Abstract

We explored a possible role of oxytocin (OXT) for the onset and maintenance of rabbit maternal behavior by: a) confirming that a selective oxytocin receptor antagonist (OTA) widely used in rodents selectively binds to OXT receptors (OXTR) in the rabbit brain and b) determining the effect of daily intracerebroventricular (icv) injections of OTA to primiparous and multiparous does from gestation day 29 to lactation day 3. OTA efficiently displaced the high affinity, selective oxytocin receptor (OXTR) radioligand, 125I-labeled ornithine vasotocin analog (125I-OVTA), but was much less effective at displacing the selective V1a vasopressin receptor radioligand, 125I-labeled linear vasopressin, thus showing high affinity and selectivity of OTA for rabbit OXTR as in rodents. Further, ICV OTA injections did not modify nest-building, latency to enter the nest box, time spent nursing or the amount of milk produced, relative to vehicle-injected does. The percentage of mothers suckling the litter was also similar between both groups, regardless of parity. Together, our results do not support a role of OXT for the initiation or maintenance of rabbit maternal behavior. Future studies are warranted to determine if OXT participates in fine-tuning additional aspects of the maternal ethogram, e.g., circadian periodicity of nursing and nest defense.

Keywords: oxytocin, maternal behavior, rabbit, nursing, nest-building, oxytocin antagonist, intracerebroventricular, parity, maternal experience

Introduction

A large body of evidence supports the participation of steroid, protein and peptide hormones in the regulation of maternal behavior in mammals (for reviews see: González-Mariscal and Poindron, 2002; Numan, 2020; Rilling and Young, 2014). The so-called ‘maternal brain’ coordinates innumerable functions and activities that are unique to pregnancy or lactation and are species-specific, such as: nest-building, retrieving, grouping and licking the young, crouching over the litter and, of course, nursing. Rabbits build, from mid-pregnancy until parturition, an elaborate nest of straw and body hair inside a burrow. This process is controlled by the changing levels of estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, and prolactin (González-Mariscal et al., 2016). Doe rabbits deliver the litter inside the nest and lick the kits at parturition. Across the 30 days of lactation, maternal care is restricted to a single nursing bout per day, which occurs as the mother jumps inside the nest box and crouches over the litter to allow suckling. This behavior is displayed with circadian periodicity and lasts between 3-5 min (González-Mariscal et al., 2013 a, b). Milk output increases steadily across the first 20 days and gradually decreases in late lactation (González-Mariscal et al., 1994; Maertens et al., 2006). Oxytocin (OXT) secretion, in response to suckling, increases with the progress of lactation and there is a clear relation between the number of suckling kits and the amount of OXT released (Fuchs and Wagner, 1963; Fuchs et al., 1984). This hormone is also secreted massively during parturition and very low levels of OXT are detected in the circulation during pregnancy (Fuchs and Dawood, 1980).

In addition to the ‘classic’ actions of OXT on the mammary gland and uterus this hormone has been shown to facilitate the expression of maternal behaviour in rodents (Numan and Young, 2016; Froemke and Young, 2021; Yoshihara et al., 2018). Indeed, maternal behaviour is deficient in nulliparous OXT knockout mice towards foster pups (Pedersen et al., 2006). Yet, OXT knockout dams show no alterations in maternal behaviour towards their litter (Nishimori et al., 1996). However, OXT receptor (OTR) knockout dams do show deficits in maternal behaviour towards their pups (Takayanagi et al., 2005). Moreover, infusing an OTR antagonist (OTA) into the lateral ventricle of lactating rats markedly reduces the frequency of arched-back nursing towards their litter (Bosch and Neumann, 2008). Furthermore, recent studies in mice demonstrate that OXT modulates the excitatory-inhibitory balance of circuits in the auditory cortex of mice to enhance salience to pup ultrasonic vocalizations and enables maternal responsiveness (Marlin et al., 2015). OXT also enables the social transmission of maternal behaviour in co-housed female mice (Carcea et al., 2021). A particularly well-explored model for OXT function are voles, in which some species (Microtus ochrogaster, prairie voles; M. pinetorum, pine voles) are monogamous-biparental while others are polygamous-monoparental (M. montanus, montane voles; M. pennsylvanicus, meadow voles). Although both types of animals have brain OTR, their neuroanatomical distribution is different. Specifically, prairie voles show an abundance of OTR in the prelimaternal behaviouric cortex, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, nucleus accumbens, and lateral amygdala while polygamous voles show lower densities in the last two regions but OTR are abundant in the lateral septum (LS; Insel and Shapiro, 1992; Young, 1999; Inoue et al., 2022). Rabbits, social animals living in colonies, are polygamous-monoparental and their brain distribution of OTR resembles that of montane and meadow voles. Particularly high densities of OTR are found in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), medial preoptic area (MPOA), and LS (Jiménez et al., 2015); their abundance varies in relation to the female’s reproductive state. These regions are involved in the regulation of nest-building (Basurto et al., 2018; Cano-Ramírez and Hoffman, 2018) and nursing (Cruz and Beyer, 1972). Moreover, bilateral lesions of the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVN), particularly rich in OXT-immunoreactive cells in lactating doe rabbits (Caba et al., 1996), disrupt or abolish circadian nursing (Domínguez et al., 2017). Although the above evidence supports a facilitatory role of OXT for the facilitation of rabbit maternal behavior, this possibility has not been directly explored. Therefore, in the present work we investigated whether intracerebroventricular (icv) injections of an OTA, known to inhibit maternal behaviour in lactating rat dams (van Leengoed et al., 1987) and also in pregnancy-terminated hysterectomized estrogen-treated rats (Fahrbach et al., 1985), can interfere with nest-building and nursing in rabbits. We first established that OTA binds selectively to the rabbit OTR using receptor autoradiography by examining displacement of highly selective OTR and vasopressin V1a receptor (AVPR1A) in brain slices. To distinguish between a priming role and a triggering action of OXT, we compared the effects of OTA in primiparous vs multiparous does.

