Abstract

Background

Ovarian epithelial tumors are common in adults, and their peak incidence of onset is over 40 years of age. In children, most ovarian tumors are germ cell-derived, whereas epithelial tumors are rare and mostly benign.

Case presentation

This report describes a case of a 14-year-old Chinese girl with ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. She was admitted with a small amount of bloody vaginal discharge during the past month. Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen and pelvis showed a large solid cystic mass lesion in the left ovary. Tumor marker levels were within normal limits ( CA-125: 22.3 U/mL, HE4: 28.5 pmol/L, HCG: < 1.20 mIU/ml, AFP: 3.3 ng/ml, CEA: 2.2 ng/ml, CA19-9: < 2.0 U/mL). Laparoscopic exploration revealed a large left ovarian tumor. The patient underwent left salpingo-oophorectomy, and showed no significant issues during follow-up, as well as no evidence of recurrence or metastasis.

Conclusions

We report the first pediatric case of ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma in China. Given the scarcity of reports addressing the clinical management of this condition, the present study provides a useful contribution to its further understanding in light of developing future treatment strategies.

Keywords: Ovarian epithelial tumor, Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, Children, Case Report

Background

The incidence of epithelial ovarian tumors in children is low, accounting for less than 20% among ovarian tumor types [1]. In addition, the vast majority of ovarian tumors in children are benign [2, 3], while malignant ovarian epithelial neoplasms are extremely rare. In this article, we report a case of a Chinese 14-year-old girl who developed ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma after menarche. To our knowledge, this is the fifteenth reported case of cystadenocarcinoma (ninth case of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma) in children worldwide. The age range of the 14 previously reported cases identified in PubMed using the following search terms: ovary, epithelial carcinoma or tumor, mucinous carcinoma or tumor, adolescent, children or pediatric, was 4–14 years, with eight cases of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma and six cases of other cancer types (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ovarian cystadenocarcinoma reported in the literature in < 15 years of age

| Case No. | Study | Age(yr) | Pre/postmenarchal | Operative | Histology | Adjuvant | Outcom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment | therapy | ||||||

| 1 | Hong et al. (1980) [4] | 4 | Pre | Right salphingo- | Serous | Methotrexate, | No recurrence after 7 months, Long term follow-up not available |

| oopherectomy | cyclophosphamide, | ||||||

| cis-diamminedicholoroplatinum | |||||||

| 2 | Blom et al. (1982) [5] | 4 | Pre | Right salphingo- | Serous | Intra peritoneal instillation of | No recurrence after 4 months, Long term follow-up not available |

| oopherectomy | 32phosphorus | ||||||

| 3 | Hernandez et al.(1982) [6] | 10 | Pre | Left salphingo- oopherectomy | Serous | Not given | No recurrence after 1.8 years,Longterm follow-up not available |

| 4 | Gribbon et al. (1992) [7] | NA | NA | Salphingo- | Serous | Pelvic radiotherapy | Disease free 17 years after diagnosis |

| oopherectomy | |||||||

| 5 | Gribbon et al. (1992) [7] | NA | NA | Salphingo- oopherectomy | Mucinous | Pelvic radiotherapy | Disease free 24 years after diagnosis |

| 6 | Skinner et al. (1992) [8] | 13 | NA | Salphingo- oopherectomy | Mucinous | Not given | Disease free 6 years after diagnosis |

| 7 | Shankar et al. (2001) [9] | 7 | Pre | Cytoreductive | Serous | Cyclophosphamide, | Died 12 years after diagnosis |

| surgery | cis-diamminedicholoroplatinum | ||||||

| 8 | Shankar et al. (2001) [9] | 8 | Pre | Left Salphingo- | Mucinous | Etoposide, carboplatin,bleomycin | In terminal care on last follow-up |

| oopherectomy | |||||||

| 9 | Shankar et al. (2001) [9] | 5 | Pre | Cytoreductive | Serous | cis-diamminedicholoroplatinum | In terminal care on last follow-up |

| surgery | |||||||

| 10 | Morowitz et al.(2003) [10] | NA | Pre | NA | Mucinous | Given | Died 1 years after diagnosis |

| 11 | Morowitz et al.(2003) [10] | NA | Post | Left Salphingo- | Mucinous | Not given | Disease free till last follow-up |

