Abstract

Introduction:

Children of people who smoke have a well-documented higher risk of smoking initiation. However, little is known about the persistence of the association between parental smoking and children’s own smoking as they age.

Methods:

This study uses data collected by the Panel Study of Income Dynamics collected between 1968 and 2017 and investigates the association between parental smoking and children’s own smoking through middle age and how it may be modified by adult children’s SES using regression models. The analysis was conducted between 2019 and 2021.

Results:

The results show an increased risk of smoking among adult children of parents who smoked. Their odds were elevated in young adulthood (OR: 1.55, CI: 1.11-2.14), established adulthood (OR: 1.53, CI: 1.08-2.15), and middle-age (OR: 1.63, CI: 1.04-2.55). Interaction analysis shows that this statistically significant relationship is limited to high school graduates only. Among people who smoked in the past or who currently smoke, children of people who smoked had longer average smoking duration. Interaction analysis shows that this risk is limited to high school graduates only. The adult children of people who smoked and have less than a high school education, some college and college graduates did not have a statistically significantly increased risk of smoking or longer smoking duration.

Conclusion:

The findings highlight the durability of early life influences, especially for people with low SES.

Keywords: smoking, life course, intergenerational, disparity, SES, USA

Introduction

Nearly half of US adults smoked in the middle of the twentieth century.1 In 2020, the estimated smoking rate was about 13 percent.2 The precipitous decline of smoking in the United States figures among the greatest American public health achievements. Yet, smoking remains among the largest preventable causes of death in the United States, killing nearly half a million Americans yearly.3 People who smoke lose, on average, ten years of life and enjoy fewer disability-free years.4 While the health consequences of smoking generally play out in later life, most people who smoke start in childhood or adolescence.5 A major risk factor for smoking initiation is growing up in a family that includes a person who smokes.5 A comprehensive meta-analysis of 58 studies on smoking transmission within families shows that the odds of a child’s smoking initiation are 1.7 times greater in families where at least one parent smokes.6

Although the relationship between having a parent who smokes and child initiation has been well-established, little is known about the persistence of the association across the life course and how it may be modified by the child’s experiences in later life. This is a crucial omission because quantifying the durability and modifiability of the early life association is essential to understanding the relationship between childhood risk factors and later-life health outcomes. This study examines the association’s persistence over the life course and how it is modified by attained socioeconomic status (SES).

Multiple pathways contribute to the association between parental smoking and child smoking initiation. Part of the relationship is thought to be physiological. Children of mothers who smoke during pregnancy may become more susceptible to nicotine and initiate smoking at younger ages.7,8 When they initiate, children exposed to nicotine in-utero also report a greater degree of nicotine dependency.9 Genetic inheritance contributes to family correlation in smoking as well.10 Children who share their parents’ smoking-relevant genotype and start smoking before age 16 are more likely to smoke for life than children who do not. 11 A parent who smokes also may expose a child to secondhand smoke, which might establish a taste for tobacco and nicotine.12 Children as young as four imitate their parents’ smoking in play 13,14 and children of people who smoke have more opportunities to observe the “right way” to smoke. Cigarettes are more likely to be readily available in a home with people who smoke, and a child faces fewer practical obstacles to initiation in households with an adult who smokes.15 However, the extent to which the strength of the association between parents and child smoking wanes in adulthood remains an open question. Thus, the first goal of this study is to evaluate the associations between parental smoking and children’s smoking as individuals age through adulthood.

As the overall prevalence of smoking in the US population has declined, smoking has become increasingly concentrated among people with lower SES. In 2019, 35 percent of adults with a general educational development (GED) diploma smoked, while only seven percent of college-educated Americans did. 2 Because smoking is closely correlated with SES, children’s own SES attainment in adulthood could be an important modifier of the link between the parents’ and their own smoking. A study of children born in the United Kingdom reports that a large part of smoking initiation among disadvantaged children can be explained by their greater exposure to adults who smoke. 16 Thus, the study’s second goal is to evaluate how SES attainment in adulthood modifies the associations between parental smoking and adult children’s smoking throughout their lives.

Using the prospectively collected Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), 17 which has followed multiple generations of respondents since the middle of the twentieth century, this paper answers the following research questions: 1) Do adult children of people who smoke have elevated odds of smoking across different life stages? 2) Do adult children of people who smoke have longer smoking trajectories across the life course than children of people who do not smoke? 3) Does socioeconomic attainment of adult children of people who smoke modify their risk of smoking across different life stages and duration of smoking trajectories? The results are discussed in the context of the extant literature.

