Abstract

Tick-borne bacterium Rickettsia parkeri is an obligate intracellular pathogen that belongs to spotted fever group rickettsia (SFGR). The SFG pathogens are characterized by their ability to infect and rapidly proliferate inside host vascular endothelial cells that eventually result in impairment of vascular endothelium barrier functions. Benidipine, a wide range dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, is used to prevent and treat cardiovascular diseases. In this study, we tested whether benidipine has protective effects against rickettsia-induced microvascular endothelial cell barrier dysfunction in vitro. We utilized an in vitro vascular model consisting of transformed human brain microvascular endothelial cells (tHBMECs) and continuously monitored transendothelial electric resistance (TEER) across the cell monolayer. We found that during the late stages of infection when we observed TEER decrease and when there was a gradual increase of the cytoplasmic [Ca2+], benidipine prevented these rickettsia-induced effects. In contrast, nifedipine, another cardiovascular dihydropyridine channel blocker specific for L-type Ca2+ channels, did not prevent R. parkeri-induced drop of TEER. Additionally, neither drug was bactericidal. These data suggest that growth of R. parkeri inside endothelial cells is associated with impairment of endothelial cell monolayer integrity due to Ca2+ flooding through specific, benidipine-sensitive T- or N/Q-type Ca2+ channels but not through nifedipine-sensitive L-type Ca2+ channels. Further study will be required to discern the exact nature of the Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ transporting system(s) involved, any contributions of the pathogen toward this process, as well as the suitability of benidipine and new dihydropyridine derivatives as complimentary therapeutic drugs against Rickettsia-induced vascular failure.

Keywords: Vascular permeability, Spotted fever Rickettsia, Benidipine, Nifedipine, Brain microvascular endothelium, Electric cell impedance sensing, Calcium channel blockers

1. INTRODUCTION

Spotted fever group Rickettsia (SFGR) obligate intracellular bacteria are generally maintained by transmission between two distinct hosts, ticks and non-arthropod animals, chiefly mammals. With disease in mammals, including humans, SFGR preferentially infect vascular endothelium leading to vasculitis and changes in vascular permeability [1–3]. Disseminated infection and systemic vascular permeability can lead to severe complications, including septic shock, multi-organ failure, or death, as observed with Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), and other forms of spotted fever rickettsiosis [4]. The antibiotic doxycycline is a highly effective treatment, when implemented early in infection. Yet, despite the availability of anti-rickettsial therapeutics, the global increases in SFGR show a continued occurrence of case fatality rates exceeding 10% in areas such as Mexico, Brazil, Columbia, and even some geographic regions in the U.S. [5–8].

It is widely believed that the pathogen’s rapid proliferation in the endothelial cell cytoplasm and their quick spread to neighboring cells is responsible for massive infection and accompanying vascular barrier failure [1,2]. Although dose-dependent, systemic vascular barrier failure and fatality in humans with RMSF often occurs with relatively low endothelial cell infection burdens, raising questions about its mechanism [9–14]. Prior in vitro investigations showed rickettsia dose-dependent barrier dysfunction but concluded that much of this was the result of actions of inflammatory vasoactive cytokines elicited by the infection [15,16]. Given the absolute dependence of vascular endothelium function on Ca2+ signaling, barrier failure is often related to the inability to maintain Ca2+ balance inside the endothelial cells [17–21].

In studies to examine the ability of pathogenic microbes to pass through in vitro human brain microvascular barriers, we previously showed that the observed pathogen-induced barrier dysfunction can be antagonized by pharmacologic agents that target key calcium signaling pathways, block calcium flux, or chelate divalent cations [16,22–26]. One such drug identified in our screens was benidipine, a wide range voltage-activated Ca2+ channel blocker (CCB) that belongs to dihydropyridine family of cardiovascular drugs [4,26–31]. Benidipine prevents cell infection by Dabie bandavirus, the tick-borne Bandavirus that causes severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) in humans [32]. A similar protective effect was observed with nifedipine, an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker; however, the effect of these drugs on vascular permeability was not studied [32].

In this study, we systematically examined whether benidipine compared to nifedipine protects against rickettsia infection-induced endothelial cell monolayer dysfunction. Here, we used R. parkeri which causes a mild to moderate disease in humans, is a BSL2 surrogate for BSL3 highly pathogenic SFGR, and provides outstanding models of human disease and in vitro cellular microbiology [33–35]. We utilized an established in vitro model of the human blood-brain barrier using Electric Cell Impedance Sensing (ECIS) that continuously monitors changes in permeability across the endothelial cell monolayer with R. parkeri infection and during treatment with drugs of interest [15,22,23,25,36]. The results implicate a role for specific, benidipine-sensitive Ca2+ channels, likely low voltage-activated T- or N-/Q-type Ca2+ channels in maintaining barrier integrity, and provide impetus for further detailed investigations of the pharmacologic mechanisms of action of these drugs to identify strategies to protect against vascular failure during rickettsial infection and perhaps other infectious diseases associated with an increased vascular permeability [21].

2. MATERIALS and METHODS

2.1. Reagents:

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) benidipine HCl and nifedipine were purchased from Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK.

2.2. Cell cultures and bacterial growth.

R. parkeri (Rp) Portsmouth strain was maintained, as described with modifications, in transformed human brain microvascular endothelial cells (tHBMEC) cultured in M199 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine and 1 mM pyruvate [37,38].

2.3. Bacterial infectivity

To evaluate the infectivity of pathogens we used Diff-Quik staining, a variant of Romanowsky stain, as previously described [39].

