Abstract

Accumulating evidence indicates that early and essential events for receptor-like kinase (RLK) function involve both autophosphorylation and substrate phosphorylation. However, the structural and biochemical basis for these events is largely unclear. Here, we used RLK FERONIA (FER) as a model and crystallized its core kinase domain (FER-KD) and two FER-KD mutants (K565R, S525A) in complexes with ATP/ADP and Mg2+ in the unphosphorylated state. Unphosphorylated FER-KD was found to adopt an unexpected active conformation in its crystal structure. Moreover, unphosphorylated FER-KD mutants with reduced (S525A) or no catalytic activity (K565R) also adopt similar active conformations. Biochemical studies revealed that FER-KD is a dual-specificity kinase, and its autophosphorylation is accomplished via an intermolecular mechanism. Further investigations confirmed that initiating substrate phosphorylation requires autophosphorylation of the activation segment on T696, S701, and Y704. This study reveals the structural and biochemical basis for the activation and regulatory mechanism of FER, providing a paradigm for the early steps in RLK signaling initiation.

Key words: FERONIA, active conformation, kinase activity, autophosphorylation, activation

From structural observations of its core kinase domain and related mutants, the receptor-like kinase FERONIA was shown to adopt a phosphorylation-independent active conformation. Subsequent biochemical studies revealed that FERONIA is a dual-specificity kinase whose autophosphorylation is required for efficient substrate phosphorylation. This study provides important insights into receptor-like kinase activation in the early steps of signaling initiation.

Introduction

Receptors localized at the plasma membrane are critical for the adaptation of organisms to different environmental stimuli. The largest family of membrane receptors in animals is the G protein-coupled receptor family, whereas receptor-like kinases (RLKs) constitute the most prominent family of membrane receptors in plants. Arabidopsis has more than 600 RLKs, comprising 2.5% of its protein-encoding genes (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001b). Most RLKs have an extracellular ligand-binding domain (ECD), followed by a single transmembrane helix-containing domain and a relatively well-conserved cytoplasmic kinase domain (CD) (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001a). The general working model is that RLKs sense and recognize ligand molecules through the ECD, induce CD phosphorylation and allosteric activation, and subsequently recruit specific intracellular substrates to initiate downstream signaling (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001b, 2003). The ligand recognition mechanisms of various ECDs have been extensively investigated. For example, the leucine-rich repeat RLK brassinosteroid-insensitive 1 (BRI1) senses growth-promoting brassinosteroids (He et al., 2000), the phytosulfokine receptor recognizes the hormone phytosulfokine (Wang et al., 2015), and the root meristem growth factor receptor perceives the root meristem growth factor peptide (Ou et al., 2016; Song et al., 2016). Studies of CDs have focused mainly on identifying key substrates that mediate the downstream regulatory machinery. For example, cognate substrates have been found for Chitin Elicitor Receptor Kinase 1 (He et al., 2018), Flagellin Sensing 2 (Li et al., 2014; Trda et al., 2015), Brassinosteroid Insensitive 1(Wang and Chory, 2006; Belkhadir and Jaillais, 2015; Nolan et al., 2017; Su et al., 2021), and Clavata1 (Hazak and Hardtke, 2016; Macho and Lozano-Duran, 2019). Despite advances in understanding ECD–ligand and CD–substrate interactions, the specific activation process and subsequent substrate phosphorylation events in the early stages of CD activity remain largely unknown.

FERONIA (FER) belongs to the 17-member Catharantus roseus RLK1-like (CrRLK1L) family of RLKs in Arabidopsis (Lindner et al., 2012). Extensive genetic analyses have demonstrated that FER plays a key role in many physiological processes, including plant immunity, growth, and reproduction (Zhu et al., 2021). RALFs have been shown to act as ligands for FER (Haruta et al., 2014; Stegmann et al., 2017), and the structural basis for this interaction has been elucidated by the crystal structure of RALF23 peptide perception by a heterotypic receptor complex (LLG2–FERECD) (Xiao et al., 2019). FER is a versatile kinase that inhibits pollen tube growth to affect double fertilization (Escobar-Restrepo et al., 2007), suppresses primary root growth in response to the RALF1 peptide (Haruta et al., 2014), promotes cell growth in root hairs and leaves (Zhu et al., 2020), and regulates the immune output of Flagellin Sensing 2 and EF-TU receptor (Stegmann et al., 2017). Interestingly, FER activity levels or signaling outputs vary according to the effects of different RALF members (Franck et al., 2018). For example, RALF1 and RALF23 trigger root growth inhibition, whereas RALF23 represses FER signaling during immune responses (Haruta et al., 2014; Stegmann et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020). Previous studies have suggested that FER functions are complex and varied. The FER CD has been reported to interact with GEF1/4/10, ATL6, eIF4E, RIPK, abscisic acid-insensitive 2 (ABI2), EBP1, MYC2, and GRP7 (Chen et al., 2016; Du et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). FER interacts with RIPK, and they mutually phosphorylate each other to inhibit root growth (Du et al., 2016). FER interacts with ABI2 in the control of plant growth and stress responses (Chen et al., 2016). FER phosphorylates EBP1 to promote its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity (Li et al., 2018). FER phosphorylates and destabilizes MYC2 to downregulate jasmonic acid-mediated host susceptibility (Guo et al., 2018). FER phosphorylates ATL6 to modulate the stability of 14-3-3 proteins in response to the carbon/nitrogen ratio (Xu et al., 2019). FER phosphorylates GRP7 to modulate stress responses and growth (Wang et al., 2020). FER phosphorylates eIF4E1 to regulate protein synthesis (Zhu et al., 2020). Although many CD substrates of FER have been characterized, the role of its kinase activity in signal transduction remains elusive. For example, Kessler et al. (2015) found that the point mutation FER-K565R, which abolished kinase activity, was able to complement the fer (FER null mutant) phenotype during pollen tube (PT) reception, demonstrating that the kinase domain of FER is necessary for PT reception but kinase activity itself is not (Kessler et al., 2015). In line with these results, the defective ovule fertilization caused by a fer-4 mutant was fully complemented in FER-K565R/fer-4, but reduced root responses to RALF1 and RALF1-induced cytoplasmic calcium mobilization were not (Haruta et al., 2018). Another study found that FERK565R has dose-dependent effects on rosette morphology and RALF1-mediated stomatal movements (Chakravorty et al., 2018). These studies are crucial for our understanding of how FER signaling is coordinated in cells, but the molecular mechanisms of FER cytoplasmic activation remain poorly understood.

In this study, we determined the high-resolution crystal structures of the FER kinase domain (FER-KD) and its two mutants (K565R, S525A) and identified an unanticipated active state of RLK formed without detectable phosphorylation. A combination of mass spectrometry and biochemical analyses indicated that FER-KD can be autophosphorylated via an intermolecular mechanism. In addition, FER functions as a dual-specificity kinase, and key residues from its activation segment are essential for FER activation and substrate phosphorylation. Our work not only reveals the biochemical and structural features of FER-KD but also provides a framework for the regulatory mechanism of FER.

Results

Overall structure of the FER-KD

To investigate the activation mechanism of FER kinase, we sought to determine the crystal structure of its intracellular CD. The CD of FER consists of three subdomains: the juxta-membrane domain (JM), the core KD, and the C-terminal tail (CT) (Figure 1A). HHpred (Soding et al., 2005) and Phyre2 (Kelley et al., 2015) analyses revealed that JM and CT are mainly disordered regions. To improve crystallizability, we constructed four protein fragments: FER-CD (residues 469–895), FER-JM-KD (residues 469–816), FER-KD-CT (residues 518–895), and FER-KD (residues 518–816). The kinase activity of wild-type FER proteins is toxic to Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells. The protein fragments were co-expressed with ABI2, as ABI2 directly interacts with and dephosphorylates FER (Chen et al., 2016). After numerous trials, we successfully obtained the crystal structure of FER-KD in complex with ADP and Mg2+ (FER-KD–ADP) at ∼2 Å resolution (Figure 1B; Supplemental Table 1). The complex structure was determined by molecular replacement using Pto kinase in the Pto–AvrPto complex (PDB: 2QKW) as the template (Dong et al., 2009). The crystallographic asymmetric unit comprises two molecules (A and B) (Supplemental Figure 1A). The overall structures of molecules A and B are similar, with a root-mean-square deviation value of 0.429 Å at the Cα position (Cα RMSD) (Supplemental Figure 1B).

