Abstract

Clinical trials are considered the gold standard for establishing efficacy of health interventions, thus determining which interventions are brought to scale in health care and public health programs. Digital clinical trials, broadly defined as trials that have partial to full integration of technology across implementation, interventions, and/or data collection, are valued for increased efficiencies as well as testing of digitally delivered interventions. Although recent reviews have described the advantages and disadvantages of and provided recommendations for improving scientific rigor in the conduct of digital clinical trials, few to none have investigated how digital clinical trials address the digital divide, whether they are equitably accessible, and if trial outcomes are potentially beneficial only to those with optimal and consistent access to technology. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), among other health conditions, disproportionately affects socially and economically marginalized populations, raising questions of whether interventions found to be efficacious in digital clinical trials and subsequently brought to scale will sufficiently and consistently reach and provide benefit to these populations. We reviewed examples from HIV research from across geographic settings to describe how digital clinical trials can either reproduce or mitigate health inequities via the design and implementation of the digital clinical trials and, ultimately, the programs that result. We discuss how digital clinical trials can be intentionally designed to prevent inequities, monitor ongoing access and utilization, and assess for differential impacts among subgroups with diverse technology access and use. These findings can be generalized to many other health fields and are practical considerations for donors, investigators, reviewers, and ethics committees engaged in digital clinical trials.

Keywords: clinical trial, digital, digital intervention, HIV, technology

Abbreviations

- EHR

electronic health record

- GSN

geospatial networking

- PLHIV

people living with HIV

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

- SMS

short messaging system

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

INTRODUCTION

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are the principal design for establishing unbiased assessments of efficacy of health interventions and therapeutics. Although considered the gold standard, they are increasingly critiqued as expensive and logistically complicated, given the large sample sizes required for some trials, long periods of enrollment, and significant staffing and infrastructure for biologic and survey data collection (1–3). Barriers to participation in trials have historically been attributed to the time commitment, costs associated with lost productivity and transit for study participation, and competing priorities that hinder enrollment and participation (4, 5).

The rapidly growing integration of technology across all aspects of life and clinical care has provided opportunities for integration of digital methods in health research to address these issues (6, 7). Advances in digital health and digitally enhanced research methods have received widespread institutional and government support. The unanimous approval of the World Health Assembly Resolution on Digital Health signaled recognition of the value of digital technologies to contribute to attaining the Sustainable Development Goals, and the Assembly called for research in this field (8, 9). Similarly, research solicitations by the US National Institutes of Health and others have encouraged digital clinical trials, digitally enhanced observational research, and digitally delivered interventions on the basis of these advantages (3, 10). To this end, the US Food and Drug Administration has formed a public-private partnership with academic institutions, known as the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, to identify and advance digital methods for clinical trials (5). The recent acceleration of remote data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic has provided momentum to expand the use of digitally enhanced research methods—including digital clinical trials—beyond the pandemic.

DIGITAL CLINICAL TRIALS IN THE CONTEXT OF GLOBAL DIGITAL DIVIDES

The expression digital clinical trials is an umbrella term that largely captures clinical trials that range from partial to full integration of technology in trial implementation, interventions, and/or data collection (4). Prior reviews of digital clinical trials and digital interventions highlighted the advantages and disadvantages of digital clinical trials related to achievement of trial targets, quality of data, scientific rigor of the trial, and data security (4, 6, 11). Such reviews also provide guidance for improvements in these areas or recommendations for research and technologic advancement to address gaps (4, 6, 11). None of these reviews, however, systematically discussed equity in access to digital clinical trials nor to the resulting interventions or therapeutics that are ultimately deployed in clinical care and public health programs despite criticisms of under-representation of minoritized groups in RCTs across health disciplines as well as disparities in technology access (7, 12). One review did provide a recommendation to “bring broadband and Wi-Fi access to rural communities” (4, p. 5) to address such inequities. Although important, no guidance was provided as to how this would be accomplished nor to how to ensure equity in participation until such long-term goals were achieved (4).

Guidance has often been informed by pilot research conducted among nonrepresentative samples. A survey of web-recruited participants, led by the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, reported high participant preference for use of mobile technology instead of in-person data collection and provided recommendations to inform future digital clinical trials. However, the study sampled only via web-based methods and restricted eligibility to people who had access to a computer and a reliable internet connection and were able to read English. Ultimately, the sample lacked representation by race, ethnicity, and education (5). Although there have been substantial efforts to ensure and monitor equity in clinical research participation (13), there have been little to no evaluations of differential trial participation or trial outcomes as they relate to technology access nor whether these affect the participation of historically underserved or minoritized groups.

Widespread ownership of mobile phones is a frequently cited justification for the use of digital clinical trials, including digitally delivered interventions (4, 6, 14). In the United States, 97% and 85% of the population were estimated to own mobile phones and smartphones in 2021, respectively (6, 7). International estimates indicate that as of 2018, 5 billion persons have mobile technology, and half of these are smartphones (15). Across high-income countries, 76% of persons had smartphones, compared with 45% in emerging economies (15). There is heterogeneity across high-income countries, with approximately 90% smartphone ownership in South Korea, Israel, and the Netherlands, compared with 60% in Poland, Russia, and Greece (15). These regional differences are also evidenced in emerging economies, with higher smartphone ownership in South Africa and Brazil (approximately 60%), compared with 40% in Indonesia, Kenya, and Nigeria, and only 24% in India (15).

Within these estimates there are differences across race, ethnicity, sex, age, income, education, geographic residence, and urbanicity and rurality—all largely argued to reflect privilege that determines individual agency in access and use of digital technology (7, 16). Estimates of ownership and access also mask practices of sharing phones within households, a common practice among immigrant and displaced populations, as well as many others (17). Furthermore, literacy and language barriers also pose challenges to self-administration and/or access to online surveys that may be required for participation in digital clinical trials. Although literacy has increased greatly, there remains approximately 14% of the world’s population who are not literate (18, 19). Ultimately, differences in technology access across these demographic strata are often reflected by differences in response rates to digital clinical trials (20).

Estimates of ubiquitous phone ownership mask a critical appraisal of consistent mobile phone, smartphone, and internet connection over time that is often much lower than estimates of ownership or use for many populations and persist despite expansion of device ownership (21–23). Consistent mobile phone and internet access can be affected by individual inability to pay for service, theft or lending of devices, temporary use of unregistered SIM cards in countries that require registration to an identity document, and by other structural factors (24). Digital redlining, the “creation and maintenance of technological policies, practices, pedagogy, and investment decisions that enforce class boundaries and discriminate against specific groups,” (25) is central to many of ethno-racial inequities in technology in the United States. Friedline and Chen (26) quantified digital redlining, estimating that each percentage increase in the Black population in a given US zip code was associated with an 18% decrease in high-speed internet access and 1% decrease in smartphone ownership. In South Africa and in the Kashmir Region, the term digital apartheid has been applied to describe structural discrimination in access to internet or technology because of race and ethnicity (27, 28). These marked differences suggest that access to and participation in digital clinical trials may not be equitable and scale-up of those interventions may potentially aggravate inequities. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic quickly revealed the impact of racial, ethnic, age, and geographic inequities in access to telehealth, vaccine and testing registration, and virtual education programs (28–31).