2.4. Immunofluorescence staining

To visualize the effect of R. parkeri infection on tight junctions of the tHBMECs, 6–7 × 104 cells were seeded on collagen-coated 8-well optical glass slides (LabTek) in 400 μL of M199 growth medium. After 24h, confluent tHBMECs monolayers were treated with 2.5–4.0 × 103 R. parkeri-infected or non-infected tHBMECs. After overnight incubation, the medium was replaced to remove unattached and dead cells. After 24–48 hours of incubation, infected and control cells were washed with warm PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. The fixed tHBMECs were washed with PBS and permeabilized with 100 μM digitonin (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 10 min. Then, the permeabilized cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with mouse anti-human Alexa-488-ZO-1 antibody (Invitrogen) at 1:100 dilution. After washing with PBS, the chamber walls were removed and slides were mounted (Prolong Diamond Antifade Mounting Solution, Invitrogen) and visualized using fluorescence microscopy.

2.5. The effects of drugs on tHBMEC viability and bacterial growth.

For the analysis of tHBMEC viability in the presence of Ca2+ channel blockers, we used the CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 kit (Promega) that determines viability by quantitating intracellular ATP, an indicator of metabolically active cells. tHBMECs were seeded in dark-wall 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-one, Frickenhausen, Germany), at 3 × 104 cells per well and after 24 hours of growth confluent cells were treated with various concentrations of the Ca2+ channel blockers. After 48h, the cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, the luminescence readings were obtained using a PerkinElmer Victor3 1420 Multilabel Counter. The standard ATP (Sigma) curve was created; each plate included control wells with untreated cells for measuring optimal viability, and wells with medium M199 only for the background readings.

2.6. Preparation and quantification of isolated R. parkeri.

Before bacterial isolation, the supernatant culture medium of the R. parkeri-infected tHBMECs was collected and stored on ice while the remaining attached cells in the flasks were briefly treated with 0.25% Trypsin (Gibco). After 2–4 minute incubation at 37°C, a solution with detached cells was collected, combined with the previously collected supernatant and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded while the sediment was diluted in cold PBS for sonication. Sonication of the tHBMEC/bacteria mixture was performed for 10 sec in Branson Sonifier 250 (from VWR Scientific), at 20% power output and 70% duty cycle. After sonication, the solution was briefly centrifuged at 500g for 3 min to remove large cell remnants, and the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min. The supernatant was then discarded, and the bacteria-containing sediment was diluted in a small volume (200 μL) of PBS. A small aliquot of the bacterial suspension was used for assessment of cell-free bacteria and their direct counting by using fluorescent membrane labelling (PKH26, Sigma). Direct counting of labeled R. parkeri was performed using Glasstic slides (Kova, Garden Grove, CA) on a widefield fluorescent Olympus BX40 microscope equipped with a cooled Olympus DP74 camera, 10x, 40x, 100x objectives, and a 3D-precision stage for electronic- and manual operation (ProScan III from Prior Sci Intl, Fulbourn, GB). The number of R. parkeri counted was used to estimate the MOI for some ECIS experiments and for calibration of bacterial DNA for qPCR analysis.

2.7. Replication of R. parkeri exposed to Ca2+ blockers.

In addition to direct counting of bacteria, we also used qPCR to quantitate bacterial DNA copies per 105 tHBMECs after 24–48h of drug exposure. After drug treatment, R. parkeri were collected as described above and used for DNA preparation and quantification by qPCR.

2.8. High throughput purification of bacterial DNA from tHBMEC.

We utilized a protocol for preparation of gram-negative bacterial lysates by PureLink™ Pro96 Genomic DNA Kit and the EveryPrep™ Universal Vacuum Manifold method for DNA capturing and purified DNA elution from Invitrogen. The primers used in the 5’-Nuclease assay were as previously described: Rickettsia spotted group fever and single genome copy target gene sca0 (ompA) forward TTGTCAGGCTCTGAAGCTAAAC and reverse AGCACCTGCCGTTGTGATATC with a fluorescent probe FAM-TAGCCGCAGTCCCTACAACACCGC [40]. Quantification was achieved by concurrent assay of diluted plasmids containing SFGR sca0 over the range of 100 to 107 copies, or using DNA from microscopically-quantified R. parkeri suspension as standards, as described above.

2.9. Electric Cell Impedance Sensing system (ECIS) to monitor microvascular barrier integrity.

To evaluate the effects of Ca2+ channel blockers and R. parkeri infection on integrity of the model microvascular barrier, we utilized ECIS and 96-well electrode arrays from Applied Biophysics [27]. Collagen-coated gold-electrode arrays (96W10idf) were seeded with tHBMECs at 3 × 104 cells per well. After confluent at 24h, the cells were pretreated for 30–60 min with various concentrations of benidipine, nifedipine or vehicle only, and then the cell monolayers were treated with a cell-free R. parkeri at MOIs of 10–30 or with 2,500–4,000 R. parkeri-infected tHBMECs at 60–80% viability. Dynamic changes in tHBMEC monolayer transendothelial electrical resistivities (TEER) were continuously monitored over next 48–72h. The absence of significant TEER changes (<10% of initial readings) at the end of the experiments supplemented with the calcium channel blockers only, compared to growth medium only-treated controls was considered as evidence for the absence of any deleterious effects of the drugs on monolayer integrity.

2.10. Measuring the rate of Ca2+ inflow in R. parkeri-infected and control cells.

tHBMECs were seeded into 96-well flat-bottom plates (Costar) at 3×104 per well. After stabilization, the cells were infected with R. parkeri at an MOI 100 (quantified by qPCR), or sham-infected, and then incubated in the presence or absence of 10 μM benidipine; ATP was used as control. At 24h incubation, the cells were loaded with Fluo-4 (using the Invitrogen Fluo-4 NW calcium Assay kit as per manufacturer’s recommendations), a cell permeant, non-washable intracellular Ca2+ sensor, for 30 minutes at 37°C. The plates were then transferred to a prewarmed (37°C) fluorescent plate reader and kinetic changes of the [Ca2+]i were obtained continuously over the next 100 min. For analysis, fluorescent intensity data were normalized to the no benidipine sham-infected wells.

