Abstract

Nucleus segmentation represents the initial step for histopathological image analysis pipelines, and it remains a challenge in many quantitative analysis methods in terms of accuracy and speed. Recently, deep learning nucleus segmentation methods have demonstrated to outperform previous intensity- or pattern-based methods. However, the heavy computation of deep learning provides impression of lagging response in real time and hampered the adoptability of these models in routine research. We developed and implemented NuKit a deep learning platform, which accelerates nucleus segmentation and provides prompt results to the users. NuKit platform consists of two deep learning models coupled with an interactive graphical user interface (GUI) to provide fast and automatic nucleus segmentation “on the fly”. Both deep learning models provide complementary tasks in nucleus segmentation. The whole image segmentation model performs whole image nucleus whereas the click segmentation model supplements the nucleus segmentation with user-driven input to edits the segmented nuclei. We trained the NuKit whole image segmentation model on a large public training data set and tested its performance in seven independent public image data sets. The whole image segmentation model achieves average DICE = 0.814 and IoU = 0.689. The outputs could be exported into different file formats, as well as provides seamless integration with other image analysis tools such as QuPath. NuKit can be executed on Windows, Mac, and Linux using personal computers.

Keywords: Deep learning, machine learning, nucleus segmentation, digital pathology

1. Introduction

Histopathological images represent the primary source for pathologists to perform cancer diagnostic in the clinical setting. These images were stained by hematoxylin (purple color) to label nuclei of cells while eosin is used to counterstain the remaining cytoplasm of cells (pink color) (Fig. 1). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining is the most common type of histopathological images used for quantitative data analysis. Additional antibodies could be stained to represent different cell types to study the tumor microenvironment in the context of cancer research.1 For histopathological image analysis, nucleus segmentation represents one of the initial steps in quantitative data analysis pipelines. Popular open-source software such as Cell Profiler2 and QuPath3 provide nucleus segmentation in their analysis pipelines. Yet, multiple challenges remain in many quantitative analysis methods in terms of accuracy of segmented nuclei and speed in segmentation process (as some methods required manual segmentation).4

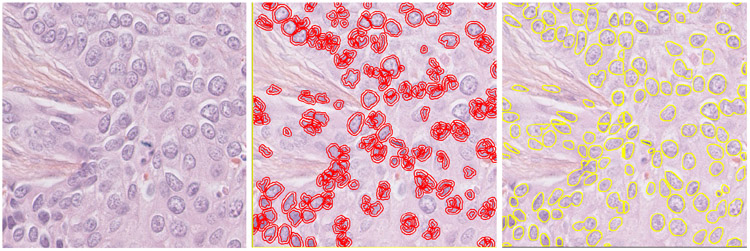

Fig. 1.

Examples of nucleus segmentation by QuPath and NuKit. The left panel is the original H&E image from TNBC 11_1. The middle panel is the segmentation generated by QuPath using the default setting. The right panel is the segmentation predicted by NuKit.

Recently, deep learning methods for nucleus segmentation on histopathological images become the mainstream in digital pathology. For example, Graham et al.5 developed HoVer-Net, a deep learning model that can simultaneous perform segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histopathological images. When compared HoVer-Net with several deep learning methods, as well as non-deep learning methods, they showed that all deep learning-based methods are superior to those intensity- or pattern-based methods (such as Cell Profiler or QuPath). Hollandi et al. provided a recent review of deep learning methods in nucleus segmentation.4 Although deep learning methods have demonstrated to be useful in nucleus segmentation for pathological images, adopting these pre-trained models in digital pathology or clinical research remains limited. Two main factors limit the usage of deep learning methods in routine research: (1) many models required some technical background to execute the programs and (2) the speed of returning the results to the users.