| oopherectomy | |||||||

| 12 | Morowitz et al.(2003) [10] | NA | Post | Salphingo- | Mucinous | Not given | Disease free till last follow-up |

| oopherectomy | |||||||

| 13 | Barkha et al. (2017) [1] | 14 | Post | Left Salphingo- | Mucinous | Cisplatin, paclitaxel | Disease free till last follow-up |

| oopherectomy | |||||||

| 14 | Agnieszka et al. (2022) [11] | 14 | Post | Left Salphingo- | Mucinous | Cisplatin, paclitaxel | Disease free till last follow-up |

| oopherectomy | |||||||

| 15 | Current study | 14 | Post | Left Salphingo- | Mucinous | Not given | Disease free till last follow-up |

| oopherectomy |

Case presentation

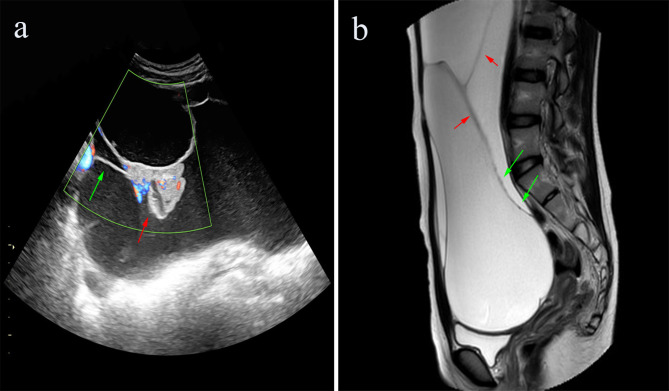

A 14-year-old girl was admitted to the gynecology outpatient department of Women and Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in April 2022, with complaints of a small amount of bloody vaginal discharge during the past month. Before this event she reported an average menstrual cycle of 25 days, with her menarche at the age of thirteen, and her periods averaging five days, with normal volume and no dysmenorrhea. In addition, the patient’s past medical history showed no history of infectious or genetic diseases, trauma, surgery, blood transfusion, drug or food allergies. Pelvic color doppler ultrasound scan revealed a mass with cystic and solid components in the left ovary extending upward to the inferior hepatic rim, downward to below the pubic symphysis, and forward to the anterior axillary line. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the abdomen and pelvis showed a large solid cystic mass lesion in the left ovary that measured 6.7 × 18.9 × 29.3 cm, and the contrasted scan showed an enhanced septum and solid component (Fig. 1). The liver and intrahepatic ducts, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, both kidneys and ureters were unremarkable. The patient’s pre-operative serum levels showed that carbohydrate antigen (CA-125): 22.3 U/mL (normal: < 35 U/mL), human epididymal protein-4 (HE4): 28.5 pmol/L (normal: < 70 pmoI/L), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG): < 1.20 mIU/ml (normal: < 5.0 mIU/ml), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): 3.3 ng/ml (normal: 0–7 ng/ml), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 2.2 ng/ml (normal: 0–5 ng/ml), carbohydrate antigen 19 − 9 (CA19-9): < 2.0 U/mL (normal: 0–43 U/mL) were within normal limits. The patient, with a height of 155 cm and weight of 45.5 kg (BMI: 18.9), presented no particular concerns regarding nutritional status, general vital signs, psychosocial state, or risk factors for stress-related injuries. The results of complete hemogram ( WBC: 7.5 × 109/L, RBC: 4.2 × 1012/L, PLT: 216 × 109/L, HGB: 127 g/L, et al. ) in addition to liver and kidney function tests ( TBIL:10.5 μm/L, DBIL: 3.4 μm/L, IBIL: 7.1 μm/L, ALB: 45 g/L, GLO: 20 g/L, A/G: 2.3, ALT: 13 U/L, AST: 20 U/L, UREA: 3.25 mmol/L, Cr: 56 umol/L, UA: 323 umol/L, et al. ) and coagulation profile ( APTT: 27.9 s, PT: 12 s, INR: 1.01, TT: 18 s, FIB: 2.7 g/L, FDP: <2 mg/L, D-D: 0.31 mg/L FEU ) were also normal.

Fig. 1.

