second promoter, Popimp (promoter opposite imp), located adjacent to, and initiating transcription divergent from, imp to regulate loci involved in the intramycelial transfer of SLP1 plasmids. spdB1 and spdB2, two overlapping genes immediately 3′ to Popimp and directly regulated by imp, are shown by Tn5 mutagenesis to control transfer-associated growth inhibition (i.e., pocking). Additional genes resembling transfer genes of other Streptomyces spp. plasmids and required for SLP1 transfer and/or postconjugal intramycelial spread are located more distally to Popimp. Expression of impA and impC in an otherwise competent recipient strain prevented SLP1-mediated gene transfer of chromosomal and plasmid genes but not plasmid-independent chromosome-mobilizing activity, suggesting that information transduced to recipients after the formation of mating pairs affects imp activity. Taken together with earlier evidence that the imp operon regulates SLP1 DNA replication, the results reported here implicate imp in the overall regulation of functions related to the extrachromosomal state of SLP1.

Streptomyces spp. are gram-positive soil bacteria that undergo a complex cycle of morphological differentiation and synthesize multiple medically and industrially useful secondary metabolites (11, 12). Plasmids isolated from Streptomyces species (reviewed in reference 17) include autonomous circular plasmids (e.g., pIJ101 [24], pSN22 [21], and pJV1 [32]) and linear replicons (40), as well as plasmids generated by site-specific excision of chromosomal DNA segments and capable of reintegrating site specifically into Streptomyces chromosomes (e.g., SLP1 and pSAM2 [reviewed in reference 28]). During their existence as extrachromosomal replicons, most integrating plasmids share with other types of Streptomyces plasmids the ability to undergo conjugal transfer and inhibit transiently the growth of plasmid recipients, yielding zones of slowed growth called pocks (3).

SLP1, which was the first reintegrating plasmid discovered in Streptomyces (4), exists normally as a 17.2-kb plasmidogenic sequence (SLP1int) in the chromosome of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Upon mating of S. coelicolor with S. lividans, a closely related strain which lacks SLP1, SLP1 can excise from the chromosome and transfer to S. lividans, where it can either enter the recipient chromosome or undergo deletion, generating autonomously replicating circular plasmids (28). The integration and excision of SLP1 occur by site-specific recombination between a chromosomal attachment site (attB) and a largely homologous site (attP) on SLP1 and are mediated by two genes, int and xis, whose products resemble, respectively, the integrase and excisase of bacteriophage λ and other temperate phages (7, 8). SLP1int includes a locus, designated imp (inhibition of plasmid maintenance), which can act both in cis and in trans by a mechanism distinct from normal plasmid incompatibility, to prevent propagation of SLP1 as an extrachromosomal element; consequently, existence of SLP1 as a plasmid requires deletion or mutation in imp (15). Two translationally coupled genes within the imp locus, impA and impC, function conjointly to autoregulate their own expression at the imp promoter (Pimp) (34). The impC gene product contains a helix-turn-helix motif and exerts negative regulation over SLP1 replication (15, 34). The ImpA protein has features in common with the GntR family of transcriptional repressors (14, 34), which includes the Kor proteins encoded by Kil-override loci affecting the transfer of certain Streptomyces plasmids (36). Together, ImpA and ImpC can also regulate a promoter located 5′ to xis (6). Collectively, these findings have raised the prospect that imp may have multiple regulatory roles related to the existence of SLP1 in its extrachromosomal state and its behavior as a plasmid (34).

Here we report the cloning and characterization of an imp-regulated promoter that controls SLP1-mediated gene transfer and the identification and characterization of SLP1 genes that govern intermycelial and intramycelial dissemination of the plasmid. Our findings, which support the notion that the imp locus is a master regulator of multiple functions associated with the extrachromosomal state of SLP1, suggest that SLP1-mediated enhanced gene transfer, but not low-frequency mobilization of chromosomal genes, results from decreased imp activity in donors following the formation of mating pairs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. lividans TK64 was used as the Streptomyces host strain. TK23 was used in genetic crosses to assay plasmid transfer and chromosome-mobilizing ability. Escherichia coli DH5α or BRL2288 was used for transformation. E. coli MB117 was used for the delivery of the Tn5 transposon. Streptomyces strains were grown in liquid culture in YEME medium (16) or in solid culture in MY (described in reference 8), R5, or MM (16) medium. Hygromycin, thiostrepton, spectinomycin, and kanamycin were used as described elsewhere (16) to select for resistance to these antibiotics (Hygr, Tsrr, Spcr, and Kanr, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain and plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Streptomyces | ||

| TK64 | S. lividans 66 derivative (pro-2 str-6) (Strr) | 16 |

| TK23 | S. lividans 66 derivative (spc-1) (Spcr) | 16 |

| Stm188 | TK64 attB::pSUM347 (S. lividans TK64 strain expressing impA and impC) | This work |

| Stm189 | TK64 attB::pSUM353 (S. lividans TK64 strain expressing impC) | This work |

| Stm190 | TK64 attB::pSUM354 (S. lividans TK64 strain expressing impA) | This work |

| Stm160 | TK64 attB::pSUM317 | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Life Technologies | |

| BRL2288 | recA56 derivative of MC1061 (F−araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7679 Δ(lac)X74 galU galK hsdR2 (rK− MK−) mcrB1 rpsL (Strr) | Life Technologies |

