Key Points

Question

Is use of maternal labor epidural analgesia (LEA) and oxytocin for labor and delivery associated with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in children?

Findings

In this cohort study including 205 994 singleton births with vaginal deliveries, use of LEA was associated with ASD risk, but oxytocin use was not associated, after adjusting for each other. ASD risk was not associated with use of oxytocin alone, but an increased risk was noted if both LEA and oxytocin were administered.

Meaning

The results of this study suggest that more in-depth studies are needed to assess LEA during labor and delivery and long-term safety of children.

Abstract

Importance

Maternal labor epidural analgesia (LEA) and oxytocin use for labor and delivery have been reported to be associated with child autism spectrum disorders (ASD). However, it remains unclear whether these 2 common medications used during labor and delivery have synergistic associations with ASD risk in children.

Objective

To assess the independent associations of LEA and oxytocin during labor and delivery with ASD, as well as outcome modification associated with the concurrent use of both interventions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data for this cohort study included 205 994 singleton births with vaginal deliveries in a single integrated health care system in Southern California from calendar years 2008 to 2017. Children were followed up to December 31, 2021. Data on use of LEA and oxytocin, covariates, and ASD outcome in children were obtained from electronic medical records. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) adjusting for covariates.

Exposures

Labor epidural analgesia and/or oxytocin use during labor and delivery.

Main Outcomes and Measures

A child’s clinical diagnosis of ASD during follow-up and at age of diagnosis.

Results

Among the cohort, 153 880 children (74.7%) were exposed to maternal LEA and 117 808 children (57.2%) were exposed to oxytocin during labor and delivery. The population of children was approximately half boys and half girls. The median (IQR) age of the mothers was 30.8 (26.8-34.5) years for those not exposed to LEA, 30.0 (25.9-33.8) years for those exposed to LEA, 30.4 (26.5-34.1) years for those unexposed to oxytocin, and 30.0 (25.9-33.9) years for those exposed to oxytocin during labor and delivery. A total of 5146 children (2.5%) had ASD diagnosed during follow-up. Oxytocin exposure was higher among LEA-exposed (67.7%) than -unexposed (26.1%) children. The ASD risk associated with LEA was independent of oxytocin exposure (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.18-1.38); however, the ASD risk associated with oxytocin was not significant after adjusting for LEA exposure (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99-1.12). A significant interaction of LEA and oxytocin on child ASD risk was found (P = .02 for interaction). Compared with no exposure, HRs were 1.20 (95% CI, 1.09-1.32) for LEA alone, 1.30 (95% CI, 1.20-1.42) for both LEA and oxytocin, and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.78-1.04) for oxytocin alone.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study suggest an association between maternal LEA and ASD risk in children, and the risk appeared to be further increased if oxytocin was also administered. Oxytocin exposure without LEA exposure was not associated with ASD risk in children. These findings must be interpreted with caution. Further studies are needed to replicate or refute the study results and examine biological plausibility.

This cohort study examines the risk for autism spectrum disorders in children whose mothers received labor epidural analgesia and/or oxytocin during labor and delivery.

Introduction

Labor epidural analgesia (LEA) is one of the most effective and commonly used methods in clinical practice for pain control during labor and delivery. Widespread use of LEA is supported by randomized clinical trials for maternal pain relief and no increased risk of perinatal outcomes compared with other drugs.1,2,3,4 However, little is known about its long-term safety, especially in offspring. Given the routine use of LEA worldwide, it is important to assess potential continuing health outcomes. To our knowledge, the first large, population-based study assessing LEA for vaginal delivery with risk of offspring autism spectrum disorders (ASD) using comprehensive electronic medical records (EMRs) from a retrospective birth cohort within an integrated health care system was published recently.5 The investigators reported that maternal LEA for vaginal delivery was associated with a 37% increased risk of ASD in children after adjusting for some potential confounders. These findings raised concerns regarding the long-term safety of LEA and called for further research in this area, although ASD is rare and its risk factors remain elusive and multifactorial.

Several large population-based studies have since been published showing inconsistent results. In Manitoba, Canada,6 and Denmark,7 studies reported no associations. Studies from British Columbia, Canada,8 and the US9 noted minimal yet significant risk of approximately 9% to 10%. A recent large-sample study from Ontario, Canada, reported a significantly increased risk of 14%, which remained with various robust sensitivity analyses.10

Large discrepancies exist in the rates of LEA exposures and ASD and in confounder adjustment among these studies. Use of LEA and screening and diagnosis of ASD differ by country, population, and health care professional practice and guidelines. Furthermore, labor and delivery is a very complicated process and many other drugs can be given before or at the same time as LEA,11 which makes separating risk due to LEA exposure challenging.

Among these multiple exposures, oxytocin use is common. Labor epidural analgesia can interfere with uterine contractility, prolonging labor and decreasing the rate of spontaneous births.12,13 Previous studies have shown that oxytocin use for labor induction and augmentation may be associated with risk of ASD in children.14,15 A recent meta-analysis concluded that oxytocin use for labor and delivery may be associated with other neurodevelopmental outcomes in children as well.16 Given high rates of concurrent use of oxytocin and LEA,17 investigations of LEA exposure and ASD risk in offspring can be confounded or modified by oxytocin exposure.

