Abstract

After ablative surgery, especially a total maxillectomy, an obturator is commonly used as a method of reconstruction. However, the loss of a palatal denture-bearing area as well as vestibular retentive undercuts leave an anatomically deficient base on which to construct the definitive prosthesis. As a result, retention and stability is compromised. A solution to the retention problem is to construct an obturator that engages undercuts and scar bands. Engagement of all undercuts can lead to a prosthesis that is too cumbersome and difficult to insert, especially in a patient with scars after radiation. In this article, a technique for creating a 2-piece magnetic obturator that engages the nasal scar band is described.

INTRODUCTION

The goal of maxillofacial prosthetics is to restore function and esthetics to patients with maxillofacial defects. Some maxillary defects are a result of the surgical treatment of neoplasms.1 Any palatal defects, no matter how small, can cause difficulties in speech, mastication and esthetics. Obturators aid in recreating facial esthetics by physically supporting the cheeks and lips.2 Ideally, a patient with an acquired maxillary defect should be provided with an obturator that is comfortable, restores speech and mastication and has acceptable esthetics.3 For a patient with a maxillary defect, the clinician occasionally needs to modify or even violate some of the basic principles of prosthesis design. If the patient has a large defect, fabricating an adequately large obturator may not be possible because the patient is unable to insert the obturator through a small oral opening.3 If necessary, the prosthesis can be divided into 2 or more parts.

In designing a sectional prosthesis, function as well as the convenience of insertion and removal of a large prosthesis needs to be considered. The location of the contacting surfaces of the prosthesis sections should be determined by considering ease of fabrication and insertion. The defect undercut should not prevent the insertion of any section. Also, the division of the prosthesis into 2 parts should not compromise esthetics. Sectional prostheses may also be considered for patients with severe alveolar undercuts that prevent insertion and removal.4 A maxillofacial prosthesis should have a straightforward design and be easily manipulated by the patient.5

CLINICAL REPORT

A 67-year-old man with a history of a moderately differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the nasal cavity involving the left maxillary sinus and soft palate is presented. He reported being a former smoker: 2 packs per day for 50 years (100 pack years). In October 2011, a clinical examination revealed a 3-cm exophytic lesion involving the hard palate that extended into the nasal cavity and involved the anterior and inferior nasal septum. A biopsy the next month showed moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. A subsequent positron emission tomography (PET) scan revealed a hypermetabolic mass centered along the anterior hard palate and extending cephalad to the inferior nasal septum with no hypermetabolic activity in the neck or chest. In February 2012, the patient completed 37 fractions of radiation at an outside hospital (6700 cGy).

In October of 2012, the patient complained of persistent drainage from the nasal cavity, pain in the maxillary gingiva, and a foul smell, crusting, and occasional blood from the nasal cavity. A biopsy was performed and was positive for invasive and in situ SCC, moderately differentiated. In November 2012, a computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 9-mm nodule along the inferior nasal septum. The following month, the patient underwent a total maxillectomy. When this patient presented to our practice in July 2014, he had difficulty with speech and deglutition. His remaining tuberosities consisted of soft tissue only and were incapable of supporting his current obturator prosthesis. The prosthesis was lacking in retention and stability (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A, B, Initial presentation. Obturator lacking retention.

The patient’s maxillary defect included a scar band behind his nose that, if engaged, conflicted with the path of insertion and withdrawal. A 2-piece sectional prosthesis was designed (Fig. 2). First, an impression was made with a combination of polyvinylsiloxane impression material (Henry Schein) and irreversible hydrocolloid (Jeltrate; Dentsply Caulk). The 2 parts of this impression were made separately. The polyvinylsiloxane was placed in the anterior undercut and, once polymerized, was trimmed, keyed and replaced in position. The irreversible hydrocolloid impression was then made, and the 2 sections were luted together with baseplate wax (Fig. 3). The impression was then poured in Type III gypsum (Denstone Labstone Golden; Kulzer, Inc.) (Fig. 4).