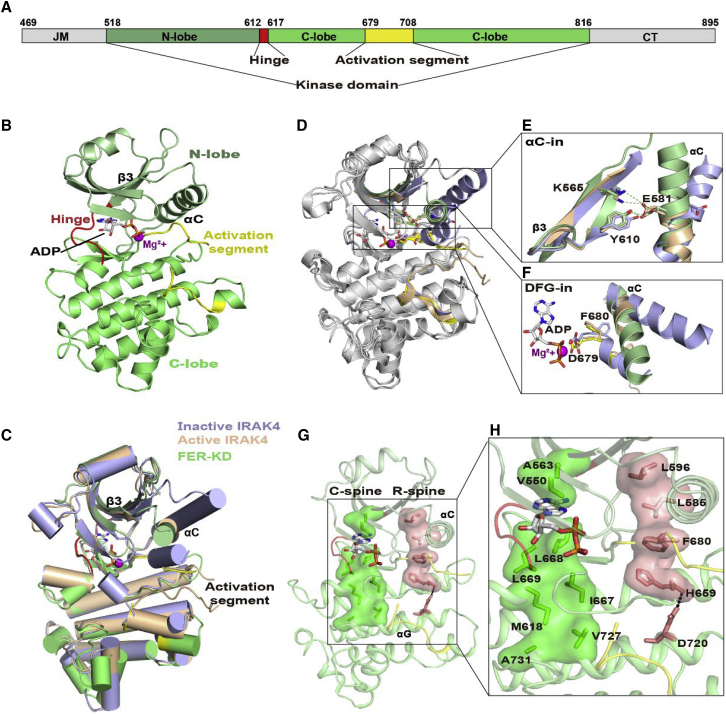

Figure 1.

Overall structure of FER-KD complexed with ADP.

(A) Schematic diagram of the FER fragments from the intracellular domain (FER-CD) in our study. JM, juxta-membrane domain (shown in gray); KD, kinase domain N-lobe is shown in pale green; C-lobe is shown in light green; the overall color is green); AS, activation segment (shown in yellow); CT, C-terminal tail (shown in gray). The hinge is presented in red. Residues located at the domain boundaries are numbered on top of the panel.

(B) The structure of FER-KD, as shown in a cartoon representation. The FER-KD color scheme is the same as that in the schematic diagram in (A). ADP is shown as colored sticks, and Mg2+ ions are indicated by purple spheres.

(C and D) Ribbon structural comparison of FER-KD (green) with active IRAK4 (wheat, PDB: 2OID) and inactive IRAK4 (light blue, PDB: 6EGF) in two views. The ADP and Mg2+ in FER-KD are presented as in (B). The AMP-PNP and ions in IRAK4 are not shown.

(E and F) Detailed comparison of the active sites with αC-in (E) and DFG-in (F). The essential residues are presented as sticks. The hydrogen bonds (between E581 and Y610) and salt bridges (between E581 and K565) in FER-KD and active IRAK4 are presented as green and wheat dashed lines, respectively.

(G and H) C-spine and R-spine in the FER-KD–ADP complex. The C-spine and R-spine are presented in green and salmon surface representations, respectively (G). The C-spine, comprising V550, A563, M618, I667, L668, L669, V727, and A731, is indicated by green sticks. The R-spine, consisting of L585, L596, F680, H659, and D720, is indicated by salmon sticks (H).

Similar to most kinases, FER-KD adopts a typical bilobal fold (Figure 1B). It consists of a smaller N-terminal lobe (N-lobe; residues 518–611) rich in β-strands (β1–β5) and a larger C-terminal lobe(C-lobe; residues 618–816) containing mainly α-helices. These two lobes are connected by a six-residue hinge (residues 612–617), creating a prominent cleft that serves as a “binding pocket” for binding nucleotides and substrates. An ADP bound to a single Mg2+ ion is observed in the deep cleft between the two lobes of FER-KD. Unfortunately, the activation segment (residues 679–708) contains a loop with 15 unmodeled residues that is not observed in the crystal structure, indicating its high flexibility. Except for this segment, the crystal structure of FER-KD is otherwise well defined in the electron density map.

Unphosphorylated FER-KD adopts an αC-in and DFG-in active conformation

Protein kinases adopt either active or inactive conformations, which can be distinguished by characteristic structural features. We used the DALI program to evaluate the conformation of FER-KD by performing a structural similarity search (Holm and Rosenstrom, 2010). This search revealed that the conformation of FER-KD is closely related to the active conformation of human interleukin receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) and the plant receptor kinase BRI1 (Kuglstatter et al., 2007; Bojar et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2019). The Cα RMSDs of FER-KD upon superposition with active and inactive IRAK4 are 0.815 and 1.104 Å, respectively (Figure 1C) (Kuglstatter et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2019). Unlike inactive IRAK4, in which the αC-helix is displaced from the active site (αC-out) and disrupts a salt bridge with an important catalytic function, the αC-helix of FER-KD is in an αC-in conformation, which allows the formation of the critical salt bridge between K565 and E581 (Figure 1C–1E). In addition, E581 establishes a hydrogen bond with the central gatekeeper Y610 (Y956 in BRI1), which is located in and controls the size of a pocket called the “back pocket” (Figure 1E) (Bojar et al., 2014). Like IRAK4, FER-KD has a DFG-in conformation in which the side chain of D679 faces the active site and F680 points to the conformation of the αC-helix (Figure 1F). We also used a more rigorous density-based clustering algorithm (Modi and Dunbrack, 2019) and identified the FER-KD structure to be in a “BLAminus” conformation in “DFGin” (residues 679–681) (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3), which is the most common active kinase state in the PDB. This evidence collectively demonstrates that FER-KD adopts an αC-in and DFG-in active conformation.

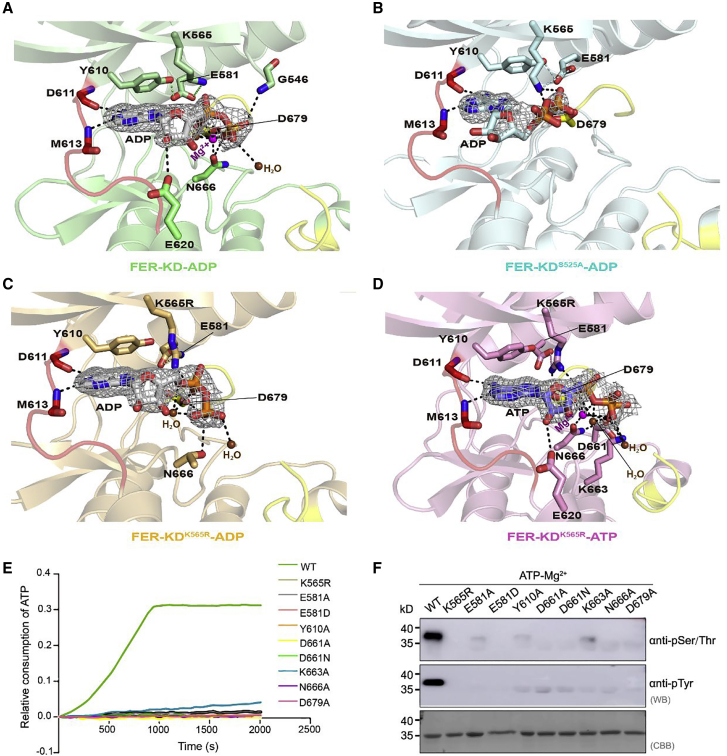

Figure 3.

Analyses of FER nucleotide-binding sites.

(A) Close-up view of the nucleotide-binding site of FER-KD–ADP (green). The E581–K565 salt bridge and E581–Y610 hydrogen bond are connected with green dotted lines, and other hydrogen bond contacts are connected with black dotted lines. The 2Fo-Fc electron density map, contoured at 1.6σ, is shown in gray mesh around the ADP molecule. The Mg2+ ions (purple) and water molecules (brown) are highlighted as spheres, whereas the ADP molecule and residues are represented as colored sticks.

(B–D) Close-up views of the FER-KDS525A–ADP (cyan), FER-KDK565R–ADP (orange), and FER-KDK565R–ATP (pink) complexes in the same orientation and color scheme as (A).

(E) ATPase activity of the nucleotide-binding-associated mutants.

(F) Western blotting analysis of the nucleotide-binding-associated mutants. Specifically, 1 mM unphosphorylated samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ for 30 min at 25°C.

The catalytic spine (C-spine) and the regulatory spine (R-spine) of protein kinases were studied to examine the active conformation of FER-KD. The two functional protein kinase “spines” are usually parted in the inactive conformation, but they assemble during kinase activation, as characterized by the coordinated movement of two lobes (N-lobe and C-lobe) to promote the binding of ATP and substrate (Kornev et al., 2008). FER-KD does exhibit this characteristic assembly of the two spines (Figure 1G). The C-spine of FER-KD consists of two residues from the N-lobe (V550 and A563) and six residues from the C-lobe (M618, I667, L668, L669, V727, and A731) (Figure 1H). The V550, A563, and L668 side chains form a hydrophobic pocket that accommodates the adenine ring of ADP, allowing ADP to connect the two lobes. Likewise, the R-spine consists of HRD-His (H659 in FER-KD), DFG Phe (F680), αC-helix Glu+4 (L585), a residue in the loop before chain β4 (L596), and a conserved remnant of the αG-helix (D720) (Figure 1H).

