Abstract

Study objectives:

The objectives of this study were to characterize the detailed cannabis use patterns (eg, frequency, mode, and product) and determine the differences in the whole-blood cannabinoid profiles during symptomatic versus asymptomatic periods of participants with suspected cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome recruited from the emergency department (ED) during a symptomatic episode.

Methods:

This is a prospective observational cohort study of participants with symptomatic cyclic vomiting onset after chronic cannabis use. Standardized assessments were conducted to evaluate for lifetime and recent cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and cannabis withdrawal symptoms. Quantitative whole-blood cannabinoid testing was performed at 2 times, first when symptomatic (ie, baseline) and at least 2 weeks after the ED visit when asymptomatic. The differences in cannabinoid concentrations were compared between symptomatic and asymptomatic testing. The study was conducted from September 2021 to August 2022.

Results:

There was a difference observed between delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites, but not the parent compound during symptomatic episodes and asymptomatic periods. Most participants (84%) reported using cannabis > once per day (median 3 times per day on weekdays, 4 times per day on weekends). Hazardous cannabis use was universal among participants; the mean cannabis withdrawal discomfort score was 13, indicating clinically significant rates of cannabis withdrawal symptoms with cessation of use. Most participants (79%) previously tried to stop cannabis use, but a few (13%) of them had sought treatment.

Conclusion:

Patients presenting to the ED with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome have high cannabis use disorder scores. Further studies are needed to better understand the influence of THC metabolism and concentrations on symptomatic cyclic vomiting.

INTRODUCTION

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (ie, cyclic vomiting occurring in the context of chronic cannabis use) has been recognized for nearly 2 decades.1–4 People with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome symptoms (eg, intractable vomiting and pain) most frequently present to emergency departments (EDs) for care, with some requiring hospitalization. Despite the increasing reports of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, substantial gaps in understanding the cause of the syndrome remain. Existing literature is dominated by case reports and retrospective studies with limited longitudinal follow-ups, detailed descriptions of cannabis use patterns, or clear case definitions, most importantly whether cyclic vomiting started before cannabis use.

Trends in increasing ED visits for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome symptomatology coincide with the increases in delta-9-THC (THC) concentrations in cannabis products and the legalization of recreational cannabis.1,2,5 In 2000, the average THC content of a joint was 5%, whereas most cannabis strains sold in dispensaries today have a THC content of above 20%.6,7 The chronic use of high percentage of THC products is known to be associated with a higher risk of adverse effects, including the increased levels of physiologic dependence, affective disturbances, and development of cannabis use disorder and cannabis withdrawal.8–10 To date, no threshold quantity, the frequency of cannabis use, or clear lag time between the initiation of use and the onset of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome have been identified. The only reported cure for cannabis-related cyclic vomiting episodes is the cessation of cannabis use.11–13

We conducted, to our knowledge, the first prospective study with longitudinal follow-ups of patients with chronic cannabis use with cyclic vomiting recruited from the ED at the time of symptomatic vomiting. This article describes the recent and historical patterns of cannabis use (ie, percentage of THC, quantity, frequency, and mode), characterizes the overlap of cannabis-related cyclic vomiting with cannabis use disorder and cannabis withdrawal, and provides the first profile of whole-blood cannabinoids comparing symptomatic and asymptomatic time periods. We hypothesized that individuals with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome will report the frequent use of high-percentage THC cannabis products and have high cannabis use disorder and cannabis withdrawal scores and that acute episodes would be associated with higher THC: cannabidiol (CBD) ratios than asymptomatic periods.

METHODS

Overview

A prospective cohort of patients presenting to the ED with symptomatic cyclic vomiting who reported daily cannabis use (n=39) were enrolled at the time of the ED visit at 2 hospitals within the Rhode Island health care system (one community and one tertiary care setting) with follow-ups conducted at the same sites. This article presents the baseline data obtained at the time of enrollment including validated questionaries assessing cannabis use (daily sessions, frequency, age at onset, and quantity of cannabis use inventory)14, problematic cannabis use (cannabis use disorder IT-R),15 and cannabis withdrawal (Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist)16 and baseline and follow-up whole-blood cannabinoid testing results. Study participants were followed up for 3 months. Other works will describe the 3-month longitudinal course.

Eligibility and Enrollment

Research assistants screened a consecutive sample of participants daily (7:00 AM–11:00 PM). Research assistants identified the potential participants using the emergency department track board chief complaints (eg, emesis, vomiting, hyperemesis, cyclic vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain, epigastric pain, drug screening, cannabis hyperemesis, and cannabis), electronic health record reviews, and direct referral from an emergency department treating teams. The research assistant checked the eligibility criteria with the attending physician and then confirmed it in person with the patient. The determination of alcohol use disorder, clinical stability, and/or the presence of a more likely alternate cause was made by the treating physician.