Methods

Study Sample

The PSID is an ongoing longitudinal survey that began tracking the lives of a nationally representative sample of 4,800 American families in 1968, originally annually and starting in 1997 biennially. The PSID has, by design, attempted to follow all members and descendants of the original sample, even as they separated from the original household due to marital dissolution or adult children forming new households. Its unique structure makes the PSID the most frequently used dataset for intergenerational analysis in the United States.18,19 The PSID has recorded smoking and smoking histories at several time points, first in 1968, then 1986, and then again in 1999. Following that, the survey started asking about smoking regularly. The PSID’s design offers an ideal opportunity to examine the connections between parents’ smoking and adult children’s smoking over the life course. The cohort of “adult children” used in this study was born between 1958 and 1968, consisted of 4,763 children at the 1968 baseline, and was observed again in 1986, 1999, and 2017.

Measures

Parents’ smoking was first measured in 1968. The respondent reporting data for their family was asked: “Do any of you smoke?” Fifty-five percent of the sample answered in the affirmative.

Adult child smoking status and smoking duration was measured in 1986 (young adulthood; 18 to 28 years), 1999 (established adulthood; 31 to 41 years), and 2017 (middle age; 49 to 59 years). The PSID linkage indicator identified whether the direct descent of the 1968 family was a primary respondent or designated “wife” in 1986, 1999, and 2017 interviews. Based on this information, current adult child smoking status (first outcome variable) was assigned at each wave from either a response to a question about the respondent’s own smoking or about their partner’s. Respondents who self-identified as currently smoking or ever smoking were asked about the age when they first started smoking regularly and, those who quit, how old they were when they did so (second outcome variable). For people who used to smoke, smoking duration was calculated as the difference between the age of cessation and the age when regular smoking started. For people who smoke, smoking duration was calculated as the difference between the current age in the last wave (2017) and when regular smoking started.

The PSID includes a variety of indicators of SES. This study uses educational attainment as a measure of SES at each time point. Education is relatively constant over the life course and encapsulates multiple dimensions of social position. The survey asked: How many grades of school did you finish?” The number of years reported at each time point was used to assign each person to the less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate or more. In addition, household income was measured by summing total taxable family income with any additional transfers other than food stamps. Each family was assigned an income quartile based on their position in the US income distribution for that specific year.

The analysis includes additional control variables. These are gender (male or not), continuous age, and marital status (married/partnered, single, widowed/divorced/separated). The PSID’s approach to measuring race has changed substantially over time. To maintain consistency across time, respondents are labeled as White or Black, and members of other racial groups or people who identify as multiracial are labeled as “other.”

Statistical Analysis

The adult child cohort was born between 1958 and 1968 and observed in 1986, 1999, and 2017. In total, there were 4,763 children identified as potential sample members. By 1986, the first point of adult observation, 1,550 of the 1968 children, then young adults, were still participating in the study and had established their own households. They are the first analytic sample. By 1999, 1,507 members of the adult-child cohort continued to participate in PSID. Sixty-eight did not provide data on one or more variables used in the analysis. The second analytic sample, for 1999, was 1,439. During the final year of observation, 2017, 1,153 members of the original cohort were still participating. Seventeen did not provide a response to one or more questions used. The third analytic sample was 1,136. Because the PSID has been frequently used for studies of intergenerational relationships, a substantial body of literature has evaluated the extent to which attrition may bias analysis. The available evidence demonstrates that attrition is not a major concern for the analytic design when the analysis is weighted using the provided survey weights.20,21

The associations between parental smoking in childhood and adult child’s s own smoking in young adulthood, established adulthood, and middle age were estimated using logistic regression models, gradually adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. Their results are presented as odds ratios in Table 1. The associations between smoking duration and parental smoking were assessed using ordinary least squares regression models presented in Table 2. Only people who ever smoked were included in the smoking duration models. Modification by attained SES was evaluated in the fully adjusted models presented in Figures 1 and 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the cohort are in Appendix. Analyses were performed in Stata 17, and PSID-distributed survey weights22 were applied to all models. The study is not classified as human subject research and exempt from IRB oversight.

Table 1.