Methods

Animals and housing conditions.

New Zealand white rabbits bred in our colony were used. At the start of the experiment 27 females had experienced one previous pregnancy, parturition and lactation (‘multiparous’ group) and 39 were adult virgins (‘primiparous’ group). They were kept inside a vivarium with natural temperature and artificial light (14 h light:10 h darkness; lights on at 0700 h). They were given tap water and rabbit pellets (Conejina, Purina™) ad libitum. Does were mated with sexually active bucks inside a round (1 m diameter) wire mesh arena. The day after mating was considered gestation day 1.

Brain tissue collection and receptor autoradiography.

Competitive receptor autoradiography using OTR and AVPR1A selective radioligands was used to determine whether OTA efficiently binds selectively to rabbit OTR as it does in rodents. The brains of two virgin and two multiparous does were removed from the skulls, frozen immediately on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C until sectioned. Twenty micrometer thick frozen brain sections, obtained using a cryostat, were collected from the lateral septum (LS), which we previously determined had high levels of OTR radioligand binding (Jiménez et al., 2015). Sections were mounted on Superfrost plus slides (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), and stored at −80 °C until used for autoradiography. Brain sections were removed from freezer, allowed to air dry, dipped in 0.1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), and rinsed twice in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) to remove endogenous OXT. Tissue was then incubated for 1 h in 50pM 125I-ornithine vasotocin analog (125I-OVTA, 2200 Ci/mmol; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), a radioligand previously used by us to detect OTR in the rabbit brain (Jiménez et al., 2015). Serial sections were used to determine whether binding of 125I-labeled ornithine vasotocin analog (125I-OVTA) could be displaced by increasing concentrations (0 pM, 500 pM, 5 nM, or 50 nM) of the OXT antagonist (OTA: d(CH2)5[Tyr(Me)2Thr4,Tyr-NH2(9)]ornithine vasotocin. This antagonist has been shown to have high affinity for OTR and selectivity over vasopressin receptors in rodents (Manning et al., 2012). A separate series of slides were incubated with the OXTR radioligand and the selective OXTR agonist [Thr4,Gly7]-oxytocin peptide (TGOT, 50 nM) to confirm selectivity of the OXTR radioligand for the rabbit OXTR (Manning et al., 2012). Another series of sections were used to examine the selectivity of OTA for OXTR vs AVPR1A by determining if the same concentrations of OTA could displace the selective AVPR1A radioligand 125I-labeled linear vasopressin (LVA). To confirm selectivity of the LVA for AVPR1A, we co-incubated the LVA with the Manning compound: d(CH2)5[Tyr(Me)2]AVP), a selective AVPR1A antagonists in other species (Manning et al., 2012). The slides were finally quickly dipped in cold dH20, rapidly dried and exposed to Bio Max MR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) 125I-OVTA bound slides were exposed to film for 10 days, and the LVA bounds slides for 4 days. All slides from the four does used were processed in a single assay to avoid interassay variation.

Quantification of maternal behaviour.

The possible effects of OTA were determined on two aspects of early maternal behaviour: nest-building in late pregnancy and nursing on postpartum days 1-3. Across pregnancy and lactation, does were housed in wire mesh maternal cages (90 cm long x 60 cm wide x 40 cm high) that held a wooden nest box with a round opening in the front, to allow the construction of the maternal nest. It contained a piece of compressed cardboard placed on the floor to allow the expression of digging behaviour and, from pregnancy day 20 until parturition, 300 g of straw was provided daily as material for nest building. The three activities involved in this process, i.e., digging, straw-carrying, and hair-plucking, were quantified at 1200 h on pregnancy days 21, 25, 27, 28, and 30, as previously described (González-Mariscal et al., 1994). Starting on pregnancy day 30 does were spot-checked across the day, to determine the approximate time of delivery (pregnancy lasts 30-32 days; González-Mariscal et al., 1994). They were allowed to remain undisturbed for the following 3 h postpartum, except for the injection of OTA, which started on gestation day 29 (see below). Three hours after delivery kits were counted and all litters were adjusted to six (simply by removing the “extra” kits). Litters were not sex balanced as, in rabbits, it is impossible to determine the sex of the newborn through an outward body inspection. Six-kit litters were then transferred to acrylic boxes containing paper strips, and placed under a mild heat source in a different room. Every day, from then until postpartum day 3, kits were brought back to the mother at 12 h to determine: a) the latency to enter the nest box (i.e., the time elapsed between introduction of the kits into the nest box and the mother jumping inside); b) the time spent nursing (i.e., the time elapsed between the mother’s entrance into the nest box, where she crouched over the litter to allow suckling, and her exit from the nest box); c) milk output (calculated by comparing the litter weight before vs after nursing). A time limit of 60 min, starting at the introduction of kits into the nest box, was set to determine whether a doe nursed or not. If she did not engage in nursing the litter was removed (at 13 h) and reintroduced 24 h later, across lactation days 1-3.

Unilateral icv injections of OTA.

On pregnancy day 14, females were anesthetized with i.m. injections of ketamine (25 mg/kg)/rompun (8 mg/kg) and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame using sterile conditions. A 22 gauge stainless steel cannula was then lowered into the lateral ventricle, following the stereotaxic coordinates (relative to bregma), derived from the atlas of Girgis and Shih-Chang (1981): rostrocaudal=0.5; lateral=2.5; dorsoventral=−5.0. The guide cannula was fixed to the skull with dental acrylic and females received 200,000 units of penicillin (i.m.). They were kept warm in a recovery room for 1 h and were then transferred back to their maternal cage for the remaining of the experiment.

