Abstract

Incidental dural tears being a familiar complication in spine surgery could result in dreaded postoperative outcomes. Though the literature pertaining to their incidence and management is vast, it is limited by the retrospective study designs and smaller case series. Hence, we performed a prospective study in our institute to determine the incidence, surgical risk factors, complications and surgical outcomes in patients with unintended durotomy during spine surgery over a period of one year. The overall incidence in our study was 2.3% (44/1912). Revision spine surgeries in particular had a higher incidence of 16.6%. The average age of the study population was 51.6 years. The most common intraoperative surgical step associated with dural tear was removal of the lamina, and 50% of the injuries were during usage of kerrison rongeur. The most common location of the tear was paramedian location (20 patients) and the most common size of the tear was about 1 mm-5mm (31 patients). We observed that the dural repair techniques, placement of drain and prolonged post-operative bed rest didnot significantly affect the post-operative outcomes. One patient in our study developed persistent CSF leak, which was treated by subarachnoid lumbar drain placement. No patients developed pseudomeningocele or post-operative neurological worsening or re-exploration for dural repair. Wound complications were noted in 4 patients and treated by debridement and antibiotics. Based on our study, we have proposed a treatment algorithm for the management of dural tears in spine surgery.

Keywords: Dural tear, Spine surgery, Drain, Mobilization, Surgical risk factors, Management

1. Introduction

Incidental durotomies are commonly encountered complications during spine surgery. The reported incidence in literature varies from 1 to 17%,1,2 based on the type and complexity of the surgical procedure involved. Revision surgeries, dural calcifications/adhesions are several risk factors that have been widely reported with a higher incidence of dural tears. Dural injuries can cause persistent CSF leakage resulting in devastating complications including delay in wound healing, surgical site infection, pseudomeningocele formation, arachnoiditis, and overall poor surgical outcomes.3,4 However, few authors have shown that there is no increase in perioperative morbidity or complications in patients with properly recognized and repaired tears. Most studies are retrospective and, there are still some dilemmas in appropriate intra, post-operative management and complications following dural injury. Hence, we conducted a prospective study to identify various intra-operative risk factors, management strategies and complications following incidental dural injury and to provide an algorithm for the treatment of incidental durotomies in elective spine surgery.

Table 1.

Details of the surgeries performed.

| Pathology | No. of cases | Procedure performed |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical and Occipito-cervical: 5 cases | ||

| Multi-level disc osteophyte complex | 3 | Posterior: Laminectomy (2 cases) Anterior: Corpectomy and plating (1 case) |

| Basilar invagination with instability | 1 | Foramen magnum decompression and Occipito-cervical fusion |

| Basilar invagination | 1 | Foramen magnum decompression |

| Thoracic: 7 cases | ||

| Spondylodiscitis | 3 | Debridement with instrumentation |

| Ossified posterior Longitudinal ligament | 3 | Instrumented Decompression |

| Congenital kyphoscoliosis | 1 | Deformity correction |

| Lumbar: 32 cases | ||

| Lumbar disc prolapse | 13 | Microdiscectomy (7 cases) |

| (recurrent disc prolapse): | 4 | Fusion (5 cases) |

| (calcified disc): | 3 | Endoscopic discectomy (1 case) |

| Lumbar canal stenosis | 10 | Laminectomy (5 cases) Fusion (5 cases) |

| Spondylolisthesis | 5 | Fusion (5 cases) |

| Infection | 3 | Debridement with instrumentation (2 cases) Debridement (1 case) |

| Facetal synovial cyst | 1 | Fusion |

Table 2.

Surgical step during dural injury.

| Intra-operative event causing dural tear | No. of cases (Total:44) |

|---|---|

| Surgical Exposure | 6 |

| Removal of lamina | 29 |

| Disc removal during disectomy | 6 |

| Disc space preparation during interbody fusion | 2 |

| Cage insertion during fusion | 1 |

Table 3.

Showing the surgical step that resulted in dural injury.

| Surgical instrument causing dural tear | No. of tears (Total: 44) |

|---|---|

| Kerrison rongeur | 24 |

| Electrocautery | 7 |

| Pituitary rongeur | 4 |

| Surgical blade | 2 |

| Curette | 2 |

| Dural retractor | 1 |

| Endoscopic disc forceps | 1 |

| High speed burr | 1 |

| Osteotome | 1 |

| Nibbler | 1 |

Table 4.

Characteristics of dural tear and repair technique.

| Location of the dural tear | No. of tears (Total: 44) |

|---|---|

| Posterior | |

| Para Median | 23 |

| Midline | 12 |

| Shoulder of the traversing nerve root | 6 |

| Axilla of the traversing nerve root | 2 |

| Anterior | 1 |

| Size of the dural tear | |

| Punctuate (<1 mm) | 4 |

| 1 mm–5mm | 31 |

| >5 mm | 9 |

| Durotomy repair method | No. of patients |

| Primary dural repair | 12 |

| Primary dural repair with dural graft | 16 |

|

11 |

| with fibrin sealant | 6 |

| without fibrin sealant | 5 |

| Only water tight wound closure | 5 |

Table 5.