| MB117 | F− λ−pyrF::Tn5 | This work |

| MB140 | MB117(pSUM50) | This work |

| MB163 | MB117(pSUM101) | This work |

| MB164 | MB117(pSUM102) | This work |

| MB165 | MB117(pSUM103) | This work |

| MB171 | MB117(pSUM109) | This work |

| MB174 | MB117(pSUM112) | This work |

| MB175 | MB117(pSUM113) | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | 39 | |

| pXE4 | pBR322 (5)-SCP2-derived shuttle vector containing a promoterless xylE gene | 18 |

| pIJ303 | Conjugative Tsrr derivative of pIJ101 | 24 |

| pCAO153 | pCAO106 (SLP1 into which pACYC177 [10] was inserted) and containing a Tsrr gene | 29 |

| pSUM50 | Derivative of SLP1.2 (a naturally occurring 14.2-kb SLP1 deletion derivative [4]) that contains a gene encoding Hygr and pBR322 inserted at the unique BamHI site | This work |

| pSUM80 | pXE4 harboring the Kanr gene at the BamHI site | 7 |

| pSUM101 | pSUM50::Tn5 at position 8.6 | This work |

| pSUM102 | pSUM50::Tn5 at position 10.1 | This work |

| pSUM103 | pSUM50::Tn5 at position 11 | This work |

| pSUM109 | pSUM50::Tn5 at position 12 | This work |

| pSUM112 | pSUM50::Tn5 at position 13.1 | This work |

| pSUM113 | pSUM50::Tn5 at position 14.3 | This work |

| pSJH6 | Derivative of pXE4 containing SLP1 Sau3AI (8.10–8.66) fragment inserted at the unique BamHI site | This work |

| pSUM317 | pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) Hygr derivative containing SLP1 attP site | 7 |

| pSUM347 | pBluescript SK+ Hygr derivative containing SLP1 attP site, the impC and the impA gene | This work |

| pSUM353 | pBluescript SK+ Hygr derivative containing SLP1 attP site, the impC gene, and an in-frame deletion in the impA gene | This work |

| pSUM354 | pBluescript SK+ Hygr derivative containing SLP1 attP site and the impA gene | This work |

Brasch and Cohen (7) have shown that expression of the SLP1 Int protein from a transiently existing plasmid can promote stable integration of a coexisting nonreplicating attP-containing plasmid, enabling us to construct strains containing impA and/or impC integrated into the Streptomyces chromosome and expressing the products of these genes. Introduction of these plasmids into S. lividans generated strains Stm188 (expressing both impA and impC), Stm189 (expressing impC), and Stm190 (expressing impA), respectively, under the control of the imp promoter (Table 1).

Transformation, plasmid isolation, and DNA manipulation.

Transformation of Streptomyces was done as described elsewhere (16), using R5 medium; 200 ng of DNA was used in transformation mixes. Plasmids were isolated by using a plasmid DNA isolation kit from Qiagen, Inc. (Valencia, Calif.). Ligations were done as described elsewhere (31), using 5× ligase buffer from Life Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, Md.).

Construction of an SLP1 library in pXE4.

pCAO106 (pACYC177 [10] containing SLP1 as a BamHI insert) was digested by BamHI. The SLP1 fragment was isolated from the gel, purified by using a gel extraction kit (QIAquick; Qiagen), and partially digested by the enzyme Sau3AI. The Sau3AI fragments generated were then cloned into the pXE4 BamHI site as described elsewhere (31).

Catechol dioxygenase activity assays.

Catechol dioxygenase (XylE) activity assays were performed as described in reference 18. Briefly, qualitative assays were performed by spraying 0.1 M catechol onto plates containing 2- to 3-day-old colonies. Appearance of yellow colonies was determined visually no more than 1 h after spreading of the catechol in the initial screen and then 10 min after addition of catechol for studies of Popimp (promoter opposite imp).

Enzymatic extracts were prepared in triplicate. Spores from glycerol stock were patched on MY plates containing thiostrepton (50 μg/ml) or/and hygromycin (200 μg/ml). Spores were collected from plates, and one-fourth of the contents of each plate was suspended in 300 μl of 0.3 M sucrose; 100-μl aliquots were patched, in triplicate, onto MY medium plates supplemented with thiostrepton (50 μg/ml) or/and hygromycin (200 μg/ml) and containing cellophane membranes. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h. The mycelium was scraped into Eppendorf tubes; 1 ml of 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) was added, and cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, sonicated, and assayed as described in reference 18. TK64 or TK64 harboring pXE4 was used as a negative control; TK64 containing pSUM80, which expresses xylE from the strong promoter of the Tn5 aph gene (7), was used as a positive control. Strains Stm188 (expressing impA and impC), Stm189 (expressing impC), and Stm190 (expressing impA) harboring pSJH6 or pXE4 were assayed.

