Abstract

Improved reproductive management has allowed dairy cow pregnancies to be optimized for beef production. The objective of this sire-controlled study was to test the feedlot performance of straightbred beef calves raised on a calf ranch and to compare finishing growth performance, carcass characteristics, and mechanistic responses relative to beef × dairy crossbreds and straightbred beef cattle raised in a traditional beef cow/calf system. Tested treatment groups included straightbred beef steers and heifers reared on range (A × B; n = 14), straightbred beef steers and heifers born following embryo transfer to Holstein dams (H ET; n = 15) and Jersey dams (J ET; n = 16) The finishing trial began when cattle weighed 301 ± 32.0 kg and concluded after 195 ± 1.4 d. Individual intake was recorded from day 28 until shipment for slaughter. All cattle were weighed every 28 d; serum was collected from a subset of steers every 56 d. Cattle of straightbred beef genetics (A × B, H ET, and J ET) and A × H were similar in final shrunk body weight, dry matter intake, and carcass weight (P > 0.05 for each variable). Compared with A × J cattle, J ET was 42 d younger at slaughter with 42 kg more carcass weight (P < 0.05 for both variables). No difference was observed in longissimus muscle area between all treatments (P = 0.40). Fat thickness was greatest for straightbred beef cattle, least for A × J cattle, and intermediate for A × H cattle (P < 0.05). When adjusted for percentage of adjusted final body weight, feed efficiency was greater for straightbred beef cattle compared with beef × dairy crossbred cattle (P = 0.04). A treatment × day interaction was observed for circulating insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I; P < 0.01); 112 d after being implanted, beef × dairy crossbred cattle had greater circulating IGF-I concentration than cattle of straightbred beef genetics (P < 0.05). Straightbred beef calves born to Jersey cows had more efficient feedlot and carcass performance than A × J crossbreds. Calves of straightbred beef genetics raised traditionally or in a calf ranch performed similarly in the feedlot.

Keywords: beef, dairy, embryo, feedlot

Since Jersey maternal genetics offer less value than maternal Holstein genetics for beef × dairy crossbreeding programs, straightbred beef embryos can be used in Jersey cows to improve feedlot and carcass performance of resulting calves.

Introduction

Beef semen use has increased as dairy semen use has decreased in the United States, largely from beef semen being used more frequently on dairies (McWhorter et al., 2020; National Association of Animal Breeders, 2022). Increased emphasis is placed on optimizing calves that originate from dairies for beef production because using beef genetics on dairies consistently improves feeder calf value (Cabrera, 2022; McCabe et al., 2022). Some dairy producers have begun using beef embryos to add additional value to resulting calves (Pereira et al., 2022). However, the value of calves of straightbred beef genetics in the dairy system is not fully known and could be affected by calfhood management differences between the dairy management system and beef management system.

Additionally, maternal dairy genetics are a source of variation in beef × dairy populations. Jersey genetics have a smaller mature size and correspondingly lesser rate of gain and carcass weight than Holstein genetics (Anderson et al., 2007; Bjelland et al., 2011; Jaborek et al., 2023). Although Lehmkuhler and Ramos (2008) directly compared Holstein and Jersey steers, direct comparison of the terminal characteristics of Holstein and Jersey maternal genetics is not robustly reported in literature with a sire-controlled model for beef × dairy crossbred cattle. Additionally, few studies have evaluated feedlot and carcass performance of beef and beef × dairy cattle simultaneously. Under common management, differences in feedlot and carcass performance of divergent breed types could be minimized. The objective of this experiment was to evaluate the effect of the proportion of Angus, Holstein, and Jersey genetics and the effect of calf management system on the growth and carcass performance of feedlot cattle.

Materials and Methods

Animal care and use

All cattle were managed according to protocol 19048-05 and SOP022 approved by Texas Tech University Animal Care and Use Committee. The experiment was conducted at the Texas Tech University Beef Center approximately 11 km east of New Deal, TX.

Description of treatments

The objective of this experiment was to evaluate the effect of the proportion of Angus, Holstein, and Jersey genetics and the effect of calf management system on the growth and carcass performance of feedlot cattle. Treatments were considered combinations of calfhood management system and calf genetic composition. Therefore, treatments were applied before cattle were received for this finishing study, and individual animal was considered the experimental unit. The study was designed using genetic control because tissue-, cellular-, and metabolite-level responses were measured to understand the potential mechanisms of performance differences observed with limited replication.

All treatment groups were sired by a single Angus bull (G A R Momentum, American Angus Association registration number 17354145). G A R Momentum was bred to Holstein, Jersey, and commercial beef cows by artificial insemination. The commercial beef cows were Angus-based, black, and polled. Resulting Angus × Holstein (A × H) and Angus × Jersey (A × J) calves were born on commercial dairies and were raised on a calf ranch (Hobbs, NM); resulting Angus × commercial beef (A × B) calves were raised with their dam on range at the Texas Tech University Beef Center. To test the effect of replacing maternal dairy genetics with beef genetics, an embryo transfer model was used. Embryos were produced by in vitro fertilization (SimVitro HerdFlex; J. R. Simplot Company; Boise, ID). Oocytes were aspirated from ovaries of commercial black, polled, Angus-based beef cows immediately after slaughter. Semen from G A R Momentum was used to fertilize oocytes, and embryos were frozen before transfer into Holstein and Jersey recipient females. Resulting beef calves from Holstein (H ET) and Jersey (J ET) cows were born on commercial dairies and were raised on a calf ranch (Hobbs, NM). In summary, the five treatments for this feedlot trial are listed below:

Angus × commercial beef (A × B) steers and heifers raised with their dam on range (n = 14);

Angus × commercial beef steers and heifers gestated by Holstein cows (H ET) and raised on a calf ranch (n = 15);

Angus × commercial beef steers and heifers gestated by Jersey cows (J ET) and raised on a calf ranch (n = 16);

Angus × Holstein (A × H) steers and heifers born to Holstein dams and raised on a calf ranch (n = 15); and

Angus × Jersey (A × J) steers and heifers born to Jersey dams and raised on a calf ranch (n = 16).

Pretrial management and study initiation

Pretrial management and calfhood performance were described by Fuerniss et al. (2023). Briefly, dams of A × B calves were managed on rangelands with no less than 1.29 hectares per cow at The Texas Tech University Beef Center and surrounding pastures. Free-choice mineral was offered, and supplemental hay (Bothriochloa bladhii) was provided from calving through approximately 30 d postpartum. At 200 d of age, calves and their dams were moved into dry lot pens and calves were creep fed grower diet (formulation in Table 1) out of fence-line concrete bunks. Calves were weaned at an average age of 205 d, and cows were removed from adjacent dry lot pens 5 d after weaning.

Table 1.

Formulated ingredient inclusion and chemical analysis of experimental diets on dry matter basis

| Growing diet | Transition diet 1 | Transition diet | Transition diet | Finishing diet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formulated DM inclusion, % | |||||

| Steam-flaked corn | 0.00 | 10.64 | 21.28 | 31.91 | 42.65 |

| Dry-rolled corn | 40.90 | 33.18 | 25.45 | 17.73 | 10.00 |

| Sweet Bran | 25.00 | 26.25 | 27.50 | 28.75 | 30.00 |

| Alfalfa hay | 20.00 | 15.00 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Cotton burrs | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 5.00 |

| Yellow grease | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 |

| Calcium carbonate | 1.10 | 1.23 | 1.35 | 1.48 | 1.60 |

| Urea | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.75 |

| Supplement1 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Chemical analysis | |||||

| n, dry matter2 | 23 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 62 |

| n, chemical analysis3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Dry matter, % | 77.0 ± 1.55 | 75.8 ± 1.73 | 74.7 ± 1.75 | 75.5 ± 0.96 | 74.7 ± 1.46 |

| Crude protein, % | 14.4 ± 0.59 | 14.8 | 15.3 | 15.9 | 16.2 ± 0.51 |

| Acid detergent fiber, % | 23.3 ± 4.79 | 15.3 | 14.2 | 11.4 | 12.1 ± 1.27 |

| Neutral detergent fiber, % | 34.6 ± 7.93 | 26.8 | 26.3 | 24.8 | 22.4 ± 1.05 |

| Crude fat, % | 3.5 ± 0.54 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 6.1 ± 0.48 |

| Total digestible nutrients, % | 69.5 ± 5.01 | 77.6 | 83.9 | 87.5 | 86.7 ± 1.45 |

| NEM, Mcal/kg | 1.62 ± 0.157 | 1.87 | 2.07 | 2.16 | 2.15 ± 0.043 |

| NEG, Mcal/kg | 1.01 ± 0.139 | 1.23 | 1.39 | 1.50 | 1.48 ± 0.039 |

1Supplement included 67.754% ground corn, 15.000% NaCl, 10.000% KCl, 3.760% Urea, 0.986% Zinc sulfate, 0.750% Rumensin 90 (Elanco, Greenfield, IN), 0.506 Tylan 40 (Elanco), 0.500% Endox (Kemin Industries, Des Moines, IA), 0.196% Copper sulfate, 0.167% Manganese oxide, 0.157% vitamin E (500 IU/g), 0.125% selenium premix (0.2% Se), 0.083% iron sulfate, 0.010% vitamin A (1,000,000 IU/g), 0.003% ethylenediamine dihydroiodide, and 0.002% cobalt carbonate on dry matter basis.

