Dear Editor,

Many Cas9-derived base editors have been developed for precise C–to–T and A–to–G base editing in plants (Molla et al., 2021). They are typically based on a SpCas9 nickase or its engineered variants with altered protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) requirements (Molla et al., 2021). CRISPR–Cas12a enables highly efficient multiplexed genome editing in plants, and its T-rich PAM preference complements the G–rich PAM requirement of SpCas9 in genome targeting (Zhang et al., 2019, 2021). Because of the lack of an efficient Cas12a nickase, it has been challenging to develop efficient Cas12a base editors. Nevertheless, Cas12a cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) have been developed in mammalian cells (Li et al., 2018; Kleinstiver et al., 2019) with low DNA damage (Wang et al., 2020) because deactivated Cas12a (dCas12a) was used. However, efficient dCas12a base editors are yet to be developed in plants.

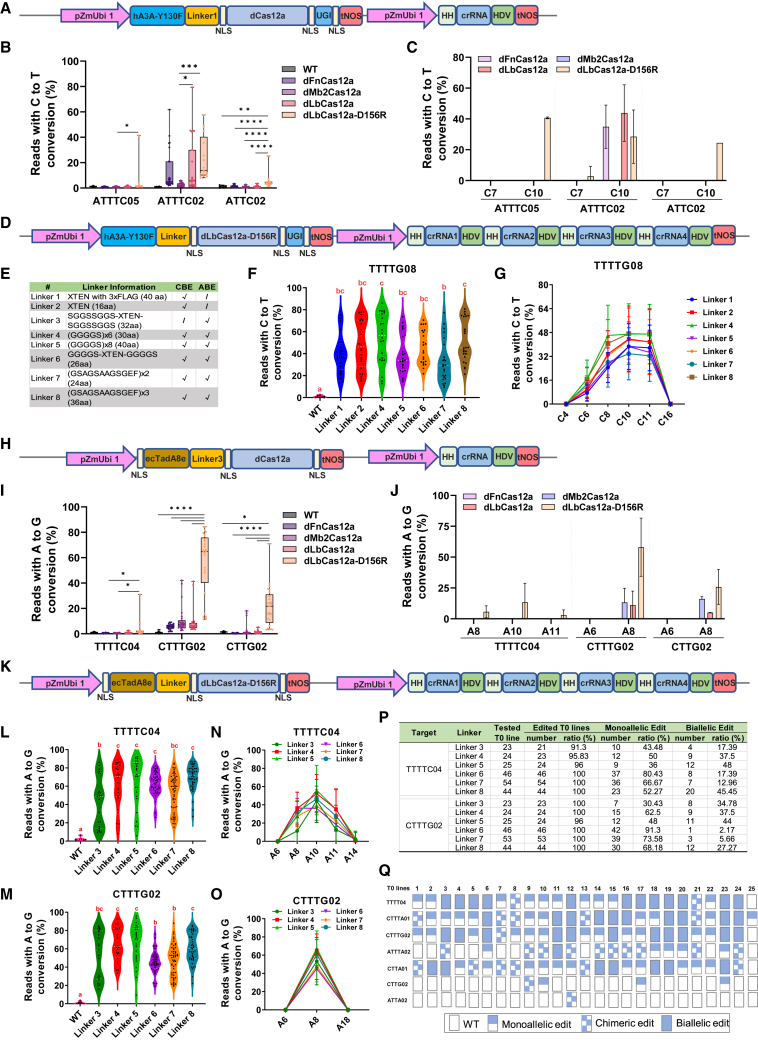

We reasoned that an efficient Cas12a base editor could be developed in plants if a high–processing deaminase was linked to an efficient dCas12a via an optimal linker. It was previously shown that cytidine deaminase hA3A-Y130F is highly efficient for Cas9D10A-mediated C–to–T base editing in plants (Li et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2021). We replaced the Cas9D10A part of this CBE system with deactivated versions of four efficient Cas12a proteins: FnCas12a (Endo et al., 2016), Mb2Cas12a (Zhang et al., 2021), LbCas12a (Tang et al., 2017), and LbCas12a–D156R (Kleinstiver et al., 2019), also known as ttLbCas12a (Schindele and Puchta, 2020). Using the dual RNA polymerase II (Pol II) expression system and a default linker 1 (Figure 1A), these four Cas12a CBEs were assessed at three target sites in stable transgenic T0 rice lines using next–generation sequencing (NGS). The CBE–based dLbCas12a–D156R outperformed other Cas12a CBEs at all three sites (Figure 1B), with a preferred substrate for cytosine base conversion at position 10 (C10) in the protospacer sequences. Sanger sequencing further confirmed the heterozygous or homozygous edits in some T0 lines (Supplemental Figure 1). Thus, this dLbCas12a–D156R CBE enables high-efficiency cytosine base editing in rice, consistent with the high nuclease activity of LbCas12a–D156R in Arabidopsis (Schindele and Puchta, 2020).

