Abstract

Targeted modification of endogenous proteins without genetic manipulation of protein expression machinery has a range of applications from chemical biology to drug discovery. Despite being demonstrated effective in various applications, target specific protein labeling using ligand-directed strategies are limited by stringent amino acid selectivity. Here, we present highly reactive Ligand Directed Triggerable Michael Acceptors (LD-TMAcs) that feature rapid protein labeling. Unlike previous approaches, the unique reactivity of LD-TMAcs enables multiple modifications on a single target protein, effectively mapping the ligand binding site. This capability is attributed to the tunable reactivity of TMAcs that enable the labeling of several amino acid functionalities via a binding-induced increase in local concentration, while remaining fully dormant in the absence of protein binding. We demonstrate the target selectivity of these molecules in cell lysate using carbonic anhydrase as the model protein. Furthermore, we demonstrate the utility of this method by selectively labeling membrane-bound carbonic anhydrase XII in live cells. We envision that the unique features of LD-TMAcs will find use in target identification, investigation of binding/allosteric sites and studying membrane proteins.

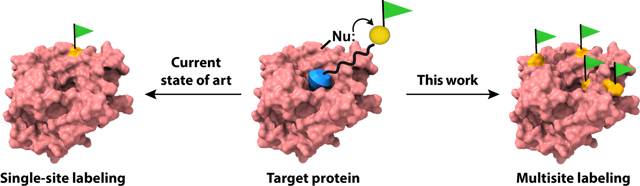

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Chemical modification of proteins has been of great interest because of potential utility in a variety of applications including therapeutic biologics, quantification, enrichment, imaging, and structural analysis.1–8 Modification of proteins typically involves a protein family, specific amino acid, single protein of interest, or specific region on the protein of interest.7,9–13 Selective modification of proteins can be accomplished by genetically engineering cells to express a protein bearing unnatural amino acids with reactive handles that are amenable for further bio-orthogonal functionalization.14,15 This method can be exquisitely specific but is labor intensive. To overcome this challenge, photoaffinity-based probes have been developed where photoreactive appendages generate reactive radicals that are rapidly captured by the neighboring protein. While the unrestrained reactivity of the photoaffinity based probes enables them to label virtually any protein regardless of their amino acid composition it results in off-target labeling, as this process is not dependent on the bound state of the ligand.16

Ligand-directed labeling approaches use ligand-protein interactions, where a protein-selective ligand is linked to a reactive warhead and a labeling functional group.9,17–23 The reactivity of the warhead with surface functionalities on the protein is substantially enhanced in the bound state, because of the higher local concentration of the reactive functionality. Many such approaches have been developed and utilized in a variety of applications including biosensing, enzyme caging, covalent inhibition, pulse-chase analysis, and for studying protein-protein interactions.7,17,20,22,24–26 The reactive warheads in these cases are primarily designed to attach a single label on the protein using the reactivity to a one type of amino acid, most commonly lysine or cysteine. This strict amino acid preference requires the presence of proximal nucleophiles around the ligand binding pocket. This means that a particular warhead cannot be used to label the target protein if there is no compatible amino acid around the ligand binding site. While the single labeling strategy offers advantages in many applications, a complementary approach with wider amino acid scope that is capable of installing multiple labels on specific protein surfaces would greatly expand the repertoire of ligand-directed protein labeling, such as in the context of protein surface mapping. Such a possibility is schematically illustrated in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1b, incorporation of multiple labels offers a much better opportunity to map the ligand binding site, compared to a single site labeling.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of protein labeling by LD-TMAcs. When the ligand is installed on the ester group of the LD-TMAc it acts as covalent inhibitor (a). If the ligand is installed on the leaving group (b), it is free to leave the active site after the labeling reaction. Then, an unoccupied active site can bind unreacted LD-TMAcs for additional rounds of labeling.

For multi-labeling of specific proteins using the ligand-directed strategy, two criteria must be satisfied: (i) although the reactivity of the warhead must be high to satisfy the first condition, it must be relatively dormant when not bound to the protein such that the labeling occurs only on the surface proximal to the ligand binding pocket; (ii) the reactive warhead should be able to label many amino acid types on a protein surface. Recently, we reported a library of triggerable/tunable Michael acceptors (TMAcs) that exhibit a range of reactivity with nucleophilic functionalities.27 In the context of functional groups that are presented on protein surfaces, TMAcs have been shown to label 13 different amino acids,28 making them valuable for covalent labeling mass spectrometry (MS) experiments.29 The reactive tunability of TMAcs over six orders of magnitude offer the unique potential to design molecules that could afford ligand-directed labeling, while also incorporating multiple surface functionalities on proteins. In this manuscript, we report on ligand-directed TMAcs (LD-TMAcs) that label specific proteins but on multiple sites. In addition to demonstrating this possibility with soluble proteins, we also show that the strategy can be used to specifically label proteins in cell lysates and specific membrane proteins on live cells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Molecular design and characterization of carbonic anhydrase (CA) labeling by LD-TMAc reagents.