Consistent with the co-expression of FER-KD with ABI2, careful examination of the crystal structure revealed no phosphorylation of FER-KD. To further confirm this point, we detected the phosphorylation state of the FER-KD proteins using anti-phosphoserine/phosphothreonine and anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies, and no phosphorylation was detected (Figure 2A). Thus, FER-KD appears to adopt an active conformation without being phosphorylated.

Figure 2.

Structural and biochemical characteristics of FER-KD and its mutants.

(A) Western blotting analysis of the phosphorylation state of FER-KD, FER-KDS525A, and FER-KDK565R. CK represents 1 mM FER-KD samples incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for 30 min.

(B) ATPase activity of FER-KD, FER-KDS525A, and FER-KDK565R.

(C) Ribbon structural comparison of the FER-KD–ADP (green), FER-KDS525A–ADP (cyan), FER-KDK565R–ADP (orange), and FER-KDK565R–ATP (pink) complexes, which gives Cα RMSDs of 0.230, 0.280, and 0.187 Å, respectively.

FER-KD mutants adopt similar active conformations without being phosphorylated

Earlier studies have shown that K565 is an essential catalytic residue, and replacing this residue with arginine (R) in FER-KD (mFER-KD) leads to a dramatic decrease in kinase activity (Haruta et al., 2018). By ATPase activity measurements, we confirmed the essential role of K565 in ATP binding and subsequent FER activation/autophosphorylation (Figure 2B). Therefore, we used K565R as an entry point to confirm our previous conclusion that phosphorylation is not necessary for maintaining the active form of FER. For a more comprehensive view of FER activation, we also chose another FER kinase mutant, S525A, which has partially reduced activity (Figure 2B), for subsequent analysis of FER activation state. Purified FER-KDS525A (which was co-expressed with ABI2) and FER-KDK565R were both confirmed to undergo no phosphorylation in E. coli (Figure 2A).

After performing crystallization and diffraction experiments, the crystal structures of the K565R mutant in complex with ADP/ATP (FER-KDK565R–ADP/ATP) and the S525A mutant in complex with ADP (FER-KDS525A–ADP) were determined to resolutions of 1.93, 1.97, and 2.23 Å, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). Remarkably, both FER-KD mutants adopted an active conformation (Figure 2C; Supplemental Figure 2). Overall structural comparison of FER-KDK565R–ADP, FER-KDK565R–ATP, and FER-KDS525A–ADP with the FER-KD–ADP complex gives Cα RMSD values of 0.280, 0.187, and 0.230 Å, respectively (Figure 2C). In particular, similar to the structure of FER-KD, the mutations still form salt bridges between K/R565 and E581 (αC-in), adopt a DFG-in conformation, and form the C-spine and R-spine (Supplemental Figure 2A–2E). The density-based clustering algorithm shows that FER-KDS525A and FER-KDK565R belong to the “BLAminus” type in the “DFGin” state (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). These data indicate that both the K565R and the partially active S525A mutants adopted active forms without phosphorylation.

The FER nucleotide-binding site

Given that ATP binding is required for phosphate transfer in the kinase, we investigated the ATP-binding pocket of FER-KD, FER-KDS525A, and FER-KDK565R in detail. The electron densities clearly show the presence of a molecule of ADP/ATP in the ATP-binding site sandwiched between the N- and C-lobes (Figure 3A–3D).

The adenine ring of ADP/ATP forms hydrogen bonds with the M613 backbone amine and the D611 backbone carbonyl group in the hinge. The overall structure adopts an active conformation, allowing E581 and K/R565 to form a conserved and catalytically essential salt bridge. The mutation of K565 to R565 interferes with hydrogen bond formation between E581 and the conserved gatekeeper Y610, disrupting the “back pocket” (Figure 3C and 3D). The S525A and K565R mutations did not cause overall structural changes, but they elevated the position of ADP/ATP in the binding pocket (formation of hydrogen bonds between K/R and ADP/ATP; Figure 3B–3D). This structural movement would make the γ phosphate group further away from the catalytic residue and the substrate, causing a difference in catalytic efficiency (Figure 2B).

A typical active and phosphorylated protein kinase requires two Mg2+/Mn2+ ions to catalyze the transfer of the phosphate group to the substrate (Jacobsen et al., 2012; Bastidas et al., 2013). A magnesium ion is coordinated by N666 and D679 of the DFG motif (residues 679–681), besides the α- and β-phosphates of the nucleotide. In addition, hydrogen bonds between ATP and K663 and D661 of the protein are used to strengthen nucleotide binding (Figure 3D). Consistent with these structural observations, a conservation analysis of the FER subfamily revealed that these residues of the ATP-binding pocket are well conserved in the FER subfamily (Supplemental Figure 3). To verify whether these residues are required for the kinase activity of FER-KD, we constructed several mutants and measured their ATPase activity and autophosphorylation. In keeping with their essential roles in nucleotide binding, mutations of K565, E581, Y610, D661, K663, N666, and D679 almost completely eliminated the catalytic activity of FER (Figure 3E and 3F).

FER-KD is autophosphorylated via an intermolecular mechanism

To quantitatively characterize the ATPase activity of FER-KD, we performed enzyme-coupled spectrophotometry (Roskoski, 1983). The Km and kcat values were 14.21 ± 2.166 μM and 0.09972 ± 0.004651 s−1, respectively. After conversion, kcat/Km was approximately equal to 0.007 μM−1 s−1, suggesting that FER-KD could effectively hydrolyze ATP and providing evidence for its autophosphorylation (Figure 4A). In vitro time-course experiments were performed to evaluate the autophosphorylation ability of FER-KD. The results showed that FER-KD could completely autophosphorylate within 30 min (Figure 4B), and autophosphorylated FER-KD (pFER-KD) was effectively dephosphorylated by lambda protein phosphatase, a broad-spectrum protein phosphatase (Figure 4C) (Zhuo et al., 1993).

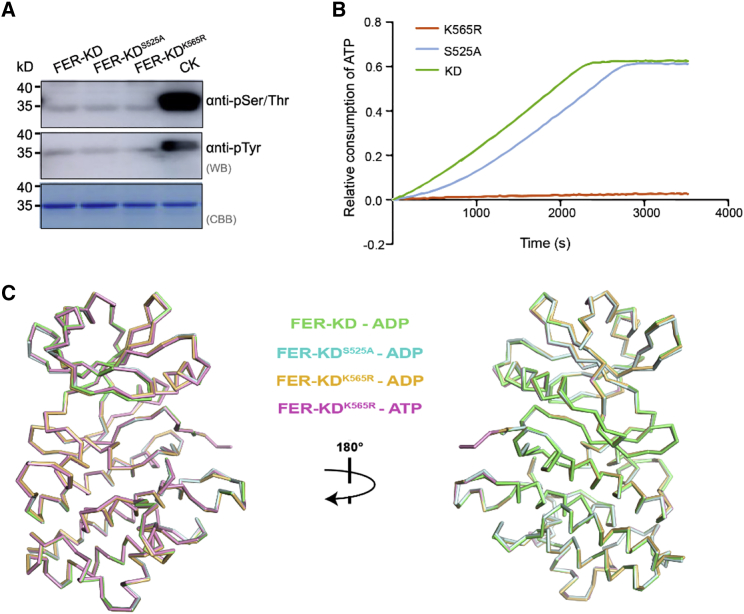

Figure 4.

FER-KD is autophosphorylated via an intermolecular mechanism.

(A) Measurement of kinetic parameters for FER-KD using the NADH-coupled microplate photometric assay. The reaction mixture contained 1 μM wild-type FER-KD and 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, or 100 mM ATP. The solid line represents the best-fit result according to the Michaelis‒Menten equation, with kcat and Km values of 0.10 ± 0.00 s−1 and 14.21 ± 2.17 mM, respectively.

(B) FER-KD time-course autophosphorylation assay. Specifically, 1 mM FER-KD samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for the indicated period.

(C) Phosphorylation states of FER-KD (pFER-KD) and lambda protein phosphatase-dephosphorylated pFER-KD. The reaction mixture contained 1 mM pFER-KD and 1 mM lambda protein phosphatase and was incubated for the indicated period.

(D) Sedimentation coefficient of FER-KD determined by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. The ratio relation of the protein oligomeric state of FER-KD protein is shown.

