Abstract

Purpose:

Radiation-induced lymphopenia has gained attention recently as the result of its correlation with survival in a range of indications, particularly when combining radiation therapy (RT) with immunotherapy. The purpose of this study is to use a dynamic blood circulation model combined with observed lymphocyte depletion in patients to derive the in vivo radiosensitivity of circulating lymphocytes and study the effect of RT delivery parameters.

Methods and Materials:

We assembled a cohort of 17 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with proton RT alone in 15 fractions (fx) using conventional dose rates (beam-on time [BOT], 120 seconds) for whom weekly absolute lymphocyte counts (ALCs) during RT and follow-up were available. We used HEDOS, a time-dependent, whole-body, blood flow computational framework, in combination with explicit liver blood flow modeling, to calculate the dose volume histograms for circulating lymphocytes for changing BOTs (1 second-300 seconds) and fractionations (5 fx, 15 fx). From this, we used the linear cell survival model and an exponential model to determine patient-specific lymphocyte radiation sensitivity, α, and recovery, σ, respectively.

Results:

The in vivo−derived patient-specific α had a median of 0.65 Gy−1 (range, 0.30–1.38). Decreasing BOT to 1 second led to an increased average end-of-treatment ALC of 27.5%, increasing to 60.3% when combined with the 5-fx regimen. Decreasing to 5 fx at the conventional dose rate led to an increase of 17.0% on average. The benefit of both increasing dose rate and reducing the number of fractions was patient specific patients with highly sensitive lymphocytes benefited most from decreasing BOT, whereas patients with slow lymphocyte recovery benefited most from the shorter fractionation regimen.

Conclusions:

We observed that increasing dose rate at the same fractionation reduced ALC depletion more significantly than reducing the number of fractions. High-dose-rates led to an increased sparing of lymphocytes when shortening the fractionation regimen, particularly for patients with radiosensitive lymphocytes at elevated risk.

Introduction

With the increasing use of immunotherapy agents in combined treatment regimens involving radiation therapy (RT), greater attention is being paid to the immune-suppressive effects of fractionated RT, such as radiation-induced lymphopenia (RIL).1 The absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) during RT increasingly is being studied as the result of its correlation with progression and overall survival in patients after RT.2,3 The dynamics of lymphocyte depletion during RT have been well described4 and absolute cell counts,5 recovery,6 and nadir7 have been used as predictors. Circulating lymphocytes typically receive a low accumulated dose throughout treatment compared with the prescribed tumor dose8; however, they are likely highly radiosensitive.9,10

Although substantial research has been performed correlating ALC with outcome,9–14 few studies have investigated the effect of different fractionation schemes and dose rates,15 and even fewer have investigated the effects on individual patients. This is because, until recently,8,16 we were not able to estimate the dose to circulating lymphocytes in a fashion that considers fractionation and dose rate appropriately. Furthermore, RIL is a complex phenomenon and although has been shown that dose to large blood vessels is important,17 dose to lymph nodes close to the tumor and other lymphocyte-rich organs, such as spleen18 and bone marrow,19 also contributes to RIL. In this study, we aim to isolate the effect of dose on circulating lymphocytes using a unique cohort of patients with liver cancer treated with proton RT only (no chemotherapy), in whom lymph nodes and other structures important for RIL receive no radiation dose. Together with recently developed methods combining dynamic blood flow simulations with realistic models of dose delivery,8,16,20 this enables us to estimate the in vivo radiosensitivity of circulating lymphocytes in individual patients and investigate the effect of changing dose rate and fractionation.

Methods and Materials

Patient cohort

Our study was approved by the institutional review board committee and is based on data from 17 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated in 15 fractions (fx) at our institution between 2011 and 2014 as part of a clinical trial (NCT03186898), where we collected 3 to 12 ALC measurements with an average of 7 measurements per patient. ALC measurements were collected at day 1 before (baseline), during (day 8–20), and after treatment (after day 21). All patients were treated with passively scattered proton therapy without chemotherapy, receiving on average a total dose of 58 Gy (median) with a relative biological effectiveness of 1.1. The median volume of the gross target volume and whole liver were 107.1 and 1590.8 cm3, respectively. The detailed patient characteristics have been published previously and are described in Hong et al21 and Sung et al.22

Blood-flow simulations and accumulated dose

The Monte Carlo system, TOPAS20 (version 3.6.0), was used to simulate each passively scattered proton beam based on the RT treatment plans and generate 3-dimensional dose distributions. These dose distributions were imported into MIMVista (MIM Software, Cleveland, OH) and deformably registered to the male or female adult ICRP reference phantom liver based on the sex of the patient.23 These simulations were performed individually for each patient in the liver-specific iteration of HEDOS-4D16 to derive the accumulated dose to circulating lymphocytes in the bloodstream using dose-volume histograms (bDVH) during RT (Fig. 1A). A total of 100,000 blood particles were simulated using a time step of 0.5 seconds for a total simulation time of 1350 seconds. We simulated 2 clinically common fractionation regimens (5 fx or 15 fx) and a range of dose rates leading to beam-on times (BOT) from 1 second to 5 minutes (1 second, 5 seconds, 10 seconds, 30 seconds, 45 seconds, 60 seconds, conventional - 120 seconds, and 300 seconds). The dose to irradiated blood particles was reset after each fraction, assuming sufficient time for complete mixing and complete repair of remaining lymphocytes.