2.11. Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM or mean ± SD as noted. Statistics were performed with a Student’s two-tailed t-test of unpaired samples. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

Based on a pilot screening study that examined cellular and microbial toxicity of the drugs as well as changes of TEER during rickettsial exposure, we selected two modulators of cellular Ca2+ signaling, benidipine and nifedipine that are known for their protective effects against various cardiovascular diseases, especially hypertension [4,26,27,41,42]. Both compounds belong to dihydropyridine class of drugs. These two drugs control cellular Ca2+ metabolism by interfering with Ca2+ flux through voltage-activated calcium channels across the plasma membrane [4,43]. Nifedipine blocks Ca2+ fluxes through L-type calcium channels [29], while benidipine has a broader range and concentration-dependent blocking effects on L,-T-, and N/Q-type calcium channels [28,42,44].

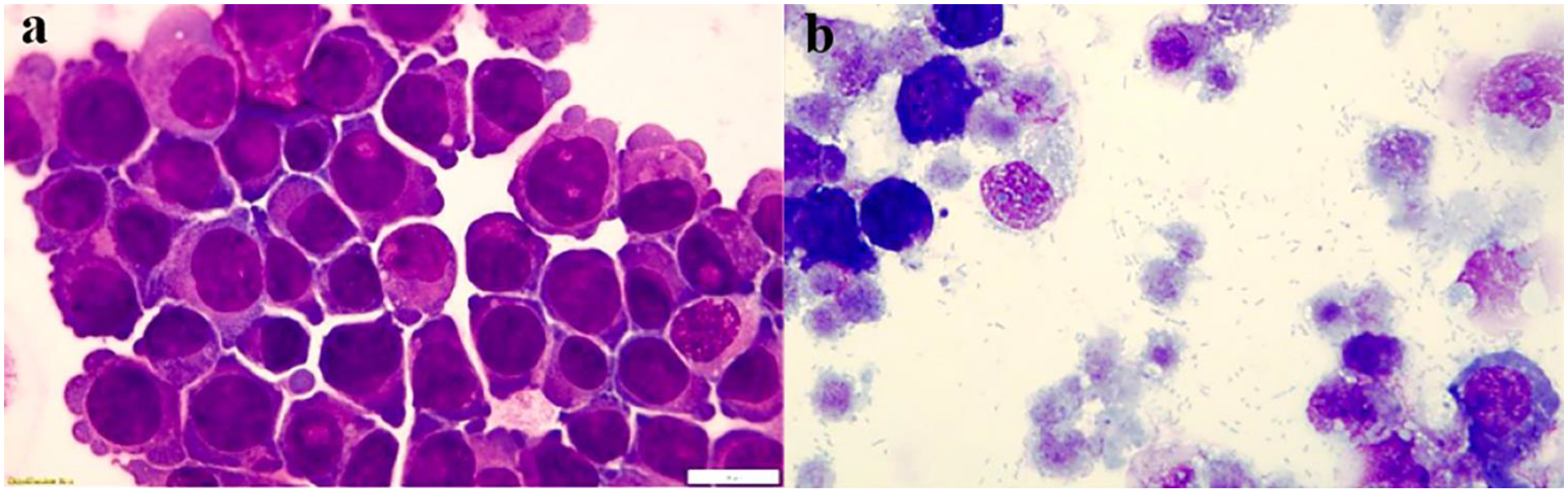

As Fig. 1 shows, massive growth of R. parkeri results in eventual disintegration of endothelial cells. Initially, we evaluated whether Ca2+ blockers exert a cytotoxic effect on tHBMECs by measuring intracellular ATP since viability is directly related to higher levels in viable vs. dead cells. As Fig. 2 shows, except at 100 μM concentrations, the compounds had little or no cytotoxic effect on tHBMECs compared to untreated cells. For detailed studies we selected non-toxic 1 and 10 μM concentrations.

Figure 1.

R. parkeri-infect tHBMECs and ultimately result in cell disintegration and massive bacteria release. Confluent tHBMECs were trypsin-treated and examined either before R. parkeri infection (a) or 48–72h post infection (b). (Diff-Quik stain). Bar = 10 μm. Panels a and b were digitally and equally optimized for brightness and contrast.

Figure 2.

Toxicity of benidipine and nifedipine on tHBMECs. tHBMECs were grown to confluency in 96-flat bottom plates and then treated with the indicated concentrations of benidipine and nifedipine. After 48h of treatment, the cells were collected and ATP luminescence of the cells was measured according to CellGlo2 protocol (see Materials and Methods section). Data are mean ± SEM, n=6.

To evaluate whether benidipine and nifedipine had direct bactericidal effects, we assessed their action on R. parkeri growth. Infected cells were grown in the continuous presence of the different concentrations of Ca2+ channel blockers. With a R. parkeri inoculum of MOI 20, by 48h rickettsial numbers expanded rapidly to approximately 200–300 per cell, and neither benidipine nor nifedipine, in the doses shown here, had an ultimately significant effect on bacterial growth (Fig. 3), although variation in the kinetics of bacterial growth were noted among experiments using differing MOIs, inoculation methods, and potentially other host factors. In addition, neither nifedipine nor benidipine showed adverse effects on cell monolayer stability over a wide range of concentrations.

Figure 3.

