Abstract

The Ectodysplasin A2 receptor (XEDAR), is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor subfamily and is a mediator of the Ectodysplasin (EDA) pathway. EDA signaling plays evolutionarily conserved roles in the development of the ectodermal appendage organ class that includes hair, eccrine sweat glands, and mammary glands. Loss of function mutations in Eda, which encodes the two major ligand isoforms, EDA-A1 and EDA-A2, result in X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia characterized by defects in two or more types of ectodermal appendages. EDA-A1 and EDA-A2 signal through the receptors EDAR and XEDAR, respectively. While the contributions of the EDA-A1/EDAR signaling pathway to EDA-dependent ectodermal appendage phenotypes have been extensively characterized, the significance of the EDA-A2/XEDAR branch of the pathway has remained obscure. Herein, we report the phenotypic consequences of disrupting the EDA-A2/XEDAR pathway on mammary gland differentiation and growth. Using a mouse Xedar knock-out model, we show that Xedar has a specific and temporally restricted role in promoting late pubertal growth and branching of the mammary epithelium that can be influenced by genetic background. Our findings implicate Xedar in ectodermal appendage development and suggest that the EDA-A2/XEDAR signaling axis contributes to the etiology of EDA-dependent mammary phenotypes.

Keywords: mammary gland, Eda2r, Xedar, tabby, Ectodysplasin, ectodermal appendage, Eda

INTRODUCTION

The Ectodysplasin signaling pathway has long been recognized for its pivotal role in the development, pattering and differentiation of mammalian ectodermal appendages including hair follicles, eccrine sweat glands, teeth, and mammary glands (Biggs and Mikkola 2014; Cui et al. 2014; Cui et al. 2009; Headon et al. 2001; Headon and Overbeek 1999; Lindfors et al. 2013; Tucker et al. 2000; Voutilainen et al. 2015; Voutilainen et al. 2012; Wahlbuhl et al. 2018; Wahlbuhl-Becker et al. 2017). Alternative splicing of transcripts encoded by the anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia gene (Eda) produces two main protein isoforms, EDA-A1 and EDA-A2, which belong to the tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily (Yan et al. 2000). An insertion of two amino acids differentiates the EDA-A1 isoform from EDA-A2 and is necessary and sufficient to confer exclusive binding to the receptors EDAR and XEDAR, respectively (Yan et al. 2000). EDAR and XEDAR are type III transmembrane receptors whose respective binding to EDA-A1 and EDA-A2 oligomers has been shown to activate downstream NFkB signaling, and in some contexts JNK signaling (Kumar et al. 2001; Sinha and Chaudhary 2004; Yan et al. 2000).

In humans, loss of function mutations in Eda are causal to the majority of cases of the most common form of ectodermal dysplasia, X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED #MIM 305100) (Cluzeau et al. 2011). Affected individuals present with clinical features in two or more ectodermal appendages including reduced numbers or total loss of eccrine glands, sparse hair, missing teeth, and mammary phenotypes including impaired breast and nipple development, and lactation difficulties in females (Cluzeau et al. 2011; Wahlbuhl-Becker et al. 2017). The role of Eda in ectodermal appendage development is evolutionarily conserved. The two widely studied Tabby loss of function alleles of the murine Eda locus, EdaTa−6J and EdaTa, which harbor a frameshift-inducing base pair deletion and a deletion in exon 1, respectively, cause highly homologous ectodermal appendage defects to those of human XLHED patients (Biggs and Mikkola 2014; Cui and Schlessinger 2006; Mikkola and Thesleff 2003; Sofaer and MacLean 1970; Srivastava et al. 1997; Wahlbuhl et al. 2018). These phenotypes, particularly in hair follicles and eccrine glands, are thought to result from disruption of the EDA-A1/EDAR signaling axis, since loss of function mutations in Edar largely phenocopy the defects observed in EdaTa−6J and EdaTa mutants, and exogenous treatment with recombinant EDA-A1 protein rescues or improves many of the XLHED hair and eccrine phenotypes in mice, humans, and dogs (Casal et al. 2007; Gaide and Schneider 2003; Margolis et al. 2019; Mustonen et al. 2004; Mustonen et al. 2003; Schneider et al. 2018; Srivastava et al. 2001). In contrast, the extent to which the EDA-A2/XEDAR signaling axis contributes to Eda-dependent ectodermal appendage phenotypes is unclear.

In humans, XLHED-inducing mutations generally result in dysfunction or loss of both EDA-A1 and EDA-A2 isoforms, as do the EdaTa−6J and EdaTa mouse mutations (Cluzeau et al. 2011; Wohlfart et al. 2016). Accordingly, deciphering the individual roles of the two ligand isoforms in ectodermal appendage biology relies on characterization of the effects of the receptors that mediate signaling by EDA-A1 and EDA-A2, respectively, namely EDAR and XEDAR. Unlike the dramatic ectodermal appendage phenotypes resulting from Edar loss-of function mutations, however, Xedar knock-out (XedarKO) mice are reported to have normal hair, eccrine gland, and tooth development (Newton et al. 2004). Moreover, ectopic expression of an EDA-A2 transgene or recombinant Fc-EDA-A2 does not rescue hair, eccrine or tooth phenotypes in Eda mutant mice, underscoring the importance of the EDA-A1/EDAR pathway in the development of this subset of ectodermal appendages (Casal et al. 2007; Gaide and Schneider 2003; Margolis et al. 2019).

Analyses of the mammary glands of XedarKO mice have not been reported. The mammary gland and its supporting structures are of clinical importance in humans since the majority of female XLHED carriers report lactation difficulties (Clarke et al. 1987). This is notable since treatment with or ectopic expression of EDA-A1 improves but does not fully rescue the mammary phenotypes of mouse Eda mutants, including the reduction of mammary gland branching and lactation deficits (Mustonen et al. 2003; Srivastava et al. 2001; Wahlbuhl et al. 2018). In light of these observations and motivated by the clinical need to fully understand the etiology of human XLHED mammary phenotypes, we investigated the phenotypic consequences of disrupting the EDA-A2/XEDAR signaling axis on mammary gland morphogenesis using a constitutive XedarKO mouse model.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The loss of Xedar disrupts Eda-dependent epithelial mammary gland phenotypes