DIGITAL CLINICAL TRIALS IN HIV RESEARCH

RCTs in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) research include pharmaceutical trials, such as those evaluating efficacy and safety trials of new pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) formulations and antiretroviral therapy medications, while other behavioral intervention trials test methods to increase individual HIV education and awareness, reduce HIV acquisition or transmission risk behaviors, or improve engagement across aspects of the pre-exposure prophylaxis and HIV care continua (32, 33). Digital clinical trials can increase efficiencies of these studies through digital recruitment, digital data collection, remote biospecimen collection and electronic transmission of results to participants, technology-enhanced adherence monitoring and sensing, and triangulation with electronic health records (4, 34). These digital methods can aid in reducing study cost and enrollment time, while improving reach to geographically dispersed populations and facilitating achievement of the target sample size (35).

The target populations in RCTs and digital clinical trials in HIV research are often those who experience the highest burdens of infection. The HIV epidemic, much like digital access, is marked by significant disparities among marginalized populations globally (36). HIV prevalence remains highest in countries with lower- and middle-income economies, and within-country variation in HIV prevalence exists along the lines of gender and race, and disproportionately affects populations facing historical discrimination, stigma, and criminalization (37). Social determinants of health that enable the HIV epidemic to persist, such as economic instability, disparities in health care access, built environments, discrimination, and stigma, also facilitate disparities in reliable technology access and use.

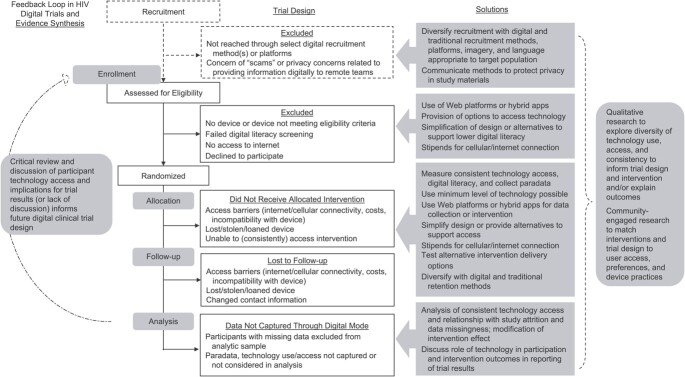

In light of these potential benefits and considerations, we reviewed the use and methodologies of such trials in global HIV research to date. The findings presented here were produced from our review of published scientific articles available in the peer-reviewed literature. Using the broad definition of digital clinical trials as clinical trials that range from partial to full integration of technology in trial implementation, interventions, and/or data collection, we reviewed the methods and strategies that have been used to date. We consider whether digital clinical trials in HIV research risk repeatedly excluding populations with lower, even in smaller proportions, consistent access to technology. Importantly, could these trials be excluding subpopulations who are navigating environments and contexts that increase their risk for HIV? In this narrative review, we consider how aspects of trial design may risk potentiating or may protect against health inequities (Figure 1). Where less information is available for digital clinical trials, we draw on findings from digital observational research.

Figure 1.

Design considerations to address and prevent inequities in digital clinical trials.

DIGITAL RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

Recruitment from social media platforms, geosocial networking (GSN) dating apps (e.g., Grindr), and other online venues are common in HIV research. Digital methods have been incorporated into other sampling methods, such as electronic, respondent-driven sampling (38). Development of closed social media groups and automated notifications are common strategies for engaging and retaining participants. Use of these methods is particularly enticing for reaching candidates in virtual spaces they frequent and/or that may be associated with relevant health behaviors, engaging participants in times and spaces convenient to the individual, and reducing staffing and travel costs for traditional outreach, in-person sampling methods, and retention activities (39).

With a few exceptions, online recruitment methods are convenience samples and may risk noncoverage and selection bias in a digital trial, given diversity in ownership and consistent access to technology, as well as preferences for devices and social media that are often differential by age, race, ethnicity, geographic setting, and gender (35). Many observational studies describe sexual risk practices among users of online platforms as a justification for recruitment into HIV research from these platforms, but findings have been mixed as to whether sexual-risk practices are increased relative to nonusers, and nonusers are often not a comparison group (40–43). A few studies have shown increased sexual HIV acquisition- and transmission-risk behaviors among GSN app users relative to nonusers, but they also have shown increased awareness and use of HIV prevention methods (41–43). Research in the United States and Europe has shown that GSN dating apps facilitate sexual partnerships as well as drug-use partnerships among gay and bisexual men who have sex with men, increasing risk for both HIV and STI acquisition and highlighting a critical area for GSN-based interventions (44–47). Although use of dating apps for recruiting candidate participants to trials targeting such behaviors is justified (48), the exclusive use of web-recruited samples to reach wider groups who can benefit from the HIV prevention or care intervention is not yet justified. The few studies comparing digital to other recruitment sources have not suggested an enhanced ability to reach people at greater risk for HIV acquisition or worse treatment outcomes who could benefit from trials focusing on HIV prevention or care (41).

Clinical trial participants should be representative of the populations who can benefit from the interventions. Digital clinical trial samples can be diversified through use of hybrid recruitment approaches that combine online and offline methods, which have shown increased ability to engage more diverse samples as well as to engage understudied populations or those with small population size (44, 49–52). Likewise, using diverse images and expanding language availability, both in web-based materials and other study materials, are techniques often used to maximize diversity, and targeted advertisements across a range of social media and GSN dating apps facilitate diversity in web-recruited samples. Offering options for study incentives, rather than 1 form of electronic incentive (e.g., Amazon gift cards), may support accrual of populations who prefer cash, do not shop online, or who are less likely to access or use services from the specified vendor or retailer (53). Finally, collection of multiple sources of contact, allowing participants to update contact information, and combining traditional retention methods (e.g., staff calls) with automated messaging are simple methods to foster retention when technology access may be inconsistent (54, 55).

ELIGIBILITY CRITERION ON THE BASIS OF TECHNOLOGY OWNERSHIP AND ACCESS

Clinical trials can covertly or overtly exclude participants on the basis of technology access by limiting participation or access to interventions through only 1 technology platform or by explicit exclusion of participants on the basis of home internet connection, smartphone ownership, or personal device operating system (23, 56, 57). Restriction of eligibility on the basis of technology access is typically used to ensure that study participants can access the data collection platform and/or digital intervention, but it raises questions of the real-world effectiveness, sustainability, and ethical considerations (58).

To evaluate the extent to which this occurs in trials of digital interventions, we examined 46 studies included in a prior review of publications that reported the use of digital interventions as standalone interventions or as a component of combination strategies to support HIV prevention and/or care (59). Studies were reviewed to identify the setting of the digital intervention and the population, and to explore how inclusion and exclusion from the trials were discussed in relationship to technology access. Table 1 describes the published studies. Of these 46 articles, almost half (n = 22; 48%) overtly restricted eligibility on the basis of technology access (e.g., smartphone use, Android/iOS systems, home internet). In studies that described excluding candidates from participation because they did not have a mobile phone, authors did not discuss the sociodemographic characteristics of those who were excluded and whether they were similar or different from included participants (14, 21, 22, 60–64). For a US-based study, researchers conducted an RCT to evaluate the use of text-messaging reminders to support care for people living with HIV (PLHIV). Technology access was not an eligibility criterion but of 94 individuals who were offered enrollment, 45% declined to participate. Half of those declining cited lack of ownership of a mobile phone or the inability to text as their primary reason for not participating (21). The authors further commented on low technology access among those enrolled, wherein a quarter of the 25 who were randomly assigned had their phones disconnected during the intervention. Furthermore, half of persons who were screened received government assistance and lived below the poverty line (21), which reflects larger contexts of poverty among PLHIV in high-income countries (65).