Administration schedule of OTA or vehicle.

From gestation day 29 to lactation day 3 a 30 gauge stainless steel needle was introduced daily into the guide cannula and connected, through a PE 50 Clay-Adams polyethylene tubing, to a Hamilton microsyringe filled with a solution of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; vehicle, VEH) or OTA: (d(CH2)51, Tyr(ME)2, Thr4, Orn8, des-Gly-NH29)-Vasotocin; Bachem. This antagonist has been shown to have high affinity for OTR and selectivity over vasopressin receptors in rodents (Manning et al., 2012). A dose of 50 ng, in a volume of 5 μl, was injected across 2 min, after which the needle was left in place for a further 1 min. These procedures took place between 11 to 12 h. One hour later does were tested for maternal behaviour as described above. From the agent injected icv and the parity of rabbits four experimental groups were established: primiparous-VEH (n=8), primiparous-OTA (n=31), multiparous-VEH (n=15), and multiparous-OTA (n=12). Thus, throughout this work we evaluated the effect of OTA or VEH on early maternal behavior, i.e., prepartum nest-building and lactation days 1-3.

Verification of cannula placement.

At the end of experiments does were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital i.v. (10 mg/Kg; Pfizer, Mexico) and injected, through the implanted cannula, with methylene blue (5 μl of a 1% solution). Rabbits were sacrificed three minutes later with an overdose of pentobarbital, the brain was removed from the skull and cut with a blade just rostral to the cannula. In animals that had the cannula correctly placed, methylene blue was easily observed inside the ventricle. Only these rabbits were included in the reported results.

Statistical analysis.

A two-way ANOVA was used to determine, among the four experimental groups, the effects of parity and agent injected icv on all parameters measured regarding nest-building and nursing. A General Linear Model determined whether an interaction existed between parity and agent injected. When pertinent, the two-way ANOVA was followed by a post-hoc test (Holm-Sidak). A chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of does that pulled hair or nursed in relation to parity and injected agent. Milk output across lactation days 1, 2, 3 was compared in primiparous and multiparous rabbits receiving icv OTA or VEH. The amounts obtained on each of these days (for each group) were added to determine a single value of total milk output. A two-way ANOVA of the original individual values compared the effects of parity and agent injected icv. The statistical software package used was Sigma Plot 11.

Throughout this work, animal care adhered to the Law for the Protection of Animals (Mexico: NOM-062-200-1999) in accordance with international guidelines regarding animal research (González-Mariscal et al., 2017). The ethical board that cleared this study was composed of two veterinarians from our institutions (CINVESTAV and Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala) with years of experience in rabbit research.

Results

OTA binding to OTR and AVPR1A.

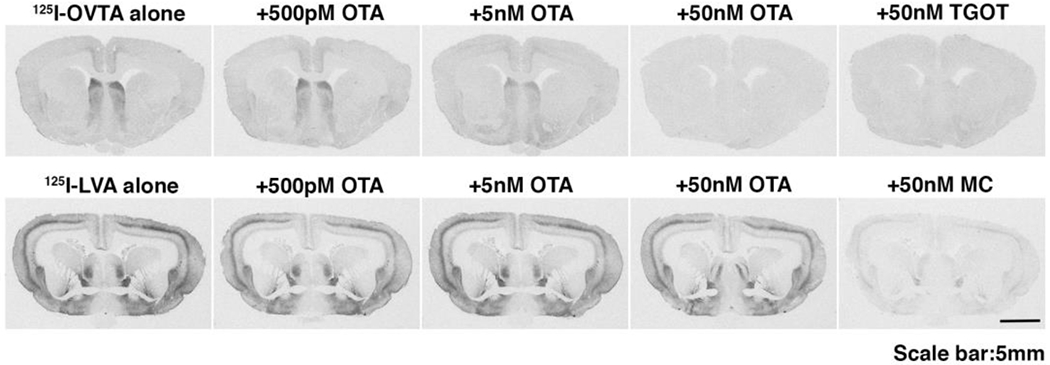

Competitive receptor autoradiography revealed that OTA effectively displaces the selective OTR radioligand, 125I-OVTA, from the lateral septum binding sites, with robust displacement of 50 pM of radioland at 5nM and elimination of 125I-OVTA binding at 50 nM (Fig. 1, upper row). TGOT (50 nM), a highly selective OXTR agonist, also completely eliminated 125I-OVTA, demonstrating that 125I-OVTA is highly specific for the rabbit OXTR. In contrast, the AVPR1A receptor radioligand, LVA (50 pM), gave a distinct pattern of binding, with high densities of binding in the cortex and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. 50 nM OTA resulted in minimal displacement of LVA, while the same concentration of the selective AVPR1A antagonist, Manning Compound (MC), efficiently displaced LVA (Fig. 1, lower row). Thus OTA was confirmed to have similar binding characteristics in rabbits as reported in rodents.

Fig. 1.

Upper row: autoradiograms showing that the relative binding of 125I-OVTA to the lateral septum was gradually reduced by increasing concentrations of OTA or by 50 nM TGOT. Lower row shows that 125I-LVA binding was decreased only by 50 nM of OTA or Manning compound (MC).

Nest building.