Tn5 mutagenesis.

pSUM50 was used to transform strain E. coli MB117, containing the Tn5 transposon (Table 1), in 23 independent tubes. Ampicillin-resistant and Kanr transformants were selected, and plasmid DNA was extracted from these transformants. The Tn5 insertions were then mapped by restriction analysis.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

To sequence the 1.85-kb SalI (8.70)-HindIII (10.20) region, pSUM50 was digested by BamHI and HindIII, and the 2.9-kb fragment separated on gels by electrophoresis was isolated by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). This fragment was then digested by SalI and cloned into pUC18 digested by HindIII and SalI. To sequence the SLP1 HindIII (10.20)-BclI (14.80) region, pSUM50 was digested by HindIII, and the 6-kb fragment separated on gels by electrophoresis was isolated by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit. This fragment was then cloned into pUC18 linearized by HindIII and previously dephosphorylated by calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (31), to prevent its religation. Sequence was performed by oligonucleotide walking. pUC forward and reverse 23-base sequencing primers were used. The other primers used were obtained from Operon Technologies, Inc. (Alameda, Calif.). Sequencing was performed with an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer from Perkin-Elmer (Foster City, Calif.). Open reading frames (ORFs) were identified by using a modified version of the program FRAME (2), kindly provided by K. Kendall. The FRAME program is based on the biased codon usage that occurs in organisms having high G+C content. Sequence was analyzed by using BLAST (1), DNA Strider (26), and Pedro’s BioMolecular Research Tools (29a).

Primer extension analysis.

Total RNA, isolated from S. lividans TK64 harboring pXE4 or pSJH6 (pXE4 containing the Sau3AI SLP1 region having promoter activity) or from Stm188 (S. lividans expressing impA and impC) harboring pSJH6, was extracted as described by Hopwood et al. (16). RNA was hybridized with oligonucleotide pXE4−71 (5′-CGGCGGTTTCAAAGGCCAGACAGGCGGTAAG-3′) (see Fig. 2) labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. The products were extended as described elsewhere (27) and loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. A sequencing ladder was generated by sequencing pSJH6 or pXE4 with oligonucleotide pXE4−71.

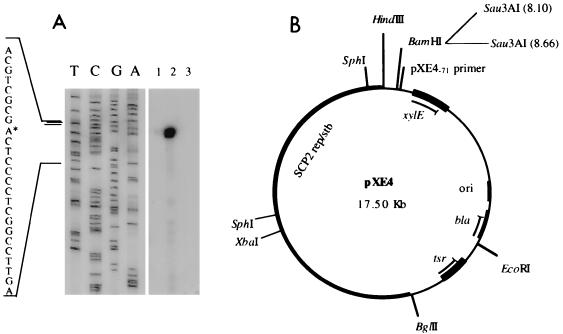

FIG. 2.

(A) Primer extension analysis of Popimp. RNA was prepared from S. lividans TK64 harboring pXE4 (lane 1) or pSJH6 (lane 2) or from S. lividans Stm188 expressing impA and impC and harboring pSJH6 (lane 3). The asterisk represents the transcriptional start site. (B) Map of the pXE4 derivative containing the Sau3AI (8.10 to 8.66) insert (pSJH6). The primer used for primer extension analysis, pXE4−71, is also shown. tsr, the thiostrepton resistance gene from Streptomyces spp.; bla, a β-lactamase gene from E. coli; ori, the ColE1 origin of replication; SCP2 rep/stb, the SCP2 replication and stabilization functions (16); xylE, a promoterless copy of the xylE gene (18).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the SLP1 transfer region has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. 538670.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of an SLP1 promoter controlled by imp.

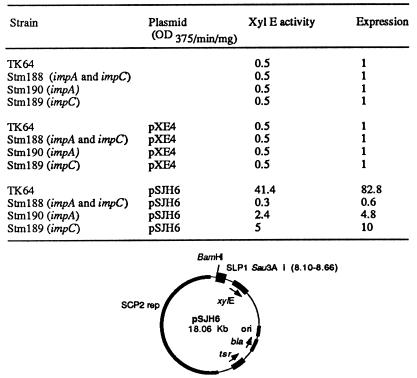

Autoregulation of imp expression is mediated through a promoter, Pimp, that initiates transcription of a polycistronic operon containing the impA and impC genes (34) (Fig. 1). To identify other SLP1 promoters regulated by imp, we fused SLP1 DNA fragments generated by partial digestion with Sau3AI to the pXE4 xylE gene (Fig. 2), which encodes catechol dehydrogenase and converts colorless catechol to an intensely yellow oxidation product (hydroxymuconic semialdehyde) (18). After transformation of S. lividans, six clones producing yellow colonies were identified; these were tested for repression of yellow coloration by impA (strain Stm190 [see Materials and Methods]), impC (strain Stm189), or a cassette containing both impA and impC (strain Stm188), all integrated into the S. lividans chromosome as a single copy. As shown in Fig. 3, one of the six promoters detected in the reporter gene assay was repressed by impA or impC alone to 6 to 12% of the expression observed in an imp-minus strain and was repressed 8 to 16 times more effectively by impA and impC acting together. The pXE4 construct carrying the DNA fragment specifying imp-repressed activity was designated pSJH6 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 1.

Map of SLP1 showing the region containing Popimp and those involved in transfer and pock formation. Popimp, Pimp, the SLP1 attachment site (attP), the integrase (int) and excisase (xis) genes, as well as the genes and ORFs involved in SLP1 intermycelial (tra) and intramycelial (spdB) transfer are shown. The direction of translation is indicated by filled arrows. The numbers indicate the positions (in kilobases) of the restriction sites in the sequence of the whole plasmid.

FIG. 3.

