Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a multi-organ systemic disease that presents with several clinical manifestations, and patients can develop neurologic complications. Neurosarcoidosis may be life-threatening; therefore, early recognition and treatment are key. Here, we present a case of a 55-year-old African American male who presented with a complaint of dizziness and left-sided weakness; he ultimately received a diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis after elaborate radiographic investigations and bladder mass biopsy. Neurosarcoidosis remains a diagnostic dilemma as it can clinically and radiographically mimic multiple conditions including multiple sclerosis, central nervous system lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Keywords: neoplasm, mimicking, nodular leptomeningeal enhancement, bladder mass, neurosarcoidosis

Introduction

Neurosarcoidosis is a challenging medical condition where up to 70% of patients present with neurological manifestations rather than already having a known systemic diagnosis [1]. It is difficult to diagnose as the disease can present in many different ways [2]. The diagnosis is usually one of exclusion as it often masquerades as other disorders, at times creating a lengthy differential and complicated diagnosis [3]. There is no cure, and most patients require long-term treatment with corticosteroids.

This case was previously presented as a poster at the Florida Society of Rheumatology Annual Fellow Poster Presentation on July 09, 2022.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old African American male, with a medical history of substance use, cerebrovascular accident, hepatitis B, recently diagnosed with right lower extremity deep venous thrombosis on anticoagulation presented to the hospital with complaints of dizziness, blurry vision and left-sided weakness of one-day duration. Of note, the patient had had multiple emergency department visits within the past month for similar left-sided leg pain and falls. He had been treated for cellulitis and pain. This time computed tomography (CT) of the brain was ordered and revealed large areas of white matter hypodensities in bifrontal lobes as well as small areas of cortical hypodensities in the right anterioinferior frontal lobe (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CT scan of the brain (axial view), on arrival, demonstrating large areas of white matter hypodensities in the bifrontal lobes as well as small areas of cortical hypodensities in the right anteroinferior frontal lobe (arrows).

This was initially concerning for acute infarct versus subacute post-traumatic changes. Other possible differentials were reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy or neoplastic process given the local mass effect. Neurological examination was non-focal and cranial nerves II-XII were intact. A painful range of motion was noted in the lower extremity; however, muscle strength was noted to be 5/5. Additional findings on the physical examination included bilateral lower extremity edema left more than right, oral thrush and right axillary lymphadenopathy. The stroke protocol was initiated, and the patient was admitted to the hospital. Neurology and Hematology Oncology services were consulted for further evaluation.

