Abstract

Context.

Surges in the ongoing Coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic and accompanying increases in hospitalizations continue to strain hospital systems. Identifying hospital-level characteristics associated with COVID-19 hospitalization rates and clusters of hospitalization “hot-spots” can help with hospital system planning and resource allocation.

Objective.

To identify 1) hospital catchment area-level characteristics associated with higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates and 2) geographic regions with high and low COVID-19 hospitalization rates across catchment areas during COVID-19 Omicron surge (12/20/2021–4/3/2022).

Design.

This observational study used Veterans Health Administration (VHA), U.S. Health Resource & Services Administration’s Area Health Resources File, and U.S. Census data. We used multivariate regression to identified hospital catchment area-level characteristics associated with COVID-19 hospitalization rates. We used ESRI ArcMap’s Getis-Ord Gi* statistic to identify catchment area clusters of hospitalization hot and cold spots.

Setting & Participants.

VHA hospital catchment areas in the U.S. (n=143)

Main Outcome Measures.

Hospitalization rate

Results.

Greater COVID-19 hospitalization was associated with serving more high-hospitalization risk patients (34.2 hospitalizations/10,000 patients per 10-percentage point increase in high-hospitalization risk patients, 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 29.4,39.0), fewer patients new to VHA during the pandemic (−3.9, 95%CI: −6.2, −1.6), and fewer COVID vaccine-boosted patients (−5.2, 95%CI: −7.9, −2.5).