All calves raised through calf ranches (A × H, A × J, H ET, J ET, and H) were separated from their dam at birth and given 3.78 L of colostrum. Calves were housed in individual hutches and offered ad libitum water, ad libitum starter feed, and 2.84 L of milk twice per day. Starter feed analyzed 87% dry matter, 22% crude protein, and 1.61 Mcal NEG/kg. Milk consisted of pasteurized whole milk adjusted to 13% dry matter with supplemental 24% protein and 12% fat milk replacer (Calva Products; Acampo, California). Weaning was completed by approximately 65 d of age, and calves were offered the same starter diet and comingled across treatment groups (approximately eight calves per pen). At approximately 85 d of age, calves were moved to larger group pens (approximately 50 calves per pen) and offered a grower diet out of fence-line feed bunks. The calf grower diet was fed as a total mixed ration and included barley silage, corn gluten feed, ground corn, cotton burrs, and supplement providing vitamins and minerals and provided 73.7% dry matter, 15.7% crude protein, and 1.28 Mcal NEG/kg. At approximately 110 d of age, calves were moved to larger pens (approximately 100 calves per pen) and offered a lower-energy density diet (0.90 Mcal NEG/kg). At approximately 235 d of age (BW of 218 ± 43.5 kg), calves were transported to the Texas Tech University Beef Center.

Upon feedlot arrival, all cattle were group housed in soil-surface pens with south-facing concrete aprons along fence-line feed bunks. A minimum of 30.5 m2 of pen space with 7.5 m2 of shaded area were allotted per animal. Cattle were given unique visual and half duplex electronic IDs (Allflex USA, Irving, TX) and treated for internal and external parasites (Valbazen and Dectomax Pour-On; Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ). All cattle were vaccinated and boostered against respiratory (Bovi-Shield Gold 5; Zoetis; and Bovilis Once PMH IN; Merck, Rahway, NJ) and clostridial diseases (Bovilis Vision 7 Somnus with Spur; Merck).

The cattle used in this study were born during a single spring calving season as described by Fuerniss et al. (2023). The mating system used by Fuerniss et al. (2023) was designed to minimize potential impacts of seasonal climate factors during calfhood by controlling date of birth. However, divergence in calfhood growth performance and the addition of younger J ET calves to even samples size prevented this feedlot finishing trial from simultaneously controlling cattle age, season, and BW at feedlot placement. Because of these constraints, this feedlot finishing trial was designed with constant days on feed (approximately 196 d) and similar initial body weight. Before the trial began, cattle were penned by treatment group, offered grower diet ad libitum, and weighed (approximately every 21 d) to estimate when mean 4% shrunk body weight (SBW) of the treatment group was approximately 300 kg. Cattle reached SBW of approximately 300 kg from late fall of 2021 to early spring of 2022 in the order of A × B, A × H, H ET, A × J, and J ET. On average, cattle started on trial on January 11th of 2022 (SD = 76.6 d) with SBW of 301 ± 32.0 kg.

Cattle and feeding management

On trial day 0, cattle were implanted in the right ear with Synovex One Feedlot (Zoetis; 200 mg trenbolone acetate and 28 mg estradiol benzoate), and hip height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm to calculate frame score (Beef Improvement Federation, 2021). From days 0 to 27, cattle remained penned by treatment and were fed in concrete feed bunks while transitioning from the grower diet to the final fishing diet. Beginning on day 0, three transition diets were fed for 7 d each, and the finishing diet was fed from days 21 to 27 (formulations reported in Table 1). Diets were mixed for a minimum of 5 min with tractor PTO at a minimum of 450 RPM before delivery by a tractor-pulled mixer (Rotomix 84-8; Rotomix, Dodge City, KS; scale readability ± 0.454 kg). Feed bunks were evaluated daily approximately 15 min before sunrise. Feed calls were adjusted to achieve less than 0.113 kg of dry feed remaining in the bunk per animal from the previous feeding. Dry matter intake for days 0 to 27 was not reported because the observational unit (pen) was not replicated within treatment and did not match the experimental unit (individual animal).

By day 28, cattle were adapted to the finishing diet, comingled across treatments, and assigned to one of three pens to measure individual finishing diet intake with SmartFeed bunks (C-Lock, Rapid City, SD). Pens were filled temporally (no more than 21 d to fill pen), and no more than 32 animals were assigned to each pen. Each pen included steers and heifers and approximately half straightbred beef cattle and half dairy-influenced cattle. A ratio of approximately 1 feeder per 8 animals was maintained throughout the study. Fresh feed was delivered once daily at sunrise to achieve no less than 5 kg remaining in each feeder the following morning.

Duplicate feed samples were collected weekly from bunks immediately after feeding. One sample was dried in duplicate in a forced air oven at 100 °C for 24 h to determine DM content of the diet. Weekly DM values were used to adjust as-fed deliveries and calculate dry matter intake. The second sample was held at −80 °C until the conclusion of the study when weekly samples of the growing, each transition, and finishing diets were composited by month and analyzed for chemical composition by a commercial laboratory (Table 1; ServiTech, Amarillo, TX).

Body weight and intensive sampling

Body weight was measured using a platform scale to the nearest 0.45 kg at days 0, 28, 56, 84, 112, 140, and 168, and at shipment for slaughter which occurred at 195 ± 1.4 d. Cattle were weighed at 0600 hours without feed or water restriction except for the final body weight for which cattle were held without feed for 12 h. A 4% shrink was applied to all weights. Subsets of steers from each treatment were selected for more intensive sampling to assess mechanistic responses related to performance. On day 0, a subset of N = 43 steers (A × B, n = 7; H ET, n = 6; J ET, n = 8; A × H, n = 7; A × J, n = 7) with SBW closest to 300 kg were identified for repeated blood collection.

Serum metabolites

Blood was collected from the left jugular vein of selected steers on days 0, 56, 112, and 168 of the trial after SBW was recorded. Blood was collected into 2 nonadditive 10 mL glass tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and allowed to clot for 48 h at 4 °C. Glass tubes were centrifuged at 1,250 × g at 4 °C for 25 min. Sera from duplicate tubes were collected by transfer pipet, composited, and aliquoted in 1.5 mL volumes for storage at −80 °C. Sera was subsequently used to quantify circulating concentration of insulin, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), glucose, nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), and urea nitrogen (SUN) using colorimetric assays. For all assays, serum samples were allowed to thaw overnight at 4 °C. Samples were assigned to assay plates by randomization across treatments and experimental days. Optical density was determined using a spectrophotometer (BioTek Epoch 1081299, Santa Clara, CA) for all assays. All standard curves were fit using a four-parameter logistic curve. Standard curves, negative controls, and internal standards were included on every assay plate.

Circulating IGF-1 was quantified using a commercial ELISA kit (Quantikine Human IGF-I ELISA, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as validated by Moriel et al. (2012). Samples were diluted 100× using diluent provided by the manufacturer, and the concentration of the standard curve ranged from 0.125 to 8 ng/mL for an effective range of detection from 12.5 to 800 ng/mL. Assay procedures were completed following manufacturer protocols. Optical density was read using wavelengths of 450 nm and 540 nm, and the measured optical density read at 540 nm was subtracted from the optical density at 450 nm to correct for background. Intra-assay CV was 3.93%, and inter-assay CV was 7.19%. All samples were assayed in duplicate and rerun if the coefficient of variation exceeded 10%.

Circulating insulin was quantified using a commercial ELISA kit (Bovine Insulin ELISA 80-INSBO-E01, ALPCO, Salem, NH) as described by Bernhard et al. (2012) and Stokes et al. (2019). The concentration of the standard curve ranged from 0.25 to 6.0 ng/mL. Two samples provided by the manufacturer of known concentration (0.636 and 3.818 ng/mL) were included in addition to an internal standard of unknown concentration. Assay procedures were completed following manufacturer protocols. Microplate shaker speed was set to 800 rpm. Optical density was read using wavelength of 450 nm. Intra-assay CV was 3.56%, and inter-assay CV was 5.36%. All samples were assayed in duplicate and rerun if the coefficient of variation exceeded 10%.

Circulating glucose was quantified using a commercial colorimetric kit (Autokit Glucose, FUJIFILM, Lexington, MA) modified for a 96-well format as previously described (Bernhard et al., 2012; Sanchez et al., 2014). The concentration of the standard curve ranged from 25 to 200 mg/dL. The working solution was prepared the same day as assays were performed by mixing the color reagent and buffer solution according to manufacturer protocol and storing at 4 °C without exposure to light. Samples (2 µL) were added to a 96-well, flat-bottom plate. Then, 300 µL of the working solution was added to each well and immediately incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. Optical density was read using wavelengths of 505 and 600 nm, and the measured optical density read at 600 nm was subtracted from the optical density at 505 nm to correct for background. To minimize variation of incubation time, only half of each 96-well plate (48 wells) was used. Intra-assay CV was 5.34 %, and inter-assay CV was 6.45%. All samples were assayed in duplicate and rerun if the coefficient of variation exceeded 10%.