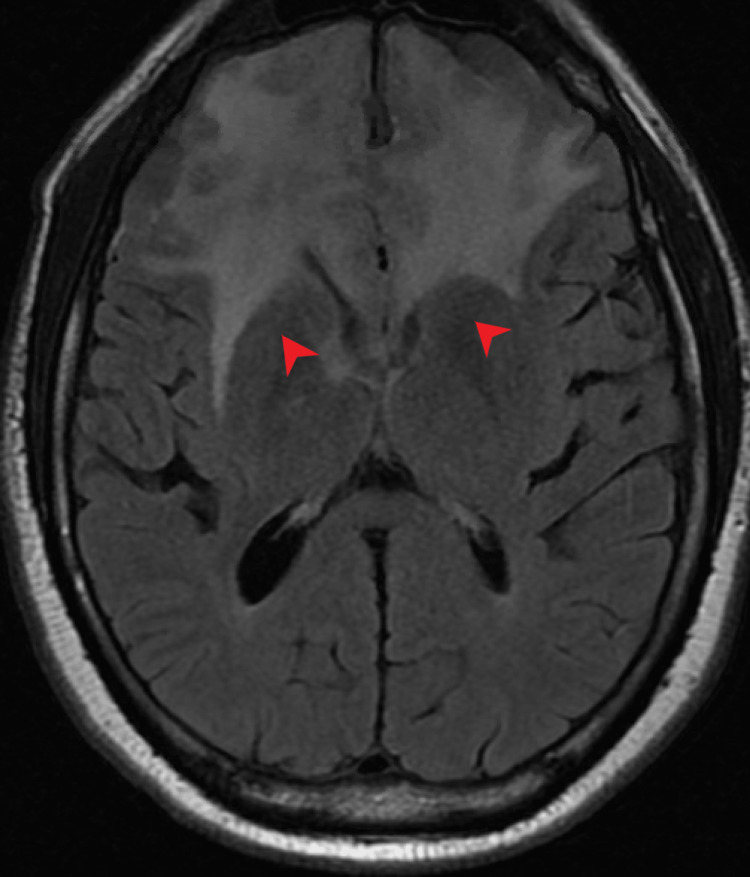

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with contrast revealed extensive enhancing dural nodularity along bilateral frontal convexities and anterior falx associated with extensive nodular leptomeningeal enhancement along the bilateral frontal lobes, suprasellar cistern, right sylvian fissure, and right basal ganglia with associated extensive bilateral frontal vasogenic edema and mass effect on lateral ventricles (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 2. Axial T1-weighted MRI of the brain with contrast showing extensive enhancing dural nodularity along bilateral frontal convexities and anterior falx (red arrow).

Figure 3. Axial T1-weighted MRI of the brain with contrast revealing extensive nodular leptomeningeal enhancement along the bilateral frontal lobes, suprasellar cistern, right Sylvian fissure, and right basal ganglia with associated extensive vasogenic edema extending to the lateral ventricles (red arrows).

The differentials were narrowed down to central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma versus neurosarcoidosis. Due to concerns of CNS lymphoma, steroids were initially withheld pending cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. CT of the chest without contrast was done and revealed sub-centimeter mediastinal, bilateral hilar, and right axillary lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). A core needle biopsy of the largest axillary lymph node was performed that returned as benign and reactive. There was an insufficient sample for flow cytometry.

Figure 4. Axial view of chest CT without contrast showing calcified right hilar adenopathy (arrow).

CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was ordered for further assessment of lymphadenopathy that discovered a 2.6-cm bladder wall tumor concerning for neoplasm. There was also bilateral iliac chain and retroperitoneal adenopathy suspicious for metastatic disease. The patient underwent transurethral resection of the bladder tumor. The pathology revealed noncaseating granulomas (Figures 5, 6).

Figure 5. Pathology of the bladder mass showing noncaseating granulomas (arrow).

Figure 6. Pathology of the bladder mass showing noncaseating granulomas (arrow).

On hospital day 7, the patient developed new-onset left-sided weakness including reduced grip strength and left-sided facial droop. Brain imaging revealed persistent vasogenic edema. After a discussion with all the specialists, the decision was made to initiate steroids prior to CSF analysis. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) stains from the axillary lymph node as well as the bladder tumor returned negative. At this time, a lumbar puncture was performed that was negative for infection or malignancy. The CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were within normal limits (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1. Infectious workup.

PCR: polymerase chain reaction; Ab: antibody; Ag: antigen; EBV: Ebstein-Barr virus; CMV: cytomegalovirus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus

| Laboratory test | Result | Reference values |

| Treponemal-specific enzyme immunoassay | <0.2 | 0.0-0.9 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae DNA amplification | Negative | Negative |

| Chlamydia trachomatis DNA amplification | Negative | Negative |

| EBV DNA (PCR) | Negative | Negative |

| CMV DNA qual (PCR) | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis Bs Ag | Positive | Negative |

| Hepatitis Bs Ab | 0 mIU/mL | >12.0 mIU/mL |

| Hepatitis Bc IgM Ab | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis Be Ag | Positive | Negative |

| HIV 1 and 2 Ag/Ab | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

Table 2. CSF and serum analysis.

WBC: white blood cell; RBC: red blood cell; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; ANA: antinuclear antibody

*IgG index was 0.4 (normal reference value 0.0-0.7).

| CSF analysis | Result | Reference values | |

| Appearance | Clear | Clear | |

| WBC | 3 | 0-10/CMM | |

| RBC | 0 | 0-3/CMM | |

| Neutrophils % | 0 | 0-6% | |

| Lymphocytes % | 55 | 40-80% | |

| Monocytes % | 45 | 15-45% | |

| Glucose | 66 | 40-70 mg/dL | |

| Total protein | 62.5 | 15-45 mg/dL | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme | <1.5 | 0.0-3.1 U/L | |