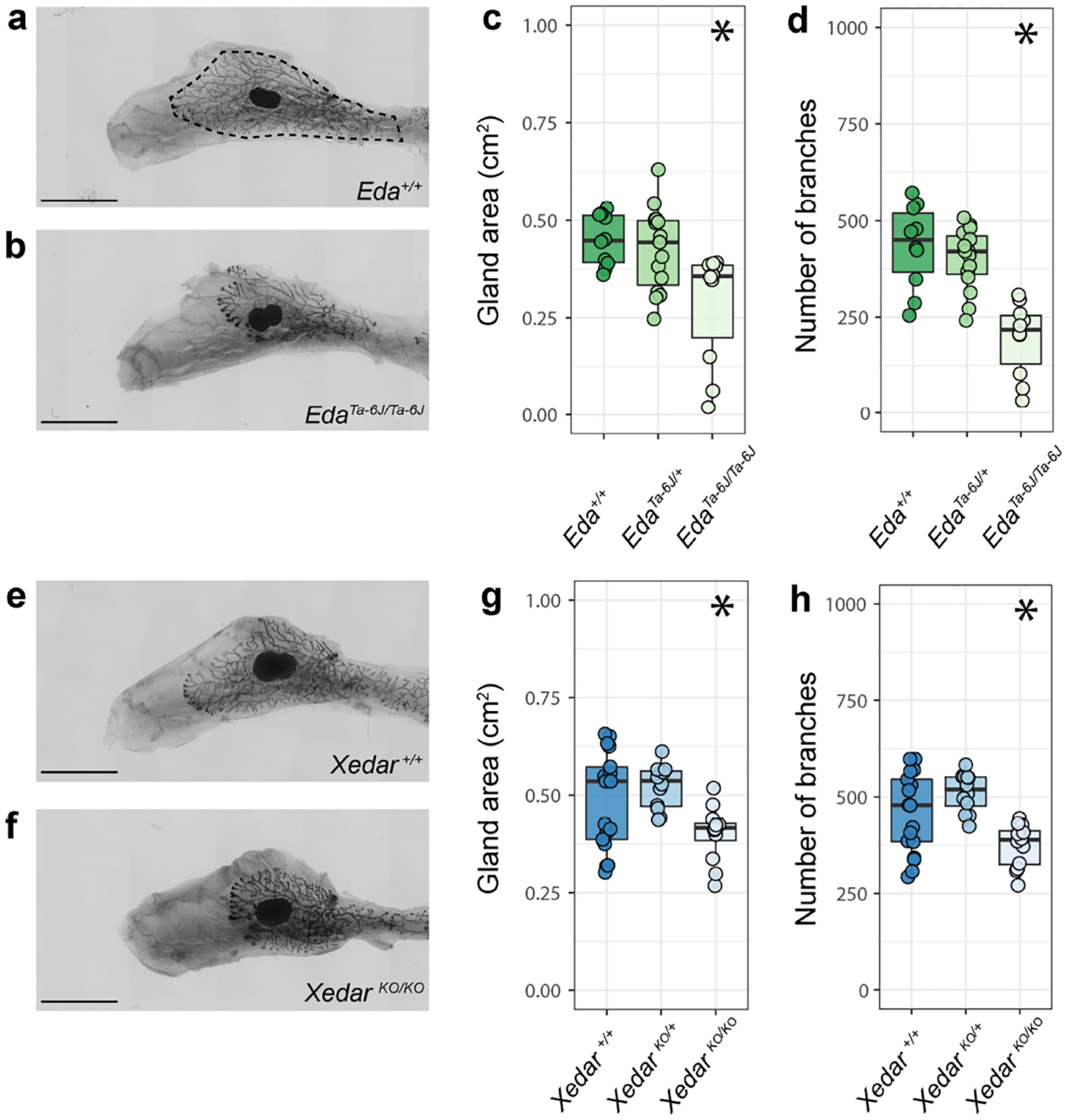

To establish a baseline spectrum of Eda-sensitive mammary phenotypes and to quantify the magnitude of effects of Eda loss on these traits, we evaluated two primary mammary traits previously reported to be attenuated in Eda mutant females, namely, the size of the mammary gland (measured as the area invaded by the mammary epithelium into the mammary fat pad stroma), and the extent of branching of the mammary ductal tree (Chang et al. 2009; Voutilainen et al. 2012; Wahlbuhl et al. 2018), (Figure 1a–d). Analyses of the left and right, 4th inguinal mammary glands of six-week-old, virgin female mice confirm significant decreases in both gland area and branching in EdaTa−6J homozygotes as compared to heterozygous and wildtype females on a C57BL/6J genetic background (Figure 1a–d and Table S1; χ2 =9.26(2), P<0.05; χ2 =17.9(2), P<0.05, respectively). Because mammary branching increases with body size in C57BL/6 sub-strains (Figure S1) and EdaTa−6J mice are smaller than their littermates (Table S1; χ2 =10.5(2), P<0.05), we confirmed that the disruption of branching that occurs with the loss of EDA signaling persists when branching is scaled by body size (Table S1; branches per gram; χ2 =17.6(2), P<0.05). The effect of Eda on mammary morphogenesis appears to be restricted to the epithelium as we do not find an effect of Eda disruption on the area of the mammary stroma, or fat pad (Tables S1, χ2 =2.31(2), P=0.315).

Figure 1. Xedar is required for development of Eda-dependent mammary epithelial traits.

a,b. Representative images of the 4th inguinal mammary gland from six-week-old, virgin female mice of designated Eda genotypes on C57BL/6J genetic background (+: wildtype allele). Dotted line indicates gland area. c. Area of the mammary epithelial tree across Eda genotypes. d. Epithelial branch count across Eda genotypes. e, f. Representative images of the 4th inguinal mammary glands from six-week-old virgin mice of designated Xedar genotypes on C57BL/6N genetic background (KO: Knock Out allele). g. Area of the mammary epithelial tree across Xedar genotypes. h. Epithelial branch count across Xedar genotypes. Boxplots show median and quartile distributions for genotype categories. Dots represent phenotype values for individual mice analyzed in these experiments. Asterisks indicate P<0.05 by Kruskal Wallis testing. Scale bar = 5mm.

Disruption of Xedar in C57BL/6N female mice affects both Eda-sensitive mammary gland traits. XedarKO female mice exhibit reduced epithelial gland area and branching when compared to wildtype and hemizygous XedarKO females (Figure 1e–h, Table S1: χ2 =9.41(2), P<0.05; χ2 =13.2(2), P<0.05, respectively). As with the loss of Eda, the effect of Xedar disruption is still observed when branching is scaled to body weight (Table S1: χ2 =18.5(2), P<0.05) and is restricted to the epithelium with no effect on fat pad area (Table S1: χ2 =0.19(2), P=0.906).

Since the C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N substrains show comparable baseline branching and gland size phenotypes (Figure 1a–h), we could qualitatively compare the effects of disrupting Eda and Xedar receptor on each of these mammary characteristics. Disrupting each gene results in a reduction of epithelial growth and branching. Branching is more severely attenuated with the loss of Eda than with the loss of Xedar, suggesting that Eda is able to support some branching in the absence of Xedar. Nevertheless, our data implicate Xedar in the differentiation of the adult mammary tree and provide direct evidence that Xedar affects Eda-dependent ectodermal appendage phenotypes.