Logistic regression table predicting adult child smoking in 1986, 1999, ad 2017 cohorts.

| Predictor variables | 1986 | 1986 | 1986 | 1986 | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | 2017 | 2017 | 2017 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Parents smoked in 1968 | 1.82*** [1.33, 2.50] | 1.80*** [1.31, 2.48] | 1.53* [1.11, 2.11] | 1.55** [1.12, 2.14] | 1.84*** [1.34, 2.53] | 1.86*** [1.35, 2.57] | 1.53* [1.09, 2.16] | 1.53* [1.08, 2.15] | 1.98** [1.32, 2.98] | 1.94** [1.28, 2.93] | 1.63* [1.05, 2.51] | 1.63* [1.04, 2.55] |

| Predictor variables | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.04 [0.78, 1.39] | 1.03 [0.76, 1.39] | 1.02 [0.75, 1.38] | 0.90 [0.66, 1.22] | 0.90 [0.65, 1.24] | 0.89 [0.64, 1.23] | 1.13 [0.76, 1.67] | 1.14 [0.75, 1.73] | 1.12 [0.73, 1.72] | |||

| Age | 1.00 [0.95, 1.06] | 1.07* [1.02, 1.13] | 1.09** [1.03, 1.15] | 1.01 [0.96, 1.06] | 1.01 [0.96, 1.06] | 1.01 [0.96, 1.06] | 1.02 [0.96, 1.10] | 1.01 [0.94, 1.09] | 1.00 [0.93, 1.08] | |||

| Race (White reference) | ||||||||||||

| Black | 1.06 [0.72, 1.56] | 0.77 [0.52, 1.14] | 0.72 [0.48, 1.07] | 0.93 [0.62, 1.39] | 0.65 [0.42, 1.00] | 0.60* [0.37, 0.95] | 1.30 [0.81, 2.07] | 0.91 [0.54, 1.55] | 0.83 [0.49, 1.38] | |||

| Other | 1.12 [0.44, 2.83] | 0.83 [0.29, 2.43] | 0.86 [0.28, 2.65] | 0.92 [0.46, 1.83] | 0.75 [0.37, 1.49] | 0.76 [0.39, 1.49] | 0.55 [0.19, 1.63] | 0.44 [0.14, 1.35] | 0.39 [0.13, 1.21] | |||

| Marital Status (Partnered reference) | ||||||||||||

| Single | 1.24 [0.91, 1.68] | 1.63** [1.18, 2.25] | 1.50* [1.06, 2.11] | 1.18 [0.77, 1.80] | 1.25[0.81, 1.93] | 1.00 [0.61, 1.64] | 1.41 [0.76, 2.60] | 1.35 [0.67, 2.72] | 0.73 [0.36, 1.49] | |||

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 2.30*** [1.47, 3.59] | 1.98** [1.22, 3.19] | 1.72* [1.03, 2.87] | 2.51*** [1.67, 3.76] | 2.10** [1.35, 3.27] | 1.69* [1.04, 2.74] | 2.09*** [1.37, 3.21] | 1.78** [1.15, 2.76] | 1.08 [0.66, 1.77] | |||

| Education (Less than HS reference) | ||||||||||||

| HS Graduate | 0.38*** [0.26, 0.55] | 0.40*** [0.27, 0.58] | 0.46** [0.28, 0.76] | 0.49** [0.29, 0.81] | 0.42* [0.21, 0.83] | 0.57 [0.29, 1.13] | ||||||

| Some College | 0.19*** [0.12, 0.30] | 0.20*** [0.13, 0.32] | 0.20*** [0.11, 0.36] | 0.23*** [0.13, 0.41] | 0.23*** [0.11, 0.49] | 0.36** [0.17, 0.78] | ||||||

| College+ | 0.10*** [0.06, 0.19] | 0.11*** [0.06, 0.20] | 0.09*** [0.05, 0.18] | 0.12*** [0.06, 0.22] | 0.07*** [0.03, 0.17] | 0.13*** [0.05, 0.33] | ||||||

| Income Quartile | ||||||||||||

| 2nd | 0.69* [0.48, 1.00] | 0.69 [0.43, 1.11] | 0.53* [0.30, 0.92] | |||||||||

| 3rd | 0.66 [0.42, 1.02] | 0.62 [0.36, 1.07] | 0.38** [0.20, 0.73] | |||||||||

| 4th | 0.80 [0.46, 1.42] | 0.51 * [0.28, 0.92] | 0.23*** [0.12, 0.47] | |||||||||

| N | 1,550 | 1,550 | 1,550 | 1,550 | 1,439 | 1,439 | 1,439 | 1,439 | 1,136 | 1,136 | 1,136 | 1,136 |

Note: Models gradually adjust for sociodemographic characteristics using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics cohort born between 1958 and 1968. Covariates held at means; confidence intervals in parentheses. Coefficients have been transformed into odds ratios. 95% confidence interval in parentheses. Survey weights applied. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

<0.05

<0.01

<0.001.

Table 2.