The goal of this study was to delineate LEA and oxytocin exposure for vaginal delivery and assess their independent and potential associations with ASD risk in offspring. This study also addresses limitations of the first study on LEA5 by including multiple additional perinatal covariates included in other studies.6,7,8,9,10

Methods

Study Population

This study included singletons born at 28 to 44 weeks by vaginal delivery in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) hospitals between calendar years 2008 and 2017. Children were followed up until December 31, 2021. Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large, integrated health care system with well-established and comprehensive EMRs. It covers more than 4.5 million members across Southern California, with its membership diverse and similar in socioeconomic characteristics to the region’s census demographic factors.18 The KPSC guidelines for pediatric care require screening for developmental delays, including ASD for children at age 18 to 24 months at standard well-child visits. Maternal demographic characteristics, pregnancy history, and health conditions, perinatal outcomes, and child ASD diagnosis were extracted from KPSC EMRs as described in previous studies.5,19 This study was approved by the KPSC Institutional Review Board, and the need for individual participant consent was waived. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Follow-up of children started at age 1 year and ended at the earliest age of any of the following: (1) clinical diagnosis of ASD, (2) last date of continuous KPSC membership, (3) death of the child regardless of cause of death, or (4) study end date of December 31, 2021. A total of 205 994 children born from 160 437 unique mothers met inclusion criteria and were included in data analysis.

Exposures and Outcomes

Primary exposure variables were LEA and oxytocin administered during intrapartum hospital admission up to the time of delivery, extracted, and validated using anesthesia procedure notes, perinatal care flowcharts, and pharmacy databases within the KPSC EMR system. The outcome was whether a child had an ASD diagnosis during follow-up and age at the initial diagnosis. The ASD diagnoses were identified by International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, codes 299.0, 299.1, 299.8, and 299.9, or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, codes F84.0, F84.3, F84.5, F84.8, and F84.9. Diagnostic codes included autistic disorders, Asperger syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified but excluded Rett syndrome or childhood disintegrative disorder. Diagnosis of ASD was determined if codes were present in EMRs at 2 or more separate health visits as defined previously.19,20,21

Covariates

Covariates selected to adjust for potential confounding included birth year, maternal age at delivery, self-reported race and ethnicity, educational level, household income, parity, history of comorbidity (heart, lung, kidney, or liver disease, or cancer), prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, diabetes, preeclampsia and/or eclampsia, smoking during pregnancy, and the child’s sex, birth weight, preterm birth status, and medical center of delivery, which were potential confounders from earlier studies.5,19 Data on race and ethnicity were included because other studies have focused on disparities.22,23 We included additional covariates reported in recent studies6,7,8,9,10,24: marital status, pregnancy maternal mental health issues, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, hypothyroidism, infection, seizures, alcohol use, drug use during pregnancy, antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, induction of labor, augmentation, labor dystocia, and fetal distress. All data were extracted from KPSC EMRs.

Statistical Analysis

Cohort characteristics are presented as median (IQR) for continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables. The risk of ASD associated with exposures to LEA and oxytocin was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for the covariates mentioned in the previous section. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining the log(–log) plot of the survival function vs log of the child’s age and showed a parallel relationship, and thus was not violated. Robust SEs were used to correct for potential correlation within siblings born to the same mothers. Three models were performed regarding covariate adjustment. Model A adjusted for birth year only, with nonlinear birth year outcome with ASD modeled through spline function with 4 df in Cox proportional hazards regression models. Model B adjusted for birth year and antenatal factors, including maternal age at delivery, race and ethnicity, educational level, household income, marital status, parity, history of comorbidity, prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, diabetes, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, hypothyroidism, infection, seizures, mental health issues, smoking, alcohol and drug use during pregnancy, antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, birth weight, preterm status, child sex, and medical center. Model C further adjusted for fetal distress, labor dystocia, and any birth defects in addition to covariates in model B to assess whether any associations with LEA or oxytocin exposure could be explained by these perinatal measures that could also be influenced by LEA or oxytocin exposures. For each model, LEA and oxytocin exposure were first modeled individually; models were then mutually adjusted for both LEA and oxytocin use to assess the independent outcome associated with each exposure on ASD risk in offspring. To check the validity of our covariate-adjusted analysis, we also performed data analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting to balance covariate distribution between exposed and unexposed groups for covariates in model B, with stabilized weights to avoid extreme weights. The propensity score associated with being in the exposed group (LEA exposure or oxytocin) given the covariates was estimated using logistic regression, and then inverse probability of treatment weighting analysis was weighed by propensity score.