Effect of benidipine (Ben) and nefidipine (Nif) on toxicity to R. parkeri (Rp) growth. Confluent tHBMECs were exposed to R. parkeri at approximate MOIs of 10–20 in 96 well flat bottom plates, and after 48h bacterial DNA was isolated as described in Materials and Methods and measured by qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of 2 measurements in triplicate.

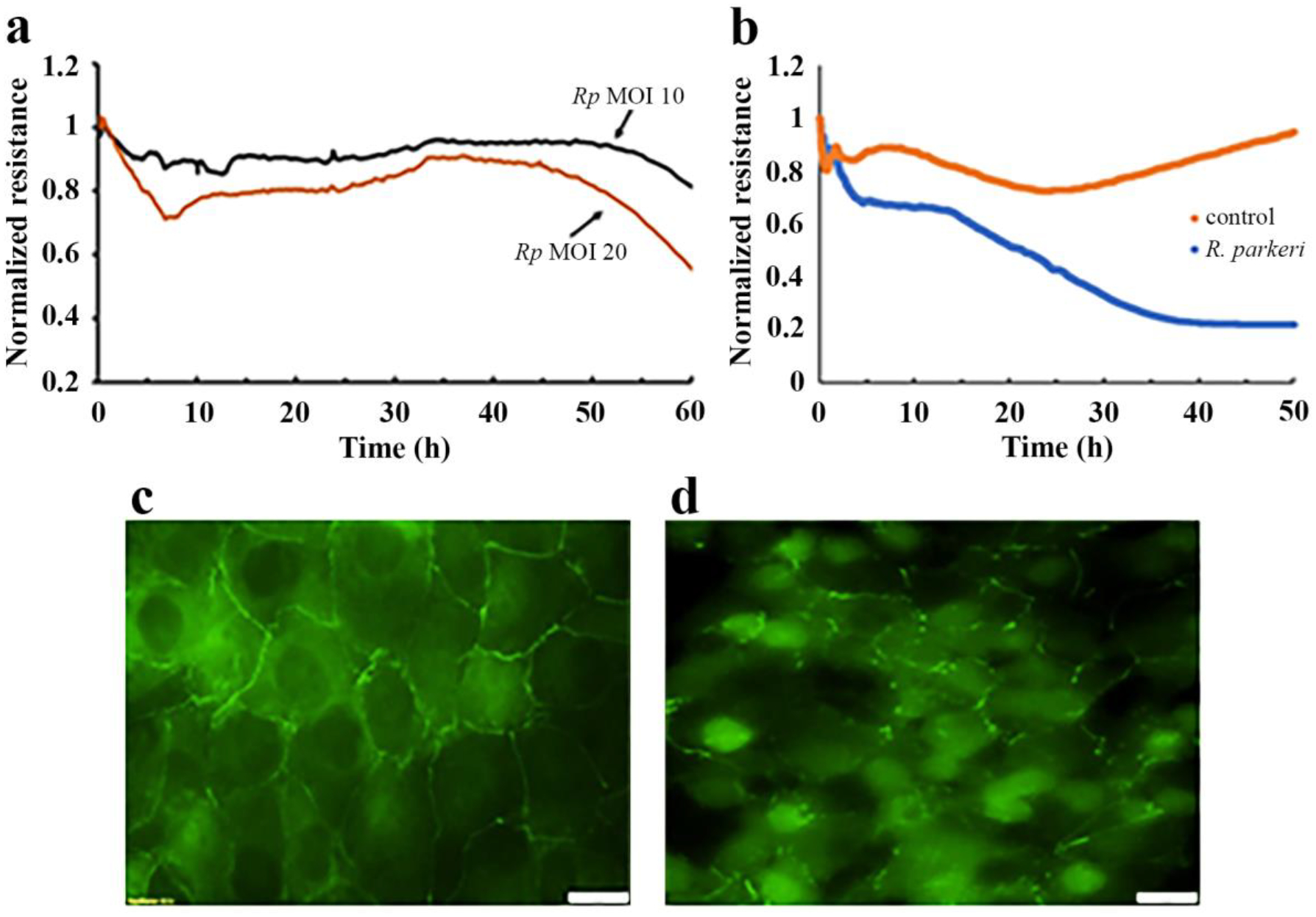

R. parkeri, delivered as either free bacteria or as infected tHBMECs caused the cell monolayer resistance to drop significantly (Fig.4 A, B), especially at higher MOIs (Figs 4A). Additionally, this led to disassembly of the tight junctions between the cells as visualized by diminished membrane expression of the fluorescently labeled ZO-1 proteins (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Representative ECIS traces demonstrating the loss of tHBMEC endothelial cell monolayer integrity after inoculation with cell-free R. parkeri (a) and with R. parkeri-infected tHBMECs (b, d), and without R. parkeri (b, c). In (a), free bacteria were isolated as described in Methods section and then were added at MOI=10 or at MOI=20 at 0h. In (b) the tHBMEC monolayers were treated with 3×103 R. parkeri-infected or uninfected (control) tHBMECs at 0h. Panel (d) shows disruption of tight junctions between tHBMECs by R. parkeri-infected tHBMECs visualized with mouse anti-human ZO-1 antibody after 48 hours of infection. Panel (c) shows ZO-staining of control cells. Scale bar −20 μM. Panels c and d were digitally and equally optimized for brightness and contrast.

We then tested whether benidipine and/or nifedipine could also exert protective effects against rickettsia-induced microvascular endothelial cell monolayer dysfunction. Figure 5 shows that benidipine has a strong protective effect against R. parkeri-induced reduction of electrical resistance across cell monolayers, even after ≥ 60 hours post infection. The protective effect of benidipine was concentration-dependent with the most effective concentrations at 1 and 10 μM (Fig. 5A). Importantly, we observed that in contrast to benidipine, the L-type calcium channel blocker nifedipine did not prevent rickettsia-induced decrease of tHBMEC barrier TEER.