To overcome these limitations, we have developed and implemented NuKit, a deep learning platform which accelerates nucleus segmentation and provides prompt results to the users. NuKit platform consists of two deep learning models coupled with an interactive graphical user interface (GUI) to provide fast and automatic nucleus segmentation “on the fly”. The two deep learning models are: (1) the whole image segmentation model and (2) the click segmentation model. Both deep learning models provide complementary tasks in nucleus segmentation in the NuKit platform. The whole image segmentation model performs whole image nucleus whereas the click segmentation model supplements the nucleus segmentation with user-driven input to edit the segmented nuclei. Both pre-trained models were embedded in the GUI, which provides interactive and prompt response to users in analyzing their histopathological images. Moreover, the NuKit results can be exported to various interoperable formats such as binary mask, CSV and Object data of QuPath for further data analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the NuKit results as compared to QuPath.

2. Methods

2.1. Nucleus segmentation training and testing data sets

Training Data Set.

We used PanNuke6 as the training data set for the whole image nucleus segmentation model. This data set contains 189,077 nuclei that came from 7901 image tiles. The sources of this data set were curated from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and included some in-house data as previously described.7 All training data are H&E-stained images with 40× magnification.

Testing Data Sets.

We used seven data sets as the test sets of the evaluation of our model, and these images are primarily collected from TCGA, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) and Curie Institute (Curie Inst.). All testing data are H&E-stained images with 40× magnification except CPM-158 and CPM-178 data sets which some are scanned with 20× magnification. To check for data duplication in the training and testing data sets, we assumed two image tiles are the same if both have the same resolution and pixel value. If two image tiles from the same source have different resolution, they are treated as different image tiles. There are no images overlapped in these data sets but there are some image tiles obtaining from the same image source with different resolution. Table 1 lists the data sets used in this study.

Table 1.

Nucleus segmentation data set.

| Data set | Image tiles |

Nuclei | Tile pixels | Max pixels |

Min pixels |

Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | PanNuke | 7901 | 189,077 | 256 × 256 | 4970 | 6 | TCGA, in-house |

| CPM-15 | 15 | 2905 | 439 × 439 – 1032 × 808 | 3658 | 1 | TCGA | |

| CPM-17 | 64 | 7570 | 500 × 500, 600 × 600 | 3680 | 10 | TCGA | |

| Kumar | 30 | 16,954 | 1000 × 1000 | 5274 | 2 | TCGA | |

| Test | MoNuSeg | 44 | 23,657 | 1000 × 1000 | 3205 | 1 | TCGA |

| TNBC | 50 | 4056 | 512 × 512 | 3078 | 2 | Curie Inst. | |

| CoNSeP | 41 | 24,332 | 1000 × 1000 | 8757 | 1 | UHCW | |

| CryoNuSeg | 30 | 8251 | 512 × 512 | 2426 | 1 | TCGA |

Mask Labeling.

For the label masks, there are three different annotation formats:

Each nucleus assigns to a different identity number, there is no overlap: CPM-15, CPM-17, Kumar,9 TNBC,10 and CoNSeP.5

There are some overlapping at the same pixel: PanNuke. There were a few overlapping: two type of cells are assigned to the same pixel. If this occurs, we follow this order 0: Neoplastic cells, 1: Inammatory, 2: Connective/soft tissue cells, 3: Dead cells, 4: Epithelial. The higher order will dominate the result. For example, if 4 and 0 are assigned to the same pixel, we define this pixel as 4.

Using points constructs an annotation, drawing the region from points is required: MoNuSeg11 and CryoNuSeg.12 Different drawing methods affect the regions of nucleus. In addition, it is difficult to decide which pixel belongs to which nucleus when overlapping. In this research, we use Bresenham’s line algorithm to draw a line between two points. For overlapping regions, we used “First In Order”: a region belongs to the first claim from the annotation data file.

Table 1 shows some statistics for the label mask annotation. For the number of nuclei, as annotation 1, we define each identity number as a nuclei; As annotation 2 and 3, we defined a nucleus whose eight directions (up left, up, …, bottom, bottom right) do not have other masks. The maximal pixel number is from 2426 to 8757. It shows that the shape of nucleus has wide diversity. The minimal pixel number is from 1 to 6. It is possible to be the artifacts or human errors. Some research removes the masks when the region is under a threshold such as 30 pixels. In this paper, we used all annotations from the original data sets.