Table 1 shows the expression of digging, straw-carrying and hair-pulling in the four experimental groups. Before females received icv injections of vehicle or OTA, parity had a significant effect on digging as multiparous does dug much more than primiparous ones [F(1, 46)=8.699, p=0.005]. Injections of OTA or VEH had no significant effects on digging [F(1, 46)=0.0149, p=0.903. No significant differences were evident in straw-carrying due to either parity [F(1, 46)=1.390, p=0.245] or agent injected [F(1, 46)=0.0149, p=0.903]. Interactions between these two factors were not statistically significant [F(1, 46)=0.000191, p=0.989]. Similarly, the proportion of primiparous vs multiparous does that pulled hair before icv injections was not significantly different (DF=1, p=0.09). The icv injection of OTA did not modify, in primiparous does, the expression of hair-pulling on gestation day 30, relative to VEH-injected rabbits (DF=1, p=0.5).

Table 1.

Nest-building, quantified before (Pre) and after (Post) daily icv injections of vehicle or OTA (started on gestation day 29)

| Group A | Digging (g; median±iqr)& | Straw-carrying (g; median±iqr)& |

Hair-pulling (% females) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre* | Post | Pre* | Post | Prea | Postb | |

| Primiparous-VEH (n=6) |

126 (20, 261) |

ND |

35 (12, 63) |

ND | 33.3% | 66.6% |

| Primiparous-OTA (n=26) |

ND | ND | 30.7% | 65.4% | ||

| Multiparous-VEH (n=13) |

351 (191, 420) B |

ND |

20 (6, 42) |

ND | 7.6% | 53.8% |

| Multiparous-OTA (n=2) |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

values obtained on gestation days 21, 25, 27, and 28 were added to give a single number for each experimental animal during the “pre” phase

“Pre” values for digging and straw-carrying were combined, in primiparous and multiparous groups, to include both VEH and OTA animals, as does had not yet been given any icv injections. Thus, n=32 and n=15, respectively

determined on gestation day 28

determined on gestation day 30

ND=not determined because OTA (or VEH) injections began on gestation day 29 and, by that time, digging and straw-carrying had already occurred.

Number of does shown in each group corresponds to those mothers from which we were able to quantify digging, straw-carrying or hair-pulling

DF=3, F=4.996, p=0.005

Nursing.

Table 2 shows the proportion of does that nursed on lactation days 1, 2, and 3 in each of the four experimental groups. No significant effects were seen as a consequence of the agent injected icv (i.e., VEH or OTA) in either primiparous or multiparous does (p>>0.05; chi-square test) on any day. Additionally, no effects of parity were evident in either VEH- or OTA-injected does (p>>0.05; chi-square test).

Table 2.

Proportion and number of females that nursed across postpartum days 1-3, relative to parity and agent injected daily icv from gestation day 29 to lactation day 3*

| Group | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primiparous-VEH | 75% (6/8) | 62% (5/8) | 75% (6/8) |

| Primiparous-OTA | 84% (26/31) | 84% (26/31) | 71% (22/31) |

| Multiparous-VEH | 87% (13/15) | 73% (11/15) | 87% (13/15) |

| Multiparous-OTA | 75% (9/12) | 67% (8/12) | 67% (8/12) |

A time limit of 60 min, starting at the introduction of kits into the nest box, was set to determine whether a doe nursed or not.

Table 3 shows the latency to enter the nest box in does that nursed on postpartum days 1, 2, and 3 of each group. No significant differences occurred on day 1 due to the injected agent [F(1, 53)=0.692, p=0.410] or parity [F(1, 53)=0.815, p=0.371]. Possible interactions between these two factors were not statistically significant [F(1, 53)=0.692, p=0.410]. On day 2 a significant effect of parity was evident, as primiparous rabbits showed a significantly longer latency to enter the nest box [F(1, 50)=4.667, p=0.036]. No significant effects were found in relation to: a) the injected agent [F(1, 50)=2.606, p=0.113]; b) an interaction between injected drug and parity [F(1, 50)=2.606, p=0.113]. No significant effects of either parity [F(1, 46)=1.276, p=0.265], injected drug [F(1, 46)=0.0308, p=0.862] or interaction between both factors [F(1, 46)=0.396, p=0.533] were evident on Day 3.

Table 3.

Latency to enter the nest box in females that nursed on postpartum days 1-3, relative to parity and agent injected icv* (mean±se; minutes)

| Group | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primiparous-VEH | 0.2±0.2 | 5.4±5.4 | 5.16±4.8 |

| Primiparous-OTA | 4.4±2.3 | 0.8±6.0 | 2.4±2.3 |

| Multiparous-VEH | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

| Multiparous-OTA | 0±0 | 0±0 | 1.3±1.3 |

data derived from the number of nursing does shown in Table 2. A two-way ANOVA was used to determine, on days 1, 2, and 3: a) the effects of parity and injected agent; b) a possible interaction between those two factors