(E) Sedimentation coefficient of pFER-KD determined by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. The ratio relation of the protein oligomeric state of the pFER-KD protein is shown.

(F)Cis-/trans-autophosphorylation analyses of FER-KD by western blotting. The reaction mixture contained 1 mM Trx-FER-KD and 2 mM FER-KDK565R. Samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for 30 min.

To investigate the effect of autophosphorylation on the oligomerization state of FER-KD, we performed sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation on FER-KD and pFER-KD at concentrations of 19.7–22.5 μM (Figure 4D and 4E). Although FER-KD mainly exists as a monomer, the dimeric form of pFER-KD significantly increased in solution, indicating that autophosphorylation of FER-KD enhances its dimerization. To further investigate the autophosphorylation mechanism, we performed in vitro kinase assays by incubating thioredoxin (Trx)-FER-KD and FER-KDK565R (Figure 4F). The results showed that Trx-FER-KD could robustly phosphorylate both itself and FER-KDK565R, demonstrating that in vitro autophosphorylation of FER-KD occurs via an intermolecular (in trans) rather than an intramolecular (in cis) mechanism.

Key phosphorylation sites required for FER autophosphorylation in the activation segment

Autophosphorylation may be the most commonly observed mechanism that regulates protein kinase activity, as exemplified by BRI1 and BAK1 in plants (Yan et al., 2012; Bojar et al., 2014). Measurement of the ATPase activity of FER-KD and pFER-KD confirmed that FER-KD increased its catalytic activity through autophosphorylation (Supplemental Figure 4A). A common means of regulating catalytic activity is the phosphorylation of the kinase activation segment (Nolen et al., 2004). Therefore, we focused on identifying crucial autophosphorylation sites on the activation fragment.

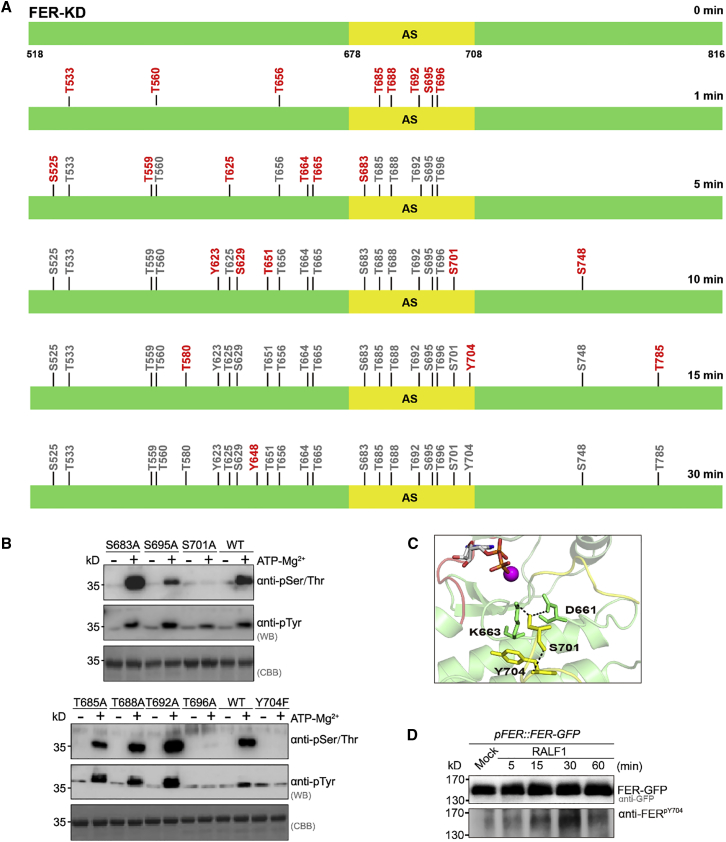

To identify specific phosphorylation sites, we took samples of FER-KD in time-course experiments (0, 1, 5, 10, 15, and 30 min) (Figure 4B) and identified the detailed autophosphorylation sites by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Figure 5A). Consistent with our previous results, no phosphorylation could be detected at 0 min. A total of 23 phosphorylation sites were identified in vitro at 30 min (Figure 5A; Supplemental Table 4), indicating saturation of phosphorylation within the 30-min time frame. We further investigated phosphorylation in the activation segment, which contains eight phosphorylatable residues, S683, T685, T688, T692, S695, T696, S701, and Y704. Five sites (T685/T688/T692/S695/T696) in the activation segment were phosphorylated at 1 min, and all eight autophosphorylation sites in the activation segment were phosphorylated at 15 min (Figure 5A; Supplemental Figure 5). To investigate the autophosphorylation capacity of these sites, mutants were constructed with a single S/T-to-A or Y-to-F substitution. Western blotting with anti-phosphorylated S/T/Y antibodies revealed that autophosphorylation levels of the single mutants of S683A, T685A, T688A, T692A, and S695A were comparable to that of the wild-type FER-KD protein (Figure 5B). By contrast, T696A, S701A, and Y704F resulted in a significant reduction in the autophosphorylation capacity of wild-type FER-KD (Figure 5B). Sequence alignment of the FER subfamily revealed that T696 is more than 80% conserved, and the S701A and Y704 sites are 100% conserved (Supplemental Figure 3). S701 is conserved in the FER subfamily and 72.8% of all Arabidopsis leucine-rich repeat RLKs (Wang et al., 2005). Notably, Y1052 in BRI1 is required for kinase activity in vitro and in vivo at the position equivalent to Y704 in FER (Bojar et al., 2014). The hydroxyl group of the S701 residue forms a hydrogen bond with the side-chain amino group of D661 and K663, which are essential residues for nucleotide binding (Figure 5C). Moreover, S701 forms a polar contact with Y704 through the amino group on its skeleton. In addition, previous studies have shown that T696 and S701 can be phosphorylated in vivo (Supplemental Figure 6) (Nuhse et al., 2004; Mayank et al., 2012). We treated 7-day-old pFER::FER-GFP seedlings with RALF1 and observed induced phosphorylation at Y704 sites (Figure 5C). The combination of in vitro and in vivo results showed that FER-KD is a dual-specificity kinase in which T696, S701, and Y704 in the activation segment are critical sites for autophosphorylation and catalytic activity.

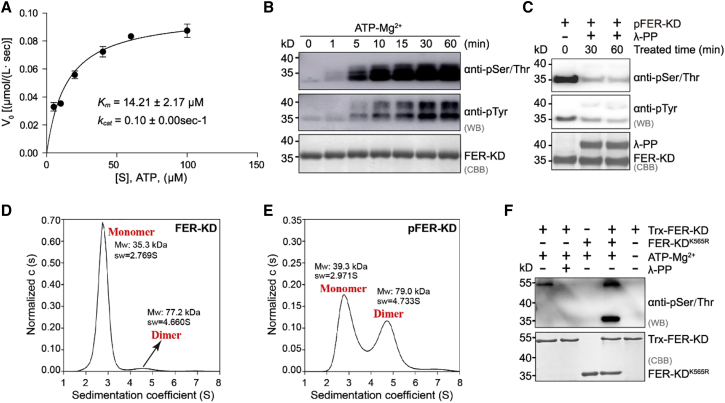

Figure 5.

Analyses of the autophosphorylation sites in the activation segment of FER-KD.

(A) Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry identification of FER-KD (green) autophosphorylation sites in vitro at different time points. The activation segment is presented in yellow. The phosphorylation sites are numbered in the top panel. Compared with the previous time point, newly emerging phosphorylation sites are shown in red.

(B) Western blot analysis of autophosphorylation by the FER-KD mutants. Samples (1 mM) were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM at 25°C for 30 min.

(C) View of the interaction networks of D661, K663, S701, and Y704 in the FER-KD activation segment. The interacting residues are indicated by yellow or green sticks. Hydrogen bonds are presented as black dashed lines.

(D) Identification of the phosphorylation site Y704 in vivo. RALF1-induced phosphorylation of Y704 of FER in 7-day-old pFER::FER-GFP seedlings is shown. Specific bands were recognized by anti-GFP and anti-pY704 antibodies at the indicated periods.

As observed in the crystal structure, the activation segment can be divided into four portions: the magnesium ion binding loop (residues 679–683 in FER), folded sheet β (residues 684–685), activation loop (residues 686–700), and P+1 loop (residues 701–708) (Nolen et al., 2004). T696 belongs to the activation loop, whereas S701 and Y704 belong to the P+1 loop. When we increased the protein concentration and prolonged the reaction time, the T696A single mutant exhibited a slight decrease in its autophosphorylation ability, and the S695A/T696A double mutant showed an almost complete loss of its autophosphorylation ability (Supplemental Figure 4B). Our observations suggest that both S695 and T696 residues may contribute to FER activation but that the S695 residue is not essential for FER autophosphorylation. T696 is the initial site for FER activation by autophosphorylation because its phosphorylation can be detected at as early as 1 min. By contrast, the autophosphorylation of S701 and Y704 was relatively delayed (at 10 and 15 min, respectively), suggesting that S701 and Y704 may affect subsequent substrate recognition or full activation of the kinase.