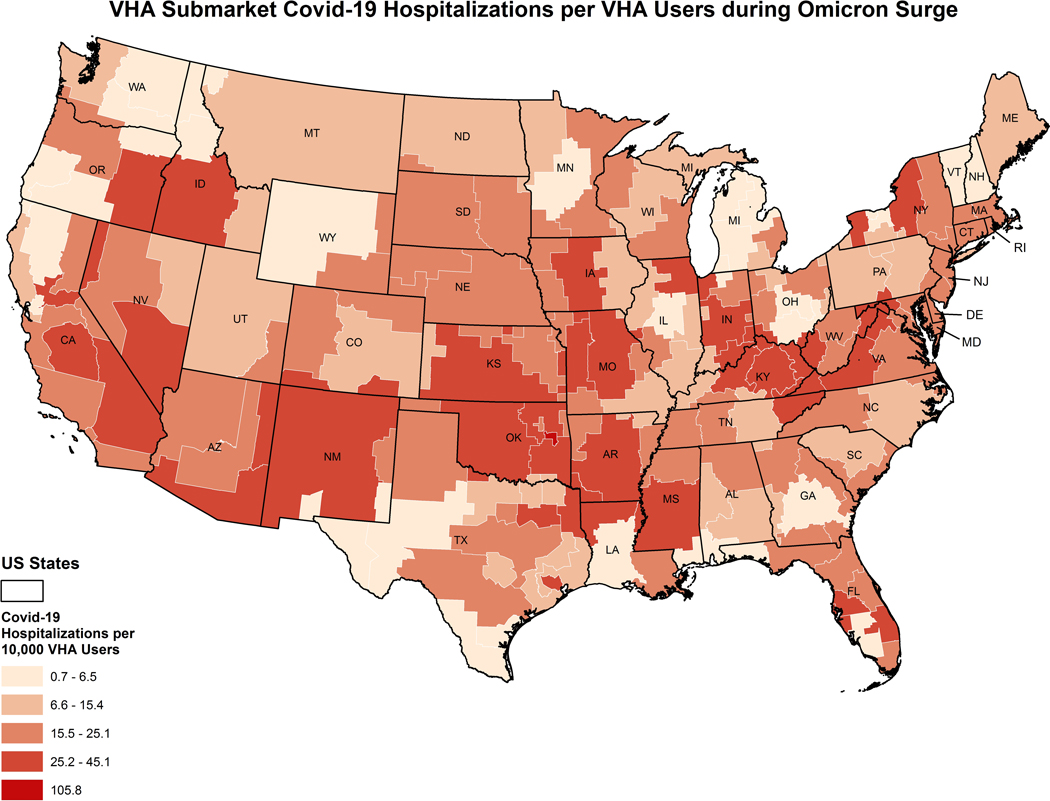

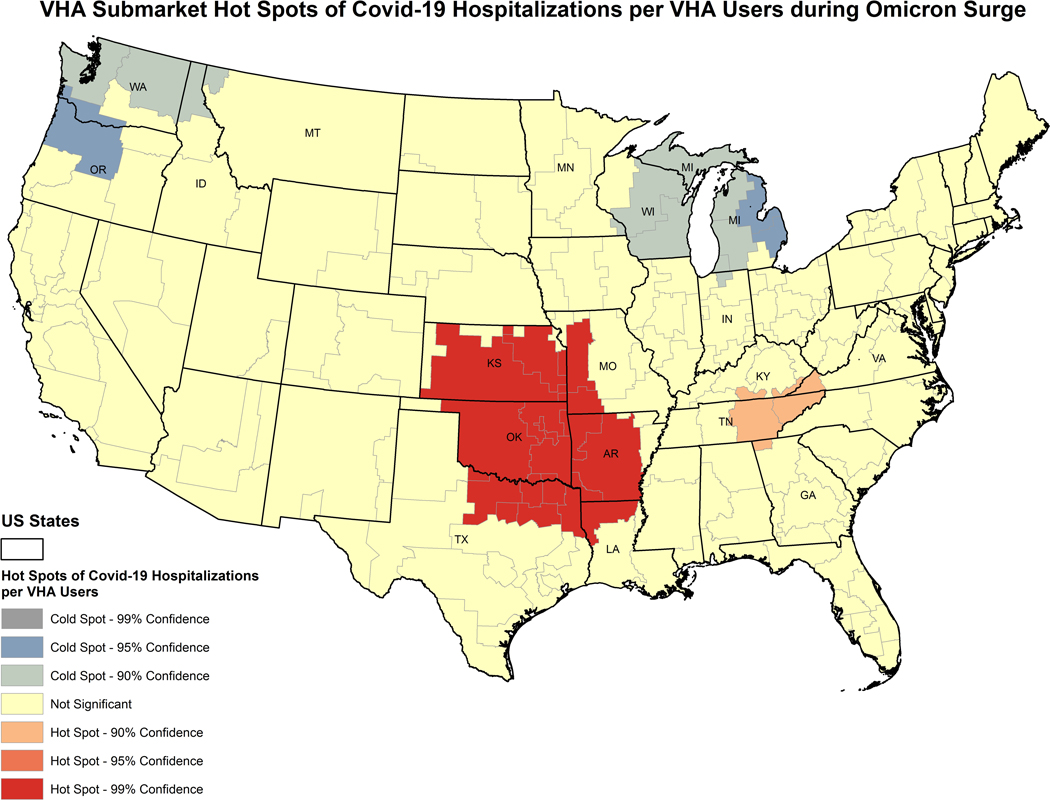

We identified two hospitalization cold spots located in the Pacific Northwest and in the Great Lakes regions, and two hot spots in the Great Plains and Southeastern U.S. regions.

Conclusions.

Within VHA’s nationally integrated healthcare system, catchment areas serving a larger high-hospitalization risk patient population were associated with more Omicron-related hospitalizations, while serving more patients fully vaccinated and boosted for COVID-19 and new VHA-users were associated with lower hospitalization. Hospital and healthcare system efforts to vaccinate patients, particularly high-risk patients, can potentially safeguard against pandemic surges.

Hospitalization hot spots within VHA include states with a high burden of chronic disease in the Great Plains and Southeastern U.S.

Keywords: Veterans, COVID-19, Geographic Information Systems, Resource Allocation

Background:

The Coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has evolved considerably since its emergence. The COVID-19 surge driven by the Omicron variant differs from previous surges and variants. Omicron appears to be more transmissible but less severe than previous strains,1,2 with fewer hospitalizations, shorter hospital stays,3 and lower mortality among those infected.4 Availability of vaccines and effective therapeutic treatments, increased knowledge about social and medical risk factors affecting transmission and disease severity, and effective infection control measures have helped reduce COVID-19 mortality and hospitalization.5,6 As a result, the COVID-19 estimated case fatality rate is lower now than earlier in the pandemic.

However, COVID-19-related hospitalization remains a concern because a sudden and significant increase in hospitalizations can still strain hospital systems. During the initial Omicron surge, the influx of COVID-19 patients stressed many hospitals resulting in long Emergency Department wait times, hospitals at capacity, and insufficient staffing.7,8 Thus, as new variants continue to emerge, it is crucial to understand hospital-level factors that may contribute to hospitals becoming overwhelmed. Yet, existing COVID-19 studies have primarily focused on patient-level factors related to infection and outcomes, such as health and demographic characteristics9 and social determinants of health (i.e., non-healthcare factors that affect health)10. Few studies have considered characteristics of hospitals and hospital catchment areas associated with hospitals being overwhelmed by COVID-19 surges,11–13 information that can inform hospital and public health systems to proactively protect healthcare infrastructure.

Potentially relevant hospital catchment area characteristics include a patient population with greater social vulnerability, older age, or higher-risk for hospitalization and mortality, limited healthcare resources (e.g., location within a health professional shortage area), and healthcare system and regional vaccination efforts. Patients with fewer healthcare resources or greater socially vulnerability may delay care until they are sicker, elevating hospitalization rates in those catchment areas.14,15 Hospitals that serve patients with underlying risk factors for serious COVID-19 (e.g., advanced age or underlying comorbidities)16 may be strained from both the baseline complex case mix of their patient population and that populations’ increased COVID-19 risk. Conversely, given the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing hospitalization,17 serving a patient population with high vaccine coverage can help reduce the influx of COVID-19 patients during surges.

Moreover, it is also important to consider whether high COVID-19 hospitalization rates “cluster” (i.e., whether higher or lower concentrations of hospitalizations group together geographically) across multiple hospital catchment areas, because hospitals do not exist in isolation from each other. Adjacent hospital catchment areas may have similar area-level characteristics, such as community-level social vulnerability linked to the spillover of hospitalizations. Clustering of high hospitalization rate catchment areas is particularly salient in the current pandemic, where county and state public health policies and regional cultural norms have strongly influenced COVID-19’s spread and severity. Even with the less severe Omicron variant, COVID-19 hospitalizations still overwhelmed hospitals in some regions of the United States.18 However, less is known about clustering across multiple hospital catchment areas. Understanding both individual catchment-area level characteristics and clusters of hospital catchment areas can help regional and national healthcare systems identify potentially vulnerable hospitals regions, inform capacity, and direct system resources.19,20

To fill these research gaps, we 1) identified hospital catchment area-level characteristics associated with a higher proportion of COVID-19 hospitalizations during the initial COVID-19 Omicron surge (12/20/2021–4/3/2022), and 2) conducted a “hot spot” analysis to identify where hospital catchment areas with concentrations of low and high COVID-19 hospitalization rates are geographically located. We conducted our analysis in the national network of Veteran Health Administration (VHA) hospitals – the largest integrated hospital network in the United States.