Ordinary least squares regression models predicting smoking duration in middle age.

| Predictor variables | Smoking duration in years, Model 1 | Smoking duration in years, Model 2 | Smoking duration in years, Model 3 | Smoking duration in years, Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents smoked in 1968 | 4.32** [1.16, 7.47] | 3.83* [0.67, 6.99] | 2.97 [−0.23, 6.17] | 3.06 [−0.13, 6.25] |

| Male | −0.72 [−3.74, 2.29] | −0.95 [−3.88, 1.97] | −1.22 [−4.10, 1.67] | |

| Agea | 2.55** [1.00, 4.10] | 2.54** [1.01, 4.08] | 2.62** [1.10, 4.13] | |

| Race (White reference) | ||||

| Black | 0.80 [−2.46, 4.05] | −0.38 [−3.82, 3.07] | −0.77 [−4.21, 2.67] | |

| Other | 1.60 [−5.85, 9.04] | 1.03 [−5.75, 7.81] | 0.43[−6.35, 7.20] | |

| Marital Status (Partnered reference) | ||||

| Single | 0.76 [−3.46, 4.99] | 0.98 [−3.36, 5.32] | −1.31 [−5.84, 3.22] | |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 2.89 [−0.49, 6.27] | 2.46 [−0.86, 5.78] | 0.52 [−3.01, 4.06] | |

| Education (Less than high school reference) | ||||

| High School Graduate | −1.87 [ −7.45, 3.71] | −0.71 [−6.45, 5.03] | ||

| Some College | −4.47 [−10.36, 1.42] | −2.97 [−9.19, 3.26] | ||

| College+ | −8.63** [−15.21, −2.04] | −6.09 [−12.95, 0.78] | ||

| Income Quartile | ||||

| 2nd | −1.35 [−5.56, 2.87] | |||

| 3rd | −2.95 [−7.57, 1.66] | |||

| 4th | −5.65* [−10.22, −1.08] | |||

| Constant | 23.84*** [21.25, 26.42] | 23.11*** [19.90, 26.33] | 27.79*** [21.56, 34.02] | 29.61*** [23.30, 35.92] |

| N | 505 | 505 | 505 | 505 |

Note: Models with gradual adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics cohort born between 1958 and 1968 interviewed in middle age. 95% confidence interval in parentheses. Survey weights applied. A Z-score standardized for interpretability. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

<0.05

<0.01

<0.001.