Showing several critical steps resulting in dural injury during spine surgery and strategies for prevention.

| During exposure | Cause | Avoidance |

|---|---|---|

| High grade spondylolisthesis | Due to the stretched and taut ligamentum flavum | Care while using cautery tips in the inter-laminar area and use of cautery only over bony surfaces |

| Congenital spinal disorders | Altered bony anatomy | Proper planning with adequate pre-operative imaging |

| Revision surgeries |

Loss of normal bony structures |

Careful visualization of the bony defects in pre-operative imaging Use of operating microscope intra-operatively |

| During Decompression |

Cause |

Avoidance |

| Severe canal stenosis | Loss of epidural fat and thinned out dura, less space available for the passage of spinal instruments | Use of high speed burr and osteotomes, use of appropriate size rongeurs |

| Ossified ligamentum flavum/posterior longitudinal ligament | Adhesions to the dura, ossified dura | Avoid removing the calcified part adherent to the dura and allowing the flake to float, Pre-operative identification of signs of dural calcification like ‘double dural sign’ and extra precautions while exposure |

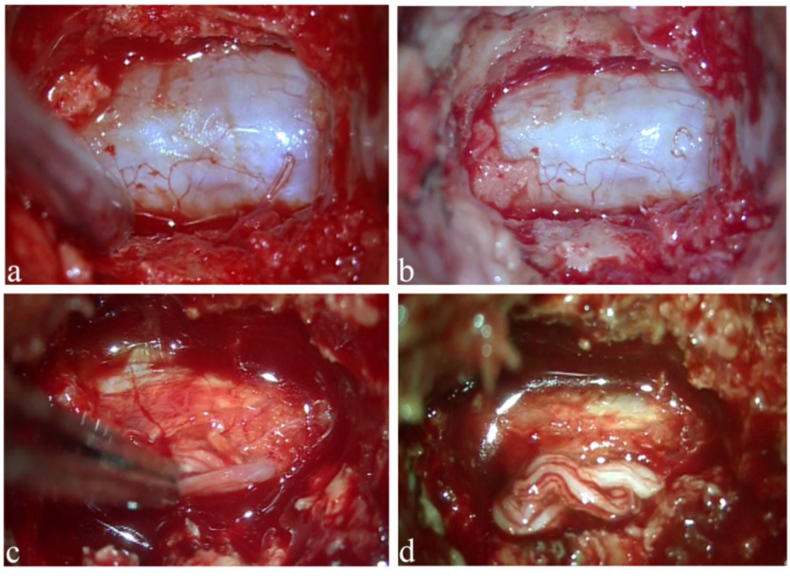

| Calcified disc (Fig. 2) | During retraction of thecal sac | Perform wide decompression of the canal before retraction of neural structures |

| Infective spondylodiscitis | Infected granulation tissue causing adhesions and dural thinning | Judicious use of spinal instruments |

| Complex spinal Deformity |

Proximity of the thecal sac to the bony elements on the concave side of the deformity near the apex |

Use of ultrasonic bone scalpel and forceps for bone removal |

| During instrumentation |

Cause |

Avoidance |

| Deformity surgeries | Smaller pedicle morphology | Selecting the appropriate pedicle for screw placement including proper screw size and including other techniques of fixation including sub-laminar wiring |

| Cage placement (especially in revision spine surgeries) | Retraction of thecal sac | Increase the bony window for cage placement rather than over retraction of the thecal sac |

2. Materials and methods

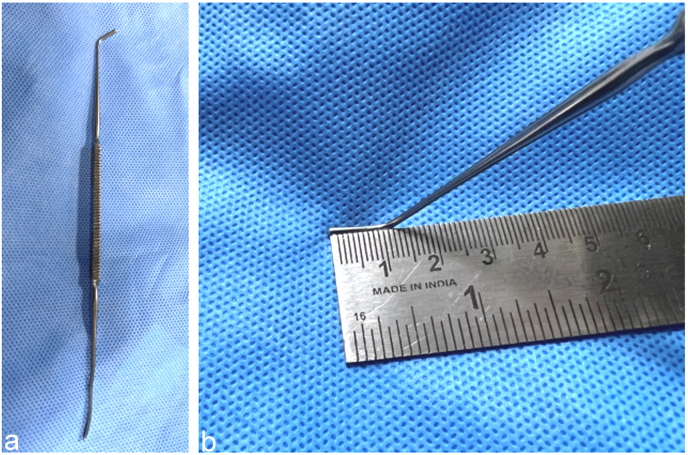

Our study is a prospective analysis of consecutive patients who sustained an iatrogenic dural injury in elective spine surgeries from the period of January 2021 to January 2022 at Ganga Hospital, Coimbatore. The study was conducted after institutional ethical board approval. A total of 1923 spine surgeries were performed during the study period, where durotomy was not intended as a part of the procedure. This excluded intradural procedures such as tethered cord releases, intradural lesions. We also excluded cases of traumatic spine injuries with dural tears found intraoperatively. Informed consent was obtained from the patients included in our study and all the surgeries were performed by three senior spine surgeons in our institute. The patients were identified at the time of the event of incidental durotomy, and details regarding the intraoperative surgical step and surgical instrument causing dural tear, location and size of the tear, repair techniques, placement of drains were noted. Uniformly in all these patients, as soon the tear was recognized intra-operatively, steps to identify the exact location and size of the tear (Fig. 1) were performed by widening the surgical exposure. PEEP was reduced with a minimal tidal volume. The defect was then clearly visualized and whenever possible, primary repair with round bodied 6–0 prolene was performed under an operating microscope. In patients where the surgeon felt, the primary dural repair was inadequate, or CSF leak was noted after valsalva manoeuvre, augmentation with autologous fat graft/synthetic collagen based dural graft (DuraGen- Integra Life Sciences Corp., Princeton, NJ, USA)/or fibrin sealant (Tisseel, Baxter, Westlake Village, CA) was performed. For inaccessible, small and irrepairable tears or where the dural edges could not be clearly defined, CSF leak was sealed with fat grafts/DuraGen based on the surgeon preference. The application of subfascial drain was based on the surgeon's decision intraoperatively and placed without negative pressure suction. Water tight closure (double layered fascial closure) of the surgical wound was performed in all the patients. In the immediate post-operative period, patients were monitored for the presence of clinical symptoms of persistent CSF leak (nausea, tightness in the neck or back, blurring of vision, postural headache, dizziness, diplopia due to sixth cranial nerve involvement, photophobia) and were recorded. The standard protocol in our institution is to place the patients in semi-fowler position on the first post-operative day and if the patient does not have any symptoms of CSF leak, mobilization is initiated. Otherwise, the patient is kept at bed rest till the symptoms subside. In patients with a subfascial drain, the collection is noted and drain removal is done when the collection is less than 50 ml over a period of 24 h. Patient details including demographic data, indication for the surgery, characteristics of the tear, repair technique, postoperative protocol were analysed. These patients were followed up at 1 month, 3 and 6 months and 1 year. The following outcomes were analysed in our study: presence/absence of symptoms pertaining to persistent CSF leak, early and late post-operative complications including infection, neurological worsening, pseudomeningocele formation and the need for re-exploration.