2.2. Two deep learning models

These two models were based on a modified Mask-RCNN13 with different size of inputs and parameters. We used PyTorch and the source code on its tutorial.a The architecture includes three parts: Backbone, Region Proposal Network (RPN), and RoIAlign. The backbone architecture is set as the 152-layer ResNet.14 The RPN is the same as original Mask-RCNN, here we have two classes: Nucleus or Non-Nucleus for the input image. RoIAlign is the same as the original Mask-RCNN with some parameter modification. The detail for the modification will be described in the following sections. We use the default model from torchvision without pre-trained weights.b

2.2.1. Whole image nucleus segmentation model

The whole image nucleus segmentation model is based on the previous architecture (see Fig. 2). The input is an H&E-stained image and the output is the masks of nucleus. We added several steps to avoid any image scaling process. A detailed description of the architecture modification is listed as follows:

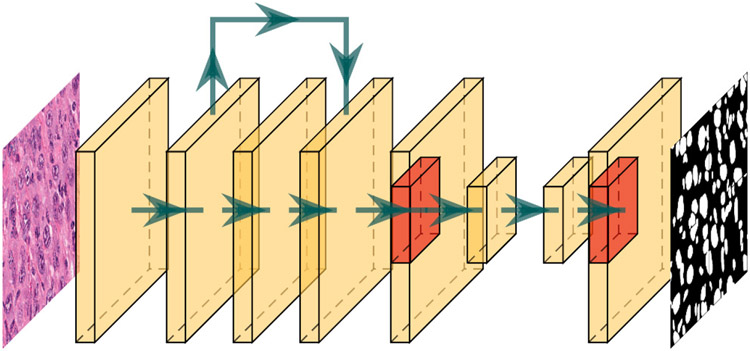

Fig. 2.

The architecture for the whole image nucleus segmentation model. The red region is one of the boxes to detect instance segmentation in Mask-RCNN.

Remove the pooling layer in the first layer at the backbone.

Set AnchorGenerator sizes to 10, 20, 40, and 80 with aspect ratios to 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 at RPN.

Set ROIPooling to Multi-Scale RoIAlign with output size to 10 and sampling ratio to 1 at RoIAlign.

Set Mask ROIPooling to Multi-Scale RoIAlign with output size to 20 and sampling ratio to 1 at RoIAlign.

We used PanNuke as the training data set. Here is a detailed description of our training settings: First, we combined five different type of cells to a binary mask. Second, we used Depth-First search with four directions (up, left, right, bottom) to identify all objects in this binary mask. There is a total 182,612 objects. The model is trained for 1864 epochs using Nvidia V100 GPU. The batch size is 4 and the data is randomly augmented with rotation at 90-degree intervals and horizontal/vertical flipping. We use stochastic gradient descent as the optimizer with learning rate 0.0005, momentum 0.9 and weight decay 0.0005.

2.2.2. Nucleus click segmentation model

The nucleus click segmentation model is similar to the previous architecture (see Fig. 3). However, this model is used to find a region nearby the location when a user clicks on the image. The input is a 64 × 64 image which sets the clicked location at (32 × 32) at this image. The output is a binary mask. As same as previous architecture, we added several steps to avoid any image scaling process. A detailed description of the architecture modification is listed as follows:

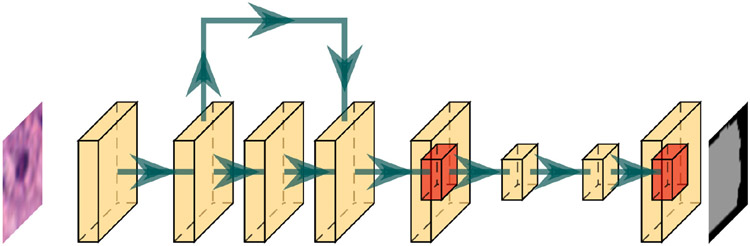

Fig. 3.

The architecture for the nucleus click segmentation model.

Remove the pooling layer in the first layer at the backbone.

Change the kernel in the first layer from the size 7 × 7 to 3 × 3 with stride and padding as 1 and input channel from 3 to 4 at the backbone.

Set AnchorGenerator sizes to 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 with aspect ratios to 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 at RPN.

Set ROIPooling to Multi-Scale RoIAlign with output size to 10 and sampling ratio to 1 at RoIAlign.