Eligible individuals were (1) English-speaking, (2) aged ≥18 years, (3) had a positive urine toxicology immunoassay for THC on the ED visit, and (4) met the study cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome diagnostic criteria. The following diagnostic criteria were: (1) severe, cyclic vomiting (ie, ≥2 episodes within 6 months before the index ED visit), (2) epigastric or periumbilical abdominal pain, (3) chronic, daily cannabis use (>20 days per month; duration ≥ year), and (4) onset of cyclic vomiting after the initiation of cannabis use.12,17,18

Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, were clinically unstable, were in police custody or incarcerated, had positive ED urine toxicology tests for non-prescribed drugs besides THC, had active suicidal thoughts, or had an alcohol use disorder as determined by the emergency physician. Patients with overlapping disease processes or alternate diagnoses that could account for vomiting symptoms (eg, inflammatory bowel disease) were also excluded after consultation with the treating physician. The 2 cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome diagnostic criteria of (1) hot water bathing to relieve symptoms and (2) the elimination of symptoms on cannabis cessation were recorded but not required for eligibility because the evidence related to hot water bathing to relieve the symptoms is inconclusive,18–20 and the recruitment of symptomatic participants from the ED negated our ability to recruit patients who had stopped using cannabis. We present data from the enrollment ED visit and a two-week follow-up.

Data Collection

Baseline demographic information obtained by the patient report was recorded at the index ED visit. Self-reports of mood and psychiatric illness were recorded. Participants completed the Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised15 and the Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist (Behavioral Checklist Diary)21 to screen for cannabis use disorder and cannabis withdrawal, respectively. The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised is an 8-item scale designed for self-administration. Scores of 8 or more indicate hazardous cannabis use, and scores of >12 indicate a possible cannabis use disorder. The Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist is a 15-item self-report measure of symptoms with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severe), with 10 items making up a withdrawal discomfort score. Participants completed the full 15-item marijuana withdrawal checklist measure, which includes the common and frequently observed cannabis withdrawal symptom items: craving for marijuana, depressed mood, decreased appetite, increased aggression, increased anger, headache, irritability, nausea, nervousness/anxiety, restlessness, shakiness, difficulty in sleeping, stomach pains, strange dreams, and sweating. The withdrawal discomfort score reported in this study is a subscale that includes 10 items of the 15-item marijuana withdrawal checklist questionnaire as follows: anger, craving for marijuana, depressed mood, decreased appetite, headaches, irritability, nervousness, restlessness, difficulty in sleeping, and strange dreams.16,22 Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. Recent and lifetime histories of cannabis use were documented and included their mode(s), type(s), amount, and percent of THC (if known) and were evaluated using the daily sessions, frequency, age at onset, and quantity of cannabis use inventory.14

The toxicological assessment of whole-blood cannabinoids and metabolites was performed during the initial ED visit, when the participants were experiencing active cyclic vomiting, and repeated at 2 weeks or, if still symptomatic at 2 weeks, at the time of symptom resolution. High-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry detection (LC/MS/MS) cannabinoid panel including delta-9-THC (THC), 11-hydroxy-delta-9-THC, 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-THC, cannabigerol (CBG), cannabidiol (CBD), and cannabinol (CBN) was performed. Whole-blood high-performance LC/MS/MS was chosen over urine because whole-blood is a more accurate marker of recent use when compared with urine.23 Medical histories including specific questions about the kidney and liver functions, active medications, body mass index (BMI), and time since last cannabis use at the sample collection were also recorded.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted using SAS 9.4. Continuous data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges, and categorical data are presented as proportions. This study was approved by the Lifespan Institutional Review Board. Patients or public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans for this project.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