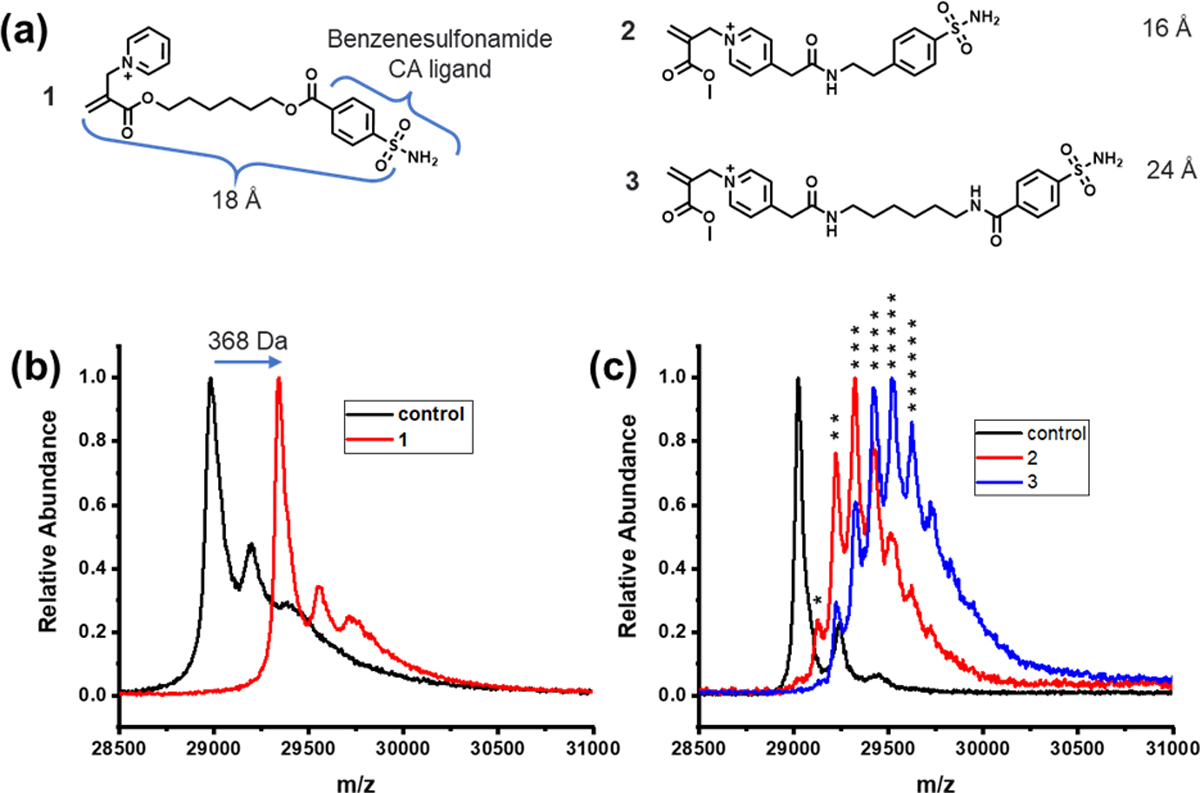

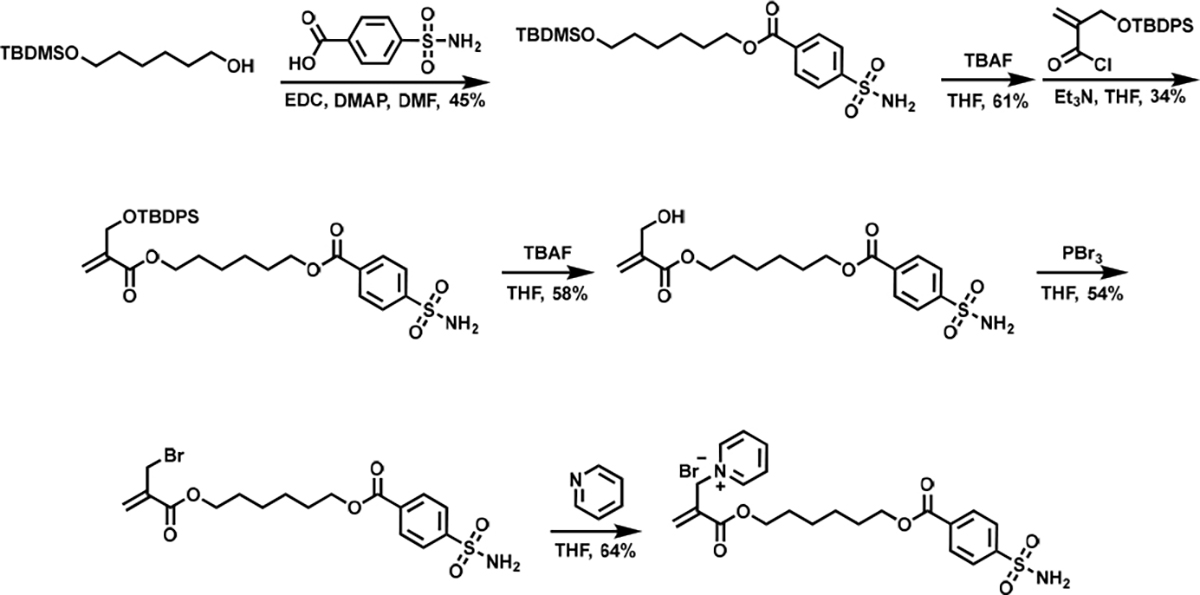

Two different types of LD-TMACs, viz. the ones that can label the protein surface at multiple sites and ones that functionalize at a single site, have been designed. Ligand-directed functionalization of proteins is achieved when the ligand binds to a specific site in the protein, which in turn brings the reactive Michael acceptor moiety in close proximity to the nucleophilic functionalities in the protein. This increased local concentration causes the reactive moiety to attach to an accessible and complementary surface functionality on the protein surface. In LD-TMACs reported here, the reactive functionality is an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl molecule that acts as a Michael acceptor, the ligand is based on benzenesulfonamide that is known to be a nM binder to the model protein carbonic anhydrase (CA)30, and the leaving group is a pyridinium moiety. Representative LD-TMAc structures are shown in Figure 1. When the leaving group is separate from the ligand, the reaction between the protein surface and the TMAc functionality affords covalent attachment of the ligand to the protein at an optimal location; i.e., this reaction results in the generation of a covalent inhibitor. This possibility is illustrated with LD-TMAc in Figure 1a. On the other hand, if the leaving group is part of the linker that connects the TMAc functionality and the ligand, then the reaction with the protein surface functionality would disconnect the ligand moiety from the LD-TMAc, while concurrently labeling the protein surface. As the product sulfonamide ligand in this process is non-covalently bound to the protein, it can be displaced by another LD-TMAc molecule in solution and cause the protein surface labeling to occur again. This opens up the possibility of multiple labeling of protein surfaces, as illustrated with LD-TMAc in Figure 1b. The design hypotheses mentioned above were tested by reacting bovine carbonic anhydrase II (bCAII) with LD-TMAcs 1-3 (Figure 2a). Syntheses of LD-TMAcs is exemplified in Scheme 1 with the synthesis of 1, while experimental details and characterization of all LD-TMACs are provided in the Supporting Information (SI). To test the ligand-directed functionalization of proteins, bCAII (5 μM) was incubated with 10 μM LD-TMAcs for 2 hours in PBS buffer at 37 °C. Extent of protein labeling was evaluated using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) (Figure 2 b, c). When treated with 1, the bCAII spectrum shifts by 368 Da (Figure 2b). This shift corresponds to a single adduct from 1 that includes the sulfonamide ligand, with no discernible evidence for multiple adducts in this experiment. On the other hand, under the same concentration and conditions, bCAII is labeled by multiple reagent molecules when treated with LD-TMAcs 2 or 3 (Figure 2c). The SN2’ reaction of molecules 2 and 3 would incorporate a label with the molecular weight of 99 Da. Indeed, multiple new peaks appear with a separation of 99 Da. Up to six labels are observed with LD-TMAc molecules 2 and 3. Interestingly, the extent of multiple label incorporation is higher for 3 relative to 2, as discerned by the relative abundance changes in the adducts. This higher labeling extent is attributed to the longer linker length in 3 that allows better reach for the protein surface functionalities. The linker length between the electrophilic site in the TMAc to the sulfur atom on the sulfonamide in 1, 2, and 3 are approximately 18, 16, and 24 Å, respectively. For this multisite labeling, frequent exchange of the ligand bound is a prerequisite. Benzenesulfonamide ligand on 3 has kon and koff of ~6×10−5 M−1s−1 and ~0.05 s−1 respectively.30,31 This means that it takes less than 30 seconds for a CA bound 3 to dissociate after which it can be exchanged for another. If 3 had koff of 2 × 10−4 s−1 or less, CA bound 3 would not dissociate for the entirety of this reaction of two hours; and more than one labeling would not be possible. Labeling results were also evaluated using electrospray ionization MS (ESI-MS) (Figure S1). These