Figure 1.

Development of CRISPR–Cas12a–based cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) in rice.

(A) Schematic of the dual RNA polymerase II (Pol II) promoter system for dCas12a-based CBE and crRNA expression. pZmUbi1, maize ubiquitin promoter; NLS, nuclear localization signal; UGI, uracil DNA glycosylase; tNOS, nopaline synthase terminator; HH, hammerhead ribozyme; HDV, hepatitis delta virus ribozyme.

(B) Assessment of the C–to–T editing efficiency of four variants of dCas12a-based CBEs at sites ATTTC05, ATTTC02, and ATTC02 in transgenic rice plants.

(C) Editing window of four dCas12a-CBEs in transgenic rice plants at sites ATTTC05, ATTTC02 and ATTC02.

(D) Schematic of the dual Pol II promoter–based and multiplexed dLbCas12a-D156R CBE editing system.

(E) The list of linkers used between deaminases and dLbCas12a–D156R.

(F) Assessment of seven dLbCas12a–D156R CBEs with different linkers in regenerated rice calli at the TTTTG08 site. Each dot represents an independent callus. The first quartile, median, and third quartile are shown as dotted lines.

(G) Editing windows of seven dLbCas12a–D156R CBEs with different linkers in regenerated rice calli at the TTTTG08 site.

(H) Schematic of the dual Pol II promoter system for dCas12a–based ABE and crRNA expression.

(I) Assessment of A–to–G editing efficiency of four variants of dCas12a-based ABEs at sites TTTTC04, CTTTG02, and CTTG02 in transgenic rice plants.

(J) Editing window of four dCas12a– ABEs in transgenic rice plants at sites TTTTC04, CTTTG02, and CTTG02.

(K) Schematic of the dual Pol II promoter–based multiplexed dLbCas12a-D156R ABE editing system.

(L and M) Assessment of six dLbCas12a–D156R ABE editors with different linkers in transgenic rice plants at TTTTC04 and CTTTG02 sites. The first quartile, median, and third quartile are shown as dotted lines. Each dot represents an independent line.

(N and O) Editing windows of six dLbCas12a-D156R ABE editors with different linkers in transgenic rice plants at TTTTC04 and CTTTG02 sites.

(P) A–to–G base editing frequency of dLbCas12a–D156R–based ABEs at TTTTC04 and CTTTG02 sites.

(Q) Genotypes of 25 T0 lines edited by the dLbCas12a–D156R–linker 5–ABE at seven target sites. Wild type, chimeric edits, monoallelic edits, and biallelic edits are denoted as empty rectangles, dotted rectangles, half-filled rectangles, and fully filled rectangles, respectively.

To define genotypes in (P) and (Q): T0 lines with an A–to–G mutation frequency lower than 10% were regarded as wild type; T0 lines with an A–to–G mutation frequency from 10% to 30% were regarded as having chimeric edits; T0 lines with an A–to–G mutation frequency from 30% to 75% were regarded as having monoallelic edits; and T0 lines with an A–to–G mutation frequency higher than 75% were regarded as having biallelic edits. NGS of PCR amplicons was used to detect mutations in regenerated rice calli or T0 lines. All NGS data were analyzed with CRISPR RGEN tools. Data in (C), (G), (J), (N), and (O) are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. p values in (B) and (I) were obtained using a two-tailed Student’s t-test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05; one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s test) in (F), (L), and (M).

Encouraged by the promising data, we decided to further improve the system by testing different flexible linkers between hA3A–Y130F and dLbCas12a–D156R. We performed multiplexed editing with four crispr RNAs (crRNAs) targeting five sites using the dual Pol II promoter and the ribozyme processing system (Figure 1D) (Tang et al., 2017). Seven different flexible linkers, including the default linker 1, were compared (Figure 1E). The multiplexed CBE T-DNA expression vectors with different linkers were assessed in transgenic rice calli by NGS. At the TTTTG08 site, highly efficient base editing was observed for all Cas12a CBEs, especially with linkers 2 and 4 (Figure 1F). Lower C–to–T base editing efficiencies were seen at the other three target sites with all linkers (Supplemental Figure 2A–2C). The C–to–T editing frequency of site ATTC02 with a VTTV PAM was lower than 10% (data not shown). At these low-activity sites, only C10 was preferentially edited (Supplemental Figure 2D–2F). By contrast, the editing window was expanded to the C8 and C11 positions at the high-activity TTTTG08 site (Figure 1G). Further genotype analysis of TTTTG08 and ATTTC02 sites showed that the dCas12a-D156R CBE with linker 4 conferred more robust editing (Supplemental Figure 3).