Figure 5.

Benidipine prevents R. parkeri-induced disruption of endothelial cell monolayer integrity (A, B, C) and an increase in cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i (D, E) in tHBMECs. (A) Real-time traces of the concentration-dependent prevention by benidipine of the TEER drop across the microvascular monolayers induced by R. parkeri-infected tHBMECs. 96-well gold-electrode ECIS microarrays with stable tHBMEC monolayers were pretreated for 1 hour with 0.01–10 μM benidipine (RpTHB+Ben 0.01/0.1/1&10), M199 growth media only (M199), or 1 or 10 μM nifedipine (RpTHB+Nif 1&10) before addition of 2.4 × 103 R. parkeri-infected (RpTHB) or uninfected control tHBMECs (THB). Vertical lines along the traces show S.E.M. of the corresponding ECIS traces. Higher MOIs of R. parkeri more rapidly disrupted monolayer integrity compared to a modestly lower R. parkeri MOI (1.6 × 103 infected tHBMECs, [1.6K RpTHB]). A benidipine dose-dependent delay in TEER reduction was observed. (B and C) show TEER of tHBMEC monolayers induced by R. parkeri in the presence and absence of the Ca2+ channel blockers. Cell monolayers in 8-well gold-electrode ECIS arrays were pretreated for 1 hour with (a) 10 μM benidipine, (c) M199 growth media or (d) 10 μM nifedipine before addition of 3.0 × 103 infected (a, d, e) or uninfected control tHBMECs (b). (C) Analysis of protective effects of benidipine against R. parkeri-induced disruption of tHBMEC monolayer integrity. For comparative statistical analysis the data were selected at 12 and 24h after the cell additions (arrows in B). Data are means ± SD, n=3. ***p< 0.001 for benidipine treatments against Rp-infected cells. (D) Representative traces of the intracellular [Ca2+]i changes in Rp-infected tHBMECs, treated or non-treated with 10 μM benidipine. For comparative statistical analysis the kinetic data were selected at 50 min (white arrow on D), and shown in 6E. In 6E, 10 μM ATP was also used as a positive control to induce intracellular [Ca2+]i rise. Data are means ± SEM, n=4, **p<0.01.

Benidipine also showed a suppressive effect on [Ca2+]i increase in R. parkeri-infected tHBMECs (Fig.5 D, E) suggesting that increased Ca2+ inflow through benidipine-sensitive Ca2+ channels is likely responsible for the endothelial cell monolayer dysfunction. Additionally, the impact of benidipine on the kinetics of microbial propagation and cell-cell spread, possibly through regulation of calcium flux, should be considered since expanded bacterial populations lead to cellular stress [45,46]. The contrasting difference between the two calcium channel blockers tested implies the early involvement of a specific, benidipine-sensitive T- or N/Q-type calcium channel in rickettsia-induced vascular failure and prompting the need for further investigations that could identify specific agents that are able to target these channels in endothelial cells as a potential adjunctive therapeutic against vascular failure during infection.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Tick-borne intracellular bacterial pathogens of the spotted fever group Rickettsia predominantly invade vascular endothelial cells [1,2,13,14,47]. These bacteria rapidly proliferate inside cells, and if uncontrolled, their number can reach up to >1000 per cell. In vitro, this ultimately results in endothelial cell monolayer disruption [48]; in vivo, this can result in dramatic increases in local or systemic vascular permeability [1]. Treatment of spotted fever rickettsiosis is largely confined to the use of the antibiotic doxycycline, yet serious complications and fatal outcomes continue to occur once irreversible vascular and tissue injury is established [1]. Since increased vascular permeability is the key pathophysiologic event in vasculotropic rickettsioses, including spotted fever, alternative approaches that target host cell dysfunction so as to stabilize or reverse increased vascular permeability could be beneficial adjunctive treatments.

Cellular calcium signaling system plays a central and critical role in regulating vascular endothelial cell functions [17,18,20,42,49]. Uncontrolled rise of the intracellular [Ca2+]i results in an increase of transendothelial permeability and eventual disintegration of the endothelial cell monolayer. It is likely that rickettsia-induced vascular endothelial cell dysfunction is associated with changes in Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms of the cells. A single publication directly examines the involvement of Ca2+ transport with rickettsial infection where it was shown that treatment of human umbilical cord vascular endothelial cells with Ca2+ ionophore A23187 abrogated entry but not binding of Rickettsia prowazekii [12]. This suggested the importance of a Ca2+ gradient across the cellular membrane for the pathogen entry. In retrospect, current knowledge of the mechanistic basis of rickettsial invasion and internalization through transmembrane signaling is likely dependent on calcium signaling [50].

Depending on their origin, mammalian/animal cells express more than 100 different types of ion channels that are specifically or non-specifically able to transport Ca2+ [43]. In the present study we identify the importance of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in rickettsial infection of endothelial cells, especially at later stages of infection. The exact type and expression levels of Ca2+ channels on endothelial cell plasma membranes are yet to be determined. Benidipine blocks a range of the voltage-sensitive calcium channels activated with a small voltage drop across the plasma membrane, predominantly T-type, and to lesser extent L-, N-/Q-type channels [27,31]. In contrast, nifedipine predominantly blocks L-type calcium channels that are require a large voltage drop across the membrane for activation [4,43,44].