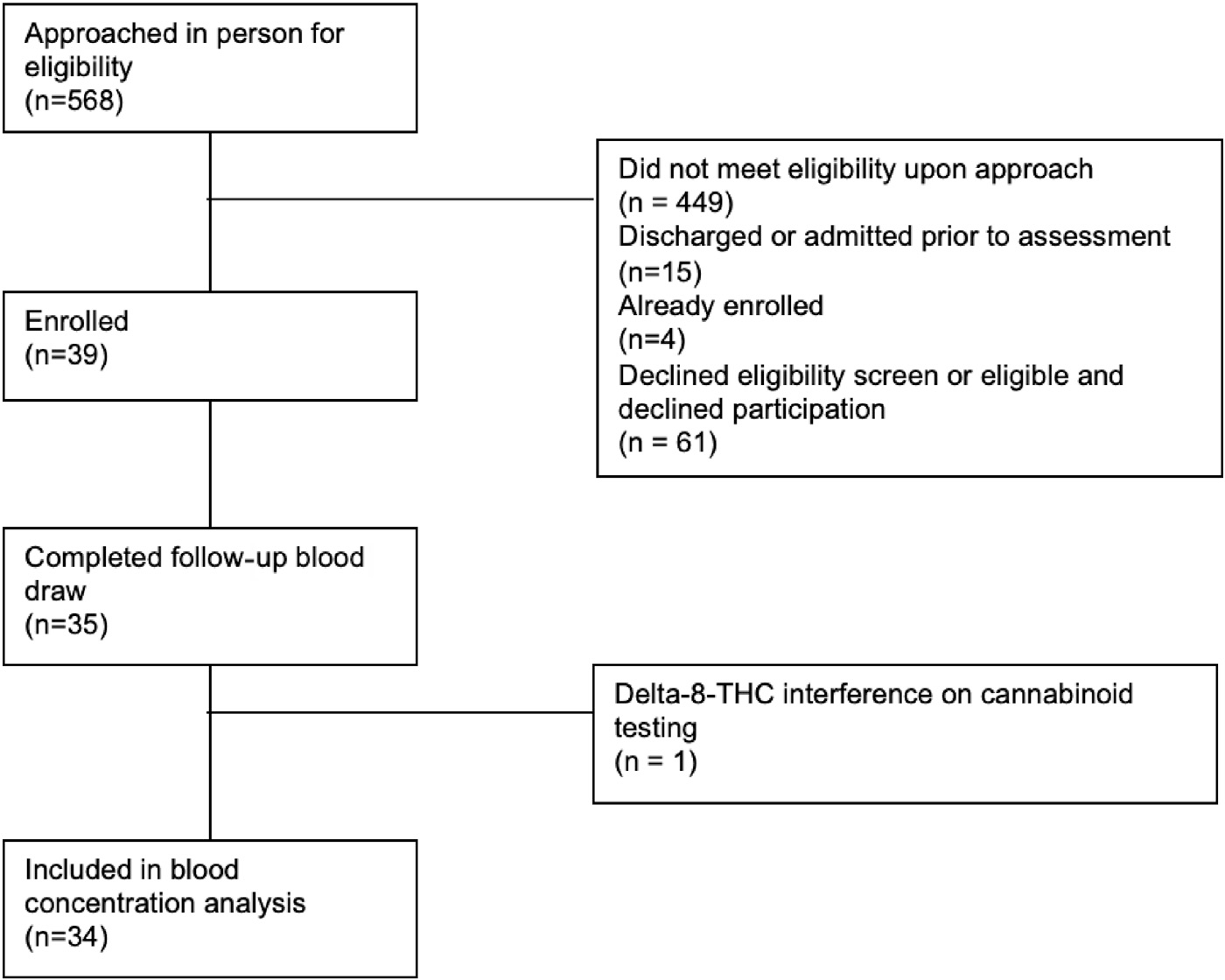

A total of 568 patients were approached for eligibility after the initial electronic health record review, and 39 were enrolled. Further details are provided in a consort diagram in Figure. Of the participants who declined the study participation, a urine drug screen was rarely performed; therefore, full eligibility could not be determined. One participant withdrew from the study after the completion of the baseline assessments. The DFAQ-CU survey was incompletely filled out for one participant; for that participant, the values were left missing. Cannabinoid analyses were limited to the 35 individuals who completed the initial and follow-up blood draws. Demographic data are outlined in Table 1. Approximately 67% of the participants reported having at least one mental health comorbidity, with 56% and 54% reporting anxiety and depression, respectively.

Figure.

Patient recruitment and follow-up flowchart.

Table 1.

Demographics of ED patients with cannabis-related cyclic vomiting (n=39).

| Characteristic | n (%) or Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (y) | 26.6 (21.2, 32.2) |

| BMI | 26.5 (21.4, 33.1) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 16 (41%) |

| Women | 21 (54%) |

| Non-binary or genderqueer | 2 (5%) |

| Race | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 1 (3%) |

| White | 20 (51%) |

| Black | 12 (31%) |

| Multiple race | 3 (8%) |

| Other | 2 (5%) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (3%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 10 (26%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 28 (72%) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 32 (82%) |

| Married | 5 (13%) |

| Unmarried, living with a partner | 2 (5%) |

| Housing status | |

| House | 11 (28%) |

| Apartment | 20 (51%) |

| Friend or family’s place | 8 (21%) |

| Employment | |

| Full time | 20 (51%) |

| Part time | 10 (26%) |

| Unemployed | 8 (21%) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2%) |

| Education | |

| Some high school | 5 (13%) |

| High school | 25 (64%) |

| Trade school | 3 (8%) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 6 (15%) |

| Self-report of mood and psychiatric illness | |

| Anxiety disorder | 22 (56%) |

| Depression | 21 (54%) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 7 (18%) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 7 (18%) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 3 (8%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 3 (8%) |

| Personality disorder | 1 (3%) |

| None | 13 (33%) |

Cannabis Use Patterns

All participants had Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised scores consistent with either cannabis use disorder (74%) or hazardous cannabis use (26%) (Table 2). Almost all participants endorsed high cannabis withdrawal scores on the withdrawal discomfort score indicating severe symptoms. Most patients (79%) had tried to stop cannabis use, but a few (13%) of them had sought treatment. Thirty-seven participants reported symptom relief with hot water bathing.