Methods.

Sample and Data.

Our unit of analysis for this study was hospital catchment areas (“VHA Submarkets”), used to aggregate and report service usage among the VHA-user population.21 Our sample included all VHA catchment areas in the US. Veterans were assigned to catchment areas based upon the facility where they sought most of their care. We included Veterans in a catchment area if they had any VHA outpatient or inpatient visit between 3/1/2019–4/3/2022. We excluded individuals with potentially erroneous COVID-19 vaccine information. We obtained Veteran-level characteristics from VHA electronic medical records and the VHA COVID-19 Shared Data Resource, which is a collection of COVID-19-related data sources from both VHA and non-VHA sources,22 then aggregated these data to the hospital catchment area level. We obtained information about health professional shortage areas (HPSA) from U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA)’s 2020 Area Health Resources File (AHRF), and poverty area census tracts from the 2015–2019 American Community Survey.

Variables.

Our key dependent variable was a continuous measure of the number of VHA-users within the hospital catchment area that had a COVID-19 hospitalization during the Omicron surge period per 10,000 VHA-users in the catchment area. We defined relevant hospitalizations as being a COVID-19 related hospitalization between 0–14 days after testing positive for COVID-19 between 12/20/21 – 4/3/22 (when the original Omicron strain was dominant).23

Key independent variables were guided by the Andersen Behavioral Model.24 This model characterizes drivers of healthcare utilization—in this case, Omicron-related hospitalization – into predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Predisposing factors include individual-level factors potentially influencing healthcare use (e.g., demographic, and social factors). Enabling factors relate to organizational factors enabling individuals to use services (e.g., factors influencing healthcare access and community-level resources). Need factors encompass patient and population-level health considerations. Our measures were:

Predisposing: % of female Veterans, Veterans 80+ years old, low-income or military service-connected disabled Veterans, non-Hispanic Black Veterans, Hispanic Veterans, other racial/ethnic minoritized Veterans, new VHA-users

Enabling: % of patients living in a high-poverty census tract, patients living in a HPSA county, patients who reside 60+ minutes driving time to their nearest VHA facility25

Need: % of patients boosted for COVID-19, fully vaccinated for COVID-19/not boosted, partially vaccinated for COVID-19, at high hospitalization-risk.

We constructed continuous catchment area-level characteristics by first obtaining Veteran-level information on each characteristic, and then calculating the proportion of Veterans within the catchment area with each characteristic. Among predisposing factors, we categorized Veterans as having low-income if they did not have a service-connected disability, but qualified for free or reduced VHA co-payment. We combined this group with Veterans with service-connected disability, as these groups may have greater medical or socioeconomic needs. We identified new VHA-users as individuals with no VHA service use during the two-years prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (3/1/2018–2/29/2020). These individuals may differ from existing users in ways that affect VHA utilization. For example, new VHA-users may have pandemic-related causes for using VHA care (e.g., change in financial status or health, loss of job and employer-based health insurance) that VHA may not have accounted for when allocating resources across facilities. New patients may increase caseloads, which can strain a hospital system if resources to serve patients have not kept pace with growing demand for care. Conversely, existing users have established relationships with VHA providers and greater VHA care continuity.

Among enabling factors, we used the U.S. Census’s definition of a poverty area census tract as having ≥20% of the census tract population below the poverty line.26 We considered Veterans who resided in counties either entirely or partially in a HRSA-defined HPSA as living in an HPSA county.27

For need factors, we identified Veterans at high risk for 90-day hospitalization as having a VHA Care Assessment Need (CAN) score ≥90th percentile.28 CAN scores predict hospitalization from healthcare utilization and medication in the prior year.29 We categorized vaccination status based on COVID-19 vaccination date, type, and number of doses: boosted (2 mRNA vaccine doses or 1 adenovirus vaccine dose + mRNA booster), fully vaccinated/not boosted (2 mRNA vaccine doses or 1 adenovirus vaccine dose), and partially vaccinated (1 mRNA vaccine dose). Higher vaccination rates may indicate greater healthcare facility-level COVID-19 prevention efforts.

Statistical analysis.

Catchment area-level characteristics:

We analyzed catchment area-level characteristics by calculating univariate summary statistics of means, percentages, and standard deviation for each characteristic, and mean number of Omicron-related hospitalization per 10,000 VHA-users. We also tested bivariate associations between each characteristic and hospitalization.

Informed by our conceptual framework, we sequentially fit three multi-variate regression models to test associations with hospitalization: (1): predisposing factors, (2): predisposing and enabling factors, and (3): predisposing, enabling, and need factors. To aid in interpreting the results, we expressed associations of each catchment area characteristic with hospitalization as changes in hospitalizations per 10,000 per 10 percentage-point increase in the catchment area characteristic. We considered p-values <0.05 as statistically significant. These analyses were conducted in Stata 17.0 (College Station, TX).