To assess potential synergistic associations between LEA and oxytocin exposure, an interaction term between LEA and oxytocin was included in the main outcomes model of LEA and oxytocin to test for a significant interaction. If a significant interaction was present, further exposure-stratified analysis was conducted to reveal the statistical nature of the interaction; exposure stratification generated 1 variable with 4 levels: (1) unexposed, (2) exposed to oxytocin only, (3) exposed to LEA only, and (4) exposed to both LEA and oxytocin.

As sensitivity analyses, we repeated data analysis excluding preterm (gestational age at delivery <37 weeks) and postterm (gestational age at delivery >42 weeks) births and deliveries with forceps or vacuum. We also performed sensitivity analysis by only including families with more than 2 children. Relative risks associated with exposures are presented as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI. Data are also plotted for covariate-adjusted cumulative incidence of ASD stratified by LEA and oxytocin exposures.25 SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc), and R, version 3.6.0 (64-bit; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) were used for data analysis. All P values were determined from 2-sided tests, and P < .05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Among the 205 994 children, 153 880 (74.7%) were exposed to LEA and 117 808 (57.2%) were exposed to oxytocin during labor and delivery. The median (IQR) age of the mothers was 30.8 (26.8-34.5) years for those not exposed to LEA, 30.0 (25.9-33.8) years for those exposed to LEA, 30.4 (26.5-34.1) years for those unexposed to oxytocin, and 30.0 (25.9-33.9) years for those exposed to oxytocin during labor and delivery. A total of 132 560 women (64.3%) had induction and/or augmentation, and oxytocin was used by 88.9% of these patients. Oxytocin exposure was higher among LEA-exposed (67.7%) than LEA-unexposed (26.1%) women. Sociodemographic characteristics and medical history during pregnancy and labor and delivery for mothers and children were significantly different between mothers exposed to LEA and those unexposed (Table 1). Significant differences in social and health characteristics were also reported between mothers exposed to oxytocin and those unexposed (Table 1). These differences were particularly salient for labor and delivery outcomes; women exposed to LEA, as well as those exposed to oxytocin, had higher proportions of induction, augmentation, labor dystocia, antepartum hemorrhage, fever during labor, and fetal distress than women exposed to neither.

Table 1. Cohort Characteristics by LEA and Oxytocin Exposure.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No LEA (n = 52 114) | LEA (n = 153 880) | No oxytocin (n = 88 186) | Oxytocin (n = 117 808) | |

| Maternal | ||||

| Age at delivery, median (IQR), y | 30.8 (26.8-34.5) | 30.0 (25.9-33.8) | 30.4 (26.5-34.1) | 30.0 (25.9-33.9) |

| Race and ethnicitya | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 6396 (12.3) | 21 532 (14.0) | 12 498 (14.2) | 15 430 (13.1) |

| Black | 3626 (6.9) | 11 099 (7.2) | 5945 (6.7) | 8780 (7.5) |

| Hispanic | 29 521 (56.6) | 76 961 (50.0) | 45 217 (51.3) | 61 265 (52.0) |

| White | 11 327 (21.7) | 40 061 (26.0) | 22 152 (25.1) | 29 236 (24.8) |

| Other | 1244 (2.4) | 4227 (2.7) | 2374 (2.7) | 3097 (2.6) |

| Educational level | ||||

| ≤High school | 17 414 (33.4) | 44 386 (28.8) | 26 590 (30.2) | 35 210 (29.9) |

| College and postgraduate | 18 669 (35.8) | 58 889 (38.3) | 34 235 (38.8) | 43 323 (36.8) |

| Some college | 15 260 (29.3) | 48 457 (31.5) | 26 028 (29.5) | 37 689 (32.0) |

| Unknown | 771 (1.5) | 2148 (1.4) | 1333 (1.5) | 1586 (1.3) |

| Household income, $ | ||||

| 0-29 999.99 | 766 (1.5) | 1708 (1.1) | 1116 (1.3) | 1358 (1.2) |

| 30 000-49 999.99 | 11 416 (21.9) | 27 200 (17.7) | 16 655 (18.9) | 21 961 (18.6) |

| 50 000-69 999.99 | 16 724 (32.1) | 46 565 (30.3) | 26 752 (30.3) | 36 537 (31.0) |

| 70 000-89 999.99 | 12 061 (23.1) | 38 347 (24.9) | 21 311 (24.2) | 29 097 (24.7) |

| ≥90 000 | 11 147 (21.4) | 40 060 (26.0) | 22 352 (25.3) | 28 855 (24.5) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or have partner | 28 739 (55.1) | 80 925 (52.6) | 46 417 (52.6) | 63 247 (53.7) |

| Not married | 8475 (16.3) | 27 550 (17.9) | 13 971 (15.8) | 22 054 (18.7) |

| Unknown | 14 900 (28.6) | 45 405 (29.5) | 27 798 (31.5) | 32 507 (27.6) |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 11 431 (21.9) | 53 285 (34.6) | 20 830 (23.6) | 43 886 (37.3) |