results reveal that bCAII labeling with 1 can result in doubly labeled proteins. This could either be due to a second labeling event while the covalently tethered ligand from the first label is in its unbound state, or a non-ligand directed labeling. bCAII labeling by a control TMAc without benzenesulfonamide ligand can also result in some non-ligand directed labeling, but also reveals that such a labeling is minimal (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Structure of LD-TMAc reagents and characterization of invitro bCAII labeling. (a) Molecular structure of LD-TMAc reagents 1–3. MALDI-TOF MS of bCAII (5 μM) incubated with (b) 1 (10 μM), PBS buffer, pH 7.4, 37 °C, 2 h, (c) 2 or 3 (10 μM), PBS buffer, pH 7.4, 37 °C, 2 h. Native bCAII has a molecular weight of ~29 kDa. Reagent 1 modification has an adduct of ~368 Da. Reagents 2 and 3 has modification of ~99 Da. * represents the number of labels by 2 or 3.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of LD-TMAc 1.

To further test whether the observed labeling is indeed due to ligand-directed increases in effective concentration, we carried out competitive inhibition experiments. Ethoxzolamide (EZA) is a strong binder with bCAII with the Kd of ~0.2 nM.32 When 100 μM of EZA was used as a competitive inhibitor during the treatment of bCAII with the LD-TMAcs, no protein modification is observed for 2 and 3, and only 11% modification for 1 confirming that the observed results are indeed a ligand-directed functionalization process (Figure S2).

A potential concern would be whether the reactivity of 1 would be substantially different from 2 and 3, because of the substituents at the para-position of the latter molecules. To test this possibility, we synthesized LD-TMAcs 5 and 6 containing a strong electron-donating methoxy and a strong electron-withdrawing carbonitrile moiety, respectively (Figure 3a). Protein labeling ability of 5 and 6 was compared with that of 1. As anticipated, we find 5 to be less reactive than 1, as the electron-donating methoxy unit resonance stabilizes the pyridinium cation causing it to be less effective as a leaving group. Similarly, the electron-withdrawing carbonitrile causes 6 to be more reactive than 1. Reaction rates were estimated from the ratio of MALDI-MS abundances of modified and unmodified bCAII with time (Figure 3b,c). In the presence of 100 μM EZA as a competitive inhibitor, 1, 5 and 6 have completion of only 11%, 7% and 28% respectively in two hours, supporting the ligand-directed labeling mechanism (Figure S2). Perhaps most importantly, only single labeling was observed in all three pyridinium-based LD-TMAcs, suggesting that subtle reactivity differences between 1 and 2 (or 3) do not explain the observed variations about the number of labels that are added upon reacting with 2 and 3. Moreover, it is crucial to be able to tune the kinetics of LD labeling as it depends on the affinity of the ligand being used.9,20,33 These results show that the kinetics of LD-TMAcs can be easily tuned by changing the leaving group, as was observed previously by our group.27

Figure 3.

Kinetics and tunability of LD-TMAc reagents. (a) Structure of LD-TMAc reagents 1, 5 and 6 with varying leaving groups. (b) Completion rate of bCAII labeling by 1, 5, 6 and in presence of competitive inhibitor EZA. Reaction conditions: 5 μM bCAII, 10 μM LD-TMAc, 100 μM EZA, PBS buffer, pH 7.4, 37 °C. (c) Reaction progress of bCAII labeling with 6 monitored by MALDI-TOF MS. o, native bCAII (MW: ~ 29 kDa); *, 6 labeled bCAII (+ 368 Da).

LD-TMAc regiospecific labeling around the ligand binding site.

Next, we were interested in testing if the multi-labeling features of the LD-TMAcs could map the region around the ligand binding site. To identify the labeling sites on the protein surface, bCAII was subjected to a tryptic digest following the labeling reaction with the LD-TMAcs. The product peptides were then analyzed using LC-MS/MS to identify the specific residues that were modified upon reaction with the LD-TMAcs (Table 1). Tandem mass spectra of the peptide modifications are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Table 1.