FER-KD autophosphorylation is essential for initiating substrate phosphorylation

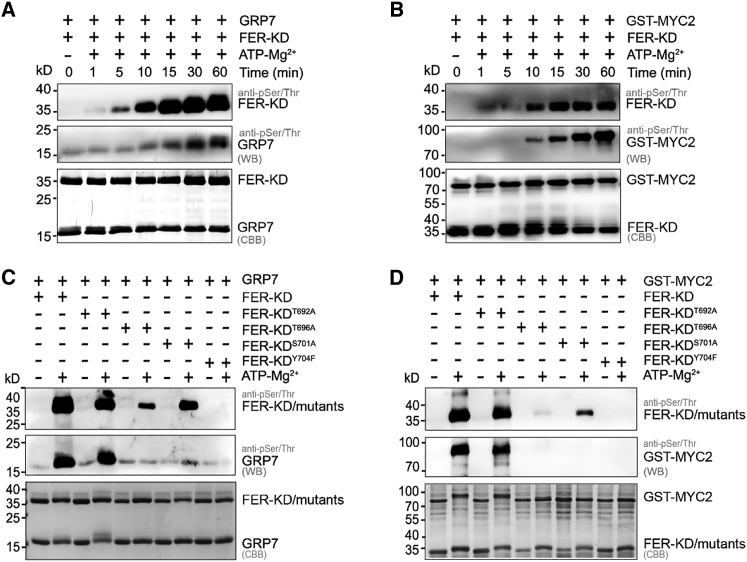

Previous studies have suggested that the autophosphorylation process is usually slow and may not compete with phosphorylation by the classical pathway. To test the importance of FER autophosphorylation, we used the previously reported FER phosphorylation substrate glycine-rich RNA-binding protein 7 (GRP7) or MYC2 (Guo et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020) as the substrate to verify the trans-phosphorylation activity and specificity of FER-KD.

With an increase in reaction time (0–60 min), FER-KD is able to transphosphorylate GRP7 or MYC2 well, indicating that FER-KD phosphorylates its physiological substrates similarly to its full-length form (Figure 6A and 6B). In particular, FER-KD trans-phosphorylation was observed to be much slower than autophosphorylation. At 15 min, FER-KD autophosphorylation was almost complete, but the trans-phosphorylation remained weak (Figure 6A and 6B). To confirm that autophosphorylation is required for trans-phosphorylation, we mutated several autophosphorylation sites in the activation segment of FER-KD to determine whether its trans-phosphorylation activity would be affected. Consistent with our hypothesis, the trans-phosphorylation activity of three mutants with defective autophosphorylation, FER-KDT696A, FER-KDS701A, and FER-KDY704F were significantly reduced (Figure 6C and 6D). It appeared that FER-KD turned on autophosphorylation before starting the trans-phosphorylation of GRP7 or MYC2 when its autophosphorylation reached a steady level. In summary, FER-KD autophosphorylation is essential for the initiation of substrate phosphorylation.

Figure 6.

FER-KD autophosphorylation is essential for initiating substrate phosphorylation.

(A) Time-course analysis of FER-KD trans-phosphorylation of the GRP7 substrate. Samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for the indicated period.

(B) Time-course analysis of FER-KD trans-phosphorylation of the MYC2 substrate. Samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for the indicated period.

(C)Trans-phosphorylation of the GRP7 substrate by FER variants with a single mutation in the activation segment. Samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for 60 min.

(D)Trans-phosphorylation of the MYC2 substrate by FER variants with a single mutation in the activation segment. Samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for 60 min.

Discussion

Many kinases are activated by phosphorylation of activation segment residues that is mediated by autophosphorylation or other kinases (Nolen et al., 2004). Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation allow interconversion between active and inactive conformations (Westphal et al., 1999). By contrast, the present work revealed that although full activation of FER requires autophosphorylation of the kinase, this plant RLK can adopt a phosphorylation-independent active conformation (Figures 1B–1F and 2A). FER-KD mutants share a similar active conformation with the wild-type kinase (Figure 2A and 2C), indicating that the identification of this conformation is not incidental. Although this phosphorylation-independent active conformation has not been described before in plants, it is not without precedent in animal systems. For example, both cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and epidermal growth factor receptor are activated by intermolecular interactions rather than phosphorylation (Jeffrey et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2006). Human IRAK4 KD, which has the highest structural similarity to FER-KD, can also adopt an active conformation without being phosphorylated (Wang et al., 2019). It is possible that this active conformation may be important for mediating certain functions of FER RLK.

Previous genetic studies have shown that kinase-dead FERK565R protein was able to complement ovule fertilization deficiency, FER-dependent mechanical ion signaling, rosette morphology, and RALF1-mediated stomatal movements (Shih et al., 2014; Kessler et al., 2015; Chakravorty et al., 2018), suggesting that the kinase activity of FER is not necessary for these processes. However, unlike wild-type FER, FERK565R could not rescue RALF1-mediated root growth inhibition (Haruta et al., 2018). Given that FER-KDK565R and the wild-type protein adopt an identical active conformation (Figure 2C), it is possible that most FER-mediated signal transductions are dependent on the intracellular KD itself, while the signal outputs vary according to the kinase activity. FERK565R may maintain its capability to partially recruit or activate specific downstream substrates for signal transduction, similar to some pseudo-kinases. Sequence analysis has revealed that pseudo-kinases (kinase defects) might account for approximately 20% of RLKs (Castells and Casacuberta, 2007), among which maize atypical receptor kinase (Llompart et al., 2003), strubbelig (Chevalier et al., 2005), crinkly4-related 1/2 (Cao et al., 2005), guard cell hydrogen peroxide-resistant 1 (Sierla et al., 2018), and pangloss 2 (Zhang et al., 2012) have important roles in different biological processes in plants. These results also suggest that kinase activity is not the only factor that prevents the kinase from performing its function, which may also be determined by its conformation, as in FER-KDK565R.

FER shares a conserved KD and may function in a complex with other members of the CrRLK1L subfamily. The interchangeability of the CDs of three members (FER, ANX1, and HERK1) suggests that CrRLK1L members can share intracellular signaling pathways (Kessler et al., 2015). FER, HERK1, and THESEUS 1 can respond to salt stress (Chen et al., 2016; Gigli-Bisceglia et al., 2022). In addition, HERK1 and ANJEA can associate with FER and LORELEI (LRE) to arrest PT growth at synergids, indicating the potential presence of HERK1–FER/LRE and ANJEA–FER/LRE complexes (Galindo-Trigo et al., 2020). These results suggest that there is both functional redundancy and functional complementarity among CrRLK1L members. FER may function both as a component of the direct signal transduction cascade reaction and as a co-receptor or scaffolding protein (Stegmann et al., 2017). This may also explain the difference in the phenotype of FERK565R in the complemented mutants. Our structural, biochemical, and mutagenesis study of FER-KD can serve as a paradigm for studying other CrRLK1L members and RLK activation.