The effect of Xedar on mammary epithelial traits is dependent on genetic background

The patterns of growth and branching of the mammary epithelium vary among mouse strains (Gardner and Strong 1935; Naylor and Ormandy 2002). Nonetheless, the effect of Eda disruption has been reported across several mouse strains (Chang et al. 2009; Voutilainen et al. 2012). Indeed, we observe that disruption of Eda on an FVB/N strain background has consistent effects with those we observe in C57BL/6J mice (Table S1). To determine if Xedar loss showed similar phenotypic penetrance across genetic backgrounds, we examined the necessity of Xedar for normal mammary development in a second and genetically diverged laboratory mouse strain by backcrossing our XedarKO allele onto FVB/N for at least four generations (N4) and compared the results to our C57BL/6N study (Lilue et al. 2018).

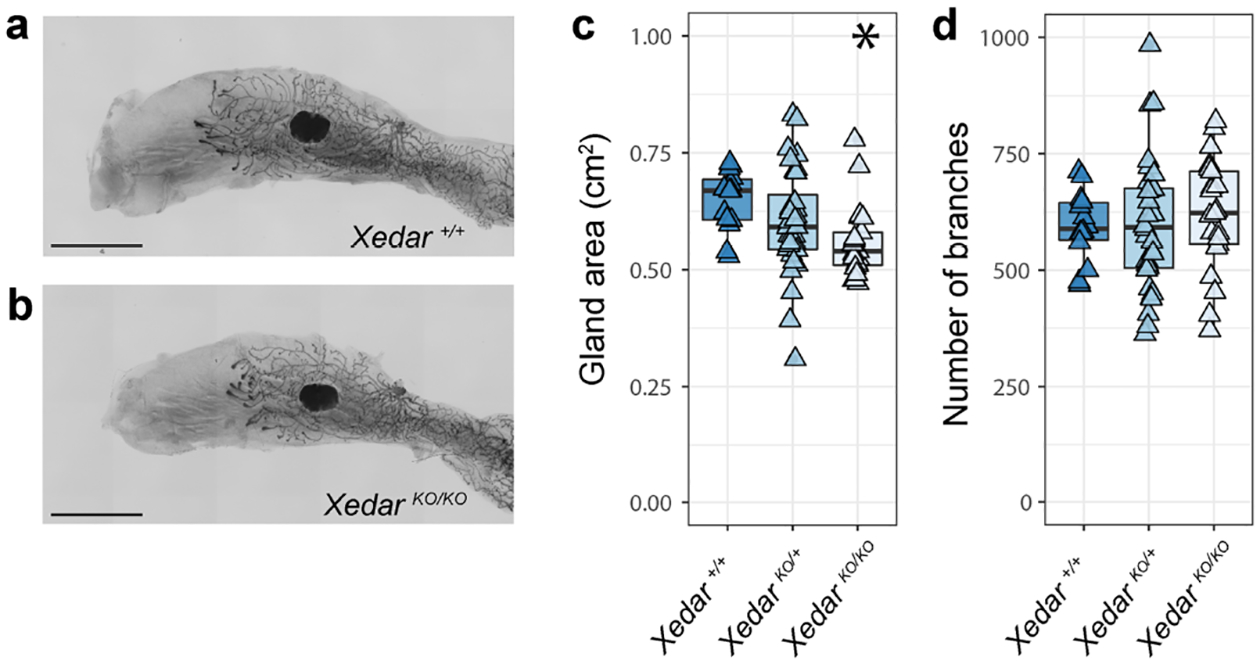

In six-week-old virgin N4 FVB/N female mice, mammary glands are larger and more branched than those of C57BL/6N mice even when accounting for the larger body size observed in the FVB/N strain (Figure S2, Table S1). Mammary gland area is significantly affected by Xedar genotype on an N4FVB/N background, with homozygous XedarKO females having a reduced gland area compared to wildtype or hemizygous carriers (Figure 2a–c and Table S1; χ2 =10.0(2), P<0.01). These data demonstrate that Xedar acts to promote the growth of the mammary epithelium on this genetic background much as is does in the C57BL/6N strain. In contrast, disruption of Xedar does not affect the number of mammary branches in FVB/N mice (Figure 2a, b, d and Table S1: gland area, χ2 =0.85(2), P=0.651). We find that puberty proceeds normally in XedarKO homozygous and hemizygous mice as measured by the day estrous onset, indicating that systemic effects of altered puberty can be excluded as a possible cause for the phenotypes we observe (Figure S3).

Figure 2. Xedar is necessary for post-pubertal mammary epithelial growth but not branching on an FVB/N genetic background.

a,b. Representative images of the 4th inguinal mammary gland of six-week-old, virgin, N4FVB/N female mice of the designated Xedar genotypes. c. Area of the mammary epithelial tree across Xedar genotypes (+: wildtype allele; KO: Knock Out allele). d. Number of epithelial branches within the mammary gland across Xedar genotypes. Boxplots show median and quartile distributions in each genotype category. Triangles represent phenotype values for individual mice analyzed in these experiments. Asterisks indicate P<0.05 by Kruskal Wallis tests. Scale bar = 5mm.

Xedar’s ability to promote epithelial growth in two different mouse strains, but to promote branching in a strain-specific manner, suggests that genetic modifiers may influence the extent to which EDA-A2/XEDAR signaling contributes to Eda-dependent mammary phenotypes. These data suggest that genetic context may have a profound influence on the phenotypic implications of Xedar variants, particularly in diverse species such as humans.