Control of Popimp by imp genes. Streptomyces strains TK64, Stm188 (expressing impA and impC), Stm189 (expressing impC), and Stm190 (expressing impA), harboring or not harboring plasmid pXE4 (containing the xylE gene) or pSJH6 (whose map is shown), as indicated, were grown on MY medium containing cellophane membranes and lysed by sonication, and expression of the xylE gene of the plasmids was measured in triplicate as indicated in Materials and Methods. The numbers for the XylE activity are the rate of change in optical density at 375 nm (OD375) per minute per milligram of protein and are averages from three independent assays. “Expression” refers to the level of expression of the xylE gene in the plasmid tested compared to that in pXE4, containing a promoterless xylE gene. tsr, the thiostrepton resistance gene from Streptomyces spp.; bla, a β-lactamase gene from E. coli; ori, the ColE1 origin of replication; SCP2 rep, the SCP2 replication and stabilization functions (16); xylE, a promoterless copy of the xylE gene (18).

The Sau3AI fragment inserted into pSJH6 was sequenced by using a primer located 71 bp upstream of the BamHI site of the xylE gene (primer pXE4−71) (Fig. 2). The sequence obtained identified the 560-bp fragment as one located 5′ to the impA gene and contained between positions 8.1 and 8.66 of SLP1 (Fig. 1) (15). A segment having characteristics of E. coli ς70 promoters and oriented in a direction opposite the orientation of the Pimp promoter (15) was identified approximately 300 bp from Pimp in this 560-bp fragment (Fig. 4). A start site for transcription divergent from the transcription initiated by Pimp was demonstrated at this site by primer extension using total RNA prepared from S. lividans harboring plasmid pSJH6 (Fig. 2A, lane 2) and oligonucleotide pXE4−71, which corresponds to the 5′ end of the xylE gene. The promoter initiating this transcript was designated Popimp. Parallel primer extension experiments that used as template the RNA prepared from S. lividans harboring pSJH6 and also expressing the imp genes gave no xylE gene RNA end (Fig. 2, lane 3), indicating control of a Popimp-initiated transcript by imp and confirming our finding by reporter gene assay that a promoter within the SLP1 DNA fragment containing Popimp is repressed by impA and impC.

FIG. 4.

Sequence and sequence analysis of the Sau3AI (8.10)-BclI (14.8) SLP1 region upstream of Popimp. (A) The sequence of the first 200 bp of the Sau3AI (8.10)-Sau3AI (8.66) region and of the 200 bp prior to the spdB1 gene (as determined previously [15]) are shown and are separated by dashed lines. Recognition sequences sites for the restriction enzymes shown are underlined, as are sequences which function as putative ribosome-binding sites (RBS). Translation of the different ORFs is shown above the nucleotide sequence. The arrows originating at G, 5′ of impA, and at T, 5′ of spdB1, indicate the Pimp and Popimp transcription start sites, respectively. Dashed arrows indicate inverted repeats. Direct repeats (DR) are underlined. The −35 and −10 hexamers are indicated by heavy lines above the sequence. (B) Complete sequence Sau3AI (8.10)-BclI (14.8). The ORFs are indicated by arrows. Putative transmembrane helices of the putative protein are indicated by TM. The restriction sites are shown. Numbers indicate nucleotide positions of the start and stop sites of the ORFs in the sequence.

The −10 region of this promoter has the sequence 5′-GTACGT-3′ and the −35 region has the sequence 5′-TTGCCT-3′ characteristic of Streptomyces promoters (37). Two sequences, DR1 (5′-GACC-CC--C-3′) and DR2 (5′-CCTGCTG-3′) (Fig. 4A), that previously were found 5′ to Pimp and shown to be part of ImpA-binding sequences (34), were also present 5′ to Popimp (Fig. 4A).

Characterization of the imp-regulated DNA region proximal to Popimp.

The sequence of the 1.5-kb DNA region immediately proximal to Popimp (SalI (8.70)-HindIII (10.2) was determined. Computer-assisted analysis using the FRAME program (2) identified two ORFs (Fig. 4 and Table 2) predicted to encode proteins of 261 and 335 amino acids (aa). The second of these ORFs showed 47% identity and 56% similarity to spdB2 gene of pJV1 (33) and consequently was designated spdB2. The ORF proximal to the promoter was given the initial designation of orf261 and later named spdB1 for reasons discussed below. Within orf261 is the Sau3AI site of fusion of SLP1 to the xylE gene of pXE4, indicating that production of catechol dehydrogenase from the reporter gene reflects expression of orf261. Additionally, the site of the orf261-xylE fusion indicates that the Popimp-initiated transcript found by primer extension experiments to be regulated by imp corresponds to the 5′ end of orf261. As the stop codon of orf261 overlaps the start codon of spdB2 (see the GenBank sequence), orf261 and spdB2 are likely to be translationally coupled. Translational coupling has also been proposed for the spdB1 and spdB2 loci of pJV1 and pSN22, which are in corresponding positions (19, 33). orf261 is preceded by a likely ribosome-binding site (AAGGA [27]). SpdB2 contains four putative transmembrane helices schematized in Fig. 4B.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of ORFs 3′ to Popimp

| Name | Coordinates in sequence (bp) | % G+C at indicated codon position

|

No. of aab | Functional characteristicsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||

| spdB1 | 483–1268 | 71 | 63 | 81 | 261 | A |

| spdB2 | 1265–2272 | 81 | 54 | 84 | 335 | A |

| orf294 | 2567–3451 | 78 | 57 | 80 | 294 | A |

| traA | 3471–4010 | 71 | 56 | 85 | 179 | B, C |

| traB | 4025–6073 | 71 | 57 | 89 | 682 | B, C |

| orf169 | 6205–6714 | 69 | 50 | 90 | 169 | B, C |

A, involved in pock size; B, essential for pock formation; C, essential for plasmid transfer.

aa, amino acids.