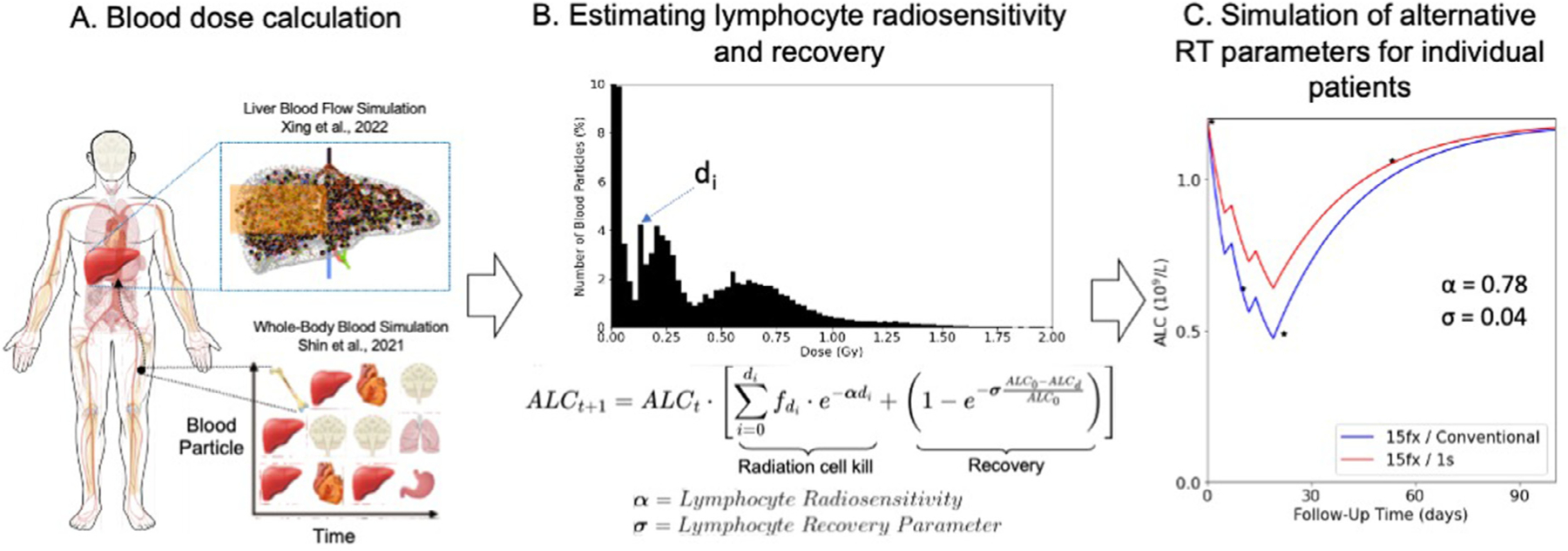

Fig. 1.

Overview of methods for blood dose calculation (A, left), estimating lymphocyte radiosensitivity and recovery (B, middle), and patient-specific estimate of lymphocyte depletion across alternative RT parameters (C, right). Abbreviations: ALC = absolute lymphocyte count; RT = radiation therapy.

The treatment regimen and dose rate that were used to treat the patients (15 fractions using 2 Gy/min) were used to derive the in vivo radiosensitivity. The 5-fx regimen use adjusted prescription doses based on clinical trial NCT03186898 for the hypofractionated simulations according to the following: if Dmax <50 Gy, then adjust to 6 Gy/fx, if Dmax ≥50 Gy and Dmax ≤67.5 Gy, then adjust to 8 Gy/fx, and if Dmax >67.5 Gy then adjust to 10 Gy/fx.

Estimation of in vivo radiosensitivity

To model the depletion of circulating lymphocytes in the bloodstream after being exposed to a given bDVH from HEDOS-4D (Fig. 1A), we applied a linear cell survival model to the predicted bDVH (Fig. 1B). The lymphocyte recovery was modeled as an exponential recovery process dependent on the patient’s baseline ALC, as described in the second term in the equation in Fig. 1B. The final proposed model for lymphocyte depletion and recovery can thus be represented as follows:

where α is the lymphocyte radiosensitivity parameter and σ is the lymphocyte recovery parameter, which describes the recovery of lymphocytes in between fractions and after RT. Based on the observed ALC depletion and recovery in the patients, these parameters were fit individually to each patient. To enable easier interpretation of the lymphocyte recovery parameter, we convert it to the number of days needed to recover to 80% of a patient’s baseline ALC in the results.

A grid search method was applied to find the optimal combination of α and σ for each patient using the residual sum of squares as an optimality criterion between the simulated and observed ALC depletion and recovery. Depletion occurred only during RT on weekdays (ie, no weekend treatments) once per day, whereas recovery was assumed to be ongoing throughout treatment. Lymphocyte depletion and recovery was modeled up until 300 days posttreatment start and can be seen in Fig. 1C for an example patient (with x-axis cutoff at 100 days due to rapid lymphocyte recovery).