LD-TMAc targeted residues on bCAII

| Probe | Label Site | Modification % | SASA % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1† | His3 | 95 ± 4 | 81 |

| His63 | 50 ± 20 | 17.3 | |

|

|

|||

| 2† | His3 | 70 ± 20 | 81 |

| His63 | 60 ± 30 | 17.3 | |

| Ser181# | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 30 | |

| Ser171/Thr172 | 0.09 ± 0.08 | 31.5$ | |

| Lys166* | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 29.3 | |

|

|

|||

| 3‡ | His3 | 80 ± 30 | 81 |

| His63 | 70 ± 10 | 17.3 | |

| Ser72# | 30 ± 1 | 74.8 | |

| His2* | 2 ± 2 | 11.3 | |

| Ser28* | 1 ± 0.5 | 0 | |

| Ser64* | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Ser171/Thr172 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 31.5$ | |

| Lys250 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 29.2 | |

| Lys44 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 66.3 | |

Based on 6 replicates.

Based on 3 replicates.

Ser171 and Thr172 average.

An outlier replicate removed at at 95% confidence.

Statistically significant at 90% confidence. The rest of the data is statistically significant at 95% confidence.

On average, bCAII treated with 1 has 1.2 labels per protein as determined by measurements of the intact protein. The labeling occurs at one of the two sites: His3 (95 ± 4 %) and His63 (50 ± 20 %) (Figure 4a, left) (Figure S1), as determined after proteolytic digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis (see Supplemental Information for description of covalent labeling-MS method). These residues line the wall of the sulfonamide binding site and are within the 18 Å reach of LD-TMAc warhead. bCAII treated with 2 has an average of 2.2 labels per protein with the labeling spread across five sites: His3, His63, Ser181, Ser171/Thr172, and Lys166 (Figure 4a, middle). His3 and His63 dominate the labeling of the protein by 2, with modification extents of 70 ± 20% and 60 ± 30%, respectively. Like with reagent 1, these residues are close to the binding site and within the 16 Å reach of 2. Ser181, Ser171/Thr172, and Lys 166 are minimally labeled with modification extents of 0.3 ± 0.2%, 0.09 ± 0.08%, and 0.06 ± 0.07%, respectively. Ser171 and Thr172 neighbor each other on the same tryptic peptide, and either residue could be labeled as a result of ambiguous assignments from the MS/MS data (Figure S3). Ser171 and Thr172 are on the fringes of probe 2’s reach, whereas Lys166 and Ser181 are farther away. It is likely that Ser181 and Lys166 labeling occurs in a non-ligand directed manner. Under the same conditions, there is only negligible extent of bCAII labeling with a control TMAc molecule without the sulfonamide ligand (Figure S1). It should be noted that Lys166 labeling is only statistically significant at 90% confidence, unlike the other residues that are significantly labeled by 2 at a 95% confidence. bCAII treated with 3 has an average of 2.7 labels per protein with the labeling occurring at His3, His63, Ser72, Ser171/Thr172, Lys250, and Lys44 (Figure 4a, right). Like with reagents 1 and 2, His3 and His63 dominate the labeling of the protein quantitatively, with modification extents of 80 ± 30% and 70 ± 10%, respectively (Table 1) (Figure 4b). Table of predicted and found masses for ions on the MS-MS spectrum of Met58-Lys75 peptide labeled by reagent 3 on His63 is provided on Figure S4. Ser72 and Ser171/Thr172 are labeled with modification extents of 30 ± 1% and 0.3 ± 0.1%, respectively. These residues are somewhat distant from the sulfonamide binding site, but the ~24 Å long reach of 3 may allow their labeling. Lys250 and Lys44 are both minimally labeled (~0.1% labeling) and are likely too far away from the binding site to be labeled when the sulfonamide is bound (Figure S5). Thus, the labeling of these residues is likely indicative of non-ligand directed labeling. To give an idea on their reach, LD-TMAc reagents were superimposed on the crystal structure of sulfonamide bound bCAII (Figure 4a). Although statistically significant only at 90% confidence, His2, Ser28, and Ser64 are minimally labeled with modification extents of 2 ± 2%, 1 ± 0.5% and 0.5 ± 0.4%, respectively, and are all within reach of 3.

Figure 4.

Regiospecific labeling of LD-TMAc reagents. (a) Crystal structure of bCAII (PDB: 1V9E) with LD-TMAc reagents 1–3 superimposed on the zinc coordinated sulfonamide binding site. The amino acid residues labeled by LD-TMAC reagents 1, 2, and 3 are shown in their respective colors magenta, cyan, and green. (b) MS-MS spectrum of Met58-Lys75 peptide labeled by reagent 3 on His63. (c) Effect of LD-TMAc modification on carbonic anhydrase activity evaluated by a chromogenic assay.

To better understand the modification extents of each amino acid, we calculated solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of bCAII crystal structure (PDB: 1V9E) using GetArea34 with a probe radius of 1.4 Å (Table 1). After closely examining the SASA of each residue modified by probe 3, it is possible to deduce that higher solvent accessibility results in higher modification extent. However, this trend is observed only for the proximal residues that are within the reach of the LD-TMAc probes. His, Lys, Ser, and Thr residues with the highest SASA in bCAII are not labeled, highlighting proximity to the ligand binding site as a prerequisite (Figure S6). Owing to their binding site proximity, His3 and His63 are labeled by all three probes, and His3 has a higher modification extent in all three cases, despite the closer proximity of His63. This can be explained by the higher SASA of His3. The relatively high labeling extents of His63 and Ser72 can also be explained by their high SASA values. His2 with low solvent exposure faces competition with His3, which results in a low modification extent. Although Ser28 and Ser64 have little to no solvent exposure, their proximity to the binding might allow their minimal labeling. Additionally, although SASA values calculated using the crystal structure is useful to understand the protein structure, these values are not ideal to infer conclusions about the dynamic structure. Protein structural dynamics and LD-TMAc modifications on the protein structure might have facilitated the minimal labeling of these residues. Finally, despite being out of reach of the reagent, Lys250 and Lys44 have moderate to high solvent accessibility, allowing them to be minimally labeled in a non-ligand directed manner.