Set Mask ROIPooling to Multi-Scale RoIAlign with output size to 20 and sampling ratio to 1 at RoIAlign.

We used PanNuke as the training data set. Here is a detailed description of how to generate our training data: First, we combined five different cell types to a binary mask. Second, we used Depth-First search with eight directions (up left, up, …, bottom, bottom right) to identify all objects in this binary mask. There are a total 160,368 objects. Third, the input 64 × 64 image, a portion of the whole 256 × 256 image is generated. We randomly picked a location in the original image. Then, extend the location to a 64 × 64 image by setting this location at (32 × 32) and fill the neighbor pixels. If the location is at the border, the out-of-border pixels are filled using black pixels. In addition to the three layers of input image, we add an extra layer for the information of “click”, the click location is randomly chosen at the previous 64 × 64 image. In this layer, the location of clicked is set to 1 and others are set to 0. For the data balance, we force the location of click to be 50% inside a nucleus which means there is 50% chance the output label has no nucleus. The model is trained for 900 epochs using Nvidia 3060 GPU. The batch size is 2 and the data is randomly augmented with rotation at 90-degree intervals and horizontal/vertical flipping. We use stochastic gradient descent as the optimizer with learning rate 0.0005, momentum 0.9 and weight decay 0.0005.

2.3. Implementation of NuKit platform

The NuKit platform is programmed using the Rust programming language. The GUI is implemented using the egui library. Therefore, the application can be executed on Windows, Mac, and Linux. In addition, the user can run it without installation, this makes it possible to deploy it in many critical environments such as the clinical area which internet access is restrict. The deep learning inference engine is based on the Onnx Runtime framework. The mainstream deep learning frameworks such as Tensorflow or Pytorch could convert their format to the Onnx Runtime format. We used CPU for the deep learning inference, it takes couple of seconds to predict the segmentation using eight threads at the Apple M1 Pro. The GUI is carefully designed to enhance the user experience. Each time the GUI loads a portion of the whole image. When a user reviews the segmentation result, the application processes the nearby regions in the background. This saves a lot of waiting time and brings a smooth user experience when using NuKit. No installation is required as NuKit platform incorporates all the necessary pre-trained models. NuKit is freely available at http://tanlab.org/NuKit/.

2.4. Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the performance of NuKit, two commonly evaluation metrics used to measure the semantic segmentation quality were calculated: Eq. (1) DICE coefficient (DICE) and Eq. (2) Intersection over Union (IoU). Let be defined as “Ground Truth Area” and be defined as “Predicted Area”.

| (1) |

| (2) |

The IoU is usually lower than DICE because DICE emphasizes the region of matched (see Eq. (1)). However, IoU might be better to present the quality of semantic segmentation.

3. Results

First, we describe the quality of our deep learning model via previous evaluation metrics. Second, we present our deep learning inference performance on different operating systems and hardware. Third, we illustrate how to integrate NuKit with other pipelines for downstream image analysis.

3.1. Evaluation of the nucleus segmentation model

Table 2 summarizes the evaluation results of the nucleus segmentation model trained on PanNuke data set and tested on the various test data sets. The test data is patched using 256 × 256 tiles and padded using white color in the end. For example: if an image size is 1000 × 1000, we patched white pixels at the location 1001–1024. After this patching, the image is split into 256 × 256 tiles to predict the segmentation masks. This process is repeated in 16 iterations. The final segmented mask is the combined 16 256 × 256 tile images into a 1000 × 1000 images (removing the padding part). As listed in Table 2, the nucleus segmentation model achieved an average DICE of 0.814 (range 0.783–0.854) and an average IoU of 0.689 (range 0.646–0.746). The results in Table 2 shows that the nucleus segmentation model is generalizable to predict on different data sets. For example, NuKit achieved 0.793 and 0.854 DICE for non-TCGA data sets TNBC and CoNSeP, respectively. These results are comparable to the average DICE 0.814 for TCGA data sets.

Table 2.