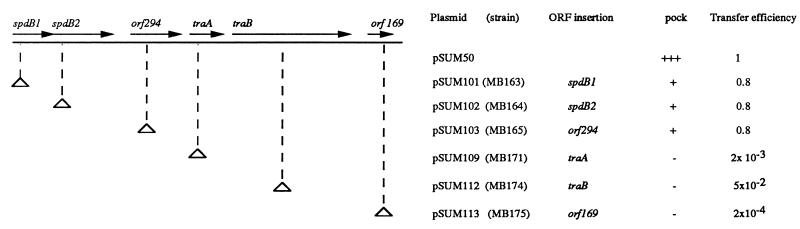

orf261 and spdB2 were both shown by Tn5 insertional mutagenesis to be implicated in plasmid transfer. In these experiments, Tn5 insertions were introduced into SLP1 as indicated in Materials and Methods, mapped by restriction analysis, and tested as described previously (35) for their effects on the pocking phenotype, which reflects the transient growth inhibition that occurs during transfer of Streptomyces plasmids, and also for direct effects on plasmid transfer frequency (as described in reference 20). As seen in Fig. 5, insertions in orf261 (pSUM101-carrying strain MB163) or spdB2 (pSUM102-carrying strain MB164) resulted in a major reduction in pock size, a phenotype commonly associated with defective intramycelial spreading of newly transferred plasmids (20). Based on these findings and on its positional relationship to spdB2, the orf261 locus was designated spdB1. Mutations in this Popimp-regulated gene as well as in spdB2 reduced the transfer frequency, slightly but repeatably, to 80% of normal (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Tn5 mutational analysis of the ORFs located in the Sau3AI (8.10)-BclI (14.8) SLP1 region upstream of Popimp. Arrows represent the orientation of ORFs. The small triangles and dashed lines represent locations of the Tn5 insertions. The pock sizes formed by plasmids are represented by +++, ++, +, and −, for normal, small, and tiny pocks and no pocks, respectively. Plasmid transfer efficiency was calculated as described in reference 20. The ORFs are indicated by arrows. Plasmids and the Streptomyces strains harboring them are shown.

Analysis of the SLP1 transfer region.

Transfer-related genes are commonly grouped together in Streptomyces plasmids (reviewed by Hopwood and Kieser [17] and in earlier reports [23, 29] cited in reference 16) have suggested that a large region extending clockwise in SLP1 from the site at which we have mapped Popimp is implicated in transfer of this plasmid. The sequence of this entire region, which was cloned as 6-kb HindIII (10.20)-HindIII (16.20) fragment, was determined and is schematized in Fig. 4A. The G+C content is 72 mol%, which is typical for Streptomyces DNA. All of the deduced ORFs (Fig. 1) are read in the same direction as transcription initiated from Popimp. Distal to spdB1 and spdB2 genes are four additional ORFs, which were found to affect plasmid transfer as determined by Tn5 insertion mutagenesis (Fig. 5). A 179-aa ORF distal to orf294 has features in common with the traA genes of Streptomyces plasmid pJV1 (33) (47% identity and 62% similarity) and resembles the traA gene of pSN22 (19); this SLP1 ORF has thus been designated traA. SLP1 traA also resembles a Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene encoding a protein of unknown function, designed Rv 0911 (31% identity and 40% similarity) (13). An SLP1 gene designated traB, encoding a putative protein of 682 aa, resembles traB of pJV1 (47% identity and 56% similarity), which is itself very similar to the traB gene of pSN22 (19). SLP1 TraB also presents similarities to the SpoIIIE protein of Bacillus subtilis (9, 38) (25% identity and 45% similarity). traB of SLP1 has a P-loop ATP/GTP-binding motif in approximately the same position as in pSN22 and pJV1 traB. traA and traB are preceded by likely ribosome-binding sites (37) (AGGAG and AAGG) located 11 nucleotides from their putative translational initiation codons (see the complete sequence in GenBank). Tn5 insertions in either of these genes abolished pocking and reduced the transfer frequency, identifying these loci as transfer genes (Fig. 5).

Expression of imp in recipients prevents SLP1-mediated gene transfer.

To examine directly the role of imp in chromosomal and plasmid gene transfer mediated by SLP1, S. lividans TK23 harboring the integrated SLP1 derivative pCAO153 was mated with S. lividans TK64 expressing impA and impC (strain Stm188), impA alone (Stm190), or impC alone (Stm189). Transfer of plasmid and chromosomal genes was monitored by measuring transfer efficiency and chromosome-mobilizing ability as described in reference 30. As shown in Table 3, the low background frequency of chromosomal recombinants observed for TK23 (approximately 10−7; mating pair 1) was raised 2 orders of magnitude (mating pair 3) when the conjugation-proficient SLP1 derivative pCAO153 was present in donor cells, as was shown previously (29). Expression of either impA or impC in the recipient decreased the frequency of pCAO153-mediated recombinants by approximately 50% (mating pairs 5 and 6). However, when both impA and impC were expressed in the recipient, the ability of pCAO153 to promote chromosomal transfer was totally reversed (mating pair 7). As shown in Table 4, expression of either impA or impC in the recipient also decreased the frequency of transfer of the pCAO153 plasmid by more than 2 orders of magnitude (mating pairs 3 and 4). When both impA and impC were expressed in the recipient, the efficiency of transfer was reduced by more than 3 orders of magnitude (mating pair 5). These results, which indicate that expression of imp products in the recipient prevents SLP1-mediated transfer of both chromosomal and plasmid genes, confirm the role of Imp in such transfer.