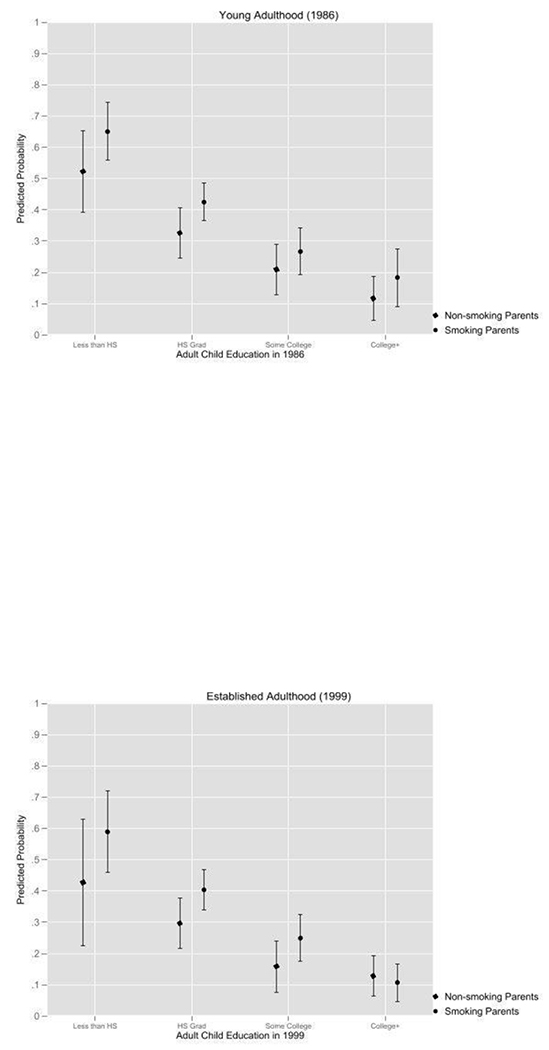

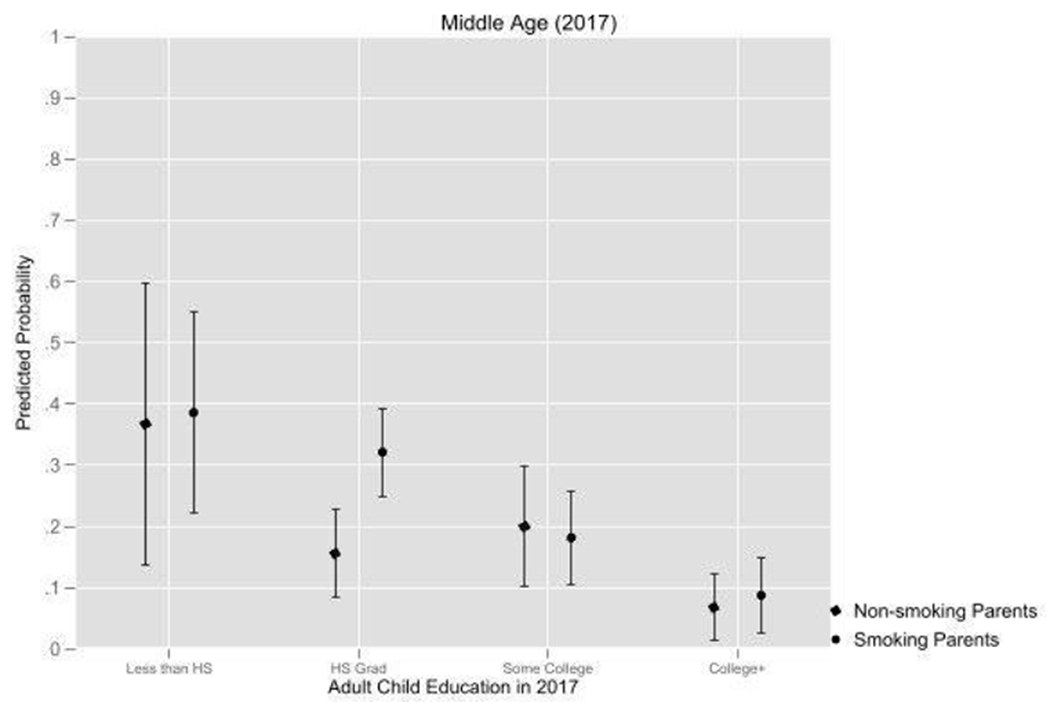

Figure 1.

A-C. Predicted probability of smoking by adult child’s educational attainment and parents’ smoking over the life course in the PSID adult child cohort. Survey weights applied and models fully adjusted.

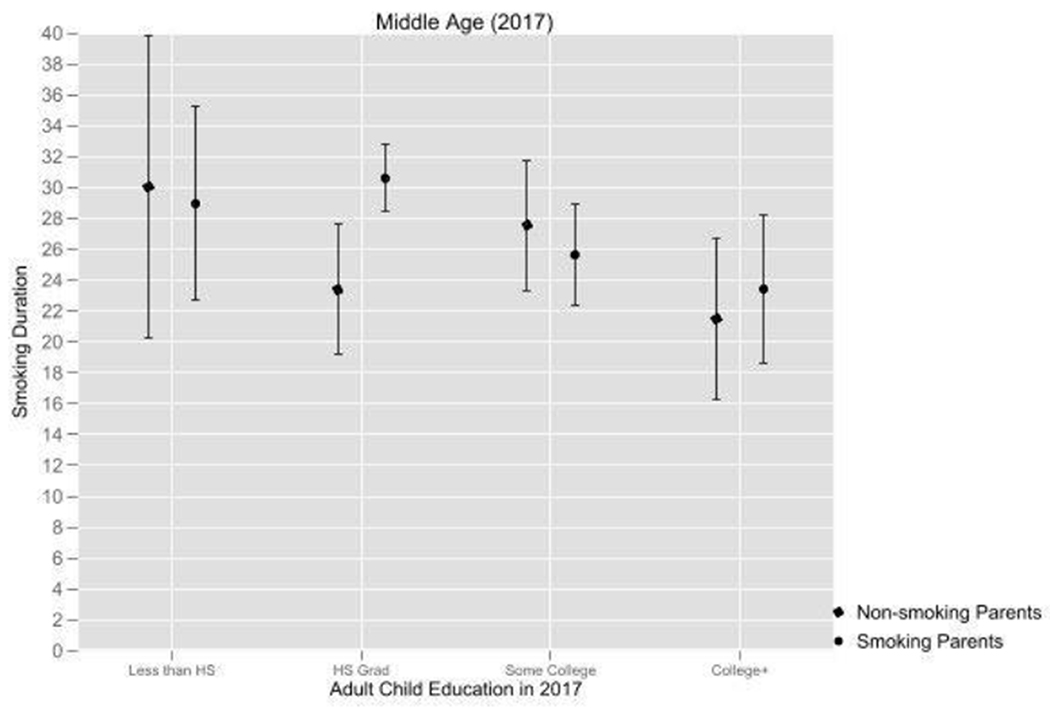

Figure 2.