Circulating NEFA concentration was quantified using a commercial colorimetric kit (NEFA-HR, FUJIFILM, Lexington, MA) as described by Smith et al. (2019). The concentration of the standard curve ranged from 0.03125 to 1.0 mEq/L. The working solution was prepared the same day as assays were performed by mixing the color reagent and buffer solution according to manufacturer protocol and storing at 4 °C. Samples (5 µL) were added to a 96-well, flat-bottom plate. Next, 200 µL of reagent A (0.53 U/mL acyl-CoA synthetase, 0.31 mmol/L coenzyme A, 4.3 mmol/L adenosine 5-triphosphate disodium salt, 1.5 mmol/L 4-aminoantipyrine, 2.6 U/mL acyl-CoA oxidase, 0.062% sodium azide in phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) was added to each well and immediately incubated for 5 min at 37 °C before reading optical density at 550 nm. Then, 100 µL of reagent B (12 U/L Acyl-CoA oxidase and 14 U/L peroxidase in 2.4 mmol/L 3-Methyl-N-Ethyl-N-(β-Hydroxyethyl)-Aniline) was added to each well and immediately incubated for 10 min at 37 °C before reading optical density again at 550 nm. The final absorbance was calculated by subtracting two-thirds of the first reading from the second reading. Intra-assay CV was 5.04%, and inter-assay CV was 7.10%. All samples were assayed in triplicate and rerun if the coefficient of variation exceeded 10%.

Circulating SUN concentration was quantified using a commercial colorimetric kit (Urea Nitrogen-0580; STANBIO Laboratory, Boerne, TX) with modifications to the protocol described by Smith et al. (2019). The concentration of the standard curve ranged from 0.3125 to 25 mg/dL. In 1.5-mL snap-top tubes, 5 µL of sample was combined with 250 µL of color reagent and 500 µL of sulfuric acid reagent. After mixing by vortexing, tubes were held in a floating tube rack and placed in a 95- to 99-°C water bath for 14 min. Tubes were immediately transferred to an ice bath for 5 min. After vortexing, 200 µL was plated in a 96-well flat-bottom plate with absorbance read at 520 nm. Intra-assay CV was 2.91%, and inter-assay CV was 9.89%. All samples were assayed in triplicate and rerun if the coefficient of variation exceeded 10%.

Carcass evaluation

On the scheduled day of slaughter, cattle were weighed at approximately 0400 hours before being transported 161 km to a commercial beef processing plant. Cattle were slaughtered approximately 5.5 h after SBW was recorded. Individual identity was retained across the slaughter floor. Upon evisceration, livers were scored based on the system described by Brown and Lawrence (2010). Kidney, pelvic, and heart fat (KPH) was visually estimated and recorded as a percentage of the carcass by a trained evaluator; hot carcass weight (HCW) was also recorded. After 96 h of chilling, carcasses were ribbed between the 12th and 13th ribs, and allowed to bloom for approximately 30 min before being presented for USDA grading. Assigned USDA quality grade was recorded along with 12th-rib fat thickness, longissimus muscle area, and marbling score. Yield grade was calculated by the current USDA yield grade equation (USDA AMS, 2017). For the calculation of the dressing percentage, a 4% shrink was applied to BW, and HCW was presented with KPH.

Energetic calculations

Since the finishing phase started at approximately a constant weight, cattle were fed for approximately constant days, and differences were expected in mature size, calculations were completed to summarize composition and predict energetic efficiency. From carcass data, empty body fat percentage was calculated using the equation of Guiroy et al. (2001). Mature size (adjusted final body weight; AFBW) was estimated as the SBW at which empty body fat percentage would equal 28.0% using the equation of Guiroy et al. (2001); no adjustment was made across breed types to account for potential differences in the relationship between empty body weight (EBW) and HCW. Retained energy was calculated using the medium-frame steer equation developed by Garrett (1980) that was incorporated into the 1984 Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. Retained energy was considered equivalent to net energy for gain (NEG). Net energy for maintenance (NEM) was calculated as a function of metabolic body weight (SBW0.75) as described by Lofgreen and Garrett (1968). Performance-adjusted NEM and NEG were calculated by a quadratic equation using DM intake, energy for maintenance, and energy for gain by the method of Zinn and Shen (1998). Required NEM was back calculated per kg of SBW0.75 using tabular net energy values (NASEM, 2016) as fixed values for dietary NEM and NEG, calculated retained energy, dry matter intake, and mean metabolic body weight. Back calculated required NEM was expressed as a ratio relative to 0.077 Mcal NEM required per kilogram SBW0.75 as expected for straightbred beef cattle.

Feed efficiency was estimated each time body weight was measured to describe feed efficiency of individual animals more precisely throughout the finishing period. A quadratic regression and derivative were used to take advantage of repeated measures and estimate instantaneous gain:feed ratio. For each animal, the relationship between cumulative feed consumption and SBW was regressed with a quadratic term from day 28 until shipment for slaughter. Instantaneous feed efficiency was determined for each recorded SBW as the slope (first derivative) of the quadratic regression.

Differences in mature size were expected based on biological type. Because the experiment was designed to start cattle at a common weight and slaughter after common days on feed, differences in cattle composition were expected at slaughter. Correspondingly, differences in composition of gain were anticipated because composition of gain of feedlot cattle is related to chemical maturity (Owens et al., 1995). Therefore, feed efficiency was evaluated relative to body composition. To accomplish this, a scaling approach was used that was conceptually like the suggestion of Tylutki et al. (1994) that was adopted by the 1996 NRC. The equivalent shrunk body weight equation of the 1996 NRC used the relationship of SBW and mature size as a proportion to adjust composition of gain and energy required for gain for chemical maturity. In this study, the same ratio of SBW to mature size (AFBW) was used to scale feed efficiency to approximated degree of maturity. Recorded SBW were converted to a percentage of AFBW, and feed efficiency was regressed on SBW as a percentage of AFBW.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022). Functions from the dplyr package (Wickham et al., 2022) and plyr package (Wickham, 2011) were used for all data merging and calculations. Assumptions underlying statistical tests (normality, homoscedasticity, and freedom from outliers) were tested using functions of the rstatix package (Kassambara, 2021). When data failed to meet the assumption of normality, log transformation was used. Linear mixed models were fit using the lme4 package of R (Bates et al., 2015). Models for feedlot growth performance and carcass traits included fixed effects of treatment and sex with pen as a random effect. Liver abscess prevalence was evaluated as a binary trait with logistic regression. The log-transformed ratio of gain to feed at each SBW measured was regressed against SBW or SBW as a percentage of mature size (AFBW). Fixed effects included breed type, weight, the interaction of breed type and weight, a quadratic term for weight, and sex. Individual was included as a random effect to account for repeated measures and lack of independence. Models for serum metabolites included fixed effects of treatment, experiment day, and the interaction of treatment and day as well as the experimental unit as a random effect to account for repeated measures and lack of independence.

Effects were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Kenward–Roger approximation of denominator degrees of freedom. Pairwise comparisons were protected by ANOVA significance, and Tukey adjustment was used for multiple comparisons. Data were presented as estimated marginal means calculated using the emmeans package of R (Lenth, 2022). To account for unbalanced proportions of sex within treatment, all means were presented on a steer base and an adjustment was given for heifers. Statistical significance was evaluated compared with α of 0.05. When 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10, tendencies were considered. Visualizations were built in R using the ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), cowplot (Wilke, 2020), and ggpubr packages (Kassambara, 2020).

Results

Live performance

By design, no difference in SBW was observed among treatments on day 0 (P = 0.36; Table 2); mean SBW across all treatments was 301 kg. On day 0, A × B cattle were younger (P < 0.05) than all other Angus-sired cattle by an average of 66 d. Among calves born to Jersey cows, J ET claves were 42 d younger than A × J calves (P < 0.05). Conversely, H ET calves were 21 d older than A × H calves at trial day 0 (P < 0.05). Frame score was greatest for A × H crossbred cattle compared to all other treatments (P < 0.05). Straightbred beef cattle had the smallest frame size, but frame size of A × B and J ET cattle was not different from that of A × J cattle (P > 0.05). Pretrial SBW per day of age was greatest for A × B cattle, least for A × J cattle, and intermediate for other treatment groups (P < 0.05). Similarly, average daily gain was greatest for A × B cattle, least for A × J cattle, and intermediate for other treatment groups during the first 28 d (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Estimated marginal means adjusted to a base of all steers for pretrial characteristics and growth performance from days 0 to 27

| Treatment1 | Heifer adjustment | SEM2 | P Value3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A × B | H ET | J ET | A × H | A × J | Sex | Treatment | |||

| n | 14 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 16 | ||||

| n, steers | 9 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| n, heifers | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Day 0, days of age | 233d | 302b | 285c | 281c | 326a | −3 | 4.8 | 0.46 | <0.01 |

| Frame score4 | 4.5bc | 4.0c | 4.4bc | 5.7a | 4.8b | +0.4 | 0.21 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Day 0 SBW, kg5 | 316 | 314 | 295 | 311 | 303 | −14 | 9.3 | 0.06 | 0.36 |

| Day 0 SBW per day of age, kg | 1.36a | 1.04b | 1.04b | 1.10b | 0.93c | −0.04 | 0.028 | 0.09 | <0.01 |

| Day 28 SBW, kg5 | 387a | 375ab | 348bc | 364abc | 339c | −16 | 9.9 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| Average daily gain, kg | 2.54a | 2.18ab | 1.87b | 1.90b | 1.32c | −0.06 | 0.113 | 0.50 | <0.01 |

1A × B was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow; H ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Holstein cow; A × H was progeny of Angus bull × Holstein cow; J ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Jersey cow; A × J was progeny of Angus bull × Jersey cow.