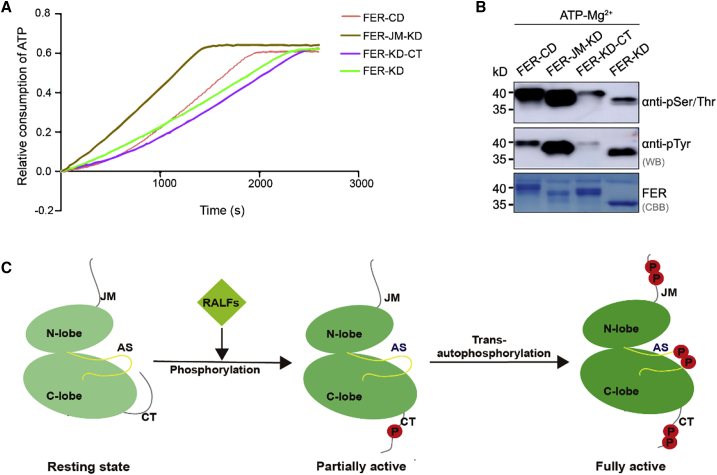

By ATPase activity measurements and western blot analysis of FER intracellular domain fragments, we found that the CT tail was negatively correlated with the regulation of FER-KD, whereas the JM was positively correlated with the regulation of FER-KD (Figure 7A and 7B). Phosphorylation of the CT tail of FER activates the kinase and initiates the RALF-induced signaling cascade (Haruta et al., 2014). We inferred that the initial phosphorylation of the CT tail might relieve the inhibitory effect of the CT region on the KD region. Based on our results and previous studies, we proposed a model of FER stepwise activation (Figure 7C). In the absence of a ligand, FER is in a resting state, i.e., a state in which FER kinase is unphosphorylated and autoinhibited by the CT. RALF recognition induces the phosphorylation of CT (such as S858, S871, and S874) through the JM and thus promotes the release of its autoinhibition, which causes the FER kinase to adopt a partially active state. Further intermolecular autophosphorylation (such as T696, S701, and Y704 in the activation segment) creates a fully activated FER. Specifically, FER is extended with autophosphorylation to provide a platform for protein substrate binding and mediation of the RALF1-induced signaling cascade. Our study revealed that substrate phosphorylation requires autophosphorylation of both the S/T and Y sites of FER. The S701 site and surrounding residues constitute the core of the P+1 pocket of FER. An in vivo study revealed that the corresponding site T1049 in BRI1 can be differentially phosphorylated to control substrate specificity (Bojar et al., 2014). Recent studies have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation is also essential for RLK-mediated signaling activation in plants (Perraki et al., 2018; Muhlenbeck et al., 2021). However, the detailed mechanism by which tyrosine phosphorylation contributes to kinase activation and substrate phosphorylation during these processes awaits future elucidation.

Figure 7.

Biochemical characteristics and model of the FER intracellular domain.

(A) ATPase activity of FER intracellular domain fragments.

(B) Western blot analysis of autophosphorylation by FER intracellular domain fragments.

(C) A model for stepwise activation of FER. In the absence of RALF ligands, FER kinase is unphosphorylated and autoinhibited by the CT. RALF ligand recognition induces conformational changes to FER, leading to phosphorylation of CT and thus promoting the release of its autoinhibition, placing the FER kinase in a partially active state. Further intermolecular autophosphorylation places FER in a fully activated state, and the activation segment is extended with phosphorylated sites to provide a platform for substrate binding.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

A series of FER intracellular domain fragments (FER-CD, FER-JM-KD, FER-KD-CT, and FER-KD) and all FER-KD mutations were cloned into the pRSF-Duet vector with an N-terminal 6×His tag. Trx-FER-KD was cloned into pET32a with a Trx tag, a 6×His tag, and an S tag in tandem at the N terminus; Trx is an approximately 12-kDa soluble E. coli protein that is used as a tag. A series of FER intracellular domain fragments, Trx-FER-KD, and the FER-KDS525A mutants were co-expressed with the Arabidopsis phosphatase ABI2, which was cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector (Chen et al., 2016). FER-KDK565R was directly expressed. GRP7 was cloned into the pGEX-6P-1 vector. GST-MYC2 (1–440 aa) was cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector. GRP7, GST-MYC2, and all FER-KD mutations were co-expressed with lambda protein phosphatase, which was cloned into the pGEX-6P-1 vector. All proteins were expressed in the same E. coli strain, BL21(DE3). Protein expression was induced at 289 K for 18 h with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside after the OD600 reached 0.6. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.5) containing 10 mM imidazole, and crushed using a low-temperature ultrahigh-pressure cell disrupter (JNBIO, Guangzhou, China). The soluble proteins were separated from cell debris by high-speed centrifugation (12 000 rpm for 1 h). The 6×His-tagged proteins were loaded onto a Ni2+ affinity column (Smart Life Sciences, SA004250) and washed with 100 ml washing buffer (PBS containing 20–100 mM imidazole). The target protein was eluted from the column with PBS containing 300 mM imidazole. GRP7/GST-MYC2 proteins were bound to GSTbeads (Smart Life Sciences, SA008100) and washed with 60 ml washing buffer (PBS; pH 7.5). GRP7 proteins were digested overnight with PreScission Protease (YBscience, YB11401) and eluted with PBS. GST-MYC2 proteins were eluted with 10 ml washing buffer (PBS containing 20 mM glutathione). All proteins were exchanged into Tris buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]) using centrifugal concentrators (10 kDa, Millipore, UFC901096) and concentrated to approximately 5 mg/ml for storage (193 K). To assemble the FER-KD and mutant complexes, 3 mg/ml purified FER-KD, FER-KDK565R, and FER-KDS525A were incubated with 10 mM Mg2+ and 1 mM ATP/ADP at 277 K for 2 h.

Protein crystallization and data collection

Crystallization of the FER–ATP/ADP complex was accomplished using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 1 μl protein complex with 1 μl reservoir solution in 24-well plates at 291 K (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA). Diffraction-quality crystals were obtained for the following complexes: FER-KD–ADP, FER-KDK565R–ATP, FER-KDK565R–ADP, and FER-KDS525A–ADP. FER-KD–ADP crystals were obtained from a crystallization buffer containing 0.1 M Tris (pH 8) and 30% v/v polyethylene glycol 400. FER-KDK565R–ATP crystals were obtained from a crystallization buffer containing 0.05 M magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.1 M HEPES 7.5, and 30% v/v polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 550. FER-KDK565R–ADP crystals were obtained from a crystallization buffer containing 0.1 M potassium chloride, 0.01 M magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.05 M Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.5), and 30% v/v polyethylene glycol 400. FER-KDS525A–ADP crystals were obtained from crystallization buffer containing 0.1 M Tris (pH 8) and 30% v/v polyethylene glycol 400. The best crystals were directly soaked in cryoprotectant solution (reservoir solution supplemented with 30% [v/v] glycerol) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen at 100 K. X-ray diffraction data were collected on beamline BL17U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility using an ADSC Q315 CCD detector. Datasets were processed and scaled using DIALS (Gildea and Winter, 2018). Data collection statistics are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Structure determination and refinement

The crystal structures of each of the four complexes (FER-KD–ADP, FER-KDK565R–ATP, FER-KDK565R–ADP, and FER-KDS525A–ADP) were determined by molecular replacement with the atomic coordinates of the Pto kinase in the Pto–AvrPto complex (PDB: 2QKW) as the initial search model. The atomic models were manually built in COOT (Emsley et al., 2010) and refined in PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010). Analysis with MOLPROBITY within the PHENIX suite (Liebschner et al., 2019) suggested the correct stereochemistry, with the fewest outliers in the Ramachandran plot. The refinement statistics are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. The atomic coordinates and structure data were deposited in the PDB. All structural figures were prepared with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger).

ATPase activity

To characterize ATPase activity, we performed an assay using the NADH-coupled enzyme system (Roskoski, 1983). It involves a peer–peer relationship between NADH and ATP, which are consumed during phosphorylation. Therefore, ATP consumption can be calculated by monitoring the reduction in NADH light absorption at 340 nm (ε340 = 6220 cm−1 M−1) using a UV spectrophotometer. Another feature of this system is that once ADP is produced, it is coupled to the enzymatic reaction to produce ATP, and thus the total amount of ATP in the reaction system is not depleted. Protein viability assays were performed at 25°C in a chamber containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 200 μM NADH, 1 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 1 mM ATP (different concentrations of ATP were used for the measurement of kinetic parameters), 20 units/ml lactate dehydrogenase, 15 units/ml pyruvate kinase, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and different concentrations of proteins in a 200-μl viability buffer system. Each assay was repeated three times, and similar results were obtained.

Sequence alignment

The amino acid sequences of FER subfamily proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR). The sequences were subjected to multiple sequence alignment using the T-Coffee server (Di Tommaso et al., 2011), and the multiple sequence alignment results were visualized using ESPript v.3.0 (Robert and Gouet, 2014).

Analysis of liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry data

Determination of in vitro phosphorylation sites was performed by Shanghai BioProfile Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). The peptides were analyzed with the Q Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were identified and quantified with Mascot software (v.2.3.01) using the TAIR database search algorithm and the integrated false discovery rate analysis function. These data were used to screen the TAIR10_pep_20101214 protein sequence database.

Western blotting

For pFER-KD, purified FER-KD protein was incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ for a 30-min reaction at 25°C, followed by buffer exchange into 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5) using centrifugal concentrators (Millipore, UFC901096).

For in vitro kinase assays, all samples were incubated with 1 mM ATP and 10 mM Mg2+ at 25°C for 30 min or for the specified time period. The samples were mixed with loading buffer (v/v) and boiled at 98°C for 5 min. All samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and either stained with Coomassie blue G250 or transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (PALL, P-N66485) for protein immunoblotting using anti-phosphothreonine (Abcam, ab218195), anti-phosphoserine (Abcam, ab9332), and anti-phosphotyrosine (Abcam, ab179530) antibodies.