(a) Pelvic color Doppler ultrasound scan revealed a large mass, predominantly cystic, with poor internal echogenicity. It presented as fine, weakly echogenic spots, with numerous unevenly sized septations (green arrow), and several differently sized solid echogenic protrusions into the cystic cavity (red arrow), giving a cauliflower-like appearance. (b) MRI images revealed a large cystic-solid mass, predominantly cystic, with visible septations (red arrow) and wall nodules (green arrow) within

After examination, given the patient’s pediatric status and the aim to minimize surgical invasiveness, the patient underwent laparoscopic adnexectomy (single-port surgery) which revealed a large left ovarian tumor measuring 29 × 25 × 15 cm with an intact capsule adhering to the omentum; however, the surrounding peritoneum and the right ovary appeared to be uneventful. A small amount of ascites was found in the abdominal cavity and the peritoneal lavage was sent for cytological examination. A left salpingo-oophorectomy was performed followed by frozen tissue sectioning. Subsequently, the patient underwent appendectomy and omentectomy, and the specimens were sent for routine histopathological examination. As no abnormalities were observed in the right ovary during the laparoscopic exploration, and in an effort to minimize surgical impact on the right ovarian function, we did not remove any part of the right ovary for pathological examination.

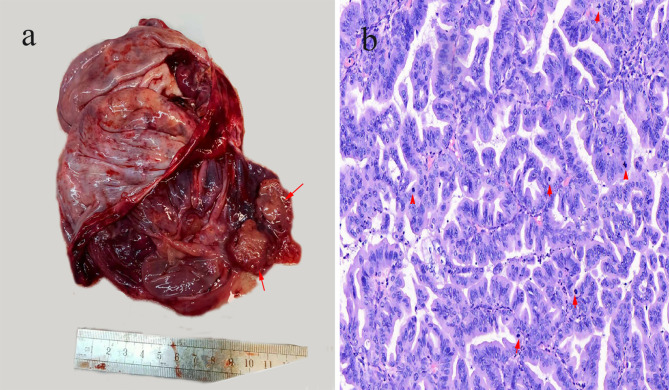

Frozen sections revealed an enlarged dissected ovary measuring 15 × 9 × 4 cm, with a cystic cut section and presence of solid areas. Cysts were filled with turbid mucus, and their walls were mostly smooth with a few surface irregularities and a 3 × 2.5 × 1.5 cm pink nodular excrescence in the interior (Fig. 2a). No significant abnormalities were found in the fallopian tubes.

Fig. 2.

(a) Gross examination: The ovarian mass measured 15 × 9 × 4 cm, with a predominantly cystic appearance upon sectioning. The cysts were filled with turbid mucus, and their walls were largely smooth, with occasional surface irregularities and a pink nodular excrescence visible internally (red arrow). (b) Microscopic examination: The glands, exhibiting papillary and cribriform shapes, showed expansile growth with anastomosing architecture and minimal to absent stroma. The lining of most epithelial cells displayed moderate to severe atypia, with diminished or absent mucinous differentiation and conspicuous mitotic figures (red arrow) (H&E, x400)

Microscopically, frozen sectioning followed by routine histological examination revealed a continuum of architectural and cytological atypia that included benign, borderline, and carcinomatous areas. Carcinomas with papillary and cribriform-shaped glands exhibited expansile growth, with anastomosing architecture and minimal or absent stroma; most of the epithelial cells were moderate to severely atypical in their lining, with reduced/absent mucinous differentiation and conspicuous mitoses. Based on these observations on the tissue pathological aspects, a diagnosis of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma with expansile invasion was finally made (Fig. 2b). The immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: ER-negative, PR-negative, CK7-diffuse positive, CK20-focal positive, CDX2-negative, SATB2-negative, GATA3-negative, Mammaglobin-negative:, GCDFP-15-negative, Pax8-negative, Vimentin-negative, Ki67: about 20% (+), WTI-negative, P53: wild-type expression.

For this patient, the levels of tumor markers, such as carbohydrate antigen (CA-125), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19 − 9 (CA19-9) and human epididymal protein-4 (HE4) were all within normal limits. The diagnosis of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma with expansile invasion was mainly based on imaging and pathology, especially pathology.