TABLE 3.

Effects of the expression of imp in recipients on SLP1-mediated chromosomal gene transfer

| Mating paira

|

No./ml

|

Efficiency of recombinationb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental genotypes

|

Pro+ Str recombinants | |||||

| No. | Spc | Pro Str | Spc | Str | ||

| 1 | TK23 | TK64 | 2.5 × 108 | 2.4 × 107 | 1.09 × 102 | 4 × 10−7 |

| 2 | TK23(pIJ303c) | TK64 | 3.8 × 107 | 2.4 × 107 | 1.98 × 105 | 3.2 × 10−3 |

| 3 | TK23(pCAO153) | TK64 | 4 × 108 | 2.4 × 107 | 5.0 × 103 | 1.2 × 10−5 |

| 4 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm160d | 7.1 × 108 | 2.5 × 107 | 8.0 × 103 | 1.1 × 10−5 |

| 5 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm190e | 6.1 × 107 | 3.2 × 107 | 4.8 × 102 | 5.2 × 10−6 |

| 6 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm189f | 7.0 × 108 | 4.0 × 108 | 6.6 × 103 | 6 × 10−6 |

| 7 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm188g | 5.0 × 108 | 2.5 × 108 | 3.15 × 102 | 4.2 × 10−7 |

Approximately equivalent numbers of spores of each parental type were mixed and plated on MY medium. Following one cycle of nonselective growth, spores were collected and quantified for parental types by plating dilution on MY containing spectinomycin (Spc) or streptomycin (Str) and for the recombinants by plating on MM containing Str. Numbers are averages obtained from two independent matings and differed by less than twofold.

Ratio of Pro+, Strr recombinants to the sum of the parental types of a given mating. The frequency of reversion, defined as the ratio of TK64 colonies per milliliter on MM medium containing Str (Pro+ Str) to the number of TK64 colonies per milliliter on MY medium containing Str was 4.2 × 10−8.

Conjugative Tsrr derivative of pIJ101 known to promote chromosomal gene transfer and was used as a positive control (24, 30).

TK64 containing pSUM317 integrated into the chromosomal attB site and used to control whether pCAO153 could integrate into the chromosome of a recipient strain already containing a plasmid integrated into the attB site.

S. lividans TK64 strain expressing impA.

S. lividans TK64 strain expressing impC.

S. lividans TK64 strain expressing impA and impC.

TABLE 4.

Effects of the expression of imp in recipients on SLP1 plasmid transfer

| Mating paira

|

No./ml

|

Efficiency of transferb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental genotypes

|

Str Tsr transconjugants | |||||

| No. | Spc Tsr | Pro Str | Spc Tsr | Str | ||

| 1 | TK23(pCAO153) | TK64 | 1.8 × 105 | 2.4 × 107 | 1.5 × 105 | 8.5 × 10−1 |

| 2 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm160c | 1.8 × 105 | 2.5 × 107 | 1.45 × 105 | 8.0 × 10−1 |

| 3 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm190 (impA) | 1.8 × 105 | 3.2 × 107 | 3.6 × 102 | 2.0 × 10−3 |

| 4 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm189 (impC) | 1.8 × 105 | 4.0 × 108 | 7.2 × 102 | 4.0 × 10−3 |

| 5 | TK23(pCAO153) | Stm188 (impA+ impC) | 1.8 × 105 | 2.5 × 108 | 3.6 × 101 | 2.0 × 10−4 |

Donors and excess recipient spores were mixed and plated on MY medium. Following one cycle of nonselective growth, spores were collected and quantified for donor by plating dilution on MY containing spectinomycin (Spc) and thiostrepton (Tsr), for recipient by plating dilution on MY containing Str, and for the transconjugant by plating on MM containing Str and Tsr. Numbers are the averages obtained from two independent matings and differed by less than twofold. TK64 strains were as described in the legend of Table 3, footnotes d to g.

Calculated as described in reference 30 as the ratio of Strr Tsrr transconjugants to the number of donors for a given mating.

DISCUSSION

The results reported here indicate that the imp operon controls transfer functions as well as maintenance functions of the SLP1 plasmid. We identified and characterized a promoter, Popimp, which is repressed by imp and was found to transcribe genes required for intramycelial spreading of SLP1. Two additional groups of genes distal to Popimp were found by sequence analysis to resemble transfer genes of other Streptomyces plasmids and shown by Tn5 insertion mutagenesis to encode functions necessary for SLP1-mediated transfer. Furthermore, SLP1-mediated gene transfer was shown to be repressed by imp.