Nucleus segmentation model results on test data sets.

| Data set | DICE | IoU | Nucleus detected ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPM-15 | 0.807 | 0.680 | 0.878 |

| CPM-17 | 0.839 | 0.725 | 1.073 |

| Kumar | 0.812 | 0.684 | 1.098 |

| MoNuSeg | 0.809 | 0.680 | 1.154 |

| TNBC | 0.793 | 0.663 | 0.913 |

| CoNSeP | 0.854 | 0.746 | 1.012 |

| CyroNuSeg | 0.783 | 0.646 | 1.238 |

| Average | 0.814 | 0.689 | 1.052 |

We further evaluated the nucleus detected ratio in the prediction results of NuKit and other methods. We used Depth-First search to find out the number of objects in the predicted masks comparing to the objects in the ground truth. We defined a single nucleus mask as its eight directions (up left, up, …, bottom, bottom right) does not have other masks. From this evaluation, the average nucleus detected ratio of our model is 1.052 (range 0.878–1.238) (Table 2). This indicates that a large portion of nucleus could be detected using our nucleus segmentation model. For the missed ones, we could use the click segmentation model to correct it. This will significantly improve the annotation time of nucleus segmentation in the histopathological images.

In addition, NuKit nucleus segmentation model achieved comparable DICE results with the state-of-the-art deep learning methods, as summarized in Table 3. All deep learning methods outperform those non-deep learning methods, as indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Nucleus segmentation model DICE results comparing to other methods. * indicates that the results were obtained from Ref. 5.

| Methods | TNBC | All CoNSeP | CoNSeP test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-deep learning | Cell Profiler* | — | — | 0.434 |

| QuPath* | — | — | 0.588 | |

| Deep Learning | FCN8 + WS* | 0.726 | 0.609 | — |

| SegNet + WS* | 0.758 | 0.681 | — | |

| U-Net* | 0.681 | 0.585 | — | |

| Mask-RCNN* | 0.705 | 0.606 | — | |

| DCAN* | 0.725 | 0.609 | — | |

| Micro-Net* | 0.701 | 0.644 | — | |

| DIST* | 0.719 | 0.621 | — | |

| HoVer-Net* | 0.749 | 0.664 | — | |

| NuKit | 0.793 | 0.854 | 0.860 |

3.2. Deep learning inference performance

There are 313,545,608 parameters in the whole image nucleus segmentation model. We tested the deep learning inference performance on speed (computational time) it costs from inputting an image and inferencing through the model and outputting the mask. It requires an average 1.5 s for a 256 × 256 size image in Apple M1 Pro using eight threads with ONNX Runtime v1.12.0. On a Windows 10 Desktop, it takes an average 1.5 s in Intel i5-10505 CPU using six threads with ONNX Runtime v1.12.0. The run time for NuKit is reasonable fast.

3.3. Pipeline using Nukit and QuPath

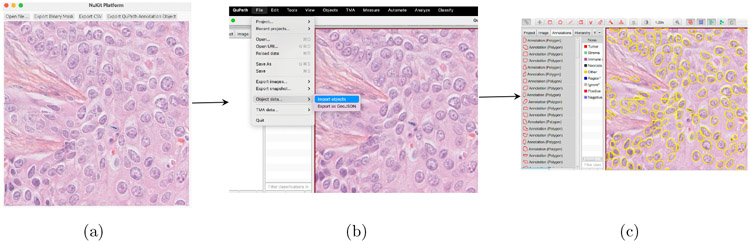

NuKit platform can export the segmented results into the following formats: (1) Binary mask for the label of the deep learning training; (2) CSV contains coordinates of segmented nuclei for further statistical analysis; and (3) GeoJSON is an annotated object file for QuPath software. NuKit outputs are interoperable and easy to integrate with other quantitative image analysis pipelines. Figure 4 illustrates the pipeline of integrating NuKit with QuPath software. Step 1: user will use NuKit to perform fast and automatic nucleus segmentation by loading a H&E-stained image. After automatic segmentation, the user can modify the result by using the click nucleus segmentation model. Then, user can export the results to GeoJSON format. Step 2: To load the NuKit results into QuPath, user will import the GeoJSON format from NuKit to QuPath. Then, user can take advantage of the additional analytical tools available in the QuPath software to perform further image analysis with the help of NuKit deep learning fast nucleus segmentation platform.