Together, our data suggest that hA3A-Y130F-linker 4-dLbCas121-D156R is the most robust Cas12a CBE among all those tested. Considering that all four target sites with a TTTV (V = A, C, G) PAM could be efficiently edited by Cas12a nuclease (Zhang et al., 2021), it is striking to see drastic differences in C-to-T base editing efficiencies among these sites. This suggests that Cas12a nuclease activity cannot be used to predict Cas12a base-editing activity at the same target site. The editable cytosine depends upon the sequence context.

Next, we selected three top-performing Cas12a CBE systems (with linkers 2, 4, and 8) for analysis of byproducts and off-target effects. Insertion or deletion byproducts could be detected at the high–activity TTTTG08 site, albeit at low efficiency (Supplemental Figure 4A). At the three low–activity sites, no editing byproducts were detected (Supplemental Figure 4B–4D). Potential off-target sites were predicted using Cas–OFFinder, and crRNA–dependent off–target effects were analyzed in eight base-edited calli for the top three CBEs using NGS. No off–target editing was observed for any of the CBE systems (Supplemental Figure 5).

We next sought to develop efficient Cas12a ABEs for A–to–G base editing in plants. We fused the high–processing ecTadA8e (Richter et al., 2020) to dCas12a proteins and expressed the components with the dual Pol II promoter system (Figure 1H). With a default flexible linker 3 that connects ecTadA8e and dCas12a (Figure 1E), we compared four dCas12a proteins at three target sites in transgenic T0 rice lines. Consistent with the CBE data, dLbCas12a–D156R–based ABE showed the highest A–to–G base editing efficiencies at all three sites (Figure 1I). An editing window from A8 to A11 was identified (Figure 1J). We further investigated the editing events by Sanger sequencing (Supplemental Figure 6). Notably, dLbCas12a–D156R ABEs generated many monoallelic and biallelic edited lines at the CTTTG02 site. Moreover, 10 T0 plants were homozygous edited lines based on Sanger sequencing (Figures 1I and Supplemental Figure 6C). These data suggest that the dLbCas12a–D156R ABE is an efficient A–to–G base editing system in rice.

To further improve the dLbCas12a–D156R A–to–G editor, we compared six different flexible linkers (Figure 1E) with multiplexed editing using four crRNAs. Accordingly, six multiplexed LbCas12a-D156R ABEs with different linkers were constructed (Figure 1K). Because three of the four crRNAs (CA01, AA02, and CG02) can each target two sites with identical protospacers but different PAMs (TTTV or VTTV), a total of seven different sites in the rice genome were simultaneously targeted: four TTTV PAM sites and three VTTV PAM sites. Remarkably, high A–to–G editing was found at all four target sites with TTTV PAMs. The dLbCas12a–D156R ABEs with linkers 4, 5, and 8 outperformed ABEs with the other three linkers, generating higher enrichment of high–efficiency edited lines (Figures 1L and 1M and Supplemental Figures 7A and 7B). Consistently, these three dLbCas12a–D156R ABEs also produced more robust A–to–G base editing at the three target sites with non–canonical VTTV PAMs, especially at the CTTA01 site (Supplemental Figure 7C–7E). The editing window spanned from A8 to A12 in the protospacers (Figures 1N and 1O and Supplemental Figure 7F–7J). The dCas12a-D156R–based ABEs with linkers 4, 5, and 8 led to more robust A–to–G editing at the canonical TTTV PAM sites (Supplemental Figure 8).

We analyzed the genotypes of the resulting A–to–G editing lines at TTTTC04 and CTTTG02 sites. The data showed that dLbCas12a–D156R–based ABEs generated nearly 100% editing efficiency regardless of linkers (Figure 1P). Again, dLbCas12a-D156R-based ABEs with linkers 4, 5, and 8 stood out, as they led to high-frequency biallelic A–to–G base editing: 37.5%, 48%, and 45.45% at the TTTTC04 site and 37.5%, 44%, and 27.27% at the CTTTG02 sites, respectively (Figure 1P). We then expanded the genotype analysis to all seven target sites in 25 T0 lines edited by the efficient ecTadA8e–linker 5–dCas12a–D156R base editor. Impressively, five lines (#9, #10, #12, #17, and #23) showed simultaneous A–to–G editing at six target sites. Also, 10 T0 lines carried biallelic edits for at least three target sites, and two lines (#19 and #23) carried biallelic edits at four target sites (Figure 1Q and Supplemental Figure 9). Hence, multiplexed biallelic editing can be achieved within one generation using this ABE. Finally, we investigated the byproducts and crRNA–dependent off–target effects of these three top ABE systems. No significant byproduct editing and off–target editing were observed in the edited T0 lines examined (Supplemental Figures 10 and 11).