The predicted number of years of smoking by adult child’s educational attainment and parents’ smoking over the life course in the PSID adult child cohort. Survey weights applied and models fully adjusted.

Results

Table 1 displays result from logistic regression models predicting adult child’s smoking across the life course. Coefficients have been transformed into odds ratios. Without adjustment, in young adulthood, the respondents whose parent smoked in childhood had a statistically significant 1.82 times greater odds of smoking. The probability was not substantially diminished after accounting for their other sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, race, and marital status. Higher age, being single or formerly partnered (as opposed to currently partnered) was associated with greater odds of smoking. In contrast, being Black, having higher education attainment and income was associated with lower odds of smoking. After adjusting for education and income, respondents with a smoking parent had 1.55 times greater odds of smoking and the difference was statistically significant.

The second panel shows associations in established adulthood. Without adjustment, adult children of people who smoked had statistically significant 1.84 times greater odds of smoking than children of people who did not smoke. The association persisted in magnitude and statistical significance after adjusting for demographic characteristics. Being formerly partnered (as opposed to currently partnered) was associated with higher odds of smoking. Income greater than second quartile (as opposed to first quartile) and higher education were associated with lower odds of smoking. With adjustment for education and education and income, children of people who smoked remained more likely to smoke in established adulthood. Their odds were 1.53 times greater than for children of people who do not smoke.

The panel on the right-hand side displays the associations between parental smoking and adult child smoking in middle age. Without adjustment, having had a parent who smoked was associated with nearly twice the odds of smoking in middle age. Having some college or college or more was associated with lower odds of smoking, as was higher income. Adjusting for education and education and income, adult children of people who smoke had a statistically significant seven percentage points greater probability of smoking in midlife. In the final model in this series with the full set of controls, children of people who smoke still had 1.63 times greater odds of smoking in middle age than children of people who do not smoke.

Table 2 shows results from ordinary least squares regression models predicting smoking duration among ever smokers in middle age. The first model, without any adjustment, shows that people whose parents smoked had, on average, a statistically significant 4.3 years longer total smoking duration. The mean smoking duration for people with non-smoking parents was 23.8 years. In the second model, after demographic adjustment, the middle-age children of parents who smoked continued to have statistically significantly longer average smoking duration. The next model adds a control for educational attainment. After adjustment, having had a parent who smoked was associated with longer smoking duration by about three years, but the association was only marginally statistically significant. The final model adjusts for the income quartile in addition to education. Parents’ smoking status remained associated with longer smoking duration, by about 3.1 years, but the association was only marginally statistically significant.

Figure 1 shows how adult children’s education modifies the associations between parental smoking in childhood and one’s own smoking in each of the three life course stages. The results show that, at all three stages, only high school graduates whose parents smoked had an increased probability of smoking. The interactions overall were not statistically significant. The predicted probabilities and p-values are displayed below.

Figure 2 shows results from a model that predicts adult children’s smoking duration by parents’ smoking modified by the child’s educational attainment. As in Figure 1, the results show that adult children of smokers who had high school education alone smoked for longer than those whose parents did not smoke. There were no statistically significant differences for children of people who smoke and people who do not smoke in other educational categories. The interaction overall was marginally statistically significant.

Discussion

Prior research has shown that having parents who smoke cigarettes is associated with a greater risk of one’s own initiation6 and argued that exposure to smoking adults could help explain some of the persistent socioeconomic disparities found in smoking.16 This paper contributes to the literature on parental smoking as a risk factor by using panel data collected over sixty years from parents and adult children and observing the association between parental and child smoking over the life course. The probability of smoking remains elevated for children of people who smoke throughout life. Among those who smoked in adulthood, children of smokers persisted in smoking longer on average compared to the children of parents who did not smoke. The increased smoking probability and longer duration were statistically significant among high school graduates but in no other group. In young adulthood and established adulthood, the probability of smoking also appeared larger for children of people who smoke and completed less than high school but this difference was not statistically significant.

Taken together, the results of this study present several important implications for the understanding of the familial persistence of smoking and SES. Building on prior research with shorter follow-up,23–26 this study shows that the associations between parental smoking in childhood and one’s own smoking persists into middle age. The magnitude of the odds ratios in fully adjusted models predicting adult child smoking by parents’ smoking varied little across the life course. Because of the stability and persistence of the associations, the findings align with the sensitive period model.27 It is also possible that the stable increased probability of smoking is reflected in the increased susceptibility to nicotine passed on from parents to children or the epigenetic interaction between the genetic susceptibility and exposure.28 The design of this study cannot rule out this explanation, and the increased probability may be a result of the combination of genetic and social factors.