The patient was followed up after surgery every three months with gynecologic ultrasound and analysis of tumor markers (CEA, AFP, CA19-9, CA-125, HE4). Ultrasound results showed no pelvic mass and tumor markers were within normal range. Her current menstrual cycle is about 15 days, with an average period of 3–4 days, low volume, and no dysmenorrhea. The patient has so far shown no signs of recurrence and is still being followed up.

Discussion

Here we reported a case of ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma in a 14-year-old girl, which to our knowledge is the first case of ovarian epithelial tumor reported so far in Chinese and East Asian children. Of the eight cases of mucinous adenocarcinoma that have been previously reported in the literature worldwide, seven were from Europe or the United States, and one was from India. Some studies have suggested that ovarian cancer incidence may be related to race and ethnicity, with rates among white adolescents and young adults almost twice as high as those among black women of the same age group [12]. The question of whether racial and ethnic differences are also associated with the incidence of ovarian epithelial tumors in children has been so far unanswered, partly because of the few reported cases. Thus, continued attention and further research are needed in this regard.

In previous reports on mucinous carcinoma of the ovary in children under 15 years of age, the clinical and pathological features of the patients showed that most of the patients had abdominal pain and distention as their first symptoms; elevated serum tumor marker CA125 was reported in two cases, and mildly elevated HCG was reported in one case. None of these reports had follow-up of the patients’ postoperative menstrual status. In the present case, the patient did not have abdominal pain and distension, but presented with a small amount of bloody vaginal discharge. Through follow-up interviews, we know that her current menstrual cycle is about 15 days, with an average period of 3–4 days, low volume, and no dysmenorrhea.

Epithelial tumors of the ovary are very common in women, and most commonly occur during adulthood. Of note, the types of ovarian tumors occurring in children before the age of 15 differ from those diagnosed in adults, with a majority of sex cord-stromal and germ cell tumors, and less than 20% of epithelial tumors. In this line, Van et al. [13] reported ovarian masses in infancy, childhood and adolescence, with the incidence of epithelial and germ cell tumors being 15% and 70%, respectively in the under-15 age group, and 41% and 43% in the over-15 age group. Similar findings were obtained by Young et al. [12] and Li et al. [14].

Concerning ovarian cancer pathogenesis, the traditional view is that all ovarian cancer subtypes originate at the surface epithelium of the ovary. During ovulation, damage to the ovarian surface is caused by the follicle rupture and consequent oocyte release, and during damage repair, the epithelial cells on the ovarian surface become invaginated and form cortical cysts. Exposure of epithelial cells lining the cortical cyst to a new hormone-rich environment induces their proliferation, and eventually some epithelial cells that happen to harbor remaining DNA damage may become carcinogenic, thus leading to ovarian cancer [15]. This rationale explains those ovarian epithelial malignant tumors occurring after menarche but not the cases that occur before it. Consistently, the characteristics of ovarian epithelial tumors are different between children and adults, with serous tumors being the most common in adults while mucinous tumors are the most common in children. It has been suggested that some of the mucinous tumors in the age group of 10–14 may originate from monoblastic differentiation of the gastrointestinal mucinous epithelium in teratomas [16]. This is the age at which germ cell tumors are prone to occur, which may explain why a proportion of mucinous tumors occur before menarche.

The main mode of presentation of ovarian epithelial tumors was abdominal pain, bloating or menstrual disturbances with vague symptoms that were initially ignored. The girl reported in this case presented with a small amount of bloody vaginal discharge, which opportunely caught her attention. Notably, approximately 21% of patients with ovarian epithelial tumors are asymptomatic [14], which frequently leads to disease progression before the lesion is diagnosed.

Both analysis of tumor markers as well as radiological studies are important tools in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer [17]. CA 125 has been widely used as a marker for epithelial ovarian tumors, however, its positive predictive value is debatable. Although serum CA 125 levels (> 35 U/mL) are elevated in more than 80% of patients with ovarian epithelial carcinoma, they are also elevated in approximately 1% of non-neoplastic conditions such as endometriosis, cirrhosis, pancreatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and advanced abdominal -non-ovarian- malignancies [18]. Furthermore, serum CA 125 has been reported to have only 78.1% sensitivity and 76.8% specificity in detecting primary ovarian epithelial carcinoma [19]. In spite of this, it remains a useful tumor marker to be used in combination with imaging findings, which often show an adnexal mass in the presence of a tumor.