The data here demonstrate that with intracellular growth, especially in the later stages of infection, rickettsiae induce significant Ca2+ influx that can be abrogated temporarily by benidipine. This implies that leakage of Ca2+ probably occurs primarily through benidipine-sensitive channels and further supports the concept that an increased Ca2+ inflow eventually overcomes cellular systems responsible for maintaining Ca2+ balance inside the cells. These intracellular Ca2+ changes ultimately affect the stability of junctional proteins and cytoskeleton to drive the observed decrease of TEER in vitro, and likely influence a wide range of other cellular functions including the production of vasoactive cytokines [17,51]. Of interest is the apparent specificity of this response to rickettsial infection that involves a single class of calcium channels suggesting a possibility of channelopathy or a related acquired condition [52,53].

We considered several hypotheses to facilitate a mechanistic understanding of these observations. First, rickettsiae are known to “parasitize” their host cells by acquiring a range of host products, such as ATP and actin [2,13,35,54], that drive their growth. One hypothesis includes consumption of ATP that would then impair functions of plasma membrane calcium ATPase (PMCA) and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) that remove excess Ca2+ from the cytosol in order to restore homeostatic balance. Another possibility is the increasing production of a rickettsial product, perhaps a secreted effector [1] that either directly or indirectly triggers an existing G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), associated downstream Ca2+ signaling events that lead to an increased Ca2+ influx, or is involved in actin tail assembly [17,50,55]. Regardless of the initiating events, the consequences would naturally also include transcriptional regulatory changes with Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and likely other cytoplasmic transcription factors that alter expression of a range of immune and inflammatory function genes. Their activation in turn could lead to inflammatory cell recruitment, generation of inflammatory mediators and production of vasoactive cytokines that were previously described as critical for TEER changes during R. conorii and R. rickettsii infection [15,36]. A cascade such as this would result in a gradual increase in intracellular Ca2+ that would cause gradual decrease of TEER in vitro, or vascular permeability in vivo. As T-type channels targeted by benidipine are activated with low voltage changes, it could be that this drug abrogates cell junction disassembly and stabilizes TEER first by dampening the influx of Ca2+. As increasing bacterial intracellular burden accumulates and further [Ca2+]i increases, the voltage change could reach the range impacted by high voltage gated channels, such as L-type channels, or other calcium regulatory mechanisms. Identifying functional drugs that specifically target these events in endothelial cells without collateral adverse effects might provide adjunctive support to prevent severe complications and buy time for antimicrobial treatments and waxing immune response to control infection.

Considering that previous study suggests calcium-sensitive invasion mechanism [11], it will be interesting to investigate whether other types of Ca2+ channels are involved during initial stages of rickettsial entry and subsequent proliferation. The finding that one or several different types of Ca2+-dependent transporting systems are involved in rickettsial entry and massive growth inside the endothelial cells could provide further opportunities to develop novel therapeutic tools to treat vascular failure during infection.

Highlights.

The major pathophysiologic event for severe rickettsial diseases such as spotted fever rickettsiosis is systemic increase in vascular permeability at sites of endothelial cell infection.

Vascular permeability at the level of the endothelial cell is largely regulated by changes in intracellular calcium concentrations that regulate signaling for cortical actomysin, cellular tight junctions, and inflammatory gene transcription.

Calcium channel blockers regulate entry of calcium into endothelial cells, and in the case of benidipine, this transiently stabilizes microvascular endothelial cell barriers with intracellular spotted fever rickettsia infection.

The transient stabilization of microvascular endothelial barriers by benidipine corresponds to reduced entry of calcium within the rickettsia-infected cells.

The specific effect that relates to the T- or N/Q-type voltage gated calcium channels blocked by benidipine could be the result of increasing endothelial cell injury, but a role for direct targeting of the channels by rickettsial effectors needs to be examined.

Funding support.

This study was funded by the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program Tick-Borne Diseases Research Program (Grant No. W81XWH-17-1-0668) and the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant no. R21AI171791) to JSD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily representative of those of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), the Department of Defense (DOD); or, the United States Army, Navy, or Air Force.