The spdB2, traA, and traB genes of SLP1 resemble similarly designated genes of Streptomyces plasmid pJV1 and Streptomyces plasmid pSN22: The TraB protein of pSN22 contains a functional nucleoside triphosphate-binding motif and is localized in the cytoplasmic membrane (25). A structural motif that has features in common with the tra gene product of Streptomyces plasmid pIJ101 (22) and the spoIIIE gene product of B. subtilis (38), which is responsible for chromosome translocation during prespore formation of B. subtilis, was identified within traB of SLP1. The pIJ101 tra gene and the traB genes of pJV1 and pSN22 specify functions lethal to the plasmid or host (19, 22, 33), and SLP1 traB may function similarly. Although the spdB1 (orf261) gene of SLP1 shows no significant structural homology to spdB1 of pJV1 or pSN22, all three genes affect pock size. Furthermore, in spdB1 and spdB2 in all three plasmids, the stop codon of the first ORF overlaps the start codon of the second. orf294 is also a gene involved in spreading. Regulation of the SLP1 transfer region presents similarity with the regulation of transfer genes of pJV1 and pSN22: the SLP1 impA function is similar to that of traR of pJV1 and pSN22, since these genes are all autoregulated and function as repressors of transfer genes. Despite the above similarities between the transfer loci of plasmids SLP1, pJV1, and pSN22, their structural organizations are not identical (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Comparison of organizations of the transfer regions of SLP1 and other Streptomyces plasmids. Positions and orientation of ORFs and genes are shown for SLP1, pJV1 (33), and pSN22 (19). Arrows represent the orientation of fragments or the direction of transcription. The number of amino acids in the ORFs is indicated in parentheses below the name of each ORF.

The transfer genes of SLP1 resembles those of conjugative Streptomyces plasmids pJV1 and pSN22, suggesting that these plasmids may be derived from a common ancestor, but are different from the transfer genes of pSAM2, which like SLP1 is an integrating plasmid. Thus, SLP1 can be viewed as a genetic element composed of discrete modules: a transfer segment similar to that present in Streptomyces nonintegrating conjugative plasmids of the pJV1 and pSN22 family, and an integration/excision module containing recombinase genes similar to those of temperate bacteriophages (7, 8) and other Streptomyces integrating elements (e.g., pSAM2).

Our results indicate that the expression of imp genes in recipients sharply reduces the frequency of events associated with SLP1-mediated transfer of both plasmid and chromosomal genes. As imp has been found in our experiments to repress genes associated with transfer, this finding is most simply interpreted as being at least in part the result of such repression. However, as transfer frequency is measured by stable persistence of transferred genes in the recipient, which requires integration of transferred genes into the recipient’s chromosome, events that affect chromosomal integration of genes in the recipient also have the potential to influence determinations of frequency. Because SLP1-mediated transfer of chromosomal genes, as well as of plasmid genes, is affected by expression of imp in the recipient, any affect of imp on gene integration in the recipient would necessarily have to involve both general recombination mechanisms and site-specific plasmid integration mediated by the SLP1-encoded int recombinase (7, 8).

Based on our results, we propose the following model. When SLP1 is integrated into the chromosome, the expression of imp genes represses both plasmid DNA replication (15) and expression of transfer genes, preventing SLP1-mediated transfer of chromosomal genes as well as the integrated plasmid. We suggest that donors and recipients meet independently of the expression of plasmid transfer genes and that the interaction between donor and recipient cells has a key role in activating SLP1 transfer genes in donors. According to this model, contact between donor and recipient must necessarily precede the expression of plasmid imp-regulated loci that mediate high-frequency gene transfer, instead of being the result of expression of those genes.

Potentially, such cell-cell contact or fusion between donor and recipient could dilute Imp proteins, causing derepression of the tra and spd genes controlled by imp, and consequently promoting gene transfer. Alternatively, information acquired from the recipient may alter imp expression or activity by other signal transduction mechanisms. In any case, our results imply that the initial stage of mating in Streptomyces (i.e., cell-cell contact or fusion) is not actively induced by the plasmid genes that facilitate gene transfer events. As chromosomal gene transfer can occur at low frequency during imp-mediated repression of plasmid-borne tra and spd genes, simple cell contact or fusion is sufficient for such transfer. Indeed, chromosomal gene transfer can occur at low frequency even in the absence of plasmids (reference 30 and Table 3). Our results further suggest that derepression of imp-regulated plasmid genes following interaction between donor and recipient is responsible for the efficient transfer of plasmid and chromosomal genes during mating between Streptomyces cells that contain plasmids. This two-stage model for gene transfer in Streptomyces potentially explains the distinctly different frequencies observed for plasmid-mediated (enhanced) gene transfer versus the chromosome gene transfer (i.e., chromosome-mobilizing activity) occurring in the absence of plasmids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by NIH grant AI08619 to S.N.C. J.H. gratefully acknowledges the support of postdoctoral fellowships from the French Ministry of Foreign Office and from EMBO.

We thank members of the Cohen laboratory, particularly Gregg Pettis, Arthur Brace, and Carina Gaggero, for helpful discussions and advice. We thank Kevin Kendall for the kind gift of his modified version of the FRAME program. We thank Fabien Petel for assistance in data analysis and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibb M J, Findlay P R, Johnson M W. The relationship between base composition and codon usage in bacterial genes and its use for the simple and reliable identification of protein-coding sequences. Gene. 1984;30:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibb M J, Freeman R F, Hopwood D A. Physical and genetical characterization of a second sex factor, SCP2, for Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Gen Genet. 1977;154:155–166. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibb M J, Ward J M, Kieser T, Cohen S N, Hopwood D A. Excision of chromosomal DNA sequences from Streptomyces coelicolor forms a novel family of plasmids detectable in Streptomyces lividans. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:230–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00272910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolivar F, Rodriguez R L, Greene P J, Betlach M C, Heyeneker H L, Boyer H W, Crosa J H, Falkow S. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles. II. A multiple cloning system. Gene. 1977;2:95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasch, M., J. M. Hagege, and S. N. Cohen. Unpublished data.