Table 2.

Cannabis use disorder and cannabis withdrawal scores (N=39).

| n (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Cannabis use disorder | |

| Cannabis use disorder | 29 (74%) |

| Hazardous cannabis use | 10 (26%) |

| Ever tried to stop using cannabis | 31 (79%) |

| Ever sought treatment for cannabis | 5 (13%) |

| Cannabis withdrawal discomfort score | 13 (8, 18) |

Table 3 provides descriptive data on cannabis use history and patterns. Cannabis use before the age of 16 years was reported in 72% of the participants, with 24% of the participants reporting daily or multiple times per day use. No participants endorsed using edibles as the primary form of use. Over a third of the participants could not estimate their THC content. Of the participants who reported the THC content in their cannabis products, 58% estimated the THC content to be between 20% or greater. Most participants (84%) also reported using cannabis more than once per day, with a median of 3 times per day on weekdays and 4 times per day on weekends. Half of the participants reported cannabis use within one hour of waking up in the morning.

Table 3.

Cannabis use history and patterns of use (n=39).

| n (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age when started using cannabis (y)† | 15.7 (13.8, 18.0) |

| Age first daily cannabis use (y)* | 18.4 (16.0, 21.3) |

| Time from start daily use to development of cyclic vomiting (y)* | 4.7 (1.8, 8.8) |

| Frequency of cannabis use before age 16* | |

| Never | 11 (29%) |

| 1–4 times per y | 11 (29%) |

| Once a month | 2 (5%) |

| 2–6 times per week | 6 (16%) |

| Once a day | 0 |

| More than once a day | 8 (21%) |

| Frequency of current cannabis use* | |

| More than once a day | 32 (84%) |

| Once a day | 4 (10%) |

| 5 – 6 times per week | 1 (3%) |

| 3 – 4 times per week | 1 (3%) |

| Days past month cannabis use | 29 (25, 30) |

| Number use sessions per day on typical weekday use cannabis | 3 (2, 4) |

| Number use sessions per day on a typical weekend use cannabis | 4 (3, 5) |

| Time from waking up to cannabis use* | |

| Immediately | 3 (8%) |

| Within 30 minutes | 12 (31%) |

| Within 1 hour | 4 (10%) |

| 1 – 3 hours | 13 (33%) |

| 3–6 hours | 2 (5%) |

| 6–9 hours | 3 (8%) |

| 12–18 hours | 1 (3%) |

| Primary method of cannabis use | |

| Blunts | 18 (46%) |

| Bong | 6 (15%) |

| Joint | 9 (23%) |

| Vaporizer | 2 (5%) |

| Other | |

| Spliff | 2 (5%) |

| Dab | 2 (5%) |

| Primary form of cannabis use | |

| Marijuana (flower) | 35 (90%) |

| Concentrates | 4 (10%) |

| Average THC content of cannabis used | |

| 0%–9% | 2 (5%) |

| 10%–19% | 8 (21%) |

| 20%–30% | 12 (31%) |

| Greater than 30% | 2 (5%) |

| Unknown average | 15 (38%) |

| Source of cannabis* | |

| Non-dispensary (eg, dealer, seller) | 21 (54%) |

| Legal dispensary (medical) | 5 (13%) |

| Legal dispensary (recreational) | 10 (26%) |

| Other | 2 (5%) |

Data missing for one participant (n=38).

Data missing for 2 participants (n=37).

Cannabinoid Blood Analysis

For all participants, the median time from the last cannabis use to blood draw during the index ED visits was 26 hours (IQR: 15,51) versus 11 hours (IQR: 3,36) on repeat blood draw. Median days from the enrollment to the follow-up blood draw was 15 days (IQR: 15,19). At the asymptomatic follow-up visit, most participants (86%) reported return to active use (ie, use within the 24 hours preceding blood draw). No participants had significant kidney or liver disease based on the kidney and liver functions at the time of enrollment.

Delta-8-THC was detected on the initial and follow-up blood draws in one participant. Although the testing laboratory did not specifically test for delta-8-THC, they were able to identify it as an interfering substance and reported its presence. These testing results were excluded from the analysis because the interference caused by delta8-THC made it impossible to accurately quantify delta-9-THC and its metabolites leaving n=34 for the final analysis. Differences from symptomatic to asymptomatic testing for delta-9-THC and its metabolites 11-hydroxydelta-9-THC and 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-THC were compared. No differences were identified for the parent compound delta-9-THC. However, we did see increases in the cannabinoid metabolites 11-hydroxy-delta-9-THC and 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-THC on follow-ups compared with baseline (Table 4). CBD concentrations were undetectable in all study samples. Detailed cannabinoid concentration data for participants can be accessed in Appendix E1 (available at http://www.annemergmed.com).

Table 4.