While there are other residues in the vicinity of sulfonamide binding pocket, factors such as LD-TMAc reagents’ sterics, length, and flexibility may not allow their labeling. In addition, low nucleophilicity, SASA, presence of other nearby residues with higher nucleophilicity, better positioning, and orientation may add to these factors. Among these residues, Thr197 and Thr198 lie right next to the Zn ion in the active site. However, they are not solvent accessible (SASA < 20%), and because the LD-TMAc’s electrophilic site is in the opposite end of sulfonamide ligand, the reactive site is therefore not conformationally accessible to these residues. No labels are found on Tyr6, Tyr69, and Lys170, but they are in close vicinity of His3, Ser72, and Ser171, respectively, which were labeled by 3. No labels are found on Thr131 despite having 56.1% SASA, being within the reach of 3 and having no nearby labeled residues. Finally, analysis of residues targeted by the minimal non-ligand directed labeling of the control TMAc molecule reveals that these residues minimally overlap with the residues targeted by ligand-directed labeling (Figure S1, S7). Therefore, the kinetically preferred residues by the TMAcs differ from the residues targeted by ligand-directed labeling.

These results show that LD-TMAcs are capable of comprehensive regiospecific labeling to afford ample information to elucidate the ligand/drug binding site. Affinity guided methods such as photoaffinity labeling and other LD approaches have been used to identify binding sites and allosteric sites,35–42 and the LD-TMAcs’ capability to label up to seven different residues around the binding pocket could make them a great complement to these methods.

To evaluate the effect of LD-TMAc modification on the enzymatic activity of bCAII, we conducted a chromogenic assay (Figure 4c). First, 5 μM bCAII was incubated with 10 μM 1, or 2 in PBS buffer, pH 7.4, 37 °C for two hours. After that, buffer exchange was carried out with fresh PBS to get rid of excess reagents and sulfonamide ligands. Then, 1 μM labeled bCAII was incubated with 2 mM nitrophenyl acetate, and absorbance at 400 nm was monitored over 90 seconds. Hydrolysis of nitrophenyl acetate by bCAII generates nitrophenol, which has a UV absorption peak at 400 nm. Compared to the steady increase of UV absorbance from the unmodified control bCAII activity, there is no significant change in absorbance for the reaction mixture of 1 modified bCAII, demonstrating the covalent inhibition by 1 as the result of sulfonamide occupying the active site. To our surprise, 2 modified bCAII in a way that caused the enzyme to lose most of its activity despite having an unoccupied active site. This could be attributed to the fact that ~64% of His63 is modified after the bCAII labeling reaction with 2; His63 plays an important role as a proton-transfer group in the catalytic mechanism of CA.43

Target specific labeling of CA in whole cell lysate.

To evaluate the labeling specificity in a complex mixture, we synthesized LD-TMAc reagent 4 that contains a pendant alkyne moiety (Figure 5a). This functionality can be used as a bio-orthogonal handle to conjugate fluorophores to specific protein(s) onto which the LD-TMAc is attached. To test this possibility, we first evaluated the fidelity of the protein functionalization and subsequent bio-orthogonal conjugation with soluble bCAII. Accordingly, after treating 5 μM of bCAII with 10 μM 4 for 30 min, 25 μM of an azido-Cy3 was added to the mixture for 60 min in the presence of a copper catalyst. MALDI-MS of the reaction mixture after each step indicates multi-site modification of bCAII with 4 and the corresponding shift in molecular weight following the copper-catalyzed conjugation of Cy3 (Figure 5b). For specific labeling in a complex mixture, 2 μM of bCAII in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell lysate was sequentially treated with 4 and azido-Cy3. The product mixture was analyzed using SDS-PAGE and in-gel fluorescence (Figure 5c). With 5 μM probe 4, there is a single fluorescent band at ~30 kDa that corresponds to bCAII, with no other discernible fluorescent bands, which demonstrates the target specificity of 4 at this concentration. Fluorescence from the CA band intensity contributes to ~59 % of the total lane fluorescence (Figure S8). Since target-selectivity of the LD-TMAcs is the result of an increase in the concentration of the warhead locally around the ligand bound, a global increase in the probe concentration leads to non-selective labeling. As the probe concentration increases from 5 μM to 15 μM more bands start to appear and background fluorescence increases as well as CA band fluorescence. Therefore, it is essential to optimize the probe concentration for target-selective labeling. At 10 μM and 15 μM probe 4 concentrations, background and CA band fluorescence increases about the same rate with CA band fluorescence contributing to ~60% and 57% of the total lane fluorescence respectively. No fluorescence is observed in the gel in control experiments, i.e., in the absence of 4 or of azido-Cy3. In the presence of 20 μM competitive inhibitor EZA, total lane fluorescence is just about half of lane # 4 with no discernible bands. To illustrate that a complex mixture of proteins is present in the cell lysate, Coomassie staining of the same gel was carried out, which shows all the protein bands in the cell lysate (Figure 5d). Together, these results demonstrate that the labeling is ligand-directed and can be achieved specifically in the target protein even in a complex mixture such as the cell lysate.

Figure 5.

Target specific CA labeling of LD-TMAc in whole cell lysate. (a) Structure of alkyne LD-TMAc reagent 4. (b) MALDI-TOF MS of 5 μM bCAII after sequential labeling with 10 μM 4 (30 min) and copper catalyzed Cy3 click (60 min) reactions, compared to unmodified control bCAII. Reaction conditions: PBS buffer, pH 7.4, 37 °C (c) SDS-PAGE in-gel fluorescence analysis of 2 μM bCAII labeling with 4 (30 min) and Cu-catalyzed Cy3 click reaction (60 min) in 750 ug/mL HEK cell lysate in PBS buffer, pH 7.4, 37 °C and (d) Coomassie staining. *, 4 labeled bCAII (+ 235 Da); *, Cy3 labeled bCAII (+ ~700 Da);

Live cell labeling of membrane CA.