| 1 | 18 736 (36.0) | 48 088 (31.3) | 34 420 (39.0) | 32 404 (27.5) |

| ≥2 | 17 835 (34.2) | 31 301 (20.3) | 24 549 (27.8) | 24 587 (20.9) |

| Unknown | 4112 (7.9) | 21 206 (13.8) | 8387 (9.5) | 16 931 (14.4) |

| Prepregnancy BMI, median (IQR) | 25.1 (22.1-29.2) | 25.2 (22.2-29.6) | 24.6 (21.8-28.6) | 25.7 (22.5-30.2) |

| History of comorbidity | 7877 (15.1) | 27 582 (17.9) | 14 198 (16.1) | 21 261 (18.0) |

| Diabetes during pregnancy | ||||

| No diabetes | 46 912 (90.0) | 137 909 (89.6) | 80 584 (91.4) | 104 237 (88.5) |

| Gestational diabetes | 4179 (8.0) | 11 829 (7.7) | 6044 (6.9) | 9964 (8.5) |

| Preexisting diabetes | 1023 (2.0) | 4142 (2.7) | 1558 (1.8) | 3607 (3.1) |

| Hypertension/preeclampsia | ||||

| No hypertension | 48 990 (94.0) | 138 791 (90.2) | 84 007 (95.3) | 103 774 (88.1) |

| Gestational hypertension | 1046 (2.0) | 5255 (3.4) | 1580 (1.8) | 4721 (4.0) |

| Chronic hypertension | 787 (1.5) | 3168 (2.1) | 1168 (1.3) | 2787 (2.4) |

| Preeclampsia | 1291 (2.5) | 6666 (4.3) | 1431 (1.6) | 6526 (5.5) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 241 (0.5) | 1171 (0.8) | 500 (0.6) | 912 (0.8) |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| No | 37 026 (71.0) | 101 801 (66.2) | 61 193 (69.4) | 77 634 (65.9) |

| Yes | 13 822 (26.5) | 48 171 (31.3) | 24 700 (28.0) | 37 293 (31.7) |

| Unknown | 1266 (2.4) | 3908 (2.5) | 2293 (2.6) | 2881 (2.4) |

| Drug use | ||||

| No | 38 320 (73.5) | 127 795 (83.0) | 68 924 (78.2) | 97 191 (82.5) |

| Yes | 68 (0.1) | 366 (0.2) | 158 (0.2) | 276 (0.2) |

| Unknown | 13 726 (26.3) | 25 719 (16.7) | 19 104 (21.7) | 20 341 (17.3) |

| Genitourinary infection during pregnancy | 13 059 (25.1) | 41 573 (27.0) | 22 061 (25.0) | 32 571 (27.6) |

| Seizures | 236 (0.5) | 803 (0.5) | 421 (0.5) | 618 (0.5) |

| Premature rupture of membrane | 3288 (6.3) | 12 154 (7.9) | 4311 (4.9) | 11 131 (9.4) |

| Hypothyroidism | 1553 (2.9) | 5039 (3.3) | 2718 (3.1) | 3874 (3.3) |

| Mental health issue | 4140 (7.9) | 17 059 (11.1) | 8254 (9.4) | 12 945 (11.0) |

| Induction | 8458 (16.2) | 52 463 (34.1) | 5341 (6.1) | 55 580 (47.2) |

| Augmentation | 16 790 (32.2) | 111 258 (72.3) | 10 240 (11.6) | 117 808 (100) |

| Labor dystocia | 740 (1.4) | 2531 (1.6) | 1113 (1.3) | 2158 (1.8) |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 4470 (8.6) | 14 687 (9.5) | 7639 (8.7) | 11 518 (9.8) |

| Fever during labor | 656 (1.3) | 18 430 (12.0) | 3939 (4.5) | 15 147 (12.9) |

| Gestational weight gain, median (IQR), kg | 11.8 (8.2-15.0) | 12.4 (8.9-15.9) | 11.9 (8.6-15.5) | 12.4 (8.7-16.1) |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Birth weight, median (IQR), g | 3330 (3030-3625) | 3355 (3060-3655) | 3336 (3050-3635) | 3357 (3050-3660) |

| Preterm | 3550 (6.8) | 8463 (5.5) | 5052 (5.7) | 6961 (5.9) |

| Birth defect | 4663 (8.9) | 15 120 (9.8) | 8336 (9.5) | 11 447 (9.7) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 25 984 (49.9) | 76 505 (49.7) | 43 826 (49.7) | 58 663 (49.8) |

| Male | 26 130 (50.1) | 77 375 (50.3) | 44 360 (50.3) | 59 145 (50.2) |

| Fetal distress | 7266 (13.9) | 37 477 (24.4) | 14 634 (16.6) | 30 109 (25.6) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); LEA, labor epidural analgesia.

Other race and ethnicity includes patients who self-identified as other or multiple races.