Comparison of whole-blood cannabinoid concentrations during symptomatic episodes and asymptomatic periods in 34 participants with cannabis-related cyclic vomiting.

| Symptomatic Baseline |

Asymptomatic Follow-up |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Median (IQR) | Mean (95% CI) | Median (IQR) | |

|

| ||||

| Delta-9-THC | 9.3 (2.4, 16.1) | 5.6 (3.3, 9.7) | 9.9 (6.4, 13.3) | 5.8 (2, 14) |

| 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-THC* | 69.6 (50.1, 89.2) | 58.0 (28,82) | 91.3 (61.6, 121.0) | 71.0 (31, 135) |

| 11-hydroxy-delta-9-THC* | 2.3 (1.5, 3.2) | 1.6 (1,0, 3.4) | 4.7 (2.8, 6.5) | 3.2 (0,7.2) |

Statistically significant differences were found in THC-metabolite concentrations using t-tests and signed-rank tests.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective observational study of ED patients with cyclic vomiting associated with chronic cannabis use, hazardous cannabis use was universal among participants. Most participants reported using cannabis more than once per day (84%) (median 3 times per day on weekdays and 4 times per day on weekends) and had previously tried to stop cannabis use (79%), but only a few (13%) of them had sought treatment. On whole-blood cannabinoid testing, no differences were observed in delta-9-THC whole-blood concentrations during symptomatic and asymptomatic episodes, but higher concentrations of delta-9-THC metabolites were found during asymptomatic periods.

In contrast to the existing cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome literature, through a prospective design, we were able to exclude co-substance use and plot the time course of cyclic vomiting compared with daily cannabis use initiation. Previous work on the population-level cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome data and retrospective study of ED patients are limited by the confounders and lack of specificity in the cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome case definition because there is no ICD code that clearly identifies cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.24 Most previous studies omit the evaluation of whether cyclic vomiting episodes started before or after chronic cannabis use, simply reporting cyclic vomiting in individuals with chronic cannabis use. When enrolling in our study, we screened out patients with chronic cannabis use and cyclic vomiting who started using cannabis to treat their nauseavomiting episodes.

In our study (median age, 26.6 years), 92% of the participants reported a period of daily use before ever experiencing cyclic vomiting; the remainder reported multiple times per week use. Before the study enrollment ED visit, all participants reported >1 year chronic daily use (>20 days per month). Multiple times per day use practices, as seen in 84% of our study participants at the time of enrollment, likely carry different risks for adverse effects than one time per day daily use. However, both patterns would fit the definition “daily use.” The average reported that the percentage of THC ranges in this study generally reflects the percentage of the THC present in cannabis products currently available in the United States.25 Data suggest that cannabis with higher percentages of THC is associated with a higher risk for adverse effect; however, the definition of “high potency” in studies is often variable and inaccurate.10 Potency is an expression of the activity of a drug in terms of the concentration or amount required to produce a defined effect. A high percentage of THC in a cannabis product is a change in formulation, which may lead to higher doses, but this does not represent a change in potency.26 From 2011 to 2021, daily cannabis use has increased from 6% to 11% among young adults (aged 18–35 years) in the United States, although the amount consumed is not well described.27 These findings underscore the need for more relevant assessments of cannabis use, improved accuracy in terminology, and more precise assessments of the dose.

Previous studies have surveyed individuals with cyclic vomiting syndrome and documented the cannabis use practices and incidence of cannabis use disorder comparing individuals with chronic frequent cannabis use (>4 days/week) with those with occasional or no use.20,28 However, these studies do not include the details on the time course of cyclic vomiting syndrome development relative to the onset of frequent chronic cannabis use, which complicates the result interpretation and limits the application to the cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome populations. Cannabis use disorder presents a challenge when making treatment recommendations for cessation of cannabis use. Currently, no pharmacotherapies have been FDA approved for the treatment of cannabis use disorder or cannabis withdrawal,29 with behavioral interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and contingency management considered first line.

Mental health illness was reported by 67% of the participants at the time of enrollment, with 54% reporting depression and 56% reporting anxiety, which align with a recent survey-based study.28 This finding is similar to the high co-morbidity of mental health conditions seen in both individuals with cannabis use disorder and those diagnosed with cyclic vomiting not related to cannabis use. Previous studies have used the lack of mental health conditions as a factor to differentiate cyclic vomiting syndrome from cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.30 The finding of high mental health co-morbidity in our study challenges this assumption. The high burden of anxiety and depression seen in this study population aligns with previous treatment data that demonstrate superior efficacy of dopamine antagonists, such as haloperidol and benzodiazepines to treat symptomatic episodes over more typical antiemetics.31–33