The SES-specific results could be interpreted as posing a challenge to both the critical period and genetic sensitivity explanations because they would anticipate increased probability and duration regardless of later educational attainment. Instead, the results suggest that parental smoking status matters conditionally on children’s own adult experiences. The diminished disadvantage of the highly educated children of people who smoke can likely be explained by the positive influences they benefit from on account of their high SES. For example, research shows that anti-smoking sentiment and support for tobacco control laws are stronger in communities with higher average educational attainment. More highly educated people who smoke are also more likely to succeed when they make a quit attempt. Their greater success in quitting has been ascribed to their better access to cessation tools via health insurance, lower exposure to daily stress, and fewer social connections with other people who smoke. The combined effect of these advantages could also explain why highly educated people whose parents smoked were less vulnerable to the exposure and did not start smoking themselves. The results also show that people with less than a high school degree did not have a statistically significantly elevated smoking risk even when their parents smoked. This finding runs contrary to the expectation that all SES groups experience higher risk when their parents smoked. A possible explanation for this finding might be that the pre-existing overall very high risk of smoking of people with less than a high school degree was not statistically significantly exacerbated by having parents who smoked.

Limitations

Despite the important findings this study presents, there are several limitations that need to be considered. First, smoking onset is retrospectively reported. The PSID only collected data from people who have already formed their own households, and initiation occurs chiefly in adolescence. Moreover, there was a gap between the first (1968) and second (1986) smoking data collection report, during which adult children may have started and stopped smoking. Smoking duration was measured based on smoking history and duration reported at the last wave. This means that the number of years may have been overestimated for people who stopped smoking for several years between young adulthood and midlife, but became smokers again by the time of their last interview. Moreover, because the PSID is a household survey, some smoking outcomes have been reported by proxies. Past research shows that smoking reported by adult proxies is generally accurate29 but may be less so when information such as year of initiation is also proxy-reported.30

This study only measured parental smoking at one point in childhood, between 0 and 10, in 1968. For some children, parental smoking was of short duration. In sensitivity analysis using retrospective parental data from the 1986 reports to identify parents who smoked a) the entire duration of the adult-child’s childhood, defined as 0-18, and b) most of the childhood, defined as at least nine years, c) less than half of their childhood, defined as less than nine years, the association between parental smoking and own smoking over the life course was stronger for adult children whose parents smoked their entire childhood.

Finally, most people quit smoking gradually and make multiple quit attempts before they succeed.31,32 While a person may report being quit at one survey wave, the quit process could unfold over multiple years. To mitigate the risk of classifying as non-smokers who are in the middle of the cessation process, which might potentially not succeed, I conducted a sensitivity analysis only classifying as non-smokers the former smokers who reported quitting at least a year ago. The results were substantively unchanged.

Conclusion

Smoking remains among the leading causes of preventable death in the United States.1 Prior research has shown that children of people who smoke have an especially high risk of smoking initiation.6 However, prior research has paid little attention to how exposure to this early life risk factor may shape smoking behavior over the life course. This study investigated the associations between parental and adult child smoking and the extent to which adult child’s SES attainment modified this relationship. The results show that children of people who smoke had a lifelong elevated risk of smoking, highlighting the intergenerational harms of smoking. Interaction analysis shows that the risk was statistically significantly elevated for people who attained a high school degree only. Taken together, the results highlight some potential of educational attainment to mitigate early life disadvantages.

Supplementary Material

Funding sources:

The author gratefully acknowledges use of the services and facilities of the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan, funded by NICHD Center Grant P2CHD041028. The work was supported by a fellowship from the Weinberg Research Prize.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Individual Financial disclosures: No financial disclosures were reported by the author of this paper.

CRediT author statement:

Lucie Kalousova: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing.

Data availability statement:

Data is available from download from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. https://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/

References

- 1.USHHS. 2014 Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. (http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/index.htm).

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Protection. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2010–2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021.