Results

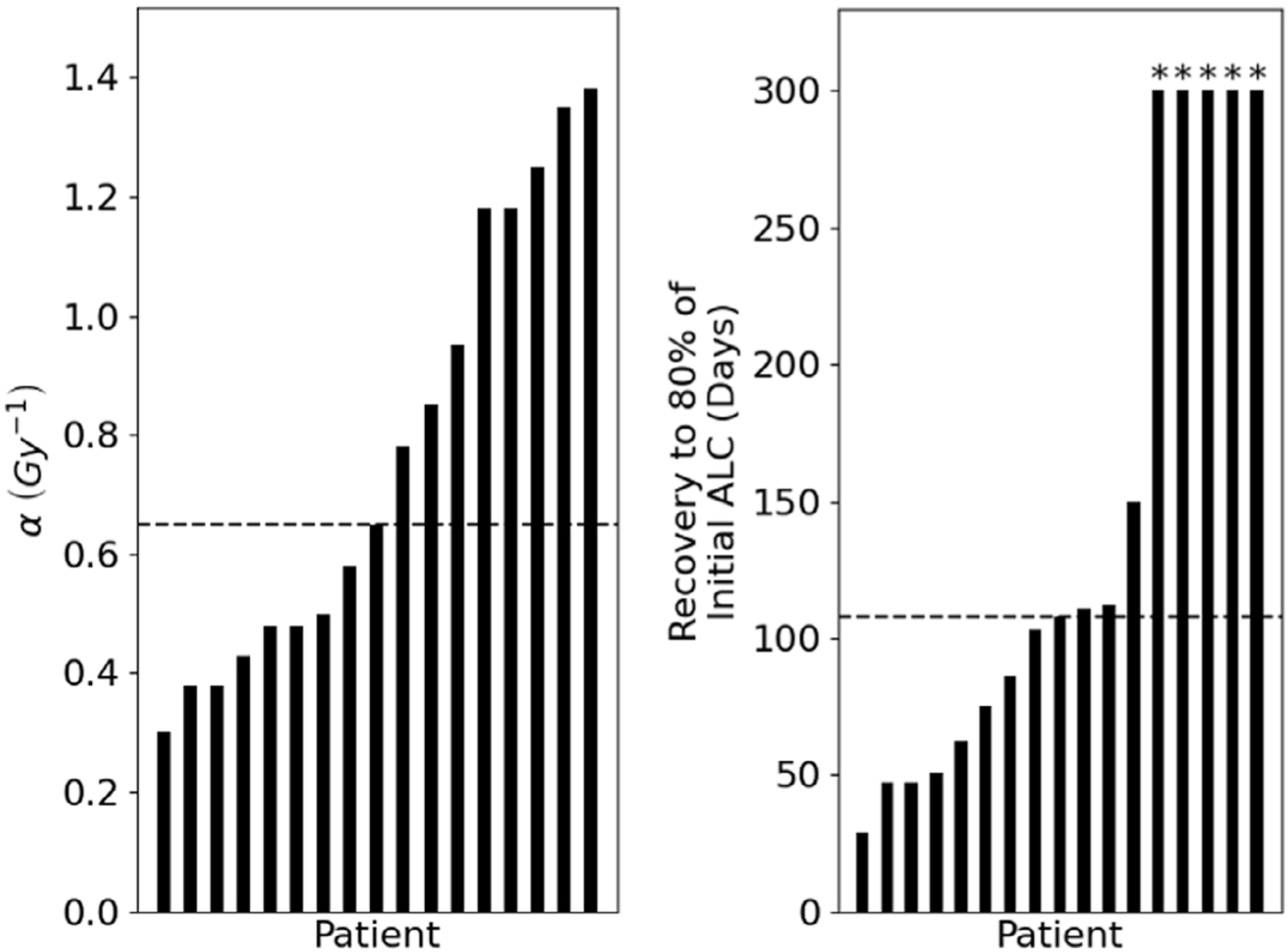

The best-fit α values for each patient range from 0.30 Gy−1 to 1.38 Gy−1 with a median of 0.65 Gy−1 (Fig. 2A). The best-fit lymphocyte recovery parameter σ has a median of 0.02 (range, 0.0075–0.04). The number of days required to reach 80% of the baseline ALC after treatment end, which is directly related to σ, was 108 days for the median patient (range, 29–150 days) when excluding 4 patients whose recovery was predicted to be longer than our simulated time of 300 days from treatment start (Fig. 2B). The predicted ALC dynamics of an example patient can be seen in Fig. 1C.

Fig. 2.

Waterfall plot of a (A, left) and number of days until recovery to 80% of initial ALC (B, right) with overlying median line (dashed) in both figures. *Note: for 4 patients, the recovery was predicted to be longer than the simulated length of 300 days from treatment start. Abbreviation: ALC = absolute lymphocyte count.