Biological cannabinoid concentrations of the parent compound delta-9-THC did not vary between symptomatic episodes and asymptomatic periods. However, despite a shorter median time from the last cannabis use to blood draw, we found higher concentrations of 11-hydroxy-delta-9-THC and 11-nor-9carboxy-delta-9-THC, psychoactive and non-psychoactive metabolites, respectively, on repeat asymptomatic blood draws. The cause of this finding is unclear; it could be because of the blood collection occurring outside the window of acute intoxication or may be because of the impaired metabolism34 or the increased release of built-up stores of delta-9-THC during symptomatic cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome episodes. Chronic frequent exposure to cannabis results in the storage of a large body burden of THC because cannabinoids are highly lipophilic and readily undergo redistribution into tissues.35,36 Relatedly, biologic cannabinoid testing can remain elevated in people who chronically use cannabis daily for weeks since the last use because of the prolonged elimination phase, further complicating the interpretation of cannabinoid concentrations.23,37–39 It has been previously theorized that stress and fasting states can precipitate cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome episodes by causing acute spikes in blood delta-9-THC because of the increased release from fat stores.40,41 Furthermore, the interplay between cannabinoid and endovillanoid systems in response to stress including upregulation at the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptors and downregulation at the CB1 receptor, or alterations in regulation of the hypothalamic pituitary access by cannabinoids,42 could account for gastrointestinal hyperalgesia and cyclic vomiting.43–45 Similarly, it has been hypothesized that chronic exposure to high concentrations of THC may overstimulate cannabinoid type 1 receptors (CB1) eventually exceeding an individual threshold and facilitate desensitization or downregulation of CB1 receptors in the central nervous system resulting in the reversal of typical central antiemetic properties of cannabis.46–49

We found a wide variation in delta-9-THC and metabolite concentrations across the study cohort. This is consistent with that found in the previous literature evaluating cannabis concentrations in individuals with a history of chronic cannabis use. In one study of 25 individuals with frequent, long-term cannabis use observed on a secure 24/7 medical surveillance unit, 9 individuals had no measurable delta-9-THC concentrations in whole blood during the 7 days of cannabis abstinence. However, 6 days after entering the closed unit, 6 participants continued to have whole-blood detectable delta-9-THC concentrations.38 In another study, the presence of delta-9-THC in the blood was documented for up to 33 days after the last cannabis intake in individuals with frequent use.50 In both these studies, some individuals had interspersed negative and positive THC concentrations reflecting the high body burden of THC because lipophilic THC is stored in the fat and released into the blood over time. One individual in our study had an initial whole-blood delta-9-THC cannabinoid concentration of 119 ng/mL. This amount of variation in delta-9-THC concentrations among individuals with daily chronic cannabis is similar to the results of a recent study of individuals with daily cannabis use. Furthermore, consistent with our study, in that study, the median baseline delta-9-THC blood concentration was 6.4 ng/mL, and nearly half of the 30 subjects had blood cannabinoid baseline testing results <5 ng/mL.51

A previous study that compared hair cannabinoid concentrations between individuals with suspected cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome and a control group with chronic cannabis use but not cyclic vomiting found no difference in cannabinoid concentrations between individuals with heavy cannabis use with and without cyclic vomiting.52 Furthermore, similar to our study, CBD concentrations were unquantifiable in all participants. This is not unexpected because the pharmacokinetic studies demonstrate that cannabinoids CBN, CBD, and CBG do not remain detectable in biological fluids as long as delta-9THC and its metabolites remain.23 The only other study to our knowledge that has evaluated biological cannabinoid concentrations in patients with suspected cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome documented urine 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-THC concentrations in 15 patients diagnosed with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome in a pediatric gastroenterology specialty practice. Although important for documenting cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, the study design did limit the ability to report a range of symptoms and substances other than 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-THC.53

LIMITATIONS

Given that the hallmark of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome diagnosis is the resolution of symptoms on the cessation of use and that most patients are diagnosed as suspected cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome from the ED during a period of ongoing cannabis use, differentiating cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome cases from cyclic vomiting syndrome cases with chronic cannabis use from the ED is challenging. Our inclusion criteria addressed this limitation by excluding patients who reported the onset of cyclic vomiting before the initiation of cannabis use and patients with overlapping disease processes or alternate diagnoses that could account for vomiting symptoms (eg, inflammatory bowel disease) after consultation with the treating physician. Cannabis withdrawal symptoms were documented using a validated marijuana withdrawal checklist, which includes the symptoms listed in DSM-V cannabis withdrawal syndrome. To our knowledge, this is the first time that marijuana withdrawal checklist survey results have been documented in individuals with suspected cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Given that the symptoms of cannabis withdrawal are non-specific and have the potential to overlap with other disease processes, future work will be needed to evaluate the sensitivity of this instrument in populations with cyclic vomiting.

Time since the last cannabis use could not be controlled, given the unpredictability of cyclic vomiting episodes and the observational nature of the study; however, this factor was self-reported and provided to aid in the interpretation of biological sampling. Because time since the last use is based on participant self-report, it could be subject to recall bias.