References

- [1].Sahni A, Fang R, Sahni SK, Walker DH, Pathogenesis of rickettsial diseases: pathogenic and immune mechanisms of an endotheliotropic infection, Annu. Rev. Pathol 14 (2019) 127–152. 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Walker DH, Ismail N, Emerging and re-emerging rickettsioses: endothelial cell infection and early disease events, Nature reviews. Microbiology 6 (2008) 375–386. 10.1038/nrmicro1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gillespie JJ, Kaur SJ, Rahman MS, Rennoll-Bankert K, Sears KT, Beier-Sexton M, Azad AF, Secretome of obligate intracellular Rickettsia, FEMS Microbiol. Rev 39 (2015) 47–80. 10.1111/1574-6976.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zamponi GW, Striessnig J, Koschak A, Dolphin AC, The physiology, pathology, and pharmacology of Vvoltage-gated calcium channels and their future therapeutic potential, Pharmacol. Rev 67 (2015) 821–870. 10.1124/pr.114.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zazueta OE, Armstrong PA, Márquez-Elguea A, Hernández Milán NS, Peterson AE, Ovalle-Marroquín DF, Fierro M, Arroyo-Machado R, Rodriguez-Lomeli M, Trejo-Dozal G, Paddock CD, Rocky Mountain spotted fever in a large metropolitan menter, Mexico-United States border, 2009–2019, Emerg. Infect. Dis 27 (2021) 1567–1576. 10.3201/eid2706.191662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jay R, Armstrong PA, Clinical characteristics of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States: A literature review, J. Vector Borne Dis 57 (2020) 114–120. 10.4103/0972-9062.310863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Londoño AF, Arango-Ferreira C, Acevedo-Gutiérrez LY, Paternina LE, Montes C, Ruiz I, Labruna MB, Díaz FJ, Walker DH, Rodas JD, A cluster of cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in an area of Colombia not known to be endemic for this disease, Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 101 (2019) 336–342. 10.4269/ajtmh.18-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].de Oliveira SV, Willemann MCA, Gazeta GS, Angerami RN, Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Predictive factors for fatal tick-borne spotted fever in Brazil, Zoonoses Public Health 64 (2017) e44–e50. 10.1111/zph.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kato C, Chung I, Paddock C, Estimation of Rickettsia rickettsii copy number in the blood of patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever suggests cyclic diurnal trends in bacteraemia, Clin. Microbiol. Infect 22 (2016) 394–396. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dumler JS, Gage WR, Pettis GL, Azad AF, Kuhadja FP, Rapid immunoperoxidase demonstration of Rickettsia rickettsii in fixed cutaneous specimens from patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Am. J. Clin. Pathol 93 (1990) 410–414. 10.1093/AJCP/93.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huang D, Luo J, OuYang X, Song L, Subversion of host cell signaling: The arsenal of rickettsial species, Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 12 (2022) 995933. 10.3389/fcimb.2022.995933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Walker TS, Rickettsial interactions with human endothelial cells in vitro: adherence and entry, Infect Immun 44 (1984) 205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ireton K, Molecular mechanisms of cell-cell spread of intracellular bacterial pathogens, Open Biol 3 (2013) 130079. 10.1098/rsob.130079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Voss OH, Rahman MS, Rickettsia-host interaction: strategies of intracytosolic host colonization, Pathog. Dis 79 (2021). 10.1093/femspd/ftab015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Woods ME, Olano JP, Host defenses to Rickettsia rickettsii infection contribute to increased microvascular permeability in human cerebral endothelial cells, J. Clin. Immunol 28 (2008) 174–185. 10.1007/s10875-007-9140-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dumler JS, Pappas-Brown V, Clemens EG, Grab DJ, Vascular permeability with rickettsial infections is abrogated by membrane-active chelators, 28th Meeting of the American Society for RickettsiologyBig Sky Resort, MT, 2016, pp. Abstract 81. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dalal PJ, Muller WA, Sullivan DP, Endothelial cell calcium cignaling during carrier cunction and inflammation, Am. J. Pathol 190 (2020) 535–542. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Moccia F, Berra-Romani R, Tanzi F, Update on vascular endothelial Ca2+ signalling: A tale of ion channels, pumps and transporters, World J. Biol. Chem 3 (2012) 127–158. 10.4331/wjbc.v3.i7.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jackson WF, Endothelial ion channels and cell-cell communication in the microcirculation, Front. Physiol 13 (2022) 805149. 10.3389/fphys.2022.805149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hao Y, Wang Z, Frimpong F, Chen X, Calcium-permeable channels and endothelial dysfunction in acute lung injury, Curr. Issues Mol. Biol 44 (2022) 2217–2229. 10.3390/cimb44050150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].King MM, Kayastha BB, Franklin MJ, Patrauchan MA, Calcium regulation of bacterial virulence, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 1131 (2020) 827–855. 10.1007/978-3-030-12457-1_33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Grab DJ, Nyarko E, Nikolskaia OV, Kim YV, Dumler JS, Human brain microvascular endothelial cell traversal by Borrelia burgdorferi requires calcium signaling, Clin. Microbiol. Infect 15 (2009) 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Grab DJ, Garcia-Garcia JC, Nikolskaia OV, Kim YV, Brown A, Pardo CA, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Wilson BA, de ALAP, Scharfstein J, Dumler JS, Protease activated receptor signaling is required for African trypanosome traversal of human brain microvascular endothelial cells, PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 3 (2009) e479. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nyarko E, Grab DJ, Dumler JS, Anaplasma phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils enhance transmigration of Borrelia burgdorferi across the human blood brain barrier in vitro, Int. J. Parasitol 36 (2006) 601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Grab DJ, Perides G, Dumler JS, Kim KJ, Park J, Kim YV, Nikolskaia O, Choi KS, Stins MF, Kim KS, Borrelia burgdorferi, host-derived proteases, and the blood-brain barrier, Infection and immunity 73 (2005) 1014–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim Y, Clemens E, Wang J, Grab D, Dumler JS, High-throughput screening of modulators of cellular calcium metabolism as potential drugs against rickettsia-induced microvascular dysfunction, 30th Meeting of the American Society for Rickettsiology: Rickettsial Diseases at the Vector-Pathogen InterfaceSanta Fe, New Mexico, 2019, pp. Abstract 61. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kitakaze M, Karasawa A, Kobayashi H, Tanaka H, Kuzuya T, Hori M, Benidipine: A new Ca2+ channel blocker with a cardioprotective effect, Cardiovasc. Drug Rev 17 (2006) 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Weiss N, Zamponi GW, T-type calcium channels: From molecule to therapeutic opportunities, Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 108 (2019) 34–39. 