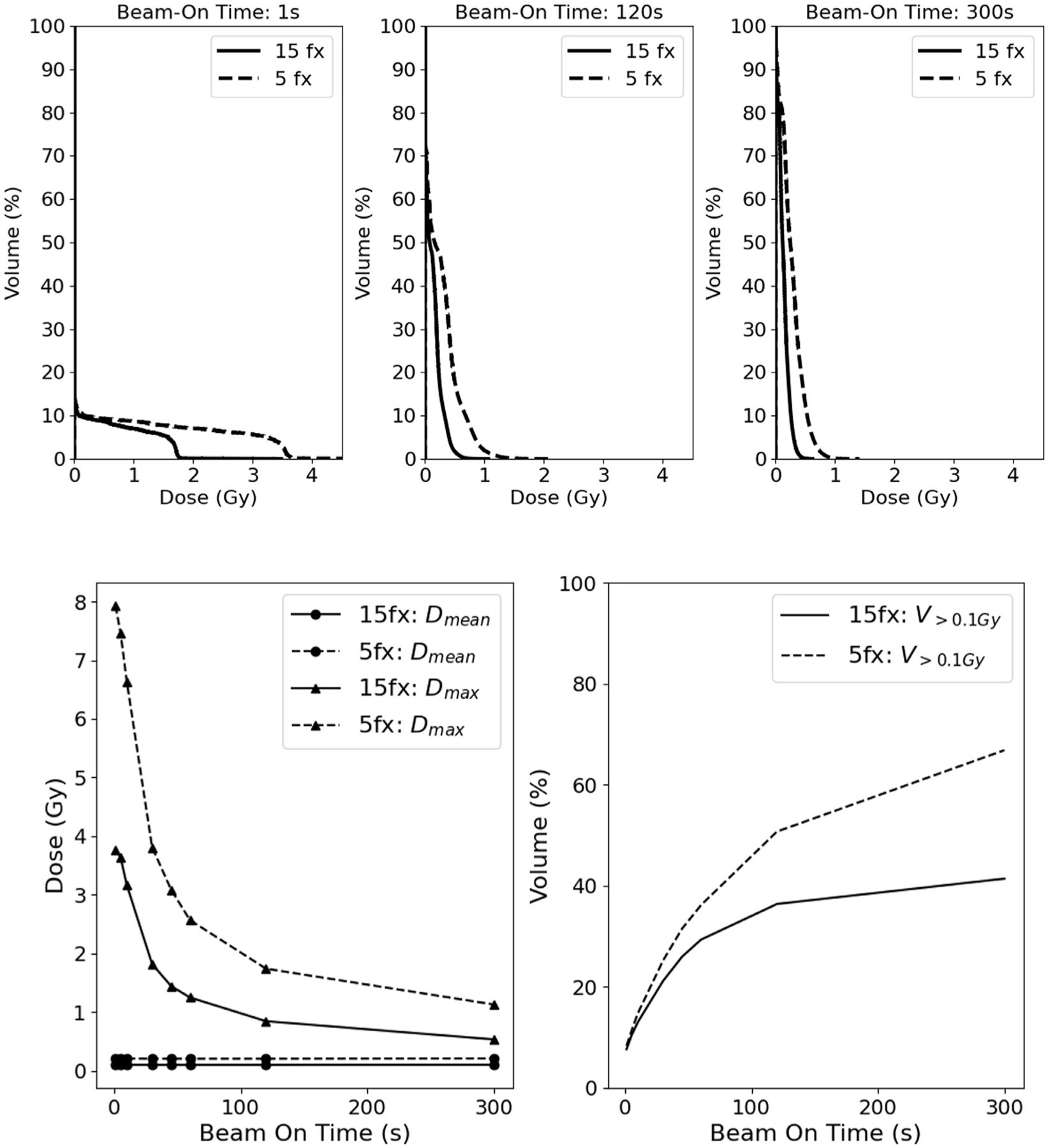

Next, we calculated the bDVHs for the 5-fx regimen and a range of dose rates, which changes the shape of the bDVH, as demonstrated in Fig. 3. For very short treatment times (Fig. 3A), a high percentage of lymphocytes receive no dose, and a small percentage of lymphocytes receive high doses up to the prescribed dose delivered in a fraction. As the dose rate decreases (Fig. 3 B and C), the percentage of lymphocytes that receive dose increases but the dose is more spread out among them and they experience an increasingly smaller maximum dose. As shown in Fig. 3D, the mean dose (Dmean) to the lymphocytes for both the 5-fx and 15-fx treatment regimens remains the same at 0.2 Gy and 0.1 Gy, respectively across all BOT. However, the maximum dose (Dmax) for both the 5-fx and 15-fx treatment regimens shows a strong decrease with increasing BOT. A similar trend was seen across all patients for both Dmean and Dmax across BOT. The percentage volume of lymphocytes receiving at least 0.1 Gy (V>0.1Gy) is shown in Fig. 3E, rising from 8.3% and 7.6% at very high-dose-rates to 66.8% and 41.4% for a 5-minute BOT, for 5-fx and 15-fx treatments, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the cumulative per fraction bDVH for a 1-second (A, top left), 120-second (B, top middle), and 300-second (C, top right) beam-on time for a sample patient and quantitative comparison of bDVH mean dose, Dmean (D, bottom left), maximum dose, Dmax (D, bottom left), and volume of lymphocytes receiving greater than 0.1 Gy, V>0.1Gy (E, bottom right) taking the mean across all patients between conventional and hypofractionated regimens. Abbreviation: bDVH = bloodstream dose-volume histograms.