One study participant had delta-8-THC detected in whole-blood. One previous case of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome in connection with delta-8-THC use has been reported in the literature.54 Knowledge of the therapeutic index and side effects of cannabis, which is at best limited in more typical cannabis preparations, is further challenged by the changing cannabis market now including new products and methods of consumption. Cannabinoids and metabolites outside the study testing scope could have influenced results or play a role in disease pathology. It is also possible that cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome episodes do not correlate with any serum biomarker.

Furthermore, this study was conducted within a single health system that could limit generalizability. Selection bias could lead to limited external validity because many patients declined study participation. Differences in the time to follow-up and patients lost to follow-up could have impacted the results. Given the small descriptive nature of this study, cannabinoid concentrations were not stratified based on other data factors but could be pursued in future work. Note, our original sample size for this study was calculated on the ratios of THC:CBD, but this study cohort had undetectable CBD levels. Therefore, further statistical analyses are not presented. The effect estimates generated in this work can be used for the more precise determination of the sample size in future studies.

CONCLUSION

Further studies are needed to better understand the effect of cannabinoid metabolism and concentrations on symptomatic cyclic vomiting. The frequency of daily use and high rates of cannabis use disorder, cannabis withdrawal, and self-reported mental health conditions in the study participants suggest that there may be factors beyond the cannabis product that influence the development of cyclic vomiting in people who use cannabis chronically.

Supplementary Material

Editor’s Capsule Summary.

What is already known on this topic

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is common, but the relationship between toxin blood levels and symptoms is unclear.

What question this study addressed

Is there an association between cannabinoid levels and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) symptoms?

What this study adds to our knowledge

This is a single center observational study of ED patients with acute CHS exacerbations and at least 2 weeks follow-up, cannabinoid levels were similar between acute cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome exacerbation and asymptomatic time periods.

How this is relevant to clinical practice

The biologic paths to cannabinoid hyperemesis remain unclear.

Funding and support:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH (R21DA055023). In addition, Dr. Wightman is partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (P20GM12550), the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH (UG3DA056880), and the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE) award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institute of Health or the FORE Foundation.

Contributor Information

Rachel S. Wightman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI; Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health at Brown University, Providence, RI.

Jane Metrik, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University, School of Public Health, Providence, RI; Providence VA Medical Center, Providence, RI.

Timmy R. Lin, Brown Emergency Medicine, Providence, RI.

Yu Li, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health at Brown University, Providence, RI.

Adina Badea, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Lifespan Academic Medical Center, Rhode Island Hospital, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI.

Robert Almeida, Forensic Toxicology Laboratory, Department of Health, Rhode Island, Providence, RI..

Alexandra B. Collins, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health at Brown University, Providence, RI.

Francesca L. Beaudoin, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health at Brown University, Providence, RI.

REFERENCES

- 1.F Dirmyer V Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A growing concern for New Mexico. ASM. 2018;2(1). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HS, Anderson JD, Saghafi O, et al. Cyclic vomiting presentations following marijuana liberalization in Colorado. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):694–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habboushe J, Rubin A, Liu H, et al. The prevalence of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome among regular marijuana smokers in an urban public hospital. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;122(6):660–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut. 2004;53(11):1566–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myran DT, Roberts R, Pugliese M, et al. Changes in emergency department visits for cannabis hyperemesis syndrome following recreational cannabis legalization and subsequent commercialization in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2231937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, et al. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008–2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269(1):5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smart R, Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, et al. Variation in cannabis potency and prices in a newly legal market: evidence from 30 million cannabis sales in Washington state. Addiction. 2017;112(12):2167–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman TP, Winstock AR. Examining the profile of high-potency cannabis and its association with severity of cannabis dependence. Psychol Med. 2015;45(15):3181–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Forti M, Sallis H, Allegri F, et al. Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40(6):1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrilli K, Ofori S, Hines L, et al. Association of cannabis potency with mental ill health and addiction: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(9):736–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galli J A, Andari Sawaya R, Friedenberg F K Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2011;4(4):241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment—a systematic review. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13(1):71–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace E, Andrews S, Garmany C, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011;104(9):659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuttler C, Spradlin A. Measuring cannabis consumption: Psychometric properties of the daily sessions, frequency, age of onset, and quantity of cannabis use inventory (DFAQ-CU). PLOS ONE. 2017;12(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, et al. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: the Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110(1–2):137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budney AJ, Novy PL, Hughes JR. Marijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 1999;94(9):1311–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-Functional GI disorders: Disorders of gut-brain interaction. J Gastroenterol. 2016;150(6):1257–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: A case series of 98 patients. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2012;87(2):114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatesan T, Sengupta J, Lodhi A, et al. An Internet survey of marijuana and hot shower use in adults with cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS). Exp Brain Res. 2014;232(8):2563–2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venkatesan T, Hillard CJ, Rein L, et al. Patterns of cannabis use in patients with cyclic vomiting syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(5):1082–1090.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budney AJ, Moore BA, Vandrey RG, et al. The time course and significance of cannabis withdrawal. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(3):393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, et al. Marijuana abstinence effects in marijuana smokers maintained in their home environment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(10):917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karschner EL, Swortwood-Gates MJ, Huestis MA. Identifying and quantifying cannabinoids in biological matrices in the medical and legal cannabis era. Clin Chem. 2020;66(7):888–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Li BUK, et al. Role of chronic cannabis use: Cyclic vomiting syndrome vs cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019;31(Suppl 2):e13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ElSohly MA, Mehmedic Z, Foster S, et al. Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995–2014): Analysis of current data in the United States. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(7):613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neubig RR, Spedding M, Kenakin T, et al. International Union of Pharmacology Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug Classification. XXXVIII. Update on terms and symbols in quantitative pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55(4):597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Megan E Patrick JES, Richard A, et al. Data from: Monitoring theFuture Panel Study Annual Report 2021. 2022.