Xedar loss does not potentiate Edar-dependent mammary defects

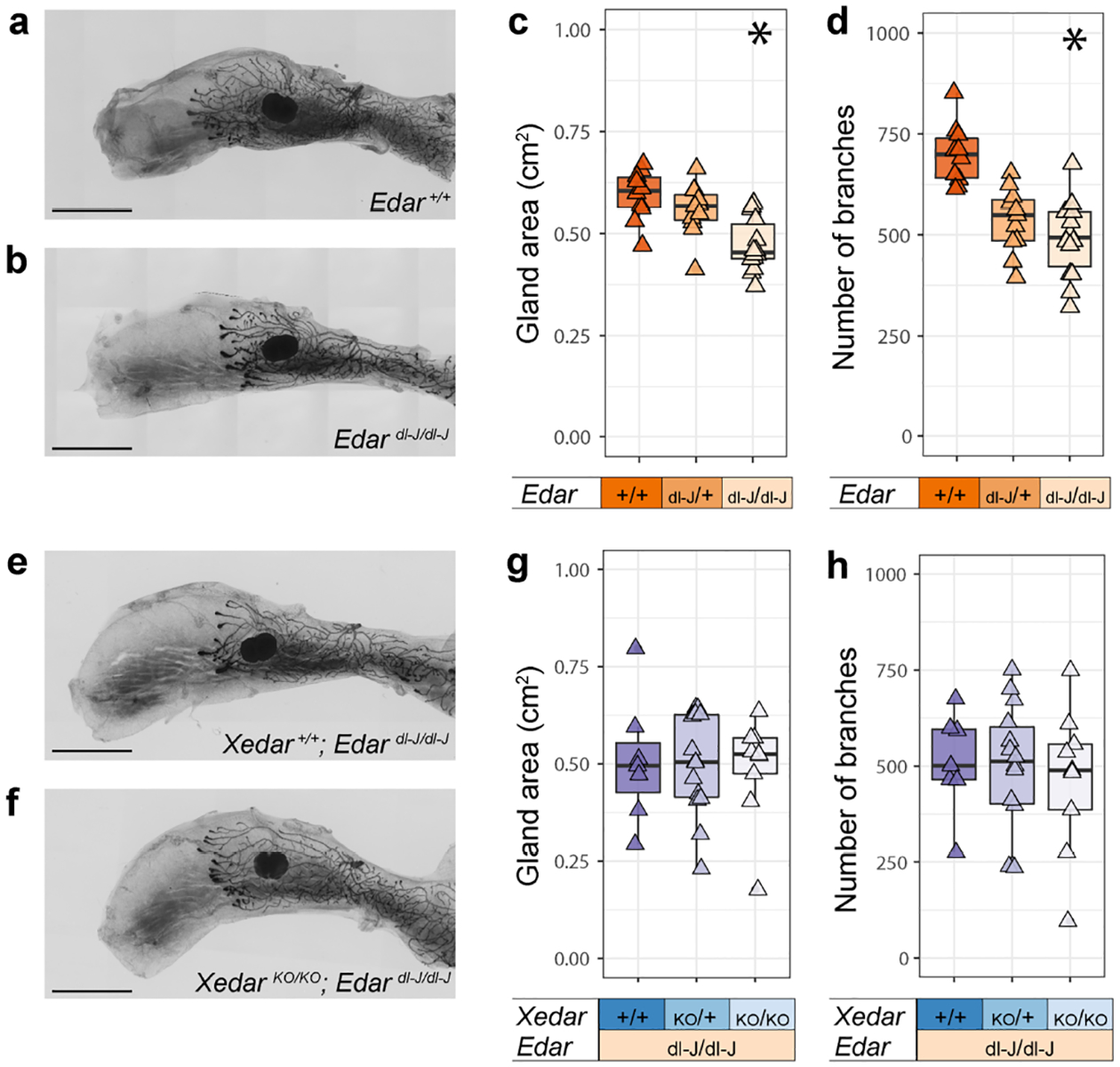

In light of our finding that Xedar impacts mammary phenotypes known to be sensitive to the EDA-A1/EDAR signaling axis, we investigated whether Xedar and Edar may independently or redundantly mediate the effects of Eda on mammary epithelial growth and branching. To this end, we analyzed mammary gland phenotypes in mice carrying the classical downless J Edar allele (Edardl-J), which was previously reported to encode a recessive EDAR variant responsible for producing HED-like phenotypes in the mouse (Chang et al. 2009; Headon and Overbeek 1999). Consistent with previous reports, gland area and branch number are significantly reduced in the mammary glands of six-week-old virgin female mice homozygous for the Edardl-J mutation (Figure 3a–d; Table S1; χ2 =14.2(2), P<0.05; χ2 =18.5(2), P<0.05, for gland area and branching, respectively). Notably, Edardl-J heterozygotes are intermediate in branch number between wildtype controls and homozygotes, highlighting the sensitivity of this phenotype to EDA-A1/EDAR signaling (Figure 3d). This finding is consistent with the growing evidence that Edar is haploinsufficient for a subset of ectodermal appendage phenotypes (Kamberov et al. 2013).

Figure 3. Edar is epistatic to Xedar in the regulation of post-pubertal mammary epithelium.

a,b. Representative images of the 4th inguinal mammary glands of six-week-old, virgin female mice of the designated Edar genotypes (+: wildtype allele; dl-J: downless J Edardl-J allele). c. Area of the mammary epithelial tree across Edar genotypes. d. Number of epithelial branches of the mammary gland across Edar genotypes. e,f. Representative images of the 4th inguinal mammary glands of six-week-old, virgin female mice with compound disruptions in Edar and Xedar (KO: Knock Out allele). g. Area of the mammary epithelial tree across the designated Edar and Xedar compound genotypes. h. Number of epithelial branches of the mammary gland across the designated Edar and Xedar compound genotypes. Triangles represent phenotype values for individual mice analyzed in these experiments. Asterisks indicate P<0.05 by Kruskal Wallis tests. Scale bar = 5mm.

By intercrossing Edardl-J mice with XedarKO mice, we generated females that are homozygous for the Edardl-J mutation and either wildtype, hemizygous or homozygous for the XedarKO allele. Analysis of mammary gland area and branch number in these mice does not reveal any effect of the loss of Xedar beyond the loss of Edar alone (Figure 3 e–h; Table S1; χ2 =0.22(2), P=0.892; χ2 =0.22(2), P=0.895).

The failure of Xedar disruption to potentiate Edar-dependent mammary phenotypes suggests that while Xedar and Edar can function independently, Edar is epistatic to Xedar in the regulation of mammary epithelial differentiation and growth. This may reflect a difference in the timing during which the two receptors regulate mammary morphogenesis or a difference in the downstream signaling mechanism engaged by each branch of the Eda pathway in this context. Previous studies have implicated NFkB as the major mediator of EDA-A1/EDAR signaling in mammary gland development, raising the possibility that in the context of the mammary gland, XEDAR functions through alternative signaling mediators, such as JNK signaling (Kumar et al. 2001; Lindfors et al. 2013; Sinha et al. 2002; Voutilainen et al. 2015). Thus, our results suggest that multiple mechanisms may converge to regulate the mammary epithelial tree downstream of Eda.