For the in vivo FER phosphorylation assay, anti-FERpY704 antibodies were generated by ABclonal (Wuhan, China) (Liu et al., 2022). RALF1 was synthesized by Guoping Pharmaceutical and dissolved in water. For RALF1-induced phosphorylation of FER, 7-day-old pFER::FER-GFP seedlings were treated with liquid 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium containing 1 μM RALF1 for different times. Total protein was extracted from the seedlings and analyzed by SDS‒PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-pY704 and anti-GFP antibodies from ABclonal.

Analytical ultracentrifugation

The oligomeric states of FER-KD and pFER-KD in solution were assessed using sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation in an XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter) at 20°C. FER-KD/pFER-KD were prepared in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl, and the protein concentration was controlled at 0.4–0.8 mg/ml. Each 400-μl sample was centrifuged at 50 000 rpm for 8 h in an An50Ti rotor using 12-mm double-sector aluminum centerpieces. Sample data were recorded every few minutes. The data were then analyzed using SEDFIT 11.7, GUSSI, and SEDPHAT software (Brown and Schuck, 2006). Theoretical settlement data were calculated using HydroPro 7C (Garcia de la Torre et al., 2000) with a hydrated radius of 3.1 Å for the atomic elements.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160064, 31871396, 31571444, and 32000916); the State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources (SKLCUSA-a201806); the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M662764); the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2021JJ40050); the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2020GXNSFFA297007); and the Guangxi Key Laboratory for Sugarcane Biology (GXKLSCB-20190304).

Author contributions

Z.M. and F.Y. conceived the project and designed the research. Y.K., J.C., L.J., H.C., Y.S., L.W., and Y.Y. performed the research. Y.K. and Z.M. collected data. Z.M., F.Y., H.Z., Y.K., and J.C. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgments

We cordially thank the staff from beamline BL17U1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for assistance during data collection, as well as Shanghai BioProfile Biotechnology (Shanghai, China) for performing the liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry experiments and data analyses. We thank Cyril Zipfel, Kyle Bender, and Henning Mühlenbeck for critically reading this manuscript. We also thank Dongdong Li (Tsinghua University) for assistance with analytical ultracentrifugation data analysis. No conflict of interest is declared.

Published: February 11, 2023

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Feng Yu, Email: feng_yu@hnu.edu.cn.

Zhenhua Ming, Email: zhming@gxu.edu.cn.

Accession numbers

The PDB accession numbers for the FER-KD–ADP, FER-KDS525A–ADP, FER-KDK565R–ADP, and FER-KDK565R–ATP structures reported here are PDB: 7XDY, 7XDX, 7XDW, and 7XDV, respectively.