Frailty, characterized by increased vulnerability and reduced health response, plays an important role in predicting postoperative complications and survival outcomes in gynecological oncology. This assessment, which correlates with prolonged hospital stay and increased risk of organ failure, mortality, and rehospitalization, should be performed using standard scores such as the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS-7) and Frailty Index (FI), [20]. This enables personalized therapeutic strategies for patients with gynecological malignancies, thereby improving oncological outcomes. Although we assessed her body mass index (BMI), nutritional status, general vital signs, psychosocial status, and risk factors for stress-related injury and concluded that she was likely to tolerate surgery with minimal risk of serious complications, we did not use specific frailty measures (e.g., CFS-7, FI) We recognize the importance of these assessments and acknowledge this as an area for future improvement.

Following surgery, the patient developed a low-grade fever, and complete blood count (CBC) indicated an elevated white blood cell count and neutrophil percentage, warranting antibiotic treatment. Postoperative pain was managed with pain management therapy, resulting in only mild discomfort, as indicated by a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score of less than 3. No other postoperative complications were observed.

The prognosis of ovarian cancers presenting at a young age is variable and depends on the tumor stage upon presentation as well as histological type. In the eight reported cases of ovarian mucinous carcinoma in children to date, five were at stage I. Among these, one case was found to have cancerous thrombi in the vessels and died from recurrent metastasis two years later, while the rest achieved a survival time of over five years. The other three cases were at a higher stage: one died a year after diagnosis, and the other two had either metastasis at the time of diagnosis or cancer cells were found in the ascites, suggesting a less favorable prognosis.

Treatment of ovarian epithelial carcinoma in children relies on the experience from treating adult patients, with an emphasis on the preservation of reproductive functions. However, individualized regimens have been developed based on the establishment of comprehensive surgical staging. In patients with low-grade stage IA (serous, endometrioid or mucinous expansile subtype), fertility-sparing surgery (FSS) appears to be a safe option [21–23]. FSS can also be considered for stage IC1 tumors, as recurrences, which are often isolated on the remaining ovary, can typically be managed with subsequent surgery. However, it’s important to note that recurrence rates tend to be higher in stage IC2, IC3, and grade 3 diseases, mainly in extra-ovarian sites. This suggests that these recurrences may not be directly associated with the fertility-sparing approach. Therefore, comprehensive counseling is crucial when considering FSS in these situations [24].

Various adjuvant chemotherapy regimens have been used in epithelial carcinoma of the ovary to improve survival. A comprehensive cohort study [25] found that chemotherapy not only reduced mortality for high-risk patients but also for those with stage IA/IB, grade 2 ovarian cancer. This aligns with previous studies showing no advantage of chemotherapy for women with stage IA and IB, grade 1 tumors. In particular, for histological subtypes like mucinous subtype, the expansile or grade I type, which is linked to a better prognosis, is not recommended for adjuvant chemotherapy, while the infiltrative form has a high relapse risk [26–29].

Conclusions

In summary, ovarian epithelial tumors are very rare in children, and their pathogenesis, especially before menarche, remains unclear, which poses a challenge to the treatment and management of the disease. In this context, the present case report adds valuable information concerning the clinical, serological and imaging characteristics of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, a rare type of epithelial ovarian cancer, in a young patient. Given the scarcity of reports addressing the clinical management of this condition, the present study provides a useful contribution to its further understanding in light of developing future treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

YTJ conceived the present study. XYY, LSQ and YTJ acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data. LQ and ZCC wrote the manuscript. YTJ critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