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ball CJ, Wilson DP, Turner SP, Saint DA, Beltrame JF, Heterogeneity of L- and T-channels in the vasculature: rationale for the efficacy of combined L- and T-blockade, Hypertension 53 (2009) 654–660. 10.1161/hypertensionaha.108.125831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhou C, Wu S, T-type calcium channels in pulmonary vascular endothelium, Microcirculation 13 (2006) 645–656. 10.1080/10739680600930289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yao K, Nagashima K, Miki H, Pharmacological, pharmacokinetic, and clinical properties of benidipine hydrochloride, a novel, long-acting calcium channel blocker, J. Pharmacol. Sci 100 (2006) 243–261. 10.1254/jphs.dtj05001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Li H, Zhang LK, Li SF, Zhang SF, Wan WW, Zhang YL, Xin QL, Dai K, Hu YY, Wang ZB, Zhu XT, Fang YJ, Cui N, Zhang PH, Yuan C, Lu QB, Bai JY, Deng F, Xiao GF, Liu W, Peng K, Calcium channel blockers reduce severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) related fatality, Cell Res 29 (2019) 739–753. 10.1038/s41422-019-0214-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Biggs HM, Behravesh CB, Bradley KK, Dahlgren FS, Drexler NA, Dumler JS, Folk SM, Kato CY, Lash RR, Levin ML, Massung RF, Nadelman RB, Nicholson WL, Paddock CD, Pritt BS, Traeger MS, Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever and other spotted fever group rickettsioses, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis - United States, MMWR Recomm. Rep 65 (2016) 1–44. 10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Londoño AF, Mendell NL, Walker DH, Bouyer DH, A biosafety level-2 dose-dependent lethal mouse model of spotted fever rickettsiosis: Rickettsia parkeri Atlantic Rainforest strain, PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 13 (2019) e0007054. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Reed SC, Serio AW, Welch MD, Rickettsia parkeri invasion of diverse host cells involves an Arp2/3 complex, WAVE complex and Rho-family GTPase-dependent pathway, Cell. Microbiol 14 (2012) 529–545. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Woods ME, Wen G, Olano JP, Nitric oxide as a mediator of increased microvascular permeability during acute rickettsioses, Ann N Y Acad Sci 1063 (2005) 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Londoño AF, Mendell NL, Valbuena GA, Routh AL, Wood TG, Widen SG, Rodas JD, Walker DH, Bouyer DH, Whole-genome sequence of Rickettsia parkeri strain Atlantic Rainforest, isolated from a Colombian tick, Microbiol. Resour. Announc 8 (2019). 10.1128/mra.00684-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kim YV, Pearce D, Kim KS, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent invasion of microvascular endothelial cells of human brain by Escherichia coli K1, Cell. Tissue Res 332 (2008) 427–433. 10.1007/s00441-008-0598-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fenollar F, La Scola B, Inokuma H, Dumler JS, Taylor MJ, Raoult D, Culture and phenotypic characterization of a Wolbachia pipientis isolate, J Clin Microbiol 41 (2003) 5434–5441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Reller ME, Dumler JS, Optimization and evaluation of a multiplex quantitative PCR assay for detection of nucleic acids in human blood samples from patients with spotted fever rickettsiosis, typhus rickettsiosis, scrub typhus, monocytic ehrlichiosis, and granulocytic anaplasmosis, J. Clin. Microbiol 58 (2020). 10.1128/jcm.01802-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Besler C, Doerries C, Giannotti G, Lüscher TF, Landmesser U, Pharmacological approaches to improve endothelial repair mechanisms,. Expert Rev Cardiovasc. Ther 6 (2008) 1071–1082. 10.1586/14779072.6.8.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hansen PB, Functional importance of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels in the cardiovascular and renal system: news from the world of knockout mice, Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 308 (2015) R227–237. 10.1152/ajpregu.00276.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Catterall WA, Voltage-gated calcium channels, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3 (2011) a003947. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lacinová L, T-type calcium channel blockers - new and notable, Gen. Physiol. Biophys 30 (2011) 403–409. 10.4149/gpb_2011_04_403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Silverman DJ, Santucci LA, Potential for free radical-induced lipid peroxidation as a cause of endothelial cell injury in Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Infect Immun 56 (1988) 3110–3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Walker DH, Cain BG, The rickettsial plaque. Evidence for direct cytopathic effect of Rickettsia rickettsii, Lab Invest 43 (1980) 388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Berrich M, Boulouis H-J, Monteil M, Kieda C, Haddad N, Vascular endothelium and vector borne pathogen interactions, Curr. Immunol. Rev 8 (2012) 227–247. 10.2174/157339512800672010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Silverman DJ, Santucci LA, Sekeyova Z, Heparin protects human endothelial cells infected by Rickettsia rickettsii, Infection and immunity 59 (1991) 4505–4510. 10.1128/iai.59.12.4505-4510.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Berridge MJ, The inositol trisphosphate/calcium signaling pathway in health and disease, Physiol. Rev 96 (2016) 1261–1296. 10.1152/physrev.00006.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Salje J, Cells within cells: Rickettsiales and the obligate intracellular bacterial lifestyle, Nature reviews. Microbiology 19 (2021) 375–390. 10.1038/s41579-020-00507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yeh YC, Parekh AB, CRAC channels and Ca2+-dependent gene expression, in: Kozak JA, Putney JW Jr. (Eds.) Calcium Entry Channels in Non-Excitable Cells, CRC Press/Taylor & Francis © 2017 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC., Boca Raton (FL), 2018, pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rahm AK, Lugenbiel P, Schweizer PA, Katus HA, Thomas D, Role of ion channels in heart failure and channelopathies, Biophys. Rev 10 (2018) 1097–1106. 10.1007/s12551-018-0442-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Huang K, Luo YB, Yang H, Autoimmune channelopathies at neuromuscular junction, Front. Neurol 10 (2019) 516. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nock AM, Clark TR, Hackstadt T, Regulator of actin-based motility (RoaM) downregulates actin tail formation by Rickettsia rickettsii and is negatively selected in mammalian cell culture, mBio 13 (2022) e0035322. 10.1128/mbio.00353-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lamason RL, Bastounis E, Kafai NM, Serrano R, Del Alamo JC, Theriot JA, Welch MD, Rickettsia Sca4 reduces vinculin-mediated intercellular tension to promote spread, Cell 167 (2016) 670–683.e610. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]