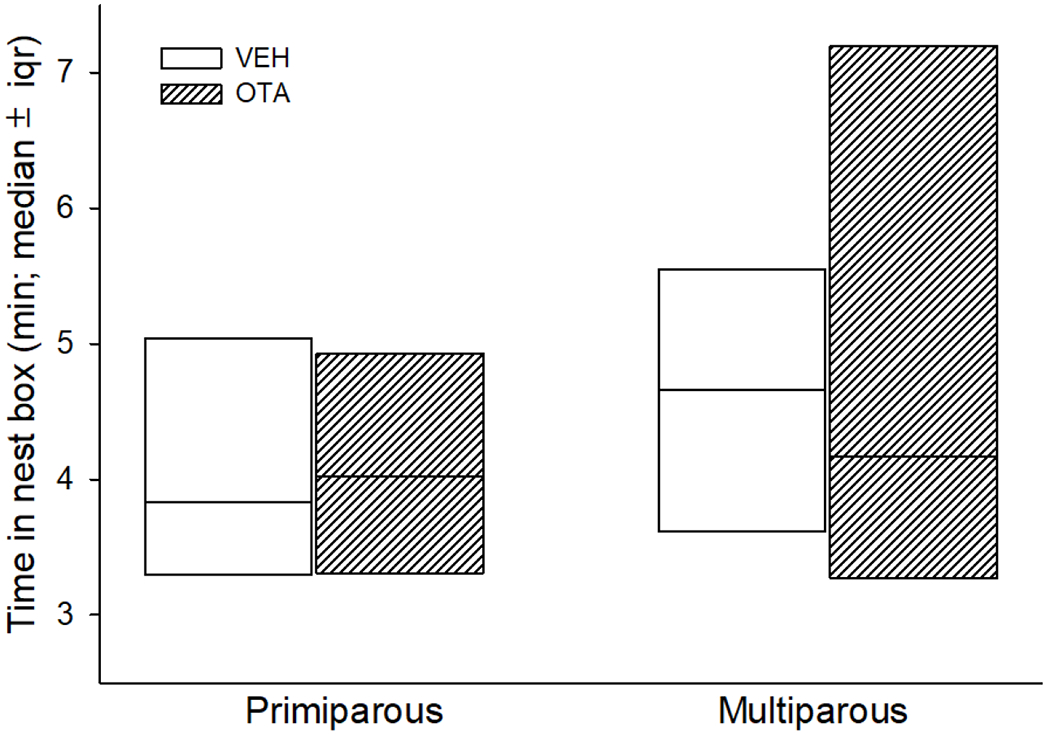

Fig. 2 shows the median values (±iqr) of the time inside the nest box shown by nursing does across postpartum days 1-3 in all groups. The data from these three days, of each nursing rabbit, were averaged to provide a single value that was then used in the two-way ANOVA. This test revealed no significant effects due to the injected agent [F(1, 53)=0.164, p=0.688], parity [F(1, 53)=3.193, p=0.080], or an interaction between these two factors [F(1, 53)=0.0589, p=0.809].

Fig. 2.

Time inside the nest box, nursing the litter (on lactation days 1, 2, 3), determined in primiparous and multiparous rabbits that received icv injections of OTA or VEH from gestation day 29 to lactation day 3. Primiparous-VEH (n=8), primiparous-OTA (n=31), multiparous-VEH (n=15), multiparous-OTA (n=12). Data show medians±interquartile ranges. A two-way ANOVA was used to compare, among the four experimental groups, the effects of: parity, injected agent and an interaction between these two factors.

Table 4 shows the total milk output determined across lactation days 1-3 in the four experimental groups. No significant differences were observed relative to parity [F(1, 53)=0.642, p=0.427] or agent injected ICV [F(1, 53)=0.0404, p=0.841]. No significant interactions occurred between these two factors [F(1, 53)=0.0955, p=0.759].

Table 4.

Total milk output across lactation days 1, 2, 3*

| Group | Grams of milk (median ± iqr) |

|---|---|

| Primiparous VEH (n=6) | 169.6 (112.9, 235.2) |

| Primiparous OTA (n= 26) | 158.95 (10.2, 266.1) |

| Multiparous VEH (n= 13) | 171.9 (67.1, 281.4) |

| Multiparous OTA (n= 9) | 172.7 (40.8, 299.8) |

Milk output was quantified on lactation days 1, 2, 3 in primiparous and multiparous rabbits that received icv injections of OTA or VEH from gestation day 29 to lactation day 3. The amounts obtained on each of these days (for each group) were added to determine a single value of total milk output. The median values (± iqr) were then calculated for each group. A two-way ANOVA of the original individual values was used to compare the effects of parity and agent injected icv.

Discussion

The daily icv injection of OTA from late pregnancy into early lactation did not significantly modify the appetitive (i.e., entrance into the nest box) or the consummatory (i.e., nursing) aspects of rabbit maternal behaviour. Moreover, the last stage of nest-building (i.e., hair-pulling), which started before parturition –but already under the influence of icv OTA-, occurred normally. These effects of the injected agent were true for both primiparous and multiparous does. Yet, an effect of parity was found on digging (larger values in multiparous does) and on the latency to enter the nest box, restricted to lactation day 2 (larger values in primiparous does). Thus, our results do not support a role of OXT for the initiation or the maintenance of maternal behaviour, regardless of previous maternal experience. Rather, our findings coincide with Rubin et al., (1983), who failed to stimulate maternal behavior in ovariectomized, steroid-primed virgin rats by icv infusion of OXT.

The lack of effects of icv OTA on rabbit maternal behaviour cannot be attributed to a failure of this antagonist to bind to the OXTR in the rabbit brain as our competitive autoradiography revealed high affinity and selectivity of OTA for OXR as reported in rodents. Regarding the dose, we gave daily icv injections of OTA (50 ng/day) from gestation day 29 to lactation day 3 and tested for maternal behavior at one hr post-injections on postpartum days 1-3. Lower doses (10-fold) of the same OTA have effectively inhibited oxytocin-dependent behaviors, including: partner preference in female prairie voles (5 ng icv; Insel and Hulihan, 1995), social recognition in male mice (1 ng, icv; Ferguson et al., 2001), consolation behavior in prairie voles (5 ng icv or 1 ng into the nucleus accumbens; Burkett et al., 2016), and partner preference in male prairie voles (5 ng icv; Johnson et al., 2016). Thus, the lack of effects of OTA on the occurrence and duration of nursing bouts in doe rabbits are unlikely to be due to an insufficient dose of OTA. Yet, it is possible that other aspects of rabbit maternal behavior (not explored in the present study), such as the circadian periodicity of nursing (González-Mariscal et al., 2013 a) may be modulated by OXT. Indeed, we found that kainic acid lesions of the rabbit PVN, made on lactation day 7, provoked either an abolishment of nursing or a disruption of its circadian periodicity, without modifying the duration of nursing bouts (Domínguez et al., 2017). While the former effect may have been due to a spread of kainic acid to areas essential for maternal behaviour, e.g. MPOA, the alterations in the timing of nursing bouts (with a maintenance of maternal motivation) are consistent with a modulatory role of OXT across lactation. Future studies should determine if the icv injection of OTA interferes with the circadian timing of rabbit nursing.