2Largest standard error of treatment means.

3Tested as the ANOVA significance for the main effect.

4Calculated for heifers as Frame Score = −11.7086 + (0.1859 × Ht) − (0.0239 × Age) + (0.0000146 × Age2) + (0.0000299 × Ht × Age) and for steers as Frame Score = −11.548 + (0.1920 × Ht) − (0.0289 × Age) + (0.00001947 × Age2) + (0.0000131 × Ht × Age), where Age = days of age and Ht = hip height in cm.

5Body weight shrunk 4%.

a,b,cMeans without common superscript differ by pairwise comparisons with Tukey adjustment (P < 0.05).

Feedlot growth performance was reported in Table 3 for the time during which feed intake was recorded individually (day 28 until shipment for slaughter). The final SBW was similar among the straightbred beef cattle (A × B, H ET, and J ET) and A × H cattle (P > 0.05). Compared to the average of all other treatment groups, ×J cattle had lighter final SBW by 68 kg (P < 0.050). Similar to final SBW, A × J cattle had lesser average daily gain than A × B, J ET, and A × H cattle by 14% (P < 0.05); average daily gain was intermediate for H ET cattle but not different from any other treatment (P > 0.05). The A × J cattle consumed less DM than A × B cattle (P < 0.05) while all other treatment groups were intermediate for DM intake (P > 0.05). Feed efficiency was greater for J ET cattle compared to A × J cattle (P < 0.05) while feed efficiency was similar for all other treatment groups. Feed efficiency was 8.8% greater for J ET cattle compared with A × J cattle. In summary, no differences were detected between H ET and A × H cattle for feedlot growth performance traits (P > 0.05); however, J ET cattle were faster growing (P < 0.05) and more efficient than A × J cattle (P < 0.05). No differences were detected between straightbred beef cattle for feedlot growth performance traits (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Estimated marginal means from day 28 until shipment for slaughter adjusted to a base of all steers for feedlot growth performance while individual feed intake was recorded

| Treatment1 | Heifer adjustment | SEM2 | P Value3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A × B | H ET | J ET | A × H | A × J | Sex | Treatment | |||

| n | 14 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 16 | ||||

| n, steers | 9 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| n, heifers | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Days on feed | 195 | 196 | 196 | 193 | 193 | ||||

| Days individually fed4 | 167 | 168 | 168 | 165 | 165 | ||||

| Day 28 SBW, kg5 | 387a | 373ab | 346bc | 361abc | 337c | −16 | 10.5 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| Final SBW, kg5 | 667a | 636a | 624a | 653a | 577b | −51 | 14.0 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Average daily gain, kg | 1.68a | 1.56ab | 1.68a | 1.73a | 1.46b | −0.21 | 0.051 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Daily DM intake, kg | 10.58a | 9.85ab | 9.76ab | 10.09ab | 9.21b | −0.51 | 0.306 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Gain:feed | 0.159ab | 0.159ab | 0.173a | 0.172ab | 0.159b | −0.014 | 0.0043 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

1A × B was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow; H ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Holstein cow; A × H was progeny of Angus bull × Holstein cow; J ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Jersey cow; A × J was progeny of Angus bull × Jersey cow.

2Largest standard error of treatment means.

3Tested as the ANOVA significance for the main effect.

4Days on feed when individual intake was measured.

5Body weight shrunk 4%.

a,b,cMeans without common superscript differ by pairwise comparisons with Tukey adjustment (P < 0.05).

Carcass performance

Hot carcass weight of A × J was 55 kg lighter than the average of all other treatments (P < 0.05; Table 4). Compared with A × J, J ET had greater HCW by 42 kg (P < 0.05). The dressing percentage was greatest for H ET cattle, least for A × J cattle, and intermediate for all other treatment groups (P < 0.05). Within both Holstein and Jersey dams, the use of a beef embryo compared with artificial insemination to an Angus bull increased the dressing percentage more than 2.0 percentage points (P < 0.05). However, no treatment difference was detected for longissimus muscle area across treatment means that ranged 4.0 cm2 (P = 0.40). Fat thickness was greatest for carcasses of straightbred beef genetics and least for A × J carcasses (P < 0.05); fat thickness of A × H carcasses was intermediate but not different from other treatments (P > 0.05). Compared with cattle born at a dairy, A × B cattle had lesser estimated KPH fat by approximately 0.6 percentage points. A tendency for a difference in marbling score was observed (P = 0.08) where H ET tended to have greater marbling scores than A × J carcasses (P < 0.10) while all other treatments were intermediate and similar (P > 0.10). The mean marbling score across all treatments was greater than 700, the minimum marbling score for USDA Prime. Across all treatments, 17% of livers were abscessed with no difference detected in liver abscess distribution between treatments (P = 0.20).

Table 4.

Estimated marginal means adjusted to a base of all steers for carcass characteristics of feedlot cattle after 195 ± 1.4 d on feed

| Treatment1 | Heifer adjustment | SEM2 | P Value3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A × B | H ET | J ET | A × H | A × J | Sex | Treatment | |||

| n | 14 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 16 | ||||

| n, steers | 9 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| n, heifers | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Slaughter age, d | 426d | 497b | 476c | 475c | 518a | −3 | 4.4 | 0.46 | <0.01 |

| HCW, kg | 422a | 417a | 401a | 416a | 359b | −33 | 8.7 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Dressing percentage | 63.3b | 65.8a | 64.1b | 63.6b | 61.7c | −0.1 | 0.37 | 0.66 | <0.01 |

| Longissimus muscle area, cm2 | 94.0 | 95.1 | 98.0 | 98.0 | 94.7 | −4.7 | 2.10 | 0.01 | 0.40 |

| Fat thickness, cm | 1.97a | 1.82a | 1.85a | 1.56ab | 1.36b | +0.12 | 0.131 | 0.25 | <0.01 |

| KPH fat, %4 | 2.1d | 3.2a | 2.5cd | 2.6bc | 2.9ab | +0.1 | 0.13 | 0.28 | <0.01 |

| Calculated USDA yield grade | 3.7a | 3.7a | 3.3ab | 3.2ab | 2.7b | +0.1 | 0.20 | 0.54 | <0.01 |

| Marbling score5 | 714xy | 782x | 683xy | 684xy | 661y | +30 | 36.6 | 0.31 | 0.08 |

| Abscessed livers, % | 7.3 | 26.3 | 12.9 | 33.2 | 6.2 | +2.4 | 12.1 | 0.77 | 0.20 |

1A × B was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow; H ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Holstein cow; A × H was progeny of Angus bull × Holstein cow; J ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Jersey cow; A × J was progeny of Angus bull × Jersey cow; H was straightbred Holstein.

2Largest standard error of treatment means.

3Tested as the ANOVA significance for the main effect.

4Kidney, pelvic, and heart fat estimated by visual observation.

5Small00 = 400, Modest00 = 500.

a,b,cMeans without common superscript differ between treatments by pairwise comparisons with Tukey adjustment (P < 0.05).

x,yMeans without common superscript differ between treatments by pairwise comparisons with Tukey adjustment (0.05 ≤ P < 0.10).

Energy and feed efficiency calculations

Calculated empty body fat was least for A × J carcasses and greatest for A × B and H ET carcasses (P < 0.05; Table 5); other treatments were intermediate but not different (P > 0.05). On average, H ET cattle had EBF that was 1.7 percentage points greater than that of A × H, and J ET cattle had EBF that was 3.3 percentage points greater than that of A × J. No difference was detected among treatments in AFBW (P = 0.22), and calculated AFBW of straightbred beef cattle ranged less than 10 kg. Similarly, no difference was detected among treatments for FSBW as a percentage of AFBW (P = 0.23). All outcome variables of performance-adjusted net energy calculations (dietary net energy for maintenance, dietary net energy for gain, observed to expected dietary net energy for maintenance, observed to expected dietary net energy for gain, and observed to expected net energy for maintenance) were similar among treatments (P ≥ 0.20).

Table 5.