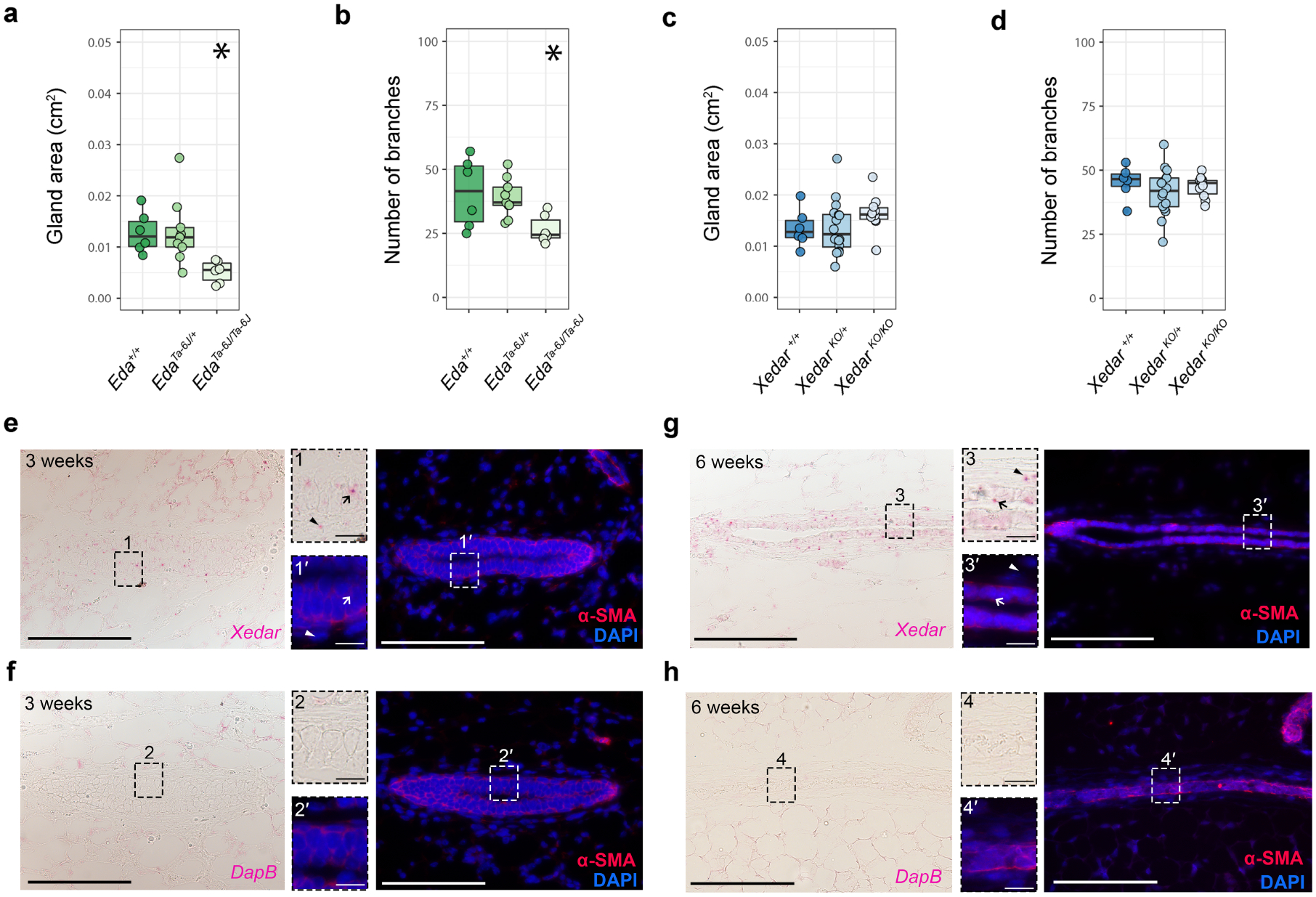

Xedar effects on mammary gland differentiation are temporally restricted

The development and differentiation of the mammary epithelium occurs in distinct stages beginning in mid-embryogenesis and continuing into adulthood (McNally and Martin 2011; Myllymäki and Mikkola 2019; Watson and Khaled 2008). Consistent with previous reports, we find that branching and size of the epithelial mammary tree is significantly reduced not only during the late pubertal period but also in pre-pubertal homozygous EdaTa−6J mice at three weeks of age (Figure 4a,b: Gland area: χ2=10.2(2), P<0.05; branches: χ2=7.66(2), P <0.05) (Chang et al. 2009; Lindfors et al. 2013; Voutilainen et al. 2015; Voutilainen et al. 2012). In contrast, we do not observe significant differences in mammary gland area or epithelial branch number in three-week old, female mice carrying zero, one or two copies of the XedarKO allele (Figure 4c,d: Gland area: χ2=2.15(2), P =0.341; branches: χ2=1.58(2), P =0.452). These data contrast with the effects of Edar disruption, which alters gland development at multiple stages including embryonically and during the pre-pubertal period (Lindfors et al. 2013; Voutilainen et al. 2015; Voutilainen et al. 2012). Instead, Xedar’s effects are temporally restricted to the stage when hormonal cues provide the major directives for gland maturation. This is intriguing given that Xedar expression is evident in the mammary epithelium and in the mammary stroma at this stage and also during embryonic stages of mammogenesis (Figure 4e, f;). The expression of Xedar persists at six weeks, the stage when Xedar-dependent phenotypes are evident in the gland. At this stage, we detect Xedar transcripts in both the basal myoepithelial cells of the mammary gland, which also express the marker alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA), and in the surrounding mesenchyme (Figure 4g, h)(Deugnier et al. 1995; Haaksma et al. 2011). Since mammogenesis requires reciprocal signaling between the gland and the mesenchyme, these data raise the possibility that XEDAR may mediate EDA-A2 effects on mammary growth by both direct and indirect signaling to the mammary gland itself (Watson and Khaled 2008).

Figure 4. Spatio-temporal specificity of Xedar in mammogenesis.

a-d. Assessment of 4th inguinal mammary gland characteristics in three-week-old, virgin wildtype, Eda mutant, and Xedar mutant mice. Area of the mammary epithelial tree (a) and branch count (b) in three-week-old wildtype, hemizygous, and homozygous EdaTa−6J female mice (+: wildtype allele). Area of the mammary epithelial tree (c) and branch count (d) in mammary glands of wildtype, hemizygous, and homozygous XedarKO female mice (KO: knock out allele). Dots and whiskers show median and quartiles. Asterisks indicate P<0.05 by Kruskal Wallis tests. e-h. Xedar mRNA expression in the 4th inguinal mammary glands of female mice at three- (e) and six -weeks (g). Xedar expression is visualized using RNAscope detection (red dots, brightfield image panels). Sections were counterstained with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, red) antibody to detect basal myoepithelial cells and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue) to visualize the nuclei (fluorescent, darkfield panels). Basal myoepithelial cells (arrow); mesenchymal cells of the mammary fat pad (arrowhead). f, h RNAscope detection with the negative control dapB probes (red dots, brightfield image panels) of three- (f) and six- (h) week-old, virgin, female mice. Magnified images corresponding to the boxed regions from each image are show. Main panels scale bar = 0.1mm, insets scale bar = 0.010 mm.