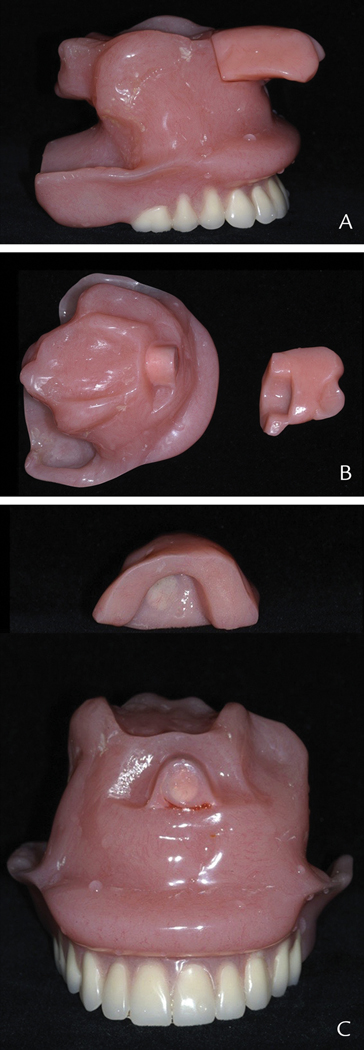

Figure 2.

Two-piece sectional obturator. A, Assembled. B, Sectioned. C, Magnets embedded in acrylic resin

Figure 3.

Definitive impression.

Figure 4.

Definitive cast.

Next, a hollow bulb obturator engaging both undercuts was processed in heat cured acrylic resin (Bosworth Impact 750; Keystone Industries). In this state, there was no path of insertion, and the patient was unable to insert the prosthesis. To rectify this problem, the anterior portion of the prosthesis was sectioned and neodymium magnets (K&J Magnetics) were incorporated into the acrylic resin. To finalize the prosthesis, conventional denture methods including an occlusal rim, interocclusal record, wax set-up, evaluation for esthetics and phonetics, and denture processing were followed.

“The force between two magnet poles is proportional to the strength of each pole and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the poles.”6 Therefore, when each obturator magnets was in the magnetic field of the other, the prosthesis could glide easily into place.7

DISCUSSION

The resection of a malignant lesion involving the maxilla can produce severe oromaxillary defects that will significantly jeopardize the patient’s normal daily function. A prosthesis is commonly placed into the palatal defect immediately after a total maxillectomy. Immediate insertion of a prosthesis prevents contracture, maintains the facial contours and enables the patient to eat a soft diet. This helps the patient continue his usual neuromuscular pattern in terms of speech, mastication and deglutition. In addition, the immediate prosthesis provides a matrix for packing, reduces oral contamination of the surgical site, and is also psychologically advantageous as opposed to leaving the patient with no prosthesis and thus an open defect.8

When a patient undergoes radical maxillary surgery, it frequently creates a situation in which a unitary structure of a maxillary denture and obturator is too large to be inserted orally.9 In such patients, a 2-piece sectional prosthesis should be considered. Structures within the residual maxilla and the acquired defect must be evaluated for prosthesis retention.3 Direct retention as well as indirect retention are of paramount importance. If the remaining maxillary segment is edentulous, securing retention for the prosthesis is more difficult than in a dentate patient.3 The retentive capabilities of the residual maxillary segment must be evaluated using the same factors that contribute to the acceptable retention of a conventional complete denture including the physical properties of adhesion, cohesion, atmospheric pressure and interfacial surface tension.3

Anterior extension of the obturator provides some resistance to vertical displacement of the anterior portion of the prosthesis. This extension competes for insertion and removal with the extension over the soft palate.3 It is therefore necessary to construct the prosthesis as 2 separate parts and assemble them intraorally.9 In this report, the anterior segment was small. The patient was given detailed instructions on how to insert and remove the sections of the prosthesis so as not to aspirate or swallow the small segment. The patient placed the small segment behind his nose and then inserted the larger segment to engage the magnets. For removal, he leaned forward and removed the larger segment followed by the smaller one. Once assembled, dislodgement of the anterior segment was not a concern as there was physically no room for displacement once the larger segment was in place.