- 7.Brasch M A, Cohen S N. Excisive recombination of the SLP1 element in Streptomyces lividans is mediated by Int and enhanced by Xis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3075–3082. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3075-3082.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasch M A, Pettis G S, Lee S C, Cohen S N. Localization and nucleotide sequences of genes mediating site-specific recombination of the SLP1 element in Streptomyces lividans. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3067–3074. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3067-3074.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler P D, Mandelstam J. Nucleotide sequence of the sporulation operon, spoIIIE, of B. subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:2359–2370. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-9-2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang A, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chater K F. Genetics of differentiation in Streptomyces. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:685–713. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chater K F. In: Sporulation in Streptomyces. Smith I, Slepecky R A, Setlow P, editors. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 277–299. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver S, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton S, Squares S, Sqares R, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita Y, Fujita T, Miwa Y, Nihashi J-I, Aratani Y. Organization and transcription of the gluconate operon, gnt, of Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13744–13753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant S R, Lee S C, Kendall K, Cohen S N. Identification and characterization of a locus inhibiting extrachromosomal maintenance of the Streptomyces plasmid SLP1. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:324–331. doi: 10.1007/BF02464900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C M, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces, a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopwood D A, Kieser T. Conjugative plasmids of Streptomyces. In: Clewell D B, editor. Bacterial conjugation. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingram C, Brawner M, Youngman P, Westpheling J. xylE functions as an efficient reporter gene in Streptomyces spp.: use for the study of galP1, a catabolite-controlled promoter. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6617–6624. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6617-6624.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kataoka M, Kiyose Y M, Michisuji Y, Horiguchi T, Seki T, Yoshida T. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Streptomyces nigrifaciens plasmid, pSN22: genetic organization and correlation with genetic properties. Plasmid. 1994;32:55–69. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kataoka M, Seki T, Yoshida T. Five genes involved in self-transmission of pSN22, a Streptomyces plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4220–4228. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4220-4228.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kataoka M, Seki T, Yoshida T. Regulation and function of the Streptomyces plasmid pSN22 genes involved in pock formation and inviability. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7975–7981. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7975-7981.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendall K J, Cohen S N. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Streptomyces lividans plasmid pIJ101 and correlation of the sequence with genetic properties. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4634–4651. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4634-4651.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kieser, T. Unpublished data.

- 24.Kieser T, Hopwood D A, Wright H M, Thompson C J. pIJ101, a multi-copy broad host-range Streptomyces plasmid: functional analysis and development of DNA cloning vectors. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;185:223–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00330791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosono S, Kataoka M, Seki T, Yoshida T. The TraB protein, which mediates the intermycelial transfer of the Streptomyces plasmid pSN22, has functional NTP-binding motifs and is localized to the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:397–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.379909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marck C. DNA Strider, a C program for DNA and protein sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:583–590. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.1.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDowall K J, Lin-Chao S, Cohen S N. A+U content rather than a particular nucleotide order determines the specificity of RNase E cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10790–10796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omer C A, Cohen S N. In: SLP1: a paradigm for plasmids that site-specifically integrate in the actinomycetes. Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Washington, D.C: Mobile DNA American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omer C A, Stein D, Cohen S N. Site-specific insertion of biologically functional adventitious genes into the Streptomyces lividans chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2174–2184. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2174-2184.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Pedro’s BioMolecular Research Tools. revision date. [Online.] 15 June 1996. http://www.public.iastate.edu/∼pedro/research_tools.html http://www.public.iastate.edu/∼pedro/research_tools.html. . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettis G S, Cohen S N. Transfer of the pIJ101 plasmid in Streptomyces lividans requires a cis-acting function dispensable for chromosomal gene transfer. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:955–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00487.x. . (Erratum, 16:170, 1995.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: CSHL Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Servin G L. Relationship between the replication functions of Streptomyces plasmids pJV1 and pIJ101. Plasmid. 1993;30:131–140. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Servin G L, Sampieri A I, Cabello J, Galvan L, Juarez V, Castro C. Sequence and functional analysis of the Streptomyces phaeochromogenes plasmid pJV1 reveals a modular organization of Streptomyces plasmids that replicate by rolling circle. Microbiology. 1995;141:2499–2510. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-10-2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiffman D, Cohen S N. Role of the imp operon of the Streptomyces coelicolor genetic element SLP1: two imp-encoded proteins interact to autoregulate imp expression and control plasmid maintenance. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6767–6774. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6767-6774.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smokvina T, Boccard F, Pernodet J-L, Friedmann A, Guérineau M. Functional analysis of the Streptomyces ambofaciens element pSAM2. Plasmid. 1991;25:40–52. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(91)90005-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein D S, Cohen S N. Mutational and functional analysis of the korA and korB gene products of Streptomyces plasmid pIJ101. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:337–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00633838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strohl W R. Compilation and analysis of DNA sequences associated with apparent streptomycete promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:961–974. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.5.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu L J, Lewis P J, Allmansberger R, Hauser P M, Errington J. A conjugation-like mechanism for prespore chromosome partitioning during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1316–1326. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.11.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13pm18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zotchev S B, Schrempf H. The linear Streptomyces plasmid pBL1: analyses of transfer functions. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:374–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00281786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]