Estimated marginal means adjusted to a base of all steers for body-composition-adjusted final weight and performance-adjusted dietary net energy

| Treatment1 | Heifer adjustment | SEM2 | P Value3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A × B | H ET | J ET | A × H | A × J | Sex | Treatment | |||

| n | 14 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 16 | ||||

| n, steers | 9 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| n, heifers | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| EBF, %4 | 35.8a | 35.1a | 34.4ab | 33.4ab | 31.1b | +0.7 | 1.0 | 0.42 | <0.01 |

| AFBW, kg5 | 522 | 520 | 512 | 549 | 502 | −58 | 16.5 | <0.01 | 0.22 |

| FSBW, % of AFBW6 | 128 | 124 | 124 | 121 | 117 | +4 | 4.0 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| Dietary net energy, Mcal/kg DM for maintenance7 | 2.20 | 2.18 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 2.12 | −0.07 | 0.045 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Dietary net energy, Mcal/kg DM for gain7 | 1.52 | 1.50 | 1.55 | 1.56 | 1.45 | −0.06 | 0.040 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Observed:expected dietary net energy, Mcal/kg for maintenance8 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 0.99 | −0.03 | 0.021 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Observed:expected dietary net energy, Mcal/kg for gain8 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 0.99 | −0.04 | 0.027 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| NEM required: expected9 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 1.08 | +0.101 | 0.067 | 0.07 | 0.24 |

1A × B was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow; H ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Holstein cow; A × H was progeny of Angus bull × Holstein cow; J ET was progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Jersey cow; A × J was progeny of Angus bull × Jersey cow; H was straightbred Holstein.

2Largest standard error of treatment means.

3Tested as the ANOVA significance for the main effect.

4Empty body fat calculated using equation of Guiroy et al. (2001).

5Adjusted final body weight calculated using equation of Guiroy et al. (2001).

6Final live weight shrunk 4%.

7Performance-adjusted net energy calculated using equation of Zinn and Shen (1998).

8Ratio of performance-adjusted net energy to tabular net energy values.

9Ratio of net energy for maintenance (NEM) required (using retained energy, tubular net energy values, dry matter intake, and mean metabolic body weight) to expected value of 0.077 Mcal/kg of metabolic body weight.

a,bMeans without common superscript differ between treatments by pairwise comparisons with Tukey adjustment (P < 0.05).

Feed efficiency adjusted for SBW was evaluated by breed type (either straightbred beef or beef × dairy) and summarized in Figure 1. When feed efficiency was regressed against SBW (Figure 1A), an interaction was observed between breed type and SBW (P = 0.03). As SBW increased from 350 to 600 kg, the difference between feed efficiency of straightbred beef cattle and crossbred dairy cattle was minimized. However, when feed efficiency was regressed against SBW as a percentage of AFBW (Figure 1B), a constant magnitude of difference between feed efficiency of straightbred beef cattle and crossbred dairy cattle was observed as indicated by lack of interaction between breed type and SBW as a percentage of AFBW (P = 0.50). Regardless if feed efficiency regressed against SBW was corrected for percentage of AFBW, G:F became lesser at a decreasing rate as SBW increased; this was represented in the models with negative linear terms (P < 0.01) and positive quadratic terms (P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Ratio shrunk body weight gain to feed consumed across different proportions of mature size for N = 76 steers and heifers. Instantaneous gain:feed was calculated using the first derivative of the relationship between cumulative dry matter intake and body weight and was regressed against body weight as a percentage of adjusted final body weight calculated using equation of Guiroy et al. (2001). Angus × Beef cattle (n = 45) included the progeny Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow, the progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Holstein cow and progeny of Angus bull × commercial Angus-influenced cow gestated by Jersey cow. Angus × Beef cattle (n = 31) included the progeny of Angus bull × Holstein cow and the progeny of Angus bull × Jersey cow.

Sera hormones and metabolites

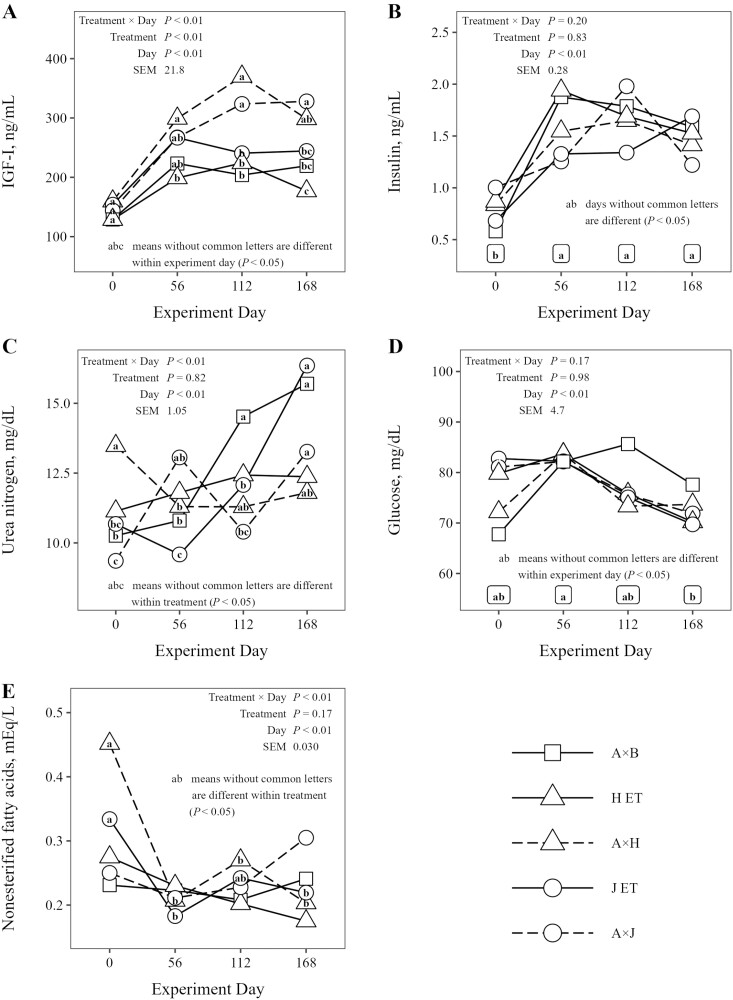

An interaction between treatment and experiment day was detected for IGF-I concentration (P < 0.01; Figure 2A). On day 0, no difference was detected in circulating IGF-I concentration (P > 0.05). The concentration of circulating IGF-I increased for all treatment groups after day 0, and cattle with half dairy genetics had greater circulating IGF-I concentration by day 112 than straightbred beef cattle (P < 0.05). The concentration of IGF-1 remained elevated for dairy-influenced cattle to day 168 when A × J cattle had greater IGF-I concentration than that of straightbred beef cattle (P < 0.05); though, IGF-I concentration of A × H cattle was greater than that of H ET cattle (P < 0.05), no difference was detected in IGF-I concentration among A × H, A × B, and J ET cattle (P > 0.05). Similarly, all treatment groups had greater concentration of insulin at days 56, 112, and 168 compared with day 0 (P < 0.05; Figure 2B). An interaction between treatment and experiment day was detected for serum urea nitrogen concentration (P < 0.01; Figure 2C). Except for A × H cattle, urea nitrogen concentration was least at either day 0 or 56 and greatest at day 112 or 168 (P < 0.05). Urea nitrogen concentration was maximized at day 0 for A × H cattle. Glucose (Figure 2D) and NEFA (Figure 2E) demonstrated similar trends in which greater range in values was observed across treatments at day 0, but no differences between treatments were detected from days 56 to 168 (P > 0.05). Day affected glucose concentration (P < 0.01) where glucose concentration was maximized at day 56 and minimized at day 168 (P < 0.05). Similarly, A × H and J ET cattle had greater circulating NEFA compared with days 56, 112, and 168 (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Measurement of serum IGF-I (A), insulin (B), urea nitrogen (C), glucose (D), and non-esterified fatty acids (E) from of a subset of N = 43 steers collected at experiment days 0, 56, 112, and 168.

Discussion

Influence of calf management system on straightbred beef cattle

Minimal differences in feedlot and carcass performance were observed between calves of straightbred beef genetics (A × B, H ET, and J ET). Factors such as mating type, concentrate feed availability, development of grazing behaviors, housing, exposure to other calves, nurturing from the dam, and weaning age were different between the management systems, but potential differences between straightbred beef in early life were minimized after calves were offered a common diet and grown to SBW of approximately 300 kg. Regardless if straightbred beef cattle were raised by their dam or at a calf ranch, average daily gain, feed intake, feed efficiency, hot carcass weight, USDA Yield Grade, and marbling score were similar when the feeding period was controlled by starting weight and days on feed. Therefore, economically relevant characteristics were not affected by calf management system in this study.

Differences in age at feedlot placement indicated divergent growth rates during calfhood. However, pretrial nutritional differences (which could have allowed for compensatory growth) were not of magnitude to have lasting effects on growth or carcass characteristics (Hogg, 1991; Sainz et al., 1995; Sainz and Paganini, 2004). In previous poultry and human models, nutritional insults must be extreme (such as starvation) to negatively affect skeletal growth and muscle hypertrophy once the animal is realimented (Hansen-Smith et al., 1979; Halevy et al., 2000; (Pophal. et al., 2004)). Differences in calfhood nutrient availability between the calfhood management systems were not this extreme, so it is not surprising that straightbred beef cattle with similar genetics performed similarly in this study. However, small differences in early exposure to concentrated feeds could have contributed to greater KPH fat from carcasses of straightbred beef cattle managed through a calf ranch. Before the rumen is developed, increased concentrate feed consumption results in greater digesta mass in the hindgut (Yohe et al., 2022), and nutrient absorption in the hindgut could potentiate fat depots related to mesenteric and carcass KPH fat. Collectively, differences between straightbred beef calves raised in beef and dairy management systems were minimal.