Fig. 4.

The workflow of exporting NuKit outputs and loading into QuPath Image Analysis Pipeline. (a) Select “Export QuPath Annotation Object” in the NuKit platform to output GeoJSON file. (b) In QuPath software, open the image and load the GeoJSON file as new project. (c) Segmented nuclei by NuKit platform were loaded and further quantitative image analysis could be performed using QuPath software.

4. Discussion

We developed and implemented NuKit, a novel and fast nucleus segmentation of histopathological images based on two deep learning methods coupled with an interactive GUI. The pre-trained deep learning models were evaluated on different data sets and demonstrated to achieve high accuracy in nucleus segmentation. The click segmentation model provides easy and intuitive step for users to modify the segmented regions, either removing or adding a missed nucleus by simple “click” on the image. NuKit outputs are interoperable and easy to integrate with other quantitative image analysis pipelines.

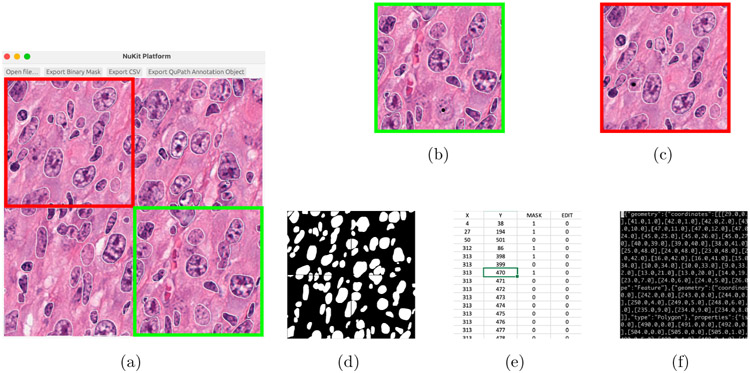

One of the challenges of training and testing deep learning models in nucleus segmentation is the lack of “high-quality” data sets. Most public nucleus data sets are generated using a deep learning model to speed up the annotation process. After that, human experts are required to manually correct previous results. Data sets such as PanNuke6 and CryoNuSeg12 are developed using the previous method to ease the time consuming manual annotation. FastPathology15 is an open-source platform which could load a whole slide images and do nucleus segmentation using its pre-trained model. However, it required to complete the whole segmentation to initiate the next process and this process takes a long time to complete. Furthermore, the lack of modifying tools on the segmented outputs will require additional software to correct automatic segmentation process. On the other hand, several interactive approaches such as NuClick,16 using the coordination of a click to segment a nucleus through a deep learning model are available for this task. Unfortunately, these approaches require extended time to click for each nucleus. Here, NuKit provides one stop solution (see Fig. 5): first, using a deep learning model processes the whole image segmentation; Second, using the click model processes the segmentation modification. In addition, the platform enhances the user experience via interactive and intuitive GUI for user. Comparing to other platforms, NuKit is innovative as it integrates an accurate nucleus segmentation model and one click segmentation model to promptly return the segmented results.

Fig. 5.

An overview of the NuKit platform: (a) Load a H&E-stained image to NuKit. (b) A nucleus is removed by a click (black spot) in the region of green. (c) A nucleus is added by a click (black spot) in the region of red. (d) A binary mask is exported by clicking “Export Binary Mask”. (e) A CSV file including coordination and mask information is exported by clicking “Export CSV”. (f) A GeoJSON for QuPath is exported by clicking “Export QuPath Annotation Object”.