| IgG* | 7.7 | 0.0-10.3 | |

| Serum analysis | |||

| IgG (serum) | 2535 | 603-1613 mg/dL | |

| IgA (serum) | 104.1 | 70-400 mg/dL | |

| IgM (serum) | <25 | 40-230 mg/dL | |

| IgE (serum) | 159 | <100 IU/mL | |

| Free kappa light chain, quantitative | 208.7 | 3.3-19.4 mg/L | |

| Free lambda light chain, quantitative | 11.2 | 5.7-26.3 mg/L | |

| ANA screen | Negative | Negative | |

The patient clinically improved after the initiation of steroids and a repeat MRI scan of the brain showed moderate interval improvement with persistent leptomeningeal enhancement and resolution of the previously present mass effect on frontal horns. The diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis was favored given bilateral hilar adenopathy on the chest CT scan, improvement in imaging findings following steroid administration, and noncaseating granulomas found in the bladder lesion. Neurosurgery and Oncology did not favor brain biopsy at this time. The patient was discharged on dexamethasone with instructions to follow up with Rheumatology as an outpatient.

Discussion

Up to 70% of patients with neurosarcoidosis present to medical care with their neurological manifestations rather than already having a known systemic diagnosis [1]. As the disease can present in many different ways without biopsy evidence, solitary nervous-system sarcoidosis is difficult to diagnose [2]. The diagnosis is usually one of exclusion as it often masquerades as other disorders, at times creating a lengthy differential and complicated diagnosis [3]. There is no cure and most patients require long-term treatment with corticosteroids.

Neurosarcoidosis exhibits variable degrees of infiltration in the brain resulting in focal or disseminated nodules or plaques affecting particularly the basal meninges. The granulomatous infiltration may extend into the cortex or white matter causing parenchymal lesions [4-8]. This pattern seen in imaging is generally indistinguishable from that seen with tuberculosis or lymphoma with leptomeningeal involvement [5]. Beside parenchymal lesions and meningeal masses, hydrocephalus may also be seen with MRI.

In 2018, the Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group developed a diagnostic approach for neurosarcoidosis, adapted from 1999, that described possible, probable and definite neurosarcoidosis [9-10]. Alternative diagnoses like infection or malignancy must be ruled out and obtaining a tissue biopsy is recommended. A non-neural pathology confirming systemic sarcoidosis would support a diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis, whereas having a neural tissue showing noncaseating granulomas gives a definite diagnosis. If histology is not obtained, having at least two indirect indicators from a gallium scan, chest imaging, and serum ACE is accepted as the confirmation of systemic sarcoidosis. In recent years, F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scans have become an important tool to evaluate other sites of involvement in neurosarcoidosis and select more surgically accessible sites for biopsy [11]. If the clinical picture is suggestive of neurosarcoidosis but alternate diagnoses have not been ruled out, then a diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis is thought to be possible (Table 3 and Figure 7).

Table 3. Diagnostic criteria.

| Diagnosis | Criteria |

| Probable | Non-neural pathology confirming systemic sarcoidosis. |

| Possible | The clinical picture is suggestive of neurosarcoidosis, but alternate diagnoses have not been ruled out and there is no systemic confirmation of sarcoidosis. |

| Definitive | Neural tissue showing noncaseating granulomas. |

Figure 7. Diagnostic algorithm .

CNS: central nervous system; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid

There are several conditions that neurosarcoidosis can mimic. One of them is multiple sclerosis (MS), given the radiologic findings on MRI besides relapsing-remitting course of the disease as well as dissemination of the MRI lesions in space and time. Cognitive and neuropsychiatric presentation in the context of parenchymal brain lesions argues against MS, and certainly, coexisting peripheral nervous system involvement or myopathies are distinctive features of neurosarcoidosis [10]. Additionally, neurosarcoidosis can present with weakness or dysarthria resembling a stroke. Transient ischemic attacks and ischemic stroke due to neurosarcoidosis have been reported [12]. Neurosarcoidosis may coexist with multiple myeloma or be confused with neuropathies secondary to monoclonal proliferation or paraproteinemic neuropathy. The enhancing parenchymal lesions may also be mistaken for neoplasms; however, the lack of central necrosis in histology distinguishes neurosarcoidosis from malignancy. CNS lymphoma is another possible differential diagnosis to keep in mind. There has been a case reported on neurolymphomatosis mimicking neurosarcoidosis. Neurolymphomatosis represents a unique subtype of extranodal lymphoma with localized invasion of cranial or peripheral nerves reported in patients with large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [13].