COVID-19 hospitalization hot spot analysis:

We conducted our spatial analyses of COVID-19 hospitalizations in a subsample consisting of catchment areas within the contiguous U.S. We first provided a descriptive spatial analysis with a choropleth map of hospitalization rates in VHA catchment areas. We divided the hospitalization values into five ordinal categories, using the Jenks Natural Breaks Classification Method, which groups similar values together by minimizing variance within each category, while maximizing variance between categories.30 We then mapped U.S. state boundaries on top of the choropleth map.

We then conducted hot spot analysis to identify regional concentrations of high and low hospitalizations standardized by VHA-users in catchment areas. We utilized the Getis-Ord Gi* (Gi*) statistic or hot spot analysis to compare each catchment area’s hospitalization rate relative to others in its immediate vicinity. An optimized distance band was implemented such that every region has at least one nearest neighbor but not the complete set of areas from the global dataset. If a particular area and others surrounding it contained a higher or lower than expected sum of values, too extreme to be the result of random processes when compared proportionally to the global sum of catchment area values, that area was marked as a hot/cold spot with a significant Z-score.31 We then layered U.S. state boundaries on top of the analysis to present results in map. Hot spot analyses were conducted with Esri’s ArcMap (version 10.5).

The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved these analyses.

Results.

In the 143 hospital catchment areas, on average, 9% of VHA users were female, 16% were 80+ years old, 83% had low-income or service-connection disability, 14% were non-Hispanic Black, 6% were Hispanic, 3% identified as another racial/ethnic minoritized group, and 20% were new VHA-users (Table 1). Twenty-three percent of patient populations resided in a “poverty area” census tract, 93% in a HPSA county, and 3% had to travel >60 minutes to a VHA facility. The mean proportion of boosted patients was 32%, and patients with high-hospitalization risk was 9%. Mean Omicron-related hospitalizations was 18.2 per 10,000 patients.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Hospital Catchment Areas

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Predisposing Factors | |

| Female, % | 8.5 (2.6) |

| Age 80+, % | 16.0 (4.3) |

| Low Income or service connected, % | 83.0 (4.9) |

| Racial/ethnic composition | |

| Non-Hispanic Black, % | 13.8 (13.1) |

| Hispanic, % | 6.3 (10.8) |

| Other Minoritized Groups*, % | 3.0 (6.7) |

| New VA patients†, % | 20.0 (6.1) |

| Enabling Factors | |

| Residing in “poverty area” census tract‡, % | 22.6 (14.5) |

| Residing in Heath Professional Shortage Area county§, % | 93.2 (9.8) |

| Drive Time 60+ minutes, % | 3.2 (5.0) |

| Need Factors | |

| COVID-19 vaccination status | |

| Boostedll, % | 32.0 (6.8) |

| Fully vaccinated, but not boosted**, % | 26.9 (3.6) |

| Partially vaccinated†† | 2.0 (0.9) |

| High-hospitalization Risk, % | 8.8 (3.2) |

| Hospitalization | |

| Omicron-related hospitalizations, per 10,000 patients | 18.2 (12.6) |

Notes:

American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, multi-race

Did not have VHA inpatient/outpatient visit in 2 years prior to pandemic

U.S. Census defines “poverty area” as 20% or more of the census tract below the poverty line

Either part or whole county defined as a Health Professional Shortage Area

Received 2 mRNA + booster or 1 adenovirus + booster

Received 2 mRNA or 1 adenovirus vaccine(s)

Received 1 mRNA vaccine

Catchment area-level characteristics:

Table 2 presents associations between catchment area characteristics and Omicron hospitalizations. In bivariate analyses, having a larger percentage of new patients was associated with lower Omicron-related hospitalizations (−6.63 hospitalizations/10,000 patients for each 10-percentage point increase in new VHA patients, 95% confidence interval [CI]:−9.87,−3.40) (Table 2). A larger proportion of patients residing in “poverty area” census tracts (1.51,95%CI: 0.09,2.93) and high-hospitalization risk patients (29.74, 95%CI:25.64,33.85) had higher hospitalizations.

Table 2.

Hospital catchment area characteristics associated with Omicron hospitalization from 12/20/2021–4/3/2022

| Characteristics | Difference in number of hospitalizations per 10,000 patients† (95%CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate Relationships | Model 1: Predisposing Factors | Model 2: Predisposing + Enabling Factors | Model 3: Predisposing, Enabling + Need Factors | |

| Predisposing Factors | ||||

| % Female | 1.38 (−6.50, 9.25) | –10.34 (−24.13, 3.46) | 3.11 (−14.40, 20.62) | 5.85 (−5.01, 16.70) |

| % Age 80+ | –1.09 (−5.90, 3.72) | 0.34 (−8.76, 9.44) | 2.04 (−7.07, 11.15) | 2.30 (−3.67, 8.28) |

| % Low income or service connected | 4.51 (−1.53, 10.54) | 7.22 (0.88, 13.57)* | 3.89 (−2.92, 10.70) | 3.45 (−0.82. 7.72) |

| % non-Hispanic Black | 1.34 (−0.24, 2.91) | 1.50 (−0.69, 3.70) | –0.68 (−3.60, 2.24) | –0.86 (−2.82, 1.09) |