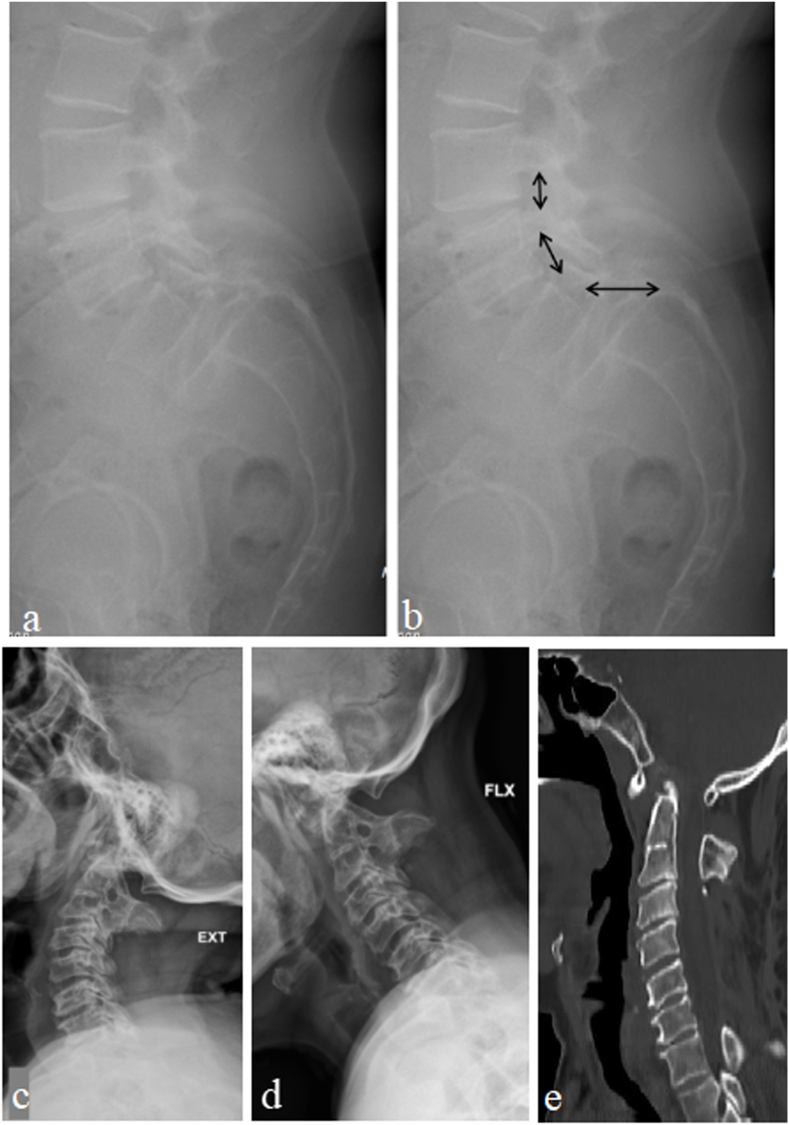

Fig. 1.

(a) Watson Cheyne nerve root dissector (b) Curved end of the dissector was used for the measurement of the length of dural tear and it corresponds to 10 mm.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data

There were a total of 1912 cases operated in our institution during the period of Feb 2021 to Feb 2022. This included 1846 primary spine surgeries and 66 revision spine surgeries. There were a total of 44 cases of incidental durotomies identified and formed the study cohort. The average age of the study population was 51.6 years and 61% (27 patients) of the population were males. Comorbidities including hypertension were present in 13 patients, diabetes mellitus in 11 patients and hypothyroidism in 3 patients. All the patients in the study were followed up for a minimum period of 12 (12–20) months, with an average follow up of 15.8 months.

3.2. Surgical data

Of the 44 patients with dural tear, 33 patients underwent primary spine surgery and 11 patients underwent revision surgeries. All patients except one (anterior) underwent posterior only approach. Thirty two patients had lumbosacral spine surgeries, 7 patients had thoracic spine surgery, three patients at cervical and 2 occipito-cervical surgeries (Table: 1). Of the 32 lumbosacral surgeries, 13 were decompression surgeries (laminectomy/discectomy), 16 cases were fusion surgeries, one patient underwent debridement for spondylodiscitis and two patients for post-operative surgical site infection.

All three cervical spine surgeries were performed in patients with myelopathy due to multilevel disc-osteophyte complex: two posterior (cervical laminectomy), one anterior (cervical corpectomy with anterior cervical plating) approach. Two patients underwent Occipito-cervical decompression surgeries (foramen magnum decompression) for congenital O–C junction anomalies (chiari malformation) with myelopathy. One of these patients also had instability at O–C junction with basilar invagination and hence occipito-cervical instrumentation was performed.