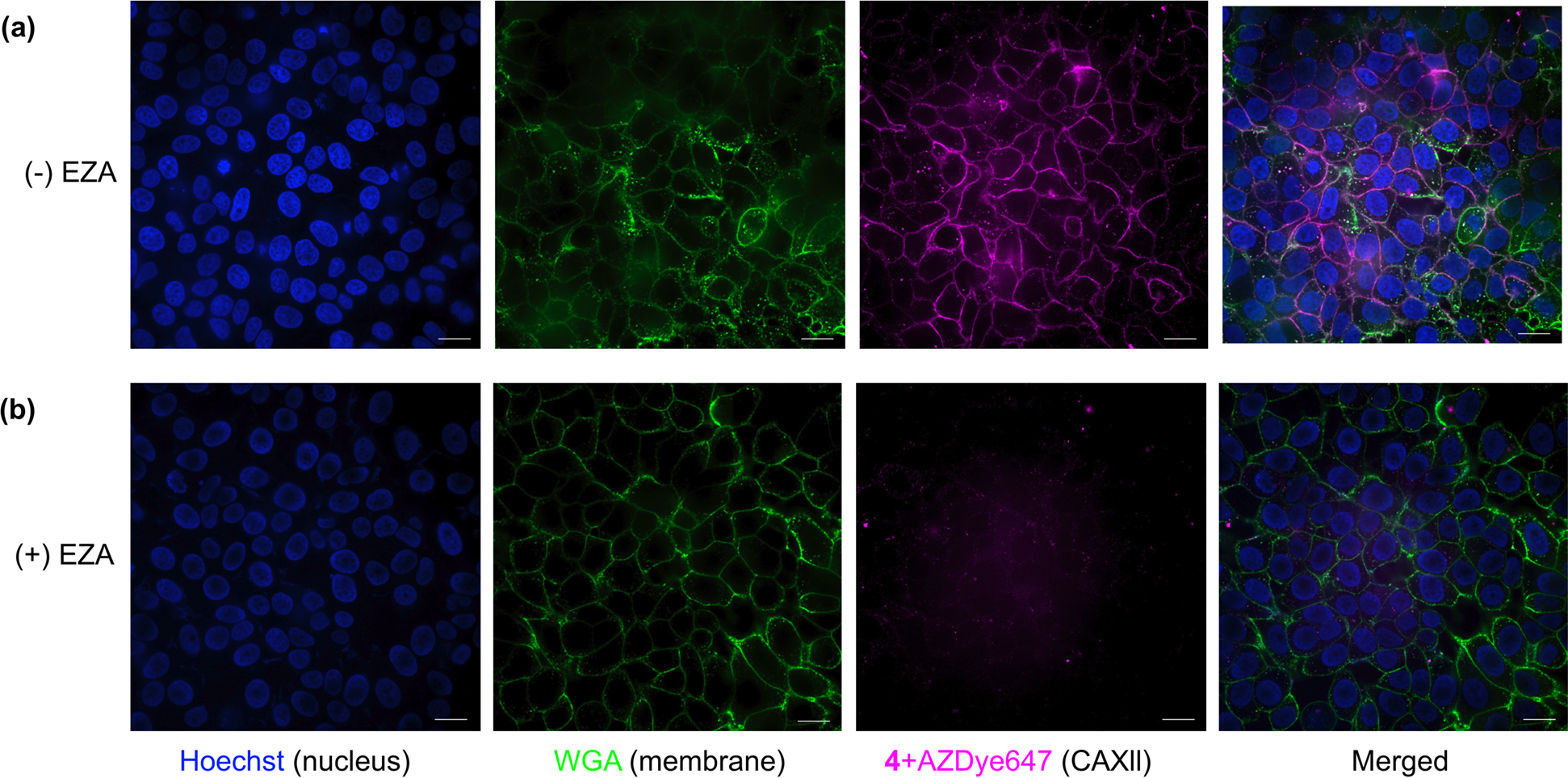

Following the demonstration of labeling in cell lysates, we investigated the possibility of using LD-TMAcs to label membrane proteins in live cells. For this purpose, MCF-7 cells that are known to have membrane-bound human carbonic anhydrase XII (hCAXII) were used. Cells were cultured and treated with 4 (1 μM) for 30 min in serum-free media. Then, a bio-orthogonal click reaction was performed with AZDye647 for 10 min, followed by incubation with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) for membrane staining. Hoechst was used to stain the nucleus prior to imaging. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images show that the cellular membrane is labeled with AZDye647, as discerned by the overlap in fluorescence with WGA fluorescence (Figure 6a). To further demonstrate that the membrane labeling is indeed due to the ligand-directed reaction with the membrane CA, protein labeling reactions were repeated on cells pre-incubated with 100 μM competitive inhibitor EZA, and no AZDye647 fluorescence was observed (Figure 6b). The presence of 100 μM EZA competitively inhibits CA binding and therefore labeling by 1 μM probe 4. The complete absence of AZDye647 fluorescence in Figure 6b shows that there is no CA labeling by probe 4, and there is no protein labeling with all other proteins as well. Therefore, these results show that AZDye647 fluorescence in Figure 6a is the result of target-selective CA labeling by probe 4.

Figure 6.

CLSM images showing the target-specific labeling of CA XII with probe 4 (1 μM) in MCF7 cells in the absence (a) and presence (b) of EZA (100 μM). Fluorescence images of Hoechst, Wheat germ Agglutinin (WGA), 4 + AZDye 647, and their merged images are displayed from left to right of each panel, respectively. Scale bar: 20 μm.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have developed fast and efficient LD-TMAc probes for target specific protein labeling. We show here that: (i) unlike previously reported ligand directed methods, the highly reactive nature of LD-TMAcs and the resultant ability to react with a diverse set of residues allow labeling of multiple residues around the binding pocket; (ii) strategic placement of the ligand moiety relative to the leaving group of the TMAc functionality determines whether the molecule acts as a covalent inhibitor or a multi-site labeling reagent; (iii) the modular design of the LD-TMAcs allows us to fine-tune their reaction kinetics; (iv) the labeling site is primarily determined by conformational accessibility and proximity of the reactive warhead in the bound state; (v) the specificity of LD-TMAc based labeling strategy is translated even in a complex mixture, such as in cell lysates; and (vi) the approach can be used to label specific membrane proteins in live cells.