| % Hispanic | –0.31 (−2.24, 1.63) | –1.12 (−3.16. 0.93) | –2.37 (−4.63, −0.11)* | –0.74 (−2.40, 0.92) |

| % Other Minoritized Group‡ | –1.29 (−4.39, 1.82) | –0.71 (−3.83, 2.40) | –2.49 (−5.87, 0.89) | 1.97 (−0.35, 4.28) |

| % New VA Patients§ | –6.63 (−9.87, −3.40)* | –7.38 (−10.83, −3.93)* | –7.82 (−11.35, −4.29)* | –3.88 (−6.16, −1.59)* |

| Enabling Factors | ||||

| % Residing in “poverty area” census tractll | 1.51 (0.09, 2.93)* | 2.77 (0.57, 4.97)* | –0.06 (−1.55, 1.42) | |

| % Residing in HPSA county** | –1.19 (−3.30, 0.91) | –0.11 (−2.13, 1.91) | 0.29 (−0.96, 1.55) | |

| % Drive time 60+ minutes | –2.51 (−6.67, 1.66) | –0.66 (−5.01, 3.68) | 0.94 (−1.81, 3.68) | |

| Need Factors | ||||

| % Boosted†† | 1.87 (−1.16, 4.90) | –5.19 (−7.91, −2.47)* | ||

| % Fully vaccinated, but not boosted‡‡ | –2.94 (−8.65, 2.78) | 1.57 (−19.16, 22.30) | ||

| % Partially vaccinated§§ | –9.29 (−33.3, 14.7) | –1.92 (−6.13, 2.28) | ||

| % High hospitalization risk | 29.74 (25.64, 33.85)* | 34.17 (29.39, 38.95)* | ||

Notes:

p-value <0.05

Per 10-percentage point increase in catchment area characteristics

American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, multi-race

Did not have VHA inpatient/outpatient visit in 2 years prior to pandemic

U.S. Census defines “poverty area” as 20% or more of the census tract below the poverty line

Either part or whole county defined as a Health Professional Shortage Area

Received 2 mRNA + booster or 1 adenovirus + booster

Received 2 mRNA or 1 adenovirus vaccines but no booster

Received 1 mRNA vaccine

In model 1, having larger proportions of low income or service-connected disability patients was associated with more hospitalization (7.22 (95%CI:0.88, 13.57), while larger proportions of new VHA patients were associated with lower hospitalization (−7.38 (95%CI:−10.83, −3.93). In model 2, the proportion of new VHA patients remained significant (−7.82, 95%CI:−11.35, −4.29). Having a higher proportion Hispanic patients was associated with lower hospitalizations (−2.37, 95%CI:−4.63, −0.11), while a higher proportion of patients residing in “poverty area” census tracts had more hospitalizations (2.77, 95%CI:0.57, 4.97). In model 3, having a larger proportion of high-hospitalization risk patients was associated with more hospitalizations (34.17, 95%CI:29.39, 38.95), while a larger proportion of boosted patients (−5.19, 95%CI:−7.91, −2.47) and new VHA-users (−3.88, 95%CI:−6.16, −1.59) had fewer Omicron-related hospitalizations.

Post-hoc analysis.

To further explore the new VA patients variable and changes between models, we calculated supplemental descriptive statistics of proportions and means of characteristic of new VHA-users, low-income or service-connected patients, Hispanic VHA-users, and those living in poverty census tracts, and those boosted (Appendix Tables 1–5). New VHA-users were more likely to be female (15%vs.9%), be younger (age <65 years: 58%vs.43%), reside in a poverty area census tract (58%vs.32%), drive >60 minutes to nearest VHA facility (48%vs.16%), and less likely to have low-income or service-connection (61%vs.78%), or boosted (22%vs.29%) than existing VHA-users. Low-income or service-connected patients were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (18%vs.12%), boosted (31% vs. 18%) and have high-hospitalization risk (9% vs. 3%) and less likely to be new VHA-users (22%vs.40%), reside in “poverty area” census tract (31%vs.60%) or drive >60 minutes to nearest VHA facility (14%vs.53%). Hispanic VHA-users were younger (mean age:56 yrs vs. 63 yrs), more likely to have low-income or have service-connected disability (82%vs.73%), reside in poverty area census tracts (45% vs. 39%), be boosted (31%vs.27%) and less likely to drive >60 minutes to nearest VHA facility (20%vs.25%) than non-Hispanic VHA-users. Meanwhile, residents of poverty census tracts were more likely than those of non-poverty census tracts to be non-Hispanic Black (20%vs.15%), be new VHA-users (40%vs.19%), drive >60 minutes to nearest VHA (59%vs.2%), and less likely have low-income or service-connected disability (59% vs. 83%), and boosted (18%vs.33%).

COVID-19 hospitalization hot spot analysis:

Figure 1 presents a choropleth Map of Hospitalization Rates in the contiguous U.S. Catchment-area hospitalization rates ranged from 0.7 to 105.8 hospitalization per 10,000 patients. Catchment areas in Northwestern and Midwestern states were among the lowest categories of hospitalization rates. Catchment areas with the highest rates were primarily located in the Southwestern and Great Plains regions. Great Basin and Southern states included both high and low hospitalization rate catchment areas. The catchment area with the largest hospitalization rate (105.8/10,000) was located in eastern Oklahoma; this region is an outlier, separated into its own category.