Of the 7 thoracic spine surgeries, 3 patients underwent debridement with instrumentation for spondylodiscitis, 3 patients underwent instrumented decompression for ossified ligamentum flavum, and 1 patient underwent deformity correction surgery. The detail of various surgical procedures is given in Table: 1.

3.3. Intra-operative event of dural tear

The most common intra-operative step that had dural tears was during removal of the lamina-29 patients (66%). Six patients (13.6%) had dural injury during surgical exposure. Removal of disc was associated with dural tear in six patients (13.6%). In three patients it was observed during the steps of instrumentation in lumbar fusion surgery [two patients (4.5%) it was observed during disc space preparation and one patient (2.3%) during interbody cage insertion] (Table: 2).

Kerrison rongeur was the most common instrument causing dural tear in 24 patients (54.5%), followed by electrocautery – 7 patients (15.9%), the other causes were pituitary rongeur – 4 patients (9%), surgical blade and curette in 2 patients each (4.5%), and one patient each by endoscopic disc forceps, high speed burr, osteotome, dural retractor probe and nibbler (Table: 3).

3.4. Characteristics of dural tear

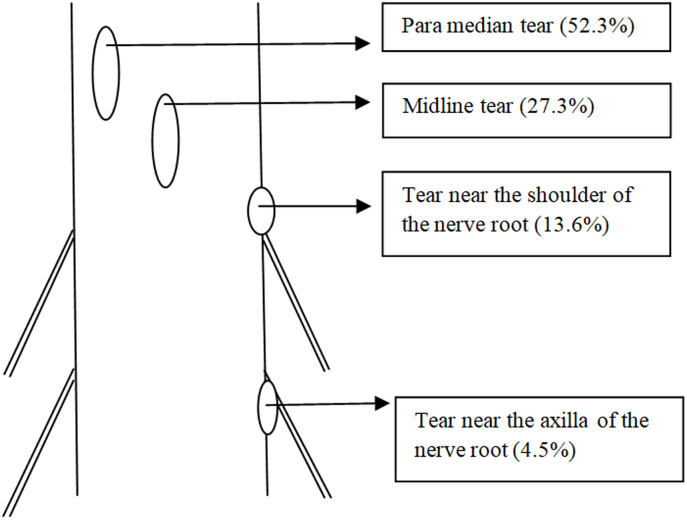

The commonest location of the injury was paramedian-23 patients (52.3%), followed by midline tears- 12 patients (27.3%), shoulder of the traversing nerve root- 6 patients (13.6%) and the axilla of the traversing nerve root- 2 patients (4.5%) (Table: 4) (Fig. 2). One patient had an injury to the anterior aspect of the dura at the cervical level, during cervical corpectomy using an anterior approach (Fig. 3). The size of the dural tear was <1 mm (punctate) in 4 patients, 1 mm-5mm in 31 patients and >5 mm in 9 patients (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Diagrammatic representation showing various locations of dural tears in our study.

Fig. 3.

Showing calcified ligamentous structures around the neural elements in the spinal canal: (a–b) Sagittal CT scan and MRI showing thick OPLL mass behind C6 vertebral body occupying about half of the spinal canal with cord signal changes; (c) Mid-sagittal CT scan image of thoracic spine showing ossified ligamentum flavum at multiple levels; (d) Axial CT scan images showing significant narrowing of the spinal canal; (e–f) Calcified L4-5, L5-S1 disc prolapsed. In all these patients there are high chances of dural tear during decompression.

Fig. 4.

Showing different sizes of dural tears during our study period- (a) punctate (<1 mm); (b) dural tear of size 1 mm–5 mm (c) dural tear of >5 mm size (d) shows that nerve roots at lumbar level lying outside the thecal sac.

Twelve patients underwent primary dural repair alone. Sixteen patients underwent primary repair with a combination of a fat autograft/DuraGen (Table: 4). In 11 patients, dural graft was applied (6 of those also had additional fibrin sealant). In 5 patients, repair could not be performed and only a watertight closure (double layered fascial closure) of the surgical wound was performed. Twenty one patients had placement of a subfascial drain without negative pressure suction.

3.5. Early post operative data

Postoperatively patients were kept for a variable period of bed rest depending on their symptoms related to CSF leakage and neurological status. During the immediate postoperative period, postural headache was the most common symptom noted in 4 patients and nausea with dizziness in two patients. Twenty seven patients were mobilized within 24 h following surgery and 14 patients were mobilized between 24 and 72 h. Three patients had significant preoperative neurological deficit, and hence, were not mobilized as per the protocol. One patient, who underwent posterior instrumented decompression for thoracic level ossified ligamentum flavum, developed symptoms of persistent CSF leak in the immediate post-operative period, which was treated by a lumbar subarachnoid drain placement with controlled intermittent CSF drainage. The lumbar drain was placed on the 3rd post-operative day and drainage of 10 ml/h was done daily for 3 days. The patient was maintained in strict bed rest. By the 6th post-operative day, the patient symptoms resolved, and the lumbar drain was removed and no recurrence of symptoms was noted.

3.6. Complications

In the early post-operative period, there were a total of 4 complications observed in our study. Two surgical site infections (1-superficial and 1-deep) and 2 patients presented with superficial wound dehiscence. The patient with deep surgical site infection underwent re-exploration, debridement and started on culture sensitive antibiotics and achieved good wound healing. The remaining 3 patients underwent debridement and resuturing. No patients developed a postoperative neurological deficit. There were no readmissions due to pseudomeningocele formation or re-exploration of the tear during the study period.