- 28.Andrews CN, Rehak R, Woo M, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome in North America: evaluation of health burden and treatment prevalence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56(1112):1532–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connor JP, Stjepanovic D, Budney AJ, et al. Clinical management of cannabis withdrawal. Addiction. 2022;117(7):2075–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blumentrath CG, Dohrmann B, Ewald N. Cannabinoid hyperemesis and the cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults: recognition, diagnosis, acute and long-term treatment. Ger Med Sci. 2017;15:Doc06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burillo-Putze G, Richards JR, Rodríguez-Jiménez C, et al. Pharmacological management of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: an update of the clinical literature. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2022;23(6):693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards JR, Gordon BK, Danielson AR, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(6):725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee C, Greene SL, Wong A. The utility of droperidol in the treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa). 2019;57(9):773–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russo EB, Spooner C, May L, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome survey and genomic investigation. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022;7(3):336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grotenhermen F Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(4):327–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreuz DS, Axelrod J. Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol: Localization in body fat. Science. 1973;179(4071):391–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. J Anal Toxicol. 1992;16(5):276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karschner EL, Schwilke EW, Lowe RH, et al. Do Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol concentrations indicate recent use in chronic cannabis users? Addiction. 2009;104(12):2041–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giroud C, Ménétrey A, Augsburger M, et al. Δ9-THC, 11-OH-Δ9-THC and Δ9-THCCOOH plasma or serum to whole blood concentrations distribution ratios in blood samples taken from living and dead people. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;123(2):159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richards JR, Lapoint JM, Burillo-Putze G. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: potential mechanisms for the benefit of capsaicin and hot water hydrotherapy in treatment. Clin Toxicol (15563650). 2018;56(1):15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunasekaran N, Long LE, Dawson BL, et al. Reintoxication: the release of fat-stored Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) into blood is enhanced by food deprivation or ACTH exposure. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(5):1330–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel S, Roelke CT, Rademacher DJ, et al. Endocannabinoid signaling negatively modulates stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology. 2004;145(12):5431–5438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong S, Fan J, Kemmerer ES, et al. Reciprocal changes in vanilloid (TRPV1) and endocannabinoid (CB1) receptors contribute to visceral hyperalgesia in the water avoidance stressed rat. Gut. 2009;58(2):202–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Storr MA, Sharkey KA. The endocannabinoid system and gut-brain signalling. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7(6):575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudd JA, Nalivaiko E, Matsuki N, et al. The involvement of TRPV1 in emesis and anti-emesis. Temperature (Austin) 2015;2(2):258–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romero J, Berrendero F, Manzanares J, et al. Time-course of the cannabinoid receptor down-regulation in the adult rat brain caused by repeated exposure to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Synapse. 1998;30(3):298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lundberg DJ, Daniel AR, Thayer SA. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol-induced desensitization of cannabinoid-mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission between hippocampal neurons in culture. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(8):1170–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lichtman AH, Wiley JL, LaVecchia KL, et al. Effects of SR 141716A after acute or chronic cannabinoid administration in dogs. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;357(2):139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villares J Chronic use of marijuana decreases cannabinoid receptor binding and mRNA expression in the human brain. Neuroscience. 2007;145(1):323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergamaschi MM, Karschner EL, Goodwin RS, et al. Impact of prolonged cannabinoid excretion in chronic daily cannabis smokers’ blood on per se drugged driving laws. Clin Chem. 2013;59(3):519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wurz GT, DeGregorio MW. Indeterminacy of cannabis impairment and Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ(9)-THC) levels in blood and breath. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albert K, Sivilotti MLA, Gareri J, et al. Hair cannabinoid concentrations in emergency patients with cannabis hyperemesis syndrome. Cjem. 2019;21(4):477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cordova J, Biank V, Black E, et al. Urinary cannabis metabolite concentrations in cannabis hyperemesis syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;73(4):520–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenthal J, Howell M, Earl V, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome secondary to delta-8 THC use. Am j med. 2021;134(12):e582–e583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.