In lactating rats icv OTA injections do not abolish ongoing maternal behavior (Fahrbach et al., 1985), but such procedure does alter specific aspects of the dam’s interaction with her litter, e.g., the amount of licking and grooming (Champagne et al., 2001) and the adoption of a crouching posture for nursing (Pedersen and Boccia, 2003). Furthermore, lesions of the PVN performed in mid-pregnancy decrease pup retrieval and grouping as well as kyphotic nursing (Insel and Harbaugh, 1989), while radiofrequency lesions on lactation day 4 do not modify any aspect of maternal behavior (Numan and Corodimas, 1985), and kainic acid infusion on postpartum day 2 only reduces pup retrieval and nest-building (Olazábal and Ferreira, 1997). Taken together, this evidence has prompted the idea that endogenous OXT, presumably coming from the PVN, acts on the maternal brain –previously primed by the hormones of pregnancy- to promote the rapid onset of maternal behavior at parturition. Indeed, in primiparous sheep peridural anesthesia at the time of delivery (a procedure that blocks afferent stimulation from the birth canal and, consequently, OXT release) prevents the onset of maternal behavior; this effect is reversed by icv injections of OXT (Lévy et al., 1992). In contrast to rats and sheep, the maternal ethogram of rabbits has a gradual onset as nest-building starts already in early to mid-pregnancy (González-Mariscal et al., 1994). Consequently, the initiation of maternal behaviour is not temporally linked to parturition. Indeed, a “maternal state” is evident in the preoptic area already on postpartum day 1: regardless of the occurrence of nursing on such day, the number of c-FOS-immunoreactive cells in this region is much greater in mothers than in virgins (González-Mariscal et al., 2009). Moreover, a preference for kit odors (over “neutral” ones) is observed as early as gestation day 7, and continues into gestation day 28. Virgins do not show such preference (Chirino and González-Mariscal., 2015). Furthermore, the concentration of OTR observed in the preoptic area is higher in pregnant than in lactating does (Jiménez et al., 2015). Together, our results would suggest that either: a) the initiation of maternal behaviour in rabbits is not dependent on OXT or b) if this peptide is involved in promoting the onset of maternal behaviour, its action starts already in early- or mid-pregnancy, i.e., at a time when our animals were not given OTA. These reflections coincide with Yoshihara et al. (2017) who argue that the role of OXT in the initiation vs the maintenance of maternal behaviour, has been studied using a variety of methodologies, in different types of rodents, e.g.: wild, knockout, and inbred mice; rats; voles, under different testing setups. Such conditions preclude unequivocal conclusions regarding a “universal” role of OXT for the regulation of mammalian parental behavior.

On the other hand, there is evidence that OXT participates in the control of emotionality in mammals. During early lactation maternal aggression towards intruders and the defense of the young is high in rats (Bosch, 2013; Nephew et al., 2009), sows (Greenwood et al., 2019; Thomsson et al., 2015), and rabbits (Denenberg et al., 1958; Mugnai et al., 2009; Rödel et al., 2008). Ibotenic acid lesions of the PVN or infusion of antisense oligonucleotides against OXT into this nucleus increases maternal aggression in rats when these procedures are performed on the fifth, but not on the eighteenth, day of lactation (Giovenardi et al., 1998). Moreover, OTA infusions into the medial prefrontal cortex (prelimaternal behaviouric region) increased anxiety-like behavior and maternal aggression in early postpartum, but not in virgin, dams (Sabihi et al, 2014). Interestingly, rats selectively bred for high-anxiety behavior display more aggression against intruders, show higher levels of OXT release within the PVN and the central amygdala, and OTA infusions into either of these regions reduce maternal aggression in such dams (Bosch et al., 2005). Furthermore, late pregnant and lactating rats show lower levels of anxiety in the elevated plus maze than virgins; icv injections of OTA increase anxiety in peripartum rats (Neumann et al., 2000). Clearly, future studies should assess, in doe rabbits, maternal aggression and anxiety following icv injections of OTA, especially in regions rich in OXTR (e.g., prefrontal cortex, lateral septum).

The single icv injection of OTA on lactation days 1 to 3, one hour before testing, did not modify milk output in either primiparous or multiparous does. In rats there is evidence that a feed-forward mechanism enhances the pulsatile release of OXT, as suckling maintains OXT mRNA in magnocellular OXT-producing neurons, pup removal reduces its expression, and icv OXT infusion attenuates this effect (Moos et al., 1989; Neumann et al., 1993; Spinolo et al, 1992). Such a neuroendocrine organization would, theoretically, allow icv OTA infusions to reduce OXT release and, consequently, milk output. Whether a similar feed-forward mechanism operates in rabbits, that show a different nursing pattern from that of rats, remains to be determined.

Acknowledgements

LJY’s contribution was supported by NIH grants P50MH100023 and to LJY and OD P51OD011132 to ENPRC. AJ was supported by Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala, Mexico. GGM was supported by CINVESTAV (Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute), Mexico.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors confirm that researchers interested in viewing the data contained in this work can contact LY or GGM to this end.