4. Discussion

Incidental durotomy is a well-known complication of spine surgeries that have been encountered more frequently in surgical practice because of the increasing number of primary and revision spine surgeries worldwide. As the indications of operative intervention for various spine-related pathologies are rising and with modern spinal instrumentation, it is important to understand the various risk factors and thereby management of these injuries is essential for the prevention of catastrophic complications. The overall incidence of dural injuries in our study was 2.3% with a higher incidence rate of 16.6% in revision surgery cases (total revision surgeries during the study period: 66 cases), which is consistent with the existing literature.5, 6, 7, 8 Though most of the studies in literature have primarily reported in lumbar spine surgeries, we have observed the overall incidence of dural tear in spine surgery due to various etiologies during the study period.

Iatrogenic intra-operative dural injury can occur at several instances during the surgical procedure starting from the time of surgical exposure or during the time of decompression to instrumentation. In general, revision surgeries have a higher chance of dural tear due to the loss of normal anatomical landmarks and post-operative adhesions with epidural scarring from the previous surgeries.9,10 Also, in revision cases, the extent of retraction of the thecal sac to access the disc anteriorly are very limited which further add to the high probability. Hence, great care must be ensured by the operating surgeon during exposure, decompression and retraction of the thecal sac and nerve roots around the scar tissues. During the surgical exposure in revision spine surgeries, a safer surgical practice is to extend the limits of previous surgical incision to identify the normal bony anatomy of the adjacent non-operated segments which also provides perception of the anatomical landmarks and depth at which the thecal sac and scar tissues could be encountered.

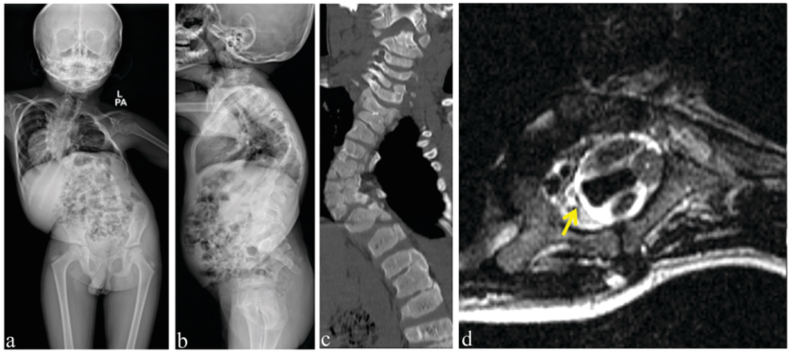

In our study, the surgical step which resulted in the most number of durotomies was during the removal of lamina and kerrison rongeur was the most common instrument that resulted in injury (54.5%). In patients with chronic lumbar canal stenosis, loss of epidural fat and thinning of the dura ensues with adhesions to the surrounding structures.11 This can also lead to the thecal sac getting trapped in while using the Kerrison rongeur. Hence it is essential to maintain the perpendicular placement of the kerrison over the dura and visualise the foot plate of kerrison at all times while performing decompression. Also, a kerrison rongeur with a smaller foot plate can result in entrapment of this thinned out dura by point contact compared to a broader foot plate. The surgeon must be aware of all these technique related aspects while using the kerrison rongeur. Similarly in patients with ossified ligamentum flavum (Fig. 3) there is a higher incidence of dural injury (3 patients in our study) especially when there is associated dural ossification. Epstein et al. in a study of 110 geriatric patients undergoing multilevel laminectomy and non-instrumented fusions found a close association of dural tear with calcified ligamentum flavum extending to the dura and with synovial cysts.12 Therefore such patients warrant a close study of preoperative imaging for the surgeon to exercise additional care and restraint during decompression at the affected levels.13 One of our patients with congenital thoracic kyphoscoliosis, had a dural tear during laminectomy at the apex of the deformity. In these complex spinal deformities, the dura will be in close proximity to the bony elements especially on the concave side of the deformity (Fig. 5). Also, adhesions at the apex around the thecal sac could be present, which further increases the risk of dural tears in these patients during decompression of the spinal cord.

Fig. 5.

(a–b) Whole spine PA and lateral radiograph showing thoracic kyphoscoliosis; (c) Coronal CT scan images showing multiple congenital vertebral bony abnormalities causing the deformity; (d) T2W axial MRI image at the apex of the scoliotic deformity showing the cord with the dura close to the left (concave) side of the vertebra [arrow points to the epidural fat on the right (convex) side].

In patients with high grade spondylolisthesis, there will be widened interlaminar space (Fig. 6) with a stretched and taut ligamentum flavum. Hence, there is a high chance of dural injury during surgical exposure using electrocautery. Therefore, the use of electrocautery should be done only when the tip of the cautery rests over the bone and the subperiosteal dissection should be performed. Care must be taken while dissecting the soft tissues in the interlaminar region and it is better to use only cobb's elevator for muscle dissection over this space and avoid using electrocautery. Similarly in congenital disorders such as chiari malformation, complex spinal deformity patients with altered bony anatomy dural tears due to electrocautery are prone to occur. One of our patients with O–C junction anomaly had atlanto-occipital assimilation, which increased the chances of dural puncture with electrocautery during dissection (Fig. 6). In our study, six patients had a dural injury during exposure with electrocautery. One of our patients had a dural tear with endoscopic disc forceps while performing discectomy during endoscopic uniportal interlaminar lumbar decompression surgery. No repair of the tear was attempted as the tear was very small and tight skin closure was performed. In Minimally Invasive Spine (MIS) surgeries, the potential dead space for CSF accumulation is negligible as the muscle fibres overlap and fill in. Hence, the chances of dural leakage are significantly reduced. However, the literature has proponents for both repair14,15 and no repair16 following endoscopic dural injury. Heo et al., recently reported the application of non-penetrating titanium clips for dural repair in biportal endoscopic lumbar spine surgery. They concluded that clipping is an effective option for endoscopic dural repair without conversion to open microsurgery.17

Fig. 6.