Supplemental information

References

- Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastidas A.C., Deal M.S., Steichen J.M., Guo Y., Wu J., Taylor S.S. Phosphoryl transfer by protein kinase A is captured in a crystal lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4788–4798. doi: 10.1021/ja312237q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkhadir Y., Jaillais Y. The molecular circuitry of brassinosteroid signaling. New Phytol. 2015;206:522–540. doi: 10.1111/nph.13269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojar D., Martinez J., Santiago J., Rybin V., Bayliss R., Hothorn M. Crystal structures of the phosphorylated BRI1 kinase domain and implications for brassinosteroid signal initiation. Plant J. 2014;78:31–43. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P.H., Schuck P. Macromolecular size-and-shape distributions by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4651–4661. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.081372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Li K., Suh S.G., Guo T., Becraft P.W. Molecular analysis of the CRINKLY4 gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2005;220:645–657. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells E., Casacuberta J.M. Signalling through kinase-defective domains: the prevalence of atypical receptor-like kinases in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:3503–3511. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty D., Yu Y., Assmann S.M. A kinase-dead version of FERONIA receptor-like kinase has dose-dependent impacts on rosette morphology and RALF1-mediated stomatal movements. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:3429–3437. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Yu F., Liu Y., Du C., Li X., Zhu S., Wang X., Lan W., Rodriguez P.L., Liu X., et al. FERONIA interacts with ABI2-type phosphatases to facilitate signaling cross-talk between abscisic acid and RALF peptide in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E5519–E5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608449113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Zhu S., Ming Z., Liu X., Yu F. FERONIA cytoplasmic domain: node of varied signal outputs. aBIOTECH. 2020;1:135–146. doi: 10.1007/s42994-020-00017-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier D., Batoux M., Fulton L., Pfister K., Yadav R.K., Schellenberg M., Schneitz K. STRUBBELIG defines a receptor kinase-mediated signaling pathway regulating organ development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9074–9079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503526102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tommaso P., Moretti S., Xenarios I., Orobitg M., Montanyola A., Chang J.M., Taly J.F., Notredame C. T-Coffee: a web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and RNA sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W13–W17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Xiao F., Fan F., Gu L., Cang H., Martin G.B., Chai J. Crystal structure of the complex between Pseudomonas effector AvrPtoB and the tomato Pto kinase reveals both a shared and a unique interface compared with AvrPto-Pto. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1846–1859. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du C., Li X., Chen J., Chen W., Li B., Li C., Wang L., Li J., Zhao X., Lin J., et al. Receptor kinase complex transmits RALF peptide signal to inhibit root growth in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E8326–E8334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609626113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W.G., Cowtan K. Features and development of coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Restrepo J.M., Huck N., Kessler S., Gagliardini V., Gheyselinck J., Yang W.C., Grossniklaus U. The FERONIA receptor-like kinase mediates male-female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science. 2007;317:656–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1143562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck C.M., Westermann J., Boisson-Dernier A. Plant malectin-like receptor kinases: from cell wall integrity to immunity and beyond. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018;69:301–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Trigo S., Blanco-Touriñán N., DeFalco T.A., Wells E.S., Gray J.E., Zipfel C., Smith L.M. CrRLK1L receptor-like kinases HERK1 and ANJEA are female determinants of pollen tube reception. EMBO Rep. 2020;21:e48466. doi: 10.15252/embr.201948466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García de la Torre J., Huertas M.L., Carrasco B. HYDRONMR: prediction of NMR relaxation of globular proteins from atomic-level structures and hydrodynamic calculations. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;147:138–146. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigli-Bisceglia N., van Zelm E., Huo W., Lamers J., Testerink C. Arabidopsis root responses to salinity depend on pectin modification and cell wall sensing. Development. 2022;149:dev200363. doi: 10.1242/dev.200363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildea R.J., Winter G. Determination of Patterson group symmetry from sparse multi-crystal data sets in the presence of an indexing ambiguity. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2018;74:405–410. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318002978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Nolan T.M., Song G., Liu S., Xie Z., Chen J., Schnable P.S., Walley J.W., Yin Y. FERONIA receptor kinase contributes to plant immunity by suppressing jasmonic acid signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:3316–3324.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M., Gaddameedi V., Burch H., Fernandez D., Sussman M.R. Comparison of the effects of a kinase-dead mutation of FERONIA on ovule fertilization and root growth of Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:2395–2402. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M., Sabat G., Stecker K., Minkoff B.B., Sussman M.R. A peptide hormone and its receptor protein kinase regulate plant cell expansion. Science. 2014;343:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.1244454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazak O., Hardtke C.S. CLAVATA 1-type receptors in plant development. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:4827–4833. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Zhou J., Shan L., Meng X. Plant cell surface receptor-mediated signaling - a common theme amid diversity. J. Cell Sci. 2018;131:jcs209353. doi: 10.1242/jcs.209353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Wang Z.Y., Li J., Zhu Q., Lamb C., Ronald P., Chory J. Perception of brassinosteroids by the extracellular domain of the receptor kinase BRI1. Science. 2000;288:2360–2363. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L., Rosenström P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen D.M., Bao Z.Q., O'Brien P., Brooks C.L., 3rd, Young M.A. Price to be paid for two-metal catalysis: magnesium ions that accelerate chemistry unavoidably limit product release from a protein kinase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15357–15370. doi: 10.1021/ja304419t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey P.D., Russo A.A., Polyak K., Gibbs E., Hurwitz J., Massagué J., Pavletich N.P. Mechanism of CDK activation revealed by the structure of a cyclinA-CDK2 complex. Nature. 1995;376:313–320. doi: 10.1038/376313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L.A., Mezulis S., Yates C.M., Wass M.N., Sternberg M.J.E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler S.A., Lindner H., Jones D.S., Grossniklaus U. Functional analysis of related CrRLK1L receptor-like kinases in pollen tube reception. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:107–115. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornev A.P., Taylor S.S., Ten Eyck L.F. A helix scaffold for the assembly of active protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14377–14382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807988105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuglstatter A., Villaseñor A.G., Shaw D., Lee S.W., Tsing S., Niu L., Song K.W., Barnett J.W., Browner M.F. Cutting Edge: IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 structures reveal novel features and multiple conformations. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2641–2645. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Liu X., Qiang X., Li X., Li X., Zhu S., Wang L., Wang Y., Liao H., Luan S., Yu F. EBP1 nuclear accumulation negatively feeds back on FERONIA-mediated RALF1 signaling. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2006340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Li M., Yu L., Zhou Z., Liang X., Liu Z., Cai G., Gao L., Zhang X., Wang Y., et al. The FLS2-associated kinase BIK1 directly phosphorylates the NADPH oxidase RbohD to control plant immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebschner D., Afonine P.V., Baker M.L., Bunkóczi G., Chen V.B., Croll T.I., Hintze B., Hung L.W., Jain S., McCoy A.J., et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2019;75:861–877. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner H., Müller L.M., Boisson-Dernier A., Grossniklaus U. CrRLK1L receptor-like kinases: not just another brick in the wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012;15:659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.B., Li X., Cai J., Jiang L.L., Zhang X., Wu D., Wang L., Yang A., Guo C., Chen J., et al. A screening of inhibitors targeting the receptor kinase FERONIA reveals small molecules that enhance plant root immunity. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023;21:63–77. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llompart B., Castells E., Río A., Roca R., Ferrando A., Stiefel V., Puigdomenech P., Casacuberta J.M. The direct activation of MIK, a germinal center kinase (GCK)-like kinase, by MARK, a maize atypical receptor kinase, suggests a new mechanism for signaling through kinase-dead receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48105–48111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho A.P., Lozano-Duran R. Molecular dialogues between viruses and receptor-like kinases in plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019;20:1191–1195. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayank P., Grossman J., Wuest S., Boisson-Dernier A., Roschitzki B., Nanni P., Nühse T., Grossniklaus U. Characterization of the phosphoproteome of mature Arabidopsis pollen. Plant J. 2012;72:89–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi V., Dunbrack R.L. Defining a new nomenclature for the structures of active and inactive kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:6818–6827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814279116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlenbeck H., Bender K.W., Zipfel C. Importance of tyrosine phosphorylation for transmembrane signaling in plants. Biochem. J. 2021;478:2759–2774. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20210202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan T., Chen J., Yin Y. Cross-talk of Brassinosteroid signaling in controlling growth and stress responses. Biochem. J. 2017;474:2641–2661. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen B., Taylor S., Ghosh G. Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nühse T.S., Stensballe A., Jensen O.N., Peck S.C. Phosphoproteomics of the Arabidopsis plasma membrane and a new phosphorylation site database. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2394–2405. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.023150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Y., Lu X., Zi Q., Xun Q., Zhang J., Wu Y., Shi H., Wei Z., Zhao B., Zhang X., et al. RGF1 INSENSITIVE 1 to 5, a group of LRR receptor-like kinases, are essential for the perception of root meristem growth factor 1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Res. 2016;26:686–698. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraki A., DeFalco T.A., Derbyshire P., Avila J., Séré D., Sklenar J., Qi X., Stransfeld L., Schwessinger B., Kadota Y., et al. Phosphocode-dependent functional dichotomy of a common co-receptor in plant signalling. Nature. 2018;561:248–252. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0471-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert X., Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R., Jr. Assays of protein kinase. Methods Enzymol. 1983;99:3–6. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)99034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih H.W., Miller N.D., Dai C., Spalding E.P., Monshausen G.B. The receptor-like kinase FERONIA is required for mechanical signal transduction in Arabidopsis seedlings. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:1887–1892. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu S.H., Bleecker A.B. Plant receptor-like kinase gene family: diversity, function, and signaling. Sci. STKE. 2001;2001:re22. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.113.re22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu S.H., Bleecker A.B. Receptor-like kinases from Arabidopsis form a monophyletic gene family related to animal receptor kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10763–10768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181141598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu S.H., Bleecker A.B. Expansion of the receptor-like kinase/Pelle gene family and receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:530–543. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierla M., Hõrak H., Overmyer K., Waszczak C., Yarmolinsky D., Maierhofer T., Vainonen J.P., Salojärvi J., Denessiouk K., Laanemets K., et al. The receptor-like pseudokinase GHR1 is required for stomatal closure. Plant Cell. 2018;30:2813–2837. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söding J., Biegert A., Lupas A.N. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W244–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Liu L., Wang J., Wu Z., Zhang H., Tang J., Lin G., Wang Y., Wen X., Li W., et al. Signature motif-guided identification of receptors for peptide hormones essential for root meristem growth. Cell Res. 2016;26:674–685. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmann M., Monaghan J., Smakowska-Luzan E., Rovenich H., Lehner A., Holton N., Belkhadir Y., Zipfel C. The receptor kinase FER is a RALF-regulated scaffold controlling plant immune signaling. Science. 2017;355:287–289. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su B., Zhang X., Li L., Abbas S., Yu M., Cui Y., Baluška F., Hwang I., Shan X., Lin J. Dynamic spatial reorganization of BSK1 complexes in the plasma membrane underpins signal-specific activation for growth and immunity. Mol. Plant. 2021;14:588–603. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trdá L., Boutrot F., Claverie J., Brulé D., Dorey S., Poinssot B. Perception of pathogenic or beneficial bacteria and their evasion of host immunity: pattern recognition receptors in the frontline. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:219. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li H., Han Z., Zhang H., Wang T., Lin G., Chang J., Yang W., Chai J. Allosteric receptor activation by the plant peptide hormone phytosulfokine. Nature. 2015;525:265–268. doi: 10.1038/nature14858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Ferrao R., Li Q., Hatcher J.M., Choi H.G., Buhrlage S.J., Gray N.S., Wu H. Conformational flexibility and inhibitor binding to unphosphorylated interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:4511–4519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yang T., Wang B., Lin Q., Zhu S., Li C., Ma Y., Tang J., Xing J., Li X., et al. RALF1-FERONIA complex affects splicing dynamics to modulate stress responses and growth in plants. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz1622. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Chory J. Brassinosteroids regulate dissociation of BKI1, a negative regulator of BRI1 signaling, from the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;313:1118–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1127593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Goshe M.B., Soderblom E.J., Phinney B.S., Kuchar J.A., Li J., Asami T., Yoshida S., Huber S.C., Clouse S.D. Identification and functional analysis of in vivo phosphorylation sites of the Arabidopsis BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE1 receptor kinase. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1685–1703. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal R.S., Coffee R.L., Jr., Marotta A., Pelech S.L., Wadzinski B.E. Identification of kinase-phosphatase signaling modules composed of p70 S6 kinase-protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) and p21-activated kinase-PP2A. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:687–692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Stegmann M., Han Z., DeFalco T.A., Parys K., Xu L., Belkhadir Y., Zipfel C., Chai J. Mechanisms of RALF peptide perception by a heterotypic receptor complex. Nature. 2019;572:270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Chen W., Song L., Chen Q., Zhang H., Liao H., Zhao G., Lin F., Zhou H., Yu F. FERONIA phosphorylates E3 ubiquitin ligase ATL6 to modulate the stability of 14-3-3 proteins in response to the carbon/nitrogen ratio. J. Exp. Bot. 2019;70:6375–6388. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Ma Y., Liu D., Wei X., Sun Y., Chen X., Zhao H., Zhou J., Wang Z., Shui W., Lou Z. Structural basis for the impact of phosphorylation on the activation of plant receptor-like kinase BAK1. Cell Res. 2012;22:1304–1308. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Facette M., Humphries J.A., Shen Z., Park Y., Sutimantanapi D., Sylvester A.W., Briggs S.P., Smith L.G. Identification of PAN2 by quantitative proteomics as a leucine-rich repeat-receptor-like kinase acting upstream of PAN1 to polarize cell division in maize. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4577–4589. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Gureasko J., Shen K., Cole P.A., Kuriyan J. An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell. 2006;125:1137–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Estévez J.M., Liao H., Zhu Y., Yang T., Li C., Wang Y., Li L., Liu X., Pacheco J.M., et al. The RALF1-FERONIA complex phosphorylates eIF4E1 to promote protein synthesis and polar root hair growth. Mol. Plant. 2020;13:698–716. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2019.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Fu Q., Xu F., Zheng H., Yu F. New paradigms in cell adaptation: decades of discoveries on the CrRLK1L receptor kinase signalling network. New Phytol. 2021;232:1168–1183. doi: 10.1111/nph.17683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo S., Clemens J.C., Hakes D.J., Barford D., Dixon J.E. Expression, purification, crystallization, and biochemical characterization of a recombinant protein phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:17754–17761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.