Figure 1.

Choropleth map of Omicron-related hospitalizations per 10,000 VHA users by VHA hospital catchment area (i.e., submarkets) during the initial Omicron surge (12/20/21 – 4/3/22)

Hot Spot Analysis of Hospitalization Rates.

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial clustering of catchment areas with high and low hospitalization rates. Most catchment areas do not form statistically significant concentrations of extreme hospitalization values. However, there are two “cold spots,” i.e., regions with catchment areas that form clusters with smaller than expected hospitalization rates. One cold spot is formed by two catchment areas across Washington, Oregon, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana. Three catchment areas across Wisconsin and Michigan form another cold spot. We also identified two “hot spots,” i.e., areas with concentrations of larger than expected hospitalization values. One hot spot consists of two catchment areas primarily in eastern Tennessee, extending into southern Kentucky, western Virginia, and northwest Georgia. The second is a comparatively large hot spot of 14 catchment areas spanning Kansas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, northern Louisiana, and northeast Texas, and constitutes the greatest concentration of extreme and high hospitalization rates.

Figure 2.

VHA hospital catchment area “hot” and “cold” spots of Omicron-related hospitalizations per 10,000 VHA-users

Discussion.

When accounting for predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of hospital patient populations, we found that, within VHA’s nationally integrated healthcare system, catchment areas serving a patient population with higher risk for hospitalization were associated with more omicron-related hospitalizations, while serving more patients boosted for COVID-19 and new VHA-users were associated with lower omicron-related hospitalization. We further identified two “hot spots” of high Omicron-related hospitalizations, a larger one spanning six states in the southern and greater plains region of the United States and a smaller region in the Southeastern United States.

Need factors were most strongly associated with Omicron-related hospitalization, especially serving more high-hospitalization risk patients. Despite Omicron generally being milder than previous COVID-19 strains,2,3 high-hospitalization risk patients remained at risk for severe COVID-19 and hospitalization. Conversely, having more patients boosted was associated with lower Omicron-related hospitalization, which is consistent with literature that COVID-19 boosters prevent COVID-19 hospitalization.32 Taken together, these findings suggest that hospitals should consider the underlying general hospitalization risk of their patient population, but also preventive efforts, such as vaccination, which can help mitigate a surge of COVID-19 hospitalization. This suggests approaches such as focusing early or more intensive outreach and prevention toward high-hospitalization risk patients as an efficient strategy that hospitals can implement to achieve early reductions in population risk.

Among predisposing factors, catchment areas with larger proportions of new VHA-users were consistently associated with fewer hospitalizations across all models. This is somewhat surprising, since new VHA patients were less likely to be vaccinated and more likely to reside in high-poverty census tracts, which are both factors for COVID-19.17,33,34 It is possible that new VHA-users had lower Omicron-related hospitalization risk, as we found that these were generally younger, working-age Veterans. However, more research is needed to better characterize new VHA-users’ healthcare utilization and needs, and whether they continue using VHA care as the pandemic’s economic turbulence wanes, as this has implications for future VHA planning and resource allocation. We also found that serving more Hispanic patients was associated with lower hospitalization after accounting for both predisposing and enabling factors, but no longer significant after accounting for need factors. This may be due to higher vaccination among Hispanic Veterans in our sample. Consistent with another study, we did not find an association between hospitals with more Black patients and COVID-19-related hospitalization.13

Our analyses included predisposing catchment-area characteristics based on individual-level factors associated with COVID-19, but were not significant at the catchment-level. Aggregating individuals to a geographic unit often yields results that differ from person-level analyses, emphasizing the value of examining relationships at both individual and catchment area-levels. For example, we did not find that serving an older patient population was associated with more hospitalization, despite evidence that older age is a risk factor for severe COVID-19.35 A potential explanation for this paradox is that older age is associated with greater adoption of personal COVID-19 mitigation behaviors.36

Enabling factors were no longer associated with Omicron-related hospitalization after accounting for need factors. Before accounting for need factors, the proportion of patients living in poverty area census tracts was associated with greater Omicron-related hospitalizations. Patients with high-hospitalization risk are also often socially vulnerable, including having low-income, having unstable housing, and living in impoverished neighborhoods.37 Our post-hoc analyses revealed that VHA-users in our sample residing in poverty area census tracts were less likely to be fully vaccinated. VHA and other healthcare systems can focus their vaccination outreach efforts on poverty-area census tracts. In our sample, those residing in poverty census tracts are also live further from VHA facilities, so outreach can include mobile vaccination or partnerships with local community-based organizations.

An unusual aspect of our analysis is that some catchment area characteristics were not significant in bivariate analyses but became significant after multivariate adjustment. These relationships with hospitalization are likely confounded by other catchment area characteristics. Post-hoc analyses of the characteristics of these patients elucidate how relationships may be obscured without accounting for confounders. For example, race and ethnicity often confound the relationship between income and health outcomes, and this may explain why low-income or service-connection only become significantly associated with hospitalization after accounting for race and ethnicity.