Ligand-directed protein modification approaches have been used in target identification of bioactive compounds.44–49 Relaxing stringent amino acid selectivity of this strategy expands their applicability to a much broader range of proteins. Overall, we envision LD-TMAc will expand the repertoire of ligand-directed labeling approaches in a variety of applications, including in target identification, understanding of protein binding sites and investigation of membrane proteins.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grant R35 GM136395 to ST R35 GM145272 to RWV. The authors wish to thank the UMass Amherst Institute of Applied Life Sciences Mass Spectrometry Core Facility (RRID:SCR_019063) for access to the Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer, which was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant S10OD010645. We thank UMass Amherst Institute of Applied Life Sciences Mass Spectrometry Core Facility staff Dr. Stephen Eyles and Dr. Cedric Bobst. We thank UMass Amherst Institute of Applied Life Sciences Light Microscopy Facility staff Dr. James Chambers and Maaya Ikeda.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information available. Materials and instrumentation; Covalent labeling and proteolytic digestion methods for LC-MS/MS; Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method; Synthetic procedures for compounds 1 to 6; ESI-MS of intact protein labeling; MALDI-MS of protein labeling in presence of EZA; MS/MS spectrum of Ser171/Thr172 labeling; Table of ions on Figure 4b MS-MS spectrum; LD-TMAc 3 superimposed bCAll structure; SASA on bCAII; Table of control TMAc targeted residues; Fluorescence quantification of Figure 5c; Tandem mass spectra of the peptide modifications; 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of the compounds synthesized.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The raw mass spectrometric data can be accessed in Massive (MassIVE MSV000091614).