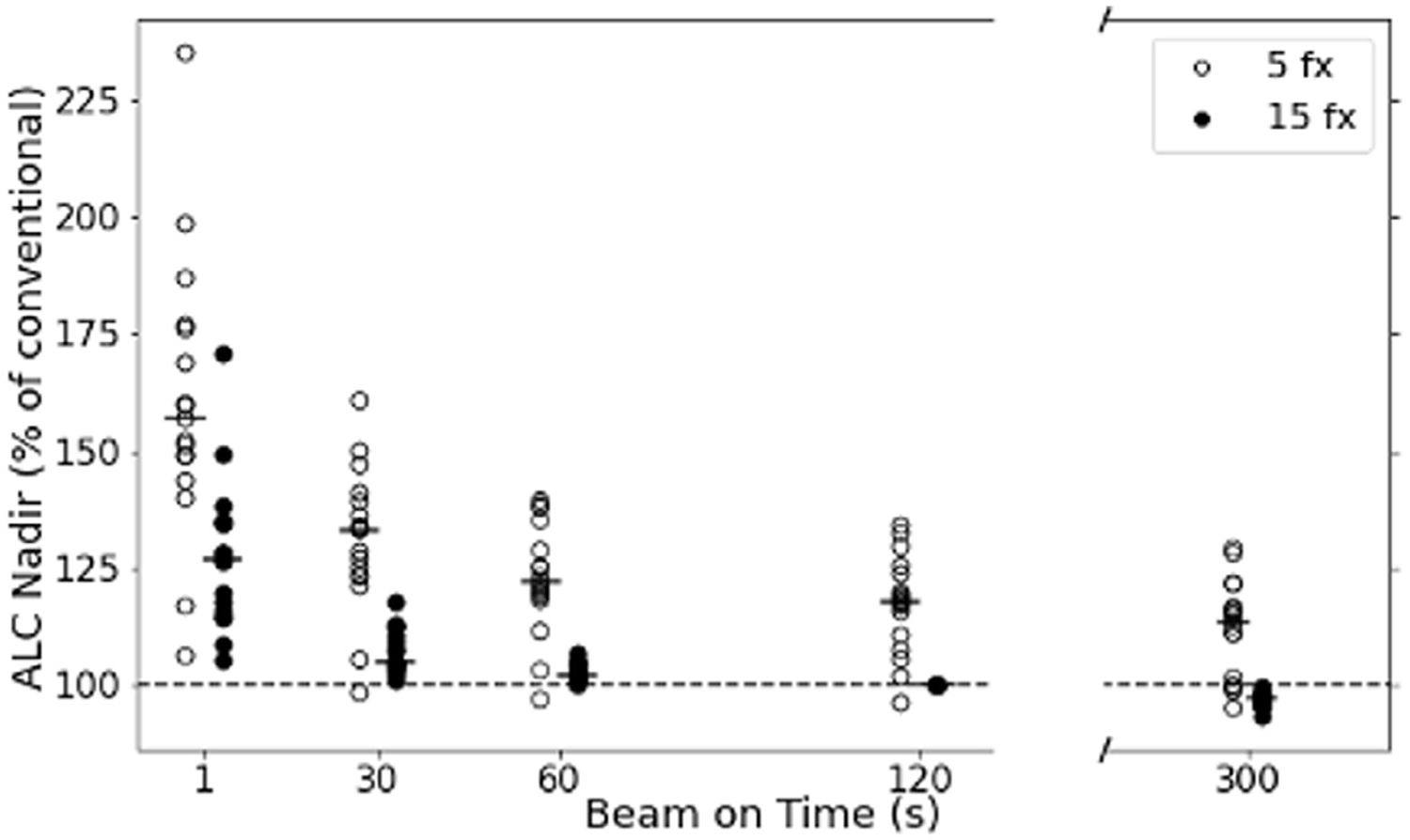

Figure 4 describes the expected changes to the patient-specific lymphocyte nadir when changing fractionation and dose rate from the conventional scenario (15-fx, 120-second BOT). The largest benefit in ALC nadir is expected from the hypofractionated regimen with a very high dose-rate (5 fx/1 second) with a mean increase of 60.3% across all patients. Very high dose rates also improve the ALC nadir for the 15-fx regimen, although only by 27.5% on average, with a few patients experiencing a decrease in ALC nadir with the increased dose rate. This is the case for patients with very radioresistant lymphocytes, where irradiation of a larger blood volume leads to very little additional lymphocyte loss and is further investigated to follow. When changing the fractionation from 15 to 5 fractions without increasing the dose rate, the expected mean benefit is an ALC increase of 17.0%, again with some patients not experiencing a benefit. For very long BOT at conventional fractionation, we estimate small decreases in ALC nadir of ~3% on average.

Fig. 4.

The relative changes in ALC nadir compared with the conventional treatment regimen across beam-on times and fractionation schedules. The hollow circles are 5 fractions and the filled circles are 15 fractions whereas the respective median change is represented with a line for each column. Abbreviation: ALC = absolute lymphocyte count.