The temporal restriction of the XedarKO mammary phenotypes suggests a model in which Xedar and Edar differentially contribute to the regulation of mammary epithelial development and differentiation downstream of Eda at multiple stages of mammogenesis. In so doing, our findings point to a complex underlying basis for the effects of Eda on mammary glands. This may help to explain the incomplete rescue of mammary phenotypes in Tabby mice by EDA-A1 alone and supports a contribution from the EDA-A2/XEDAR signaling axis in the etiology of mammary defects in human XLHED carriers. Given the dynamic nature of the mammary gland, which is subject to dramatic changes in growth, functionalization, and regression, future experiments are needed to understand whether Xedar contributes to Eda-dependent phenotypes in other contexts, beyond the pubertal period. This is important because Eda loss of function is associated with persistent mammary phenotypes in both humans and mice (Cluzeau et al. 2011; Wahlbuhl et al. 2018). The generation of conditional alleles that enable temporal and tissue specific disruption of Xedar would greatly enhance such efforts. These genetic tools would also make it possible to parse out whether Xedar-dependent mammary phenotypes are directly attributable to Xedar expression within one or more of the mammary tissues we report here or are an indirect consequence of Xedar function in other tissues such as the skeletal muscle where this gene is also highly expressed and influences systemic, metabolic phenotypes (Awazawa et al. 2017; Newton et al. 2004).

In a broader context, our study provides evidence implicating the EDA-A2/XEDAR signaling axis in the regulation of ectodermal appendage phenotypes. Unlike the effects of other characterized components of the Eda pathway on ectodermal appendage traits, the effects of Xedar appear to be restricted to the mammary gland (Newton et al. 2004). Our finding that Xedar’s effects on the mammary gland can be sensitive to genetic background is noteworthy given that a derived XEDAR coding variant (XEDAR R57K, rs1385699) is highly differentiated among modern humans and was computationally identified as a potential target of positive natural selection in East Asia (Sabeti et al. 2007). Intriguingly, we have previously reported that a strongly selected coding variant of EDAR (EDARV370A, rs3827760) that is prevalent in present-day East Asian populations has pleiotropic effects on a subset of EDA-dependent ectodermal appendage traits, including on mammary gland branching (Kamberov et al. 2013). Thus, our findings raise the possibility that an additional EDA pathway effector, XEDAR, may also contribute to evolutionarily significant differences in mammary epithelial traits among modern humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Mice were housed in groups (up to 5 animals per cage) on a 12-hour light-dark cycle with continuous access to food and water. Pups were weaned at 3 weeks and raised thereafter in single sex groups. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with regulations and approvals by the Harvard Medical School, the Perelman School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees, and in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Mouse lines

Xedar deficient mice (Xedar knock-out (XedarKO)) mice have been previously described (Newton et al. 2004) and were obtained under material transfer agreement #OM-212731 from Genentech. XedarKO mice harbor a targeted disruption in exon 4 of the Xedar locus leading to deletion of the XEDAR transmembrane domain and a non-functional protein (Newton et al. 2004). XedarKO mice were obtained on a C57BL/6N genetic background and were maintained on C57BL/6N by further backcross to C57BL/6NTac (Taconic) mice. In addition, XedarKO mice were separately backcrossed on to FVB/NCrl (Charles River) for at least four generations for analyses pertaining to effects of genetic background on mammary phenotypes. Eda Tabby 6J (EdaTa−6J) mice (Jackson Labs (JAX) Stock #:000338, Aw-J-EdaTa−6J/J)(Srivastava et al. 1997) harbor a base pair deletion (at position 1049) in Ectodysplasin (Eda) that results in a frameshift mutation and the production of a non-functional, truncated protein, were maintained on a C57BL/6J background (Jackson Labs C57BL/6J) and backcrossed onto FVB/NCrl (Charles River) for 4 generations to examine strain effects. Edar downless J (Edardl-j) mutant mice were previously described (Headon and Overbeek 1999) and obtained from Jackson labs (JAX stock #:000210, B6C3Fe a/a-Edardl-J/J) and were backcrossed onto FVB/NCrl for at least eight generations prior to analyses.

To examine if Xedar deficiency could potentiate mammary phenotypes in the context of diminished EDAR signaling, we created mice with compound homozygous deficiency in Xedar and Edar on an FVB/N background. These lines were separately backcrossed to FVB/NCrl (Charles River) for four and eight generations, respectively, before the intercross. Experimental mice were either agouti or albino. All mice analyzed in the compound test crosses were Edardl-J/dl-J and showed symptoms of ectodermal dysplasia, including thin coat and a hairless, kinked tail.

Genotyping

XedarKO mice were genotyped using the following primers: Xedar-1 5’-tcgcaggactatgattgctaggc; Xedar-2 5’-gccatctgcatcaggtttcctatc; Xedar-3 5’-aggaaggcccattatcatgcagtc; Xedar-4 5’- ccagaggccacttgtgtagcg. The resulting PCR products are distinguishable by size using gel electrophoresis (wildtype band: 616 base pairs, mutant band: 302 base pairs).

Edardl-J mice carry a mutation in the ectodysplasin receptor that results in G/A substitution (5’gtgaaaacatggcgccaccttgcc G(wt)/A(dl-J) agagctttggactgaag3’) in the Edar locus and an E379K amino acid change (Headon and Overbeek 1999). The dl-J mutation was genotyped by sequencing the PCR product using the following primers (dl(J)-F 5’-gtctcagccccaccgagttg; dl(J)-R 5’- gtggggaggcaggtggtaca) to amplify genomic DNA from mouse tail biopsies. Tabby homozygote (EdaTa−6J/Ta−6J), hemizygote (Edawt/Ta−6J), and wildtype mice can be readily distinguished by eye when bred on pigmented strain. Homozygotes exhibit ectodermal dysplasia hair phenotypes and heterozygotes have a striped “tabby” coat. To allow our EdaTa−6J heterozygotes to be visually genotyped on the FVB/N background (which is not possible in an albino), we maintained the line with an Aw-J agouti allele.

Tissue preparation

The 4th and 5th inguinal mammary glands and associated fat pad were dissected from three week and six week-old virgin female mice. Whole mount mammary preparations were made as follows: glands were fixed flat in Carnoy’s fixative (6 parts ethanol, 3 parts chloroform, 1 part glacial acetic acid) for 2 hours at room temperature and stored in 70% ethanol. Following rehydration, glands were stained overnight with Carmine alum solution (1g carmine Sigma C1022 with 2.5g aluminum potassium sulfate Sigma A7167 to 500ml with distilled water, boiled and filtered). Stained glands were dehydrated, cleared in xylenes, flat-mounted on glass slides, and imaged in brightfield with an Olympus VS120 slide scanner microscope.