For case studies based on available clinical data, no approval by the Medical Ethics Committee of Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children is required.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her parents for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gupta B, Orcid Id, Arora P, Khurana N, Tempe A. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of ovary with metastasis in 14-year-old girl. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60:227–31. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biçer S, Erkul Z, Demiryilmaz I, Peker N. A 9-kg ovarian mucinous cystadenoma in a 14-year-old premenarchal girl. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:326–9. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.890862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karaman A, Azili MN, Boduroğlu EC, Karaman I, Erdoğan D, Cavuşoğlu YH, et al. A huge ovarian mucinous cystadenoma in a 14-year-old premenarchal girl: review on. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21:41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong SJ, Lurain JR, Tsukada Y, Piver MS, Humbert JR, Freeman AI. Cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary in a 4-year-old: benign transformation during. Cancer. 1980;45:2227–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800415)45:8<2227::AID-CNCR2820450837>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blom GP, Torkildsen EM. Ovarian cystadenocarcinoma in a 4-year-old girl: report of a case and review of. Gynecol Oncol. 1982;13:242–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(82)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez E, Rosenshein NB, Parmley TH. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma in a premenarchal girl. South Med J. 1982;75:1265–7. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198210000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gribbon M, Ein SH, Mancer K. Pediatric malignant ovarian tumors: a 43-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:480–4. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skinner MA, Schlatter MG, Heifetz SA, Grosfeld JL. Ovarian neoplasms in children. Arch Surg. 1993;128:849–53. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shankar KR, Wakhlu A, Kokai GK, McDowell H, Jones MO. Ovarian adenocarcinoma in premenarchal girls. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:511–5. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.21617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morowitz M, Huff D, von Allmen D. Epithelial ovarian tumors in children: a retrospective analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:331–5. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drosdzol-Cop A, Mizia-Malarz A, Wilk K, Koszutski T, Wilk K, Stojko R. Ovarian adenocarcinoma in 14-year-old girl. Ginekol Pol. 2022;14:10. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2022.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young JL, Cheng Wu X, Roffers SD, Howe HL, Correa C, Weinstein R. Ovarian cancer in children and young adults in the United States, 1992–1997. Cancer. 2003;97 Suppl:2694 – 700. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Van Winter JT, Simmons PS, Podratz KC. Surgically treated adnexal masses in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1780–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(94)70354-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Pan LY, Huang HF, Lang JH. Epithelial ovarian tumors in adolescence: a study of clinical features and. Zhonghua fu chan ke za zhi. 2004;39:598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong AS, Leung PC. Role of endocrine and growth factors on the ovarian surface epithelium. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris HB, La Vecchia C, Draper GJ. Malignant epithelial tumors of the ovary in childhood: a clinicopathological. Gynecol Oncol. 1984;19:290–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(84)90195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deprest J, Moerman P, Corneillie P, Ide P. Ovarian borderline mucinous tumor in a premenarchal girl: review on ovarian. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;45:219–24. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90290-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanaboni F, Vergadoro F, Presti M, Gallotti P, Lombardi F, Bolis G. Tumor antigen CA 125 as a marker of ovarian epithelial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1987;28:61–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-8258(87)80009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leake J, Woolas RP, Daniel J, Oram DH, Brown CL. Immunocytochemical and serological expression of CA 125: a clinicopathological. Histopathology. 1994;24:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottavia, Dʼoria et al. Tullio Golia D’Augè,. The role of preoperative frailty assessment in patients affected by gynecological cancer: a narrative review. Ital J Gynaecol Obstet 2022, 34, N.2.

- 21.Bentivegna E, Gouy S, Maulard A, et al. Fertility-sparing surgery in epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review of oncological issues. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1994–2004. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh T, Hatae M, Watanabe Y, et al. Outcomes of fertility-sparing surgery for stage I epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposal for patient selection. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1727–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fruscio R, Corso S, Ceppi L, et al. Conservative management of early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: results of a large retrospective series. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:138–44. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentivegna E, Fruscio R, Roussin S, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with an isolated ovarian recurrence after conservative treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer: review of the results of an international multicenter study comprising 545 patients. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1319–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee S, Chen L, Tergas AI, et al. Utilization and outcomes of chemotherapy in women with intermediate-risk, early-stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:992–1002. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee KR, Scully RE. Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 196 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas, including an evaluation of 11 cases with ‘pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1447–64. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gouy S, Saidani M, Maulard A, et al. Staging surgery in early-stage ovarian mucinous tumors according to expansile and infiltrative types. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;22:21–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muyldermans K, Moerman P, Amant F, et al. Primary invasive mucinous ovarian carcinoma of the intestinal type: importance of the expansile versus infiltrative type in predicting recurrence and lymph node metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1600–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prat J, De Nictolis M. Serous borderline tumors of the ovary: a long-term follow-up study of 137 cases, including 18 with a micropapillary pattern and 20 with microinvasion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1111–28. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.