Table 1.

Review of Digital Interventions to Support HIV Prevention and Carea

| First Author, Year (Reference No.) | Location | Target Population | Gender Breakdown of Study Sample, No. | Type of Digital Intervention | Author Discussion of Internet Access in Trial | Author Discussion of Other Technology Access in Trial | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | Transgender and Gender-Diverse People | ||||||

| da Costa, 2012 (61) | Brazil | PLHIV women | 21 | 21 | SMS intervention | N/A | Mobile phone required for eligibility. Of 59 people screened, 21 were not eligible because they did not possess a mobile phone. | ||

| Sabin, 2010 (78) | China | PLHIV on ART and aged ≥18 years | 68 | 50 | 18 | Electronic drug monitors | N/A | Provided to those in the intervention arm | |

| Huang, 2013 (123) | China | Adult PLHIV | 196 | 94 | 102 | Mobile phone call | N/A | Mobile phone required for eligibility | |

| Fan, 2020 (124) | China | MSM | 600 | 600 | App-based, which provided those in intervention group with 1-to-1 communication with experts, hospital-visit reminders, and educational content | Internet access on smartphone required for eligibility. | Smartphone required as well as a WeChat account | ||

| Yan, 2017 (125) | China | MSM aged ≥16 years with negative HIV test | 800 | 800 | App-based prevention and treatment of HIV and STIs | Justified by internet and phone use throughout daily life | Mobile phone that was compatible with app required for eligibility. Authors monitored the cost of cellular data, internet usage in the study. | ||

| Shet, 2014 (68) | India | Adult PLHIV | 631 | 358 | 273 | Mobile phone intervention | N/A | Mobile phone network in area of residence required for eligibility. All participants were provided a mobile phone by the study program so the not possessing phone would not affect adherence. A total of 495 participants of 631 owned or shared phone. | |

| Patel, 2020 (126) | India | HIV negative or HIV status unknown MSM | 244 | 244 | Internet-based intervention: peer-delivered messaging on intervention for HIV testing and consistent condom use | Participants were recruited online through popular dating websites. | Variety of media through which messages could be received (e.g., smartphone, work or home computer, internet café) | ||

| Winskell, 2019 (127) | Kenya | Male and female youth (aged 11–14 years) in urban Kisumu | 60 | 30 | 30 | Tumaini game: narrative-based app game developed with HIV-prevention messaging in mind | Internet access required to download the game but not required to play the game | ||

| Drake, 2017 (128) | Kenya | Pregnant women living with HIV who were >14 years old | 852 | 852 | One-way and 2-way SMS groups, received messages on, for example, ART adherence, pregnancy support and education, infant health | N/A | Mobile phone required for eligibility; the SMS software the project used was compatible with only 1 of the major service providers. Women with other carriers were excluded. Authors noted that many women share their phone with family and may have not been comfortable reading their messages. | ||

| van der Kop, 2018 (22) | Kenya | PLHIV aged ≥18 years | 700 | 281 | 419 | Weekly automated text messages that required participant response | N/A | Mobile phone required for eligibility. Some participants did not have enough credit on their phones to receive texts and therefore did not have access. | |

| Haberer, 2021 (129) | Kenya | Women aged 18–24 years | 348 | 348 | SMS reminders for PrEP adherence | N/A | Mobile phone required for eligibility. All but 1 woman approached had their own mobile phone. | ||

| Mwapasa, 2017 (73) | Malawi | Pregnant women LHIV | 1,350 | 1,350 | SMS messages with appointment reminders | N/A | Participants did not have access to phones; therefore, they did not always receive the messages. Health care workers did not always get messages out in a timely manner. | ||

| Elul, 2017 (92) | Mozambique | PLHIV aged ≥18 years | 2,004 | 712 | 1,292 | SMS intervention (e.g., health appointment reminders, messages to address behavioral barriers associated with not accessing care) | N/A | Had the option to send messages to their phone or, if the participant did not have a phone, to a friend or family members’ device | |

| Perera, 2014 (130) | New Zealand | Adults who were PLHIV taking ART | 28 | 26 | 2 | Smartphone application | Discussed as a new form of health-related intervention | Use of an Android smartphone was required for eligibility. | |

| Bayona, 2017 (131) | Peru | MSM with a recent HIV diagnosis | 40 | 40 | Short messages over WhatsApp or Facebook from their counselor | N/A | Ownership of mobile phone required for eligibility. | ||

| Robbins, 2015 (132) | South Africa | PLHIV adults taking ART | 65 | 22 | 43 | Computer-based intervention | Internet connection was not required to administer the intervention. | Laptop computer provided by intervention team for study. Some computer literacy required. | |

| Venter, 2019 (66) | South Africa | Adult PLHIV | 345 | 121 | 224 | App-based: Smart Link app, engaged participants with their own care by directly providing them laboratory test results, appointment reminders, medication adherence, and HIV in general. | Wi-Fi was provided to download the app so that there was no data cost to participants. | Android smartphone and access to data on the phone required for eligibility | |

| Leu, 2019 (72) | South Africa, US, Peru, Thailand | MSM and transgender women aged >18 years who were not PLHIV | 186 | 163 | 23 | Participants were sent text messages reminding them to adhere to their daily regimens of their intervention group. | Participants recruited via social media, online advertising, as well as other nondigital methods | Participants required to pass a SMS readiness assessment. Participants who did not own a mobile phone were provided one through the study. | |

| Kerrigan, 2019 (133) | Tanzania | Female sex workers | 387 | 387 | After initial intervention at drop-in center or clinic, follow-up text messages were sent promoting solidarity and engagement with the intervention for women LHIV. | N/A | Access to mobile phone was associated with loss to follow-up. Team was also willing to make personal contact for retention if individual did not have a phone. | ||

| Chang, 2011 (134) | Uganda | Adult PLHIV taking ART | 970 | 320 | 650 | mHealth intervention | N/A | Participants were provided with mobile phones and training. Key challenges identified included variable patient phone access, privacy concerns, and phone maintenance. | |

| Sabin, 2020 (135) | Uganda | Adult, pregnant women (12–26 weeks’ gestation) | 165 | 165 | Wireless pill monitors, detected late-dose taking and sent text-message reminders | N/A | Mobile phone that could receive text messages and phone calls was required for eligibility. Authors noted that there is no cost to receive texts in Uganda. | ||

| Getty, 2018 (136) | UK | HIV-negative adults who use drugs and are enrolled in methadone treatment | 11 | 7 | 4 | Computer-based self-paced training program to teach adults at risk for HIV about PrEP | Conducted at the facility with computer and internet provided to participants by study facilitators | N/A | |

| Norton, 2014 (21) | USA | PLHIV aged ≥18 years | 52 | 39 | 13 | Text-message reminders | N/A | Mobile phone required for eligibility. Of those screened for enrollment, half did not have the necessary technology. Some who were screened for enrollment noted that texting cost too much to participate. Several participants had their phones disconnected during the study. | |