Case eg I: (a–b) Standing lateral radiograph of lumbar spine in a 50 years old female showing Grade III lytic Listhesis of L5 over S1. The arrow marks point to the attachment of ligamentum flavum in the interlaminar region. At L5-S1, the interlaminar region is widened causing stretch of ligamentum flavum due to the forward translation of L5 vertebra. Case eg II: (c–d) Dynamic Lateral cervical radiographs of a 30 years old male patient showing widening of Atlanto-Dens interval indicating instability at C1–C2; (e) Mid-sagittal and coronal CT scan image showing Atlanto-Occipital assimilation. Note that C1 posterior arch is small and is lying deep (patient has previously underwent cervical laminectomy) increasing the chances of cord injury during surgical exposure of C1–C2.

Traditionally, direct repair has been the gold standard in treatment of dural tears. Suture materials like monofilament polypropylene, braided nylon can be used due to their hydrostatic strength.18,19 Intra-operatively, it is important to identify the edges of the dural tear to attempt a successful repair and hence we recommend widening the surgical exposure for clear visualization of the edges. This includes both increasing the surgical incision and/or removing additional bone and soft tissues. Hematoma or debris should be washed away from the site of dural tear. Though few studies have shown no significant difference between continuous and intermittent suture techniques,18,20 we routinely use continuous suturing of the dural tear to obtain a water tight closure. In patients with ventral or venterolateral tears, large lacerated dural tears with wide loss of dura and tears along the nerve root sleeve, direct repair could not be possible (irreparable). In these instances, we routinely use synthetic/autologous grafts with or without fibrin sealant. While using fibrin sealant it is important to make sure that the sealant does not flow to the foraminal area. Alternate method like use of pedicled multifidus muscle flap21 has also been reported in literature for these irreparable tears.

Overall in our study, primary dural repair was performed in 9 patients, and dural repair with augmentation using synthetic/autologous graft was performed in 16 patients. In 14 patients only duragen patch was applied and sealed with fibrin glue. Synthetic grafts have evolved as an alternate option to the autologous fat and muscle grafts in dural repair. The proposed advantages include their ability to provide watertight seal and possibility of application in dural defects of irregular shapes and sizes. Patch effect, dead space filling effect, adherence and interstice filling effect are the important properties for these substitutes.22 In a clinicopathological study of synthetic dural grafts by Narotam et al., they observed that the collagenous matrix provided benefits through their chemotactic interaction with dural fibroblasts.23 In a retrospective review of 110 patients, they also showed that collagenous grafts alone were successful in sealing the tear in >95% patients.24 Grannum et al.25 in their study, observed that non-suturing repair methods including autologous/synthetic grafts can be successfully used to manage dural tears in lumbar spine surgery without any adverse events or complications. In our study, we didnot find any significant difference in the infection or complication rates comparing the various dural repair techniques. This is similar to the study by Kamenova et al.,26 where they compared three different dural repair techniques and observed no significant difference between primary repair, augmented primary repair and only patch application. Hence, application of patch only as a repair option can be used, if there are limitations for primary dural repair like location, configuration of the defect.

Regarding the usage of drains there is no clear consensus in the literature. Few authors have suggested routine placement of drains in all patients with dural tears,27, 28, 29 while several others30,31 have favoured the non-placement of drains as the epidural hematoma that is normally formed would act as a tamponade to the dural rent and drains could be a potential source of contamination and possibility of a duro-cutaneous fistula at the drain site also exists. In our study, we didnot observe any significant difference in the immediate postoperative complications or infection rates between the placement and non-placement of drains. We suggest that the decision for placement of drains should be depending on individual case basis, adequacy of the dural repair and anatomical dead space at the surgical site. The most common post-operative complication observed in our study was postural headache seen in 4 patients. Other symptoms noted were nausea and dizziness (two patients). Mobilization of these patients was delayed till the symptoms subsided. In all other patients mobilization was initiated as indicated for the spinal procedure performed. Prolonged bed rest has been traditionally advocated in literature to avoid persistent dural leak and by reducing the hydrostatic pressure at the dural tear repair site.22 However, the complications associated with prolonged immobilization of patients with dural tear have also been reported.32 In our study, we observed that there were no significant differences between early (<24 h) and late (>24 h) mobilization in dural tear patients regarding the incidence of pseudomeningocele or re-exploration. Our results are similar to the observation by Frashad et al.33 In their prospective randomized control study, they observed that among 94 patients with incidental durotomies, no significant difference was noted in terms of revision surgery or duration of hospital stay between early (<24 h) and late (>24 h) mobilization of patients and concluded that there was no benefit of prolonged bed rest after an adequately repaired dural tear in lumbar spine surgery. Najjar et al.34 in their systematic review in fact observed that complications like headaches, tinnitus, nausea, and vomiting were significantly reduced with early mobilization.