Analysis of mammary phenotypes

Mammary phenotypes were assessed using digital images analyzed in FIJI (NIH/ImageJ) with the Bioformats importer (Schindelin et al. 2012). Automatic branch counting was tested but was not as accurate as manual counting. Therefore, ductal termini (branch tips) were counted manually using the FIJI Cell Counter plugin. Images were blind analyzed at least two times to ensure accuracy and reproducibility of measurements. Fat pad area was measured from the main lactiferous duct to the dorsolateral border. Gland length was measured from the distal-most ductal termini at the dorsal and ventral edges of the gland, capturing the maximum bidirectional growth of ductal tissue area across the fat pad. Gland area was measured by capturing the area invaded by the mammary epithelium from branch tip to tip across the extent of the mammary fat pad (see Figure 1). Left and right 4th mammary gland counts and measurements were averaged for each individual in all experiments except the Xedar-Edar compound cross and the developmental series for which only left glands were used.

Determination of estrus onset

Beginning on postnatal day 20 (P20), the vaginas of virgin, female mice (FVB/N background and hemizygous or homozygous for the XedarKO allele) were observed daily, and the day of of estrus onset was tabulated, as previously described (Ajayi and Akhigbe 2020). Data reported are obtained from females from two different litters.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in R Statistical Software (v4.1.2) (R Core Team 2022). Mammary characteristics were compared using Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests, as normalcy requirements of parametric analysis were not met for all distributions in the dataset. Parametric and non-parametric analyses gave the same qualitative results in 94.7% of tests performed.

A minimum of ten females from each genotype class were used in all comparisons except the compound Xedar-Edar experiment for which only 7 Xedar wildtype and 9 XedarKO/KO; Edardl-J/dl-J compound mutant animals could be acquired. For our strain comparison, wildtype animals from all mouse lines were combined, resulting in 27 C57BL/6N and 34 FVB/N wildtype animals. This information is available in Table S1.

Assessment of significance of differences in estrus timing between XedarKO hemizygous and homozygous knock-out female mice was assessed by an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s T-test.

in situ hybridization

CD1/NCrl (Charles River) embryos were harvested on embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5), fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cryo-sectioned at 10 μm. The 4th inguinal mammary gland was dissected from 3 or 6 week-old CD1/NCrl virgin female mice fixed overnight in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in parafilm for posterior sectioning at 10 μm. RNAscope assay was performed as per manufacturer’s instructions for fixed frozen or Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded tissue and using RNAscope 2.5 Chromogenic assay reagent kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics (ACD), United States). The Xedar (ACD: 531871), and the negative control dapB (ACD: 310043) probes were designed by ACD. Targeted regions for Xedar and dapB probes were 304 base pairs (bp) – 1253 bp and 414bp – 862bp in the transcript, respectively. Immunofluorescent staining to detect Keratin 14 (KRT14) or α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was performed after RNAscope detection on the same tissue sections. The KRT14 antibody detects the basal keratinocyte layer of the ectoderm including the cells of the developing mammary gland which are also derivatives of this layer. The α-SMA antibody detects basal myoepithelial cells derived from the basal keratinocyte layer of the developing mammary gland. Histological sections were prepared through the developing mammary bud and through muscle, in which Xedar was previously reported to be expressed (Awazawa et al. 2017; Newton et al. 2004). Briefly, samples were washed in PBS and blocked in PBS + 0.1% Tween (PBST) + 10% normal donkey serum before an overnight incubation in Cytokeratin 14 primary antibody (PRP155-P CK14, 1:10000, Covance) or α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Samples were washed in PBST and incubated with Alexa Fluor488(1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or Alexa Fluor647(1:250, Abcam) and 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:5000, Sigma Aldrich). Images were acquired on a Leica DM5500 microscope equipped with a Leica DEC500 camera.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Clifford J. Tabin for resources in support of this study (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the NIH Award R01HD032443). We also thank Joseph Patrice and Parimal Rana for excellent animal care. We thank Genentech for sharing the XedarKO mouse model (#OM-212731). We thank the Penn Biology and Diseases Resource-based Center Core A (P30-AR069589) and the Harvard Medical School NeuroImaging Facility with support from the Neural Imaging Center (P30-NS072030). The research reported in this publication was supported by a National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the NIH Award R01AR077690 and a National Science Foundation BCS-1847598 award to YGK. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors state no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data analyzed in this study are reported in the manuscript. All mouse strains analyzed in this study have been previously published and are available from the vendors and sources listed in the Material and Methods.

REFERENCES

- Ajayi AF, Akhigbe RE. Staging of the estrous cycle and induction of estrus in experimental rodents: an update. Fertil. Res. Pract 2020;6(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awazawa M, Gabel P, Tsaousidou E, Nolte H, Krüger M, Schmitz J, et al. A microRNA screen reveals that elevated hepatic ectodysplasin A expression contributes to obesity-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Nat. Med. Nature Publishing Group; 2017;23(12):1466–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs LC, Mikkola ML. Early inductive events in ectodermal appendage morphogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 2014;25:11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal ML, Lewis JR, Mauldin EA, Tardivel A, Ingold K, Favre M, et al. Significant Correction of Disease after Postnatal Administration of Recombinant Ectodysplasin A in Canine X-Linked Ectodermal Dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2007;81(5):1050–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Jobling S, Brennan K, Headon DJ. Enhanced Edar Signalling Has Pleiotropic Effects on Craniofacial and Cutaneous Glands. PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2009;4(10):e7591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Sarfarazi M, Thomas NS, Roberts K, Harper PS. X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: DNA probe linkage analysis and gene localization. Hum. Genet 1987;75(4):378–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluzeau C, Hadj-Rabia S, Jambou M, Mansour S, Guigue P, Masmoudi S, et al. Only four genes (EDA1, EDAR, EDARADD, and WNT10A) account for 90% of hypohidrotic/anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia cases. Hum. Mutat 2011;32(1):70–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C-Y, Kunisada M, Esibizione D, Douglass EG, Schlessinger D. Analysis of the Temporal Requirement for Eda in Hair and Sweat Gland Development. J. Invest. Dermatol 2009;129(4):984–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C-Y, Schlessinger D. EDA Signaling and Skin Appendage Development. Cell Cycle Georget. Tex 2006;5(21):2477–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C-Y, Yin M, Sima J, Childress V, Michel M, Piao Y, et al. Involvement of Wnt, Eda and Shh at defined stages of sweat gland development. Development 2014;141(19):3752–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deugnier MA, Moiseyeva EP, Thiery JP, Glukhova M. Myoepithelial cell differentiation in the developing mammary gland: progressive acquisition of smooth muscle phenotype. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat 1995;204(2):107–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaide O, Schneider P. Permanent correction of an inherited ectodermal dysplasia with recombinant EDA. Nat. Med. Nature Publishing Group; 2003;9(5):614–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner WU, Strong LC. The Normal Development of the Mammary Glands of Virgin Female Mice of Ten Strains Varying in Susceptibility to Spontaneous Neoplasms. Am. J. Cancer 1935;25(2):282–90 [Google Scholar]