Magnets have been used for the retention, maintenance and stabilization of maxillofacial prostheses.5,7,10 Various types of magnets have been used to connect segments of a sectional prosthesis. A technique that included magnets between an obturator and maxillary denture was presented in 1966 by Boucher and Heupel.11 In 1970 Chalian and Barnett12 introduced a technique for constructing a hollow obturator using an autopolymerizing acrylic resin. Robinson10 used horseshoe magnets to retain a maxillary denture and obturator for a patient with a complete maxillectomy. Nadeau5,13 used magnets to improve the retention of the definitive obturator and facial prosthesis.14

Magnets provide positive locking potential and, once in position, provide consistent retentive qualities.10 Magnet size and diameter can be selected according to the size of the defect and prosthesis.7 Over time, improvements have been made in the corrosion resistance and attractive forces of the magnets used for dental applications. Such improvements have helped reduce their size and expand their application.14

SUMMARY

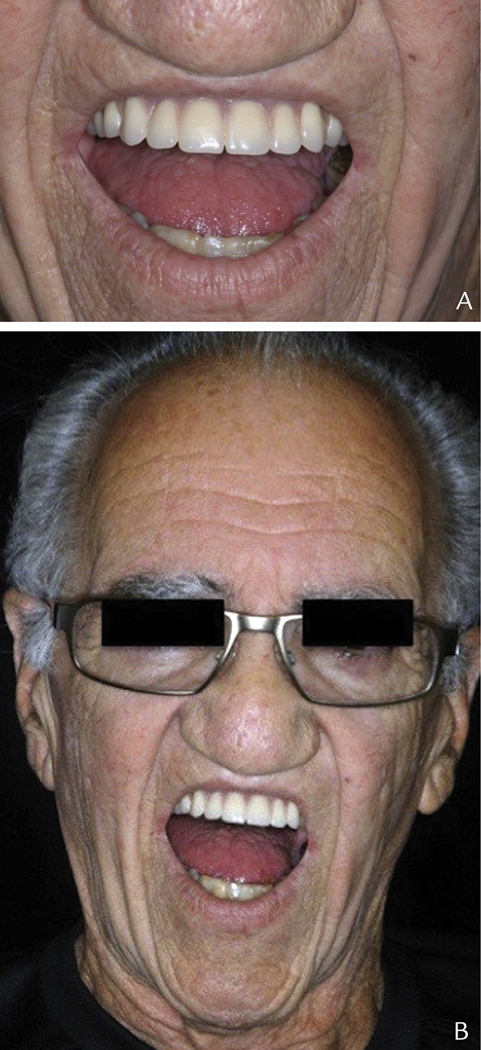

With the incorporation of neodymium magnets, the patient was able to insert and remove the prosthesis, which included the engagement of the anterior and posterior undercuts without difficulty. The ability to engage both undercuts resulted in increased retention and stability as well as improved speech and deglutition. (Fig. 5). This patient continued to be followed and, at each recall appointment, expressed his satisfaction with his prosthesis and extreme gratitude that his chief complaint had been addressed.

Figure 5.

A, B, Definitive obturator with improved retention.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aramany MA. A history of prosthetic management of cleft palate: Pare to Suersen. Cleft Palate J 1971;8:415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalian VA, Drane JB, Standish SM. Maxillofacial prosthetics – multidisciplinary practice, Baltimore. The Williams & Wilkins Company; 1972. p.121–57.

- 3.Desjardins RP. Obturator prosthesis design for acquired maxillary defects. J Prosthet Dent 1978;39:424–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasaki H, Kinouchi Y, Eng D, Tsutsui H, Yoshida Y, Karv M, et al. Sectional prostheses Connected by Simarian Cobalt Magnets. J Prosthet Dent 1984;52:556–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadeu J. Maxillofacial prosthetics with magnetic stabilizers. J Prosthet Dent 1956;6:114–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinney LB. A Textbook of Physics. The Macmillan Company; 1947. p.299–315.

- 7.Javid N. The use of magnets in a maxillofacial prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent 1971;25:334–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha V, Bhowate RR, Raizada RM, Jain SKT, Chaturvedi VN. Placement of prosthesis after total maxillectomy in edentulous patient. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999; 52:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter JD. Anchor attachments used as locking devices in two-part removable prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 1975;33:628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson JE. Magnets for retention of a sectional intraoral prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent 1963; 13:1167–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boucher L, Heupel E. Prosthetic restoration of a maxilla and associated structures. J Prosthet Dent 1966;16:154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalian V, Barnett M. A new technique for constructing a one-piece hollow obturator after partial maxillectomy. J Prosthet Dent 1970;28:448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadeau J. Special prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 1968; 20:62–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federick DR. A magnetically retained interim maxillary obturator. J Prosthet Dent 1976;36:671–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]