This case is not only a diagnostic challenge but also a therapeutic one due to social constraints. Patient's comorbidities, in addition to homelessness, made it challenging to ensure follow-up with various specialists. Several works of literature have shown sarcoidosis to be a disease that affects those with health disparities [14-15]. According to Sharp et al., “worse dyspnea, lower health-related quality of life, and higher rates of mortality and hospitalization are more common among those who are black, female, or of low socioeconomic status” [14]. Low socioeconomic status is also associated with increased stress, and chronic stress has been shown to impact immune function. A study done by De Vries and Drent showed a direct relationship between stress and sarcoidosis [16]. Also, the economic burden was found to be higher during the first year after diagnosis [17-18].

Conclusions

Neurosarcoidosis poses a diagnostic challenge as it can imitate other neurological diseases, including CNS lymphoma and multiple sclerosis. In addition, the prognosis of neurosarcoidosis varies, with some recovering completely, while others have a chronically progressing, waxing, and waning course. Moreover, it imposes a significant economic burden on the payer, especially in the first year following diagnosis as patients require several specialist visits to manage sarcoidosis-related comorbidities, making it a therapeutic challenge.

Acknowledgments

No data sets were used except for the review of the medical record. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal’s patient consent policy. Zainab Hanif and Keysha Gonzalez contributed equally to the work and should be considered co-first authors.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Neurosarcoidosis: clinical review of a disorder with challenging inpatient presentations and diagnostic considerations. Hoyle JC, Jablonski C, Newton HB. Neurohospitalist. 2014;4:94–101. doi: 10.1177/1941874413519447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, Sharma OP. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:397–407. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00805-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neurosarcoidosis and the complexity in its differential diagnoses: a review. Spiegel DR, Morris K, Rayamajhi U. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22666636/ Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9:10–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Immunohistochemical characterisation and TNF-α expression of the granulomatous infiltration of the brainstem in a case of sudden death due to neurosarcoidosis. D'Errico S, Bello S, Cantatore S, Neri M, Riezzo I, Turillazzi E, Fineschi V. Forensic Sci Int. 2011;208:0–5. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imaging manifestations of neurosarcoidosis. Smith JK, Matheus MG, Castillo M. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:289–295. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Germ cell tumors masquerading as central nervous system sarcoidosis. Peeples DM, Stern BJ, Jiji V, Sahni KS. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:554–556. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530170118031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The clinical course of sarcoidosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a large white and black cohort in the United States. Judson MA, Boan AD, Lackland DT. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23461074/ Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neurologic manifestations in sarcoidosis: review of the literature, with a report of 23 cases. Delaney P. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:336–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-3-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Definition and consensus diagnostic criteria for neurosarcoidosis: from the Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group. Stern BJ, Royal W III, Gelfand JM, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1546–1553. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neurosarcoidosis as an MS mimic: the trials and tribulations of making a diagnosis. MacLean HJ, Abdoli M. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4:414–429. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) computed tomography (CT) for the detection of bone, lung, and lymph node metastases in rhabdomyosarcoma. Vaarwerk B, Breunis WB, Haveman LM, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;11:0. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012325.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuro-ophthalmologic signs in the angiitic form of neurosarcoidosis. Caplan L, Corbett J, Goodwin J, Thomas C, Shenker D, Schatz N. Neurology. 1983;33:1130–1135. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.9.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neurolymphomatosis mimicking neurosarcoidosis: a case report. Santos E, Scolding NJ. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socioeconomic determinants and disparities in sarcoidosis. Sharp M, Eakin MN, Drent M. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26:568–573. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortality among African American women with sarcoidosis: data from the Black Women's Health Study. Tukey MH, Berman JS, Boggs DA, White LF, Rosenberg L, Cozier YC. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24071884/ Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013;30:128–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Relationship between perceived stress and sarcoidosis in a Dutch patient population. De Vries J, Drent M. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15127976/ Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Economic burden of sarcoidosis in a commercially-insured population in the United States. Rice JB, White A, Lopez A, et al. J Med Econ. 2017;20:1048–1055. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1351371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Income and other contributors to poor outcomes in U.S. patients with sarcoidosis. Harper LJ, Gerke AK, Wang XF, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:955–964. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1250OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]