Our spatial analysis revealed two “hot spots” in the southern United States. These include regions with greater resistance to COVID-19 vaccination,38 and states that rank low in health outcomes, and have high prevalence of smoking and multiple chronic conditions39—both of which may increase risk for severe COVID-19. Of note, there are some catchment areas with high or lower hospitalization rates, but do not cluster with adjacent catchment areas into hot or cold spots, respectively. Both “cold spots” identified in our analysis, located in the Pacific Northwest and Great Lake region can provide insight into “positive deviance”: what we can learn from hospitals in “cold spots”. Future research may consider qualitative methods to dive deeper into whether and how hospitals in “hot” and “cold spots” responded differently to the Omicron surge, and the regional longer-term effects of pandemic surges in “hot spots” (e.g., patient care, provider burnout).

Limitations of our catchment area characteristic analysis include limited generalizability to non-VHA-user populations, omission of non-VHA hospitalizations, potential omitted variable bias, correlational not causal conclusions, and heterogeneity in the new VHA-user category (both patients who never used VHA before and those who discontinued VHA care before our 2-year lookback timeframe). Limitations of the hotspot analysis include different sized submarkets presenting measurement issues in delineating the true geography of hospitalization and fewer comparisons for peripheral states with a smaller set of submarkets within the analytical distance band. Strengths include our use of a national hospital network with a diverse patient population, rather than a regional or single site hospital sample, examining catchment area-level rather than individual-level characteristics, and coupling regression-based and spatial statistic analyses to examine geographic clustering across catchment areas.

Pandemics can cripple the U.S. healthcare system by overwhelming hospitals. Thus, preemptive planning to identify hospitals that may be at higher risk for a surge in patients is crucial. Our analysis suggests providing additional resources to hospitals with more patients at high-risk for hospitalization during periods of high infection risk. Moreover, our findings also suggest that hospital systems can guard against future pandemic surges through proactive vaccination efforts. These efforts can leverage patient management tools, such as high-risk patient dashboards, to strategically target those most vulnerable to pandemic outbreaks for counseling, outreach, and vaccination. Furthermore, our spatial analysis emphasize the value of monitoring hospital level outcomes that can guide effective allocation of resources on a regional and national level.

Supplementary Material

Implications for Policy & Practice.

Identifying hospitals at higher risk for a surge in hospitals during pandemics can prevent hospitals from becoming overwhelmed. Healthcare systems can provide additional resources to hospitals that serve more patients at high risk for hospitalization during future COVID-19 surges to safeguard against sudden increases in hospitalization.

Engaging in proactive vaccination efforts is a valuable strategy that can prevent hospitals from becoming overwhelmed during pandemic surges. For COVID-19 vaccination, hospitals can leverage patient management tools to strategically target patients and communities that are most vulnerable to pandemic outbreaks.

Multiple adjacent hospitals may be affected by pandemic surges. Spatial analysis is a valuable tool to help guide effective resource allocation on a regional and national level.

Acknowledgement:

This study was supported using data from the VA COVID-19 Shared Data Resource. We would like to thank Anita Yuan, PhD for assistance in obtaining the dataset.

Financial Disclosure:

This work was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service through Grant #SDR-20-402 and Office of Health Equity and the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative through Grant #PEC-15-239 to the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Equity/Quality Enhancement Research Initiative National Partnered Evaluation Center. The views expressed within represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Human Participant Compliance Statement: The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved these analyses.

References

- 1.Ren SY, Wang WB, Gao RD, Zhou AM. Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) of SARS-CoV-2: Mutation, infectivity, transmission, and vaccine resistance. World J Clin Cases. Jan 7 2022;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meo SA, Meo AS, Al-Jassir FF, Klonoff DC. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 new variant: global prevalence and biological and clinical characteristics. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. Dec 2021;25(24):8012–8018. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202112_27652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewnard JA, Hong VX, Patel MM, Kahn R, Lipsitch M, Tartof SY. Clinical outcomes associated with Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant and BA.1/BA.1.1 or BA.2 subvariant infection in southern California. medRxiv. 2022:2022.01.11.22269045. doi: 10.1101/2022.01.11.22269045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward IL, Bermingham C, Ayoubkhani D, et al. Risk of covid-19 related deaths for SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) compared with delta (B.1.617.2): retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;378:e070695. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boudourakis L, Uppal A. Decreased COVID-19 Mortality—A Cause for Optimism. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2021;181(4):478–479. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen W, Chen C, Tang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19 : a meta-analysis. Ann Med. Dec 2022;54(1):516–523. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2034936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone W. ERs are overwhelmed as omicron continues to flood them with patients. Accessed September 8, 2022, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2022/01/13/1072902744/ers-are-overwhelmed-as-omicron-continues-to-flood-them-with-patients#:~:text=The%20omicron%20surge%20is%20jamming,School%20of%20Medicine%20in%20Maryland.