References

- Basurto E, Hoffman KL, Lemus AC, González-Mariscal G 2018. Electrolytic lesions to the anterior hypothalamus-preoptic area disrupt maternal nest-building in intact and ovariectomized, steroid-treated rabbits. Horm. Behav 102:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ 2013. Maternal aggression in rodents: brain oxytocin and vasopressin mediate pup defence. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ, Meddle SL, Beiderbeck DI Douglas AJ, Neumann ID 2005. Brain oxytocin correlates with maternal aggression: link to anxiety. J. Neurosci 25:6807–6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ, Neumann ID 2008. Brain vasopressin is an important regulator of maternal behavior independent of dam’s trait or anxiety. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 105:17139–17143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkett JP, Andari E, Johnson ZV, Curry DC, de Waal FBM, Young LJ 2016. Oxytocin-dependen consolation behavior in rodents. Science 351:375–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caba M, Silver R, González-Mariscal G, Jiménez A, Beyer C 1996. Oxytocin and vasopressin immunoreactivity in rabbit hypothalamus during estrus, late pregnancy, and postpartum. Brain Res. 720:7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Ramírez H, Hoffman KL 2018. Activation of cortical and striatal regions during the expression of a naturalistic compulsive-like behavior in the rabbit. Behav. Brain Res 351:168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcea I, López Caraballo N, Marlin BJ, Ooyama R, Riceberg JS, Mendoza Navarro JM et al. 2021. Oxytocin neurons enable social transmission of maternal behavior. Nature 596:553–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ 2001. Naturally occurring variations in maternal behavior in the rat are associated with differences in estrogen-inducible central oxytocin receptors. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 98:12736–12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirino R, González-Mariscal G 2015. Changes in responsiveness to kit odors across pregnancy: relevance for the onset of maternal behavior. World Rabbit Sci. 23:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz ML, Beyer C 1972. Effect of septal lesions on maternal behavior and lactation in the rabbit. Physiol. Behav 9:361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denenberg VH Fromer GP, Sawin PB, Ross S 1958. Genetic, physiological and behavioral background of reproduction in the rabbit: IV. An analysis of maternal behavior at successive parturitions. Behaviour 13:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez M, Aguilar-Roblero R, González-Mariscal G 2017. Bilateral lesions of the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus disrupt nursing behavior in rabbits. Eur. J. Neurosci 46:2133–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrbach SE, Morrell JI, Pfaff DW 1985. Possible role for endogenous oxytocin in estrogen-facilitated maternal behavior in rats. Neuroendocrinology 40:526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Aldag JM, Insel TR, Young LJ 2001. Oxytocin in the medial amygdala is essential for social recognition in the mouse. J. Neurosci 21:8278–8285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froemke RC, Young LJ 2021. Oxytocin, neural plasticity, and social behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 44:359–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs AR, Cubile L, Dawood MY, Jorgensen FS 1984. Release of oxytocin and prolactin by suckling in rabbits throughout lactation. Endocrinology 114:462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs AR, Dawood MY 1980. Oxytocin release and uterine activation during parturition in rabbits. Endocrinology 107:1117–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs AR, Wagner G 1963. Quantitative aspects of release of oxytocin by suckling in unanaesthetized rabbits. Acta Endocrinol. 44:581–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovenardi M, Padoin MJ, Cadore LP, Lucion AB 1998. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus modulates maternal aggression in rats: effects of ibotenic acid lesion and oxytocin antisense. Physiol. Behav 63:351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis M, Shih-Chang W 1981. New stereotaxic atlas of the rabbit brain. Warren H. Green, Inc., St. Louis, MO. [Google Scholar]

- González-Mariscal G, Caba M, Martínez-Gómez M, Bautista A, Hudson R 2016. Mothers and offspring: the rabbit as a model system in the study of mammalian maternal behavior and sibling interactions. Horm. Behav 77:30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Mariscal G, Díaz-Sánchez V, Melo AI, Beyer C, Rosenblatt JS 1994. Maternal behavior in New Zealand white rabbits: quantification of somatic events, motor patterns and steroid plasma levels. Physiol. Behav 55:1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Mariscal G, Jiménez A, Chirino R, Beyer C 2009. Motherhood and nursing stimulate c-FOS expression in the rabbit forebrain. Behav. Neurosci 123:731–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Mariscal G, Lemus AC, Vega-González A, Aguilar-Roblero A 2013a. Litter size determines circadian periodicity of nursing in rabbits. Chronobiol. Int 30:711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Mariscal G, Poindron P 2002. Parental care in mammals: immediate, internal and sensory factors of control. In: Pfaff D, Arnold A, Etgen A, Fahrbach S, Rubin R, eds. Hormones, Brain, and Behavior. Academic Press, San Diego. pp. 215–298. [Google Scholar]

- González-Mariscal G, Sisto Burt A, Nowak R 2017. Behavioral and neuroendocrine indicators of well-being in farm and laboratory mammals. In: Pfaff D & Joëlls M, eds. Hormones, Brain and Behavior, 3d. ed. Elsevier, San Diego. pp. 454–485. [Google Scholar]