In addition, NuKit platform is a stand-alone application which could run on Windows, Mac, and Linux using standard personal computer. For deep learning inference, only CPU is used such that NuKit could be generalized and applicable to different hardware (for example, X86 and ARM CPUs). This could help deploy NuKit platform to many different sites such as clinics and wider users. For interoperability with existing quantitative image analysis tools, the segmentation results from NuKit could be exported to different formats such as the GeoJSON for QuPath software or binary masks for the label data of deep learning. This provides a practical pipeline in the ecosystem of computation pathology. In the future, we plan to support more formats which other software requires.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have introduced NuKit, an innovation platform which combines two deep learning models coupled with interactive GUI to accelerate nucleus segmentation task in histopathological images. We have shown that (1) the nucleus segmentation model achieved good performance (DICE and IoU) in several test sets. (2) the click nucleus segmentation model allowed user to edit/modify the segmented nuclei. NuKit is implemented and tested to run on many mainstream computer operation systems as a stand-alone program. The outputs of NuKit are interoperable with other quantitative image analysis tools to facilitate the ecosystem of computational pathology to many formats to combine with other software to construct pipelines. We have shown that this platform could reduce the time of manual annotation enormously. We believe that NuKit provides a new platform to bridge the pre-trained deep learning models into digital pathology and clinical usage.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award No. R01DE030508 (to A.C.T. and C.H.C.) and the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Grant No. (21K04) (to C.H.C. and A.C.T.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Biographies

Ching-Nung Lin received his B.S. in Applied Mathematics from Chinese Culture University, M.S. and Ph.D. in Computer Science and Information Engineering from National Dong Hwa University in 2006, 2013 and 2019, respectively.

Dr. Lin conducted his intership at The French National Institute for Computer Science and Applied Mathematics (INRIA) at 2015, post-doctoral research training at the Moffitt Cancer Center from 2021 to 2022.

He was hired as Applied Research Scientist at the Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics at the Moffitt Cancer Center in 2022. Dr. Lin was recruited to the Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah as a research scientist. His research interests are translational bioinformatics and cancer research using artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Christine H. Chung received a B.S. degree from the University of California at Los Angeles, an M.S. degree from the Johns Hopkins University, and an M.D. degree from Eastern Virginia Medical School. She began her academic career through the Physician-Scientist Research Pathway at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill where she completed the combined Internal Medicine-Medical Oncology Fellowship and Postdoctoral training in Basic Science Research.

After working as an Assistant Professor at Vanderbilt University and an Associate Professor at Johns Hopkins University, she is currently serving as Chair of the Department of Head and Neck-Endocrine Oncology at Moffitt Cancer Center.

Her translational and clinical research has focused on head and neck cancer using a genomic analysis approach. Her research has shown that tumors sharing the same histology have distinct molecular gene expression profiles, and these molecularly defined patient populations have distinctly different clinical outcomes. In addition, the evaluation of tumor immune microenvironment in tobacco-related and human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer can further contribute to identification of novel molecular processes which can be therapeutically exploited. Beyond the laboratory studies, she has participated in numerous clinical trials and conducted correlative studies developing biomarkers of clinical outcomes.

Aik Choon Tan received his B.Eng. degree in Chemical/Bioprocess Engineering from the University of Technology Malaysia, and his Ph.D. degree in Computer Science/Bioinformatics from University of Glasgow, UK, in 2000 and 2005, respectively.

Dr. Tan conducted his post-doctoral research training at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine from 2004 to 2009. He was an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in 2009 and promoted to Associate Professor in 2013. Dr. Tan was recruited to the Moffitt Cancer Center in 2019 as the Vice-Chair of the Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics. In 2022, Dr. Tan was appointed as the inaugural Senior Director of Data Science at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah. He holds the Jon M. and Karen Huntsman Endowed Chair in Cancer Data Science, Professor of Oncological Sciences and Biomedical Informatics.