- 8.Aboulenein A. Overwhelmed by Omicron surge, U.S. hospitals delay surgeries. September 8, 2022 2022;

- 9.Li J, Huang DQ, Zou B, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. J Med Virol. Mar 2021;93(3):1449–1458. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green H, Fernandez R, MacPhail C. The social determinants of health and health outcomes among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Public Health Nurs. Nov 2021;38(6):942–952. doi: 10.1111/phn.12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira RHM, Braga CKV, Servo LM, et al. Geographic access to COVID-19 healthcare in Brazil using a balanced float catchment area approach. Soc Sci Med. Mar 2021;273:113773. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang JY, Michels A, Lyu F, et al. Rapidly measuring spatial accessibility of COVID-19 healthcare resources: a case study of Illinois, USA. Int J Health Geogr. Sep 14 2020;19(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12942-020-00229-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castro AD, Mayr FB, Talisa VB, et al. Variation in Clinical Treatment and Outcomes by Race Among US Veterans Hospitalized With COVID-19. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(10):e2238507-e2238507. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. Oct 2013;38(5):976–93. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rereddy SK, Jordan DR, Moore CE. Dying to be Screened: Exploring the Unequal Burden of Head and Neck Cancer in Health Provider Shortage Areas. J Cancer Educ. Sep 2015;30(3):490–6. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0755-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prevention CfDCa. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019): People who need to take extra precautions. Accessed July 1, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/index.html

- 17.Abbasi J. Vaccine Booster Dose Appears to Reduce Omicron Hospitalizations. JAMA. 2022;327(14):1323–1323. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.5156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leatherby L, Sun A. Covid Hospitalizations Plateau in Some Parts of the U.S., While a Crisis Remains in Others. The New York Times. January 21, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/01/21/us/covid-hospitalizations.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker F, Sawczuk H, Ganjkhanloo F, Ahmadi F, Ghobadi K. Optimal Resource and Demand Redistribution for Healthcare Systems Under Stress from COVID-19. ArXiv. 2020;abs/2011.03528 [Google Scholar]

- 20.New models can help hospitals stay ahead of COVID-19 surges. Johns Hopkins University HUB; October 27, 2020, 2020. https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/10/27/models-help-hospital-systems-allocate-resources-during-covid-19-surge/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.(CSO) VCSO. FY2020 Q4 Submarket. Veterans Health Administration, Chief Strategy Office, Geospatial Service Support Center. Accessed July 15, 2022, https://maps.vssc.med.va.gov/oiagisportal/home/item.html?id=13b999738a6240f0801fd7fee1e71dd9 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Updates to the VA COVID-19 Shared Data Resource and its Use for Research. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3834.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Variant Proportions. Accessed September 7, 2022, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

- 24.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. Fall 1974;9(3):208–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Fact Sheet: Veteran Community Care Eligiblity Accessed October 24, 2022, https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/pubfiles/factsheets/VA-FS_CC-Eligibility.pdf

- 26.Bishaw A, Benson C, Shrider E, Glassman B. Changes in Poverty Rates and Poverty Areas Over Time: 2005 to 2019. 2020. American Community Survey Briefs. December 2020. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/acs/acsbr20-008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA). What is Shortage Designation? Accessed October 24, 2022, https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation#hpsas

- 28.Wong MS, Luger TM, Katz ML, et al. Outcomes that Matter: High-Needs Patients’ and Primary Care Leaders’ Perspectives on an Intensive Primary Care Pilot. J Gen Intern Med. Nov 2021;36(11):3366–3372. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06869-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, et al. Predicting Risk of Hospitalization or Death Among Patients Receiving Primary Care in the Veterans Health Administration. Medical Care. 2013;51(4):368–373. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827da95a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ESRI. Data classification methods. Accessed September 15, 2022, https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/help/mapping/layer-properties/data-classification-methods.htm#:~:text=Natural%20breaks%20%28Jenks%29%20With%20natural%20breaks%20classification%20%28Jenks%29%2C,values%20together%20and%20maximizes%20the%20differences%20between%20classes

- 31.ESRI. How hot spot analysis: Getis-Ord Gi* (spatial statistics) works. Accessed September 15, 2022, https://webhelp.esri.com/arcgisdesktop/9.3/body.cfm?tocVisable=1&TopicName=How%20Hot%20Spot%20Analysis:%20Getis-Ord%20Gi*%20(Spatial%20Statistics)%20works

- 32.Chenchula S, Karunakaran P, Sharma S, Chavan M. Current evidence on efficacy of COVID-19 booster dose vaccination against the Omicron variant: A systematic review. J Med Virol. Jul 2022;94(7):2969–2976. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu J, Bartels CM, Rovin RA, Lamb LE, Kind AJH, Nerenz DR. Race, Ethnicity, Neighborhood Characteristics, and In-Hospital Coronavirus Disease-2019 Mortality. Med Care. Oct 1 2021;59(10):888–892. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000001624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samuels-Kalow ME, Dorner S, Cash RE, et al. Neighborhood Disadvantage Measures and COVID-19 Cases in Boston, 2020. Public Health Rep. May 2021;136(3):368–374. doi: 10.1177/00333549211002837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Age Group. Accessed February 15, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html

- 36.Hutchins HJ, Wolff B, Leeb R, et al. COVID-19 Mitigation Behaviors by Age Group - United States, April-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Oct 30 2020;69(43):1584–1590. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming MD, Shim JK, Yen I, et al. Managing the “hot spots”: Health care, policing, and the governance of poverty in the US. Am Ethnol. Nov 2021;48(4):474–488. doi: 10.1111/amet.13032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crane MA, Romley JA, Faden RR. Tracking COVID-19 Booster Doses in the US States. Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. Accessed November 25, 2022, https://bioethics.jhu.edu/news-events/news/tracking-covid-19-booster-doses-in-the-us-states/ [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foundation UH. America’s Health Rankings: 2021 Annual Report. 2021. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Outcomes/state

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.