REFERENCES

- (1).Leitner A A Review of the Role of Chemical Modification Methods in Contemporary Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics Research. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2018, 1000, 2–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gygi SP; Beate R; Gerber SA; Turecek F; Gelb MH; Aebersold R Quantitative Analysis of Complex Protein Mixtures Using Isotope-Coded Affinity Tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 994–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zhang Y; Zhang C; Jiang H; Yang P; Lu H Fishing the PTM Proteome with Chemical Approaches Using Functional Solid Phases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8260–8287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Tsukiji S; Hamachi I Ligand-Directed Tosyl Chemistry for in Situ Native Protein Labeling and Engineering in Living Systems: From Basic Properties to Applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Liu B; Ejaz W; Gong S; Kurbanov M; Canakci M; Anson F; Thayumanavan S Engineered Interactions with Mesoporous Silica Facilitate Intracellular Delivery of Proteins and Gene Editing. Nano Lett. 2020, 20 (5), 4014–4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Tamura T; Hamachi I Chemical Biology Tools for Imaging-Based Analysis of Organelle Membranes and Lipids. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 70, 102182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Tamura T; Hamachi I Chemistry for Covalent Modification of Endogenous/Native Proteins: From Test Tubes to Complex Biological Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 141, 2782–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sandanaraj BS; Reddy MM; Bhandari PJ; Kumar S; Aswal VK Rational Design of Supramolecular Dynamic Protein Assemblies by Using a Micelle-Assisted Activity-Based Protein-Labeling Technology. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24 (60), 16085–16096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Shiraiwa K; Cheng R; Nonaka H; Tamura T; Hamachi I Chemical Tools for Endogenous Protein Labeling and Profiling. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27 (8), 970–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Purushottam L; Adusumalli SR; Singh U; Unnikrishnan VB; Rawale DG; Gujrati M; Mishra RK; Rai V Single-Site Glycine-Specific Labeling of Proteins. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Reddy NC; Molla R; Joshi PN; Sajeev TK; Basu I; Kawadkar J; Kalra N; Mishra RK; Chakrabarty S; Shukla S; et al. Traceless Cysteine-Linchpin Enables Precision Engineering of Lysine in Native Proteins. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Matos MJ; Oliveira BL; Martínez-Sáez N; Guerreiro A; Cal PMSD; Bertoldo J; Maneiro M; Perkins E; Howard J; Deery MJ; et al. Chemo- and Regioselective Lysine Modification on Native Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (11), 4004–4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Istrate A; Geeson MB; Navo CD; Sousa BB; Marques MC; Taylor RJ; Journeaux T; Oehler SR; Mortensen MR; Deery MJ; et al. Platform for Orthogonal N-Cysteine-Specific Protein Modification Enabled by Cyclopropenone Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144 (23), 10396–10406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lang K; Chin JW Cellular Incorporation of Unnatural Amino Acids and Bioorthogonal Labeling of Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (9), 4764–4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sletten EM; Bertozzi CR Bioorthogonal Chemistry: Fishing for Selectivity in a Sea of Functionality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48 (38), 6974–6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Herner A; Marjanovic J; Lewandowski TM; Marin V; Patterson M; Miesbauer L; Ready D; Williams J; Vasudevan A; Lin Q 2-Aryl-5-Carboxytetrazole as a New Photoaffinity Label for Drug Target Identification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (44), 14609–14615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Tsukiji S; Miyagawa M; Takaoka Y; Tamura T; Hamachi I Ligand-Directed Tosyl Chemistry for Protein Labeling in Vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5 (5), 341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Fujishima SH; Yasui R; Miki T; Ojida A; Hamachi I Ligand-Directed Acyl Imidazole Chemistry for Labeling of Membrane-Bound Proteins on Live Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (9), 3961–3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Matsuo K; Nishikawa Y; Masuda M; Hamachi I Live-Cell Protein Sulfonylation Based on Proximity-Driven N-Sulfonyl Pyridone Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (3), 659–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Tamura T; Ueda T; Goto T; Tsukidate T; Shapira Y; Nishikawa Y; Fujisawa A; Hamachi I Rapid Labelling and Covalent Inhibition of Intracellular Native Proteins Using Ligand-Directed N-Acyl-N-Alkyl Sulfonamide. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chen G; Heim A; Riether D; Yee D; Milgrom Y; Gawinowicz MA; Sames D Reactivity of Functional Groups on the Protein Surface: Development of Epoxide Probes for Protein Labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (27), 8130–8133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Reddi RN; Resnick E; Rogel A; Rao BV; Gabizon R; Goldenberg K; Gurwicz N; Zaidman D; Plotnikov A; Barr H; et al. Tunable Methacrylamides for Covalent Ligand Directed Release Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (13), 4979–4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Reddi RN; Rogel A; Resnick E; Gabizon R; Prasad PK; Gurwicz N; Barr H; Shulman Z; London N Site-Specific Labeling of Endogenous Proteins Using CoLDR Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (48), 20095–20108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Matsuo K; Kioi Y; Yasui R; Takaoka Y; Miki T; Fujishima S; Hamachi I One-Step Construction of Caged Carbonic Anhydrase I Using a Ligand-Directed Acyl Imidazole-Based Protein Labeling Method. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4 (6), 2573–2580. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Miki T; Fujishima SH; Komatsu K; Kuwata K; Kiyonaka S; Hamachi I LDAI-Based Chemical Labeling of Intact Membrane Proteins and Its Pulse-Chase Analysis under Live Cell Conditions. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21 (8), 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Tamura T; Tsukiji S; Hamachi I Native FKBP12 Engineering by Ligand-Directed Tosyl Chemistry: Labeling Properties and Application to Photo-Cross-Linking of Protein Complexes in Vitro and in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (4), 2216–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhuang J; Zhao B; Meng X; Schiffman JD; Perry SL; Vachet RW; Thayumanavan S A Programmable Chemical Switch Based on Triggerable Michael Acceptors. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (8), 2103–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhao B; Zhuang J; Xu M; Liu T; Limpikirati P; Thayumanavan S; Vachet RW Covalent Labeling with an α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Scaffold for Studying Protein Structure and Interactions by Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92 (9), 6637–6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Limpikirati P; Liu T; Vachet RW Covalent Labeling-Mass Spectrometry with Non-Specific Reagents for Studying Protein Structure and Interactions. Methods 2018, 144, 79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Krishnamurthy VM; Kaufman GK; Urbach AR; Gitlin I; Gudiksen KL; Weibel DB; Whitesides GM Carbonic Anhydrase as a Model for Biophysical and Physical-Organic Studies of Proteins and Protein-Ligand Binding. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108 (3), 946–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).King RW; Burgen ASV Kinetic Aspects of Structure-Activity Relations: The Binding of Sulphonamides by Carbonic Anhydrase. Proc. Soc. Lond. B. 1976, 193 (1111), 107–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kernohan JC Fluorescence Technique for Studying the Binding of Sulphonamide and Other Inhibitors to Carbonic Anhydrase. Biochem. J. 1970, 120 (4), 26P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kitz R; Wilson IB Esters of Methanesulfonic Acid as Irreversible Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 1962, 237, 3245–3249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Fraczkiewicz R; Braun W Exact and Efficient Analytical Calculation of the Accessible Surface Areas and Their Gradients for Macromolecules. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19 (3), 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Yip GMS; Chen ZW; Edge CJ; Smith EH; Dickinson R; Hohenester E; Townsend RR; Fuchs K; Sieghart W; Evers AS; et al. A Propofol Binding Site on Mammalian GABA A Receptors Identified by Photolabeling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9 (11), 715–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kashiwayama Y; Tomohiro T; Narita K; Suzumura M; Glumoff T; Hiltunen JK; van Veldhoven PP; Hatanaka Y; Imanaka T Identification of a Substrate-Binding Site in a Peroxisomal β-Oxidation Enzyme by Photoaffinity Labeling with a Novel Palmitoyl Derivative. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285 (34), 26315–26325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Erlanson DA; Wells JA; Braisted AC Tethering: Fragment-Based Drug Discovery. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2004, 33, 199–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hardy JA; Wells JA Searching for New Allosteric Sites in Enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004, 14 (6), 706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lu S; Ji M; Ni D; Zhang J Discovery of Hidden Allosteric Sites as Novel Targets for Allosteric Drug Design. Drug Discov. Today 2018, 23 (2), 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Smith E; Collins I Photoaffinity Labeling in Target- and Binding-Site Identification. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7 (2), 159–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Flaxman HA; Miyamoto DK; Woo CM Small Molecule Interactome Mapping by Photo-Affinity Labeling (SIM-PAL) to Identify Binding Sites of Small Molecules on a Proteome-Wide Scale. Curr. Protoc. Chem. Biol. 2019, 11 (4), e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).West A. v.; Woo CM Photoaffinity Labeling Chemistries Used to Map Biomolecular Interactions. Isr. J. Chem. 2022, e202200081. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Tu C; Silverman DN; Forsman C; Jonsson BH; Lindskog S Role of Histidine 64 in the Catalytic Mechanism of Human Carbonic Anhydrase II Studied with a Site-Specific Mutant. Biochemistry 1989, 28 (19), 7913–7918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ziegler S; Pries V; Hedberg C; Waldmann H Target Identification for Small Bioactive Molecules: Finding the Needle in the Haystack. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (10), 2744–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Takahashi M; Kawamura A; Kato N; Nishi T; Hamachi I; Ohkanda J Protein-Protein Interactions Phosphopeptide-Dependent Labeling of 14–3-3 z Proteins by Fusicoccin-Based Fluorescent Probes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51 (2), 509–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Yamaura K; Kuwata K; Tamura T; Kioi Y; Takaoka Y; Kiyonaka S; Hamachi I Live Cell Off-Target Identification of Lapatinib Using Ligand-Directed Tosyl Chemistry. Chem. Comm. 2014, pp 14097–14100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Hughes CC; Yang YL; Liu WT; Dorrestein PC; la Clair JJ; Fenical W Marinopyrrole A Target Elucidation by Acyl Dye Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (34), 12094–12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Ha J; Park H; Park J; Park SB Recent Advances in Identifying Protein Targets in Drug Discovery. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021, 28 (3), 394–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Chen YC; Backus KM; Merkulova M; Yang C; Brown D; Cravatt BF; Zhang C Covalent Modulators of the Vacuolar ATPase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (2), 639–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw mass spectrometric data can be accessed in Massive (MassIVE MSV000091614).