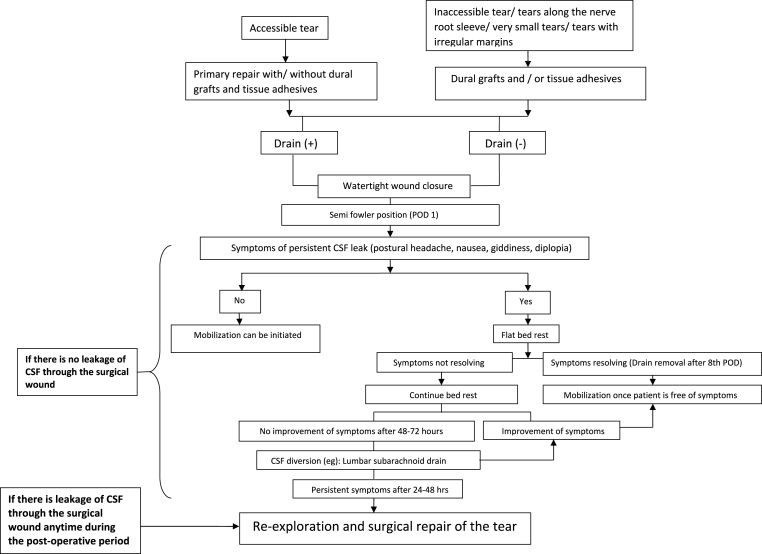

In our study, we applied intermittent controlled lumbar drain in one patient who underwent posterior instrumentation and decompression for thoracic ossified ligamentum flavum. The patient had a large size tear and underwent primary dural repair and duraGen application. However, post-operatively the patient continued to have symptoms of persistent dural leak and hence necessitated lumbar drain placement. The drain was placed for a period of 72 h till there was complete resolution of symptoms. Various lesser invasive techniques have been reported in literature for persistent CSF leak including epidural blood patch, over sewing the wound and subarachnoid lumbar drain placement. The use of continuous lumbar drain for persistent CSF leak was initially described by Voursh et al.,35 and they found to have a high success rate of 98% in managing patients with CSF accumulation at the surgical site, CSF leaks, CSF rhinorrhea with minimal morbidity.36,37 No patients developed post-operative neurodeficit, pseudomeningocele or needed surgical re-exploration and repair during our study period. Based on our observation, we have proposed a treatment algorithm for patients with incidental dural tear (Fig. 7) and highlighted few critical surgical steps and strategies for their prevention (Table: 5).

Fig. 7.

Flowchart showing our algorithm for the management of incidental dural tears during spine surgery.

Limitations of our study include a heterogenous study group with varied spine pathology and type of surgery performed. Post-operative MRI was not performed routinely in our patients. It is a single centre study and with a relatively shorter follow-up period. Though many studies have described various risk factors, complications of incidental durotomies and their management,1,9,38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 most of them are retrospective. In our study we were able to prospectively assess the operative details like intra operative step involved, surgical instrument that resulted in the tear, intra- and post operative management. This provides a significantly better quality of evidence compared to retrospective studies available in literature.

5. Conclusion

Overall, the most important aspect of management of dural tears is prevention and can largely be done by careful pre-operative planning, safe surgical techniques and by following surgical pause at the anticipated critical steps of the surgery. Intra-operative vigilance is essential for recognizing this complication and whenever detected, a meticulous and appropriate management with a proper postoperative protocol provide optimal outcomes.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions declarations