| Konkle-Parker, 2012 (137) | USA | PLHIV adults about to start ART for the first time or after a gap in treatment | 56 | 35 | 21 | Peer video viewing, telephone calls | N/A | Mobile phone required for eligibility | |

| Roth, 2012 (60) | USA | PLHIV adults | 476 | 405 | 71 | Telephone call | N/A | Not explicit in eligibility criteria, though some were excluded for having no phone or phone number. | |

| Chander, 2015 (138) | USA | Adult women who consumed alcohol at hazardous levels, PLHIV | 148 | 148 | Telephone call | N/A | Not explicit in eligibility criterion | ||

| Johnson, 2007 (139) | USA | Adult PLHIV | 204 | 159 | 45 | Module intervention, individual counseling sessions | N/A | Provided at facility upon intervention delivery | |

| Robbins, 2013 (140) | USA | Adult PLHIV starting ART | 333 | 264 | 69 | Telephone intervention | N/A | Participant ability to receive a phone call on a mobile phone or a landline required for eligibility | |

| Collier, 2005 (141) | USA | Adult PLHIV | 517 | 419 | 98 | Telephone intervention | N/A | No discussion of phone ownership | |

| Hardy, 2011 (69) | USA | Adult PLHIV taking ART | 19 | 10 | 9 | Telephone intervention using mobile phone and pager | N/A | Participants received phones with unlimited calling and texting plans. Authors reported increased adherence and ability to maintain privacy. | |

| Shuter, 2020 (64) | USA | Adult PLHIV interested in quitting smoking | 80 | 53 | 24 | 3 | App-based intervention | Internet access required for intervention. | Score of score of at least 4 on the REALM-SF literacy scale (7th- to 8th-grade reading level) and smartphone ownership compatible with the Positively Smoke Free-Mobile (all iPhones and most Androids) required for eligibility. Access measured via a smartphone usage index. |

| Mustanski, 2018 (142) | USA | HIV-negative MSM | 445 | 445 | Initial intervention was 7 online modules completed in 3 sessions ≥24 hours apart | E-mail address requirement indicates some level of internet access, though it was not explicitly discussed in the intervention. | E-mail address required | ||

| Christopoulos, 2018 (143) | USA | Adult men and women from Ward 86 of San Francisco General Hospital | 230 | 193 | 25 | 12 | Text-message based intervention with intervention messages, primary-care appointment reminders | N/A | Low-income patients who expressed interest but did not own a cell phone were referred to Lifeline Assistance program, which supports low-income individuals in obtaining a phone. |

| Castonguay, 2020 (70) | USA | PLHIV with a history of incarceration | 57 | 33 | 14 | 10 | Text-message based with HIV appointment reminders, medication adherence, HIV-prevention reminders, and messages about navigating barriers to care; participants able to adapt frequency of messages, timing | N/A | Reimbursed a monthly phone plan for texting capability (up to $25). Participants were provided a smartphone by the study program at no cost, up to 1 replacement. |

| Mayo-Wilson, 2019 (144) | USA | African Americans (aged 18–24 years) homeless, unemployed in the last month | 43 | 15 | 28 | Text-message based on HIV prevention coupled with a grant for starting a small business and mentorship | N/A | Mobile phone with texting capabilities and data was required for eligibility. Most participants (84%) owned a password-enabled phone mobile phone; 40% reported that others could access the participant's mobile phone. | |

| Kalichman, 2018 (145) | USA | PLHIV in Atlanta, Georgia | 500 | 383 | 117 | The Mix intervention was adapted for mHealth delivery; most intervention components were individualized and delivered by mobile phone with 1 delivered at the facility. | N/A | N/A | |

| Stephenson, 2020 (63) | USA | Binary and nonbinary transgender youth | 202 | 202 | Video-based counseling when receiving HIV self-testing kit results | Recruitment occurred online over social media. | Access to computer, smartphone or tablet required for eligibility. Discussed that sample likely underrepresented trans youth who did not have access to the internet. | ||

| Basaran, 2019 (146) | USA | Latino, Black, or White men aged 18–30 years | 540 | 540 | SOLVE intervention: interactive video 20–30 minutes long | N/A | Intervention (watching and interacting with video) was conducted at the facility. Detailed instructions provided on how to use the technology. | ||

| Ybarra, 2018 (147) | USA | Gay, bisexual, queer cisgender men aged 14–18 years | 302 | 302 | Text message–based HIV prevention program Guy2Guy. Daily messages over 5 weeks with 1 week booster delivered 6 weeks after the 5 weeks ended. Talked about HIV testing, healthy relationships, condom use | Recruited over Facebook. Authors noted that the sample would not be representative of those who were not on social media or who had little to no access to the internet. | Not explicit in eligibility criterion. Discussion of high rates of mobile phone ownership across ethnic groups, income levels | ||

| Cho, 2019 (148) | USA | Aged ≥18 years with a detectable viral load | 38; | 15 | 23 | Medication-monitoring pill bottle linked to an HIV self-management Wise App with testimonial videos of PLWH and notifications for medication adherence and general wellness | Some participants were recruited over social media. No discussion regarding app requirements for internet access | Smartphone ownership required for eligibility | |

| Colson, 2020 (149) | USA | Black MSM and transgender women (aged ≥18 years) who had any STI in the last 6 months or who had an HIV-positive partner | 204 | 194 | 10 | Access to online support group through social media and automated text-message medication reminders | Some participants were recruited online through Facebook, dating apps, and Craigslist. No discussion of internet access | N/A | |

| Browne, 2018 (111) | USA | African American women (aged 18–25 years) | 600–700 | 600–700 | App-based intervention | Wi-Fi was not required to use the app; the app was provided to participants at the facility where they were able to connect to Wi-Fi to download the app. | Mobile phone required for eligibility | ||

| Westergaard, 2017 (71) | USA | PLHIV aged ≥18 years with viral load >1,000/mL | 19 | 12 | 7 | Both face to face and digital interactions with peer navigators. mHealth application provided to participants through which they completed surveys | N/A | Smartphone was loaned to participant if they were in intervention group with training on how to use the mHealth application. | |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LHIV, living with HIV; mHealth, mobile health; MSM, men who have sex with men; N/A, not applicable; PLHIV, people living with HIV; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SMS, short messaging system; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

a Sources drawn from a review by Mbuagbaw et al (59).

Exclusion due to lack of mobile phone access was also seen in low- and middle-income contexts. A study in Brazil reported that 21 of 59 persons (36%) screened were ineligible to participate because they did not have a mobile phone (61). A randomized trial in South Africa screened 4,500 participants for a short messaging system (SMS)–based intervention to link newly diagnosed patients to care using an Android-based app. Of 3,540 who passed prescreening, only 350 (10%) remained eligible after screening for related smartphone criteria. Lack of an Android phone was the most frequent exclusion criteria (59%), but lack of a mobile phone or an active SIM card (14%), and related factors such as not having the correct Android version, adequate RAM or mobile data, were also reasons for exclusion from the trial (14, 66). In Kenya, 14% of persons screened for an SMS-based intervention to support retention in care were excluded because of lack of mobile phone ownership or inability to receive text messages (22). Furthermore, 25% of intervention participants who did not respond to intervention text messages indicated nonresponse was due to insufficient credit or that their mobile phone was not working (22).

The lack of data on persons who were excluded because of low rates of mobile-phone ownership precludes understanding if this group of persons may have poorer HIV and other social and health outcomes. For instance, a recent South African study reported that persons who owned smartphones were more likely to be young, women, and employed, and were less likely to report practices that may elevate HIV acquisition risks (e.g., condomless sex, lack of male circumcision) (67). Thus, digital clinical trials that require technology access for participation may inadvertently exclude persons who do not own phones (in that example, unemployed persons, men) who, in fact, may be in greater need of HIV prevention or care strategies (67). Yet the lack of sociodemographic and health outcome data of excluded participants is a barrier to understanding how to tailor digital clinical trials to ensure no one is left behind.

To avoid excluding candidate participants, 9 of the 46 studies (20%) provided an alternative access route to technology, such as providing mobile phones, computers, and data plans. What this access looked like varied greatly. For instance, in 3 studies in the United States and India, a mobile phone was provided to participants, regardless of being in the intervention or control arm, and the phone was given and not loaned (68–70). The CARE+ Corrections pilot, an SMS-based intervention for PLHIV and involved in the criminal justice system, provided mobile phone plans with monthly pooled-minutes to cover the cost of text messages for all participants and replaced lost or broken phones, which was requested by almost two-thirds of participants (70). In other research spanning contexts such as the United States, South Africa, Peru, and Thailand, phones were loaned for the duration of the study and expected to be returned at study completion (71, 72). In a 3-arm trial of mother–infant pair clinics and SMS reminders on retention of HIV-infected women and HIV-exposed infants in care in Malawi, investigators provided mobile phones to participants, noting that the prevalence of mobile phone ownership was 36% at the time of the study and the majority of eligible mothers lacked mobile phones (73).

Although study-provided access to technology ensures inclusion across subgroups in the trial itself, it raises ethical questions about providing technology during a study and then removing it after the trial has ended. Furthermore, the various ways that studies address technology access (giving vs. loaning a phone) signals the potential for researchers to further explore the long-term social and health implications when making these study design decisions. Much like commitments are made in pharmaceutical trials to provide the study drug to participants after the trial, if it is found to be effective, this option should be considered at the design stage for digital clinical trials (74, 75). Less common, but critical, have been reports of exacerbated gender inequities and partner conflicts associated with the distribution of mobile phones, as well as frequent texting, for women’s HIV prevention interventions (22, 76). Finally, exclusion on the basis of technology ownership or access and the need to provide these technologies for trial participation raises questions of sustainability and whether potentially efficacious interventions will be accessible to those who could benefit once brought to scale.

DIGITAL HEALTH DATA COLLECTION

Digital health data collection can include digital collection of participant-reported data via apps, SMS, and web portals but can also include remote biospecimen collection, adherence monitoring, and wearable devices (77–81). The vast majority of these methods have been used in response to participant barriers related to time and travel spent accessing study facilities, to collect data outside of clinical settings, and to engage participants in more dispersed geographic locations (82). A number of platforms are commercially available to provide functionality for SMS-based data collection and interventions, though little has been reported on the quality and feasibility of these systems (79). Related to convenience and time efficiency, apps and web portals have become common methods for participants to complete remote, computer-assisted self-interviews. The use of smartphone and tablet apps for data collection may restrict access to participants who consistently possess those devices. There are also logistical challenges related to creating apps that are functional across Android and iOS systems, resulting in several pilots and trials that have developed apps that previously were only available on 1 operating system (14, 70, 71). Hybrid apps, which provide access through downloadable apps or via web portal, and use of web portals for data collection provide more comprehensive access across mobile phone, tablet, and/or computer ownership or access (55).

The many benefits of digital data collection methods are balanced against challenges associated with participant literacy and digital literacy in responding to surveys and completing other digital procedures. Despite heavy use of digital methods in HIV trials, whether for data collection, interventions, or both, few studies assess participant health literacy, digital literacy, and technology use. Brief tools, such as the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short Form (REALM-SF) and the Short Assessment of Health Literacy–Spanish and English (SAHL-S&E) are available to evaluate participants’ literacy and determine optimal mode of administration for successful participation in research (64, 83, 84). These tools have been used in HIV clinical trials, adapted for relevance to populations heavily affected by HIV, and made available in a number of languages (55, 64, 85). Measures of combined health technology and digital health literacy can also be integrated into trial assessments (86, 87). Fewer validated measures of technology use and access are available. The SMS Readiness Assessment offers 4 brief items to assess mobile phone ownership, phone sharing, and frequency of and familiarity with text messaging (88).

Simple questions can be embedded within baseline and other study assessments to measure access and consistency of access and whether these predict attrition or modify study outcomes. Such measures include mobile phone ownership and type, home internet connection or settings where participants primarily access the internet, privacy of data on devices, recent (past 6 or 12 months) loss of mobile phone due to theft or lending, and recent experiences of having one’s phone plan or service suspended. Measures that assess whether participants access HIV prevention and care information through online methods serve to identify who has access to digital health information. Indeed, 1 observational study among transgender women in Cambodia demonstrated higher HIV prevalence among participants who had never accessed online HIV services and information compared with those who had not accessed such online services (89). Use of digital health literacy measures to assess HIV-testing trial outcomes among young gay and bisexual men demonstrated that participants with lower digital health literacy reported lower intervention-information quality scores and systems quality scores relative to participants with higher digital literacy. This led authors to conclude that assessments of digital health literacy are critical to understanding how participants may navigate and use intervention content (90). Finally, video instructions with subtitles, remote interviewer-assisted interviews for participants who need support, and enhanced language accessibility provide additional options for ensuring accessibility to digital clinical trial participation.

Several other tools provide opportunities to collect data that are not reliant on participant self-report or recall. Use of electronic health records (EHRs) provides an optimal way to obtain laboratory-based measures and clinical diagnoses. Furthermore, machine learning has been integrated within EHRs in the United States and Eastern African settings to predict which patients may benefit from pre-exposure prophylaxis (91). Use of EHRs in digital trials become more logistically complicated in settings where participants access different services in multiple facilities that do not have linked EHRs, seek care outside of their local health catchment area to maximize privacy, or where EHRs are of low quality or incomplete (92).

There have also been concerns and distrust among participants in terms of the security of data, which varies across settings and level of experience with technology (39, 93–95). Privacy and confidentiality are typically protected in health care through legislation, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in the United States. Such regulations and protections do not apply to commercial entities in most countries, which is an important consideration if considering use of social-media messaging systems for recruitment, interventions, study communication, and data collection (96). Data breaches and marketing of user data by social media firms and commercially available apps without user knowledge or consent, including a notable exchange of data on dating app users’ HIV status, underscore challenges in how to reach and engage participants in convenient ways that map to participants’ daily life while maintaining appropriate protection of participant privacy (97, 98).

Participant concerns and distrust can be addressed up front through implementation of stringent security protections. Certificates of confidentiality are available in the United States to protect participant data against criminal, administrative, and legislative requests; these are automatically provided to federally funded grants but can also be requested for US-based trials receiving funding support through other mechanisms (99). Enhanced security features used in digital interventions for violence research can be applied to HIV research for populations who may be particularly vulnerable to social impacts associated with participation in research (100, 101). Communication that recognizes participant concerns and describes risk mitigation efforts should be provided in advance of and in addition to consent processes.

DIGITAL INTERVENTIONS

Digital interventions in HIV research are wide ranging and have been developed and trialed for improving outcomes across the HIV prevention and care continua, as well as to address other outcomes related to mental health, substance use, and health concerns. These have included, but are not limited to, demand generation, education, adherence support and other behavioral interventions, partner interventions, peer support groups and peer navigation, access to HIV and STI self-collection or self-test kits, use of the EHR for STI testing, and partner notification (79, 91, 102–104).

Digital interventions may vary in complexity based on the device, level of technology, and the amount of user engagement. For example, simple 1-way reminder text messages have been tested to support adherence to HIV medication (102). Device complexity may be escalated with applications that require smartphones, tablets, computers, or wearable devices. The level of technology may range from a simple text message via cellular data to the need for Wi-Fi or Bluetooth to fully engage with the intervention. User engagement ranges from simply receiving messages, bidirectional messaging, active text-message chats, and engaging with social media groups to interactions with apps or artificial intelligence software (91). Most recently, machine learning has been used to support “just-in-time” interventions through smartphones to identify and respond to momentary HIV risk behaviors, and artificial intelligence has been applied to virtual reality and chatbot interventions supporting HIV serodisclosure and HIV prevention, respectively (91, 105–109). Effectiveness of these interventions in study outcomes or in terms of larger impacts on the HIV epidemic have been evaluated and little data are yet available on participant acceptability and uptake. Marcus et al. (91) highlighted in their review the potential for artificial intelligence to be inadvertently developed with algorithms that incorporate ethno-racial biases, and the authors warned of the risk of perpetuating health disparities. The few pilot and formative studies that have tested these approaches have been mixed in efforts to address this risk (105, 107).

Digital interventions, particularly app-based interventions, take on logistical complexity with frequent need to update the software for compatibility to the newest devices and operating systems to be responsive to trends in HIV interventions, and to match technology preferences by the target population (110). The cost of app development often leads to apps that are developed and trialed in only 1 operating system and result in overt or covert exclusion of groups without compatible devices, as we discussed earlier (14, 66). Furthermore, updating apps to maintain software compatibility with operating systems can have adverse effects by rendering the app incompatible for participants with older device models and operating systems. Finally, regular engagement via cellular or Wi-Fi may come at a cost to participants for each message sent, particularly if relying on cellular data.

Parallel to this, digital interventions may make use of social media platforms to enhance information, education, communication, and peer interaction. However, social media platforms are associated with specific levels of technology and, at the very least, require access to cellular data. Irrespective of how the digital intervention is developed, the more complex interventions are less likely to reach and work with the more disenfranchised people who have limited access to sophisticated devices and Wi-Fi, and who share devices. Ethical concerns have also been raised about the trail of data, including digital transcripts, available to social networking sites and third parties when social media platforms are used for interventions (96).

The way forward is to ensure that digital applications are delivered via the level of technology accessible to the largest and most diverse proportion of the target population. Although mobile devices have advanced in terms of their technological capacity, they still maintain the basic mobile phone functionalities that can be used to interact with participants, without the need for advanced data and software. Interventions can be designed to cater to different levels of technological access. Finally, alternative delivery of interventions can be tested, for example, comparing facility-based versus online delivery or other alternative approaches (107, 111).

ANALYSES AND REPORTING OF TECHNOLOGY USE WITH TRIAL OUTCOMES

Analysis and reporting of digital trial results require careful consideration regarding concerns of transparency and risk of bias. To fully capture the impact of digital media for trial implementation, researchers should report the number and characteristics of participants who were excluded because they did not meet the digital criteria (i.e., no device, residing in an area with no signal) and those who were lost to follow-up for digital reasons (e.g., lost phone, changed phone number, suspended plans).

There are existing tools that facilitate such reporting. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)–Equity extension is applicable in situations in which investigators acknowledge that access to digital tools is a source of health disparity. Following this framework, they would be expected to record and report eligibility, recruitment, allocation, and follow-up according to digital access (112). Likewise, the CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic interventions specifies key issues related to the intervention, such as whether adherence to the intervention was measured or enhanced (113).

Within the context of digital interventions, investigators may use paradata to assess engagement with digital behavioral interventions (114). Paradata, the process data documenting users’ access, participation, and navigation through a digital intervention, can be used to examine engagement with the digital interventions to evaluate dose response of the intervention. However, it can also serve as an important metric to assess for attrition by technology use or to assess for differential engagement with digital interventions by technology access and digital literacy.

Analytic plans can be designed in advance to accommodate subgroup analysis to explore trial outcomes by technology access, consistent access, digital literacy, and/or types of technology ownership. Petticrew et al. (115) acknowledged in their review that subgroup analysis can be “tantamount to statistical malpractice” but highlights the utility of these analyses for assessing equity in clinical trials. These analyses can include relative effectiveness analyses, identification of harms associated with the intervention, and other analyses with hypothesized subgroup effects (115). Analyses should be considered at the design stage and articulated in proposals of digital clinical trials, where sample-size calculations should be powered with consideration to these secondary analyses and randomization methods may be stratified by technology metrics. Finally, in-depth exploration and transparent reporting of challenges associated with technology in digital clinical trials are critical to advancing equity in future HIV trials and programs (14, 66).

MAXIMIZING DIGITAL CLINICAL TRIALS THROUGH QUALITATIVE AND COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH

Formative research to assess barriers, acceptability, and inform user-centered design of digital interventions and other technology is important to ensuring the success of the digital trial and intervention. Formative research in trials frequently focuses on problem definition and elicitation of feedback on digital interventions in terms of structure, content, and delivery of digital interventions (116, 117). Qualitative studies have also uncovered concerns related to costs, literacy, device use, cost of data, and lost or damaged devices (118). Formative research related to machine learning for risk prediction and use of artificial intelligence for chatbots have highlighted concerns associated with incorrect machine or self-diagnosis, cybersecurity, and ability to build rapport and empathize with users (91). Less frequently implemented or reported are formative explorations of how the target population and subgroups use and access technology, including in health-seeking behaviors, as well as ways in which HIV interventions can explicitly be integrated within their daily practices. Such information would be informative for the selection of the digital tools, thereby reducing waste in trials associated with screening large numbers of candidates for compatible devices, replacing lost devices, or attrition associated with consistent access. To avoid bias in the selection of a digital platform, participants of such formative work should not be sampled through a single digital source, but rather through a range of digital and nondigital sources.

Post hoc participant feedback and community interpretation of results are valuable approaches in understanding the reach, values, and impact of digital interventions. An analysis of data from the Cameroon Mobile Phone SMS (CAMPS) trial, a randomized trial of text messaging versus usual care to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy, revealed that participants had other needs beyond the purpose of the trial that they hoped to address with digital technology, including logistical support, medical concerns, financial assistance, and counseling (119, 120).

Community-based research approaches that engage grassroots community agencies and peer researchers can be meaningfully involved in digital clinical trial planning and design, as well as in evaluating implementation to better understand successful approaches to bridging this digital divide (121). Community-based research strategies that meaningfully elicit perspectives from users across the research trajectory can also include conducting process evaluations at the end of trials to explore experiences and challenges with technology, particularly among persons with fewer socioeconomic resources. Studies could also be designed to interview persons who were excluded from digital clinical trials on the basis of their inability to meet technology inclusion criteria to better understand what type of clinical trial structure would better suit their lived realities and priorities.

CONCLUSION

Digital clinical trials, particularly in HIV research, offer incredible promise to improve efficiencies across biomedical and behavioral fields. In the variety of forms in which digital clinical trials can be designed and implemented, such trials offer an opportunity to overcome health inequities for individuals with transportation vulnerabilities and less access to health services and, by extension, to clinical research. By design, however, digital clinical trials also risk reproducing health inequities across multiple aspects of trial design and implementation. Although technology ownership continues to expand rapidly across the globe, consistent access continues to be hampered for many people by cost and digital infrastructure (15, 122). Exclusion of individuals with limited or inconsistent technology access is arguably a matter of representativeness and generalizability of an individual trial; however, it is important to consider the collective impact as digital trials and interventions are expanded. The accumulation of trials and evidence syntheses that collectively exclude the subgroups with less technology access risk reproducing health inequities as interventions found to be efficacious are integrated into HIV programming and brought to scale.

From an equity standpoint, trial design can be centered around the diversity of the target population’s reliable access to technology, technology use, and digital health literacy. Decisions in the design of digital clinical trials can be made to thoughtfully mitigate exclusion or, at a minimum, assess for biases associated with technology use and test alternative strategies for subgroups. We acknowledge that not all recommendations are possible or feasible given resource constraints, time, and efforts to maintain study rigor; however, they should be addressed to the extent possible and critically appraised during dissemination of findings. Where it is not possible to incorporate alternative methods, investigators should consider supplemental research to explore whether similar findings can be reproduced with other approaches designed to include populations missed by the original digital clinical trial. Donor agencies and grant reviewers are also responsible for evaluating whether interventions proposed in digital clinical trials have the potential to reproduce health inequities and whether efforts to mitigate these risks have been specified in the design stage. Furthermore, reviewers should consider proposals that test alternative or lower-technology options of an efficacious digital intervention if sample characteristics and attrition analysis suggest bias associated with the technology. This is a challenge, given the emphasis on innovation in grant applications, but one that is critical when evaluating whether an intervention is appropriate for scale-up in HIV programming and clinical services.

Interventions found to be effective in digital clinical trials and ultimately deployed within public health programming and medicine have the potential to reproduce health inequities if digital clinical trials and digital interventions are developed without attention to equity. The rapidly evolving technology environment suggests that full integration of technology into research and health services will become the norm within the next decade or so. In this moment, there is an opportunity to focus on designing trials with an emphasis on equity to ensure that groups most affected by or vulnerable to HIV have access to and can benefit from effective interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, United States (Andrea L. Wirtz); Department of Social Work, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Carmen H. Logie); and Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (Lawrence Mbuagbaw).

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number UG3/UH3AI133669 (to A.L.W.). This research has been facilitated by the infrastructure and resources provided by the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (grant 1P30AI094189), which is supported by the following NIH co-funding and participating institutes and centers: NIAID, National Cancer Institute, NICHD, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Findings presented here were produced via a review of published scientific manuscripts available in the peer-reviewed literature.