- Haaksma CJ, Schwartz RJ, Tomasek JJ. Myoepithelial cell contraction and milk ejection are impaired in mammary glands of mice lacking smooth muscle alpha-actin. Biol. Reprod 2011;85(1):13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headon DJ, Emmal SA, Ferguson BM, Tucker AS, Justice MJ, Sharpe PT, et al. Gene defect in ectodermal dysplasia implicates a death domain adapter in development. Nature 2001;414(6866):913–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headon DJ, Overbeek PA. Involvement of a novel Tnf receptor homologue in hair follicle induction. Nat. Genet 1999;22(4):370–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamberov YG, Wang S, Tan J, Gerbault P, Wark A, Tan L, et al. Modeling Recent Human Evolution in Mice by Expression of a Selected EDAR Variant. Cell 2013;152(4):691–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Eby MT, Sinha S, Jasmin A, Chaudhary PM. The Ectodermal Dysplasia Receptor Activates the Nuclear Factor-κB, JNK, and Cell Death Pathways and Binds to Ectodysplasin A*. J. Biol. Chem 2001;276(4):2668–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilue J, Doran AG, Fiddes IT, Abrudan M, Armstrong J, Bennett R, et al. Sixteen diverse laboratory mouse reference genomes define strain-specific haplotypes and novel functional loci. Nat. Genet. Nature Publishing Group; 2018;50(11):1574–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindfors PH, Voutilainen M, Mikkola ML. Ectodysplasin/NF-κB signaling in embryonic mammary gland development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2013;18(2):165–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis CA, Schneider P, Huttner K, Kirby N, Houser TP, Wildman L, et al. Prenatal Treatment of X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia Using Recombinant Ectodysplasin in a Canine Model. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2019;370(3):806–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally S, Martin F. Molecular regulators of pubertal mammary gland development. Ann. Med 2011;43(3):212–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola ML, Thesleff I. Ectodysplasin signaling in development. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2003;14(3–4):211–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen T, Ilmonen M, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Laurikkala J, Jaatinen R, et al. Ectodysplasin A1 promotes placodal cell fate during early morphogenesis of ectodermal appendages. Development 2004;131(20):4907–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen T, Pispa J, Mikkola ML, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Pakkasjärvi L, et al. Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by Ectodysplasin-A1. Dev. Biol 2003;259(1):123–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllymäki S-M, Mikkola ML. Inductive signals in branching morphogenesis – lessons from mammary and salivary glands. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 2019;61:72–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MJ, Ormandy CJ. Mouse strain-specific patterns of mammary epithelial ductal side branching are elicited by stromal factors. Dev. Dyn 2002;225(1):100–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K, French DM, Yan M, Frantz GD, Dixit VM. Myodegeneration in EDA-A2 Transgenic Mice Is Prevented by XEDAR Deficiency. Mol. Cell. Biol 2004;24(4):1608–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Varilly P, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Hostetter E, Cotsapas C, et al. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 2007;449(7164):913–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. Nature Publishing Group; 2012;9(7):676–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H, Faschingbauer F, Schuepbach-Mallepell S, Körber I, Wohlfart S, Dick A, et al. Prenatal Correction of X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia. N. Engl. J. Med 2018;378(17):1604–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha SK, Chaudhary PM. Induction of Apoptosis by X-linked Ectodermal Dysplasia Receptor via a Caspase 8-dependent Mechanism*. J. Biol. Chem 2004;279(40):41873–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha SK, Zachariah S, Quiñones HI, Shindo M, Chaudhary PM. Role of TRAF3 and −6 in the Activation of the NF-κB and JNK Pathways by X-linked Ectodermal Dysplasia Receptor*. J. Biol. Chem 2002;277(47):44953–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofaer JA, MacLean CJ. Dominance in threshold characters. A comparison of two Tabby alleles in the mouse. Genetics 1970;64(2):273–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Durmowicz MC, Hartung AJ, Hudson J, Ouzts LV, Donovan DM, et al. Ectodysplasin-A1 is sufficient to rescue both hair growth and sweat glands in Tabby mice. Hum. Mol. Genet 2001;10(26):2973–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Pispa J, Hartung AJ, Du Y, Ezer S, Jenks T, et al. The Tabby phenotype is caused by mutation in a mouse homologue of the EDA gene that reveals novel mouse and human exons and encodes a protein (ectodysplasin-A) with collagenous domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 1997;94(24):13069–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AS, Headon DJ, Schneider P, Ferguson BM, Overbeek P, Tschopp J, et al. Edar/Eda interactions regulate enamel knot formation in tooth morphogenesis. Dev. Camb. Engl 2000;127(21):4691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutilainen M, Lindfors PH, Lefebvre S, Ahtiainen L, Fliniaux I, Rysti E, et al. Ectodysplasin regulates hormone-independent mammary ductal morphogenesis via NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012;109(15):5744–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutilainen M, Lindfors PH, Trela E, Lönnblad D, Shirokova V, Elo T, et al. Ectodysplasin/NF-κB Promotes Mammary Cell Fate via Wnt/β-catenin Pathway. PLOS Genet 2015;11(11):e1005676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlbuhl M, Schuepbach-Mallepell S, Kowalczyk-Quintas C, Dick A, Fahlbusch FB, Schneider P, et al. Attenuation of Mammary Gland Dysplasia and Feeding Difficulties in Tabby Mice by Fetal Therapy. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2018;23(3):125–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlbuhl-Becker M, Faschingbauer F, Beckmann MW, Schneider H. Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia: Breastfeeding Complications Due to Impaired Breast Development. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2017;77(4):377–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CJ, Khaled WT. Mammary development in the embryo and adult: a journey of morphogenesis and commitment. Development 2008;135(6):995–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfart S, Hammersen J, Schneider H. Mutational spectrum in 101 patients with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and breakpoint mapping in independent cases of rare genomic rearrangements. J. Hum. Genet 2016;61(10):891–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M, Wang L-C, Hymowitz SG, Schilbach S, Lee J, Goddard A, et al. Two-Amino Acid Molecular Switch in an Epithelial Morphogen That Regulates Binding to Two Distinct Receptors. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2000;290(5491):523–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this study are reported in the manuscript. All mouse strains analyzed in this study have been previously published and are available from the vendors and sources listed in the Material and Methods.