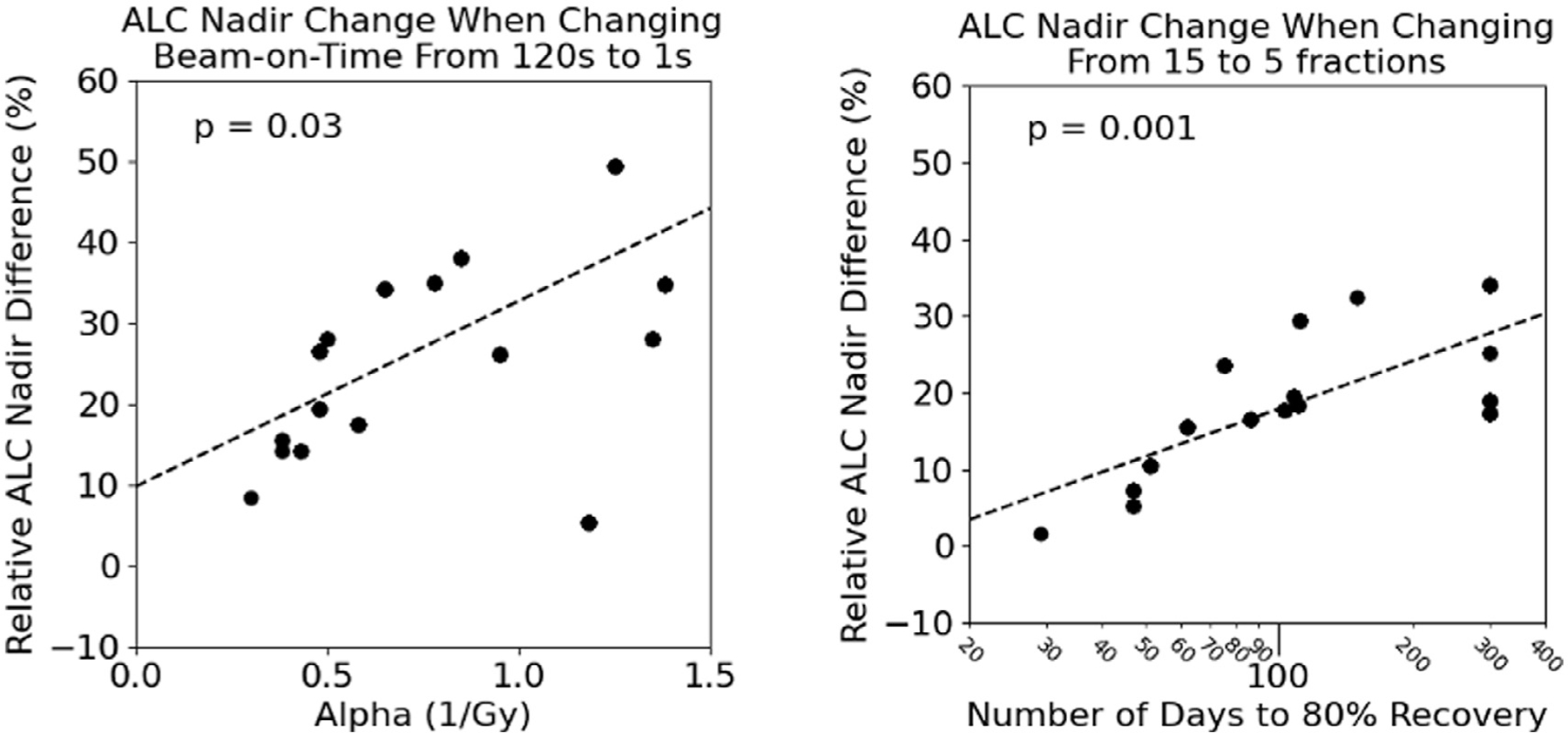

To investigate this heterogeneity in benefit for individual patients, we correlated the changes in ALC nadir to the patient-specific lymphocyte radiosensitivity, α, and the number of days to 80% lymphocyte recovery. Figure 5A shows the relationship between the ALC benefit of switching to a very high-dose-rate and lymphocyte radiosensitivity (P = .03) for a 15-fx regimen. The benefit becomes stronger with increasing α, that is, the more radiosensitive a patient’s lymphocytes, the more benefit they can expect from a greater dose rate. For patients with very radioresistant lymphocytes, although the benefit is small (ie, <10%), Fig. 5B shows a similar relationship, this time for the ALC benefit when switching from 15 to 5 fx, and its correlation to the number of days to 80% lymphocyte recovery (P = .001). Patients with a slower lymphocyte recovery derive increased benefit from hypofractionation compared with patients with faster recovery, with even a negative effect if the ALC recovers rapidly.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between the lymphocyte radiosensitivity term, α, and the ALC nadir difference when increasing the dose rate (fractionation kept constant at 15 fractions) (A, left) and the relationship between the number of days to recovery to 80% ALC baseline (in log scale) and the ALC nadir difference when shortening fractionation from 15 to 5 fractions (beam-on time kept constant at 120 seconds) (B, right). The P value was determined from the Pearson correlation coefficient. Crosses denote a negative ALC nadir difference, whereas the circles denote a positive ALC nadir difference. Abbreviation: ALC = absolute lymphocyte count.

Discussion

This study combined recently developed tools to calculate dose to circulating lymphocytes with a unique patient cohort to derive patient-specific lymphocyte sensitivity and recovery for individual patients. The patients did not receive chemotherapy, neither before RT nor during the period of lymphocyte depletion and recovery that we studied. Because of the specific location of the tumor and the use of proton therapy, no other tissues apart from the liver received significant dose. The median lymphocyte radiosensitivity that we estimated for our patient cohort is similar to in vitro results of Nakamura et al24 and Geara et al25; however, there was a wide range across patients. This demonstrates how unreliable it can be to use a population-based radiosensitivity value to estimate the effect of a treatment plan on lymphocyte depletion for an individual patient. However, because of the consistency of lymphocyte dynamics during RT, a lymphocyte count early during RT can be used to estimate the lymphocyte radiosensitivity for specific patients and predict lymphopenia, as shown by Ellsworth et al.4

The correlations between lymphocyte radiosensitivity and the increased benefit of rapid dose delivery, as well as the correlations between recovery and the increased benefits of hypofractionated RT, could be used to stratify patients. High-dose-rates benefit patients with known risk factors for lymphopenia (for example, low baseline lymphocyte count, infectious disease status, autoimmune disorders, extensive drop early during treatment), whereas hypofractionation would benefit patients at risk of slow recovery (for instance, smoking status26). Our results regarding the benefit of fractionation agree with clinical data: according to Pike et al,13 the ALC percent change from initial levels at RT start was most affected by increased fractionation schemes >5 fx, which agrees with the data of this study, considering most of their patients had persistent lymphopenia 1-month post-RT start, indicating a slower recovery to 80% of baseline ALC. In addition, according to Saito et al,14 each fraction increases the risk of grade 3 or greater lymphopenia by a factor of 1.18 (P = .036). The predicted ALC recovery, including the occurrence of persistent lymphopenia, agrees with previous literature studying the period after RT.17,27,28 In a mathematical study by Jin et al,15 FLASH appeared to reduce kill to circulating immune cells and this sparing effect decreases with decreasing dose per fraction and almost vanishes when the dose is reduced to 2 Gy/fx. This sparing effect is also noticed to decrease when the irradiation volume increases and vanishes when the total body is irradiated.16,17 We show that fast dose-delivery, even if not at the level of inducing FLASH effects, can already show benefit for radiosensitive patients when BOT are lowered to <30 seconds, with increasing benefit the faster the dose is delivered. Zhang et al29 collated available data to investigate the potential of FLASH to differentially affect the immune landscape, including circulating immune cells. Their assessment is in line with our findings, suggesting that fast irradiation can spare circulating lymphocytes and thus reduce the likelihood of lymphopenia.

It should be noted that our estimates for lymphocyte sparing at high dose rates only relate to the reduced amount of circulating blood irradiated. Possible FLASH sparing effects of lymphocytes have not been considered here. However, Venkatesulu et al30 investigated normal tissue sparing in cardiac and splenic irradiations of 10 Gy at 35 Gy/s (<0.3 seconds) and found that ultrahigh-dose-rate irradiations were equally potent in depleting CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD19 lymphocyte populations in both cardiac and splenic irradiation models of lymphopenia. Their data suggest that there may not be an additional FLASH sparing effect for lymphocytes. However, because their radiation fields included organs that contain large fractions of noncirculating lymphocytes (for instance, the spleen), it is not possible to draw conclusions for treatment scenarios that primarily affect circulating lymphocytes. As Zhang et al29 pointed out, more experimental data are needed to determine the effect of irradiating lower volumes of circulating lymphocytes.