The population of children was approximately half boys and half girls. Among the cohort, 2.5% (n = 5146) of the children had an ASD diagnosis during follow-up: 2.7% (n = 4167) in the LEA group and 1.9% (n = 979) in the non-LEA group. In analyses assessing a single exposure to LEA or oxytocin adjusted for birth year, the HRs of ASD were 1.41 (95% CI, 1.31-1.51) for LEA-exposed compared with -unexposed children and 1.25 (95% CI, 1.18-1.32) for oxytocin-exposed compared with -unexposed children (Table 2, model A). Further adjusting for maternal sociodemographic characteristics and antenatal risk factors reduced the HRs to 1.30 (95% CI, 1.21-1.40) for LEA exposure and 1.12 (95% CI, 1.06-1.19) for oxytocin exposure (Table 2, model B). Additional adjustment for fetal distress, labor dystocia, and any birth defects did not substantially alter the HRs (Table 2, model C): LEA, 1.30 (95% CI, 1.20-1.39) and oxytocin, 1.11 (95% CI, 1.05-1.18). Analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting provided similar results, with HRs of 1.30 (95% CI, 1.18-1.43) for LEA and 1.10 (95% CI, 1.04-1.17) for oxytocin.

Table 2. Hazard Ratios of ASD in Offspring Associated With LEA and/or Oxytocin Exposures at Labor and Delivery.

| Variable | No. with ASD/total | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Aa | Model Bb | Model Cc | ||

| Single exposure | ||||

| Epidural | ||||

| No | 979/52 114 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 4167/153 880 | 1.41 (1.31-1.51) | 1.30 (1.21-1.40) | 1.30 (1.20-1.39) |

| Oxytocin | ||||

| No | 1927/88 186 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 3219/117 808 | 1.25 (1.18-1.32) | 1.12 (1.06-1.19) | 1.11 (1.05-1.18) |

| Mutually adjusted | ||||

| Epidural | ||||

| No | 979/52 114 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 4167/153 880 | 1.33 (1.24-1.44) | 1.28 (1.18-1.38) | 1.27 (1.18-1.38) |

| Oxytocin | ||||

| No | 1927/88 186 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 3219/117 808 | 1.15 (1.08-1.22) | 1.05 (0.99-1.12) | 1.05 (0.98-1.11) |

| Stratifiedd | ||||

| Unexposed to LEA and oxytocin | 729/38 507 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Exposed to oxytocin only | 250/13 607 | 0.98 (0.85-1.14) | 0.90 (0.78-1.04) | 0.90 (0.78-1.04) |

| Exposed to LEA only | 1198/49 679 | 1.25 (1.14-1.37) | 1.20 (1.09-1.32) | 1.19 (1.09-1.31) |

| Exposed to LEA and oxytocin | 2969/104 201 | 1.48 (1.36-1.61) | 1.30 (1.20-1.42) | 1.29 (1.19-1.41) |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorders; HR, hazard ratio; LEA, labor epidural analgesia.

Adjusted for birth year only; birth year was modeled as a spline function with 4 df.

Adjusted for birth year, maternal age at delivery, race and ethnicity, educational level, household income, marital status, parity, history of comorbidity, prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, diabetes, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, hypothyroidism, infection, seizures, mental health issues, smoking, alcohol, drug use during pregnancy, antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, birth weight, preterm status, child sex, and medical center. Other than birth year, all other continuous variables were modeled as linear function and categorical variables were modeled as categorical variables.

Adjusted for covariates listed in note b along with birth defect, fetal distress, and dystocia.

Exposure stratification generated 1 variable with 4 levels: (1) unexposed, (2) exposed to oxytocin only, (3) exposed to LEA only, and (4) exposed to both LEA and oxytocin.

Including both LEA and oxytocin in the same model (ie, mutually adjusting) attenuated HRs for LEA and oxytocin exposures compared with single-exposure models (Table 2, mutually adjusted vs single exposure). The HRs were 1.28 (95% CI, 1.18-1.38) for LEA and 1.05 (95% CI, 0.99-1.12) for oxytocin in the fully adjusted model (Table 2, mutually adjusted, model B). The HR for LEA exposure was 1.28 (95% CI, 1.19-1.38) when adjusted for induction and augmentation instead of oxytocin exposure, thus comparable to results adjusted for oxytocin alone.