- González-Mariscal G, Toribio A, Gallegos-Huicochea JA, Serrano-Meneses MA 2013b. The characteristics of suckling stimulation determine the daily duration of mother-young contact and milk output in rabbits. Dev. Psychobiol 55:809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood EC, van Dissel J, Rayner J, Hughes PE van Wettere WHEJ 2019. Mixing sows into alternative lactation housing affects sow aggression at mixing, future reproduction and piglet injury, with marked differences between multisuckle and sow separation systems. Animals 9:658. Doi: 10.3390/ani9090658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Ford CL, Horie K, Young LJ. Oxytocin receptors are widely distributed in prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) brain: relation to social behavior, genetic polymorphisms, and the dopamine system. J. Comp. Neurol 2022, DOI: 10.1002/cne.25382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Harbaugh C 1989. Lesion of hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus disrupts the initiation of maternal behavior. Physiol. Behav 45:1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Hulihan TJ 1995. A gender-specific mechanism for pair bonding: oxytocin and partner preference formation in monogamous voles. Behav. Neurosci 109:782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Shapiro LE 1992. Oxytocin receptor distribution reflects social organization in monogamous and polygamous voles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5981–5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez A, Young LJ, Triana-Del Río R, La Prairie JL, González-Mariscal G 2015. Neuroanatomical distribution of oxytocin receptor binding in the female rabbit forebrain: variations across the reproductive cycle. Brain Res. 1629:329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ZV, Walum H, Jamal YA, Xiao Y, Keebaugh AC, Inoue K, Young LJ 2016. Central oxytocin receptors mediate mating-induced partner preferences and enhance correlated activation across forebrain nuclei in male prairie voles. Horm Behav. 79: 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy F, Kendrick KM, Keverne EB, Piketty V, Poindron P 1992. Intracerebroventricular oxytocin is important for the onset of maternal behavior in inexperienced ewes delivered under peridural anesthesia. Behav. Neurosci 106:427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertens L, Lebas F, Szendrő Zs. 2006. Rabbit milk: a review of quantity, quality and non-dietary affecting factors. World Rabbit Sci. 14: 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Misicka A, Olma A, Bankowski K, Stoev S, Chini B, Durroux T, Mouillac B, Corbani M, Guillon G 2012. Oxytocin and vasopressin agonists and antagonists as research tools and potential therapeutics. J. Neuroendocrinol 24:609–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlin BJ, Mitre M, D’Amour JA, Chao MC, Froemke RC 2015. Oxytocin enables maternal behavior by balancing cortical inhibition. Nature 520:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos F, Poulain DA, Rodríguez F, et al. (1989). Release of oxytocin within the supraoptic nucleus during the milk ejection reflex in rats. Exp. Brain Res 76:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnai C, Dal Bosco A, Castellini C 2009. Effect of different rearing systems and pre kindling handling on behaviour and performance of rabbit does. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci 118:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nephew BM, Bridges RS, Lovelock DF, Byrnes EM 2009. Enhanced maternal aggression and associated changes in neuropeptide gene expression in multiparous rats. Behav. Neurosci 123:949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann I, Russell JA, Landgraf R 1993. Oxytocina and vasopressin release within the supraoptic and paraventricular uclei of pregnant, parturiend and lactating rats: a microdialysis study. Neuroscience 53:66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID, Torner L, Wigger A 2000. Brain oxytocin: differential inhibition of neuroendocrine stress responses and anxiety-related behavior in virgin, pregnant and lactating rats. Neuroscience 95:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimori K, Young LJ, Guo Q, Wang Z, Insel TR, Matzuk MM 1996. Oxytocin is required for nursing but is not essential for parturition or reproductive behavior. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 93:11699–11704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan M, Corodimas K 1985. The effects of paraventricular hypothalamic lesions on maternal behavior in rats. Physiol. Behav 35:417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan M (2020). The Parental Brain: Mechanisms, Development, and Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Numan M, Young LJ 2016. Neural mechanisms of mother- infant bonding and pair bonding: similarities, differences, and broader implications. Horm. Behav 77:98–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olazábal D, Ferreira A 1997. Maternal behavior in rats with kainic acid-induced lesions of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Physiol. Behav 61: 779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Boccia ML 2003. Oxytocin antagonism alters rat dams’ oral grooming and upright posturing over pups. Physiol. Behav 80:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Vadlamudi SV, Boccia ML, Amico JA 2006. Maternal behavior deficits in nulliparous oxytocin knockout mice. Genes, Brain, Behav. 5:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling JK, Young LJ 2014. The biology of mammalian parenting and its effect on offspring social development. Science 345:771–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rödel HG, Starkloff A, Bautista A, Friedrich AC, Von Holst D 2008. Infanticide and maternal offspring defence in European rabbits under natural breeding conditions. Ethology 114:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin BS, Menniti FS, Bridges RS 1983. Intracerebroventricular administration of oxytocin and maternal behavior in rats after prolonged and acute steroid pretreatment. Horm. Behav 17:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabihi S, Dong SM, Durosko NE, Leuner B 2014. Oxytocin in the medial prefrontal cortex regulates maternal care, maternal aggression and anxiety during the postpartum period. Front. Behav. Neurosci 8:1. Doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinolo LH, Raghow R, Crowley WR 1992. Oxytocin messenger RNA levels in hypothalamic, paraventricular, and supraoptic nuclei during pregnancy and lactation in rats. Evidence for regulation by afferent stimuli from the offspring. Ann. NY acad. Sci 652:425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K 2005. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 102:16096–16101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsson O, Bergqvist AS, Sjunnesson Y, Eliasson-Selling L, Lundeheim N, Magnusson U 2015. Aggression and cortisol levels in three different group housing routines for lactating sows. Acta Vet. Scand 57:9. Doi 10.1186/s13028-015-0101-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leengoed E, Kerker E, Swanson HH 1987. Inhibition of post-partum maternal behavior in the rat by injecting an antagonist into the cerebral ventricles. J. Endocr 112:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara C, Numan M, Kuroda KO 2018. Oxytocin and parental behaviors. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci 35:119–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ 1999. Oxytocin and vasopressin receptors and species-typical social behavior. Horm. Behav 36:212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]