In this study, we developed highly efficient Cas12a CBEs and ABEs for multiplexed genome editing in plants. With less potential to generate DNA breaks compared with Cas9 nickase–based base editors, these T–rich PAM–targeting dCas12a base editors are very suitable for multiplexed promoter editing to fine–tune gene expression without generating insertion or deletion mutations. Our success is based on the combination of an efficient CRISPR–Cas12a expression system, a high–efficiency LbCas12a–D156R variant, high–activity cytidine and adenine deaminases, and optimal linkers. The optimized Cas12a CBEs produced highly efficient monoallelic editing at high–activity target sites. Significantly, the dLbCas12a–D156R ABEs developed in this study appear to be as efficient as the Cas9 ABEs (Molla et al., 2021). These efficient DNA break–free Cas12a CBE and ABE constructs have been deposited at Addgene and are promising tools for singular and multiplexed base editing in plants.

Funding

This work is supported by NSF Plant Genome Research Program grants (award nos. IOS-2029889 and IOS-2132693), the USDA-AFRI Agricultural Innovations Through Gene Editing Program (award no. 2021-67013-34554), the FFAR New Innovator Award (award no. 593603), and Syngenta.

Author contributions

Y.C. and Y.Q. designed the experiments. Y.C., Y.Z., G.L., H.F., and S.S. generated the vectors. Y.C. performed rice transformation and NGS analysis for genome editing in transgenic rice calli and plants. Y.C. and A.F. performed Sanger sequencing of transgenic lines. J.X., J.L., and Q.Q. provided guidance on linkers for vector design. Y.C. and Y.Q. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in discussion and revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Some linkers used in this study were disclosed in a Syngenta patent application (WO2021061507). No conflict of interest is declared.

Published: April 14, 2023

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Supplemental information

References

- Endo A., Masafumi M., Kaya H., Toki S. Efficient targeted mutagenesis of rice and tobacco genomes using Cpf1 from Francisella novicida. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep38169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver B.P., Sousa A.A., Walton R.T., Tak Y.E., Hsu J.Y., Clement K., Welch M.M., Horng J.E., Malagon-Lopez J., Scarfò I., et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas12a variants with increased activities and improved targeting ranges for gene, epigenetic and base editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:276–282. doi: 10.1038/s41587-018-0011-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Sretenovic S., Eisenstein E., Coleman G., Qi Y. Highly efficient C-to-T and A-to-G base editing in a Populus hybrid. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:1086–1088. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Wang Y., Liu Y., Yang B., Wang X., Wei J., Lu Z., Zhang Y., Wu J., Huang X., et al. Base editing with a Cpf1-cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:324–327. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molla K.A., Sretenovic S., Bansal K.C., Qi Y. Precise plant genome editing using base editors and prime editors. Nat. Plants. 2021;7:1166–1187. doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-00991-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Q., Sretenovic S., Liu G., Zhong Z., Wang J., Huang L., Tang X., Guo Y., Liu L., Wu Y., et al. Improved plant cytosine base editors with high editing activity, purity, and specificity. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:2052–2068. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M.F., Zhao K.T., Eton E., Lapinaite A., Newby G.A., Thuronyi B.W., Wilson C., Koblan L.W., Zeng J., Bauer D.E., et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:883–891. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0453-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindele P., Puchta H. Engineering CRISPR/LbCas12a for highly efficient, temperature-tolerant plant gene editing. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020;18:1118–1120. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Lowder L.G., Zhang T., Malzahn A.A., Zheng X., Voytas D.F., Zhong Z., Chen Y., Ren Q., Li Q., et al. A CRISPR-Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing and transcriptional repression in plants. Nat. Plants. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ding C., Yu W., Wang Y., He S., Yang B., Xiong Y.C., Wei J., Li J., Liang J., et al. Cas12a base editors induce efficient and specific editing with low DNA damage response. Cell Rep. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Malzahn A.A., Sretenovic S., Qi Y. The emerging and uncultivated potential of CRISPR technology in plant science. Nat. Plants. 2019;5:778–794. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ren Q., Tang X., Liu S., Malzahn A.A., Zhou J., Wang J., Yin D., Pan C., Yuan M., et al. Expanding the scope of plant genome engineering with Cas12a orthologs and highly multiplexable editing systems. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1944. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22330-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.