Breed type effects on feedlot growth performance and carcass traits

Feedlot growth performance was expected to be favorable for straightbred beef-type cattle compared to dairy-influenced cattle based on previous studies (Perry et al., 1991; Perry and Fox, 1997; Vestergaard et al., 2019; Rezagholivand et al., 2021; Foraker et al., 2022a). On average, straightbred beef cattle had 12% greater average daily gain than A × J cattle, but A × H cattle 5% greater average daily gain than straightbred beef cattle. While the magnitude of difference in feedlot growth performance between Angus-sired cattle from Holstein and Jersey dams was expected based on the work of Lehmkuhler and Ramos (2008), the productivity of A × H cattle was greater than that previously reported by Rezagholivand et al. (2021) by 0.4 kg/d and greater than that previously reported by Foraker et al. (2022a) by 0.2 kg/d. Similarly, feed efficiency was similar between straightbred beef cattle and A × H cattle and was greater for A × H than previously reported (Rezagholivand et al., 2021; Foraker et al., 2022a). However, this study was not controlled for body composition, and therefore, energy density of gain confounds interpretation of feedlot growth performance when unadjusted for composition of gain.

The dressing percentage was expected to be favorable for straightbred beef-type cattle compared to dairy-influenced cattle based on previous studies (Kauffman et al., 1976; Nour et al., 1983; Duff and McMurphy, 2007; Foraker et al., 2022a). However, the dressing percentage was poorest for A × J cattle, intermediate for A × H, A × B, and J ET cattle, and greatest for H ET steers. The similarity of the dressing percentage of among A × H, A × B, and J ET cattle could be caused by seasonality. The A × B cattle were slaughtered in late spring before the winter hair coat transitioned to summer hair coat, and the J ET cattle were harvested in late fall as the winter hair coat was growing; hide weight was likely greater causing the dressing percentage of A × B and J ET cattle to be lesser than expected. Carcass weight and fat thickness differences between A × H and A × J carcass was expected based on the work of Lehmkuhler and Ramos (2008); however, A × H and A × J carcasses had approximately 1.0 cm greater fat thickness than reported for Holstien and Jersey steers by Lehmkuhler and Ramos (2008). Collectively, marbling score across all treatment groups (approximately 700) was greater by more than 200 units compared to the national average (470) reported in the 2016 National Beef Quality Audit (Boykin et al., 2017).

Muscularity

Previous research demonstrated that straightbred beef cattle were more muscular than dairy-type cattle when assessed by longissimus muscle area (Nour et al., 1983; Knapp et al., 1989; Perry et al., 1991; Thonney et al., 1991) or muscle-to-bone ratio (Berg and Butterfield, 1966, 1976; Kauffman et al., 1976). Recently, variability in phenotypic expression of muscularity has been observed between beef × dairy contemporaries within feedlot pens (Foraker et al., 2022b). However, no difference is muscularity as assessed by longissimus muscle area was observed between treatments in the current study; in fact, greater range in model-adjusted longissimus muscle area was observed for the main effect of sex compared with treatment.

Others have identified hindquarter muscling to be more variable within cattle populations and to be more closely associated with muscle-to-bone ratio than longissimus muscle area (Kauffman et al., 1976; Tatum et al., 1986a, 1986b; Rathmann et al., 2009; Howard et al., 2014; Foraker et al., 2022b). No measures of red meat yield were assessed in this study aside from USDA yield grade; however, differences in the hypaxial muscle lineages of the chuck and round could have existed and—outside of effects on the dressing percentage—remained unquantified both in this study and in the current US beef industry.

Composition and mature size

As expected, differences were evident in mature size and carcass composition between breed types. Mature weight has been demonstrated to be highly heritable (Bullock et al., 1993), and differences in mature size were expected between the dam breeds used in this study. Mature size of Jersey cows is generally more than 100 kg less than that of Holstein cows or commercial beef cows in the US (Rastani et al., 2001; Anderson et al., 2007; Bjelland et al., 2011; Edwards et al., 2017; Bir et al., 2018). Observations of delayed fattening of straightbred Holsteins compared with straightbred beef cattle (Berg and Butterfield, 1968; Perry et al., 1991) demonstrated that Holstein genetics are later maturing than beef genetics. Based on studies comparing straightbred Jersey and Holstein steers, Jersey steer remain leaner than Holstein steers; as such, Jersey genetics are later maturing that Holstein genetics (Lehmkuhler and Ramos, 2008). Numerically, the A × H cattle in this study had the greatest mature size (47 kg greater than that of A × J cattle) when measured as AFBW using the methods of Guiroy et al. (2001). As expected, numerical differences between calculated mature size of A × H and A × J cattle were approximately half of the magnitude of the expected 100 kg difference in dam mature weight. The A × J cattle were slightly earlier maturing than the straightbred beef cattle. The data set from this study cannot be used to assess heterosis, but the effect of heterosis on mature size described by Zimmermann et al. (2021) could have enabled the A × J cattle to have a similar AFBW to the beef cattle in the present study.

Aside from differences likely related to stress and feedlot acclimation at day 0, similarities of insulin, glucose, and NEFA across treatment groups provided little evidence for the divergence of energy metabolism between treatments. However, SUN findings indicated that cattle were approaching chemical maturity as d progressed. Protein accretion has been negatively associated with SUN was consistently (Heitzman and Chan, 1974; Bryant et al., 2010; Parr et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2018). Additionally, cattle have demonstrated increased SUN concentration as body fat accumulates (Parr et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2019). The concentration of SUN of all treatment groups in this study generally increased from days 0 to 168 as expected with increasing fat deposition and decreasing protein deposition.

The interaction of treatment and experiment day observed for IGF-I concentration identified differences between breed types. Though all treatments had similar IGF-I concentration at day 0, dairy influenced cattle had greater IGF-I concentration than straightbred beef cattle from day 112 to the end of the study. The growth factor IGF-I is associated with the growth hormone pathways (Salmon and Daughaday, 1957; Kaplan and Cohen, 2007) but does not always have a direct association with feedlot growth performance (Abribat et al., 1990; Kerr et al., 1991). However, IGF-I results agree with finding of frame score differences where dairy-influenced cattle had both greater frame size and greater IGF-I concentration. The divergence of circulating IGF-I concentrations could have been caused by the steroidal implant administered of day 0. Steroidal implants stimulate production of IGF-I (Johnson et al., 1998), so the observed interaction of treatment and experiment d could more meaningfully have exposed a potential interaction of breed type and steroidal implant where dairy-influenced cattle appeared to be more sensitive to exogenous hormone. Perry et al. (1991) also observed different levels of response to steroidal implants when administered to either Holstein or beef type steers. Regardless, after receiving a common steroidal implant, cattle with dairy genetics had greater circulating IGF-I concentration than cattle of straightbred beef genetics.

Energy use and efficiency assumptions

While AFBW results revealed logical differences between breed types, accuracy of AFBW depended on accuracy of estimating EBW from HCW. In a review of 46 studies published from 1970 to 2020, Lancaster (2022) found that EBW as a proportion of SBW was 5.5% lesser for dairy than straightbred beef cattle and that HCW as a proportion of EBW was 4.5% lesser for dairy than straightbred beef cattle. Owens et al. (1995) reviewed published relationships between EBW and BW, and the range of predictions of EBW as a percentage of BW was 5%. Collectively, these publications demonstrated the challenge of estimating EBW to link to the compositional work of Lofgreen and Garrett (1968) for energetic calculations. The observed differences of the dressing percentages in this study demonstrated the challenge of using equations without adjustment for breed types.

Accuracy of AFBW also depends on accuracy of estimating empty body fat percentage. The equation to estimate empty body fat percentage from carcass characteristics published by Guiroy et al. (2001) used diverse breed types to formulate the regression equation, including Holstein steers in four of the nine trials included in the compositional data set. Additionally, the Guiroy et al. (2001) equation was recently applied by Galyean et al. (2023) to estimate empty body fat of Holstein steers. Within breed type, the effect of prediction errors is likely minimized compared with comparison across breed types. Some authors have suggested that separate prediction equations should be used for different bred types (Johnson et al., 1997; Priyanto et al., 1997). A breed- or breed-type-specific model would be valuable considering that divergence in relative proportion of fat depots has been shown. Light-muscled, angular cattle have deposited a greater proportion of fat as intermuscular fat (Kauffman, 1978; Dolezal et al., 1993), and cattle of dairy influence had greater KPH fat (Koch et al., 1976; McKenna et al., 2002). Since these fat depots are not included in the equation of Guiroy et al. (2001), empty body fat calculations could have excluded biologically relevant depots. However, robust data has not been published to make potentially needed adjustments.