Although the cohort of patients is small (n = 17) and their ALC responses are heterogenous, this was a hypothesis-generating study to examine the effects of altering RT delivery techniques on lymphocyte depletion. Although in our case there were no lymph nodes or lymphatic vessels in the field, similar studies for other treatment sites also need to consider dose to noncirculating lymphocytes with a potential correlation between lymphocyte recovery and radiosensitivity. On average, there is an estimated 2.6% of lymphocytes circulating in the blood whereas approximately 65% are in the lymph nodes, 21% are in the spleen, and 8.3% are in the Peyer’s patches.31 Therefore, future work will focus on modeling dose to these other critical static structures which may still be significantly affected by radiation for certain treatment sites (that is, head and neck). The treatment regimens used in this study reflect the 2 most common schedules for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and are based on an ongoing clinical trial (NCT03186898); however, alternate fractionation schemes are employed, particularly on an international level32 and should be considered.

The accuracy of the linear dose-response model for lymphocytes used in this study could affected by 2 sources of uncertainty. First, the radiation-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes in vitro peaks only after 72 hours,33 although the effect is smaller for lower doses,34 which could lead to small systematic shift in fitted radiosensitivity values. Other possible deviations from the linear model that could affect our results are the reported hyper-radiosensitivity of cells at low doses (<80 cGy35,36) and the observed adaptive response of human lymphocytes to multiple doses of DNA-damaging agents,37 both of which apply to the majority of lymphocytes irradiated each fraction. A median of 60% of lymphocytes in our patients received doses of 0 to 80 cGy per fraction for treatments with conventional dose rates.

Although some of the noted limitations here may affect the magnitude of observed changes, the general trends observed in the data are robust, that is, the benefit of increased dose rates on radiosensitive patients as well as the benefit of hypofractionation for patients with slower lymphocyte recovery will remain. Future work will focus on further characterizing this trend across more complex treatment sites and defining more robust patient lymphocyte radiosensitivity and recovery cutoffs for deriving the largest benefit of increased dose rates and hypofractionation.

Conclusions

Although there exists a degree of patient-specific uncertainty, using a high-dose-rate treatment regimen can be a useful tool for maximizing a patient’s ALC during and after RT. The benefit depends on the patient’s radiosensitivity, with the patients at greatest risk of severe lymphopenia deriving the largest benefit. Similarly, hypofractionation can be useful to minimize RIL, its effect dependent on the patient’s ability to repopulate lost lymphocytes. In all scenarios, slowing down the dose rate to less than conventionally used values has little effect. Further study is needed to better understand how technical developments in RT delivery affect the immunologic effects of RT. Finally, validation of these simulation results, either through experiments undertaken in mouse models or by studying patient cohorts treated with different dose rates (single-arc volumetric modulated arc therapy) is important to judge the possible effect to reduce the risk and severity of RIL.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NIH/NCI) grants R21 CA248118 (to C.G.), R21 CA241918 (to C.G.), R01 CA248901 (to H.P.), P01 CA261669 (to T.H., R. M., H.P., S.L., and C.G.), and R21 CA252562 (to Ja.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Ja.S. reports grants from NIH/NCI, awards from the Damon Runyon Foundation and the Brain Tumor Charity, travel support from Particle Therapy Co-Operative Group, and leadership roles in the Radiation Research Society (VP-Elect). T.H. reports institutional grants from Taiho Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, IntraOp, Tesaro, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Ipsen; consulting fees from Merck, Synthetic Biologics, Novocure, Syndax, and Boston Scientific; and stock in PanTher Therapeutics. D.D. reports grants from Surface Oncology, Bayer, BMS, and Exelixis and consulting fees from Innocoll. S.L. reports grants from STCube Pharmaceuticals, grants from Beyond Spring Pharmaceuticals, grants from Nektar Therapeutics, other from Creatv Microtech, other from AstraZeneca Inc, and other from XRAD Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. C.M. C.-A., J.W., and W.B. report salary support from NIH/NCI R01 CA248901. S.D. reports salary support from NIH/NCI U01 EB028234.