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Protection. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005-2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014. (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6302a2.htm?s_cid=mm6302a2_w). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-Century Hazards of Smoking and Benefits of Cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013;368(4):341–350. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.USHHS. Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonardi-Bee J, Jere ML, Britton J. Exposure to Parental and Sibling Smoking and the Risk of Smoking Uptake in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thorax 2011;66(10):847–855. DOI: 10.1136/thx.2010.153379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buka SL, Shenassa ED, Niaura R. Elevated risk of tobacco dependence among offspring of mothers who smoked during pregnancy: a 30-year prospective study. The American journal of psychiatry 2003;160(11):1978–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weden MM, Miles JNV. Intergenerational Relationships Between the Smoking Patterns of a Population-Representative Sample of US Mothers and the Smoking Trajectories of Their Children. Am J Public Health 2012;102(4):723–731. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Callaghan FV, Al Mamun A, O’Callaghan M, et al. Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy Predicts Nicotine Disorder (Dependence or Withdrawal) in Young Adults – A Birth Cohort Study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2009;33(4):371–7. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim Y-K, Kim Y-K. Handbook of Behavior Genetics: Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnoll RA, Johnson TA, Lerman C. Genetics and Smoking Behavior. Current Psychiatry Reports 2007;9(5):349–357. DOI: 10.1007/s11920-007-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang MP, Ho SY, Lam TH. Parental Smoking, Exposure to Secondhand Smoke at Home, and Smoking Initiation among Young Children. Nicotine and Tobacco Research 2011;13(9):827–832. DOI: 10.1093/ntr/ntr083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Leeuw RNH, Engels RCME, Scholte RHJ. Parental Smoking and Pretend Smoking in Young Children. Tob Control 2010;19(3):201–205. DOI: 10.1136/tc.2009.033407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowa-Dewar N, Lumsdaine C, Amos A. Protecting Children From Smoke Exposure in Disadvantaged Homes. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17(4):496–501. DOI: 10.1093/ntr/ntu217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conrad KM, Flay BR, Hill D. Why Children Start Smoking Cigarettes: Predictors of Onset. Br J Addict 1992;87(12):1711–24. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor-Robinson DC, Wickham S, Campbell M, Robinson J, Pearce A, Barr B. Are Social Inequalities in Early Childhood Smoking Initiation Explained by Exposure to Adult Smoking? Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. PLoS One 2017;12(6):e0178633. (In eng). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGonagle KA, Schoeni RF, Sastry N, Freedman VA. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics: Overview, Recent Innovations, and Potential for Life Course Research. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 2012;3(2). DOI: 10.14301/llcs.v3i2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill MS The Panel Study of Income Dynamics: A User’s Guide. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharkey P The Intergenerational Transmission of Context. American Journal of Sociology 2008;113(4):931–969. DOI: 10.1086/522804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzgerald J, Gottschalk P, Moffitt R. An Analysis of the Impact of Sample Attrition on the Second Generation of Respondents in the Michigan Panel Study of Income Dynamics. The Journal of Human Resources 1998;33(2):300–344. DOI: 10.2307/146434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzgerald JM Attrition in Models of Intergenerational Links Using the PSID with Extensions to Health and to Sibling Models. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 2011;11(3). DOI: doi: 10.2202/1935-1682.2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heeringa SG, Berglund PA, McGonagle K, Schoeni R. Panel Study of Income Dynamics PSID cross-sectional individual weights, 1997-2011. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menezes AM, Gonçalves H, Anselmi L, Hallal PC, Araújo CL. Smoking in early adolescence: evidence from the 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) Birth Cohort Study. J Adolesc Health 2006;39(5):669–677. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauman KE, Carver K, Gleiter K. Trends in parent and friend influence during adolescence: the case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Addict Behav 2001;26(3):349–361. DOI: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Callaghan FV, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Williams GM, Bor W, Alati R. Prediction of adolescent smoking from family and social risk factors at 5 years, and maternal smoking in pregnancy and at 5 and 14 years. Addiction 2006;101(2):282–290. DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster SE, Jones DJ, Olson AL, et al. Family socialization of adolescent’s self-reported cigarette use: the role of parents’ history of regular smoking and parenting style. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32(4):481–493. DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/js1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology: Conceptual Models, Empirical Challenges and Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31(2):285–293. DOI: 10.1093/ije/312285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson KW, Oreland L, Kronstrand R, Leppert J. Smoking as a product of gene–environment interaction. Ups J Med Sci 2009;114(2):100–107. DOI: 10.1080/03009730902833406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Cavin SW, et al. Estimates of population smoking prevalence: self-vs proxy reports of smoking status. Am J Public Health 1994;84(10):1576–1579. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.84.10.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soulakova JN, Bright BC, Crockett LJ. On Consistency of Self- and Proxy-reported Regular Smoking Initiation Age. J Subst Abus Alcohol 2013;1(1):1001. (In eng). DOI: 10.1006/pmed.19951039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59(2):295–304. DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hennrikus DJ, Jeffery RW, Lando HA. The Smoking Cessation Process: Longitudinal Observations in a Working Population. Prev Med 1995;24(3):235–244. DOI: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from download from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. https://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/