All authors contributed equally towards the preparation of this manuscript

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Tafazal S.I., Sell P.J. Incidental durotomy in lumbar spine surgery: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2005 Apr;14(3):287–290. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0821-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalevski S.K., Peev N.A., Haritonov D.G. Incidental Dural Tears in lumbar decompressive surgery: incidence, causes, treatment, results. Asian J Neurosurg. 2010;5(1):54–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitchel S.H., Eismont F.J., Green B.A. Closed subarachnoid drainage for management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after an operation on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989 Aug;71(7):984–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slipman C.W., Derby R., Simeone F.A., Mayer T.G. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007. Interventional Spine E-Book: An Algorithmic Approach; p. 1477. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghobrial G.M., Theofanis T., Darden B.V., Arnold P., Fehlings M.G., Harrop J.S. Unintended durotomy in lumbar degenerative spinal surgery: a 10-year systematic review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2015 Oct;39(4):E8. doi: 10.3171/2015.7.FOCUS15266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosacco S.J., Gardner M.J., Guille J.T. Evaluation and treatment of dural tears in lumbar spine surgery: a review. Clin Orthop. 2001 Aug;389:238–247. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200108000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espiritu M.T., Rhyne A., Darden B.V. Dural tears in spine surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010 Sep;18(9):537–545. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cammisa F.P., Girardi F.P., Sangani P.K., Parvataneni H.K., Cadag S., Sandhu H.S. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine. 2000 Oct 15;25(20):2663–2667. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan M.H., Rihn J., Steele G., et al. Postoperative management protocol for incidental dural tears during degenerative lumbar spine surgery: a review of 3,183 consecutive degenerative lumbar cases. Spine. 2006 Oct 15;31(22):2609–2613. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000241066.55849.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stolke D., Sollmann W.P., Seifert V. Intra- and postoperative complications in lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 1989 Jan;14(1):56–59. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198901000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shetty A., Anand M., Goparaju P., et al. A prospective study of the accidental durotomies in microendoscopic lumbar spine decompression surgeries. Incidence, surgical outcomes, postoperative patient mobilization protocol. J Minim Invasive Spine Surg Tech. 2022 Sep 22;7(2):202–209. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein N.E. The frequency and etiology of intraoperative dural tears in 110 predominantly geriatric patients undergoing multilevel laminectomy with noninstrumented fusions. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007 Jul;20(5):380–386. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31802dabd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muthukumar N. Dural ossification in ossification of the ligamentum flavum: a preliminary report. Spine. 2009 Nov 15;34(24):2654–2661. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b541c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teli M., Lovi A., Brayda-Bruno M., et al. Higher risk of dural tears and recurrent herniation with lumbar micro-endoscopic discectomy. Eur Spine J. 2010 Mar 1;19(3):443–450. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn Y., Lee H.Y., Lee S.H., Lee J.H. Dural tears in percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy. Eur Spine J. 2011 Jan 1;20(1):58–64. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soliman H.M. Irrigation endoscopic decompressive laminotomy. A new endoscopic approach for spinal stenosis decompression. Spine J. 2015 Oct 1;15(10):2282–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heo D.H., Ha J.S., Lee D.C., Kim H.S., Chung H.J. Repair of incidental durotomy using sutureless nonpenetrating clips via biportal endoscopic surgery. Global Spine J. 2022 Apr;12(3):452–457. doi: 10.1177/2192568220956606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dafford E.E., Anderson P.A. Comparison of dural repair techniques. Spine J. 2015 May 1;15(5):1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghobrial G.M., Maulucci C.M., Viereck M.J., et al. Suture choice in lumbar dural closure contributes to variation in leak pressures: experimental model. Clin Spine Surg. 2017 Jul;30(6):272. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cain J.J., Dryer R.F., Barton B.R. Evaluation of dural closure techniques. Suture methods, fibrin adhesive sealant, and cyanoacrylate polymer. Spine. 1988 Jul 1;13(7):720–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Policicchio D., Boccaletti R., Dipellegrini G., Doda A., Stangoni A., Veneziani S.F. Pedicled multifidus muscle flap to treat inaccessible dural tear in spine surgery: technical note and preliminary experience. World Neurosurg. 2021 Jan 1;145:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff S., Kheirredine W., Riouallon G. Surgical dural tears: prevalence and updated management protocol based on 1359 lumbar vertebra interventions. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012 Dec 1;98(8):879–886. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narotam P.K., van Dellen J.R., Bhoola K.D. A clinicopathological study of collagen sponge as a dural graft in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg. 1995 Mar;82(3):406–412. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.3.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narotam P.K., José S., Nathoo N., Taylon C., Vora Y. Collagen matrix (DuraGen) in dural repair: analysis of a new modified technique. Spine. 2004 Dec 15;29(24):2861–2867. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000148049.69541.ad. ; discussion 2868-2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grannum S., Patel M.S., Attar F., Newey M. Dural tears in primary decompressive lumbar surgery. Is primary repair necessary for a good outcome? Eur Spine J. 2014 Apr;23(4):904–908. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-3159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamenova M., Leu S., Mariani L., Schaeren S., Soleman J. Management of incidental dural tear during lumbar spine surgery. To suture or not to suture? World Neurosurg. 2016 Mar 1;87:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes S.A., Ozgur B.M., German M., Taylor W.R. Prolonged Jackson-Pratt drainage in the management of lumbar cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Surg Neurol. 2006 Apr;65(4):410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.11.052. discussion 414-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tafazal S.I., Sell P.J. Incidental durotomy in lumbar spine surgery: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2005 Apr 1;14(3):287–290. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0821-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niu T., Lu D.S., Yew A., et al. Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak rates with subfascial epidural drain placement after intentional durotomy in spine surgery. Global Spine J. 2016 Dec;6(8):780–785. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1582392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosacco S.J., Gardner M.J., Guille J.T. Evaluation and treatment of dural tears in lumbar spine surgery: a review. Clin Orthop. 2001 Aug;389:238–247. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200108000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eismont F.J., Wiesel S.W., Rothman R.H. Treatment of dural tears associated with spinal surgery. JBJS. 1981 Sep;63(7):1132–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ke R., Gd S., Ck K., et al. Complications of flat bed rest after incidental durotomy. Clin Spine Surg. 2016;29(7):281–284. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31827d7ad863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farshad M., Aichmair A., Wanivenhaus F., Betz M., Spirig J., Bauer D.E. No benefit of early versus late ambulation after incidental durotomy in lumbar spine surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2020 Jan;29(1):141–146. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Najjar E. 80. Early mobilization after incidental durotomy: a systematic review. Spine J. 2022 Sep 1;(9, Supplement):22. S44. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wahlig J.B., Welch W.C., Kang J.D., Jungreis C.A. Cervical intrathecal catheter placement for cerebrospinal fluid drainage: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 1999 Feb;44(2):419–421. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199902000-00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang C.I., Huang M.C., Chen I.H., Lee L.S. Diverse applications of continuous lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid in neurosurgical patients. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993 May;22(3 Suppl):456–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang Z., Tian R., Jia Y.T., Xu T.T., Liu Y. Treatment of cerebrospinal fluid leak after spine surgery. Chin J Traumatol Zhonghua Chuang Shang Za Zhi. 2017 Apr;20(2):81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alshameeri Z.A.F., El-Mubarak A., Kim E., Jasani V. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the management of accidental dural tears in spinal surgery: drowning in information but thirsty for a clear message. Eur Spine J. 2020 Jul;29(7):1671–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06401-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alshameeri Z.A.F., Jasani V. Risk factors for accidental dural tears in spinal surgery. Internet J Spine Surg. 2021 Jun 1;15(3):536–548. doi: 10.14444/8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshihara H., Yoneoka D. Incidental dural tear in lumbar spinal decompression and discectomy: analysis of a nationwide database. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013 Nov;133(11):1501–1508. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1843-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshihara H., Yoneoka D. Incidental dural tear in cervical spine surgery: analysis of a nationwide database. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015 Feb;28(1):19–24. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guerin P., El Fegoun A.B., Obeid I., et al. Incidental durotomy during spine surgery: incidence, management and complications. A retrospective review. Injury. 2012 Apr;43(4):397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi Y., Sato T., Hyodo H., et al. Incidental durotomy during lumbar spine surgery: risk factors and anatomic locations: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013 Feb;18(2):165–169. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.SPINE12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewandrowski K.U., Hellinger S., de Carvalho P.S.T., et al. Dural tears during lumbar spinal endoscopy: surgeon skill, training, incidence, risk factors, and management. Internet J Spine Surg. 2021 Apr 16;15(2):280–294. doi: 10.14444/8038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]