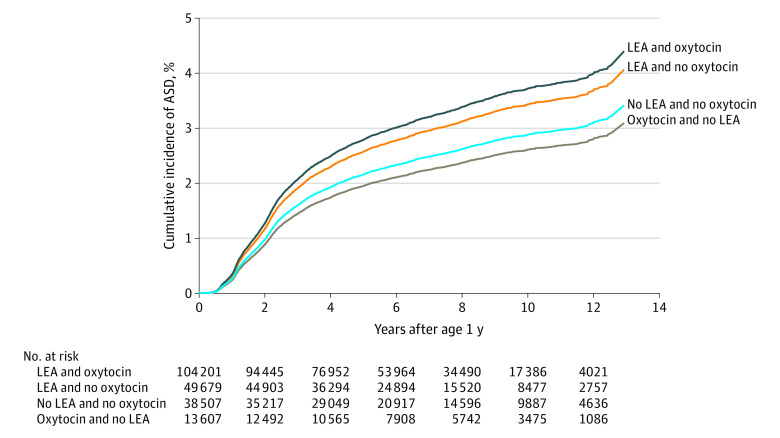

A significant interaction between LEA and oxytocin exposures on offspring ASD risk was found (P = .02 for interaction in models B and C). Table 2 presents HRs stratified by the combination of LEA and oxytocin exposures. For model B, compared with neither exposure group, HRs were 0.90 (95% CI, 0.78-1.04) for children exposed to oxytocin only, 1.20 (95% CI, 1.09-1.32) for children exposed to LEA only (approximate 20% increase), and 1.30 (95% CI, 1.20-1.42) for those exposed to both LEA and oxytocin (approximate 30% increase). The HR for those exposed to both LEA and oxytocin was significantly higher than the HR for the oxytocin alone (P = .02). The percentage of children with ASD was 2.8% for those exposed to both, 2.4% for those exposed to LEA only, 1.8% for those exposed to oxytocin only, and 1.9% for children exposed to neither intervention. The Figure depicts the covariate-adjusted cumulative incidence of ASD by LEA and oxytocin exposure.

Figure. Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) by Labor Epidural Analgesia (LEA) and Oxytocin Exposure.

Covariates adjusted include birth year (modeled as a spline function with 4 df), maternal age at delivery, race and ethnicity, educational level, household income, marital status, parity, history of comorbidity, prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, diabetes, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, hypothyroidism, infection, seizures, mental health issues, smoking, alcohol, drug use during pregnancy, antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, birth weight, preterm status, child sex, and medical center. Other than birth year, all other continuous variables were modeled as linear function and categorical variables were modeled as categorical variables.

Sensitivity analysis excluding 12 091 children who were preterm (<37 weeks) or postterm (>42 weeks) births provided similar results as the full cohort (Table 3). Excluding 5303 deliveries involving forceps or vacuum resulted in HRs of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.79-1.06) for oxytocin only, 1.19 (95% CI, 1.08-1.31) for LEA only, and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.20-1.43) for LEA and oxytocin exposure compared with no exposures.

Table 3. Hazard Ratios of ASD in Offspring Associated With LEA and/or Oxytocin Exposure at Labor and Delivery, Excluding 11 473 Children With Preterm (<37 Weeks) or Postterm Birth (>42 Weeks).

| Variable | No. with ASD/total | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Aa | Model Bb | Model Cc | ||

| Single exposure | ||||

| Epidural | ||||

| No | 872/48 538 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 3836/145 365 | 1.44 (1.33-1.55) | 1.31 (1.22-1.42) | 1.31 (1.21-1.41) |

| Oxytocin | ||||

| No | 1747/83 100 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 2961/110 803 | 1.27 (1.19-1.35) | 1.14 (1.07-1.21) | 1.13 (1.06-1.20) |

| Mutually adjusted | ||||

| Epidural | ||||

| No | 872/48 538 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 3836/145 365 | 1.35 (1.25-1.46) | 1.28 (1.18-1.39) | 1.28 (1.18-1.39) |

| Oxytocin | ||||

| No | 1747/83 100 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 2961/110 803 | 1.16 (1.09-1.24) | 1.06 (1.00-1.14) | 1.06 (0.99-1.13) |

| Stratifiedd | ||||

| Unexposed to both | 650/36 001 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Exposed to oxytocin only | 222/12 537 | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) | 0.92 (0.79-1.07) | 0.92 (0.78-1.07) |

| Exposed to epidural only | 1097/47 099 | 1.26 (1.14-1.39) | 1.21 (1.09-1.33) | 1.20 (1.09-1.33) |

| Exposed to both | 2739/98 266 | 1.52 (1.39-1.66) | 1.33 (1.21-1.45) | 1.32 (1.20-1.44) |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorders; HR, hazard ratio; LEA, labor epidural analgesia.

Adjusted for birth year only; birth year was modeled as a spline function with 4 df.

Adjusted for birth year, maternal age at delivery, race and ethnicity, educational level, household income, marital status, parity, history of comorbidity, prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, diabetes, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, hypothyroidism, infection, seizures, mental health issues, smoking, alcohol, drug use during pregnancy, antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, birth weight, preterm status, child sex, and medical center. Other than birth year, all other continuous variables were modeled as linear function and categorical variables were modeled as categorical variables.

Adjusted for covariates listed in note b along with birth defect, fetal distress, and dystocia.

Exposure stratification generated 1 variable with 4 levels: (1) unexposed, (2) exposed to oxytocin only, (3) exposed to LEA only, and (4) exposed to both LEA and oxytocin.

Of 85 246 children with siblings born to 39 689 unique mothers, 73% were exposed to LEA, 54% were exposed to oxytocin, and 2.4% had an ASD diagnosis; these rates were comparable to those of the full cohort. Among the siblings, 24% had discordant LEA and 47% had discordant oxytocin exposures. The HRs in model B for the stratified combination of LEA and oxytocin were 0.94 (95% CI, 0.75-1.18) for oxytocin only, 1.19 (95% CI, 1.03-1.37) for LEA only, and 1.32 (95% CI, 1.16-1.51) for LEA and oxytocin exposure compared with no exposure. Thus, these results were similar to those of the full cohort analysis.