His research interests are translational bioinformatics and cancer systems biology, primarily by developing computational and machine learning methods for the analysis and integration of high-throughput cancer “omics” data in understanding and overcoming treatment resistance mechanisms in cancer. His lab acts as a “connector” to provide seamless integration of computational and statistical methods in experimental and clinical cancer research.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Lee K, Lockhart JH, Xie M, Chaudhary R, Slebos RJC, Flores ER, Chung CH, Tan AC, Deep learning of histopathology images at the single cell level, Front Artif Intell 4:754641, 2021, doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.754641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter AE, Jones TR, Lamprecht MR, Clarke C, Kang IH, Friman O, Guertin DA, Chang JH, Lindquist RA, Moffat J, Golland P, Sabatini DM, CellProfiler: Image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes, Genome Biol 7(10):R100, 2006, doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bankhead P et al. , QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis, Sci Rep 7(1):1–7, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollandi R, Moshkov N, Paavolainen L, Tasnadi E, Piccinini F, Horvath P, Nucleus segmentation: Towards automated solutions, Trends Cell Biol 32:295–310, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham S, Vu QD, Raza SEA, Azam A, Tsang YW, Kwak JT, Rajpoot N, HoVer-Net: Simultaneous segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histology images, Med Image Anal 58:101563, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gamper J, Koohbanani NA, Benes K, Graham S, Jahanifar M, Khurram SA, Azam A, Hewitt K, Rajpoot N, PanNuke dataset extension, insights and baselines, arXiv, arXiv:2003.10778, 2020, doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2003.10778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kainz P, Urschler M, Schulter S, Wohlhart P, Lepetit V, You should use regression to detect cells, in Navab N, Hornegger J, Wells WM, Frangi AF (eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015, Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 276–283, 2015, ISBN 978-3-319-24574-4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vu QD, Graham S, Kurc T, To MNN, Shaban M, Qaiser T, Koohbanani NA, Khurram SA, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Zhao T, Gupta R, Kwak JT, Rajpoot N, Saltz J, Farahani K, Methods for segmentation and classification of digital microscopy tissue images, Front Bioeng Biotechnol 7:53, 2019, doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar N, Verma R, Sharma S, Bhargava S, Vahadane A, Sethi A, A dataset and a technique for generalized nuclear segmentation for computational pathology, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 36(7):1550–1560, 2017, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2017.2677499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naylor P, Laé M, Reyal F, Walter T, Segmentation of nuclei in histopathology images by deep regression of the distance map, IEEE Trans Med Imaging 38(2):448–459, 2019, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2865709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar N, Verma R, Anand D, Zhou Y, Onder OF, Tsougenis E, Chen H, Heng PA, Li J, Hu Z, Wang Y, Koohbanani NA, Jahanifar M, Tajeddin NZ, Gooya A, Rajpoot N, Ren X, Zhou S, Wang Q, Shen D, Yang CK, Weng CH, Yu WH, Yeh CY, Yang S, Xu S, Yeung PH, Sun P, Mahbod A, Schaefer G, Ellinger I, Ecker R, Smedby O, Wang C, Chidester B, Ton TV, Tran MT, Ma J, Do MN, Graham S, Vu QD, Kwak JT, Gunda A, Chunduri R, Hu C, Zhou X, Lotfi D, Safdari R, Kascenas A, O’Neil A, Eschweiler D, Stegmaier J, Cui Y, Yin B, Chen K, Tian X, Gruening P, Barth E, Arbel E, Remer I, Ben-Dor A, Sirazitdinova E, Kohl M, Braunewell S, Li Y, Xie X, Shen L, Ma J, Baksi KD, Khan MA, Choo J, Colomer A, Naranjo V, Pei L, Iftekharuddin KM, Roy K, Bhattacharjee D, Pedraza A, Bueno MG, Devanathan S, Radhakrishnan S, Koduganty P, Wu Z, Cai G, Liu X, Wang Y, Sethi A, A multi-organ nucleus segmentation challenge, IEEE Trans Med Imaging 39(5):1380–1391, 2020, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2947628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahbod A, Schaefer G, Bancher B, Löw C, Dorffner G, Ecker R, Ellinger I, Cryonuseg: A dataset for nuclei instance segmentation of cryosectioned h&e-stained histological images, Comput Biol Med 132:104349, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R, Mask R-CNN, 2017 IEEE Int. Conf. Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 2980–2988, 2017, doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2017.322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J, Deep residual learning for image recognition, 2016 IEEE Conf. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 770–778, 2016, doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen A, Valla M, Bofin AM, De Frutos JP, Reinertsen I, Smistad E, Fastpathology: An open-source platform for deep learning-based research and decision support in digital pathology, IEEE Access 9:58216–58229, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koohbanani NA, Jahanifar M, Tajadin NZ, Rajpoot N, Nuclick: A deep learning framework for interactive segmentation of microscopic images, Med Image Anal 65:101771, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]