Adjustment of feed efficiency for composition

A limitation of this study was a lack of control of final carcass composition. Since cattle were started on trial at a similar weight and were on feed for a similar number of days, expected and identified differences in mature size were associated with body composition and observed feed efficiency. While accretion of protein mass is linear relative to EBW across the finishing period, accretion of fat mass is quadratic (Owens et al., 1995). As fat increases as a proportion of live weight gain, energy density of live weight gain is increased and requires greater caloric intake (Webster, 1977). With advancing chemical maturity, feed efficiency becomes poorer because incremental live gain includes more lipid and less water. While observed feed efficiency was greatest for J ET and least for A × J cattle, interpretation of feed efficiency among all treatments is confounded by compositional endpoint since EBF varied almost 5%.

To account for differences in composition, a scaling approach similar to that proposed by Tylutki et al. (1994) and adopted in the 1996 NRC was used to adjust feed efficiency. Expressing BW as a percentage of AFBW approximated chemical maturity. The use of a derivative to calculate instantaneous feed efficiency enabled longitudinally modeling feed efficiency across the feeding period. The resulting adjusted feed efficiency relative to body weight or approximated composition identified Angus × dairy cattle as having poorer feed efficiency than straightbred beef cattle. This was expected based on the work of Garrett (1971), Thompson et al. (1983), and Perry et al. (1991). However, the feed efficiency of Angus × dairy cattle was still more favorable than expected since the 2016 NASEM model described beef × dairy cattle to have 10% increased maintenance energy requirement compared with beef cattle. The inability to detect greater maintenance energy required by beef × dairy crossbreds could be related to calculation of AFBW, and the assumption that the relationship between HCW and EBW is constant using the equation of Garrett et al. (1978). The observed the dressing percentages in this study indicated that the relationship between HCW and EBW is likely not constant; however, limited data have been published to calculate relationships between HCW and EBW across different breed types.

Implications

Feedlot and carcass performance of cattle of straightbred beef genetics were similar regardless if the calf was raised in the traditional beef cow/calf system or if the calf was raised at a calf ranch. Based on greater daily gain and carcass weight, Holstein maternal genetics had greater terminal merit than Jersey maternal genetics. Regardless of dam breed, dairy genetics increased carcass leanness compared with straightbred beef genetics. No differences were observed in longissimus muscle area among beef and beef × dairy cattle when managed in the same system. When adjusted for mature size, beef × dairy cattle had poorer feed efficiency compared straightbred beef cattle. Further research should be designed to evaluate the energetic efficiency and body composition of modern beef × dairy cattle.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the Gordon W. Davis Regents Chair Endowment at Texas Tech University. The authors also express appreciation to Select Sires, Zoetis, Merck Animal Health, Western Cattle Feeders, the Goff family, and the de Graaf family for their support of this research.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AFBW

adjusted final body weight

- HCW

Hot carcass weight

- IGF-I

insulin-like growth factor

- KPH

Kidney, pelvic, and heart fat

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acids

- NEG

Net energy for gain

- NEM

Net energy for maintenance

- SBW

shrunk body weight

- SUN

serum urea nitrogen

Contributor Information

Luke K Fuerniss, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

Kaitlyn R Wesley, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

Sydney M Bowman, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

Jerica R Hall, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

J Daniel Young, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

Jonathon L Beckett, Beckett Consulting Services, Fort Collins, CO 80524, USA.

Dale R Woerner, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

Ryan J Rathmann, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

Bradley J Johnson, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Literature Cited

- Abribat, T., Lapierre H., Dubreuil P., Pelletier G., Gaudreau P., Brazeau P., and Petitclerc D.. . 1990. Insulin-like growth factor-I concentration in Holstein female cattle: variations with age, stage of lactation and growth hormone-releasing factor administration. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 7:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0739-7240(90)90058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T., Shaver R., Bosma P., and De Boer V.. . 2007. CASE STUDY: performance of lactating Jersey and Jersey-Holstein crossbred versus Holstein cows in a Wisconsin confinement dairy herd. Prof. Anim. Sci. 23:541–545. doi: 10.1532/s1080-7446(15)31017-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D., Mächler M., Bolker B., and Walker S.. . 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beef Improvement Federation. 2021. BIF guidelines wiki: hip height/frame. http://guidelines.beefimprovement.org/index.php?title=Hip_Height/Frame&oldid=2361

- Berg, R. T., and Butterfield R. M.. . 1966. Muscle: bone ratio and fat percentage as measures of beef carcass composition. Anim. Prod. 8:1–11. doi: 10.1017/s000335610003765x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, R. T., and Butterfield R. M.. . 1968. Growth patterns of bovine muscle, fat and bone. J. Anim. Sci. 27:611–619. doi: 10.2527/jas1968.273611x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, R. T., and Butterfield R. M.. . 1976. New concepts of cattle growth. Sydney, Australia: Sydney University Press, University of Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard, B. C., Burdick N. C., Rathmann R. J., Carroll J. A., Finck D. N., Jennings M. A., Young T. R., and Johnson B. J.. . 2012. Chromium supplementation alters both glucose and lipid metabolism in feedlot cattle during the receiving period. J. Anim. Sci. 90:4857–4865. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bir, C., DeVuyst E. A., Rolf M., and Lalman D.. . 2018. Optimal beef cow weights in the U.S. southern plains. J. Agric. Resource Econ. 43:103–117. doi: 10.22004/AG.ECON.267612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland, D. W., Weigel K. A., Hoffman P. C., Esser N. M., Coblentz W. K., and Halbach T. J.. . 2011. Production, reproduction, health, and growth traits in backcross Holstein × Jersey cows and their Holstein contemporaries. J. Dairy Sci. 94:5194–5203. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykin, C. A., Eastwood L. C., Harris M. K., Hale D. S., Kerth C. R., Griffin D. B., Arnold A. N., Hasty J. D., Belk K. E., Woerner D. R., . et al. 2017. National Beef Quality Audit-2016: in-plant survey of carcass characteristics related to quality, quantity, and value of fed steers and heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 95:2993–3002. doi: 10.2527/jas.2017.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. R., and Lawrence T. E.. . 2010. Association of liver abnormalities with carcass grading performance and value. J. Anim. Sci. 88:4037–4043. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, T. C., Engle T. E., Galyean M. L., Wagner J. J., Tatum J. D., Anthony R. V., and Laudert S. B.. . 2010. Effects of ractopamine and trenbolone acetate implants with or without estradiol on growth performance, carcass characteristics, adipogenic enzyme activity, and blood metabolites in feedlot steers and heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 88:4102–4119. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, K. D., Bertrand J. K., and Benyshek L. L.. . 1993. Genetic and environmental parameters for mature weight and other growth measures in Polled Hereford cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 71:1737–1741. doi: 10.2527/1993.7171737x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, V. E. 2022. Economics of using beef semen on dairy herds. JDS Commun. 3:147–151. doi: 10.3168/jdsc.2021-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, H. G., Tatum J. D., and Williams F. L.. . 1993. Effects of feeder cattle frame size, muscle thickness, and age class on days fed, weight, and carcass composition. J. Anim. Sci. 71:2975–2985. doi: 10.2527/1993.71112975x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff, G. C., and McMurphy C. P.. . 2007. Feeding Holstein steers from start to finish. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 23:281–297, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S. R., Hobbs J. D., and Mulliniks J. T.. . 2017. High milk production decreases cow-calf productivity within a highly available feed resource environment. Transl. Anim. Sci. 1:54–59. doi: 10.2527/tas2016.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foraker, B. A., Ballou M. A., and Woerner D. R.. . 2022a. Crossbreeding beef sires to dairy cows: cow, feedlot, and carcass performance. Transl. Anim. Sci. 6:1–10. doi: 10.1093/TAS/TXAC059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foraker, B. A., Johnson B. J., Rathmann R. J., Legako J. F., Brooks J. C., Miller M. F., Woerner D. R., Foraker B. A., Johnson B. J., Rathmann R. J., . et al. 2022b. Expression of beef- versus dairy-type in crossbred beef × dairy cattle does not impact shape, eating quality, or color of strip loin steaks. Meat Muscle Biol. 6:139261–139219. doi: 10.22175/MMB.13926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerniss, L. K., Young J. D., Hall J. R., Wesley K. R., Benitez O. J., Corah L. R., Rathmann R. J., and Johnson B. J.. . 2023. Beef embryos in dairy cows: calfhood growth of Angus-sired calves from Holstein, Jersey, and crossbred beef dams. Transl. Anim. Sci Submitted May 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galyean, M. L., Nichols W. T., Streeter M. N., and Hutcheson J. P.. . 2023. Effects of extended days on feed on rate of change in performance and carcass characteristics of feedlot steers and heifers and Holstein steers. Appl. Anim. Sci. 39:69–78. doi: 10.15232/aas.2022-02366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, W. N. 1971. Energetic efficiency of beef and dairy steers. J. Anim. Sci. 32:451–456. doi: 10.2527/JAS1971.323451X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, W. N. 1980. Energy utilization by growing cattle as determined in 72 comparative slaughter experiments. In: Mount L. E., editor. Proceedings of the 8th symposium on energy metabolism of farm animals. Cambridge, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; p. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, W. N., Hinman N., Brokken R. F., and Delfino J. G.. . 1978. Body composition and the energy content of the gain of Charolais steers. J. Anim. Sci. 47:417. Supplement 1 [Google Scholar]

- Guiroy, P. J., Fox D. G., Tedeschi L. O., Baker M. J., and Cravey M. D.. . 2001. Predicting individual feed requirements of cattle fed in groups. J. Anim. Sci. 79:1983–1995. doi: 10.2527/2001.7981983x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzman, R. J., and Chan K. H.. . 1974. Alterations in weight gain and levels of plasma metabolites, proteins, insulin and free fatty acids following implantation of an anabolic steroid in Heifers. Br. Vet. J. 130:532–537. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(17)35739-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Smith, F. M., Picou D., and Golden M. H.. 1979. Muscle satellite cells in malnourished and nutritionally rehabilitated children. J Neurol Sci. 41(2):207–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(79)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy, O., Geyra A., M. Barak, Uni Z., and Sklan D.. 2000. Early Posthatch Starvation Decreases Satellite Cell Proliferation and Skeletal Muscle Growth in Chicks. J Nutr. 130(4):858–864. doi: 10.1093/JN/130.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, B. W. 1991. Compensatory growth in ruminants. In: Pearson, A. M. and Dutson T. R., editors. Growth regulation in farm animals. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, S. T., Woerner D. R., Vote D. J., Scanga J. A., Acheson R. J., Chapman P. L., Bryant T. C., Tatum J. D., and Belk K. E.. . 2014. Effects of ractopamine hydrochloride and zilpaterol hydrochloride supplementation on carcass cutability of calf-fed Holstein steers. J. Anim. Sci. 92:369–375. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaborek, J. R., Carvalho P. H. V., and Felix T. L.. . 2023. Post-weaning management of modern dairy cattle genetics for beef production: a review. J. Anim. Sci. 101:1–12. doi: 10.1093/JAS/SKAC345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B. J., Halstead N., White M. E., Hathaway M. R., DiCostanzo A., and Dayton W. R.. . 1998. Activation state of muscle satellite cells isolated from steers implanted with a combined trenbolone acetate and estradiol implant. J. Anim. Sci. 76:2779–2786. doi: 10.2527/1998.76112779x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E. R., Priyanto R., and Taylor D. G.. . 1997. Investigations into the accuracy of prediction of beef carcass composition using subcutaneous fat thickness and carcass weight II. Improving the accuracy of prediction. Meat Sci. 46:159–172. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(97)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. A., and Cohen P.. . 2007. Review: the Somatomedin hypothesis 2007: 50 years later. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92:4529–4535. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A. 2020. ggpubr: “ggplot2” based publication ready plots.https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggpubr/index.html

- Kassambara, A. 2021. rstatix: pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix

- Kauffman, R. G. 1978. Bovine compositional interrelationships. In: De Boer, H. and Martin J., editors. Patterns of growth and development in cattle. Dordrecht: Springer; p. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, R. G., Van Ess M. D., and Long R. A.. . 1976. Bovine compositional interrelationships. J. Anim. Sci. 43:102–107. doi: 10.2527/jas1976.431102x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, D. E., Manns J. G., Laarveld B., and Fehr M. I.. . 1991. Profiles of serum IGF-I concentrations in calves from birth to eighteen months of age and in cows throughout the lactation Cycle. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 71:695–705. doi: 10.4141/cjas91-085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, R. H., Terry C. A., Savell J. W., Cross H. R., Mies W. L., and Edwards J. W.. . 1989. Characterization of cattle types to meet specific beef targets. J. Anim. Sci. 67:2294–2308. doi: 10.2527/jas1989.6792294x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, R. M., Dikeman M. E., Allen D. M., May M., Crouse J. D., and Campion D. R.. . 1976. Characterization of biological types of cattle III. Carcass composition, quality and palatability. J. Anim. Sci. 43:48–62. doi: 10.2527/jas1976.43148x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, P. A. 2022. Assessment of equations to predict body weight and chemical composition in growing/finishing cattle and effects of publication year, sex, and breed type on the deviation from observed values. Animals. 12:3554–3523. doi: 10.3390/ani12243554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmkuhler, J. W., and Ramos M. H.. . 2008. Comparison of dairy beef genetics and dietary roughage levels. J. Dairy Sci. 91:2523–2531. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R. v. 2022. emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means.

- Lofgreen, G. P., and Garrett W. N.. . 1968. A system for expressing net energy requirements and feed values for growing and finishing beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 27:793–806. doi: 10.2527/jas1968.273793x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, E. D., King M. E., Fike K. E., and Odde K. G.. . 2022. Effects of Holstein and beef-dairy cross breed description on the sale price of feeder and weaned calf lots sold through video auctions. Appl. Anim. Sci. 38:70–78. doi: 10.15232/aas.2021-02215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, D. R., Roebert D. L., Bates P. K., Schmidt T. B., Hale D. S., Griffin D. B., Savell J. W., Brooks J. C., Morgan J. B., Montgomery T. H., . et al. 2002. National Beef Quality Audit-2000: survey of targeted cattle and carcass characteristics related to quality, quantity, and value of fed steers and heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 80:1212–1222. doi: 10.2527/2002.8051212x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWhorter, T. M., Hutchison J. L., Norman H. D., Cole J. B., Fok G. C., Lourenco D. A. L., and VanRaden P. M.. . 2020. Investigating conception rate for beef service sires bred to dairy cows and heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 103:10374–10382. doi: 10.3168/jds.2020-18399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriel, P., Cooke R. F., Bohnert D. W., Vendramini J. M. B., and Arthington J. D.. . 2012. Effects of energy supplementation frequency and forage quality on performance, reproductive, and physiological responses of replacement beef heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 90:2371–2380. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASEM. 2016. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle: eighth revised edition. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Animal Breeders. 2022. Annual reports of semen sales and custom freezing. https://www.naab-css.org/semen-sales

- National Research Council. 1996. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle: seventh revised edition. 7th ed.Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nour, A. Y. M., Thonney M. L., Stouffer J. R., and White W. R. C.. . 1983. Changes in carcass weight and characteristics with increasing weight of large and small cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 57:1154–1165. doi: 10.2527/jas1983.5751154x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, F. N., Gill D. R., Secrist D. S., and Coleman S. W.. . 1995. Review of some aspects of growth and development of feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 73:3152–3172. doi: 10.2527/1995.73103152x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr, S. L., Brown T. R., Ribeiro F. R. B., Chung K. Y., Hutcheson J. P., Blackwell B. R., Smith P. N., and Johnson B. J.. . 2014. Biological responses of beef steers to steroidal implants and zilpaterol hydrochloride. J. Anim. Sci. 92:3348–3363. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J. M. V., Bruno D., Marcondes M. I., and Ferreira F. C.. . 2022. Use of beef semen on dairy farms: a cross-sectional study on attitudes of farmer toward breeding strategies. Front. Anim. Sci. 2:90. doi: 10.3389/FANIM.2021.785253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, T. C., and Fox D. G.. . 1997. Predicting carcass composition and individual feed requirement in live cattle widely varying in body size. J. Anim. Sci. 75:300–307. doi: 10.2527/1997.752300x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, T. C., Fox D. G., and Beermann D. H.. . 1991. Effect of an implant of trenbolone acetate and estradiol on growth, feed efficiency, and carcass composition of Holstein and Beef Steers. J. Anim. Sci. 69:4696–4702. doi: 10.2527/1991.69124696x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyanto, R., Johnson E. R., and Taylor D. G.. . 1997. Investigations into the accuracy of prediction of beef carcass composition using subcutaneous fat thickness and carcass weight I. Identifying problems. Meat Sci. 46:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(97)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pophal, S., Mozdziak P., and Vieira S. L.. 2004. Satellite Cell Mitotic Activity of Broilers Fed Differing Levels of Lysine. Int J Poult Sci. 3(12):758–763. doi: 10.3923/ijps.2004.758.763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2022. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rastani, R. R., Andrew S. M., Zinn S. A., and Sniffen C. J.. . 2001. Body composition and estimated tissue energy balance in Jersey and Holstein cows during early lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 84:1201–1209. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74581-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann, R. J., Mehaffey J. M., Baxa T. J., Nichols W. T., Yates D. A., Hutcheson J. P., Brooks J. C., Johnson B. J., and Miller M. F.. . 2009. Effects of duration of zilpaterol hydrochloride and days on the finishing diet on carcass cutability, composition, tenderness, and skeletal muscle gene expression in feedlot steers. J. Anim. Sci. 87:3686–3701. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezagholivand, A., Nikkhah A., Khabbazan M. H., Mokhtarzadeh S., Dehghan M., Mokhtabad Y., Sadighi F., Safari F., and Rajaee A.. . 2021. Feedlot performance, carcass characteristics and economic profits in four Holstein-beef crosses compared with pure-bred Holstein cattle. Livest. Sci. 244:104358–104357. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2020.104358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]