Discussion

In this extended birth cohort study including births from 2008 to 2015 in a previous study5 as well as births from 2016 and 2017 and extending follow-up time up to December 2021, we noted an elevated risk associated with LEA exposure for vaginal delivery remained, albeit slightly reduced after adjusting for additional perinatal risk factors including oxytocin exposure. The risk of ASD associated with oxytocin exposure was not independent of LEA exposure. We also found significant synergistic associations between LEA and oxytocin exposure associated with child ASD risk. Risk was approximately 20% greater with LEA exposure alone, compared with those unexposed after adjusting for multiple maternal, neonatal, and obstetric risk factors. Risk was 30% greater after exposure to both LEA and oxytocin compared with exposure to neither. However, we did not find significant ASD risk associated with oxytocin alone. Our results call for more in-depth studies in varying study populations and practice to understand the complexity of labor and delivery and assess the long-term safety of a barrage of maternal medical interventions during labor and delivery, including LEA and oxytocin, on child health outcomes.

The relative risk associated with LEA exposure estimated in our study was higher than in population studies from Manitoba, Canada (HR, 1.08)6; Denmark (HR, 1.05)7; British Columbia, Canada (HR, 1.09)8; the US, using insurance records (HR, 1.08)9; and Ontario, Canada (HR, 1.14).10 There are large population, access to care, and practice differences that may explain these varied results. For example, there are substantial differences in LEA exposure rates between cohorts. The LEA exposure rate was 38% in Manitoba,6 19% in Denmark,7 29% in British Columbia,8 53% in US insurance records,9 and 64% in Ontario.10 Exposure to LEA was 74.7% in our cohort, which is the highest among the large cohort studies. Kaiser Permanente Southern California provides LEA upon patient’s request at any time with no additional cost, which may facilitate easy access. We used both anesthesia procedure notes and pharmacy records from EMRs to obtain data on LEA exposure, which we believe captured LEA exposure more completely than administrative data sources. Our LEA rate is in agreement with current reports from high-income countries and is similar to the rate reported in the 2020 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Vital Statistics (77.1%).26 There are also differences in the rates of ASD. In each study reporting ASD rates by LEA exposure, rates were higher in children exposed to LEA than those unexposed6,8,9,10; however, ASD rates in both the exposed and unexposed groups were higher in the KPSC cohort than in any of the previous studies (LEA exposure: 2.7%; no LEA exposure: 1.9%). At KPSC, children were screened for developmental issues at age 18 months and diagnoses were made by developmental specialists. We extracted the ASD diagnosis based on coding with at least 2 different encounters visits and the validity has been established in previous studies.19,20,21

The findings of this study suggest that previously reported ASD risk associated with oxytocin exposure14,15 was not independent of LEA exposure, and there may be a synergistic association between oxytocin and LEA exposure and a child’s ASD risk. Oxytocin is commonly used to induce or augment labor. Oxytocin administration may strengthen uterine contractions or hyperstimulation and labor pain, requiring early LEA intervention.27 Although the cohort design of this study does not allow causal evaluation, our data on LEA exposure and oxytocin use are consistent with previous reports that concurrent exposure to oxytocin and LEA is common.28,29,30 Further studies are needed to confirm our study findings and reveal biological links before making conclusions.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is the assessment of the synergistic association between LEA and oxytocin exposure and ASD risk in offspring. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to separate ASD risk associated with LEA and oxytocin. The results presented herein benefited from the stable membership, long-term follow-up, and high quality and comprehensive EMR system within Kaiser Permanente, a large, integrated health care system with standard practice within the US. This allowed us to retrieve data on exposures, outcomes, and covariates with confidence. The KPSC cohort is representative of the study population; results may be generalized to Southern California more broadly and potentially to other urban health care systems in the US. Furthermore, although our study was retrospective, all original data were collected prospectively.

Our study has limitations. Although we adjusted for many potential confounders, residual confounding due to unmeasured covariates, including paternal covariates, genetics, and other environmental exposures responsible for observed associations, may still exist. In addition, our study did not investigate dose and duration outcomes and temporal trends in oxytocin use, LEA exposure, and ASD risk.