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Fuks Z, Strober S, Bobrove AM, Sasazuxi T, Mcmichma A, Kaplan HS. Long term effects of radiation on T and B lymphocytes in peripheral blood of patients with Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Invest 1976;58:803–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venkatesulu BP, Mallick S, Lin SH, Krishnan S. A systematic review of the influence of radiation-induced lymphopenia on survival outcomes in solid tumors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018;123:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damen PJJ, Kroese TE, van Hillegersberg R, et al. The influence of severe radiation-induced lymphopenia on overall survival in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;111:936–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellsworth SG, Yalamanchali A, Zhang H, Grossman SA, Hobbs R, Jin JY. Comprehensive analysis of the kinetics of radiation-induced lymphocyte loss in patients treated with external beam radiation therapy. Radiat Res 2019;193:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr BI, Metes DM. Peripheral blood lymphocyte depletion after hepatic arterial 90Yttrium microsphere therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:1179–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S, Chen MG, Gastineau DA, et al. Effect of slow lymphocyte recovery and type of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis on relapse after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001;28:951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afghahi A, Purington N, Han SS, et al. Higher absolute lymphocyte counts predict lower mortality from early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2851–2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin J, Xing S, McCullum L, et al. HEDOS-a computational tool to assess radiation dose to circulating blood cells during external beam radiotherapy based on whole-body blood flow simulations. Phys Med Biol 2021;66. 10.1088/1361-6560/ac16ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafson MP, Bornschlegl S, Park SS, et al. Comprehensive assessment of circulating immune cell populations in response to stereotactic body radiation therapy in patients with liver cancer. Adv Radiat Oncol 2017;2:540–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yovino S, Kleinberg L, Grossman SA, Narayanan M, Ford E. The etiology of treatment-related lymphopenia in patients with malignant gliomas: Modeling radiation dose to circulating lymphocytes explains clinical observations and suggests methods of modifying the impact of radiation on immune cells. Cancer Invest 2013;31:140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Working MRC, Maclennan ICM, Kay HEM. Analysis of treatment in childhood leukemia. IV. The critical association between dose fractionation and immunosuppression induced by cranial irradiation. Cancer 1978;41:108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun GY, Wang SL, Song YW, et al. Radiation-induced lymphopenia predicts poorer prognosis in patients with breast cancer: A post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial of postmastectomy hypofractionated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;108:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pike LRG, Bang A, Mahal BA, et al. The impact of radiation therapy on lymphocyte count and survival in metastatic cancer patients receiving PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019;103:142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito T, Toya R, Matsuyama T, Semba A, Oya N. Dosimetric predictors of treatment-related lymphopenia induced by palliative radiotherapy: Predictive ability of dose-volume parameters based on body surface contour. Radiol Oncol 2017;51:228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin JY, Gu A, Wang W, Oleinick NL, Machtay M, (Spring) Kong FM. Ultra-high dose rate effect on circulating immune cells: A potential mechanism for FLASH effect? Radiother Oncol 2020;149:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing S, Shin J, Pursley J, et al. A dynamic blood flow model to compute absorbed dose to circulating blood and lymphocytes in liver external beam radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol 2022;67. 10.1088/1361-6560/ac4da4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho O, Chun M, Kim SW, Jung YS, Yim H. Lymphopenia as a potential predictor of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence in early breast cancer. Anticancer Res 2019;39:4467–4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexandru M, Rodica A, Dragos-Eugen G, Mihai-Teodor G. Assessing the spleen as an organ at risk in radiation therapy and its relationship with radiation-induced lymphopenia: A retrospective study and literature review. Adv Radiat Oncol 2021;6 100761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sini C, Fiorino C, Perna L, et al. Dose-volume effects for pelvic bone marrow in predicting hematological toxicity in prostate cancer radiotherapy with pelvic node irradiation. Radiother Oncol 2016;118:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perl J, Shin J, Schümann J, Faddegon B, Paganetti H. TOPAS: An innovative proton Monte Carlo platform for research and clinical applications. Med Phys 2012;39:6818–6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong TS, Wo JY, Yeap BY, et al. Multi-institutional phase II study of high-dose hypofractionated proton beam therapy in patients with localized, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sung W, Grassberger C, McNamara AL, et al. A tumor-immune interaction model for hepatocellular carcinoma based on measured lymphocyte counts in patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2020;151:73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valentin J Basic anatomical and physiological data for use in radiological protection: reference values: ICRP publication 89: approved by the commission in September 2001. Ann ICRP 2002;32:5–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura N, Kusunoki Y, Akiyama M. Radiosensitivity of CD4 or CD8 positive human T-lymphocytes by an in vitro colony. Radiat Res 1990;123:224–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geara FB, Peters LJ, Ang KK, et al. Intrinsic radiosensitivity of normal human fibroblasts and lymphocytes after high- and low-dose-rate irradiation. Cancer Res 1992;52:6348–6352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verma R, Foster RE, Horgan K, et al. Lymphocyte depletion and repopulation after chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2016;18:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng W, Xu C, Liu A, et al. The relationship of lymphocyte recovery and prognosis of esophageal cancer patients with severe radiation-induced lymphopenia after chemoradiation therapy. Radiother Oncol 2019;133:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho Y, Kim Y, Chamseddine I, et al. Lymphocyte dynamics during and after chemo-radiation correlate to dose and outcome in stage III NSCLC patients undergoing maintenance immunotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2022;168:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Ding Z, Perentesis JP, Khuntia D, Pfister SX, Sharma RA. Can rational combination of ultra-high dose rate FLASH radiotherapy with immunotherapy provide a novel approach to cancer treatment? Clin Oncol 2021;33:713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatesulu BP, Sharma A, Pollard-Larkin JM, et al. Ultra high dose rate (35 Gy/sec) radiation does not spare the normal tissue in cardiac and splenic models of lymphopenia and gastrointestinal syndrome. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):17180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganusov VV, Auerbach J. Mathematical modeling reveals kinetics of lymphocyte recirculation in the whole organism. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10 e1003586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Komatsu S, Fukumoto T, Demizu Y, et al. Clinical results and risk factors of proton and carbon ion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2011;117:4890–4904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boreham DR, Gale KL, Maves SR, Walker JA, Morrison DP. Radiation-induced apoptosis in human lymphocytes: Potential as a biological dosimeter. Health Phys 1996;71:685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bordón E, Henríquez Hernández LA, Lara PC, et al. Prediction of clinical toxicity in localized cervical carcinoma by radio-induced apoptosis study in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs). Radiat Oncol 2009;4:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Słonina D, Biesaga B, Janecka A, Kabat D, Bukowska-Strakova K, Gasińska A. Low-dose hyper-radiosensitivity is not a common effect in normal asynchronous and G2-phase fibroblasts of cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;88:369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Słonina D, Gasińska A, Biesaga B, Janecka A, Kabat D. An association between low-dose hyper-radiosensitivity and the early G2-phase checkpoint in normal fibroblasts of cancer patients. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016;39:41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cregan SP, Brown DL, Mitchel RE. Apoptosis and the adaptive response in human lymphocytes. Int J Radiat Biol 1999;75:1087–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]