We acknowledge and appreciate the work by Sam Parker (Department of Social Work, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) to abstract data from identified articles.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Getz, K, The Cost of Clinical Trial Delays Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development; 2015; Available from: https://ctti-clinicaltrials.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/CTTI_PGCT_Meeting_Cost_Delays_Getz.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 2. Moore TJ, Zhang H, Anderson G, et al. Estimated costs of pivotal trials for novel therapeutic agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, 2015-2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1451–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lauer MS, Bonds D. Eliminating the “expensive” adjective for clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2014;167(4):419–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inan OT, Tenaerts P, Prindiville SA, et al. Digitizing clinical trials. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2020;3(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perry B, Geoghegan C, Lin L, et al. Patient preferences for using mobile technologies in clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;15:100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steinhubl SR, Wolff-Hughes DL, Nilsen W, et al. Digital clinical trials: creating a vision for the future. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2019;2(1):126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pew Research, Mobile fact sheet. Washington DC: Pew Research; 2021; Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed May 15, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Digital Health: Draft Resolution Proposed by Algeria, Australia, Brazil, Estonia, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Mauritius, Morocco, Panama, Philippines and South Africa, in A71/A/CONF./1. Geneva: Seventy-First World Health Assembly; 2018. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_ACONF1-en.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . WHO Guideline: Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550505. Accessed May 10, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Institutes of Health . RFAAI16031: Limited Interaction Targeted Epidemiology (LITE) to Advance HIV Prevention (UG3/UH3). National Institutes of Health; 2016. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/rfa-ai-16-031.html. Accessed May 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coran P, Goldsack JC, Grandinetti CA, et al. Advancing the use of mobile technologies in clinical trials: recommendations from the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Digital Biomarkers. 2020;3(3):145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National institutes of Health . Revitalization Act of 1993 Public Law 103–43: Subtitle B—Clinical Research Equity Regarding Women and Minorities. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1993. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK236531/. Accessed May 15, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Venter W, Coleman J, Chan VL, et al. Improving linkage to HIV care through Mobile phone apps: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(7):e155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silver, L. Smartphone Ownership Is Growing Rapidly Around the World, but Not Always Equally. Pew Research; 2019. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/02/05/smartphone-ownership-is-growing-rapidly-around-the-world-but-not-always-equally/. Accessed: May 27, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fang ML, Canham SL, Battersby L, et al. Exploring privilege in the digital divide: implications for theory, policy, and practice. Gerontologist. 2019;59(1):e1–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Logie C, Okumu M, Hakiza R, et al. Mobile health–supported HIV self-testing strategy among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda: protocol for a cluster randomized trial (Tushirikiane, supporting each other). JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(2):e26192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roser, M, Ortiz-Ospina, E. Literacy. Global Change Data Lab; 2018. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/literacy. Accessed May 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Logie CH, Okumu M, Kibuuka Musoke D, et al. The role of context in shaping HIV testing and prevention engagement among urban refugee and displaced adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda: findings from a qualitative study. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(5):572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stopponi MA, Alexander GL, McClure JB, et al. Recruitment to a randomized web-based nutritional intervention trial: characteristics of participants compared to non-participants. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(3):e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Norton BL, Person AK, Castillo C, et al. Barriers to using text message appointment reminders in an HIV clinic. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(1):86–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van der Kop ML, Muhula S, Nagide PI, et al. Effect of an interactive text-messaging service on patient retention during the first year of HIV care in Kenya (WelTel retain): an open-label, randomised parallel-group study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(3):e143–e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steward WT, Agnew E, de Kadt J, et al. Impact of SMS and peer navigation on retention in HIV care among adults in South Africa: results of a three-arm cluster randomized controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(8):e25774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jentzsch N. Implications of mandatory registration of mobile phone users in Africa. Telecomm Policy. 2012;36(8):608–620. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gilliard C. Pedagogy and the logic of platforms. Educause Review. 2017. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/7/pedagogy-and-the-logic-of-platforms. Accessed October 2, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friedline T, Chen Z. Digital redlining and the Fintech marketplace: evidence from U.S. zip codes. J Consum Aff. 2021;55(2):366–388. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown C, Czerniewicz L. Debunking the ‘digital native’: beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. J Comput Assist Learn. 2010;26(5):357–369. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nadaf AH. “Lockdown within a lockdown”: the “digital redlining” and paralyzed online teaching during COVID-19 in Kashmir, a conflict territory. Commun Cult Crit. 2021;14:343–346. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sevelius JM, Gutierrez-Mock L, Zamudio-Haas S, et al. Research with marginalized communities: challenges to continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2009–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shaw J, Brewer LC, Veinot T. Recommendations for health equity and virtual care arising from the COVID-19 pandemic: narrative review. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(4):e23233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. MacCarthy S, Hoffmann M, Ferguson L, et al. The HIV care cascade: models, measures and moving forward. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):19395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Swendeman D, Arnold EM, Harris D, et al. Text-messaging, online peer support group, and coaching strategies to optimize the HIV prevention continuum for youth: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(8):e11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hightow-Weidman LB, Bauermeister JA. Engagement in mHealth behavioral interventions for HIV prevention and care: making sense of the metrics. mHealth. 2020;6:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grov C, Westmoreland D, Rendina HJ, et al. Seeing is believing? Unique capabilities of internet-only studies as a tool for implementation research on HIV prevention for men who have sex with men: a review of studies and methodological considerations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S253–S260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS . End Inequalities. End AIDS. Global AIDS Strategy 2021–2026. Geneva: United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS; 2021. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-strategy-2021-2026_en.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37. United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS , 2020 Global AIDS Update — Seizing the Moment—Tackling Entrenched Inequalities to End Epidemics. Geneva: United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS; 2020. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/global-aids-report. Accessed May 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Johns MM, et al. Innovative recruitment using online networks: lessons learned from an online study of alcohol and other drug use utilizing a web-based, respondent-driven sampling (webRDS) strategy. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(5):834–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bragard E, Fisher CB, Curtis BL. “They know what they are getting into:” researchers confront the benefits and challenges of online recruitment for HIV research. Ethics Behav. 2020;30(7):481–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beymer MR, Holloway IW, Grov C. Comparing self-reported demographic and sexual behavioral factors among men who have sex with men recruited through mechanical Turk, Qualtrics, and a HIV/STI clinic-based sample: implications for researchers and providers. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(1):133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Castro Á, Barrada JR. Dating apps and their sociodemographic and psychosocial correlates: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ogunbajo A, Lodge W, Restar AJ, et al. Correlates of geosocial networking applications (GSN apps) usage among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Nigeria, Africa. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50(7):2981–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sullivan PS, Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, et al. National trends in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness, willingness and use among United States men who have sex with men recruited online, 2013 through 2017. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(3):e25461–e25461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jennings JM, Wagner J, Tilchin C, et al. Methamphetamine use, syphilis and specific online sex partner meeting venues are associated with HIV status among urban black gay and bisexual men who have sex men. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(8S):S32–S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Connor L, O'Donnell K, Barrett P, et al. Use of geosocial networking applications is independently associated with diagnosis of STI among men who have sex with men testing for STIs: findings from the cross-sectional MSM internet survey Ireland (MISI) 2015. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(4):279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Allen JE, Mansergh G, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Mobile phone and internet use mostly for sex-seeking and associations with sexually transmitted infections and sample characteristics among black/African American and Hispanic/Latino men who have sex with men in 3 US cities. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(5):284–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grov C, Westmoreland D, Morrison C, et al. The crisis we are not talking about: one-in-three annual HIV seroconversions among sexual and gender minorities were persistent methamphetamine users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(3):272–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Balán IC, Lopez-Rios J, Nayak S, et al. SMARTtest: a smartphone app to facilitate HIV and syphilis self- and partner-testing, interpretation of results, and linkage to care. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(5):1560–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arrington-Sanders R, Hailey-Fair K, Wirtz A, et al. Providing unique support for health study among young black and Latinx men who have sex with men and young black and Latinx transgender women living in 3 urban cities in the United States: protocol for a coach-based mobile-enhanced randomized control trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(9):e17269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wirtz AL, Iyer JR, Brooks D, et al. An evaluation of assumptions underlying respondent-driven sampling and the social contexts of sexual and gender minority youth participating in HIV clinical trials in the United States. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(5):e25694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Raymond HF, Chen YH, McFarland W. “Starfish sampling”: a novel, hybrid approach to recruiting hidden populations. J Urban Health. 2019;96(1):55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arayasirikul S, Chen Y-H, Jin H, et al. A Web 2.0 and epidemiology mash-up: using respondent-driven sampling in combination with social network site recruitment to reach young transwomen. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(6):1265–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wirtz AL, Cooney EE, Chaudhry A, et al. Computer-mediated communication to facilitate synchronous online focus group discussions: feasibility study for qualitative HIV research among transgender women across the United States. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wirtz AL, Cooney EE, Stevenson M, et al. Digital epidemiologic research on multilevel risks for HIV acquisition and other health outcomes among transgender women in eastern and southern United States: protocol for an online cohort. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(4):e29152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wirtz AL, Poteat T, Radix A, et al. American cohort to study HIV acquisition among transgender women in high-risk areas (the LITE study): protocol for a multisite prospective cohort study in the eastern and southern United States. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(10):e14704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tofighi B, Durr M, Marini C, et al. A mixed-methods evaluation of the feasibility of a medical management-based text messaging intervention combined with buprenorphine in primary care. Subst Abuse. 2022;16:11782218221078253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Reback CJ, Fletcher JB, Kisler KA. Text messaging improves HIV care continuum outcomes among young adult trans women living with HIV: text me, girl! AIDS Behav. 2021;25(9):3011–3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Labrique AB, Kirk GD, Westergaard RP, et al. Ethical issues in mHealth research involving persons living with HIV/AIDS and substance abuse. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013:189645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mbuagbaw L, Hajizadeh A, Wang A, et al. Overview of systematic reviews on strategies to improve treatment initiation, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for people living with HIV: part 1. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e034793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Roth AM, Holmes AM, Stump TE, et al. Can lay health workers promote better medical self-management by persons living with HIV? An evaluation of the positive choices program. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. da Costa TM, Barbosa BJ, Gomes e Costa DA, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of a mobile SMS-based intervention on treatment adherence in HIV/AIDS-infected Brazilian women and impressions and satisfaction with respect to incoming messages. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(4):257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jennings Mayo-Wilson L, Coleman J, Timbo F, et al. Microenterprise intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors and increase employment and HIV preventive practices among economically-vulnerable African-American Young adults (EMERGE): a feasibility randomized clinical trial. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(12):3545–3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stephenson R, Todd K, Kahle E, et al. Project moxie: results of a feasibility study of a telehealth intervention to increase HIV testing among binary and nonbinary transgender youth. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(5):1517–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shuter J, Kim RS, An LC, et al. Feasibility of a smartphone-based tobacco treatment for HIV-infected smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(3):398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Logie CH, Wang Y, Marcus N, et al. Factors associated with the separate and concurrent experiences of food and housing insecurity among women living with HIV in Canada. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3100–3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]