Conclusions

In this clinical cohort from an integrated health care system servicing a mostly urban population, maternal LEA exposure for vaginal delivery was associated with increased ASD risk in offspring. This risk was further increased if oxytocin was also administered. Oxytocin exposure without LEA exposure was not associated with ASD risk in offspring. Further studies are warranted to replicate or refute our study results and examine biological plausibility. Public benefit and risk need to be considered when selecting medical interventions given the benefits of LEA and oxytocin for labor and labor pain management and relatively low incidence and multifactorial risk factors for ASD.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Halpern SH, Muir H, Breen TW, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing patient-controlled epidural with intravenous analgesia for pain relief in labor. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(5):1532-1538. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000136850.08972.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howell CJ, Kidd C, Roberts W, et al. A randomised controlled trial of epidural compared with non-epidural analgesia in labour. BJOG. 2001;108(1):27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim Y, Ocampo CE, Supandji M, Teoh WH, Sia AT. A randomized controlled trial of three patient-controlled epidural analgesia regimens for labor. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(6):1968-1972. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181887ffb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang F, Shen X, Guo X, Peng Y, Gu X; Labor Analgesia Examining Group (LAEG) . Epidural analgesia in the latent phase of labor and the risk of cesarean delivery: a five-year randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(4):871-880. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b55e65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiu C, Lin JC, Shi JM, et al. Association between epidural analgesia during labor and risk of autism spectrum disorders in offspring. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(12):1168-1175. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wall-Wieler E, Bateman BT, Hanlon-Dearman A, Roos LL, Butwick AJ. Association of epidural labor analgesia with offspring risk of autism spectrum disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(7):698-705. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkelsen AP, Greiber IK, Scheller NM, Lidegaard Ø. Association of labor epidural analgesia with autism spectrum disorder in children. JAMA. 2021;326(12):1170-1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanley GE, Bickford C, Ip A, et al. Association of epidural analgesia during labor and delivery with autism spectrum disorder in offspring. JAMA. 2021;326(12):1178-1185. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straub L, Huybrechts KF, Mogun H, Bateman BT. Association of neuraxial labor analgesia for vaginal childbirth with risk of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2140458. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy MSQ, Ducharme R, Hawken S, et al. Exposure to intrapartum epidural analgesia and risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2214273. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panesar K. Pharmacologic agents used in obstetrics. US Pharm. 2012;37(9):HS2-HS6. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/pharmacologic-agents-used-in-obstetrics [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Lausin L, Perez-Botella M, Duran X, et al. Relation between length of exposure to epidural analgesia during labour and birth mode. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2928. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16162928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng H, Guo F, Lin B, et al. The effects of epidural analgesia using low-concentration local anesthetic during the entire labor on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective group study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301(5):1153-1158. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05511-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zinni M, Colella M, Batista Novais AR, Baud O, Mairesse J. Modulating the oxytocin system during the perinatal period: a new strategy for neuroprotection of the immature brain? Front Neurol. 2018;9:229. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregory SG, Anthopolos R, Osgood CE, Grotegut CA, Miranda ML. Association of autism with induced or augmented childbirth in North Carolina Birth Record (1990-1998) and Education Research (1997-2007) databases. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(10):959-966. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soltys SM, Scherbel JR, Kurian JR, et al. An association of intrapartum synthetic oxytocin dosing and the odds of developing autism. Autism. 2020;24(6):1400-1410. doi: 10.1177/1362361320902903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espada-Trespalacios X, Ojeda F, Perez-Botella M, et al. Oxytocin administration in low-risk women, a retrospective analysis of birth and neonatal outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4375. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012;16(3):37-41. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang AH, Wang X, Martinez MP, et al. Association of maternal diabetes with autism in offspring. JAMA. 2015;313(14):1425-1434. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiang AH, Wang X, Martinez MP, Page K, Buchanan TA, Feldman RK. Maternal type 1 diabetes and risk of autism in offspring. JAMA. 2018;320(1):89-91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman KJ, Lutsky MA, Yau V, et al. Validation of autism spectrum disorder diagnoses in large healthcare systems with electronic medical records. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(7):1989-1996. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2358-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris T, Schulman M. Race inequality in epidural use and regional anesthesia failure in labor and birth: an examination of women’s experience. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2014;5(4):188-194. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nevison C, Parker W. California autism prevalence by county and race/ethnicity: declining trends among wealthy Whites. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(11):4011-4021. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04460-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kearns RJ, Shaw M, Gromski PS, Iliodromiti S, Lawlor DA, Nelson SM. Association of epidural analgesia in women in labor with neonatal and childhood outcomes in a population cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2131683. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.31683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therneau TM, Crowson CS, Atkinson EJ. Adjusted survival curves. January 2015. Accessed June 9, 2023. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/vignettes/adjcurve.pdf

- 26.Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Driscoll AK, Valenzuela CP. National vital statistics reports: supplemental tables. February 7, 2022. Accessed June 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr70/nvsr70-17-tables.pdf

- 27.Jonsson M, Nordén-Lindeberg S, Ostlund I, Hanson U. Acidemia at birth, related to obstetric characteristics and to oxytocin use, during the last two hours of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(7):745-750. doi: 10.1080/00016340802220352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner J, Flatley C, Kumar S. Epidural use in labour is not associated with an increased risk of maternal or neonatal morbidity when the second stage is prolonged. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;60(3):336-343. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grivell RM, Reilly AJ, Oakey H, Chan A, Dodd JM. Maternal and neonatal outcomes following induction of labor: a cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(2):198-203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rousseau A, Burguet A. Oxytocin administration during spontaneous labor: guidelines for clinical practice—chapter 5: maternal risk and adverse effects of using oxytocin augmentation during spontaneous labor. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46(6):509-521. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement